Shifting

socioemotional

wealth prioritization

during a crisis

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Global Management AUTHORS: Stella Alice Gisela Heuer & Lajos Szabó TUTOR: Tommaso Minola

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

A content analysis of statements to shareholders of

family businesses

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Shifting socioemotional wealth prioritization during a crisis: A content analysis of statements to shareholders of family businesses

Authors: Stella Alice Gisela Heuer and Lajos Szabó Tutor: Tommaso Minola

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Family business, socioemotional wealth, FIBER, COVID-19, content analysis, Sweden, Germany

Abstract

Family businesses are generally considered to be the most prevalent form of business around the world. They have also been shown to differ from their family counterparts due the non-economic factors that influence their decision-making. One of the most widely used conceptualization of these factors concerns the controlling family’s socioemotional endowment or in other words, the family’s socioemotional wealth. Newer approaches have proposed that socioemotional wealth can not only be broken down into several component dimensions, but that these dimensions may shift in prioritization in response to different contingencies. The sudden spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global crisis that has followed in its wake is one such contingency, impacting economies and family firms virtually everywhere in the world. Studying the crisis’ effects on family firms has thus already been outlined as a major focus of research going forward. This paper aims to develop the concept of socioemotional wealth as a dynamic construct and study the crisis’ effects on family firms. We conduct a content analysis of 20 Swedish and 20 German publicly listed family firms’ statements to shareholders published over a three-year period coinciding with the emergence of the crisis. Thus, this research presents an empirical look at how family firms in the contexts of two differing governmental responses to the crisis prioritized the different dimensions of their socioemotional wealth. The results show the families’ emotional attachment coming to the forefront in both cases, with no significant difference between the two countries’ family firms. Furthermore, we observe the families’ socioemotional ties to their employees retain their pre-crisis prevalence as the most prioritized dimension. This is accompanied by a deepening of the quality of the communication tied to this dimension of socioemotional wealth with it coming to reflect the emerging solidarity and cultural changes resulting from the crisis. The results suggest that family firms may respond to a crisis on the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic through their decision-making being increasingly influenced by their emotional attachment to the firm, while also retaining a focus on preserving strong social ties to their employees to persevere through the difficult period.

ii

Acknowledgements

We would like to give our gratitude to our supervisor, Tommaso Minola, for his unyielding support and valuable feedback during the writing of this thesis. His comments helped guide our research tremendously. We would also like to give a warm thank you to our peers in our thesis group for the insightful discussions and keen observations. We further thank Jordan-Dawn De Laender, Antonia Focke, Abdimajid Khayre and Jan Niklas Schmänk for their contributions in improving our work with their detailed comments and assessments as part of our monthly seminars.

iii

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations... v

List of Figures... vi

List of Tables... vi

List of Appendices... vi

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research Problem ... 21.3 Research Purpose and Research Questions ... 4

2

Theoretical Background ... 5

2.1 Literature Review Procedure... 5

2.2 Family Businesses ... 6

2.3 Socioemotional Wealth ... 8

2.4 FIBER ... 9

2.5 Crises in Family Businesses ... 14

2.5.1 Crisis Management in Family Businesses... 14

2.5.2 COVID-19 ... 15

2.5.3 Government Responses to COVID-19: Sweden and Germany ... 16

2.6 Propositions and Model Construction ... 19

3

Methodology ... 27

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 27

3.2 Research Approach ... 29

3.3 Research Strategy ... 30

3.4 Sample Selection and Data Collection ... 34

3.5 Data Analysis Procedure... 37

3.6 Research Quality ... 38

3.7 Research Ethics ... 39

4

Findings and Data Analysis ... 41

4.1 Description of Empirical Data ... 41

4.2 Descriptive Statistics ... 45

4.3 Statistical Analysis ... 50

4.4 Summary and Comparison with Prior Research ... 53

4.4.1 Summary of Findings ... 53

4.4.2 Ability Dimensions “F” and “R” ... 54

4.4.3 Willingness Dimensions “I”, “B” and “E” ... 57

4.4.4 Answering the Research Questions ... 64

5

Discussion ... 66

5.1 Discussion of Findings ... 66

5.2 Contribution and Implications ... 67

5.3 Limitations ... 70

5.3.1 Limitations of Theoretical Background ... 70

5.3.2 Limitations of Research Design ... 71

5.3.3 Limitations of Data Set ... 72

5.3.4 Limitations of Data Analysis ... 73

iv

6

Conclusion ... 76

7

Reference List... 78

8

Appendices ... 85

v

List of Abbreviations

B – The socioemotional wealth dimension of binding social ties COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease 2019

E – The socioemotional wealth dimension of emotional attachment EC – European Commission

F – The socioemotional wealth dimension of family control and influence

I – The socioemotional wealth dimension of identification with the firm on the family member’s

side

OxCGRT – Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker

R – The socioemotional wealth dimension of renewal of family bonds to the firm achieved by

way of dynastic succession

SEW – Socioemotional wealth WHO – World Health Organisation

vi

List of Figures

Figure 1: FIBER and its conditional inferences ... 11

Figure 2: SEW crisis model ... 20

Figure 3: Research onion ... 30

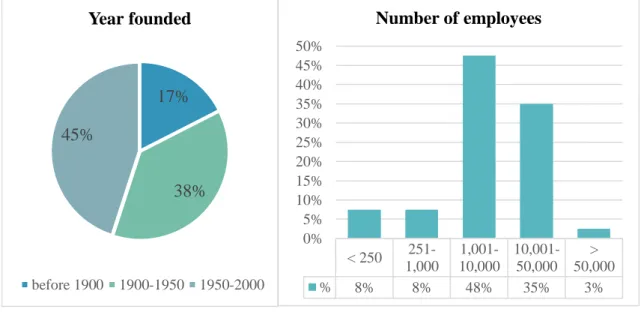

Figure 4: Descriptive statistics – year founded and number of employees ... 41

Figure 5: Descriptive statistics – revenues in million EUR ... 42

Figure 6: Descriptive statistics – sectors and family voting rights ... 42

Figure 7: Descriptive statistics – family member is on Executive Board ... 43

Figure 8: Descriptive statistics – family member is on Board of Directors ... 44

Figure 9: Descriptive statistics – family member is author of statement ... 44

Figure 10: Descriptive statistics – family name is also company name ... 45

Figure 11: FIBER prioritization in both countries (2018-2020) ... 47

Figure 12: FIBER prioritization Swedish sample (2018-2020) ... 47

Figure 13: FIBER prioritization German sample (2018-2020) ... 48

Figure 14: Number of FIBER and COVID-19 crisis related paragraphs ... 62

List of Tables

Table 1: The FIBER dimensions of SEW ... 10Table 2: Summary of propositions ... 26

Table 3: The ten steps of quantitative content analysis ... 32

Table 4: Breakdown of coded paragraphs ... 46

Table 5: Kruskal-Wallis test results for combined sample ... 51

Table 6: Kruskal-Wallis test results for Swedish sample ... 51

Table 7: Kruskal-Wallis test results for German sample ... 51

Table 8: Employee recognition before versus during COVID-19 ... 61

List of Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature overview procedure ... 85Appendix 2: Coding scheme ... 85

Appendix 3: Sample overview Swedish publicly listed family businesses ... 86

Appendix 4: Sample overview German publicly listed family businesses... 87

Appendix 5: Number of firms addressing specific FIBER dimensions ... 89

Appendix 6: Mann-Whitney U test results for the combined sample ... 89

Appendix 7: Mann-Whitney U test results for Germany... 90

Appendix 8: Mann-Whitney U test results for Sweden ... 91

Appendix 9: Mann-Whitney U test results between Germany and Sweden... 92

Appendix 10: Sample excerpts from statement to shareholders – “F” dimension ... 93

Appendix 11: Sample excerpts from statement to shareholders – “I” dimension... 94

Appendix 12: Sample excerpts from statement to shareholders – “B” dimension .... 95

Appendix 13: Sample excerpts from statement to shareholders – “E” dimension .... 96

1

1 Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

In this chapter the background of the research is introduced discussing family businesses, their relevance and how they may be influenced by outside stimuli such as crises. This is followed by the presentation of the identified research problem. The chapter is then concluded by the formulation of the research questions.

1.1 Background

Family firms are considered to be the most widespread form of business in the world (Gersick et al., 1997; La Porta et al., 1999). This fact by itself may suggest that no amount of focus could be considered too much when it comes to seeking to understand how these businesses differ from their non-family counterparts, what drives them and how they make decisions in the myriad of contingencies they may face. In turn, family firms have been the subject of a steadily growing stream of research. The fruits of this labour have shown that family businesses are not only the most common form of business around the globe but are also each unique in their own way. Indeed, if there is one aspect that family business research has seemingly solidified regarding their subject matter it is that no two family firms are ever the same (Daspit et al., 2018; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Yet, there seems to be one crucial aspect of family firms that still unifies them and sets them apart from non-family firms. That is not to say that the aforementioned field of family business research has agreed upon a unified definition of what a family firm is, quite the opposite in fact. However, what research does seem to have agreed on regarding family business is that they distinguish themselves from all other forms of organizations through the key importance non-economic factors play in their management (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Thus, the question of what exactly these non-economic factors are, how they are shaped and how family business principals make decisions according to them has led to several different conceptualizations of what drives family firm decision-making (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). One such conceptualization that has received much focus is that of socioemotional wealth (SEW) (Gomez-Mejía et al., 2007). The concept proposes that in order to pursue and protect SEW, that is non-financial aspects of the business such as family influence and ensuring intra-family succession, family firms have been shown to be willing to incur significant risks to their

2

financial performance. In contrast to previously used ones in the field of family business research the concept of SEW has been positioned as an approach which itself is specific to and originates from the unique way family businesses make decisions. It has been used and expanded upon extensively since its conception (Berrone et al., 2012). SEW has seen application in studying how external stimuli such as a crisis affects family businesses with recent focus being placed on the global financial crisis (Faghfouri et al., 2015; Rivo-López et al., 2020).

The topic, however, is still ripe with new opportunities for exploration. The relevancy of further such research could not be more apparent with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis it has left in its wake (De Massis & Rondi, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020; Rivo-López et al., 2020). With it officially being classified as a pandemic in the spring of 2020, COVID-19 has impacted businesses on a global scale (WHO, 2020e). In connection to previous crises family firms have already been shown to react in unique ways when compared to non-family ones, for instance through being a greater source of job stability (Rivo-López et al., 2020). Thus, it is imperative that more effort is directed towards understanding both the unique ways in which family firms face crises and the family firm specific goals behind their decisions. In turn, a global crisis of such magnitude not only further accentuates the necessity of such research, but also presents an unparalleled opportunity to further our understanding of the non-economic goals that drive family firms and how they are influenced by the outside contingency of a crisis (Swab et al., 2020). Due to the pandemic’s global nature, we are also able to observe how these goals are affected in family firms operating in diverse national contexts that entail different governmental methods to halting the spread of the virus. This study seeks to contribute to filling the gap in family business research connected to these topics.

1.2 Research Problem

As outlined in recent discussions, the COVID-19 pandemic has already had a profound effect on family businesses by posing new challenges (De Massis & Rondi, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020). De Massis and Rondi (2020) outline a SEW-based approach as a possibility for future research, specifically calling attention to the potential in using SEW-based approaches that focus on how the pandemic has affected the interplay between different dimensions that can be considered to make up SEW. One such approach builds on the

3

concept of SEW by breaking it down into five dimensions which together make up the socioemotional endowment of the controlling family (Berrone et al., 2012). These five “FIBER“ dimensions of SEW (Berrone et al., 2012) have already seen use in studying how family firms behave during a crisis. One such study found that family firms in Spain proved to be a source of higher job stability than their non-family counterparts during the global financial crisis (Rivo-López et al., 2020). Furthermore, this study also concludes

by calling attention to the future study of family firms’ potentially similar role during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Recent developments regarding the topic of SEW have also suggested conceptualizing and further investigating FIBER as a dynamic construct where its dimensions interact and shift in priority in response to different contingencies (Nason et al., 2019; Swab et al., 2020). Finally, even though in the original conceptualization of the FIBER dimensions suggested the use of content analysis as a suitable method for the concept’s further research (Berrone et al., 2012) the method has been severely underutilized. Given the method’s natural fit for longitudinal studies which could investigate how FIBER dimensions shift over time, it is even more surprising that only a scarce few papers have adapted the approach thus far (Cleary et al., 2019).

Considering the above, it is clear that at the intersection of the topics of family businesses, their SEW endowment conceptualized as a dynamic construct and crisis lies a research gap that is ripe for new studies. The relevance of new research aiming to fill this gap is further made imperative when considering the magnitude of the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Following these points, this paper investigates how the interplay of the different FIBER dimensions making up SEW may have been influenced in the family firms of two countries with differing governmental restrictions related to the pandemic. This is achieved through the content analysis of statements to shareholders published during a three-year period coinciding with the emergence of the crisis, allowing for a longitudinal approach.

We aim to look at family firms dealing with the situation under the fundamentally different decentralized and voluntary guideline-based approach that the Swedish government has taken in its answer to the COVID-19 pandemic, in contrast to the rest of Europe (Granberg et al., 2021; Kuhlmann et al., 2021). We also reflect on how this

4

difference in approach could have potentially influenced the SEW prioritization of Swedish family businesses during the pandemic when compared to those of a European country with more severe restrictions. For this purpose, we have chosen Germany. We specifically aim to uncover how the crisis may have impacted the prioritization of FIBER dimensions by family firm principals and how the difference in governmental approaches in response to the crisis may have influenced this prioritization (Rivo-López et al., 2020; Swab et al., 2020). Furthermore, this is investigated in the context of two countries with divergent governmental restrictions put in place in response to the crisis. In doing so this work answers calls for expanding the SEW literature in relation to the pandemic’s effects (De Massis & Rondi, 2020; Rivo-López et al., 2020) and for the study of its FIBER dimensions as a dynamic construct (Swab et al., 2020). Furthermore, it does so using a method that is both underutilized in family business research and has been explicitly recommended for further developing the FIBER construct (Berrone et al., 2012; Cleary et al., 2019).

1.3 Research Purpose and Research Questions

The aim of this thesis is to understand the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on family business decision-making during crises by investigating its impact on SEW. Our aim is to study how the pandemic affected family business decision-making when viewed through the lens of the five FIBER dimensions. Following recent developments related to the conceptualization of FIBER, we seek to study how the prioritization of these dimensions may have shifted in response to the crisis (Cleary et al., 2019; Swab et al., 2020). Furthermore, we seek to discover how the diverging contexts of differing governmental regulations may have influenced how the crisis impacts the prioritization of these dimensions. This is achieved by comparing firms in two countries with differing approaches to the crisis. For this purpose, we have chosen Sweden where the government took on a voluntary recommendation-based approach and Germany where compulsory restrictions were put into place.

We thus construct the following two research questions:

I. Research Question: How does a crisis affect the prioritization of SEW dimensions in family firm decision-making?

II. Research Question: How is this prioritization different between family firms of

5

2 Theoretical Background

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following chapter provides a discussion of the existing literature in the field of family business research with a focus on decision-making in family firms as conceptualized through SEW. First, we provide our literature review procedure which is followed by a brief overview of family businesses. After that, our selected definition of a family businesses is introduced as well as the concept of socioemotional wealth and its FIBER dimensions. Next, the phenomenon of a crisis in family businesses is discussed, leading into a description regarding the one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. We conclude by presenting a SEW model with its FIBER dimensions extended to account for the effects of a crisis.

2.1 Literature Review Procedure

With the aim of finding adequate and suitable academic literature for the theoretical background section underlying our research, different literature databases for the search were used. We wanted to ensure that we did not focus on only one literature database and thus miss relevant articles. Hence, we primarily concentrated our search on Web of

Science and Scopus1, as these search portals are known for their trustworthiness as well

as their peer-reviewed high-quality articles. Furthermore, we also took care in ensuring that most of our chosen articles’ journals were on the ABS list of 2018, following the guideline that their rating should be at least 2 or higher to be included in our work. We only made an exception if the article was indispensable for the study.

For our search runs in the above-mentioned databases we divided our literature search into different batches: family businesses and crises, socioemotional wealth, FIBER, COVID-19 and related governmental responses. Initially, our search words were "family business" in conjunction with "crisis", "COVID-19" and "decision making". We later followed this up with searches using the keyword combinations of "socioemotional wealth" and "crisis", specifically keeping an eye out for articles by Gomez-Mejia, given the authors key role in developing the concept. Afterwards our search focused on the topic

1 In Web of Science we searched within all fields. In Scopus we searched within the combined fields of

6

of "FIBER". Additionally, we searched for "government", "COVID-19", "pandemic", "Sweden", "Germany" and "prospect theory". An overview of our literature review procedure can be found in Appendix 1.

Due to the topic of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis it fostered still being fresh in the literature, we paid special attention to continuously search for new literature during the writing process which encompassed the period between January and May of 2021. This was done because some articles relevant to us may not have been published until 2021 due to the then still ongoing nature of the pandemic. We proceeded in the same way with the other topics.

In addition, the sources used in the articles found through the above process were also reviewed if they were found to connect to our chosen topics. This allowed us to account for relevant articles that were not displayed in the results of the searches conducted using the above-mentioned portals. Thus, we added an element of snowballing to our process.

2.2 Family Businesses

Family business research has seen a significant and continuous growth for the last two decades (Brigham & Payne, 2019; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Swab et al., 2020). The diverse research interest that family firms have garnered is not surprising if one considers the global prevalence of the myriad of businesses that fall under the family firm umbrella term (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Research in the field has consistently pointed out family firms to be the most common form of businesses around the globe (Gersick et al., 1997; La Porta et al., 1999).

In general, a family firm can be defined as “a firm where members of the founding family

continue to hold positions in top management, are on the board, or are blockholdersof the company” (Chen et al., 2008, pp. 499-500). However, the increased focus placed on

family firms is also coupled with research that has dealt with a plethora of differing topics in relation to family businesses, thus resulting in no clear consensus regarding how to best define the term “family business” (Chua et al., 1999; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Gomez-Mejia et al. (2011) arrive at the conclusion that the literature mostly agrees on family firms differentiating themselves from other organizational forms with the increasingly important role non-economic factors play in their management. When it comes to empirical research, they also point out how more nuanced operational

7

definitions should be left to the discretion of the given researcher. According to them this is made necessary due to the heterogenous nature of family firms, an attribute that has been discussed in various contexts, whether it be in terms of varying ownership structures, differing contingencies affecting decision-making processes or governance structures (Daspit et al., 2018; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016; Swab et al., 2020).

One area of major focus for family business research in recent years has been that of SEW, a construct seeking to understand family firm decision-making by looking at the non-economic family specific drivers influencing them (Brigham & Payne, 2019; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Schulze & Kellermanns, 2015; Swab et al., 2020). The popularity of the concept has, in turn, allowed for several operational conceptualizations of a definition for family firms. Due to our theoretical approach being based on SEW and its FIBER dimensions, we will be using a definition of family firms that is also based on the SEW approach, in line with the recommendations of Gomez-Mejia et al. (2011). Gomez-Mejia et al. (2011) define family firms through the use of the SEW concept, pointing out how they can be characterized as being “motivated by and committed to the

preservation of nonfinancial or affective utilities, or what we call socioemotional wealth”

(Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011, p. 692) and thus differentiating them from non-family firms. We adapt this broader definition of the family firm. However, they further add that specific operationalizations of the definition should depend on the given study’s context. Due to this, alongside the above broader SEW-based definition of family firms, we also define family firms from an operational perspective. For this goal we adopt the definition of family firms by the European Commission (EC, 2009) as it has been previously used to define family firms in the national context of Sweden (Andersson et al., 2018) and it matches the criteria used in German family firm related studies (Benz et al., 2020). Thus, it fits our research since we focus on publicly listed family firms in Sweden and Germany. For publicly listed companies, the approach defines family firms as ones where either an individual or a family holds at least a quarter of the decision-making rights, in conjunction with one family member engaged in the firm’s governance at minimum (EC, 2009). The basis of our research, however, is mainly rooted in SEW and its approach to conceptualizing and defining family firms. We discuss the concept in detail in the following section.

8

2.3 Socioemotional Wealth

The concept of socioemotional wealth, first introduced by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007), looks at family firm decision-making from a behavioural agency theory perspective (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2014; Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998). The construct proposes that contrary to the generally accepted assumption that had dominated before the publishing of the aforementioned article, family firms are not risk averse but in fact are willing to take on significant risk in order to preserve their socioemotional endowment. SEW itself can be defined as the affective endowments or affective utilities of family firms (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007).

The SEW approach proposes the notion that family firms’ primary frame of reference for decision-making concerns these non-financial aspects of the firm and hence problems are framed and assessed in terms of potential gains and losses to SEW (Berrone et al., 2012). The pursuit of preserving SEW in turn means that family firms make economically risky decisions, due to their frame of rationality being one that primarily aims to preserve or increase their socioemotional endowment (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). From the perspective of non-family firms where financial performance is used as the dominant guide of decision-making, this would consequently seem like irrational decision-making.

The concept of SEW, non-economic goals driving family firm decision-making, has since been the focus of intense research (Brigham & Payne, 2019; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Schulze & Kellermanns, 2015). The interplay of financial and non-financial goals in family firms has been expanded upon considerably (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2018; Gomez– Mejia et al., 2014; Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). This line of research has shown a more nuanced picture regarding the relationship of SEW-related and financial goals, with them having the potential to either reinforce or hinder each other depending on the given situation of the family (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2018; Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). SEW has also received its fair share of critique aiming to deepen and develop the concept as the amount of research using the approach proliferated (Kellermanns et al., 2012; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2014; Newbert & Craig, 2017). There are several main points of critique concerning SEW. Some discuss how most research has relied on secondary data and has been conducted using family ownership or other proxies as a stand-in for the

9

existence of SEW in a given firm (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Others question if the concept is unique to family firms to begin with (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Furthermore, the topic of whether SEW is inherently altruistic or self-serving (Newbert & Craig, 2017) or if SEW itself can be a burden to the firm (Kellermanns et al., 2012) has been a locus of discussion in studies critiquing SEW. In our research we aim to answer calls for a more direct approach to measuring SEW, albeit still through secondary data, by adapting a model that looks at the prioritization of SEW dimensions by the family (Swab et al., 2020). By using secondary data, we are able to take on a longitudinal approach that was able to cover a multitude of different family firms and their own unique experiences before and during the crisis.

The SEW literature has furthermore expanded into the research topics of family business decline (Llanos-Contreras & Jabri, 2019) and crisis management within family firms (Casillas et al., 2019; Marett et al., 2018; Rivo-López et al., 2020). However, a SEW-based look at the crisis management of family firms is still ripe for new research opportunities, given both the novelty of the global crisis situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (De Massis & Rondi, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020; Rivo-López et al., 2020) and new approaches to operationalizing SEW through the FIBER model as dynamic concept (Swab et al., 2020).

2.4 FIBER

The FIBER model breaks down SEW into five dimensions in order to allow for a more detailed view of the different components that shape a family firm’s socioemotional endowment (Berrone et al., 2012). As seen in Table 1, FIBER corresponds to the five dimensions of: family control and influence (F), identification with the firm on the family

member’s side (I), binding social ties (B), emotional attachment (E) and renewal of family bonds to the firm achieved by way of dynastic succession (R) (Berrone et al., 2012). Since

its inception the concept has been expanded upon in various ways. The family firm aspects embodied in each dimension have also received individual attention (Hauck et al., 2016; Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016; Rivo-López et al., 2020; Swab et al., 2020). In our overview of the FIBER construct, we consider the original conceptualization, recent developments and proposed modifications to the construct as well as relevant topics related to each dimension in order to assist the formulation of our own SEW model based on the FIBER dimensions as discussed in section 2.6.

10

Before the individual dimensions are illustrated in detail it needs to be noted that one of the most recent developments of the FIBER model further categorizes the dimensions into the categories of willingness and ability (Swab et al., 2020). In this conceptualization of the model, the existence of SEW within a firm is dependent on whether it fulfils the conditions of both having the willingness and the ability to support it. Ability covers the two dimensions of family control and influence (F) as well as renewal of family bonds to the firm achieved by way of dynastic succession (R). The other three dimensions of identification with the family firm, binding social ties and emotional attachment fall under the willingness category. According to this approach a family firm possess SEW if it simultaneously has both dimensions of the ability category and at least one dimension that falls under willingness. Having both of the ability dimensions gives firms the power to pursue and preserve SEW, while having at least one of the willingness dimensions gives them the drive to do so (Figure 1). Swab et al. (2020) further propose that these dimensions can shift over time, as the family firm prioritizes different dimensions in response to different contingencies. Next, we shift our focus to discussing the individual FIBER dimensions.

FIBER Dimension Description

F Family Control and Influence Family members’ ability to exert control over and influence strategic decisions for the family firm.

I Identification of Family

Members with the Firm

Family members’ ties to the firm concerning how they view their own family’s identity and the family firm’s identity to overlap, for example through the firm sharing the family’s name.

B Binding Social Ties Family members’ bonds both with other members of the family

and non-family stakeholders in connection to the firm.

E Emotional Attachment of

Family Members

The role family members’ emotions play in family firm decision-making.

R Renewal of Family Bonds

Through Dynastic Succession

The drive and ability of the family to pass down the firm through intra-family succession.

11

Figure 1: FIBER and its conditional inferences (own elaboration based on Swab et al., 2020)

According to Berrone et al. (2012) the dimension of family control and influence (F) ties into the distinguishing feature separating family firms from non-family ones, namely the family members’ ability to influence and control strategic decisions. This aspect of family firms is also used in cases to define family firms themselves (Chua et al., 1999). Regardless, as Berrone et al. (2012) detail, the continued preservation of such control is an important factor for keeping SEW intact. Additionally, the dimension relates to the topic of the potential development of nepotism in family firms, which has recently been shown to be able to both aid or undermine family firms (Firfiray et al., 2018). Critiques of the FIBER model have also pointed out that this dimension may overlap with the dimension of renewal of family bonds (R) (Hauck et al., 2016). Furthermore, it is noted to being measured in how control is exerted in practice over the firm by the controlling family. Thus, this dimension can be said to have more ties to the economic side of the firm, as opposed to the affective dimensions driving the family decisions (Hauck et al., 2016). This dimension has also been theorized to negatively impact financial performance (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). Building upon prior research concerning this dimension, Swab et al. (2020) frame family control and influence as a necessary but not sufficient condition within a firm for SEW to exist. They outline this dimension as additionally needing the dimension of “R” to give a firm the ability to work towards preserving SEW and at least one of the other three dimensions for SEW to exist within the firm (Figure 1).

12

The “I” dimension refers to family members’ identification with their firm and ties into the identity of the firm being an extension of the family’s identity (Berrone et al., 2012). Thus, this dimension is associated with explaining more responsible decision-making in family firms, to avoid tarnishing both the name of the firm and the family. In line with this reasoning, the dimension has also been suggested to be positively associated with firm performance (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). In their modified FIBER model Swab et al. (2020) assign this dimension the role of providing the willingness for the controlling family to work towards SEW-related goals (Figure 1).

Binding social ties (B) in Berrone et al.’s (2012) original approach refers to the social

relationships of the family firm. It is also categorized as a factor contributing to willingness in pursuing SEW by Swab et al. (2020) (Figure 1). This dimension has been associated with how family firms make decisions regarding both family members and other non-family stakeholders such as for instance employees, suppliers or local communities. Additionally, family firms have been shown to put care into preserving relationships with both (Casillas et al., 2019; Cennamo et al., 2012; Rivo-López et al., 2020). For relations between family members, the related topics involve ones such as favouritism possibly leading to nepotism and its potential benefits or negative effects (Firfiray et al., 2018). The topic of non-family employees has also been expanded in recent research, with family firms being shown to provide a higher rate of job stability during crises than their non-family counterparts (Rivo-López et al., 2020). However, the dimension has also been associated with a possible negative effect on performance, as family members may shift towards favouritism excluding non-family employees from top management (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). Furthermore, the dimension of binding social ties has been pointed out to be in need of further development in relation to its operationalization (Hauck et al., 2016).

Emotions have received their fair share of focus in family business research (Kellermanns et al., 2014; Morgan & Gomez-Mejia, 2014). Given how SEW concerns the non-economic family centric affective endowment of family firms, it comes as little surprise that FIBER has a corresponding dimension for emotions in emotional attachment (E) (Berrone et al., 2012). Originally, the dimension was referred to as encompassing the role taken on by emotions in the context, which are known to exert influence over virtually all parts and processes of the family firm, from succession planning to stakeholder relations

13

(Morgan & Gomez-Mejia, 2014). This dimension has also been linked to the reputational aspect of the family firm (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). Similarly, to the FIBER dimension of identification, the boundary between the family members and the firm are blurred in terms of reputation. Thus, the family members’ drive to preserve a good image extends to both the family and the firm. Furthermore, the drive to maintain reputation has been positively linked to performance and corporate social responsibility (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). Swab et al. (2020) categorize emotional attachment as another source of willingness for family firms to support SEW goals (Figure 1).

The final dimension, renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession (R), is connected to the practice of intra-family succession, one of the key traits of family firms (Berrone et al., 2012). The goal of preserving the firm and the controlling family’s influence over it through subsequent generations has been shown to be a defining trait of family firm decision-making (De Massis et al., 2008; Sund et al., 2015). Consequently, exit strategies in times of performance decline have been shown to be a last resort measure for family firms. In a bid to preserve SEW derived from continued succession in the family, family firms avoid exit strategies where non-family firms would not (Chirico et al., 2020). Furthermore, the question of the generation in control has also been the subject of interest for research, with the “R” dimension positively relating to firm performance predominantly in the case of the founder generation (Martin & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). A focus on the preservation and increase of SEW in general has also been shown to diminish as the baton of family control is passed to subsequent generations of the family (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Swab et al. (2020) consider this dimension to be the other necessary component of SEW that, together with family control, comprise the ability of family firms to allow for the preservation and pursuit of SEW (Figure 1).

The FIBER construct has seen recent application in research seeking to understand the differences in family and non-family decision-making during the crisis situation caused by the global financial crisis (Rivo-López et al., 2020). As our research looks at family firms in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis it has triggered, we proceed by discussing these topics in the next section.

14

2.5 Crises in Family Businesses

2.5.1 Crisis Management in Family Businesses

A crisis can be identified as a sudden event that changes a system and its individual components (Kraus et al., 2020). The literature further attributes several common features to organisational crises (Runyan, 2006). While the probability of occurrence may be low, in a worst-case scenario, the crisis may potentially threaten the very existence of a company (Dutton & Jackson, 1987; Witte, 1981). In addition, numerous stakeholders are affected and an acute crisis forces decisions to be made quickly (Hills, 1998; Pearson & Clair, 1998).

According to Kraus et al. (2020) a basic distinction regarding the type of crisis is whether it is caused internally by a company (Bundy et al., 2017) or by external factors such as natural disasters (Runyan, 2006). Furthermore, it should be mentioned that crises can also have positive effects for stakeholders. The external stimulus of a crisis can lead to innovations or even to an entry into new markets (Faulkner, 2001). Apart from the COVID-19 crisis detailed below, another prominent example for an external crisis is the Great Recession, an event which was brought about due to the enormous downward trend in the economy from 2007 to 2009 as a result of the global financial crisis (Rivo-López et al., 2020).

The topic of how family firms fare during crises in comparison to their non-family peers has also garnered attention from researchers in connection to both the global financial crisis, and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Family firms have been consistently shown to tackle crisis situations and make decisions in ways that differ from non-family companies (Casillas et al., 2019; Chirico et al., 2020; Faghfouri et al., 2015; Kraus et al., 2020; Minichilli et al., 2016). When compared to non-family firms, family firms have also been proven to be a source of higher job stability and support for employees (Kraus et al., 2020; Rivo-López et al., 2020) and are able to apply retrenchment more flexibly and dynamically during a crisis (Casillas et al., 2019). However, family businesses have also been noted to employ formalized crisis procedures less frequently when family ownership is higher (Faghfouri et al., 2015). The question of family firms performing better or worse than non-family ones during a crisis seems to be unresolved with research presenting results in support of both possibilities (Arrondo-García et al., 2016; Minichilli et al., 2016). Chirico et al. (2020) argue that family firms are unlikely to pursue an exit

15

strategy due to deteriorating performance relative to their non-family counterparts. The authors see the reasons for this in the fact that family businesses draw more strongly on non-financial benefits while also aiming to ensure succession.

Furthermore, family firms show a tendency to plan both in terms of short-term challenges, by securing liquidity as well as to keep the long-term security of the firm in focus (Kraus et al., 2020). These traits reflect the values and goals driving family firm decision-makers that go beyond only financial aspects (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Thus, the SEW approach has also been applied in studies investigating the relationship between family firms and crises (Casillas et al., 2019; Rivo-López et al., 2020). Rivo-López et al. (2020) as well as De Massis and Rondi (2020) specifically call for future research to focus on the recent crisis situation brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on family firms. As outlined above we intend to answer this call using a SEW-based approach.

2.5.2 COVID-19

In the following, we provide a brief overview of the crisis situation that acts as the backdrop for our research. We continue with a short description of the events unleashed by the pandemic.

The origins of COVID-19 can be traced back to Wuhan, China. By December 2019, there was an increase in unexplained pneumonia cases in the city that could not be ascribed to a pre-existing disease (WHO, 2020a). As a local seafood market appeared to be linked to the sudden outbreak it was shut down by Chinese officials shortly after (Huang et al., 2020). The Chinese government announced that the virus had been identified as a new type of coronavirus which can easily spread from one person to another (WHO, 2020b). The first deaths associated with the virus were confirmed and the entire Hubei province was put under quarantine (Moosa, 2020; WHO, 2020a). In Europe, the first COVID-19 patient was identified at the end of January, coinciding with a similar situation in many other countries around the world (WHO, 2020c). Consequently, on January 30, 2020 the WHO (World Health Organisation) declared “the outbreak to be a public health

emergency of international concern” (WHO, 2020d, p. 1). By March 11, 2020

COVID-19 was classified as a pandemic (WHO, 2020e) by exceeding the classification of an epidemic as it impacted a large number of individuals beyond international borders (Porta et al., 2014). After Italy and Spain were initially hit hard by the virus in Europe and both

16

countries imposed a total lockdown, rising infection figures in other countries also led to the adoption of stricter measures to contain the virus (Giritli Nygren & Olofsson, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020). This led to a severe restriction of public and private life. After a temporary decline during the summer, infection levels rose again in a second wave in many European countries during the winter, resulting in related stricter measures. By December 2020, the first vaccines were approved (Warren & Lofstedt, 2021).

The restrictive measures taken by the national authorities in response to COVID-19 led to enormous disruptions in the economy (Anderson et al., 2020). According to Kraus et al. (2020) it is already clear that the COVID-19 crisis is not only a severe economic crisis but also the catalyst for the largest global recession since the Great Depression. Thus, it is associated with a global increase in unemployment rates accompanied by the potential destabilization and collapse of entire industries. While some firms have been able to forge unique opportunities out of the crisis, others had to forfeit high revenues due to government-induced closures and disrupted supply chains (Kraus et al., 2020).

2.5.3 Government Responses to COVID-19: Sweden and Germany

As Kraus et al. (2020) outline governments displayed urgency to contain the virus through different measures. Studies on the necessity of various non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as domestic case isolation, social distancing measures or closure of nonessential businesses or institutions, indicate that a combination of diverse non-pharmaceutical interventions is essential to prevent the health system from collapsing in the light of COVID-19 (Ferguson et al., 2020; Hale et al., 2020; Moosa, 2020; Yan et al., 2020). These measures aim to reduce social contacts as much as possible with the goal of flattening the infection curve to ease the burden on the health care system and to buy time to develop a vaccine (Moosa, 2020). Measures included cancelling major events, imposing travel restrictions and bans, closing schools and universities, closing restaurants and hotels as well as shutting down companies that operate for instance in the leisure industry (Hale et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020).

Most of Europe has reacted in a more or less unified way regarding the implementation of compulsory restrictions (Kraus et al., 2020; Moosa, 2020; Yan et al., 2020). However, Sweden can be considered as an exception to this case since it decided to adopt recommendations instead of severe restrictions (Giritli Nygren & Olofsson, 2020; Kuhlmann et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2020).

17

The international press has often criticized Sweden’s COVID-19 approach for being irresponsible, controversial and too soft (Giritli Nygren & Olofsson, 2020; Granberg et al., 2021). However, others like Granberg et al. (2021) consider this to be a misrepresentation. For instance, Sweden periodically closed educational institutions, advised the elderly for self-isolation, limited public meetings to 50 people, advised to refrain from traveling and recommended professionals to work from home whenever possible (Giritli Nygren & Olofsson, 2020; Granberg et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the major difference remaining compared to other European countries are that most aspects of the Swedish approach are based on recommendations instead of compulsory rules (Kuhlmann et al., 2021). Yan et al. (2020) classify Sweden’s COVID-19 approach as a nudging strategy which is characterized by the aim of modifying behaviours in such ways that the implementation of prohibitions is not necessary.

Within the scope of our thesis, we are interested in how Sweden’s unique and rather liberal laissez-faire response to the COVID-19 crisis may have impacted Swedish family businesses prioritization of the SEW dimensions compared to another European country pursuing a rather authoritarian approach by enforcing legally binding measures. For this purpose, we have chosen Germany. The German COVID-19 response was mainly determined by concrete restrictions suspending many civil liberties and basic rights. In order to ensure that citizens comply with the measures, disobeying them would result in sanctions and penalties. Measures included lockdowns, closure of schools and universities and obligatory face mask usage. The severity of the restrictions was often modified in accordance to shifts in the infection figures, resulting in a “stop and go” approach. Furthermore, the sometimes patchwork-like nature of the German execution of laws meant that judgment regarding implementation was left to the discretion of each individual federal state. This in turn, subsequentially led to different restrictions being put in place in different states (Kuhlmann et al., 2021).

Kuhlmann et al. (2021) support our decision of comparing Germany and Sweden as the countries are similar in their basic structural characteristics but have reacted rather differently to the exact same external stimulus being COVID-19. Our goal is not to identify whether one approach is better than the other but to find out whether the different framing of the crisis has impacted the handling of the crisis in family businesses in both countries. Additionally, it has been pointed out in recent research concerning family

18

firms’ decision-making that the political and economic context of countries has been underutilized as a point of reference (Llanos-Contreras et al., 2020). With this in mind, our approach of using two countries with differing governmental responses to the pandemic, further helps in filling a gap in research concerning SEW and its FIBER dimensions.

A recent study of note that looks at how different governments deal with the crisis caused by the pandemic has done so using a prospect theory based lens (Hameleers, 2021). The study focuses on the concepts of loss and gain-framing and their use by governments in how they react and communicate the crisis to the public. They associate gain-frames, that is framing the situation and the choices the individual has in a way that emphasizes positive outcomes such us the lives saved with risk-aversive strategies in combating the pandemic. Risk-aversive in this context is described as the approach that aims to preserve the status quo (Hameleers, 2021; Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Hameleers (2021) further adds that a gain-framing is also associated less with changing the emotional states of the public. Thus, following this reasoning we can link Sweden to a gain-framing of the pandemic, as their initial response and strategy relied on preserving the pre-pandemic status quo. The country framed the situation as a “marathon” where the actions of the individuals can help save lives, but have to do so over an extended period of time through consistent but sustainable milder restrictions (Yan et al., 2020).

This differing approach can also be observed in the OxCGRT (COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) by Hale et al. (2020), a systematic tool used to trace and visualize government measures related to COVID-19 over time. Even if the data provided by Hale et al. (2020) is not ideally suited to compare Sweden and Germany as the authors treat restrictions and recommendations homogeneously, the “heat map” of the OxCGRT visualizes the unique nature of the Swedish response over time very accurately.

Conversely, a loss-framing of the situation that is focused on the potential loss of life caused by the pandemic is associated with negative emotions and a sense of fear and powerlessness. As Hameleers (2021) points out, if a loss-framing triggers this sense of powerlessness and fear, it will cause an increase in the support for stricter governmental intervention and measures. Based on the previously described German approach to the crisis, we link the picture of the crisis the German government has communicated to their public to a loss-framing. As a result of this approach German family firms may have

19

experienced the associated negative emotions that could be potentially triggered by the loss-framing. Hameleers (2021) adds that if these negative emotions are triggered, they can influence decision-making during the pandemic. Swedish family firms, on the other hand, may have been impacted less emotionally due to their government’s framing having closer ties to a gain framing.

In summary, our approach incorporates the factor of differing governmental framings and responses to the crisis situation brought about by the pandemic in order to investigate if and how they influence family business decision-making and SEW prioritization by simultaneously studying German and Swedish family firms over a three-year period. Previous research shows that the political context impacts family firm decision-making (Llanos-Contreras et al., 2020). Furthermore, research focusing on the effects of differing governmental framings of the crisis situation caused by the pandemic has shown that a loss-framing of the situation, for example illustrating the situation through the potential loss of life, is associated more with feelings of powerlessness and fear. This in turn may lead to stricter measures being applied and supported (Hameleers, 2021). On the other hand, a gain-frame that characterizes the situation and the potential course of action through the number of lives that can be saved by taking on certain measures was associated with more support for risk-aversive interventions. Thus, these findings link the effect of differing governmental restrictions and framing of the crisis to differing impacts on emotional states. We intend to investigate if these differing governmental restrictions will affect SEW and which FIBER dimensions are prioritized by family firms during the crisis.

2.6 Propositions and Model Construction

In the previous literature review, we first covered the overall topic of family businesses, noting their unique status as the most widespread form of business worldwide. We furthermore have also discussed how family firms have been shown to make decisions using not only financial performance as their frame of reference, but rather that of family specific non-economic goals (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Given the heterogeneity of family businesses as well the nature of their relationship to outside stimuli, it has been shown that there is still ample room for new research. We intend to contribute to the literature discussing the phenomenon of family firm decision-making through the lens of SEW as conceptualized through the FIBER dimensions.

20

Specifically, we take on an approach that relies on the concept of SEW, as it has been conceptualized from its inception to help explain the drivers of family firm decision-making (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). SEW broadly defines these drivers as the affective utilities of family firms. The concept has repeatedly been the subject of calls for better operationalization in research, which we intend to answer by using a recently proposed version of the FIBER model (Swab et al., 2020). This approach not only breaks SEW down into the five FIBER dimensions, but builds on previous critiques of the construct, also categorizing them as either necessary or sufficient factors in contributing to the willingness and ability of family firms to preserve and pursue SEW. We incorporate this approach not only to formulate our definition for family businesses, but also use it as the basis of our proposed model as its framing of the FIBER dimensions accounts for both family firm heterogeneity and for the relationship between the dimensions themselves. Furthermore, SEW and its dimensions as expressed through FIBER have recently been shown to potentially shift over time (Cleary et al., 2019). Further, it has been suggested that the FIBER dimensions might be affected by outside stimuli, a relationship that is yet to be explored in research. Particular attention in this case should be paid to crises such as the one initiated by the COVID-19 pandemic (De Massis & Rondi, 2020). A similar notion has also been expressed by Swab et al. (2020) who propose that the family firms’ prioritization of the FIBER dimensions shift dynamically and differ between firms. Our proposed model is illustrated in the figure below (Figure 2).

21

The study follows a content analysis approach in line with the one utilized by Cleary et al. (2019), looking at statements to shareholders in annual reports published by publicly listed family firms. We postulate that the FIBER dimensions, as expressed through the annual reports, will not be all present in a stable form over the studied time period of three years, but will change dynamically. Furthermore, we study family firms facing a crisis situation due to the topic’s continued relevance both in connection to family firms and the COVID-19 pandemic (De Massis & Rondi, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020). We have already discussed how the FIBER dimensions have been demonstrated to potentially shift over time without the influence of a crisis on the scale of the pandemic (Cleary et al., 2019). This change over time has also been shown to differ on a firm-to-firm basis, even when controlling for several contingency factors at once, further giving credit to family firms being heterogenous (Cleary et al., 2019). On the other hand, family firms facing a crisis have shown to behave differently than their non-family peers. Previous research concerning the effects of a crisis situation on family firms has attributed this differing behaviour to their SEW-guided decision-making (Casillas et al., 2019; Faghfouri et al., 2015; Rivo-López et al., 2020). However, for the most part these studies treat SEW and its dimensions as stable constructs that do not change over time. It has further been noted how a focus on SEW-based priorities diminishes as the firm is passed down through multiple generations and how the focus from SEW may shift to a focus on traditional financial goals when the crisis hits (Minichilli et al., 2016; Rivo-López et al., 2020). How specific dimensions of SEW shift in response to a given crisis has yet to be explored, the relevance of which has been recently brought into focus in connection to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic (De Massis & Rondi, 2020). The crisis has put an immense emotional pressure on family firms. Early studies have shown the roots of cultural change taking place in response, with solidarity driving the relationship between the family and its stakeholders (Kraus et al., 2020). On the other hand, De Massis and Rondi (2020) highlight the potential negative effects the pandemic may have on the SEW of family firms, as they are forced to make decisions that can undermine several of its dimensions. Thus, we propose that family firms will prioritize and put emphasis on certain aspects of their SEW corresponding to specific FIBER dimensions when faced with a crisis. Our approach of using content analysis allows us to observe this change in prioritization through looking at the communication conducted by the firms in their annual reports. Following previous research in this approach (Cleary et al., 2019) we assign specific

22

phrases and expressions to corresponding FIBER dimensions to measure how the focus on these dimensions shifts before and during the crisis period. Thus, we suggest that the crisis generated by the pandemic will result in a shift in the prioritization of the FIBER dimensions that determine the willingness and ability of family firm decision-makers to pursue and preserve SEW. We further propose that this shift will cause certain dimensions of SEW to come to the forefront during the crisis, while other dimensions will be less prevalent, as expressed by the family firms’ communication through their statements to shareholders in their annual reports. We test these assumptions in the context of family firms in two different countries, Sweden and Germany. Doing so we are able to compare our results to see the possible effects the different governmental responses may have caused for each respective country’s prioritization of the FIBER dimensions. This allows us to answer both our research questions. This relationship is also shown in our own proposed model (Figure 2). With this in mind, we arrive at our first proposition.

Proposition 1: The crisis will impact the prioritization of the FIBER dimensions.

The following propositions are formulated based on our predictions on how the prioritization of the FIBER dimensions of SEW will be impacted by the crisis. We formulate these propositions following the willingness and ability categorisations of the FIBER dimensions (Swab et al., 2020). We begin with discussing our assumptions connected to the ability dimensions of family control and influence (F) and renewal of

family bonds through dynastic succession (R). This is then followed up by the discussion

of our proposition tied to the willingness dimensions of family members’ identification

with their firm (I), binding social ties (B) and emotional attachment (E). We conclude by

outlining our proposition related to how SEW may be prioritized differently during the crisis between Swedish and German family firms.

In their content analysis coding scheme concerning the FIBER dimensions Cleary et al. (2019) assign elements concerned with family members making decisions, facing issues and references to their appointments or resignations from the board or managerial positions to the dimension of family control and influence (F). In their study, which was focused on a period devoid of any major crisis on the scale of the current one, they found the “F” dimension to appear only at low levels. Furthermore, crisis situations have been proposed to unite the efforts of family owners and push regular points of contention between them to the side-lines even in cases of dispersed family ownership structures

23

(Minichilli et al., 2016). Swab et al. (2020) propose that this dimension is necessary for SEW to exist within a firm. Its existence, however, only provides the ability for SEW to be pursued and does not by itself indicate that SEW preservation and pursuit will be the goal of family firm decision-making. They further add that this dimension as a result would not be one to change and be prioritized by family firms as a reaction to different contingencies. Thus, we propose that the dimension of family control and influence will be prioritized less by family firms during the crisis period and thus will not be impacted by the crisis.

The dimension of renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession (R) was shown in Cleary et al.’s (2019) work to be the one with the consistently lowest representation among all five FIBER dimensions across the studied firms. We expect this dimension to possibly receive even less attention in the reports published during the crisis. Succession in family firms has already been shown to rely on the existence of several factors to succeed, while also being threatened by a multitude of potential pitfalls, even without the looming threat of a crisis situation (De Massis et al., 2008). Furthermore, necessary preparations and willingness on both the incumbent’s and potential successor’s side have been shown to be needed for a well-executed succession (Sund et al., 2015) which could potentially be interrupted by the sudden onset of the crisis. Finally, like in the case of the dimension of family control, we expect this dimension to fall in priority for family firms during the crisis period due to it contributing only to the ability of firms to purse SEW and not the willingness to make SEW-focused decisions (Swab et al., 2020). These points combined with the already low level of attention both ability dimensions have received in previously studied reports lead us to the proposition that the crisis will not impact family firms’ prioritization of the ability dimensions of “F” and “R”.

Proposition 2: The crisis will not impact the prioritization of the ability dimensions of

family control and influence and renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession.

Next, we move on to the willingness dimensions. In the conditional FIBER model of Swab et al. (2020) dimensions falling under the willingness category are proposed to be the drivers behind family firm heterogeneity. They are outlined as being more likely to shift and differ over time as different dimensions are prioritized in response to different contingencies.

24

Cleary et al. (2019) found the dimension of family members’ identification with their firm (I) to be the most prevalent and second most prevalent in the two firms they studied respectively. They further link this dimension to elements in the reports that illustrate the day-to-day operational role of the family as well as its history and even family bereavement. As family business crisis literature has shown the dimension of family identification plays a key role in the unique response that family firms have to crisis situations. It has been attributed as one of the drivers behind family firm job stability during crises (Rivo-López et al., 2020). Furthermore, family firms have already been shown to respond to the crisis caused by the pandemic through a strong push for solidarity between them and their employees and suppliers, resulting in cultural change that strengthened bonds to the firm (Kraus et al., 2020).

The dimension of binding social ties (B) has similarly been shown to be both a dominant element in the chairman’s statements studied by Cleary et al. (2019) and a driver behind family firms’ crisis management approach (Rivo-López et al., 2020). Like the previous dimension we expect binding social ties to have a potentially more dominant role for family firms during the crisis. This would line up with the earlier observed increase in employee commitment during the crisis (Kraus et al., 2020) as well as the perceived importance and SEW-related value family firms derive from sustaining and strengthening their ties to employees during a crisis in order to preserve their long-term vision (Rivo-López et al., 2020).

While the dimension of emotional attachment (E) has been shown to appear in a low amount over the observed period in the work of Cleary et al. (2019), we expect this dimension to be potentially pushed to the forefront during the crisis. In their coding scheme Cleary et al. (2019) tie this dimension to the element of emotive expressions aimed at threats or competitors and the element of the family in relation to decision-making choices. Emotions have been shown to permeate through family members’ decision-making, which combined with family members’ close identification with the firm often mean that these emotions closely affect the firm itself (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Morgan & Gomez-Mejia, 2014). Furthermore, as family firms often rely on their unique culture that stems from the controlling family’s values and influence (Hall & Nordqvist, 2008), we expect that the cultural change that is generated as a reaction to the