J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

K n o w l e d g e D e v e l o p m e n t

A dual perspective on Small Firms’ training and development needs

Master thesis within: Business Administration Author: Malin Holfve

Maria Pekár Tutor: Annika Hall Jönköping: May 2010

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to all the people who have contributed to make this thesis possible. First of all, we would like to thank all the interviewees who have given their precious time to share their experiences with us.

Secondly, sincere gratitude is given to our tutor, Annika Hall, who has been both inspiring and encouraging as well as contributing with rewarding discussions that has brought this research great value.

Furthermore, a thank is expressed to all our fellow students, for their feedback and com-ments that has brought us forward throughout the process.

Finally, we would like to thank our bellowed families who have supported us during this time.

_________________ _________________ Malin Holfve Maria Pekár

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Knowledge Development- A dual perspective on Small Firms’ training and development needs.

Author: Malin Holfve

Maria Pekár

Tutor: Annika Hall

Date: Jönköping, May 2010

Key words: Knowledge, Training, Development, Small firms, Training vendors, Net-working, Grounded Theory, Trust, Absorptive capacity

Abstract

Background: Due to the increasing global competition managers must realize the im-portance of competitive advantage. This can be done by reconsider how new knowledge should be acquired into the organization. The importance of new competence creation is well known as a factor for longitudinal suc-cess for companies. There is a growing trend in outsourcing human re-sources activities that used to be in-house. There are numerous training vendors active on the market offering training and development opportu-nities to small firms. It can therefore be questioned how well the programs offered by the training vendors suites the needs of small firms.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to investigating the perceived training and development needs for small firms. This to understand and overcome the differences in the perception of small firms’ needs, between training vendors and small firms.

Method: The research approach of this study is inspired by Grounded theory. Ten in-depth interviews have been performed, four with training vendors and six with small firms. The findings where then coded and categorized to answer the research questions and purpose of the research.

Conclusion: From this research it can be seen that both small firms and training ven-dors do understand the need for training and development of small firms. The areas where training and development is needed for small firms can be summarised to fields of general business management and business specific knowledge. However, this research also identifies barriers that prevent small firms from attending external training. These barriers are cost, time, relevance, pride, flexibility and suitability. Time and cost are the most commonly men-tioned barriers, but not the primary barriers that training vendors and small firms should focus on overcoming. Instead we argue that, the efforts should be on the attitude driven barriers: relevance, suitability, flexibility and pride. If you change the attitude among small firms towards training, the perceived benefits will become larger and therefore cost and price will become less important. If the small firms and the training vendors co-operate these barriers could easier be decreased. This could be done by ensuring that the training results in practical tools that the firms use and that they work on building a trustworthy relationship. This will help the small firms to see the relevance and the suitability of the courses offered and the training vendors to understand how to make the courses appear more relevant and suitable to the small firms.

Magister uppsats i Företagsekonomi

Titel: Kunskapsutveckling- Ett tvåsidigt perspektiv av småföretags tränings- och utvecklingsbehov

Författare: Malin Holfve Maria Pekár Handledare: Annika Hall

Datum: Jönköping, May 2010

Nyckel ord: Kunskap, Träning, Utveckling, Småföretag, Externa utvecklingsleverantö-rer, Nätverkande, Grundad teori, Tillit, Absorberande Kapacitet

Sammanfattning

Bakgrund: I och med den ökade globala konkurrensen, måste företagsledare förstå vik-ten av att inneha och bevara en konkurrens fördel. Detta kan göras genom att fokusera på hur kunskap kan tas in i organisationen. Vikten av kompe-tens utveckling är en välkänd faktor för långsiktig framgång för företag. Det finns en ökad trend att lägga ut ansvaret för human resources på externa fö-retag, vilket tidigare sköttes inom företaget. Det finns ett stort antal externa utvecklingsleverantörer på marknaden. Det kan därför ifrågasättas hur väl programmen, som de externa träningsleverantörerna erbjuder, passar med behoven hos småföretagarna.

Syfte: Syftet med studien är att undersöka uppfattningen om tränings- och utvecklingsbehov hos småföretagare. Detta för att få en förståelse av småföretagarnas behov och komma över skillnaderna i uppfattningarna mellan externa utvecklingsleverantörer och småföretagare. Metod: Forskningsansatsen till den här studien är inspirerad av Grundad teori. Tio djupintervjuer har genomförts, fyra stycken med externa utvecklingsleveran-törer och sex stycken med småföretagare. Det empiriska materialet har or-ganiserats genom kodning och kategorisering enligt Grundad teori.

Slutsats: Från den här studien kan det ses att både småföretagare och externa utveck-lingsleverantörer ser behovet av träning och utveckling i småföretag. De områden där träningsbehov är identifierade kan summers till generell före-tagsekonomi och specifik kunskap inom företagets bransch. Genom denna studie har dock barriärer som motverkar träning och utveckling i småföretag identifierats. Barriärerna är: kostnad, tid, relevans, stolthet, flexibilitet och lämplig-het. Tid och kostnad är de mest nämnda barriärerna, men dock inte de barri-ärer som primärts bör fokuseras på. Istället anser vi att kraften skall fokuse-ras på att minska de attityd drivna barriärerna: relevans, lämplighet, flexibili-tet och stolthet hos företagarna. Om attityden hos småföretagarna ändras vad gäller träning så kommer den uppfattade fördelen av träning att öka, därmed minskar vikten av barriärerna kostnad och pris. Dessa barriärer kan lättare överbyggas om småföretagarna och de externa utvecklingsleverantö-rerna samarbetar. Samarbetet kan ske genom att fastställa att det praktiska verktygen, utvecklade av de externa utvecklingsleverantörerna, används av småföretagarna och att en tillförlitlig relation byggs. Detta skulle hjälpa små-företagarna att se relevansen och lämpligheten i de erbjudna kurserna och de ex-terna utvecklingsleverantörerna skulle få en förståelse i hur man kan få kur-serna att framstå som relevanta och lämpliga för småföretag.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.1.1 Small Business ... 2 1.1.2 Training Vendors ... 2 1.2 Problem ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 3 1.4 Delimitations ... 3 1.5 Disposition ... 42

Methodology ... 5

2.1 Grounded Theory ... 5 2.2 Research Approach ... 5 2.3 Data Collection ... 62.3.1 Sampling and Interviews ... 6

2.3.2 Interviews ... 6 2.3.3 Frame of Reference ... 8 2.4 Data Analysis ... 8 2.5 Data Quality ... 9 2.5.1 Relevance ... 9 2.5.2 Function ... 10 2.5.3 Modifiability ... 10

3

Theoretical Framework ... 11

3.1 Knowledge ... 113.1.1 Knowledge to Create Competitive Advantage ... 11

3.1.2 Tacit Knowledge and Explicit Knowledge ... 11

3.2 Knowledge Management ... 12

3.3 Training and Development Opportunities ... 12

3.3.1 Formal Training ... 13

3.3.2 Informal Training- most preferable by small firms ... 14

3.3.3 Networking- an additional method for development... 14

3.4 Selection Process of Knowledge ... 16

3.4.1 Proactive ... 16

3.4.2 Reactive ... 16

3.4.3 Trust ... 16

3.5 Absorptive Capability ... 17

4

Empirical Findings ... 18

4.1 Training Vendors Perspective ... 18

4.1.1 Management of Small Firms ... 18

4.1.2 Identified Training and Development Needs for Small Firms ... 19

4.1.3 Types of Training and Development Opportunities Offered ... 19

4.1.4 Identification and Development of New Training Opportunities ... 20

4.1.5 Client-Vendor Relationship ... 21

4.1.6 Future Training and Development Needs for Small Firms ... 22

4.2.1 Identified Training and Development Needs for Small Firms ... 22

4.2.2 Methods used by Small Firms to Increase Knowledge ... 23

4.2.3 Training and Development Opportunities offered to Small Firms ... 25

4.2.4 Small Firms’ use of Training Vendors ... 26

5

Analysis ... 28

5.1 Training and Development Needs for Small firms ... 28

5.2 Barriers to Training and Development ... 29

5.3 Small Firms’ Methods used to Increase Knowledge ... 30

6

Discussion ... 32

6.1 Future methods to Overcome Barriers- A dual perspective ... 32

7

Conclusion ... 35

7.1 Further studies ... 36

References ... 37

Tables

Table 2-1 Themes for in-depth interviews ... 7Table 2-2 Categories of Empirical Data ... 9

Figures

Figure 5-1 Small Firms Training and Development needs ... 281

Introduction

This chapter is an introduction to our study. The background introduces the concept of knowledge and why training is important to small firms to become sustainable in the market. The background is followed by a problem discussion that results in our research questions and to the purpose of the study.

1.1 Background

“Knowledge is the primary mean for wealth creation for a rapidly growing number of individuals, firms and economies.”

- Huggins & Izushi, 2007, p. 1 Due to the increasing global competition managers must realize the importance of compet-itive advantage, and how to sustain the advantage gained (Ulrich & Lake, 1991). Tradition-ally sustaining competitive advantage has been achieved through focusing on financial, stra-tegic and technological capabilities. However, Ulrich and Lake (1991) argue the importance of a forth aspect; organizational capability. Hence, sustainable competitive advantage is

achieved by focusing on how to manage people. Furthermore, Inkpen (1998) argues that firms have to reconsider how new knowledge should be acquired into the organization to react to the increased global competition. The management and the creation of new know-ledge are just as important for small firms as it is for large corporations (Wong & Aspin-wall, 2004). However, most research on knowledge management focus on large organiza-tions (McAdam & Reid, 2001). Hence, there is relatively little information available on knowledge management within small businesses.

Organizational learning has been a topic of interest since 1979 when Argyris and Schon published their book Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective (Popper & Lippshitz, 1998). Since then, many have taken interest in this field. According to numerous research-ers of today, knowledge management can be seen as the primary tool for sustaining com-petitive advantage and a mean to distinguish the organization from their competitors (Grant, 2002, MacKinnon et al, 2002, Patriotta, 2003 and DeTienne, Jackson, Castleman & Parker, 2004 cited in Omerzel & Antoncic 2008).

According to Inkpen (1998) the value of knowledge is dependent on the organization. For knowledge to be useful for the organization it has to be acquired, transferred and integrated in the everyday work (Inkpen, 1998). There are multiple approaches to acquire knowledge. Traditionally, these are divided into formal and informal training, where the former refers to external training that has been outsourced to training vendors. The latter is in the form of on the job training such as; learning by doing, learning by copying, learning by experi-ment and learning from customer and supplier feedback (Patton et al., 2000 cited in de Kok 2002). According to de Kok (2002) it is well known that smaller firms provide less formal training compared to the larger firms. There has, however, been an increase in train-ing provided by smaller firms over the last decade (de Kok, 2002).

The choice of method to acquire knowledge and what type of knowledge to acquire is de-pendent on the company. When knowledge is acquired it is, according to Pate, Martin, Beaumont and McGoldrick (2000) important to understand how the knowledge can be used in a practical sense in the daily business. The rate with which the new knowledge is in-corporated into the company depends on the absorptive capacity of the firm (Inkpen, 1998).

1.1.1 Small Business

Small and medium sized businesses (SME) are considered to be the company form that contributes the most to the growth and economic development of a country (SOU 1995:08). In addition, Thassanabanjong, Miller and Marchant (2009) argue that SME’s are the economy’s engine room in established and rising nations. In Sweden 99 % of all the companies are small businesses (FöretagarFörbundet, 2010). According to the European Commission’s recommendation (96/280/EG)a company is considered to be a small busi-ness when the company has between 10-49 employees, the annual turnover falls below sev-en million Euro or the balance sheet total falls below five million Euro (Europa, 2010).

1.1.2 Training Vendors

Today there are multiple actors on the market that provide firms with training and devel-opment possibilities. Among the training vendors there are both public actors as well as private actors. The training vendors are providing different types of training and develop-ment possibilities for small firms. Some organizations focus on general business manage-ment developmanage-ment, while others provide specific advisory and information regarding areas within the training vendors’ core competence. Apart from formal training, many of the training vendors offer additional resources such as financial aid, information and network-ing possibilities (SOU 1998:77).

1.2 Problem

The importance of new competence creation is well known as a factor for longitudinal suc-cess for a company. According to SOU 1998:77 there exist evidence of the correlation be-tween new knowledge creation and small business growth. As stated by Huggins and Izushi (2007, p.1) “Once a firm is excluded from the knowledge race, it will sooner or later witness a decline in performance and profits… “ . Even if the importance of new knowledge is known, many en-trepreneurs and managers do not focus enough on the management of knowledge acquisi-tion (Inkpen, 1998: Omerxel & Antoncic, 2008).This is evident in small firms, since the most common reason for small business failure is due to the lack of knowledge, or as Cart-er and Van Auken, (2006) and Gibb and Webb, (1980) claims, due to “Business Incompe-tence” (cited in Chirico, 2008).

Reasons for why small firms lack focus on training are discussed by many. De Kok (2002) highlights the fact that small firms tends to have a shorter time horizon, low awareness of available courses and a higher opportunity cost for training in comparison to larger firms. Another factor identified by the report SOU (1995:08) is the importance to see a clear ben-efit of the training for the company. Inkpen (1998) agrees with this argument, as he claims that unrelated knowledge has limited value to the company.

There is a growing trend in outsourcing human resources activities that used to be in-house (Cook, 1999 cited in Gainey & Klass, 2003). In recent years the outsourcing of the strategic areas of HR such as training and development has started to increase (Cook, 1999 cited in Gainey and Klass 2003). Today there are many vendors supplying small firms with training opportunities, some of these are publicly owned and others are private. These organiza-tions exist to provide the companies with expertise and training, both in businesses processes and industry specific areas.

To get useful training experience from outsourcing, the programs have to be tailored and unique for each firm’s needs (Noe, 1999 cited in Gainey and Klaas, 2003). It can therefore

be questioned how well the programs offered by the training vendors suites the actual needs of the small firms. This leads to our research questions:

1. What are the perceived training and development needs for small businesses from the perspective of training vendors?

2. What are the perceived training and development needs for small businesses from the perspective of the owners?

3. How well are the training and development opportunities, offered by external ven-dors, fitted with the actual training needs of small businesses?

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigating the perceived training and development needs for small firms. This to understand and overcome the differences in the perception of small firms’ needs, between training vendors and the small firms.

Clarification- By interviewing both sides a gap-analysis can be conducted to see if training vendors’ perception of small businesses needs is coherent with small businesses identified needs.

1.4 Delimitations

This study will focus its research on a limited number of small firms and training vendors active on the Swedish market. Due to the formation of this study, the result is not to gain generalizability instead the focus is to explain and support the precise finding of this study.

1.5 Disposition

This chapter is an introduction to our study. The background introduces the concept of knowledge and why training is im-portant to small firms to become sustainable in the market. The background is followed by a problem discussion that results in our research questions and to the purpose of the study.

This chapter covers the research method that is used for this study. Firstly, it explains the research approach used which is inspired by Grounded theory. This is followed by the data anal-ysis and an evaluation of the data quality.

The purpose of this chapter is to give a presentation of the theoretical framework underlying this research. The concept of knowledge is presented together with an extensive framework of how knowledge can be acquired and attained for a small firm.

In this section the empirical data collected is presented. Since our research is investigative from a dual perspective the empiri-cal material will be divided into two sections. The first section will present the empirical finding from the training vendors’ perspective followed by the findings from the managers of the small firms.

In this chapter theories are applied to the empirical findings re-ceived from the semi-structured interviews with the training vendors and the small firms. To facilitate the interpretation of the analysis a model has been developed by the authors.

The purpose of this study is to investigating the perceived train-ing and development needs for small firms. This to understand and overcome the differences in the perception of small firms’ needs, between training vendors and the small firms. A conclu-sion is in this chapter drawn by the use of the analysis of the empirical findings to answer the research questions and through this fulfill the purpose.

Theoretical Framework Introduction Research Method Empirical Findings Analysis Discussion Conclusion

2

Methodology

This chapter covers the research method that is used for this study. Firstly, it explains the research approach used which is inspired by Grounded theory. This is followed by the data analysis and an evaluation of the data quality.

2.1 Grounded Theory

Traditionally, scientific research methods has put a lot of focus on verifying and testing theories and in that way provide the theories with scientific support (Hartman, 2001). Grounded theory, however, is a method that in a more inductive way generates new theo-ries (Hartman, 2001). This theory was first developed by Barney Glaser and Anseim Strauss in the end of 1960’s (Patel & Davidson, 2003).

Grounded theory is a method where one is not allowed to start from pre-known theory, in-stead Grounded theory starts with the empirical data collection (Hartman, 2001). This to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data instead of limiting the data (Hartman, 2001). To ensure that the data controls the results the research questions are formulated in an open manner to enable reconstruction, if the data collection process requires this (Patel & Davidson, 2003). The data collection and the creation of theory are done simultaneously (Patel & Davidson, 2003). In addition, all the material is then written down in order to formulate a local theory (Patel & Davidson, 2003). This local theory is the empirical find-ings that are categorized into different codes (Patel & Davidson, 2003). The individual code is a category and all the empirical puzzle parts can then be placed in separate categories (Patel & Davidson, 2003). These codes are found during the collection, summarizing and by repeatedly reading the material (Patel & Davidson, 2003). Initially, these codes are open and unrelated but will eventually be placed in a category and then more data can be col-lected (Patel & Davidson, 2003). This process is done until the different codes do not change and hence theoretical saturation is reached (Patel & Davidson, 2003). The idea is that a theory is gained in a correct way since it is founded on data and one therefore have good reasons to believe that it describes the reality correctly (Hartman, 2001).

2.2 Research Approach

For this research a qualitative study has been conducted, which is in line with the proposal from Heneman et al. (2000, cited in de Kok, 2002) regarding how to research the area of training and development needs within small firms. Theory and reality can be related to each other using different research approaches (Patel & Davidson, 2003). According to Pa-tel and Davidson (2003), there are three ways that are commonly used within scientific work are deduction, induction and abduction.

When doing research in a deductive way one is working from pre-existing theories and makes conclusions regarding specific events from the theory. The opposite of a deductive approach is an inductive research approach. When using an inductive approach one is studying the research objective without having theory as the foundation. Hence, one is formulating the theory from the collected empirical material. (Patel & Davidson, 2003) The third research approach, abduction, is a combination of deduction and induction. The first step in the abduction research approach is to go out and collect data. The data is then interpreted with the help of theory. This is just like the inductive research method. The

next step in the abductive approach has a more deductive influence. Here, the new know-ledge is tested again by collecting additional data to test the findings and research questions are formulated. To interpret the newly collected data, new theories are developed. This process of collecting data and check with theory to collect data again is a continuous cycle to be performed until saturation is achieved. (Patel & Davidson, 2003)

An abductive research approach is suitable with Grounded theory, since this research me-thod also allows the researcher to go back and forth from the empirical data and the theory. Hartman (2001) uses the expression that the grounded theory is “the golden middle way”; it is an inductive method where deductive elements are implemented.

For this study and an abductive approach was chosen. For our research we have chosen to only take inspiration from the methodology of Grounded theory. This due to the fact that we already have basic knowledge in the area of knowledge creation and its importance. The knowledge within the specified research area was, however, limited. Hence, we had some pre-knowledge on theory and therefore Grounded theory cannot be fully implemented. By using Grounded theory as an inspiration to our qualitative abductive research this explains our choices of methods to collect; interpret and analyze the empirical data.

2.3 Data Collection

When collecting data for the research, using aspects of the Grounded theory, different elements and resources can be used. According to Corbin and Strauss (1990) any data col-lection method is suitable when using Grounded theory as long as it enlightens the research questions of the study. Therefore, for this study we enquire our information both from in-terviews, government document as well as books and academic articles.

2.3.1 Sampling and Interviews

Since we are looking for the dual perspective of the small firms’ need for training and de-velopment, the empirical data was collected through a number of in-depth interviews with parties from both sides of the perspectives. The interview objects have been selected through the use of snowball sampling. Snowball sampling, is when a study sample is gained through referrals made by those who share or know others who possesses characteristics and knowledge that is of interest for the research (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). This me-thod is suitable for this study since a certain understanding and interest within the field of knowledge creation among the interviewees is necessary for the interviews to be rewarding and useful for the study.

The sampling for our research started with informal conversations with local entrepreneurs at Jönköpings International Business School. With their help, training vendors as well as some small firms were identified. From the training vendors’ homepages potential inter-view objects were identified and contacted in order to investigate potential interest and re-levance in participating in the study.

To increase interest and incentive to participation, interview objects were offered a copy of the final report as well as full anonymity.

2.3.2 Interviews

The data for this study was, as previously discussed, mainly obtained from 10 depth in-terviews. With the use of themes rather that questions, semi structured interviews was per-formed. Performing semi-structured interviews, the themes and questions can be altered to

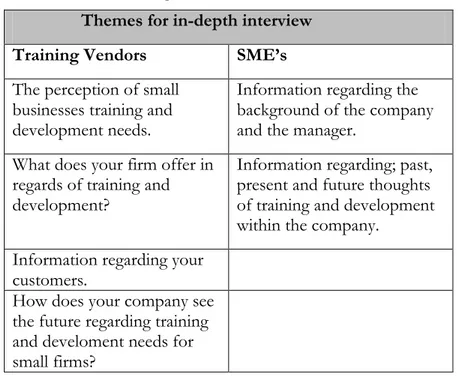

an order that suites with the conversation (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009). This enables the interviewees to talk freely and not be too limited to the initial ideas and though-ts of the researchers. The themes for the interviews were adjusted for the two different perspectives, one for the group of training vendors and a different set for the small firms. See Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Themes for in-depth interviews

Themes for in-depth interview

Training Vendors SME’s

The perception of small businesses training and development needs.

Information regarding the background of the company and the manager.

What does your firm offer in regards of training and development?

Information regarding; past, present and future thoughts of training and development within the company.

Information regarding your customers.

How does your company see the future regarding training and develoment needs for small firms?

The interviews conducted were primarily face-to-face interviews. However, due to geo-graphic positioning of two of the interviewees, there was a need for telephone interviews. The interviews took between 30 and 45 minutes depending on the interest of the intervie-wee and the depth of the conversation.

To ensure that the result of the interviews was relevant to the research, the need for good communication between interviewer and interviewee was essential, this can, according to Patel and Davidsson (2003), be done if the interviewee feels motivated and comfortable in the interview setting. To ensure the motivation and comfort, the interviews were held in the office of the interviewee. This was done both to have a familiar atmosphere which in-creases the comfort level of the interviewee, and also since the office has access to addi-tional relevant information that the interviewee wants to share during the interview. To fur-ther facilitate the discussion, opended, follow-up questions were used in order to en-courage the interviewee to expand their line of thought.

To capture the entire conversation and to facilitate as well as increase the validity of the in-terpretation, the interviews were recorded and notes were taken as a back-up. Each inter-viewee was asked for permission to record the conversation with the argument that this would reduce the risk of misinterpretations.

After each conversation the interviewers had a session of review, where the interview was discussed to get an indication that both interviewers had understood and interpreted the main topics of the interview in a similar way.

To ensure the validity of the interviews, the recoding of the conversations were listened to again in order to capture additional information. In addition, since the interpretation of the interviews is of high relevance to our research, the findings from the interviews were sum-marized. In the cases were the interviewees asked to validate their interview, the summary was sent for validation. This will increase the relevance and accuracy of the analysis as well as ensure that the interviewees feel satisfied with their contribution.

2.3.3 Frame of Reference

The collection of second hand data was conducted in two steps in accordance to Grounded theory. The first round was conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the market situa-tion on training and development opportunities available today, while the second round of literature review was done to facilitate the interpretation of the empirical data collected. In the first round, the data collected was primarily from different government reports such as Kompetens i småföretag (SOU 1998:77) and Kompetensutveckling i Stockholmsregio-nens småföretag (SOU 1995:08). This information together with articles from academic journals such as International Small Business Journal and Journal of Knowledge Manage-ment were the foundation and inspiration to our research.

After the empirical data was collected a second literature reviewed was conducted to reach an understanding of the new data and to further analyze the answers. In this search, aca-demic journals were the primary resource. As an additional source, books by important re-searchers within the field were used such as; Competing for knowledge: Creating, connect-ing and growconnect-ing by Huggins and Izushi (2007). This, to gain a deeper understandconnect-ing of the theoretical perspectives.

2.4 Data Analysis

“Data are nothing more than ordinary bits and pieces of information found in the envi-ronment.”

- Merriam, 1998, p. 69

Complete objectivity is hard to gain when analyzing qualitative data since no human goes through situations without evaluating it (Merriam, 2002). According to Grounded theory, the best method to interpret the collected empirical findings is through coding and categorizing of the content (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Since coding is an interpretation by the authors, complete objectivity is impossible to achieve. However, by reflection on the matter the subjectivity might be decreased.

The process of identifying the codes for this research was done through the use of the summaries compiled from each interview. These where read, cut into pieces and sorted in-to groups of comments concerning the same in-topic. From these codes, categories for inter-pretation emerged. The categories identified from the coding of our empirical data can been found in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2 Categories of Empirical Data

Categories of Empirical Data

Training Vendors Small Firms

Management of small firms Indentified training and development needs of small firms

Identified training and development needs of small firms

Methods used by small firms to increase knowledge

Types of training and development

op-portunities offered Training and development opportunities of-fered to small firms Identification and development of new

training opportunities Small firms’ use of training vendors Client-vendor relationship

Future training and development needs for small firms

To create an analysis that is interpretable for the readers, the codes and categories that the data have been divided into, is the base for the structure of the presentation and analysis of the empirical material, this in accordance with the view of Patel and Davidsson (2003). The two perspectives are presented separately in the empirical findings sections to illustrate their separate view. Later on in the analysis the two perspectives are then compared and analyzed together with the theory. This in order to illustrate similarities and differences in the perception of training and development needs for small firms. This analysis leads to a conclusion fulfilling the purpose of the study and answer the research questions.

2.5 Data Quality

When evaluating the quality of data, common parameters often used are validity, generali-zeability and reliability. However, according to Hartman (2001), these parameters are not preferable when using Grounded theory. The prime reason why these parameters are not suitable is that the objective of Grounded theory is not to explain other domains than the ones presented and explored in the study (Hartman, 2001). This view applies to our study, since we have an investigative purpose where a limited number of qualitative interviews were performed until a sense of saturation is achieved. Using this research approach the re-sults of this study does not aim to achieve neither statistical validity nor generalizability. Instead of the parameters previously mentioned, Hartman (2001) argues that the quality of the research should be evaluated from the criteria: relevance, function and modifiability.

2.5.1 Relevance

According to Hartman (2001) relevance of the research is reached if the result is reflecting the research questions asked. In this study the purpose is to;

“…investigating the perceived training and development needs for small firms. This to understand and overcome the differences in the perception of small firms’ needs between training vendors and small firms.”

From our study the relevance can be judged on the fact that our conclusion is based on the dual perspective analysis that has been conducted and that a conclusion can be drawn in order to fulfil the purpose. Furthermore, the data collected from the interviews and written material has enabled us to discuss the research questions generated from the problem. 2.5.2 Function

The function aspect of the data quality regards the relationship between data and theory. This means that there has to be a clear connection between the data and the theory used. With the use of theory the reader should be able to gain a deeper understanding of the em-pirical data. (Hartman, 2001)

To improve the functionality of our research the theoretical framework was developed as a continuous process during the collection process of the empirical data. This was done in order to ensure that only relevant theory was presented as well as to gain a deeper under-standing of the interpretation of the empirical data. Therefore, during the process new theoretical material was introduced, restructured and deleted.

2.5.3 Modifiability

According to Hartman (2001) the theory must be adoptable to the reality. In this case this means that maybe not all factors of a theory are relevant to the case or that some of them must be adjustable to fit with the data collected (Hartman, 2001).

Regarding the modifiability aspect of our research it can be seen in for example the use of the Grounded theory as a research method. The theory has not been fully implemented but rather used as an inspiration suitable for this research. In regards of the theoretical frame-work, the theories have been presented in short descriptive summaries where only relevant parts are included. Where the parts presented are valuable for the analysis of the empirical data. Hence, the theories have been modified to suit the research and therefore no exten-sive background history of the theories are presented.

3

Theoretical Framework

The purpose of this chapter is to give a presentation of the theoretical framework underlying this research. The concept of knowledge is presented together with an extensive framework of how knowledge can be ac-quired and attained for a small firm.

3.1 Knowledge

There are probably as many definition of knowledge as there are researchers that has tried to define it. Knowledge is a human and highly personal asset that represents the pooled ex-pertise and efforts of networks and alliances. 99 per cent of the work done by people is knowledge based (Wah, 1999b cited in Smith, 2007).

3.1.1 Knowledge to Create Competitive Advantage

For knowledge to be useful for the organization it has to increase or maintain the organiza-tion’s competitive advantage. To gain a sustainable competitive advantage, Barney (1991) argues that the knowledge acquired has to have four attributes: be valuable, be rare, be imper-fectly imitable and have no substitutes (cited in Probst, Buchel & Raub, 1998).

Valuable knowledge- is used to exploit opportunities and reacts to threats to become more ef-ficient or effective (Probst et al., 1998).

Rare knowledge- is used to differentiate the company from the rest. The knowledge is based on a unique mix of knowledge from both single individuals as well as existing organization-al knowledge. (Probst et organization-al., 1998)

Imperfectly imitable knowledge- is knowledge that cannot be copied to its full extension by competitors since the origin of the knowledge is unknown. This knowledge is developed from previous knowledge; it is ambiguous and socially complex. (Probst et al., 1998)

No substitution of knowledge- is gained when the knowledge cannot be replaced by other knowledge (Probst et al., 1998).

3.1.2 Tacit Knowledge and Explicit Knowledge

One dimension of the knowledge creation process is to make the distinction between two types of knowledge: tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge (Nonaka, 1994). The two types of knowledge differ in ability to transfer between individuals (Chirico, 2008). Explicit know-ledge can be defined as pure knowknow-ledge and is easily transferred, while tacit knowknow-ledge is the actual skill, the know-how, which is more difficult to transfer (Chirico, 2008: Pate, Mar-tin, Beaumont & McGoldrick, 2000). One should, however, be aware that comparing tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge is a way to think of knowledge rather than to focus on its differences (Smith, 2007).

It was the philosopher Polanyi who classified the human knowledge into two categories. He described tacit knowledge as “we know more than we can tell”. It is also the things we do without thinking about it, where one example is riding a bike (Smith, 2007). Tacit know-ledge is a personal quality which is difficult to communicate and it is founded in actions, commitment and involvement (Nonaka, 1994).

Explicit knowledge refers to the knowledge that is passed on in formal and systematic lan-guage (Nonaka, 1994). Explicit knowledge is technical and does usually require a level of

academic knowledge or understanding that is gained through formal education or struc-tured study (Smith, 2007). It is knowledge which can described in formal language, like manuals, mathematic expressions, copyright and patents (Smith, 2007).

The importance of tacit knowledge or explicit knowledge is different depending on the cul-ture. According to Nonaka, Umemoto, and Sasaki (1998) Japanese culture focuses on the importance of tacit knowledge while western cultures has a larger emphasis on explicit knowledge. However, Nonaka et al. (1998) argues that the two types of knowledge are mu-tually complementary and therefore it is important to find a balance between the two. It has been explained like there is a tension between process and practice. Process is represented by the explicit knowledge, which means the way knowledge is organized while practice is represented by tacit knowledge, the way work is actually done. If companies deal successfully with this tension they use multiple types of tacit and explicit knowledge, and therefore gain competitive advantage (Smith, 2007).

When the two types of knowledge are handled successfully, tacit knowledge is used to fos-ter innovation and creation. While, explicit knowledge is used to organize the work tasks and predict the work environment. (Brown & Dugid, 2000 cited in Smith, 2007)

3.2 Knowledge Management

Knowledge management is a formal and directed process used to determine what know-ledge a company has and hence could benefit others in the company and then also find ways to make it available for others (Liss, 1999 cited in Smith, 2007). Advocators of know-ledge management have promoted it to be an essential corner stone for companies to de-velop sustainable competitive advantage (Wong & Aspinwall, 2004). Know-ledge management includes the planned and systematic handling of knowKnow-ledge and the de-termined use of knowledge in an organization (Mandl & Winkler, 2007). However, know-ledge management must address these factors simultaneously: individual, organiza-tion, and technology in order to be recognized as a long-term strategy (Mandl & Winkler, 2007).

Knowledge management is organizations’ strategic efforts that are made in order to achieve a competitive advantage. This is done by identifying and making use of the employees’ and customers’ intellectual asset. Supporters of knowledge management believe that capturing, storing, and distributing knowledge is a way to help employees work smarter, reduce dupli-cation, and therefore produce more innovative products and services that meet the cus-tomers’ needs as well as to create good value. (Netzley & Kirkwood, 2006)

3.3 Training and Development Opportunities

Training has been argued to be critical for every job (Tyler, 2005 cited in Thassanabanjong et al., 2009). Training is defined as a learning experience that is creating a relatively perma-nent change in an individual and improves their ability to perform on the job (Treven, 2003 & Stone, 2006 cited in Thassanabanjong et al., 2009). In addition, Kitching and Blackburn (2002 p.5 ) says in their study that training is; “to include any activities at all through which manag-ers and workmanag-ers improve their work-related skills and knowledge. These activities may occur on- or off-the-job. They may occur in short bursts or be over a longer period of time. They may be linked to a qualification or not.”

It is noticeable that smaller firms undertake less or are even reluctant to training initiatives regardless of the incentives offered (Maton, 1999 cited in Patton et al., 2000). Kithching

and Blackburn (2002) agrees with this, stating that most studies report that small businesses provide less formal training than larger organizations. Reasons for this are that it exists ob-stacles to training in smaller firms such as the lack of finance and or time or the ignorance of the benefits gainable from it (Westhead & Storey, 1997 cited in Patton et al., 2000). Another reason to why firms tend not to attend training is, according to Matlay (1999, cited in Blackburn & Athayde, 2000) due to the problem of identifying training suitable to their needs. On the other hand, when small firms decide to attend training, the decisions are, ac-cording to Blackburn and Athayde (2000), responsive to immediate and identified needs. There has, however, been a focus on training regarding technical knowledge, skills and the capabilities necessary to complete the work (Treven, 2003 & Stone, 2006 cited in Thassa-nabanjong, 2009). Evidence shows that better trained members will perform more effec-tively and efficiently, they will be more motivated and valuable, take greater responsibility as well as make a greater contribution to performance (Spitzer, 1999).

“Training can influence performance, but organizational performance can also influ-ence training.”

- de Kok, 2002, p. 275

With this, de Kok (2002) argues that there is a positive relationship between investments in training and performance. De Kok (2002) sees that a company that is utilizing training will improve its performance, on the other hand, if a company is performing well it will see the advantage of continuous development to sustain their market position. Furthermore, a firm that are experiencing an economic downturn are more likely to invest in training since op-portunity cost of training decreases when time is not as limited (de Kok, 2002).

Training and development within firms can be divided into formal training and informal train-ing opportunities (Thassanabanjong et al., 2009). Traintrain-ing within small businesses is often described as informal, on-the-job and related to short term business objectives ( Johnson, 2002).This goes in line with the study by Blackburn and Athayde (2000) who argues that informal on-the-job training if preferred over formal training. According to Blackburn and Athayde’s study (2000) less than 7% had obtained formal training during their research period. 3.3.1 Formal Training

Formal training is the less common form of training attended to by small firms (Blackburn & Athayde, 2000). The primary reason why firms do not attend external training is, accord-ing to Blackburn and Athayde (2000), since small firms’ managers perceive the trainaccord-ing as inconvenient and unnecessary.

One type of formal training is off-the-job training, which is more structured. Off-the-job train-ing is often the traintrain-ing that is required by those who need specialized skills and qualifica-tions (Green, Ashton & Felstead, 2001). Off-the-job training has the advantage that the employees are not distracted by work and can therefore focus on the training (Green et al., 2001). Other types of formal trainings are: distance learning, individual guidance and workshops (Johnson & Loader, 2003).

Distance learning is a flexible learning situation without preset dates and location, where the student takes responsibility of their own learning. According to Kotey and Anderson (2006), students attending distance-learning courses learn to the same level as in-class stu-dents. Individual guided training is when student and teacher meet one-on-one; where top-ic, place and time devoted to training is determined by the course attendee (Johnson &

Loader, 2003).Workshops are single occasion meetings with a number of participants where a certain topic is decided in advance and discussed during for example a half day seminar (Johnson & Loader, 2003).

3.3.2 Informal Training- most preferable by small firms

Informal training is often preferred by the small firms. This is firstly, because this type of training is less costly than formal training. Secondly, informal training can easily be in-cluded in the daily work of a small firm. Finally, it is focused on the specific needs of the employees. In addition, another advantage is that the employees learn in the context in which their skills are later utilized. (Hill and Stewart 2000).

Types of informal training are: learning by doing, and On-the-Job (OTJ) Training. Considering the training to be in a hierarchy of structure; learning by doing is the most unstructured and informal training. Followed by the OTJ training which is relatively unstructured and means that the employees learn at the workplace. OTJ training is done by one-to-one instructions as well as it involves a description of the procedure together with a visual demonstration by the trainer. This training technique provides valuable help for the employees and can be de-fined as informal, unplanned training that is provided by supervisors. (Harris, 1997; Treven, 2003 cited in Thassanabanjong, 2009)

3.3.3 Networking- an additional method for development

“No matter where you work--- Networking is a pivotal professional competency. It’s the BEST way to get the job done, make things work, improve the processes, and advance your career.”

-Baber & Waymon, 2007, p. 161

A network is a social tie between two or more individuals. According to Aldrich and Zim-mer, (1986) the relationship between the individuals can have multiple purposes such as; passing of information, the exchange of goods and services and/or to change experiences. (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986)

According to O’Donnell, (2004) a firm’s network can be evaluated in three dimensions; level of networking, networking reactivity and the strength of network ties. The level of networking refers to how a manager interacts with his/her network. The level of networking is measured on a scale from limited networking to extended networking. Limited networking refers to a manager who seldom and irregularly interacts with his network ties. Extended networking on the other hand means a manager who has more frequent and long-term relationships with his network ties. In regards of networking proactively, O’Donnell (2004) refers to how the firm works with extending its networks. Extending networks can either be done in a proactive or reactive manner. Curran et al. (1993 cited in O’Donnell 2004) argues that small firms tend to be more reactive than proactive in their networking. Al-drich and Zimmer, (1986) on the other hand, see that networking is both a deliberate and subconscious process. Hence, some contacts are planned for a certain purpose, while oth-ers are accidental interactions with random people, but proven useful in a later situation (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986).

Regarding the dimension strength of network tie, the network connections are divided into strong links and weak links. What defines a strong tie or weak tie differs among research-ers. The strong links and weak links are, according to Granovetter (1973 cited in O’Donnell 2004), divided dependent on time, the emotional intensity and the intimacy of

the relationship. Others ads frequency of use and level of trust as variables to determine strong ties from weak ties (Johannisson, 1986 cited in O’Donnell, 2004).

Apart from O’Donnell’s (2004) theory regarding the different dimensions of networks, Bir-ley (1985) also distinguishes between different types of networks; informal and formal. Formal Networks

According to Birley (1985) formal networks consist of relationships between the firm and banks, accountants, chamber of commerce, small firm administrations and lawyers among many. The use of formal networks is according to Birley (1985) more common when the firm is started and for example additional financing is needed.

Informal Networks

Informal networks consist of ties between the owner of the firm and his/her family, friends and business contacts (Birley 1985).

Informal networks are according to Birley (1985) the prime source when searching for in-formation concerning different elements of the business in the start up phase as well as searching for locations and new employees later on. Using informal networks as a primary resource over formal networks is, according to Dubini and Aldrich, (1991), a good source for small firms since the knowledge will be acquired both faster and at a lower cost. Cold Contacts

In addition to the importance of using networks to gain new knowledge and to access in-formation that is lacking in a firm, Birley (1985) also highlights the use of cold contacts. Cold contacts are referring to published resources such as newspapers and magazines. Both to gain information as well as to publish an advertisement regarding a need required in the company. (Birley, 1985)

According to Birley (1985) cold contacts are ranked as the second most common used me-thod to collect resources, where informal networks are the primary resource.

Networking for Small Firms

According to Valkokari and Helander (2007) the small firms’ network is an option to com-pensate for the knowledge lacking within the firm. The benefit small firms can gain from their network contacts are access to knowledge and other capabilities that their network holds (Valkokari & Helander, 2007). Baber and Waymon (2007) also argue that networking is a useful method to expand your knowledge base. In order to expand its knowledge base, a firm should identify what resources they are in need of and create a network with people that have these areas of expertise (Baber and Waymon, 2007). This expansion of know-ledge can, according to Birley (1985), be done through the use of multiple networks, both informal network and formal networks simultaneously. Most common to gain the lacking knowledge is to use more than one of the networks as a resource (Birley, 1985).

For a network to be useful for the firm, the network must be willing and able to share its knowledge among the different network members (Baber & Waymon, 2007: Valkokari & Helander, 2007). Sharing knowledge within the network creates exposure to new ideas and future development opportunities (Baber & Waymon, 2007: Valkokari & Helander, 2007). According to Coviello & Hugh (1995) the development of small firms are highly dependent on the relationships with others. Håkansson (1989), Håkansson and Waluszewski, (2002), Gadde et al. (2003) and Hoang and Antoncic (2003) further emphasize that the business

relationships that a firms has within its business network is a critical factor to a firm’s suc-cess of failure (cited in von Raesfeld & Roos, 2008).

3.4 Selection Process of Knowledge

Supplier selection process is a multi-criteria process that contains qualitative as well as quantitative aspects (Ghodsypour & Brien, 1998). In order to select the best supplier in the leading industry one has to make a tradeoff between tangible and intangible factors, some of which may conflict. Gonzal´lez and Quesada (2004) have in their study found the tra-deoffs to be quality, cost and delivery performance measures in the supplier selection process. In addition, Verma and Pullman (1998) have found that customers select suppliers based on the relative importance of different attributes such as quality, price, flexibility, and delivery per-formance.

3.4.1 Proactive

Crant (2000) defines proactive behavior as taking initiative in improving current circums-tances or creating new opportunities. This means that one is not passively adapting to present conditions, but rather constantly challenging the status quo. Employees can engage in proactive activities as part of their in-role behavior. Studies suggest that proactive perso-nality is an important element of employee, team, and firm effectiveness. (Crant, 2000) 3.4.2 Reactive

Reactive behavior in a person is, according to Larson, Bussom and Vicars, (1986), defined as a person who is passive and who’s goals are not driven by their desire but rather as a re-sult of a requirement.

According to Fairman and Yapp (2005), small firms more commonly use the reactive ap-proach to search for information. With this Fairman and Yapp (2005) means that small firms do not tend to search information and search for training actively unless the informa-tion or training is required due to for example changes in regulainforma-tions.

3.4.3 Trust

Trust is an important variable to client satisfaction (Connor & Prahalad, 1996). Wilson and Jantrainia (1993, cited in Huemer, Krogh and Roos, 1998) argue that trust is a key to suc-cessful relationships. Trust has been examined by the use of different theoretical perspec-tives and it is defined as the willingness to make oneself vulnerable for another party (McAllister, 1995). Johnson and Swap (1982, p. 1306) define this issue as the; “willingness to take risks may be one of the few characteristics common to all trust situations.”

The regular exchange of information between parties is particularly important since the more the parties interact with each other, the more they will understand each other’s val-ues, norms, and behaviors (McAllister, 1995). This will lead to a better understanding of each other and hence increase the ability to create trusting relationships (McAllister, 1995). When trust is present the vendor is more likely to better serve the client needs (Connor & Prahalad, 1996). This means that the firm may be less likely to fully utilize the vendor’s ex-pertise when there is limited trust, which then affects the quality of the services and in the end the client satisfaction (Connor & Prahalad, 1996).

According to Mayer, Davis and Shoorman (1995) there are three factors for trustworthi-ness: ability, benevolence, and integrity. Although these factors are related they can differ inde-pendently of each other.

Ability is the combination of skills, competencies, and characteristics which enable one par-ty to influence the other parpar-ty within a specific area. Benevolence is to which extent the trustee is believed to want to do what is good for the trustor without a selfish profit inten-tion. Integrity entails the trustor’s perception that the trustee stays to a preset of principles that the trustor finds acceptable. (Mayer et al., 1995)

If ability, benevolence, and integrity all are perceived to be high, the trustee would be con-sidered trustworthy. Trustworthiness should, however, be thought of as a continuum rather than the trustee being either trustworthy or not trustworthy. (Mayer et al., 1995)

3.5 Absorptive Capability

According to Cohen and Levinthal (1990) knowledge creation in itself is not the critical factor for a company to survive in the competitive world, the company needs to know how to use and exploit the new knowledge. Absorptive capability is a firm’s ability to recognize the value of new external information, assimilate the information and use it in their organiza-tion (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990: Lane & Lubatkin, 1998: Lane, Salk & Lyles, 2001).

The ability to absorb new knowledge, according to researchers, depends on the firm’s prior knowledge within that field (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990: Lane & Lubatkin, 1998: Lane, Salk & Lyles, 2001).

The absorptive capacity a firm possesses comes from the individuals within the firm; the firm itself cannot possess absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Therefore, the communication between individuals and the knowledge sharing across and within sections becomes important to enhance the absorptive capability (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). The level of absorptive capacity can be affected through direct investments and indirect invest-ments. The former can take the form of sending staff to external training in new areas where existing knowledge is low (Ordonez de Pablos, 2002). The latter can be done through R&D investments and investments in the manufacturing operations since new knowledge is created and identified in these processes (Ordonez de Pablos, 2002).

Absorptive capacity is an intangible asset and benefits are indirect. Therefore, it is hard to establish what the optimal level of absorptive capacity is for a firm (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). However, what can be seen is that if a company does not invest in absorptive capac-ity, the company will have problems to identify new opportunities on the market, and when the market races ahead of them, it is hard to catch up (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). In re-gards of the level of absorptive capacity a firm possesses, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) iden-tifies that firms with a high level tends to be more proactive and able to exploit new oppor-tunities. While firms with lower levels of absorptive capacity are more reactive and there-fore only find new alternatives when failure is realized in their present work routine.

4

Empirical Findings

In this section the empirical data collected is presented. Since our research is investigative from a dual pers-pective the empirical material will be divided into two sections. The first section will present the empirical finding from the training vendors’ perspective followed by the findings from the managers of the small firms.

4.1 Training Vendors Perspective

There are multiple actors on the training vendor’s side of this perspective. As presented earlier, the vendors can be divided into two sub groups: public training vendors and private training vendors. For this research four interviews have been performed with training ven-dors providing training and development for small firms. Three of the venven-dors are public and one is privately owned. In the presentation the training vendors will be referred to as; Training vendor A, B, C and D.

4.1.1 Management of Small Firms

Two of the training vendors highlight the fact that most business owners are good at what they are doing (B, C). They know by instinct how to run a firm and as long as everything is fine, this instinct is sufficient to run a firm (C). However, when something happens, like a recession, the need for knowledge and training becomes apparent to the firm’s owner. Therefore, as highlighted by Training vendor C, for firms to take on external help the firms themselves have to realize the need. When the need is realized, the timing of training and development opportunities offered from the vendors within these areas are crucial for the small businesses to gain the knowledge (C). Training vendor A, identifies other reasons to why new knowledge is acquired apart from the forced needs to acquire new knowledge, one reason is the constant desire that some clients have to learn new things and one other is to refresh their memory.

There are many opportunities for companies to get help with knowledge development. Ac-cording to training vendor B and C reasons why small firms do not take on these oppor-tunities are time, money and non-realization of the needs. Training Vendor B highlights the importance for the small firms to see the direct value of the knowledge gained.

“Often the time is not enough; either you have so much to do that you do not have time to do anything, or you have little to do, but the money is not enough”

-Training vendor C

Training vendor D also agrees with C in regard of the difficulty to incentivize training when times are good, while in downturns on the other hand the funding is the obstacle. Another possible factor for why firms do not seek external help, highlighted by Train-ing vendor C, is due to pride. With this TrainTrain-ing vendor C means, that a firm that has iden-tified a problem, might not be comfortable sharing their problems with an external partner. The benefit of seeking external help and training however, is argued by Training vendor C to be a success factor.

“A trait you can see in successful businesses is that they seek external help.” -Training vendor C

For a small firm to attend a course or other training opportunities, the offer for the training opportunity has to be timed with the identification of the need;

“Do you knock on the door two hours too early or two hours too late, something else might be in focus”

-Training vendor C

4.1.2 Identified Training and Development Needs for Small Firms

The training vendors all identify different specific areas where training and development needs are present. The differences are dependent on the training vendors’ specific areas of core competence. Training vendor A highlights the importance of training needs within areas of general accounting and how to make a company more efficient. These areas are in line with the recognized needs identified by Training vendor C who identifies calculation, accounting and profit analysis. In addition, Training vendor C also stresses the need for training and development in areas of sales, marketing, market strategy development and in-ternationalization as being important. Training vendor C believes that the need for training is the same across industry sectors. Training vendor B has its core competences in the management of family businesses and therefore they encourage training and development in areas regarding succession and how to govern a business. Training vendor D, who is helping people to actualize their business ideas, argues for the need for firms to develop a useful business plan. This means that the firms need to have sufficient knowledge in areas included in the business plan, such as market analysis, financing, budgeting and recruit-ment.

The reasons why the training vendors offer training and development opportunities to small business are different dependent on the vendor. Training vendor C claims to offer opportunities to ensure that all areas where small firms recognize a training and develop-ment need are covered on the market. For them, it does not matter who offers the devel-opment opportunity as long as the training needed is available. Training vendor D agrees with Training vendor C regarding being a non-competitive actor on the market. Their pur-pose is to offer knowledge and advice regarding new ideas in order to develop them into companies. This can be done with the use of their in-house knowledge as well as through external sources of knowledge in their network. Training vendor B’s purpose with their courses is not to radically increase the small firm’s turnover but rather to increase the communication within the business. Training vendor A is offering courses to their clients in order for the clients to gain a deeper knowledge and understanding of the accounting tools already present in their firm. This is done to enhance the clients understanding of what the numbers mean and how the numbers basically works.

4.1.3 Types of Training and Development Opportunities Offered

Training opportunities offered by training vendors differ both in level of difficulty as well as structure such as level of customization, extent and layout of the training.

Training vendor A offers both standardized courses as well as company specific courses that are more customized. The standardized courses are held in a conference setting with participants from multiple small companies. This gives an opportunity to share experiences with each other, as well as an opportunity to build relationships. The company specific courses on the other hand are taking place in the client’s office. According to Training vendor A, one reason to pick company specific courses is to ensure that all co-workers gain the same knowledge at the same time. By using customized alternatives, the relevance of

the knowledge gained for the firm can be assured. Training vendor A notes that there is a trend for bigger organizations to use more of their customized trainings. The important outcome of the training and development sessions is, according to Training vendor A, that the course provides a hands-on tool that the client can use in their everyday business. Therefore, the courses are practically based, with a foundation in the reality.

“Those that are performing the courses are active consultants and are meeting clients everyday and therefore know what they find difficult and what should be the content in a course.”

- Training vendor A

For Training vendor B, most courses are customized. To ensure that Training vendor B is adding value to their clients they conduct extensive background research on the clients to map the client’s needs and what Training vendor B can offer them. The customized train-ing meettrain-ings are held at the client’s office, where all people involved meet for a number of sessions. The aim of the training sessions is to get everybody involved to the same level. Training vendor C offers mostly standardized courses, where six or more companies attend the training opportunity at the same time. The courses can be; single occasion meetings, seminars or longer courses. For Training vendor C customized training opportunities are performed more in the setting of counseling sessions, which is more of a dialog between the client and the training vendor.

Training vendor D’s primary knowledge creation tool for their clients is counseling ses-sions with a customized content. Being a client in one of their concepts, means a pre-determined amount of counseling hours per week. In the start-up phase certain informa-tion is standardized and for this, Training vendor D holds seminars. To provide addiinforma-tional knowledge outside of the core competence, Training vendor D uses their network to ac-cumulate the knowledge needed in order to help the new firms.

4.1.4 Identification and Development of New Training Opportunities During the process of developing courses and identifying areas where training is needed, the training vendors takes into consideration different factors such as the state of the economy (C), clients demands (A, C), previous experience (D) and “hot topics” on the market (A, C).

According to Training vendor C, one example of change due to the current economic situ-ation, is the increase in demand of courses relating start-up and acquisitions, this since many people recently have been laid-off. A hot topic at the moment is the issue of social media and how it can be used to create competitive advantage for the small firm (C). Training vendor A, who is in contact with their clients primarily to provide economic con-sultation, uses their expertise and presence in the market to identify the needs for training opportunities. By helping their clients with other economic issues they can see where their clients are experiencing difficulties and then develop a course or training opportunity to fa-cilitate these issues in the future. Training vendor D also uses their experience within the field of business to identify needs.

Other external factors that affect the development of training opportunities are due to con-stantly changing legal framework (A & C) as well as grants from government (B).