NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 1

Science competencies

for the future

Proceedings of the 12

thNordic Research Symposium on Science Education

June 7

th–9

th2017 Trondheim, Norway

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 2

Science competencies for the future

Proceedings of the 12th Nordic Research Symposium on Science Education

June 7th–9th 2017 Trondheim, Norway

Editor: Auður Pálsdóttir

April 2018

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 3

Foreword

The 12th Nordic Research Symposium on Science Education was held in Trondheim, Norway in June 7–9 2017 at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The conference theme was Science competencies for the future.

The story of the NFSUN conferences goes back to 1984. The Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, host the conference alternately every three years. In each conference, symposiums link research and development and function as a meeting point and a platform for establishing networks within the science education research community. Further information on the NFSUN conferences are at nfsun.org

The 2017 conference consisted of two parts. First, a half day pre-conference on 6 June with focus on how to do research in science education. The pre-conference was intended for PhD-students and new

researchers in the field, though experienced researchers were also welcome. Then, the main conference was held the following three days.

In the conference synopsis book all accepted abstracts are presented, including total of 58 papers, 7 posters and 5 workshops that were held. The synopsis book is available at

https://www.ntnu.edu/documents/1268744133/0/Synopsis_Book.pdf/17462d74-3cab-487e-a47e-c12b09c9c6e1

This publication, The NFSUN 2017 Proceedings, is published online at the conference website. Call for contributions to the Proceedings ended in August 2017, and eighteen papers were accepted after a double-blind review process. Authors of eight of them were invited to extend their papers for publication in the Journal of Nordic Studies in Science Education, NorDiNa. Therefore, these proceedings consist of ten papers. The reviewers consisted of colleagues in the Nordic Countries, the United Kingdom and Canada. The proceedings are presented in English or in a Scandinavian language. As can be seen on following pages, the paper topics relate to sustainable development, science literacy, modern technology in education, teacher professional development, teacher professionalism and curriculum development. This wide range is of important value for further enhancing science education in the Nordic countries.

Auður Pálsdóttir, Editor Reykjavík, April 2018

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 4

Index

Page EDUCATIVE CURRICULUM MATERIALS AND CHEMISTRY: A MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN? ... 5 Tor Nilsson

VEJLEDNING I LÆNGERE-VARENDE FÆLLESFAGLIGE FORLÖB I NATURFAG – VÆRKTÖJER OG

ARTEFAKTBASERING ... 13 Lars Brian Krogh, Pernille Ulla Andersen, Harald Brandt, Keld Conradsen, Benny Lindblad Johansen, Michael Jes Vogt.

DANISH GEOGRAPHY TEACHERS ASSESSMENT OF OWN TEACHER PROFESSIONALISM ... 26 Søren Witzel Clausen

FINNISH MENTOR PHYSICS TEACHERS’ IDEAS OF A GOOD PHYSICS TEACHER... 35 Mervi A. Asikainen, Pekka E. Hirvonen

BUILDING SCIENCE TEACHER IDENTITY WITHIN AN INTEGRATED TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OSLO ... 42 Doris Jorde, Cathrine W. Tellefsen

CONTEMPORARY SCIENCE EDUCATION PRACTICE: AN INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE ... 51 Claus Bolte, Marlies Gauckler

FLIPPED LEARNING I FYSIK/KEMI I UDSKOLINGEN ... 64 Henrik Levinsen, Thomas D. Andersen, Kristian K. Foss, Nina T. Jensen, Peter Jespersen, Stine K. Nissen, Morten R. Philipps

DEVELOPMENT OF A CHEMISTRY CONCEPT INVENTORY FOR GENERAL CHEMISTRY STUDENTS AT

NORWEGIAN AND FINNISH UNIVERSITIES ... 73 Tiina Kiviniemi, Per-Odd Eggen, Jonas Persson, Bjørn Hafskjold, Elisabeth Jacobsen

«SJØUHYRET» - BESKRIVELSE OG EVALUERING AF ET TVERRFAGLIG UNDERVISNINGSOPPLEGG OM MARIN FORSØPLING I LYS AV UTDANNING FOR BÆREKRAFTIG UTVIKLING) ... 81 Wenche Sørmo, Karin Stoll, Mette Gårdvik

BRUK AF ERFARINGER OG TVERRFAGLIGHET I NATURFAGUNDERVISNINGEN PÅ SMÅSKOLETRINNET ... 90 Charlotte Aksland, Inger Kristine Jensen, Aase Marit T. Sørum Ramton

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 5

EDUCATIVE CURRICULUM MATERIALS

AND CHEMISTRY:

A MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN?

Tor Nilsson

Mälardalen University, Eskilstuna, Sweden Correspondence: tor.nilsson@mdh.se

Abstract A pilot study on the use of Educative Curriculum Materials (ECM), as defined byDavis and Krajcik (2005), in chemistry education research is reported. The aim is to identify how Davis and Krajcik’s work has influenced chemistry education research and to what extent teacher guides in chemistry have been analysed. The review shows that of 248 articles concerning curriculum material and/or development, 22 concerned chemistry education research; however, when using only Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) definition, the number dropped to 16. Not one of the articles concerned teacher guides. There were 28 categorised instances referring to Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) definition: 14 regarding existing knowledge bases, 7 using their actual definition of ECM, 3 arguing for own choices and 4 linking own results and ECM. In addition, a non-existing data analytical category, ‘analytical framework’, is proposed in order to show that no study included Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) analytical framework. This review is limited to articles referencing Davis and Krajcik (2005), which necessarily limits the findings. However, an analytical matrix with respect to ECM is presented and the study shows a gap in chemistry education research. Suggestions for how to improve and/or expand the review are made.

Keywords Chemistry education research, Educative curriculum materials, Teacher guide, review

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 6

1. Introduction and aim

Bridging the gap between research and practice is important, and researchers should approach doing so in ways that are accessible to teachers (de Jong, 2000). Constructing teacher guides offers one such

opportunity (Davis & Krajcik, 2005). The interest in teacher guides stems from the personal experience of supervising a PhD student in mathematics education research (Hoelgaard, 2015). Her work concerned Educative Curriculum Materials (ECM, see Davis & Krajcik, 2005) and the potential for teacher guides to act as resources for teachers to learn about their own teaching. In a general sense, ECM can be seen as in-service teacher training or developmental work, and all available resources and areas that teachers need to learn about fall within the definition of ECM (Davis & Krajcik, 2005). Davis and Krajcik argue that as teacher learning is situated in a practice, it does not only include the teacher’s own learning about content, teaching and learning. It also includes applying that knowledge in the classroom as the teaching is under way as well as being able to participate in a teaching discourse and becoming encultured and engaged. They present nine design heuristics for educative science curriculum materials, for instance “Design Heuristic 3 – Supporting Teachers in Anticipating, Understanding, and Dealing with Students’ Ideas About Science” (ibid. p.11). While supervising Hoelgaard, I became curious about what has been done within my field, chemistry, with respect to ECM, teacher guides and how they support teachers in learning about their own teaching.

The overall aims of the research project are; first to find out whether it is it worth to design a research project that concerns the analysis of teachers guides in chemistry, and second, to identify how a more extensive review can be conducted to firmly argue the relation between ECM, teacher guides and how they support chemistry teachers to learn about their own teaching. In order to review literature on ECM,

chemistry and teacher guides, a directed approach was taken. In this first step of the research project, articles that reference Davis and Krajcik (2005) are reviewed. The aim of this pilot study is to identify how Davis and Krajcik’s work has influenced chemistry education research and to what extent teacher guides in chemistry have been analysed. The research question is: To what extent and in what ways has ECM, as defined by Davis and Krajcik, acted as a foundation in chemistry education research?

2. Methods

The search limitations were peer-reviewed research articles written in English 2005–2016. The following databases were searched: Discovery (151125), Scopus (160127, 160222), Web of Science (160127, 160222) and Eric ProQuest (160127, 160222). First, any article using Davis and Krajcik (2005) as a reference was identified. Then, various search terms were used (e.g., ‘educative curriculum’ AND chemistry; ‘Curriculum materials’ OR ‘Instructional materials’ AND chem* (SU); ‘Curriculum materials’ AND chem* AND teach*; ‘teacher* guide* (SU)’). All search results were compiled in one EndNote library, and

duplicates were removed, resulting in 296 articles. Despite specified search terms and inclusion criteria, a number of hits were retrospectively excluded (e.g., conference proceedings and papers not written in English), resulting in a final list of 248 articles. Although included in most searches, how ‘chemistry’ or ‘chemical’ had been used within each article had to be established. In two steps the sample was reduced to 31 articles, of which 19 referred to Davis and Krajcik (2005) and later on 22 articles, of which 16 referred to Davis and Krajcik (2005) (see Table 1). In this final process, articles were excluded if science

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 7 subjects were listed in the body of the text (e.g. biology, chemistry and physics) but the article otherwise concerned biology.

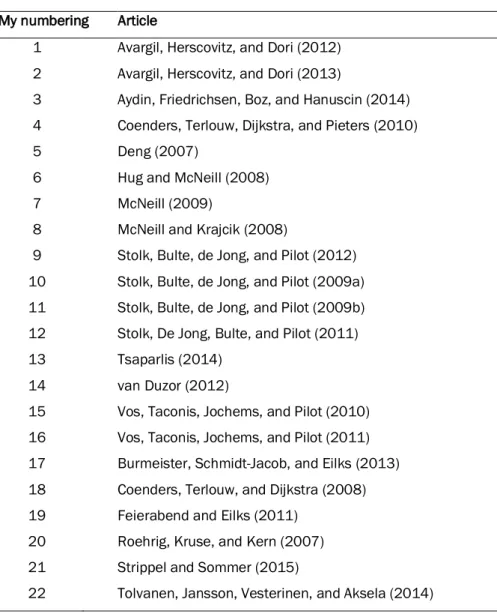

Table 1. All included articles, number 1‒16 refer to Davis and Krajcik (2005) My numbering Article

1 Avargil, Herscovitz, and Dori (2012) 2 Avargil, Herscovitz, and Dori (2013)

3 Aydin, Friedrichsen, Boz, and Hanuscin (2014) 4 Coenders, Terlouw, Dijkstra, and Pieters (2010)

5 Deng (2007)

6 Hug and McNeill (2008)

7 McNeill (2009)

8 McNeill and Krajcik (2008)

9 Stolk, Bulte, de Jong, and Pilot (2012) 10 Stolk, Bulte, de Jong, and Pilot (2009a) 11 Stolk, Bulte, de Jong, and Pilot (2009b) 12 Stolk, De Jong, Bulte, and Pilot (2011) 13 Tsaparlis (2014)

14 van Duzor (2012)

15 Vos, Taconis, Jochems, and Pilot (2010) 16 Vos, Taconis, Jochems, and Pilot (2011) 17 Burmeister, Schmidt-Jacob, and Eilks (2013) 18 Coenders, Terlouw, and Dijkstra (2008) 19 Feierabend and Eilks (2011)

20 Roehrig, Kruse, and Kern (2007) 21 Strippel and Sommer (2015)

22 Tolvanen, Jansson, Vesterinen, and Aksela (2014)

Next, the articles were analysed using Evans’s (2002) description of a systematic review, including a descriptive part (e.g. design, educational level) and an interpretive part (e.g. included studies and why, differences and similarities). What is mainly reported herein is only a small part of the analysis, addressing only how Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) study has been used by researchers in chemistry education research. Hence, table 2 below only includes results referring to articles 1-16. However, all 22 articles have been analysed with respect to how teacher guides are referred to in each article. A sample of the analysis is given next.

McNeill (2009) presented teachers’ use of an 8-week chemistry curriculum and the construction of scientific arguments through inquiry. The introduction contained the following reference to Davis and Krajcik (2005): ‘Curriculum materials are an important tool to help teachers engage their students in inquiry, particularly educative materials that are specifically designed to promote teacher learning’ (McNeill, 2009, p. 234). Taking into consideration the context of this quote, the labels assigned were ‘argumentative’

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 8 since McNeill (2009) clarifies the importance of ECM, and ‘providing definition of ECM’ since ECM is defined almost as Davis and Krajcik (2005) define it.

3. Results

Of the 248 articles concerning curriculum material and/or development, 22 addressed chemistry education research (8.9%) (Table 1). However, when only those articles that addressed Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work on ECM were included, the number dropped to 16 (6.5%). Table 2 below presents the analysis of how Davis and Krajcik (2005) acted as a foundation in these articles.

Table 2. How ECM Is Used in Articles Referring to Davis and Krajcik (2005). Each digit refers to a unique article number as presented in Table 1. A digit equals one category present in the text of that article, whereas an † indicates two categories present at the same time.

Where in the article

How ECM is used

Existing knowledge base Argument for own choices Definition Analytical framework Compar-ison to one’s own results ∑ Introduction 1, 3, 4, 5, 12 7†, 14 7† 8 Literature review 2, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 12 8 Methodology/ Theoretical frame 7 7, 8 3 Discussion 3†, 7 3†, 4, 11 5 Conclusion and implication 5, 6 3† 3† 4 ∑ 14 3 7 0 4 28

The 16 articles contained 25 references to Davis and Krajcik (2005), but because a single reference could be included in multiple categories, the categorical sum (Table 2) came to 28. Half of the references recognized Davis and Krajcik (2005) as part of an existing ECM knowledge base. However, their definition of ECM was addressed in only four articles: 3, 7, 8 and 12. As Table 2 shows, the researchers’ arguments for own choices were found in only two articles (7 and 14), and links between own research results and ECM were made in only three articles: 3, 4 and 11. To emphasize the outcomes of the data analysis, Table 2 includes the proposed category ‘analytical framework’.

The analysis also revealed that none of the articles analysed teacher guides with the same meaning as in the introduction of this paper.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 9

4. Discussion and conclusions

Considering the large amount developmental curriculum work taking place in chemistry education research, identifying only 16 articles referring Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) ideas of ECM is a bit surprising. However, there is more to the story, since curriculum development materials do not necessarily need to reference Davis and Krajcik (2005). In addition, because of the fuzzy definition of ECM, many articles that do not explicitly refer to Davis and Krajcik (2005) may still implicitly concern ECM according to Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) definition and, indeed, provide supporting materials for teachers. Hence, using other references may provide a clearer picture.

Since ECM, teacher guides and how these guides support teachers in learning about their own teaching were the reasons for conducting this pilot study, it is interesting to note that not a single article concerned the analysis of teacher guides in that sense. This study demonstrates that research on teaching guides as a support for teacher learning is currently lacking in the field of chemistry education. With respect to all above, it seems fruitful to analyse how teacher guides support chemistry teachers to learn about their own teaching.

Since teacher guides weren’t analysed Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) developed analytical framework was never a part of the research. Furthermore, only three articles used Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work as an argument for the researchers’ own choices. Instead, most of the references were generic and merely acknowledged Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work. In order to design a research project on ECM, teacher guides and how they support chemistry teacher learning about their own teaching, it is possible to use Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work in all the ways as described by the categories in Table 2. To conclude, there are limitations in both the extent and the ways ECM, as defined by Davis and Krajcik’s (2005), has acted as a foundation in chemistry education research.

This review had limitations. On the one hand, referring only to Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) definition of ECM makes the review biased and fails to provide the entire picture of ECM and chemistry education research. On the other hand, providing the entire picture of ECM and chemistry education was not the aim of the study and Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work is a cornerstone of ECM research. As stated above, the main question that framed the review is whether to design a research project that concerns the analysis of teachers’ guides in chemistry. With that in mind, this pilot study gives hints on how to proceed. In addition, one outcome of the data analysis is the analytical matrix. Therefore, to both validate the matrix and find patterns in ECM research, a larger study might include different subjects, a larger sample of articles and other researchers’ definitions of ECM.

To conclude, this review shows a gap in chemistry education research regarding ECM, teacher guides and how they support teachers to learn about their own teaching. Therefore, the suggestions for further research are:

1. In order to probe and validate the developed analytical matrix, a more extensive review of the literature related to the work on ECM as defined by Davis and Krajcik (2005) is needed. 2. In order to keep focus on the relation between ECM, teacher guides and how they support

chemistry teachers learning about their own teaching, it is possible to conduct a more extensive review of research on ECM with the aim of providing a fuller picture of the relationships.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 10 3. It would be helpful to design a project in which teacher guides in chemistry are analysed.

Even if the first point is interesting in a general sense, since research on teacher guides in all subjects will be included, the third point is the end-game. The extended review in the first point cannot be limited to chemistry and therefore the relation between ECM, teacher guides and how they support chemistry

teachers learning about their own teaching will be lost. Therefore, the second point becomes more relevant from a scientific point of view as it will yield arguments that provide a basis for the third point. Even if this limited review may act as an argument for why such a project is needed, the first step must be to perform a more extensive review on how teacher guides support chemistry teachers learning of their own teaching. By doing so, the relation to Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) work will be lost, but solid arguments will be found. Finally, a return to the statement about bridging the gap between research and teaching practice (de Jong, 2000), in which ECM may play an important role, is warranted. Based on this review and extensive reading of the articles, it is likely that local bridges between researchers and participants in individual studies have been created, but in a general sense, broader bridges in the field of Chemistry teaching have yet to be formed. So, the simple answer must be: ECM has not played a substantial role in chemistry teaching, at least not yet. Further research is needed to establish whether Davis and Krajcik’s (2005) framework or a different framework would be most helpful for supporting chemistry teachers in learning about their own teaching.

5. Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Swedish Association of Educational Writers.

6. References

Avargil, S., Herscovitz, O., & Dori, Y. J. (2012). Teaching thinking skills in context-based learning: Teachers' challenges and assessment knowledge. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 21(2), 207– 225. doi:10.1007/s10956-011-9302-7

Avargil, S., Herscovitz, O., & Dori, Y. J. (2013). Challenges in the transition to large-scale reform in chemical education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 10, 189–207. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2013.07.008

Aydin, S., Friedrichsen, P. M., Boz, Y., & Hanuscin, D. L. (2014). Examination of the topic-specific nature of pedagogical content knowledge in teaching electrochemical cells and nuclear reactions. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(4), 658–674. doi:10.1039/c4rp00105b

Burmeister, M., Schmidt-Jacob, S., & Eilks, I. (2013). German chemistry teachers' understanding of sustainability and education for sustainable development – An interview case study. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 14(2), 169–176. doi:10.1039/c2rp20137b

Coenders, F., Terlouw, C., & Dijkstra, S. (2008). Assessing teachers' beliefs to facilitate the transition to a new chemistry curriculum: What do the teachers want? Journal of Science Teacher Education, 19(4), 317–335. doi:10.1007/s10972-008-9096-5

Coenders, F., Terlouw, C., Dijkstra, S., & Pieters, J. (2010). The effects of the design and development of a chemistry curriculum reform on teachers' professional growth: A case study. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21(5), 535–557. doi:10.1007/s10972-010-9194-z

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 11 Davis, E. A., & Krajcik, J. S. (2005). Designing educative curriculum materials to promote teacher learning.

Educational Researcher, 34(3), 3–14.

de Jong, O. (2000). Crossing the borders: Chemical education research and teaching practice. University Chemistry Education, 4(1), 31–34.

Deng, Z. Y. (2007). Knowing the subject matter of a secondary-school science subject. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 39(5), 503–535. doi:10.1080/00220270701305362

Evans, D. (2002). Systematic reviews of interpretive research: Interpretive data synthesis of processed data. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20(2), 22–26.

Feierabend, T., & Eilks, I. (2011). Innovating science teaching by participatory action research - Reflections from an interdisciplinary project of curriculum innovation on teaching about climate change. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 1(1), 93–112.

Hoelgaard, L. (2015). Lärarhandledningen som resurs: En studie av svenska lärarhandledningar för matematikundervisning i grundskolans årskurs 1–3 [The teacher guide as a resource: A study of Swedish teacher guides for mathematics in primary school grade 1-3]. (Licentiate), Mälardalen University, Västerås.

Hug, B., & McNeill, K. L. (2008). Use of first-hand and second-hand data in science: Does data type influence classroom conversations? International Journal of Science Education, 30(13), 1725– 1751. doi:10.1080/09500690701506945

McNeill, K. L. (2009). Teachers' use of curriculum to support students in writing scientific arguments to explain phenomena. Science Education, 93(2), 233–268. doi:10.1002/sce.20294

McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2008). Scientific explanations: Characterizing and evaluating the effects of teachers' instructional practices on student learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(1), 53–78. doi:10.1002/tea.20201

Roehrig, G. H., Kruse, R. A., & Kern, A. (2007). Teacher and school characteristics and their influence on curriculum implementation. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(7), 883–907.

doi:10.1002/tea.20180

Stolk, M. J., Bulte, A., de Jong, O., & Pilot, A. (2012). Evaluating a professional development framework to empower chemistry teachers to design context-based education. International Journal of Science Education, 34(10), 1487–1508. doi:10.1080/09500693.2012.667580

Stolk, M. J., Bulte, A. M. W., de Jong, O., & Pilot, A. (2009a). Strategies for a professional development programme: empowering teachers for context-based chemistry education. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 10(2), 154–163. doi:10.1039/b908252m

Stolk, M. J., Bulte, A. M. W., de Jong, O., & Pilot, A. (2009b). Towards a framework for a professional development programme: empowering teachers for context-based chemistry education. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 10(2), 164–175. doi:10.1039/b908255g

Stolk, M. J., De Jong, O., Bulte, A. M. W., & Pilot, A. (2011). Exploring a Framework for Professional Development in Curriculum Innovation: Empowering Teachers for Designing Context-Based

Chemistry Education. Research in Science Education, 41(3), 369–388. doi:10.1007/s11165-010-9170-9

Strippel, C. G., & Sommer, K. (2015). Teaching Nature of Scientific Inquiry in Chemistry: How do German chemistry teachers use labwork to teach NOSI? International Journal of Science Education, 37(18), 2965–2986. doi:10.1080/09500693.2015.1119330

Tolvanen, S., Jansson, J., Vesterinen, V. M., & Aksela, M. (2014). How to use historical approach to teach nature of science in chemistry education? Science and Education, 23(8), 1605–1636.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 12 Tsaparlis, G. (2014). The logical and psychological structure of physical chemistry and its relevance to the

organization/sequencing of the major areas covered in physical chemistry textbooks. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(3), 391–401. doi:10.1039/c4rp00019f

van Duzor, A. G. (2012). Evidence that teacher interactions with pedagogical contexts facilitate chemistry-content learning in K-8 professional development. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 23(5), 481–502. doi:10.1007/s10972-012-9290-3

Vos, M. A. J., Taconis, R., Jochems, W. M. G., & Pilot, A. (2010). Teachers implementing context-based teaching materials: a framework for case-analysis in chemistry. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 11(3), 193–206. doi:10.1039/c005468m

Vos, M. A. J., Taconis, R., Jochems, W. M. G., & Pilot, A. (2011). Classroom implementation of context-based chemistry education by teachers: The relation between experiences of teachers and the design of materials. International Journal of Science Education, 33(10), 1407–1432.

doi:10.1080/09500693.2010.511659

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 13

VEJLEDNING I LÆNGERE-VARENDE

FÆLLESFAGLIGE FORLÖB I NATURFAG –

VÆRKTÖJER OG ARTEFAKTBASERING

Lars Brian Krogh, Pernille Ulla Andersen, Harald Brandt, Keld Conradsen, Benny Lindblad Johansen, Michael Jes Vogt.

Læreruddannelsen I Aarhus, VIA University College, Danmark Correpondence: labk@via.dk

Abstract Periods of interdisciplinary project-oriented studies among the science subjects in grades 7.–9. have recently been made mandatory in Denmark, leading to a new, shared interdisciplinary end examination in the subjects. These new emphases call for teacher capacities to scaffold and

supervise students during independent group-work, e.g. facilitating subject integration, managing group processes, and building students’ interdisciplinary self-efficacy. Consequently, in the context of the teacher education we have initiated a design based research project to enhance student teachers’ capacities for supervision in interdisciplinary science projects. An intervention was trialed with 20 students in an Interdisciplinary Science Teaching course. Fundamental design features were our notion of artefact-based supervision, four specific supervision tools for in this context, and a progression of supervision interactions with teacher students (been supervised using various tools, using tools themselves, and assessing their usefulness for professional practice). Empirically, the artefact-based trials have been followed through logs of teacher students and teacher trainers, pre- and post-surveys of teacher students, and artefact-based interviews. Teacher students self-efficacy increased and at the end they were able to use (some of) our tools to identify supervisory problems and to devise supervision strategies themselves. Implications for next intervention design iteration are discussed.

Keywords Supervision, interdisciplinary teaching, teacher education, socio-cultural tools, boundary objects

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 14

1. Introduktion

Danske elever undervises i et integreret naturfag (“natur/teknologi”) til og med 6. klasse, hvorefter

undervisningsfagene biologi, fysik/kemi og geografi udskilles. I forbindelse med folkeskolereformen i 2014 i Danmark blev der imidlertid indført bindende krav om, at der i overbygningen gennemføres seks

fællesfaglige forløb på tværs af fagene – som afsæt for den afsluttende fælles mundtlig naturfagsprøve. Denne prøve er projekt-organiseret, idet eleverne med afsæt i én af de fællesfaglige forløbstematikker skal formulere deres egne problemstillinger, udarbejde arbejdsspørgsmål og besvare disse på en måde, som inddrager alle fag og viser, at de behersker fire grundlæggende naturfaglige kompetencer. I en periode på ca. 5 uger op til prøven arbejder eleverne selvstændigt eller i grupper i alle fagenes timer med at tilegne sig viden, opstille forsøg, skabe modeller og planlægge deres fremlæggelse. I hele det 3-årige forløb er der tale om krævende faglige og gruppedynamiske processer for eleverne, hvorfor de både må trænes forudgående og stilladseres undervejs. Stilladsering i form af gruppevejledning er essentielt, som hjælp for eleverne med hensyn til at tackle faglige udfordringer og støtte faglig integration, styrke deres faglige selvtillid (“self-efficacy”) i forhold til projektarbejdet, samt håndtere problemer i den længerevarende gruppeproces. Problemet er blot, at danske naturfagsundervisere i ringe grad er uddannet til at lave fællesfaglig, selvtillidsskabende procesvejledning. Traditionelt har fællesfagligt samspil og relaterede

vejledningsaspekter ikke haft større bevågenhed i læreruddannelsen i Danmark. Det er således kritisk at udvikle praksis på dette område af læreruddannelsen.

På læreruddannelsen i Aarhus har vi i de seneste to studieår arbejdet med dette udviklingsperspektiv, blandt andet har et tidligere fællesfagligt udviklingsprojekt (skoleår 2015–2016) især peget på, at

fællesfagligheden især udfordrer de lærerstuderende på deres faglige self-efficacy, samtidig med at de har svært ved selv at integrere bidrag fra fagene. Endelig har mange svært ved, når de forbereder fællesfaglig undervisning i teams med lærerstuderende fra andre naturfag, at italesætte og håndtere egne

gruppeprocesser.

På denne baggrund og med disse erfaringer har vi formuleret et Design Based Research studium (Anderson & Shattuck, 2012), som adresserer følgende forsknings- og udviklingsspørgsmål:

Hvordan kan man med en målrettet intervention/vejledningsindsats på læreruddannelsen hjælpe naturfaglige lærerstuderende til at håndtere fællesfaglige udfordringer, især knyttet til fællesfaglig self-efficacy, faglig integration, gruppeproces-opmærksomhed, samt gruppevejledning?

Denne artikel rapporterer de grundlæggende design-komponenter, empiri til belysning af første afprøvning, samt påtænkte justeringer i designet forud for næste runde.

2. Litteraturreview og teoretisk baggrund for designet

Litteraturstudier har godtgjort (se fx Czerniak & Johnson, 2014), at forskningen i tværfaglig/fællesfaglig naturfagsundervisning (E. Interdisciplinary or transdiscisciplinary teaching) er mangesidig, men lidet kumulativ. Der foreligger således ikke nogen autoritativ teoretisk ramme for denne type undervisning, blandt andet fordi der ikke er enighed om, hvordan faglige samspil kan forstås og kategoriseres. Relevant for vores arbejde har Klausen (2011) klassificeret fagligt samspil i en 4-trins-taxonomi efter voksende sagsorientering og stigende faglig integration. Niveau 3 benævnes “Fællesfaglighed/tværfaglighed” og er

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 15 indholdsmæssigt dækkende for intentionerne i de danske læreplaner. Omdrejningspunktet er her et arbejde omkring en fælles problemstilling, og sigtet er erkendelsesmæssig merværdi gennem integration af faglige bidrag. Fagene i sig selv er underordnede, men de er ikke aldeles opløste. Det er denne forståelse af fællesfaglighed, som ligger til grund for nærværende artikel.

I den internationale litteratur kan man finde beskrivelser af læreres barrierer og udfordringer i forhold til fællesfaglig (først og fremmest “interdisciplinary”) undervisning. Meier, Nicol, & Cobbs (1998) peger blandt andet på, at det for mange undervisere vil være en barriere, at fællesfaglig undervisning presser dem udenfor det vidensdomæne, hvor de er faglige eksperter. Martins (2012, p. 54) finder, at mange

lærerstuderende har lav self-efficacy i relation til interdisciplinær undervisning, samt at de typisk angiver manglende fortrolighed med undervisningsformen som væsentligste årsag. Spronken-Smith & Harland (2009) afdækker lærernes vanskeligheder ved at afgive kontrol over læreprocessen til eleverne i det problembaserede arbejde – herunder deres problemer med at udmønte en facilitator rolle, fx hvornår og hvordan der interveneres i gruppearbejdet. Mere generelt konstaterer Hmelo-Silver (2004, p. 261) et “lack of a sufficient number of skilled facilitators”. Achilles & Hoover (1996) pointerer, at både lærere og elever har et udtalt behov for at kunne håndtere gruppeprocesser og teamarbejde (p. 16). I samme tråd hedder det hos Mergendoller et al (2006): “effective PBL-teachers assess the readiness of their students to work in groups and provide instruction, practice, and remediation of deficient group process skills” (p. 605). Alt i alt er der således stor overensstemmelse mellem de fællesfaglige udfordringer, som ses i den internationale litteratur om færdiguddannede naturfagsundervisere, og de udfordringer, som vi tidligere observerede hos danske lærerstuderende.

Som en del af nærværende projekt har vi udviklet et begreb om artefaktbaseret vejledning. Dette hviler først og fremmest på et socio-kulturelt læringssyn, efter hvilket artefakter, symbolske værktøjer og selve dialogen i en vejledningssamtale medierer læring (Saljø, 2003).

Fra litteraturen om PBL og projektorienteret undervisning (fx Mergendoller, Markham, Ravitz, & Larmer, 2006; Pettersen, 1999) har vi tillige hentet generelle vejledningsstrategier for forskellige faser af problemorienteret arbejde.

Ved udarbejdelsen af de konkrete værktøjer har vi trukket på forskningsmæssige indsigter fra en længere række forskningsmæssige kilder, som vi af pladshensyn kun har kunnet antyde i Tabel 2 nedenfor.

3. Metode og design

Design Based Research (DBR) er karakteriseret ved følgende træk (se fx Krogh, 2016): § DBR tager afsæt i behov som praktikere i feltet har (praksis-relevans-forsikrende) § DBR har et design fokus (i modsætning til et effekt-fokus)

§ DBR bygger på ekspliciterede design-principper – og prøver at undersøge deres holdbarhed i kontekst

§ DBR har et dobbelt sigte – praksis OG teori:

§ At udvikle en iterativt optimeret praktisk løsning/intervention

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 16 Kontekst: Interventioner og empiri-indsamling foregik i tilknytning til et nyudviklet tværfagligt

naturfagsmodul på Læreruddannelsen i Aarhus i efteråret 2016. Modulet svarer til 10 ECTS og vælges aktivt af de studerende i deres studieforløb. På holdet deltog 20 lærerstuderende: 8 med fysik/kemi, 7 studerende med biologi og 5 studerende med geografi som undervisningsfag. 5 af artiklens forfattere bidrog som undervisere til modulet.

Design og designprincipper: I det følgende vil vi redegøre for de grundlæggende designkomponenter (A, B, C), som er vores prioritet i praktisk problemløsning. Det handler om vores koncept artefaktbaseret

vejledning, om den progressive forløbsopbygning, samt de konkrete vejledningsværktøjer, som blev udviklet og afprøvet i første afprøvning.

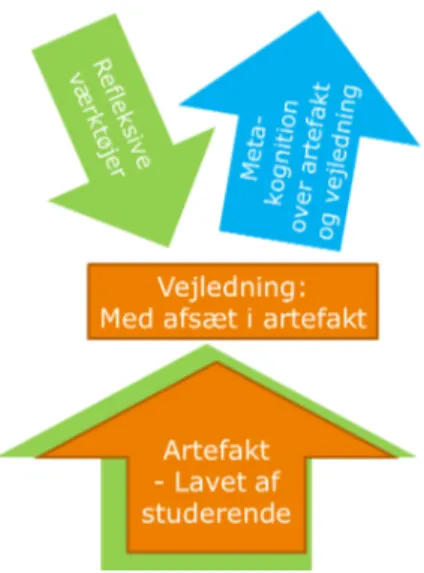

A. Designets begreb om artefaktbaseret vejledning (se Figur 1)

Grundelementerne i vores artefaktbaserede vejledning er, at de studerende medbringer et udarbejdet artefakt til vejledningen, at der bruges refleksive værktøjer til at sikre refleksion, og at der arbejdes progressivt med metakognition over

vejledningsprocessen. På forskellig vis kan de refleksive værktøjer drages ind undervejs, i henholdsvis artefaktskabelsen, selve vejledningen og den metakognitive slutfase. Fx kan et refleksivt selvevalueringsværktøj på udfyldt form godt være dét artefakt, som gruppen medbringer. De enkelte værktøjers funktion vil variere med anvendelsen, og er rimeligvis forskellig for underviser og studerende.

Den artefaktbaserede vejledning åbner for en række potentielle gevinster:

§ Kravet om artefaktbasering af vejledningen fokuserer de studerendes forberedelse og fastholder dem på læreprocessen.

§ Artefakterne giver vejlederen konkret indblik i de studerendes produkt- eller procesrettede problemer. Set fra et underviserperspektiv øger forhåndskendskab til en gruppes artefakt mulighederne for at sætte ind med den rette vejledning.

§ Velvalgte refleksive værktøjer vil kunne sætte fokus på kritiske aspekter af fællesfagligt, problembaseret arbejde, fx hvordan de faglige elementer integreres.

§ Velvalgte refleksive værktøjer (og afledte artefakter) kan bidrage til at åbne op for at italesætte og reflektere gruppeprocesser i en projektgruppe. Det kan være vanskelige diskussioner om fx grupperoller, kommunikation og arbejdsbelastning. Det skaber foci og handlemuligheder, for gruppen selv og for vejlederen, hvad angår at sikre en mere motiverende gruppeproces.

§ Refleksionen og den metakognitive modellering af vejledning fremmer de studerendes self-efficacy i forhold til selv at forestå vejledning.

§ Metakognitionen medvirker til at sætte fokus på de refleksive værktøjers styrker og svagheder, samt deres anvendelighed i forskellige kontekster. Sammen med de studerendes refleksion over,

Figur 1. Hovedtræk ved vores begreb om artefaktbaseret vejledning

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 17 hvordan de eventuelt vil kunne anvendes i en grundskolesammenhæng etablerer det værktøjerne som grænseobjekter mellem læreruddannelse og skolepraksis.

B. Forløbsopbygningen og den indlejrede progressionstænkning:

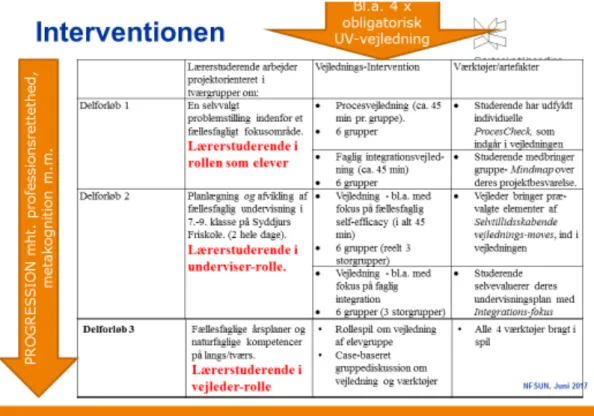

Interventionen bestod af tre delforløb, med lærerstuderende i forskellige roller og en stigende progression i deres vejledningsdeltagelse (se Tabel 1).

Tabel 1. Oversigt over interventionen omkring artefaktbaseret vejledning

I delforløb 1 blev de studerende sat i en rolle som elev. Med studerende fra andre fag skulle de besvare en selvvalgt fællesfaglig problemstilling. Undervejs modtog de både proces- og produktvejledning, og begge vejledningsseancer tog afsæt i forberedte artefakter (Procescheck henholdsvis Begrebskort).

I delforløb 2 blev de studerende sat i en underviserrolle, idet de i grupper skulle planlægge og gennemføre fællesfaglig undervisning på en friskole. Vejledningsseancerne skiftede karakter og havde i dette forløb blandt andet fokus på at udvikle de studerendes self-efficacy som fællesfaglige naturfagsundervisere. Én vejledningsgang havde tillige fokus på, i hvilken grad den planlagte undervisning formåede at integrere fagene på en hensigtsmæssig måde.

I tredje og sidste delforløb blev de studerende sat i situationer, hvor de skulle agere vejledere over for medstuderende. Der blev iscenesat forskellige rollespil i forhold til velkendte praksissituationer, og efterfølgende reflekterede holdet over udfaldet af vejledningen og hvordan den alternativt kunne være udført.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 18 Samlet set var der fra delforløb 1–3 en stigende progression i forhold til både professionsrettethed og metakognition.

C. Konkrete vejledningsværktøjer:

I projektet har vi udviklet/anvendt de fire værktøjer, som er anført i Tabel 2. Oversigten ekspliciterer værktøjernes fokus og primære funktion i forløbet, både ud fra et studerende og et underviserperspektiv. Fx fremgår det, at værktøjet Projektcheck på udfyldt form kan fungere som det artefakt en gruppe producerer forud for vejledning. Samtlige værktøjer er designet med øje for, at de kan fungere som grænseobjekter mellem læreruddannelse og (kommende) praksis i skolen, det vil sige de er tænkt at kunne anvendes begge steder.

Tabel 2. Værktøjer udviklet med henblik på artefaktbaseret fællesfaglig vejledning i projektet Refleksivt

værktøj

Primært

vejledningsfokus

Værktøjets funktion Grundlag

“Procescheck” Gruppeproces. Vejlednings-artefakt Lærende-redskab: co-refleksion/konfliktløsning/ metakognition Lærer-redskab: diagnostik/konfliktløsning Belbin (1993), Van Hauen et al (1995) “Selvtillidsskabende vejlednings-moves”

Faglig selvtillid (“self-efficacy”)

Eventuel lærende redskab: metakogntion Lærer-redskab: refleksion Bandura (1997), Dweck (1999), Ames (1992) Begrebskort – med integrations-refleksive prompts Fagfaglige elementer og overgribende sammenhænge – herunder faglig integration Vejlednings-artefakt Lærende-redskab: co-refleksion/metakognition Lærer-redskab: diagnostik/ refleksion/metakognition Novak (2012), Douma et al (2009), Mergendóller (2006)

“Integrations-fokus” Fællesfaglig integration (i forbindelse med undervisningsplan som artefakt) Lærende-redskab: co-refleksion/metakognition Lærer-redskab: diagnostik/ refleksion/metakognition Nikitina (2006), Biggs (1982)

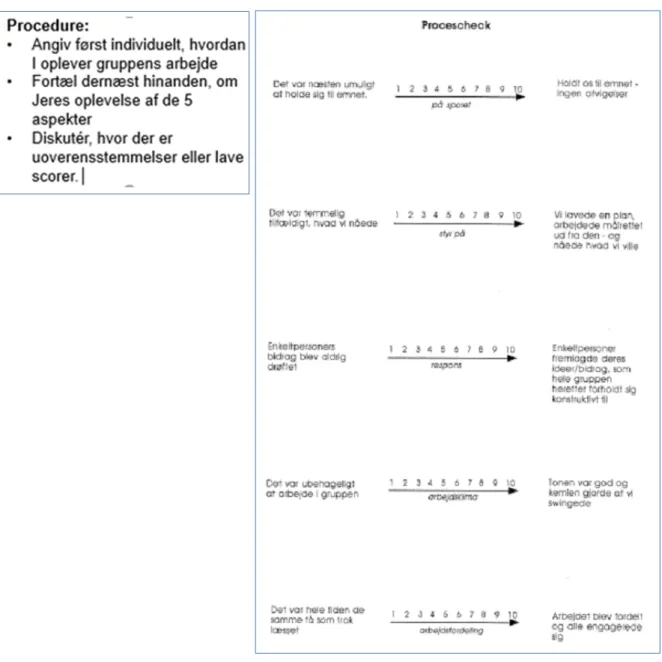

Værktøjet Procescheck

Værktøjet fremgår af Figur 2. Det trækker på litteraturen om gruppers arbejde og professionelle teams, blandt andet ved indkredse såvel kritiske produkt- som procesrettede aspekter af en gruppes arbejde.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 19 Værktøjet er nemt at administrere, og det kan i sig fungere som et hurtigt og uafhængigt

selv-evalueringsværktøj for en projektgruppe, fx ved afslutning af en arbejdsgang. Ved at lade gruppemedlemmer medbringe deres individuelle Procescheck-ratings som artefakt til en

vejledningssamtale skabes det nødvendige empiriske grundlag for, at man som vejleder kan diagnosticere og eventuelt indgå i konfliktløsende dialog om de faktorer, som typisk får grupper til at smelte ned: arbejdsdeling, gensidig respons og det psyko-sociale arbejdsklima i gruppen. I interventionen har de studerende brugt det som redskab i egne gruppeprocesser og diagnostisk i forbindelse med. vejledningscases.

Figur 2. Værktøjet procescheck.

Værktøjet Selvtillidsskabende Vejlednings-moves

Værktøjet er i første omgang tænkt som et redskab for vejlederen, idet det lister ni forskellige måder, hvorpå man som lærer i en fællesfaglig vejledningssituation vil kunne understøtte den lærendes selvtillid.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 20 De forskellige “vejlednings-moves” er extraheret fra en række motivationsteorier, først og fremmest

Banduras teori om Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997), men også teorier om Self-determination, Self-regulation, Goal Orientation og Attribution har bidraget.

Tabel 3 lister de 9 moves i den formulering, som de har været brugt i projektet. Det er en overvejelse at erstatte de teorihenvisende termer til fordel for mere hverdagsnære termer.

Tabel 3: Vejlednings-moves som ifølge motivationsteori tænkes at fremme lærendes (fællesfaglige) selvtillid

Konkret har dette værktøj været brugt i forbindelse med vejledning, hvor de lærerstuderende forlods har fremsendt produkt-udkast, fx en plan for påtænkt fællesfaglig undervisning som afsæt for en

artefaktbaseret vejledning. Underviseren har således både før og under vejledningen kunnet bruge værktøjet til at overveje hvilke vejlednings-moves det vil være hensigtsmæssigt at bringe i spil. Anvendt senere i det progressive forløb med de studerende har det været relevant at eksplicitere værktøjet for dem, og italesætte dets brug i forbindelse med vejledningen. Afslutningsvist har de selv skullet anvende

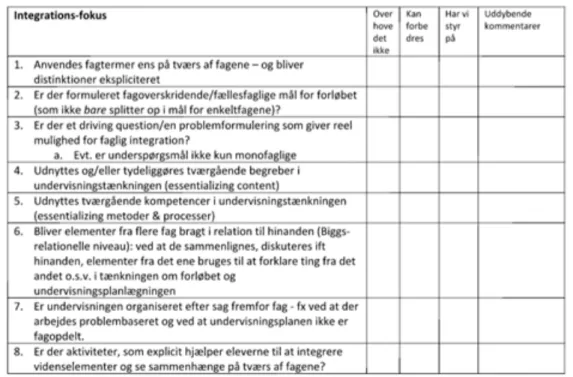

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 21 Værktøjet Integrationsfokus

Dette redskab (Tabel 4) samler opmærksomhedspunkter for fællesfaglig integration af bidrag fra de forskellige naturfag. Den viste form (Tabel 4) har været brugt ved vejledning af studerende, som har lavet udkast til undervisningsplan for et fællesfagligt forløb. Forlods har de studerende anvendt redskabet til kritisk selv at reflektere deres forløbsplan – og disse overvejelser trækkes ind i selve

vejledningsdiskussionen af forløbsudkastet.

Tabel 4. Redskabet Integrationsfokus med fokus på fællesfaglige sammenhænge

Empiriindsamling

Den artefaktbaserede vejledning kan anskues både ud fra et lærende og et vejlederperspektiv, og alt efter perspektivet kan vejledningsværktøjer med mere have forskellig funktion. Vores intervention opererer bevidst med en bevægelse mellem netop disse perspektiver – og i vores empirindsamling har vi søgt at opnå en tilsvarende dobbeltsidig empiri:

• Studerendes logbogsskrivninger efter hvert delforløb, blandt andet om vejledning • Studerendes artefakter, udviklet på baggrund af refleksive værktøjer

• Læreruddanneres logbogsskrivning i tilknytning til hver vejledningsseance og afslutningsvist. • Pre- og post-survey til lærerstuderende (blandt andet fællesfaglig self-efficacy og holdninger til

fællesfaglig undervisning. Styrken af Self-efficacy-beliefs fx målt med spørgsmål a la Hvor sikker er du på, at du vil kunne afvikle den fælles prøve i naturfagene?. Ved at spørge til forskellige aspekter af fællesfaglig undervisning fanges generaliteten af den fællesfaglige self-efficacy.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 22 • Observation af vejledningsseancer (2 stk.)

• Case-baserede gruppeinterviews (3 stk) med lærerstuderende ved afslutningen af interventionen. Her fik de studerende mulighed for at demonstrere i hvilken udstrækning de kunne bruge

værktøjer til

o at identificere vejledningsproblemer i en elevcase-beskrivelse

o at konstruere en hensigtsmæssig vejledningsstrategi for eleverne i casen o at reflektere værktøjerne i relation til egen (kommende) praksis.

4. Resultater – empiriske belæg for/imod designet

De lærerstuderendes udbytte i relation til DBR-målene skal nu præsenteres.De lærerstuderendes self-efficacy blev afdækket i pre- og postsurveys. Desværre besvarede kun 10 studerende begge surveys. Desto mere tankevækkende er det, at det faktisk er muligt både at iagttage statistisk signifikante (p<0.05) og systematiske forbedringer af samtlige målte aspekter af fællesfaglig self-efficacy (se Figur 3). Der er således belæg for at mene, at interventionen på dette punkt har været

vellykket.

Figur 3. Pre-og-post målinger af de lærerstuderendes self-efficacy i relation til forskellige fællesfaglige (“FF”) aspekter. Alle spørgsmål af typen Hvor sikker er du på, at du vil kunne …

Evnen til at bruge refleksive værktøjer i forbindelse med fællesfaglig vejledning blev først og fremmest afdækket via observation af de studerendes ageren i vejledningsrollespil og gennem de afsluttende case-baserede gruppe-interviews. Her skulle de studerende i mix-grupper i fællesskab bruge

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 23 case-data. Derefter skulle de udvikle en relevant vejledningsstrategi med inddragelse af værktøjerne Selvtillidsskabende vejledningsmoves henholdsvis Integrationsfokus. Endelig skulle de reflektere brugen af redskaberne i relation til deres egen (kommende) fællesfaglige praksis.

Analysen af audio-optagelserne fra disse seancer godtgør, at

• De studerende formår at identificere problemer med de to diagnostiske værktøjer • Evnen til at strategiudvikle m afsæt i værktøjer varierer:

o ProcesTjek/begrebskort er anvendelige in situ

o Vejledningsmoves/Integrationsfokus mere komplekse – værdsættes, men kræver større fortrolighed/mere træning

• De lærerstuderende formår at reflektere vejledning generelt - og har gode overvejelser om brugbarheden af de specifikke værktøjer i forhold til egen (kommende) praksis.

Disse centrale udbytte-målinger godtgør, at det indledende design er et kvalificeret første bud på en løsning på det fællesfaglige undervisningsproblem. Hvad angår de specifikke design-træk ved interventionen peger empirien på:

• Den artefakt-baserede vejledning:

• De lærerstuderende værdsætter i deres logbogs-entries om de første forløb primært vejledningsseancerne for deres produktrettede bidrag. I takt med at der skrues op for det metakognitive vokser deres påskønnelse af aktiviteterne som læringsmuligheder i forhold til vejledning.

• Underviserne er generelt positive i forhold til artefakt-baseret vejledning, som en kvalificering af den hidtidige vejledningspraksis:

• Selve artefaktbaseringen anses for ekstremt nyttig - som fælles og fokuserende device for vejledningen. I særdeleshed har det været givtigt, når artefaktet forelå på forhånd og kunne indtænkes i forberedelsen til vejledningen.

• Undervejs i forløbet har alle oplevet situationer, hvor en række af de forskellige typer af “potentielle gevinster” (se bullits ovenfor) faktisk har kunnet høstes.

Forløbsopbygningen med en progressiv anvendelse af forskellige vejledningsroller og metakognition: • Underviserne mener også, at der burde være metakognitive indslag om vejledning allerede i

tilknytning til de første vejledninger.

• Den progressive tildeling af forskellige vejledningsroller til de lærerstuderende værdsættes af disse, fx illustreret via følgende citat:’

“Det har virkelig været en stor hjælp til os…hvordan man skal ud i at vejlede ens elever i det…og vi har selv været igennem den samme vejledning og set det fra elevens perspektiv”.

• Det case-baserede evalueringsformat har vist sig at være et frugtbart afsæt for at træne, reflektere og co-konstruere praksis-relevant anvendelse af refleksive værktøjer i vejledning. Det kom til sidst i design-udviklingen, men kan med fordel anvendes i højere grad.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 24

De fire konkrete vejledningsværktøjer:

• I de indledende forløb havde de lærerstuderendes stort fokus på, hvad værktøjerne havde bidraget med til deres eget projektarbejde. Velfungerende grupper havde fx ikke det store procesudbytte af selv at udfylde Procescheck og var følgelig forbeholdne overfor værktøjets værdi. Flere grupper mente, at de havde haft for lidt gruppeproces til at bruge værktøjet. En mindre velfungerende gruppe undlod at bruge Procescheck i en situation, hvor de kunne have haft gavn af det. Først med etableringen af et tydeligt meta- og professionsperspektiv på vejledning blev værktøjerne for alvor påskønnet.

• Til slut opfatter de lærerstuderende generelt værktøjerne for relevante og nyttige:

“Det er altid rart at have et konkret værktøj. Når man står ude i praksis kan man hurtigt føle sig presset. Så er det rart at have noget konkret at falde tilbage på.”

• Underviserne har følt at alle værktøjer var nyttige, men nogle nemmere at bruge end andre. Diagnostisk vurderes alle værktøjer er være brugbare, mens det har vist sig vanskeligere at etablere et handlingsrettet Integrationsfokus i vejledningen.

5. Implikationer for næste design-iteration og afsluttende kommentarer

Projektet, som beskrevet her, er første runde i vores design baserede udvikling af et undervisningskoncept til læreruddannelsen. Empirien godtgør, at de grundlæggende design-komponenter et godt stykke henad vejen er brugbare, hvilket retfærdiggør en artikel i denne tidlige fase af DBR-forløbet. Alligevel er der design-justeringer, som vi vil medtænke i næste gennemløb (der af læreruddannelsestekniske årsager først bliver i E2018):• Tidligere deklaration af ideen om artefakt-baseret vejledning

• Fastholdelse af den progressive brug af studerende i multiple vejledningsroller - men med en opprioritering af metakognition om vejledning fra første forløb.

• Mere omfattende anvendelse af cases til træning/refleksion/co-konstruktion af vejledningspraksis • Peer-observation og/eller video-takes af lærerstuderende som vejledere i autentisk undervisning

(forløb 2) - som afsæt/cases for fælles refleksion over vejledning og kilde til vejlednings-self-efficacy (“vicarious experiences”, Bandura).

• Den sproglige tilgængelighed af Selvtillidsskabende Vejledningsmoves skal øges – ligesom anvendelsen af Integrationsfokus illustreres med eksempler på konkret

vejledningsadfærd/handlinger.

Empirisk vil vi i næste runde blandt andet styrke fokus på, hvordan de lærerstuderende håndterer fællesfaglig vejledning og bruger vejledningsværktøjer i en autentisk setting.

Samtidig med at tilgodese de lærerstuderendes fællesfaglige kompetencer har projektet fungeret som kompetenceudvikling for os som deltagende undervisere på læreruddannelsen. I erkendelse af, at vi også

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 25 kan blive skarpere til fællesfaglig vejledning, er det planen at bedrive opfølgende lektionsstudier om fællesfaglig vejledning i vores gruppe af naturfaglige læreruddannere.

Med denne indsats håber og tror vi at have leveret et bidrag til gavn for den fremtidige vejledning i projektorienteret og/eller fællesfaglig undervisning i naturfagene.

Referencer

Achilles, C. M., & Hoover, S. P. (1996). Exploring problem-based learning (PBL) in grades 6–12, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association

Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design Based Research – A Decade of Progress in Education Research? Educational Researcher, 41(1), 16–25.

Bandura, A. (1997). Efficacy – the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Czerniak, C. M., & Johnson, C. C. (2014). Interdisciplinary science teaching. In N. G. Lederman, & S. K. Abell (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (vol II ed., pp. 395–411). London and New York: Routledge.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16, 235–246.

Klausen, S. H. (2011). På tværs af fag - fagligt samspil i undervisning, forskning og teamarbejde. København: Akademisk Forlag.

Krogh, L. B. (2016). Professionel udvikling af naturfagslærere - brikker til et fælles afsæt. MONA (Matematik Og NAturfagsdidaktik), 4, 57–70.

Martins, D. M. (2012). Interdisciplinary teaching among pre-service teachers: The development of interdisciplinary teaching approaches among pre-service science and mathematics teachers. (Master of Arts in Education and Society, McGill University).

Meier, S. L., Nicol, M., & Cobbs, G. (1998). Potential benefits and barriers to integration. School Science and Mathematics, 98(8), 438–447.

Mergendoller, J. R., Markham, T., Ravitz, J., & Larmer, J. (2006). Pervasive management of project based learning: Teachers as guides and facilitators. I C. M. Evertson, & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 583–615)

Pettersen, R. C. (1999). Problembaseret læring. København: Dafolo.

Saljø, R. (2003). Læring i praksis – et sociokulturelt perspektiv. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Spronken-Smith, R., & Harland, T. (2009). Learning to teach with problem-based learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 10(2), 138–153.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 26

DANISH GEOGRAPHY TEACHERS

ASSESSMENT OF OWN TEACHER

PROFESSIONALISM

Søren Witzel Clausen

Department of Teacher Education, VIA University College, Denmark Correspondence: socl@via.dk

Abstract In Danish schools, the geography curriculum synthesises content from both natural and human geography. The subject formally belongs to the science domain, but research shows that geography teachers’ identity differs from that of their science colleagues. This article explores how geography teachers perceive their strengths and weaknesses with regard to subject matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. A survey was sent to geography teachers in five municipalities in the central part of Jutland. The results indicate only a small variation in the teachers’ perception of strengths and weaknesses with regard to subject matter knowledge. Greater variation is, however, seen in the teachers’ perception of own pedagogical knowledge; e.g. they feel least competent to carry out practical work/fieldwork and to work with models and animations. According to the PCK

consensus model, orientations and beliefs are important amplifiers or filters, which can influence geography teachers’ classroom practice, and thus potentially also affect the cooperation with their science colleagues, e.g. when implementing the new common science exam for students finishing lower secondary school in Denmark.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 27

1. Introduction

In the Danish lower secondary school, geography is part of the natural science domain, although the subject includes both human geography and physical geography, covering topics from the human, social and natural sciences. Hence, geography can be characterised as a synthetic subject (Nielsen, 2001). Central to the subject is geographical identity (local, regional and global), orientation skills and

understanding of the surrounding world (Kristensen, 2011). If students are to acquire deeper substantive and procedural knowledge of geography, the teacher might help them by asking questions related to perception, space, place, scale, distribution, distance, historic time and interaction/causality (Cachinho, 2005). Furthermore, teaching geography involves pedagogical reflections related to student learning, and how the students can be supported by asking questions such as: What? Where? How? Why? What for? What to do? (Cachinho, 2005). This way, geography can be put into a broader perspective and become a discussion of e.g. how the rise in temperature affects people’s living conditions in Greenland or

Bangladesh, and how we can help change our patterns of consumption and perhaps some of our more basic social structures. Thus, the subject of geography will not only be concerned with students’ acquisition of certain concepts, theories and models for their own sake. By including current, ethical and

socio-scientific issues, geography and the other science subjects might contribute to preparing students to become active democratic citizens (e.g. Sjøberg, 2006; Zeidler & Keefer, 2003).

When teaching the subject, different kinds of representations are used, e.g. models/maps, graphs, pictures, letters and numbers. Therefore, geography teachers need to have both extensive subject matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge.

Since the implementation of a common oral science exam in Denmark, students have been assessed according to four science competences: inquiry, modelling, putting into perspective and communication (Danish Ministry of Education, 2014). Hence, geography teachers must be able to teach the subject of geography, scaffold students’ acquisition of the four competence areas and cooperate with their science colleagues. It is therefore highly relevant to investigate geography teachers’ subject matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge.

These two knowledge categories were integrated into a third knowledge category called pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) by Lee Shulman (1986), which was introduced as: “… the most regularly taught topics in one’s subject area, the most useful forms of representation and those ideas, the most powerful analogies, illustrations, examples, explanations, and demonstrations – in a word, the ways of representing and formulating the subject that makes it comprehensible to others” (Shulman, 1986, p. 9). Since then, the concept has been further developed, and in 2015 the PCK consensus model was introduced (Gess-Newsome, 2015). In this model, PCK was described as the teachers’ actions in the classroom, as a function of the teachers’ pedagogic and topic-specific knowledge, as well as the teachers’ beliefs and understandings (Ellebæk & Nielsen, 2016; Gess-Newsome, 2015). Teachers’ professional knowledge bases originate from research and best practice and consist of knowledge of assessment, pedagogy, content, students and curriculum. Topic-specific professional knowledge is integrated knowledge of instructional strategies, content representations, student understandings, science practices and habits of

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 28 mind, and this knowledge category thereby combines subject matter, pedagogy and context

(Gess-Newsome, 2015).

Only a few research articles have explored Danish geography teachers’ topic-specific professional knowledge and teacher professional knowledge bases (Clausen, 2016; Clausen, 2017; Jensen et al., 2000), and none of these emphasise geography teachers’ assessment of their own topic-specific professional knowledge. This may be of importance in the teaching of students and cooperation with science colleagues, e.g. in connection with the new common science exam.

In the summer of 2017, the exam was held for the first time including all ninth-grade students in Denmark. It is a two-hour oral group exam, where the student’s science competences (inquiry, modelling, putting into perspective and communication) are assessed. At the examination, the students have to draw one of the following six common topics, which they have worked with in advance:

• Production with sustainable exploitation of the natural environment. • Sustainable energy supply at local and global level.

• Drinking water supply for future generations.

• The discharge of substances by individuals and society.

• The impact of radiation on the living conditions of living organisms. • The importance of technology for human health and living conditions.

During the examination, all three science subjects – geography, biology and physics/chemistry – must be represented (Danish Ministry of Education, 2016).

The exam requires science teachers to include the four science competences in the teaching, and it also requires science teachers to cooperate. However, there are significantly fewer practicing geography

teachers who have a specialisation, compared to their science colleagues. Approximately 50% of geography teachers have a specialisation within their subject, compared to 70% of biology teachers and 85% of physics/chemistry teachers (Clausen, 2016; Hune, 2009; Nikolajsen & Larsen, 2013). Geography teachers often have a different, more humanistic, teacher profile than their biology and physics/chemistry

colleagues, and they rarely identify themselves as science teachers, except geography teachers who have also taken physics/chemistry as a subsidiary subject (Nielsen, 2011). Compared to biologists, many geography teachers also show signs of low self-efficacy in relation to physics/chemistry content, even taking into account differences in upper secondary education (Nielsen, 2011). This may affect geography teachers’ ability to include their science competences when teaching the subject.

Research question

What characterises Danish geography teachers’ perception of their own professional knowledge bases and topic-specific professional knowledge?

The results will be interpreted in terms of possible implications for geography teachers’ participation in the common science exam.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 29

2. Method

In 2015, a survey was sent to all 192 geography teachers at 72 schools, using the SurveyXact tool. The schools were evenly distributed between five municipalities in the Central Denmark Region in Jutland, Denmark, and 45 geography teachers answered all the questions in the survey (response rate of 23.4%). The relatively low response rate could be due to the implementation of a comprehensive Danish school reform half a year before, combined with new working time regulations imposed by the Danish Government (Clausen, 2016).

When the survey was distributed, some principals mentioned that their teachers were involved in several government-induced evaluations in relation to these new initiatives, and that their teachers might be overwhelmed with replanning their teaching and new evaluation tasks.

The number of respondents only represented a small fraction of the total number of geography teachers in Denmark, approximately 1.6% of a total of 2,855 teachers (Nikolajsen & Larsen, 2013, p. 9). However, half of the teachers who answered the survey had completed a geography teacher education, and two thirds of them were men, which is fairly in compliance with the general picture of Danish geography teachers (Hune, 2009; Jensen et al., 2000; Nikolajsen & Larsen, 2013).

The geography teachers who responded to the survey were also busy implementing the school reform and changed working time regulations. Therefore, there might be a bias, because the respondents may be geography teachers with a relatively strong professional identity and understanding of their own professional pedagogic skills.

In summary, the results of this survey can only point out trends concerning geography teachers’ professional knowledge bases and topic-specific professional knowledge.

The geography teachers were asked to assess their professional knowledge base with respect to nine common pedagogical interventions which were estimated to be a significant part of a geography teacher’s teaching repertoire. The teachers were also asked to assess their topic-specific professional knowledge in relation to ten common geography topics. All 19 items were formulated as closed questions: “I am

professionally strong within ...”. The teachers were asked to rate the statements on a five-point Likert scale (Krosnick & Presser, 2010) from “incorrect” (= 1) to “correct” (= 5). The average value and the

corresponding standard error of the mean (SEM) of all nineteen items were calculated. The fact that the SEM values of the different items did not overlap indicates that the probability of the geography teachers having different positions with regard to these items is 90% or more. Because of the low number of respondents (n = 45), no further sophisticated statistical analysis was conducted.

3. Results

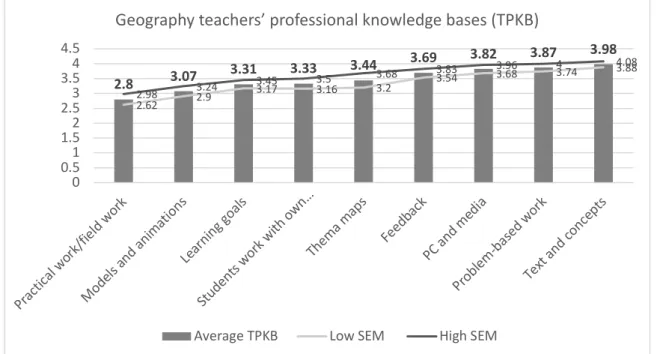

The average values of the geography teachers’ assessment of own professional knowledge bases (figure 3) and topic-specific professional knowledge (figure 4) are shown as bar charts and numbers in bold. The upper and lower SEM values for each average value are indicated both graphically and as numbers.

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 30 Geography teachers’ professional knowledge bases

Figure 3 shows that the average values of the geography teachers’ responses with respect to their

professional knowledge bases vary considerably. The geography teachers give their professional knowledge bases related to Practical work/fieldwork (2.80) and Models and animations (3.07) the lowest score. At the other end of the scale with the highest score are Text and concepts (3.98) and Problem-based work (3.87).

Figure 3. The geography teachers’ assessment of own professional knowledge bases according to nine common pedagogical efforts.

Geography teachers’ topic-specific professional knowledge

In figure 4, the results show that NoS (3.60) and Economic geography (3.64) receive the lowest score, while Water cycle (4.11) and Rich and poor (4.07) are found at the other end of the scale with the highest score. The geography teachers generally give their topic-specific professional knowledge a higher score than their professional knowledge bases, and the difference between the items with the lowest and highest scores is smaller compared to the professional knowledge bases (figure 3). However, the differences between the lowest topic-specific professional knowledge average value (NoS (3.79)) and the highest topic-specific professional knowledge average value (Rich and poor (3.91)) are still considerable, since the SEM values do not overlap. 2.8 3.07 3.31 3.33 3.44 3.69 3.82 3.87 3.98 2.62 2.9 3.17 3.16 3.2 3.54 3.68 3.74 3.88 2.98 3.24 3.45 3.5 3.68 3.83 3.96 4 4.08 0 0.51 1.52 2.53 3.54 4.5 Practi cal w ork/fi eld w ork Mode ls and anim ation s Learn ing go als Stude nts w ork w ith ow n… Them a map s Feed back PC an d med ia Proble m-ba sed w ork Text and c once pts

Geography teachers’ professional knowledge bases (TPKB)

NFSUN 2017 Proceedings | 31

Figure 4. The geography teachers’ assessment of own topic-specific professional knowledge with respect to ten common geography topics.

4. Discussion

The new common science exam in Denmark is competence-based, emphasising that students must be able to carry out inquiry-based work related to problems in the surrounding world and use models to understand it, as well as putting into perspective and communicating their discoveries (Danish Ministry of Education, 2014).

Variety in teaching methods is important, acknowledging students’ different ways of acquiring the

competences referred to in the curriculum (e.g. Hope, 2009; Nielsen, 2001). Practical work/fieldwork is an important issue in Danish school science, both by tradition and since one of the assessed competences refers to inquiry. In international research, practical work/fieldwork is also emphasised as the foundation for students to gain a deeper understanding of their surrounding world, and “It brings conceptual, cognitive, procedural and social gains much of which would be lost without the particular opportunities fieldwork provides” (Lambert & Reiss, 2014). However, in the survey (figure 3), geography teachers give practical work/fieldwork the lowest score. This result is in line with another Danish study in which 80% of the geography teachers rarely or very rarely conducted practical work (Jensen et al., 2000, pp. 31–32). In the last ten years, increased emphasis has been placed on clear learning goals in education (Clausen, 2016), but according to the survey results, geography teachers do not feel particularly competent to work with specific learning goals in the geography teaching. On the other hand, the geography teachers feel competent to help students work with text and concepts. When asking some of the key questions mentioned by Cachinho (2005), teaching geography becomes not only a matter of students acquiring knowledge about specific geographical concepts, theories and models. It becomes a subject in which the students’ personal development is equally important, with the aim of preparing the students to become

3.6 3.64 3.82 3.87 3.91 4 4.02 4.04 4.07 4.11 3.42 3.51 3.66 3.72 3.84 3.86 3.86 3.88 3.91 3.95 3.78 3.79 3.96 4.02 3.97 4.14 4.18 4.2 4.23 4.27 0 0.51 1.52 2.53 3.54 4.5 Nature of Sc ience (NoS ) Econ omic geog raphy Earth scien ce Regio nal g eogra phy Globa lizatio n Demo graph y Weath er an d clim ate… Susta inable deve lopme nt Rich a nd po or Water cycle