Malmö University Culture and Society Urban Studies Master Programme Leadership for Sustainability (SALSU)

Emission Compensation as Companies’ Sustainability Strategy:

Hindering Genuine Sustainability or Striving Towards It?

I

ndividual Consumers’ Perspective.

Anna Karlsson & Anna-Erika Korpi

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and

Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability

(OL646E), 15 credits

Spring 2019

Supervisor: Ju Liu

Abstract

This study was designed to explore how consumers perceive voluntary emission compensation as a companies’ sustainability strategy and how to achieve common action between companies and individual consumers towards sustainability. Emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy has appeared to be a complex strategy from the consumers perspective, and there are multiple challenges in order to implement it effectively. The study includes 20 individual consumers which were examined through five different focus groups, with the focus on attitudes towards sustainability and emission compensation. In the study, we combine companies’ communication with signal theory to individual consumers’ consumption behaviour by applying the theory of planned behaviour. The main findings were that in general, individual consumers do not believe that voluntary emission compensation is an effective strategy towards sustainability. Instead, individual consumers indicate regulations as a requirement in order to effectuate emission compensation. Moreover, individual consumers seem to have low trust in companies’ sustainability communication in general because the information on emission compensation was specifically lacking. This study adds in-depth analysis of consumers perceptions of compensated everyday life products, such as food, to the existing body of research which has mainly focused explicitly on aviation and air travel industries. Moreover, these studies have been quantitative in nature and our study reveals the deeper foundations why consumers think as they do.

Key Words

Emission Compensation, Individual Consumer, Consumption Behaviour, Companies’ Sustainability Strategy, Sustainability & Communication

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 0

1. Climate Change and Emission Compensation ... 1

1.1 Climate Change, Sustainability and Human Activities ... 1

1.2 Emission Compensation ... 1

1.2.1 The Role of Company in the Process of Emission Compensation ... 2

1.2.2 The Role of Individual Consumer in the Process of Emission Compensation ... 3

1.3 Research Problem ... 3

1.4 Purpose and Aim ... 5

1.5 Research Questions ... 6

1.6 Previous Literature ... 6

1.6.1 Sustainability & Emission Compensation as a Companies’ Sustainability Strategy 6 1.6.2 Relevant Actors in the Process of Emission Compensation ... 7

1.6.3 Consumers and Emission Compensation: Knowledge - Behaviour ... 7

1.7 Delimitations ... 8

1.8 Structure ... 9

2. Theoretical Framework ... 10

2.1 Communication... 10

2.1.1 Signal Theory ... 10

2.2 Individual Consumer’s Awareness and Knowledge ... 12

2.2.1 Theory of Planned Behaviour ... 12

2.2.2 Willingness to Pay Emission Compensation ... 13

2.3 Linking Companies with Consumers’ Consumption Behaviour ... 13

3. Research Design ... 15

3.1 Data Collection ... 15

3.1.1 Focus Group ... 16

3.2 Data Analysis ... 17

3.3 Delimitations of Method ... 17

3.4 Quality and Ethics ... 17

4. Analysis ... 18

4.1 Thematic Analysis of Results ... 18

4.1.1 Individual Environmental Knowledge and Behaviour ... 20

4.1.2 Emission Compensation as Companies’ Sustainability Strategy ... 21

4.1.3 Responsibility to Emission Compensate ... 22

4.1.5 Effectiveness of Emission Compensation ... 25

5. Discussion ... 27

6. Conclusion ... 29

References ... 30

1

1. Climate Change and Emission Compensation

Sustainable development and particularity climate change have been acknowledged as one of the most important challenges of 21st century (Wright & Nyberg, 2015; Silvius & Schipper, 2014; Sachs, 2015). Sachs (2015) highlights: “Climate change affects every part of the planet, and there is no escaping from its severity and threat” (p. 394). One way of addressing the harmful impacts on climate and nature is emission compensation which has been increasingly popular tool to mitigate emissions and fight against climate change. Emission compensation aims to neutralise emissions caused and to achieve neutral or positive environmental impact. Different actors on different levels have adopted this approach either through regulations or voluntary schemes. Particularly, voluntary sustainability strategies have attracted companies’ attention in the global North to control the negative environmental impacts, and companies are making commitments, especially to boost consumers and investors trust (Taiyab, 2006; Jochnick & Bickford, 2016).

1.1 Climate Change, Sustainability and Human Activities

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] report (2018), there will be robust differences in regional climate conditions between present and the future if the average global temperature rises between 1.5°C and 2°C. Increasing temperatures in most land and ocean regions, hot extremes in the most inhabited regions, heavy precipitation in several regions, and increased probability of droughts and precipitation deficits in some regions. In addition, the report states that it is highly likely that the climate change is caused by human-induced greenhouse gases (GHGs), most significantly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and the unsustainable land use (IPCC, 2018). Thus, there is an increased need for protection of natural habitats and ecosystems, preparations for sea-levels rise and the use and conservation of natural resources (Birnie, Boyle & Redgwell, 2009; Sachs, 2015). Moreover, it is crucial to respect the planetary boundaries, mitigate emissions and to decrease already existing greenhouse gases (Holden, Linnerud & Banister, 2017).

The concept of sustainability often includes the idea of balancing the social, environmental and economic world, without compromising the opportunities of future generation to live good life (Sachs, 2015; Holden, et al., 2017). In environmental terms, sustainability emphasizes that human activities should not deplete our natural resources and pollute (Wright & Boorse, 2011). Yet, in the name of economic growth many of the human activities are exploiting the nature and different actors, such as companies and consumers, make unsustainable decisions which result in declining biodiversity and essential ecosystems and increasingly high amount of GHGs (Wright & Boorse, 2011; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017; Sachs, 2015; Wright & Nyberg, 2015; Holden et al., 2017). Reaching sustainable development requires a global response where all actors take collective responsibility to act in sustainable way (Wilby, 2017; Sachs, 2015). However, the range and complexity of issues related to climate change and uncertainty regarding the nature, severity and timescale of possible climate effects have made the task of reaching an agreement how to tackle climate change a challenging issue.

1.2 Emission Compensation

Emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy has grown rapidly over past decades (Lovell, Bulkeley & Liverman, 2009; May, Hobbs & Valentine, 2017). Hence, it is relatively new approach for companies to mitigate their emissions and answer challenges related to sustainability. Sitra, Finnish Innovation Fund (2019) defines emission compensation as: “The purchasing of emission reduction units to compensate for emissions caused. The funds are used, for example, to support the use of renewable energy or sustainable use of land and forests across the world. The aim is to prevent climate change”. In other words, the idea behind all types of environmental compensation strategies is similar: mitigate/neutralise environmental impact by buying or trading external compensation units from a third party to compensate unavoidable emissions and ecological losses. The academic literature does not have a strong consensus on environmental compensation discourse. In addition, there are multiple definitions on environmental compensation and standards and frameworks are ongoingly processed and developed (Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme [BBOP], 2012a, b). Moreover, there are various types

2 of compensatory measures such as environmental offsets, development and green funds used for ecological conservation, and other types of direct investments on environment (Gonçalves, Marques, Soares & Pereira, 2015; Dhanda & Murphy, 2011; Lodhia, Martin & Rice, 2018). Dhanda and Murphy (2011) map three different type of offset projects which are used commonly: carbon dioxide offsets, renewable energy credits and cap and trade. In addition, biodiversity offsets are applied to achieve positive and measurable gain for biodiversity. Biodiversity offsets are an example of a specific category of compensation aiming to show transparently and quantitatively how flora and fauna benefits (Gonçalves et al., 2015). In this paper, emission compensation relates to all these different types of compensatory measures, and the type of compensatory measure is not specified.

The compensatory markets include regulatory and voluntary schemes. Particularly, voluntary projects related to increasing the amount of carbon sinks to reduce already existing CO2 and investing in renewable energy and new technologies have gained more and more attention as a strategy to mitigate emissions from business actors (Sitra, 2019; Gössling, Broderick, Upham, Ceron, Dubois, Peeters & Strasdas, 2007; Lovell et al., 2009). However, emission compensation has been criticised for being a strategy which transfers responsibility into marketable securities (Dhanda & Murphy, 2011), forwards the environmental responsibility to other actors and allows business to continue business-as-usual (Lovell et al., 2009). Thus, economic gains are still prioritized (Holden et al., 2017). The lack of consensus on enforcing framework or regulations on compensatory measures has led companies and other organisations to approach compensatory mechanisms from wide variety of directions, with various motivations and with various levels of effective implementation actions. Similarly, Eijgelaar (2011) notes: “previous assessments have revealed great differences in the project standards, calculation methods, transparency and project verification of offset schemes” (p. 283). In addition, Gonçalves et al. (2015) articulate challenges related to biodiversity compensation. On the conceptual level they focus on issues, such as “choice of metric, spatial delivery of offsets, equivalence, additionality, timing, longevity, ratios and reversibility” and on the practical level “compliance, monitoring, transparency and timing of credits release” (p. 61).

1.2.1 The Role of Company in the Process of Emission Compensation

Today’s companies are powerful actors which have direct possibilities to influence and impact on large entities of stakeholders, supply chains, production, consumption as well as the capacity and resources to confront the environmental challenges (Bonnedahl, 2012; Wright & Nyberg, 2015). In other words, companies have the potential to be a transformative force for good (Nolan, 2016). Wright and Nyberg (2015) articulate the dual role of corporations: “corporations are the principal agents in the production of GHG emissions in the global economy; on the other hand, they are also seen as our best hope in reducing emissions through technological innovation” (p. 3). Therefore, companies need to determine how they contribute and what is the appropriate level of their influence: “For companies that are committed to improving their environmental and social performance, the difficulty is no longer whether to implement sustainability, but how” (Epstein & Roy, 2001, p. 586).

Like mentioned earlier, an increasing number of companies have undertaken voluntary compensatory measures to reduce their emissions or become carbon neutral/positive (Taiyab, 2006): “Buying into voluntary offsets is essentially about taking ‘personal responsibility’ for the impact of one’s actions on the climate” (Taiyab, 2006, p. 17). The role of companies is to facilitate the emission compensation process either automatically during the process of production or through consumption (Lovell et al., 2009). Previously, emission compensation was mainly seen as a sustainability strategy among largely polluting industries, such as energy and transportation, to fight the environmental impact of their operations, production and/or supply chain (Dhanda & Murphy, 2011; Martin, Evans, Rice, Lodhia & Gibbons, 2016). Today, however, various types of companies in different industries are engaging to emission compensation to improve their green brand image (Taiyab, 2006; ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019). Hence, emission compensation has become common part of companies’ sustainability and marketing strategies (Taiyab, 2006).

3 Emission compensation is a complex strategy in the private market sector. Hence, the processes through which emission compensation have been made possible to consume have remained remote for individual consumers (Lovell et al., 2009). Companies need to consider the environment and various actors, especially the individual consumers who buy these products and create demand in order to implement emission compensation effectively into practice. Yet, a question here remains: is emission compensation sustaining consumption and hindering genuine sustainability or is it striving towards it?

1.2.2 The Role of Individual Consumer in the Process of Emission Compensation

Today’s consumption is largely based on our capitalist market structure; consumers create demand and companies answer with supply. The ways people’s values and attitudes are translated into consuming behaviour support today’s ways of production and consumption, and therefore, the role of individual consumers in implementing emission compensation is emphasised (Hannigan, 2014; Palazzo, Morhart & Schrempf-Stirling, 2016; Wilby, 2017). The modern Western societies are mainly determined by short-sightedness and materialistic values within consumption (Palazzo et al., 2016). However, green, ethical consumption has increasingly grown as a strategy among companies, and also influenced in consumers consumption (Sörqvist & Langeborg, 2019; ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019). These strategies are placing consumer in a position to make the responsible, sustainable active choice (ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019; Lovell et al., 2009; Palazzo et al., 2016).In the case of emission compensation, individual consumers operate in the voluntary scene. Individual consumers can be considered making either an active sustainable choice by paying extra or passively choosing to buy a product which is compensated. However, in other words, consumer makes the final decision whether to support a compensated product/service. What is notable, when an individual consumer contributes to emission compensation, the consumer does not receive something tangible in return (Lovell et al., 2009). Instead, the consumer must rely on the information which is available through the companies’ communication channels. Lovell et al. (2009) point out the practical challenges related to emission compensation from consumers perspective: “complex characteristics of today’s products and the current lack of international regulation and labelling schemes for voluntary compensation” (p. 2360) make the concept difficult to grasp. Hence, individual consumers have not received sufficient information and they are in need knowledge in order to implement emission compensation in practice (Lovell et al., 2009; Eijgelaar, 2011; Gössling, Haglund, Kallgren, Revahl & Hultman, 2009).

Furthermore, the problematics of climate change can be seen in phenomena that increasing knowledge on climate change has not led into effective action and change of behaviour (Wright & Nyberg, 2015; ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019). This can be connected that we are living in an anthropogenic era (Ruddiman, 2003), which implies that moral consideration only takes place when there is value in terms of human goals (Ammenberg, 2012; Sörqvist & Langeborg, 2019). Some critics highlight the issue that narrow anthropocentric approach declines many values, for example, unknown values in the future, such as intangible climate change or emission compensation (Ammenberg, 2012). On the contrary, sustainable development goals are mainly set to prevent possible future environmental and human catastrophes. Despite of the individual consumers’ values, the world we live in continues to change which requires us to change with it. The demand to change consuming behaviour, to act and to find common solutions for environmental challenges is crucial and different actors on different levels need to come up with new strategies and approaches as well as change attitudes how we value our lives and environment (Wilby, 2017; Wright & Nyberg, 2015; Palazzo et al., 2016).

1.3 Research Problem

Responsible consumption (SDG 12) and urgent climate action (SDG 13) have been cleared as part of the most important goals among others for sustainable development (United Nations [UN], 2019). In relation to all these goals, mitigation of emissions and changing individuals’ consumption habits is necessary. Therefore, the role of companies and consumers to act together is pronounced. However, currently there is a lack of collaboration between these actors to fight against climate change (Giddings,

4 Hopwood & O’Brien, 2002). Companies’ sustainability efforts are not communicated effectively to the individual consumers and the information has remained inconsistent and unclear. Moreover, diverse stakeholder groups still struggle to see the environmental effects of sustainable strategies; and the environmental and societal issues have continued to be part of the daily life in many parts of the world (Ferdig, 2007). Moreover, the current consumption patterns are extremely unsustainable and must be changed (Palazzo et al., 2016). However, it has been noted that sustainability strategies which improve efficiency and cost reduction can result to more consumption and overall GHG emissions (Wright & Nyberg, 2015). Therefore, companies should aim to genuine sustainability and genuinely changing individual consumers’ habits.

The process of developing an effective emission compensation is not easy in today’s complex organisations and economic system; and therefore, consists of many dimensions. From companies’ perspective, engaging in compensation strategies show the interest to tackle the issues; and first and foremost, it discloses that there is an environmental problem related to companies’ operations (Eijgelaar, 2011; Blasch, 2013). Thus, engaging in compensatory mechanisms requires companies to change from business-as-usual to more integrated approaches (Giddings et al., 2002; Holden et al., 2017). Currently, many of the environmental and social responsibilities of companies do not often permeate the company as a whole and sustainability is seen as separate entity (Porter and Kramer, 2011). Porter and Kramer, (2011) state: “we still lack an overall framework for guiding these efforts, and most companies remain stuck in a “social responsibility” mind-set in which societal issues are at the periphery, not the core” (p. 4). Hence, consumers’ attitudes toward companies’ sustainability efforts have remained cynical (ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019). On the other hand, companies cannot act alone to reach sustainability. They need the support from consumers in order to implement emission compensation effectively. Hence, the role of consumers and consumption is highlighted.

Companies’ strategies to work with emission compensation vary greatly. Some companies include compensation to the prices of the product or service, some require consumers loyalty and memberships to compensate, and some give the responsibility for the consumer to buy compensation voluntarily and pay an extra fee (Taiyab, 2006; Lu & Shon, 2012). Yet, it always comes to the consumer to make the final decision whether to buy a product/service in the first place, to buy the product if the compensation is included in the price or to pay extra fee for the compensation (Holden et al., 2017; Dhanda & Murphy, 2011). Therefore, in relation to emission compensation as a strategy: can it be a functioning strategy to achieve common action in relation to sustainability from individual consumers perspective? Can emission compensation be misleading for the consumer to make the decision and evaluate companies’ environmental efforts, or does it blur the lines who has the responsibility to act and pay for the negative environmental impact (Lovell et al., 2009)? The companies can be considered to place consumers in a position to make the responsible choice even though emission compensation is the sustainability strategy of the company in the first place. In addition, to give the choice to consumer can be problematic. Hannigan (2014) and Kuhn and Deetz (2008) highlight that sustainability has many definitions because individuals have different perceptions and preferences about environmental problems and how urgent they are these can depend on the individual's conflicts with diverse interests and cultural values.

Moreover, companies have multiple ways of presenting the data and communicate their emission compensation to the individual consumers (Picture 1).

5

Picture 1. Different kind of labels for emission compensation.

Hence, emission compensation as sustainability strategy has remained a complex concept for individual consumers to comprehend. The problem therefore rises how to effectuate the implementation of voluntary emission compensation and shape individual consumers behaviour towards sustainable outcomes? Like mentioned above, companies have variable strategies to implement and communicate emission compensation which has resulted in consumers’ limited knowledge on the topic overall (Gössling et al., 2009; Lovell et al., 2009; Eijgelaar, 2011). The current research reveals the individual consumers’ interest towards emission compensation (Gössling et al., 2009); however, the in-depth knowledge on consumers’ perspective is limited. Therefore, our research focuses on how individual consumers perceive emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy and what is needed in order to effectuate companies’ voluntary emission compensation.

1.4 Purpose and Aim

The purpose of the thesis is to explore how consumers perceive emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy and how to achieve common action between companies and individual consumers towards sustainability. Moreover, the purpose is showcasing the practical points how common action for change can be shaped from individual consumers’ perspective. The purpose is to explore consumers perspective in emission compensation and how they would like companies to work with it. Therefore, we have aimed to investigate whether consumers consider emission compensation an effective way to fight against climate change and how the companies’ compensatory efforts are communicated to

6 consumers from consumers’ perspective. In addition, we have aimed to explore the consumer willingness to pay for the voluntary emission compensation.

In other words, the aim of the thesis is to link individual consumer’s perspective together with companies’ role in the case of emission compensation. We combine companies’ communication with signal theory to individual consumers’ consumption behaviour by applying the theory of planned behaviour. And finally, come up with points to effectuate voluntary emission compensation and to achieve a shared responsibility between companies and consumers which includes “common future” (Holden et al., 2017), “common sense” and “common action” (Scott & Davis, 2007, p. 104) that foster genuine, effective sustainability commitment rather than compliance (Senge, 2006).

1.5 Research Questions

• How do individual consumers perceive emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy?

• What is required from companies in order to implement emission compensation effectively from the individual consumers’ perspective?

1.6 Previous Literature

In the literature review, we will first present the central themes to our study including sustainability and emission compensation as a companies’ strategy, relevant actors in the process of emission compensation, and consumers and emission compensation. The theoretical framework is then formed based on the literature in relation to companies and consumers in the process of emission compensation.

1.6.1 Sustainability & Emission Compensation as a Companies’ Sustainability Strategy

The literature on sustainable development has encountered a dynamic change from focusing primarily on global societal development to be a relevant concept “at the meso level of corporations and inter-organizational collaboration” (Beckmann, Hielscher & Pies, 2014, p. 19). Hence, during the past two decades the companies role as organisations and corporate actors has pronounced; and now “a key issue for sustainable development is the integration of different actions and sectors, taking a holistic view and overcoming barriers between disciplines” (Giddings, et al., 2002, p. 192). Thus, integrative approaches and acknowledging the impact of external environment as theoretical framework have gained attention in the process of developing companies from a holistic perspective (Giddings et al., 2002; Senge, 2006; Scott & Davis, 2007; Meadows, 2008). Scholars on sustainable development suggest two necessary ways of action from all actors in response to climate change: mitigation of emissions and adaptation to the inevitable changes (Sachs, 2015). The importance of companies to create mitigatory sustainability strategies has become a trendy narrative; and sustainability strategies and actions have been acknowledged to play important role in the process of developing companies more resilient to the changes caused by climate change (Sachs, 2015). However, sustainability strategies have been criticised for mainly being used for marketing purposes and referred as greenwashing (ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019) and not tackling the underlying problems of the system (Fleming & Jones, 2013). Similarly, emission compensation has been criticised as being a marketing tool which forward the problems to other actors, such as consumers (Dhanda & Murphy, 2011; Lovell et al., 2009). In addition, the way of communicating emission compensation to consumers have faced challenges as there are multiple ways to present the data: “Businesses are often given the option to use some sort of labelling scheme or logo to demonstrate that they have bought offsets or gone carbon neutral from that retailer” (Taiyab, 2006, p. 14). However, often, consumers do not have understanding, awareness or interest to evaluate these and later translate these into consumption behaviour (Eijgelaar, 2011).The literature on emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy has mainly focused on air travel industry as emission compensation has been one of their main approaches to mitigate emissions

7 (Taiyab, 2006; Gössling et al., 2007; Gössling et al., 2009; Mair, 2011; Lu & Shon, 2012). The results indicate that emission compensation has limited potential, it is an interesting approach for sustainability, but should not be adapted alone (Eijgelaar, 2011; Blasch, 2013). Mitigation hierarchy provides a hierarchical framework to build sustainability action: avoidance and minimization of emissions and restoration of natural environment should be given priority and compensatory activities should be considered the last measure to protect the environment (Lovell et al., 2009; Gonçalves et al., 2015; Cross Sector Biodiversity Initiative [CSBI], 2015). Hence, it is suggested that compensatory efforts should be created within the context of mitigation hierarchy which is contradictory to air travel industry’s standpoint.

A large part of the literature on emission compensation focus on the technical dimension of emission compensation and debate whether compensation is effective tool/mechanism towards sustainability (Hayes & Morrison-Saunders, 2007; Curran, Hellweg & Beck, 2014; May, et al., 2017), what is the impact of environmental offsets (Gordon, Langford, Todd, White, Mullerworth & Bekessy, 2011) or how much of the emission needs to be compensated in order to have a positive environmental outcome (Bull, Milner-Gulland, Suttle & Singh, 2014; Maseyk, Barea, Stephens, Possingham, Dutson & Maron, 2016). In the light of these challenges, studies have largely come to a conclusion that the current regulations, laws and supporting infrastructure do not support effective implementation of compensation (Martin et al., 2016; Lodhia et al., 2018). Thus, it is continuously contested whether compensatory mechanisms deliver the anticipated outcomes (May, et al., 2017) or are an effective mechanism in the first place to fight climate change (Curran et al., 2014). Hence, compensatory measures have received various opinions, both for and against.

1.6.2 Relevant Actors in the Process of Emission Compensation

Many of the articles consider multiple actors in the process of emission compensation and hence, focus on stakeholder theory and stakeholder analysis as a theoretical starting point (Martin et al., 2016; Lodhia et al., 2018; Gordon, Lockwood, Vanclay, Hanson & Schirmer, 2012). The starting point is based on the influence, effect and motivations of stakeholder pressures on companies to become more environmentally responsible and responsive companies (Bansal & Roth, 2000). In addition, Bansal and Roth (2000) articulate the open system organisation and build their argument on resource dependence theory which takes a standpoint that organisations are part of an larger environment and cannot be self-contained or self-sufficient, and therefore external stakeholders must be taken into account when building environmental strategies and later then effectively implemented. Dhanda and Murphy (2011) highlight the challenges of offset market in relation to stakeholders: “the markets for each of the types of carbon offsets are discontinuous and imperfect. Buyers can include individuals, nonprofit groups and corporate entities” (p. 39). In addition, many of the articles focus on stakeholders, mainly on legislators and regulators’, NGOs and other pressure groups’ and/or different company actors’ such as employees or managers perspective (Hayes & Morrison-Saunders, 2007), and what is their role in developing or implementing environmental strategies and emission compensation (Gordon et al., 2011). Hence, the role of consumers in the case of emission compensation has mainly stayed invisible. Moreover, the research lacks on clarity on the individual consumer’s understanding of emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy. In addition, there is no research consumers’ beliefs and perceptions on environmental compensation, even though they as a stakeholder group are directly linked to the sustainability strategy as consumers make the final decision of buying a service and/or product (Kassinis & Vafeas, 2006).

1.6.3 Consumers and Emission Compensation: Knowledge - Behaviour

The role of consumers in companies’ sustainable strategies in general has been researched actively during the past few decades as consumers are seen as one driver for companies to engage in sustainable solutions (Kuhn & Deetz, 2008; Palazzo et al., 2016). Sen and Bhattacharay (2001) articulate consumers’ role in companies’ sustainability initiatives. They highlight consumers’ personal support for sustainability and general beliefs on sustainability playing an important role as key moderators on consumers’ responses to sustainability. However, many studies note the discrepancy on individual

8 consumers behaviour in relation to their environmental concerns and values (Palazzo et al., 2016; ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019; Lovell et al., 2009; Nilsson & Martinsson, 2012).

Like aforesaid, currently, individual consumers operate merely on voluntary compensation scheme which results in that they need to actively have information and willingness to engage to emission compensation in order to make ‘an educated choice’ (Lovell et al., 2009). “For any transition towards sustainability to be successful, it is necessary to understand the knowledge, attitudes and practices” (Salas-Zapata, Ríos-Osorio & Cardona-Arias, 2018, p. 46). However, previous research highlights consumers’ knowledge of voluntary emission compensation is fairly limited and low (Gössling et al., 2009; Blasch, 2013). Yet, Blasch (2013) points out: “opportunities to offset own CO2 emissions from consumption may raise awareness among consumers about the adverse effects of certain consumption activities on the climate” (p. 21) and can function as a way to reach increased knowledge after a while. In addition, it is noted that there are multiple factors which influence on consumers power and behaviour to consume, which additionally influence on behaviour. Moreover, Sörqvist and Langeborg (2019) argue the complexity and challenges related to compensation strategies from the individual consumers psychological level and how values and practices do not always match in environmental terms. Furthermore, Lovell et al. (2009) have another point of emission compensation. They examine emission compensation as a way of sustaining consumption and lift up a point that compensation can be used as means to justify an unsustainable action. Yet, Gössling et al. (2009) note due to low credibility and low acceptance from individual consumers emission compensation is not a solution to sustainability and should not justify the means of avoiding an unsustainable action in the first place.

In relation to voluntary emission compensation many earlier studies have adapted the concept willingness to pay (WTP). WTP is frequently applied in studies related to voluntary emission compensation to show how willing individuals are to pay for the environmental harm they cause in the aviation industry (Blasch, 2013; Lu & Shon, 2012; Mair, 2011; Eijgelaar, 2011; Gössling et al., 2009). Studies on emission compensation and consumers have largely been explored with quantitative studies which map out consumers different views in general (Lu & Shon, 2012; Gössling et al., 2009). Results of these studies show similar patterns which can be concluded by Lu and Shon (2012): “the respondents’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the carbon-offset scheme and the awareness of their duty towards the environment determine their WTP the most” (p. 127).

Based on the above, our thesis, seeks to fill the gap in research: consumers’ perspective on emission compensation in general; specifically, exploring how the individual consumers perceive emission compensation and what is required from companies in order to implement emission compensation effectively from individual consumers’ perspective.

1.7 Delimitations

The research is limited to individual consumers perspective on emission compensation as companies’ voluntary sustainability strategy. Therefore, the companies view on the topic is limited and is not emphasised in the study. In addition, the focus is limited to emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy. All other emission compensations are excluded from the study. Moreover, like mentioned earlier the environmental impact and effectiveness of emission compensation is still contested. Our thesis does not evaluate emission compensation as a mechanism, instead the only focuses on how consumers’ view on it. Therefore, all technical aspects of compensation are excluded from the study.

Furthermore, the study was conducted in the Nordic context which limits the generalisability of the study. In addition, focus groups concentrated on everyday life case examples, mainly general food products, such as coffee and hamburgers. However, we acknowledge that the use of some other type of case examples, such as flights, might give different answers, especially in relation to WTP.

9

1.8 Structure

The introduction chapter gives an overview of voluntary emission compensation; why does it exist; how does it work and what are the roles of different actors in the process of emission compensation. Moreover, the introduction presents the research problem - complexity of emission compensation and the purpose of the study to explore consumers’ views on emission compensation. Lastly, the introduction includes previous literature which is divided into relevant themes. The second chapter lays the theoretical framework through which the analysis is conducted. The theories are divided to company level, where communication and signal theory are applied as a framework and to individual consumers level, where consumption behaviour is examined through theory of planned behaviour. The third chapter presents the method, data collection and the data processing methods. In addition, the limitations of the method and ethics of the research are discussed in this chapter. The fourth chapter includes the presentation of results from focus groups and continues with in-depth analysis of the results applied together with the theoretical framework. The results are divided by themes. The fifth chapter consists of discussion in relation to previous studies, theoretical framework and developing practical points to consider for implementing emission compensation as sustainability strategy. The last, sixth chapter concludes the thesis with concluding remarks and points out the direction for further research.

10

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework is based on voluntary emission compensation schemes. In the process of implementing emission compensation the roles and behaviour of companies and consumers are highlighted. Consumption is one of the key drivers of environmental violations (Palazzo et al., 2016). Therefore, “it is important not only change production conditions, but also to transform consumer habits and mindsets (Palazzo et al., 2016, p. 201). According to Bonnedahl (2012), companies play a significant role in taking responsibility for the environmental problems that exist in society today because of consumption and trade.

This chapter presents communication as an umbrella linking companies to individual consumers. Under this umbrella we have used signal theory which introduces a set of elements in communication in order to reach the individual consumers: awareness & knowledge, beliefs & values which in turn contribute to transforming consumption and effective implementation of emission compensation as a sustainability strategy. Therefore, we have looked into communication and applied signal theory to explain what is needed from companies’ side in order to implement emission compensation effectively into action. The individual consumer perspective is framed with the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019). Furthermore, the concept of willingness to pay is applied to explore the consumers readiness to take the responsibility of paying voluntary emission compensation. Lastly, we have created a combination of signal theory and theory of planned behaviour to connect companies to individual consumers.

2.1 Communication

In the light of the threats caused by climate change, organisations are required to collaborate and find common solutions together with other actors which can be implemented on large-scale (Giddings et al., 2002). Voluntary emission compensation schemes are an example which require that specific values are translated into strategies, especially into communication strategy, to engage and work together with individual consumers in the process of developing effective, sustainable outcomes (Holden et al., 2017). Genç (2017) articulates that communication is a fundamental accessory to build a common understanding of sustainable values and actions between different actors. Therefore, in order to achieve effective sustainable emission compensation, companies need to establish integrative stakeholder communication practices (Lodhia et al., 2018).

Firstly, companies should aim to transform their consumers’ habits by working with sustainable stakeholder communication as part of their sustainability strategy (Palazzo et al., 2016). Companies have the advantage to use their power by using marketing tools. Through the right kind of marketing, companies can influence their consumers’ values, mindsets and later their behaviour (Palazzo et al., 2016). However, engaging individual consumers and changing their consumption habits is a complex process and communication with different groups involves multiple dimensions which all need to support the effective implementation of sustainability strategy. According to Palazzo et al. (2016), to increase individual consumers’ sustainability consciousness, companies should provide opportunities for new practices to emerge. Here, these opportunities must reach the consumer’s knowledge and the information should be relatable.According to Moser (2010), sustainability communication has a role to inform and educate and engage and activate. Thus, in order to make emission compensation effective, companies are required to find ways to communicate their strategy to the individual consumers.

2.1.1 Signal Theory

In some occasions, the common understanding of information is lacking. The absence of understanding can make it difficult for external actors, such as consumers, to assess the company's environmental performance (Spence, 2002). Signaling theory by Spence (2002) can be applied to explain how companies should deliver information/message and how they can benefit from sending out signals. In

11 addition, signal theory includes the dimension how the individual consumers interpret information (Connelly, Certo, Ireland & Reutzel, 2011). Like mentioned earlier in the literature review, today’s companies are not self-sufficient (Bansal & Roth, 2000) and the complexity of sustainability (Sörqvist & Langeborg, 2019) implies that communication should circulate between senders (company) and receivers (individual consumer) and can be affected by external factors

.

Figure 1. The figure consists of a sender, receiver, and the signal itself and it explains the effectiveness with signals.

In the signalling model, the sender represents the company, which obtains the information in the first place, and then communicates the information and message forward. The signal itself includes the content of message/information (Figure 1). For sender, it is important to evaluate, which signals are important, and which are useless to send forward (Connelly et al., 2011). Receivers include the individual consumers who receive the signal. They can be considered outsiders, who lack the information: “these outsiders stand to gain (either directly or in a shared manner with the sender) from making decisions based on information obtained from these signals” (Connelly et al., 2011, p. 45). It is important to note that information mismatch works in two directions and therefore feedback in both ways is required. Receivers demand information about senders and their environmental strategy but also senders want information about receivers and how they receive the signal.

According to Connelly et al. (2011) there are two ways to effectuate signals. Firstly, a sender should include observation of how receiver notices the conveyed signal (message, information). In case of sustainability, companies should make sure that the lay audience receives the message. In addition, sender should consider the form and content of the signal and observe that the message includes adequately: “clear, sufficiently strong, and consistent signals that support the necessary changes” in consuming behaviour (Moser, 2010, p. 36). The process of effectuating the signal therefore includes feedback channel between the sender and receiver. Moreover, according to Wilby (2017), it is important that the sender’s actions and their signal they convey are in line with each other in the climate communication process in order to add credibility and trust from the consumer’s perspective. Thus, the ways of communication play important role from the receivers (individual consumer) perspective.

Second way of signalling is related to the cost. The cost factor indicates that some signals are in a better position for the receiver to absorb and accept (Connelly et al., 2011). The cost of a signal can associate with credibility of the signal/message/information, for example, the sender presenting different independent/external certifications or labels (Connelly et al., 2011; Utgård, 2018). The aspect of credibility in companies’ emission compensation strategies could provide multiple benefits through maintaining collaboration with different actors and giving an effect of desired behavioural performance and result. Researchers have examined the effects of trust in advancing behavioural and performance outcomes (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001): communication and sharing information play significant role in positive response from consumers. Therefore, in the case of emission compensation, if the individual consumers do not trust the effectivity of the effort, the cost of developing and communicating the sustainable benefits would be wasted (Shabbirhusain & Varshney, 2019). Taiyab (2006) notes that increasing the public awareness of climate change and emission compensation is a key to effectuate

12 emission compensation in the voluntary market. However, according to Eijgelaar (2011, p. 285), “raised awareness and changed attitudes do not often result in a change of behaviour”, which must be taken into account when seeking to influence consumers behaviour in order to reach “common action” (Scott & Davis, 2007) and “common future” (Holden et al., 2017).

2.2 Individual Consumer’s Awareness and Knowledge

Hannigan (2014) articulates reasons why certain environmental claims capture public attention and turn into behaviour. Firstly, uniqueness or distinctiveness of the issue are factors which refer to the extent people react to a problem distinct from others of a similar nature. Secondly, individuals should also have a sort of relevance to the problem which refers to the degree a particular environmental problem matters to the individual. Thirdly, it is all about stature/status, how individuals think and feel about a particular object, places, people or species under threat. Lastly, familiarity can affect the individual’s response, how well-known a particular problem is to an audience. Therefore, we suggest again companies are one of many actors who can inform and educate through their channels with labels, marketing efforts and information.

2.2.1 Theory of Planned Behaviour

The increasing concern of environmental threats has not yet caused large-scale changes in individuals consumption behaviour (Palazzo et al., 2016). Thus, attitudes and values have not translated into behaviour which would lead to effective implementation of emission compensation. One strategy is to change the logic of consumption by creating knowledge and awareness, and how products and services are then valued.

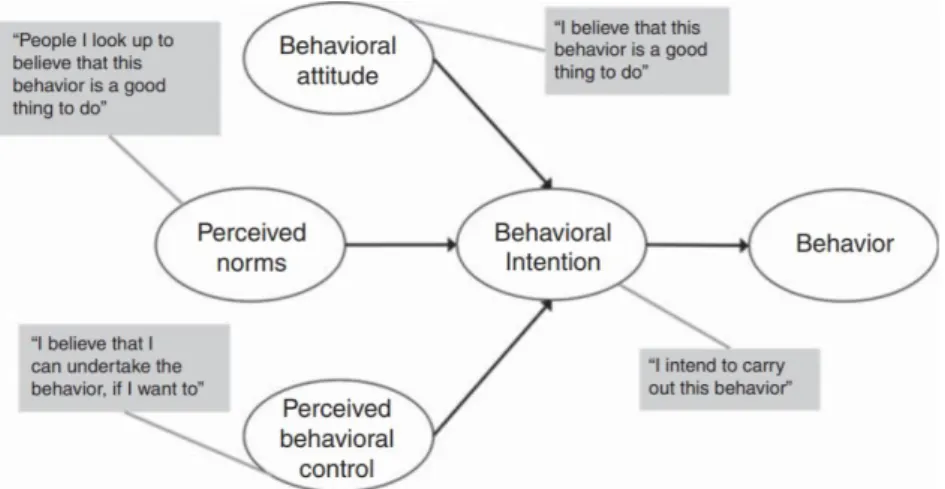

Theory of planned behaviour (TPB) by Ajzen’s (1991) can be applied for understanding and predicting why consumers behave as they do in certain situations. Moreover, the theory explains that knowledge of an individual’s intention can be the key to predict a certain behaviour (Nilsson & Martinsson, 2012). TPB suggests that “behaviour is a result of calculated decision that an individual takes on self-interest reasoning and after a thoughtful consideration of the motivational factors” (ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019, p. 89). According to TPB, the preconditions for individual consumers behaviour are established in three elements: behavioural attitude, perceived norms, and behavioural control. Firstly, the behavioural attitude proposes that there is a positive link between individual’s attitude/values and behaviour (Buhmann & Brønn, 2018). For example, if an individual has a positive attitude towards emission compensation, they are more likely to compensate. Secondly, the perceived norms include factors and actors from individual’s social environment which influence on behaviour (Buhmann & Brønn, 2018). For instance, if family and friends compensate/buy compensated products, the individual consumer is more likely to compensate as well. Thirdly, perceived behavioural control relates to individual’s belief of their own ability to undertake the behaviour (Buhmann & Brønn, 2018). If these elements are considered on sufficient level, individual consumer increases the level of predicted behavioural intention (Figure 2).

13 Figure 2. The theory of planned behaviour. Adapted from “Applying Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior to predict practitioners’ intentions to

measure and evaluate communication outcomes,” by Author A. Buhmann and P. S. Brønn, 2018, Corporate Communications: An International

Journal, 23(3).

According to Ajzen (1991) individual’s intention is the central factor to predict a given behaviour. “Intentions are assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence a behavior; they are indications of how hard people are willing to try, of how much of an effort they are planning to exert, in order to perform the behavior” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 181). Furthermore, individuals are likely to perform certain behaviour when they believe that it has an effect and they can adopt them successfully (Ajzen, 1991). However, it is important to notice that intention and behaviour can be affected by external circumstances and can depend on availability of resources and opportunities. “The more resources and opportunities people have the more control they believe they have, and the more likely they are to actually carry out the behavior” (Buhmann & Brønn, 2018, p. 380).

2.2.2 Willingness to Pay Emission Compensation

Palazzo et al. (2016) articulate companies’ role as key drivers for predicting and changing individual consumers behaviour by influencing the three elements of TPB. Yet, it is debatable what is the best possible strategy to proceed with emission compensation. Should companies include the cost of emission compensation automatically in the price of a product and not to leave the choice for the individual consumer? Or should companies give the opportunity for the consumers themselves to decide if they want to pay extra for emission compensation? In any case, it is crucial to examine how willing people are to change their attitudes and habits when it affects them economically. Therefore, a question arises: are individual consumers willing to pay for emission compensation?

The theoretical concept of willingness to pay (WTP) can be used to measure individual’s value on environment and/or willingness to pay for a change in quality, for example in environmental terms (Hanemann, 1991; Hanley, Shogren & White, 2013). According to Hanley et al. (2013) WTP is based on rationality. Individuals would not be willing to give up something for a change if it has no value to them. People need to receive value (benefit) from a change in order to be willing to pay. Moreover, WTP takes into account the economic factors: income and specific life situations (Hanley et al., 2013). Therefore, the economic value performs a crucial role when individuals make consuming decisions. WTP counts in that differences in preferences and values influence in people with similar income rates. Some can be willing to pay different amounts for the same change in environmental quality. However, Hanley et al. (2013) state that people tend to overestimate their willingness to pay. Thus, it is important to consider this in the analysis of the results.

2.3 Linking Companies with Consumers’ Consumption Behaviour

Based on the theories above, we have developed an integrated model which connects the role of the company into the individual consumer’s consuming behaviour. The model is based on the combination

14 of signal theory and theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3). The model aims to explain the important points where a company can shape an individual consumer’s consumption behaviour towards effective implementation of emission compensation in order to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Figure 3. A model of a combination between Signal Theory and The Planned behaviour Theory.

Companies have the possibility to influence individual consumers behaviour by communicating and working together with them. The feedback loop provides a channel through which companies and consumers can learn from each other. In order to change behaviour, companies should aim to change individual consumers’ attitudes positive towards sustainable outcomes. Moreover, companies can increase the meaning of perceived norms in the social environment by encouraging more and more people to choose more sustainable options. In addition, companies should provide opportunities for individual consumers to understand the consequences and impact of one’s consumption, and how to control these effects.

15

3. Research Design

In order to fulfil the purpose of the research; exploring how consumers perceive emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy and understanding how companies can effectuate emission compensation from consumers perspective, we have conducted a qualitative study with focus group method.

Emission compensation is complex and fairly unknown concept to the general public (Gössling et al., 2009; Eijgelaar, 2011). Therefore, the research was primarily conducted from the individual consumer perspective in order to understand how their perspective is linked to implementing emission compensation effectively as companies’ sustainability strategy. Salas-Zapata et al. (2018) note in their study: “to understand and/or promote the transition in a particular group of people, it would be necessary to examine at least three aspects: knowledge or beliefs, value systems and actions that, hypothetically, should be consistent with such belief and valuation schemes” (p. 46). Respectively, we chose to investigate the individual consumers’ knowledge and beliefs on climate change and emission compensation and how they value these, how does these influence in and have translated into their consumption behaviour. In addition, the individual consumers were asked what it require from companies and what is the role of communication in order to implement emission compensation in practice.

3.1 Data Collection

The thesis method consists of the combination of focus groups and case examples. Case study examples were used to link the concept of emission compensation to relatable and familiar everyday life products. This gave the opportunity for participants to discuss on objects which were familiar to everyone. Within social sciences a case study/case example is a common method to examine concepts and theories in real life situations (Shuttleworth, 2008). The case examples were collected from based on the researchers’ field observations, companies’ websites and reports and additional available communication channels. The focus group interviews were semi-structured and consisted of three parts. Semi-structured structure allowed each group to have their own discussion based on their experiences. However, the structure was kept similar in all focus groups which generated comparable results. Therefore, the focus group discussions started always with the moderator (us as researchers) delivering questions. All focus groups were recorded with a recording device with participants permission.

The first part of the interview consisted of questions to find out the background of the participants in

relation to climate change. This part investigated individuals own consuming behaviour and what are the basic underlying factors for the consuming choices they make. The second part focused solely on emission compensation. The first question of second part included a question whether the participants are familiar with the concept of emission compensation and what are their general thoughts on the topic. After this, the moderators gave their explanation of emission compensation and case examples. Following this, the interview continued with questions related to responsibility, credibility and trust, and data and communication in relation to emission compensation. The third part focused on consumers’ views on how effective emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy is and whether they consider it as a confusing concept. In the end, the participants were free to discuss any additional points they had (See full structure in Appendix I).

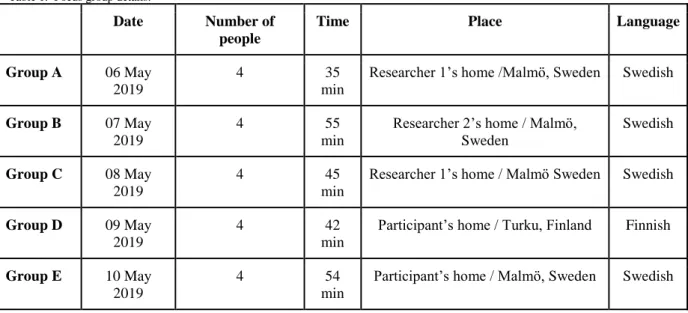

The research was conducted with five focus groups which all had four participants. Altogether, twenty people took part into the study. The participants were pre-selected and grouped randomly based on their interest and availability. All participants were considered individual consumers on the same level. In other words, the only prerequisite for participation was that participants have their own economy and they make their own consuming choices. The length of the focus group interviews varied between 35-55 minutes. The research was conducted in two Nordic Countries, namely in Finland and Sweden, which set the context to the discussion. The focus groups were held in participants’ native language, Finnish and Swedish, in order to obtain the most natural responses (Table 1).

16

Table 1. Focus group details.

Date Number of

people

Time Place Language

Group A 06 May

2019

4 35

min

Researcher 1’s home /Malmö, Sweden Swedish

Group B 07 May

2019

4 55

min

Researcher 2’s home / Malmö, Sweden Swedish Group C 08 May 2019 4 45 min

Researcher 1’s home / Malmö Sweden Swedish

Group D 09 May

2019

4 42

min

Participant’s home / Turku, Finland Finnish

Group E 10 May

2019

4 54

min

Participant’s home / Malmö, Sweden Swedish

3.1.1 Focus Group

The focus group method was selected based on the nature of this method. Focus groups are referred as group interviews which promote active group discussion in a natural conversation environment. The method actively encourages the participants to freely interact, express their beliefs and perceptions and influence each other (Silverman, 2014). “The participant is seen as coming to the focus group with fundamental orientations and ideas (held truths) that may be better elaborated through interaction with others” (Silverman, 2014, p. 302). In addition, listening to and observing the interviews can reveal more true fact on attitudes, beliefs on certain topic and how people act in certain situations (6 & Bellamy, 2012). The strength of this type of method is that it can reveal the actual knowledge, values and behaviour of participants as it is noted in many studies that “there is a discrepancy between consumer’s espoused concern towards the environment and their purchase of environment-friendly products” (ShabbirHusain & Varshney, 2019, p. 84). Furthermore, the aim is not to reach consensus in the issues that are discussed; instead, the aim is to reveal a variety of perspectives and experiences (Hennink, 2014). This kind of research method can give an interactive discussion where wide variety of data can be generated, which leads to a different type of data not accessible through individual interviews (Hennink, 2014). Focus groups are used when the researchers are interested in how people react, for example, to each other's opinions and of getting a picture of the interaction that takes place in the group. The method makes it possible for the researcher to create an understanding of why people think and act as they do. Normally, in an individual interview, the participant answers a question that concerns his/her opinion; focus group instead, generates the opportunity for the participants to explore each other's opinions (Bryman, 2011). During the focus groups, a person can respond in a certain way, but when she or he hears what the others have to say, the answer can be modified and expanded. The person in question can also agree with someone who he or she would not have thought of until hearing other's perceptions: this provides opportunities for a good foundation for several and different opinions on a particular issue (Bryman, 2011).

Therefore, by using focus group method we were able to get a variety of perspectives directly from the participants themselves on our research topic and gain more understanding of the issue from their perspective.

17

3.2 Data Analysis

The data collected from focus groups was recorded and later transcribed. Subsequently, the data was coded with themes in accordance with the theoretical framework and focus group structure. According to Hjerm, Lindgren and Nilsson (2014), qualitative analysis of the data is structured first by coding to find out the themes and then organised in thematic way and summarized together with the theoretical framework. In our study, the themes were related to individual consumer level, and how consumers side is met by the companies’ level in case of emission compensation. Therefore, in the analysis, the following themes will be analysed: Individual Environmental Knowledge and Behaviour, Emission Compensation as a Sustainability Strategy Responsibility, Credibility and Communication, Effectiveness and the Outcomes of Compensation.

3.3 Delimitations of Method

The focus group method limitations are related to size of the sample and the nature of the method. Focus group as a method does not present a large sample of the population and therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the large public. However, the method has the power to give in-depth answers from the participants and therefore, we have accepted the limitation of the given method. In addition, the focus group method might limit and suppress certain viewpoints in the discussion because of the group dynamics (Silverman, 2014). However, in these cases, the importance of moderator observing the situation can help to keep the discussion on track and not lost the meaning of the study. Furthermore, something that can affect the discussions is social desirability, which according to Nilsson and Martinsson (2012) means the participants respond in a way that they believe can be perceived as positive by others and will ignore other relevant opinions that may have been useful to our study. However, the moderators tried to avoid this by providing as relaxed and natural discussion situation as possible.

3.4 Quality and Ethics

It is important to notice that there are not absolute measurements and units for measuring individual consumers beliefs and perceptions nor their behaviour. Therefore, the meaning of examples and the discussion might vary from group to group.

According to Silverman (2014), reliability refers to the independent of bias which might affect the results. In order to ensure the quality of the focus group interviews, the moderators did not take any part to the discussions; instead, moderators took the role to ensure participants had the freedom to talk freely in a comfortable environment. In addition, the schedule of the questions was carefully formed in order not to lead the answers of the participants. All focus groups were asked the same questions according to the interview guide made by the researchers. However, in some groups, the topic of emission compensation was so unknown that the moderators were forced to give extra examples and explanations in order to get the conversation going. This might have affected to the thought process of some participants. The transparency of method and the process of data collection aim to generate credible results and illustrate the process as whole for the readers.

18

4. Analysis

The analysis focuses on emission compensation from consumers perspective and how they see emission compensation as companies’ sustainability strategy. Emission compensation as a voluntary sustainability strategy has gained various opinions for and against depending how it is implemented. Voluntary emission compensation is companies’ specific sustainability strategy which aims to neutralise the emitted emissions and/or compensate the ecological losses. Companies’ role in this process is to facilitate the compensatory mechanism for individual consumers. Individual consumers’ role on the other hand is to buy a product or pay extra fee for compensation in order to implement emission compensation in practice. In other words, emission compensation is implemented through consumption (Lovell et al., 2009). However, the process of implementing emission compensation is complex and there are various ways of calculating the emissions emitted. Lastly, in general individual consumers are unfamiliar with the concept and have limited knowledge on the policy (Gössling et al., 2009; Eijgelaar, 2011).

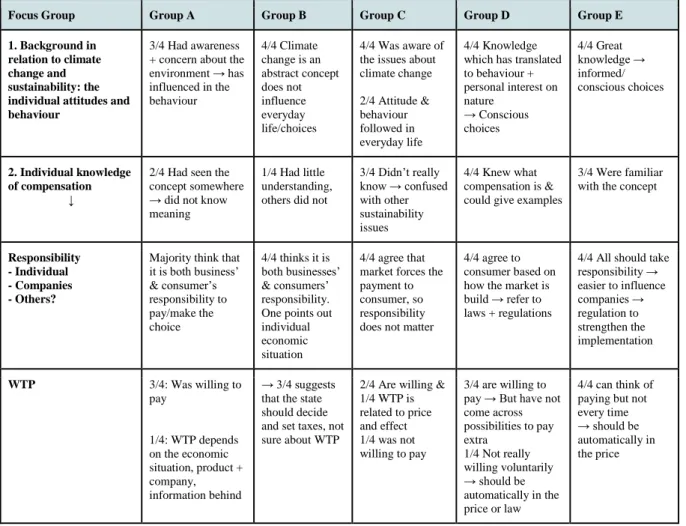

4.1 Thematic Analysis of Results

Following section presents a summary of the different views of focus groups in general (Table 2) followed by a thematic division and analysis of the results. The first theme sets the foundation by showing the individual knowledge and behaviour in relation to climate change. The next themes build up to the general knowledge and examine emission compensation specifically. Namely, what is the role of companies in emission compensation and how do the participants see companies’ position in this strategy. Secondly, who has the responsibility when it comes to emission compensation. Thirdly, the consumers evaluation of the strategy: how companies have communicated the strategy and whether it is credible or not. And lastly, the consumers evaluation of the effectiveness of voluntary emission compensation as company’s sustainability strategy.

Table 2. Comparison with answers and observation for the five focus groups.

Focus Group Group A Group B Group C Group D Group E

1. Background in relation to climate change and sustainability: the individual attitudes and behaviour

3/4 Had awareness + concern about the environment → has influenced in the behaviour 4/4 Climate change is an abstract concept does not influence everyday life/choices 4/4 Was aware of the issues about climate change 2/4 Attitude & behaviour followed in everyday life 4/4 Knowledge which has translated to behaviour + personal interest on nature → Conscious choices 4/4 Great knowledge → informed/ conscious choices 2. Individual knowledge of compensation ↓

2/4 Had seen the concept somewhere → did not know meaning

1/4 Had little understanding, others did not

3/4 Didn’t really know → confused with other sustainability issues 4/4 Knew what compensation is & could give examples

3/4 Were familiar with the concept

Responsibility - Individual - Companies - Others?

Majority think that it is both business’ & consumer’s responsibility to pay/make the choice 4/4 thinks it is both businesses’ & consumers’ responsibility. One points out individual economic situation

4/4 agree that market forces the payment to consumer, so responsibility does not matter

4/4 agree to consumer based on how the market is build → refer to laws + regulations

4/4 All should take responsibility → easier to influence companies → regulation to strengthen the implementation WTP 3/4: Was willing to pay 1/4: WTP depends on the economic situation, product + company, information behind → 3/4 suggests that the state should decide and set taxes, not sure about WTP

2/4 Are willing & 1/4 WTP is related to price and effect 1/4 was not willing to pay 3/4 are willing to pay → But have not come across possibilities to pay extra 1/4 Not really willing voluntarily → should be automatically in the price or law 4/4 can think of paying but not every time → should be automatically in the price