The management of governmental policies for a

gender-equal society of power distribution:

The case of the Swedish Police Authority

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business & Economics - Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ETCS

PROGRAM OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHORS: Daniela Jonsson & Josephine Larsson TUTOR: Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude and appreciation towards several individuals who contributed to the finalization of this thesis.

Firstly, we would like to thank all participants who contributed to the findings and thus made it possible for this thesis to be carried out.

Secondly, we would like to acknowledge the individuals of our seminar group for valuable comments and feedback throughout the thesis’ development.

Finally, we would like to express great gratitude to our supervisor Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg for her engagement, and her contributions of constructive comments and feedback throughout the

process and completion of this thesis.

Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping May 2020

Master thesis in Business & Economics - Management

Title: The Management of Governmental Policies for a Gender-Equal Society of Power Distribution: The Case of the Swedish Police Authority.

Authors: Daniela Jonsson & Josephine Larsson Tutor: Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg

Key terms: Organizational management, Governmental policies, Swedish police authority, Women leaders, Organizational culture, Gender equality.

___________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

The Swedish police authority is an extended arm of the Swedish government. The government implements governmental policies for its authorities, aiming at sustaining and improving the safety and wellbeing of society. In Sweden, one of the main policy safeguards is gender equality, which has been the focus of this study. It builds upon a well-established regulatory system for the representation of women in leading positions and argues for the benefits associated with tackling certain equality challenges.

Up until now, most of the scholarly contributions on organization management, in relation to governmental policy, have dealt with leadership power and its efficiency, rather than equality. This study showed that the contemporary application of governmental policy has an impact on organizational culture. Through policy, gender equality could be increased as it encompasses potential benefits associated with leadership and power distribution. The study showed that this is also the case for the police authorities in Sweden in which applying gender policies has implications for managers' decisions when these are used to make the organizational leadership structures more equal. The application of policies to allow gender equality has also implications for employees regarding their work performances when advancing up in hierarchies.

Table of content

1. Introduction 5

1.1 Background 6

1.1.1 The Swedish model 8

1.1.2 Governmental policies 9

1.2 Problem statement 10

1.3. Purpose 12

1.4. Research question(s) 12

1.5 Perspective and delimitation 12

1.6. Definitions 13

2. Frame of reference 15

2.1 The management of policies towards gender equality 15

2.1.1 Gender mainstreaming 16

2.1.2 Biological gender differences 16

2.1.3 Social gender constructs & stereotypes 17

2.2 Importance of female leaders 19

2.3 Glass ceiling / brass ceiling 20

2.4 The leadership culture within the Swedish police 21

2.4.1 Organizational culture 22

2.4.2 Police culture 23

2.4.3 Culture examination by the Swedish police authority 26

2.5 Actions taken for gender equality in the Swedish police authority 27

2.6 Power motivation 29

2.6.1 Power motivation for working within the private vs public sector 30

2.6.2 Power motivation for the police profession 30

2.6.3 Power motivation for becoming a leader 30

2.7 Research model summary 31

3. Research methodology 32

3.1. Research philosophy 33

3.2. Research method 33

3.3. Data collection and sampling 33

3.3.1 Secondary data 33

3.3.2 Primary data 34

3.4. Data analysis 35

3.5 Quality & trustworthiness 35

3.6 Research ethics 36

4. Findings 39

4.1 Governmental policies 40

4.2. Management processes 42

4.2.1. Profession motivation and power motivation 42

4.2.2. Management and process of acquiring more women in leadership positions 43

4.3. Police leadership culture 45

4.3.1 Perception of the police culture and cultural change 45

4.4. Social constructs & stereotypes 47

4.4.1 The ideal leader 47

4.4.2 Resistance, glass ceiling and respect 47

5. Analysis 50

5.1. Interpretation 50

5.1.1 Governmental policies 51

5.1.2 Management processes 53

5.1.3 Police leadership culture 55

5.1.4 Social constructs & stereotypes 58

6. Conclusion and discussion 61

6.1 Implications 64

6.1.1 Theoretical implications 64

6.1.2 Managerial implications 65

6.1.3 Ethical implications 65

6.2 Limitations 67

6.3 Suggestion for future research 67

7. References 69 7.1 Articles 69 7.2 Webpages 74 7.3 Books 76 7.4 Additional Documents 78 8. Appendices 79 8.1 Interview questions 79

1. Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides an introduction to the research topic by describing the background as a broader context of the topic. Followed by background, the problem of the topic will be discussed. Furthermore, the purpose of this study will be defined and clarified, together with the study’s research questions. Finally, key definitions will be described.

___________________________________________________________________________

Management is an important function for organizations, but also tends to represent a substantial lack of female representation in leadership positions. Leadership has the potential to generate a more gender-equal society. The low proportion of females in leadership positions has during the last years leading up to public debates worldwide, including Nordic countries like Sweden (Sanandaji, 2016; Mandel, 2012). Research shows that there is an underrepresentation of women in higher hierarchy positions (Fägerlind, 2009; Acker, 2006). Sweden is a nation considered to be widely known as a gender-equal society and having policies facilitating this important and complex topic. According to the Gender Equality Index, Sweden had by the year 2019 a score of 83.6 out of 100 points, which indicates that Sweden is the EU leading country in the goal to even out gender inequalities. Even though progress has been made and the number has increased during the last decades (EIGE, 2019), research has found that gender-equal nations are actually hindering women’s progress in climbing the corporate ladder (Mac Giolla & Kajonius, 2019; Manden, 2012). Recently, Sanandaji (2016), presented “The Nordic Gender Equality Paradox”, describing how governmental policies together creates a glass ceiling in Nordic countries. Moreover, the Swedish government has the power to develop, implement, and change these policies, as the government is the extended arm of society, which represents society in which we live (Regeringskansliet, 2017). Furthermore, since Sweden is considered to represent gender equality, governmental policies and practical actions for gender equality should be in line with this representation. Sweden is considered as an equal society, however, is it really equal in practice?

1.1 Background

Gender can be defined in two different ways, by biological features or social definitions. No matter what perspective one chooses to see the concept from, gender is a categorization or label of a group, where the different classifications have something in common, such as men and women (Posey, 2016). According to research, several differences in both biological and social characteristics have been detected between the genders. The variations have proved to affect and influence decision-making processes, behavioral acts (Järvinen, 1996) as well as the physical body strength (Miller, McDougall, Tarnopolsky, & Sale, 1993). Stereotyped images separating the genders are the main reason for gender discrimination and the unequal treatment of women versus men (Cuddy et al., 2015). Furthermore, to achieve a more equalized society, one must highlight the gender similarities rather than the differences (Hyde, 2005).

Several welfare state governments are known for promoting a more gender-equal society by implementing governmental policies (Mandel & Semonoyov, 2006). A government implementing a principle or course of action in the purpose to guide better decisions to enhance society is called a welfare policy (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d). These policies, among other things, aim to enhance the development of women’s career advancement and benefit women in reaching leadership positions (Mandel & Semonoyov, 2006). However, Mandel and Semonoyov (2006) found indications that the welfare state’s attempts of equality policies might instead be converted into feeding the glass ceiling. This is supported by Sanandaji (2016), presenting The Nordic Glass Ceiling, describing how governmental policies create a glass ceiling in Nordic nations.

Moreover, to generally increase the proportion of women in organizations is called gender

mainstreaming. This phenomenon is received with varying attitudes from the organization as

well as single individuals. For the process to be carried out over the principal and in a satisfactory way to reach the desired result, it requires an understanding of why the inclusion of women is important (Freidenvall & Ramberg, 2019). Research investigating the impact of female inclusion in leading positions have proven that female leaders acquire a higher level of trust among employees (Cunliffe & Eriksen, 2011), higher levels of employee engagement (Ghani et al., 2018) as well as positive effects in times of crisis (Heidensohn, 1992). Thus, a larger proportion of women leaders result in an overall positive development for the organization (Ghani et al., 2018). Despite the positive outcomes proven to be an effect of

female leaders, there is no secret that women are underrepresented higher up in hierarchy positions. One theory that captures the problematics for the underrepresentation is the glass

ceiling, which creates an invisible barrier and keeping women from reaching top positions due

to the social structure by stereotyping genders. For the glass ceiling to be shattered, the social structure must be changed and opportunities must be provided so that women can show what they are capable of (Broadbridge & Weyer, 2007). According to FN’s general explanation of human rights, all men and women are entitled to equal rights and freedom (FN, 2016). The reason for laying focus on gender equality in distribution of power is because it lies a value and importance of including women in decision making since they also represent the society in which we live in and thus have the right to be equally included.

Sweden is one of the world’s most gender-equal countries seen to the population size as well as the employment rate between genders (Regeringen, 2019; EIGE, 2019). Even though the country is gender-equal on paper, some aspects within the Swedish police sector have displayed the opposite image. According to previous studies executed by Haake (2018), both Swedish policewomen and policemen have announced that the different genders are treated unequally within the sector. The police sector is said to have a macho culture built around it and that the culture is characterized by universal masculine features (Skolnick, 2008), which may be an explanation for the underrepresentation of women in the police sector and especially in leading positions (Österlind and Haake, 2010). Masculine ideals form police work environments, which significantly affect and form the corporate culture and individuals’ attitudes (Loftus, 2008; Kurtz, 2008). According to Muftic and Collins (2014), supported by Chu and Tsau (2014), it still exists prejudiced perceptions within the police that women are not as suited as police leaders as men are. The police culture may be an explanation for these stereotypes and the reason for the underrepresentation of female police leaders and other gender inequalities (Kurtz & Upton, 2018).

The Swedish police sector has no specific written goal for the proportion of women in leadership positions (Polismyndigheten, 2020). However, according to the police annual report (Polismyndigheten, 2020), there is a desire to increase the number of female leaders within the authority, especially on the local level. This indicates a lack of clarity in policy information, in theory, hence part of the focus for this study will be to fill the gap of the nonexistent goal.

Since the police should be a role model for how society should behave and be displayed, the unequal conditions in culture and leadership positions within the Swedish police sector are unacceptable. This is the reason why we choose to investigate the police sector in the context of Sweden. Furthermore, we will be taking the power motives for working as a leader within the police sector into consideration. This is an important aspect to include, to gain an understanding of why individuals strive towards acquiring power and if there is a connection between power motives and the police culture.

We have discovered a lack of studies examining the relationship between theories (regulations and policies) stating what the Swedish police should strive towards achieving gender equality, and how this is enforced in practice by the Swedish police. Furthermore, there is a need to raise the female perspective to gain an understanding of how the police organizational culture affects females in achieving and performing leadership occupations. The findings from this case study are intended to provide both researchers and practitioners a wider understanding of key perceptions and barrier factors such as the glass ceiling phenomenon and corporate culture through the example of the Swedish police authority. Thus, this study can contribute with guidance for improving the gender-equality of nations, and, in turn, allowing women career advancement effectiveness.

To gain an understanding of the current guidelines managing a gender-equal power distribution within the public sector, it is important to know the basic principles governing gender equality in state authorities. Two main documents are contributing to guidelines that the Swedish police authority is entitled to follow when it comes to evening out the gender gap within the sector. These are the Swedish model and governmental policies.

1.1.1 The Swedish model

During the 1930s the modern edition of the Swedish model was emerged, which purpose was to shape the society in which we live. The Swedish model consists of several cornerstones that together form the Swedish society. The model aims to create a secure future for the nation, but such a model requires constant development in order to be adopted for the needs and changes that the society constantly stands in front of. These basic principles consist of three fundamental parts, namely, An organized labor market, general welfare, and responsible financial

and negotiations, the interaction between various parties in the labor market, that the taxes and fees paid by the nation’s population go to elderly care, child care, health care, and social insurance. Furthermore, the tax funds must be placed in such a way to generate a society that creates equal conditions for health, working life, and education. Finally, the Swedish model includes an economy and policy that together promote stability through growth and prosperity in society, which stabilizes cyclical fluctuations through monetary and fiscal policy as well as even out the income differences between the poor and rich population. The above-stated constitutes “the Swedish society” (Kommunal, n.d).

The second mentioned pillar, which is aimed at the equal society, is of great importance for this study and will illuminate a significant part of our research area. According to the Swedish model, women and men should live under equal conditions, meaning that the opportunities for education, economic benefits as well as opportunities to be in a power position should be no different for women than for men (Regeringskansliet, 2017). The agreement states that equality between women and men should permeate all activities within organizations. In the long run, this initiative contributes to long-term opportunities to increase the labor supply in the labor market. But the Swedish labor market is gender-segregated. In some professions, only men work, in others only women. By integrating the gender equality perspective into all organizational decisions and planning processes will generate gender equality. The law of separate taxation for women and men, as well as better childcare, has resulted in becoming more profitable for women to be part of the workforce (TCO, n.d).

The Swedish model has been adjusted to suit the demands in society by switching out older components for newer tools and modern measures. The biggest adjustment was carried out during the ’90s due to general changes in welfare and politics. But the core concepts were preserved, such as social policy, labor market policy, state paternalism, and equality commitments (Czech, 2015). Today the most important elements of the model for effective social politics, which contribute to an efficient economy and increased welfare, according to Czech (2015) are honesty, civic integrity, and work obligation.

1.1.2 Governmental policies

The Swedish police is a governmental authority, which lies under the department of justice. An authority is an extended arm of the government and the government is, therefore, the highest

and leading power who regulates, by an annual regulatory letter, how the police authority should operate in the work and what goals to strive towards (Regeringskansliet, 2017). The regulatory letter states that for achieving the government’s objectives of the gender equality policy, every authority, including the police authority, has an obligation to act according to the policy of gender mainstreaming (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2018). The Swedish government has different equality policy goals, in which the first one is particularly relevant for this thesis. That goal is to achieve an even distribution of influence and power in society, where women and men have the same opportunities and rights to achieve power in shaping society. The policy further argues that obstacles such as gender stereotypes and other social aspects should not prevent females from shaping their conditions to decision-making and power. An even distribution of influence and power between men and women in society is not a guarantee that

real power is evenly distributed. However, it is a crucial condition for the exercise of power to

develop into a fair and equal direction (Jämställdhetsmyndigheten, 2017).

According to the Swedish Parliament, under the heading “the position of women in society” (Sveriges Riksdag, 1992), Cederschiöld describes the practical execution of how gender equality should be practiced. This means that each individual must be respected and judged on the characteristics they possess. Whether it concerns a man or a woman. She further points out that the fight against a more equal society also represents the fight for the recognition of individual differences. The foundation is that it should not matter if it concerns a man or a woman, but instead places an assessment of who is best suited and possess the right competence. On the other hand, Cederschiöld additionally explains that there must be a change in the minds, conditions, and values to avoid women from being bypassed or hindered to further develop the labor market, due to their gender (Riksdagen, 1992).

1.2 Problem statement

The underrepresentation of females in leading positions within the police profession in Sweden is considered a problem since it represents an inequality, which goes against the main pillars of the Swedish model (Regeringskansliet, 2017) as well as the statement in the regulatory letter, i.e. governmental policy, stating that men and women should have an equal amount of power in organizations and society as a whole (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2018). The Swedish national police have stated that a larger proportion of females in leadership positions within the sector

are a prerequisite for the development of the continuing equality work that has started. However, clear and concrete numerical goals are not mentioned (Polismyndigheten, 2020) resulting in an unclear indication of what gender equality infer according to the Swedish police. Moreover, a lack of previous research within the field of gender equality, in connection to governmental policies, and in the context of Sweden has limited the understanding of gender inequalities. This research gap is strongly impacting developments in for instance policy regulations, measurement goals, and practical commitments, and thus, indicating a need for further investigation within the area. Therefore, the underrepresentation of female leaders within the Swedish police authority is considered relevant as a research problem.

Throughout time, socially constructed gender differences have existed between men and women. Still, this gender inequality label is present, in private life as well as within organizations (Acker, 2006). Women are often a minority in leadership positions, in private as well as public sectors (Fägerlind, 2009). Job titles often have a prejudice of being either masculine or feminine and thus being suitable for a specific gender (Alvesson & Due Billing, 1999). Being a police officer is a profession that has long been characterized by being masculine and thus best suitable for the male gender. Even though the number of women within the police has increased significantly, there are still areas where women’s presence is small, especially in the higher levels of the organizational hierarchy. The fact that female leaders are underrepresented in the Swedish police authority can not be neglected (Österlind & Haake 2010; Van der Lippe, Grauman & Sevenhuijsen 2004). According to Edström and Jacobsson (2015), findings indicate that within the police and military professions in Sweden, there is a clear majority of men since they stand for 92% of the category. The inequalities within male-dominated professions have reduced in recent years but is still not at a respectable level. This is based on the remaining preconceived notions describing "female" vs. "male" characteristics (Wikander 2007). Previous research has shown that the concepts of "female" and "male" are opposite notions, that femininity is seen as a complement to masculinity and that leadership traits are linked to male behavior. Consequently, the "female" way of leadership has not been considered as important or accustomed to being potential leadership traits (Wahl, 2003).

1.3. Purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine the management of gender equality in public sector organizations. Explicitly, the efficiency of governmental policies to achieve a more gender-equal organizational leadership culture in the Swedish police authority.

1.4. Research question(s)

To fulfill the purpose of this study, three research questions are presented;

RQ1. What are the challenges for the Swedish police to reduce the leadership gender gap when

dealing with gender equality?

RQ2. In what ways can the management of governmental policies affect the Swedish police

leadership culture to greater engage women in achieving leadership positions?

RQ3. In what ways could current governmental policies improve to allow gender equality

power distribution?

1.5 Perspective and delimitation

The problem discussed in this thesis is studied from the perspective of female leaders within the Swedish police authority that participated in the study. Meaning, the findings will be built on the data gathered from the interviewees and their perspectives on the subject. Since this thesis will have its focus on policies connected to gender-equality and female leaders within the Swedish police sector, it might not be applicable in other contexts significantly different from Swedish culture and work ethics. The findings will be angled from the lens of women and therefore the findings might not capture the male perspective of the issue discussed. Furthermore, the case study will only investigate two different regions out of seven, namely, west (Storgöteborg) and east (Jönköping and Östergötland). Therefore, the conclusion might be different for other regions within the Swedish police authority.

1.6. Definitions

Since some of the key concepts used throughout the thesis are considered not regular to daily use, difficult to understand or require further clarification, we provide definitions for some of the concepts. Notice that not all keywords are included in this section.

Gender equality: refers to men and women having the same opportunities, rights, and

responsibilities concerning all areas of life (Jämställdsmyndigheten, 2018).

Governmental policy: a principle, rule, or course of action implemented by a governing body.

The aim of government policy is to guide decisions and actions better, culminating in positive outcomes that enhance the unit or community. It includes the justifications that things are to be done in a certain way and why (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d).

Macho culture: refers to an oppressive masculine culture, where the woman is inferior and

often overlooked by the man. Stereotypical female characteristics are diminished and seen as less effective and necessary (PBS, 2017).

Masculinity: refers to having the qualities or appearance which is by society associated with

male behavior. Such as a male voice, appearance, body structure, characteristics, etc.

Femininity is the opposite notion of masculinity. Both concepts are socially constructed (Berger, Wallis, & Watson, 2012).

Police sector/Police authority/Police department: the designation of the police sector, police authority, and Police department will be interchangeable throughout the thesis and refers to

the same signification.

Quotas: refer to special treatment which requires that part of the vacancies, for example in a

workplace, is reserved for a peculiar group. The term primarily refers to quotas based on characteristics such as gender, skin color, ethnicity, disability, or social class (Nationalencyklopedin, n.d.). However, in this study, quotas refer solely to gender.

Stereotype: refers to having a set idea about what a peculiar person, a group or something

is/should be like, especially an idea that is inaccurate (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). In this study, stereotypes associated with different genders will be discussed.

Women/female: the designation of women and females will be interchangeable throughout the

2. Frame of reference

___________________________________________________________________________ This chapter provides a frame of reference and theoretical background on the topics relevant to the research. It will guide both the methodology and analysis of the following empirical study. Moreover, the frame of reference has been separated into the main themes arising from the existing academic research and literature of theories and previous studies.

___________________________________________________________________________

2.1 The management of policies towards gender equality

Since this study is in the context of Sweden, which is considered being a welfare state of high gender equality, it is essential to investigate the facilitating factors and barriers previously investigated in welfare states. A study conducted by Mandel and Semonoyov (2006) indicates that there is still extensive diversity in gender-equal welfare states between men and women in higher managerial and leadership positions, even though equality between the genders has for decades been anticipated as the right way to stimulate women in gaining higher positions. Welfare states are well enforced by governmental policies to enhance and develop females’ career advancement. On the other hand, Mandel and Semonoyov (2006) state that these activities are promoting females’ entrance into the labor market, rather than promoting entry into top leadership occupations. Research by Tanhua (2018), investigating gender equality in Nordic welfare societies, indicates that social norms, career mobility, and gender segregation strengthen cultural gender stereotypes and conceive inferior flexibility for women career advancement. In conclusion, welfare states’ attempts for promoting female career advancement may instead be converted to a factor of barrier creation which enhance the glass ceiling (Mandel & Semonoyov, 2006). Thus, welfare state policies may have an impact on women’s climb on the corporate ladder (Tanhua, 2018; Sanandaji, 2016; Mandel, 2012; Mandel & Semyonov, 2006).

Recently, Sanandaji (2016), presented “The Nordic Gender Equality Paradox”, describing how governmental policies creates a glass ceiling in Nordic countries. The paradox arises from the government initiating for gender equality by policy support. However, the combination of Nordic sector monopolies, family and welfare policies, ineffective gender quotas and tax policies reinforce the Nordic glass ceiling. Even though the Nordic countries, including Sweden, should be admired for their equality values and the positive development of enhancing

women’s careers, the policies in these welfare nations prevent women in career advancement (Sanandaji, 2016).

2.1.1 Gender mainstreaming

In research examining two Swedish cities, Eskilstuna and Jönköping, Freidenvall, and Ramberg (2019) investigated the problems encountered during the implementation of gender

mainstreaming (GM) in organizations, as part of the Swedish model. Gender mainstreaming is

a public policy, whose mission is to make sure that opportunities are equal for women and men, at all levels and fields. The implementation of GM in the municipalities has proven to be generally successful, but the results have not necessarily generated the expected or desired outcome. The problems that aroused during the process were due to a lack of understanding, capacity, and will for the implementation. Both municipalities believed that the problematics for the issue were not dependent on financial resources but instead gender equality is considered to occur during circumstances when a change in attitudes, as well as a stronger will for change, are present. Furthermore, Freidenvall and Ramberg (2019) state that one implication for GM to occur in organizations is due to that gender equality is most often opposed to other important aspects and perspectives, making GM less prioritized. Their research concludes that political policies lay the foundation for the integration of gender equality politics in society and organizations. However, the study shows that a lack of political will to some extent can be compensated by a solid system of governance (Freidenvall & Ramberg, 2019).

The problematics arising with gender mainstreaming in organizations is of major importance for this research. It is vital for the understanding of why resistance in changing the gender gap arises and why gender mainstreaming might not be a crucial and critical problem to resolve. Furthermore, the study allows management departments in organizations to change employee behaviors and implement suitable procedures to reduce the gender gap.

2.1.2 Biological gender differences

To acquire an understandable notion of the concept of gender and how it affects the decision making one uses biological and social differences. To gain an understanding of why women have lower requirements during the physical test to become a police officer, research is needed to explain the strength differences between the sexes. As for the gender differences in biological and physical activity measures, Miller et al. (1993) have conducted research in the

field. By examining the differences between the sexes concerning strength and muscle characteristics from participants with approximately the same body mass. Their findings indicated a correlation to older research, which states that strength and muscles in both the upper and lower body are different between the genders since men have proportionally larger muscles relative to body size. The difference in muscle dimension might be the explanation for men having a higher level of endurance than women usually have (Miller et al., 1993). This is further strengthened by Padmavathi, Bharathi, and Vaz (1999), where research was conducted within the field of gender differences in muscle strength and endurance. When reviewing the literature, one can conclude that there is a lack of previously conducted research developed within the field of body strength differences in gender. Thus, somewhat senior sources were used.

2.1.3 Social gender constructs & stereotypes

Moreover, humans are at an early age taught tasks and social constructs related to their biological gender (Börjesson, 1992). Järvinen (1996) further highlights that when it comes to social differences the society expects its citizens to act and behave according to their gender, otherwise one is deviant. Additional research shows that one can find a gender power hierarchy within life tasks and abilities, where the man is the superordinate and the woman is the subordinate (Hirdman, 2003). This stereotypical perception is the biggest contribution to why men and women are treated unequally, consciously, and unconsciously (Cuddy et al., 2015).

Further research indicates that social norms have given the consequence of women experiencing difficulties in acquiring leadership positions since they are not considered as attractive as men for higher positions. Decades of stereotyping have led to women not living under the same conditions and opportunities in the labor market (Engen et al., 2001). According to Hyde’s (2005) study The Gender Similarities Hypothesis, the attitude towards gender differences is harmful to women’s employment rights, and to get an equal society one needs to highlight the similarities instead of the differences.

The outdated image for women's role in society, claims that women should be inferior to men and are better suited in providing emotional support rather than being in a leading position. Female attributes are linked to the home environment, such as housekeeping or caregiving. In contrast, men are considered to have suitable characteristics for a leadership position, well-paid

jobs that are based on high education or are physically demanding, which in turn contributes to financial security (Deaux & Lewis, 1984). Today, the labor market has become significantly more gender-equal and it is unusual for Swedish organizations not to work towards a more equal workplace. Gender and background should be insignificant, everyone should be treated equally and judged based on their competences. Although workplaces are becoming increasingly equal, it is no secret that the majority of leading positions belong to men, both in the public and private sectors. Despite progress, there is still a long way in reaching the goal of equalizing leadership positions between genders (Bruzelis & Skärvad, 1995). For example, in June 2019, only 6.6% of the Fortune 500, the highest-grossing firms in the world, had women CEOs, which is a record high number (UN Women, 2019).

As more women have attained leading positions, great research efforts have been executed to explore differences between female and male leaders. According to Bruzelis and Skärvad (1995), leadership between the different genders is not considered to be of great differences. However, what is noticeable is the connection between female leaders and the style of collaboration. Morgan (1999) found stereotypical traits linked to female vs. male behavior. The research showed that the male stereotype is more likely to be logical, rational, aggressive, strategic, and more competitive, unlike females who possess stereotypical traits of being emotional, spontaneous, cooperative, and empathic. These stereotypes contribute to gender prejudice and biases. A preconceived image of what is female and male separates people into boxes and hence objective decisions can not be made impartially. By judging a person based on their gender might result in several types of prejudice. Women can be judged to be less competent and competitive than men, which in turn is not considered a leadership trait. This makes it more demanding for a woman to reach the same height in her career as a man (Hoffmann & Musch, 2019). Some feminist movements believe that the labor market consciously segments career opportunities to the benefit of men. Thereby men could reach more prestigious professions and positions within organizations (Morgan, 1999). In a study carried out by Hoffmann and Musch (2019) within the field of gender prejudice, they found that men have a higher tendency to have preconceived notions about women than vice versa and that women are more careful not to show their prejudice towards others.

2.2 Importance of female leaders

As this study aims to investigate the female underrepresentation in leadership positions, it is important to look into the aspects of why it is important to include women. Post, Latu, and Belkin (2019) investigated the relationship between female leaders and interpersonal emotion management (IEM). Hence, the capability of managing and understanding the emotions of others, and whether they have a link to female advantage in organizational crisis and trustworthiness towards employees and the organization. A stereotyped image of a female leader is that she possesses a relational leadership style, indicating to accomplish the set goal by having a close relationship with the team (Cunliffe & Eriksen, 2011). This specific leadership style tends to foster trust among the follower and leader. In their research, findings indicate that female leaders with relational capabilities have an advantage towards male leaders, which is consistent with earlier research, and have in some cases also been proved to be an advantage during crises (Post et al., 2019). In addition, female leaders have shown to promote peace to a greater extent than men do (Sykes, 2016). Moreover, in times of crisis, Heidensohn (1992) claims that within the police sector, they tend to put women leaders in the spotlight to show and generate a softer side of policing.

According to Eagly and Carli (2003), the disadvantage for female leaders lies in the judgmental and negative preconceived opinions, primarily in male-dominated or especially masculine roles, industries, or sectors. The dilemma that arises between a woman and the "masculine role" is counteracted by the fact that the woman must often prove to be highly competent and reassuring, but at the same time live up to what is considered "female behavior". This double standard makes it more difficult for women to reach higher in their careers since they already have a disadvantage from the start.

In addition, Regnö (2013) argues that the contradictory notions stating that females and leadership do not belong together render a double deficiency for women in a leading position. They are considered to either lack traits of being a good leader (too vague leadership traits) or that they are lacking in their charisma as a woman (too much of a boss). Hence, a woman is more strictly judged than a male leader to fit into its invisible "template" of how a leader should be and behave. Furthermore, Regnö (2013) explains that the reason for the low representation of women in leading positions today is due to the minority, which creates stress and performance anxiety for living up to the standards. In addition, some women choose not to

prioritize a career, as working conditions in male-dominated industries do not appear attractive enough.

Ghani et al. (2018) conducted research investigating the relationship between different leadership styles, namely transactional and transformational leadership, female leaders, and the engagement of the employees. After analyzing the results from 113 employees from Government Link Companies, working under female leaders, findings indicated a positive correlation linking the independent (female leadership; transformational, and transactional) and dependent (employee engagement) variables together. Furthermore, the research implies that the statement that a woman leader would be less effective than a male leader is false. The study concluded that a female leader using a transactional or transformational leadership style generates employees willing to work on themselves as well as raising their working morale, resulting in the positive development of the organization since female leaders tend to balance their career and responsibilities effectively. Furthermore, employees show great working ethics in the presence of a female leader (Ghani et al., 2018).

2.3 Glass ceiling / brass ceiling

The glass ceiling, or “brass ceiling” is an invisible barrier keeping women from reaching higher positions within the hierarchy of organizations, due to their gender. What separates the two titles, glass from brass is that the brass ceiling is focused on women operating within military and law enforcement (Iskra, 2007). Since this is a relatively new concept, there are limited studies made on the brass ceiling and no academic articles or journals to be found within this area. Therefore, the glass ceiling will be in focus.

According to Broadbridge and Weyer (2007), the glass ceiling is still present within organizations, keeping women from reaching top positions due to the social structure. The social system is built upon prejudiced beliefs that female leaders are less competent than male leaders, generating inequalities between genders. This demonstrates that gender biases are the foundation for the problematics and condition of the phenomenon called the glass ceiling. Furthermore, Broadbridge and Weyer (2007) argue that for the glass ceiling to be shattered the social structures have to be changed to give opportunities for women and providing the chance to use and develop their competencies, and additionally to scale down the power of male leaders

within the private as well as the public sector. But the question of how organizations, individuals, and society should organize the strategy for the changes has to be further investigated.

In research conducted by Albrecht, Björklund, and Vroman (2003) the question of whether a glass ceiling exists in Sweden is in focus. The research results show a strong tendency of the phenomenon being present within Swedish organizations. They detected a large gap in the wages and positions in the hierarchy between genders. The general gender gap in the Swedish society is relatively low, which makes the question of gender and wage equality in organizations exceedingly important. Statistics show that the glass ceiling grew even stronger during the 1990s, displaying an increase of the problematics even though the subject of gender equality was highly discussed in Sweden during the period. Moreover, Albrecht et al. (2003) believe that one of the reasons for the glass ceiling in Sweden can be a cause of the parental leave policy. This does not mean that women do not aspire to career advancement, but it could have an impact on the priorities of “doing career”. This, in turn, might affect employers’ view of women and presupposes that she does not want to take on a more comprehensive role with extensive responsibility.

There must be a change in policies in order to provide space for women to grow and develop their role in society, private as well as professional life, according to Pai and Vaidya (2009). The policy change would contribute to a reduction in pressure related to work, that women generally feel in the role of a leader. Moreover, Pai and Vaidya (2009) believe that different generations play a major role in the development of gender equality in all fields and levels. Baby boomers (born between 1944-1964) will most likely be more demanding for future job offers available in the market. Moreover, generation Y (born between 1980-1998), who are generally more integrated with the phenomenon of “gender equality”, will contribute to a more equal and accepting work- and home environment as well as childcare responsibility.

2.4 The leadership culture within the Swedish police

Culture is a highly complex term and it is almost impossible to acquire one single definition that embraces its full meaning. Thus, culture has several definitions. According to the well-known social scientist Hofstede (2001, p.25), culture is defined as “the collective programming

of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.”. Anthropologist Geertz (1973, p.89) described culture as “a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life.''. Moreover, Matsumoto’s (1996, p.16) definition of culture is “the set of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people, but different for each individual, communicated from one generation to the next”, which means that culture is dynamic and changes with time and thus is not rooted in nationality, race or biology. Another and more recent definition is that “culture refers to deep-rooted group differences in cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral patterns (Powell et al., 2009, p.599).

2.4.1 Organizational culture

Organizational culture, also called corporate culture, is a culture related to companies. Hence, an organization is a kind of culture (Smith & Peterson, 1988). Simply defined, organizational culture is “the way things are done around here” (Deal & Kennedy, 1982, p.4). A more recent description of corporate culture, presented by Messner (2013), is that organizational culture is the behavior and values within an organization that contributes to the psychological and social environment and is unique for every organization. This is also strengthened by Ashkanasy, Wilderom, and Peterson (2000) who further argues that corporate culture includes an organization’s philosophy, experiences, and expectation that has evolved over time. It is based on shared beliefs, attitudes, drafted and undrafted regulations, including how power flows and is distributed through the organizational hierarchy. However, one of the hardest things to change within an organization is the corporate culture (Ashkanasy et al., 2000). Furthermore, Ravasi and Schultz (2006) argue that corporate culture directly and greatly influences employee behavior within a firm, since the culture guides situations by defining appropriate behavior for different circumstances and personnel encounter culture as their own. In addition, Schrodt (2002) articulates that the way groups and people interact with each other is affected by organizational culture. Thus, culture is powerful. Understanding cultural dynamics hence results in a profound understanding of the underlying reasons for diversity between different organizations and in addition, to understand the reasons why culture is hard to change (Schein & Schein, 2017).

Some corporate cultures are stronger than others and strong cultures may, therefore, be highly complicated to change (Hofstede, 2001). Hall’s corporate culture model (Figure 2.1) illustrates how the organization’s shared values and assumptions of a corporate culture relate to each other and are associated with artifacts (McShane & Glinow, 2010).

Figure 2.1: Corporate Cultural Iceberg (McShane & Glinow, 2010)

The over-surface part represents the organizational culture that is visible and exposed, such as structures, policies, and goals. They mirror the way organizations get things done, influenced by what is desired from society. The under-surface part, on the other hand, represents the invisible organizational culture, such as perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and values. They mirror the way organizations really get things done (McShane & Glinow, 2010). The corporate culture iceberg is vital for this study to understand and detect the deep-rooted characteristics of the Swedish police culture. It is important to investigate whether there is a difference in the Swedish police culture in the visible and the invisible organizational culture. Furthermore, if and how this difference affects women police leaders.

2.4.2 Police culture

The Swedish national police board has defined and declared equality as equal treatment of all individuals and groups, regardless of gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, religious belief, or disability (Polismyndigheten, 2020). However, there is still a raised debate about the Swedish police culture containing inequalities (Loftus, 2008; Martin, 1996; Burke &

Mikkelsen, 2005; Archbold & Schultz, 2008; Haake, Rantatalo, & Lindberg, 2017), which in this study is relevant to gender inequality.

Researchers argue that police culture, or subcultures, are complicated to define (Skolnick, 2008; Campeau, 2015). Skolnick (2008) indicates that cultures within the police vary from place to place and have developed over time. Just as cultures differ in different countries and parts of the world, the police sector between nationalities is no exception and thereby the police cultures may differ. However, Skolnick (2008) further argues that the police culture has certain universal and stable features. Generally, critiques describe police culture as having elements of politically conservative, distinctly masculine, action-oriented, and communally isolated (Campeau, 2015). In addition, Martin (1996) portrays police culture as being sexist, macho oriented, and vulgar. Masculine ideals such as strength, heroism, and violence have for long existed within the police. Such ideals form police work environments, which significantly affect and shape law enforcement- and police culture (Loftus, 2008; Kurtz, 2008). Furthermore, despite years of policies that are grounded in equal opportunities, law-enforcement remains a heterocentric, male-dominated profession and the culture of the police has become growingly resentful of straightforward attempts to transform these dominant norms of the police culture (Loftus, 2008). By a recent study, Kurtz and Upton (2018) found indications that male police officers still strengthen gender dynamics in their environment of work, notably in informal situations. These attitudes may, in turn, strengthen contradictory atmospheres, such as hypermasculinity, in the police sector. According to the research, this masculine work environment may be an explanation for the reason of gender inequality and the slow growth rate and underrepresentation of women leaders within the law enforcement during the recent decades (Kurtz & Upton, 2017). With a lack of organizational control, these settings contribute to the persistent unfair treatment of women police (Franklin, 2007).

Previous research indicates that for female police leaders to be eligible they are required to prove their abilities on trustworthiness and capabilities (Burke & Mikkelsen, 2005; Archbold & Schultz, 2008; Haake et al., 2017) and feel a constant force in responding to their abilities towards male colleagues (Haarr & Morash, 2013). Furthermore, to be accepted women must perform better than men within the police sector. Nevertheless, women are often considered less competent than men, even if they are excellent leaders (Archbold & Shultz, 2008; Haake, 2018). Additional research found that it still exists stereotypes of the police profession viewed by male officers. Even if some male police officers express that women are equally qualified

in all aspects of the profession and consider equal treatment to be fundamental, they still have underlying beliefs that women police leaders are negatively associated (Muftic & Collins, 2014; Chu & Tsau, 2014). This is especially occurring among older policemen (Chu & Tsao, 2014).

Sweden is at the top of most gender-equal countries in the world (Regeringen, 2019; EIGE, 2019). However, by recent research constructed by Haake (2018), Swedish senior police officers, both men, and women, highlighted that the Swedish police department treats men and women differently. The norm still consists of men being of majority in leadership positions. Additionally, almost all participants in the study characterized the police organization as having gender-divided work-areas, whereas the typical “male” areas were considered to be of higher status. Moreover, the interviewees considered organizational culture as the main reason in explaining the low number of women given the opportunity to acquire senior managerial and leadership positions. This is strengthened by Silvestri (2007) who agrees that the police culture is based upon masculinity which may be part of the answer for the underrepresentation of women working in and applying for jobs within the police, and especially for leading positions. Thus, organizational culture is believed to be the solution to the problem. Organizational structure and culture must be modified and developed to diminish the problem of women being a minority in leadership positions (Haake, 2018). Furthermore, Österlind and Haake (2010) have carried out a study within the field of gender, leadership, and police research in the context of Sweden. They believe that to gain a more gender-equal work environment it requires more than just recruiting more women within the police workforce. Silvestri (2007) strengthens this by stating that recruiting more women into the police sector will not itself necessarily be enough to change the assumptions of the police being a masculine role in a male-dominated sector. But by bringing more women into the sector might help to change the macho culture in the long run (Silvestri, 2007).

According to Silvestri, Tong, and Brown (2013), the police is a sector that usually encounters organizational changes and developments with resistance which makes it a sector difficult to implement big changes within concerning new ways of thinking and working. Among other things, the gender issue is included in this discussion as it is seen as a gendered nature with limited progress within the field of integration. Further, Silvestri et al. (2013) argue that by increasing the number of women within the police sector would benefit the reputation of the

police. The research detected alarming numbers stating that four out of ten female police officers are considering leaving the workforce due to inflexibility in work tasks, low morale, and childcare considerations. Since the police often use internal recruitment when seeking for new talents for prestigious positions higher up in the hierarchy, several women are not given the opportunity to change the statistics of the female leader underrepresentation.

2.4.3 Culture examination by the Swedish police authority

According to a recent examination of the Swedish police authority’s culture, conducted by the authority's internal audit (Groth Hjelm, Ygge, & Murelius, 2019), one assesses whether the police are conducting appropriate work on cultural issues. For the work towards a well-functioned police authority, the cultural issues have crucial importance. One of the prerequisites for conducting efficient work on cultural issues according to Groth Hjelm et al. (2019) is the possibility of drawing up regulatory letters containing the top management’s stated willpower. Those regulatory letters, relevant for this study, are the police value foundation, the strategy for equal treatment and the state value foundation. Several subcultures are highlighted that affect the internal regulatory letter, control, and business goals negatively. One of those sub-cultures is the “over-trial culture”, which is characterized by the fact that decisions are not fully complied with and some unwillingness to change is present. The culture of “us-and-them” is also featured, which includes that there is an underlying culture of men versus women. Additionally, issues related to leadership were also found present in the police culture, such as unclear goals, leadership that is not developed for the regulatory letters, the distance between leaders and employees, and leader disdain. The negative impact from these subcultures generates that the work and conditions for regulation and control become considerably more difficult. On the other hand, Groth Hjelm et al. (2019) further found that the sub-cultures that mainly generate positive influence are the “loyalty-culture” and “corps spirit”. In total, four major clusters were identified in the context of the culture, which impedes the image of police recruitment and the ability to retain employees. These are (1) acting behavior against each other, eg. suppression techniques, macho- and silence culture, and harassment, (2) equal treatment, which includes gender equality, (3) mandate, and (4) leadership. A strong culture of apprenticeship strengthens indwelling patterns and makes employees less susceptible to changes. Several proposals that emerged in the examination conducted by Groth Hjelm et al. (2019) indicated that the work of discussing problems, cultural issues, and behaviors does

not take place sufficiently or widely enough. Additionally, they claim that the Swedish police authority is a “too forgiving” organization. For instance, bad internal behavior is not followed by enough harsh consequences. Moreover, findings from a survey internally conducted indicated that 94% know the police value foundation and 73% know the strategy for equal treatment. However, only 52% are aware of the state value foundation, and the internal audit assesses the result to be even worse, i.e. lower awareness about the governmental regulatory letter if the survey were sent out randomly within the police authority. According to the examination, there is no ownership of responsibility for cultural issues and there exists no guidance on Intrapolice (the police authority intranet) concerning the state value foundation. On the other hand, the state value foundation became a part of the leadership education “the direct leadership” in 2014. However, for other employees, no work has been done concerning the state value foundation. The examinations further found that there are prerequisites for conducting appropriate work on cultural issues through regulatory letters. However, more must be done to the application of the content of those letters. Suggestions on what is needed to fulfill this are, among others, better communication, speak openly about culture, improved recruitment, create a “we-feeling” and establishment of principles contributing to a good culture. The internal audit further considers that it is important to communicate the content of the state value foundation and ensure that it is also discussed in the workplace. Above all, this work and engagement must start from the top management and be penetrated down the police hierarchy. Not to change the work towards a better police culture can lead to a continuing, ongoing, and negative impact in the police authority. Which in turn can have major negative consequences for the authority and may result in that the Swedish police authority does not meet the requirements of the government ordinance considering efficiency and use of state resources. Every government employee has the responsibility to be aware of and live by the values, policies, and strategy for equal treatment. Not following these can lead to the consequence of not achieving set goals and result in significant negative consequences for the authority (Groth Hjelm et al., 2019).

2.5 Actions taken for gender equality in the Swedish police authority

The Swedish police authority has a history of being male-dominated. In the past, only tall men had the opportunity to become police officers. It was not until the 1950s that women could join and in 1957 the first woman was accepted to the Swedish police education. However, it took

another 24 years until the first female police officer was assigned a high leadership position. In today’s fairly striving society, both men and women operate in the Swedish police sector (Polismuseet, n.d.), and the Swedish government together with the police authority is said to constantly work towards an even distribution of power and opportunities among men and women. However, leadership positions still tend to be in the majority of men (Polismyndigheten, 2020).

According to the Swedish Parliament (Sveriges Riksdag, 2007), there are several actions that the police have taken to increase the proportion of women in leading positions. The police authority has publicly stated that they want to recruit more women, both for the police education but also in leadership positions. This is, among other things, done by increasing the offer of leadership training and mentoring programs. There has also been a change in advertising of vacant positions for managerial positions to be adapted to both genders and attract female applicants. In addition, in the police annual report (Polismyndigheten, 2020) it is described that management's efforts must be implemented to promote gender equality and that trainee programs should be developed to increase the number of women in operational management, specifically at the local level.

The Swedish police authority is not using quotas (Polisen, 2018). However, there has been a change in the application tests for police education. The reason for lowering the requirements of the physical test for women is to ensure that all search groups have the same opportunities to be accepted and that in addition to the strength test, the remaining requirements are the same for all participants. The requirements for women are to obtain a three on a nine-degree scale, unlike men who must reach a six to get approved on the physical test (Polisen, 2018). This suits the above description of how equality should be executed from the Swedish parliament (Sveriges Riksdag, 1992). The fact that one should not judge an applicant according to his or her gender, but for the competence they possess. Due to evidence in medical phrasing that women and men do not have the same physical capacity, this is considered a change that is not gender-discriminatory (Miller et al., 1993).

Moreover, in 2015 the Swedish government implemented an extensive reorganization of the Swedish police, several police authorities became one single authority, whose aim was to gain clearer control and better conditions for the police work. An important part of the

reorganization was to raise the ambition level of leaders and employees, which resulted in more direct leaders and smaller group sizes, including more present leadership (Statskontoret, 2018). To get a concrete overview of how the women representation has evolved within the Swedish police, we have investigated statistics from the police annual reports of 2010, 2015, and 2019. It is important to note that we exclusively have investigated the representation of the police section, i.e. not the civil section of the Swedish police authority. Furthermore, 2015 is considered critical to include since the reorganization of the police authority took place that year (Statskontoret, 2018). The Swedish police authority has stated that they strive towards a higher representation of women accepted to the police education. We can see a steady increase in the total number of admissions. However, no proportion of female applicants are reported in 2010 and 2015. Nevertheless, in 2019, 32% of the accepted were represented by women (Polismyndigheten, 2020). Moreover, the police authority has a goal to greatly increase the number of police employees within the authority. In the year of 2010, 27% of the police employees were women (Polismyndigheten, 2011), in 2015 31% were women (Polismyndigheten, 2016) and 2019 the representation of women was 33% (Polismyndigheten, 2020). Furthermore, the police authority has stated that they desire a higher representation of women in leadership positions as well, and thus has implemented leadership programs in direct, indirect, and strategic levels. The percentage of women represented in these programs in 2010 was a total of 24% (Polismyndigheten, 2011) and in 2015 a total of 24% (Polismyndigheten, 2016). In 2019, on the other hand, only the leadership program on a direct level was reported, which was amounted to 39% of women representation (Polismyndigheten, 2020). Additionally, the number of employed women in leadership positions was in 2010 17% (Polismyndigheten, 2011), in 2015 21% (Polismyndigheten, 2016), and in 2019 the percentage had increased to 27% (Polismyndigheten, 2020).

2.6 Power motivation

Knowing and understanding the motives for working within a specific section in the hierarchy, in a particular sector or profession, is important for this study, as a comprehensive understanding of these aspects can explain why an individual wants to achieve a certain position and why one wants to strive towards acquiring power.

2.6.1 Power motivation for working within the private vs public sector

The motives for working in the public sector, such as the police, or for private sector organizations have been proven to be different. In a study conducted by Rashid and Rashid (2012), research has been conducted about several hypotheses explaining the different motivations of working within the public vs. private sector. The most prominent motives for working in the private sector have proven to be the question of salary and career opportunities which have shown to not be in the center of focus for public sector employees. Instead, public sector employees put more emphasis on job content, individual development, autonomy, and interesting work tasks. Moreover, the importance of working in a supportive environment was demonstrated in the results to be of higher interest for public sector workers. Furthermore, the results of Rashid and Rashid’s (2012) study show that work-life balance is not as prioritized for private-sector employees compared to public sector employees resulting in fewer work-family conflicts.

2.6.2 Power motivation for the police profession

It is a general assumption to believe that the most prominent reason for becoming a police officer is due to the desire to have high levels of power over people (Wu, Sun, & Cretacci, 2009). According to earlier research, this was the case for both men and women. The desire for having authoritarian personalities, gaining power, and control were the most outstanding arguments for becoming a police officer. Up until today, this is an outdated assumption and the most common reason is the urge to help people in society (Raganella & White, 2004). Wu et al. (2009) argue that other factors as to why one would like to become a police officer are due to job security and a steady salary. Furthermore, Morrow, Vickovic, Dario, and Shjarback (2019) announce that helping others, job benefits and safety are other common features for becoming a police officer.

2.6.3 Power motivation for becoming a leader

As for the motives for becoming a leader, power motives can be connected to the general traits of a good leader. Common characteristics of a leader are that they radiate energy, they want to make a big impact, being prestigious and sometimes show tendencies of being narcissistic. In research conducted by Chan and Drasgow (2001), findings showed of a connection between characteristics of individuals in leading positions and the motivation to lead. The study resulted in leaders finding the opportunity to lead, enjoying overseeing situations as well as finding

themselves having the traits and social skills necessary for being in a leading position. Moreover, Mascia, Dello Russo, and Morandi (2015) discovered that leaders often have a high degree of self-esteem and confidence. Furthermore, they found a relationship between the motivation to lead in combination with individual characteristics and structural characteristics of organizations (Mascia et al., 2015).

2.7 Research model summary

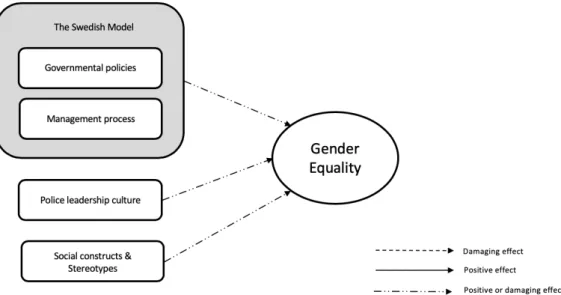

To give the reader a clear overview of the frame of references we provide a research model (Figure 2.2). The model represents the key factors which influence the gender equality level and work within the Swedish police authority, explicitly in the context of women in leadership positions. The Swedish model provides the categories of the governmental policies which further should guide the management process in embracing gender equality. It was also found within previous literature that the level of- and work towards gender equality is influenced by the leadership culture and social constructs, such as stereotypes. The model will be used throughout the thesis as a structure and to maintain a consistent line where linkage between theory and empirical findings will be drawn in the compilation of our conclusion.

Figure 2.2: Research model of gender equality influences, in the context of the Swedish police (Jonsson & Larsson, 2020).