How

PLAYFULNESS

in

HEALTHCARE

applications

enhances children’s

ENGAGEMENT

and

ENRICHES

their lives as they

LIVE WITH CHRONIC DISEASE

Implementing gamified elements in a healthcare application for children with diabetes to improve engagement and enrich their self-knowledge, which contributes to the better handling and

management of the disease.

Chang Cai

[Interaction Design] [Two-year master] [15 credits]

[Second Semester/ 2019]

Abstract

The idea is to determine how game design can be applied to generate and sustain motivation in serious gaming, or applied gaming, design projects. Elements that spark a sense of playfulness embedded in an application in a non-game context have been shown to enhance the user’s engagement. DiabetesNinja is a healthcare app for children with type 1 diabetes, but the children who used it did not engage with it as they were meant to. When living with diabetes, one’s disease-related knowledge and self-management are important, but children can only learn these when they use and interact with the app properly and regularly. Therefore, as a part of learning to live with a chronic disease, the primary aim was to increase children’s motivation to use the application. This study explores relevant theories in the fields of gamification, pedagogy and healthcare. In this exploration, three co-design workshops were conducted to gain an understanding of the children’s current user

experience, explore their attitudes towards game elements, and identify design possibilities. The outcome is a serious game design concept where diabetes index registration functions are embedded in the levelling up (bonus) system. In addition, the visually customizable Tamagotchi concept installed in the levelling-up system acts as an assistant to motivate the children on a regular basis and may contribute to the children's long-term engagement. I conclude with how the levelling-up system follows the pattern of diabetes data registration and is an appropriate game mechanic for both motivating children and easing their heavy cognition load in the disease-related index registration sequence.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

1.1 The main Stakeholder, DiabetesNinja 1.2 Problem definition

1.3 Research questions

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Self-Determination Theory (SDT) 2.2 Personal Informatics (PI)2.3 Gamification

2.4 Children’s learning theories 2.5 Pedagogy motivation 2.6 State of the art

3. Methodology

3.1 The Double Diamond method 3.2 Co-design

3.3 Prototyping

4. Project Process

4.1 DiabetesNinja user-experience discussion 4.2 Workshops

4.2.1 Workshop One – problem definition

4.2.2 Workshop Two – children’s attitudes and behaviour investigation 4.2.3 Workshop Three – prototype testing

5. Discussion

5.1 Discussion of the design project 5.2 Discussion and research process

6. Results

7. Future work

8. Conclusion

9. References

10.Appendix

1. Introduction

Sweden has the world’s highest rate of type 1 diabetes, and children with type 1 diabetes need to take insulin regularly to help them live normal lives like other children. Given that diabetes is a chronic condition, the diagnosis requires a lifetime of intensive

self-management characterized by the frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose for achieving reasonable metabolic control (Cafazzo et al. 2012). Learning to live with diabetes and feel secure is hard enough for adults, but it is even harder for children who barely understand the disease. It is also important to remember that children want to be treated normally so that they feel "the same" as everyone else as they grow up. To receive support in their growth is important. In the everyday life of children with diabetes, their closest group of caregivers must be able to access and interpret the data of the children’s physical status. However, self-management is also important for children with diabetes. For a regular and healthy life, they must not only have adequate knowledge of the disease but also be able to manage it themselves. Therefore, a tool that can support more knowledge and

self-management is essential for children who have diabetes.

1.1 The main stakeholder, DiabetesNinja

Diabetes Ninja is a mobile healthcare application for children with type 1 diabetes. It is the main stakeholder of this design project. According to the founder – a father who has a child with type 1 diabetes – research into other parents’ and guardians’ needs led to the vision of this application to assist and follow children with type 1 diabetes from childhood to

adulthood safely and smoothly. The main functions of the app are to register data, monitor blood sugar, and measure carbs. The first version has already launched on both the IOS and Android platforms.

DiabetesNinja currently has 3449 registered users in Sweden. The redesigned registration improvements in the new version would not consider blood glucose data automatically upon registration. This new version launched in September 2019 both on IOS and the Android online stores.

The target group comprises schoolchildren aged between 7–12 years. The children can use this application as a blood sugar monitor and insulin meter by manually registering their blood sugar value and taken food value. The targeted group can then use the function of the carbohydrate calculator to transform the food value input into carbohydrate values by DiabetesNinja.

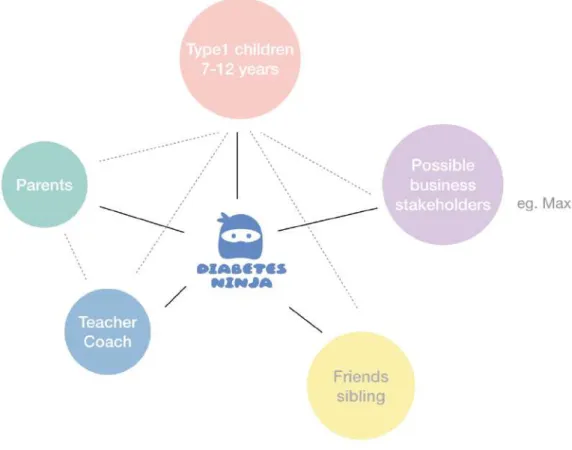

In addition to the group of children, DiabetesNinja indirectly targets two other groups – the parents and the coaches/teachers of the children’s school. The figure1. shows the

are a targeted group because they can monitor their child’s physical status by accessing the registered data when the child is at school. Teachers and coaches can also access the registered data, interpret the child’s status, and make any appropriate decisions. Based on individual needs, this application acts more like a data diary and measuring meter, and it plays an important role in supporting caregivers’ dedication to the future health of children with diabetes.

This project was conducted in collaboration with my UX designer colleague, Kyösti Hagert.

1.2 Problem definition

Most of the children in Sweden with type 1 diabetes have an insulin pump and blood sugar meter with them in order to receive a daily insulin dose and to check their blood sugar level. DiabetesNinja is used to keep a record of the data and to monitor the child’s physical status. However, the feedback shows that most children only remember to register with the

disease-correlated index after being reminded by their parents, and for some younger children, the caregivers are the users who must register the data. The children’s lack of motivation in using the application is an apparent obstacle, especially with the older children. Figure 1. The relationship mapping among targeted groups and other stakeholders

Another obstacle to DiabetesNinja being used properly relates to how difficult it is to register the right amount of food. Relevant research has shown that AR technology has positive effects on sparking motivation and improving accuracy when registering meals by providing playful user experiences (Rollo, Bucher, Smith, & Collins, 2017). However, it is difficult to sustain the children’s long-term engagement without applying other gaming elements because children tend to lose interest in activities unless they are having fun.

1.3 Research questions

This was a 10-week project, and given that the children's motivation to use this application will directly affect the other intended functionalities, the project focused on the primary aim to enhance the users’ engagement. One salient point of this project brought in by the main targeted group was that the motivation to use this application should not affect the

children’s school life. In other words, the children should not register their data more than necessary during school hours. This needs to be taken into consideration when thinking about self-management in the design process. In addition, recent research about

gamification and how its related playful experience can be applied to the healthcare field shows that it has practical effects on users’ motivation and engagement. Based on these two points, two research questions have resulted:

1. How can playfulness be used in a healthcare application for children with diabetes in order to enhance their engagement?

2. How can the functions that the children find difficult be redesigned and replaced with a more simplified interactive procedure that they can relate to?

In this research paper, I first analyse the DiabetesNinja application from its built-in context to its usability to give a full picture of how it works and where it could trigger an unpleasant user experience. Thereafter, I discuss some paradigms in the heathcare context in order to gain pragmatic and specific inputs on interactive behaviours. For example, what interactive behaviours can optimize the inter-individual connection that in turn can increase one’s personal healthcare awareness? In this project, two categories – the ‘human–computer relationship’ and the ‘human–human relationship’ – act as a foundation for understanding the relationships among the multiple targeted groups, thus creating a more diverse user experience (UX). The research covers fields such as psychology, cognitive behaviour and other social sciences. The literature review stage follows the research direction, which takes into consideration the effects of different scientific disciplines, such as gamification, PI (Personal Informatics) and pedagogy, on motivations. For example, it considers how gaming elements can be used as design methods for increasing motivation that give rise to playful behaviour and mindsets and how game elements can be applied to increase feelings of satisfaction that can further enhance engagement. In line with the guidelines from the

the bonus system and the Tamagotchi element positively influence the children’s motivation. At the same time, the game levelling-up mechanic can match disease-related data

registration requirements.

This article concludes with a discussion about how interaction design contributes to the healthcare context, as it reviews and explores insights that can benefit the interaction design field.

In accordance with The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 2018), data that has been collected containing personal information has been handled to the best of my abilities according to the guidelines. Further, the Swedish Research Council Guidelines for ethical conduct (2017) has been consulted.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

The model of intrinsic and extrinsic work motivation has as its foundation the expectancy-valence theory of motivation, which can be defined as the feeling of satisfaction that is automatically experienced when someone finds an activity naturally interesting, which leads to better performance and thus future rewards (Vroom, 1964). This model shows how autonomous motivation and controlled motivation within self-determination theory (SDT) – which involves the user feeling that they have autonomy – is used in pragmatic applications. Thereafter, according to Gagné and Deci (2005), the core of SDT involves the distinction between these two types of motivation, which refers to behaviour in terms in whether they are autonomous or controlled, depending on the degree of necessity. The importance of the SDT model reflects that “extrinsic motivation can vary in the degree to which it is

autonomous versus controlled” (Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L., 2005, p. 26) and that man-made consequences, such as tangible or verbal rewards, can result in spontaneous satisfaction.

2.2 Personal Informatics (PI)

Personal Informatics helps people collect and reflect on personal information (Li, Dey, & Forlizzi, 2010). Advancements in sensor technologies allow internet access and the ability to visualize personal information. These technologies allow personal informatics systems to support people towards self-reflection and self-knowledge. Users can both participate in the collection of personally relevant information as well as review and understand the

information. This process can give rise to an understanding of themselves and the factors that may influence their lives (Rapp & Tirassa, 2017a). One important feature of personal informatics is time-tracking. People have a limited memory, and it can be hard to reflect on patterns and trends for an insightful reflection. Thus, a time-tracking function can support the constant and consistent monitoring of certain behaviours, which can give rise to a whole new understanding. Visualizations in the form of graphs that represent the collected data are also a key feature of the application. They give a more simplified overview of personal data, and different visualizations will have a different impact on the user’s self-awareness and self-reflection (Epstein, Cordeiro, Bales, Fogarty, & Munson, 2014).

In addition, personal informatics (also known as the ‘quantified self’) as a tool collects and displays behaviour and physiological information (Li, Dey, & Forlizzi, 2012). The theoretical assumptions of PI rooted in and borrowed from behaviour change theories results in a focus shift from the self to the behaviour to be changed (Rapp & Tirassa, 2017b). Previous phone applications have shown that physical activities can change an individual’s behaviour, for example, by “providing simple rewards for goal attainment and for performing the desired behavior” (Consolvo et al., 2008, p.55) According to Li et al. (2012), information about the factors that affect physical activity may be needed for deeper self-reflection and increased

the self and its evolution over time through an understanding of “the behavior and what causes the behavior” (Li et al., 2012, p. 7:3). Given that theoretical assumptions are partly borrowed from behavioural change theories, the current rhetoric of PI includes discussion on implicit assumptions in behaviour itself and self-knowledge. For example, “behaviour” as an atomistic entity can be addressed without referring to the individual’s inner life. The change will occur as a new stage after the individual has rationally determined a “newfound understanding” of her behaviour, and such a change will affect the target behaviour (Rapp & Tirassa, 2017). These discussions repeatedly emphasize the initial aim of PI, which is to bring about a change in behaviour (Li, Dey, & Forlizzi, 2010).

2.3 Gamification

The newly coined term, ‘gamification’, is defined as the use of the video game elements in non-gaming systems to improve user experience (UX) and user engagement (Deterding, Sicart, Nacke, O’Hara, & Dixon, 2011). Deterding (2011) also explains that game elements should be able to create an enjoyable and engaging experience in a non-game context. In 2014, the effects of employing game elements in the healthcare-related context showed that game design thinking could make a healthcare app more fun and engaging (Pereira, Duarte, Rebelo, & Noriega, 2014). In addition, some researchers discussed certain

functionalities, like that of ‘Tamagotchi’, as a game element that can enhance the interaction by playing on the need for people to nurture (Bickmore & Picard, 2005).

Originating from the digital media industry, gamification is today an innovative aspect

borrowed by other scientific disciplines (Deterding 2011) that apply the game design process and game elements as design methods in terms of “design with a purpose”. To apply

gamification enhances motivation and sparks playfulness and mindsets in increasingly new contexts (Barr 2008; Deterding et al. 2011). The design of many healthcare applications applies gamification as an approach. Relevant research shows that gamification can positively affect the participants’ emotional experiences (Lazzaro, 2004), which in turn enhances their engagement with the digital tools, for example, diverse technology-based solutions can help individuals adopt healthy lifestyle habits (Pereira, Duarte, Rebelo, & Noriega, 2014) and have a positive impact on cognition by providing complex systems of rules for players to explore through active experimentation and discovery (Lee & Hammer, 2011). These findings explicate the heuristic attributes in employing game elements and show how gamification may be an effective teaching method (Papastergiou, 2009). Moreover, gamification can also enhance social skills such as communication, leadership, and collaboration, which can also be applied to primary schoolchildren and their growth. When applying game elements in a non-game context, understanding the distinction

between ‘gamefulness’ and ‘playfulness’ can present a clearer picture of where the values of behaviour and mindset are in focus. Gamefulness introduced as a systematic complement to

‘playfulness’ (Deterding, 2011) focuses on the qualities of gaming, while playfulness focuses on experiential and behavioural qualities. In a non-game context, the game elements can contribute to the playfulness through the gameful experience. However, the focus must be on the ‘gamified’ process or on how the design strategies of game elements can give rise to playful behaviours and mindsets, so that the overall aim of the design can be achieved. In other words, enhancing playfulness in non-game context by designing the game elements with playfulness in mind should result in the goal of playable gamefulness.

2.4 Children’s learning theories

Contemporary concepts in learning assert that children learn through a process in which they interact with people in their environment and in co-operation with their peers

(Vygotsky, 1978). The learning process is not simply children making knowledge their own, but rather the child must make it their own within the community from which they get the knowledge. Social interaction is thus assigned a central role in facilitating learning. Indeed, children’s knowledge is often realised in interactions with those around them who are more knowledgable, for example, peers, siblings, teachers, parents, and other. Vygotsky (1978) highlights that achieving successful learning and development involves processes of cooperation. Here, the key to success is with language and communication. Children learn language by using it to communicate, and the phenomenon of speaking when learning language derives from the notion of ‘performance’ in learning. This notion emphasises the importance of ‘doing’ in learning processes and shows how general everyday experience can reinforce learning processes in children.

2.5 Pedagogy motivation

The effectance motivation model applied in sport shows the significant role other people play in in terms of increasing motivation (EMM; Harter, 1978, 1981). EMM shows that parents play an essential social role in the consolidation of children’s perceived competence. In addition, significant others also influence the process of socialization and the cognitive maturation of children. The EMM findings have also shown how age-moderated children perceive the importance of competence through feedback from their significant others. The empirical investigation regarding sources of competence feedback in different age groups shows that the children in the 8–9 years age group have a high preference for evaluative feedback from their parents, but the 10–13 year-old age group age group shifts their preference for evaluative feedback from their parents to their peers. Children who are 7 years old display the highest reliance on their parents’ feedback compared to other age groups (Chan et al. 2012).

In addition to parent and peers, coaches can also be a social influence on children, and this is important for young children’s perceived overall competence. In the interaction process, these alliances with social groups generate four motivational outcomes: effort, enjoyment, competence, and competitive trait anxiety. Though these findings originate from research about social groups' influence on children sports performance, the positive feedback from a macro perspective can support the hypothesis that these social groups will have an active impact on children’s behaviour.

2.6 State of the art

In the healthcare and self-management context, there are some classic examples of

applications that were designed with the similar purpose of increasing motivation and long-term engagement:Aloe Bud, Habitica and Bant.

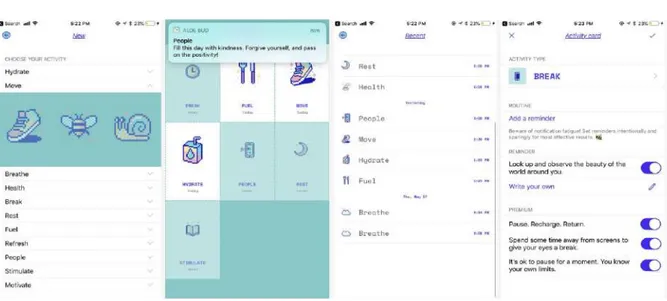

• Aloe Bud – A self-care companion app

Aloe Bud is a self-care companion app that gives users gentle reminders via push

notifications. Users can customize their push notifications in aspects such as time, activity, and frequency by choosing their own idea dailies. The positive feedback about Aloe Bud highlights how its customizable functions and multiple approaches are universal in relaxing the users. In addition, the suggestions (rather than instructions) make the push notifications gentle and unobtrusive. Also, the easy navigation and pleasant colour scheme make it easy for new users. Other popular aspects are that it gives infinite chances to succeed and does not quilt-trip the user if they do not complete a task. However, despite these easy features, some new users were nevertheless confused about the setting functions for both the activities and reminders.

The feedback about the functions of setting two reminders is vague for end-users, indicating the importance of simple cognition operations in digital platform interaction design. In the DiabetesNinja project in particular, the target group is primary school students, and therefore, clear and simple-to-understand interactive procedures are needed. It is also worth noting that the features of Aloe Bud, like self-notifications, provide a relaxing experience, and this could be taken into consideration regarding self-management in DiabetesNinja.

• Habitica – HabiRPG (Role-play game)

Habitica is a self-improvement web application with game mechanics overlaid to help the player keep track of and remain motivated to achieve their goals. Following the long-term goal, Habitica applies game elements to help users schedule their habits. The two progress bars ‘experience’ and ‘health’ are represented in the common colours of green and red to deliver positive and negative signals to make users aware of their activities. At the same time, Habitica also applies the bonus system to motivate users in reaching their real-life goal.

Figure 3. The Habitica application

The motivation in using this app comes from the feeling of satisfaction one gets when completing the pre-set habits, dailies, and tasks that users have created on their own. This is a good way for children to set their own goals. Also, the ‘Tamagotchi’ assistant activates users’ motivation through meeting the users’ need to nurture. However, the punishment aspect within the system causes users to avoid registering their real-life statuses, and also, few people tend to use it long term. The feedback and reviews from the users are useful because they can give insight on combining different game elements and their dynamic can create use aesthetics which can contribute to sustaining the engagement.

proper strategy in application redesign that can lead to discovering a better way to use the application.

• Bant – A healthcare app for children with type 1 diabetes

The Bant application was designed by diabetes experts after receiving feedback from patients. Originally from Canada, its main function is to easily track diabetes activities and receive personalized feedback. The targeted group is that of children with type 1 diabetes aged from 11–16 years. The app is a good example of having the insight of diabetes experts to draw upon. From the users’ feedback, two features can be taken into account when implementing the latest interactive version of DiabetesNinja: (1) Users can take a photo of their meals to help them remember what they ate and relate it to their blood sugar value, and (2) Bant can pull data from other health apps to support users in understanding how their lifestyle impacts their diabetes.

In addition, the findings from the latest application research (Cafazzo, Casselman, Hamming, Katzman, & Palmert, 2012) reveal certain important features in improving self-management and engagement in the diabetes context:

• Given that the key self-management features require blood glucose data, it can be inferred that use of the app is dependent on users first having uploaded this data. • For the users who were testing frequently, the data shows the improved

self-management of diabetes.

• Overall satisfaction levels were high, suggesting that app users found Bant useful, specifically in features related to the management of out-of-range blood glucose trends.

• This suggests that these users gained insights around their SMBG (self-monitoring of blood glucose) data, which may have led to positive changes in their

self-management behaviour. (p. 1)

The feedback from this diabetes app is useful to refer to despite the differences in the age ranges of the targeted groups. The findings will be taken into consideration in the design research process for gaining practical insights that can be compared with the DiabetesNinja design.

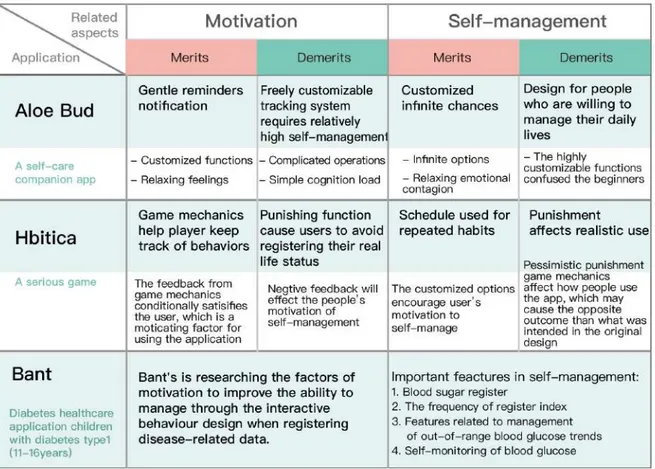

• Analysis

These three apps employ a series of features to increase users’ motivation and improve self-management, for example, with preset habits, push notifications, and reviewing and

feedback systems.

The Aloe Bud and Habitica apps are similar in that they provide interactive experiences, but they differ in their design philosophy: Aloe Bud focus on an emotional connection where one never needs to feel apologetic, whereas Habitica has a strict review system.

The motivation for using the apps lies with the conditions that trigger function effects in both Aloe Bud and Habitica. Both applications offer pre-set tasks, as the pre-set function enables users to self-schedule, manage and monitor their dailies. The feature provides users with the ability to make informed, uncoerced decisions that meet their autonomy needs and make them feel more emotionally satisfied. Thus, pre-set technology works well for

motivating users.

In addition, the long-term motivation to use the application is also important, especially in the context of self-care and for supporting the ability to self-manage. The operational difference of these two applications is with the reviewing system:

Aloe Bud focuses on those who suffer from a busy and stressful life. The application was originally an online check-in tool to practise self-care in a relaxing way. Notifications are the main interactive technology, and they have been designed to be as gentle and pleasant as possible:

• A reminder function helps users to achieve effective results by reminding users but avoids ‘notification fatigue’.

• The Check-in and Reflection functions provide users with optional choices so they can either follow notifications to complete pre-set activities or make reflections by

writing down notes.

• Pre-set activities are adjustable to meet the users’ higher need for autonomy. • The notification system is adjustable to ease their intensity by making them less

Habitica uses a bonus system to keep the motivation level consistent and to improve

engagement with the application. It is a serious game which involves the process of

completing tasks in a more fun way. Notifications within Habitica act as an assistant for the daily reminders. To enhance UX, Habitica increases gamified dynamics to augment

playfulness in the interactive process.

In Habitica, users create a character and gain virtual experience and virtual money as

rewards when they finish their real-life tasks. The virtual experience and money may be used for upgrades or to uncover other possibilities. For example, the virtual money could be used to buy a new sword for the character. In this reward process, users recognize their

competence and feel good about themselves. The ‘party’ function can eventually be unlocked, and with it, users can interact with other users, and personal tasks will start to affect the nutrition levels of other users’ characters. With bringing in the community concept, the party function transforms the relation between the users and the application to that of social status, whereby users can feel involved based on mutual respect and interdependence. Relatedness is the one of three principles of self-determination theory (SDT), which

constitutes human psychological needs. Habitica shows the affordance of applying three psychological needs in a gamified environment.

However, the feedback shows that it is vague when comes to the functions of ‘Dailies’ and ‘To-dos’, and similar responses (Aloe Bud) on pre-setting tasks and notifications have also been reported. These insights reveal the importance of simplicity to new users.

Figure 5. The contra-distinction of the three applications

Figure 5 compares and contrasts the distinct technologies in terms of motivation and self-management in the three described applications. Emotional design and SDT could be applied as a design approach in designing technologies that can contribute to motivation and self-management. Gentle notifications and customized infinitive chance as materials can make users feel relaxed, as relaxing is regarded as valuable in the implementation of the Diabetes Ninja UX design. In addition, SDT theory applied through gamified mechanics is also a practical resource for not only testing and understanding their motivation to use the

application but also for delivering disease-related knowledge which is essential for their self-management.

This practical case study and any continued research about Bant adds to the body of

knowledge of how the diabetes index contributes to the ability to self-manage. The empirical results could support design research process pragmatically.

3. Methodology

The review of similar applications on the market shows that gamification as a heuristic approach can be used to enhance user experience in terms of usability or playability in a non-game context. Given that games are part of children's experience and a way to learn about life, gamified information systems can improve their experience (Deterding & Sicart et al., 2011). Motivating children to use the application actually involves satisfying their

psychological needs. In order to strengthen the advantages of the gamification, the gamified elements require design that considers two aspects: 1) The satisfaction of competence and autonomy, and 2) satisfaction in terms of social relatedness. In this case, to successfully design an interface that can increase motivation, we need to determine:

• The children attitudes towards the game element in DiabetesNinja context. • The children’s ideas about autonomy and competence in the diabetes context. • If children play with DiabetesNinja on a daily basis.

3.1 The Double Diamond model

Double Diamond (see Fig. 5) as a method framework has been used widely across disciplines in design projects with the purpose of facilitating the creative process. The Double Diamond model was first illustrated at the Design Council ("The Design Process: What is the Double Diamond?", 2019). Following IDEO HCD, Human Center Design theory, this model has divided into four distinct phases – Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver, which are used to support opportunities for inspiration, ideation, and implementation. The diamond shape reflects creative processes in which a number of possible ideas are created (divergent thinking) before refining and narrowing them down to the best idea (convergent thinking). With the implementation of iterative ideation in the design process, the design process includes two rounds of divergent and convergent thinking, which means that ideas are developed, tested, and refined many times, and weak ideas can be dropped in the process.

Discover – The Double Diamond model emphasises that, in the discover stage, the focus

should be on the project in a fresh way by noticing new things and gathering insights.

Define – The second quarter represents the definition stage, in which designers try to make

sense of all the possibilities identified in the discovery phase. Which matters most? Which should we act on first? What is feasible? The goal here is to develop a clear creative brief that frames the fundamental design challenge.

Develop – The third quarter marks a period of development where solutions or concepts are

created, prototyped, tested and iterated. This process of trial and error helps to improve and refine ideas.

Deliver – The final quarter of the double diamond model is the deliver stage, where the

resulting project (e.g. a product, service or environment) is finalized, produced and launched (Design Council, 2019).

In this UX design project, the Double Diamond model is used as a design guideline for both project time and process management.

3.2 Co-design

Transformations in the design field reveal the coming challenge of solving wicked problems and fuzzy opportunities that require collective creativity. ‘Co-design’ and ‘co-creation’ are new terms that are discussed often within this field. The traditional definition of designers has widened to include, for example, co-designer, facilitator, and translator. Meanwhile, the co-design approach is also a historical and discipline orientation. It spans a wide spectrum of domains and inspires flexible ways of using methods, tools and techniques in both

commercial- and community-oriented contexts as well as in the research context. From the perspective of the social sciences, co-design goes beyond the theatrical norm. Beyond academia, it steps outside the laboratories into practices that can benefit from a

participatory viewpoint. In addition, adapting to society’s needs in terms of design shows the changes in the interpretations which is reflected through ‘design’ changing from the noun form (i.e. a design) to the verb form (i.e. to design) (Gagné & Deci, 2005; -N. Sanders & Stappers, 2012). For example, ‘product design’ and ‘interior design’ can be referred to as ‘design for experience’ or ‘design for service’. This design framework highlights the role of end-users who have played a specific role as ‘the specialist’. In contrast, with the original design process, designers in the co-creation process need to manipulate the design process so that they can shift their role from ‘design specialist’ to that of ‘facilitator’. The facilitator could apply design knowledge through methods or tools that also transform the language of

design to achieve mass understanding so that participants can easily participate as well as motivate and dedicate their opinions.

Given that the project aims to determine the possibilities of applying the psychological feeling of satisfaction by using a gamified approach to increase the children’s motivation, during the research involved in the design process, children can act as ‘the specialist’ by giving their ideas about specific scenarios. The reactions and feedback of the children are essential in helping the designer gain actual insight, and the co-design process could provide designers with objective input. It is an effective methodology in the research process that leads to rational, creative and persuasive design.

Starburst

The Starburst method has been used frequently in the business and marketing context as a brainstorming technique through generating questions. The method is typically used at the beginning of a project “to flesh out the topic question or to begin analyzing a specific Insight or Trend” (https://www.shapingtomorrow.com/webtext/25).

The value of this method is launching a project systematically with many perspectives and valuable insights as possible. Hence, instead of using the questions for searching answers, the questions words are designated to use for generating relevant questions in a quick path from: Who? What? When? Where? Why? And How? aspects. According to the

ShapingTomorrow website, “The answers can then be used iteratively to create more Q&A’s” (https://www.shapingtomorrow.com/webtext/25).

The ShapingTomorrow website also lists the following benefits of the Starburst method: • Fast understanding of the questions that need answering

• Valuable method to ensure that all the relevant issues have been considered • Systematic, comprehensive and multi-purpose

• Fast and ultra-low-cost

• Can be used by both individual analysts and teams (https://www.shapingtomorrow.com/webtext/25).

The ShapingTomorrow website also mentions a possible disadvantage of the Starburst method – as it is a brainstorming tool, it cannot be used for project planning. For a project to move forward, other methods need to implemented to meet the needs of the timeline, management structure, or project goals.

In the DiabetesNinja project, given that the application has many stakeholders, this method was used at the beginning of the project to help clarify the goal of enhancing the UX.

Role-playing

According to Hanington and Martin (2012) in Universal Methods of Design, “Acting in the role of the user in realistic scenarios can forge a deep sense of empathy and highlight

challenges, presenting opportunities that can be met by design (p. 148). By changing the role to that of the stakeholder in the real scenarios, designers could use role-play as an approach to expand their understanding through details, behaviours, and perspectives from the scenarios of use. This approach can also be used for problem-defining and problem-solving. Using role-playing tools helps designers gain insight from the users’ perspective. The process is typically easy to organize, while the sophistication lies in the entire formation of the scenarios where their trueness could guide the acting and be regarded as objective support for discovering challenges and opportunities (Hanington & Martin, 2012).

Hanington and Martin (2012) mention the benefits and disadvantages of using the role-play method. I summarize these here:

The advantages of using role-play: • It is a low-cost method

• It can be applied in contexts with strict ethical requirements in which normal observation would not feasible.

The disadvantages of using role-play:

• It can be used for gaining a users’ perspective, but the outcome or the insights nevertheless need to come close to the real situations (or testing with the end-users later) in order to be feasibile.

As a supplement to the DiabetesNinja project, the role-play method was used along with the Starburst method to enhance the reliability of the data at the beginning of the brainstorming stage due to the limitations of the workshop conditions.

Physical movement as a method for replying to questions

Physical literacy is defined as involving individuals who move with competence in a wide variety of physical activities that benefit the development of the whole person (Cairney et al. 2016). The consensus on physical literacy is that physical literacy also involves motivation, confidence and physical competence. In the context of children participating in a

questionnaire data-collecting process, the motivation for children aged between 7–12 years to participate in answering questions will be one factor in the accuracy and quality of

answers. The process of answering questionsrequires children’s attention and their ability to control their behaviour, which is one of three aspects of cognitive abilities. The empirical

attention; most of this research has focused on school-aged children (Cairney j, et al., 2016). Hence, physical movements have been chosen as a method for the children to answer questions and give their opinions about using DiabetesNinja. It also acts as a test for

understanding the effects of gamified elements in children’s participation and engagement. In the workshop, the method of rating scale questions has been redesigned so that the child makes movements between options instead of answering the questions orally or on paper. The interview process of understanding a series of questions and giving their answers is a challenge for children. The form of questions and answers reflects a pathway between thinking-movement activities and cognitive ability. A possible model (of the potential

moderators of the relationship between thinking-movement activities and cognitive ability in children) for children in Figure 6 shows that enjoyment, fun, and competence will affect children's executive functioning. Therefore, the game mechanisms are a good tool for creating playfulness in participant engagement, as it can reduce any possible overwhelmed feelings caused by paperwork. Another reason to implement physical movement is that it makes the process easier for the designer and facilitator to gain an overall view of children's perceptions about research objects by observing their actions. The benefit of having the participants make movements is that it makes visual the potential ambiguity of participants’ thinking, which could contribute understanding that which is unknown and thus lead to innovation.

Figure 7. A model of the potential moderators of the relationship between thinking–movement activities and cognitive ability in children.

Probe with symbol

Toolkits are a technique that can elicit personal experience; thus, the tools within toolkits can reveal deeper levels of understandingm as it can access both tacit and latent knowledge. Methods that study what people Say, Do and Make help access different levels of knowledge,

and the tools chosen for the technique need to assist the process with an accessible approach for what the participants Say, Do, and Make(Bickmore, T. W., & Picard, R. W., 2005) .

The aim of design research process is to gain an understanding of children’s ideas about games and how games give them a sense of satisfaction. In this, symbols representing iconic, abstract, or metaphorical topics related to the research goal work best (Gagné & Deci, 2005; -N. Sanders & Stappers, 2012). Symbol probes are effectivity tools, as they can engage participants to express themselves in a short time. In this project, solving the problem of low engagement with the application cannot be based solely on rational and logical reasoning – emotions have a vital significance (Norman 2004). Symbol probes can trigger emotional connections which can be used to analyse pleasure. In the digital interactive design field, the pleasure factor has attracted much attention when applied to enhance the UX.

Scenarios and Personas

According to Hanington and Martin (2012) in Universal Methods of Design, “A scenario is a narrative that explores the future use of a product from a user’s point of view” (p. 152). They further define it as “a believable narrative” (p.152), since it is meant to represent a person’s future experience engaging with a product. Writing scenarios is to make design ideas explicit and concrete so the design team can empathetically envision the future ways in which the product is likely to be used. By referring to real scenes, scenarios can augment actual human daily activities (Hanington & Martin, 2012).

Personas and scenarios are two methods that focus closer on the quality of reality.

According to Hanington and Martin (2012, p. 132) in Universal Methods of Design, “Personas consolidate archetypal descriptions of user behavior patterns into representative profiles, to humanize design focus, test scenarios and aid design communication.” They further state that “For user centered design, you need to understand people”, and thus, creating personas is described as an effective way to do this.

These two methods – scenarios and personas – emphasize the actual and practical experience in the design process and are useful for clustering similarities in forming synthesized, aggregate archetypes.

3.3 Prototyping

According to Hanington and Martin in Universal Methods of Design (2012), “Prototyping is the tangible creation of artifacts at various levels of resolution, for development and testing

process, it provides the opportunity to represent, critique and reflect on the design concepts. In the testing section, three testing directions were chosen and integrated as one prototype in Workshop Three for gaining a whole view on the gamified system in the healthcare context. In this project, prototyping acted as a checkpoint in which the feedback from different perspectives, including those related to cognition and pragmatic actions, can contribute to the exploration of the possible interactive digital styles within the healthcare field.

Wireframes

Wireframes is a low-fidelity version of a user interface. It could not be use as a

representation of the real screen. Through the wireframes, the testers could focus more on the functionalities that wireframes show. Since the aim of wireframes is representing designated functionalities, the tester can concentrate on usability, which is the main benefit of using wireframes in the design concept evaluation stage. It exemplifies the ‘show, instead of tell’ approach. Wireframes synchronize the checking points in its visualization where the designer could gain insights about scenarios through observing users behaviour. In addition, it’s simple-to-use and time-saving characteristics make the testing preparation process efficient.

Flowcharts

As visual support, flowcharts are regarded as a visual representation of a process and mind map. The flowcharts uses for visualizing complex processes and structures; creating value stream and data flow diagrammes; and identifing bottlenecks or process optimization opportunities. The visualized representation of the process of displaying data in details contribute to understanding a complex structure. In this project, Flowcharts were used as a communicator and analysis tool by visualizing the wireframes structure for depicting the multiple steps and routes within interactive system. It was used as a checkpoint in this project aiding the deeper-level analysis of children with diabetes and their behaviour according to the designated interactive patterns (https://www.smartdraw.com/flowchart/).

Storyboards

Storyboards are used as a way of generating empathy so the design can determine if what they are designing is realistic (Hanington & Martin, 2012). According to Hanington and Martin in Universal Methods of Design (2012, p. 170), “Storyboards can help visually capture the important social, environmental, and technical factors that shape the context of how, where, and why people engage with products”. In this project, storyboards were embedded in the wireframes testing process to review the rationality of the interactive process design. The main reason for using storyboards is to determine the affect on the target audience and to potentially optimize any design features related to the emotional connection theories applied within the digital product’s design. Hence, storyboard chose to embed in the prototyping process for understanding users’ reactions and design possibilities.

4. Project Process

4.1 DiabetesNinja user-experience discussion

Figure 8. DiabetesNinja user information map

Figure 8 shows a DiabetesNinja user information map. Referring to the screenshot with the number 1 in orange above, four options are available that list the functions embedded in the application: ‘Register blood sugar’, ‘Calculate carbohydrates’, ‘Calculate insulin quotas’, and ‘New note’.

1 Register blood glucose

Users can click the button ‘log blood sugar’ (‘logga blodsocker’) and register their blood sugar data. The login value can be found on the performance graphs on the overview page (front page). The graph helps users visualize their blood sugar over time (3h, 6h, 12h, 24h), which helps the users create a correlation between several blood sugar numerical values.

2 Calculate carbohydrate

The ‘Calculate carbohydrate’ function helps users record and calculate their taken

calculating the carbohydrate value. Users are offered three options when they click on this button: (1) register carbohydrates by choosing right portions of food, (2) register the right amount of carbohydrate directly themselves (this requires users who have

knowledge of food nutrition), and (3) save favourite menus and give them labels for easy registration later.

3 Calculate insulin quotas

On the ‘calculating insulin’ page, users can use the formula to calculate and view the suggested insulin dose according their blood sugar level and taken carbohydrate.

4 New note

The ‘New note’ function is designed for users to take notes on the details of daily life, for example, activities, food, blood sugar value, et cetera. No instructions are given on how to use it.

As the main functions, the ‘Register blood sugar’ and ‘Calculate carbohydrate’ buttons are listed above the other two functions. Given that it is important for children to register data regularly and also precisely, two features are embedded in DiabetesNinja to remind users:

• A regular daily notification system.

• Performance graphics on the front page that provide visual feedback about the user’s blood sugar level. According to feedback from the Bant application, visualized data can contribute to users’ motivation because the users gained insights about their SMBG (Self-monitoring of blood glucose) data.

From Figure 8, we can also see it takes five steps (i.e. five clicks) to register the carbohydrate value. In the third step, users have three options, and one is that users can directly register data if they know how many carbohydrates they have taken, or the users can choose the ‘register food’ option whereby the page will jump to another page where the users can find out information about food or choose to pre-save a meal option for direct registration. Given that the users are children in this case, they will have little knowledge of the carbohydrate values of the taken food and will generally choose ‘food portion registration’. Figure 7 also shows three more clicks after choosing ‘register food’, children can input the data on the condition that they know six kinds of units in food calculation. These six units are Deciliter, Gram, Piece (Styck in Swedish), Portion, Packet, and Disc (Skiva in Swedish).

The description shows that 7–12-year-old children find it difficult to use DiabetesNinja and register data, both in terms of the knowledge requirements to register food and the registration steps.

4.2 Workshops

Following the double diamond design process, three co-design workshops were arranged to gain gradual and deeper insight into how children can be motivated to use DiabetesNinja. The series of workshops were conducted to get children’s opinions about the gaming

elements; however, it was also important for the participants to feel respected and secure as they participated. Therefore, in addition to a consent form building trust, co-design activities were organized and carried out in a way that was as enjoyable and mutually beneficial as possible.

As mentioned in the introduction section about GDPR, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 2018), a consent form was prepared for each workshop to obtain the participants (i.e. David, who is a representative from DiabetesNinja, and the children’s guardians) consent to take part in the workshop and to give information about any risks that may be involved. Considering participants’ limited knowledge of design and design research, the language of each consent form was written in easy-to-understand, plain language.

4.2.1 Workshop One – problem definition

In the DiabetesNinja context, caregivers play a vital role in the daily life of children with type 1 diabetes. They act both as guardians and reminders who make sure the children’s blood sugar value is at the normal level. The caregivers’ behaviour has a direct effect on children’s attitudes towards diabetes and their use of DiabetesNinja. Caregivers’ expectations and behaviours are essential materials for design research. The ‘human-centered’ design

discipline highlights the “occasions where the designer could gain deep insight into the social context they are looking to serve, creating innovative new solutions rooted in the actual needs of people” (Firm, 2015, p. 19). With the aim of gaining a view of the DiabetesNinja social context, the first workshop focused on clarifying the design context and the company’s vision.

Workshop process

After a brief introduction of DiabetesNinja, various stakeholders will use this application to support diabetes type 1 children in Sweden, for example, parents, teachers, coaches and others. Given that certain potential stakeholders (i.e. teachers, coaches, friends, siblings and others) cannot participate the workshop, we decided to use and redesign the Starburst and Role-play methods in Workshop One to gain an understanding of the caregivers’ motivation from the DiabetesNinja perspective. In the workshop, David, who is a DiabetesNinja

representative, played the roles of potential stakeholders and shared his ideas. The opinions and discussions from the workshop will be used as material to support more understanding of the design context.

The DiabetesNinja representative, David, is also a project manager. He participated in the first workshop, and it lasted for 35 minutes. In the workshop, my colleague and I

collaborated and shifted roles from that of a note-taker to that of a facilitator who elaborates the procedure and leads David in articulating his opinions.

Figure 9. Workshop One – Starburst method visual material

Results and findings

The table in Figure 10 illustrates detailed contents by following the ‘Why? What? Who? Where? When? and How?’ template from the company’s perspective.

Results from Starburst

The questions below were part of the material used in the workshop process, and the answers were provided by David, the DiabetesNinja representative.

1. Why build up the DiabetesNinja application?

The DiabetesNinja app will be easier and better at helping children who have

diabetes learn to live with the disease and feel safer. Furthermore, adults around the child should also be able to help and support the child by using the app.

2. What functions could DiabetesNinja have?

The main function of this mobile app is used for registering carbohydrate intake values and blood sugar values to help calculate insulin dosage. It should also show registered values over time.

3. Who is the end user?

The app’s target group is children up to age 12. 4. When do end users use this application?

The mobile app will be used in school and leisure time. 5. How to improve the UX?

The application will help children better and more easily help them manage their daily life with diabetes.

6. How does this application launch?

This application is started from a software and technology perspective.

Figure 11. Workshop One – Starburst method outcome

Results from the role-play

a. The motivation for parents to use this application is that they are able to feel calm, safer and happy about their child.

b. Coaches are sometimes referred to as physical exercise teachers in school. For coaches, DiabetesNinja is a tool for understanding a child’s physical status which can then support their decision-making regarding physical activities. It is important that coaches make gooddecisions about physical activities for diabetes type 1 children and make them feel “the same as other children”.

c. Teachers have a similar reason as coaches for monitoring a child’s physical status by being able to see their blood sugar data.

d. Children with type 1 diabetes can feel proud and build up their self-esteem by using this application.

e. Siblings and friends have similar motivations in that they can learn more about diabetes and what living with this disease entails.

Findings

The starburst method was not applied in an assigned way to generate questions, but it

nevertheless helped stakeholders reviewing the company vision and clarify the long-term and short-term goals of improving this application. The company vision is that it wants the application to not only help children to cultivate their habits in living with diabetes but also assist caregivers in supporting the children’s daily life. In addition, the application can raise other social groups’ awareness about the disease, which can contribute to showing care and understanding to children diagnosed with diabetes.

The role-play method has elaborated the service journey possibilities in the following ways:

• Parents, teachers and coaches can access the data that child has registered. • The application can be used as a tool for assisting teaching.

• The application can be used to support children with type 1 diabetes live with the disease and help build their self-esteem. It should also be a cool application that they can show to their friends.

• The application can play a role in spreading knowledge so that more people can understand diabetes and gain the knowledge to properly support those with diabetes.

Workshop One showed that DiabetesNinja has two main functions: First, it is a tool using for managing and supporting the daily lives of children with type 1 diabetes. And second, it has the function of being able to positively influence other social groups by showing diabetes in a fun light.

4.2.2 Workshop Two – children’s attitudes and behaviour investigation

The second workshop was conducted in order to gain the insights and attitudes of children with type 1 diabetes when using DiabetesNinja. Workshop Two was a collaboration with two children, one 6 year-old and one 10 year-old. It is worth noting that, in this workshop, given that one of the participants (the 6 year-old) is out of the target age range (7–10 years), the research result of the workshop would be widened to take into consideration their different knowledge levels, and wider design possibilities would be given to the 7–10 year-old age group.

Two approaches – user experience and emotional pattern – were implemented in obtaining the children’s opinions and attitudes on the functionalities of DiabetesNinja. The emotional pattern is used as an instrument to reflect upon users’ journey understanding their

experience towards functionalities. Besides, game elements related materials are prepared as probes for figuring out children’s attitudes towards game and their ideas about game elements in DiabetesNinja context.

The following are the three research directions for Workshop Two:

1. How do children use DiabetesNinja? How do they experience it and feel when using it? 2. How do children connect diabetes with different objects? How do they understand

their disease? What are their attitudes towards the disease?

3. How do children react to the gamified elements? What motivates them to play digital games?

Workshop process

Workshop Two lasted 2.5 hours, and four tasks were prepared in a sequence to explore the users’ experience, opinions and desires. Given that the participants are children who only understand Swedish, Kyösti facilitated the workshop in Swedish.

The two participants are children with type 1 diabetes. Each child participated in the workshop with a guardian.

The first task is an interview-based activity in which children need to make

movements between two words on the floor as they answer questions. Three groups of adverb pairs expressing degrees of certainty, difficulty, and frequency were

printed out and placed on the floor: ‘yes and no’, ‘easy and hard’ and ‘always and never’. The first task needs to be easy to understand and interesting for the children to willingly participate. Given that the children are doing a physical activity, this may help with motivation and thus lead them to successfully complete the task. In

as visual material to help the children understand the questions: ‘Log blood sugar’, ‘Calculate carbohydrates’, ‘Calculate insulin quotas’ and ‘New note’ (in Swedish:

‘Logga blodsocker’, ‘Beräkna kolhydrater’, ‘Beräkna insulinkvoter’ and ‘Ny anteckning’). In order to understand children’s actual attitudes towards

DiabetesNinja, the task was designed to find any consistencies between their cognition and relevant behaviours. The children needed to answer questions orally, yet at the same time, make movements between words as a way to answer the same questions.

Figure 12. The design process – printed visual material as selected options

Figure 13. The design process – children answer questions by moving between two words

The second task was based on the ‘a day in the life’ method, which aims to discover more about the children’s daily activities as the context for supporting the

understanding of how the application is used. An A3-sized paper was designed with the symbol of a sun and moon positioned at each end of the timeline. Pre-notes about general activities were written down to serve as reminders. In addition, two research questions were prepared in order to guide the understanding of the

children’s daily activities, or more specifically, to help determine when and how they use the application.

Figure 14. Design process used during the second task

Figure 15. Design process – children write down their ideas about daily activities.

The third task was designed to gain a picture of the children’s perceptions towards games and to investigate their attitudes towards game elements in healthcare applications. The idea is to inspire children and make them feel free to talk about their ideas relating to gamified elements. The third task started with the children choosing what they like in the box. Then they were encouraged to share their ideas according to what they chose. We prepared a box with various visual game elements for the children to choose from: avatar, badges, leaderboards, performance graphs, pictures of parents, teammates. A note with three questions was delivered to children to prompt them to express their ideas:

1. Why did you choose this THING?

3. How will you use the THING to notify yourself of using the application?

During the process, the children were invited to take notes about their thoughts.

Figure 16. Design process – materials used during the third task

Figure 17. Design process – the workshop process

The fourth task. The fourth task was divided into two parts. The first part was designed for gaining children’s ideas on metaphorical, iconic, and abstract objects as well as understanding how children can connect the material with diabetes. We prepared three materials: a plant, an egg, and bar graphs. The bar graphs illustrate the proportion by using three colours: green, orange and red (see Figure 17). A question was prepared to explore the children’s ideas: How do you see these three objects in the diabetes context?

The second part was designed to get the children’s opinion on the Tamagotchi feature. A storytelling task was formulated through the integration of scenarios and personas. Children were then encouraged to make a character and formulate the character’s life. In the process, Kyösti wrote down some possible open questions so that the children could employ those aspects in their expressions and

demonstrations: Who is he/she? What does she/he look like? What does he/she eat? What does he/she like to play? Does he/she work? As the last task in the workshop, telling or making stories made the process affinitive and exciting in interacting with children.

Figure 18. Design process - used during the fourth task

Figure 19. Design process – a facilitator writes down the open questions.

Results and findings Results

Results from the first task

According to the activities, we understand that:

1. Both children did not like using the DiabetesNinja application. 2. Both children need to be reminded to use the application.

3. In general, the 10 year-olds thinks it is easy to use the application, while the 6-year-old child thought it was somewhere between easy and hard.

4. Both the children think the blood sugar function is the easiest function to use. 5. The 10-year-old child could not decide which function was the hardest to use,

6. The 10 year-olds thinks the carb register function is the most important function. The 6-year-old participant did not give any immediate reaction, but his

movements showed hesitation.

In general, the 10-year-old participant had quicker reactions than the 6-year-old. For some of the questions, both children did not have any clear answers. The workshop process also showed that the 6-year-old child sometimes did not understand the questions. His movements reflected his hesitation to answer the questions, and he sometimes mimicked the 10-year-old child’s behaviour. The workshop resulted in

the understanding that it is more difficult for 6-year-old children to use DiabetesNinja.

Both children reacted more quickly when came to questions that can be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’, ‘easy’ or ‘hard’. In general, it took time for both the children to decide how to answer the questions. This could be because it is hard for children to make just one decision when there are four options to choose from. Task one reveals that there is a cognitive difference between ages. Though both children do not like using DiabetesNinja, they nevertheless understand the

importance of using the application. They both have knowledge about diabetes and understand that the carbohydrate index recording is important for living well with disease.

When comes to the different the younger children’s choice is affect by others’ decisions.

It takes longer for the younger child to understand questions in general. In this case, it’s good to bear in mind that when organizing workshops for children, the

participants’ cognitive ability is a factor that could affect the efficiency of result. It is hard to tell whether the 6-year-old child’s slower reaction time was because he did not understand the question or because he did not know the answer.

Results from the second task

With help from the visual material assistant, both children made notes about their regular day at school. From the notes, we see that both children have a regular school life during weekdays. They have breakfast, lunch and dinner at the same times and take part in regular physical activity. Both children eat lunch at school during the week. Figure 20 shows that the younger boy goes to bed one hour earlier than the 10-year-old child.

1. For the 6-year-old child, the guardian is the one who helps him with disease index register. It takes approximately 5 minutes each time.

2. The 10-year-old child registers the data himself. He mentions that he always forgets to take his insulin until he has breakfast. It takes 5 minutes for him to compete registration. Sometime he needs someone to remind him to register relevant data.

Figure 20. Design process – ‘A day in the life’ method

The notes from the ‘a day in the life’ material show that the children have a similar school schedule. Compared to the 6-year-old child, the 10-year-old child has more awareness about using DiabetesNinja. According to the notes, August always forgets to take insulin until he has breakfast. From this, we can see the cognition load of living with diabetes is heavy for children. The reminder system is important for supporting children to follow a strict system to register the data and monitor their physical status in a logical order.

Results from the third task

The 6-year-old child, Theo, picked up two objects from the box: a toy penguin and a

Lego character. He likes to play games, and he also likes animals. he told us he likes to build up Lego components. He thinks the Lego character and penguin can be ninjas in DiabetesNinja.

The 10-year-old child, August, picked out three objects from the box: metal badges,

leaderboards, and a game friend card. He told us that he would like to receive a metal badge when he finishes the task, and in the process, shows interest in the metal badge necklace. He also picked up leaderboards from the box because he thinks leaderboards should be the part of the app.

When comes to the question of how the user wants to be notified by DiabetesNinja, the child picked up the friend card as his first choice. He explained that because he spends much time with his friends, he would like to receive notification from them.