This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: Title

“To live until you die could actually include being intimate and having sex”: A focus group study on nurses’ experiences of their work with sexuality in palliative care

Running title

Sexuality in palliative care

Authors

Emma Hjalmarsson & Malin Lindroth

Emma Hjalmarsson, RN, MSC

Centre for Sexology and Sexuality studies,

Faculty for Health and Society, Malmö University, S-205 06 Malmö, Sweden

E-mail: hjalmarsson.emma@gmail.com, Phone: +46730524251

Malin Lindroth, RN, PhD

Centre for Sexology and Sexuality studies, Faculty for Health and Society,

Malmö University, S-20506 Malmö, Sweden

E-mail: malin.lindroth@mau.se Phone: +46708446023

ORCID-id: 0000-0002-5637-5106

Funding and Conflict of Interest

The study did not receive any funding, and we declare no conflict of interest.

MS. MALIN LINDROTH (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-5637-5106) Article type : Original Article

“To live until you die could actually include being intimate and

having sex”: a focus group study on nurses’

experiences of their

work with sexuality in palliative care

Aim: The aim of the study was to examine nurses’ experiences of working with issues of sexuality in palliative care.

Background: Sexuality has value for human lives and relations and is important for one’s overall well-being throughout life. Guidelines for palliative care state that sexuality should be addressed. Previous research shows that the inclusion of sexuality in general healthcare is deficient, and there is a knowledge gap on how sexuality is addressed in palliative care. Method: Within a qualitative design, the empirical material was obtained through three focus group interviews with eleven registered nurses working in palliative care. The interviews were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Result: Nurses experience that sexuality has an indistinct place in their work, ‘sexuality’ is a word difficult to use, and differing views are held on whether it is relevant to address sexuality, and if so, when? Although they have experiences involving patient and partner sexuality, which is viewed as sexuality in transformation during the palliative care process, nurses seldom explicitly address patient or partner sexuality. Despite the lack of knowledge, routines and organizational support, they acknowledge the importance of addressing sexuality in palliative care, as they express that they want to do right.

Conclusion: Overall, nurses appear to follow differing cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic scripts on sexuality rather than knowledge-based guidelines. This underlines the importance of managers who safeguard the adherence to existing palliative care guidelines where sexuality is already included. In this work, it is important to be aware of norms to avoid excluding patients and partners that differ from the nurses themselves as well as from societal norms on sexuality.

Relevance to clinical practice: The results can be used as a point of departure when implementing existing or new guidelines to include and address sexuality and sexual health needs in palliative care.

Introduction

“Nowadays there are only a few moments when I do not think about death. When I am not besieged by what is coming. When I make love is one of these moments. Then everything else ceases to exist. Then we disappear in a bundle of bodies.” (Gidlund, 2013, p. 260)

The above quotation is from an autobiography written by Kristian Gidlund, where he writes about his experience of terminal cancer. In the quotation, Gidlund combines two societally taboo areas: sexuality and death. In addition, he highlights how sexuality can be highly important for an individual’s well-being in the palliative phase. This paper concerns this understudied area: sexuality in palliative care.

Sexuality is of value in human lives and relations and important to overall well-being throughout the life course (Flynn et al., 2016; Starrs et al., 2018). The World Health Organization describes well-being in relation to sexuality as sexual health, where sexual health is a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality (WHO, 2006). Depending on the person and the illness, the importance of sexuality, and what defines sexual health and well-being varies between individuals. However, sexuality, or sexual health needs, do not cease to exist due to serious illness (Redelman, 2008; Rice, 2000). How individuals experience sexuality before the illness, preconceptions on how to behave during serious illness, and support from one’s partner are all factors that influence sexual health and well-being (ibid.).

Nurses worldwide are involved in palliative care, and if this care is carried out holistically, the patient’s and partner’s sexual health needs should be addressed (Higgins,

Barker & Begley, 2006). In the context of this study, which is Sweden, palliative care is defined as care with an aim to alleviate suffering and promote quality of life until the end of life (The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, 2013). In a nationwide document on palliative care, it is stressed that all health needs must be addressed in palliative care, including sexual health needs (Cooperation of Regional Cancer Centers, 2016), and this also applies for palliative care in the United States (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2018). In national guidelines on palliative care in countries where care is organized in a fashion similar to Swedish health care, the United Kingdom and Australia, sexuality or sexual health needs are not specificially highlighted, but holisitic assement is (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019; Palliative Care Australia, 2018). Nevertheless, sexual orientation is mentioned in the Australian national guidelines, and it is stressed that “palliative care services must provide a safe environment where LGBTI people with life-limiting illnesses can live and die with equity, respect and dignity, and without fear of prejudice and discrimination” (Palliative Care Australia, 2018, p.12). However, little is known about if and how nurses work with sexuality in palliative care. Therefore, this paper aims to investigate how nursing practice adhere to palliative care policies

Background

Patient and partner experiences of sexuality during terminal illness

Research about patient and partner experiences of sexuality during terminal illness is scarce. When patients in palliative care in Canada were interviewed on sexuality and sexual health needs, sexuality was an important aspect in their lives, even during their last weeks and days (Lemieux et al., 2004). During terminal illness, sexual expressions changed and encompassed different areas, but was centered on emotional relationships as well as hugs, kisses, touching hands and deep eye contact. These expressions were a key component in the perceived quality of life, and for some terminally ill persons, sexual intercourse was the preferred sexual expression, but for others, sexual intercourse was no longer important (ibid.).

Sexual well-being among surviving partners has also been studied. In an interview study from the Netherlands, surviving partners describe sexuality during their partners’ illness and dying (Gianotten, 2007). The reasons for sexual activities were pleasure-seeking, love, relaxation, distraction, grief and anger. There was great variation in the needs

of surviving partners. For some, expressions of sexual emotions became more important than physical expressions (e.g., sexual intercourse). Some were content with holding hands, hugging and sleeping together, and some surviving partners stated that sexual expressions were a way of clinging to life (ibid.), like in the initial quotation from Gidlund at the beginning of this article. A British study highlights that the relationship, including sexuality and intimacy, between the dying person and their partner is important (Taylor, 2014). In the palliative phase, couples handled a separation from their love relationship and experienced feeling rejected, losing spontaneity, and lack of mutual sexual and intimate needs. The couple’s sexuality was affected by a variety of factors such as medical treatments, bodily changes and the impersonal effects of medical equipment. However, some couples could also experience a new bond and a new closeness (ibid.). A recent review explored the prevalence of incorporating sexual health in the symptom screening and assessments of palliative patients (Wang et al., 2018). Eleven papers were idientified and results showed that discussions about sexual health, functioning, and intimacy were rare, despite being a service that both patients and their partners wanted. Health care professionals stated lack of training, own life experiences and discomfort to the topic sexuality as barriers to iniate conversations on sexual health (ibid).

Addressing sexuality within (palliative) health care

In contrast to the patient’s and partner’s sexual health needs in palliative care, research on nurses’ (lack of) addressing sexuality in different nursing contexts is abundant (Hautamäki et al., 2007; Hordern & Street, 2007a; Reese et al., 2017; Saunamäki & Engström, 2014; Saunamäki, Andersson & Engström, 2010; Stead et al., 2003). One reason for this negligence could be that nursing curricula seldom emphasize sexuality and sexual health needs, and as a result, the nursing students are unprepared for this work (Areskoug-Josefsson et al., 2019; Blakey & Aveyard, 2017). Concerning palliative care, it has been reported that nurses do not consider or address sexual health needs among severely ill patients (Benoot et al., 2018; Hordern & Street, 2007a; Lemiuex et al., 2004; Stead et al., 2003). However, patients in palliative care do want support from health care staff on how to handle the impact their illness has on their sexuality and intimacy (Hordern & Street, 2007a; Lemiuex et al., 2004; Vitrano, Catania & Mercadante, 2011; Wang et al., 2018). This lack of information and communication from health care staff on changes in sexual health and well-being could lead

patients to believe that their experience is not valid, which may add worry and make it even more difficult for them to raise their concerns (Hughes, 2009).

To summarize, patients in palliative care and their partners have sexual health needs, as sexual well-being does not cease to be important when a person is dying. However, nurses appear to avoid this area. In order to safeguard holistic care and the patient’s and partner’s rights to sexual health, this avoidance needs to be examined.

Aim

To examine nurses’ experiences of their work with sexuality in palliative care.

Methods

Design

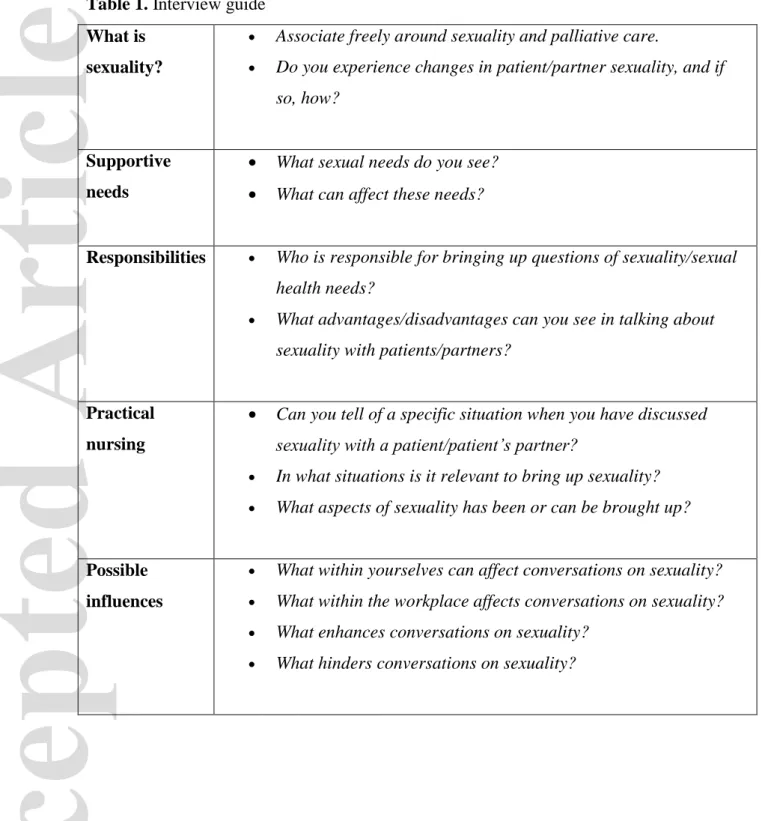

The study had an interpretive approach, in which nurses’ experiences were seen as multifaceted, dependant on context, socially constructed and subjective. By using a descriptive, qualitative and inductive design, and a purposeful sampling, experiences were sought through focus group interviews. The method was chosen to capture collective understandings (Kitzinger, 1996; Krueger & Casey, 2014). To ensure that areas important to the aim were broached during the interviews, a semi-structured interview guide with various questions departing from five themes was constructed, see Table 1. The study was guided by the COREQ checklist (Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, 2017), see Appendix 1.

Table 1 about here please

Data collection

A purposeful sampling strategy was applied, and nurses working at specialized palliative care units were sought. Nurses working with palliative care in other care units (e.g. regular hospital wards) were excluded. Although they also have an obligation to address sexual health, nurses specialized in palliative care were of particular interest. Managers at eleven different county-run (i.e. not private) palliative care units in the south of Sweden were identified on-line and contacted, and seven responded. After they had been given oral and written information about the study and agreed to take part, they spread information about the

study at different care units. Three units approved, and three different interviews were arranged and held with eleven (n11) nurses between November 2018 and January 2019. One focus group consisted of four nurses working in a palliative home care team, another group was of four nurses working at a palliative care ward, and the third group was a mix of three nurses working either with a palliative home care team or on a palliative care ward. The interviews were held in a secluded room during the nurses work hours, with only nurses and researcher present. The eleven nurses all identified as women and were between 25 and 60 years old (mean45). Their experience of working as a registered nurse varied between three and 30 years (mean17), and their experience of working within palliative care varied between three and 20 years (mean12). The focus group interviews were conducted by the first author (an RN with five years of work experience in palliative care studying for a master’s degree in sexology and with no personal connection to the nurses), and each lasted approximately two hours. A tape recorder was used and interviews were transcribed verbatim in connection with each interview. Based on the clinical assumption that sexuality and sexual health could be vague concepts for the participants, each interview started with a vignette where the WHO definitions of these concepts were presented. Under Swedish research governance arrangements, because professionals were interviewed, approval by an ethics review board was not needed nor sought. However, the study followed ethical principles, and all the nurses gave oral consent to participate. The first author stayed after the interviews in case any single participant were in need of more time to discuss or reflect. Due to time contraints and to rich data it was decided that three focus groups were sufficient to reach the study aim.

Analysis and theoretical framework

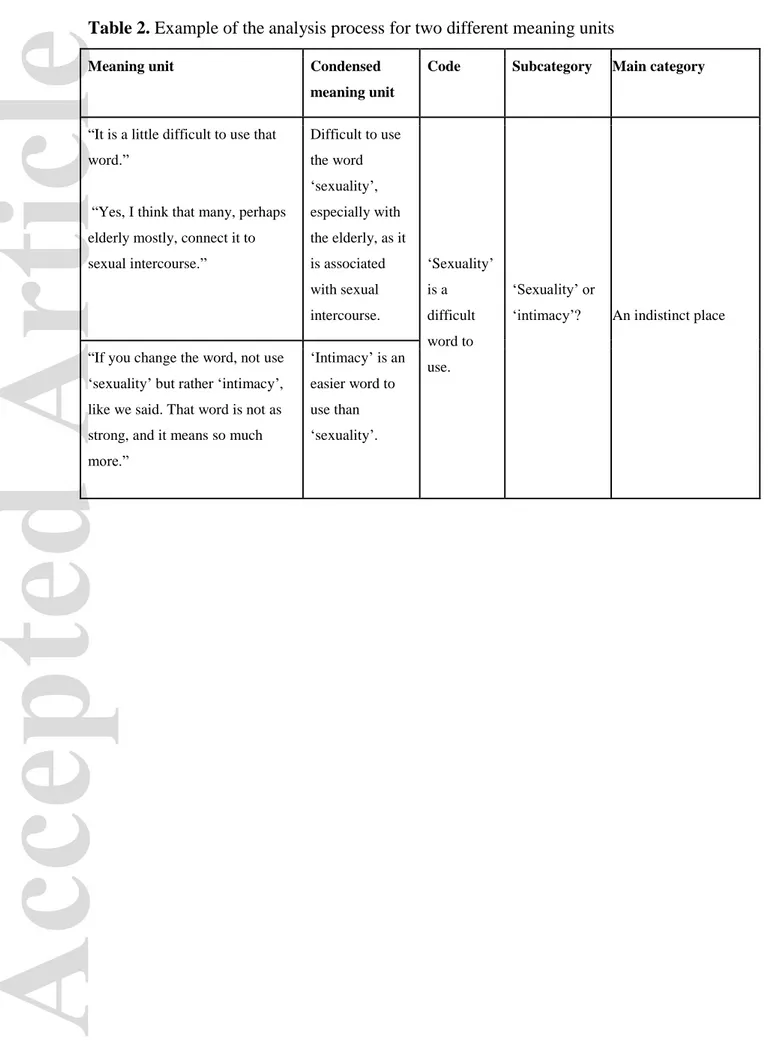

The data were analyzed by the first author using the steps of latent content analysis described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004). Similarities and differences in nurses’ experiences were sought, and meaning units were searched for and labeled with a code. Codes were condensed and made into subcategories that later were grouped into main categories, see Table 2.

Table 2 about here please

The analysis and emerging results were continuously discussed with the second author (an RN and PhD with limited experience of working in palliative care). The analysis resulted in three main categories and seven sub categories involving the nurses’ experiences of their

work with sexuality in palliative care, see Table 3. The results are presented with supportive quotations from nurses who have been given a fictive name.

Table 3 about here please

Having a point of departure where experiences are seen as socially constructed, the theory on sexual scripts (Gagnon & Simon, 2015) will be used for understanding the results. Sexual scripts (i.e., manuscripts) dictate how sexual behavior and activities are created in cooperation between people and how individuals incorporate societal views on sexuality into their own and thereby create societally acceptable sexual expressions. Sexual scripts are context dependent (i.e., situation, time, culture, gender, age, gender and class) and matter in the constant creating of and acting upon what is seen as “acceptable sexuality”. Sexual scripts can be divided into three levels: cultural (societal norms and values, laws and policies that shape individual freedom), interpersonal (how individuals interact with, for instance, friends, family and colleagues), and the intrapsychic (individual specifics that more or less consciously guide individuals). The three different levels constantly depend on and interact with each other; therefore, sexual scripts are in a constant flux (ibid. ).

Results

An indistinct place

Nurses’ reasoning on sexuality in palliative care show that words matter. The word ‘intimacy’ is seen as less charged and easier to use than sexuality. Opinions differ on if sexuality is a relevant area for nurses in palliative care, and the advantages and disadvantages of working with sexuality are mentioned. These ambivalences are interpreted to reflect that sexuality in palliative care has an indistinct place.

Sexuality or intimacy?

The nurses reason on what sexuality in palliative care can entail and agree that sexuality is innate in all humans, even those who are seriously ill. Sexuality is seen as a major part of many people’s lives and related to quality of life. Many say that they regard the concept of sexuality as broad, and this can include closeness, touching, intimacy and love. These are all

important aspects in palliative care and do not necessarily include “having sex”. However, some claim that being sexually active is essential:

By focusing on life and your functions, closeness and intimacy can be what makes you feel better in the life that remains. […] To live until you die could actually include being intimate and having sex. (Eve)

The word ‘sexuality’ and its meaning is constantly discussed. The word is seen as difficult to use in practical work with patients and partners, and thus the word ‘intimacy’ is seen as more appropriate:

Like you said, ‘intimacy’. I´d say that is easier to work that with than ‘sexuality’. ‘Sexuality’, I feel like – no, that is nothing we work with, but the other [the word ‘intimacy’], that feels more reachable, considering our patients. (Helen)

Sexuality is said to differ from other difficult or sensitive subjects that nurses regularly discuss. The nurses are confident when talking about other intimate and private subjects with patients and partners (e.g., urination, defecation, anxiety, loss, death), but sexuality tends not to be one of these subjects:

We are pretty used to discussing other difficult subjects – that preparedness I do hope we have. But it is different to talk about sexuality compared to anxiety, fear of dying, and other losses. (Eve)

In those areas [other difficult subjects], we are more trained. (Sophie)

Relevant or not?

The relevance of working with sexuality is seen in various ways among the participants. That palliative care has an early and late phase is mentioned, and some nurses say that the need of support for sexual health may be more common in the early phase:

They are so far gone in their disease, the ones who come here. I figure it [sexuality] is not on their minds. (Suzanne)

Yeah, but we also have patients who want to go home, who are not that sick, who come here for pain relief and then return back home. (Aida)

The issue of relevance is also connected to whether palliative care nurses can offer any help in the area of sexuality or not. Some say there is not much to be done, others that there is. Some mention the partner, and that including the partner can broaden the concept of sexuality in palliative care. It is also suggested that including sexuality can give patients hope:

But, I experience that patients can feel hope when you try to promote what is doable – what the patient really can do. That you don’t only focus on losses, on what isn’t doable, and that life is ending. (Eve)

Depending on what is included in the concept of sexuality, the responses vary regarding what is relevant for palliative work. Some nurses say that their palliative team does raise the issue of sexuality, but not sexual intercourse, as “those days are gone”. Others state that they do not connect sexuality to severely ill persons, and therefore, have not considered it relevant to palliative care. This is discussed in general by Suzanne, who states, “I believe every other person thinks that, in relation to death, sexuality is not present”.

Some nurses stress that before the focus group interview, they had not considered sexuality to be important in palliative care, but that their conversation with others made them realize that it was:

My first thought – ‘sexuality in palliative care, what?’ I hadn’t thought about it before, that it was even an issue. But, I have started to understand that it can mean different things, and that it absolutely is, that it is an important topic. I hadn’t thought about it before, it’s good with an eye-opener. (Sophie)

In contrast, there are also insecurities regarding whether it is relevant at all to work with sexuality in palliative care. Thoughts that staff do not have anything to do with patient sexuality, since it is private, are shared by some of the nurses:

I feel it is not my business to address these things. I feel that now you are entering into something that is not your business. But, then again, sometimes you might open a door, to just give some advice. It could be like that too. (Aida)

Another reason for not addressing sexuality is fear of causing the patient grief, a fear that sometimes includes worries that the nurse–patient relationship may be compromised in some way:

I think that many [patients] might find it demanding – this sex thing. That we come and ask, they might feel: ‘Ah, but what the heck? That’s the last thing on my mind. Don’t you come here and…’, I’ve no idea, but it might be like that. (Petra)

A transformation

Nurses’ conversations reveal that they see major changes in patient sexuality during palliative care. They reflect upon how this might affect patient and partner relations and on what sexual expressions patients have. They discuss a sexuality in transformation.

Patient and partner relations

The illness itself, and treatments connected to it, are seen to have a major impact on patient sexuality. Bodily changes (e.g., dry mucus membranes, smells, ostomy, menopausal symptoms, oral fungus, lesions, hair loss and swelling) are mentioned. Nurses say that these bodily changes might make the patient feel ashamed of their body, which in turn might lessen or altogether stop the inclination to have sexual interaction.

It might be connected to their symptoms. I think there might be a lot of shame. That you don’t want to show your body. You don’t want to … I mean, if you have an ostomy, or a swollen abdomen, it might be that you don’t want to show your body. (Petra)

Yeah, and smells that change. That makes you want to keep your partner at a distance. The whole body changes. (Suzanne)

Other illness-related problems (e.g., pain, anxiety, nausea, fatigue, numbness, stress, frustration, loss of control and being dependent) are brought up. Additionally, having tubes and other medical equipment connected to your body, not sharing your bed with your partner and being at a palliative ward are seen to hinder expressions of sexuality. Nurses also reflect upon that both patient and partner can abstain for being close due to fears of damaging the body, of pain, or of contagiousness.

Many might think of cytostatic: ‘It might be dangerous. Maybe it’s not safe to be close.’ (Sophie)

Yeah, and ‘when they take care of the waste, they have aprons on. It might be contagious’ – like that. (Annette)

When patient and partner sexuality transform, nurses believe that new expressions of sexuality develop, for instance, to feel intimacy through closeness and touch, and they have seen these expressions often. Changes for the partner are brought up, and the nurses believe that partners can feel many emotions (e.g., guilt, lack of attraction to the dying person, loss of sexual activity, or fear of causing pain). The partner’s sexual needs are described as more extensive than that patient’s and as something else:

I can imagine that they [partners] have even more questions than the patients have. I mean, they live on. The patient has moved into something else, but the partner and all their needs are still the same. (Petra)

This inequality in the relation between patient and partner is pondered upon, and it is suggested that the surviving partner and or the patient might feel shame or guilt:

There might be shame and guilt in not feeling desire. Or to feel desire (Eve) I think the healthy one might feel desire, and feel like shit, and that the sick one doesn’t. (Sophie)

Or the other way around. (Annette)

Yeah, exactly – or the other way around. (Sophie)

The question of supporting patient personal hygiene is discussed as both a potential intimacy booster and as the opposite. Some advocate that healthcare staff should assist the patient in matters of personal hygiene, others argue that the partner should. In connection to this, it is mentioned that the relationship between patient and partner can vary, and the quality of the relationship needs to be taken into consideration; for example, some palliative care nurses have met newlyweds and others have met recently divorced couples. The relationship status before the illness is deemed important:

We don’t always know what kind of relationship they have. If they haven’t touched each other for the last twenty years, they might not want to touch each other now. (Aida)

Patient sexual expressions

Participants discuss how patients can, or cannot, express their sexuality. They share different experiences of previous patients who have longed for partner closeness as well as the opposite. To be in palliative care at home is seen as more optimal for sexual expressions, as it is care on the patient and partner’s premises. When receiving care at a palliative care ward, nurses fear that both patient autonomy and sexual expressions are easily overlooked, as nurse Sophie explains:

I’ve been thinking about urinary tract catheters. I had a patient with ALS once, and we thought he should have one. And I was persistent and suggested that it is very convenient. You don’t have to move to go to the toilet, and it is so common. But he didn’t want to. Then someone said – I think it was the counsellor who said, that ‘We don’t know what kind of relationship they have’. And no, I hadn’t even thought about that it could be the reason for why he didn’t want to. (Sophie)

At a palliative care ward, routines prevail, and privacy might be hard to achieve. Some nurses think that this may be the reason why some patients feel strongly about being cared for at home. It is experienced as very rare that patients express sexual health needs, and many

nurses have never experienced it at all. However, it is suggested that sexual health needs do exist, but patients dare not ask and thus seek answers elsewhere:

Perhaps they don’t have the confidence to ask the really intimate questions – the ones they want answered. I think people Google a lot. (Aida)

It is discussed that if sexuality was regularly addressed by nurses like any other aspect of life, any problems could be made visible and support could be offered. Additionally, the risk of letting the patient and partner down by not addressing sexuality could also be avoided:

They might think: ‘No, they are not mentioning it. No, of course you shouldn’t be intimate now that you are ill. Maybe they don’t approve.’ It could create…just because we don’t bring it up. (Annette)

Wanting to do right

The nurses reason on what can be done for patients and what they already do. Hindrances, on both organizational and personal levels are mentioned as well as methods and responsibilities for this work. This reasoning is interpreted as wanting to do right.

Possible and factual efforts

The participants identified many possible efforts that could be made to help (e.g., written information on sexuality, tactile massage, medications for sexual dysfunction, improved ostomy care and relieving fatigue). Some of these efforts are already in place, and during the interviews, they realized that this is part of their work with sexuality. Again, they mention that a central aspect is hygiene so that patients can feel clean, fresh and nice. According to the nurses, this could promote intimacy.

I just think about what we can do. That is, to keep the man and woman tidy. To be nice and good-looking – to be neat. And eliminate the smells a bit. So that when the man visits, you make sure that the woman lying there is proper like she wants to be or perhaps has expressed to us. (Suzanne)

To promote touching and closeness, and to facilitate privacy is also mentioned. Some say they already do promote closeness and advocate the health benefits closeness can bring:

About touching – we know that is important, tactile massage and stuff. And it is also important in the sexual [aspect], without being a sexual activity. And it can be important for the couple to just lie down next to one another. That you inform them that plain skin contact, to pat each other, or spooning, or lying next to one another, it increases endorphin secretion that makes you feel good. One could be even better to inform about that. (Sophie)

Supportive and counselling conversations with patients and partners is also seen as a significant effort. Nurses say that these conversations are already happen, although not explicitly about sexuality. However, one nurse recalls an occasion where sexuality was broached:

There was a patient my age, and we became very close, and could talk about everything. Then one day he tells me, ‘My wife has arranged a baby sitter, and will stay the night, and I have a problem. I have the urinary tract catheter.’ I didn’t ask any questions, just said, ‘Well, that’s not a problem. We’ll just take it out – problem solved.’ And he was joyous. He said, ‘You’ll have to help me take a shower in the evening.’ See, that’s what it was all about. It was as if he was going on a date. It was a big thing for him. Something huge happened in that process. (Aida)

Organizational and personal obstacles

The nurses identify many flaws in their work with sexuality in palliative care, and they repeatedly state that matters of sexuality are not a manifest part of their palliative care – they are not discussed in the palliative team nor brought up by managers. Additionally, a lack of knowledge is mentioned, which they believe may hinder them from actively engaging with the issue of sexuality:

There are so many important things to do that I know how to handle, with medication or whatever. But sexuality – there’s not much I can do. So, then you just suppress the thoughts. (Annette)

The nurse’s personality is also said to be crucial. Many say they are embarrassed to talk about sexuality and lack experience of doing it. They conclude that the personality traits needed are to be responsive, open, brave, respectful, confident and prepared to handle whatever topic that may arise during conversations on sexuality. The quality of the nurse–patient relationship is also mentioned as well as the hardships of talking with patients of sexuality when no one else in the team does. Many say that they do not believe it is the actual conversation topic that is hindering them, but rather the lack of courage to raise the issue:

Just as you all say, if one had been invited to talk about sexuality, I don’t think there would have been any problems at all. It’s just to take that first step. (Suzanne)

Conceptions of gender and age related to sexuality are present during the interviews. In addition, same-sex sexual relationships or transgender or non-binary identities are not acknowledged. A general belief among the nurses is that sexuality differs between men and women; for instance, women are interested in feeling neat, and men have problems discussing problems in general and sexuality in particular. Moreover, different views on age and sexuality are seen. Some say sexual health promotion is more important with younger patients, while others say that age does not affect whether a person is sexually active or not:

But of course, if we are to be more proactive than we are, we have to ask questions because we have no idea what differences there are between a 40 year old and an 80

year old. We really don’t know. It might be the 80 year old who misses it really much. (Helen)

Methods and responsibilities

The nurses say that knowledge about sexuality is lacking and that it should be offered in all nursing education, especially regarding skills on how to discuss sexuality. Some comment that the present interview underlines the importance of the subject and that having a focus group conversation has in itself illuminated an area that otherwise goes unaddressed in their work. They consider themselves inept at working with sexuality and lacking information material and routines. Therefore, the nurses suggest that managers should ensure that work with sexuality in palliative care is carried out by all, as that would make it more clear that it is a part of their job.

Finding the right time to discuss sexuality is discussed – some say that upon admission to palliative care provides the best opportunity for this, while others say that a few days later is more suitable. Raising the topic in connection with personal hygiene is suggested but also dismissed as being degrading for the patient. Moreover, it is underlined that if a patient has a question, the nurse must not avoid it due to embarrassment, lack of time or lack of knowledge. It was agreed that one way to neutralize potential awkwardness for the nurse, the patient and the partner is to explain that this a subject routinely highlighted:

You have to explain that this is something you ask every one – like ‘It’s not only you we are asking. We think everyone should be asked. It’s part of our job’. (Christine)

Although not all agree that sexuality should be broached by the nurse, a common suggestion is to put it in checklists or questionnaires to make sure it is addressed. Some say it is not a nurse’s task but rather the physician’s. Others say that it is a self-evident part of holistic nursing and that the nurse’s position close to the patient is a unique opportunity to address a sensitive subject. Overall, the responsibility is placed on other parts of the caring process and to other care specialties. There is an agreement that it would be beneficial if other care specialties who meet patients in the early stages of the illness addressed sexuality:

I think, these patients, they are so far gone. Maybe it’s different if you work in an early state, like with prostate cancer. Maybe it’s more natural then to talk about it. I’d say it’s included in that care, at least it should be. (Petra)

Discussion

The three focus group interviews with 11 nurses working in palliative care units showed that sexuality had an indistinct place in their work, they experienced that ‘sexuality’ is a word that is difficult to use, and they had different views on if and when it is relevant to address sexuality. Although they had experiences of a patient and partner sexuality in transformation during the palliative care process, it was rare to have explicitly addressed patient or partner sexual expressions or sexual health needs. Despite the lack of knowledge, routines and organizational support, they acknowledged the importance of addressing sexuality in palliative care, and they expressed wanting to do right. Through the application of sexual script theory (Gagnon & Simon, 2015) to the results, nurses, as well as patients and partners, are all anticipated to act upon their own sexual scripts on what sexuality is and on how it is expressed for them as individuals in their social and cultural context. This theoretical perspecitve can help us understand how nurses’ cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic scripts matter and have an impact on their experiences of working with sexuality in palliative care.

The indistinct place of sexuality in palliative care

The ambivalence among the nurses on what sexuality is, and whether or not it is relevant to address in palliative care can be seen as cultural scripts on sexuality in relation to terminal illness that obscure terminally-ill people as sexual beings. This falls in line with research on chronic illness and sexuality (Enzlin, 2014) and points at a double taboo in palliative care (Leung, Goldfarb & Dizon, 2016), where neither sexuality nor death is addressed. However, statements made by terminally-ill people highlight the contradiction: sexuality is an important aspect of being a human, even during the last weeks and days of life (Gianotten, 2007;

Lemieux et al., 2004). In addition, nurses’ avoidance of addressing sexuality highlights that existing policies regarding sexuality in palliative care are not always followed. The results also fall in line with findings that show how preconceived ideas among healthcare professionals influence their willingness to address and advise on sexual health issues (Perz, Ussher & Gilbert, 2013). This indicates that interpersonal and intrapsychic scripts rather than scientific knowledge on sexuality affect the nurses’ work in palliative care.

The finding that one strategy among nurses to address sexuality is to connect sexuality to the palliative care approach (i.e., to focus holistically on life and functions that are still intact) falls in line with the only comparable study found. When Benoot et al. (2018) interviewed nurses individually on their work with sexuality in palliative care, one of their main findings was that nurses were either “holistic inclusive” or “holistic sexuality-exclusive” (p.1590). This indicates that the palliative care approach can be applied to clinical work with patient (and partner) sexuality. However, if a terminally ill person is close to death and has a major loss in functioning, applying this approach can include a risk that sexuality and sexual needs are overlooked. In the words of one of the nurses in our study, if you believe that “those days are gone” and thus implying that sexuality is gone, the dying person is seen as no longer possessing any sexual feelings, needs or urges. In these situations, focusing on the existential aspects of sexuality as innate human traits or abilities can be a solution that is in line with a palliative care approach. Existential aspects of sexuality could include being touched or held, or simply being acknowledged as a person. These are aspects or actions that could be provided by close ones, or by nurses when close ones are not available or part of the palliative care. Nurses need to embrace that sexual health is “a broader concept than sexuality alone and moves past sexual intercourse to include a combination of intimacy, closeness, communication and emotional support” (Matzo, 2010, p.71).That sexuality exists until death is supported by previous research which stresses that people use their sexuality to increase well-being even when terminally ill (Gianotten, 2007; Lemieux et al., 2004).

The transformation of sexuality in palliative phases

The results show that nurses experience a patient and partner sexuality in transformation. They emphasize bodily changes and other illness-related aspects that, in their view, affect sexuality negatively. This reasoning is in line with previous studies on different cancer

diseases where physical changes affect the patients psychologically, which can lead to social withdrawal from, for instance, sexual activities (Galbraith & Crighton, 2008; Helms, O’Hea & Corso, 2008; Hughes, 2008). However, this finding could also indicate that nurses have both interpersonal and intrapsychic sexual scripts that equate sexuality with clean and able bodies. This can be a challenge that hinders them from seeing all patients, especially patients in late palliative care phases, as sexual beings.

The changes in relations between patient and partner and the importance of privacy that the nurses reflect upon during the focus group interviews are in line with previous research on sexuality in palliative care (Bowden & Bliss, 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Gianotten, 2007; Taylor, 2014). The results could also be understood as an example of how the nurses’ sexual scripts on cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic levels imply a partnered sexuality. This warrants caution, as nurses need to acknowledge sexuality even when caring for single people. This is particularly important because previous studies have found that healthcare professionals act upon norms regarding which people are in need of sexual health support and which are not (Hordern & Street, 2007a; Perz, Ussher & Gilbert, 2013).

Wanting to do right and include sexuality in palliative care

The results indicate that nurses want to do what is right despite the lack of training, routines and managerial support, which is in line with previous research where feeling professionally responsible can lead to addressing sexuality despite feelings of uncertainty and fear (Saunamäki & Engström, 2014). Moreover, the nurses’ avoidance to mention the topic and place the responsibility with other professional areas or clinics, and thus setting their own professional responsibility aside, has previously been found (Hordern & Street, 2007b). The preconceived ideas on age, gender and presumed heterosexuality seen in the results can also be seen as another example of how nurses act on cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic scripts regarding what constitutes “normal” sexuality. The majority of people in palliative care belong to the older population. Research shows that sexuality can be of importance also in old age (Agronin, 2014; Beckman et al., 2014), indicating that ageism is a factor among at least some of the interviewed nurses. Likewise, the presumed gender differences in views on patients and partner sexuality that were found can be seen as connected to gender norms, not biological gender differences, and is analogue to described gender bias in healthcare (Hay et al., 2019). Assuming sexuality only between men and women can be due to hetero- and cisnormativity in nursing and nursing education (Carabez et al., 2015; Lindroth, 2016;

Röndahl, 2010). Again, this indicates that patients in palliative care run the risk of having their sexuality labeled by nurses’ sexual scripts. However, not all nurses in this study expressed these normative ideas on age, gender and sexual orientation, which is promising and indicates that professionalism is also shown. The findings differ from the results in the comparable study by Benoot et al. (2018), where one of the main findings was that nurses were influenced by their own interpretation of the philosophical principles underlying palliative care and not views on, or scripts for, sexuality. Methodological differences could be one reason for this, as Benoot et al. (2018) interviewed nurses individually, whereas we used focus group interviews – a method that to a larger extent reveals shared understandings of a phenomenon. Additionally, our use of sexual scripts theory to understand the findings guided us toward seeing norms on sexuality.

Finally, death and dying are topics that can be difficult to address and accept in a culture focused on health. It could therefore be argued that including sexuality, sexual health needs and sexual well-being in palliative care is adding insult to injury. One way to counteract this could be to put the existential parts and potentials of sexuality in the forefront – sexuality is a part of being a human, and human life exists until a person dies. Sexual and reproductive health and rights are global concerns (Starrs et al., 2018), and so is palliative care. Future research is needed on how to develop a palliative care that is truly inclusive of human sexuality until the moment of death. To develop, implement and evaluate best practices to include sexuality in palliative care in various global care contexts is a task well suited for nurses since it aligns well with global ethical values on holistic and person-centered care (International Council of Nurses, 2012).

Study strengths and weaknesses

The study has both strengths and weaknesses. The design used to reach the study aim was appropriate, and the empirical data was rich in variation and answered the research aim, which are both important aspects in establishing trustworthiness (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The variety in age and working years among participants is seen as a strength, but the homogeneity in gender representation is a weakness although it mirrors the workforce of nurses. To explain the concepts of sexuality and sexual health by using the WHO definitions prior to the interviews could have had an impact on the participants’ reasoning. However, it is

seen as an advantage that all participants were introduced in similar ways, and the use of the definitions prompted discussions.

That the first author had an insider’s perspective (work experience from palliative care) could be seen as both a strength (an understanding of the field) and a weakness (preconceived ideas). The continuous discussions between authors during the analysis and having the second author’s outsider’s perspective were efforts made to counterbalance this possible researcher bias. The frequent use of the participants’ quotations is another attempt to demonstrate trustworthiness. That some of the participants expressed gratitude for having had the opportunity to discuss the subject of sexuality in palliative care is seen as a study strength, as their thoughts and reflections were genuine. Finally, the transferability of the findings is limited to similar contexts, that is, countries where palliative care nurses work according to similar policies.

Conclusions

Nurses’ experiences of working with sexuality in palliative care shows that sexuality has an indistinct place in their work, but the subject of sexuality appears to be easily retrieved in conversation. That nurses experience and understand that sexuality is in transformation during the palliative care phase was also found. They express that they lack knowledge, routines and organizational support, but nevertheless want to do right. Overall, nurses appears to follow different cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic scripts on sexuality rather than knowledge-based guidelines. This indicates the importance of managers in palliative care to safeguard adherence to existing guidelines where sexuality is already included. In this work, it is important to have norm-awareness to avoid excluding patients and partners that differ from the nurses themselves or from societal norms on sexuality in connection to age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation and relationship status.

Relevance to clinical practice

The results can be of use in clinical practice to both nurses working close to patients and their close ones, and to nurse managers. It could serve as a discussion material for nurses to become aware of norms (professional versus personal) on sexuality, and if and how sexuality is incorporated in their palliative care. Moreover, the findings can be used as a point of

departure for nurse managers when implementing existing or new guidelines to include and address sexuality and sexual health needs in palliative care.

Impact statement

Nurses’ experiences of working with sexuality in palliative care is characterized by the lack of including the topic of sexuality, the awareness that sexuality is in a state of transformation for both patient and partner, and wanting to do right.

Nurses’ work with sexuality in palliative care must include knowledge of the wide variations of human sexuality and not be based on preconceived ideas concerning patient age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation or relationship status.

References

Agronin, M.E. (2014). Sexuality and Aging. In: YM Binik and KSK Hall (Eds) Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy, 5th edition, pp: 22–31. New York: Guilford Press. Areskoug-Josefsson, K., Schindele, C., Deogan, C., & Lindroth, M. (2019). Education for

sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR): a mapping of SRHR-related content in higher education in health care, police, law and social work in Sweden. Sex education, 19(6), 720–729.

Beckman, N., Waern, M., Östling, S., Sundh, V., & Skoog, I. (2014). Determinants of sexual activity in four birth cohorts of Swedish 70-years-olds examined 1971-2001. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11, 401–410.

Benoot, C., Enzlin, P., Peremans, L., & Bilsen, J. (2018) Addressing sexual issues in palliative care: A qualitative study on nurses’ attitudes, roles and experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74, 1583–1594.

Blakey, E.P., & Aveyard, H. (2017). Student nurses’ competence in sexual health care: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 3906–3916. Bowden, G., & Bliss, J. (2009). Does a hospital bed impact on sexuality expression in

palliative care? British Journal of Community Nursing, 14(3), 122–126.

Carabez, R., Pellegrini, M., Mankovitz, A., Eliason, M., Ciano, M., & Scott, M. (2015). “Never in all my years…”: Nurses' education about LGBT health. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(4), 323–329.

Cooperation of Regional Cancer Centers. (2016). National care program. Palliative care at the end of life. [In Swedish: Nationellt vårdprogram. Palliativ vård i livets slutskede]. Retrieved 2020-02-17 from: https://www.cancercentrum.se

Enzlin, P. (2014). Sexuality in the context of chronic illness. In: YM Binik and KSK Hall (Eds) Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy, 5th edition, pp: 436–456. New York: Guilford Press.

Flynn, K.E., Lin, L., Bruner, D.W., Cyranowski, J.M., Hahn, E.A., Jeffrey, D.D. et al. (2016). Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to Quality of Life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1642–1650. Gagnon, H.J., & Simon, W. (2015) The social origins of sexual development. In: M Kimmel

and R Plante (Eds.) Sexualities, Identities, Behaviors, and Society, 2nd edition, pp: 22–32. New York: Oxford University press.

Galbraith, M.E., & Crighton, F. (2008). Alterations of sexual function in men with cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 24(2), 102–114.

Gianotten, W.L, (2007). Sexuality in the palliative-terminal phase of cancer. Sexologies, 16, 299–303.

Gidlund, K. (2013). I kroppen min: resan mot livets slut och alltings början. [In Swedish: In my body: the journey to the end of life and the beginning of everything]. Stockholm: Forum förlag.

Graneheim U.H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112.

Hay, K., McDougal, L., Percival, V., Henry, S., Klugman. J., Wurie, H. et al. (2019).

Disrupting gender norms in health systems: making the case for change. The Lancet, 393(10190); 2535–2549.

Hautamäki, K., Mittettinen, M., Kellokumpu-Lethinen, P.L., Aaltp, P., & Lehto, J. (2007). Opening communication with cancer patient about sexuality-related issues. Cancer Nursing, 30(5), 399–404.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: The experience

of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 32 (4) 271–280.

Helms, R., O’Hea, E., & Corso, M. (2008). Body image issues in women with breast cancer. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13(3), 313–325.

Higgins, A., Barker, P., & Begley, C.M. (2006). Sexuality: The challenge to espoused holistic care. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(6), 345–351.

Hordern, A., & Street, A. (2007a). Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: Patient and health professionals perspectives. Social Sience & Medicine, 64, 1704-1718.

Hordern, A., & Street, A. (2007b). Let’s talk about sex: Risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemporary Nurse, 27(1), 49–60.

Hughes, M. (2008). Alterations of sexual function in women with cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 24(2), 91–101.

Hughes, M. (2009). Sexuality and cancer: the final frontier for nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(5), 241–246.

International Council of Nurses. (2012). The ICN code of ethics for nurses. Retrieved 2020-02-17 from:

https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%20eng.pdf

Kitzinger, J.. (1996). The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health and Illness, 16(1), 103–121. Krueger, R.A., & Casey, M.A. (2014). Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research,

5th edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

Lemieux, L., Kaiser, S., Pereira, J., & Meadows, L.M. (2004). Sexuality in palliative care: Patient perspectives. Palliative Medicine, 18,(7), 630–637.

Leung, M.W., Goldfarb, S., & Dizon, D.S. (2016). Communication about sexuality in advanced illness aligns with a palliative care approach to patient-centered care. Current Oncology Reports, 18 (11).

Lindroth, M. (2016). “Competent persons who can treat you with competence, as simple as that”- An interview study with transgender people on their experiences of meeting health care professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23-24, 3511–3521.

Matzo, M. (2010). Sexual health and intimacy. In: M Matzo and D Witt Sherman (Eds), Palliative care nursing-Quality care to the end of life, 3rd edition, pp: 65–74. New York: Springer.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th edition. Pittsburgh: National Consensus Project. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2019). End of life care for adults: service

delivery. NICE guideline [NG142.]. Retrieved 2020-02-17 from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng142/chapter/recommendations#holistic-needs-assessment

Palliative Care Australia. (2018). National Palliative Care Standards, 5th edition. PCA: Canberra. Retrieved 2020-02-17 from:

https://palliativecare.org.au/wp- content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/11/PalliativeCare-National-Standards-2018_Nov-web.pdf

Perz, J., Ussher, J.M. & Gilbert, E. (2013). Constructions of sex and intimacy after cancer: A methodology study of people with cancer, their partners, and health professionals. BMC Cancer, 13 (270).

Redelman, M.J. (2008). Is there a place for sexuality in the holistic care of patients in the palliative care phase of life? American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 25(5), 366–371.

Reese, J.B., Beach, M.C., Smith, K.C., Bantug, E.T., Casale, K.E., Porter, L.S., & Lepore, S.J. (2017). Effective patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in breast cancer: A qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(10), 3199–3207. Rice, A.M. (2000). Sexuality in cancer and palliative care 2: exploring the issues.

International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 6, 448–453.

Röndahl, G. (2010). Heteronormativity in health care education programs. Nurse Education Today, 31, 345–349.

Saunamäki, N., Andersson, M., & Engström, M. (2010). Discussing sexuality with patients: nurses’ attitudes and beliefs. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 6, 1308–1316.

Saunamäki, N., & Engström, M. (2014). Registered nurses’ reflections on discussing sexuality with patients: Responsibilities, doubts and fears. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(3-4), 531–540.

Starrs, A.M., Ezeh, A.C., Barker, G., Basu, A., Bertrand, J.T., Blum, R., Coll-Seck, A.M. et al. (2018). Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 391(10140): 2642– 2692.

Stead, M.L., Brown, J.M., Fallowfield, L., & Selby, P. (2003). Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. British Journal of Cancer, 88, 666–671.

Taylor, B. (2014). Experiences of sexuality and intimacy in terminal illness. Palliative Medicine, 28(5), 438–447.

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. (2013). Knowledge support for good palliative care at the end of life. Guidance, recommendations and indicators. Support for guiding and managing. [In Swedish: Nationellt kunskapsstöd för god palliativ vård i livets slutskede. Vägledning, rekommendationer och indikatorer. Stöd för styrning och ledning.] Västerås: Edita Västra Aros.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32 –item checklist for interviews and focus groups.

International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

Vitrano, V., Catania, V., & Mercadante, S. (2011). Sexuality in patients with advanced cancer: A prospective study in a population admitted to an acute pain relief and palliative care unit. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 28(3), 198–202.

Wang, K., Ariello, K., Choi, M., Turner, A., Wan, B.A., Yee, C., Rowbottom, L. et al. (2018).

Sexual healthcare for cancer patients receiving palliative care: a narrative review. Annuals of Palliative Medicine, 7(2):256–264

WHO. (2006). Defining sexual health. Report of a technical consultation on sexual health 28-31 January 2002, Geneva: World Health Organization.

Table 1. Interview guide What is

sexuality?

Associate freely around sexuality and palliative care.

Do you experience changes in patient/partner sexuality, and if so, how?

Supportive needs

What sexual needs do you see?

What can affect these needs?

Responsibilities Who is responsible for bringing up questions of sexuality/sexual health needs?

What advantages/disadvantages can you see in talking about sexuality with patients/partners?

Practical nursing

Can you tell of a specific situation when you have discussed sexuality with a patient/patient’s partner?

In what situations is it relevant to bring up sexuality? What aspects of sexuality has been or can be brought up?

Possible influences

What within yourselves can affect conversations on sexuality? What within the workplace affects conversations on sexuality? What enhances conversations on sexuality?

What hinders conversations on sexuality?

Table 2. Example of the analysis process for two different meaning units

Meaning unit Condensed

meaning unit

Code Subcategory Main category

“It is a little difficult to use that word.”

“Yes, I think that many, perhaps elderly mostly, connect it to sexual intercourse.” Difficult to use the word ‘sexuality’, especially with the elderly, as it is associated with sexual intercourse. ‘Sexuality’ is a difficult word to use. ‘Sexuality’ or

‘intimacy’? An indistinct place “If you change the word, not use

‘sexuality’ but rather ‘intimacy’, like we said. That word is not as strong, and it means so much more.” ‘Intimacy’ is an easier word to use than ‘sexuality’.

Accepted Article

Table 3. Nurses’ experiences of working with sexuality in palliative care, main categories and subcategories.

Main categories Subcategories

An indistinct place Sexuality or intimacy?

Relevant or not?

A transformation Patient and partner relations

Patient sexual expressions Wanting to do right Possible and factual efforts

Organizational and personal obstacles

Methods and responsibilities