Mälardalen University Press Licentiate Theses

No. 99

COLLABORATIVE PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT:

A COLLABORATIVE DECISION-MAKING APPROACH

Joakim Eriksson

2009

Copyright © Joakim Eriksson, 2008

ISSN 1651-9256

ISBN 978-91-86135-16-4

Printed by Arkitektkopia, Västerås, Sweden

A

BSTRACT

The process of developing products is a central contributor to companies’ competitiveness. Since the mid-20th

century, vast efforts has been made to try to support this process through new theories, methodologies, and methods. Today, organisations find themselves in a situation where they need to continuously improve the performance of the product development process in order to stay ahead or even keep up with competitors. The process of developing and producing a product is a knowledge-intense activity influenced by many actors and affecting many actors in the organisation. Thus, most decisions made during product development are collaborative.

A lack of understanding of the nature of decision-making in organisations results in a behavioural pattern of poor decision-making strategies and tactics, which in turn impacts on the performance of the product development process. Currently, no methodology or methods are available for process improvements in product development that focus on decision-making fundamentals and the performance of decisions made within the product development process.

In order to support product development process improvements, it is important to develop knowledge about how the collaborative decision-making process can be viewed holistically (as a system) and include its relation to overall performance. This is the main objective of this research.

The research is based on an extensive literature review and two case studies in three Swedish manufacturing companies with in-house product development. The literature review is summarised in the chapter “Frame of References”. The first case study aimed at understanding the elements and their relations, i.e. a system. The system relates fundamental aspects of decision-making, the product development process, and performance aspects. The second case study aimed at understanding what actors perceive to effect collaborative decision-making. The result was used in relation to theory in order to develop a model of competencies for collaborative decision-making.

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to start with expressing my gratitude to my ever inspiring supervisor, Adjunct Professor Björn Fagerström. His commitment to this research work and guiding discussions have served as a source of inspiration and direction throughout these past two and a half years. Secondly, I would like to thank my assisting supervisor, Professor Mats Jackson, for his open-minded mindset as a leader and his trust in my choices throughout this research work. Both Björn and Mats have provided a creative work atmosphere in the research group and always encourage one to strive beyond one’s limits. Thank you both for all your discussions and guidance!

I would also like to thank the people in our research group for their support and encouragement: Mikael Hedelind, Erik Hellström, Antti Salonen, Anna Granlund, Yuji Yamamoto, Dr. Sofi Elfving, Dr. Marcus Bengtsson, Carina Andersson, Anders Wikström, Jennie Andersson, Adjunct Professor Monica Bellgran and Mats Deleryd. You all make the research work interesting and fun!

I would especially like to thank Stefan Johnsson and Dr. Rolf Olsson for their commitment to our common research interest of performance in product development. Our common goal and different backgrounds became the basis for inspiring creative thinking. Thank you both. I am looking forward to continuing our collaboration!

Also, Annette Brannemo at VCE Components deserves a big Thank You for the support she has given. Our cooperation has provided me with invaluable ideas and feedback on findings and thoughts.

Further, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to the companies that provided the opportunities for conducting research through industrial cases, as well as the kind people in companies who provided general discussions and insight about different industrial situations. Among the companies are: LogMax AB, VCE Components, JAPS Elektronik AB, ABB Robotics, and Uponor AB.

Last, but not least, I would like to send my love to my family and friends for their friendship and support in my “other” life which runs beside the “research life”.

P

UBLICATIONS

L

IST OFI

NCLUDEDP

UBLICATIONSPaper A Eriksson, J., Fagerström, B., Elfving, S., Efficient Decision-Making in Product

Development, in International Conference of Engineering Design. 2007,

ICED: Paris, France.

Paper B Eriksson, J., Johnsson, S., Olsson, R., PhD, Modelling Decision-Making in

Complex Product Development, in International Design Conference. 2008,

Design 2008: Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Paper C Eriksson, J., Brannemo, A., Elfving, S., Decision Focused Product Development

Process Improvements, Submitted to the International Conference of

Engineering Design. 2009, ICED, 2009: Palo Alto, CA, USA.

A

DDITIONALP

UBLICATIONSJohnsson, S., Eriksson, J., Modeling Performance in Complex Product Development – a Product

Development Organisational Performance Model in Proceedings of the 17th

International Conference on Management of Technology. 2008, IAMOT: Dubai, U.A.E.

Johnsson, S., Wallin, P., Eriksson, J., What is Performance in Complex Product Development? In Proceedings of the R&D Management Conference. 2008, Ottawa, Canada.

Eriksson, J., Hansen, C.T., A Proposal for a Mindset of a Project Manager in NordDesign 2008. 2008, Tallinn, Estonia.

T

ABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT III

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V

PUBLICATIONS VII

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IX

INTRODUCTION AND POSITIONING

11

Collaborative Product Development 11

Problem Statement 13

Objective 14

Research Questions 15

Delimitations 16

Practical and Academic Relevance 17

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

19

Research within Design Science 19

Research on Decision-Making 21

Research Project Design 22

Scientific Approach 23

Research Strategy - Case Studies 25

Methods for Collecting and Analysing Data 26

The Research Process 26

The Quality of the Research 28

Validity 29 Reliability 29

FRAME OF REFERENCES

31

The Process of Developing Products 31

What is product development performance? 34

Improving the Process of Developing Products 36

Decision-Making in a Product Development Context 39

What is a decision and decision-making? 39

What is a good decision? 40

Decision-Making in Product Development Literature 41 Different Views of Decision-Making in Product Development 43

Collaborative Decision-Making in Product Development 47 Decision Management and Decision Support in Product Development 53

Reflections on the Theory 57

EMPIRICAL STUDIES

61

Research Clarification – Case Study in Company X & Y 61

Background and Problem Statement 61

Empirical Findings in the Research Clarification Case Study 62 Reflection and Conclusions from the Research Clarification Case Study 65

The Descriptive Case Study 71

Background and Problem Statement 71

Empirical Findings in the Descriptive Case Study 72 Reflection and Conclusions from the Descriptive Case Study 75

CONCLUSIONS, CONTRIBUTION, AND FUTURE WORK 81

Conclusions 81

Fulfilment of Objectives 82

Contribution 83

Quality of the Research and Validity of the Results 84

Future Work 85

Best practice of collaborative decision-making 85 Formal and informal activities of collaborative decision-making 85

C

HAPTER1

I

NTRODUCTION AND POSITIONING

This first chapter focuses on the question; “Why focus on collaborative decision-making?”. It describes the background of the research, and presents the problem statement, objective, delimitations, and paractical and academic relevance of the research. The outline of the thesis is also presented.

Collaborative Product Development

In the beginning of the 20thcentury, Henry Ford introduced a product development management style that still influences our way of managing product development in the Western World. The hierarchical management system of organisations builds upon the fact that top management knows what is needed to be done and how. Top management then uses the chain of command to lead and guide the activities with precision in order to produce a product as quickly and cost efficiently as possible. Technological advances in the 1940-50’s resulted in projects becoming more complex and the US military developing Systems Engineering [1] and Concurrent Engineering [2] in order to manage the large scale, complex, product development projects which they undertook. The product architecture and the development activities needed to be connected and coordinated in order to oversee the whole of the development and produce a product in a short period of time. During the 1970’s, Pahl and Beitz [3] introduced a systematic approach to Engineering Design in order to improve the design approach and methods used by engineering designers. They introduced a systematic approach to product development in the form of a methodology1

. Several more researchers followed, developing the methodology further, e.g. Ulrich and Eppinger, [4] and Ullman [5]. In the 1980’s, Freddy Olsson [6] introduced a new approach

1

Pahl, G. and W. Beitz, Engineering Design: A Systematic Approach, p.24, 2007,

for product development management focusing on the collaborative aspect of product development. Product development was seen as a social process that needed to be coordinated, as well as the development of the product architecture. Andreasen and Hein [7] followed in the late 1980’s, introducing the concept of Integrated Product Development. Later, Cooper [8] introduced and trademarked the Stage Gate Model in order to give top management of large corporations a better ability to manage the product development process. The Stage Gate Model was based on a resource management model developed by NASA in the 1960s, and was called PPP (Phased Project Planning). It has been called the world’s first stage gate model [9, 10].

The evolution of the different presented product development approaches shows that when the products get increasingly complex, as well as the size of the organisation necessary to produce them grows, it results in the need to manage the integration and collaboration aspect of the development process. Somewhat simplified, in conclusion, making successful decisions gets increasingly difficult when the decisions demand the input from, and affect, many different actors. Some of the later management concepts for product development were designed to support these difficulties, and did so to some extent. Modern product development methodologies include most of the necessary ingredients from systems engineering, concurrent engineering, integrated product development, and the Stage Gate. However, the difficulty of managing the integration of actors’ knowledge in groups in order to make collaborative decisions is not yet overcome, and the pace and complexity of product development is still increasing in many businesses. Today we often refer to “knowledge-intense” product development [11], which demands the integration of many actors’ different knowledge and expertise in order to develop a high-technological product. The need to be able to make collaborative decisions that contributeto the overall success of the developed product still increases in importance.

Jankovic [12] (p.15), describes the implications of a modern collaborative industrial environment during the product development process: “In this process, every actor has specific

objectives defined for his domain of action. Therefore, collaborative decision-making is a process where actors have different and often conflicting objectives. Actors in the collaborative decision-making process also have different knowledge concerning the problem as well as different information and points of view.”

The need to integrate and make use of different actors’ knowledge and expertise during decision-making makes the process of developing products difficult. Product development in particular imposes a challenge through the need to integrate inputs from unrelated and distant sources of information in an organisation during the decision-making process. Simon [13] and Busby [14] identified some of the related difficulties within the decision-making process during product development. They showed for example how actors failed to

integrate different actors’ knowledge, not communicating assumptions, not considering other actors’ objectives, not considering consequences of other actors’ actions, and not defining scopes of tasks.

Simon [13] advocates a systematic approach to implementing changes in the decision-making process of a product development organisation in order to introduce the changes in a timely and profitable manner.

Problem Statement

On the 25th

of January, 2007, a fellow PhD student (today a PhD) and I held a workshop addressing current and future industrial challenges within product development with 19 representatives from nine large companies located in the surrounding area of Stockholm, Sweden. The area of most interest, and the most frequently discussed topic, was about collaboration, i.e. the issue of collaboration within the company as well as outside the company. The common conclusion in the workshop was that while the technological aspects of product development can often be solved by the organisations themselves, there is a great need for external thoughts and support regarding the aspect of collaboration within product development.

This conclusion is supported by the literature which describe that organisations find themselves in a situation where they need to continuously improve the performance of the product development process in order to stay ahead or even keep up with competitors. The process of developing and producing a product is a knowledge-intense activity influenced by many actors and affecting many actors in the organisation. This kind of process has both quantitative and dynamic complexity that, if not treated as different interacting systems, is difficult for people in the organisation to manage. These systems are broken down into sub systems and dependencies are managed as a whole. This is done in order to realise a desired level of organisational performance. Each decision made must be related to the overall competitiveness of the organisation as a whole. Haffey states: “… organisations must address

and overcome situations where departmental functions and activity resources optimise their solutions or outputs to satisfy goals that do not reflect or contribute to the satisfaction of the higher-order goals associated with an organisation. In order to promote the degree of integration attained throughout an organisational system, each individual process, activity, resource and decision must be considered from a more holistic organisational perspective and subsequently be coalesced effectively within the organisation system in order to support the realisation of desired degree of organisational performance” [15] (p.2).

According to Yates [16], a lack of understanding of the nature of decision-making in organisations is the problem. This results in a behavioural pattern of failure-prone

decision-development process. Currently, there is no methodology or methods available to “process improvers” in product development that focus on decision-making fundamentals in order to improve the performance of decisions made within the product development process. Yates describes a suitable analogy: “At a superficial level, everyone understands what hitting a golf

ball entails. (“You just swing that stick, right?”) At a similar level of superficiality, everybody knows what decision problems are and what solving them entails. Unfortunately, superficial understanding typically is insufficient for guiding intelligent and effective efforts to either strike golf balls or manage decisions. Also unfortunately, all too often, managers have no more than a vague grasp of the true nature of decision problems and processes” [16] (p.10).

In summary, this thesis concludes that there is a lack of knowledge of collaborative product development process improvements that focus on generic decision-making abilities in relation to overall process performance. In order to support product development process improvements, it is important to develop knowledge about how the collaborative decision-making process can be viewed holistically (as a system) and include its relation to performance. This is the main focus and the identified problem area of the research presented in this thesis.

Objective

Based on the problem statement, the objective of this research is to enhance the knowledge of collaborative product development process improvements that focus on generic decision-making abilities in relation to overall process performance.

The approach in this research is to view decision-making from a fundamental level and investigate the implications it has on process improvement efforts. The analysis is conducted in order to understand the nature and success of the overall decision-making ability of groups of actors. The aspect of what decision-making success is and how to measure the success in order to improve decision-making is an important part of this research. Further, the relationship between decision-making success and product development process success is vital to clarify in order to create a decision-making system within a product development context.

This research investigates the concept of collaborative decision-making, which includes knowledge from research areas outside engineering design. Except for engineering design science, organisational and decision science, for example, will be investigated in order to gain knowledge of organisational decision-making models and behaviour to apply in collaborative product development process improvements.

Research Questions

To be able to meet the objective of this research, which is to enhance the knowledge of the collaborative decision-making process by focusing on decision-making fundamentals in relation to overall process performance, a set of three research questions are proposed below.

The first research question is posed to investigate what is needed in order to manage decision-making fundamentals, decision-making success, and the relation to the collaborative product development process.

The result from RQ1 reveals that there is little written about these aspects as a whole and

that decision management is often based on prescriptive models of decision-making. These approaches often relate decision-making to different decision performance aspects, e.g. reaching consensus, or satisfaction. The models of decision management do not relate to product development process performance. Product development methodology is often the basis for process improvements and describes the product development process from different views, e.g. the product lifecycle, concurrent engineering, design phases, or engineering phases. When relating product development processes to decision-making and performance, there are several aspects of particular interest: objectives, uncertainty, preferences, alternatives, criteria, decision-making structures and processes, communication, and decision environment.

The second research question is posed, based on the result of RQ1, in order to investigate

elements and factors of collaborative decision-making in an organisational context. This research question aims at providing a basis for the third research question by enabling the understanding of how fundamental decision-making aspects relate to decision-making performance within a product development organisational context.

The result from RQ2 reveals two major factors of difficulties of collaborative

decision-making: awareness of decision-making fundamentals, and the relationship between collaborative decision-making aspects and decision-making performance. The results provide two different aspects of how to analyse decision-making in a product development organisational context: (1) the specification of the organisational landscape and its relation to performance, and (2) the selection of an appropriate decision-making model in order to

RQ2 – What are the major elements and factors of collaborative decision-making in product development?

analyse relevant decision-making aspects. The case study resulted in the development of a decision-making system of collaborative product development (see Figure 15).

The third research question is posed in order to investigate what actors perceive to effect decision-making abilities of a product development group, and thereby enhance the knowledge of the nature of naturalistic collaborative decision-making. The research question also aims at ensuring that a real industrial problem is investigated in this research work.

The result from RQ3 identifies actors’ views of the collaborative decision-making process

and different aspects of collaborative decision-making in a product development organisational context: (1) awareness of making fundamentals, (2) use of decision-making strategies and tactics, (3) awareness of influencing factors of decision-decision-making, and (4) awareness of the relationship between collaborative decision-making aspects and decision-making performance.

Delimitations

This research is focused on Swedish multinational organisations involved in knowledge-intense in-house product development that results in physical artefacts. This type of product development, often called Complex Product Development, includes two types of complexities: dynamic and quantitative. This type of product development is often carried out within large organisations, involving many people within a large diversity of expertise in order to develop a product that often includes mechanics, electronics, and software – also called Mechatronics.

The tasks and activities conducted during product development are increasingly dependent on access to accurate information, extraction, and exchange. Further, decision makers need to identify and include different expertise and perspectives in order to make informed decisions. The amount of information, communication, decision criteria and performance aspects in product development decision-making, together with the fact that there is often no optimal solution obtainable, makes normative and analytical decision support unfit as a solution within this research.

No specific decision-making methods, e.g. specific IT-solutions, are presented in this research, but support methods are treated as an element of collaborative decision-making.

RQ3 – What factors do actors perceive to effect a collaborative decision in

product development, and how do the factors relate to the decision-making literature?

The multi-knowledge research area of decision-making includes research in psychology, which encompasses human cognitive processes. Such processes will not be included in the scope of research. The focus of this research is on the collaborative decision-making process within product development processes and is a matter of the communicative aspect of decision-making – the observable part of decision-making. There are many questions of great importance about the designer’s individual strategy when making decisions: is it a good strategy? Can it be altered? Should it be altered? However, the research described in this thesis will not try to answer those questions. Instead it examines the observable aspects of how groups of people make decisions related to design parameters within the group and together with other groups in a product development organisation. The focus is upon the project manager and his/her interactions with a steering committee, the development group, and external actors. As a result, decision-making will not be included as a human individual process, thereby excluding detailed knowledge about decision-making style and human cognition.

The people in the group include every individual who is a part of resolving an issue controlled by a project steering committee in a product development project and people from different levels and functions in the organisation.

Practical and Academic Relevance

There are two different results expected to be derived from this research: a scientific contribution to the research community and a practical and usable contribution to the industrial problem targeted.

The expected scientific contribution of this research includes theoretical and empirical conclusions of the different decision-making models and aspects within, as well as outside, the research area of engineering design. This is to enhance the knowledge of decision-making abilities of groups of actors engaged in product development.

The expected industrial contribution is aimed at increasing the awareness of the importance of collaborative decision-making in industrial situations. All results partially aim at providing industry with the increased ability to handle collaborative decisions.

The long-term objective of this research is to provide a framework that, by focusing on decision-making fundamentals, enables the assessment and minimisation of uncertainties in the product development process in order to continuously customize and improve the product development process. Hopefully, the long term effect is will be an increased ability for companies to introduce changes to the collaborative product development process in a timely and profitable manner.

C

HAPTER2

R

ESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The second chapter presents the “research journey” of the conducted research and is divided into four sections, called “Research within Design Science”, “Research on Decision-Making”, “Research Design”, and “The Quality of the Research”. The research is aimed at providing results valid for both the industrial and the scientific community (see Figure 1). The chapter describes the methodology used within this research and discusses the quality of the research conducted.

Starting point Research/ Learning Process Theory Real World Collecting and analysing Empirical data Case Studies Goal Vision New Scientific knowledge New Practical knowledge Methodological Approach Objectives Research Questions Literature review Theoretical prepositions

Figure 1. My research process [17].

Research within Design Science

The objective of this research is to contribute to knowledge about and for designing products, and is therefore a matter of Design Science. Designers and engineers are in a position to effect people’s way of life and are therefore carriers of an important responsibility, “…since their ideas, knowledge and skills determine in a decisive way the technical,

economic and ecological properties of the product” [18] (p.1). Therefore, it is vital to develop an

understanding of designing in order to improve the skill and knowledge of actors.

In 1992, Vladimir Hubka and W. Ernst Eder published their book called “Einführung in die Konstruktionswissenschaft” or “Design Science: Introduction to the Needs, Scope and Organization of Engineering Design Knowledge,” as the 1995 English edition was called. The authors introduce the history and sources of knowledge development of designing and outline the research area in the following statement:

The term Design Science is to be understood as a system of logically related knowledge, which should contain and organize the complete knowledge about and for designing. [19] (p.35)

It can be stated that this concept of design science today includes a vast amount of research topics in order to create knowledge about and for designing products, or more described today as the activity of product development.

Hubka and Eder states three goals of Design Science [19]:

Goal area practice: direct improvement of the situation in engineering practice, i.e. in a company or an organization group, or in a project, with two addressees:

directly to designers

indirectly in the enterprises (as the superior system)

Goal area science: answering of scientific questions, as for example in a research project or a dissertation;

Goal area education: improvement of design education in the schools.

In a later journal article, Eder [20] divides engineering design knowledge into four categories: practice knowledge, theory knowledge, object knowledge, and process knowledge. The process knowledge category is comprised of knowledge of human activities and theories of human

behaviour. Knowledge of human activities is about strategies and tactics when designing, and theories of human behaviour concerns cognitive aspects of designers. It is within the first

context (knowledge of human activities) that the research described in this licentiate thesis is positioned.

Further, engineering design can be said to consist of two processes: technical and commercial. The definition of the technical process is producing an artefact and the commercial process is about profit, and so the product “forms the link between the technical and

commercial development process” [21] (p.21). In other words, product management focuses on

the market and the tradeoffs between customer value and product cost. This ensures the maximisation of the revenue, i.e. the aspect of effectiveness. The purpose of projects within the product development process is to achieve the stated goals with the minimal use of

resources, i.e. the efficiency aspect. There is no effort made in this research to separate the two processes. That is because they are often two trade-off aspects of decisions made in product development.

In fact, the difficulty that presents itself in most, if not all, product development decisions are the tradeoffs between different performance aspects. The performance aspects are often not viewed alike by different levels and departments in organizations, who all try to satisfy their objectives. Collaborative decision-making is defined by Jankovic [12]: “Collaborative

decision-making is a collective decision-making where different actors have different and often conflicting objectives in the decision-making process.” The role of collaborative decision-making in product

development can therefore be described as the task of collectively reaching an agreement on objectives and to use those objectives in order to reach a satisfying decision on performance tradeoffs. This is the basis for this research on collaborative decision-making in product development.

Research on Decision-Making

The application of Descriptive Decision Theory has largely been done in Operations research and Management Science, while Normative and Prescriptive Decision Theory has largely been applied in Engineering, Economics, and Mathematics. Collaborative decision-making, as a part of organisational decision-decision-making, has been dealt with within different scientific areas. Decision analysis is common within normative and prescriptive approaches such as mathematics and engineering, observation of human decision-making activities is common in descriptive approaches such as management science, and decision-making as a group activity is common within behavioural science. [12]

In design science, the concept of decision-making is mostly focused towards the prescriptive models of decision-making in order to support designing. Theories of human behaviour are often limited to the level of “activities” conducted within product development and do not consider the aspect of fundamental decision-making behaviour.

Design Science, a multidisciplinary research area, includes human behaviour. It could therefore encompass decision-making literature developed within e.g. organisational science. In order to include knowledge from scientific disciplines other than those traditionally applied into the research area of design science, it is important to focus on the design of the research with the included research methods that support that multidisciplinary approach. After all, what distinguishes a researcher from a non-scientist is not what is being studied but how it is being studied [22].

Research Project Design

An existing design research methodology has been adopted and used throughout this research with the intent to contribute with well-founded research results to both the industrial and the scientific community. The methodology, called DRM (Design Research Methodology) [23], outlines the necessary steps to take in order to produce research results that contribute to the system of knowledge of and for designing. Different research methods are chosen and used within each step to clarify objectives and find answers to the stated research questions being investigated at that time (see Figure 2).

Research Clarification

Descriptive Study 1

Prescriptive Study

Descriptive Study 2

Basic Method

Results

Focus

Observation & Analysis Assumption & Experience Observation & Analysis Measure Influences Methods Applications

Figure 2. The Design Research Methodology (DRM) [23].

In order to systematically describe the crucial aspects of the research in relation to the DRM, Maxwell’s model of research design is used [24]. That is because of its focus on research based on qualitative data (see Figure 3).

DRM Conceptual framework Goals Validity Methods

Figure 3. Planning a research project, adaptation of [24].

This model clarifies the Goals, Context (conceptual framework), Methods, Research Questions, and Validity of the research.

The Goals concerns the motivation of the research and is described in the “Problem

Statement” and “Practical and Academic Relevance” in Chapter 1.

The context in which this research is to be conducted is described in Chapter 3, called

“Frame of References” and also in the “Scientific Approach” below and in “Delimitations” in Chapter 1.

The Research Questions is stated in Chapter 1.

Methods used to investigate research questions in the case studies are described in “Methods

for Collecting and Analysing Data” below.

Validity is about correctness of the research results and is discussed in “The Quality of the

Research” below.

Scientific Approach

The researcher’s view of the “real world” affects the choices made about research approach and methods used throughout the research project. According to Abnor and Bjerke [25], there are three methodological approaches to choose from: the analytical, the systems, and the

actors approach. These approaches are related to the two main paradigms in social science:

Positivism Hermeneutic The analytical approach

The systems approach

The actors approach

Figure 4. Methodological approaches related to paradigms [25].

The analytical approach aims at explaining the world as objectively as possible. The world is constituted by causal relations, i.e. cause and effect relations. Independent relations are sought, and Newton’s laws of physics are an example. The actors approach implies a view of the world as social constructions and knowledge is not objective. Social constructs are investigated and understood.

The systems approach was developed during the 1950s as a response to the difficulties in applying an analytical approach to social problems within a technical context. [25] The research described in this licentiate thesis is based on the systems approach.

The systems approach can be used for open or closed systems. An open system interacts with its surroundings. In addition, a system can be divided into sub-systems, and the total sum of the system may differ from the sum of its sub-systems. This is due to the important relationships between the parts that impact the whole of the system. The systems approach aims at not only explaining but also understanding which forces cause an effect in the system. Decision-making in product development is often made by interacting actors in the system. This causes both quantitative and dynamic complexity. Decisions often include organisational and human factors as well as aspects of the technical systems. When focusing on the decision-making abilities of actors involved in product development, it is suitable to adopt a holistic view of organisational decision-making because of the complex relationships between decision and performance in the organisation. Therefore, in the attempt to improve decision-making abilities, this research focuses on the study of how decisions are made, not what is being decided. The systems approach emphasises a holistic view of the system in order to manage complexity, and is therefore suitable for the research of decision-making in a product development context.

The system of decision-making in product development is influenced by outside systems and forces, and is therefore considered to be an open system. These outside systems and forces are important motivators in the pursuit of decision-making skills in order to handle

complex decision situations. They also introduce an increased level of complexity to the system. Systems theory is a promising effort to deal with this complexity. There, an understanding of a system cannot be based on knowledge of the parts alone. The real leverage in most management situations lies in understanding dynamic complexity, not detail complexity [26]. It is also important to see the processes of change for the system over time, rather than taking snapshots.

In order to make sense of collaborative decision-making, the dynamics of communication and information, as well as the relationships between the decision-making process and different influencing aspects, are important. In this research, the system of collaborative decision-making in an industrial context is understood through the use of systematic principles that reflect aspects of collaborative decision-making identified as important for decision-making success.

Research Strategy - Case Studies

Yin [27] describes different research strategies and their applicability to different research situations. The strategies are: Experiment, Survey, Archival analysis, and Case study. When studying a phenomenon within an organisation by stating how and why questions, case study is the preferred strategy. A case study is described as: “…an empirical inquiry that investigates a

contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.” [27] (p.13).

Generally, the case study approach was used as a strategy. That was because most of the collected data was qualitative and therefore suitable for qualitative research methods aiming to investigate current phenomena in their natural contexts [27] in order to better understand the dynamics of systems [28]. A case study copes with typical technical situations, and has the advantage of relying upon multiple sources of evidence.

In this research, decision-making can be seen as the phenomenon, while the product development project organisation can be considered the context. Interactions take place with stakeholders inside as well as outside of the project organisation. These are organisational and managerial studies appropriate for applying the case study strategy [27]. Merriam [28] also states that with a case study strategy it is possible to focus on interpretation and insight, rather than on the test of hypothesis.

However, the case study strategy is open to the incorrect interpretation of data or biased results when the researcher adds his/her own subjective judgement into the results. This requires the researcher to be conscious of these aspects and actively work to prevent them.

Methods for Collecting and Analysing Data

The typical methods for collecting data when applying a case study strategy include interviews and data gathering from documents. Interviews are used to gather data from participants and observers of the phenomenon of interest. Interviews can be conducted in a group setting or one-on-one and can have different degrees of structure [28].

The degrees of structure are often labelled structured, semi-structured, or open interview. The structured interview has predefined questions, while the open interview is a discussion between the interviewer and the interviewee. Often when research based on qualitative data is being conducted, structured interview is the chosen method [28]. A semi-structured interview is prepared by stating a few questions that ensure the achievement of the overall goal of the interview. No detailed formulation or order of questions is prepared. Further, new questions are formulated by the interviewer based on data being analysed during the interview [28]. This approach aims at collecting as much data and insight as possible within the defined scope of the research.

The data collection made during this research was made through open interviews, semi-structured interviews, and analysis of companies’ documentation of decisions. Literature reviews were conducted throughout the research process within the fields of product development and decision-making in order to facilitate the identification of interview questions, as well as to provide a basis for the understanding of organisational decision-making when going into the case studies.

Yin [27] argues for the need of using analytical strategies when analysing data and presents several methods for analysing qualitative data. Categorisation [24, 27, 28], one example, includes the coding of data in order to rearrange data into categories to facilitate the comparison and development of theoretical concepts.

The Research Process

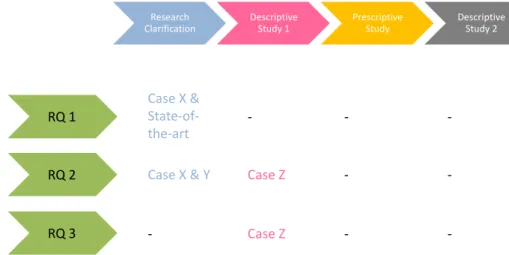

The research process was designed by connecting research methodology phases, research questions, and research methods. The connection between research questions and the research phases of the DRM can be seen in Figure 5. The methods chosen for investigating the research questions can be found in Table 1.

Even though the state-of-the-art and cases are placed within different phases and research question (Figure 5), the reality of answering the research questions has been much more complex. First of all, the research questions have changed over time, becoming much more refined in the end. Also, theories in literature have been studied throughout the research,

and conclusions from data in early case studies have been re-evaluated and updated in later stages. It has been an iterative process, just as Figure 1 describes.

Research Clarification Descriptive Study 1 Prescriptive Study Descriptive Study 2 RQ 1 RQ 2 RQ 3 Case X & State‐of‐ the‐art Case X & Y ‐ ‐ Case Z Case Z ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐

Figure 5. Connection between research questions and DRM phases.

In the first research phase, called “Research clarification”, the state-of-the-art was compiled and Company X was studied in 2006, paralleled with a literature review. The conclusion was that decision-making is a skill that actors are unaware of in the efforts made by companies to improve the product development process. Company Y was studied in 2006-2007 in order to answer research question 2. The conclusion from trying to answer research question 2 was that a more in-depth investigation of decision-making in product development was needed in order to move closer to an answer to research Question 2. At the same time, research question 3 was stated.

In the Descriptive study, Company Z was studied in 2007-2008, and a literature review was made in order to answer research questions 2 and 3. The conclusion was that decision-making procedures, decision-decision-making strategies, and structures are of great interest when trying to improve decision-making in product development.

Table 1. A summary of the research phases and case descriptions. A literature review is implied in all cases.

Research phase Design of case No. of respondents (interviews)

Business focus Unit of analysis

Data collection method

Data analysis Research question Research clarification State-of-the-art. Multiple- case/holistic 6 (7) 9 (12) Company X, Electronics Company Y, Mechatronics Decision-making system Interview, workshop, documentation Categorizing (coding) RQ1 RQ2 Descriptive phase Single-case/ embedded 7 (8) Company Z, Mechatronics Single decision-making process Interview, documentation Categorizing (coding) RQ2 RQ3

During the research journey, there was an attempt made to conduct a prescriptive phase in order to develop a prescriptive approach to project decision management. However, the author did not consider it well-founded enough in order to contribute to the knowledge of collaborative decision-making and its relation to performance. Therefore, the author decided to continue to conduct descriptive case studies in order to gain more well-founded knowledge of collaborative decision-making in an industrial context.

Apart from the case studies conducted, the connection to a real industrial problem has been important to clarify and continuously validate throughout the research process. To ensure the connection to an industrial problem, a discussion partner from a large international company in Sweden was obtained early on and continuously provided useful insights about decision-making in product development. Further, the author’s supervisor, based in a large international company, always provided interesting and useful insight about decision-making in product development.

The Quality of the Research

Determining the quality of the conducted research is not an easy task when the research is based on qualitative data [29]. This is especially true if the researcher uses a systems approach that means that knowledge developed is not general in the same sense as knowledge developed in an analytical approach [30]. However, in general, research results are measured using Validity and Reliability.

This research, carried out through case studies, is measured using the terms Validity and Reliability based on Merriam [28] and Yin [27]. Merriam describes two types of Validity:

internal and external. Yin discusses the issue of validity and how results may be generalised, as

well as the issue of Reliability.

Validity

When case study is used to carry out research, two types of validity should be considered: internal and external [28]. Internal validity is defined as the reliability of the results regarding the studied reality. External validity, on the other hand, is defined as the reliability of the results regarding the applicability to other situations besides the one studied in the current case study.

The Research clarification phase within this research was based on several sources of data and information. Thus, it made the result (i.e. the problem statement and RQ1 and RQ2) more valid than if just one source had been used. However, the results of the second case study have proven to be applicable to the specific company studied at that precise moment in time. There is no definite proof that the results may be applied outside that specific context. However, Merriam [28] states that the external validity of case studies is often hard to prove. She also finds it possible to discuss why there is no reason that the results would not be applicable to other cases. The importance of providing detailed descriptions of the conducted case studies is therefore increased in order to illustrate the context in which results are valid. Yin [27] proposes that case study findings be compared to established theory in order to investigate the existence (or not) of support for the results.

Reliability

Reliability is the ability of a researcher to repeat the same studies made and to reach the same results and conclusions as the first researcher did. Reliability within the systems approach in focused on what the measurements can be used for, not how precise they were during the case study. Consequently, in contrast to the analytical approach, the systems approach does not consider reliability to be as important [25]. Merriam [28] explains how reliability becomes a troublesome quest when studying human behaviour that is dynamic, not static. However, Yin [27] proposes that reliability is possible to obtain if other researchers gain access to the same documentation and well-documented research procedures used by the first researcher.

This research has been carried out using methods such as interviews, project documentation, and workshops within an industrial context. Another researcher would be hard pressed to repeat the same research and obtain the same results due to changes in the

On the other hand, if the research questions within this research were asked by another researcher and studied under the same conditions, the results could be similar in essence [31]. For example, how actors make decisions is not easily changed and could be observed under the same conditions and research question by different researchers and reach similar results.

C

HAPTER3

F

RAME OF

R

EFERENCES

This chapter introduces the theory used in this research in order to gather relevant data, analysis, and reflection on collaborative decision-making in product development activities. The chapter is divided into two sections: the process of developing products and decision-making in a product development context. The first section introduces theories of product development activities, product development performance, and how product development performance can be improved. The second section then introduces theories of making, product development as decision-making, and collaborative decision-making. Finally, this chapter is the summary of the compiled state-of-the-art and serves as a starting-point and basis for the research.

A research question was posed to investigate what was needed in order to manage decision-making fundamentals, decision-decision-making success, and the relation to the collaborative product development process:

This chapter summarises the state-of-the-art compiled in order to answer research question 1.

The Process of Developing Products

The process of developing products has become a central contributor to companies’ competitiveness. Since the mid-20th

century, there have been vast efforts to try to support this process through theories, methodologies, and methods. These efforts have been aimed at supporting certain aspects of difficulties at that time. Examples include shortening lead-time and improving team integration. The interesting question is what aspects of the processes of developing products does product development literature consider important when aiming to increase the performance of the process? The following part of this section is aimed at clarifying that question.

There are generic definitions of the process, and the whole product development process can be defined as: “… the set of activities beginning with the perception of a market opportunity and

ending in the production, sale, and delivery of a product” [32] (p.2). In literature, the definition of

product development [32] is often diverse. Examples include Complex Product and System Development (CoPS) [33], New Product Development (NPD) [34], Knowledge-Intense product development [11], Product Innovation [35], and Engineering Design [18]. Further, the definitions (along with the numerous methodologies and models of product development) describe different characteristics of the product development process. Systems Engineering (SE) [1], Concurrent Engineering (CE) [2], Integrated Product Development (IPD) [7], Dynamic Product Development (DPD) [36], and Stage-Gate [8] are examples, to mention a few. All of these models aim to support design activities in different ways. The evolution of these methodologies was described in the first chapter.

Models for design activities are mothered by a design theory, “…a design theory means a

mental structure, adequately validated, representing a design process or a design object…” [37] (p.26).

The design theory consists of the mental model governed by a methodology, “A

methodology can be defined, in a general sense, as a situation-adapted system of methods to solve a complex problem” [37] (p.26).

The methodology gathers the needed methods to develop a product: “…design methodology

basically aims to provide a framework for supporting design activities such as problem definition, establishment of requirements, generation of solutions, evaluation of solutions, and decision-making”

[37] (p.27).

Activities and decision-making in product development are often described as problem solving activities where a present state of the situations is described, as well as the future preferred state [38] (p.2). Goel [39] describes the nature of design problems (activities) by viewing them as a function of abstraction hierarchies. The abstraction hierarchies show how the nature of the output of product development activities change during the design process (see Figure 6). It shows how the focus of decision-making shifts from identifying people with different competencies in order to state the purpose of the future decisions to decisions about functions and properties of the artefact.

Artifact Function Behaviour Purpose People Problem structuring Preliminary design Refinement Detailed design

All these activities are described on a methodological level and are typical for product development methodology literature. Product development literature that describes the specific aspects of importance within the methodology stages in more detail often focuses on specific decisions or aspects that need to be considered during that specific stage. Specific decisions are summarised, for example, by Krishnan and Ulrich [40], and all of them have been extensively researched by the product development research community. Krishnan and Ulrich [40] describe generic product development decisions made at three levels in the organisation: strategic, project management and operational. They divide the decisions into those made when setting up a project and those made during a project. When looking at the product strategy level, five generic decisions are made: (1) what is the market and product strategy to maximize probability of economic success?; (2) what portfolio of product opportunities will be pursued?; (3) what is the timing of product development projects?; (4) what assets (e.g. platforms), if any, will be shared across which products?; and, finally, (5) which technologies will be employed in the product(s)? When looking at a project management level, five other generic decisions are made: (1) what is the relative priority of development objectives?; (2) what is the planned timing and sequence of development activities?; (3) what are the major project milestones and planned prototypes?; (4) what will be the communication mechanisms among team members?; and, finally, (5) how will the project be monitored and controlled? Further, when looking at the operational activity level, eighteen generic decisions (divided into five categories) are made. Those categories are: Concept development, Supply chain design, Product design, Performance testing and validation, and Production ramp-up and launch [40].

In addition, examples of specific aspects considered important in product development literature are uncertainty [41], value [42], and decision structuring [12, 43].

Bras and Mistree [43] define the entities of a process to be hierarchical and are as follows: ¾ Process

o Phases

Events (activities) • Tasks

♦ Decisions

Tasks and decisions require the direct involvement of humans. Phases and events are accomplished by performing tasks and making decisions. The product development process itself is a task for the assigned team to perform. A task may involve different tasks, decisions, phases, and events. Tasks may or may not include decisions, e.g. routine work. [43]

The tasks and activities conducted during product development are increasingly dependent on access to accurate information, extraction, and exchange. Further, the decision makers need to identify and include different expertise and perspectives in order to make informed decisions. All this has made the product development process dependent on collaborative decision-making. [12]

Collaborative decision-making is not the study of one perspective, such as communication, synthesis, or decision analysis; rather, it is the study of them (and many more) as a whole. It is necessary to view making as a whole (i.e. a system) in order to relate decision-making to product development performance.

What is product development performance?

What is product development performance? That question, as literature shows, is not easy to answer. We do know that it is a direct result of our decisions and choices during the product development process.

The characteristics of the development process originated from the design of machine elements. They have changed over time, due to the inclusion of other aspects of the process (e.g. communication, teamwork, and project management). The area of product development has grown to include many aspects of the process, and it has become hard to overlook. It is today a rather fragmented multidisciplinary research area. Horváth [44] (p.155) states: “Engineering design research shows a rather fragmented, if not a chaotic, picture.” This, and the fact that industry does not use or even know of the research-based product development methods and theories [20], makes improvement of the process of developing products a complex task. Engineering design research tends to focus on specific aspects of the process or decisions in order to improve through the identification of, for example, success factors or specific procedures. Examples include [45-48]. Examples of more holistic studies of the process of developing products exist. However, they are often limited to the identification of generic success factors, and do not explicitly relate the factors to decision-making. [8, 49] are examples. Also, synthesises have been made of what specific aspects are considered and decisions made during product development in order to analyse what the content of product development methodology and methods should support. [40, 50] are two examples.

The role of performance aspects of organisational management have been considered important for a long time [51]. The difficulties in investigating performance in product development are discussed by Kerssens-van Drongelen et al. [52], who identified the aggravating characteristics of the performance measurement problem as follows:

“accurately isolating the contribution of R&D to company performance from the other

business activities”

“A second problem with measuring the contribution of R&D to the company is that a part of

the benefits it generates is hardly quantifiable”

“A third issue is the problem of matching specific R&D inputs (in terms of money or

man-hours) and intermediate outputs (research findings, new technologies, new materials, etc.) with final outcomes”

“A fourth major measurement problem is the time lag between R&D efforts and their payoffs

in the marketplace”

“It is consequently considered to be difficult to compare and contrast two projects, as they will

always be different”

“The final problem is the acceptance of performance measurement in R&D”

The research area of performance in product development is a relatively new area of research. Consequently, there are few studies made focusing on performance in knowledge-intense product development [53]. Further, the term performance is often used in product development literature without a clear definition [54]. Terminology, including performance, effectiveness, efficiency, and productivity, is misused and used in a confusing way [55]. There are exceptions, e.g. [56] and [57]. They provide a concept of performance which states that “Effectiveness” plus “Efficiency” equals “Performance”.

Effectiveness in product development is often closely connected to the levels of customer requirements and product development objectives that are met [58-60]. It is the matter of doing the right thing for the customers. Efficiency is closely related to the rapid creation of value and the resources spent [58, 60]. The thought is to spend as little resources in order to create a given output. O’Donnell and Duffy [54] use IDEF0 modelling in order to create a clear definition model of activity performance (see Figure 7).

Input Effectiveness Efficiency Goal Resources Output

The model is to be interpreted as follows: an organizational function, activity, or decision has input, output, a goal, and resources. If output is compared to goal, effectiveness is determined. If the relation between output and input is compared with used resources, efficiency is determined. However, both effectiveness and efficiency are influenced by uncertainty in decision-making. Further, uncertainty can affect the purpose of the decision (i.e. the created value).

Uncertainty in product development is the property of the business environment, and is the result of two forces: complexity and the rate of change [61]. Uncertainty consists of three elements according to Lawrence and Lorsch [62]: lack of clarity of information, general uncertainty of causal relationships between decisions and the corresponding results, and time span of feedback about the results of the decision. If people receive incomplete, uncertain, and wrong information during the decision-making process, they may perceive the environment as uncertain.

Specific sources of uncertainty in product development can be categorised in different ways. Souder and Moenaert [63] (p.485) states that “The four major sources of uncertainty are user

needs, technological environments, competitive environments, and organizational resources. Reducing these uncertainties is the responsibility of the marketing and research and development (R&D) functions within the firm. Because these functions are reciprocally interdependent, their success in reducing uncertainty requires integration and collaboration between them.” Unger and Eppinger [64]

categorise sources of uncertainty as follows: “Technical”, “Market”, “Schedule”, and “Financial”.

Uncertainty is often researched within product development through the identification of generic success factors of certain decisions or performance aspects in order to minimize uncertainty, thereby improving performance. A common approach to the minimisation of uncertainty in product development is to ensure that critical success factors are thought of and that reoccurring problems are proactively counteracted.

Improving the Process of Developing Products

Ulrich and Eppinger [65] (p.12) define the product development process as “…the sequence

of steps or activities which an enterprise employs to conceive, design, and commercialize a product”.

The documentation of an organisation’s product development process may help in identifying opportunities for improvements [65].

Unger and Eppinger [64] also discuss the fact that although different companies’ product development processes are not uniform, they are used in similar ways to minimise

uncertainties and risks. The process of developing products often follows at least some form of the steps seen in Figure 8.

Planning Concept development System‐level design Detail design Test and refinement Production ramp‐up

Figure 8. A generic product development process [65].

“The purpose of PDPs2

that include these steps is to provide a structure for managing the many uncertainties and risks that companies face. Segmenting the process into smaller actions is one way of controlling risks” [64] (p.2).

De Meyer et al. [66] and others stress the need to be aware of certain uncertainties in order to improve product development management [66, 67]. Unger and Eppinger [64] explain the inherited abilities of a structured process to reduce uncertainties through iterations, system integrations (e.g. prototypes), and reviews. Iterations are often used to address market uncertainties, while system integrations and reviews are used to minimise technical uncertainty.

The characteristics of different products influence the choice of process model (methodology) to be used in development organisations. Manufacturing companies tend to use a staged model, while software companies use a spiral one. The staged model uses narrow iteration within phases and rigid reviews, while the spiral model uses comprehensive iterations across phases and flexible reviews. The design and improvement of a product development process should be made through the identification of uncertainties and the prioritisation of risks. Uncertainties and risks should be assigned to iterations, cycles, reviews, or stages of the process. The planning of iterations and integration cycles should be done to address the risks. The last thing is to schedule key reviews. [64]

Clarkson and Eckert [50] (p.25) state that the: “Design process should be tailored to the product

under development, the competence of the design team and the aspirations of the users”. By arguing

for the importance of trying to understand the design process from all points of view, from the individual designer’s problem-solving process to the continuous business development, it is possible to begin to affect the performance of the process. They go on to say that:

“while these models all offer insight into the nature of design projects, they are far too general to help with project planning activities or to guide the daily decisions which must be made by design managers”

[50] (p.25).

Early on, the development process was defined as a sequential “over-the-wall” process [68] where information was completed about the product before passing it on to the next phase in the process. Information is what enables the process and what product design methodology is based on. Depending on what category of information sought, the process can be divided into functions and phases.

The process can be described as “a process of gradually building up a body of information until it

eventually provides a complete formula for manufacturing a new product” [69] (p.158).

As shown in the first chapter of this thesis, collaboration is a vital aspect of product development. It is also dependent on the ability to manage the information exchange between interfaces for upstream and downstream tasks, different sub-systems and different organisational functions. A substantial amount of information has to be coordinated and distributed in product development. The right piece of information should be available to all actors involved in real time [70]. An efficient organisation also has to understand the information-processing logic and its integration with its environment in order to make sufficient decisions.

The success of engineering companies is highly dependent on how well product design information is managed and communicated [71, 72]. Engineering designers use information from a variety of sources to undertake a wide range of design tasks. It has also been shown that engineers spend as much as 30-35% of their time searching for and accessing engineering design information [73, 74]. When engineers gather information, other people are often the most used information source. Without access to accurate, up-to-date information, engineers may make mistakes or misjudgements on aspects of the product design. Groups can sometimes make bad decisions by not considering all relevant information and not appraising the full range of options available [75]. It is also common that engineers prefer to use the information they already possess [76].

In summary, there are many different aspects of the process of designing products that can be used for improving the process. The difficult part of the work is to determine which aspect to choose when trying to improve the process. Wynn and Clarkson [77] (p.35) state that: “There is no silver bullet method which can be applied to achieve process improvement”. However, there have been promising attempts to establish more fundamental aspects of the development process in order to improve the process, i.e. decision-making. Herrmann and Schmidt [78] advocate a change in engineering thinking from a problem-solving to a decision-making approach. “We believe that this gap can be bridged by first understanding how we

came to accept the view of engineering design as problem-solving and how that notion is reinforced by the very organisation structure of our manufacturing enterprises”. Herrmann and Schmidt [78] (p.1)

propose to view product development as a decision production system. “Only a change in the

![Figure 1. My research process [17].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/19.718.102.656.386.635/figure-my-research-process.webp)

![Figure 2. The Design Research Methodology (DRM) [23].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/22.718.96.564.296.628/figure-design-research-methodology-drm.webp)

![Figure 3. Planning a research project, adaptation of [24].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/23.718.191.569.80.294/figure-planning-research-project-adaptation.webp)

![Figure 4. Methodological approaches related to paradigms [25].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/24.718.141.528.113.268/figure-methodological-approaches-related-paradigms.webp)

![Figure 6. Shifting characteristics of the product development process [39].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/32.718.149.536.726.858/figure-shifting-characteristics-product-development-process.webp)

![Figure 7. Effectiveness and efficiency model [54].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/35.718.204.560.630.845/figure-effectiveness-and-efficiency-model.webp)

![Figure 8. A generic product development process [65].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/37.718.111.655.126.176/figure-generic-product-development-process.webp)

![Figure 9. The ideal decision-making model (“The Economic Man”), [89].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4711177.124079/45.718.111.649.73.452/figure-the-ideal-decision-making-model-the-economic.webp)