Master Thesis in Business Administration Program: Global Management

Credits: 30 ECTS

Authors: José Antonio Amador Erik Gustavsson

Supervisor: Matthias Waldkirch

Jönköping May 2020

Managerial Risk-Taking Behaviors of CEOs in Family

Businesses

i

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratefulness towards the people that has been with us through the advancement of our Master’s Thesis. Through worrying times, you have always been there to support us when we needed it the most.

Firstly, our families, we are sincerely thankful for giving each of us your love and heartwarming support. Los amamos desde lo más profundo de nuestro corazón. Secondly, we would like to send our appraisal to the members of our seminar group that dedicated their time and effort to our thesis and gave us essential insights and feedback which aided us during the learning process of our thesis.

Likewise, we would also like to thank our supervisor, Matthias Waldkirch, for his expertise and feedback. His insights and experience assisted us in completing this paper. For that, we are always grateful.

Furthermore, we would like to express our genuine and most humble appreciation to Timur Umans and Caroline Teh for their guidance and supportive roles during this journey.

To end, we would like to take our last chance to show our appreciation towards Jönköping University and all the people we got to know during our studies. We wish you all the best and that you and your loved ones remain safe during this pandemic era. Together we shape the future.

Jönköping, May 18th, 2020

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Managerial Risk-Taking Behaviors of CEOs in Family Businesses Authors: Erik Gustavsson & José Amador

Supervisor: Matthias Waldkirch

Date: May 18, 2020

Key Words: Family Businesses, Family CEOs, Non-Family CEOs, Managerial

Risk-Taking, Upper Echelons Theory, CEOs’ Experiences, Age, Tenure, Education, Prior Work Experiences.

Abstract

Background

Nowadays the amount of research regarding the family business context has improved meaningfully. However, the field of family business could still be considered immature and with existing gaps in its literature. Thereby, several studies in the family business context have discussed the topic of risk-taking, which establishes its crucial importance as a topic within in the field. Thus, risk-taking is a topic of the utmost importance for any given organization in terms of growth regardless if it is a family firm or non-family firm. However, in order to enact such levels of growth, the firms’ CEOs are required to engage in managerial taking behaviors. Here, managerial risk-taking is explained through the lens of the upper echelons theory which aids to understand the different perspectives (e.g., age, tenure, education and prior work experiences) CEOs utilize to take risk in their daily activities.

Purpose

Through the identified fundamental experiences affecting the managerial risk-taking behaviors of CEOs, the purpose of this thesis, through the lens of the upper-echelons theory, is to research how CEOs experiences influence their managerial risk-taking behaviors inside family businesses.

Method

This thesis followed a quantitative research approach, by analyzing a sample of 100 family firms and their CEOs across Scandinavia. Here, the data was collected via the public database “Amadeus” and complemented with supporting sources such as “LinkedIn” and companies’ websites. Lastly, multiple statistical tests were performed to further asses and explore the collected data.

Findings

The final results of this thesis were unable to determine to what degree the independent variables of CEOs’ experiences (age, tenure, education and prior work experiences) influence the dependent variable of managerial risk-taking behaviors. In our case, the controlling variables of firm size and CEOs being part of the board showed to have a significant effect on the managerial risk-taking behaviors of CEOs.

iii

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Problem Discussion

...

31.2. Purpose of the Research

...

52. Literature Review ... 6

2.1. Family Business ... 6

2.1.1. The Family Business Context ... 6

2.1.2. The Family Business Characteristics ... 8

2.1.3. Corporate Governance ... 12

2.1.4. Corporate Governance in Family Business ... 13

2.2. Managerial Risk-Taking ... 14

2.2.1. Managerial Risk-Taking Theories

...

152.3. The Upper Echelons Theory ... 16

2.3.1. The Upper Echelons Theory Addressing CEOs ... 16

2.4. CEOs Experiences ... 17

2.4.1. Age of CEOs ... 17

2.4.2. Tenure of CEOs ... 18

2.4.3. Education of CEOs... 19

2.4.4. Prior Work Experience of CEOs ... 20

3. Hypotheses Development ... 21

3.1. Age of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors ... 21

3.2. Tenure of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors ... 23

3.3. Education of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors ... 25

3.4. Prior Work Experience of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors

...

274. Research Method

...

294.1. Research Philosophy & Strategy ... 29

4.2. Research Design ... 31

4.2.1. Theory Outline ... 31

4.2.2. Empirical Method ... 32

iv

4.3. Variables ... 35 4.3.1. Dependent Variable ... 35 4.3.2. Independent Variables ... 36 4.3.3. Moderating Variable ... 37 4.3.4. Controlling Variables ... 374.3.4.1. Debt to Equity Ratio ... 37

4.3.4.2. Board Size ... 38

4.3.4.3. Family Directors ... 38

4.3.4.4. CEOs as part of the board ... 38

4.3.4.5. Firm Size ... 39 4.3.4.6. Industry ... 39 4.3.4.7. Gender ... 39 4.3.4.8. Region ... 40 4.4. Data Analysis ... 40 4.5. Research Ethics ... 40 4.6. Research Quality ... 43 5. Analysis

...

44 5.1. Descriptive Statistics ... 44 5.1.1. Dependent Variable ... 45 5.1.2. Independent Variables ... 45 5.1.3. Moderating Variable ... 46 5.1.4. Controlling Variables ... 48 5.2. Spearman’s Correlation ... 495.3. Multiple Linear Regression ... 56

5.3.1. Multiple Linear Regression with Debt to Equity ... 58

5.4. Interpreting the Hypotheses ... 61

6. Conclusion

...

626.1. Discussion ... 62

6.2. Concluding Remarks... 67

6.3. Reflections ... 68

6.4. Limitations ... 69

v

7. References

...

728. Appendix

...

79List of figures & Tables

Figures

Figure 1. “Two and three-circle models”...

10Figure 2. “Managerial Risk-Taking Theoretical Frameworks”

...

15Figure 3. “Determining the strengths of the relationships”

...

50Tables

Table 1. “Family firms’ identities and key characteristics”...

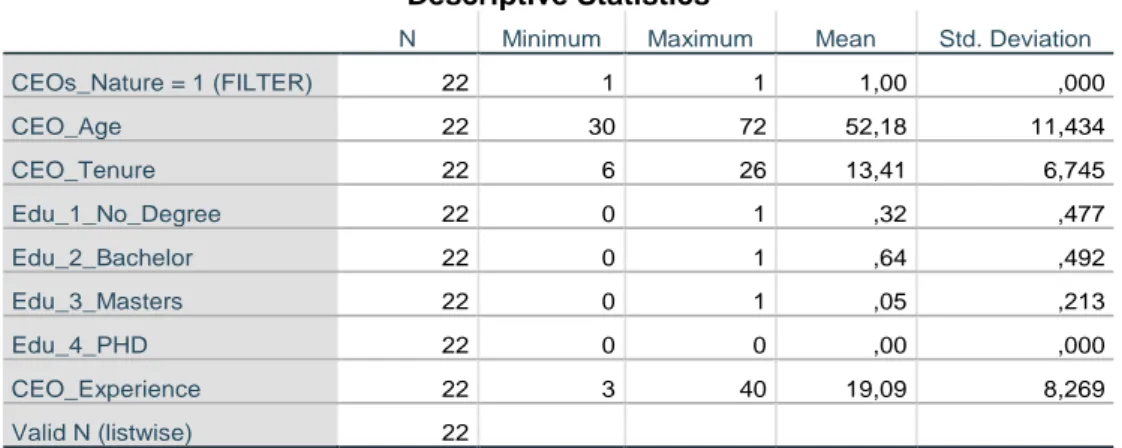

11Table 2. “Descriptive Statistics” of all variables

...

44Table 3. “Descriptive statistics” Dependent Variable

...

45Table 4. “Descriptive Statistics” Independent Variables

...

46Table 5. “Descriptive Statistics” Moderating Variables

...

46Table 6. “Descriptive Statistics” Non-Family CEOs

...

47Table 7. “Descriptive Statistics” Family CEOs

...

47Table 8. “Descriptive Statistics” Controlling Variables

...

49Table 9. “Test of Normality” for the Performance Variability

...

49Table 10. “Spearman's Correlation Matrix”

...

51Table 11. “Spearman's Correlation Matrix” Family CEOs

...

54Table 12. “Spearman's Correlation Matrix” Non-Family CEOs

...

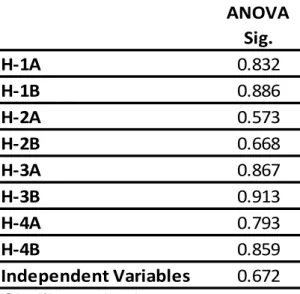

55Table 13. “ANOVA Summary” for Hypotheses and Independent Variables

.

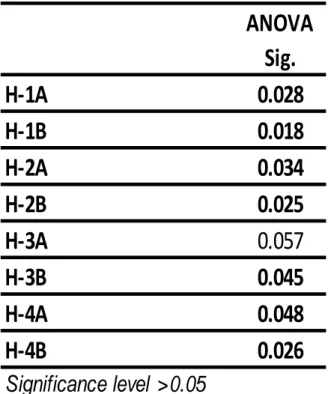

57 Table 14. “ANOVA Summary” for Hypotheses with Debt to Equity as Dependent Variables...

58Table 15. “Multiple Linear Regressions” with Debt to Equity as Dependent Variable

...

601

1.

Introduction

The first section of this thesis will be dedicated to introduce the relevance and importance of managerial risk-taking behaviors of CEOs inside family firms. Here, this section focuses on providing awareness to why the topic is important and how previous studies addressed the matter utilizing the upper echelons theory as a lens to comprehend the outcomes of this phenomenon.

Given the vast literature on Chief Executive Officers (CEOs), there is an ongoing and established discussion about the impact CEOs have over the managerial outcomes of the organizations they control (Busenbark, Krause, Boivie, & Graffin, 2016; Fitza, 2017; Quigley & Graffin, 2017). Widely considered as the most influential individual in an organization, then again, CEOs are depicted to have a crucial impact on any given firm’s strategy and growth (Busenbark et al., 2016; Finkelstein, Hambrick, & Cannella, 2009; Quigley & Graffin, 2017). Here, family businesses are not excluded, and several authors in this field have debated on the impact family firms’ CEOs might have on companies’ managerial outcomes (Huybrechts, Voordeckers & Lybaert, 2013; Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes 2007; Garcia-Granero, Llopis, Fernandez-Mesa & Alegre 2015).

Moreover, it is widely known among researchers that family firms are the most common kind of business around the world. According to Poza and Daugherty (2014) and Aldrich and Cliff (2003), 90% of the businesses around the world are owned by families, employing approximately 50 to 75% of the total workforce across the world. Consequently, it is inevitable not to understand its impact on the global economy. Moreover, Gedajlovic, Carney, Chrisman and Kellermanns (2012), stated that academics had spent efforts on researching family firms during the last two decades. Here, due to the impact family businesses have on the world’s economy. Up to date the amount of research on the family business context has increased significantly. However, as supported by Poza and Daugherty (2014), the field of family business could still be considered immature with several gaps in its literature (Hoskisson, Chirico, Zyung & Gambeta, 2017).

2

Hence, several studies in the family business research have discussed the topic of risk-taking, which demonstrates its crucial importance as a topic within in this field. For instance, Naldi, Nordqvist, Sjöberg and Wiklund (2007) and Huybrechts et al. (2013), draws on this by referring to risk in family firms in terms of entrepreneurial risk, whereas Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007), talks about business risk and socioemotional wealth. Further scholars have stated that the exposure to risk-taking behaviors are crucial for any firm to innovate and increase its performance (Zahra & George, 2002). Thus, in order to enact growth CEOs are required to engage in risk-taking behaviors (Garcia-Granero et al., 2015). Moreover, academics such as, Wang, Holmes, Oh and Zhu (2016), Hoskisson et al. (2017) and Nobre, Grable, Silva and Nobre (2018), identified the importance of risk-taking behaviors of CEOs inside family firms. Henceforth, referred to as managerial risk-taking behaviors. Here, according to Hoskisson et al. (2017), managerial risk-taking is defined as a critical aspect of strategic management in order to increase competitive advantages and performances inside a firm. It is important to understand that CEOs are required to take risk in order to enact growth inside a firm. Therefore, it is important to comprehend the multiple perspectives CEOs could have when pursuing institutional goals and their disposition to participate in risk-taking behaviors (Wang et al., 2016; Nobre et al., 2018).

Thus, a valuable tool to measure and comprehend such perspectives is the upper echelons theory (UET). The UET is a theoretical perspective that provides methods to understand and describe how CEOs behave and perform inside a firm (Wang et al., 2016). According to the founders Hambrick and Mason (1984) and Hambrick (2007), the UET encompasses the experiences, values and personal traits of CEOs in order to understand what influence their choices and behaviors. Thus, the UET tries to explain the motives behind their reasonings, actions and risk-taking behaviors. Furthermore, Wang et al. (2016), expands on the thought of having two main groups to understand CEOs characteristics. Thus, such groups are the CEOs experiences and CEOs personalities. Hereby, when referring to CEOs experiences Wang et al. (2016), argues that they are all the previous backgrounds and knowledge CEOs apply to make decisions inside a firm. Such experiences are categorized in four main forms age, tenure, education and prior work experiences (Wang et al., 2016; Abatecola & Cristofaro, 2018).

3

Finally, multiple studies in the family business context have applied the UET to apprehend the different behaviors CEOs utilize when engaging in risk-taking behaviors inside family firms. Wang et al. (2016), explains the behaviors CEOs have when engaging in risk-taking activities by analyzing their experiences (age, education, tenure and prior work experience) and personalities. Moreover, Farag and Mallin (2018), explains how CEOs act when they engage in risk-taking behaviors, by utilizing the UET as a lens to explain their demographic characteristics. Lastly, Martino, Rigolini and D’onza (2020), examines the influences of CEOs personal characteristics such as, age, education, tenure and prior work experiences on their risk-taking behaviors by employing the UET. Hereby, according to these previous studies, results has shown that CEOs experiences affects their managerial risk-taking behaviors.

1.1. Problem Discussion

According to Nobre et al. (2018), risk-taking is a topic of the utmost importance for any given organization. Scholars have stated that the exposure to risk-taking behaviors inside a firm is crucial for any firm to innovate and increase its performance. Thus, several authors have declared the importance of further research in the family business context addressing the risk-taking behaviors of CEOs (Wang et al., 2016; Hoskisson et al., 2017; Nobre et al., 2018). Here, it is important to recognize that CEOs will act according to their own experiences, values and personal traits and thus, engaging in managerial risk-taking behaviors in order to facilitate growth inside their firms.

Furthermore, it is important to understand how these experiences interfere with the CEOs’ managerial risk-taking behaviors. As described above, these experiences are divided into the four main categories of age, tenure, education and prior work experience (Wang et al., 2016; Abatecola & Cristofaro, 2018). For instance, according to Wang et al. (2016), there is a negative relationship between risk-taking behaviors and the CEOs’ age and tenure whereas there is a positive relationship with their education and prior work experiences. However, there is an existing gap in the literature to explain the different ways these experiences influence a CEO risk-taking behavior and thus, the performance of the firm.

4

Yet, when considering the CEOs role in the family firm then, in accordance with Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman (2018), it could be argued that the family firm research has made considerable contributions in understanding the challenges and complexity associated with the involvement of both family as well as non-family CEOs in family firms. However, like in most fields, it exists some gaps that calls for further insight. For instance, the condition of a family CEO versus a non-family CEO is indicated to have an impact on the family firms´ risk taking (Stanley, 2010). Therefore, Tabor et al. (2018), calls for further research into differentiating between family CEOs and non-family CEOs and how they influence the risk-taking behaviors within the firm. Given the family CEOs desire to retain control, tentative issues of diluting ownership and desire to maintain their legacy, then scholars argue that family CEOs are found to act more conservatively in their risk-taking behavior compared to non-family CEOs (Stanley, 2010; Gentry et al., 2016).

Therefore, when reviewing the literature about risk-taking behaviors of family firms’ CEOs, with support of previous studies, we identified that the UET is a useful tool to recognize how CEOs’ experiences affect their managerial risk-taking behaviors. According to Hambrick and Mason (1984), Garcia-Granero et al. (2015) and Hoskisson et al. (2017), CEOs will act according to their own experiences, values and personal traits. Hence, the upper echelons theory tries to explain the motives behind their reasonings, actions and risk-taking behaviors (Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Wang et al., 2016; Hoskisson et al., 2017; Benischke, Martin & Glaser, 2019). Hence, based on the calls of Wang et al. (2016), Hoskisson et al. (2017) and Tabor et al. (2018), we desire to further investigate CEOs’ experiences and how it affects their managerial risk-taking behaviors, by applying the UET inside the family business context.

5

1.2. Purpose of the Research

Because of the research gap identified in the section above, the purpose of this thesis, through the lens of the upper-echelons theory, is to research how CEOs experiences influence their managerial risk-taking behaviors inside family businesses.

In line with our research purpose, stems the following research questions that shall be tested through the course of this study:

(1) How does CEOs experiences influence their managerial risk-taking behaviors inside family businesses?

(2) How does family CEOs’ experiences differ from non-family CEOs in terms of managerial risk-taking behaviors?

For this thesis, our aim is to provide with a relevant contribution to the existing research in this field by expanding on CEOs experiences and how they affect their managerial risk-taking behaviors. Therefore, by applying the upper echelons theory, this study wants to contribute to a better understanding of CEOs in the family business context. Given that this topic has received increased attention in the academic discourse in recent time, we strive to present further essential insights on the researched topic that could aid the ongoing evolution of this topic.

6

2.

Literature Review

The following section of this thesis will be dedicated to present relevant and fundamental theories that will serve as the foundation of this paper. The exhibition of the selected theories aims to offer the reader with a synopsis on the theoretical background of the given research topic. The primary sections are outlined to display the contemporary progression of the family business literature by specifically draw upon the family business context, its characteristics, and its unique composition of governance with emphasis on the family involvement. Here, the latter part of this section will discourse the Upper Echelons Theory and address this to family business’ CEOs in regard to their managerial risk-taking behaviors.

2.1. Family Business

2.1.1. The Family Business Context

In general, there is no single nor agreed formal definition of family business and when examining the family business literature, it is somewhat difficult to find an all-encompassing consensus among scholars on this matter (Chua, Chrisman & Sharma 1999; Litz, 1995). For instance, Chua et al. (1999), argues around the notion that a family’s involvement in the business is what makes the family business unique in its setting. Consequently, Chua et al. (1999), also highlight the importance of a theoretical definition that could identify and distinguish family businesses from other non-family businesses.

Moreover, in the inaugural issue of the Family Business Review, Lansberg, Perrow and Rogolsky (1988), raised the question of: what is a family business? According to the authors, then the term `family business` is basic in its common usage and allows for simpler understanding however, offering a coherent and comprehensible definition is challenging due to the complexity of this phenomena. Here, it also suggested that a family business is “a business in which members of a family have legal control over ownership” (Lansberg et al., 1988).

7

Ever since, scholars and researchers have tried to resolve this issue of a unified definition, mainly through debating and reviewing existing definitions in order to reach a latent consensus. This, in effort to define the phenomena of family business are mainly on the reasons of differentiating it from, as referred to, non-family businesses (Sharma, 2004). Most definitions of the family business and family firm derives from family ownership, family involvement, family control and intentions of potential succession to future generations (Lansberg et al., 1988; Chua et al., 1999; Litz, 1995; Westhead & Cowling, 1998).

Here, the beforementioned are all examples of scholars who offer an overview of existing definitions as well as implying their own interpretation on what stipulates a family business. Strikingly, even though most authors argue that their definition is superior to others, there is a unison consensus among the majority that the most crucial issue is that each researcher should stay consistent on which definition to use in their own study.

Correspondingly, this is essential to take into consideration due to the difference between family firms and not solely the difference between non-family firms and family firms (Sharma, Chrisman, & Chua, 1997). For any researcher exploring the family business context it is vital if not of highest priority to grasp the understanding of the heterogeneity of family firms (Chua, Chrisman, Steier, & Rau, 2012). Since much research in this field have devoted attention in the comparison of family and non-family businesses, Chua, Chrisman, Steier and Rau (2012), Melin and Nordqvist (2007), and Nordqvist, Sharma and Chirico (2014), then argues on an increased understanding of the heterogeneity in family firms and for instance, how the differences in family involvement might display the heterogeneity among family firms.

As discussed above, the difficulties in agreeing upon a universal definition as well as highlighting each family firms’ differences (Lansberg et al., 1988; Chua et al., 1999; Litz, 1995; Westhead & Cowling, 1998), could specify an essential indicator that illustrates the heterogenous nature of family firms (Chua et al., 2012). Due to the significant variations of family involvement in ownership and management in family firms then simply put, studies about family firms must not solely be able to distinguish between family and non-family firms but ought to explain discrepancies among family firms as well (Melin & Nordqvist, 2007; Nordqvist et al., 2014).

8

Taken together, this variety of different definitions displays the complexity and heterogeneity between the various definitions as well as within the family firms. Thus, in order to stay consistent, we will utilize Chua et al. (1999) definition in which it is contended that the family business is defined by its specific behavior and how this component in relation to the family involvement are used to pursue the family’s vision. As, Chua et al. (1999) describes, family involvement is the core source of what differentiates family businesses from other businesses.

“The family business is a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled

by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.” (Chua et al.

1999, p. 25)

Furthermore, if a family business is a matter of behavior of the people who govern and/or manage the firm, then they must behave as they do to fully serve a purpose. It is then believed that this purpose is to form and pursue the objectives of the dominant coalition in the firm (Chua et al., 1999). Here, as suggested by Hambrick and Mason (1984), the dominant coalition includes the powerful actors within the family firm who control the organizational agenda.

2.1.2. Family Business Characteristics

After considering the different definitions and heterogeneity of family firms, a modest distinction between family and non-family firms may not be adequate to explain firm outcomes within this context. Therefore, exploring the reasons that drives these differences among the family businesses is of vital importance in order to manage and understand its twofold nature (Stewart & Hitt, 2012). Principally, family firms are unique in their setting in terms of the interaction between the two distinct logics of- family and the business (Sundaramurthy & Kreiner, 2008).

9

The family logic emphasizes a non-economic value that is generated through the satisfactions of needs as well as ensuring the family’s well-being. Henceforth, the business logic highlights economic growth and business development in general. Then for the governance of the family firm, due to the circumstance that these two logics not necessarily coincide, it becomes paramount to manage the trade-offs between preserving the family value and to create economic value (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Further, according to Sundramurthy and Kreiner (2008), then the formation of family firm identity is inherently dependent on the relationship between these two logics since the latter not always correspond with the owner-family’s intentions. Thus, the family firm identity applies beyond the perceptions of the family and the business and by so distinguishing characteristics of an organization that make it distinctive. Often, this distinction refers to the essence of “who we are as a family business” and the family firm identity provides a common set of values and beliefs that aligns and coordinates the family firms’ decision making (Arrengle, Hitt, Sirmon & Very, 2007; Reay, 2009; Shepherd & Haynie, 2009).

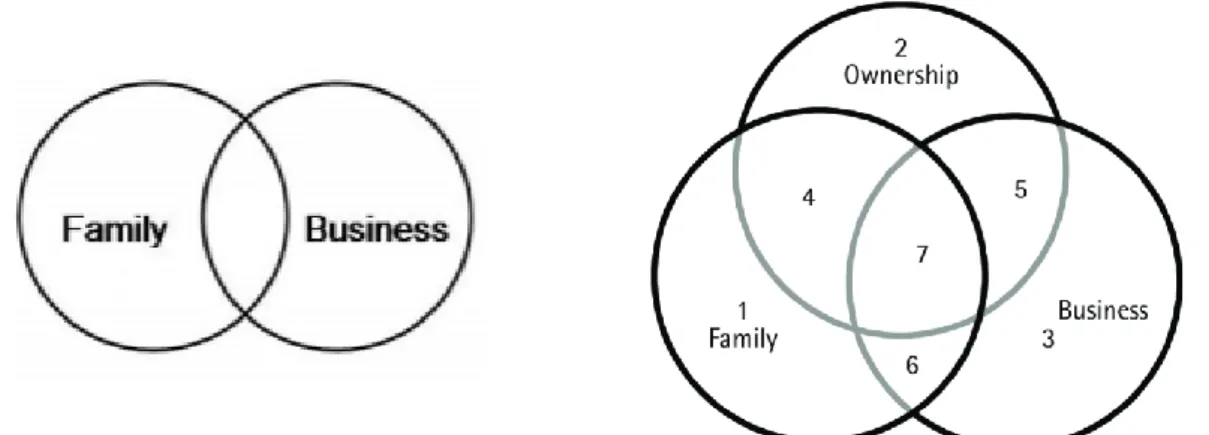

Moreover, in the early 1980’s, Tagiuri and Davis (1996) argued around the implementation of a more accurate model that could portray the full range of family firms. Emerging from this, the two-system theory was constructed that included two overlapping circles of the family respectively the business component to illustrate the interaction of family and business subsystems (figure 1). Yet building on this, Gersick, Davis, McCollom and Lansberg (1997) contended that the family firm consists of not just two, but three independents, hence overlapping subsystems (figure 1). Here, instead of the two-system model (figure 1), the three-circle model describes the subsystems of family, business, and ownership in which any individual in the given family firm can be located within one of the seven sectors formed by the overlap of the three dimensions (Gersick et al., 1997).

These overlapping circles are useful in terms of explaining the behavior of the family firm, describing the complex individuals as well as organizational phenomena coupled with the overlapping subsystems and when identifying stakeholder perspectives, roles and responsibilities (Habbershon, Williams & Mcmillan, 2003). As stated above, by exploring the three-circle model, any individual in the family firm can be placed within the overlapping circles.

10

For instance, owners will be found within the top circle of ownership. Likewise, family members will be put in the bottom left circle (family) and employees without ties to ownership and family will be placed in the bottom right circle (business). Moreover, family members who is neither employee nor owner will be found within sector 1 hence, all individuals with multiple ties will be placed in one the overlapping sectors (4,5,6,7, as displayed below) depending on their connection to the family business (Gersick et al., 1997). Adding to the model suggested by Tagiuri and Davis (1996), Gersick et al. (1997), and Habbershon et al. (2003), then Pieper and Klein (2007) propose an extended model that accordingly, accounts for the unique characteristics, diversity and complexity of the family firm and its subsystems. Per to the authors, then family firms’ subsystems are far more complex than what have been conceptualized in earlier models. Henceforth, by extending abovementioned models, Piper and Klein (2007) includes the management subsystem into the existing components of family, ownership, and business.

In what they refer to as the “Bullseye”, an open system approach is offered to complement and expand earlier proposed models in this field of study (e.g. Tagiuri & Davis, 1996) and Gersick et al., 1997). However, the lack of empirical testing puts this theory into the shadow of the works conducted by abovementioned authors. Therefore, this thesis will take the Gersick et al (1997) into consideration while assessing the family firms in this research. Mainly, since several scholars have used this as a basis for their work when analyzing the family firm, but also since it is a widely accepted concept in the field of family firms.

Figure 1. “Two and three-circle models” (Own creation based on, Tagiuri & Davis (1996) and Gersick

11

Furthermore, in a recent research presented in “The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity Among Family Firms”, Ponomareva, Nordqvist and Umans defines two distinct identities of family business: namely, clan and financial family business identities (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 89-97). According to the authors, then the two types of identities represent two sides of a scale rather than two separate classifications. Here, both identities combine family and business logics, with for instance family identity dominating the other or vice versa. (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 92). Subsequently, together they constitute, as suggested by Shepard and Haynie (2009) and Revy (2009), a firm meta-identity, an integrated identity that a given firm adopts and communicates to its stakeholders.

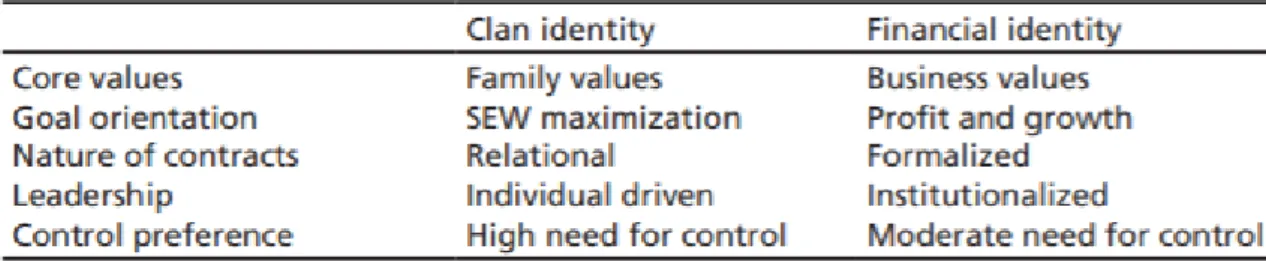

Hence, exemplified more straightforward, when the family logic prevails over business logic, the greater the likelihood of a family business to adopt and communicate a clan identity. Comparably, with business logic prevailing family logic, the greater the likelihood of the family business fostering and adopting a financial family business identity (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 92). Consequently, as shown in Table 1, these two identities then consist of different characteristics that define the above described identities.

Table 1. “Family firms’ identities and key characteristics” (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 97).

As displayed above, family business that are characterized by clan identity possess some distinctive characteristics. Principally, they include the occurrence of strong family values and emphasis on family wealth maximization as suggested by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007). Moreover, it also stressed that clan family firms are more dependent on pursing the desire to remain in control of decision making and more likely to acquire an individual driven leadership structure represented with a broad involvement of family members in management (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 94).

12

On the contrary, in the financial family firm identity, the distinctive characteristics includes a stronger emphasis on business values, profit orientation and growth. A more outward-looking leadership structure induces a more moderate need to remain in control for the owner family (Memili & Dibrell, 2019, p 96).

To summarize, for any research it is important in understanding how family firms manage the coexistence of the two logics of family and business. The notion of firm identity could be utilized as a tool to reconcile the tension between the two parameters and provide a unified understanding of the family firms purpose, goal and how this identity affects the risk-taking behavior of family CEOs as well as non-family CEOs.

2.1.3. Corporate Governance

Governance is widely seen as a determining factor in the success and failure of all organizing activity. Typically, it could be viewed as the consequences derived from the formal decisions taken internally by a firm’s managers, owners and board members to manage and control the behavior of organizational members (Daily, Dalton & Cannella, 2003; Carney, 2005; Steier, Chrisman & Chua, 2015). Here, corporate governance could be referred to as ‘‘the determination of the broad uses to which organizational resources will be deployed and the resolution of conflicts among the myriad participants in organizations’’ (Daily et al., 2003, p. 371). Hence, it covers two major obligations that is: setting the firms strategic direction along with striking a balance between the interests of the firm’s dominant coalition and its various stakeholders (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003; Steier et al., 2015). Likewise, governance structures are also indicated to be in charge of directing, controlling and influencing the managerial risk-taking behaviors inside the business (Palmer & Wiseman, 1999; Long, Dulewicz & Gay 2005; Lorsh & Clark, 2008).

13

2.1.4. Corporate Governance in Family Business

Like in most cases of research on family businesses, a large portion of the studies regarding corporate governance in family firms is derived from attempts to distinguish it from the its non-family businesses counterpart (Mustakallio, Autio & Zhara, 2002; Nordqvist et al., 2014; Chrisman, Chua, Le Breton-Miller, Steier & Miller 2018). For instance, Mustakallio et al. (2002) suggests that the governance of family firms diverges from conventional corporate governance in an important regard: its important owners, namely the family members who may possess multiple roles and positions in the family business. Once more, this distinction could similarly be portrayed through the competing agendas of the two dimensions of the family and the business. Accordingly, derived from the interaction of these two dimensions, the governance structures in family businesses is ought to reflect the complexity emerging from this (Mustakallio et al., 2002; Corbetta & Salvato, 2004). Principally, these governance structures must act by responding to the many needs of the family firm and its stakeholders. This includes the need for formal control in terms of monitoring, and a need for relational and social control that could encourage unity and a shared vision (Mustakallio et al., 2002).

Furthermore, the after mentioned contribution of Tagiuri and Davis (1996) three-circle model displays some evidence on the lack of separation of family, ownership and business within the family business. According to the authors, family businesses normally represents a complex and longstanding stakeholder structure that is comprised by the board of directors, top management and family members. Here, as also discussed by Mustakallio (2002), the owner-family’s member plays as a crucial denominator in family business governance, since they typically play a part in multiple roles in these different governance bodies (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). Ultimately, this notion could serve as a hint to why the family business governance diverges from mainstream governance.

Distinguished from its non-family firm counterpart, the aspect of family involvement introduces a unique element to governance in the family firm. Family involvement is commonly referred to as the mechanism utilized to certify that the actions of organizational stakeholders remain consistent with the goals and objectives of the dominant coalition (Chua et al., 1999; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003).

14

Here, Chrisman et al. (2018) contends that family firms deviate from, for instance publicly held corporations, due to the concentrated ownership help by a small number of family owners who constitute the dominant coalition. Moreover, Habbershon et al. (2003) contends that the degree of family involvement affects the objectives and interests in family business and by so differentiate them from their non-family counterparts. In accordance, Bennedsen, Pérez-González and Wolfenzon (2010), states that the family businesses are unique in their setting in which their governance, to a large degree, is determined by the governance of the owner-family and their interests of the firm.

2.2.

Managerial Risk-Taking

As mentioned in the problem discussion (section 1.2), risk-taking is a topic of the utmost importance for any given organization. It does not matter if it is a family firm or non-family firm it will always be imperative to identify what could go wrong and how to avoid or prevent it. According to Nobre et al. (2018), risk denotes the levels of uncertainty linked to decision making and execution of activities when pursuing goals or specific outcomes. Many scholars have stated that the exposure to risk-taking behaviors inside a firm is crucial for any firm to innovate and increase its performance (Wang et al., 2016; Hoskisson et al., 2017; Nobre et al., 2018). Afterall, the capability of a firm to enact innovation is vital to sustain competitive advantages (Zahra & George, 2002). Thus, in order to enact such levels of innovation firms are required to engage in risk-taking behaviors (Garcia-Granero et al., 2015).

Hereby, managerial risk-taking is defined as a critical aspect of strategic management in order to increase competitive advantages and performances inside a firm (Hoskisson et al., 2017). It is important to understand that CEOs are required to take risk in order to enact growth inside a firm. Therefore, as stated above, it is of the utmost importance to comprehend the multiple perspectives CEOs could have when pursuing institutional goals and their disposition to participate in risk-taking behaviors (Wang et al., 2016; Nobre et al., 2018).

15

2.2.1. Managerial Risk-Taking Theories

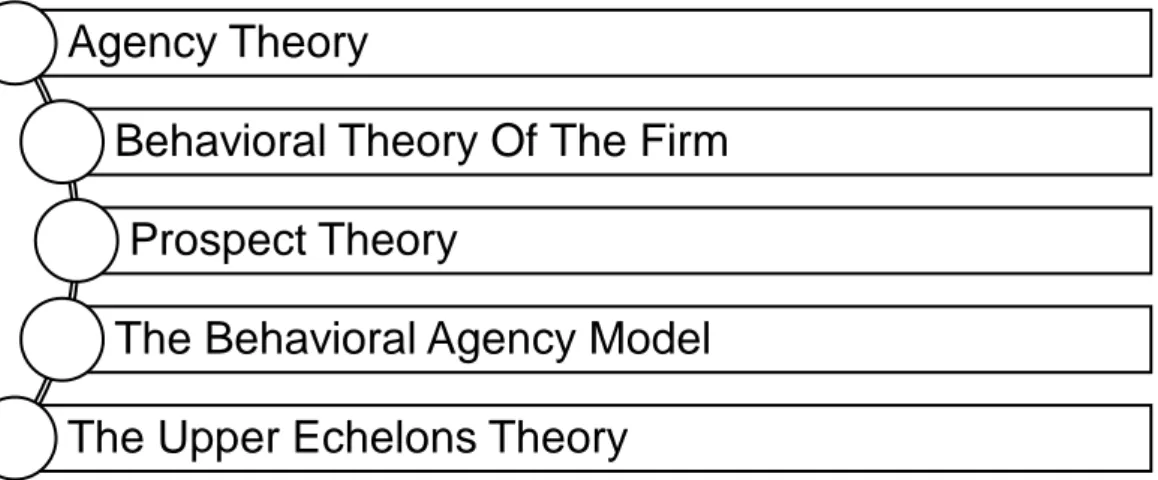

The managerial risk-taking literature provides many different theoretical frameworks (as shown in Figure 2.) (Hoskisson et al., 2017). First, the agency theory. The agency theory aids to understand problems and conflicts occurring between the corporate governance structure of a firm and its CEOs (Nobre et al., 2018). Second, the behavioral theory of the firm supports the idea of institutions pursuing risk-taking behaviors according to their performance (Cyert & March, 1963). Third, the prospect theory is enlightened under the criteria that individuals are “lose averse” (Hoskisson et al., 2017). According to Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire (2011), individuals encounter to have greater discontentment in losses than pleasures in earnings when expose to high levels of risk with low or equal levels of return.

Fourth, the behavioral agency model incorporates all the previous theories. Thus, this theory undertakes the thought that individuals are loss averse and their earnings projections generates a tolerance point in which they will decide their risk-taking behaviors (Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998). Fifth, the upper echelons theory aids us to comprehend the different perspectives CEOs utilize to take risk in their daily activities. Such perspectives are their experiences and personal traits (Hambrick and Mason,1984; Garcia-Granero et al., 2015).

Figure 2. “Managerial Risk-Taking Theoretical Frameworks” (Hoskisson et al., 2017).

Agency Theory

Behavioral Theory Of The Firm

Prospect Theory

The Behavioral Agency Model

The Upper Echelons Theory

16

2.3. The Upper Echelons Theory

The upper echelons theory (UET) is well-thought as a significant theoretical perspective to understand and describe how CEOs behave and perform inside a firm (Wang et al., 2016). According to Hambrick and Mason (1984), Hoskisson et al. (2017) and Benischke et al. (2019), the UET encompasses the experiences, values and personal traits of executives in order to understand what influence their choices and behaviors. Thus, the UET tries to explain the motives behind their reasonings, actions and risk-taking behaviors. Additionally, Hambrick (2007) and Hoskisson et al. (2017), argued that the UET works under two main constructs. First, executives act on behalf of their personal understandings. Second, the personal constructs of the executives are the result of their own values, experiences and personal traits.

After reviewing the literature about the UET two main moderators are mentioned managerial discretion and executives’ job demand. Hambrick (2007), expands in the idea of managerial discretion by defining it as the influence of executives inside the organizations. Thus, managerial discretion occurs when there is a weak presence of the governance body inside the firm. Executives’ job demand, by the other hand, is defined by Hambrick (2007), as the performance of executives under high levels of pressure. Moreover, executives’ job demand originates from three main aspects task challenge, performance challenges and executives’ aspirations.

2.3.1. The Upper Echelons Theory Addressing CEOs

As mentioned earlier, the UET help us to comprehend what is behind the actions and behaviors of CEOs inside the firms. According to Hambrick and Mason (1984), Hoskisson et al., (2017) and Benischke et al., (2019), the CEOs will act according to their own experiences, values and personal traits. However, Wang et al. (2016), expands on the thought of having two main groups to understand CEOs characteristics. Thus, such groups are the CEOs experiences and CEOs personalities. The first group “CEOs experiences” comprehends four indicators age, tenure, education and prior work experiences. Meanwhile the second group “CEOs personalities” identifies how CEOs understands the firm, their own competences and their surroundings. Henceforth, this research drives its focus on expanding in depth the first group “CEOs experiences.”

17

2.4. CEOs Experiences

Custódio and Metzger (2014), addressed the importance of CEOs’ experience by arguing about the importance of previous education and personal traits of CEOs. Thus, they are accountable of affecting the performance of their respective firms. Hereby, when referring to CEOs experiences Wang et al. (2016), argues that they are all the previous backgrounds and knowledge CEOs apply to make decisions inside a firm. Such experiences are categorized in terms of age, tenure, education and previous work experiences (Wang et al., 2016; Abatecola & Cristofaro, 2018).

Moreover, according to Hamori and Koyuncu (2015), they might be numerous conditions on why the different boards of directors are addressing closer attention to the CEOs experiences before choosing one. These conditions are due to the distinctiveness and high responsibilities of the position. Therefore, a family firm is not too far away from these thoughts. Hence, just like any other firm a family firm must select the perfect candidate to occupy the CEO position regardless if it is a family or non-family member (Tabor et al., 2018). According to Aráoz and Ritter (2015), the most important qualifications a CEO must possess are strategic orientation, understanding of the market, result orientation, customer care, leadership, collaboration, team building, change leadership and organizational development.

2.4.1. Age of CEOs

Wang et al. (2016), argues that age of CEOs is an important sign of experience inside the UET context. Belenzon, Shamshur and Zarutskie (2019), identified the different behaviors and performances of firms with CEOs of diverse ages. Thereto, their findings suggest that creativity of CEOs tend to diminish with age. Moreover, managerial styles also alter depending on the age of the CEOs. Consequently, they argued that CEOs incline to focus on the survival of the firm rather than higher profits and growth. On the other hand, Hambrick and Mason (1984), claimed that younger CEOs tend to take more risk in their procedures. Moreover, when compared with older CEOs younger CEOs have more difficulties to identify the full extent of their strategy’s choices due to their lack of experience and knowledge.

18

Cline and Yore (2016), argued that managerial skills of CEOs are vital to add value to any firm. However, even though age of CEOs is a factor that could be negatively connected to the performance of the firms, the authors stated that experience is shadowed by age. Hereby, some CEOs dedicate their entire careers and efforts into their firms developing firm specific qualifications.

When looking it through the family business context academics focus more on the owner’s age and how it affects the family firm. According to Marshall, Sorenson, Brigham, Wieling, Reifman and Wampler (2006), owners age is negatively connected with conflict management inside the firm. Consequently, as CEOs begin to age, they tend to be more conservative, more risk averse, less flexible and to make decisions based only on their own sources of information. Moreover, the owners age is also directly link to the importance of developing succession initiatives within the family firm. Owners aging in family businesses increase the awareness of succession due to disability, retirement, pressure from heirs or even death (Miller, Steier & Le Breton-Miller, 2003).

2.4.2. Tenure of CEOs

According to Finkelstein (2009), one of the most noticeable characteristics of the UET is the tenure of CEOs. Tenure denotes the amount of time an individual has been in charge of the CEO position in a firm (Boling, Pieper & Covin, 2016). Moreover, according to Wang et al. (2016), there are two main components which explains the relationship between the tenure of CEOs and firms’ performances. The first component refers to the career progression of CEOs inside the company. Hereby, CEOs are more worried about conserving their image and legacy than engaging in riskier activities that may harm their legacy. The second component mentions the power CEOs have accumulated along the years. Therefore, all the knowledge, skills and competences acquired during the years by CEOs will reduce the pressure exerted by stakeholders.

19

According to Tsai, Hung, Kuo and Kuo (2006), family and non-family CEOs encounters diverse managerial opportunities while they progress through their careers inside the family firm. Thus, this progression will depend on how the family firm is defined (e.g. ownership, family participation, number of generations and the governance) (Sirmon, Arregle, Hitt & Webb, 2008). Moreover, according to Boling et al. (2016), in early tenure steps CEOs expose themselves to riskier activities, innovations and new strategies. Nonetheless, these efforts could be hinder due to their lack of knowledge and power. Meanwhile, during later steps, CEOs reduce their risk exposure and innovation efforts due to their strong desire of protecting their legacy and the financial status of the family firm. In addition, Wang et al. (2016), mentions that the strategic actions of a firm will decrease meanwhile the tenure of CEOs is increasing.

2.4.3. Education of CEOs

Education of CEOs discusses the sum of prior studies CEOs went through in their academic years or the amount of degrees they possess (Wang et al., 2016). According to King, Strivastav and Williams (2016), there is a strong relationship between the cognitive abilities of CEOs, their level of education and their decision making. Moreover, the mental capacity of CEOs will help determine their reaction time in adverse situations. Thus, well-educated CEOs will demonstrate higher levels of patience and serenity during troublesome periods or scenarios by acting calmly and not by impulse.

Additionally, Wulf and Singh (2011), provides some thoughts in the importance of acquiring educated CEOs for increasing the performance of any firm. CEOs are considered important assets for any business due to their unique sets of expertise and skills. According to Chen, Gao, Zhang and Zhu (2018), human capital are knowledges, habits, personalities and social attributes and individual possess to enact economic growth and value. Thereto, CEOs with valuable human capital can enhance the competitive advantage of any firm. Furthermore, Pascal Mersland and Mori (2017), stated that firms with well-educated CEOs perform meaningfully better when developing the social and financial aspects of a firm than CEOs without academic backgrounds.

20

2.4.4. Prior Work Experiences of CEOs

Former work experience of CEOs encompasses all the amount of time individuals invested in diverse roles and positions before becoming the CEO of a firm. Thus, according to Wang et al. (2016), the UET states that early work experience of CEOs outlines their strategic decision making within three types: functional experience, strategic action and industry experience. Thus, previous work experiences of CEOs will affect their knowledge, skills, values, the way in how they perceive information, how they hunt for data and how they apply it in order to execute their decisions (Dearborn & Simon, 1958).

However, in the family business context the previous work experience of CEOs might not be a crucial factor when hiring a CEO. According to Jaskiewicz and Luchak (2013), more conservative family firms desire to promote their own family members to higher positions regardless of their background or previous experiences. Therefore, if they possess solid career aspiration inside the family firm, they will be considered as stronger candidates for the managerial roles than their non-family counterparts. Thus, family firms with higher conservative characteristics will tend to hire more family members for the CEO position. Nonetheless, if the family firm is more market-oriented they will consider the option of acquiring family or non-family CEOs with an adequate background and experience for the role. Hence, by possessing prior working experience candidate for the role will be better in solving problems, predicting the future, establishing goals and identifying business opportunities (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967).

21

3.

Hypotheses Development

Based on previous research, the following section will develop hypotheses regarding family firms’ CEOs experiences, as their experiences have been indicated to have a strong influence on the firm’s performance and risk-taking behaviors (Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Hambrick, 2007). Additionally, all hypotheses labeled as “B” will address the relationship between CEOs’ experiences and their risk-taking behaviors under the moderating effect of Family CEOs.

3.1. Age of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors

Likewise, as stated in the previous section, the UET indicates that older CEOs are more conservative and risk averse than their younger counterparts (Orens & Reheul, 2013; Belenzon et al., 2019). According to Bertrand and Schoar (2003), older CEOs will execute less risk-taking behaviors by adopting traditional management styles. Additionally, they also argue that older CEOs have more influence over the board of directors of a firm.

Consequently, the acquired experience, knowledge and longevity of older CEOs may influence the family firm’s board members and thus suggest less risk-taking behaviors inside the firm. On the other hand, Farag and Mallin (2018) and Graham, Harvey and Puri (2013), claim that younger CEOs have more tolerance towards risk-taking behaviors and frequently enacts growth inside the businesses. Hereby, younger CEOs tend to focus more on short-term goals in order to enhance their own reputation. Therefore, younger CEOs are more risk takers when compared to their older equivalents (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Thus, based on the literature and the UET we propose the following hypothesis regarding the effect of age and risk-taking behaviors among both family and non-family CEOs:

Hypothesis 1A: “There is a negative correlation between CEOs’ age and risk-taking

22

Moreover, when analyzing age of CEOs through the lens of the family business context, scholars focus on how the owner’s age influences the family firm performance. Owners age is negatively connected with conflict management inside the firm (Marshall et al., 2006). Therefore, as stated by Orens and Reheul (2013), elder family CEOs are expected to oppose risk in higher measures when compared to their younger counterparts. Additionally, older family CEOs are more oriented to engage short-term goals and thus, being not motivated to pursue long-term opportunities. Consequently, as CEOs begin to grow in age, they tend to be more conservative, more risk averse, less flexible and to make decisions based only on their own judgement and sources of information.

Furthermore, according to Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007) and Martino et al. (2020), older family CEOs are inclined to preserve and protect the family’s wealth, family’s reputation, family’s identity, establish more family executives inside the family firm and preserve the family’s legacy. Thus, leading them to engage in fewer risk-taking behaviors than their non-family counterparts (Huybrechts et al., 2013). Therefore, based on previous researches and the literature of the UET we propose the following hypothesis regarding the effect of age and risk-taking behaviors when integrating family CEOs into the equation:

Hypothesis 1B: “The correlation between CEOs’ age and risk-taking behaviors will

23

3.2. Tenure of CEOs & Risk-Taking Behaviors

According to Chen and Zheng (2014), high levels of tenure could foster greater managerial power of CEOs providing them with more control and consequently reducing their risk-taking behaviors. Hereby, Finkelstein (1990), argued that tenure of CEOs decreases risk-taking behaviors inside a firm. Additionally, Martino et al. (2020), explains that extended tenure of CEOs influences the initiatives of a firm. Thus, CEOs with high levels of tenure will engage in conservative behaviors by pursuing similar strategies applied in the past and thus prevailing the status quo within the firm. Moreover, according to Farag and Mallin (2018), CEOs with extended tenure are more devoted to run the firm with their own perspectives, plans and visions. Therefore, CEOs with higher tenure levels tend to be more oriented towards stability and efficiency as they have provided positive results along their career inside the firm. Also, due to their extended tenure, CEOs have served the board for a longer period of time and thus will be less oriented to engage in risk-taking behaviors in order to preserve their reputation.

By the contrary, according to Martino et al. (2020), younger CEOs with lower tenure are more open-minded to new ideas, change, experimentation and risk-taking behaviors. Moreover, according to Boling et al. (2016), in early tenure steps CEOs expose themselves to riskier activities, innovations, new strategies and risk-taking behaviors in order to build up their reputation inside the firm. Henceforth, based on the literature and the UET we propose the following hypothesis regarding the outcome between risk-taking behaviors and the tenure for both family and non-family CEOs:

Hypothesis 2A: “There is a negative correlation between CEOs’ tenure and

24

Moving on, when revising tenure in family CEOs through the lens of the family business context, scholars found that family CEOs will reduce their risk exposure and innovation efforts due to their strong desire of protecting the legacy and the financial status of the family firm (Boling et al., 2016; Martino et al., 2020). Thus, as stated above in the literature review family CEOs incline to be more risk averse for the sake and welfare of the firm to which they belong. Here, family CEOs engage in less risk-taking behaviors in order to protect the family wealth, reputation, legacy and the family name (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Martino et al., 2020).

In addition, Boling et al. (2016), mentioned in their research that the strategic actions of a firm will decrease meanwhile the tenure of the family CEOs increase. Thus, stating that as tenure increases in family CEOs they may experience higher sense of autonomy and thus, decreasing any external pressure. Hereby, as tenure increases, family CEOs tend to maintain a status quo in their operations and therefore, declining their aspiration for engaging in risk-taking behaviors. Likewise, Huybrechts et al. (2013), indicated that when the tenure of family CEOs increases over time their risk-taking behaviors decreases. Here, this behavior is associated to the desire of non-family CEOs to prevail constant over time. Hereby, based on the researches mentioned and the literature of the UET we propose the following hypothesis regarding the effect of tenure in the risk-taking behaviors of CEOs when moderating for only Family CEOs:

Hypothesis 2B: “The correlation between CEOs’ tenure and risk-taking behaviors

25

3.3. Education of CEOs & Risk-Taking-Behaviors

There is a clear link between CEOs’ education levels and risk-taking behaviors (Martino et al., 2020). Hereby, according to them, the UET indicates that educated CEOs are more resilient towards innovative ideas, changes, investment opportunities and consequently, engaging in risk-taking behaviors. Thus, Anderson, Reeb, Upadhyay and Zhao (2011), claimed that diverse academic backgrounds of CEOs may provide a firm with different perspectives, points of views, cognitive ideas and professional development. For example, Orens and Reheul (2013), stated that educated CEOs will address less risk averse behaviors becoming more openminded in their activities. After all, CEOs’ academic background will interfere with their decision making inside a business. Moreover, Farag and Mallin (2018), explained that highly educated CEOs tend to be more successful in leading companies due to their unique way of perceiving the environment.

Furthermore, Martino et al. (2020), contemplates the thought of academic backgrounds of CEOs as fundamental factors that could impact their understandings and values. Therefore, as stated before, Hambrick and Mason (1984) and Martino et al. (2020), stated that an educational background in CEOs is commonly interpreted as the trigger that leverages their cognitive skills and thus, argued that academic backgrounds promote values, knowledge, skills and cognitive decisions which influence CEOs’ risk-taking behaviors. Therefore, based on the literature and the UET we propose the following hypothesis regarding education and risk-taking behaviors for both family and non-family CEOs:

Hypothesis 3A: “There is a positive correlation between CEOs’ education and

26

Moving towards the family context, Ramón-Llorens, Garcia-Merca and Durendez (2017), argued that CEOs academic backgrounds is mostly related to the ability of internationalization of a family firm. Thus, cognitive abilities of CEOs are closely related to their educational background and will provide open minded attitudes toward new cultures, enhanced analytical skills, flexibility and adaptability. Moreover, CEOs with academic background will be much better at problem solving skills, creating social responsibility awareness and allocate more efforts and resources on opportunities Nevertheless, when understanding this phenomenon under the family business perspective. Some authors identify that regardless of their education family firms tend to develop more conservative measures when compared with their non-family counterparts and thus, hiring family members regardless of their academic achievements (Stanley, 2010; Gentry et al., 2016). However, multiple studies in the field showed that there is a positive connection between the education level of family CEOs and the firm’s performance (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Huybrechts et al., 2013). Hereafter, based on previous studies and the literature of the UET we propose the following hypothesis when addressing education and risk-taking behaviors of CEOs when moderating for non-family CEOs:

Hypothesis 3B: “The correlation between CEOs’ education and risk-taking behaviors

27

3.4. Prior Work Experiences of CEOs & Risk-Taking-Behaviors

According to Martino et al. (2020), prior work experiences of CEOs have some consequences in the firm’s decision making and its outcomes. Additionally, Anderson et al. (2011), states that prior work experiences provides CEOs with clear visions and knowledge of the firm and their corporate governance allowing them to evaluate best approaches to participate in risk-taking behaviors. Furthermore, Orens and Reheul (2013), argue that prior work experience will provide CEOs with tools to perceive the firm’s troubles, problems or dilemmas in more efficient ways.

Thus, Prior work experience will encourage CEOs to become more confident, innovative and more prepared to employ in risk-taking behaviors when compared with lesser or non-experimented CEOs (Wang et al., 2016; Farag & Mallin, 2018). Moreover, according to Wang et al. (2016), CEOs will become more secure in searching for new information, methods and strategies to make decisions as long as they grow and increase their work experience. Moreover, these experiences will enable CEOs to feel more confident to enact risk-taking behaviors during the execution of their activities. Thus, based on the UET literature we propose the following hypothesis addressing the relationship of prior work experiences and risk-taking behaviors of CEOs:

Hypothesis 4A: “There is a positive correlation between CEOs’ prior work

28

However, in the family business context the previous work experience of family CEOs might not be a crucial element to take into consideration when deciding which family member is more suitable to address the CEO position. According to Jaskiewicz and Luchak (2013), more conservative family firms desire to promote their own family members to higher positions regardless of their background or previous experiences. Here, keeping the thought of family owners being more concerned of the welfare of their descendants, as is more commonly observe that family owners desire to heir the business to the next family generation (Huybrechts et al., 2013).

Moreover, according to Martino et al. (2020), being a family member grants the individual a better chance of ascending to the CEO position. Here, due to the dominance coalition of the family firm, which in some cases is portraited by family members who belongs to the business and bear similar family values. Additionally, multiple studies suggest that family owners select their next CEO based on the idea of protecting and preserving the family’s wealth, the family’s legacy, the family’s image, the family’s identity, the family’s reputation and maintain the family control over the firm (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Huybrechts et al., 2013; Martino et al., 2020). Hence, based on previous studies and the UET literature we propose the following hypothesis concerning about the relationship of previous work experiences and risk-taking behaviors when moderating for family CEOs:

Hypothesis 4B: “The correlation between CEOs’ prior work experience and

29

4.

Research Method

The method section will cover all the steps, decisions, criteria, positions and delimitations we had during the execution of this academic paper. Thus, this section encompasses the research philosophy, the research design, description of the research variables, data analysis, research ethics and how the quality of the research was assured.

4.1. Research Philosophy & Strategy

This academic work has been developed under the ontological stance of relativism. According to Mathison (2011), relativism is a perspective without an objective reality or universal truth. Moreover, Hugly and Sayward (1987), mentions that it is of the utmost importance to distinguish between what is true or false. Thus, in order to do so it is vital to clarify the variables and its range over the study. Additionally, Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Jackson (2015), states that a relativist approach incorporates knowledge of the external world in the procedures used in the data collection. Moreover, these authors argue that there is not a universal truth or reality that can be discovered. By the contrary, there are multiple perspectives and point of views to understand and explain the truth or reality. After all, the perception of truth will differ by the context, the individuals, the place and time.

Therefore, as mentioned above in section 2.1.1, studies in family firms had been inconsistent and vary from time to time (Chua et al., 1999; Litz, 1995). Thus, a relativist ontology serves as a valuable tool to understand and explain the truth within the family business context. Furthermore, understanding how CEOs engage in risk-taking behaviors inside family firms.The family business context is so extensive and vague and thus, provides freedom to every scholar to perceive and understand in their own way the reality of family businesses. Thus, as mentioned before, thanks to the relativist ontology this thesis is able to perceive the family business context under all the knowledge previously acquired in the literature review (section 2) and thus, building new thoughts and finally, creating and/or fortifying the knowledge in the family business context.

30

Moving on, this thesis utilizes a positivist epistemology as its lens of study. According to Easterby-Smith et al. (2015), epistemology is the understanding of the essence of knowledge and shows the methods of enquiring into the social and physical worlds. In other words, as explained by these authors epistemology is “how we know what we know.” Therefore, this thesis relies on a positivist perspective to understand and explain firstly, how CEOs experiences influences their managerial risk-taking behaviors inside family businesses. Secondly, how family CEOs differs from non-family CEOs in terms of managerial risk-taking behaviors. Thus, a positivist epistemology allows to understand that the social world coexist externally and thus, it can be measured through objective methods instead of being inferred in a subjective way such as a reflection or intuition (Johnson, 2000; Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). Moreover, a positivist epistemology encompasses the following assumptions (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). First, independence which states that the researcher must be independent from what it is being studied. Second, Value freedom which means the liberty to decide a topic if study and how to study it. Third, causality which aims to identify causal explanations in human social behavior. Fourth, hypotheses and deductions both surrounds the thought of hypothesizing and then deducting what could demonstrate the truth or fallacy of the hypotheses. Fifth, operationalization, this means that concepts must be defined in order to be measured quantitatively. Sixth, reductionism, which claims that problems are better understood by reducing them into the simplest components. Seventh, generalization, for being able to move from the specific to the general it is needed to pick enough samples in order to create inferences on a much wider population. Eighth, cross sectional analysis, the components should be able to undergo a comparison of variations across samples.

Moreover, our study follows a deductive reasoning by utilizing hypotheses testing based on our theoretical framework (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). Therefore, this study covers all the assumptions of a positivist study by being independent, demonstrating causalities between CEOs’ experiences and managerial risk-taking behaviors and thus, creating the hypotheses previously stated in sections 3, defining and measuring the variables (stated in section 4.3). Moreover, reducing its analysis units to the simplest terms possible, generalizing through statistical probabilities and creating a sample of 100 family businesses across Scandinavia to undergo the study.