Master’s Degree Studies in

International and Comparative Education

—————————————————

Early Multilingualism in Sweden

A comparative case study of educators’ beliefs in three

preschools in Sweden

Ioanna Karampelia

May, 2019

Abstract

Today’s globalized world is characterized by an immense linguistic and cultural diversity and this reflects on the education. Multilingualism is a reality in the school and Sweden is one of the countries that try to promote it from the early stage of preschool. Multilingualism in the Swedish preschool mainly refers to the development of the Swedish language and the mother tongue of the student which is therefore connected with the development of cultural identity. The present study is a qualitative empirical research that aims to explore the beliefs of preschool educators (principals, teachers and childminders) on early multilingualism in Sweden through a comparative case study in two Swedish and one International preschool in Stockholm. The focus of the beliefs is on the support, views and practices on multilingualism, as well as the link between the mother tongue and the cultural identity. The study was conducted in April 2019, it includes three preschool principals, two preschool teachers and two childminders and investigates their beliefs on early multilingualism as they emerge from semi-structured interviews. The contextual background is outlined according to international, European and national documents, while the sociocultural theory is the main theoretical background that contributes to the analysis of the data. After the critical analysis of the findings, various themes and sub-themes occurred and in general, the three preschools had more similarities than differences. Overall, the preschool educators have a positive attitude towards multilingualism and try to cultivate that to the preschool children. They believe that each language expresses the culture and that multilingualism can enhance the cognitive development, linguistic and intercultural awareness. Nevertheless, support for this task is required. The study concludes with some policy recommendations and suggestions for further studies that might help to upgrade the early multilingual reality.

Keywords: early multilingualism, preschool, educators, beliefs, Sweden, sociocultural

Sammanfattning

Dagens globaliserade värld präglas av en enorm språklig och kulturell mångfald och detta reflekteras på utbildningen. Flerspråkighet är en realitet i skolan och Sverige är ett av länderna som strävar efter att främja detta, redan från förskolan. Flerspråkighet i den svenska förskolan avser främst utvecklingen av det svenska språket och modersmålet hos eleven, vilket därmed är kopplat till utvecklingen av kulturell identitet. Den nuvarande studien är en kvalitativ empirisk undersökning som syftar till att undersöka vad förskolepedagogerna (förskolechef, lärare, barnskötare) anser om tidig flerspråkighet i Sverige genom en jämförande fallstudie av två svenska och en internationell förskola i Stockholm. Fokuset av uppfattningar ligger på stöd, åsikter och praktiker på flerspråkighet, samt länken mellan modersmål och kulturellidentitet. Studien genomfördes i April 2019, den inkluderar tre förskolechefer, två förskolelärare och två barnskötare och undersöker deras uppfattningar om tidig flerspråkighet som de framgår utifrån halvstrukturerade intervjuer. Den kontextuella bakgrunden beskrivs enligt de internationella, europeiska och nationella dokument, medan den sociokulturella teorin är den huvudsakliga teoretiska bakgrunden som bidrar till analysen av data. Efter den kritiska analysen av resultaten, uppstod ett flertal teman och delteman och i allmänhet hade de tre förskolorna mer likheter än skillnader. Överlag har förskolepedagogerna en positiv inställning till flerspråkighet och försöker att kultivera det förskolebarnen. De anser att varje språk uttrycker kulturen samt att flerspråkighet kan förbättra den kognitiva utvecklingen, lingvistik och interkulturell medvetenhet. Dock är detta något som kräver stöd. Studien avslutas med några politiska rekommendationer och förslag till framtida undersökningar som kan bidra till att förbättra den tidiga flerspråkiga verkligheten.

Nyckelord: tidig flerspråkighet, förskola, pedagoger, uppfattningar, Sverige,

Acknowledgement

First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my family, Vasileios, Eleni and Christos for always being there for me. Their support encouraged me to continue my studies, apply in the ICE master programme, move to Stockholm and broaden my horizons. Their constant support, patience, help, love and faith in me inspire me to work hard and achieve my goals, so I would like to thank them for all they have done.

Furthermore, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Associate Professor of Education Ulf Fredriksson for sharing his endless knowledge and expertise with me and encourage me to work hard. His critical and fruitful comments, advice, guidance and support were a driving force while conducting this study. He helped me broaden my horizons and advance my thinking, not only during the thesis, but throughout all my journey in the International and Comparative Education master’s programme.

Moreover, I would also like to express my appreciation to all the educators who participated in that studied and allowed me to carry out that research. Each individual shared his/her personal beliefs with me and help not only to gain a better understanding on early multilingualism but also familiarize myself with a broader range of conceptions and get inspirations. Lastly, I would like to thank Robin for helping me with the translation of Swedish and for his overall support, as well as my fellow students with whom we had deep discussions, exchange of ideas and collaboratively try to find solutions and support to our challenges over the last two years.

Ioanna Karampelia, Stockholm 2019

Contents

Abstract ... i Sammanfattning ... ii Acknowledgement ... iii Contents ... iv List of abbreviations ... viList of figures ... vii

List of tables ... vii

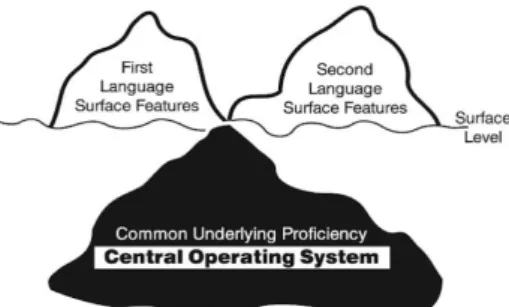

Chapter 1 ... 1

Introduction ... 1

1.1. Aim and objectives ... 4

1.2. Significance of the study ... 4

1.3. Limitations and delimitations of the study ... 5

1.4. Significance and relevance of the study to ICE ... 6

1.5. Structure of the study ... 7

Chapter 2 ... 8

Contextual background of the study ... 8

2.1. International agreements influencing multilingualism in ECEC ... 8

2.2. European documents on multilingualism in ECEC ... 10

2.3. National steering documents for preschool ... 12

2.4. Swedish education system ... 15

2.5. ECEC system in Sweden ... 16

2.6. Language situation in Sweden ... 18

Chapter 3 ... 21

Theoretical Framework ... 21

3.1. Key concepts ... 21

3.1.1. Multilingualism ... 21

3.1.2. Mother tongue ... 22

3.1.3. Common Underlying Proficiency ... 22

3.1.4. Beliefs ... 23

3.2. Sociocultural theory ... 24

3.3. Translanguaging ... 26

3.4. Previous research ... 26

Chapter 4 ... 28

Methodology of the study ... 28

4.1. Research strategy ... 28

4.2. Research design ... 29

4.3. Research method ... 30

v

4.3.2. Sampling design, strategy, selection process and participants ... 31

4.3.3. Analytical framework ... 32 4.4. Quality criteria ... 33 4.4.1. Trustworthiness ... 34 4.4.2. Authenticity ... 34 4.4.3. Generalization ... 35 4.5. Ethical considerations ... 35 Chapter 5 ... 37 Findings ... 37 5.1. Preschool A ... 37

5.1.1. Municipal guidelines on early multilingualism ... 37

5.1.2. Preschool’s contextual profile ... 38

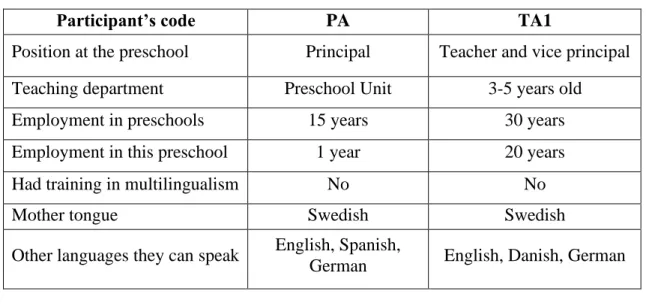

5.1.3. Participant’s profile ... 38

5.1.4. Interview findings ... 39

5.2. Preschool B ... 43

5.2.1. Municipal guidelines on early multilingualism ... 43

5.2.2. Preschool’s contextual profile ... 44

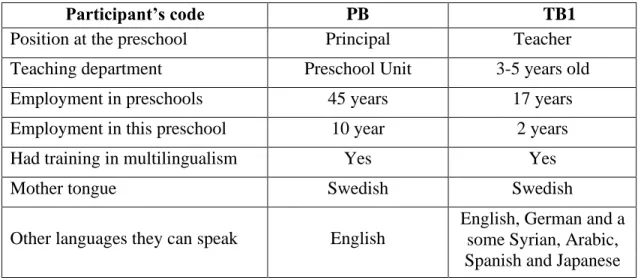

5.2.3. Participant’s profile ... 44

5.2.4. Interview findings ... 45

5.3. Preschool C ... 49

5.3.1. Municipal guidelines on early multilingualism ... 50

5.3.2. Preschool’s contextual profile ... 50

5.3.3. Participant’s profile ... 50

5.3.4. Interview findings ... 51

5.4. Answering the research questions ... 56

Chapter 6 ... 63

Discussion ... 63

Chapter 7 ... 69

Conclusion and suggestions for further research ... 69

References ... 70

Appendices ... 81

Appendix A Interview Guide – Principals ... 81

Appendix B Interview guide – Teachers & Childminders ... 83

Appendix C Participation information sheet ... 85

Appendix D University’s Reference ... 87

Appendix E Interviewee’s consent form ... 88

List of abbreviations

CUP – Common Underlying Proficiency EC – European Commission

ECEC – Early Childhood Education and Care EFA – Education For All

EU – European Union

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

GDPR – General Data Protection Regulation IBID – Ibīdem (in the same place)

ICE – International and Comparative Education ICT – Information and Communications Technology L1 – Language one (mother tongue)

LPFÖ - Läroplan för Förskola MTT – Mother Tongue Tutor

OECD - Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development SDG – Sustainable Development Goal

UN – United Nations

UNESCO - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization ZPD – Zone of Proximal Development

List of figures

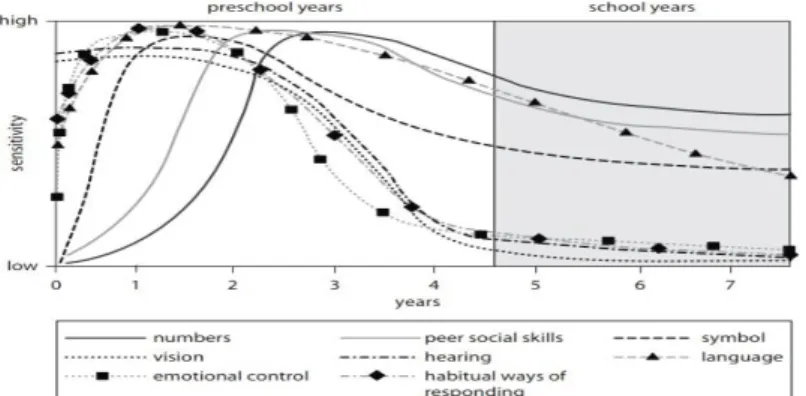

Figure 1. Sensitive Periods in Early Brain Development ... 2

Figure 2: Sustainable Development Goals by UN ... 9

Figure 3: Areas of learning and development in educational guidelines in ECEC in Europe ... 11

Figure 4: Common Underlying Proficiency Model ... 23

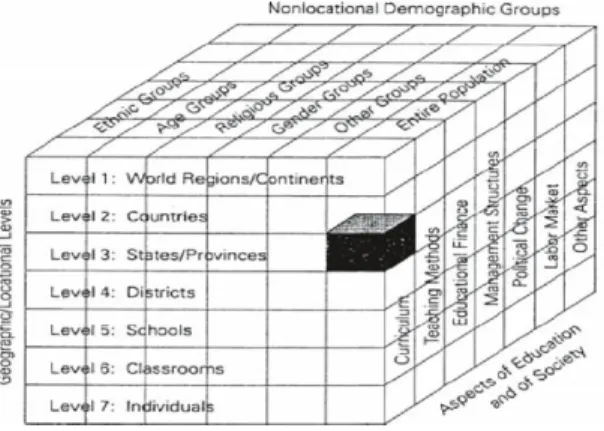

Figure 5: A Framework for Comparative Education Analysis ... 29

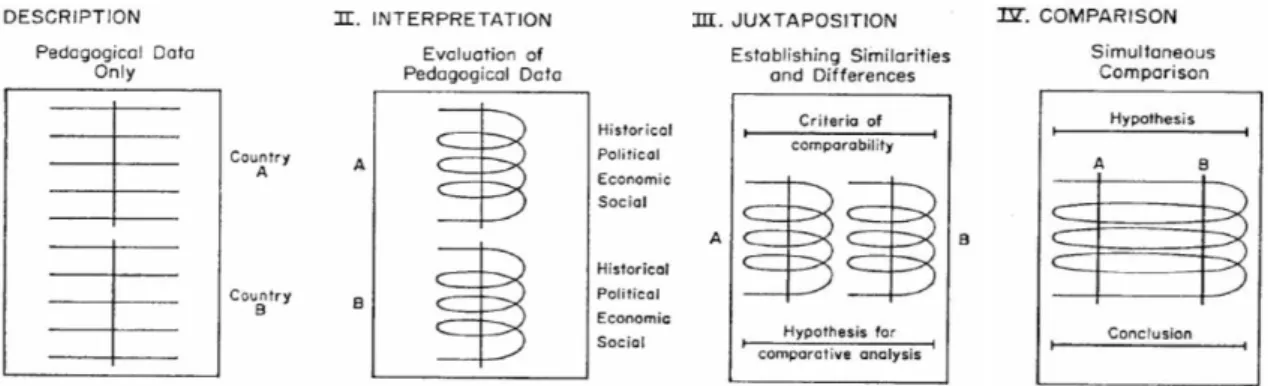

Figure 6: Bereday’ s Model for Undertaking Comparative Research... 33

List of tables

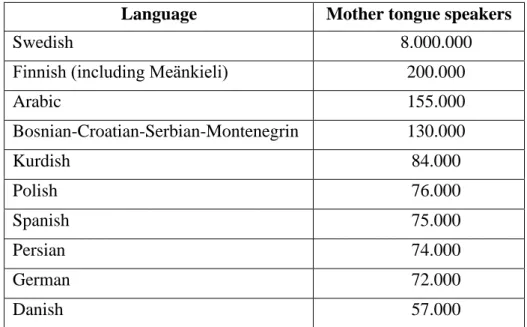

Table 1: Significant EU publications that promote multilingualism from a very young age ... 11Table 2: The ten most spoken languages in Sweden in 2012 ... 19

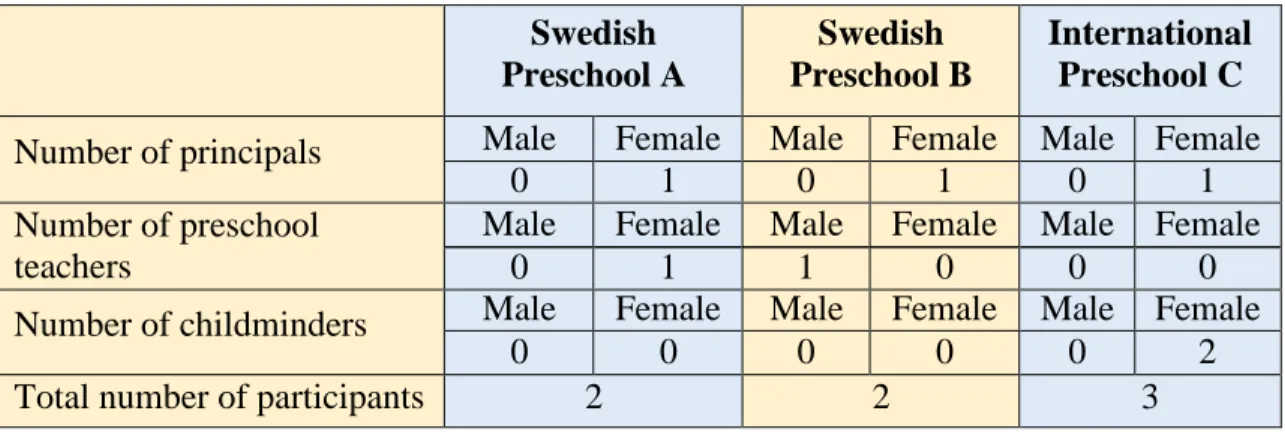

Table 3: Number of participants per preschool ... 32

Table 4: Participants' profile in Preschool A ... 39

Table 5: Themes and sub-themes in Preschool A’s interviews ... 39

Table 6: Participants’ profile in Preschool B ... 45

Table 7: Themes and sub-themes in preschool B’s interviews ...45

Table 8: Participants' profile in Preschool C ... 51

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

With the rapid growth of technology and the revolution in the means of transportation, we can say that, nowadays, we truly live in a global society. Globalisation has given the opportunity to people from all around the world to travel, settle down and get employed unconstrained by national borders. Indeed, mobility plays a vital role in shaping societies. Today’s communities are characterized by an immense migration flow due to economic, social or political reasons. Furthermore, people can have digital access to information, communication and entertainment from all around the world thanks to the Information and Communications Technology (ICT). One of the emerging needs of global societies, which all the 21st century citizens strive for, is being capable of learning and mastering at least one language outside of the mother tongue (Pan, 2015). So, having the ability to speak many languages seems to be an important facet of the global world.

Being knowledgeable in different languages can provide people with new opportunities. It provides a unique opportunity to open up to new cultures and experiences that they would otherwise not have access to. According to Baker and Wright (2017), the purpose of learning foreign languages can be “societal and

individual” (p. 110). To clarify, societal reasons of learning a new language include the

assimilation of minority groups, immigrants and migrants to the host nation, to cultivate social cohesion, intercultural understanding and peace, as well as economic reasons like trade across the borders and tourism. Individual reasons of learning foreign languages include gaining increased cultural awareness for other cultures, broadening their horizons, strengthening one’s career and employment opportunities and growing their socioemotional, moral and ethical development. Overall, being able to speak two or more languages, be multilingual as to say, can give a wider access to cognitive, social, emotional, cultural, professional and economic development.

Apart from the societal and individual reasons to learn a new language, it should be noted that linguistic diversity is a societal norm and is usually caused in two ways: Because of high mobility and migration levels due to globalization and Europeanization, or because of minority communities that have a long tradition and history in using and preserving their own minority language (Marácz & Adamo, 2017). Having said this, it is obvious that multilingualism is present in all societies, so it must have a prominent place in education systems. Education systems need to take into account the role of multilingualism as an important determining factor of the success of the society and help to prepare future citizens that are equipped with all the necessary knowledge and values to meet the demands of the globalized world.

One of the education systems that tries to promote multilingualism at a very early stage is the Swedish. To begin with, multilingualism is addressed in the preschool curriculum. According to that, the children are expected to develop their multilingual

2

skills from a young age, which happens to be a very crucial age for their language development skills in the future. When the Swedish National Agency for Education, or simply known as Skolverket, refers to multilingualism in the preschool, it mainly refers to the mother tongue-based multilingualism. Mother tongue-based multilingualism means that the preschool should provide the right support to the children in order to develop both their mother tongue and the Swedish language, and gain multilingual competence (Skolverket, 2019a). As it is stated in the preschool curriculum:

“Children with a foreign background who develop their mother tongue create better opportunities for learning Swedish, and developing their knowledge in other areas. The Education Act stipulates that the preschool should help to ensure that children with a mother tongue other than Swedish, receive the opportunity to develop both their Swedish language and their mother tongue”

(Skolverket, 2016, p. 7)1.

Education and learning are lifelong processes beginning from a very early age and lasting well beyond after the schooling years are over. Most children in Sweden usually spend the first year of their life at home and then many spend several years in an Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) setting. These years are the most substantial years for learning during childhood (Brodin & Renblad, 2014). There is this stage of life that lasts from infancy to puberty and it is named as critical or sensitive period (Finn, 2010; Robson, 2002). During this period, children are in a stage that their brain develops and neurons are hypersensitive to stimulations. It is no surprise then, that this is the most crucial time for language development and language acquisition (figure 1), so investing in language teaching in these ages is of high importance. All the stimulation that children get during this period will be crucial when forming their language skills in the future.

Figure 1. Sensitive Periods in Early Brain Development (retrieved from Elder, Kataoka, Naudeau, Neuman, & Valerio, 2011, p.39).

1 Author’s translation of “Barn med utländsk bakgrund som utvecklar sitt modersmål får bättre möjligheter att lära sig svenska och även utveckla kunskaper inom andra områden. Av skollagen framgår att förskolan ska medverka till att barn med annat modersmål än svenska får möjlighet att utveckla både det svenska språket och sitt modersmål”.

3

During this critical period of time, socioeconomic factors like children coming from a migration background or a low-income family can affect the stimulations that these children get. That makes it even more important, for these children, to attend a high-quality preschool that can assist them in order to develop their intellectual, cognitive and language skills (Vermeer, van Ijzendoorn, Cárcamo & Harrison, 2016; OECD, 2015; Sheridan, 2007). One way of doing so is by providing support to the children’s mother tongue and encourage them to express their identity. According to Sheridan (2007), children’s learning outcomes and self-esteem can benefit by a high- quality preschool. To expand on it, research conducted by Brodin, Hollerer, Renblad and Stancheva-Popkostadinova (2015), showed that one of the most important dimensions of high-quality preschool education were the teachers’ perspectives.

Taking into account the importance of multilingual education, this study will attempt to critically investigate the beliefs of preschool educators on early multilingualism in Sweden. For this purpose, an empirical study will be conducted using interviews of preschool educators (principals, teachers and childminders) about their beliefs on multilingualism, in order to gain a deep understanding on how do these educators view multilingualism and which practices do they follow in the preschool. The study is a comparative case study that explores the beliefs of preschool educators (principals, teachers and childminders) on early multilingualism in two Swedish and one International preschool in Sweden. The research focuses on the beliefs and practices of educators.

The reason for this comparison derives from the fact that while all preschools follow the national curriculum, they have a different dynamic in their students’ population and they both have to adapt on that by offering mother tongue opportunities. An International school is expected to have a big cultural diversity of students with parents who move a lot due to their job (foreign background). So, probably an international school needs to work very intense with the multilingualism and deal with many different mother tongues at the same time as Swedish students are usually a minority there. However, most of the Swedish preschools are usually expected to have a bigger number of Swedish students and a smaller number of students with a foreign background, with exceptions occurring in some areas. Since the immigration levels are high, a cultural diversity will exist but it is more possible that the children with a foreign background will be in smaller numbers than Swedish. Since the vast majority of the preschools in Sweden are Swedish, the author wanted to include more than one Swedish preschool in order to make the study more representative, while she still found it is of the outmost important to include the international preschool in order to compare different environments. With that being said, it would be interesting to see how two different types of preschools that follow the same guidelines but have different group dynamics regard multilingualism in the preschool.

4

1.1.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the study is to explore the beliefs of preschool educators (principals, teachers and childminders) on early multilingualism in Sweden through a comparative case study in two Swedish and one International preschool in Sweden. The research focuses on the beliefs and practices of educators on early multilingualism and the research questions that will guide the study are:

1. How do preschool educators understand and view multilingualism?

2. What kind of support do the educators need in order to support the multilingual reality of the preschool?

3. How do the preschool educators work in order to promote multilingual development?

4. Which are the beliefs of the preschool educators regarding the link of the mother tongue with the cultural identity and with the holistic development of the children?

5. Which similarities and differences can be found in the beliefs of the educators in the three preschools?

1.2.

Significance of the study

Sweden is a country with an ethnical and cultural diversity. This heterogeneity is expressed in many ways, among which includes the language. The majority of the children speaks the Swedish language, while there is a large number of children who speak a minority language or another language than Swedish. It is remarkable that 35,4% of the children under 4-years-old had a foreign background with at least one non- Swedish parent (Statistics Sweden, 2016 as cited in Schreyer & Oberhuemer, 2017). In some cases, the immigrant students can even be above 50% in a school (Cerna, Andersson, Bannon, & Borgonovi, 2019). The role of the preschool is to foster equal opportunities for access, learning and development to all children and give them the essential support. Taking into consideration the needs of each individual child is identified as the key to equal opportunities and high-quality education both in international documents and in the Swedish preschool curriculum, so offering all mother tongues should be indispensable.

This research can accentuate the beliefs of the educators and the classroom reality through the practices of the educators on multilingualism in preschool. The concepts of communication and language are highly present in the preschool curriculum (Skolverket, 2016). The interviews might reveal a deep understanding or hidden aspects on early multilingualism that can bring a new perspective and input on the ongoing political and educational discussions about the significance and reality of multilingualism and mother tongues in the preschool. The findings of the study are to hopefully contribute on forming a better understanding of the educational reality on multilingualism in preschools in Sweden.

5

Indeed, one of the most understudied topics on ECEC research is teachers. Brodin et al. (2015) emphasize that only a limited number of studies include ECEC teachers. This seems quite problematic because teachers are the fundamental stakeholders and their beliefs reveal their views, values, commitment and practices. “Teachers are the

major players in the education process” (Hattie, 2012, p. 28), they are the ones who can

create an impact and bring a change. Teachers are the main mediators that implement the curriculum and the policies through their practice. Specifically, teachers’ beliefs reflect the teacher’s role to fulfill the national/local goals, the students’ potential, the practices followed in the learning process and the purpose of school in society. Conducting a research that takes into consideration the beliefs of educators in ECEC is really decisive. The intention to investigate the beliefs derive from Pajares (1992) who identified beliefs as “the single most important construct in educational research” (p. 329).

An exploration on educators’ beliefs and practices can indicate how multilingualism could be regarded and implemented in the Swedish context. In this respect, the study could be seen as a structured attempt that explores how multilingualism is conceptualized and implemented in different preschool contexts. The research sets the grounds for further studies on the importance of languages as an excellent foundation in preschool and possibly give points to ponder to education planners when sketch out reforms.

1.3.

Limitations and delimitations of the study

Every research is subjected to some restraints. This study is a master thesis written within the International and Comparative Education (ICE) framework of the master programme at the Department of Education in Stockholm University. This brings in some limitation in the research which need to be acknowledged, but they cannot always get overcome because they can affect the feasibility of the task. Since this is a master thesis study, the analysis of the topic can go deep but it cannot be exhaustive. In addition, there is a limited time frame that is quite short and this means that it is impossible to conduct a qualitative study with a big sample size. The amount of time needed to conduct the interviews, transcribe them and do the analysis is very time- consuming and leads to having smaller sample than desired. Also, many preschools wanted a notice of 5-6 months in advance before the research and that was not feasible. Moreover, the initial intention was to include some observations, but the idea was rejected since observations require a lot of time and also the preschool requires a lot of time until they get the consent forms from all the parents.

Language can also be a limitation when it comes to interviews and the researcher does not speak fluently the language of the country (Phillips and Schweisfurth, 2014). The interviews were conducted in English because the researcher has an intermediate level of Swedish but she cannot speak Swedish with proficiency. Most of the preschools that were invited to participate rejected the invitations because the staff does not speak English confidently. However, neither the researcher nor the final interviewees are native speakers in English and this could lead to misunderstandings or bring challenges

6

to express themselves clearly. In order to overcome the language obstacle two steps were taken: firstly, the participants were meticulously informed about the topics of the interview by getting the questions beforehand so they have time to think and construct their speech in English, as well as they were provided with explanation in Swedish when it was necessary. Secondly, in case of difficulties in expressing, Swedish speakers had the opportunity to switch to Swedish for clarifying themselves and the translation was double-checked later. Language can also be a restraint when it comes to documents that are only available in Swedish. For that reason, a native Swedish speaker was assisting the translation in order to avoid misunderstandings. Translating a document might sometimes mean that some important meanings can be lost on the way or get misinterpreted. This can happen not only when the researcher translates the Swedish text herself and with a native speaker’s support, but even when an official translation is provided.

The last limitation of this study revolves around the nature of the qualitative research. Qualitative studies are often criticized because they are accused of lacking replicability, objectivity and generalization (Bryman, 2016). Due to the narrow sample size, it cannot be guaranteed that the educators’ beliefs are representative for all the educators in the respective country. But the sample is not meant to be representative as it contains personal beliefs anyway. Contrariwise, the focus is on getting a deep understanding on beliefs rather than drawing general conclusions.

1.4.

Significance and relevance of the study to ICE

The study is of high relevance to International and Comparative Education. To begin with, multilingualism can be seen as an international topic itself. It is promoted by international institutions and the EU in order to create a more competent society that will contribute to economical and societal development. It gives access to international information, knowledge, skills and perspectives (Baker & Wright, 2017). Multilingualism is also a part of daily life globally due to the high migration levels and the diverse cultural composition of today’s society.

Nowadays, nations are not characterized by homogeneity but they are comprised by multiethnic and multicultural groups (Marshall, 2014). This means that multiculturalism is an everyday normality in the society and as a consequence in the preschool too. Multilingualism in Swedish preschool is seen through the engagement and teaching of students’ mother tongues from all around the world in order to cover all the needs and promote an international mindedness. Multilingualism in preschool can spark the interest for foreign language learning, promote curiosity, broaden horizons towards other cultures, cultivate empathy and develop individuals and societies (Golis, 2016). This exactly how Martínez de Morentin (2004) define international education, as “education for international understanding” (p. 5), which means that the education revolves around and fights for peace, human rights, diversity, respect for other cultures and the different. Marshall's (2014) definition adds among others the education for international mindedness, for international schools, for minorities and indigenous people

7

and education in a diverse group of individuals. All of these aspects are included to some extend in the current study.

As far as the comparative element is concerned, Brodin et al. (2015) highlight that there is a conspicuous demand for comparative studies in the field of ECEC, so as to enhance and develop learning and knowledge in the international society. Blaiklock (2010, as cited in Brodin & Renblad, 2014) also underlines that comparative studies can contribute to future knowledge in academia and offer solution to many problems. Comparative studies do not necessarily have to deal with comparisons between nations but they can also deal with intra-national comparisons (Marshall, 2014), such as comparing units or individuals. According to Manzon (2014), place comparisons in the level of schools within a nation will contribute to a better understanding of the educational reality, and at the same time in an individual level through the beliefs of educators. Comparison studies underline that it is crucial in social research to seek for a variety of information through accumulating and comparing interpretations of personal beliefs (Potts, 2014). So, being aware of educators’ beliefs can contribute to the current debate agenda and give food for thought to future reforms.

1.5.

Structure of the study

The study is structured in seven coherent chapters that tackle to capture the issue of multilingualism in preschool as clearly as possible and how this is regarded by the various educators. Chapter one is an introductory chapter to the study which introduces the subject of the research as well as the aim of the study. This chapter also contains the significance and limitation of the study and its relevance to the field of ICE. Chapter two introduces the contextual background of the research by presenting the key international, European and national documents that are relevant to multilingualism in ECEC and it continuous with the Swedish education system and the language situation in Sweden. Chapter three includes the theoretical framework of the study by presenting the key concepts of the study, the sociocultural theory, translanguaging and some previous research on the topic, while chapter four describes the methodological framework of the study. Chapter five demonstrates the findings of the study and the similarities and differences in the three preschools. Lastly, chapter six presents a discussion of the findings and provides some policy recommendations and in chapter seven the final conclusions are made and suggestions for future research are given.

8

Chapter 2

Contextual background of the study

This chapter depicts the background of the study with all the contextual information around multilingualism in preschools in Sweden. The chapter will present some international agreements, some European and some national documents about multilingualism in ECEC which are of high relevance to the research. In order to gain a better understanding of how do these documents imply in Sweden, an overview of the Swedish education system and the language situation of the country will be explored too.

2.1. International agreements influencing multilingualism in ECEC

The international document with the greatest probably influence on multilingualism in ECEC is the “Convention on the Rights of the Child” (United Nations General Assembly, 1990). In 1990, the United Nations General Assembly introduced the Convention which was ratified by almost all the countries. This document was a promise to keep children protected and give them freedom. Of course, the language was a fundamental issue that got addressed there. Article 29c refers to:

“The development of respect for the child's parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civilizations different from his or her own” (United Nations General Assembly,

1990, p. 9).

One way of respecting every child’s linguistic and cultural identity is by actively including it into the everyday life and not by discriminating it. Mother tongue-based multilingualism includes all the different languages that exist in the preschool, while keeping the language of instruction. At the same time, the individual gets the respect he/she deserves for his/her cultural identity and the rest get exposed to a diversity that can transform the way they see the different and increase their international mindedness, openness, intercultural understanding and promote equality and freedom. Article 30 continues about language but this time the minorities are on the spotlight:

“In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture, to profess and practice his or her own religion, or to use his or her own language” (United Nations General

Assembly, 1990, p. 9).

This was a keystone for the minorities that were oppressed for years, but they could now use their own language to communicate and follow their own culture. This implies

9

that all minority children should have the opportunity to use their mother tongue from the beginning of preschool.

Influence on multilingualism in ECEC probably comes from an international agenda too, the Sustainable Development Goals. The United Nations (UN) brought up the SDGs agenda (figure 2) in September 2015, but the action towards them began on the first of January 2016 (United Nations, 2015b). The deadline for completing the agenda is on 2030. The SDG 4 is generally revolving around education and it is to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning

opportunities for all” (United Nations, 2015a). This means that the education system

should take into account and counter the multilingual ordinary of the society and provide equal opportunities to the students. By offering a mother tongue-based multilingual education, all the children will be able to learn based on their needs, lives and by using their own language, so the education will be both inclusive and equal (Wisbey, 2016).

Notably, the target 4.2 is “by 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to

quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education” (United Nations, 2015a). Gracefully, it is the second time,

after the Dakar framework for Action in 2000 with the Education For Alla (EFA), that an international agenda includes reference to ECEC. Wisbey (2016) supports that offering teaching in mother tongue’s is one way to achieve high-quality ECEC because children tend to learn better when they learn in a language that they already speak, their mother tongue. The Swedish preschool curriculum does recognize that too and supports mother tongue-based multilingual education.

4.7:

Figure 2: Sustainable Development Goals by UN, (United Nations, 2015b).

The other target in SDG 4 that is related to multilingualism in preschool is target

“By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others…human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (United Nations, 2015a).

10

This target stresses more the human rights, one of which is the linguistic right and having the freedom to use the mother tongue in order to expose people to cultural diversity. All the different cultures should be respected and this ordinary diversity of the society is seen as something that can positively contribute to sustainable development. In the Swedish preschool curriculum, the mother tongue-based multilingual education is connected with the cultural identity and respect to other cultures.

2.2.

European documents on multilingualism in ECEC

There are many more documents that have influenced the early multilingual education in Sweden. Most of them come from the European Union. Since Sweden is a member in the EU, it is recommended -however not obliged- to follow the policies and guidelines suggested by the EU. EU is constantly trying to encourage foreign language learning of at least two foreign languages in addition to the mother tongue since 2002 (European Commission, 2002), in order to create a highly-competent European population, strengthen its market, increase the mobility and the intercultural understanding (European Commission, 2012). The reasons that lead the EU to these policies for multilingualism are to create competitive EU citizens, opportunities for young people to work and study abroad, to make travel and trade easier and create new business markets in EU that will be globally antagonistic, to harmonize the co-existence of the different languages, to lay the foundations for an inclusive society with intercultural understanding, tolerance, respect among different groups and finally to cultivate a sense of EU citizenship (European Commission, 2018a, European Commission, 2012).

A cornerstone for linguistic diversity in schools is the “Charter of Fundamental

Rights” of the European Union (European Parliament, European Council, & European

Commission, 2000). The article 21 is against the discrimination based on many characteristics, one of which is also the language. The article 22 declares that there should be respect for the linguistic, cultural and religious diversity. According to the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the education should respect the needs, the culture, the values and the language of each child even if these children come from another country.

In the Barcelona European Council in 2002, with the “Presidency Conclusions” the European Commission (EC) noted the further action is need for improving foreign language learning from a young age. The EC started to accentuate the importance of teaching in at least two foreign languages from a very early age (European Commission, 2002). This goal was agreed by EU Heads of State and Government in March 2002 in Barcelona and had a dual target: first to increase the human capital in EU and second to enhance the linguistic and cultural diversity. After that, and until today, the EU has come up with many action plans, strategies, frameworks and policies that support multilingual education (mother tongue plus one or two foreign languages) from a young age. Table 1 summarizes all the significant publications of the EU that aim attention to foreign language learning from a very early age.

11

Table 1: Significant EU publications that promote multilingualism from a very young age.

Name of the document Author and year of publication

Charter of Fundamental Rights

European Parliament, European Council, European Commission, 2000

Presidency Conclusions European Commission, 2002 Action plan for “Promoting Language Learning

and Linguistic Diversity” European Commission, 2003 Framework of multilingualism European Commission, 2005 The strategic framework for European

cooperation in education and training (ET 2020)

Official Journal of the European Union, 2009

European Strategic Framework for Education and Training (ET 2020): Language learning at pre-primary level: making it efficient and sustainable - A policy handbook

European Commission, 2011

Eurydice Policy Brief: Early Childhood

Education and Care European Commission, 2014a

Conclusions on multilingualism and the development of language competences

Council of the European Union, 2014

Council Recommendation on High Quality Early

Childhood Education and Care Systems European Commission, 2018a Structural Indicators for Monitoring Education

and Training Systems in Europe - 2018

European Commission, EACEA, & Eurydice, 2018

What is noteworthy is in the policy report that the European Commission (2014a) conducted in 2014, is that only a few EU countries have early foreign language guidelines and these guidelines usually applied only for the older children that attend ECEC programmes (figure 3).

Figure 3: Areas of learning and development in educational guidelines in ECEC in Europe (European Commission, 2014a, p.21).

12

All things considered, the EU documents above (table 1) underline the significance of early language learning and multilingualism. Exposing children to foreign languages from a very young age can set out the foundations for enhancing mother tongue skills, faster language learning, excelling performance in other subjects too and generate positive attitudes towards different cultures and languages. The above strengthen the vision of EU, which is to create a unity in the diversity where many languages can peacefully co-exist and give the possibility to people to become more employable, antagonistic, connect, travel, meet other cultures and develop an understanding for each other (Bonjean, 2018).

2.3.

National steering documents for preschool

When it comes to the leading documents of preschool education in Sweden, two are the core documents to look for: The Education Act1 (2010: 800) and the national curriculum for the preschool2 (Lpfö98). These two documents provide the provision and the framework in which preschool education should stand, set the standards and goals, ensure quality and define the responsibilities.

In the first place, the Swedish parliament decided on a new law, the Swedish Education Act (2010:800) (Ministry of Education, 2010) in June 2010, but its application begun since the first of July 2011 (Doe, 2017c). The Education Act states the fundamental regulations for the preschool (förskola), preschool class (förskoleklass), compulsory education (grades 1-9) (grundskola), high school (gymnasieskola), municipal adult education (kommunal vuxenutbildning), Swedish courses for immigrants (SFI), the Sami school, the leisure-time center (fritidshemmet) and for students with learning disabilities.

According to Chapter 1, paragraph 11 (Ministry of Education, 2010), the government or the authority that the government runs decides on the curricula that should apply in all school forms. The curricula should be designed according to the provisions of the Education Act and they must state the goals, the guidelines, the values and the tasks of the education in each school form. As stated in the Education Act (Ministry of Education, 2010), the main aim of education is to advance children’s development and learning through acquiring both values and knowledge, as well as to trigger their longing for lifelong learning. The education is offered in a safe environment with a democratic and human rights approach and should be equal and regardless their abilities or background. All the children should be protected against any kind of offence by the Discrimination Act3.

The Education Act shows a serious consideration about languages in preschool. For the children who belong in a national minority group, their parents can apply to the

1 Skollagen (2010: 800)

2 Läroplan för förskolan Lpfö 98 3 Diskrimineringslagen

13

municipality for attending a preschool where the language of instruction is exclusively or partially in the minority languages. Furthermore, the children who have another mother tongue than Swedish but they do not belong in a national minority should develop both their mother tongue and the Swedish language (Chapter 8, paragraph 10).

The Education Act (2010:800) mentions the main institutions and individuals who are responsible for preschool education: the municipality, the school principal (Skolchef) and lastly, the preschool teachers that are responsible for teaching. The municipality should offer a place to children from 1-year-old according to their parents’ employment/studies or family status. By the time the children turn 3-years-old, the municipality should offer a spot to a preschool for at least 525 hours a year.

The second crucial document that needs to be examined is the national curriculum for the preschool. In 1998 Sweden established its first National Curriculum for Preschool (Lpfö 98) and started to set aims and values with the attention been drawn on care, play and learning (Brodin & Renblad, 2014). The Lpfö 98 has been revised during the years. Currently, the “Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö 98 - Revised 2016”1 (Skolverket, 2016) is in force. However, Skolverket (2018) has already established a new curriculum, the Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö 182 which will come into force on the first of July 2019. Since the present research is conducted during the Lpfö 98 is on force, this is the one to use as a reference point. Nevertheless, the main relevant changes that have been introduced to the new curriculum will be examined in order to get an updated and wider perspective on what Sweden is trying to achieve in the preschools.

The curriculum consists of the “fundamental values and tasks of the preschool” 3 and the “goals and guidelines”4 (Skolverket, 2016, p. 3). The cornerstones in the fundamental values of preschool are the same as in the Swedish society and they are not others than democracy and human rights. Children should develop the values of responsibility, respect, equality, positively non-discrimination and positively encounter of differences (on gender, ethnicity, culture, language, religion, sex etc.), freedom of expression, openness, justice, empathy, culture and ethics.

The “tasks” of the preschool (Skolverket, 2016, pp. 5–7) are to set the bases for lifelong learning and strive for boosting development, learning, knowledge, values, social skills and lust for lifelong learning in an appropriate, stimulating and secure environment and through pedagogical activities that are in pace of the children’s interests. Preschools should also provide support to parents on how to raise their child at home and prepare the children for the international community in which they live in. Creating experiences, giving opportunities for conscious play and providing the space

1 Läroplan för förskolan Lpfö 98 Reviderad 2016 2 Läroplan för förskolan Lpfö 18

3 Author’s translation of “förskolans värdegrund och uppdrag” 4 Author’s translation of “mål och riktlinjer”

14

for child to child interaction are important task of the preschool too. Furthermore, one of the tasks of that the preschool has is to stimulate each child’s language development both in oral and written form because learning is inseparably linked with the language and cultural identity development. Foreign children should develop their mother tongue and the Swedish language and since language and cultural identity are inextricably linked, the children with a foreign background and those from a national minority groups should get support in developing a “multicultural sense of identity”1 (Skolverket, 2016, p. 6). The children should have the opportunity to develop their language skills, strengthen their cultural identity, learn to be caring with the environment, use their imagination and use also different ways of expression (play, art, drama etc.). On the whole, the preschool’s task is to provide cognitive, emotional, social, linguistic, physical and psychical development to the children.

The goal section designates the direction that the preschool should work on and the quality development awaited from the preschool, while the guidelines define the responsibilities that all the staff in the preschool has individually and as a team in order to ensure that the goals, the “values and the task” of the preschool are accomplished (Skolverket, 2016, p. 8-16). According to the goals and guidelines, the preschool should teach about norms and values based on democracy like it was mentioned above (ibid). As far as the development and learning are concerned, the preschool should adopt a pedagogical approach with activities which give space to the children to learn together and socialize. The goals on this section are plenty and they revolve around the notion that the preschool should provoke children’s learning and development through a challenging and motivating environment that lets play, curiosity, imagination, creativity and experiences to arouse. The preschool should “develop the child’s identity and make

him/her feel secure in it”2 (Skolverket, 2016, p. 9), while in the meantime they should also learn Swedish.

The curriculum also refers to the relations with the home (Skolverket, 2016). Preschool and family should work close together. The parents are responsible for their child upbringing and can influence education in the preschool within the framework of the curriculum, but the preschool functions additive. The staff should co-operate with the preschool class that will receive the child, so that the transition will be easier.

The responsibility of the principal is to monitor the quality of the preschool by conducting systematic quality work in co-operation with the preschool teachers; childminders and other staff or even parents, to make sure that the preschool functions according to the goals, norms, values and guidelines of the curriculum and the other relevant documents are followed; to create an appropriate material and non-material environment in the preschool; communicate with home and the preschool staff; organize staff training to increase their competence (Skolverket, 2016).

1 Author’s translation of “en flerkulturell tillhörighet”

15

To conclude with, according to the Swedish preschool curriculum, the preschool should promote a variety of learning opportunities through child to child and teacher to child interactions which are based on children’s interest and their previous experiences. The interactions are seen as the cornerstone of pedagogical quality because they help children to develop and learn (Sheridan, 2009). The quality should be driven by the curriculum goals and should be documented. Someone can figure out from all the above that Sweden endeavors to providing high quality preschool education, encompasses a strong environmental, sociocultural and learning aspect of education and finally, empowers democracy, equity and responsibility.

The new curriculum is quite similar but it introduces some new aspects (Skolverket, 2018b). Skolverket has customized it to the current Swedish reality and incorporate all the international trends and demands, like sustainable development, to an updated guide for the preschool. The changes reflect the need of education to keep up to date, improve and increase the quality. In brief, the changes that can be seen as relevant to multilingualism are (Skolverket, 2019d):

•The influence from the Convention on the rights of the children is stronger • Children from national minorities have the right to get support in their mother tongue and develop their cultural identity

•The Swedish sign language should be available for deaf/hearing loss children •Provide strong stimulation and support based on the child's needs and conditions •The term of sustainable development is introduced

For the section of language, the new curriculum highlights a lot more that the preschool should promote an understanding for the different languages and cultures, including the national minority children and their right to develop their language and cultural identity, as well as the Swedish language. The national minority languages should be actively protected and promoted by the preschool. The different cultures and languages should be evident and advocated. Lastly, support in the Swedish sign language should be provided to deaf children or children who require it.

Altogether, the Swedish curriculum comes in a line with the European Commission's provision of ECEC that should have a holistic approach and revolve around the child’s needs for having a proper development, learning and well-being. The learning needs of the children should cherish their “social, emotional, physical,

linguistic and cognitive development” (European Commission, 2014b, p. 66).

2.4.

Swedish education system

Learning about the Swedish education system can contribute to a better understanding on how education functions and how much of an importance it has in the respective country. To begin with, the ministry that is responsible for education, research and youth policy is the Ministry of Education and Research. This ministry is responsible for funding in education, achievement in school and conditions that teachers

16

face (Regeringen & Regeringskansliet, 2014). The Ministry of Education and Research is also in charge of controlling some government agencies, one of which is Skolverket.

Skolverket is the main administrative authority for the public preschools, schools, school-age childcare and adult education and its role is to ensure that all children and students have equal access to high-quality education in safe environments (Skolverket, 2019f). It is culpable of publishing the national curricula, guaranteeing that the national goals are completed, developing preschools, schools, knowledge, allocating state funds, providing teacher’s certifications and in-service training and programmes for teachers and head masters.(Skolverket, n.d.).

Since the Swedish education system is decentralized, there are many responsibilities handled by the municipalities (kommuner) and the municipal council in all school levels (Doe, 2017b). The municipalities follow the national policies and frameworks but they also have an immense autonomy so they can decide on matters from funding to quality checks. In a school level, preschools have a preschool principal (förskolechef) and schools have a school head (rector) who carry out administrative work about the school, the staff and the education activities (Doe, 2017a).

In Sweden there are two types of schools: public (kommunal) and independent (fristående). The independent preschools and schools can be run by a company, parental cooperation, a foundation, an association or a religious community and they should get approved by the municipality and the Swedish School Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen) (Skolverket, 2019e). They function exactly like the public schools, under the same rules, regulations and frameworks. According to the Education Act (2010: 800) (Ministry of Education, 2010), the municipalities should give a grand to the preschool’s principal for each child that attends the independent school and funding for the operational costs of the preschool (chapter 8, paragraphs 21-24).

Something else that is worth mentioning is the spending of Sweden in education. Sweden’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the year of 2017 was 51.405 US dollars per capita, while the average GDP for Europe in 2017 was 42.091 US dollars per capita (OECD, 2019). This means that Sweden is eligible to spend more money on education than many other countries in Europe. And this is the case. In 2017 Sweden spent 6,6% of the GDP on education expenditure, when the average spent of the EU countries was 4.7% (European Commission, 2018b).

2.5.

ECEC system in Sweden

After getting a general picture of Sweden's education system, let's see now how the education system in ECEC is organized in more details. ECEC in Sweden is divided in four categories: the preschool (förskola), the preschool class (förskoleklass), the open

preschool (öppen förskola) and the pedagogical care (pedagogisk omsorg) in family day care homes (familjedaghem). Skolverket has the responsibility for all the above. Sweden has totally 290 municipalities that are accountable for child care (Brodin & Renblad, 2014).

17

The preschool (förskola) is the first stage of the education system and it aims at stimulating the children’s learning, care and development holistically and according to their needs through a safe environment while preparing them to continue their education (Ministry of Education, 2010). The municipality offers a place to the resident children from 1 to 5 years old, so they can optionally be entitled to preschool (Skolverket, 2019c). The minimum time that a child can attend the preschool is 15 hours per week, but the municipality can decide on increasing the number of hours according to parents’ employment and family status (studies, full/part-time work, unemployed, parental leave, sick leave, retirement, etc.). Both the public and the independent preschools may charge fees in some occasions. The parents whose child attends more than 15 hours per week and have to pay a reasonable fee that the municipality sets and is controlled by the maximum fee (maxtaxa). Municipalities, parent cooperatives, private companies or NGO’s are usually running the preschools. During 2017, there were 9.791 preschools (7.098 public – 2.693 independent) in Sweden (Doe, 2017d).

Another form of ECEC is the pre-school class (förskoleklass) which is a one-year

class that children attend after they turn 6-years-old and it helps them to have a smooth transition from the preschool to primary school (Skolverket, 2010). The preschool class is obligatory since August 2018. The children who attend the preschool class can also attend the leisure-time center.

Children that are not yet registered in a preschool can attend the open preschool (öppen förskola) (Ministry of Education, 2010). There the parent can socialize and get support on how to educate their child while the child gets pedagogical support in a group (Skolverket, 2019c). This form of ECEC has no strict attendance but it is completely up to the parents for when they want to go to the open preschool. During 2017, there were 485 open preschools (Doe, 2017d).

The last form of ECEC in Sweden is the pedagogical care (pedagogisk omsorg) in family day care homes (familjedaghem) (Ministry of Education, 2010; Skolverket, 2019b). The pedagogical care is governed by the Education Act and is run by registered childminders or teachers in their own house or in a special room for the time that parents are studying or working and it is offered to children from 1 to 12-years-old.

One thing that is important to know about preschools is that there are two professions in the work team: the preschool teachers (förskollärare) and the childminders (barnskötare). In the Swedish context, someone is consider to be a preschool teacher only if he/she is a legitimized/qualified preschool teacher by Skolverket with a qualification bachelor’s degree in preschool education (Ministry of Education, 2010). The preschool teachers are the ones who are responsible for teaching and evaluating and control the content of teaching and if this agrees with the development and learning tasks and goals in the curriculum (Skolverket, 2016, 2019d). On the other hand, the childminders are people who have some or no experience in working with children or might have some -but not enough- education on children’s education and development (Skolverket, 2017). Childminder work in cooperation with a preschool teacher, they participate in the teaching process.

18

Sweden seems to have a well-organized ECEC system but how is this captured through the country’s economy and how is it reflected on statistics? Sweden invests a significant amount of money in ECEC education and this is more evitable when it is compared with other countries. OECD countries spend an average of 0.6% of GDP in ECEC, with countries like Australia, Greece, Ireland and Japan having spent less than 0.3% of their GDP in 2015. At the same time, Sweden has spent 1.3% of the GDP in ECEC and it was the country with the highest GDP spending out of all the OECD countries (OECD, 2018). Overall, 22% of the total funding spent on education in 2016 went on preschool education (Statistics Sweden, 2017).

The high spending can be explained by the increased enrollment rates. According to Skolverket’s statistics (Doe, 2017d), the enrollment rate in preschools for 2017 was 48,6% for the 1-year-old children, 89,2% for the 2-year-old children, 92,7% for 3-year- old children, 94,3% for the 4-year-old children and 94,5% for the 5-year-old children. Around 20% of the enrolled children in Sweden attend a private ECEC institution (OECD, 2018). The average teacher to student ratio is 1:5.56 (UNESCO, 2016). It is evident that the levels of participation in the preschool are really high, except from the under 2-year-old group. A reason that could possibly explain these rates is the policies that Sweden has established in order to augment access to ECEC for immigrants and ethnic minority groups. These policies aim to integrate these people into the Swedish society by giving them the chance to meet the Swedish culture and language and broaden their network. Sweden tries to integrate newcomer immigrants by:

“encouraging their enrolment in high-quality early childhood education and care…by providing equity for economically disadvantaged children, easing the transition of new immigrants into new cultures, or supporting indigenous cultures” (OECD, 2018, p. 167).

2.6.

Language situation in Sweden

The Language Act (2009:600)1 (Ministry of Culture, 2009) is the most significant law about languages in Sweden. The law was enacted on the 28th of May in 2009 by the parliament (riksdag).

The sections 4-6 (Ministry of Culture, 2009) refer to the Swedish language which is the “the principal language in Sweden” (p. 1) that all residents should have access to. Swedish is used and developed by the public sector. The sections 7 and 8 recognizes Finnish, Meänkieli (Tornedal Finnish), Romany Chib, Sami and Yiddish as the official minority languages that the public sector should protect and support. Protection and support should also be provided for the Swedish sign language (section 9). In the long run, Swedish is the principal language used in the public sector and in international contexts, since it is an officially recognized EU language. At the same time, there is also the right to use the official minority languages or other Nordic languages in some cases.

19

The sections 14 and 15 (Ministry of Culture, 2009) is about the “individuals’

access to language” (p.3). There, it is stated that everyone who lives in Sweden should

have the possibility to study, cultivate and use Swedish, everyone who belongs in an official national minority should do so for his/her language, everyone who is deaf/has hearing problems should do so in the Swedish sign language and finally, everyone with another mother tongue than the ones mentioned above, should be given the opportunity to develop and use their mother tongue. However, when it comes to education, the Education Act (Ministry of Education, 2010) clarifies that in order to get mother tongue education, there should be at least one parent who has another mother tongue than Swedish, the student should speak this language every day and has basic knowledge of it and there should be at least five students with the same mother tongue in the same municipality.

According to Statistics Sweden (2018), the number of people with a foreign background has raised the last years due to high levels of immigration. As people with a foreign background are consider those who were either born abroad or who have two parents that are born abroad. For the year of 2017, the percentage of people with a foreign background in Sweden was 24,1% (Statistics Sweden, 2018). The situation in the preschool is close to that. In 2015, a total of 35,4% of children under 4-years-old had a background with family migration (Statistics Sweden, 2016 as cited in Schreyer & Oberhuemer, 2017). Lindberg (2007) and Parkvall (2015) support that there are approximately 150-200 minority languages that are used in Sweden because of the immigration, but they are not officially recognized. Parkvall (2015) investigated the numbers behind the languages in Sweden through statistics. The research was conducted in 2012 and show the number of mother tongue speakers on each language (table 2).

Table 2: The ten most spoken languages in Sweden in 2012 (Parkvall, 2015).

Language Mother tongue speakers

Swedish 8.000.000

Finnish (including Meänkieli) 200.000

Arabic 155.000 Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian-Montenegrin 130.000 Kurdish 84.000 Polish 76.000 Spanish 75.000 Persian 74.000 German 72.000 Danish 57.000

The Swedish education system seems to strongly consider the non-Swedish speaker students and provide support to them either by teaching Swedish as a second language and by providing support or tuition in their mother tongue. Multilingualism in preschool is expressed through the importance of all the children developing the Swedish language

20

and then minority languages, mother tongues of individuals and the Swedish sign language should be supported (Skolverket, 2019a).

Nevertheless, the Swedish School Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen, 2017) published a report based on the examination of 34 preschool about multilingualism. The report shows that almost all preschools are consciously trying to support, inspire and stimulate the children to use the Swedish language in their everyday life. However, 23/34 preschools did not work strategically towards multilingualism and mother tongues and the main reason for that was either because the staff’s competence and confidence for multilingual development was low, or because they did not have a clear idea of the how they should develop mother tongues.