Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2018

Supervisor: Hope Witmer

Sports and Social Sustainability

Female Empowerment through Physical Education

in Sri Lankan High Schools

Acknowledgements

To Ilse, Andy, Julius, Scotty P, Jack, Stefanie, Anna and Kevin: because you are the ones that made all of this possible. Thank you so much for all these unforgettable memories and for sharing tears,

laughs and lions with us!

We are very grateful to our siblings, parents, our whole family and friends, who have provided us through moral and emotional support in our life and throughout this thesis process.

Special thanks to Hope Witmer, who supported us from day one on. Thanks SALSU for being our second family for the last 10 months.

Thank you Vika & Lena for being our lab partners, STPLN Crew for providing us with your creative space, Lena & Hanna for just being you, Sophie for your unconditional support and friendship, Collin

for your awesome feedback, Abdallah for providing us with food, Yoerik for this beautiful picture, Lukas for your charger and Tiffany & Cody for letting us participate at the kids’ swim and surf lesson.

And the biggest thanks to all interviewees in Sri Lanka, Lund and Copenhagen! Thanks for sharing your stories with us.

Abstract

This inductive research paper addresses the issue of gender inequality among the youth in Sri Lanka. Thus, semi-structured interviews with (former) students were conducted to investigate how physical activities and physical education in Sri Lanka can contribute to female empowerment on a personal, relational and societal level in order to reach gender equity. Taking the ‘Ecological System Theory’ and the ‘Three-dimensional Model of Women Empowerment’ as an analytical lens, the perspective of Sri Lankan high school students was explored. Key findings highlight the importance of a safe class climate characterized by a motivational environment and a strong social network to enable empowerment to unfold. However, the society's cultural values and beliefs can hinder this process and restrain physical education to be a catalyst for female empowerment. Finally, directions and challenges for practical management to counteract gender prejudices are identified and future research is outlined.

Keywords: Gender, Gender Equality, Gender Equity, Female Empowerment, Physical

Education, Physical Activities, Sports, Sri Lanka, High School Students, Child’s Development, Safe Space, Class Climate, Social networks, Culture

Table of content

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 History, culture and the role of gender in Sri Lanka ... 1

1.1.2 Sri Lankan school system ... 2

1.1.3 Impact of physical education on females ... 3

1.2 Definitions of terms ... 4

1.2.1 Gender inequality and gender equity ... 4

1.2.2 Female empowerment ... 4

1.2.3 Physical education (PE) and physical activities (PA) ... 5

1.3 Research problem ... 5

1.4 Purpose ... 6

1.5 Research questions ... 6

1.6 Structure ... 6

2. Conceptual framework ... 7

2.1 The process of empowerment ... 7

2.1.1 Dimensions of empowerment ... 9

2.1.2 Motivational (task-oriented), ego-oriented and safe PE class climate ... 10

2.1.3 Impact of culture ... 12

2.2 The interplay of development, female empowerment and PE ... 12

3. Methods ... 14

3.1 Research approach and design ... 14

3.2 Data creation and collection ... 15

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews ... 15

3.2.2 Key informant interviews and field observation ... 17

3.3 Data coding, organizing and analysis ... 18

3.4 Research reliability, validity and limitations ... 19

3.4.1 Reliability and validity ... 19

3.4.2 Limitations ... 19

3.5 Ethical Consideration ... 21

4. Findings ... 22

4.1 Availability and access to PE ... 23

4.1.1 Availability of PE ... 23

4.1.3 Summary of availability and access to PE ... 25

4.2 Motivation, ego-orientation and safety climate ... 26

4.2.1 Motivational (task-oriented) or ego-oriented PE class climate... 26

4.2.2 PE classes as safe spaces ... 29

4.2.3 Summary of PE class climate ... 32

4.3 Three dimensions of empowerment ... 32

4.3.1 Societal empowerment and societal restrictions ... 33

4.3.2 Relational empowerment in the interplay with societal restrictions restrictions 34 4.3.3 Personal empowerment ... 36

4.3.4 Summary of personal, relational and societal empowerment ... 38

5. Discussion ... 39 5.1 Theoretical discussion ... 39 5.2 Practical contributions ... 40 5.3 Future research ... 40 6. Conclusion ... 42 References ... I Appendix ... VI Appendix 1: Semi-structured interview questions for (former) students... VI Appendix 2: Sample of key informant (KI2) interview questions ... VI Appendix 3: Pictures of interviews and field observation ... VII

List of figures

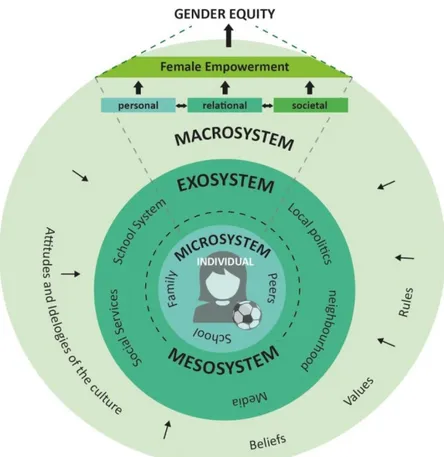

Figure 1: The Ecological Systems Theory of Bronfenbrenner (1994) ... 8

Figure 2: The three dimensions of female empowerment ... 8

Figure 3: Conceptual framework ... 13

Figure 4: Investigated high schools in Sri Lanka ... 20

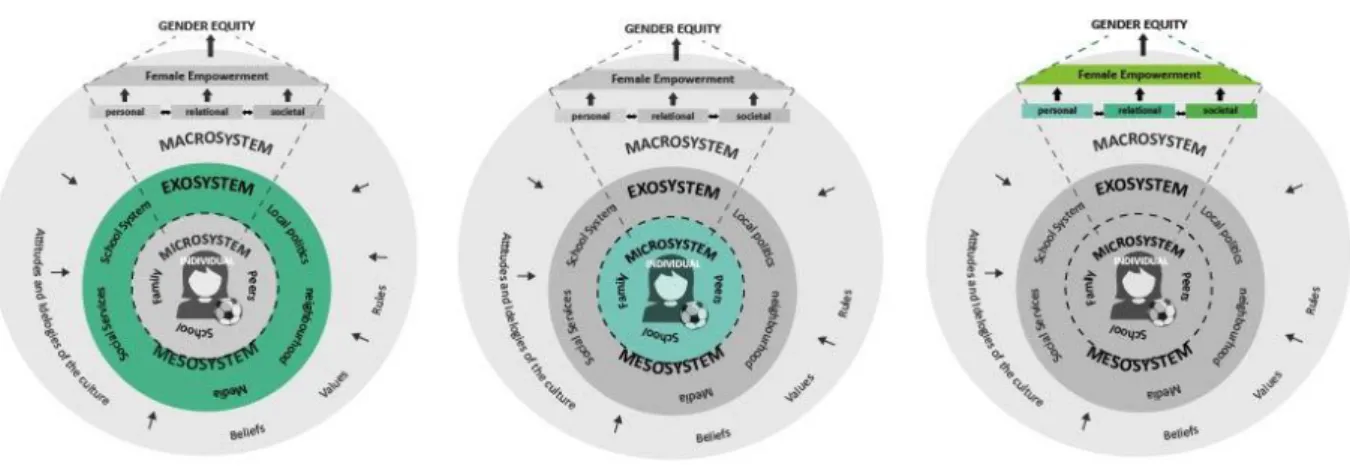

Figure 5: Three parts of analysis ... 22

Figure 6: Exosystem ... 23

Figure 7: Micro- and mesosystem ... 26

Figure 8: 3DMWE ... 32

List of tables

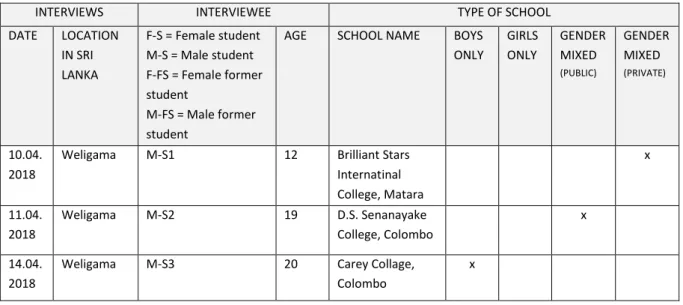

Table 1: Overview of semi-structured interviews ... 16List of abbreviations

3DMWE Three-Dimensional Model of Women’s Empowerment EST Ecological Systems Theory

FO Field Observation

KI Key Informant

PA Physical Activity PE Physical Education PT Physical Training F-FS Female Former Student

F-S Female Student

M-FS Male Former Student

M-S Male Student

1

1. Introduction

“Empowering women is seen as one of the central issues in the process of sustainable development for many nations worldwide” (Huis, Hansen, Otten and Lensink, 2017, p.2). Attempts at ensuring basic rights of women go back to the year 1945, when the United Nations Charter declared the UN resolution to promote universal respect for and observance of human rights and dignity, regardless of race, sex, language, or religion (Chaudhuri, 2013). Reaffirming their commitment 70 years later, the United Nations presented 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to, amongst other things, strive for gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls (SDG No. 5) within the following 15 years (UN Women, n.d.). The Global Gender Gap Report 2017, published by the World Economic Forum (2017), outlines how the failure to socially integrate women and girls results in the loss and underdevelopment of skills, ideas, and perspectives that are crucial for facing local and global challenges.

Signatories of the UN SDGs across the world are striving to meet these objectives with more or less commitment and success; for many the issue of gender equality is the most intractable of all the SDGs. Sri Lanka is an example of one of these countries that struggles with gender inequality – the island ranks number 109 out of 144 countries in 2017 (No. 100 out of 144 in 2016) in terms of gender equality (World Economic Forum, 2017). There are different ways to tackle gender inequality. Physical education (PE) is one way to capture gender dynamics and attempts to improve them (Haseena, 2015, Tom & Praveen, 2018). Post-war Sri Lanka is in the process of development, which brings the opportunity to positively influence the process during the early stages (The World Bank, 2016).

Hence, this research study focuses on gender inequality in Sri Lanka and has as its focal point the PE classes in local high schools, which will be explored through the lens of female empowerment and gender equity. To better understand the context, the following sections will provide an introduction to the topic.

1.1 Background

1.1.1 History, culture and the role of gender in Sri Lanka

Gender reflects cultural norms and values (Cuddy, Crotty, Chong & Norton, 2010). Hence, it is important to first understand the cultural context in which the observed schools are embedded. Sri Lanka is a country with a wide range of different ethnic and religious groups, including Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, Malays, Parsis, and the indigenous inhabitants, the Veddas (Schulenkorf, 2010). Given the historical, geographical and socio-cultural context of the country, it has always been a multi-ethnic society with deep historical roots and a high potential for political conflicts (ibid). After the end of a more than 25 years long civil war in 2009, the social, economic, and political consequences of the war are still visible on the island. Today, Sri Lankan society continues to be marked by different ethnic, religious, linguistic, and geographical divisions that lead to tensions, ethnic conflict and contribute to gender inequality (ibid). In addition, natural catastrophes like the tsunami in 2004 and several floods within the last years (Reuters, 2017) aggravate the living conditions and have left its marks in the Sri Lankan society.

2 Female labor force participation is often seen as the prime indicator of change in the status of women (Hasanovic, 2014). According to the ‘Quarterly Report of The Sri Lanka Labor Force Survey 2017’, only 36.9 percent of the economically active population is female, whereas within the economically inactive population (about 7.3 million) 73.8 percent are women. Hence, women are still under-represented in upper management and leadership positions in the private and public sector (Kovinthan, 2016, Weeratunga, n.d.). Business positions or professions which are traditionally considered “male occupations” such as pilots are rarely chosen by women (Hasanovic, 2014). This subordinated role in labor market reflects women’s social position and expectation – not only in the economic environment but also in a family and in society in general (ibid).

In Sri Lanka, a country where religion, traditional culture and politics have a strong hold on society, efforts to protect traditions run the risk of creating cultural and social barriers when it comes to changing the role of women and improving gender equity (Nanayakkara, 2012, Kovinthan, 2016, Senne, 2016). Traditional views of the ‘sacred’ family represent strong opposition to changes in gender relations (Kovinthan, 2016). The hostility of many towards moving away from the traditional ideal of ‘the good woman’ – taking care of the children and house – creates a “dangerous space for women and girls who may challenge the status quo” (Kovinthan, 2016, p.4).

1.1.2 Sri Lankan school system

The aforementioned gender inequality in Sri Lanka is also present in their education system. Due to cultural and economic reasons, girls in Sri Lanka did not attend school until 1947, when a free and compulsory education system was introduced (Weeratunga, n.d.). Today, in Sri Lanka there are 9.931 public (free of charge and owned by the government), 98 private (international and not free of charge) and 734 privivena (school for Buddhist monks) schools (Liyanage, 2013). The public schools can be either girls, boys or mixed schools and all private schools are mixed gender schools. The education systems comprises of 13 years of school, starting with primary school at the age of 5, continuing with junior and senior secondary school from 11 until 16 years old and finishing with collegiate/tertiary at the age of 18/19 (ibid). For this research study, the authors decided to focus on junior and senior secondary schools as well as collegiate/tertiary, and define these school years from grade 6 until grade 13 as ‘high school’.

The equal access for girls to primary, secondary and tertiary education has been an important component in the idea of gender equality (Kovinthan, 2016). Secondary education in particular has the potential to enhance women’s control and power in their life (Kabeer, 2005). The access to basic human rights, which has a significant positive influence on the empowering process during adulthood such as employment prospects, is often neglected in childhood (Chaudhuri, 2013). Instead of challenging traditional gender norms, education in post-war Sri Lanka has upheld existing gender rules that devalued the status of women and girls in society (Kovinthan, 2016). There are cases presented in studies where teachers show strong gender biases and ideologies by paying more attention to boys and automatically judge the abilities of girls to be lower (Kabeer, 2005, Kovinthan, 2016). Gender stereotyping

3 within the school environment often mirrors social inequalities of the society at large. Girls are portrayed as passive, modest, and shy, while boys are seen as assertive, brave, and ambitious (ibid). Consequently, within this scope of gender roles in society, the opportunity for girls to empower themselves has been limited.

1.1.3 Impact of physical education on females

The history of female participation in sport is marked by discrimination and division. However, it is also filled with great accomplishments by female athletes as well as advances for female empowerment and gender equality in general (United Nations, 2007). The importance of sport and its positive impact for all genders and especially for females has gained increased awareness in politics and research throughout the recent years (see Theberge, 1987, Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001, Lindgren et al., 2011, Haseena, 2015, Tom & Praveen, 2018). Sport is no longer just seen as luxury. Politicians and policy makers increasingly recognize the significance of sport to society (van Eekeren, ter Horst, & Fictorie, 2013). An example of this change of thinking was expressed in 2015 when the UN General Assembly dubbed the 6th of April ‘International Day of Sport for Development and Peace’ (IDSDP) (United Nations, n.d.). Further evidence of an attitudinal shift in regards to sport is demonstrated in the many acts and guidelines implemented to promote the participation of girls and women in sport, such as the ‘Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines’, which recommends a minimum of 60 minutes of physical activity (PA) per day for children by the age of 5 years (Tremblay et al., 2012) or the ‘Education Amendment Act’ called ‘Title IX’ in the United States (Women’s Sports Foundation, 2011). ‘Title IX’ prohibits and punishes the discrimination of women in all educational programs and activities, including sports, from elementary schools to colleges and universities in the United States (ibid).

Lakshmi Puri, the representative of UN Women, further confirmed this view that sport held great power as a tool for female empowerment (Puri, 2016). According to her, in sports, females defy misperceptions about prejudices they face as weak or incapable by demonstrating physical strength, strategic thinking, as well as through gaining leadership skills and thereby tearing down gender barriers, stereotypes and discrimination (ibid). Hence, sport can have a major impact on the advancements of human rights and socio-economic development, in particular in terms of female empowerment (Bailey, Wellard & Dismore, 2005, Nanayakkara, 2012, Puri, 2016). However, the aforementioned advancements for women do not have to start in adulthood but instead, effective female empowerment can be achieved at an early age through PA and PE (VanSickle, 2012). Regular PA improves the physical, psychological and social health of school-aged children and youth (Bailey et al., 2005, Janssen & LeBlanc, 2010, Poitras et al., 2016).

In Sri Lanka, most public schools are gender-segregated and also in mixed schools, there is a clear division between boys and girls during classes (Dencker Løwe Jacobsen, 2017). This segregation is also apparent in the different schools’ curriculums such as with regards to the amount of PE classes. While the school system attaches importance to keeping alive the country’s passion towards sport also among the youth (Wood, 2015), there is still a great gap between genders in equal access to sport for children inside as well as outside of school

4 (according to KI1, personal communication). There is evidence that gender-based attitudes play a major role in a children’s participation in PA (Bailey et al., 2005).

1.2 Definitions of terms

1.2.1 Gender inequality and gender equity

The term gender refers to “non-biological, culturally and socially produced distinction between men and women and between masculinity and femininity” (Gunawardane, 2016, p.66). Gender does not only mean the biological sex (also addressing people with transgender or intersex identities), but also includes relational, hierarchical, historical, contextual and institutional elements, and gender expectations that can vary and change over time (WHO, n.d.). These expectations define how people “should interact with others of the same or opposite sex within households, communities and workplaces (gender relations)” (ibid). Although it is clear that gender is a social construct that goes beyond the distinction of the biological sex, it is important to mention that within this study, by referring to “gender”, the paper mainly focuses on the distinction between female and male.

The term is used as a construct to describe the social structure regulating and maintaining unequal power relations between women and men and determines the roles, behaviors, activities and attributes that a particular society believes are appropriate to women and men (Hasanovic, 2014, Gunawardane, 2016). According to Longwe (2002), gender inequality should be understood as women having less access to facilities, opportunities and resources, resulting in the allocation of resources and opportunities. The United Nations (as cited in DCAF, 2017) describes gender equality as the equal enjoyment of socially-valued goods, rewards, resources and opportunities by women and men. Based on this understanding, gender equality is the end goal – equal rights and conditions – while gender equity refers to the process of reaching equality, consisting of ensuring fairness and compensating for gender disadvantages (DCAF, 2017). Within this research paper, the focus is set on gender equity as the essential means through which gender equality and the needs of women needs will be reached.

1.2.2 Female empowerment

From a feminist approach, gender inequalities are anchored in the social processes, norms and concepts of society; leading to feminist studies and movements promoting women’s rights and interests to effect social change (Hasanovic, 2014). In regards to PE, liberal feminism has focused on the disparities between activities offered to boys and girls, the “different socialization of girls and boys into gender-specific activities; stereotyping and attitudes, and unequal access to facilities and opportunities” (Green & Hardman, 2005, p.162).

Women empowerment captures the process through which women gain the confidence, strength, information, and skills needed to make strategic choices to improve their lives

5 (Kabeer, 2005). In this context, empowerment is defined as a process that gives power to the disempowered and increases their ability to make strategic choices. It differs from autonomy as it is not an independent static concept but rather a process that is influenced by several factors. While empowerment is a constructive approach for addressing gender inequalities in society and enabling women to achieve desired outcomes, it is essential to look at other factors that may inhibit or hinder this process (ibid). These factors are further developed and examined in this paper (see chapter 2).

1.2.3 Physical education (PE) and physical activities (PA)

As the terms ‘physical education’ (PE), ‘physical activities’ (PA) and ‘sport’ are used in a broad definition, a short clarification is given in the following. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) describes PA as any form of bodily movement, performed by a muscle, or group of muscles that leads to an increase in one’s energy expenditure. Sport exists as a form of PA, and has a similar concept as PA, fitness and exercise, but includes rules, elements of competition, physical exertion and skill, amongst other things. Within the given research frame, PE refers to the educational process at school ”that aims to improve human development and performance through physical activity” (Gleaner, 2015). It includes formal lessons as well as informal physical activities and aims at developing specific knowledge, skills, and understanding for children (ibid).

1.3 Research problem

In contemporary literature, female empowerment is defined as a multifaceted process that is influenced by various factors of different environments (Bronfenbrenner, 1994, Ettekal & Mahoney, 2017) which can happen on the personal, relational and societal level (Huis et al., 2017). Research shows that sport can be an effective tool for achieving female empowerment (e.g. Theberge, 1987, Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001, Lindgren et al., 2011, Haseena, 2015, Tom & Praveen, 2018). However, the specific impact of PE in schools on each component of female empowerment, from the individual level all the way to the macro, has yet to be explored. This report seeks to add to the understanding of this relationship between sport and female empowerment by distinguishing between distinct outcomes and challenges found at the three dimensions of empowerment.

Therefore, this research paper will contribute to the existing body of knowledge about PE and female empowerment by combining the two assumptions: “sport is a tool for female empowerment” and “female empowerment is happening on the personal, relational and societal level”. Furthermore, one major factor that influences whether sport has the ability to empower females is the group climate and environment within which sport takes place (Seifriz, Duda and Chi, 1992, Walling, Duda & Chi, 1993, Moore and Fry, 2017, Harwood et al., 2015, Gano-Overway, 2013, Newton et al., 2007). By investigating the impact of sport as a tool for personal, relational and/ or societal empowerment with a focus on the PE class climate and in the context of Sri Lankan high schools, new knowledge is added to existing research.

6

1.4 Purpose

The purpose of this research paper is to explore the perceptions and experiences of Sri Lankan high school students of physical education through the lens of female empowerment and gender equity.

1.5 Research questions

How do students perceive PE classes in regard to motivation, ego-orientation and safety climate?

How do the students perceive the contribution of their PE classes to personal, relational and societal female empowerment?

1.6 Structure

This paper is organized into six main chapters with further subchapters. The first chapter provides detailed background information about the context and the purpose of this study. In the second chapter, relevant theories and the conceptual framework are presented. Chapter three provides a detailed description of the methods that are used for the data collection and analysis and why those methods were chosen. In the fourth chapter, the data presentation is summarized and findings from the research and their analysis are presented. Before ending with the conclusion, the key findings will be summarized and discussed in the fifth chapter. Lastly, recommendations for future research and practice will be deduced.

7

2. Conceptual framework

This chapter presents the conceptual framework in which the research paper is anchored. Research on the impact of PE and PA supports the claim that sport is an effective tool for female empowerment (e.g. Theberge, 1987, Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001, Bailey et al., 2005, Lindgren et al., 2011, Haseena, 2015, Tom & Praveen, 2018). However, there are several factors influencing whether or not sport can actually have the power to be a catalyst for female empowerment. To place it within the larger field of study, this research paper identifies how previous studies assess the interrelations between sports, female empowerment and gender equity. Existing research and literature will be presented to provide a comprehensive understanding of perspectives and methodologies that have been employed when exploring these interrelated issues. This chapter will explain how contemporary research views empowerment as a process of development as well as how and why different factors can have an impact on this development process (see section 2.1). Based on these theoretical perspectives, a conceptual framework was developed and will be presented at the conclusion of this section (see 2.2).

2.1 The process of empowerment

Ecological Systems Theory (EST)

According to the EST of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994), the term of empowerment can be understood as a process of an individual’s personal development. This theory is used by various researchers to explain how activities foster a healthy and positive development for children from different backgrounds and what role the particular environment that they are acting in plays in this development process (Ettekal & Mahoney, 2017). Bronfenbrenner’s EST consists of four different environmental systems: the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem and the macrosystem. The theory proposes that the development of children is directly influenced by their own experiences within (microsystem) and between (mesosystem) different systems (e.g. school, family, friends), as well as indirectly influenced (exosystem) by factors that the child is not directly part of (e.g. schoolpolicy). All three lower-order systems (micro, meso, exo) are then again under the influence of the country’s society’s cultural beliefs, attitudes and norms (macrosystem) (ibid).

8

Figure 1: The Ecological Systems Theory of Bronfenbrenner (1994)

Three-dimensional Model of Women’s Empowerment (3DMWE)

Based on the EST for development, Huis et al. (2017) propose the 3DMWE. This model consists of three distinct dimensions in which empowerment can take place: personal empowerment (own beliefs and actions), relational empowerment (beliefs and actions with respect to relevant others such as spouse, family and community), and societal empowerment (at the larger social context) (see figure 2). While the 3DMWE was designed for the study of women empowerment in microfinance, it will now be applied in this research study. The three dimensions of this model arise from previous research that has defined the process of empowerment as the ability to make individual choices about the following three different aspects: agency, resources and achievements (Kabeer, 2005). The 3DMWEs personal dimension equates ‘agency’, which refers to the people’s ability to act upon their own choices despite possible oppositions; in a negative sense it encompasses the authority over other people which may also include the use of violence. In line with the 3DMWE, certain bias and norms as institutional, cultural or ideological ones can have an impact on power relations and people’s ability to decision-making (ibid). Resources (referring to the relational dimension) include the material and social allocations through various institutions and the society (Kabeer, 2005, Huis et al., 2017). The outcomes of the independent decision-making to live the desired life, including for example the improvement of well-being and the achievement of equal gender roles in politics, form the term of achievement (relating to the societal dimension) (Huis et al., 2017). Changes in one dimension can entail positive as well as negative impacts on the other dimensions, reflecting the interconnection and interdependence within the process.

9 With regard to the two above presented models (EST and 3DMWE), the following three key parts will provide different perspectives on the research topic of sport as a tool for female empowerment. First, empowerment through sport will be placed within the three dimensions of the 3DMWE. Second, the perceptions of the PE class climates regarding motivation, ego-orientation and safety climate will be investigated as it is part of the relational dimension and belongs to the micro- and mesosystem of the EST. And lastly, to address the macrosystem, the impact of a society’s culture on the power of sport as a catalyst for girls’ empowerment will be assessed.

2.1.1 Dimensions of empowerment

Huis et al. (2017) define empowerment as a multifaceted process, which involves individual as well as collective awareness, beliefs, and behavior embedded in the social structure of specific cultural contexts and thereby distinguishes between personal, relational and societal empowerment.

Personal empowerment

Empowerment initiatives or actions that boost empowerment on the personal level have according to Huis et al. (2017) a positive impact on the following individual’s characteristics and attributes: control beliefs, self-confidence, self-esteem and self-efficacy. They encounter psychological aspects regarding individual actions and personal beliefs. ‘Control belief’ means the extent to which women are aware of their power to decide about their personal life outcomes and the belief in their ability to choose the direction of their personal life (Huis et al., 2017, Hansen, 2015). ‘Self-confidence’ needs to be developed to make one’s voice heard in public spaces, to be confident enough to defend own opinions or to offer advice to others (Huis et al., 2017). ‘Self-esteem’ as indicator for self-empowerment draws attention to the emotionally value of one’s own worth (Kato & Kratzer, 2013), whereas ‘self-efficacy’ is the ability to cope with difficult situations and can be shown in the ways women interact with family members, neighbors, friends, community members or people outside their immediate environment (Huis et al., 2017, Kato & Kratzer, 2013). In this context, Hansen (2015) emphasizes the impact of people’s belief in their own efficacy on their personal motivation, life choices, their functioning, or coping strategies and thus on their capacity for action. Relational empowerment

Power cannot just be possessed by an individual, but is defined by the relationship to others (Christens, 2012). This is why women’s empowerment can also be measured by the women’s position in relation to their environment in terms of their partner, family, or social networks – which is described as “relational empowerment” (Huis et al., 2017). According to Huis et al. (2017) – in the context of microfinance services to women – the following factors are relevant when assessing whether a women is relationally empowered or not: making power, freedom of mobility and number of social networks. First, in terms of decision-making, women are often dependent on their husbands’ decisions, for instance in terms of

10 household spending (Hansen, 2015). Without a sense of power over their own life outcomes, their voices remain unheard and decisions are made by others (ibid). Second, empowerment includes also the freedom to move freely in order to visit places outside home or outside the village such as a grocery store or sports clubs. And third, the importance of social networks can be seen in interrelations between group members as social support that can help in dealing with difficult situations (Hansen, 2015) and community involvement can positively affect the intrapersonal component of empowerment (Christens, 2012). The social network size is defined by the number of school groups, sports groups, memberships etc. that one is part of (Hansen, 2015) and is a significant aspect of one’s relational empowerment. These networks can help individuals to develop a higher self-esteem, higher motivation, or to control personal behavior (Fleury & Lee, 2006). Overall, the interpersonal relations can help in reaching justice and equal power, especially within youth empowerment (Christens, 2012). Societal empowerment

The dimension of societal empowerment comes from a macro perspective as it is about a culture shaped by norms, beliefs and values (Huis et al., 2017). This dimension of empowerment is concerned with women’s position in society and women’s position relative to men as well as by the percentage of female leaders and women’s opportunities and rights in education (ibid). Certain values and rules within a society also influence the relational empowerment process, as women in countries like Sri Lanka are supposed to interact with family members in respect to social norms (Hansen, 2015). This can be measured through official reports like the Gender Development Index or the Gender Gap Report (see section 1.1.1) to draw conclusions about gender gaps in certain societies. With regard to the topic of this paper, the societal dimension can contribute to the extent to which girls are supported to attend schooling and participate in sport programs.

2.1.2 Motivational (task-oriented), ego-oriented and safe PE class climate

According to the EST, a child’s development is influenced by different ecosystems (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). From the microsystem perspective, a PE class climate can have a major influence on the ability of sport to be a tool for female empowerment (Bailey et al., 2005, Gano-Overway, 2013, Harwood et al., 2015, Moore and Fry, 2017). But, just the availability of PE classes does not necessarily promote PA and an inappropriate provision can have negative results for students, especially for girls (Bailey et al., 2005). Looking at existing research, three main groups of class climates can be observed, namely motivational (task-oriented), ego-oriented and safe climate.

Motivational (task-oriented) and ego-oriented climate

The goal perspective theory by Nicholls (1984, 1989) states that there are two different ways that an individual can perceive success in achievement-situations like sports. On one side there is task-orientation, which refers to an individual that experiences success through trying hard and improving performance. Ego-orientation on the other side describes an individual that measures success by comparing ones performance favorably to others (Walling, Duda & Chi, 1993). The work of Nicholls (1984, 1989), Ames and Archer (1988) indicates that

11 classroom environments also can be characterized as either task- or ego-oriented. Seifriz, Duda and Chi (1992) extended the work of Ames and Archer (1988) into the sports domain and found out that a task-oriented PE class climate (being rewarded for trying hard; every student has an important role in the team) supports the student’s personal improvement as well as her or his enjoyment and motivation in PE. Whereas an ego-oriented PE class climate (students outdo each other; teachers’ recognition is limited to the best players) leads to a decrease of enjoyment and reduced self-esteem (Seifriz, Duda and Chi, 1992, Walling, Duda & Chi, 1993). Further PE and PA research demonstrate the correlation between a motivational climate (promoting students’ self-development and fostering performance goals) within a sports class and positive outcomes such as students’ enhanced self-esteem, better group performance, student’s enjoyment and motivation (see Harwood et al., 2015, for a review). At the same time, an ego-oriented climate (competitive or fearsome) leads to antisocial moral attitudes or demotivation within the group (ibid). Furthermore, Moore and Fry (2017) assessed the relationship between a student’s feeling of ownership (e.g. student gets the chance to determine the rules of a game) in a PE class and her or his feeling of empowerment to also be physically active outside of PE classes. The quantitative study with high school students supports the proposition that satisfying experiences, such as feeling ownership, imply a beneficial effect on the students’ self-confidence and their feeling of empowerment to continue being physically active outside of school (Moore & Fry, 2017). Similar positive PE experiences are supportive for lifelong PA habits, whereas a climate dominated by demotivational and competitive (ego-oriented) aspects fail to address the interests of students and can harm such healthy practices (Bailey et al., 2005).

Safe space

Creating a caring climate – one that makes students feel safe, welcomed, valued and respected – in PE classes supports students’ positive social behavior (Gano-Overway, 2013, Newton et al., 2007). Gano-Overway (2013) explored the behavioral patterns of high school PE students when teachers provide a caring class climate. The study results show that when students perceive PE classes as safe spaces, where teachers and other students show empathy, make each other feel valued and respected, they develop enhanced prosocial behavior, characterized as a sharing, helping, inclusive and caring behavior (ibid).

According to the UN Women (as cited in Groot, Mohlakoana, Knox & Bressers, 2017) empowerment means “that people – both women and men – can take control over their lives: set their own agendas, gain skills (or have their own skills and knowledge recognized), increase self-confidence, solve problems, and develop self-reliance. It is both a process and an outcome” (p. 88). Hence, increasing self-confidence is one major part for a girl’s path from being unpowered to being empowered that can be achieved in an environment where girls feel safe.

To summarize, a motivational (task-oriented) climate as well as an environment that is perceived as a safe space (Gano-Overway, 2013) are necessary to enable girls to develop themselves and to empower.

12 2.1.3 Impact of culture

Different empowerment researchers explored the impact that the cultural factors – embedded in the macrosystem – have on the empowerment of women (see Nanayakkara, 2012, Hansen, 2015, Gunawardane, 2016, Senne, 2016, Huis et al., 2017). Social, cultural, political and economic barriers can derive from gender-related norms and prejudices and affect the process of development (Nanayakkara, 2012). As proposed by the authors of the 3DMWE, culture is a major moderator in the empowerment process (Huis et al., 2017). Besides the factor of time, which refers to empowerment being a continuing process, culture explains why some women may feel more empowered compared to others and why the outcomes of empowerment interventions may differ from nations to nations (ibid).

To find out about the role of sports in Sri Lankan high schools, one has to consider possible barriers like traditions and perceptions anchored in history and expressed in society. Social factors determine how an individual and the community perceive goals and opportunities for change (Fleury & Lee, 2006). Furthermore, society sets the frame for women’s engagement in physical activity through specific values, motivation, and skills. Certain tasks assigned to females, as for example looking after the children or keeping the house, can hinder girls from participating in physical activities and may be the reason for men to prohibit girls’ engagement in sports (ibid). Thereby the need of a supportive personal and physical environment is stressed to promote PA – including the design of safe neighborhoods to reduce social isolation and facilitating PA.

From a historical perspective, former conflicts or events can have a negative impact on the security of social environments that have existed before. As mentioned in the introduction, ethnic conflicts in Sri Lanka are still evident in culture and politics. Serious events like the Tsunami changed people’s attitudes and contributed to a growing pessimism in parents’ minds regarding safety concerns (Fleury & Lee, 2006). Due to these barriers and safety considerations, girls in particular are still restricted in the participation in sports (see chapter 5). According to the United Nations (2007), women are often considered being too weak for sport. This kind of stereotypes led also to the assumption that sport is harmful to women’s (reproductive) health (ibid). In contrast, it is evident that women who face few barriers to exercise engaged more frequently in PA (Fleury & Lee, 2006). To understand social and contextual correlates of PA in schools, a broad perspective that includes not only the individual but also the social and environmental dimensions is needed to analyze the interdependence of those (ibid). This is why the research questions are analyzed not only from an intrapersonal point of view, but also take into account the interpersonal level, community, environment and culture.

2.2 The interplay of development, female empowerment and PE

The conceptual framework of this research study (see figure 3) is derived from the aforementioned development, female empowerment and PE and PA theories. The frame is based on Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) EST which understands the term of a child’s development

13 as a process influenced by different ecosystems. Moreover, female empowerment is according to the 3DMWE of Huis et al. (2017) divided into three dimensions, namely personal, relational and societal which all play a relevant role on the path towards gender equity. To understand the interconnections between the different approaches, the two theories are combined and together will be used as a guide to frame the research analysis in order to answer the research questions.

To lay a foundation for the further analysis and the investigation of the research questions, special attention will be given to the exosystem, since the school system, including the availability and access to PE, indirectly has an impact on the girls’ process of development. In order to answer the first research question (How do students perceive PE classes in regard to motivation, ego-orientation and safety climate?), the focus will lie on the micro- and mesosystem because the impact of the PE class climate depends on the students’ and teachers’ relations. To explore the second research question (How do the students perceive the contribution of their PE classes to personal, relational and societal female empowerment?), the focus will be extended to the three dimensions of the 3DMWE (Huis et al., 2017). Additionally, the macrosystem and in particular the Sri Lankan culture has an impact on all parts of the conceptual frame and therefore will be considered during all analysis parts. This conceptual framework is designed to combine all parts and perspectives together, to conclusively analyze the overall impact that PE can have on the process of female empowerment and gender equity.

14

3. Methods

This chapter provides an overview of the research design including the methods that are used in this research study to gather the necessary data that will address the purpose of this research. Also the reasons for choosing the intended methods for this specific research will be clarified. After introducing the research approach and design (see section 4.1), the methods of how data was created and collected (see section 4.2) and how the collected data will be coded, organized and analyzed will be explained (see section 4.3). Finally, the reliability, validity, limitations (see section 4.3) and ethics (see section 4.4) of the data are discussed.

3.1 Research approach and design

The research approach and design is based on the formulated research questions describes the “coherent overall plan of the research” (Layder, 2013, p.11). This paper is conducted with an inductive research approach to find out about the patterns or connections by using theories from previous research in order to explore this research topic (Blaikie, 2003, Silverman, 2015). The inductive approach uses the research questions to narrow the scope of the study, and the theoretical framework, including the EST and the 3DMWE, is used as analytical lens. The aim is on exploring the patterns of the situation in Sri Lankan high schools from the student’s perspective. Therefore this approach is more about making assumptions within the research scope then about making overall generalizations. According to Berkwits and Inui (1998), the use of qualitative research methods helps to capture expressive information about perceptions, feelings and motivations. Hence, in order to gain insights about the students’ perception of what role PE plays in empowering girls in the context of Sri Lankan high schools, qualitative research methods seem most appropriate. Viewing the research from an ontological perspective, this study lies within the idea of constructionism and deals with understanding the interpretations by an individual (6 & Bellamy, 2012).

The chosen research method of this paper is semi-structured interviews using open ended questions. Semi-structured interviews have the advantage of ensuring comparability between the interviewees’ perceptions and experiences through the given structure (Tracy, 2013) as well as providing freedom for unstructured aspects of the interviews to allow flexibility and depth of responses (ibid). Furthermore, in addition to the semi-structured interviews with students, which form the basis of the research study, semi-structured and unstructured interviews with key informants as well as one field observation are used in order to explore the research topic from different perspectives and to strengthen the authors’ knowledge about the background of the subject. Using semi-structured but also unstructured interviews for the key informant interviews seem appropriate, because unstructured interviews give the interviewee the freedom to answer questions in her or his own frame of reference without being restricted by leading questions from the interviewer (Rosenberg, 2012). While interviews give the interviewer assumptions about what people are thinking, ethnographic

15 field observations allow the interviewer to first-hand look at what people are doing, which helps to better understand the researched phenomena (Silverman, 2015).

The semi-structured interviews, key informant interviews (semi-structured and unstructured) as well as the ethnographical field observation are conducted and analyzed by the authors themselves and therefore belong to primary data (Blaikie, 2003). Secondary data on the other hand is raw data that is generated by someone else and are used to complement the primary data with further relevant information (ibid).

In the focus of this research topic are countries where gender equity and quality education are still in the process of development. Gender inequality is still a major issue in Sri Lanka (for more information see section 1.1.1) and even though sport is strongly embedded in their culture, the equal access to it remains questionable. Therefore, the authors visited Sri Lanka in April 2018 for four weeks in order to learn about the country, its culture and society as well as to conduct interviews and do the field observation on-site.

3.2 Data creation and collection

This chapter provides a more detailed description of the research methods that were chosen for this study and how primary data was created and collected through semi-structured interviews (see section 4.2.1), key informant interviews (semi-structured and unstructured) as well as by means of one field observation in Sri Lanka (see section 4.2.2).

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews

Being in Sri Lanka for four weeks in April 2018 enabled the authors to find relevant interview partners. The interview target group was beforehand decided to comprise of female and male students (in the analysis abbreviated with ‘F-S’ for female students and ‘M-S’ for male students) and former students (referring to students that finished school within the last 10 years; in the analysis abbreviated with ‘F-FS’ for female former students and ‘M-FS’ for male former students) of Sri Lankan high schools (see definition of high school in section 1.1.2). Because of the fact that previous studies point out “a clear trend of decreasing levels of activity as girls get older, and a widening disparity between girls’ and boys’ physical activity behaviors” (Bailey et al., 2005, p. 3) especially in secondary schools, the chosen focus seems reasonable for the purpose of this study.

The procedure of selecting the interview partners was done with the help of hostel owners, other travelers or others that knew students or former students and could help making contacts. Furthermore, the contact to three further researchers based in Sri Lanka helped to connect with a big network of sustainable hostel, hotel and lodges owners whose contacts to local communities was beneficial for the interviewee selection process. During the course of the study, 15 semi-structured interviews with both male and female students as well as former students of different Sri Lankan high schools were conducted. The reason for choosing male as well as female students was to explore both sides of perceptions and

16 experiences regarding the topic of female empowerment and gender inequality in PE classes. Students from public as well as private schools were chosen to gather insights about whether the influence of international curriculums and teachers has an influence on the students’ experiences in PE classes or not. In order to assess differences between PE in gender separated and gender mixed schools, students from both kinds of schools were interviewed.

The structure of the semi-structured interviews was as follows: after explaining the purpose of the interview, questions regarding the interviewees’ personal details (gender, age, nationality, etc.) followed. Afterwards, the interview design continued with more detailed and open questions to get a deeper view into the participants’ opinions. According to Bryman and Bell (2013), this type of structure offers the possibility of developing questions along the interview process and relate to the answer given by the interviewee. Questions are open-ended, which lead the option of creating dialogue and extended answers. Regarding the interview structure and content, questions about the availability, amount, and variety of PE classes at school and the PE class climate were asked. Then, a variety of questions followed that enable to explore the exploration of the students’ perception of the role of teacher, parents and society on the access and quality of PE classes as well as the teachers, parents, societies and students’ attitude towards the opposite gender. Questions to better understand the child’s motivation and opinion towards PA followed. Also, questions regarding the interviewees’ own feeling of empowerment as well as her or his opinion on the importance of sport for girls offered relevant insights. Lastly, the interviewee had the chance to fictionally propose to the Sri Lankan government three things that in her or his opinion are necessary to be changed in the Sri Lankan school system (for more details about the interview outline see Appendix).

The following table gives an overview of the interviewees that were chosen to form the data basis of this qualitative research study in order to explore the perceptions of students in Sri Lanka on the topic of female empowerment through PE.

Table 1: Overview of semi-structured interviews

INTERVIEWS INTERVIEWEE TYPE OF SCHOOL

DATE LOCATION IN SRI LANKA F-S = Female student M-S = Male student F-FS = Female former student M-FS = Male former student

AGE SCHOOL NAME BOYS

ONLY GIRLS ONLY GENDER MIXED (PUBLIC) GENDER MIXED (PRIVATE) 10.04. 2018

Weligama M-S1 12 Brilliant Stars

Internatinal College, Matara x 11.04. 2018 Weligama M-S2 19 D.S. Senanayake College, Colombo x 14.04. 2018

Weligama M-S3 20 Carey Collage,

Colombo

17

14.04 2018

Weligama M-FS4 24 Mahinda Collage,

Galle

x

14.04. 2018

Weligama M-FS5 28 Rahula College,

Matara

x 15.04.

2018

Weligama F-FS6 29 Weligama Girls

School, Weligama x 15.04 2018 Hiriketiya F-FS7 21 Governmental School, Kandy International School, Colombo x x 15.04. 2018

Hiriketiya F-FS8 30 Girls School,

Tangalle

x 15.04.

2018

Hiriketiya M-FS9 24 Mixed School,

Tangalle x 17.04. 2018 Hiriketiya F-S10 12 Galle International School, Galle x 20.04. 2018

Arugam Bay F-S11 12 Galle

International School, Galle

x

21.04 2018

Arugam Bay M-FS12 23 Singapure

Singaleh School, Arugam Bay

x

25.04. 2018

Ella M-S13 18 St Josaps College,

Bandarawela x 30.04. 2018 Matara F-S14 17 St. Marys Convent, Matara x 30.04. 2018 Matara F-FS15 19 St. Marys Convent, Matara x

3.2.2 Key informant interviews and field observation

Additionally, in order to extend the knowledge about gender inequality, the school system, sport and culture and to gain further insights about significant aspects of the Sri Lankan society, four key informant interviews with in total six interviewees as well as one field observation were carried out. In an interview with a Sri Lankan woman who moved from Sri Lanka to the U.S. at age 23 and now lives in Lund, Sweden, deeper knowledge about the Sri Lankan culture and how the role of women in Sri Lanka differs from that in the U.S. and Sweden could be added to this research. The interview with a Danish woman who spent 6,5 weeks in Sri Lanka in 2017 to do a project based on SDG 5 (gender inequality) helped to understand the urgent need for initiatives and actions that boost female empowerment in Sri Lanka. Apart from the students’ perspective, talking to a female teacher and a female council of high schools in Weligama provided an additional relevant perspective on the topic of female empowerment through PE. Finally, meeting a couple from the U.S. who moved with their children to Arugam Bay, Sri Lanka, in 2011, was very insightful as both of them work for ´Surfing the Nations´. This NGO is based in Hawaii and aims at strengthen local and

18 international communities through the sport of surfing and swim lessons to promote social change (Surfing the Nations, 2018). Apart from conducting the interview, joining one of the Surfing the Nations’ swim and surf lessons in Arugam Bay was an opportunity to do a field observation to collect information of the behavior of Sri Lankan children in a safe surrounding where female and male children were all doing sports together. This field observation then was used as additional information and to better understand the students’ comments on their perception of a safe environment and their relations among peers. By watching the children interacting with each other – especially with the opposite sex –, connections to the benefits of PA could be made and used for the analysis of the data.

The following table gives an additional overview of the conducted key informant interviews and the field observation.

Table 2: Overview of the key informant interviews and the field observation

INTERVIEW DESCRIPTION

DATE LOCATION KI = Key Informant

FO = Field Observation 28. March

2018

Sweden, Lund KI1 Sri Lankan women who moved from to the U.S. at age 23 and

now lives in Lund, Sweden 02. April

2018

Denmark, Copenhagen

KI2 Danish women who did a 6,5 weeks project about SDG 5

(gender inequality) in Sri Lanka in 2017 14. April

2018

Sri Lanka, Midigama

KI3 Teacher and school principal of gender mixed schools in

Weligama, Sri Lanka 20. April

2018

Sri Lanka, Arugam Bay

KI4 U.S. couple who moved to Arugam Bay in 2011 and are

working for Surfing the Nations (NGO to strengthen local and international communities through physical activities) 21. April

2018

Sri Lanka, Arugam Bay

FO Taking part in a 2h swim and surf lesson organized by the NGO

‘Surfing the Nations’ in Arugam Bay, Sri Lanka

3.3 Data coding, organizing and analysis

The content analysis technique was chosen to analyze the primary data. This technique can be used to organize the data based on categories, which will be helpful when looking at different aspects of empowerment (Silverman, 2014). Part of the content analysis technique is to code and organize the data in order to decide whether the gathered information can be categorized in groups to make it more accessible and easier for the analysis and in the end to use the data in the most convenient way for answering the research questions (6 & Bellamy, 2012).

Based on the content analysis technique, the process of analyzing the data in this research paper is divided into three main phases. First, after conducting all interviews, the authors listened to the interview recordings in order to gain reliable transcripts. Moreover, the material was coded by highlighting important words and sentences as well as writing down

19 notes to collect the most relevant information. Second, after finishing the first process of scanning the material, different categories are identified and put into specific groups which are then linked to each other. Despite having determined categories, additional information that cannot be categorized was studied to complete the analysis (Silverman, 2014). The categories will be linked to the conceptual framework and mostly focus on the main issues of PE, female empowerment, and access to sports. For instance, the process of coding centers upon keywords related to the 3DMWE and therefore includes attributes and criteria which are connected to the personal, relational and societal level of empowerment. At the same time, the categories are connected to the EST.

This categorization process is based on the structure and idea behind the conceptual framework and closely ties to the theory in order to start positioning the gathered insights in the theoretical background of this research paper. Finally, in order to go from the concrete material to broader themes and patterns, linkages between the identified categories are created to find contradictions and implicit assumptions. Thereby, the conceptual framework is helpful to understand, describe and analyze the data in order to elaborate detailed answers to the research questions.

3.4 Research reliability, validity and limitations

3.4.1 Reliability and validity

Research deals with reliability and validity. The question whether the method and findings of the study are replicable and future researchers will achieve the same results and interpretations, is in the discourse of reliability (Silverman, 2015). The conducted interviews therefore address the topic of reliability by having specific patterns to compare the participant’s answers within a transparent research process. Theoretical transparency is further given through empirical literature and a theoretical framework as base for the interpretation and data analysis (ibid).

When it comes to validity, the extent to which other researchers can make use of the study is to be considered. First, construct validity includes the formulation of structured interview questions in order to clarify the topic of investigation and to be able to interpret the students’ perceptions. Second, conclusion validity means the extent to which the data supports statements which are made based on analyzed patterns. It is not reasonable to draw a general conclusion from just one individual interviewee’s answer (6 & Bellamy, 2012). Rather there is a legitimated theoretical framework to ground the data into theory and to make inferences in order to generate useful knowledge.

3.4.2 Limitations

Due to the timeframe and scope of this study, this research paper entails different limitations. As the study only focuses on high schools which are all situated in the southern, eastern,

20 western or central part of Sri Lanka, the geographical limitation is acknowledged. Within the limited time for conducting interviews, a further investigation of the northern part and more rural areas was not feasible, as the places of the interviews mostly represent areas that are tourist destinations. The following map shows the locations of the high schools this study is focusing on.

Figure 4: Investigated high schools in Sri Lanka

Besides this geographical limitation, another critique of this study approach is that there can be no generalization of findings as there were only a limited number of in total 15 interviewees from in total 14 different schools. Due to the age of the interviewees, some were not able to give elaborate answers but tended to keep them short and easy. Also the interview questions had to be designed in a way that the children and young adults were able to understand them. Another limitation in the course of data gathering involves the issue that the authors were not able to speak the interviewees’ mother languages, namely Tamil and Sinhalese. Even though English is part of most Sri Lankan School curriculums, the ability to speak English was only common with females and males that work in the tourism sector and have to speak English on a daily basis. Hence, the authors had to carefully select the interviewees based on their English skills in order to receive adequate interview answers. Therefore, the interviewees represent one target group of students and former students that have the chance to visit a school and live in an environment where English skills are used and promoted. This limitation is another reason why the study results cannot be generalized on whole Sri Lanka.

21

3.5 Ethical Consideration

As Silverman (2015) describes, there are three parts of ethics which have to be considered: Codes and consent, confidentiality and trust. Looking at this study, it is a natural right for all of the participants to know about the nature of the research and about the fact that they are interviewed in order to investigate the research questions. This could be problematic in some case when it comes to certain bias. Knowing about the research purpose might lead to falsified answers regarding the perception of female empowerment or access to sports. As there was sometimes a risk of being observed from their family members, interviewees may have answered less truthfully, and therefore false data could cause wrong conclusions about the student’s perspective. It is also important to question whether all participants understood the purpose and aim of the study correctly. Not only because of the language limitations (see section 3.4.3), but also due to the fact that children at a young age and with another cultural background may not be aware of being researched. Therefore the authors tried to explain the research purpose as clearly as possible.

Furthermore, the way how the interviews were conducted is not quite common in doing research. Instead of asking for parent’s permission or setting up an official agreement, the authors just started talking to the children they met for example at the beach. Although this approach and way of getting data was actively chosen and part of the research process, it has to be considered that another research topic might have been critical for collecting the data this way. When reflecting about the role of the researchers, some facts have to be mentioned: the authors both are female, coming from a Western country and have proper English skills. This might affect the interview process and the relation between interviewer and interviewee. Because the Sri Lankan children have another cultural background, a different level of language skills and an age difference, they might feel some limitations during the interview or even feel cowed. In this context the authors are also aware of being an active part of the study since they are always observing their surroundings, and perceive the country through their own experiences on site, which then in turn might affect the analysis part.

Confidentiality includes the protection of the participant’s identity. To ensure the right for anonymity, the conducted interviews were executed without publishing the participant’s full name. In addition, before using any information for research, the authors had to make sure that each participant agrees on doing so (Brown, 2006). In terms of trust, the research process aimed at creating a feeling of security and trust among the researches and the interviewed people, also to avoid the risk of having a negative attitude towards researchers in the future (Silverman, 2015). To not harm society, the research was conducted appropriate to legal and social norms of Sri Lankan and with respect to culture.

22

4. Findings

The findings part is structured into three sections with according key themes (see figure 5), to illustrate different key aspects of empowerment as it relates to the students’ perceptions. First, the analysis will start in the center of the conceptual framework and concentrates on the exosystem. This system does not have a direct but indirect impact on the child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The purpose is to explore the current situation whether Sri Lankan high schools provide gender equal access to PE classes in order to lay the foundational information that is necessary to answer the following two research questions. After exploring the role of the exosystem, the analysis will continue with the meso- and microsystem, examining the students’ perceptions of the PE class climate. After exploring the micro-, meso- and exosystem of the EST, the analysis will continue with the three dimensions of female empowerment as proposed by the 3DMWE. Therefore, the students’ perceptions will be explored to help understand and analyze how PE is contributing to each of the three dimensions. Furthermore, all three of the aforementioned focal points (exosystem; micro- & mesosystem; 3DMWE) are embedded in the macrosystem of the EST. Throughout all analysis parts, the influence of the macrosystem and particularly the culture of Sri Lanka will be considered and its influence on all systems and empowerment dimensions will be taken into account. The analysis will conclude by bringing together all of the investigated themes in order to in the end provide an overall picture of the findings.

23

4.1 Availability and access to PE

Figure 6: Exosystem

The way that a school system and its curriculums are structured belongs to the exosystem of the EST, because a school’s regulations and structures do not have a direct but indirect impact on girls’ empowerment. Based on the findings of the 15 interviews with Sri Lankan high school (former) students, there are discrepancies between the different kinds of schools that exist in Sri Lanka. The schools that the interviewees attended range from public boys-only, girls-only and gender-mixed schools to private gender-mixed schools.

4.1.1 Availability of PE

The foundation for female empowerment through PE is the availability of PE in Sri Lankan high schools. The analysis shows that independent of the kind and location of the schools, a wide variety of sport disciplines are offered by Sri Lankan high schools throughout the school week. The offer ranges from general PT (Physical Training) to basketball, karate, cricket, volleyball, netball, running, swimming, high-jump, low-jump, football and many more. F-S10, who was born in Byron Bay, Australia, and moved to Sri Lanka in 2017 with her family, said that compared to her Australian school, the Sri Lankan international mixed school offers even more PE than her former school (F-S10, personal communication). The availability of PE does not depend on the kind of school, but on the facilities, the available teachers and money that the school possesses. M-FS4 mentioned that “in [her] school, so many kinds of sports were available but in rural areas it is not like that” (M-FS4, personal communication). While most sport disciplines do not require many facilities, swim lessons are only offered by a few schools that have their own swimming pool or have access to a public pool. Also, M-S3 (personal communication) stated that in his boys-school, swim lessons were offered but the