Trust in influencer marketing

A qualitative study on audience reception of Royal Design advertising

Nette Leikas & Kamila Szkwarek

Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries Master’s programme

One-year master thesis | 15 credits Submitted: VT 2020

Supervisor: Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt Examiner: Temi Odumosu

Abstract

The aim of this thesis is to investigate whether there is a trust between social media influencers and their followers, and if so, to what extent. The methodological approach consists of an analysis of interview material, expert interviews and selected comment boxes on social media. By conducting qualitative analysis, this thesis examines audience reception to promotional content produced by social media influencers in collaboration with the Swedish interior design brand Royal Design. Based on the theories of parasocial interaction, two-step flow and opinion leadership, and modes of reception, concepts such as audience advertising response, relationship to influencers and the level of trust are investigated and concluded in order to find common patterns around audience reception to influencer marketing. The analysis shows that there is indeed a certain amount of trust towards social media influencers among the sample group especially if they recognise the influencer, however, the trust is not full and unconditional. The audience reception of influencer

marketing content both in the interviews and comment boxes was mostly positive, and some respondents seemed to have developed sympathy towards social media personas featured in the advertisements, praising them for being personal and authentic. The results of the study imply that while the credibility and motives of influencer content are questioned by some, it is generally perceived as a more enjoyable alternative to traditional advertising formats.

Keywords: influencer marketing, trust, qualitative interviews, audience studies, audience reception

Table of Contents

Abstract 2

Table of Contents 3

List of Figures and Tables 4

1. Introduction 5

1.1. Research questions 7

2. Background 7

2.1. Social media use 7

2.2. Social media influencers 9

2.3. Interior design and Royal Design 13

3. Previous research 14

3.1. Influencer marketing 14

3.2. Audience studies 16

4. Theoretical framework 18

4.1. The concept of trust 19

4.2. Parasocial interaction 20

4.3. Two-step flow and opinion leaders 21

4.3.1. Word-of-mouth marketing (WoM) 24

4.4. Modes of reception 25

5. Methodology 27

5.1. Data collection method: Qualitative interviews 28

5.1.1. Strengths and weaknesses of the method 30

5.2. Audience interviews 31

5.3. Expert interviews 33

5.4. Advertisement examples used in audience interviews 34

5.5. Content analysis 39

5.6. Data analysis method: Qualitative analysis 44

6. Ethics 45

7. Results and analysis 47

7.1. Influencer marketing 48

7.2. Audience studies and social media use 50

7.3. Parasocial interaction 53 7.4. Two-step flow 57 7.5. Modes of reception 62 7.5.1. Transparent mode 63 7.5.2. Referential mode 65 7.5.3. Mediated mode 66 7.5.4. Discursive mode 68 7.6. Discussion 69 7.7. Limitations 72 8. Conclusion 74 9. References 76

10. Appendix 84

10.1. Interview guides 84

10.2. Code: Themes around using social media 89

10.3. Code: Social media platforms use 89

10.4. Code: Parasocial interaction 90

10.5. Code: Modes of reception 94

10.6. Code: Two-step flow 94

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1. Attitudes of influencer marketing audiences towards social media influencers

worldwide as of February 2018, by age group………..….13

Figure 2. Advertisement 1……….….….36 Figure 3. Advertisement 1………...……..…..37 Figure 4. Advertisement 2……….…..38 Figure 5. Advertisement 2……….……..39 Figure 6. Advertisement 3……….…..39 Figure 7. Advertisement 3……….…..40 Figure 8. Advertisement 4………...43 Figure 9. Advertisement 5………...44 Figure 10. Advertisement 6……….45

Figure 11. The comment box of Advertisement 5………...53

Figure 12. The comment box of Advertisement 5………...64

Table 1. A graphic of Michelle’s (2007) modes of reception………..27

1. Introduction

The ubiquity of social media in the contemporary world can not be overlooked. Platforms such as Instagram, YouTube and Facebook play an important part in many people’s everyday lives and serve as sources of entertainment, information and inspiration. Among a countless number of accounts and profiles, media users choose which content they want to view and whom they want to follow on social media and get updated on their posts and online activity. Those who gather a certain number of followers, by sharing their lifestyle, buying choices, preferences and recommendations, can influence the audience and evoke a desire in them to own the same products, look a certain way, or behave in a similar manner. These persuasive possibilities of social media influencers can be used by retailers as a marketing strategy both to build brand awareness and to generate sales. The influencer marketing approach is based on the concept of trust between consumers and influencers, who collaborate with brands to gain a financial benefit.

With our study, we aim to investigate whether there is indeed a trust between followers and influencers, and if so, to what extent and on what conditions. We consider this a timely and valid problem in relation to society as a whole, with the increasing importance of media in people’s everyday lives. The exposure to a great amount of advertising and promotional content challenges the concept of trust and credibility in the media sphere, and we suggest that their meanings and conditions should be reconsidered. Therefore, in order to gather insights into trust levels among social media users, we will study relationships between influencers and their audiences, and the audience reception of influencer marketing. This will be done by conducting a series of interviews with social media audience who are exposed to influencer advertisements, as well as with representatives from a company, which utilises influencer marketing in their strategy. For this purpose, we have chosen the company Royal Design, which specialises in interior design and furniture. Royal Design actively promotes their products through various popular Instagram profiles, blogs and YouTube accounts, which led us to the conclusion that they utilise influencer marketing on a big scale, with a prominent focus on digital media channels. As our study is geographically limited to Sweden,

it was crucial that the selected brand has a strong presence in the Nordics. Sweden is Royal Design’s main market and thus, the company fits in the picture. Lastly, their area of speciality is interior design, a topic that is a common interest among many age groups, which will provide wide possibilities for audience study.

Our paper begins with an introduction of relevant subjects like interior design and social media. Also, Royal Design will be presented more in detail there. Then, we will continue with an overview of previous literature about influencer marketing and audience studies and the theoretical framework. The latter consists of the concept of trust, a modern version of the classic theory of two-step flow and opinion leadership, parasocial interaction and a framework for audience reception. The theories presented here will also be important contributors to our analysis later. In the following chapters, we will introduce our methodological approach followed by ethical considerations around the method and the paper. The study’s main method is qualitative interviews supported by a content analysis of comment boxes referring to influencer marketing content. In this section, we will also provide an overview of the advertisement material used in this study and how the collected material is analysed. An analysis based on the above-mentioned theories and concepts follows

hereinafter where we will present our findings from the data collected during the study. Lastly, we finish the study by discussing our conclusions on the subject.

1.1.

Research questions

The study aims to understand the audience reception of interior design advertising by social media influencers and to what extent trust plays a role in the process, as well as how

marketing professionals at Royal Design perceive the relationship between influencers and followers. This will be approached with research questions below linked to theories and concepts of parasocial interaction, two-step flow and opinion leadership, and modes of reception.

Based on the theories of parasocial interaction, two-step flow and modes of reception... 1. ...For what reasons and to what extent do audiences trust social media influencers and

their advertisements?

2. ...How does the audience receive Royal Design’s influencer marketing advertisements?

2.

Background

2.1.

Social media use

Over the past few years, social media has been growing in popularity (Van Dijck & Poell, 2013). As of 2020, Alexa, an Amazon company tracking web traffic, ranked YouTube and Facebook among the top 5 most visited websites on the Internet (Alexa Top 500 Global Sites, 2009). Examples of other well-known platforms are Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter and TikTok (Omar & Dequan, 2020; Kane et al., 2014). The various services and mobile apps offer great possibilities of social interaction, sharing ideas and finding information. They are easily accessible, often free of charge, and can be used by people in all age groups, provided they have a device connected to the Internet.

According to Fuchs (2017), what various social media platforms have in common is

communication, information, collaboration and community. For example, Instagram allows users to post content and comment on other users’ pictures, which is both information sharing and communication. It is also possible to follow specific interest topics through hashtags and get a sense of community with other like-minded users. Collaboration is possible due to the interactive aspect of Instagram Stories, 15-seconds posts available only for 24 hours. While viewing the post, an Instagram user can react to other users’ content by taking part in a poll, quiz or asking questions (Interactivity in Instagram Stories Ads: Reach Audiences with Polling Stickers, 2020).

Sweden has a particularly high number of Internet users, many of whom visit social media platforms on a daily basis. The Internet penetration rate in Swedish households has passed 98%, and 95% of the population claim to use the Internet (The Swedes and the Internet 2018 - Summary). According to Internetstiftelsen, 100% of Swedes under the age of 26 watches YouTube, almost all students who search for information use Google, and nearly every parent staying home with their offsprings shops online (ibid.). Social interactions often occur

through platforms like Messenger or WhatsApp, instead of a face-to-face meeting. Some platforms, for example, Instagram, are growing in popularity, while others, such as Facebook, see a decrease in the number of users over time.

2.2.

Social media influencers

Social media platforms are often utilised in marketing as a customer attribution and brand awareness tool (Evans, 2013). Nowadays, an online presence or lack thereof can significantly impact a company’s sales, position, and sometimes even survival on the market (Kietzmann et al., 2011). While e-mail and instant messaging started to develop already during the 70s and 80s (Korenich et al., 2013; Sodeman & Gibson, 2015), it was not until the 90s that companies started to utilise media on a larger scale as a marketing channel (The evolution of social media advertising, 2017). Over the years, the technological developments made it possible for marketers to place banners, videos and other promotional content on various websites on the Internet. In 2014, Facebook Business Manager was launched, making social media advertising easier and more accessible (Facebook’s Secret New “Business Manager” Could Compete With Developer Partners For Marketing Dollars). Many companies nowadays utilise social media channels, incorporating them in the overall marketing strategy. The benefits of an Internet presence for companies include, among others, building a brand image, generating leads and creating a brand affinity with customers (Palonka & Porebska-Miac, 2013). Some brands that acknowledge the potential of this channel collaborate with so-called “influencers” on social media to reach their marketing goals.

The concept of influencers is relatively new, but it has in a short time gathered a lot of attention both in general discussion and in academic research. However, we could suggest that influencers have existed through times. In the early 2000s, blogs started emerging on the internet. Their popularity was based on the curious public that followed the lives of ordinary people (Hörnfeldt, 2018: 9). During this century, the word “influencer” emerged but people with public influence have been present long before. In early days, these public figures could be royals or politicians, later on, characters from reality shows followed by today’s

personalities from social media. Indeed, both can be considered as opinion leaders in a context where they impact their followers’ behaviour and attitude (Brown & Hayes, 2008). We discuss the public presence of popular faces on the streets, in magazines and now also online. Hörnfeldt (2018: 10) explains our habit to follow influencers as the nature of humans - we have a strong interest in others around us. Human curiosity is proposed to be the driving force of our learning and development. Thus, we seek information from others and get ideas on how to develop our habits. Another motive to follow other people is our desire to feel belonging (Hartung & Renner, 2013). Influencer content is easily accessible any time of the day wherever we reside, so consuming the content can be an easy way to learn and ease the feeling of loneliness for a follower.

It has been suggested that the emergence of user-generated content has democratised opinion leadership. In the Swedish context, as access to the Internet among Swedes is high, anyone can create a free social media account and start sharing their opinions to a wider public. Levin (2019: 13) suggests that creativity of the account holder is the key, and no capital or previous knowledge is required to gain the attention from other social media users. Therefore, these days, we have the opportunity to become influencers by creating unique content despite our backgrounds.

Even though influencers have a long history, we will focus on the current definition of the concept that we see is a content creator with a big number of followers, often in several social media channels that can have an influence on his/her followers’ decisions. These persons have built a credible brand and even a business of their personality and everyday lives. Their

influence is based on the relationship that is built with their loyal followers (Hörnfeldt, 2018) as well as on their attractive personal qualities or great networking skills (Bakshy et al., 2011). Besides, the influence can be of different strength depending on the channel, person and storytelling (ibid.: 2). As recently as in 2016, a common understanding of influencers as an occupational group was missing both among companies and the public (Hörnfeldt, 2018: 4). But today influencers have become an important part of many companies’ marketing strategy, and they can be seen as a gateway to a larger public. Of course, this type of a strong trust relationship between an influencer and audience can be questioned. For example, the company’s brand image or the influencers’ behaviour and opinions in other contexts might play a crucial role in trusting in influencer marketing. Indeed, our paper aims to study further the trust relationship and if it really is as deep as sometimes believed.

Indeed, not every influencer is trusted and creates successful sales results or brand awareness. Brown and Hayes (2008) suggest four criteria for the effectiveness of influence. Market reach has to do with the size of the audience, frequency of impact about the likelihood to be heard, quality of impact is based on trustworthiness and closeness to decision on timing and

proximity to the decision-maker. Many future influencers start as ordinary social media users and adjust their strategy along the way. The path to becoming a successful influencer is intricate, and includes gaining an increase in reach, number of followers and building a user community (Virkkunen, P. & Norhio, E., 2019). An effective strategy to achieve this kind of growth can be self-branding (ibid.). It is important to note that the influencing process can occur on various platforms simultaneously, and some influencers make a name for themselves by creating an own brand, hosting television programs, designing one’s own clothing line, or collaborating with various companies on the market and promoting their products online. However, if one wants to monetise on their social media profiles, a key factor for succeeding is understanding the social media landscape and knowledge about influencer marketing (Visual Amplifiers, 2018). Studies show that becoming an influencer is a long-term process, which requires commitment and continuous work on one’s social media profiles, while ensuring interest and engagement from the audience’s side.

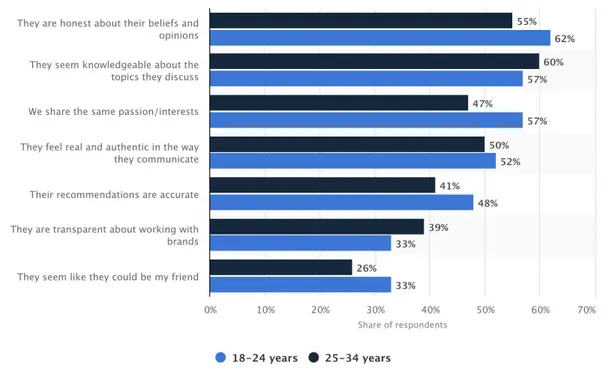

A recent consumer study published by Guttmann (Consumer views on influencers 2018, 2019) discusses attitudes towards influencer marketing worldwide among age groups 18-34 (Figure 1.). The survey was conducted in February 2018 and is based on answers from 1,200 respondents who viewed and interacted with content produced by influencers.

Figure 1. Attitudes of influencer marketing audiences towards social media influencers worldwide as of February 2018, by age group (Consumer views on influencers 2018, 2019).

It reveals that over half of the respondents believe in the honesty and authenticity of social media influencers, and perceive them as knowledgeable about the subjects they raise.

Additionally, there is a strong belief that influencers’ recommendations are accurate and that the way they communicate with followers feels real and genuine. However, the share of respondents who believe that influencers are transparent about working with brands is fairly low, which may be a factor that has a negative impact on their credibility. It is going to be of interest to investigate whether our respondents have similar attitudes towards Royal Design’s influencer marketing advertisements.

Despite the positive effects on companies’ sales results, influencers have also received critique of the messages they mediate, especially to the younger audience. It has been

recognised that the younger adopt attitudes and behaviour from social media more easily than the older generation (PBS, 2019). For example, YouTube is a popular platform among

teenagers who believe in and absorb ideas from videos to a great extent (Levin, 2019). This might occur even when harmful or adverse ideas are spread in social media. For instance, Saboia et al. (2018) have highlighted social media’s impacts on triggering eating disorders and distorted body images. Images on Instagram might be photographed from angles that give an unnatural impression of a female body, and blogs share unhealthy diet proposals that the audience adopts.

2.3.

Interior design and Royal Design

Interior design is a common interest among people in all age groups. Planning a room layout, renovating old furniture or doing an apartment makeover can be considered a popular pastime of many. People appear to enjoy being surrounded by beautiful objects and spend time in tastefully decorated spaces (Psychology of Design: How Interior Decor Changes Your Mood, 2019). Studies suggest that furnishing, decor and the choice of colours can influence our mood and have an impact on our emotions (Yildirim et al., 2007). Noticing a positive effect after changing a room’s furnishing might be one of the reasons for having an interest in interior design.

In Sweden, interest in interior design has been rising in the past years. Decorating a home is seen as a dear project that grows on the way and is worth investing in. Even popular Swedish stores, like H&M, have widened their assortment from fashion to home interior (Ängsliga svenskar vårdar sina hem, 2014). Neither should we forget that one of the most popular home interior stores, IKEA, comes from Sweden and has become one of the flagships of the

country. Indeed, there are many competitors in the Swedish interior industry like Jotex, Granit, and Royal Design that our study focuses on.

In this section, we want to give a brief introduction of Royal Design, which influencer marketing activities are used as a supporting element in our analysis of customer attitudes. According to Royaldesign.se, the company that was founded in 1999 in Kalmar, Sweden has become the largest website in Scandinavia focusing on home decor, design and furniture. The company specialises in Scandinavian design but provides a broad assortment of other home products. As they started as an online store, still today their focus lies on online services, and they see the physical stores as an inspirational complement to the online experience. Royal Design calls this approach as e-tail, a combination of online and offline retail (Om oss - RoyalDesign.se). The store aims to provide high-quality design products for all customers with affordable prices and a large variety of products (About us | RoyalDesign.co.uk). This means that they target a wide audience, and they mean that Royal Design could decorate every home (Företagsinformation - läs mer om RoyalDesign).

When it comes to social media, Royal Design has active, inspirational accounts on various channels, and they even encourage their customers to share their purchases on Instagram with the hashtag #yesroyaldesign. Additionally, influencer collaborations are present both on Royal Design’s website as landing pages and their own social media channels where they often repost interior design content from influencers’ social media accounts. However, Royal Design has faced criticism in their influencer marketing approach. Bloggbevakning, a critical Swedish blogger that points out controversialities in social media and especially influencers, has kept Royal Design’s collaborations under surveillance. Both their customer service and quality of the products have been criticised and questioned after an influencer has praised the company (Royal Design lägger locket på efter influencers kampanjer, 2019).

Due to Royal Design’s strong digital presence and target groups, we considered the company as an excellent example in studying audience reception and influencer marketing. Their frequent collaborations with Swedish influencers together with the common interest in interior design in Sweden makes it interesting to see what role trust has in the audience attitudes while being exposed to Royal Design’s advertising.

3.

Previous research

3.1.

Influencer marketing

A concept central to our study is influencer marketing. Despite being a relatively new field, there is a substantial number of researchers who have previously taken an interest in the topic. Over 10 years ago, Brown and Hayes (2008: 3) came forth with a statement that traditional marketing is “broken”, since it no longer served its ultimate goal - generating sales. The authors blamed marketing for being abrupt and insensitive to people’s needs, demanding attention without engaging with viewers or listeners. According to them, the core of the problem was as follows: “(...) your prospects don’t believe you. You’re selling something, which means you’re biased. Prospects may like your message but they want to hear it from someone they trust” (ibid.: 5). They suggest that consumers’ trust in service and product providers is in constant decrease because of the assumption of companies favouring their own agendas (ibid.: 70). Furthermore, they mean that traditional advertisements are more easily ignored than a recommendation from a familiar face (ibid.: 73).

The emergence of influencer marketing appears to be the innovation that Brown and Hayes (2008) were longing for. Today, a technique common in the 1980s and 1990s, word-of-mouth marketing (also introduced in chapter 4.2.1. of the study), is being utilised by many brands in their influencer collaborations, and the concepts crucial to its success include, among others, credibility and source attractiveness (Lim et al., 2017). Online platforms have created new possibilities of persuasion to achieve marketing goals. The strategic use of language was researched already by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (Hogan, 2012). Many centuries later, it started to evolve in various fields, and within marketing, a concept called marketing rhetoric emerged (Miles & Nilsson, 2018). It includes strategies for successful persuasive communication with consumers, which successively make the audience agree with the role model on a particular matter (Miles & Nilsson, 2018; Ge & Gretzel, 2018).

Influencers can utilise this in a variety of ways; for instance by emphasising their proficiency or expertise, referring to the followers’ system of values, or evoking certain feelings, for example of need and desire. Apart from that, social media and online messaging offer

additional, non-verbal means of communication, emojis (Ge & Gretzel, 2018). They are considered to convey a meaning that can add new value to a text, and therefore, reinforce the persuasive process initiated by a brand.

According to Glucksman (2017), the reason why companies have taken an interest in

collaborating with social media influencers is the perspective of raising brand awareness and building a brand image. In such a context, influencers “truly serve as the ultimate connection between a brand and a consumer” (ibid.: 78). However, Brown & Fiorella (2013) claim that the term “influence” tends to be oversimplified in the contemporary world. With influencer marketing, the direct communication between a brand and a consumer is disrupted, and the vast number of social media accounts and abundance of data challenge trust for influencers. Awareness is rising among consumers about the functioning of influencer marketing; they start to recognise that the content of influencers’ sponsored posts is often carefully designed by a brand to communicate a certain promotion or brand image (Kadekova & Holienčinová, 2018). The use of social media influencers for these purposes becomes subject to criticism, and the credibility of celebrity endorsers is questioned (ibid.). It has been proved that the success of an advertising message is dependent not only on the influencer’s number of followers but also their likability and popularity (De Veirman et. al, 2017), which may make it challenging for advertisers to choose the right influencers to partner with.

3.2.

Audience studies

As we will analyse influencer marketing reception in this paper, our work is firmly rooted in audience studies. Numerous studies reveal that the understanding and nature of the audience have changed over the years (Livingstone & Das, 2013; Livingstone, 2015, Martínez-Costa & Prata, 2017). Once, watching scheduled television programs while sitting on the sofa, often with the whole family, was a popular pastime among children and adults (Livingstone & Das, 2013). In today’s world, people rather spend time staring at their phone or computer screens in solitude, chatting with friends on social media, networking, downloading content from the Internet and playing online games, often multi-tasking (ibid.). The one-way communication

between media and its users was replaced by multiway communication, and together with the emergence of new communication and entertainment platforms changed their audiences. The accessibility of Instagram, YouTube and Facebook creates unprecedented possibilities of generating ideas, giving feedback and sharing content for media users (Woo, 2008). Users continue to utilise social media platforms to not only view, but also to modify, discuss, and even create their own content (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Therefore, Livingstone & Das (2013) question the relevance of the term “audience” and suggest some possible substitutes, such as “the people formerly known as the audience” or “the citizen-consumer” (ibid.: 9). These new terms refer to audiences that actively participate in the creation of the media sphere, instead of just passively consuming content. The creative possibilities that come with the ubiquity of social media have allowed some to build their online presence and make a name for

themselves, and others to follow, and to some extent participate, in influencers’ everyday lives on various platforms.

Audience reception, which will be discussed later in this paper, is an interesting subject to study, not only from a researchers’ perspective but also as part of the overall marketing strategy. Some studies suggest that through analysing audience response to advertising, we can get interesting insights into the effectiveness of an advertising message (Rahman, 2018). The term advertising response can be defined as the prompt, initial reaction experienced by receivers upon interaction with an advertisement (Zinkhan & Martin, 1983). It is a way to evaluate audience attitudes towards an advertisement. The authors suggest that a positive advertisement reception can contribute to developing a fondness for a product or brand, and therefore serve as an effective marketing strategy for building brand awareness. On the other hand, it is implied that any promotional content that insults a potential customer could build a negative attitude towards the advertised product, and even have a damaging effect on the brand’s image (Bartos, 1981).

In terms of advertising, the target group of consumers is not the only audience that will be exposed to advertisements. Gilly & Wolfinbarger (1998) claim that marketers might underestimate the importance of the so-called internal or second audience, which is their

employees, who are also influenced by the marketing content they produce. LinkedIn, a social networking site for professionals, noted that while only 3% of employees share content about their company online, those posts bring a 30% rise in engagement with the company’s

website (The Official Guide to Employee Advocacy How to Maximize Reach and

Engagement by Empowering Employees to Share Content). This illustrates that the second audience members are networked with other people who might potentially be interested in a service or product which the company provides. The group of the receivers of an

advertisement might, therefore, extend beyond the original target audience, making the path between a brand and consumer even more intricate. It is therefore crucial for brands to ensure that the reception is positive among these groups as well, and Gilly & Wolfinbarger (1998) even recommend sharing the promotional content with all employees before the

advertisements are set live. This can also serve as a way to ensure that no inaccurate details or misinformation will be shared, otherwise, in such a nuanced way of reaching new customers or users, it is easy to become misunderstood.

After reviewing previous literature around influencer marketing and audience studies, we noticed that trust as a significant factor determining the success of an advertising message towards consumers was frequently acknowledged. However, the subject was not greatly discussed in the context of audience studies. Therefore, our approach, reviewing the reception of advertising and the role of trust in it, is interesting to study as we gain knowledge from the audience perspective. By presenting the same examples of content produced by influencers to our sample group we strive to find common patterns in audience reception of influencer advertisements. We believe that our research will contribute to the field of audience studies with new insights, and prompt a discussion on the relationship between influencers and followers, which was not widely discussed before. This research gap has inspired us to conduct our study.

4.

Theoretical framework

In this section, we will introduce the theoretical framework which our study is built on. The crucial theories will be introduced and grounded here, as well as linked to the research questions. The concept of trust, parasocial interaction, two-step flow theory with opinion leaders and word-of-mouth marketing and modes of reception will serve as a firm basis for approaching the subject of trust in influencer marketing, and provide possibilities to analyse the relations between followers and influencers.

4.1.

The concept of trust

The concept of trust has been researched by various disciplines in several contexts, therefore, many diverse definitions have been presented. In this chapter, we define trust in a way that the concept is being utilised in this study.

According to Loureiro et al. (2012), consumers can build emotional relationships with brands similarly as they do with people. As mentioned in section 2.2, influencers can create a brand around their personality, but in the context of Loureiro et al.’s study, a brand can also refer to a company’s characteristics. They mean that trust is a consequence of positive emotions towards a brand, which is comparable to a love relationship between a consumer and a brand. Therefore, like in a relationship between people, confidence in a brand and reliability of a brand are important components in creating this relationship. After building a love

relationship with a brand, a consumer is more likely to recommend it to others and return as a loyal customer (Loureiro et al., 2012). The relationship between a follower and an influencer will be introduced more closely in the next section 4.2.

Lou and Yuan (2019) have suggested four factors that affect the credibility of an information source, for example, a brand or an influencer. These include expertise (influencer’s

knowledge and skills), trustworthiness (audience’s opinion of the influencer’s genuineness), attractiveness (influencer’s physical likeability) and similarities between the audience and an

influencer. Trust can be damaged, for example, when the audience has a sceptical attitude on the underlying motives of an influencer. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2020) divide trust towards a brand between cognitive and affective trust. The first one is similar to Lou and Yuan’s (2019) first factor, expertise. Cognitive trust means that a consumer evaluates a brand’s performance based on its competencies. Affective trust refers to a more emotional reliance on a brand when a consumer feels that a brand cares for him/her (Huang et al., 2020).

Brand awareness is a term that is also closely connected to the level of consumers’ trust. Having previous knowledge of a company or an influencer is suggested to contribute to trusting them and making purchases with them. Here influencers can play a role in spreading awareness of a brand (Lou & Yuan, 2019).

4.2.

Parasocial interaction

The theory of parasocial interaction was first introduced in a paper by Horton and Wohl (1956) and has ever since become firmly established in media and communication studies. The concept defines a relationship that occurs between a spectator and a performer, which resembles a “real” interpersonal relationship (Sokolova & Kefi, 2019). Thus, viewers or listeners can experience a nearly genuine connection, even though it is only one-sided (Daniel et al., 2018). Giles (2002) discusses two similarities between social and parasocial interaction, being companionship and personal identity. The first concept refers to the situation when the other person serves as a companion, for instance, as compensation for loneliness, whereas personal identity can be seen as using the character’s behaviours as a way of understanding one's own behaviours.

Such a relationship can be established between media users and media figures (Giles, 2002). In terms of social media like Instagram, YouTube or Facebook, this connection can be formed by following bloggers and influencers, subscribing to their channels, following their posts online and possibly even creating a community with other followers (Sokolova & Kefi, 2019). To prove this theory, Sokolova and Kefi (2019) argue that YouTube channels that have only one communicator have proved to be more influential and successful with its

message, as opposed to channels with multiple speakers. An explanation could be that in the case of one communicator channels, a parasocial relationship can be formed with the

audience. Influencers, who are able to form a connection with their followers tend to achieve higher effectiveness in terms of persuasion (ibid.).

However, despite the similarities between social and parasocial interaction, it is questionable whether the parasocial interaction can be described as a relationship, considering the

definition mentioned by Giles (2002). At its core lies the future positive outcome of social interaction when a relationship is built, which is different from interaction between strangers. The author claims that a media user is most likely a stranger to the media figure indeed (ibid.), which is in disagreement with the definition of a relationship. We have noticed that the word relationship is often used when describing parasocial interaction (see Giles, 2020; Devereux, E. 2007), however, the actual reference is to a relationship of media users to media personas, rather than with or between them. As a relationship is often both-sided, we could suggest using substitutes for this term that would not entail the mutual aspect, such as

connection, link, affinity or other closely related synonyms, alternatively, providing additional clarification, calling it a one-sided relationship. The ambiguous use of the term parasocial relationship in media studies was also noted by Dibble et al. (2015). The authors paraphrased the concept and called it a one-sided intimacy at a distance. Therefore, to avoid confusion and ensure clarity, perhaps it would be beneficial to consider the usage of a synonym, such as the terms listed above. In case of the relations between influencers and followers, the majority of followers remain strangers to the social media personas and never get the chance to meet in reality. Due to the usually large fan base, they might not be aware of the existence of each particular individual who follows them on social media. The relationship-building occurs thus only on one side, from the follower.

4.3.

Two-step flow and opinion leaders

One of the most common explanations for including influencers in marketing strategies is the credibility they often bring. Lim et al. (2017: 22) argue that information coming from a

trustworthy source influences the beliefs, attitudes and even behaviours of the audience. This requires, of course, a loyal audience, which many influencers with a large number of

followers certainly have. Therefore, we see the theory of two-step flow of communication as beneficial in this study.

Two-step flow of communication including opinion leadership was originally introduced by Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz in the mid-1900s (Katz, 1957). An opinion leader is defined as a group of people who receive information, for example from mass media and then

forward the information to their networks. They are influential and trusted people from whom other people ask for advice, and they are in a frequent discussion with their “audience”, so-called opinion followers (Turcotte et al., 2015: 522-523).

Lazarsfeld and Katz’s hypothesis was based on the idea that information is transmitted from media indirectly to the passive audience through persons referred to as opinion leaders (Katz, 1957: 61). Indeed, their study shows that the audience is not a mass without a connection to one another. Instead, they are a network of individuals that media attempts to reach and through which communication is channelled (ibid.). The study showed that a conversant person in a large, social network had a stronger influence than a direct message from mass media. Therefore, mass media depended on reaching opinion leaders to reinforce and support the message and forward it to the rest of the audience (Hodkinson, 2017: 82). However, it is important to note that this does not necessarily mean that information flows from people with knowledge and interest to those without. Information might only circle within those people who already have enthusiasm on the subject leaving out the people with no interest (Katz, 1957: 64).

Katz and Lazarsfeld (ibid: 63-64) found three underlying justifications for their hypothesis. Firstly, connecting with people occurs more recurrently and has a more powerful effect on influencing decisions and opinions than mass media. Further, opinion leaders who transfer a message to a larger audience had a stronger interest in the subject and they were consuming media more than others. Also, opinion leaders can be found on all levels of society, meaning class, age, occupation, which signals that the opinion leaders might be similar personalities as the ones influenced. Owing to these factors, Hodkinson (2017: 82) explains that “influence

was only possible, then, because it was transmitted via interpersonal contact within trusted social networks”. Turcotte et al. (2015: 523) confirm this by stating that people get more influenced by interpersonal communication. As an example, Turcotte et al.’s study (ibid.) shows that news institutions have decreased in public trust, which has led to a search for credibility through opinion leaders in social media. Similarly, this idea could be adopted in the marketing industry when bigger companies’ advertisements lose their trustworthiness and influencers are used to return and strengthen it. Contrarily, Turcotte et al. (ibid.: 527)

discovered that if information comes from an opinion leader who is regarded as unreliable, also the credibility of the information suffers.

Ever since its proposal, the two-step flow has been largely discussed. Lazarsfeld and Katz created the roots for the theory that can be further adapted in today’s new ways of influence and interaction. Casaló (2018: 3) argues that new technologies and the internet have increased the role of influencers as opinion leaders. For example on Instagram, influencers can act as opinion leaders when they spread trends that their followers accommodate because they trust the influencer’s opinion (ibid.). Influencers usually start as regular social media users creating user-generated content, and after acquiring a bigger audience of strangers, they might even gain the status of a celebrity. Therefore, Martensen et al. (2018: 335) suggest that the nature of traditional opinion leaders has changed. Based on these contemporary studies, we see that Lazarsfeld and Katz’s original idea can be elaborated to today’s digital society and

influencers become a new group of opinion leaders online.

However, the model has also received criticism in the current media environment. According to Bennett and Manheim (2006: 214-215), after the new technological transformation and societal changes, the two-step flow has shifted towards a one-step flow of communication. They mean that communication has become more individualised thanks to the new

technologies, like algorithms, leading the information directly to the targeted individual. Additionally, today’s society is more isolated than before and not networking as greatly as before. Their conclusion is that a talented communicator does not have use for opinion leaders to transmit their messages. Still, they admit that this requires resources and broad knowledge of the target audience (ibid.: 216).

We believe the more contemporary idea of opinion leaders will contribute to our study as influencers affect opinions among many followers. With this concept, we will analyse later in which ways a person communicating between the audience and a company functions and affects the reliability of marketing.

4.3.1.

Word-of-mouth marketing (WoM)

A topic related to mediating messages through people is word-of-mouth marketing. WoM means a situation where a person makes a recommendation facilitating one’s

decision-making. The power of this type of marketing lies in the trust between a sender and a receiver about the sender having researched the subject properly (Silverman, 2001: 21). We meet different advertisements around us daily, but the only marketing that we actively

respond to is most often a recommendation coming from an acquaintance. This means that the WoM process is more active than traditional marketing (ibid.: 22-23). Not only has it become an important marketing channel in today’s advertising but also a prominent source of

information among consumers (Chen & Yuan, 2019: 7). When using influencers in

word-of-mouth marketing, it is crucial to identify influencers that are effective in reaching potential customers (Liu et al., 2015).

Chen and Yuan (2019) summarise word-of-mouth marketing being constructed around three key factors: valence, linguistics and context. Firstly, valence refers to the tone of the message. Naturally, marketing aims to create a positive picture, therefore, positive WoM is more common. However, negative WoM has a stronger effect on the audience. When it comes to language, emotional speech is considered more persuasive. The authors mean that simple language generates more engagement whereas humour might hurt credibility. Finally, the context has to do with the size and density of the audience. In front of a larger audience, the sender might feel more vulnerable, which makes him/her focus on positive recommendations whilst critique is shared with a smaller audience (ibid.).

As we have discussed earlier, influencers have access to a large audience and can influence opinions and attitudes, thus word-of-mouth marketing is a relevant topic to use in our analysis. With this concept, we can review how an influencer can take advantage of

above-mentioned features and how a company can approach its agendas through this kind of marketing. Especially interesting for our study is that WoM relies on trust, and this strongly links to our research problem.

4.4.

Modes of reception

Carolyn Michelle (2007) has pointed out the absence of a generalised way of researching audience reception. She suggests a schema with which future research can define different forms of audience reception. This kind of common framework will assist the researcher to systematically compare responses in various contexts, find the most common responses and reasons behind viewers’ having different perceptions of the same content (ibid.: 4-5). Due to the capacity of the production to frame a media text, a majority of audience reviews a text in the same way (ibid.: 9). Even so, understandings differ and thus, Michelle (ibid.) classifies four potential modes of audience reception: transparent, referential, mediated and discursive modes.

Table 1. A graphic of Michelle’s (2007) modes of reception.

Watching or reading a piece of media does not always wake strong reactions among the audience. They might take in the information, absorb it and think it as a reflection of reality. In a transparent mode of reception, the audience is given a frame on which the understanding of a media text is based. For instance, the public can empathise or connect with fictive

characters and have an emotional connection with the depicted persons or events. In this case, the media text sets the limits and the viewer overlooks the possibility of a constructed reality (Michelle, 2007: 22-24).

In the second mode, referential mode, the audience compares and reviews the media text with their own experiences (personal history) or something that has happened to someone in the person’s near environment (immediate life world). Thus, the media text is seen side by side

with the real world’s events and other cultural and social contexts may affect the perception. Consequently, the audience can point out issues and discuss the media reality, for example, when an event in the media goes against something that the watcher or people around him/her has experienced (ibid.: 26-27).

If the audience takes a step back from the media text, a mediated mode is on. The audience comprehends the construction of what is seen or read and is aware of its structures. Therefore, the audience might not engage and connect with the media. Instead, they focus on the

technical features, like plot, camera work or editing, features typical to the genre or the potential motives of the media producers and the industry overall. For instance, a motive can be to raise the number of watchers by constructing a dramatic scene and thereby, generate profit (ibid.: 30-33).

Finally, the discursive mode provides the audience with an understanding of media

attempting to deliver a message. Either the mode can be analytical when the watcher receives and understands the message and analyses it further, or it can be positional if the watcher, after understanding the message, indicates his/her position in the message (ibid.: 34). The audience can also deny the message or a part of it, which Michelle (2007: 38) calls a negotiated reading.

Michelle’s framework is a useful tool for us to categorise different kinds of receptions in the study. We will later attempt recognising the characteristics and analyse our interview material by finding these four types of receptions among our interview persons.

5.

Methodology

In this chapter, we will introduce our methodological approach. The study is based on interviews that were divided between expert and audience interviews. To gain more various perspectives, we have also included audience reactions from comment boxes in social media. First, we discuss our choice of constructivist perspective. Next, the interview method will be

discussed followed by a presentation of the material used in the interviews. Then, we will continue by reviewing the content analysis and data analysis methods.

The choice of our research method and theoretical framework has led us to identify the paradigm that is most compatible with our approach: constructivism. Its core theses state that cognition, knowledge about the world and perception of it are constructs (Flick, 2018: 36). Our approach lies closer to social constructivism than radical constructivism, as it has to do with social conventions and knowledge in everyday life. According to constructivists, the knowledge that we have about the world is not simply a portrayal of the given facts, but an effect of a constructive process of production. Social factors as interaction and institutions build and shape our realities (ibid.). This is well-aligned with our assumptions, that the interviewees and social media users commenting on influencers’ promotional content process the received messages and construct their own opinions on the advertisements. Therefore, for a constructivist perspective, the audience’s attitudes and behaviours are affected by their social environment.

The constructivist perspective works well with our qualitative approach because qualitative research is based on comprehending a social reality. Our transcriptions form a text based on oral interviews, therefore, they are the outcome of our data collection as well as a tool for interpreting the data in our analysis (Flick, 2018: 68).

5.1.

Data collection method: Qualitative interviews

This study has been carried out by using individual interviews as a research method. The material that is analysed later on is gathered from 12 interviews where two of them were expert interviews and 10 were audience interviews. Both of these will be further discussed below. An interview is, as the name suggests, a social situation where the interviewer and the interviewee interchange views with each other (Gubrium et al., 2012: 209). As our aim was to acquire profound data on the audience's responses, attitudes and choices, even feelings,

individual interviews were an advisable method choice. Certainly, interviews provide the possibility to focus on details (Collins, 2010: 134).

Due to the prevailing societal circumstances, all our interviews were conducted through a video call. As discussed before in chapter 2.1, Internet penetration in Sweden is high (The Swedes and the Internet 2018 - Summary), which led us to believe that the interviewees are used to and comfortable with video technology. Each of the interviews lasted around an hour, they were semi-structured and followed an interview guide consisting of various themes. When it comes to audience interviews, we utilised the same template in each of them (Appendix 10.1). This was to ensure that we asked the same questions from every interview person and did not fail to remember any critical aspects. As for the expert interviews, two similar guides were prepared beforehand, varying depending on the person’s area of expertise (Appendix 10.1). While conducting both interview types, we asked clarifying questions when looking for more detailed answers from an interview person. Indeed, we encouraged the interviewees to discuss freely and go to sidetracks to acquire interesting information. Each of the interviews was transcribed afterwards to ease the process of analysing. Based on Kvale’s (2007) recommendations, we determined a transcription procedure and a set of standard rules to be followed while writing down the interviews. We strived to achieve a high

correspondence between the recordings and the text, which is why we agreed to write down each word an interviewee says as long as they are of importance to this study, and also note moments when a person was thinking (e.g. hmmm…). We considered putting down pauses unnecessary, as the time or length of the answers is not crucial to this study.

In order to achieve high-quality qualitative research, we also followed the guidelines outlined by Tracy (2010). According to the author, such research is characterised by a complexity of abundance, as well as rigour. Tracy (2010) argues that explanations and descriptions of phenomena should be exhaustive and generous, and researchers should be diligent and

thorough in gathering data and performing the analysis. Having understood that, we strived to devote as much time as needed for conducting the interviews, without setting a time limit for each of them. We did not decide on our sample size in advance but continued interviewing

until we noticed that saturation had been reached. Data saturation is complicated to define and each researcher might reach saturation in different ways. Nevertheless, we mean with the concept that the interviewees’ answers start repeating themselves and no new, significantly important information is acquired (Fusch&Ness, 2015: 1408). Also, the research is possible to be duplicated, which is another requirement for data saturation (ibid.: 1409). We reached data saturation in audience interviews after interviewing 10 people.

5.1.1.

Strengths and weaknesses of the method

Choosing semi-structured interviews as our method proved to be an excellent decision. This format gives the interviewee the opportunity to express their thoughts in-depth. We used interview guides while conducting the interviews, which steered the dialogue without controlling it and also let us add spontaneous follow-up questions when needed. Simultaneously, the interview focuses on certain questions, which gives it a structure (Collins, 2010: 134).

The use of video technology in our research made it possible for us to see the interviewees’ body language and facial expressions. This can be considered an advantage of real-time interviews, as opposed to asynchronous interviews, which do not include nonverbal cues (Ratislav, 2014). Additionally, Herzog in Gubrium et al. (2012: 209-210) argues that interview location is often understated and disregarded as a crucial factor in this research method. Indeed, interviewing in a familiar place like at home creates a friendly environment, which can aid the interviewee to open freely to the questions (ibid.). As our interview persons were interviewed in a location chosen by themselves, most often at home, we believe that it had a contribution to a comfortable interview milieu, which hopefully made the interview situation as natural as possible.

However, we acknowledge that an interview situation is not neutral, which might have an effect on the interviewees’ reactions. For instance, when showing different examples of advertisements and asking about reactions, the interview persons did not have the option to

skip the particular ad, which they sometimes have while surfing the Internet. In such circumstances, they might not have drawn attention to the advertisements and had no

reactions at all. This is one of the disadvantages of the interview method as it is impossible to create a completely natural environment where the interviewer does not impact the

interviewee (Bryman, 2012: 494).

Other criticism of qualitative research includes studies being too subjective as they rely on an interview person’s personal views (ibid.: 405). Also, our presence as researchers and

interviewers might have an impact on the ad reception and answers to our questions. In order to minimise the risk of subjective bias, we utilised the concept of triangulation in our

research. The study will not independently be based on findings from audience and expert interviews, but also on selected comments in social media regarding influencer marketing advertisements that will be discussed below. By merging two sources and types of data, a higher level of credibility might be achieved (Tracy, 2010).

Furthermore, it is crucial to note that interviews as the main method do not provide us

material of which we can draw generalised or definite conclusions (Bryman, 2012: 406). Our study is geographically limited, and social media is constantly evolving, together with the field of influencer marketing, so our study is not universal. Additionally, as much as we strived to write down each word a person says, at times it proved to be impossible due to an inaudible part of a recording or an interviewee repeating the same word multiple times. However, we believe that we can find patterns of common audience reactions and opinions on social media influencers in the current media landscape.

5.2.

Audience interviews

Before starting the audience interviews, we decided about the criteria for a potential interview person. These included three factors: the interviewed person had to have some sort of interest in interior design, be an active social media user, be based in Sweden and understand

but rather persons who identified themselves as enjoying home decoration. That way, they could give us interesting opinions on interior design advertising. The second one was important as we were focusing on the interviewees’ own social media usage in several questions. Finally, the last criterion was a requirement as all our video material included text and lines in Swedish. Also, as Royal Design is a Swedish company having Sweden as its main market, the likelihood of knowing this company was higher with interviewees’ from Sweden.

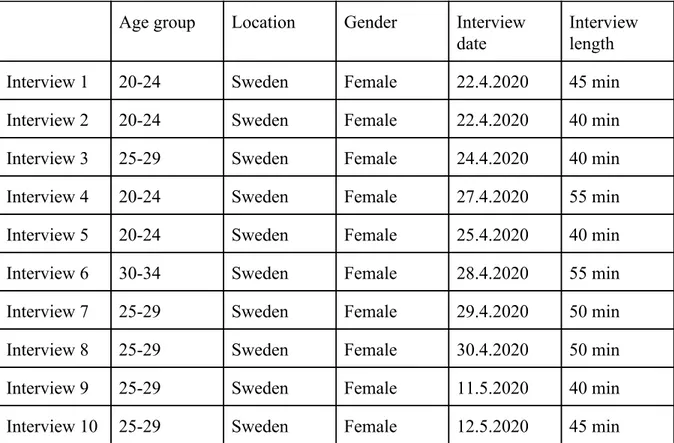

Age group Location Gender Interview date

Interview length

Interview 1 20-24 Sweden Female 22.4.2020 45 min

Interview 2 20-24 Sweden Female 22.4.2020 40 min

Interview 3 25-29 Sweden Female 24.4.2020 40 min

Interview 4 20-24 Sweden Female 27.4.2020 55 min

Interview 5 20-24 Sweden Female 25.4.2020 40 min

Interview 6 30-34 Sweden Female 28.4.2020 55 min

Interview 7 25-29 Sweden Female 29.4.2020 50 min

Interview 8 25-29 Sweden Female 30.4.2020 50 min

Interview 9 25-29 Sweden Female 11.5.2020 40 min

Interview 10 25-29 Sweden Female 12.5.2020 45 min

Table 2. A summary of audience interviews.

We selected the interview persons based on the above-mentioned criteria. We looked for suitable persons in our own social networks and aimed to interview as many people as possible to get more precise results (Bryman, 2012: 198). However, as we had limited resources in this project, a comprehensive sample was not possible. Thus, a convenience sample was used. The disadvantage of this sample is that it is difficult to make generalised conclusions (ibid.: 201). The group of interviewees assembled from our networks ended up being relatively homogenous as they were in the age group between 20-34, females and based

in the same country, Sweden. Bryman (2012: 200) suggests that when the sample is

homogeneous, variation in answers is smaller and therefore, the research can be conducted with lesser interviewees. However, as we are doing a qualitative study, all opinions are of interest. Therefore, we will highlight all kinds of thoughts in our analysis even though the representativeness of our sample is imprecise. Table 2 shows an overview of the participants in audience interviews. As our interviews were anonymous, which will be further discussed in chapter 6, we do not bring up any personal information here that could be connected to the interviewees. Therefore, for example, the ages of the participants are approximate.

Additionally, details about the interview are shared in the table (Table 2).

In the audience interviews, we were curious about the respondents’ typical social media practices, their attitudes on advertising and reactions and responses after seeing three examples of Royal Design’s advertising (see Appendix 10.1).

5.3.

Expert interviews

When the researcher aspires to gain knowledge about a particular subject, in our case

influencer marketing in an interior design company, expert interviews are a useful method to get more detailed data (Flick, 2018: 208). Expert interviews are often more focused on the field of expertise rather than personal attributes, indeed, the interviewee is a representative of a larger group (ibid.: 236). Our experts are professionals within e-commerce and digital marketing, which provided us an insight into the areas from Royal Design’s perspective.

The two expert interviews were conducted with representatives from Royal Design: an E-Commerce Manager and a Digital Specialist. Their views were valuable for us to get an insight into the creation of marketing and advertisements from inside the company. These interviews ended up being around 45 minutes long and were conducted on 23 April 2020 and 4 May 2020.

When selecting and reaching out to interview persons, snowball sampling was used. The sampling method refers to a situation where interviewers get in contact with interview

persons via a common acquaintance. This method was useful when we as interviewers needed assistance in finding suitable interview persons (Bryman, 2012: 202). Royal Design being a relatively big company might have complicated approaching correct persons without a person who knew people inside the company personally.

The expert interviews focused on deep-diving into the marketing practices of the company. We were interested in finding out about the production process, how advertising is targeted and what kind of response the company gets after advertising. Also, questions about the target audience and brand representation were asked (Appendix 10.1). These interviews were

closest to what Flick (2018: 237) calls systematising expert interviews as the findings will be used as a complement to data gathered from audience interviews.

A challenge in using expert interviews is that the interviewee might easily end up giving a lecture rather than participate in a discussion. This might provide interesting information but often also answers that are irrelevant to the study (ibid.: 238). We noticed this in our second expert interview and with the help of our interview guide (Appendix 10.1), tried to draw attention back to the subject.

5.4.

Advertisement examples used in audience interviews

To easily understand our analysis below, we believe it is necessary to introduce the advertisements shown during audience interviews. We focused on three different types of advertisements for Royal Design. Links to each of the videos can be found in the reference list (Chapter 9).Our ambition was to choose advertisement examples that were produced in diverse ways. One of them was a graphic commercial, the second one produced in a studio-like environment and the last one filmed in vlog-format, which means that an influencer is filming herself on a normal day. We believe this variety of advertisements can widen the reactions of the audience and maintain the excitement in the interview situation. Additionally, we chose relatively

recent examples to see Royal Design’s contemporary approach. As the company has a broad selection of products, we picked advertisements that marketed different types of products, from coffee mugs to furniture and lights, so that we hopefully would show a product that interests each interview person.

We consider showing visual examples in our interviews as a strong contribution to the quality of our data. Using visual material has been suggested to wake up the interviewees’

imagination and increase their oral capacities. As we wanted to gain information about reactions and attitudes towards advertising, concrete visual examples of advertisements could inspire the interview persons to answer more thoroughly and in detail than without this type of material. Only asking abstract questions without any illustrations could have turned to vague answers. In fact, visual examples can also contribute to stronger memorisation of past experiences, which can lead to more compelling data. Additionally, an advantage of showing visual material is that visualisation wakes emotions revealing deeper thoughts and ideas (Comi et al., 2014: 112).

Figure 2. Advertisement 1. (Sagolikt och praktiskt från Sagaform!). Translation: Design with the right price.

The first one was a short 15-second clip that possibly has been used in paid social media marketing channels like YouTube (Figure 2). For example, this ad might have turned up when watching videos on YouTube interrupting the chosen video. The advertisement promoted take-away coffee mugs, showing many different design options and the price and the brand of the product, Sagaform. In addition, the video informs the watcher of a current promotion on this product (Figure 3) (ibid.).

Figure 3. Advertisement 1. (ibid.).

Figure 4. Advertisement 2. (RoyalDesign.com, 2019).

Secondly, we showed a one-minute-long commercial video that was produced in

collaboration with a Swedish influencer Andrea Brodin (Figure 4). She is a blogger who works with interior design among other things. The video was published in Royal Design’s own social media channels and the influencer was acting as a host and face for the company. In the video, she presents an idea that a room should be lightened with at least five different sources of light. She is showing her lighting solutions in her own living room with Royal Design’s lighting products. The video focuses on the tips and tricks that Brodin shares (Figure 5) but also informs about a 15% discount on Royal Design’s lighting assortment (ibid.).

Figure 5. Advertisement 2. (ibid.).

Translation: Place the lamps on different heights to create a vivid room

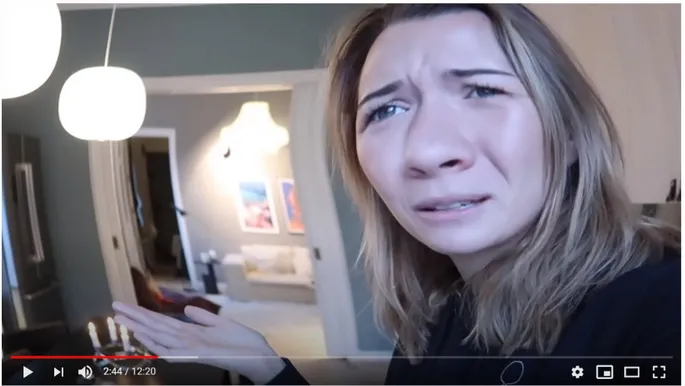

The third advertisement was a paid collaboration with a duration of approximately 2.20 minutes. The collaboration was integrated into a 12.20 minutes long vlog of a Swedish influencer, Margaux Dietz (Figure 6). She is a Youtuber and a blogger with a focus on her lifestyle. When following the everyday life of the influencer, the viewer will in the middle of the video be introduced to some of the influencer’s favourite products from Royal Design.

Figure 7. Advertisement 3. (ibid.).

First, the follower will see a lamp in her living room followed by a big dining table, chairs and decoration items. Dietz tells in her own humorous way (see Figure 7) how these elements make her feel like home and even her followers have been interested in the products

previously. Finally, she mentions that links to all the products can be found in the field below the video (ibid.).

5.5.

Content analysis

Aside from the interviews, we will perform a content analysis of comment boxes on social media referring to influencers’ collaborations. Content analysis as a method allows

researchers to study an area of interest in context (White et al., 2006). According to Neuendorf (2017), it is an “analysis of messages that follows the standards of scientific method (...) and is not limited to the types of variables that may be measured or the context in which the messages are created or presented” (ibid. : 16). Most researchers performing content analysis start with data that is not originally intended to answer specific research questions (Krippendorff, 2019). During the analysis, the text is decomposed into meaningful parts, vital structures are recognized and their understandings are rearticulated (ibid.). In our study, content analysis will serve as an approach to analyse audience reception to selected influencer marketing advertisements and as a way of evaluating the relationship between an influencer and a follower. It will be of interest to see how followers react to the promotional content, if they express their sympathy towards the influencer and whether the advertisement could potentially lead them to purchase at Royal Design. Together with

interviews, the content analysis will provide a more holistic perspective on audience reception to influencer advertisements. Additionally, it will provide us an overview of the audience’s reception in a neutral environment, which was not possible during the interviews as discussed earlier. The content analysis will complement our interview material and permit us to obtain a more triangulated view of audience response.

Triangulation means combining various methods, theories or perspectives within one subject. It was originally used for validating conclusions but today, it is more commonly used for acquiring supporting results. The latter will also be the approach in our study. As we are using two types of methods, our aim is to apply a methodological triangulation (Flick, 2018: 191). We believe this will make our analysis richer in perspectives.

Our initial idea was to analyse YouTube comments on the above-mentioned advertisements, which we use in the audience interviews. In this way, we were hoping to gather more data on audience reception of those particular ads to support our findings. However, we discovered that no users commented on those videos, and in the case of the third advertisement, the comment section was turned off. We searched for comments on other collaborations of Royal Design with the influencers featured in the advertisements, Margaux Dietz and Andrea