good to Be different? on cosmopolitanism, pluralism and ’the good child’ in swedish Educational policy Per Hillbur

the citizen in light of the mathematics curriculum Jonas Dahl & Maria C. Johansson

dialogic manifestations of an augmented reality simulation Thomas Lundblad, Claes Malmberg, Mats Areskoug & Per Jönsson

EducarE

vEtEnskapliga

skriftEr

Lärande och samhälle, Malmö högskola isbn 978-91-7104-490-7 (tryckt) isbn 978-91-7104-491-4 (pdf) 2013 :2 Samhällsfrågor i skolans r E 2 0 13 :2

EducarE

vEtEnskapliga

2013:2

samhällsfrågor i skolans

matEmatik- och

no-undErvisning

good to BE diffErEnt? thE citizEn in light of thE mathEmatics curriculum dialogic manifEstationsoch nordiskt forum där nyare forskning, aktuella perspektiv på utbildningsvetenskapens ämnen samt utvecklingsarbeten med ett teoretiskt fundament ges plats. EDUCARE vänder sig till forskare, lärare och studenter vid lärarutbildningar, högskolor och universitet och alla intresserade inom skola- och utbildningsväsende.

adress

EDUCARE-vetenskapliga skrifter, Malmö högskola, 205 06 Malmö. www.mah.se/educare

artiklar

EDUCARE välkomnar originalmanus på max 8000 ord. Artiklarna ska vara skrivna på något nordiskt språk eller engelska. Tidskriften är refereegranskad vilket innebär att alla inkomna manus granskas av två anonyma sakkunniga. Redaktionen förbehåller sig rätten att redigera texterna. Författarna ansvarar för innehållet i sina artiklar. För ytterligare information se författarinstruktioner på hemsidan www.mah.se/educare eller vänd er direkt till redaktionen. Artiklarna publiceras även elektroniskt i MUEP, Malmö University Electronic Publishing, www.mah.se/muep

redaktion

Lotta Bergman (huvudredaktör), Ingegerd Ericsson, Lena Lang, Caroline Ljungberg, Mats Lundström, Thomas Småberg.

copyright: Författarna och Malmö högskola

educare 2013 :2 Samhällsfrågor i skolans matematik- och NO-undervisning Titeln ingår i serien EDUCARE, publicerad vid

Fakulteten för lärande och samhälle, Malmö högskola. grafisk form

tryck: Holmbergs AB, Malmö, 2013 isbn : 978-91-7104-490-7 (tryck) isbn : 978-91-7104-491-4 (pdf) issn : 1653-1868 beställningsadress www.mah.se/muep Holmbergs AB Box 25 201 20 Malmö

e d u c a r e är latin och betyder närmast ”ta sig an” eller ”ha omsorg för”. educare är rotord till t.ex. engelskans och franskans education/éducation, vilket på svenska motsvaras av såväl ”(upp)fostran” som av ”långvarig omsorg”. I detta lägger vi ett

educare

Mats Lundström

Undervisning i matematik och naturvetenskap har varit obligatorisk i väst-världens skolsystem under många år. Däremot har syftet med denna under-visning förändrats från utbildning av kommande naturvetare till undervis-ning där alla, oavsett framtida studier eller yrke ska kunna använda naturve-tenskaplig kunskap i olika sammanhang. Ofta uttrycks detta i termer av sci-entific literacy; att ha kunskap om naturvetenskap eller naturvetenskapliga begrepp, naturvetenskapliga processer samt behärska användning av natur-vetenskap i olika situationer. Med denna definition blir det av betydelse att kunna använda naturvetenskaplig kunskap även i vardagssituationer, till exempel vid beslutsfattande eller vid kommunikation med andra. På motsva-rande sätt betonas alltmer användandet av matematik i vardagskontexter.

I inbjudan till att skicka in abstract för artiklar till detta temanummer - Samhällsfrågor i skolans matematik- och NO-undervisning - ställdes frågan: - Bidrar dagens undervisning i matematik, naturvetenskap och teknik till att hantera komplexa samhällsfrågor som exempelvis hälsa, demokrati, med-borgarskap, hållbar utveckling och media? Numret innehåller tre artiklar där författarna ger sitt svar på denna fråga.

Per Hillbur utreder i sin artikel - Good to be different? On cosmopolita-nism, pluralism and ‘the good child’ in Swedish educational policy - vilka förväntningar som ställs på individen i skolans styrdokument. Hillbur utgår från begreppet olika (undecidable) som analyseras med hjälp av cosmopoli-tanism och pluralism som analytiska verktyg. Författaren menar att det i dagens samhälle poängteras vikten av respekt för olika kulturer och synsätt. Dessutom anses olikheter och skillnader berikande. Men Hillbur ifrågasätter om skolans styrdokument verkligen uttrycker detta. Författaren har genom-fört en diskursanalys av hur begreppet olika används i fem olika kursplaner i grundskolan. Hillbur kommer fram till att trots att begreppet olika är fram-trädande i många av kursplanerna, uttrycks det ett rätt sätt; den vetenskapliga metoden, den informerade konsumenten eller individen som tillägnar sig det livslånga lärandet där vissa förmågor är avgörande. Hillbur anser att detta tillsammans med den ökade användningen av olika mätningar i skolan leder till en separation mellan ”the good child” och ”the child left behind”. Styr-dokumenten bidrar enligt författaren därmed till en sortering och i förläng-ningen till exkludering av vissa elever.

rar vilka förväntningar som ställs på en medborgare efter att ha läst matema-tik. Liksom så många andra skolämnen betonas ofta matematiken som nöd-vändig för att kunna fungera som en fullvärdig medborgare; att kunna sköta ett jobb, att klara av sitt vardagsliv samt att kunna delta i demokratiska pro-cesser. Författarna utgår i sin analys av vad som i skolans styrdokument uttrycks som nödvändigt för medborgaren från två begrepp, mathematical literacy och ethnomathematics. Mathematical literacy definieras som de kunskaper en medborgare behöver i matematik. Ethnomathematics är de matematikkunskaper som utvecklas i vardagen och fokuserar på kulturell praktik. Dahl och Johansson menar att dessa begrepp bör problematiseras. Går det till exempel att uttrycka någon typ av kärna i matematik som verkli-gen alla människor behöver tillägna sig, oavsett bakgrund eller förgrund? Författarna lyfter fram kulturella aspekter på matematikkunskaper och anser att dessa är viktiga att ta hänsyn till. De ifrågasätter också möjligheten för eleverna att föra in sina egna erfarenheter i matematikklassrummet. Dahl och Johanssons slutsats är att det i styrdokumenten tas för givet hur världen ser ut, vilket medför att styrdokumenten inte tar hänsyn till att olika individer kan möta olika utmaningar och därmed behöver behärska olika strategier och procedurer kopplade till matematik. Författarna föreslår att kommande styr-dokument mer ska lyfta fram matematik som en social aktivitet samt en akti-vitet som syftar till att kunna vara med och påverka och förändra samhället.

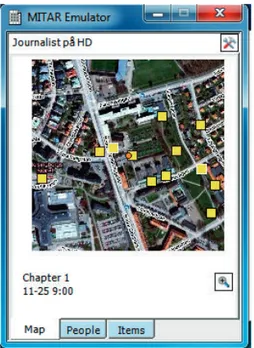

Thomas Lundblad, Claes Malmberg, Mats Areskoug och Per Jönsson vi-sar i sin artikel, Dialogic manifestations of an augmented reality simulation, hur undervisning kring socio-scientific issues, dvs samhällsfrågor med na-turvetenskapligt innehåll (SNI) kan ske med hjälp av simuleringar. Förfat-tarna utgår ifrån begreppet scientific literacy och där användandet av natur-vetenskaplig kunskap i olika situationer betonas. Lundblad och kollegor anser att användandet av spel och simuleringar än så länge inte har utnyttjats i tillräcklig omfattning. Gymnasieeleverna i deras interventionsstudie under-sökte med hjälp av rollspel och mobiltelefoner hur en transformatorstation riskerar att påverka människor i närheten av transformatorstationen. Elever-na fick ta olika roller som till exempel jourElever-nalist, ingenjör eller ordförande i studentföreningen. Vissa av rollerna fick samla in data med hjälp av mobilte-lefonerna. Uppgiften innebar att eleverna skulle använda både kunskap i naturvetenskap och om hur naturvetenskaplig och teknisk kunskap omsätts och diskuteras i samhällsbyggandet. Uppgiften avslutades med en

klass-hälle. Författarna drar slutsatsen att eleverna använder både kunskap i natur-vetenskap, om naturvetenskap samt värderingar och attityder när de arbetar med SNI med hjälp av simuleringar och mobiltelefoner. Fördelarna med arbetssättet som lyfts fram är enligt författarna att kunna göra undersökning-ar utomhus i aktuell miljö, att använda vetenskapliga begrepp i ett samman-hang samt att arbeta tidseffektivt.

Förord

Mats Lundström 3

Good to Be Different? On Cosmopolitanism, Pluralism and ‘the Good Child’ in Swedish Educational Policy

Per Hillbur 7

The Citizen in Light of the Mathematics Curriculum

Jonas Dahl & Maria C. Johansson 27 Dialogic Manifestations of an Augmented Reality Simulation

Thomas Lundblad, Claes Malmberg, Mats Areskoug & Per Jönsson 45

Good to Be Different? On Cosmopolitanism,

Pluralism and ‘the Good Child’ in Swedish

Educational Policy

Per Hillbur

Being a part of a larger project on subject positions of the child in policy docu-‐ ments and teaching materials, this article focuses on the role of undecidables in the fabrication of the so-‐called good child in the Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school. Within a framework of governmentality, the curriculum represents technologies of government, providing an undecidable terrain open for interpretation and decisions by subjects. Through the lens of education for sustainable development, I have selected five school subjects of particular in-‐ terest for analysis: biology, civics, geography, home and consumer studies, and physical education and health. By focusing on the undecidable olika, meaning ‘different’, in the five syllabi, a pattern of features designating the good child emerges: (1) science-‐based categorization, (2) the lifelong learner, (3) the in-‐ formed consumer, and (4) celebration of diversity. These four features repre-‐ sent a political rationale characterised by a contradictory amalgamation of cosmopolitanism and value pluralism. In combination with an increased em-‐ phasis on measurement and assessment in Swedish education, this reinforces abjection processes in school, separating ‘the good child’ and ’the child left behind’.

Keywords: cosmopolitanism, difference, education for sustainable develop-ment, the good child, undecidables

Per Hillbur, Associate Professor, Malmö University per.hillbur@mah.se

Introduction – conceptual framework

This contribution elaborates on the role that educational policy texts have in designing ‘the good child’ (Popkewitz, 2009). The study is part of a more comprehensive project1 focusing on subject positions in educational

1 This study is a part of a research project, “The eco-certified child. Subject constructions in education for sustainable development” 2012-2015 (Malin Ideland, Claes Malmberg and Per Hillbur), financed by the

as well as als on education for sustainable development. As a part of this, I have made an in-depth study of the current Swedish national curriculum for the compul-sory school (Skolverket, 2011) and, in this article, I summarise and discuss some of the results that pinpoint the fabrication of the good child as a com-petent, cosmopolitan humankind and the possible consequences of that for practical teaching2. The analysis focuses on cosmopolitanism and pluralism in the fabrication of ‘the good child’, while the theme of ‘education for sus-tainable development’ is here primarily as a methodological tool to select relevant texts. The selected syllabi and the analysis of the curriculum is also part of a more general analysis of governmentality in policy documents in the research project.

The cosmopolitan child

Cosmopolitanism is a widely used tool for delineating the universal role of science and the consequences for human behavior and modes of living. Al-though ever-present in educational policy historically, cosmopolitanism has been employed in recent years as a lens through which the educational sys-tem and its role in the society can be understood (see e.g. Hargreaves, 2003; Popkewitz et al. 2006: Popkewitz, 2009). Popkewitz et al. (2006:432) makes a characterisation of the Learning Society, a society that is underpinned by a compassion for change and innovation, and

where all children and adults are cosmopolitan in outlook through a continual process of learning made possible through the computer and Internet (ibid.).

Furthermore, the cosmopolitan identity of the child

shows tolerance of race and gender differences, genuine curiosity to-ward and willingness to learn from other cultures, and responsibility toward excluded groups within and beyond one’s society (Hargreaves, 2003:4-5).

Problem solving has a particular role when constructing the cosmopolitan child. Popkewitz (2009) argues that problem-solving provides ‘salvation’ and that behavioural principles governed by problem-solving appear almost as moral principles. This is a way of capturing and governing the child’s soul Swedish Research Council. The project focuses on understanding how political reforms and pedagogical models allow (or reject) different subject positions in education for sustainable development.

2

The discourse analysis is conducted with the Swedish text as a basis. References and direct citations in this article relate to the Swedish version. All translations of the original text into English are, however, taken from the English version: Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre, Skolverket 2011.

(ibid:204-205). As will be explored through the analysis of the Swedish na-tional curriculum, it is interesting to see whether problem-solving as forma-tion of the cosmopolitan child takes place more in the form of pedagogical practices aiming at developing generic competencies/skills, or if this is also a part of disciplinary training in the respective subjects. The case described below provides an analysis of the syllabi of five subjects, each with some distinct elements of education for sustainable development.

Pluralism in education

A further challenge is to capture the role of pluralism in the fabrication of ‘the good child’. In an educational setting, pluralism would imply that indi-vidual differences are respected and acknowledged, and that they enrich educational situations. At a more general philosophical level, pluralism of values means that several values may be correct and fundamental for under-standing, although in conflict with each other. In this case, the use of the undecidable ‘difference/different’ will be explored in further detail.

Pluralism in education is explored here as a discourse analysis of policy documents, using the discourse of ‘education for all’ (UNESCO, 2000) and the fabrication of ‘the good child’ (Popkewitz, 2009) as contrasting, but also overlapping, categories in the deconstruction of concepts and textual inter-pretations. This may also have implications for the discussion on current trends of assessment, measurements and detailed governance of knowledge/ skills in an international arena. Does ‘education for all’ mean mainstreaming towards particular skills and knowledge, or is it good to be different?

Governmentality and the power of texts

The theoretical approach of the study rests on an interpretation of Foucault’s (1991) concept of governmentality and the related processes of governance in the field of education. Rose and Miller (2010) elaborate on governmental-ity by referring to three different, though intertwined, levels: (1) political rationalities, (2) programmes of government and (3) technologies of gov-ernment. I will here see the policy documents that are used as empirical ma-terial in the study as ‘technologies of government’, launched as a part of a programme of government (school reforms) in line with certain political rationalities to change/adapt the educational system—including all chil-dren/citizens—to a (learning) society characterised by globalisation, com-petitiveness and scientific progress.

Education for sustainable development is a field that is closely linked to a political rationality of education based on individual responsibility and ac-tion, including moral responsibilities for social and intergenerational justice. The intrinsic assumptions about the society in the future do also imply a risk

as well as of being trapped in a complex epistemology, expressed by its own idiom (Rose and Miller 2010). This idiom (language) is a mix of rational scientific statements, moral judgments and vague predictions about a ‘common fu-ture’. I will use the term undecidability (Norval, 2004) to explore the policy documents from the perspective of deconstruction of texts and their mean-ing.

Governmentality and undecidability

Undecidability should be understood in its development in relation to decon-struction; the latter sometimes seen as a condition for democracy and, as such, is used widely for political/ideological analysis. In this paper, I will not go into the details of the ideological implications of deconstruction, but refer to it as a way to do morphological analysis of policy documents. In this con-text, undecidability should be understood in relation to responsibility and ‘democracy-to-come’ (Norval 2004), a theme that is useful for the fabrica-tion of the good, cosmopolitan child.

Therefore, undecidability is not mere indecision, but rather the possibility of acting and deciding between two determined poles. Seen as governance, a decision is not merely an action of calculability, but something that has passed through ‘the ordeal of undecidability’ (Derrida, 1988), a continuously on-going process3. This undecidability reinforces governmentality as an in-visible, although ever-present, trait in educational policy.

The role of undecidables

Educational policy may be an example of an arena which has previously been seen as governed by structural determination, but which is now perme-ated by undecidables and, hence, open to interpretation.

Undecidability provides the infrastructure needed for this opened-up ter-rain, and in the following, I will use undecidables as a way to elucidate how texts are built up of words and concepts of unsettled meaning. This kind of text is not necessarily consciously created to be misleading or to impose power relations, but it is the power of the text itself and different interpreta-tions of the text that is powerful and potentially hegemonic (cf Foucault, 1991).

The use of undecidables, for example, words/concepts with a double (or unsettled) meaning, is an important tool for the analysis of policy documents in relation to the discourse surrounding ‘education for all’ and the fabrication of ‘the good child’. The discourse displays hegemonic concepts such as

3 In practice, an intervention by a subject is needed to close the distance between the undecidable struc-ture and the decision (Norval, 2004, p. 142). For a general overview of the relation between hegemony, the decision and the subject, see Laclau and Mouffe (2001)

cosmopolitanism and pluralism which, in turn, relate to recent years’ focus on measurement and assessment as a taken-for-granted part of ‘good educa-tion’ (for further reference, see e.g. Biesta 2010).

In this brief study, I have decided to take a closer look at the Swedish word olika, which is by far the most common undecidable in the text4. In English, it has several parallels; as an adjective, olika translates into a range of meanings ‘different’, ‘various’, ‘several’, ‘diverse’, ‘unequal’, ‘variant’, ‘dissimilar’ or ‘uneven’; and, as an adverb: ‘differently’. The related noun, skillnad (‘difference’) is, however, not included in the analysis.

Aim and research questions

The aim of the study is to analyse the role of undecidables in the fabrication of ‘the good child’ in the Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school. The study object is the use of the undecidable olika (‘different’) in the syl-labi of five different subjects. This leads to the following research questions: • In what ways are the hegemonic concepts of cosmopolitanism

and pluralism discernible in particular technologies of govern-ment, in this case, the Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school?

• How can the use of undecidables provide an infrastructure for governing and the fabrication of ‘the good child’?

• Where are the various representations of the undecidable olika in the Swedish curriculum? To what extent are the various repre-sentations supported by the texts on knowledge requirements and assessment of schoolchildren?

Methodological approach

The study is a discourse analysis of the Swedish national curriculum for the compulsory school, which represents a technology of government. I employ the concepts of cosmopolitanism and pluralism in the analysis to highlight aspects and representations of the discourse of ‘education for all’ and the fabrication of ‘the good child’. The extraction of examples is based on the deconstruction of ‘difference’, which is represented in this document by the undecidable olika. The occurrence and meanings of olika in different parts of the curriculum are the basis for the analysis of how ‘the good child’ is fabri-cated. It should be understood that this approach is not a complete analysis of this discourse in the curriculum, but is singled out to explore subject

4 Some other potential undecidables in the text, although much less prominent, are: ”effect/affect –

påverka/inverka”, “communicate/communication – kommunicera/kommunikation” and “change – förän-dra/förändring”.

as well as

structions of the child. In addition, the focus on ‘difference’ provides per-spectives on barriers and opportunities for interpretation of the curriculum by teachers. In this respect, the syllabi are divided into two major categories: core content and knowledge requirements. To simplify, these two entities can be said to represent ‘what is taught/learned’ and ‘what is assessed’, re-spectively.

The notion of ‘difference’ in the Swedish curriculum

Outline of empirical study

The material used for the analysis is the main text for the current Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school (Skolverket, 2011). A particular em-phasis is placed on the syllabi of five subjects that, in various ways, address education for sustainable development: biology, geography, home and con-sumer studies, physical education and health, and civics. The body of text comprises the full syllabi, covering the aim, core content and knowledge requirements of each of the five subjects. In the following text, page refer-ences relate to the syllabi in the Swedish version.

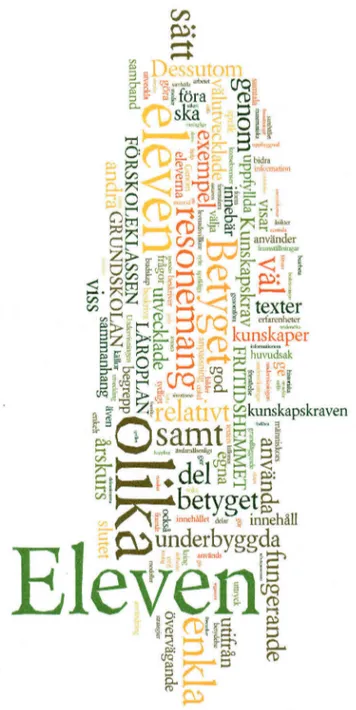

Figure 1. Word cloud representing the occurrence of the most common words in the national Swedish curriculum. The word ‘olika’ (different) is the second most common word, used 1277 times. The most common – ‘Elev-en/eleven’ – denotes (T)he pupil. (Skolverket, 2011 and Wordle, 2013)

as well as

Biology

The national syllabus in biology (Skolverket, 201, pp. 111-126) is open to a range of interpretations of the undecidable olika. As may be expected, a scientific subject such as biology employs separation into distinct categories, as in the core content in years 1-3:

Different phases of the moon – Månens olika faser different seasons of the year – olika tider på året or

Various forms of water: solids, liquids and gases – Vattnets olika for-mer: fast, flytande och gas

An even more common use of olika is to denote a number of possible fea-tures. This is primarily used to invite the student to develop certain skills, such as to use

different sources of information – olika informationskällor different senses – olika sinnen

and

various forms of aesthetic expressions – olika estetiska uttryck This meaning is also used in the knowledge requirements:

Pupils describe the materials used in manufacturing some different ob-jects and how they can be classified – Eleven beskriver vad några oli-ka föremål är tillveroli-kade av för material och hur de oli-kan sorteras

In this case, it is not defined how many objects or which objects are impor-tant to know, although the skill of classifying is considered imporimpor-tant. In the same way, the student is repeatedly instructed to use ‘different sources – olika källor’ although it is not clear whether the various sources should pro-vide different information. According to the knowledge requirements at the end of year six, pupils should however

apply simple/developed/well developed reasoning to the usefulness of the information and sources

Another interesting feature in the analysis of the biology text is the occur-rence of olika in another context. Already during the first three years of compulsory school (ages 7–9), the children are taught

the attempt of different cultures to understand and explain phenomena in nature – olika kulturers strävan att förstå och förklara fenomen i naturen

as a part of science studies core content on ‘Narratives about nature and sci-ence’. Later, during the years 4–6, the teaching, as part of the core content ’Biology and world views’ focuses on

Different cultures – their descriptions and explanations of nature in fiction, myths and art, and in earlier science – ’Olika kulturers beskrivningar och förklaringar av naturen i skönlitteratur, myter och konst och äldre tiders naturvetenskap’

It is easy to recognize the ambition of teaching the history of science to young students, but the interpretation of what ‘different cultures’ would be in a multi-cultural classroom goes beyond most biology teachers’ training, as well as their teaching methods. In this case, I argue that ‘olika kulturer’ may reflect a hidden pluralistic agenda in the text - a true ‘undecidable’. Further-more, it is not clear whether the teaching should list, not only a number of cultures, but state that these cultures may also think differently about nature and science.

This example shows a few of the challenges that teachers face. To draw a parallel to what ‘good education’ would be in this case, a conclusion is that the knowledge, or thinking, of different cultures is not a part of the assess-ment. The children should have a cosmopolitan orientation, but the knowl-edge that counts is defined through the lens of the Western science culture. Whether worldviews and culture should be part of biology teaching is how-ever a topic for another article.

Physical education and health

The science-based method of describing difference is also apparent in the syllabus for physical education and health (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 51-61). The separation into distinct categories is prominent, especially when denot-ing specific activities, such as

as well as Different ways of swimming – Olika simsätt

different types of training – några olika träningsformer and

Different definitions of health – Olika definitioner av hälsa all of them denoting a particular set of activities.

As physical education in Sweden has a long-standing tradition of friluft-sliv and outdoor education, a recurrent theme in the text is activities at

different seasons of the year – olika årstider and

in different settings – i olika miljöer.

The pluralistic meaning of olika is widespread, and the effect on the curricu-lum is an orgy of expressions: ‘a range of different activities’, ‘different physical contexts’, ‘different conditions and environments’ and even in talk-ing about the experiences of different physical activities. The exploration of trying several different things is also reflected in the requirements for higher grades. There is a particular stress on the skills to adapt to various conditions and environments.

Physical education and health has, as the name implies, a particular focus on health issues and the introduction to the subject states that

Physical activities and a healthy lifestyle are fundamental for people’s well-being

As a healthy lifestyle is an important goal for all human beings, the study content should therefore include

different views of health, movement and lifestyle – olika synsätt på hälsa, rörelse och livsstil

This is an important part of the fabrication of ‘the good child’, a child that is competent and gradually capable of solving her own problems. The connec-tion to sustainable development is not explicit here, although the importance of ‘natural and outdoor environments’ and ‘a healthy lifestyle’ is certainly a hint on how to prepare for a successful life.

Home and consumer studies

The syllabus for home and consumer studies (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 42-50) is an interesting object of study, as it prepares the child for life after school in a particular way:

Knowledge of consumer issues and work in the home gives people important tools for creating a functioning daily reality, and the ability to make conscious choices as consumers with reference to health, fi-nance and the environment.

Much of the study content in home economics is focused on the ‘conscious choices’ that signify a competent consumer. The approach of the text is largely scientific, using the terms “different methods” and “different tools”. Although there is room for interpretation of the use of olika, it is more diffi-cult to see a range of options in

Comparisons of products based on a number of different aspects, such as price and quality

or

how meals can be composed to satisfy different needs. Nevertheless, the pupils should:

develop knowledge of cultural variations and traditions in different households

as well as knowledge and skills to

plan and prepare food and meals for different situations and contexts. Home and consumer studies is certainly a subject where the potential of the multi-cultural classroom can be explored, and the study content supports that in several ways.

When it comes to assessment and the formal requirements, there is less room for differences in perspectives. A recurrent theme is for the critical consumer to know

as well as and to have

skills to make informed choices: ability to make comparisons between different consumption alternatives

and to apply

informed reasoning to the consequences of different consumer choices and actions in the home with regard to aspects concerning sustainable social, economic and ecological development.

These are but a few examples of how children are governed towards an ide-al, where the individual child assumes to be responsible not only for her actions, but also for the future of the planet.

Geography

The conditions for life on Earth are unique, changeable and vulnera-ble. It is thus the responsibility of all people to use the Earth’s re-sources to support sustainable development. Interaction between peo-ple and their surroundings has given rise to many different living envi-ronments. Geography gives us knowledge of these environments, and can contribute to an understanding of people’s living conditions. (Skolverket, 2011, p. 159)

The geography syllabus (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 159-171) provides several opportunities to discuss the fabrication of the cosmopolitan child, and the role of sustainable development in ‘good education’. As shown above, geog-raphy is also concerned with differences in physical and human environ-ments and the relations between the two. Consequently, this interaction

has given rise to many different living environments

but also—which is of particular interest here—the knowledge of these envi-ronments can

contribute to an understanding of people’s living conditions

The studies in geography may thus provide important knowledge about ‘dif-ferences’ in general, both concerning the physical landscape and socio-cultural conditions.

The social science subjects presented in this article, for example, geog-raphy and civics, share general paragraphs on the core content and require-ments for the years 1-3. These parts of the texts are therefore common for all

of the four social science subjects (including history and religion)5. The ex-pression olika is found in the geography text no less than 53 times. In some cases it is a straightforward separation into categories, such as in

different products and services – olika varor och tjänster different scales – olika skalor

or

different thematic maps – olika tematiska kartor

In several other cases, the interpretation of the meaning of olika is not as easy. There is certainly a focus on ‘difference’ in that, for example, the pu-pils shall

be able to make comparisons between different places, regions and living conditions – kunna göra jämförelser mellan […] olika platser, regioner och levnadsvillkor.

To make distinctions and separations into categories is important, as shown above, and this obviously applies to the humansphere as well. A popular expression in social science, and geography in particular (ten times), is

in different parts of the world – i olika delar av världen

It is not clear whether it is important that the pupils get a broad overview of varying conditions—a possible pluralistic interpretation—or if the teaching is directed towards comparative studies, where differences between envi-ronments and between people are in focus. One of the most difficult chal-lenges in geography has traditionally been to strike the balance between environmental determinism and comparative studies, and this geography syllabus gives no clear answer to how teachers are to handle that challenge. On the contrary, the opening paragraph (above) is open to all kinds of inter-pretations on how people are formed by the physical environment.

Another interesting detail is the translation of the knowledge require-ments about the use of sources in different subjects. In geography, the ex-pression ‘different sources’ is not used. Instead, pupils are to apply

reasoning about the usability of their sources (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 164-165, year 6, my emphasis)

as well as as well as

informed reasoning about the credibility and relevance of their sour-ces (ibid, pp. 166-167, year 9, my emphasis).

To some extent, this feature occurs in the other social sciences and in the science subjects as well, but is notable in geography. Here, a possible interpretation would be that the pupils should develop skills in arguing for their choice of source in addition to the mere collection of informa-‐ tion from a number of sources.

Civics

Although the word olika is the second most popular word in the Swed-‐ ish curriculum document (see Figure 1), the use of it in the civics sylla-‐ bus (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 199-‐212), is conspicuous (78 recordings). There seems to be no end to how the teaching could reflect different perspectives, different standpoints, different interests or different ac-‐ tors and in what ways these are represented in different media or from different sources. In the knowledge requirements, pupils

assess and express different viewpoints in societal issues related to them

search for information about society and use different sources, and have

basic/good/very good knowledge of different societal structures, already at the end of year 6.

Civics is certainly oriented toward societal functions and, in particular, the basic elements of a democratic society and its principles. Several pas-sages focus on the critical examination of information, media and other sources, as well as the preparation of young people to take active part in the society by learning about

[W]ork of different organisations in promoting human rights, knowing “[W]here different decisions are made”,

as well as

the advantages and disadvantages of different forms of joint decision-making

The civics syllabus is definitely filled with notions of an exemplary life in a pluralistic, just and democratic society.

Summing up: The fabrication of ’the good child’

While reading the curriculum from this ‘different perspective, a pattern emerges in the fabrication of ‘the good child’. The first feature is that of the scientific method. There is a strong emphasis on particular scientific skills that relate to sorting into categories, differentiation and distinc-‐ tion. This is particularly evident in biology and home and consumer studies, where the latter builds on the tradition of the scientific method where the ‘recipe’ rather than a creative process seems to be the way to higher levels of understanding. There are right and wrong ways of doing things. Even the social sciences (geography and civics) follow these sci-‐ entific routines of classification and categorisation to a great extent, which is interesting as it relates to humans and societal structures.

A second, striking feature is that of the lifelong learner, focusing on the skills to search, use and analyse information. This was particularly repre-sented in our sample in biology, geography and civics.

The third feature of the pattern leading to the fabrication of ‘the good child’ is the celebration of diversity, which is apparent in physical educa-‐ tion and health (diversity of activities) and in home and consumer stud-‐ ies, where the core content supports variation in cultures and traditions. The concern the biology syllabus raises about attempts to understand different cultures is, however, more complex and a challenge to teach-‐ ers. None of the syllabi analysed show particular interest in the ac-‐ knowledgement and respect for individual differences, for example, the ethical dimension of pluralism.

A fourth feature—the informed consumer—is apparent in home and consumer studies which, to some extent, is supported by the social sci-‐ ences early on (years 1-‐3) with knowledge about

different payment methods and what ordinary goods and services can cost (Skolverket, 2011, p. 163).

The informed consumer perspective is, however, absent from the knowledge requirements.

Finally, a reflection on the wealth of pluralism and cosmopolitanism in the social sciences: As described above, geography and civics provide a mix of all the above fabrications of ‘the good child’—the scientific per-‐ spective, the lifelong learner, the informed consumer and the readiness to deal with cultural and social differences. What differs is that in the

as well as

social sciences, these fabrications are followed up in the assessment of the child through knowledge requirements. The undecidable terrain of these subjects, where classification and degrees of performance are critical for assessment, calls for further investigation, with the relation between the undecidable structure, the subject (teacher) and the deci-‐ sion being of particular interest.

Good to be different? Concluding remarks

The fabrication of the good child is a result of governing through technologies of government. These technologies are created within a framework of political programmes (school reform) which, in turn, are set into action to support a particular political rationality. Cosmopol-‐ itanism and pluralism are central hegemonic concepts in the formation of the current political rationality to induce change in Swedish schools.

The Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school of 2011 is also part of a shift of paradigm in education, namely the increased emphasis on performance, measurement and assessment of the individual from the early years and onwards.

In this particular study, I have consciously selected a closely-‐defined path in my analysis of the curriculum by narrowing down the scope with which to study the terrain of undecidability and the use of undecidables. Furthermore, I have decided to focus on five syllabi, which represent the curriculum’s ambitions concerning education for sustainable develop-‐ ment. This approach has obvious limitations, which also apply to the overarching aim to explore the fabrication of the good child. A major shortcoming is that the general texts about the “Fundamental values and tasks of the school” (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 7-‐11), as well as the “Overall goals and guidelines” (ibid, pp. 12-‐19), which cover essential parts on norms and values in the educational system, are not included in this article. The rationale for this was to take a closer look at how ‘the good child’ is fabricated in the syllabi texts.

A general objection to this approach may be that little has been said about problem solving, and its essential role in constructing the cosmo-‐ politan identity. Still, there is evidence that strongly supports the scien-‐ tific method and science-‐based perspectives, of which problem-‐solving is a crucial part. There is probably a need for a closer look at particular subjects, but also, a more general analysis of the knowledge requirements at different ages may be instrumental in deciding the role of problem-solving for the fabrication of ‘the good child’.

So, what can be concluded from the analysis of undecidables? The main discourses related to in this article—‘education for all’ and the fabrication of

‘the good child’—prove, at least to some extent, to be two sides of the same coin. The inclusion of different perspectives and different groups is also a process of sorting and defining categories which, in turn, leads to the exclu-sion of some of these perspectives and people. This is what Popkewitz (2009, 64f) means by abjection, the design of a ‘good child’ that, in turn, creates ‘the child left behind’.

When turning to the syllabi, there is a deep gorge between core content and knowledge requirements which applies to all the studied subjects. Some of the subjects simply do not have the ambition to measure or assess the content that is to be taught, while others (like the social science subjects), in trying to be consistent, run the risk of using a quantifying language about qualitative performances and skills. It could be argued that this method of governing through measurement and categorisation is at the heart of cos-mopolitanism. Hargreaves (2003) is particularly concerned with this devel-opment:

Yet instead of fostering creativity and ingenuity, more and more school systems have become obsessed with imposing and microman-aging curricular uniformity. In place of ambitious missions of com-passion and community, schools and teachers have been squeezed into the tunnel vision of test scores, achievement targets, and league tables of accountability” (ibid, p. 1)

What is intriguing in the Swedish curriculum is the contradictory, side-by-side existence of cosmopolitan values and the celebration of diversity in its aims and core content. In discussing assessment and the knowledge require-ments of the child, celebration of diversity is no longer a mainstream plural-ist feature, but still calls for a deeper concern for management of conflicts (Dryzek and Niemayer, 2006, p. 635). The obvious conflict is for the subject (teacher) in this landscape of undecidability to come up with the ‘right’ deci-sion about the interpretation of ‘difference’. Is it even possible to imagine pupils displaying different knowledge within a particular field? Are there different ways to succeed in the Swedish school system?

After this thorough reading of the current curriculum, it seems the Swed-ish teachers have less room to manoeuvre within the current paradigm. Un-less measures are taken to reinstall creativity and to recognise individual differences as the indispensible resource it is in education, only time will tell how far the abjection processes will take the divide in schools and, thus, in the society as a whole.

as well as

References

Biesta, Gert J J (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Derrida, Jacques (1988). Limited Inc. Northwestern University Press. Dryzek, John S and Niemayer, Simon (2006). Reconciling Pluralism and

Consensus as Political Ideals. American Journal of Political Science. 50(3), 634–649.

Foucault, Michel (1991). 'Governmentality'. In Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller (Eds.), The Foucault Effect: Studies in Govern-mentality, (pp. 87–104). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (Ori-ginal text translated by Rosi Braidotti and revised by Colin Gordon) Hargreaves, Andy (2003). Teaching in the Knowledge Society, Education in

the age of insecurity. New York: Teachers College Press.

Laclau, Ernesto and Mouffe, Chantal (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Second Edition. London: Verso. Norval, Aletta J (2004). Hegemony after deconstruction: the consequences

of undecidability. Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(2), 139–157.

Popkewitz, Thomas S, Olsson, Ulf & Pettersson, Kenneth (2006). The Lear-ning Society, the Unfinished Cosmopolitan, and GoverLear-ning Education, Public Health and Crime Prevention at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38(4), 431-449.

Popkewitz, Thomas S (2009). Kosmopolitism i skolreformernas tidevarv. Veten-skap, utbildning och samhällsskapande genom konstruktionen av barnet. Avancerade studier i pedagogik. Liber: Stockholm. (Original in English: (2008). Cosmopolitanism and the Age of School Reform. Science, Educa-tion, and Making Society by Making the Child. Taylor and Francis). Rose, Nicholas & Miller, Peter (2010). Political power beyond the State:

pro-blematics of government. British Journal of Sociology, 61(1), 271-303. Skolverket (2011). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och

fritids-hemmet 2011. Stockholm: Fritzes. (English version (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre 2011. Stockholm: Fritzes.)

UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2000). The Dakar Framework for Action. Education for All: Meeting our Collective Commitments. Adopted by the World Education Forum. Dakar, Senegal, 26-28 April 2000.

Internet sources

Wordle (2013) Good to be different? Word cloud published by Per Hillbur 2013-10-10. www.wordle.net

The Citizen in Light of the Mathematics

Curriculum

Jonas Dahl & Maria C. Johansson

In this article, the mathematics needed for citizenship is discussed in relation to the Swedish curriculum. The article considers two approaches for discussing mathematics as demanded by, or developed within, a society: mathematical literacy and ethnomathematics. These approaches provide an alternative understanding for school mathematics in relation to citizenship. In reconsider-‐ ing the expectations upon the future citizen produced from implementing the curriculum, an argument is made for the curriculum to include elements from critical and socially responsible mathematics education, which include ele-‐ ments of ethnomathematics and mathematical literacy. Such reconsideration is necessary because the transfer of mathematics from school to the outside world is not a straightforward matter. Therefore, it is essential that more focus is directed at citizens in the curriculum, and the transitions they undertake during their trajectories in life, to and from school.

Keywords: citizen, curriculum, ethnomathematics, mathematical literacy, transition

Jonas Dahl, PhD student, Malmö University. jonas.dahl@mah.se

Maria C Johansson, PhD student, Malmö University. maria.c.johansson@mah.se

Introduction

The aim of this article is to consider how school mathematics is connected to citizenship in the Swedish curriculum. This is related to that of determining the mathematics that every citizen needs, for instance to meet requirements for getting a job, to handle mathematical activities in order to cope with everyday issues or to understand and change society. The notion of citizen-ship in this article is connected to the mutual process between the society and the citizens in which the citizen is seen as having an active part in this dual interplay (EPACE, 2010).

Wedege (2010) suggests that determining the mathematics that every cit-izen needs has to do with two types of “knowing mathematics in the world”. The first type is knowledge developed in everyday life, for example, ethno-mathematics, folk ethno-mathematics, and adult numeracy. The second type is knowledge wanted in everyday life, such as mathematical literacy, math-ematical proficiency or mathmath-ematical competence. We draw on this distinc-tion using the labels ethnomathematics and mathematical literacy as analyti-cal constructs in order to interpret what is required of the citizen, as ex-pressed in the curriculum. This should be regarded as a way of approaching understanding, rather than creating or interpreting a dichotomy, as the prob-lem is far more complex. It can be understood as dividing school mathemat-ics and the curriculum along practical and theoretical considerations. How-ever, this can be counterproductive, or, as stated by Atweh and Brady (2009), when discussing real world applications versus the dominant dis-course of formalised academic mathematics:

Seen in this way, the intellectual quality of mathematics is measured primarily from within the discipline itself rather than the usefulness of that knowledge for the current and future everyday life of the student. (p. 271)

In focusing on the mathematics that is considered necessary for citizens, we do not discuss mathematics as an academic discipline per se, nor will we focus on the mathematical context. Instead, our intention is to focus on the relationship between the citizen, the mathematics s/he is supposed to need, and the mathematics s/he is supposed to develop in relation to what is writ-ten in the curriculum.

Ethnomathematics is connected to the mathematics people develop in everyday life. It focuses on cultural practices, which can be considered re-lated to mathematics and power (Knijnik, 1999; 2012). According to D’Ambrosio (2001; 2010), an ethnomathematical approach can contribute to peace, equity and human dignity. Research using an ethnomathematical per-spective reflects manyfoci, such as recognising uses of mathematics in

dif-ferentcultures or on its contribution to a more global and just society (Ev-ans, Wedege, & Yasukawa, 2013).

Mathematical literacy also has various foci, aims, and implications. For the purposes of this article, this perspective is interpreted as a view on what people need. Jablonka (2003) writes on how mathematical literacy can be interpreted and states that mathematical literacy:

may be seen as the ability to use basic computational and geometrical skills in everyday contexts, as the knowledge and understanding of fundamental mathematical notions, as the ability to develop sophisti-cated mathematical models, or as the capacity for understanding and evaluating another’s use of numbers and mathematical models. (p. 76) Therefore, it seems appropriate to label the mathematics that people need as mathematical literacy. Jablonka (2003) also notes that mathematical literacy is “about an individual’s capacity to use and apply [mathematical] know-ledge” (p. 78). The way mathematical literacy is understood by PISA (OECD, 2006)is similar, but with an emphasis on the individual’s responsi-bility to determine the mathematics they need as citizens:

Mathematical literacy is an individual’s capacity to identify and un-derstand the role that mathematics plays in the world, to make well-founded judgements and to use and engage with mathematics in ways that meet the needs of that individual’s life as a constructive, con-cerned and reflective citizen. (p. 72)

Explicitly, the PISA definition connects mathematical literacy to the zen’s ability to be reflective; although it is not fully clear upon what the citi-zen should reflect or even who the citiciti-zen is.

Using the analytical constructs of ethnomathematics and mathematical literacy, we outline the structure for the discussion in the following section. We then consider how the Swedish curriculum reflects the different con-structs. Using these labels provides insight into the relation between how the citizen is mentioned in the curriculum, both as an issue of demands from the society, in terms of mathematics and also whether there might be an interest in what the citizen could develop through that curriculum. We will also dis-cuss how citizenship is described in the curriculum, and suggest how such a discussion could contribute to a deeper understanding of the mathematically literate citizen and the understanding of her/him in the curriculum. However, we are aware that there are many different viewpoints and stakeholders within the field of mathematics education. Undertaking the challenge to

in-vestigate a field of which we are a part has consequences. Bourdieu (2004) notes:

A scientist is a scientific field made flesh, an agent whose cognitive structures are homologues with the structure of the field and, as a con-sequence, constantly adjusted to the expectations inscribed in the field. (p. 41)

There is a need to be aware of this dilemma. We have been exposed to school mathematics, as well as having exposed others to it. This has given us insight that we could not possibly have gained from the outside. Trying to be reflexive, we aim to understand how different standpoints within the field of mathematics education may have influenced, or should influence, the curri-culum. For this purpose, we have chosen to examine a body of literature, which includes seminal articles written by leaders in their respective fields.

Our point of departure is social, critical, and inspired by the sociomath-ematical perspective (Wedege, 2004; 2010), in which the citizens’ relation-ship to mathematics is in focus. Further, the interplay between general struc-tures and subjective matters is stressed in the sociomathematical perspective (Wedege, 2004; 2010). We suggest that understanding more about what the curriculum states regarding the citizen and mathematics could highlight the possible tension between what is relevant for the citizen and what is required from society.

The Swedish curriculum

In Sweden, school is compulsory until the ninth year, when students are sixteen years old. Upper secondary school is voluntary, although almost every student attends, as requirements from society make it, in reality, com-pulsory. Consequently, what is expressed in the curriculum is what, as inter-preted by Skolverket (The Swedish National Agency for Education), is seen as needed for students who become future citizens. Although Swedish stu-dents can attend different senior secondary programs (in natural science, social science, and pre-vocational), in the core area of mathematics, topics and competences are the same.

The Swedish mathematics curriculum is divided into core content and competences. These are listed in tables 1 and 2. Core content refers to what should be taught in mathematics classrooms, while competences refer to the skills the students are expected to develop and, therefore, provide the framework for assessment (Skolverket, 2011b). Table 2 outlines some fea-tures or ambitions that connect to the world outside of school. In the same table, we include PISA’s overarching ideas and competences. By doing this,

we are not making any particular assumption; instead, we are showing how the Swedish curriculum is not an isolated national phenomenon.

In describing how the mathematics curriculum was designed, Skolverket (2011a) refers to drawing from “international experiences”. While no direct reference is made in this document to PISA, there are similarities between PISA’s definition of mathematical literacy and the Swedish mathematics curriculum. In later reports from Skolverket (see e.g. Skolverket, 2012), there are references to PISA, indicating that PISA was something that Skolverket was aware of when the new curriculum was being written. In Table 1, it can be seen that PISA uses the term “overarching ideas”, whilst in the Swedish curriculum, the correlating term is “core content”.

When it comes to the competences, there are further similarities and these can be seen in Table 2. However, the Swedish curriculum stresses that stu-dents should be able to “relate mathematics to its importance and use in oth-er subjects, in a professional, social and historical context”. This is one dif-ference between the Swedish curriculum and PISA, as these competences are mentioned by PISA only as the role mathematics plays in the world. Never-theless, there are similarities between this in the Swedish curriculum and PISA’s definition of mathematical literacy provided earlier.

Table 1 (OECD, 2006; Skolverket, 2011b)

PISA’s overarching ideas Core content in Swedish mathematics curriculum

Quantity Understanding of numbers, arithmetic and

algebra

Space and shape Geometry

Change and relationships Relationships and change

Table 2 (OECD, 2006; Skolverket, 2011b)

PISA’s competences Competences (förmågor) in Swedish curricu-lum

Thinking and reasoning Follow, apply and assess mathematical rea-soning.

Argumentation

-

Communication Communicate mathematical thinking orally, in writing, and in action.

Modelling Interpret a realistic situation and design a mathematical model, as well as use and as-sess a model's properties and limitations. Problem posing and solving Formulate, analyse and solve mathematical

problems, and assess selected strategies, methods and results.

Representation

-

Using symbolic, formal and technical language and oper-ations

Use and describe the meaning of mathemati-cal concepts and their inter-relationships. Use of aids and tools Manage procedures and solve tasks of a

standard nature with and without tools.

-

Relate mathematics to its importance and usein other subjects, in a professional, social and historical context.

The outcome of school mathematics is likely to be related to the curriculum and may influence the citizen and his/her life trajectories in many possible ways. Therefore, what needs to be problematised is how mathematics educa-tion could provide the students with a foundaeduca-tion for active citizenship, or question if this is even possible. What does it mean to be an active citizen, and how is it connected to the specifics requirements in the mathematics curriculum?

In order to problematise and discuss these issues, we examine in the fol-lowing section what the two approaches, mathematical literacy and ethno-mathematics, contribute to the role that mathematics plays in producing cer-tain kinds of citizens, according to the curriculum.

Mathematical literacy

Wedege (2010) stated: “it is obvious that any definition [of mathematical literacy] is value based and related to a specific cultural and societal con-text.”(p. 31) Understanding these values is connected to who makes the defi-nition (Jablonka, 2003). The defidefi-nition from PISA on mathematical literacy is based on the assumption that mathematical knowledge has a functional value (Wedege, 2010). It “deals with the extent to which 15-year-old stu-dents can be regarded as informed, reflective citizens and intelligent con-sumers” (OECD, 2006, p. 72).

PISA’s definition of mathematical literary seems to stress the importance of the citizen to be “concerned and reflective.” Although the inclusion of “intelligent consumers,” partly contradicts this intention, as the meaning of being a consumer is not questioned. We find another contradiction between the statement: “…in ways that meet the needs of that individual’s life as a constructive, concerned and reflective citizen” and “every country needs mathematically literate citizens to deal with a very complex and rapidly changing society” (OECD, 2006, p. 76, our italics). These statements could form a contradiction if the citizens’ wellbeing and self-fulfilment conflicts with providing society with a sufficient work force.

PISA’s definition of “mathematical literacy” is one of many, as the ter-minology varies among researchers. These standpoints are value based and one aim seems to be to avoid what is “too basic”. For instance, Hoyles, Noss, Kent, and Bakker (2010) suggest that numeracy and mathematical literacy are not sufficient for describing, for example, advanced workplace mathematics. They use the term technomathematical literacy to describe workers’ competence to communicate by means of mathematical and spe-cific technological tools.

Kilpatrick’s (2001) definition is closer to that of PISA’s, but he also sug-gests the word literacy to have a value-based connotation; therefore, he uses the notion mathematical proficiency instead. Within this, he defines five strands:

(a) conceptual understanding, which refers to the student’s compre-hension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations; (b) pro-cedural fluency, or the student’s skill in carrying out mathematical procedures flexibly, accurately, efficiently, and appropriately; (c) stra-tegic competence, the student’s ability to formulate, represent, and solve mathematical problems; (d) adaptive reasoning, the capacity for logical thought and for reflection on, explanation of, and justification of mathematical arguments; and (e) productive disposition, which in-cludes the student’s habitual inclination to see mathematics as a sen-sible, useful, and worthwhile subject to be learned, coupled with a

be-lief in the value of diligent work and in one’s own efficacy as a doer of mathematics. (p. 107)

Kilpatrick et al. (2001) further suggest that these strands are interwoven and interdependent, and should equip students with the ability “to cope with mathematical challenges of daily life and enable them to continue their stud-ies of mathematics in high school and beyond” (p. 116).

The various definitions of mathematical literacy seem to have a common-ality in the focus on different strategies, strands and procedures. In this ap-proach, it seems as if these procedures are considered important for the citi-zen’s wellbeing and ability to cope with issues of everyday life.

The term mathematical literacy, as well as other related terms, is not used in the Swedish curriculum. However, there are statements which seem to suggest that there is in the curriculum the sort of mathematics that students need for active citizenship:

The upper secondary school should provide a good foundation for work and further studies and also for personal development and active participation in the life of society.

The subjects, which mainly contribute to providing a good foundation for personal development and active participation in the life of society, are the upper secondary foundation subjects [e.g. mathematics] (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 8)

The role mathematics could play in contexts such as the social and the professional is taken into account in the ethnomathematical approach, which instead focuses on cultural aspects of mathematics and, hence, diversity and equity due to the connection between power and culture (Knijnik, 2012).

Ethnomathematics

Following Wedege (2010), we interpret the ethnomathematical approach as mathematics developed outside of school contexts, also with the potential to be of interest for school and for informing curricula (Meaney & Lange, 2013).

Ethnomathematics is not only about practical mathematics, but offers an approach focusing on interpreting mathematical activities exercised in dif-ferent groups. Ethnomathematics is described by D’Ambrosio (2010) as relating to the mathematics practiced by different cultural groups, such as workers, indigenous societies, and other groups with shared traditions and objectives.

Ethnomathematics aims to link tradition and modernity, and it provides an alternative to the Western influence in mathematics education (D'Ambro-sio, 2001; 2010). This focus on the cultural practices of different groups