Supporting Immersion of Board

Games utilising Phone-based

Augmented Reality

Axel Gustafsson

axelgeson@gmail.com Interaction design Bachelor 22.5HP Spring 2019Abstract

This thesis investigates a possibility of using phone-based Augmented Reality in a board game-setting in order to support immersion for experienced board game players. Using a user-centered design approach with workshops, interviews and play sessions to understand the qualities and applicability of phone-based Augmented Reality in combination with a board game, the research contributes with an advisory conclusion for future designers developing a board game including phone-based Augmented Reality components.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Henrik Svarrer Larsen for good supervision throughout this project, K3 branch of Malmö University for providing a workspace for us thesis students to dwell, much appreciated, and finally Thomas Pederson and the Egocentric Interaction research group for providing me with inspiration for the topic of this thesis.

Contents

Abstract ... 2 Acknowledgements ... 3 1 Introduction ... 5 1.1 Purpose ... 5 1.2 Delimitations ... 5 1.3 Target group ... 6 1.4 Ethical conduct ... 6 1.5 Research question ... 6 1.6 Contribution ... 6 2 Theory ... 7 2.1 Augmented Reality ... 7 2.2 Board Games ... 8 2.2.1 Related work ... 11 2.3 Immersion in gaming ... 122.3.1 Three levels of immersion ... 12

2.3.2 The SCI-model ... 13

2.3.3 Relevance to Board Games ... 15

3 Methods ... 16

3.1 Interviews ... 16

3.2 Prototyping ... 17

3.2.1 Wizard of Oz ... 17

3.3 The Double Diamond ... 17

3.3.1 Discover ...18 3.3.2 Define ...18 3.3.3 Develop ... 19 3.3.4 Deliver ... 19 4 Process ... 19 4.1 First phase ... 19 4.2 Second phase ... 22 4.3 Third phase ... 23 4.4 Fourth phase ... 27 5 Final thoughts ... 28 5.1 Discussion ... 28 5.2 Conclusion ... 29

1 Introduction

There is uncharted land in the field of AR (Augmented Reality); a conclusion that can be made by looking at the lack, or seemingly low profile, of AR enhanced board games.

This project has been focusing on phone-based AR and the upcoming uses of the term AR refers to that phone-based variant unless stated otherwise. When discussing the individual varieties or phone-based or HMD-based (Head Mounted Display), they will be referred to as such.

1.1 Purpose

There is lacking knowledge of AR enhanced board games, very few existing and basically zero successful AR board games seeing mainstream success in the board gaming scene. The purpose of this research project is to explore the usage of AR in conjunction with board games and pave the way for future game developers as AR technology becomes more advanced and commonplace. What qualities of board gaming can AR facilitate? What interactions and mechanics are best suited for the usage of AR? What are the fundamental requirements to successfully build an AR enhanced board game?

Most board games today that sell themselves as AR board games uses the technology as a niche with the AR not necessarily adding much of value to the gameplay itself in regards of interesting mechanics or functionality. Often used to add visual effects and replace gameboards, tokens, dice and so on; somewhat disregarding the attraction of these tactile artefacts. Such games also often require the use of an HMD or at least designed for it, requiring the player to use a smartphone as a faux HMD to be able to see the generated graphics or outcomes, while at the same time interacting with physical components, resulting in limited manoeuvrability.

As smartphones and phone-based AR are a universal medium as of the writing of this thesis it can be considered that there is an overseen possibility to take advantage of the smartphone’s qualities when designing a board game. Utilising seamless design and qualities of smartphones there is opportunity for phone-based AR to support the immersive and social experience of players through the use of unique mechanics and gameplay elements.

1.2 Delimitations

As previously mentioned, this thesis will not target non-players of board games. It can be assumed that increased immersion will allow for more players overall. This thesis does in greater part discuss game design and the

attraction of better designed games will ultimately prosper in relation to their weaker correspondents.

HMDs are also a technology somewhat overlooked within this project. Even though displays of this kind are relevant when looking at the future of AR enhanced board games, it was decided to focus on phone-based AR and its supposedly wider target group.

I will neither explore the crafting or the material side of physical board games and the impact which AR might have upon it. It could be of interest to evaluate how pieces of a board game could change when used together with AR and object recognition in order to even further support immersion.

1.3 Target group

The target group of this thesis are experienced players of board games. I have during my work defined an experienced player as a player in the first stage of immersion (Ermi & Mäyrä, 2005). Therefore, from here on, will experienced players be synonymous with engaged players and this thesis will focus on how to transform engaged players into engrossed players by breaking the second barrier of immersion and also suggest how total immersion may be accomplished in the setting of playing board games (Brown & Cairns, 2004).

1.4 Ethical conduct

In accordance with The General Data Protection Regulation, data that has been collected containing personal information has been handled according to the guidelines. Also, the Swedish Council Guidelines for ethical conduct (2017) has been followed.

1.5 Research question

The main research question and topic of this thesis is:

“How might we support immersion in board games for experienced players with the use of phone-based AR?”

Sub-questions:

“How does a digital hand-held component function in conjunction with a board game so that the physicality of the board game is not lost”

“What are the limitations of phone-based AR in regard to board gaming mechanics?”

1.6 Contribution

This thesis will contribute to the future development of AR enhanced board games and present maker of such with basic necessary knowledge required

in order to create enjoyable, immersive and fun board game which incorporates AR, mainly phone based.

The work carried out over this project can be seen as a starting guidelines/tips for anyone interested in AR board games.

2 Theory

AR, board games and a definition of immersion along with accompanied theories will be presented. I have looked at several models regarding immersion in computer gaming and have applied relevant aspects that may bring clarity to what and why board games and AR is experienced as enjoyable by players.

2.1 Augmented Reality

The first successful user-immersive AR experience was developed in 1992 with the Virtual Fixtures system by the U.S. Air Force at Armstrong Laboratory (Rosenberg, 1992). AR is an experience of mixed reality, to overlay the real world with digital information and artefacts with a purpose of enhancing or creating an experience. This is experienced through various devises with screens, most common is handheld devices such as smartphones or tables and HMDs. By using AR technologies such as computer vision and object recognition, information in a user’s environment becomes interactable and often allows for digital manipulability.

There are two methods to overlay digital media onto the real world. The first method displays information on a transparent screen in front of the user and can act as a form of heads-up display and is often used for HMDs such as Google Glass, providing visual information to the user within their peripheral vision. However not limited to the peripheral, this method can also be used to show video and other media.

The second method of AR uses the real world as an anchor to generate and display 3D models for the user to walk around and interact with. Such is the case of phone-based Pokémon GO and Microsoft’s HMD HoloLens (figure 0). This is the preferred method of current AR enhanced board games with the focus on visualising game pieces, spells and effects on the gameboard, with it, supposedly reducing ambiguous game elements such as dice falling of the gameboard, inaccurate measurements and so on in an effort to create an appeal for the supposed player.

Figure 0. An example of a HMD, Microsoft’s HoloLens. Reprinted from “Variety”, 2019,

Retrieved from https://pmcvariety.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/hololens-2-image.jpg?w=1000&h=563&crop=1

AR has gained popularity in recent years through smartphone applications such as Pokémon GO and Snapchat filters and is currently a rapid growing medium for entertainment. As mentioned, it is through the rapid success of the smartphone we can see the widespread use of AR today.

2.2 Board Games

The definition of a board game according to the Merriam-Webster (2019) dictionary is a game (such as checkers, chess, or backgammon) played by placing or moving pieces on a board. Board games have a long history, already being played by the ancient Egyptians over 5000 years ago in the shape of Senet. It was then as today a game meant for recreation and over time as Egyptian religion developed it transformed from a game with no religious ties whatsoever into game upon the Egyptians superimposed their religious believes onto the gameboard. This resulted in a thematic game depicturing a player’s travel through, what the Egyptians called, the “netherworld”; the realm of the dead (Piccione, 1980). As Piccione (1980) further describes, “this game was to evolve into a profound ritual, a drama for ultimate stakes”. Perhaps it was a matter of life and death, or to see who were worthy of the gods’ blessings. Whichever the case, and even though taken more literally in ancient Egypt as the religion which the game was based upon was considered fact and not fiction, the aesthetics which this setting implies still are attracting players today.

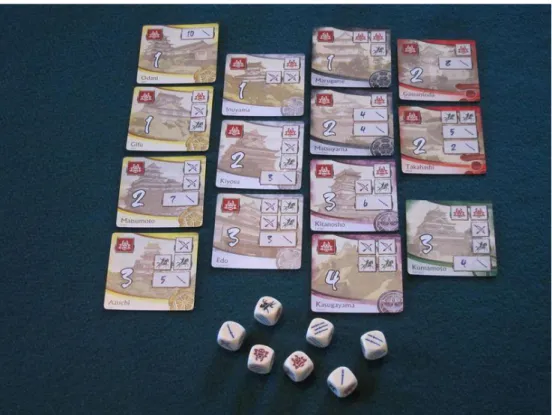

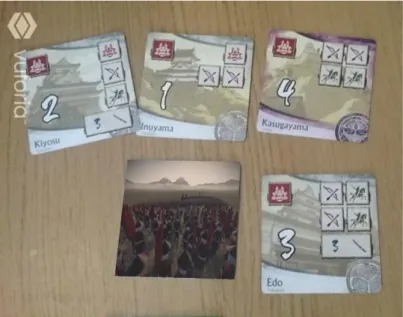

The board games encountered in this thesis are The Age of War (figure A) and Warring States (figure B). Both games are suited for 2+ players and are combat oriented, they are competitive games, and both allow for cooperation between player when played with 3+ players. The Age of War is a dice rolling game set in feudal Japan where the players try to capture cards representing

land/regions by rolling custom dice (the classic die dots are replaced with bow, sword, horse and lord icons) and matching these dice with the icon displayed on desired card.

Figure A. Age of War. Reprinted from “Board Game Geek”, 2014, Retrieved from

https://cf.geekdo-images.com/imagepage/img/cH3QWPpvX5o2ib6uwvYvNLLV8wA=/fit-in/900x600/filters:no_upscale()/pic2270104.jpg

The second game Warring States is an abstract strategy war game that incorporates the use of a digital web application to carry out some of the game’s mechanics; most importantly being managing troops which players use to combat each other in order to win the game. The game starts by opening up the Warring States web application on a computer or mobile device (mobile devices will be used throughout the play sessions of this thesis) and each player selects a team to represent, one player per team. On the web application the player is presented with a digital version of the gameboard, then each player places their initial number of troops on their starting tiles. Following the set-up player takes turns and performs a maximum of three actions per turn. These actions can be: moving troops into an adjacent unoccupied tile (in order to occupy and take control of it), move troops within self-occupied tiles (moving troops this way have longer reach), combat with an adjacent enemy-occupied tile (in order to gain control over that tile if combat is won). A player can also during their turn spy on one tile an enemy is occupying to see the troop strength on that tile, this however does not count towards the three actions. Players do not move their troops with physical pieces on the gameboard, instead they control these actions with the web application. This hides troop strength data from enemy players. The

physical gameboard and tokens are merely serving as an indicator of who owns which tiles and to perform combat. When declaring combat, the attacking player indicates to the defending player where he is attacking (which tile) and with how many troops. The defending player then takes so many tokens that he has troops in the tile that is being attacked into his hands and the attacking player similarly takes tokens equal to the number of troops that he is attacking with. Both players then shake these tokens in their hands and throws them onto a flat surface and then compares the number of tokens facing up. The player with most upward-facing tokens win the combat.

Figure B. Warring States with web application.

Today we can see that board games have entered a “golden era” with sales and interest increased over the past decade. One reason could be credited to the increased use of smartphones and tablets over which it is possible to distribute less expensive digital versions of board games for people to get acquainted with. Another suggestion is that the pure quality of board games is simply getting “better” with well thought out mechanics and aesthetics (Duffy, 2014). Nevertheless, board games are relevant in today’s society. Some might question the necessity of combining the physicality of board games with the digital phenomena that is AR but in a world full of technological marvels where the vinyl-record is making comeback and board games are on the rise the entwinement between board games and technology is unavoidable and exploration of the different variations of board game and technology is for knowledge required.

2.2.1 Related work

Digital versions of conventional board games are today not uncommon. These are however alternatives to their real counterparts and trades enjoyable aspects of physical board games for the sake of convenience as they are being able to be played by multiple player located far from each other. With modern computational power the digital board games can also generate plenty of audiovisual content which traditional ones cannot do. The digital format does not necessarily contribute to a more enjoyable experience but do allow for reduced ambiguous game elements such as dice throws falling of tables, inaccurate interpretation of game rules and so on.

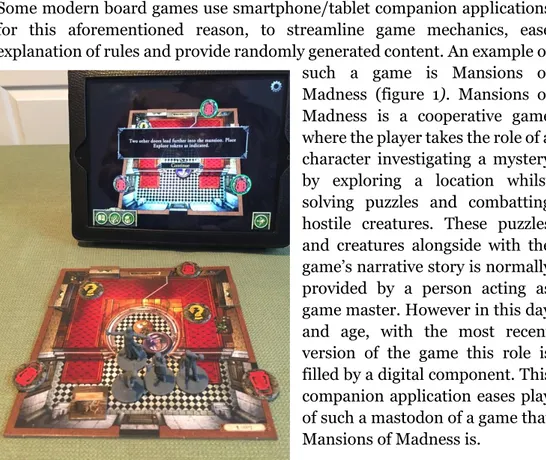

Some modern board games use smartphone/tablet companion applications for this aforementioned reason, to streamline game mechanics, ease explanation of rules and provide randomly generated content. An example of such a game is Mansions of Madness (figure 1). Mansions of Madness is a cooperative game where the player takes the role of a character investigating a mystery by exploring a location whilst solving puzzles and combatting hostile creatures. These puzzles and creatures alongside with the game’s narrative story is normally provided by a person acting as game master. However in this day and age, with the most recent version of the game this role is filled by a digital component. This companion application eases play of such a mastodon of a game that Mansions of Madness is.

Figure 1. Set up of Mansions of Madness with companion app. Reprinted from “The Board

Game Family”, 2017, Retrieved from https://www.theboardgamefamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/MansionsMadness_Setup.jpg

Oracles Game: Civil War (figure 2) is an unknown, yet unique board game that recently concluded a failed crowd funding campaign. It is an interesting case where the creators clearly state their goal to create what they call a “hybrid board game”; a game composed of a traditional board game with physical artefacts and HMD-AR. Reasons to why this project failed is purely speculation at this point but I believe that my work can shed light on some of the factors from a designers perspective. It is seemed not to be constructed with delicacy or too much thought, it is simply a board game with tacked on AR to facilitate for computer graphics and sensory amazement.

This contributes to a conflict between the two mediums; who is this game for? AR-enthusiasts or board game players? The large focus on digital components might seem intimidating for board game players and at the same time persons intrigued by the AR can see the board game and all its components as unnecessary.

Figure 2. Oracles Game: Civil War board game illustration. Reprinted from “Oracles Game

Inc.”, 2018, Retrieved from https://oraclesgame.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/gameset-1.jpg.

2.3 Immersion in gaming

Defining immersion can be challenging. Immersion can not be taken for granted and different players can be immersed in different ways, as by the strategy of a game or perhaps by the theme or mythos; but in a broader sense immersion is “a state of involvement experienced by players” (Brown & Cairns, 2004).

2.3.1 Three levels of immersion

Immersion as defined by Brown and Cairns (2004) and in regard to digital gaming, is used to describe the degree of involvement that a player has with a game. Brown and Cairns mentions three levels of immersion: engagement, engrossment and total immersion. Each level is controlled by barriers that can only be unlocked over time and when met by different criteria and breaking down a barrier does not guarantee the next level of immersion but simply allows for it. Some criteria are user controlled, such as concentration, while some are met by the game and its gameplay.

In order for a player to enter the first level: engagement, the player needs to invest time, effort and attention. Basically, an interest for the game needs to be present. This is something that is taken for granted throughout the thesis as the focus group consists of “players of board games” and here is no attempt trying to transform non-players into players.

The second level of immersion, engrossment, can then only be achieved by players of board games; and it is here, possibly, one can start differentiating

well-constructed board games from less so, as the engaged player willingly spends more and more time with game until ultimately becoming engrossed. The MDA-framework (Mechanics Dynamics Aesthetics) presented by Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubek (2004) is a tool used to analyse and understand games, describing the correlation between components of which a game consists. A game designer decides how their game should work by setting rules, and in doing so consequently creating mechanics. These theoretical mechanics in-turn generate dynamics when they are carried out in real life while the game is being played by players; dynamics are mechanics in-action. The third component, aesthetics, describes the parts of the dynamics which are experienced by the player while playing the game; for example: challenge and fantasy. In other words, the parts that make a particular game interesting and creates appeal for players. An example from Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubek (2004) describes when breaking down the games Quake and Charades, that these games are competitive and therefore require support of adversarial play (clear winning objectives, be able to see who is winning and who is losing) in order to get player emotionally invested. Thus, a player becomes engrossed when game dynamics start effecting players emotions by aesthetics or “visuals, interesting tasks, and plot” (Brown & Cairns, 2004).

The third level of immersion, total immersion, is a fleeting sensation briefly experienced by players in particular moments of the game where the world around disappears and the game, its world and outcomes are the only aspects that matter and as such often invokes powerful emotional stimulation in the player. An example of total immersion can be a jump scare within a digital horror game, where the player is so focused on the game that a happening within the game provokes a real-life physical reaction such as a jump and perhaps a scream out of fear.

2.3.2 The SCI-model

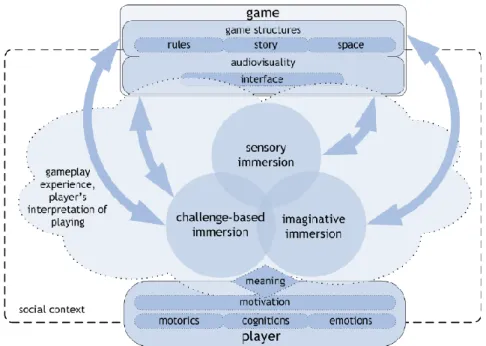

The SCI-model (figure 3) presented by Emri and Mäyrä (2005) breaks down immersion into three different modes: sensory, challenge-based and imaginative.

The sensory immersion is tied to a game’s audiovisual layer. This layer can be considered most important to digital games as such modern games are graphically very impressive and along with sound “

overpower the sensory

information coming from the real world” (Ermi & M

äryä, 2005) so that theplayer becomes focused on the game, thus immersion is increased. For a board game the audiovisual aspects relate to the art of the game and has strong bonds with the imaginative immersion mode. For example, high quality figures and a highly detailed gameboard allows players to inspect and observe these components to a greater degree, compared to if they would be

of low or abstract quality, increasing time spend with the game and thus become more immersed.

The second layer of immersion is the challenge-based one, which is crucial to all games considering games are interaction-based entities. Challenge-based immersion increases from “a satisfying balance of challenges and abilities”

(Ermi & M

äryä, 2005), not unsimilar to concepts of Flow theory (Mirvis &Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). Challenges are often tied to strategy, problem solving, mental and motor skills. Chess is a good example of a board game where challenge-based immersion plays a big role. Players of chess might not care to much of the fidelity of the game pieces or the gameboard, they are simply immersed in the tactics and skills required to play and win the game. The imaginative immersion layer is based on a game’s world, characters and story; allowing the player’s use of imagination, becoming absorbed in a story or starting to identify/empathise with characters. Imagine a board game that is set in a medieval fantasy setting has its gameboard decorated with a stylised map, game pieces in the forms of wizards and knights and game mechanics includes casting spells, travelling exploring uncharted lands. If you for starters do not even recognise half of the terminology mentioned above, playing this game is clearly not an immersive experience for you. However fans of fantasy settings will be allowed to immerse themselves into this world, take the role of a wizard and slay the dragon. This speaks to the imaginative aspect of immersion.

The aspects of immersion are all relevant but each one speaks to different types of players. Therefore is it important for a designer to note what type of game that is designed and what one’s target group is when allocating resources.

2.3.3 Relevance to Board Games

Playing a game, either digital or on a board, the game creates an experience for the player (player experience) and there, undeniably, is a connection between the two. Research regarding immersion is primarily based on digital games which must be considered when applying concepts and models described in these writings.

The three levels of immersion explained by Brown and Cairns (2004) is relevant by describing the necessary elements required in order for a player to become engrossed. It is here the impact of game theme, mechanics, challenges, setting etc. draws the player in to

The SCI-model can be seen as an additional dimension where it is possible to isolate specific aspects of immersion through which the player can become engrossed.

Not all theory of digital game immersion is applicable to board games; however, aspects regarding challenge and imagination are applicable since these core elements are present in both digital and board games; whereas the sensory aspect with its primary focus on audiovisual experiences are encountered to a greater extent in digital games. Some sensory immersion can possibly become relevant as an AR component (smartphone) of a board game can provide the means necessary to generate audiovisual content for the player.

It is worth mentioning the work of Gordon Calleja presented in his book “In-game” (2011) and his research on immersion in digital games. Based on the aforementioned “Three Levels of Immersion” and the SCI-model, Calleja coins the term incorporation as a metaphor to be used in the stead of immersion along with the introduction of the “Player Involvement Model” which can be seen as a combined and refined model of the earlier two. There are dimensions of his model that are relevant to board games which can be looked at too better understand the elements for supporting immersion during a play session. However, with his primary focus being virtual environments of digital games and “meta-involvement”, elements of a game that outside play sessions enhance immersion, I will not utilise his model in this project since the focus is board games and immersion during play. It is with these frameworks if you will, the investigation of AR applicability to board games will be carried out. These frameworks will throughout the project represent the requirements needed in order for an AR component to increase the positive player experience by immersion during gameplay.

3 Methods

Board games are complex contraptions played by a variety of different types of people and experienced differently by each individual. The research methods used in the project are user-centric and common practice within Interaction Design, chosen in order to generate qualitative data to get insights relating to users and their experiences while playing board games.

3.1 Interviews

In order to get a good understanding of the topic at hand interviews are a must;

“No matter what the research, there are two things you’re always going to be doing: looking for people who will give you the best feedback and asking them questions.” (Kuniavsky, 2003)

Recruiting and interviewing are two elements present in every research project. Recruiting is of obvious reasons necessary to get a hold of relevant people to ask questions regarding the work carried out and can be seen as a process to also figure out one’s target audience. In this project the target audience were that of people who play board games, and regarding the inclusion of phone AR there was also a relevance to target a younger age group (20-35). This refinement was further established for time’s sake and accessibility. Goodman et al. (2012) describes recruiting more thoroughly and lays out the process as carried out in its most professional and also most time-consuming form. For the latter reason and my own experiences with and knowledge of board game players, a full-fledged recruitment process was not conducted.

Interviews are present in most research and can fulfil different goals depending on the need of the researcher and current stage of the project. Early on in the process it can be used by the researcher to better understand and gain knowledge of the topic at hand. Later on, interviews can serve as an evaluation and a way to gain insights regarding conducted exercises, such as play sessions, workshops and their outcome. The interviews carried out during this project were mainly of the unstructured and semi-structured kind.

The unstructured interviews were very open and took place during and after exercises such as play sessions. Because of the open-ness of these interviews they can be likened with normal conversation with a specified topic. Questions were spontaneously generated during the course of the interview related to actions and observations taking place during play. After the play sessions semi-structured interviews were carried out.

3.2 Prototyping

Prototyping is an essential tool for the designer, whether designing digital interactive experiences or physical artefacts. In regard to interaction design prototyping is a tool used in order to iterate and explore design ideas. It can be quick and simply made paper prototypes to evaluate a user interface or a piece of wood, carved in a certain way in order to try out physical properties of an object; further, a simple web page with interactive elements such as buttons can be seen as a basic digital prototype which can be used to evaluate the layout of a user interface.

The earlier on you are in the design process the more economical you have to be with your prototypes (Lim, Stolterman, & Tenenberg, 2008). It is unnecessary to spend much time prototyping a design which is not to be final. As mentioned by Houde and Hill (1997) it is also important to consider what aspects of the design you are prototyping, what role does the prototype have and which questions are to be answered? Answering those question will make it possible to design prototypes well-suited for a specific purpose. When prototyping in this project this was of most importance and with the help of previous mentioned SCI-model, different prototypes could be easier categorised. Since the aspects evaluated not always was the AR itself, rather its role, it was often possible to make use of simpler, low-fidelity prototypes.

3.2.1 Wizard of Oz

The Wizard of Oz technique is a method of building cheap and convincing prototypes by faking the functionality of said prototype in such a way so that the test user can experience a supposed working system or product. The goal here is to be economical and time efficient so that the results of the user testing is valid and can be applied to future iterations of prototypes.

“Generally the last thing that you should do when beginning to design an interactive system is write code.” (Buxton, 2007, p. 240)

Imagine a designer testing a new type of TV remote in the shape of a ball. The TV user is given a plastic ball with no digital components and is asked to turn the TV on. The user squeezes the plastic ball and as the user does so the designer turns on the TV using the real remote unknowingly to the user. This is a Wizard of Oz prototyping approach; simulating a functioning artefact out of a lesser functioning one. Supposedly unknowing to the user.

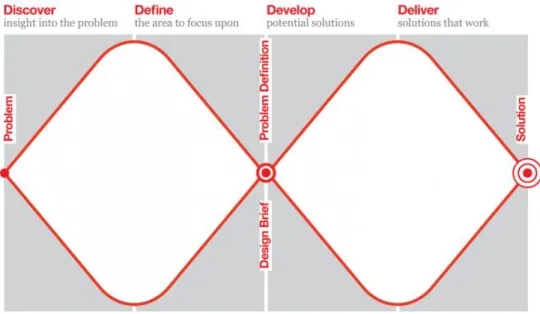

3.3 The Double Diamond

Over the course of the project the Double Diamond (figure 4) model was used. It is a theoretical design process model introduced by Design Council (2005) used by designers as a structural frame to their work during a project. The model is divided into four different phases or parts: discover, develop, define

and deliver; each of the phases focus on either diverging or converging thinking.

It was chosen in order to give the project a basic outline and map the future work process of my work. It has also been the most prominent model of use during previous undergone design processes; therefore, a sense of familiarity was another reason for the choosing of the Double Diamond.

Figure 4. Illustration of the Double Diamond model. Reprinted from “Design Counsil”, 2015,

Retrieved from https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/design-process-what-double-diamond

3.3.1 Discover

In the first phase of the model the researcher gathers insights and gain understanding of the chosen topic and all its elements; increasing the knowledge of relevant technology, look up prior research made, empathising with users and their role, are important parts of this phase.

Here is where the majority of literature studies are made by reading up on existing relevant subjects, in this case for example: AR and board games. It is also where quantitative data from interviewing board games players can lay a good foundation and let the designer gain insight in the field set out to study. For example, generally observe current AR technologies available and how to properly approach these with board games and its players in mind.

3.3.2 Define

In the define stage I set out to isolate and decide on the most interesting finds from the previous phase. It is here the creation of a design brief is undertaken, and taking into account the project time frame, personal skills and other requirements, I had to realise the most feasible course of actions.

There are different ways to define and focus direction of the project. Through various exercises such as creating affinity diagrams and forming “How might we”-questions based on the gathered data it is possible to converge and sift away unwanted data to make one’s goal more clear.

3.3.3 Develop

This is the stage of the double diamond where the researcher once more diverges, now in a more precise manner having developed a pitch or a “how might we”-question. Previous stages can be seen as the period where the designer gets acquainted with the topic. Now the development of final concepts starts and the designer prototypes and iterates on ideas generated in order to sift out possible solutions to later refine.

3.3.4 Deliver

In this final phase the designer narrows down for the last time and draw upon all knowledge previously gained to able to finalise a concept and, in some cases, deliver a product. In such case the product should be of high fidelity and closely resemble the imagined complete product. However, the phase is still iterative and by subjecting one’s target group with high fidelity prototypes it is still possible to polish and improve one last time (Design Council, 2005).

4 Process

The process took place over four main phases, each phase representing one part of the Double Diamond. I will describe my process as it unfolded over the past months. I started with the topic of AR enhanced board games with which I started prototyping early after studying related work and literature. The prototyping continued throughout the process in conjunction with play sessions for each prototype.

Initially the schedule was set so that I concluded my prototyping in mid-April. However complications with the prototyping altered that initial timeframe which I adapted to by altering my methods.

The Double Diamond was not strictly followed but worked as a regulator, nudging me in the right direction at times and was the basic structure that the project was guided by.

4.1 First phase

There are several aspects of a board game that are approachable with AR in mind, such as: social aspects, game mechanics, game pieces and so on.

Deciding how and where to utilise this technology required further exploration of board games. It was here Prototype 1 and the first play session took place. The prototype was an application made in the game development platform Unity along with the Vuforia Engine for Unity, run on an Android mobile device and worked in such a way that it with a phone camera recognised playing cards from the board game named Age of War and started to play a video inside the card for the player to watch.

Early iterations of the prototype focused on social interactions and conflict, incidents that burst the bubble so to speak and took focus from the game, slowing down playtime and making the game less enjoyable to play. The thought was that the AR component were to simplify and making it easier the play the game by reducing ambiguities along with providing audiovisual content for sensory stimulation. Nilsen, Linston and Looser (2004) mentions this as one argument for the use of AR in games and refers to these occurrences as ambiguous elements:

“Game conflict is resolved through a set of rules that usually calls for dice to randomize results, and decisions by consensus to resolve ambiguous situations. The resolution of these ambiguities can sometimes be contentious, particularly among younger players, and often leads to ill feelings and reduced enjoyment of the game. Thus it is desirable to eliminate these ambiguities where possible.” (Nilsen, Linton & Looser, 2004, p. 5)

A second game named Warring States (a game created by me and three other fellow students during fall 2018 at Malmö University) was also used as a foundation for prototypes. It was deemed fitting because the game already incorporated a digital component with accompanied mechanics which could be used to branch out and be transformed into an AR one. Utilising Warring States allowed for an economical approach to prototype, especially in the early stages.

Prototype 1 (figure 5) used a Wizard of Oz approach while playing Age of War with modified rules. Rolling dice that resulted in three swords would let the player partially capture the region of choice by placing that many swords onto the region card with corresponding sword icons. Let us say a region card has seven sword icons, if three swords icons are rolled on the dice the player is 3/7th on their way capturing it. With the normal ruleset a region cannot be captured until all icons on a region card has been filled with dice (seven out of seven in aforementioned example) with matching icons. However, the modified rules allowed players to gamble and issue an attack even though not all icons were matched, resulting in a reduced chance of capturing a region. This is where the AR component came into play. If an attack was issued a video clip of a battle played when the phone was locked on to a region card, simulating the attack taking place. While the player looked at the clip, I acting as game master (overlooking the game session) rolled dice in order to

produce an outcome of the battle and reported it to the players by sending a text message to their phone with the line “Victory” or “Defeat”. This prototype focused on providing audiovisual content as well reducing some ambiguous elements by letting the prototype supposedly take care of further dice rolling as would be required with the modified ruleset.

Figure 5. Prototype 1

Prototype 2 (figure 6) examined mechanics incorporating hidden information within board games and players interaction with it and each other. Looking through a simulated AR device aimed at the gameboard a player could perform several actions each turn: move troops, place troops and spy (be able to see the troop strength of an opponent’s tile). These actions were performed by a dedicated web application. The tension created by these hidden actions was discussed in interviews following the play session to be fitting to the theme of the game and was observed to generate tension and afford interaction between the players. It was mentioned that some players felt a light notion of paranoia when playing in multiplayer sessions with more than two players. The players were unsure of who to trust and betray. Alliances were formed by players pinching another players troops with their own, creating advantaging situations just for a player to later be attacked by their supposed ally on a tile where they had a low number of troops which had been revealed to the betraying ally by a spying action. This scenario, along with one other, was a common occurrence during the play session. The second was that of a similar scenario, however, the alliance between two players lasted longer and it managed to eliminate their opponent, leading to a fight for victory between the two recently allied players.

Figure 6. Warring States as used with Prototype 2

4.2 Second phase

Ambiguous elements as mentioned by Nilsen et al. (2004) showed to be apparent in both prototypes. The initial idea was to reduce ambiguous game elements with the help of AR; however AR brings its own problems. Instead of having dice roll of the table or unclear rule books the AR device used were sometimes slow in recognising images and displaying video. This led to the player believe the prototype was not working, changing the angle of the device to look at the screen and therefore cancelling its “read”, leading to frustration and unenjoyable moments. Also, dice and other physical pieces proved to be increasing the enjoyment of the board game to some degree; this was explained by players in the interview post play session describing that the lack of physical components in their mind somewhat reduced the games’ statuses as board games.

A realisation was made when analysing the early prototypes and data gathered from the play sessions. Instead of trying to make a game more enjoyable by reducing an aspect (ambiguous elements) and indirectly get a positive effect on the gameplay or add audiovisual content with no real meaning, it would be better to directly impact the gameplay through mechanics and actions by utilising the AR device’s affordances such as the tensions encountered while playing Prototype 2. It was noted that the passive player (the player who is waiting for their turn) was interested in what the current player was looking at through the AR device. This created some of the tension mentioned and expectation in the players which in a way contributed

to players spending more time and staying interested with the game, leading a more immersive experience and tendencies towards engrossment. However, there was a concern raised regarding screen time based on interviews conducted post game session.

Immersion became the keyword, a word generally used in a positive sense in game related literature and articles to describe player experience and player enjoyment of a game. However, the word immersion was still somewhat undefined, fluffy if you will, and used in different ways by different authors. Further research was made in order to make sense of the word and create a form of framework for future work and prototypes to be based upon. The final How Might We-question and main topic for this project was made clear: “How might we support immersion in board games for experienced players with the use of phone-based AR?”

4.3 Third phase

Having defined the term immersion with the work of Cairns and Brown (2004) and Ermi and Mäyrä (2005) it could be seen as a very broad term, at its most basic level described as a quality of a game which makes a player spend time and thought with the game, letting go of the real world. But to be able to support for immersion one needs to break down the term into “hows” and “whys” as aforementioned authors have done.

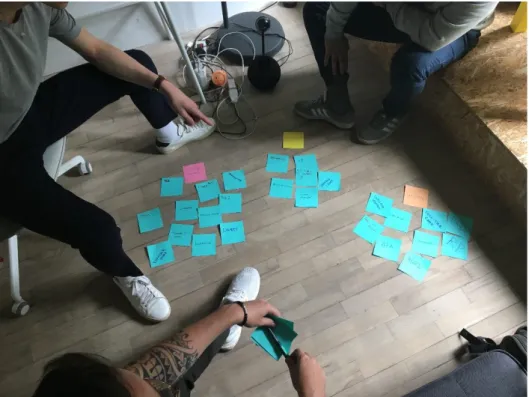

In order to get a better understanding of immersion and what it meant for my specific target users I organised a workshop (figure 7). I recruited three persons for an unstructured interview and a simple sorting exercise, all recruits were experienced board game players. I asked the question “What are activities or artefacts that you find immersive?” and then letting each participant write down keywords on paper notes. Immersion was not defined prior to the writing, letting everyone write down whatever they felt associated with the term at that moment without a set definition clouding their thoughts. After a period of time everyone placed their keywords on the floor, and I explained the concept of the SCI-framework. The participants then proceeded to categorise their keywords under Sensory, Challenge or Imaginary categories, placing a keyword in the category they felt most suitable and was considered the primary immersion factor for them while engaged with that particular activity or artefact. For example, “Chess” was placed under the challenge category by one participant and this was agreed upon by all three. However, the placement of “DOTA 2” (a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena, a.k.a. MOBA game where teams of five face each other in battle with each player controlling a unique in-game character) was argued between two participants. Participant 1 wanted to place DOTA 2 under the challenge-category while Participant 2 wanted to place it under the imaginary-challenge-category. Even though it was agreed by the two that challenge played a major part of the immersion, Participant 2 placed somewhat more emphasis on the imaginary aspect as he put more weight on the decision of which character to

play, based on who he wanted to represent in the game world; minor role-playing in a sense. Participant 1 instead picked a character based on the challenge presented, he wanted to win over all else and it didn’t matter what kind of character he played as long as its abilities fitted the team composition and increased their chance of winning. This exercise showed that different players get engaged and engrossed by different factors and displayed that games which affords for several types of immersion supposedly can target a broader audience of players.

Figure 7. Workshop during sorting exercise

The workshop led me to further iterate on Prototype 2, leading to Prototype 3. The idea was to transfer the functionality of the web-application into Unity and Vuforia and make Warring States playable with a true AR component instead of the web-based one, which in turn supposedly would support additional immersive elements by utilising the capabilities that AR affords; such as graphic overlays and audiovisual effects of higher fidelity which the web-application would not be able to generate. Working on Prototype 3 caused setbacks as the programming-needs necessary to complete the desired AR application proved to be substantially greater than first thought. Prototype 3 therefore became a simpler version of what was originally intended, using a similar approach as Prototype 1. It automatically displayed a number over a specific tile on the Warring States gameboard when a player aimed their phone at it. However, after a short time testing Prototype 3 it encountered the same scenario that evolved from Prototype 2 regarding screen time. Even though it made possible for greater immersive content it hinted towards the gameboard becoming close to obsolete; and if such is the case, the realm of board games is left behind, a realm within which I intend

to stay. A different strategy was needed to solve this newly encountered problem. I needed to find a different role for the AR in this particular case and not just create a nicer version of the already existing concept.

This was a turning point in project. Instead of having an AR component of high fidelity to work with and try out different immersive aspects as I first set out to do, it became evident that before spending time and effort into developing such an application it was first necessary to find a place for the AR component within Warring States. Trying to find this place with a high-fidelity AR component goes against the very basics of prototyping. The role of the prototype had been neglected and I realised that I had committed to a concept which was not supporting the game in a satisfying way and did not work well in combination with the physical board game. I needed to take a more economical approach to my prototyping (Houde & Hill, 1997; Lim et al., 2008).

The next play session consisted of three different prototypes, all utilising the web-application. Here an attempt was made to observe the amount of immersion between different versions of Warring States. Each version incorporating a varying use amount of simulated AR in order to establish a “base version”, as immersive as possible, for future prototypes to be influenced by.

The three version were:

Normal rules with web-application in phone – Further play sessions were carried out with the normal rule set to validate findings of the prior. It was shown that the passive players were interested in active players actions. However there was much screen time, true to previous observations, and a majority of active time was spent looking at the phone since all actions needed phone usage. Therefore it became commonplace that the active player looked at their phone and tensions wore off and as a result the gameboard became barely used. The phone also restricted players movement to a degree. In a way the phone and physical gameboard and pieces fought for attention. A scenario commonly encountered: player pick up phone to complete actions, put down phone, move pieces on gameboard; player forgetting how many troops there was in one of their tiles, make hands available and pick up phone; repeat. A dynamic that was not well received. Players mostly became engaged with the AR component but as soon they had to engage with the physical gameboard the overall engagement decreased. The physical components and the AR component did not work well with each other, time and focus were divided between the two, hindering players to become engrossed.

Digital with web-application in phone only – This version was only played with the digital application (figure 8) and combat was solved by rolling a digital die on the phone. Players talked less and with no use of a gameboard and no physical pieces the board game aspect disappears for obvious reasons. In board games the gameboard works as the meeting point for players where

upon they interact and which It was in this case explicitly disregarded in order to see what strengths and weaknesses the AR component could carry. The purely digital version did afford better engagement compared to the normal version, allowing the players to focus on one component, but it did also isolate the players up to the point where there was no interaction between players at all; which is contradicting to the fundamentals of board gaming.

Figure 8. Warring States web-application

Modified rules with web-application in phone – This version was played with modified rules of the base game and use of additional physical game pieces along with less hidden information. Actions that in the normal version required the phone is now carried out placing physical game pieces on the board and moving them. The phone is used for a new mechanic called “exploring”. Exploring tiles enabled the player to see how much resources a tile had, resources were then used to get more troops (instead of occupying more land as in the normal version). Resources should supposedly in later versions be randomly generated for each playthrough, however, in the remain play sessions of this project a Wizard of Oz approach was used with the amount of resources hardcoded into the application. Exploring costs action points, so the phone is not necessarily used each round. This resulted in players interacting more with each other as they used the gameboard more and phone use was decreased. However, since the phone is only used for exploring it was argued that this version was just one additional physical game piece from becoming a pure board game, just as playable as the AR-enhanced version. A valid argument, but now when a better balance between screen time and board time had been found, future iterations of this version were to examine what the AR could afford in terms of aesthetics and immersive qualities that physical pieces could not.

4.4 Fourth phase

Analysing the most recent play session and based on interviews following it I concluded that the Modified version of Warring States showed most promise. This version was brought to life with a seemingly minor change to the games rules and mechanics that brought Warring States closer to its board game roots while simultaneously left room for the use of the AR component in a limited manner; which allowed players to stay engaged with the game as a whole over a long period of time without attention being split between physical and AR elements; granting more satisfying dynamics than the Normal version. Now that a suitable spot for the AR component had been found I moved on to transform Prototype 3 to work with this new version of Warring States as a starting point to build upon and introduce additional immersive qualities.

A new play session took place where I and one other participant played against each other with Prototype 3.5. The new prototype proved to work well with the new ruleset of Warring States with a better balance between physical and AR components, the AR showed to be better appreciated in the smaller bursts of usage. The participant, which had been part of an earlier play session, expressed that it “felt more like a board game” (Anonymous, 2019) when compared to the Normal version of Warring States as he now interacted more with the physical components than previously, which confirmed previous findings. The next step was to take greater advantage of the AR and increase the fidelity of the prototype. Taking into account the setting and theme of Warring States I decided to try better thematically match the AR component with the physical components as a step towards a more visually and imaginary engaging experience.

Figure 9. Prototype 4 with AR coin pile representing resources of the tile. A low-fidelity

gameboard was also used with icons within each tile to allow easier tracking for the AR component.

The next iteration, Prototype 4, replaced the number-visualisation over tiles with a golden coin texture (figure 9). When the active player aimed the AR component at a tile a certain amount of coins hovered over that tile indicating the amount of resources the tile contained. With this I organised a final play session with the same participants that had been involved in the previous in order to be able to evaluate the outcome and feedback in a comparing manner. This play sessions consisted of two playthroughs of Warring States, one with Prototype 3.5 and one with Prototype 4. I conducted an unstructured interview after the session with the participants where I asked them to compare the experiences between the two playthroughs. The feedback proved that the AR had been able to provide small yet satisfactory visual and imaginary aspects to Warring States. Simply by replacing the numbers with coins, the visual and imaginary immersion increased by a small amount. Even though it was expressed that the coins at first were somewhat more difficult to interpret than regular numbers, after a short time playing the participants could as easily distinguish the amount of resources gained with help of the coins as they had with the number-visualisation. This led to an overall improved experience for two out of three participants, whereas the remainder still preferred the number-visualisation out of pure clarity. A problem regarding selecting specific tiles arose and if future iterations were to be made this is the first usability issue to be tackled. For a solution to this a variation with an AR-button for selecting tiles started development. However, when considering the timeframe within it had to be completed along with additional play sessions needed to evaluate a new prototype and the possible need of further research concerning interactions with AR-artefacts, the development of supposed Prototype 5 was halted and Prototype 4 became the final of the project.

5 Final thoughts

5.1 Discussion

With the target group being experienced board game players with access to smartphones and the so often expensive modern board games it must be stated it is somewhat of a privileged target group. Further work could investigate the reduction of production costs of board games which utilises phone-based AR. With the smartphone being a somewhat common artefact today with wide usage worldwide it could be interesting to see if the cost of more complex board games can be reduced. It is also worth noting with the existing concern regarding surveillance and personal data, the forced introduction of a digital artefact into the personal gathering of a board game play session might be disliked by some.

In the normal version of Warring States all players were inclined to use the digital component in the majority of action taken. This meant players could be watching their screens at all time, perhaps browsing Youtube mid gameplay, it wouldn’t be known what the current activity of the player was. With Prototype 3 the spying mechanic in the normal version of Warring States became somewhat more concentrated and clearly stated, and the outcome of the move was still ambiguous enough to keep opposing players unknown to the fact of which player that had been spied upon. This could be likened with perhaps the paranoid thoughts of a long-gone emperor, “I know there is a spy among my servants, but where?” but perhaps there wasn’t, the player who spied did so on another player. This was a dynamic that continued to serve as motivation and argument for the use of AR throughout the project, later evolving into the explore mechanic.

At one point in the project there was a realisation that utilising AR in many of the board games mechanics caused harm to the board gaming aspect. If designing a solution for a stakeholder a designer might have in this situation revaluated their position and resources and scrapped the board game aspect and proposed a digital concept instead. One could question if the presence of a physical board game was somewhat forced at this point. Deciding whether to continue using the board game medium or instead convert the game into a digital concept, where the player can focus on their screen fully and become further immersed in the high audiovisual fidelity that is afforded by modern mobile CPUs depends on the task at hand. Breaking up the need for attention between the physical board game and the AR component can be seen to reduce immersion. There is a certain delicate design space where board games and AR can meet, and more complex technological solutions needs to be introduced in order to further evaluate the outcome of the marriage. Later changes to the rules of Warring States showed promise by reducing the use of the AR component and put emphasis on the physical elements of the board game. Screen time was reduced but the AR still contributed with its computational prowess in shorter more meaningful bursts of usage.

Other board games that utilises digital components often does so in a supplementary way. The digital component (usually a phone or tablet) is simply by the side, providing events, text, ques to the player but is never an active part of the gameplay. This mixture of providing an extra layer of complexity without complicating the board game with even more physical parts and at the same time allowing for physical player actions that contributes to the aesthetics of the game.

5.2 Conclusion

Two early prototypes showed that AR does not replace dice and physical pieces in an existing game and should not be forced to provide audiovisual content, it is just an extra, cumbersome step for the player to look at that content; fascinating at first but not in the long run. It can however, if made to

fit the theme of the game add another type of rules and mechanics that can be difficult to implement with physical pieces in certain more complex board games that in some cases have an extreme amount of tokens, figures, cards and other accessories.

Interesting yet complex mechanics of board games can be used to greater effect with the addition of an AR component if the board game, from an early stage, is designed with an AR element in mind. This AR component also affords improved immersion for players when implemented properly. Carrying out the spying action in Warring States would be very cumbersome in a fully analogue board game since the number of troops hidden “within” the tiles are forever changing. Imagine: a hidden token under a terrain square which shows current troops there. On top of that terrain square another token to show who owns the terrain. In order for a player to spy the player has to remove the owner-token, carefully lift the terrain square to not show anyone else how many troops there are and then revert the actions. Same goes for the owning player if he wants to move troops from a terrain square to another. And on top of that, the player moving troops has to take careful notes of where all his troops are, noting -1 troop there, +1 troop here and so on. A nightmare, a board game practically unplayable. This was made playable with the addition of a digital component. The process overall ended being more of a theoretical and explorative nature than a pure design focused one. No final high-fidelity prototype was produced; instead the frequent use of low-fidelity prototypes during the whole course of the project proved to serve the process well in this instance.

The opportunities a digital AR component affords are not to be underestimated. Therefore if designing a board game with such a component the designer must take into careful consideration what type of AR device that is to be used and not to disregard the board game itself and its properties. A well-developed AR component could display incredible graphics with designed in-game characters and effects which engrosses players in a sensory and imaginary approach. But having predetermined design on characters, spells and other in game objects could also in a sense reduce the players imaginary possibilities as assets are predetermined and locked into looking a specific way. Therefore, when designing a board game and the use of AR is considered, one must take into account the different strengths and weaknesses brought by the several components of and design thereafter so that the AR does not purely exist to quench the thirst of technological marvely.

References

Board Game | Definition of Board Game by Merriam-Webster. (2019). Retrieved May 14, 2019, from

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/board game

Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A Grounded Investigation of Game Immersion. Retrieved from

http://delivery.acm.org.proxy.mau.se/10.1145/990000/986048/p129 7-brown.pdf?ip=195.178.227.49&id=986048&acc=ACTIVE

SERVICE&key=74F7687761D7AE37.12F0E157C416AD84.4D4702B0C 3E38B35.4D4702B0C3E38B35&__acm__=1552640960_4ea608fcd2 cf0175792a18cf3af8ca18#URLTOKEN%25

Buxton, B. (2007). Sketching User Expirience. In Morgan Kaufman (Vol. 1). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Calleja, G. (2011). In-Game. Retrieved from

https://is.muni.cz/el/1421/podzim2016/IM082/Gordon_Calleja-In-

Game__From_Immersion_to_Incorporation_- MIT_Press__2011_.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1oN-j2EgECAK-3xOZbs0i66JzCVdUajN5G_xHqYn7sq8oPuNYfJNTgYM4

Design Council. (2005). Eleven lessons: managing design in eleven global brands. A Study of the Design Process. Design Council, 44(0), 1–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

Duffy, O. (2014). Board games’ golden age: sociable, brilliant and driven by the internet | Technology | The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/nov/25/board-games-internet-playstation-xbox

Ermi, L., & Mäyrä, F. (2005). Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion. Retrieved from

http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/06276.41516.pdf

Houde, S., & Hill, C. (1997). Houde-Hill-1997.pdf. Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 367–381.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243916675954

Hunicke, Robin; LeBlanc, Marc; Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design And Game Research. Workshop on Challenges in Game AI, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1.1.79.4561 Kuniavsky, M. (2003). Observing the User Experience (interview).

Observing the User Experience, 419–437.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-155860923-5/50041-3

Lim, Y. K., Stolterman, E., & Tenenberg, J. (2008). The anatomy of prototypes: Prototypes as filters, prototypes as manifestations of design ideas. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 15(2), 1–27. Retrieved from

Mirvis, P. H., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. The Academy of Management Review, 16(3), 636. https://doi.org/10.2307/258925

Nilsen, T., Linton, S., & Looser, J. (2004). Motivations for augmented reality gaming. Proceedings of FUSE 4, (May), 86–93.

Piccione, P. A. (1980). In Search of the Meaning of Senet. 33, 55–58. Rosenberg, L. B (1992). The use of virtual fixtures as perseptual Overlays to

Enhance Operator Performance in Remote Environments. Technical Report AL-TR-0089, USAF Armstring Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB OH, 1992.