A Pound of Flesh But No Jot of Blood:

Maintaining relationships with devices as they migrate onto and

into our bodies.

Sarah Homewood

June 2015Supervisor – Susan Kozel

Examiner – Pelle Ehn

Examination date - 3

rdJune 2015

Abstract

Despite a strong commercial trend towards wearable technology, this thesis considers the distal devices that have played an important role in our lives for over twenty years. Suggesting that the distance we have had between our bodies and our devices has given us the space to form meaningful relationships; the research explores how these relationships change when our devices migrate onto and into our bodies in the form of wearable technologies. The methodology of performative scenarios is developed to examine examples of relationships between people and their devices. Using examples of technologies that live with us now to inform the design of future technological developments reflects a post-phenomenological perspective calling for a materially oriented design approach. This thesis will explore this approach through focusing on the question; what would we lose if our distal devices became wearable devices? Ideations aiming to prevent any loss caused by the transition of devices from distal to wearable will provide examples of post-phenomenological wearable technology that not only maintains our relationships with our devices, but also helps our relationships to grow.

Keywords

Performance, Interaction Design, Wearable Technology, Post-Phenomenology, Proxemics, Amoebic Self Theory.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Susan Kozel for her inspiration and

advice, Anna Navndrup, Ida Pettersson and Alice Homewood for their

practical advice and support and Lucy McRae and Unsworn Industries

for the permission to use their resources. I would also like to thank Sam,

Chez and Julia for sharing their stories with me.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Keywords

Acknowledgements

1. Introduction

1

2. The Research Question

2

2.1 Definition of key terms

2

3. Were Wearable Devices Inevitable?

3

3.1 Seeing technology as ourselves

3

3.2 Ubiquity and the Internet of Things

3

3.3 The commodification of the body

4

3.4 Verbeek’s Philosophy of Technological Artifacts

4

4. Measuring the Value of Distal Devices

6

4.1 Proxemics

6

4.2 Distal devices as evocative objects

7

4.3 Distal devices as engaging artifacts

7

5. Design Method

9

5.1 Jacucci’s Interaction as Performance

9

5.2 Performative scenarios

11

5.3 Relevant work

11

6. Discovered Performative Scenarios

13

6.1 Julia

13

6.1.1 First modification of Jacucci’s aspects of

physical interfaces

14

6.2 Chez

15

6.3 Sam

16

6.4 Implications of discovered performative scenarios

18

6.5 Second modification of Jacucci’s aspects of

physical interfaces

19

7. Designed Performative Scenarios - Distal Devices

21

7.1 The Spa

21

7.2 The Secretary

22

7.3.1 The Shrines

24

7.3.2 The Cradle

26

8. Designed Performative Scenarios - Wearable Devices

28

8.1 The Foetus

28

8.2 The Dependent

29

9. Conclusion

31

9.1 How did the aspects that define distal devices change

once the device was wearable?

31

9.2 What was the element that was seen to be lost in the

transition from distal devices to wearable devices?

31

9.3 Other aspects that can be taken away from this thesis

and possible further developments.

33

9.4. Final evaluation of the use of performative scenarios

to explore post-phenomenological perspectives

34

1. Introduction

In order to attempt to answer the research questions, this thesis will first explore possible reasons why technology is predicted to migrate onto and into our bodies, and whether this migration is due to an approach within the design of technology where technology is used to control the world around us. This thesis will employ Peter-Paul Verbeek’s book What Things Do (2005), which proposes that technology designed through the possibilities that the technology makes possible to us, rather than the material properties of the technological artifact itself, results in the production of technology that is not “engaging” (p.228). Verbeek uses the phenomenological philosopher Heidegger’s (Heidegger, 1977, cited in Verbeek, 2005) work as an example of an approach to technology that treats the world as a “standing reserve” (p.52), a raw material waiting to be controlled and commodified by technology. Verbeek’s alternative answer to treating the world as a “standing reserve” (p.52) is through designing “engaging artifacts” (p.228) through the application of a post-phenomenological perspective (p.112). “Engaging artifacts” (p.228) can mediate our interaction with the world rather than dominate. Post-phenomenology is a hybrid philosophy that encompasses the themes of embodiment and human activity central to traditional phenomenology but does not ask the phenomenological questions about the existence of an authentic reality. Post-phenomenology is concerned with our interactions with concrete artifacts in each of our worlds, and the meanings within these interactions. In the final chapter of What Things Do, Verbeek employs a post-phenomenological perspective to propose a new practice of industrial design. In the later stages of this thesis, Verbeek’s approach will be applied to interaction design in order to propose a possible future where wearable technology is designed from a post-phenomenological perspective.

The design method employed in this thesis will expand upon Giulio Jacucci’s

Interaction as performance (2004). Jacucci’s methods allow and encourage performative

expressions from the actor involved in the scenario by using the presence of a spectator and encouragement of intentional actions. This design method attempts to encompass not only the physical context of the scenario that influences the interactions between the actor and the technology but also the passing emotions of the actor. A post-phenomenological perspective will be applied to performative scenarios exploring existing relationships between people and their devices. These scenarios will be used to draw conclusions about the relationships between people and their devices. In order to explicitly answer the research question, these relationships will then be used to design possible future scenarios where the distal devices in the performative scenarios become wearable.

2. The Research Question(s)

What would we lose if our distal devices became wearable devices?

Can an alliance between aspects of performance studies, interaction design and post-phenomenological perspectives produce ideations of wearable technology that maintains the relationships that we have with our distal devices now?

2.1. Definition of Key Terms

Wearable devices: This thesis will define wearable devices as devices whose total function

and designed intention is only fulfilled when physically connected to the body. This connection could be subcutaneous, cutaneous, or attached to clothing that is worn by the body. The fact that a piece of clothing has pockets does not mean that objects that can fit into these pockets would necessarily be wearable devices. The key to the definition of wearable within this thesis is in the designed intention for the technology to be directly connected to the body either permanently or semi-permanently.

Distal devices: This thesis will concentrate on the technology that lives with us now. The

use of the term distal devices, rather than un-wearable devices, in the research question is an important distinction to note. The terms distal and un-wearable both refer to devices that are not designed to physically connect to our bodies. Distal devices, however, also refers to the more nuanced relationships we have with the devices in our lives and is related to proxemics (Hall, 1969), Sherry Turkle’s accounts of the relationships between people and objects (2007) and Peter-Paul Verbeek’s “engaging objects” (2005, p.228).

3. Were Wearable Devices Inevitable?

Since mobile phones and laptop computers were brought onto the commercial market over twenty years ago, they have become a fundamental part of many of our lives. They have lived and slept besides us, but so far they have not been physically attached to our bodies. This is predicted to change in the coming years:

“There will be eight times as many wearables in use by the end of 2018 as in 2015” (CB Insights - Blog, 2014)

These predictions are caused by, and in turn have caused, huge economic investments into the field of wearable technologies. This, alongside huge technological advancements in the battery life and size of wearable technologies, mean that there is, and will increasingly be, a flood of commercial wearable technology onto the market.

3.1. Seeing technology as ourselves

The fact that technology has migrated onto and into our bodies could be explained through the psychological Amoebic Self Theory (Burris, Rempel, 2004). Amoebic Self Theory studies our ability to determine our sense of self within the environment around us.

“to differentiate “in” from “out” is essential for survival. Differentiation is facilitated by a cell membrane among simple organisms and, among humans, by a psychologically analogous boundary that differentiates, contains, and protects the human self.” (p.4)

Amoebic Self Theory follows our desire to differentiate and protect across the three domains of self: the bodily, the spatial and the spatial-symbolic. As our reliance and relationship with our distal devices has grown stronger, we have come to recognize ourselves within our devices. For our devices to physically become part of us is an irresistible option, perhaps so that we do not have to navigate the spatial or spatial-symbolic domain, but only the bodily domain. It could be said that to wear our devices on or under the skin strengthens our outer boundaries that differentiate us from the not us and provides us with a way to centralize our resources. Perhaps this fits some dystopian notions that wearables will be increasingly popular because of paranoia. We no longer trust the environment around us enough to put our devices down.

3.2. Ubiquity and The Internet Of Things

For a large part of the young population, personal devices have been part of the way we have functioned and related to the world for all of our adult lives. Baudrillard (1988) describes our state of connectivity as a being like a Mobius strip “with its peculiar contiguity of near and far, inside and outside, object and subject within the same spiral.” This invisible connectivity could be described as an example of ubiquity. Mark Weiser is heralded as the father of ubiquitous computing (Ubiq.com, 2015).

The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it. (Weiser, 1991, p.78)

The term the Internet of Things, or I.O.T. is a contemporary term applied to the concepts within ubiquitous computing. Some concepts prophesied by Weiser in 1991 are now practically possible to implement in our lives due to the general accessibility of wireless internet and developments in sensory technologies. The term I.O.T. was coined by Kevin Ashton at a talk given at Proctor and Gamble in 1999 (Postscapes, 2015). The term refers to a situation where all objects and humans are connected to one another and data is collected from all of these connections. The tagline could be “anything that could be connected, will be connected” (Morgan, 2015). The increase of data collected by the I.O.T. could be seen as an example of humans trying to make the world quantifiable and therefore a source that can be gained from. The value of big data lies in its ability to show patterns of human behaviours. These patterns can then be used to target advertising, predict trends and to benefit many other commercial ventures (LOHR, 2012). The value of personal data produced by social media sites is already the source of income for many companies.

3.3. The commodification of the body

This thesis proposes that to have a valuable place inside the I.O.T., the body must show itself to be economically valuable. Wearable technology would harness this value in the body through the application of sensors that quantify movements and biological processes. This could be described as commodification (Kopytoff in Appadurai, 1986) From examining contemporary databases of existing and emerging wearable technologies (Pinterest.com, 2015), it is possible to categorize wearable technologies into having these goals:

- To economise actions

- To control and monitor the wellbeing of the body - To be status symbols

- To augment bodily senses and therefore the environment around it - To act as an armour and protective tissue.

These goals all turn the body into a commodity, wearable technology could be seen as trying to increase the value of our bodies. As discussed above, wearable technology increases the amount of quantified data produced by a body that can be profited upon. However, it could also be argued that wearables not only commodify our traceable actions and data, but also our flesh and bones themselves. When wearables are used, a transaction takes place where the raw material of the bodily senses and flesh are augmented in exchange for a heightened experience of the world.

3.4. Verbeek’s Philosophy of Technological Artifacts

This thesis will focus on technology that exists with us now. This approach reflects Peter-Paul Verbeek’s (2005) thoughts in his Philosophy of Technological Artifacts.1

Verbeek poses that there is more value in focusing on the technology that engages us materially now through their artifacts. Verbeek begins by criticizing a certain reading of Heidegger’s view of technology as a way of controlling and dominating reality as if

1 This thesis will follow Verbeek’s thoughts without unpacking them critically, though this could absolutely be done as a more

in-depth study. The range of philosophers cited in this chapter are used in order to give background to Verbeek’s suggestion for the implementation of post-phenomenological perspectives within design, and not a result of the author’s own philosophical perspectives.

it is raw material (Heidegger, 1977 cited in Verbeek, 2005 p. 47-95). The tendency to fail to see the actual material implementations of technology in our lives may be a reason for the assumed future where technology migrates onto and into our bodies. Verbeek also poses issues with phenomenological views of technology as a neutral tool that is used to achieve the user’s goals. Post-phenomenological theory focuses on analysing our interaction with technology and the world, and does not aim to define authentic reality itself. Thus a post-phenomenological perspective informed by Verbeek focuses on the agency of both technology and user to shape the world that is created by their interaction. “Mediation” (p. 114-116) is the verb that Verbeek coins to describe this agency of both user and technology.

The final chapter of What Things Do uses post-phenomenological theories from Don Ihde, Albert Borgmann and Bruno Latour to pose suggestions for Industrial Design that focuses on building the “meaningful” (p. 227) relationship between a product and a consumer. Tools for building these relationships are the use of “Engaging Artifacts” (p. 228). A further explanation of the traits that define an “engaging artifact” will follow in chapter 4.3.

4. Measuring the Value of Distal Devices

This chapter will first attempt to explore the definition of a distal device in order to answer the first research question What would we lose if our distal devices became wearable

devices? Research will be focused on the physical space between us and our distal

devices and whether this space allows three possible valuable affordances:

Proxemics: our expression of attitudes through our physical interactions with our distal devices. This relates to Edward Halls’ concept of Proxemics (1969).

Distal devices as Evocative Objects: fluid transformations in the meanings and characters that we see within our distal devices. The methods used in Sherry’s Turkle’s Evocative Objects (2007) will be implemented when exploring these meanings and characters.

Distal devices as Engaging Artifacts: as discussed at the end of the previous chapter, post-phenomenological perspectives can be implemented to design “engaging artifacts” (p.228). This chapter will propose that distal devices could relate to Verbeek’s notions of what constitute an “engaging artifact”.

4.1. Proxemics

The proximity that we normally have to our distal devices when they are in our bags, pockets and bedsides would be defined within proxemics as being within our “intimate space” (p.20). Proxemics defines “intimate space” as ranging from just in front of our noses to the length of an arm. In the mid twentieth century, the anthropologist Edward Hall coined the term Proxemics as one of the subcategories of the study of nonverbal communication to describe the analysis of our meaningful use of space in regards to others. In The Hidden Dimension (1966) Hall begins by stating that culture is a form of communication (p.1). Hall refers to the fact that culture is the statements we make through our navigation of space. Hall believes that the main trait that separates humans from animals is our ability to “extend” (p.4) our organisms through tools and the objects around us. Through our “extensions” we create another “cultural dimension” (p.5) where “man and his environment participate in molding each other” (p.5). Hall believes that our use of “extensions” can accelerates evolution and is the cause for a multitude of societal disasters, such as over-crowding in cities. Hall states that our “extensions are numb (and often dumb)” (p.188) and that a preventative measure to halt evolution travelling in the wrong direction would be to

Figure 1. An illustration of the three affordances that the physical space between our bodies and our distal devices allows.

build a “feedback system (research)” (p.188) into our extensions. This thesis will not assume that all devices within our “cultural dimensions” (p.5) are extensions of only our organisms. The term distal used in thesis is consistent with aspects of proxemics; however, distal devices can also represent other characters or objects and not only our sense of self. The proximity we keep between our bodies and our distal devices can be seen as an expression of our attitudes. For example the distance that someone is happy to keep their mobile phone away from their body could be read as illustrating how important it is for them to feel connected to others at that particular moment. This thesis does however perhaps situate itself as an interaction design example of a “feedback system” (p.188) that Hall calls for in the final chapters of The Hidden

Dimension. Though the research that will follow in this thesis will not outline the

equivalent of such precise social disasters that Hall believed needed to be prevented through research. This thesis’s aim to study proxemics within interaction design is one of the inspirations for the method of the Performative Scenario, introduced in chapter 5.

4.2. Distal devices as evocative objects

Sherry Turkle’s work (2007) explores our relationships and interactions with the materials that make up our world. She finds that they are informed by all of our life experiences and relationship models, and in turn the objects around us inform our relationships and experiences; “we think with the objects we love, and we love the objects we think with” (p.5). The book Evocative Objects; Things We Think With (2007) is a collection of first person accounts of individual’s relationships with their “evocative objects” (p.5).

Turkle’s work allows for analogous elements within relationships between people and their evocative objects to become evident through allowing her subjects to adopt a first person narrative and a speculative tone. The book is written for a broad rather than a scholarly audience, though many of Turkle’s accounts are from people within M.I.T., which gives the accounts certain academic groundings as the authors themselves provide many academic sources. Turkle writes the introduction where she provides her own example of an “evocative object”, and at the end of the book Turkle draws some conclusions based on some of the ideas within the personal accounts. This thesis will employ a developed version of Turkle’s methods that will be introduced at the beginning of chapter 6.

4.3 Distal devices as engaging artifacts

Products can be designed to invite engagement (p. 228) instead of being designed in terms of what they say as signs (Verbeek, 2005, p. 206). Objects that are signs can illustrate who we are and what we who we want to be seen as, but the objects that make up signs are interchangeable so long as they represented the same sign. Verbeek states that objects that act as signs are influenced by fashion and calls for the design of objects that sustain “durable relations” (p. 233) which relate to the relationships that this thesis posits are present between our distal devices and us. According to Verbeek’s final chapter in What things do (2005), the design of an “engaging artifact” can be achieved in three ways:

1. The use of transparency (p.126) in objects meaning that the user being able to fix it themselves when it breaks rather than remaining a “black box” that can only be

accessed and fixed by a third party. When a “black box” (p.158) object breaks the relationship between user and objects ends. Transparent objects allow another relationship to form through the act of repairing or maintaining the object.

Products that allow human participation in their functioning, or with their repair when they break down forge a bond between users and themselves as material things rather than simply as suppliers of commodities (p.230).

2. Engaging artifacts are those which “call attention to themselves” (p.230), but not enough to distract attention away from the situation they are within. These objects are designed to highlight any interactions with them that take place, and are not designed to just blend into the background.

These objects invite a broader sensorial relationship, which lets it be present as a material object. … Their presence to us is not exhausted by their functionality, for we remain involved with them as material objects (p.231)

3. Engaging artifacts are objects that age with us, and show wear from our involvements with them to make us aware of our history with them (p. 223).

This thesis will consider the application of these three tools within the design method that will follow in chapter 8 in order to attempt the creation of engaging wearable technology that do not only act as signs in order to maintain the possible engaging qualities visible within our distal devices that perhaps increases the durability of our relationships with them.

5. Design Method

In order to measure the particular value of distal devices, as proposed in chapter 5, this chapter will introduce a design method expanding upon the work of Giulio Jacucci, a principal investigator into ubiquitous interaction, and particularly his thesis

Interaction as Performance (2004).

5.1. Jacucci’s Interaction as Performance

Performance proposes the individual, the local and the emergent as opposed to the universal, the general and the static. These features pointed to configuring as staging and transforming that implies a more active role of people (as individual and as collectives) in crafting the role and meaning of technology in their lifes (sic). (p.9).

Jacucci uses his thesis to look at examples of what he describes as “physical interfaces” (p.9) from a performance studies perspective. “Physical interface” is the term Jacucci uses to describe the “meaningful interactions that happen in the physical environment” (p.20). An example he uses to define this is a file being dragged on a computer desktop. The physical interface would be the user’s hand moving the mouse across the mouse pad (p.20).

Jacucci recommends the use of “mixed media” (p. 45) within his research to create these “physical interfaces”.

The cases considered in this thesis show how human interconnectedness takes place through material consisting of artful assemblages of digital objects and physical artifacts (p.15).

Jacucci focuses on the following four aspects of physical interfaces within his research.

− Space, issues around the spatial dimension of physical interfaces, − Physical artifacts, links between digital objects and physical artifacts

that “populate” environments,

− Configurability, issues that address the support for re-configuration and rearrangements of augmented environments,

− Bodily movements, embodied actions and gestures, their expressivity and relation to physical interfaces” (p.21)

Jacucci situates his work within human-computer interaction and respects Dourish’s work on Embodied Interactions (Dourish, 2001 cited in Jacucci, 2004 p.75) and states that technology acts “as augmentations and amplifications of our own activities” (p.31). Jacucci does however agree with Ciborra (2002 cited in Jacucci, 2004 p. 32) who says that what is missing from situated action literature based around phenomenological concepts, such as Dourish’s work, is what Ciborra calls “the moods of the actor” (p.32). Ciborra states “the way we care about the world unfolds according to the passing mood that attunes us with the situation” (p.32). This emphasis on the research taking into account our shifting emotions in relation tour relationship with objects is something this thesis will focus on and something that Jacucci’s notion of interaction as performance allows.

A performance perspective aims at creating experiences where participants are more aware, think feelingly about the artifacts around them and engage in the situation in reflection or perception in action. (p.18)

Jacucci lists a number of definitions of “performance” in order to situate his perspective. The definition which best suited this thesis is a notion of performance seen from an anthropological perspective. Within this thesis “performance” denotes a situation where human acts are to be carried out “with a real or notional spectator in mind, and so with an awareness that they are expressive.” (Counsell & Wolf 2001, p. 157 quoted by Jacucci, 2004, p. 53)

The term “expressive” (p.69) is used by Jacucci to signify that movements when interacting with physical interfaces hold meaning, either representational meaning created by the participant, or meaning read by a spectator. Jacucci also states that “expressions” (p.69) can be a way for us to reveal our individual experiences to others.

Participants create expressions with a spectator in mind. These may generate new insights privileging perception over recognition, and requiring energy for active participation and consciousness of the acts. Expressions are embodied in space, artifacts (including mixed objects) and bodily movements and are perceived privileging sense experience over verbal forms and analytical thinking. (p.68)

This thesis will not only define performance as acts carried out with the notion of a spectator, but also as Susan Kozel proposes in her book, Closer (2008). Closer explores performance and movement as a phenomenological practice. Susan Kozel expands upon a performance theory definition that “performance” could be the label given to all actions. Closer poses a more phenomenological perspective to performance.

Performance entails a reflective intentionality on the part of the performer herself, a decision to see/feel/hear herself as performing while she is performing (p.69)

This thesis will therefore combine Jacucci’s anthropological definition of performance as an act carried out with a real or notional spectator in mind with the phenomenological practice involved in intentional actions that produce performance. Both definitions of performance are used within this thesis with the aim of producing “perception over recognition” (Jacucci, 2004 p.68). In order to produce results that answer the research question; what will we lose if our distal devices became wearable? It is important that the research in this thesis does not only produce scenarios that prompt recognition of our interactions with our distal devices. The research within this thesis will aim to produce perceptions. Perception requires reflection from the participants involved in the research and a re-making of our notions of interactions between us and our distal devices. The reflection that creates perception will be the aim of performative scenarios implemented in the research within this thesis.

5.2. Performative Scenarios

Both Verbeek’s post-phenomenological perspective and an expanded version of Jacucci’s methods in Interaction as Performance (2004) will be implemented within the research in chapters 6, 7 and 8 in order to create performative scenarios. These scenarios will either be created through the framing of a discovered situation or be designed. As previously discussed, these scenarios aim to privilege perception over recognition in order to generate new insights into our interactions with our devices, both distal and wearable. Following Jacucci and Kozel’s definitions of performance, performative scenarios use both notions of a spectator, and the encouragement of

intentional actions in order to prompt perception within the interaction in the following three ways.

1. Through the exaggeration of the un-usefulness and theatricality of the actions proposed with the scenarios, this creates an increased awareness of intentional actions required from the participant by asking them to act along with the scenario.

2. Through the presence of a living, human spectator in the form of an interviewer.

3. Through the action of documenting the scenario through the presence of a camera in order to create a notional spectator.

Each performative scenario will first be introduced through a design opening. A design opening introduces the event or need that produces the performative scenario. Either the framing of a discovered scenario or a designed scenario will follow and be analyzed through a modification of Jacucci’s four aspects of physical interfaces: - Space

- Physical artifacts - Configurability - Bodily movements

The implementation of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces will highlight elements within the performative scenarios that are most relevant to the interaction design methods used, and the themes followed, in this thesis. This will be in order to attempt to make the partially subjective documentation of the performative scenarios more objective. This thesis will modify and expand on these four aspects of physical interfaces in order to analyze each performative scenario. Reasons for the modifications or expansions will be given as the performative scenarios are presented.

5.3 Relevant work:

Participant’s intentional

Action

Spectator Expression Perception

+ = +

Performative Scenario

Figure 2. An image from The Astronaut Aerobics Institute (Used with permission from Lucymcrae.net, 2015)

Lucy McRae is a body architect, this title reflects her background in dance and architecture. Lucy McRae is currently working on “prepping the body to go to space” (Lucymcrae.net, 2015). Her current project, The Astronaut Aerobics Institute, looks into the absence of gravity effects on the body in vacuumed environments. She uses currently available technology to explore future scenarios where the body would need “to withstand long periods of time and space”. The findings from these experiments relate to the way that when exposed to a vacuum, the body sends oxygen to the skin, which heightens senses and rejuvenates the cells. The findings from explorations within this project were framed as a spa experience that audience members could experience for themselves at a four-day installation at the London Design Festival in 2014.

These explorations of possible future scenarios through tests using current technology fit well into the methods that will be used in this thesis in order to attempt to design wearable technology that reduces the loss we will experience if our distal devices became wearable. Lucy McRae’s work often focuses on the physical and sensorial results of tests challenging the body in different environments. Without attempting to create these future scenarios in the present, the concept that a possible future scenario where our bodies live in vacuums could be therapeutic and a pleasant experience would not have been discovered. The Astronaut Aerobics Institute projects are documented for those not able to experience the spa directly through the use of synchronized swimmers to illustrate the movement possibilities within the weightless vacuum. The human movements possible by the expert swimmers give a feeling of ultra-human future possibilities to the viewer. The Astronaut Aerobics Institute could be framed as a performative scenario, where through design and re-enactments, the realities of a future scenario are made more tangible to us now. The Astronaut Aerobics Institute presents our bodily reactions to future states that can be used within design processes to improve the experience for the future body.

6. Discovered Performative Scenarios

As a means to explore what we will lose when distal devices become wearable devices, this thesis will first look at past and present examples of relationships that exist between us and our devices. The term discovered is used to signal that the thinking behind the selection of the performative scenarios used in this thesis is also part of the implementation of the design method2.

The narrative writing style and methods used in Turkle’s work Evocative Objects (2007) will inform the manner in which each performative scenario is presented within this thesis. This means that I will use my own voice, as I am the observer (and spectator) of these scenarios. My methods differ from Turkle’s in chapter 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3 as the participants do not write the accounts themselves. This is because I wanted my observations and particular perspectives on the relationships I witness to be included within the examples. A further modification of Turkle’s methods is that I gave the documentation of my examples back to the participants in order to check that my work represents their situation accurately and in order to gain reflective insights. The examples that follow are the results of interviews conducted with people in my life who have an interesting relationship either with their current distal devices, or who are on a journey, or have completed a journey, from having a distal device to having a wearable device. Skype interviews and face-to-face discussions were my ethnographical methods of collecting information. All accounts and names are used consensually and are taken from personal communications; Julia 2015, Chez, 2015 and Sam, 2015.

6.1. Julia

Design Opening

Julia is given a new phone by her father. Performative Scenario

Julia and her boyfriend recently broke up and her boyfriend moved away from their apartment in Sweden and back to his home country of New Zealand. Although they had been living together recently, there had been long periods in their relationship when they had been long distance and so were both used to their phones being an enabler for their relationship continuing. After her boyfriend left Julia was given a new iPhone by her father. “My dad buys me technology to show me

he loves me”. This iPhone not only represented the support her father was showing her in this difficult time, but also that she was starting a new chapter in her life. I asked Julia whether she was transferring everything from her old phone to her new phone and she said yes, except the photographs. She said she would only import three photographs, one of a design for a tattoo that she is planning on getting, one of her

2 The author’s background in dance practice and performance art, influence the perspectives shown within this thesis.

Figure 3. Julia’s phone case displayed on her wall next to other artworks

bedroom after she had re-arranged the furniture in order to make her feel more ownership of it now that her boyfriend was not living there anymore, and a photograph of old friends who had supported her through the break-up. These photographs represent her new focus on her future self, new habitat and the friends that became closer to her because of the break-up.

I asked Julia if she felt any emotions towards her old phone. The protective casing on her old phone was something that she would miss and could not transfer to her new phone, as it would not fit the newer model. It was clear, however, that once the protective case and the content were obsolete or transferred, the device really held no meaning for her. She did however say that she might display the case in her room (Figure 1.), which she later went on to do. The case reminded her of the trip to New York where she had bought it. This perhaps shows that the customized features of her phone hold emotional value within them and made her remember and recognize the journeys it has gone on with her, both physically and emotionally.

When I discussed the text above with Julia she said that it reminded her about a friend whose father died of cancer last summer. Before his death, the last thing the father did was to buy his daughter a new phone, as hers was old and almost broken. Julia said her friend now holds great value in her new phone and that it brings comfort to her to have this connection with her father. Julia feels concerned about the time when this new phone begins to degrade, though she speculated that the degradation would maybe signal another mourning process and that perhaps when her friend does eventually have to let go of this phone it would even help her friend to stop grieving and move on. I interpret these thoughts as Julia drawing likenesses between her own situation with her friend’s situation. For Julia a new phone signals an ending to a mourning process and a transition into a new stage in life.

Analysis through Jacucci’s four aspects of physical interfaces:

Space: Julia’s new phone does no longer have to maintain a spatial connection to New

Zealand. Her old case reminded her of travelling, both physically and emotionally.

Physical Artifacts: No emotional value lay in the old hardware of the phone, only the

content and customized aspects. However, new hardware did signal a fresh start.

Configurability: Had the new phone not been offered to Julia she would not have

reflected on the possibility that a having a new phone would affect her emotionally.

Bodily Movements: The physical act of selectively transferring data from one device to

the other, and removing the case from the old device allowed Julia to consider how she would form her future, and what she would keep for nostalgia’s sake.

6.1.1 First modifications of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces

The methods of employing Jacucci’s four aspects of physical interface in order to draw conclusions from performative scenarios will now be modified. The first modification is made in order to emphasize the notion of a spectator and intentional actions that define the performance aspect within the performative scenario. Once Jacucci’s four aspects were implemented in the first scenario it became clear that they were better suited to ethnographic documentation of design methods such as body storming, where design is done on site and in the context of the concept being designed (Oulasvirta, Kurvinen & Kankainen, 2003). The evolution of body storming to

embodied storming (Schleicher, Jones & Kachur, 2010) rejected body-storming’s use of personas in favour of real users within their real habitats and the exchange of tacit knowledge that this method allows. This thesis will expand these interaction design methods further to include an attempt to further analyse the feelings of the participant within the examples. The addition of Spectator/Intentional Actions will highlight the performance and expressions visible within the performative scenarios and the nuances within the relationships that these aspects reveal. The aspect

Spectator/Intentional Actions can be read as the key reason that this discovered

performative scenario is included in this thesis as this is where perceptions of our relationships with devices can be made visible.

The aspects Configurability and Bodily movements will also be combined to reflect the fact that the bodily movements reveal the configurability of the scenario. The ability of performance scenarios to reveal relationships between people and their devices lies in the individual ways that the participants interact with the physical artifacts. The configurability is therefore not designed and so becomes an obsolete aspect within performative scenarios as implemented in this thesis. These aspects will therefore be combined and titled only Bodily Movements. The aspect space will also be renamed

proximity of device to body in order to more clearly signpost where on the journey from

distal to wearable the device in the example lies.

6.2. Chez

Design Opening

Chez doesn’t wear her Smart Watch. Performative Scenario

Chez works within programming and interaction design and recently bought a Smart Watch that is synchronized with her mobile phone and provided a wearable interface on her wrist. Chez was interested in how a Smart Watch would function within her life, and whether it would make her look at her phone less frequently.

Chez’s work means that she is often involved in discussions about the ethics of the capturing and misuse of data and the dark side of the Internet of Things. Chez is also involved in a DIY culture and plans workshops where people can make their own wearables. When I spoke to Chez she admitted that “I am a hypocrite”, Chez feels this because she is critical of the way that companies use data captured from their users through wearable technology and social media, but also understands the root of the companies' interest in this data. Chez says that she feels “curious” about the data that can be collected from wearable technology that she creates, “it gives me a chance to be nosy”. Chez believes that the drive behind the commercial businesses that profit from the collection and use of data is also curiosity, companies wish to better understand their users, and perhaps humans in general. However, Chez’s description of herself as a “hypocrite” comes from the fact that she is unwilling to provide the data that allows this understanding that data collection brings. This is founded upon her concerns that although she loves the idea of open, fluid data sharing, she still feels that there are security risks. These concerns about security became very tangible when Chez wore the watch; “I felt like I was being watched”. Chez also told me that her feelings of paranoia increased at certain points in her menstrual cycle and this made wearing the Smart Watch almost unbearable at those times.

Chez took some consideration when choosing which Smart Watch to buy and deliberately chose one with a technological design that she could understand fully. The Smart Watch she chose was also the most customizable and easiest to develop for. The benefits of the Smart Watch to be open and adaptable for other uses were however undermined by the fact that it was not possible to customize which social media and email notifications were delivered. The fact that the notifications were delivered through vibrations onto her skin meant that the notifications were very distracting and unavoidable, and because Chez could not chose what she was and wasn’t alerted about, the notifications were often irritatingly irrelevant. Chez now mainly only uses it when driving to change the music playing in her car which is the only scenario in which the Smart Watch’s benefits outweighs both the feelings of paranoia and the irritating delivery of irrelevant information.

Analysis through a modification of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces:

Proximity of device to body: The device is designed to be worn on the wrist.

Physical Artifacts: Although Chez is involved in creating wearable technology, the fact

that another company had created the device and still owned some part of the data she produced made her feel uncomfortable. Chez deliberately chose this model because it was most technologically accessible and understandable to her.

Bodily Movements: Chez still uses the device for the components that benefit her because

of increased safety when driving, but otherwise keeps it in her bedroom.

Spectator/Intentional Actions: The tracking of her movements and geographical position

was worrying to Chez as she felt that she was being watched. Chez felt better when she removed the Smart Watch from her body, although this made the device obsolete. Chez is her own spectator in respects to her description of herself as “a hypocrite”. She is aware of her own intentional actions of removing the watch due to her emotional reaction to it, and the fact that these intentional actions are contradictory in respect to her work and interests.

6.3. Sam

Design Opening

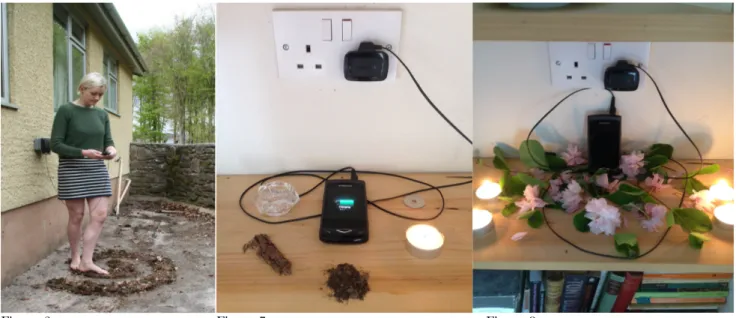

Sam now uses a wearable insulin pump. Performative Scenario

Sam used an insulin-injecting pen for ten years before getting a wearable insulin pump seven months ago (figure 2). The wearable pump includes an intravenous tube that needs to change site every 3-4 days. The tube is inserted into the stomach and the tube is held in place by a round plaster. A pager-sized device is attached to this tube that releases the insulin and provided an interface. Sam’s decision to switch to a wearable pump seven months

ago was driven by concerns that the National Health Service in England would soon fold because of the current political climate. He felt that this could well be his last chance to have it fitted for free. For Sam the socio-political context of his pump also

means that he disregards the recommended amount of time he should change his pump by one day “else I would be wasting the NHS’s money by throwing away two days of insulin a month”. He reasons this by saying that it won’t have negative effects on his body and that the professionals at the hospital are not the ones wearing the devices, so he feels he can make an informed decision.

It became very clear when talking to Sam that the question of how much he identifies as “a diabetic” is an important factor for him. For Sam one of the main benefits of having the pump is the reduction in the amount of actions related to diabetes he has to complete. Regulating his insulin used to mean injecting his leg, stomach or buttock many times a day, which was not only painful, but also public. He says, “As a wearable thing it makes it less of a visible condition even though it’s more visible as an object”. Sam says that he actually checks his blood sugar much more often now because of the pump. He says he is more aware of his diabetes generally since is it physically attached to him. “You have to play along with it.” For Sam the wearable device did make him “feel more like a diabetic”, but the pay-off for this was not having the physical pain from the multiple daily injections, and the keeping of the discipline needed to complete all the manual insulin monitoring, was enough to make the increase in identifying as “a diabetic” worth it. The fact that there is a decrease in the number of actions he has to complete that make him less “visible” as a diabetic to other people seem to outweigh the fact that his personal identity as a diabetic is stronger now. Sam’s method of checking his blood sugar is through another device, which is not attached to him. I asked why it wasn’t and he said that he could choose to have one but he didn’t like the idea of having another device attached to him, and the act of checking the blood sugar manual was not enough bother to be worth having another wearable device. Sam also said that there was a certain type of diabetic who get all the accessories. “People who really, really care get all the extra bits. Those are people who let it run their life.” He referred to those people who would have “Type one diabetic” as part of their profile on Twitter. Sam obviously does not identify with this group.

Sam was in fact one of my first boyfriends ten years ago. I was discussing with a friend a while ago how we felt quite nostalgic for the time when wherever Sam went a trail of medical waste followed him. I would find the needle attachments to his insulin pen everywhere, years after he stopped coming to my house. I asked Sam whether he felt any of this himself and he answered, “I’m not sure how much room there is for nostalgia around injections… I do produce a lot less medical waste now.” I asked Sam about how the device fitted into his life functionally. He told me he kept it in his pocket mostly or clipped onto his clothes, he described it as “handy” and “versatile”. The only “gross bit is that there’s a bit of tube that has been inside of you”. This didn’t seem to bother Sam now, for him the inside of his skin was the same as his outer skin “it’s just like a plaster really”. When he slept the device lays next to him. Sam was recently accidentally sent a longer tube that attached the device to his stomach; he said that the extra five inches that this tube gave him made a large difference to how much freedom he had when sleeping. Sam lives with his girlfriend, Helen. Sam told me that Helen finds the device a lot more irritating that Sam does and that “she doesn’t trust it”. Sam felt that their feeling differed “Because it’s attached to me I don’t worry about it because I’m not worrying about someone else’s health and wellbeing if it’s not working.”

I asked Sam if he felt like a cyborg. “Yes and no. In a way because there’s a thing attached to me doing the role of an organ, which is quite weird. I don’t think of it as weird because I live with it every day.” This showed that for Sam, the term cyborg meant “weird” and that that view came from others who were not as accustomed to it as he was. He reflected that it was “unnatural rather than weird. It’s not a natural thing but given the fact my body doesn’t produce something and the solution is an unnatural solution, the solution a hundred years ago would have been for me to die… being considered a cyborg is a better solution than for me to die.”

Analysis through a modification of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces:

Proximity of device to body: Sam’s insulin pen has migrated into his body and is now

subcutaneous.

Physical Artifacts: The fact that the device is subcutaneous is not an issue for Sam now

he has adapted to it, though he understands that it is a “weird” concept for others around him. The fact that the device uses batteries that can be bought in normal shops makes the device much more useful to him as the act of charging the device does not require special equipment that he would have to carry with him. Sam enjoys the aesthetics of the wearable insulin pump and the functionality of the interface.

Bodily Movements: Sam no longer has to make three daily injects with are painful and

also identify him as a diabetic to others.

Spectator/Intentional Actions: Sam made the decision to bring his insulin pen into his

body. This decision was based on political concerns about the future of free healthcare in Britain. The reduction in the outwardly visible bodily movements, such as the three-times-daily injections that the distal insulin pen required, benefits Sam as he feels like he is less identifiable as a diabetic to others, though his own personal identity as a diabetic is stronger. Sam does not have a wearable glucose monitor as he feels it would put him in the same category of those who deliberately include being diabetic in the way they present themselves to others.

6.4 Implications of Discovered Performative Scenarios

This section will further unfold some particular concepts flagged in the discovered performative scenarios above. The concepts drawn from this unfolding will provide the inspiration for the designed performative scenarios shown in chapter 8 in order to design new performative scenarios illustrating relationships between people and distal devices.

Some aspects of Sam’s account of his transition from a distal insulin pen to a wearable insulin-delivering device relate to a first-person account given in Evocative Objects;

Things We Think With by Sherry Turkle in the chapter “The Elite Glucometer” (p.63).

The account is by Cevetello and features his account of his relationship with his evocative glucose-measuring device. The book was published in 2007, and Cevetello’s account shows that he has no knowledge of existing wearable diabetes devices. There are some interesting parallels and differences between Sam’s account and Cevetello’s relationships with their devices. Both men have a relationship with their blood sugar levels that affects them emotionally. For Cevetello when the levels are not optimum his “mood changes abruptly” (p.65). Sam does not describe the negative feelings he feels but instead describes the positive “achievement” he experiences when the levels

are good. Both Sam and Cevetello are unsettled when the levels shown conflict with how they feel physically. Cevetello needs to remember what he ate differently that changed his sugar levels in order to regain “control” of his situation. Sam’s pump helps him improve his emotional state if his blood sugar is unexpectedly high or low by taking him through the steps of the “Bolus Wizard” that can rectify his insulin levels accurately. Sam relies on his device to fix the situation, rather than blame himself, as Cevetello does, for getting into the situation in the first place. Sam relies on his pump to control his uncontrolled, and uncontrollable, body and eating habits. At the end of his account Joseph Cevetello predicts two possible future scenarios. In the first his glucometer is wearable and gives him constant readings that he has to communicate to his insulin delivery device within a ubiquitous computing filled world. In this scenario “I am in control of these devices, they do what I tell them to.” Cevetello feels that his would still mean that he is “a diseased person caring for myself” (p.66). Sam’s current situation is the opposite of Cevetello’s first scenario; the insulin delivering device is wearable, not the monitor. Sam still chooses to monitor his own blood sugar levels. Sam’s wearable pump ultimately controls his insulin dosage and therefore cares for him, rather than allowing him to care for himself. Cevetello’s second future scenario is one where no intervention is needed by the user and the glucometer and insulin delivery device are both installed inside the body and communicate machine-to-machine. “I do not control my disease, my computer pancreas controls it for me” (p.67). To describe how this situation would define him he quotes Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline’s definition of cyborg;

Synergy between a machine and a human being that does not require any conscious thought on the part of the human (Clynes & Kline, 1960 quoted in Turkle, 2007 p.67).

Sam is aware that some would already consider him a cyborg, though there is still the element of “conscious thought” within his technological situation. For him the pay-off of the decrease of discipline needed and reduction in actions that identify him as a diabetic to others makes his cyborg status worth the label. There is some possibility that Sam’s desire to reduce actions that identified him as a diabetic to others is an example of Sam’s use of his body as a sign, a signal to other about who we are and who we want to be. This is something that Verbeek was attempting to avoid with his post-phenomenological theories within industrial design. The fact that one of the main benefits of the pump for Sam is that the amount of diabetic action is reduced could signal that if there were an option for these actions to be eradicated completely by a machine-to-machine circuitry, Sam would choose it and, in the eyes of Clynes and Kline, become a cyborg. Sam’s wearable devices allowed the reduction of the

actions and discipline required to regulate his insulin levels. This reduction in actions

was beneficial enough to him to outweigh other concerns about the trustworthiness of the automation of his device (which was felt by his girlfriend) and his increased inner identity as a diabetic.

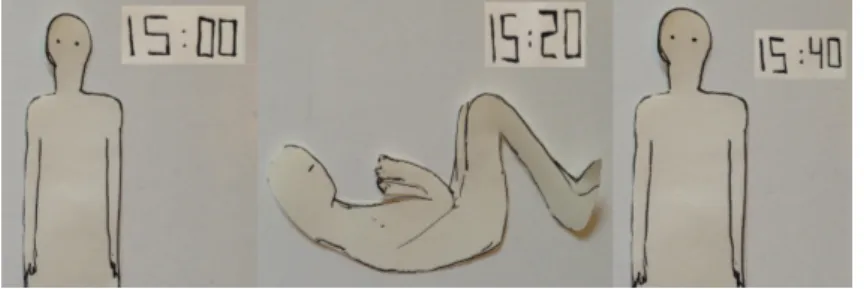

6.5 Second modification of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces

The fact that it can be seen that wearable devices allow us the reduction of “conscious thought on the part of the human” signals that within our interactions with distal devices there is conscious thought. This thesis will explore our “conscious thoughts” (p.67) present when we interact with our distal devices through focusing on the actions

that bring conscious thought that take place within our interactions with our distal devices.

These actions that bring conscious thought make us conscious of our devices. Actions that bring

conscious thought are where we accept the presence of our distal devices, and our relationship with them. Sam’s actions that brought conscious thought were his

three-times-daily insulin injections with his distal insulin pen. Actions that bring conscious thought will now be assumed as the element that would be lost in answer to the research question

what would we lose if our distal devices become wearable devices? A modification of Jacucci’s

aspects of physical interfaces will be made and the category Actions that bring conscious

thought will now replace the term Design Opening within the framing of the following

performative scenarios, as all designed performative scenarios from this point on will be designed with the aim of exploring the particular Actions that bring conscious thought that is being maintained within each scenario, whether using distal devices in chapter 7, or wearable devices in chapter 8.

7. Designed Performative Scenarios - Distal Devices.

7.1. The Spa

Actions that bring conscious thought: The distal device requires protection and maintenance so it does not become scratched and dirty, which would affect the aesthetics and functionality of the device.

Performative Scenario

A few weeks ago, I watched two friends change their mobile phone covers and protective screens. There was a very concentrated atmosphere in the room and a care and thoughtfulness in their movements as they lifted the naked device out of it’s old home, cleaned and swaddled it in plastic film, and fitted the new case. They both marveled at their device’s transformation and reincarnation.

I wanted to focus on this process and so created a performative scenario in the form of a short film. The paraphernalia and set up required to prepare the phone for it’s new life reminded me of a beauty treatment in a spa, where care and welfare is an important factor within the interactions. I wanted to create something that would make us reflect on the lengths we go to to protect and preserve the look of our devices. Perhaps this could tell us something about how we feel they represent us, and our aesthetics.

For the film I used beauty tools and precise, caring movements to clean my phone, and then carefully apply a new protective cover. I overlaid relaxing spa music on top to heighten the theme, and made sure my hands, the only part of my body featured in the film, were manicured.

When I showed this film to others, some did reflect that they also took this level of care when looking after their phone, but that they only did this so that they didn’t have to worry about scratching or damaging the phone most of the time. It was an action that they did once or twice a year in order to give them freedom to be more careless with their phones the rest of the time.

Analysis through a modification of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces:

Proximity of device to body: The device is kept within arms reach. The frame of the film is

close and reflects the intimate space (Hall, 1966) we keep our devices within. Figure 5. Still image from 7.1 The Spa

Physical Artifacts: The use of beauty tools highlighted the self-maintenance in the act of

caring for our distal devices. The addition of the spa music enhanced the actions as self-maintenance.

Bodily Movements: The performative scenario exaggerated the caring movements that

we adopt when maintaining our devices. The use of beauty tools and music provoked particular actions to be used that referred to spa treatments.

Spectator/Intentional Actions: The exaggeration of the caring movements through the

staging of the spa environment increased awareness of how we look after our distal devices. This refers to the possibility that we see our distal devices as extensions of ourselves. We care about the judgments of others based on the ways we treat our distal devices; our devices mirror us. The actions we make to maintain our device could be seen as self-maintenance as our devices are extensions of ourselves.

7.2. The Secretary

Actions that bring conscious thought: The user of the distal device needs to be alerted to notifications by their distal device.

Performative Scenario

For this performative scenario I wanted to attempt to embody a distal device. I asked my friend Ida to entrust me with her phone. I then took possession of it for the time we spent together, and delivered each notification and message that arrived to her verbally. I took no regard to the context in which I delivered the messages. I interrupted her conversations and even shouted through a toilet door in order to deliver the information as it arrived. She became irritated by this, but did reflect that this was how it was normally with her device, except that the way that the messages are delivered by her phone were less intrusive. It was easier to disregard information that was not useful in the context she was in if it was signaled by an electronic noise and delivered through text. The fact that I stood in front of her and verbally delivered the message made the irrelevance of its contents irritating.

As the embodiment of a distal device, I found the experience much more personal and intrusive than I had anticipated. To have Ida dictate private messages to me to write and send to others felt like a very personal act and I realized that I had taken a position of power in that I could influence Ida’s relationships with others if I miswrote the message. It felt ethically wrong that the recipient would not know that there was a middle person (me) between their personal communications. Ida had consented to me handling her private information, but this other party had not. I did have a feeling that this experience reflected the increasing awareness in current society that our communications are not private, and there are many middle-men observing our private conversations.

For Ida, having me embody her phone increased her awareness of the irrelevance and lack of context of the communications that she received through her phone on a day-to-day basis. She has learnt, or the interface allows her, to sift through these communications and sort the important and relevant from the irrelevant in order for her to function smoothly. It could be argued that Ida could learn to get used to my role as a secretary. The next development to this experiment could be that I use my own initiative to sift the communications for those that were relevant and contextual, but I didn’t feel ready to take those decisions on behalf of Ida. A traditional secretary

takes this role, but it is a skill that is learnt and regulated by an employer and takes time to develop. The desire for technology to become contextually aware is one goal within the I.O.T. but from my experience it would be a big step to take and require a huge amount of trust from the user as well as some degree of artificial intelligence within the device.

Analysis through a modification of Jacucci’s aspects of physical interfaces:

Proximity of device to body: As Ida’s distal device I stayed close to Ida, though within her

personal space rather than her intimate space (Hall, 1966), and followed her around. The fact that my body had it’s own movement agency meant that Ida did not need to carry me on her body.

Physical Artifacts: I was the device and in order for Ida to write messages and check her

device her interactions had to come through me. These interactions were affected by our personal relationship.

Bodily movements: My voice was the tool used to deliver notifications and so my body

had to be present at all times, with the exception of when Ida was in the toilet. Ida addressed her device through me and so used normal human-to-human interaction methods.

Spectator/Intentional Actions: It was irritating for Ida to have irrelevant notifications

delivered to her in such an obtrusive way through human-to-human interactions, perhaps because there were some social conventions that did not allow Ida to disregard my interactions, and therefore the information that I was delivering. I felt uneasy about having access to personal information and communications.

7.3. The Charging of our Distal Devices

This section of the chapter will explore more specifically the actions that bring conscious

thought involved when we place our devices to charge. This focus on the act of

charging of our devices will provide the basis for the designed performative scenarios shown in chapter 8.

Chris Dancy, an “extreme life hacker” and “the most connected human on earth” (Chrisdancy.com, 2015), recently returned from a six-day meditation retreat. Upon his return he wrote a blog post with a long, poetic, manifesto calling for us to return our attentions back to our bodies and minds by using meditation (“Path of the Mindful Cyborg, 2015).

Have you ever stopped to think about how much we care for our “smart devices” made of glass and metal and how little we care for the ones made of flesh and bone?

Our devices ring, clamor, and shout for your love and attention.

We quickly pull to refresh after satiating their voracious appetite for our moment-to-moment distractions.

Yet our minds are lacking clarity to recognize our own needs to slow down. Our devices flash fullscreen alerts when they are running low on energy, and we race to an outlet and nestle them gently back to sleep.

Yet our bodies have become exhausted, torn, scratched and malnourished. Our devices come with extended warranties, loss protection.

We buy cases, covers, and cords to protect our precious devices. Yet our hearts have become bent, misshapen and unconnected.