Factors for Organisational Learning

enabling Sustainability Transitions

A case study exploring a Public Service Agency in Scandinavia

Elizabeth Bull

Maren Fokuhl

Main field of study - Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2020

Title: Factors for Organisational Learning enabling Sustainability Transitions: A case study exploring a Public Service Agency in Scandinavia

Authors: Elizabeth Bull, Maren Fokuhl

Main field of study: Leadership and Organisation University: Malmö University

Subject: Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E)

Period: Spring 2020 Supervisor: Hope Witmer

Abstract

The growing interest in sustainability amounts pressure on organisations to operate in more environmentally friendly ways, sparking the need for radical sustainable change. The purpose of this study is to discover what factors and conditions facilitate and hinder organisational learning for sustainability transitions (ST), a topic that has caught recent academic attention and thus needs further interdisciplinary research. The conceptual framework derives inspiration from the Four Factors of Learning for ST whilst the Competing Values Framework and the Three Loops of Learning are used as additional lens to better understand the conditions of learning for ST. The thesis will take a qualitative approach through conducting a content analysis of three company documents and seven semi-structured interviews with employees from a public service agency in Scandinavia currently implementing a transition lab. A descriptive analysis of the coded data highlights the levels of understanding and acceptance towards sustainability transitions from the case organisation and the conditions that facilitate and hinder organisational learning. The results show that the most prominent of the Four Factors of Learning for ST in the early phase of a sustainability transition is interpersonal, followed by material, institutional and intrapersonal. Within these factors, the discussion further highlights the most prevalent sub-codes and themes that reoccur in the data. Moreover, five key findings under the themes of flexibility versus control, resource availability through digitalisation, communication, collaboration and facing complexity using institutional logics were identified as the primary facilitating and hindering factors that promote learning for STs. Finally, recommendations are presented to inform both theory, and practice, as further analysing learning for ST is of high relevance to better understand and design these learning journeys and a more sustainable (organisational) future.

Key words: Sustainability Transition, Organisational Learning, Public Service Agencies, Competing

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.1.1 Sustainable Development ... 1 1.1.2 Sustainability Transitions ... 1 1.2 Context of Study ... 21.2.1 Scandinavian Public Service Agencies ... 2

1.2.2 Wastewater Industry ... 3

1.3 Previous Research ... 3

1.3.1 Organisational Culture ... 3

1.3.2 Organisational Learning ... 4

1.3.3 Learning for Sustainability Transitions ... 5

1.4 Problem Statement ... 5

1.5 Research Aim and Contribution ... 6

1.6 Purpose and Research Questions ... 6

1.7 Structure of the Thesis ... 6

2. Theoretical Background ... 8

2.1 Organisational Learning in Sustainability Transitions ... 8

2.2 Three Loops of Learning ... 8

2.3 Competing Values Framework ... 9

2.4 Four Factors of Learning for ST ... 10

3. Methodology ... 11

3.1 Research Approach and Design ... 11

3.2 Data Collection ... 11

3.3 Data Analysis ... 12

3.4 Adapted Conceptual Frame ... 12

3.5 Reliability and Validity ... 14

3.6 Limitations ... 15

4. Descriptive Analysis ... 16

4.1 Four Factors of Learning for ST ... 16

4.1.1 Intrapersonal Factors ... 16

4.1.2 Interpersonal Factors ... 17

4.1.3 Institutional Factors ... 19

4.1.4 Material Factors ... 20

4.2 Organisational Learning ... 22

4.2.1 Competing Values Framework ... 22

4.2.2 Need for Change and Complexity ... 22

4.2.3 Conditions for Learning ... 23

4.2.4.2 Double Loop Learning ... 25

4.2.4.3 Triple Loop Learning ... 26

4.3 Summary of Descriptive Analysis ... 27

5. Discussion ... 28

5.1 Frequency of Factors ... 28

5.2. Factors that Facilitate and Hinder Learning for ST ... 29

5.2.1 Finding a Balance Between Flexibility and Control ... 31

5.2.2 Freeing Resources Through Digitalisation and Innovation ... 32

5.2.3 Communication as a Tool for Supporting Learning ... 33

5.2.4 Co-Creating the Future Through Collaboration ... 34

5.2.5 Facing Complexity and Uncertainty Through Critically Assessing Institutional Logics ... 35

6. Conclusion ... 37

6.1 Future Recommendations ... 37

6.1.1 Implications and Future Recommendations for Academia ... 37

6.1.2 Implications and Future Recommendations for Practitioners ... 38

6.2 Summary ... 39

References ... 41

Appendix A: Codebook ... 49

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Learning for Sustainability Transition (developed by the authors of this thesis, inspired by

Van Poeck et al., (2020), Argyris and Schön (1974) and Cameron and Quinn, 2011) ... 13

Figure 2: Frequency of the Four Factors of Learning for ST found in the coded segments (adopted

from Van Poeck et al. (2020)) ... 28

Table of Tables

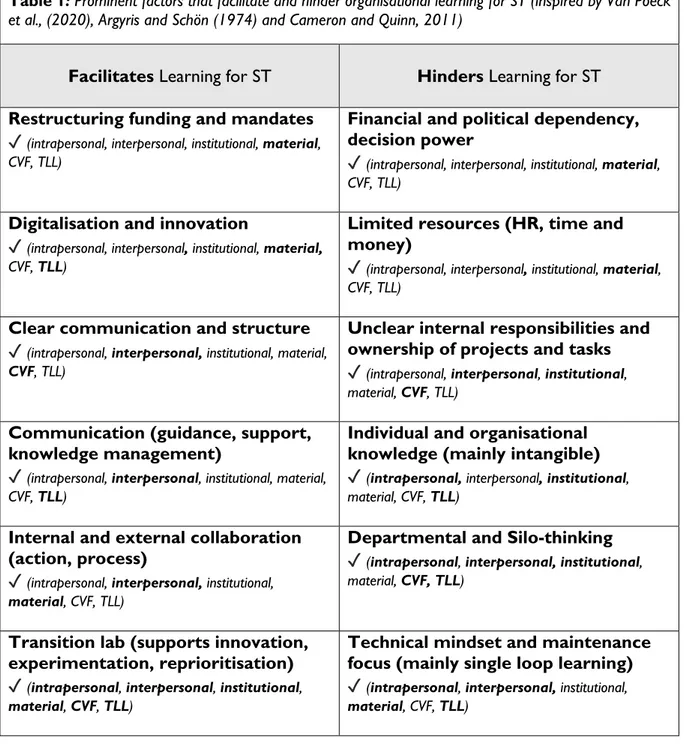

Table 1: Prominent factors that facilitate and hinder organisational learning for ST (inspired by Van

Poeck et al., (2020), Argyris and Schön (1974) and Cameron and Quinn, 2011) ... 30

List of Abbreviations

CVF: Competing Values Framework ST: Sustainability Transition

1. Introduction

This chapter provides a brief introduction to the key concepts that guide this study, positioning it within the wider scope of research. It then discusses the problem statement, highlighting the importance of the research and concludes with the purpose, aim and research questions of the thesis.

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Sustainable Development

Organisations have been recognised as one of the main contributors towards global warming (Robertson & Barling, 2012), yet current practices highlight the ongoing unsustainable use of natural, finite resources resulting in environmental damage (Huemann & Silvius, 2017). The renowned Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted in 2015 and call into action all UN member states to achieve numerous climate change targets by 2030. Of particular focus to this paper is SDG number six, sustainable management of water and sanitation for all (UN General Assembly, 2015) as this is the contextual background in which the case organisation operates that will be discussed further in section 1.2.2.

1.1.2 Sustainability Transitions

Sustainability Transitions (ST) is an emerging transcapillary field of research, established within the last 20 years, that studies co-evolutionary processes in complex societal settings that unfold over long periods of time (Geels, 2012; Köhler et al., 2019). In general, STs can be described as long-term, radical and profound transformations which are deeply anchored in cultures, practices and structures (Paredis, 2013; Van Poeck et al., 2020).Thus, they are non-linear, long-term learning processes that involve a change in deeply embedded structures, cultures and operational practices. Due to the profound and multi-layered form of transformation, aspects such as technology, policies, economy, institutions, cultural meaning, power relations and consumer preferences are among the many factors that need to be orchestrated and transformed in a coordinated way (Paredis, 2013).

STs are driven by cross-collaboration between various actor groups in socio-technical environments such as politicians, society and industries. They focus on innovation, experimentation and learning that cause profound change to a multitude of deeply rooted organisational dimensions including existing infrastructures, cultures and practices (Van Poeck et al., 2020). The conceptualisation of the SDGs across the many dimensions of sustainability are a useful tool when assessing the impact of STs (Williams & Robinson, 2020). STs will be further described in the context of learning as part of section 2.1.

Complexity is a relevant concept to address within sustainability and especially in STs as it interlinks areas such as natural ecosystems, complex systems thinking, shared understanding of problems, as well as the consequences of managing cultures, ethical norms and business practices within organisations (Kay et al., 1999; Tainter, 2006; Senge et al., 2015). Ralph D. Stacey (2002) presents a useful matrix that provides decision makers with the best type of action when faced with issues of complexity, chaos, confusion and simplicity. These stem from the degree of certainty and level of agreement on the issue in question (Stacey, 2002). His model has been used as a reference point to understanding complexity within this paper, whilst

the conceptual paper from Van Poeck et al. (2020) served as the main inspiration for the framework being used in this thesis.

1.2 Context of Study

This paper will navigate through the concept of learning for STs using a real time case study as an illustration. This case organisation is complex public service agency that is motivated to serve a region that has a strategic initiative to engage citizens in creating a sustainable city. It is currently at the beginning of its transition journey and at the stage of implementing a transition lab1 to learn how to learn to achieve their ambitious goals.

1.2.1 Scandinavian Public Service Agencies

The majority of water organisations operate as a public agency (Lieberherr & Truffer, 2014) and the structure is shaped by factors such as decision power, mandates and funding. This presents both opportunities and challenges for STs, which often overlap and are context dependant (Van Poeck et al., 2020).

Public service agencies are traditionally governed by a top-down approach. Such a bureaucratic structure can create tensions between actors, for example policymakers and employees within the public organisation face the challenge of finding a power balance, managing discrepancies in decision making and aligning different priorities (Fischer & Newig, 2016). As a result, policies made on a multi-level perspective are meeting resistance in STs (Gooyert et al., 2016). This is reinforced by a recent claim that STs can only be achieved once policy areas and goals are aligned between the government and public sector actors (European Commission, 2019). Policymaking is highly complex when dealing with uncertain and challenging issues in the field of sustainability. Public service agencies operate under regulated mandates, one of the factors cited for lack of innovation and slow pace of change. As a consequence of these institutional constraints, organisations' flexibility to adapt to demands and the urgency of sustainability is restricted (Lieberherr & Truffer, 2014; Fischer & Newig, 2016).

In addition to this, municipalities traditionally provide funding for public organisations. Recently, the urban water sector is under growing pressure to secure government funding to modernise aging infrastructures (Lieberherr & Truffer, 2014). Of particular focus, it has been estimated that the fees for municipal water and wastewater services in Scandinavia will need to be doubled over the next twenty years in order to meet demands (WSP, 2017). Interestingly, national Scandinavian governments have the jurisdiction to decide their own local taxes and fees (Jörby, 2001). This may be a reflection of the differing priorities resulting in tensions that typically occur during STs.

Policymakers and the public have a co-dependant relationship. Politicians rely on the public to secure re-election and the public rely on the government to provide jobs. This drives municipal attention towards public interests and industry trends which researchers have discovered favour niche start-ups with new technologies and radical innovations over existing engineering and technical services, such as water management systems (Geels, 2012; Fischer & Newig, 2016).

Despite these factors, governments remain a key player in transforming society towards sustainable behaviour (Jörby, 2001). Local Agenda 21 is a set of sustainable development goals

European countries are expected to engage with (Coenen, 2009). Scandinavian municipalities in particular are required to consider the environment in all local activities, specifically each municipality has a comprehensive plan on the sustainable use of land and water (Jörby, 2001). These regulations work in favour of public service agencies striving towards STs.

The case organisation is still at an early stage of learning for ST. This thesis thus focusses only on the internal factors that shape the journey of ST. Even though it exceeds the scope of this analysis and data collection, it is worth mentioning that external factors such as stakeholder interaction, citizen engagement, clear external communication (European Commission, 2019). and relational factors such as trust and transparency (Wieland, 2020) are important factors that should not be overlooked when designing learning processes for STs.

1.2.2 Wastewater Industry

The case organisation operates in two main departments, the management of waste and the management of wastewater in Scandinavian municipalities. The former manages household waste and the latter supplies fresh drinking water, handles storm water and purifies wastewater. The focus of this master thesis will be on the wastewater side of operations as this is where the transition lab will be implemented.

The wastewater industry is facing a multitude of sustainability challenges which are continuing to evolve. First and foremost, water is a finite natural resource that is depleting due to climate change (Setegn & Donoso, 2015). Global warming events such as rising sea levels and extreme weather conditions pose a serious threat to century old physical infrastructures of water systems which are at their limit (Polonenko et al., 2019).

Additionally, an increase in the population concentrated in cities means water systems are struggling to cope with higher amounts of wastewater and increased demands for clean water. With this urbanisation comes a change in lifestyle habits which water management systems are unprepared for. Household and cosmetic items containing hazardous chemicals and micro-plastics are regularly flushed into the water system causing blockages and water contamination, both into drinking and sea water (Koelmans et al., 2019).

Overall, this multitude of modern-day sustainability challenges has been recognised as a threat to the management of safe water systems globally.

1.3 Previous Research

This chapter provides an overview of the relevant research on the concepts that form this thesis. It will begin with an exploration into the academic discourse on organisational culture, then organisational learning, followed by sustainability transitions. These three concepts were chosen to determine what factors influence STs. Assessing the organisational culture helps to understand the foundation and landscape through which the ST will occur, following on with understanding how deeply rooted learning currently is within the organisation, and lastly analysing organisational capabilities through the lens of specific factors for learning. These all must be taken into consideration when designing processes for STs.

1.3.1 Organisational Culture

The concepts of organisational learning and organisational culture are closely interlinked. Some say that having the right culture is a prerequisite to becoming a successful learning organisation (Greigo et al., 2000; Arumugam et al., 2015). Much research within the discourse of STs explores how transitions can change deep rooted cultures, however it remains to be investigated what effect the existing organisational cultures have on STs (Arumugam et al.,

2015). Coenen, Raven, and Verbong (2010) published a study addressing how localised cultures influence transition experiments, whilst Wirth, Markard, Truffer, and Rohracher (2013) explore how culture can constrain and enable change, such as STs.

Despite the widely recognised difficulty to analyse and measure culture, there are many established methods. House’s GLOBE Study (House et al., 2004) and Hofstede’s Six Dimensions of Culture (Hofstede, 2011) both include research into what effect society has on culture in the workplace. Another example is Schein’s Culture Triangle (Schein, 2016) which can be used a foundation to characterise and assess corporate sustainability strategies in relation to his levels of organisational culture, artefacts, exposed values and underlying assumptions (Baumgartner, 2009). For this thesis the emphasis is on the Competing Values Framework (CVF) which will be discussed in section 2.3 (Quinn & Cameron, 2011).

Literature recently acknowledged that organisational culture is a success factor for organisational change towards sustainability (Long et al., 2018), thus further analysis bridging organisational culture and STs is needed.

1.3.2 Organisational Learning

The capacity to continuously improve and change to meet the ever-evolving environmental challenges of today is linked with an organisation’s capability to learn (Senge, 1990). Due to the complex and heterogeneous nature of this research stream, organisational learning has a variety of definitions (Sun & Scott, 2006). One encapsulating definition is “a multilevel process where members individually and collectively acquire knowledge by acting together and reflecting together” (Scott, 2011, pp.1). An organisation’s capability to learn offers numerous benefits such as a competitive advantage (De Geus, 1998; West & Burnes, 2000), responsiveness to change (Feola, 2014), increase in capacities (King, 2009), continuous transformation (Agarwal & Garg, 2012) and an increase in employee knowledge about the organisation (Brockmeier, 2002). Though despite its relevance to organisations, organisational learning can be seen as a concept that remains difficult to implement, due to a myriad of definitions and limited practical guidance (Garvin et al., 2008).

Only in recent years have scholars researched learning as a condition for sustainable change. Organisational learning, collaboration and room for experimentation are needed to create sustainable change (Senge et al., 2008; Senge et al., 2010; Senge & Goleman, 2014). The concept of organisational learning has been explored from the lens of creating a more sustainable world (Larsson & Holmberg, 2018; Sol et al., 2018; Ingram, 2018), creating conditions that enable systemic change (Geels & Schot, 2008), approaching the complex nature of STs (Bocken et al., 2018), enhancing societal intelligence (Brown et al., 2003), accumulating and sharing knowledge (Domènech et al., 2015; Beers et al., 2016) and the governance of ST processes amongst actors (Loeber et al., 2007). Furthermore, organisations should focus on their operational aspects and organisational context in order to tackle environmental variables (Orsato et al., 2017).

Within the theoretical discourse about organisational learning, there exists a variety of different approaches. For example, Kolb’s Model of Experiential Learning (Kolb, 1984) which is concerned with individual cognitive processes, Ellström’s Five Factors Enabling Learning at Work (Ellström, 2001) analysing the learning relationship between managers and subordinates, and Senge’s Five Disciplines (Senge, 1990) which identifies five factors that shape a learning organisation. The most relevant to this study is the Three Loops of Learning (TLL) model which will be discussed in section 2.2 (Argyris & Schön, 1974).

1.3.3 Learning for Sustainability Transitions

Learning connects with the core idea of transition studies and plays a key role in STs. As it is strongly related to the experimental and action-oriented nature of the broader body of transition studies literature, it is often mentioned as a governance tool or relevant steering mechanism (van Mierlo et al., 2020). Even though there is an interdisciplinary discourse about the importance of learning for sustainable development and STs, there exists limited knowledge of how the learning is actually designed, how it occurs and its long-term sustainable impact (Williams & Robinson, 2020). Existing research highlights that the concept of learning is still rarely clearly defined and hardly elaborated in this context (Gerlak et al., 2018; van Mierlo et al., 2020). The majority of empirical studies stay implicit in regard to the underlying conditions of learning – a challenge that can even be seen in the field of (social) learning research (Scholz & Methner (2020), van Mierlo et al., 2020; Vinke-de Kruijf, et al., 2020). Transition studies on the other hand see learning as one of several components that impact early stages of change within complex transitions (van Mierlo et al., 2020). Thus, insights from transition studies can assist in understanding the impact of learning, but limited statements can be made about how learning happens in the context of STs. In general, there are many different approaches when researching the field of transition studies. Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and Avelino (2017) grouped these into socio-technical, socio-institutional, and socio-ecological. The first approach investigates innovation and its relation to science and technology, the second explores transitions under the influence of societal systems, and the last, perhaps most relevant to this study, draws attention to transitions in ecosystems and the impact of society. As the extent to which learning can lead to holistic systemic change is very dependent on societal and institutional factors that are outside the control of individuals (Vinke-de Kruijf et al., 2020; Beers & van Mierlo, 2017; Halbe & Pahl-Wostl, 2019), further research that includes factors such as the adapted Four Factors of Learning for ST model from Van Poeck et al. (2020) that will be used in this thesis, can enrich the existing knowledge. In their conceptual paper they suggest analysing the following the Four Factors of Learning for ST: intrapersonal factors, interpersonal factors, institutional factors and material factors (Van Poeck et al., 2020). Overall, learning for STs is perceived “as a process of acquiring and generating new knowledge and insights, and of meaning-making of experiences in communicative interaction, in a reciprocal relationship with the social, (bio-)physical and institutional context” (van Mierlo et al., 2020). It can be seen as a non-linear and iterative process that reflects upon existing ideas, encourages experimentation and supports the development of new collaborative actions (van Mierlo et al., 2020). There is an acknowledged research gap in the field of organisational learning within STs (Köhler et al., 2019; van Mierlo & Beers, 2020; Van Poeck et al., 2020). Thus, better understanding the questions of how and why organisations engage in learning for STs would enrich the academic discourse of STs and thus needs further academic research.

1.4 Problem Statement

The failure of urban water governance is cited as one of the contributing factors to this global water crisis which has triggered new environmental regulations (IPCC, 2019; World Economic Forum, 2018). Such changes are challenging for traditional and technical public service agencies as they have limited resources and are highly formalised and regulated (Bos & Brown, 2012). Changing deeply rooted values, cultures and norms is a complex process with organisational learning being able to open up possibilities for change through reflecting and rethinking ways of working (Van Poeck et al., 2020). In the context of STs, one of the first stages is learning and critical reflection, thus it is important for organisations to understand how they can

embrace and implement learning to make organisational changes for sustainable development. Within literature, learning is often discussed however less frequently put into action. Furthermore, research in STs is at an early stage and seldom embeds learning. Consequently, this thesis simultaneously addresses two research gaps in the context of learning for ST. Firstly, how learning processes can be put in action and secondly, how this process is shaped in ST and especially in the context of public service agencies.

1.5 Research Aim and Contribution

Further research within the field of change for sustainability is critical in working towards the goals of Agenda 2030. This paper will navigate through the complexity of sustainability and lack of guidance into how organisational learning can be implemented, with an aim to enriching the current state of literature in learning for STs. Moreover, this paper contributes to the discourse about the Three Loops of Learning through applying the framework in the context of public service agencies in transitions phases. Furthermore, it tests a newly suggested framework that assesses Four Factors of Learning for ST (Van Poeck et al., 2020).

In addition, understanding the journey of STs and the specific facilitating and hindering factors of organisational learning is of high relevance for designing future ST processes that are both efficient and effectful. Therefore, in addition to enriching literature, this thesis further aims to explore the process of STs and how it can be facilitated through organisational learning to create responsive public service agencies that take an active role in shaping a more sustainable future. As a result, this paper contributes recommendations and an outline for future research that informs academics and practitioners on a local, regional and national level.

1.6 Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of the thesis is to discover what facilitates and hinders organisational learning for sustainability transitions. Inspired by the Four Factors of Learning for ST framework (Van Poeck et al., 2020), this thesis will focus on the following three research questions and will be answered through a case study in the public service sector.

RQ 1. What are the most prominent Four Factors of Learning for ST (intrapersonal,

interpersonal, institutional and material) that occur during sustainability transitions in a Scandinavian public service agency?

RQ 1.1. What are the most influential themes found within the Four Factors of Learning

for ST within a Scandinavian public service agency?

RQ 2. What are the conditions for Three Loops of Learning for Sustainability Transitions within

a public service agency in Scandinavia? 1.7 Structure of the Thesis

The remainder of this thesis is structured into the following chapters:

• Chapter 2 discusses the theoretical background and introduces the reader to the central concepts that ground this research study. They are Organisational Learning in Sustainability Transitions, the Three Loops of Learning model, the Competing Values Framework and the conceptual frame, the Four Factors of Learning for ST.

• Chapter 3 introduces and defends the methodology employed for both the data collection and data analysis which takes a qualitative approach. It also shows the adapted

conceptual frame inspired with factors from the aforementioned concepts. The validity, reliability and limitations are included here.

• Chapter 4 is the descriptive analysis of results taken from the coded interview and document data. It reveals the main themes under the Four Factors of Learning for ST, followed by an analysis into the most prominent themes identified in relation to the Competing Values Framework, need for change and complexity, conditions for learning and the Three Loops of Learning.

• Chapter 5, the discussion, reviews the analysed data in conjunction with the literature and theoretical framework. It begins with the frequency of the Four Factors of Learning for ST followed by a more detailed discussion into each specific factor. It then discusses the predominant factors that facilitate and hinder learning for ST which have been grouped into five identified themes.

• Chapter 6 is the conclusion which is divided into limitations, future recommendations for practice and future research, and a final summary of the thesis paper.

2. Theoretical Background

This chapter introduces the most relevant concepts and theories presenting a frame for the analysis to ultimately address the research questions. Under the context of STs, these are organisational learning supported by the Three Loops of Learning model, the Competing Values Framework and the adapted conceptual framework, the Four Factors of Learning for ST.

2.1 Organisational Learning in Sustainability Transitions

The level of complexity in the developing field of sustainability requires different business processes and ways of working to generate innovative solutions (Beers et al., 2016), calling into action organisational learning. Research demonstrates that learning occurs at an individual, group and organisational level to create an environment that fosters successful integration of sustainability (Cramer, 2005). To support this, Beers et al. (2016) see learning processes as critical in stimulating STs, whilst Domènech et al. (2015) claims that learning processes determine the pace and focus of STs. There is limited literature on learning processes and how they can be made more tangible and implemented in an organisational setting. Therefore, this study will explore learning as a prerequisite for implementing STs in public service agencies through conducting a case study in Scandinavia.

The research field of STs evolved around two decades ago and is shaped by an interdisciplinary perspective. Concepts such as transition management (Rotmans et al., 2001; Geels & Schot, 2007; Loorbach, 2010), strategic niche management (Kemp et al., 1998; Van der Laak et al., 2007; Kemp & Loorbach, 2006), multi-level perspective (Rip & Kemp, 1998; Geels, 2002; Smith et al., 2010), and technology innovation systems (Bergek et al., 2008; Markard et al., 2015) are among the most researched areas in this new field.

The growing interest of researching STs is to address wicked sustainability problems which are characterised by complex environmental and social challenges such as climate change, resource depletion and loss of biodiversity (Rittel & Webber, 1973). These challenges are evoked by unsustainable production and consumption patterns within socio-technical systems. Examples for socio-technical systems can be seen in sectors such as energy, water management, building, agro-food and mobility (Köhler et al., 2019). As traditional approaches and processes do not address these challenges sufficiently, there is a need for deep rooted “learning as a vital means of creatively transforming unsustainable regimes” (Van Poeck et al., 2020, pp. 298). Instead of incremental changes and technological advances, radical shifts towards new forms of socio-technical systems are needed. These can be described as STs (Elzen et al., 2004; Grin et al., 2010).

2.2 Three Loops of Learning

As mentioned earlier, this paper will use the Three Loops of Learning (TLL) model as a framework to analyse the process of learning for STs. The TLL framework (Kolb, 1984; Argyris & Schön, 1974) consists of several iterative cycles which can be distinguished in three types of learning loops that reflect different levels of organisational effort and depth of learning. It is most relevant to this study as organisational leaning is less explicitly conveyed in practical terms within literature yet is extremely relevant for the first stages of organisational changes or transitions. By applying an approved model to the study, a strong foundation can be set when analysing learning in the context of STs. Specifically, the model analyses and evaluates an

organisation’s underlying assumptions and norms, which is notoriously difficult to assess yet an important stage of change (Odor, 2018).

The first and most common one is the single loop learning, as it is easily adopted and facilitated (Argyris & Schön, 1974). It is based on detecting and correcting errors through using established rules, procedures and actions (Hargrove, 2002). Driven by the motivation to find more efficient ways of working, this approach aims to improve the application of existing rules and procedures. It can be seen as the first layer of problem solving and is practiced through fixing problems by using the existing toolbox. The single loop learning process is thus shaped by the underlying question of “Are we doing what we are doing right?” (Tosey et al., 2012). This leads to a ‘thinking in the box’ process, focussed on learning from solving problems to adapting the response accordingly.

Double loop learning is based on the principle of error detection and correction, but additionally aims to trace back the underlying causes of the problem (Argyris, 1976). It is most applicable in situations where the existing rules and procedures do not fit the new challenge, triggering the question of “Are we doing the right things?”. This learning style goes beyond problem solving, it re-evaluates or reframes not only rules and procedures, but questions the underlying organisational values and beliefs (Peschl, 2007). Through learning to understand the process and reflecting upon improvements, double loop learning encourages innovation and ‘thinking outside the box’ (Peschl, 2007). This mostly results in more effective processes through new knowledge and insights that inform the rules and procedures. An example of learning outcomes would therefore be changes in the knowledge base of an organisation, modified objectives or new governance structures and policies (Argyris & Schön, 1974). The third learning type is the triple loop learning, which is seen as an important foundation for profound change. Triple loop learning is characterised by a reflection of the core values, purpose and principles, which serve as a context and foundation of (organisational) processes. Through taking a deeper look at the question of “How do we decide what is right?”, a triple loop learning approach has the ability to ‘think about the box’ and question existing power structures, or governance protocols (Armitage, Marschke, & Plummer, 2008). Examples of intended learning outcomes are changes to defining principles such as the renewal of learning strategies or the identity and mission of an organisation (Peschl, 2007). Triple loop learning is of a complex nature and can be difficult to achieve, predominantly because it is concerned with the individual on an existential level that addresses aspects such as the person’s habitus, values, attitude or personality traits (Peschl, 2007).

2.3 Competing Values Framework

The complex nature of modern-day organisations accentuates the significance of culture in managing organisational change. Research that explores the dynamics between STs and culture highlights the importance to analyse, evaluate and adapt corporate culture as it shapes the process of learning. Only when an organisation can diagnose and understand the culture, can it facilitate meaningful change (Cameron & Quinn, 2006; Geels, 2012).

For this paper, the Competing Values Framework (CVF) originated by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) is most relevant. It analyses the beliefs, values and assumptions of employees as well as the way they think and process information which can lead to conflict and cause tensions (Ostroff et al., 2003). These factors are categorised into four clusters which each have a customised set of organisational and individual factors that can be implemented in a practical way; the most effective leader type, value drivers and theories of effectiveness (Cameron &

Quinn, 2011). This model is useful to consider in this study as organisations should first be aware of their existing culture before embarking on a major change such as an ST. Their position on the grid, which can be found in Cameron and Quinn (2011), helps to identify how they work best, ergo how to approach organisational change. Once these conditions are distinguished, the organisation can pre-determine how far they can transition in certain time periods and create a customised set of interventions.

The CVF will be used to help frame the organisational culture in context to this research study. Through an initial analysis of the organisation, the case has been classified into the hierarchy climate. This archetype is concerned with structure and formalisation. The collaborators found in this cluster enjoy rules, efficiency, accountability and clearly defined decision-making authority which all lead to predictable outputs. The factors specific to this dimension influence organisational control and organisational learning, thereby assisting in the later analysis to discover factors that facilitate and hinder organisational learning (Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Lavine, 2014).

2.4 Four Factors of Learning for ST

Scholars agree on the importance of integrating learning for the process of STs, yet a lack of practical application has been recognised. A recent publication by Van Poeck et al. (2020) identifies relevant questions for future research about how learning processes could be designed and facilitated. These range from, why is learning regarded important or necessary, to how the process could be described, where the learning would take place, how this could be conceptualised and which theories and research gaps should be considered (ibis, 2020). Early research in this field suggests that aspects such as societal intelligence, creativity, and learning settings can have a huge influence on the learning journey and learning outcomes (Brown et al., 2003; Sol et al., 2018; Larsson & Holmberg, 2018).

In addition, they conduct a thorough literature review of learning for STs and create a framework based on an analysis of 20 of the most relevant publications. It highlights key concepts that should be considered when designing ST processes in order to create an environment that supports organisational learning for STs. The first factor is intrapersonal which includes the sub-codes of the participants’ existing knowledge, previous experiences, opinions, ideas, emotions and routines. The second factor is interpersonal which incorporates the social interactions between the persons involved in a particular situation, looking at communication, dialogue, negotiation and deliberation. Thirdly is the institutional factor which sub-codes look at the influence of elements beyond the specific interactions in a concrete situation such as narratives, cultural traditions, discourses, epistemological beliefs and world views. The last one is the material factor, which analyses unpredictable elements such as artefacts, the natural environment, infrastructures, technologies and the body (Van Poeck et al., 2020, pp. 306).

3. Methodology

This chapter will reflect upon the selected research design and chosen methods best suited to this paper. It will then, alongside aspects such as reliability and validity, critically reflect on limitations and potential biases.

3.1 Research Approach and Design

A careful choice of the research design is the foundation for high validity of the results (Schnell, Hill & Esser, 2008). Since organisational learning and STs are both recent and evolving research concepts that has not yet been sufficiently conceptualised nor bridged together, coupled with no previous studies specifically analysing factors within public service agencies, a qualitative approach with an exploratory character was chosen to better understand the context of this initial study. The work therefore unfolds in the field of empirical social research and has both a descriptive and an inductive-creative element. This research design stands for flexibility, openness, comprehensive information content and later interpretation options, but needs to be backed through a structured and transparent documentation of the research process (Cresswell, 2007). Using an organisation as a case study behaves a lens that allows the author to pay more attention to the theories and concepts used in this study (Silverman, 2015). The findings can nevertheless inform other organisations about the important themes when learning for ST.

The methods employed for this paper are semi-structured expert interviews for the primary data collection, and a qualitative software programme for the data analysis. These were chosen as semi-structured interviews gather first-hand, in-depth personal experiences and opinions and allow the respondent to talk freely, followed by open-ended questions that make room for further exploration (Clough & Nutbrown, 2007). The qualitative software, MAXQDA, provides opportunities to create themes and code the data under the relevant theories and concepts in a visual and understandable way.

3.2 Data Collection

Primary data from semi-structured expert interviews with middle-management, and secondary data from organisational document analysis serve as qualitative data methods to highlight and seek further understanding of the phenomena of organisational learning for STs (Justesen & Mik-Meyer, 2012). This method was employed to best fulfil the aim of this thesis, to explore the level of perceptions, acceptance and understanding of STs within an established organisation who is at an early stage of embedding sustainability. Furthermore, it is of interest to investigate the current and preferred organisational environment in which it will take place. Such a research method limits the ability to generalise the research as the findings are specific to each individual (Smith & Osborn, 2007). This qualitative exploration is needed in early stages of research to understand the phenomenon of STs (Smith & Osborn, 2007), yet future quantitative research would be needed to verify the results in a larger data set.

The data collection process began with connecting to an organisation, through a professional network, that was selected due to academic interests in organisational learning. To gain a solid knowledge foundation, an extensive review of most recent academic literature was conducted to discover what research already exists in the field of STs, bridging it with the concept of organisational learning and then circulating into the context of public service agencies. Having identified a niche gap and aligning with the organisational project, the conceptual framework was grounded using the Three Loops of Learning and the Competing Values Framework

theories. The framework was then adapted to create a new perspective and to include a personal voice, deriving inspiration from the Four Factors of Learning for ST (Van Poeck et al., 2020) and further enriched with sub-codes inspired by relevant literature and the two theoretical concepts to narrow the research into a specific stream. The codebook was designed by the authors to include some original and adapted factors (see chapter 3.4 and Appendix A). The framework was tested through peer discussion and a pre-test of the questionnaire. An initial CVF assessment was made using organisational documents and the company website to place them in a culture type. Primary data was extracted through conducting a total of seven semi-structured interviews with middle management who were selected in collaboration with members of the organisation who are assigned to working with learning for ST. All interviews followed the same structure and were conducted within the period of May to June 2020. They were all conducted via online video calls due to the accessibility of respondents and each gave their consent for the interview to be recorded and the data used anonymously in this thesis. A total of three company documents were analysed to supplement the interview data which were chosen in collaboration with the project contact and supervisor. The case organisation is a Scandinavian public service agency within the range of 250-500 employees, with an aim to becoming a leading actor in sustainability, working in close connection with the municipality and actively engaging citizens. The project this thesis follows aims to create a partly owned internal and external transition lab that will work with specific projects from a chosen department in order to see how learnings can be extracted and circulated back into the organisation.

3.3 Data Analysis

Thematic content analysis using an online software allows more ease for the data to be coded methodologically (Houghton et al., 2013). The company documents and the fully transcribed interviews were uploaded into MAXQDA, the chosen software for qualitative and mixed methods research. The interview and document data were then themed adhering to the codebook using the software. The documents and transcripts were read twice by each author to ensure all useful data was accurately coded. Then followed the descriptive analysis by clustering the themes into emerging patterns, which are mainly informed by the existing framework or extracted through an inductive process. This collaborative process explored how the data contributes to research by discovering how learning actually occurs and applying it to a more general setting. Afterwards, the implications of the study were discussed to find out what can be learnt and what would be interesting to further analyse in future research. 3.4 Adapted Conceptual Frame

To better customise the above-mentioned framework for the specific interest of organisational learning processes in the case study of a public service agency focused on integrating sustainability, it has been adapted. The same four factors of learning for ST have been kept as an overarching structure however have been enriched with further sub-codes, the reasoning will be described below. These sub-codes are based on previous academic research as well as concepts from the Three Loops of Learning and Competing Values Framework which are established frameworks from related research fields. The TLL helps to identify the existing learning capabilities of the case organisation whilst the CVF helps to assess the specific culture and the conditions for which the organisational learning will take place. This paper aims to add to the current research in learning for STs, through applying these models to get a better understanding about how the concept of learning can be translated into action.

Figure 1: Learning for Sustainability Transition (developed by the authors of this thesis, inspired by Van Poeck et al., (2020), Argyris and Schön (1974) and Cameron and Quinn, 2011)

To get a better understanding of the concepts, factors and underlying codes of the adapted framework. The codebook (appendix A) that is used as a guideline for the descriptive analysis is explained in the following paragraphs.

Intrapersonal factors are highly based on the individual’s earlier experiences which shape their process of learning (Godelnik, 2017). Traditions can greatly affect the ability to respond to changing environments, therefore was added in order to analyse individual patterns of working (Van Poeck et al., 2020). Creativity is often described as an individual attribute that in turn determines the organisations level of creativity and ability to innovate, an important factor in STs (Ingram, 2018). Finally, the mindset of employees is a vital component to any organisational transition, making it important to highlight and possible to code within the interview data (Godelnik, 2017).

Interpersonal factors are predominantly based on the interactions between individuals that shape the learning process (Beers et al., 2016). Collaboration, also known as collective problem solving (Wiek & Kay, 2015) is important to observe in this study as the process of STs and learning cannot be done alone. Narratives, originally found in the intrapersonal factors, and storytelling are important to explore as interactions enable learning and communication must be clear so that employees understand the rationale behind the change and how it will be executed (Van Poeck et al., 2020). The sub-codes of leadership and responsibility were added as managers typically initiate and drive the change process (Boon & Bakker, 2016). Finally, frequent critical reflection and thinking help organisations to challenge the status quo and find new ways of working that foster learning (Van Poeck et al., 2020).

Institutional factors are described as the cultural tools that mediate learning (Ingram, 2018). Values was added as a sub-code alongside the existing codes of culture and beliefs as they set the environment for which the ST takes place and are often overlooked (Hodkinson et al., 2007).

Material factors are explored from the perspective of how people engage with their surrounding environment which influences learning (Jalasi, 2018). The use of resources was added as these have a direct effect on organisational change and learning (Reed et al., 2010), politics which is heavily relevant when exploring public service agencies (Van Poeck &

Intrapersonal Factors Material Factors Institutional Factors Interpersonal Factors Four Factors of Learning for ST

Learning for Sustainability Transition

Competing Values Framework

Three Loops of Learning

Östman, 2018), and society, whom are one of the most influential players in creating collective intelligence for long-lasting sustainable change (Brown et al., 2003).

The TLL concept helps to understand the degree and level of learning, aspects that help assessing the stage of STs. Thus, aspects such as reflection, evaluation, power structure, justification, fundamental purpose, core values and identity where chosen as indicators for the Three Loops of Learning (Argyris and Schön, 1974).

The case organisation was identified as belonging to the hierarchical culture type. This judgement was made from an analysis of company documents and background research about the organisation. They are owned by the government and thus are shaped by a bureaucratic and hierarchical structure with a high degree of formalisation. This is typical for a public service agency thus broadening the relevance of this study. Additionally, they are a technical organisation, therefore have very predictable outputs and a task-orientated mindset (Document 1, 2). Adapted from the CVF framework (Cameron & Quinn, 2011), the conceptual frame has been deepened with the sub-codes of structure, formalisation, rules, efficiency, accountability, clearly defined decision-making authority and predictable outputs.

Altogether, this adapted conceptual framework aims to test and identify the underlying factors of and for learning for STs.

3.5 Reliability and Validity

Attention has been given to ensure a level of consistency and internal reliability in this study. The first potential issue to be discussed is expert selection. This study relies on seven experts interviewed from the case organisation. To ensure the respondents’ statements are true, the authors used document analysis to further verify and strengthen answers given, this is also known as triangulation (Jick, 1979). The second potential breach of reliability to be discussed are biases. Firstly, any researcher bias during interview conduction has been limited by using a pre-selected semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix B). This creates a structure to which the interviewers must adhere to, ensuring fairness and consistency in each interview therefore heightening the reliability of this study. Secondly, any potential researcher biases during the analysis have been counteracted through creating a detailed codebook based on established theories and concepts. The codes were selected in collaboration with both authors to verify their importance and further enhancing the reliability of this thesis.

Validity refers to the extent to which the interpretation of data accurately represents the truth (Litwin, 1995). Firstly, the design of one’s questionnaire can greatly affect the validity of results (6 & Bellamy, 2012), and so this potential issue was eradicated through a pre-test of the questionnaire with fellow master students. This process helped to clarify and refine the set of questions to more accurately suit the aim and context of this paper. Secondly, the authors critically reflected upon the questions of, are we testing the right thing and using the right models. The main point of reference that guides this thesis is the Four Factors of Learning for ST model that has been published in a peer reviewed journal, however, has yet to be tested in other academic literature due to the recent timing of the publication. To counteract this potential validity issue, the model was enriched with insights from other peer reviewed articles and established concepts such as the Three Loops of Learning and the Competing Values Framework. Ethical considerations were taken into account through the anonymity of the organisation and the respondents who gave verbal consent to use the recorded data.

3.6 Limitations

Several limitations have been considered throughout the duration of this thesis. Firstly, only a total number of seven interviews were conducted which may limit the range of data collected. In addition to this, the complex phenomena of organisational learning and sustainability transitions may not be understood by all respondents. In response to both of these potential limitations, the seven interviews were conducted with people who are newly involved in, or have experience with, transition labs. This guarantees that despite having a limited number of responses, they will be most sufficient to conduct a thorough thesis. However, it cannot be discounted that preconceptions of the concepts may occur in the interviews.

In relation to the above, the case organisation is at an extremely early stage of implementing a transition lab which is not yet established or functioning. Therefore, data from the respondents may be limited as some may have no prior knowledge of this subject. Even though mainly being driven by subjective perceptions, this perspective is useful during this stage of investigation as it explores how to implement learning in order to create an ST.

Thirdly, the identified themes and patterns discussed in the descriptive analysis can be down to the authors’ interpretation of results. Thus, wrong conclusions may have been drawn. To counteract this, the results follow the data rather than opinion, to stay as objective as possible. Furthermore, the qualitative data system MAXQDA allows methodical coding to accurately capture the interviewees understandings and opinions on the phenomena in question. This is in line with the codebook, which was rigorously adhered to, and was legitimised by tested models and theories. Lastly, the description of the data will be both direct quotations and paraphrases to ensure no information is misconstrued.

Finally, the interviews were conducted via Zoom, an online video call platform, which can bring limitations to the quality or even misinterpretation of interaction as external environment elements such as body language are disregarded. There is a less personal aspect to online as opposed to face-to-face which is extremely well researched and concluded to be far superior when conducting interviews (Daim et al., 2012). However, a positive aspect to online interviews is that the respondents were at home or in the office therefore in a familiar and relaxed environment to perhaps share more personal thoughts as well as being less concerned with time restrictions since the obstacle of travel was removed.

4. Descriptive Analysis

This section of the paper will present a descriptive analysis of the data. This was extracted from a case study of a public service agency in Scandinavia who are currently implementing a transition lab in order to fulfil the goal of being a leading actor in sustainability. The data highlights areas of importance in relation to this study and exploring the results in relation to the framework and chosen concepts. It begins with an insightful exploration into the Four Factors of Learning for ST, pinpointing the most influential sub-codes that reoccurred in the data. It then moves onto organisational learning under which an analysis of the most prevailing themes for the Competing Values Framework, need for change and complexity, conditions for learning. Additionally, the Three Loops of Learning will be analysed to discover what loops the case organisation already incorporate and which conditions need to be fulfilled.

4.1 Four Factors of Learning for ST

The four factors of learning for ST will be explored in order of intrapersonal, then material, followed by institutional and lastly intrapersonal. The words found in bold are the sub-codes that can be found in Appendix A.

4.1.1 Intrapersonal Factors

As discussed in chapter 2.4 and 3.4, intrapersonal factors help to analyse STs within organisations on an individual level. Middle management perspectives from the interviews and general data from the documents have been grouped into themes and summarised below. The first and foremost theme that occurred was mindset. The data shows that public service agencies within the field of maintenance have very fixed routines and a technically driven mind. This is partially influenced by the traditions of working, for example with numbers and permits and the managing expectations between the many external actors that are involved in public service agencies. It was highlighted that employees often feel frustrated with the slow pace of change in such an industry. At the same time, they feel “stressed in everyday [working] life” (Respondent 1) by having to carry out fundamental maintenance tasks whilst being expected to find new and more efficient ways of working to achieve sustainability goals (Respondent 3). The need for innovating existing routines and day-to-day operations can cause resistance as it pushes employees “towards an area where they feel uncomfortable” (Respondent 3) which can make change difficult to embrace.

From the document analysis, public administrations have historically had a strong tradition of doing things in the “right” way which limits room for experimentation. The interview data further supports this by stating that technical environments can hinder the level of organisational creativity as employees are more focussed on always doing the right thing as they have always done, which “is a beauty in many aspects but sometimes it can hold us back” (Respondent 7) from trying new things.

This is closely linked to the theme of self-reflection. The data revealed that employees do reflect on potential learnings from previous project and work experiences as part of an iterative learning process. This is done through having regular meetings and evaluating previous experiences to identify future areas for improvement. However, it was cited that individuals lack the “courage to test and introduce new techniques” (Document 2), suggesting that change is in the early phase of discussion rather than action. The interview data reinforces this by expressing that individuals need support and guidance from management as “they don’t

know how they can contribute to [the organisations] sustainable development” (Respondent 7). It was further highlighted that individuals can sometimes look through their departmental lens which creates a narrow view and low level of interest on topics that do not concern them (Respondent 7).

Under the theme of opinions and ideas, the data revealed that there is a general understanding within the organisation about what a transition lab or an ST might be, however the term remains vague and employees have different interpretations and expectations. The organisation does value the opinions and ideas of employees as there is “lively ongoing forms of evaluation” (Respondent 3) between managers and co-workers.

The theme of emotions was less frequently discussed; however, the data did show that “there is a proudness of working with and serving the community with very important functions” (Respondent 3) and are strongly committed to protecting the resource they are working with. However, it was discussed that individuals may not have the relevant existing knowledge to support and drive change within an organisation that is in the early stages of embedding learning for sustainability into organisational logics. Their existing skill set is extremely well suited to the technical side of operations (maintenance) which they have been doing for so long, therefore there is a tendency to “fall back into their own old positions” (Respondent 7) and routines.

4.1.2 Interpersonal Factors

From the interview and document data, the following section analyses the level of interaction between actors from the perspective of middle management. This data was supplemented by general company-specific internal and external documents. Interpersonal factors have been clustered into themes that align to the framework.

Communication was frequently cited making it a critical factor for organisational learning. Internally, frequent and transparent communication delivers a multitude of benefits, for example “a functioning relationship between manager and employee” (Document 1), a clear understanding of the (sustainability) goals to better align business strategies, learning from previous successes and failures and showing how the departments can work together. Externally, communication plays a key role for public service agencies in influencing society and “changing the behaviour of inhabitants” (Document 1) towards sustainability through clear communication and education. One example from the data emphasises the importance of accessible communication through the use of “materials, symbols, images…posters, artefacts, stories, photos” (Document 1) to reach diverse and often excluded members of society. The organisation is unable to have someone from the communication department in every project team due to limited resources, restricting the ability to share knowledge and experience between each other to embed organisational learning.

Collaboration is a closely linked theme. The data states that collaboration should permeate the entire organisation and is needed to achieve the necessary organisational development and “is the path to success and one sustainable future” (Document 2). Strong collaborations can initiate new working processes, develop innovative services and promote creativity. However, the case organisation has a vertical and rigid structure typical for a public service agency, describing the departments as working in “constellations” (Respondent 7) and separate project teams. This can hinder an organisations ability to implement a transition lab which is said to promote creativity, learning and collaboration. Expectation management between collaboration partners was discussed as a theme, explaining that organisations should provide

the necessary resources and space that mobilise decision making that manage the different levels of ambition. Collaborations with external actors is common for public service agencies, a strength identified in the case organisation as having good working relationships with other municipalities. Paradoxically, this same level of co-creation is also seen as a hinderance as proposals and referrals must be approved via governmental committees in a two-stage process.

The use of narratives and dialogues were discussed from different perspectives. The first to be discussed is the overall organisational ‘voice’. When dealing with complexity on a large scale, the organisation has to be aligned and share the “same definition of sustainable development” (Respondent 5). This is important to create efficiency and cooperation when working together internally, as well as creating a strong external reputation of having a united front rather than being seen as a number of different small businesses each with different agendas. The data further indicated that when an organisational narrative begins shifting towards being more sustainable and responsible, the entire organisation should “talk the same language, or use the same phrases” (Respondent 6). Once these areas are aligned, the organisation has the momentum to push forward sustainable development.

The second narrative perspective is from a leadership point of view. One example given was the power of a personal voice in leading and sustaining change. The data told of a former CEO who had high ambitions for the organisation to be completely sustainable, an energy which can still be felt throughout the organisation today. A strong narrative from “brave leaders who are quick-footed” (Document 2) can thus be the initial force to stimulate fruitful change towards sustainable business practices. In addition, the organisation is aware that leadership is something that needs to be addresses while development processes are reviewed (Document 1). Leadership was further explored through the lens of support and trust between managers and employees as a “basic prerequisite for functioning labs” (Document 1). Such relationships allow for honest exploration and problem solving through active participation, sharing knowledge, experience and resources. The process of change can be challenging and so an established leader should be able to “support co-workers in moving and changing their way of working and acting” (Respondent 3) as well as having the capabilities and methods can resolve conflict which often arise during such uncertain times.

Closely related is the theme of responsibility. Managers have to make decisions that are in line with the rest of the business and follow the correct mandates whilst taking responsibility for the associated risks. During an ST, there is an additional responsibility to “focus both on maintenance while developing new ideas and inventing” (Respondent 3). The information flow within the organisation is dependent on the quality of communication from the managers to the employees, which the interview partners stated may differ. Responsibility also lies with employees gain clarification on their role during an ST. However, this is difficult when one is working on multiple projects therefore “there can be some confusion about your role and where your base is” and “who is your boss” (Respondent 6) which can interfere with conscious decision making.

Summarising the data, critical reflection from an organisational point of view is needed to explore how innovation projects should be put into operation, support organisational changes and question together whether activities are conducted in a smart way that support the goals. It was clear from the data that the organisation is aware that critical reflection is important and have methods for implementing, for example cross departmental reflections with the board and monthly meetings between managers and co-workers that facilitate active learning

(Document 1, Respondent 2, 3, 7). Nevertheless, there remains room for further improvement and more regular evaluation processes.

4.1.3 Institutional Factors

The institutional factors for learning for STs consist of organisational culture, beliefs and the added code of values. All three aspects were covered in the data (interview and document) with differing frequencies which will be demonstrated below.

Organisational culture was the most prominent code found in the data. Within the case organisation and like many other public service agencies, the majority of employees are engineers which “says a lot about what kind of logics and cultures you have in play” (Respondent 3). As previously discussed, they have done things the same way for many years with little reason or incentive to try something new, thus creating a deeply rooted and perhaps rigid hierarchy culture that is difficult to change. In addition to this, public service organisations are managed in a traditional way under a hierarchical governance model, enforcing a culture that sets development and innovation in contrast to operation and management. Yet the interviews show that the organisation is taking proactive steps as they have a desire to “create a development-oriented culture” (Document 2) through embedding innovation into the goals and strategy. Whilst a shift in culture has not yet taken place, the management are in the process of exploring what changes need to be made in order to influence a new culture by asking critical questions. They are aware that a change in culture is a long-term process that cannot be achieved quickly.

The interview questions did not guide the subjects towards the topic of beliefs; therefore, it was less frequently coded however can be inferred from the interviews. The beliefs of individuals are largely influenced by one’s external environment (Respondent 4). As seen in the previous research and data, “public organisations often lack the organisational capacity to capture good ideas [and] support innovation processes” (Document 1). Such institutional limitations can transfer to the beliefs of the individual, creating a lack of permissive leadership and a fixed cognitive environment that is afraid of risk (Document 1). A strength highlighted in the data shows that the management are extremely supportive of the goals which can reinforce the belief that the organisation can achieve sustainable change (Respondent 7). This can have a ripple effect onto the employees who are described as being talented, committed, driven and ambitious.

The sub-code of values was added to the adapted framework. As a public service agency, the primary organisational value is to provide a well-functioning infrastructure to the public and to take care of the resources for present and coming generations. In addition, the data indicated that the values expand into the field of sustainability as they “take a clear greater responsibility for sustainable community development and to become a sustainable organisation” (Document 3). Furthermore, the commitment to innovation is reflected in the institutional logics and comes through in the data, highlighting it as another value. They see the importance of creating an innovative management system through creating a “challenge-driven knowledge and development process” (Document 1). The final value to highlight here is the relationships within the organisation, understanding that “infrastructure depends not only on technology and artefacts, but also on people, relationships” (Document 1), as well as the need for strong, innovative and creative leaders to drive change.