Reports from Urban Studies

Research Internships 2017

Reports from Urban Studies Research Internships 2017

© Copyright: Författarna, 2018

Editors: Guy Baeten, Fredrik Björk, Anders Edvik & Peter Parker Layout: Josefin Björk

Cover: Anna Wahlgren, Malmö univeristets bildbank ISBN:

(tryck) - 978-91-87997-10-5 (digital) - 978-91-87997-11-2

Content

Introduction 4

A House that Creates Relationships. A Case Study of Sofielund’s Collective House in Malmö, Sweden

by

Anna-Riikka Kojonsaari

5

Business Improvement Districts and Their Role in the Swedish Context

by

Maja Stalevska & Dragan Kusevski

13

The Urban Mycelium: Urban Agriculture Networks and Systems in Malmö, Sweden

by

Kerstin Schreiber

43

Social impact generated by urban farming. A study on the application and purpose of SROI to communicate

the value of urban farming

Earlier publications in the MAPIUS-series

1. Mikael Stigendal (2007) Allt som inte flyter. Fosies potentialer – Malmös problem.

2. Ebba Lisberg Jensen & Pernilla Ouis, red. (2008) Inne och ute i Malmö. Studier av urbana förändringspro-cesser.

3. Per Hillbur, red. (2009) Närnaturens mångfald. Planering och brukande av Arriesjöns strövområde. 4. Johanna Sixtensson (2009) Hemma och främmande i staden. Kvinnor med slöja berättar.

5. Per-Olof Hallin, Alban Jashari, Carina Listerborn & Margareta Popoola (2010) Det är inte stenarna som gör ont. Röster från Herrgården, Rosengård – om konflikter och erskännande.

6. Mikael Stigendal (2010) Cities and social cohesion. Popularizing the results of Social Polis.

7. Mikael Stigendal, red. (2011) Det handlar om något större. Kunskaper om ungdomars möte med sin stad. Följeforskning om New City.

8. Eva Öresjö, Gunnar Blomé och Lars Pettersson (2012) En stadsdel byter skepnad. En utvärdering av förny-elsen på Öster i Gävle.

9. Nicklas Guldåker och Per-Olof Hallin (2013) Stadens bränder del I. Anlagda bränder och Malmös sociala geografi.

10. Helena Bohman, Manne Gerell, Jonas Lundsten och Mona Tykesson (2013) Stadens bränder del 2. Fördjup-ning.

11. Manne Gerell (2013) Bränder, skadegörelse, grannskap och socialt kapital.

12. Mikaela Herbert (2013) Stadens skavsår: Inhägnade flerbostadshus i den polariserade staden.

13. Eva Hedenfelt (2013) Hållbarhetsanalys av städer och stadsutveckling. Ett integrerat perspektiv på staden som ett socioekologiskt komplext system.

14. Irene Andersson (2013) För några kvinnor tycks aldrig ha bott i Malmö. Om synlighet, erkännande och genus i berättelser om Malmö. Publicerad tillsammans med Institutet för studier i Malmös historia.

15. Per-Olof Hallin (2013) Sociala risker: En begrepps- och metoddiskussion.

16. Carina Listerborn, Karin Grundström, Ragnhild Claesson, Tim Delshammar, Magnus Johansson & Peter Parker, red. (2014) Strategier för att hela en delad stad. Samordnad stadsutveckling i Malmö.

17. Helena Bohman, Stig Westerdahl & Eva Öresjö, red. (2014) Perspektiv på fastigheter.

18. Richard Ek, Manne Gerell, Nicklas Guldåker, Per-Olof Hallin, Mikaela Herbert, Tuija Nieminen Kristofers-son, Annika Nilsson & Mona Tykesson (2015) Att laga revor i samhällsväven – om social utsatthet och sociala risker i den postindustriella staden.

19. Helena Bohman & Ola Jingryd (2015) BID Sofielund. Fastighetsägares roll i områdesutveckling.

20. Helena Bohman, Anders Edvik och Mats Fred (2016) Nygammalt: rapport från områdesutveckling i Södra Sofielund/Seved, Malmö stad.

21. Margareta Rämgård, Peter Håkansson & Josefin Björk (2018) Det sociala sammanhanget. Om Finsam Mitt-Skånes arbete mot utanförskap.

Introduction

Students at the Master of Urban Studies at the Department of Urban Studies, Malmö University, have the option to become a Research Intern at a research project at Malmö University or elsewhere. Students become a member of a professional research team and can gain invaluable research experience that will be of help later in their career. At the end of the internship, students present their research results and write a report. This publication contains four such reports written in the beginning of 2018.

Anna-Riika Kojonsaari participated in the Critical Urban Sustainability Hub, or CRUSH. CRUSH runs between 2014 and 2019 and is a FORMAS Strong Research Environment that brings together 14 researchers from Malmö, Uppsala, Lund and Göteborg. It is a research platform with an international outlook on critical perspectives on ur-ban sustainable development, and with a prime focus on Sweden’s acute housing crisis. Its overall focus is the hou-sing crisis (and related urban issues: displacement, eviction, gentrification) seen through the lens of weak groups in order to provide discursive space for those groups in science and media. Rather than defining the current housing crisis as a mere housing shortage that can be built away, it defines the crisis as a crisis of housing inequality and housing polarization. In that way, it seeks to highlight power relations and injustices at work in the housing market.

Maja Stalevska and Dragan Kusevski participated in the research platform shifting conceptualizations of property in Sweden, a multidisciplinary research platform at Malmö University, that explores how different conceptions of property inform urban development. The starting point is that conceptions of property are highly normative, complex and span a field far beyond the strictly legal. Moreover, these conceptualizations have important implica-tions for understanding for instance, the role and limits of urban planning, sale of municipal land, gating and the management and use of public space. Maja Stalevska and Dragan Kusevski have mapped and analysed the growth of BID-like (Business improvement districts) organizations in Sweden which is indicative of a significant shift in understandings of public space and its management.

Kerstin Schreiber and Louise Ekman took part in Malmö Växer, a VINNOVA-financed project on urban cultiva-tion led by the City of Malmö, in partnership with Malmö University. The project aims to find ways the municipa-lity can coordinate urban cultivation in public space. Urban cultivation has been wide-spread in Malmö for many years, but the municipal organisation has not kept up with the rapid increase in interest and lacks ways to manage urban cultivation in all its different forms. Together with local stakeholders the project intends to experiment with different models of governance to ensure long term sustainability for urban cultivation initiatives. The project will also investigate ways to measure and evaluate the values and benefits of urban cultivation from social, ecological and economic perspectives.

A House that Creates Relationships

A Case Study of Sofielund’s Collective House in Malmö, Sweden

Anna-Riikka Kojonsaari

One of the oldest human needs is having someone to wonder where you are

when you don’t come home at night. – Margaret Mead

Abstract

In the winter of 2017, I conducted a study in Sofielund’s Collective House (SoKo) in Malmö, Sweden, with the aim to understand how the everyday is experienced by the residents in a collective house and what kind of meaning is created around belonging. The study was a part of my research internship in Critical Urban Sustainability Hub (CRUSH), a research platform that focuses on sustainable housing. I was interested to consider the social sustaina-bility of collective housing from the individual’s perspective through the concept of belonging and connect it to the analysis of a collective house in the neoliberal era.

During November and December of 2017, I conducted six qualitative semi-structured interviews and ob-servations in the collective house. The qualitative data was supported and compared with data gathered through an online survey¹ distributed for the residents and answered by 21 inhabitants anonymously. The validity and soundness of data were tested through triangulation via different sources: the interviews, survey data, secondary data from local newspaper articles. The data was analysed with theoretical considerations around collective action and commons, derived from Elinor Ostrom (1990, 2007), David Harvey (2012), and Zygmunt Bauman (2000), inspired by a question whether housing could be considered as a common resource.

This internship article is an ethnographic report that aims to offer an account of the everyday practices of sha-ring taking place in the house and the demonstrations of belonging through the dwellers’ perspective. It is also an outcome of my learning process during the internship. Furthermore, the account is my interpretation of the every-day in Sofielund’s Collective House while I have aimed to give room for the interviewee’s voices.

I want to thank Daniel Sestrajcic and other informants: Frida Jorup, Ylva Karlsson, Vera Rastenberger, Dana Lötberg, Julia Lundberg, and all the residents in Sofielund who took their time to answer the survey thus contri¬-buting to the study.

1. Background

Collective housing is an interesting alternative option for individual housing. Some even think it might offer a solution for the urban housing problems we are facing today. Indeed, cohousing offers a valuable alternative form of living that meets the needs and wants of many people in today’s society (Sandstedt and Westin, 2015). However, as Sandstedt and Westin (Ibid.) note, cohousing should not be romanticised, but neither should it be ignored, despite possible preconceived notions. Even though cohouses have been studied extensively especially in Sweden (Vestbro, 2000), collective management of urban resources, including housing, is gaining new interest from the younger generations. That said, it should be noted that the analysis is made by the younger generations. My focus lies on looking at the sustainability of this type of housing from a social perspective and considering how collective house can act as an enabler in enhancing social belonging in the age of neoliberalism. Vestbro (2012) notes, that in Sweden the most common term for the phenomenon is collective housing. Palm Linden (1992:15) has defined the term kollektiv hus as: “a multi-family housing unit with private apartments and communal spaces such as a central kitchen and a dining hall, where residents do not constitute a special category”. The term collective housing was emphasized in the 1970s, when there became new goals involved, such as community and collaboration (Vestbro 2012:1-2). Before that, the concept referred to the collective organisation of services in building complexes that did not have aims about promoting a sense of community or neighbourly collaboration (Ibid). Throughout this article, I mainly use the term collective housing as it is a direct translation from the Swedish term Kollektiv Hus that Sofielund’s Collective House (SoKo) uses.

People live in collective houses for several reasons, such as shared values around sharing and cooperation. Mc-Camant and Durrett (1988), Woodward (1989), and Vestbro (2000) have aimed to characterise the “Collectivists”, concluding that they usually favour ‘post-materialist’ values, such as leisure time activities, time spent with children, as well as caring more for qualities in nature than in consumer items (Vestbro, 2012). Vestbro concludes, that the cohousing inhabitants are still reviewed to belong to the new groups of “post-materialists”, who turn their backs to the consumer society and favour values such as cultural and recreational activities, meaningful social interactions, and time spent with children (Ibid.). Also, Sargisson (2012), who has focused on contemporary cohousing, con-cludes in her research article, that the shared values favour sharing, cooperation, and participation (including the gift of labour to the community). However, to favor value around sharing, does not need to mean turning back on something, as Vestbro (2012) suggests, but, rather, imagining and creating new, more sustainable ways to organize housing while achieving economic and social benefits.

2. Sofielund’s Collective House

This particular collective house, Sofielund’s collective house in Malmö, became move-in ready in December 2014. The house has about one hundred residents and it aims to be for people from any age groups and with different backgrounds (Lokaltidningen, 2015). Behind SoKo is Kollektivhus i Malmö (KiM), an association that was esta-blished in the year of 2009 by people who wished to live collectively in the city centre. The group started to plan a collective house for themselves. Behind the group was also Kollektivhus.nu, a national association for all the existing collective houses and independent associations in Sweden. The SoKo-group planned the house for several years and designed it to fulfil their needs, which will be explained in more detail further on. Engaging in different groups through the process was a way to make all the inhabitant’s voices heard. KiM participated in the planning process of the house together with SoKo. Other actors involved in the project were Malmös Kommunal Bostad (MKB) and Swedish construction company NCC. Furthermore, SoKo rents the house from MKB and takes care of the house management.

The first time I visited the house, I met with Frida Jorup, a resident and an architect involved in the planning process from the beginning of the project. Frida presents the house, its large kitchen and dining room, living room with library, music room, handcraft spaces, children’s playroom, a spacy laundry room with large windows, movie room, and a “second-hand store”. There is also a designated group of people sorting out the books and organizing them. Moreover, in the living room, there are board games free to use and loan. It is not uncommon to see resi-dents working with their laptops in the common areas, as I witnessed during my first visit. Big windows between the spaces imply a sense of trust and openness, contributing to the feeling of transparency. People often greet one another and stop to change a few words. As dweller Jenny Eriksson said in an interview in the magazine Expressen (2016), the house creates meetings and connections with the neighbours.

the bigger apartments are used as commune apartments. The house also has several common spaces. According to Eva Svegborn in Lokaltidningen (2015), the aim is to use the collectively shared spaces for example as a yoga room, workshops, and music rooms. The house is built as open space and has no gates around. In fact, informant Julia Lundberg noted, that if there would be a gate, she would not want to live in SoKo, since for her it would be counterproductive to the idea of a collective house (Interview 6). Furthermore, one of the people involved in the planning process from the very beginning is informant Daniel Sestrajcic, who now lives in the house. He noted that in the beginning there was a discussion whether the house should close the open stairs in the backyard because there were a lot of children running around (Interview 5). According to Daniel, several aspects were considered in the house meetings, others saying it should not be gated while others feeling it was insecure without a gate (Ibid.). By choosing not to build gates nor close the stairs, SoKo decided to remain open.

What is more, the SoKo-group reminded me of Ostrom’s theory of collective action in which a group of prin-cipals can organise themselves voluntarily to retain the residual of their own efforts (Ostrom, 1990) but also the kind of “self-defined group”² that Harvey discusses (Harvey 2012:73). With the conditions such as defined group boundaries, good conflict resolution abilities, and appropriate rules, many groups can manage and sustain common resources (Hess and Ostrom 2007:11). Thus, these notions made me interested of exploring how this kind of group organise themselves and how the process takes place in the everyday. I was also curious to lift up the question of whether housing could be seen as a common resource. Ostrom, as many of the interviewed residents in SoKo, belie-ves in self-governing. In practice, this does not demand an organisation, but a process of organising; an organisation is the result of that process (Ostrom, 1990:39). With this in mind, I will now present my findings and engage in analysis divided in three chapters: sharing, negotiating, and belonging.

3. Sharing

The house has shared material resources; there is no need to own everything privately if the possibility of asking the next-door neighbour is considered as a norm. Through the implementation of the “store”, SoKo encourages circular and shared economy. The “store” is a room that serves for circulating material that is no longer needed; one can leave own redundant things in the room and take something else in return if needed. For example, the collective has a shared vacuum cleaner ergo it is not necessary to privately own one. Other items that the inhabitant’s share is for example screwdrivers, clothes, bikes, suitcases, rain boots, cat food, and so on. Informant Julia mentioned she enjoys the feeling that so much in the house is common (Interview 6). In the light of this, within the SoKo-mem-bers, members who share similar values around housing and want to live collectively, housing, to a certain degree, between the inhabitants, resembles a common resource.

Indeed, sharing has been taken into consideration from the beginning of the planning and design processes. Some of the common rooms are bookable for group meetings or other functions. For example, informant Ylva Karlsson, who is a social rights activist, uses the common spaces for meetings with other activists. One of the rea-sons why she lives in a collective house is the ability to use the house as a tool, for example when arranging meetings (Interview 2). The house is not something that is owned by any one individual, but it is something that the com-munity manages together: “[…]we take care of that [the collective house] for not just this small comcom-munity but for the community in the city and sort of the society, the bigger community.” (Interview 2). Hitherto, the house has shared its resources to protesters during the eviction of Romani people who camped in the district of Sorgenfri, Malmö. People were protesting the eviction and spent days in the occupation without a possibility to shower, so some inhabitants in SoKo arranged a possibility to shower in the house. Because the house has communal showers and a sauna, they let the protestors to use these spaces. In this way, the house shared its resources with the wider community outside the house.

So, how does the house relate to the city around it? It is true that SoKo has structured itself around members, however, they have made efforts to share resources with the outside community by arranging open house events, second-hand markets, and other open events. SoKo plans to continue this openness in the future. In the interview with Ylva, she reflected how the house might not engage in the local district as much as she thought they would but sees it understandable since the house needs to focus on the internal processes, referring to the meetings and negotiations (Interview 2). As the informants reflected, this might be due to the house being young and the fact that the residents are still finding ways to deal with the internal processes and finding the best practices. For ex-ample, Ylva noted, how there are many resources and possibilities which she believes the house is only starting to explore (Interview 2). It will be interesting to see, how the relationship between the collective house like and the city develops in the future.

4. Negotiating

Bauman notes in “Liquid Modernity” (2000), that the most promising kind of unity is achieved daily anew by confrontation, debate, negotiation, and compromise between values, preferences, chosen way of life, and self-iden-tification of many different, but always self-determining members of the polis. One part of the SoKo-association is negotiating over internal processes. The house arranges monthly meetings that at times require several hours from the inhabitants. One of the key questions had been the queue system and how to manage the distribution of free apartments. The association had developed a system for queuing, yet none of the free apartments had been distributed through it which was seen as a problem. In fact, the question remained debated for almost a year, but through time and continuous negotiation, the residents seemed to have found a compromise. Thus, the collective can be seen functioning in the everyday through small actions between the residents, but also in a wider time frame in the weekly dinners and monthly meetings et cetera.

The majority of the interviewees said they sometimes feel stressed about the chores or meetings around the hou-se, however, these notions were continued with thoughts of their value since they also bring them a lot of joy. In-deed, according to the inhabitants, the decision-making process is time-consuming, but at the same time necessary. Informant Vera Rastenberger noted that it may feel a bit unpleasant with the long meetings, but, after all, striving so that as many as possible agree is a good thing (Interview 3). Furthermore, Julia noted that even though not all the topics in the meetings are interesting for her personally they should be discussed since they may be important to others, and sees this as a part of the idea around democracy (Interview 6). The informants saw the value in the meetings and negotiations, some even in the conflicts. For example, Ylva considered that the society might shy away from conflict, rather than seeing it as something positive or necessary (Interview 2). What she means is, that conflict can be carried out in a negative way, but in itself, it is a rather neutral as well as very important thing (Ibid). It is clear that the meetings require time and patience from the individuals, but the inhabitants seem to reflect upon it as something unavoidable and part of the collective. Indeed, when looking at the house with Bauman’s (2000) and Ostrom’s (1990) thoughts in mind, the chosen way of life, the polis where the members negotiate daily, SoKo has managed to create a promising kind of unity to retain the residual of their own efforts - a house where the in-habitants engage in the house management and see the rules and negotiations as valuable part of it.

5. Belonging

When asked about the favourite qualities of the house, the neighbours or the community feeling was replied without exception. Some of the residents live on their own, some share apartments with one or more persons, and there are also collectives, or what Vestbro (2012) would define as communes, within the collective. Living in a collective house and having other people around in the everyday might help to avoid the feeling of alienation, which individualism might produce. Hylland-Eriksen (1995:58) notes, that in European societies, the self is often regarded as an inde-pendent agent, undivided (as in the word ‘in-dividual’), integrated and sovereign, in contrast to many non-Western countries, where the self may be seen more as the sum of the individual’s social relationships. Our housing is organised around individualism. In SoKo, on the other hand, 76% of the residents in SoKo know most of their neighbours (survey data). To form relationships with one’s neighbours seems to be one of the most positively regarded aspects of living in a collective house. Social relationships, a social network, that is close by creates feelings of security and alienates feelings of loneliness. Informant Daniel talked about a poster they have in the house, that says “akta dig för ensamheten”, watch out for loneliness, which Daniel says for him represents the reason to have a collective house (In-terview 5). To avoid loneliness can be taken into consideration when creating new public spaces and housing in cities. One of the ways that make the residents feel belonging to the community is the habit of sharing a meal and eating together. The house arranges dinner collectively three times a week. They manage the preparing and plan-ning through an app which allows the inhabitants to book their meals and preferences in advance. In fact, eating together was considered as one of the most important factors for the community feeling and was brought up by almost every informant. The common dinners were the most answered feature in addition to neighbours when asked about the best qualities of the house. It serves as a way to get to know the neighbours better and establish relationships. The habit of eating together creates the sense of community and serves as an enabler to get to know the neighbours and strengthen the existing relationships. Informant Daniel was very inspired by the Landless Wor-kers Movement in Brazil (MST), Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra, where one of the groups central idea is to eat together (Interview 5). In fact, he mentions that without the communal eating, SoKo would not be a good collective house (Interview 5). Eating and socialising are basic human needs, both performed in the everyday; in a

collective house these aspects form a basis for the community feeling, thus communal kitchen is one of the basic building blocks of a good collective house.

Furthermore, it is not only eating together that creates the feeling of belonging but also the community work performed together with other residents, like preparing the food or maintaining the house. These gifts of labour lead to an environment of reciprocity, where people help each other and thus create an interacting network. These acts further strengthen the relationships and connections among the inhabitants. Furthermore, Dana Lötberg re-flected the housework:

Some feeling of meaningfulness, that I feel that this house is important. Of course, you can feel alone in this house, of course, but also it is some kind of security net, that you have so many people around you that also know some parts of your life. They can see that you are home, they can see that you are eating, so it is a safety net. I feel that it is important, I like being a part of that (Interview 4).

The network the residents create through the everyday actions, through different gifts, and the sharing economy is the social layer of the collective house, totally depending on the residents. However, in the case of SoKo the constructions of the house, the material side of it, also nourishes this kind of interaction.

In addition, I noticed how everyone in SoKo greeted one another when passing by. During almost all of the interviews, other residents would walk by and change a few words. Certainly, the sense of community is created through the activities the inhabitants perform, but also small everyday actions such as paying attention to one another. Informant Ylva noted, that building the community every day includes doing the relational community work, such as saying hi and helping out someone (Interview 2). Indeed, the community is built through the rela-tionships that are taking place and strengthened in the everyday actions. One respondent reflected that the com-munity feels like having a big family:

It is easy to talk to everyone; it is like having a big family, sharing common spaces in the evening, eating together... Some of the people I have got to know very well, and it is easy to get new friends in a community like this. Even the ones I do not talk to that often are like family in a way since we share so much in the house (Anonym survey respondent).

Meanwhile, Julia described that the idea of living collectively for her is very much expanding the idea what home is (Interview 6). Expanding the idea of home and relationships instead of creating a traditional individual home does not need to be seen as turning your back on something, but instead, expanding the ideas traditionally attached to an individual home.

What is worth noting is, that there are more women than men living in SoKo. This gender imbalance was cate-gorised as a negative aspect by some of the survey informants as well as the low amount of older men especially. It seems that more women want to live collectively than men. I asked Dana why she thinks there is gender imbalance, and she answered it might be due to how people are raised in the society (Interview 4). Whereas women are raised for being caring and social, men have to be able to take care of themselves, she reflected (Ibid). In fact, Vestbro has concluded, that the patriarchal society has been the main obstacle to the implementation of cohousing (Vestbro, 2012). It might be that females more easily gravitate towards the social layer of the collective houses, due to the existing gender roles in the society.

The feelings of belonging are experienced differently at the individual level. The differences in age distribution might have an effect on how the residents experience belonging. The collective house has inhabitants from different ages. One of the informants, 74-year-old Vera, has experience in living collectively also in a 55+ collective house for the elderly, but she prefers more age variety in the people around her in the everyday life. Compared to the 55+ houses, Vera considered Sofielund better for her because there are children and young people around who bring her joy but also other like-minded 70-year-olds (Interview 3). A collective house could serve as an alternative to elderly care, where a mutual benefit is achieved through the social layer. Likewise, retired Monica Ståle names the same factor in an interview in ETC-magazine (2017): the wish to rather be surrounded by people of different ages. Mo-reover, Hylland-Eriksen (1995:142-3) notes, that ageing is an inevitable biological process but, like gender, it is a universal principle for social differentiation, yet both of them are socially constructed to some extent. To which de-gree we allow these differentiations affect the way we organize our social lives is a question that could be asked when building and planning housing. The social layer in the collective houses makes a reciprocal relationship between the residents from different walks of life possible while creating a security net for the elderly residents as a byproduct.

In conclusion, the community is just as much a living process dependent on its own constant reinventing and reassembling, which require collective and continuous effort. It is performative as I have demonstrated, and it is a process that requires developing relationships based on mutual understanding. Furthermore, community is not an institution nor an organisation but a way to make links between people (Zibechi 2010:14) and the links are taking place in the everyday in the case of SoKo. Ergo, community is constantly re-invented and re-created (Ibid:19). The collective housing can be viewed as a stage where these relationships are cultivated anew and the community that is achieved through this process functions as a relational ground for collaborative lifestyle thus creating a motion, like a circle that reinforces itself. When examining these relations and interrelations in SoKo, we can see the house and its inhabitants operate in a liminal state, a state of becoming or as a constant state of flux that is visible in the negotiations, house meetings, and sharing economy, but also in the everyday activities. Julia brilliantly described it:

To me, it is very interesting to feel that you are a part of a bigger motion like there are different groups doing stuff and they have just been fixing the cinema room, and it is so beautiful. And they are like, okay, could someone just like paint the table? So, then me and someone else were like okay, we are doing that. So, we have been like 15 people altogether or se-parately creating this space. Those are the times when you are not actually doing something for your tiny, tiny home, but you are expanding the idea, even though I am in that room like every third week I still feel like oh wow this is like my living room basically. Like creating this area with, it is so amazing how you have earlier thought about your tiny tiny home, and here space is big, I think that almost like physically does something with one’s brain (Interview 6).

Through taking care of the home while working together, several human needs are fulfilled simultaneously.

6. Conclusion

In this article, I have aimed to give an account of the everyday practices of sharing and understand how the inha-bitants in Sofielund’s Collective House articulate and demonstrate belonging in relation to their housing. I carried out interviews and observations in SoKo during November and December of 2017, together with an online survey, to gather data for an analysis. I wanted to consider the resident’s experiences and analyse how living in a cohouse is experienced by them. Therefore, I used ethnographic inquiry which allows this kind of perspective.

In the case of Sofuelund’s Collective House, what seemed to be important factors for the community feeling and the feelings of belonging were traditions such as eating together and small everyday performances like greeting one another. The house was designed from the beginning with the idea of creating the feeling of community and encouraging sharing. These ideas were materialised in the common spaces around the house such as the communal kitchen, library, the “store”, and sauna, big windows to enhance transparency, and the decision not to build any ga-tes. Moreover, the residents answered the most positive aspect of the house was the weekly dinners arranged collec-tively. Also, negotiating and meetings were seen as an important, though time-consuming, part of the community.

Furthermore, it is important to deeply understand the human needs, need for intimacy and belonging, when planning for sustainable future housing. Taking into consideration different needs and different wishes regarding housing, there could be a wider variety of different types of housing in the cities to serve different kinds of social needs. Thus, this study has aimed to contribute to the understanding of how collective housing might act as an enabler in fulfilling certain human needs, such as belonging, by looking at the dweller’s points of view. Sofielund’s Collective House serves as an example, that for a certain group to organise and realise housing on their own terms in a city is possible.

Endnotes

1. A survey was conducted through Sunet Survey software. The link was distributed by email to the residents in Sofielund. It was not controlled whether the respondents actually lived in the house since the link was distributed through a closed email list. Also, the survey was clearly addressed for the people living in Sofielund’s Collective House. The known variable in the surveys is, that you can never truly know who answers them. One method to increase the reliability was that the survey link was open for a relatively short period of ten days. In this time, the survey was answered by 25 respondents. In contrast to the interviews, in surveys, the interviewer effect is eliminated, so the combination of these methods allowed me to compare the data.

2.Harvey discusses the practices of commoning. SoKo does not meet the definition of commoning because their environment is not “non-commodified-off-limits to the logic of market exchange and market valuations” (Harvey 2012:73) but still has a value in itself. See Harvey’s whole quote: “The common is not to be construed, therefore, as a particular kind of thing, asset or even social process, but as an unstable and malleable social relation between a particular self-defined social group and those aspects of its actually existing or yet-to-be-created social and/or physical environment deemed crucial to its life and livelihood. There is, in effect, a social practice of commoning. This practice produces or establishes a social relation with a common whose uses are either exclusive to a social group or partially or fully open to all and sundry. At the heart of the practice of commoning lies the principle that the relation between the social group and that aspect of the environment being treated as a common shall be both collecti-ve and non-commodified-off-limits to the logic of market exchange and market valuations. This last point is crucial because it helps distinguish between public goods construed as productive state expenditures and a common which is established or used in a completely different way and for a completely different purpose, even when it ends up indirectly enhancing the wealth and income of the social group that claims it. A community garden can thus be viewed as a good thing in itself, no matter what food may be produced there. This does not prevent some of the food being sold.” (Ibid).

References

Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

Hess, C. & Ostrom, E. 2007. (eds.). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hylland-Eriksen, T. 1995. Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology. 3rd ed. Pluto Press. Kollektivhus i Malmö, KiM. Hur KiM skapade SoKo. Last accessed: 2017-12-06 at

https://kollektivhus.wordpress.com/so-fielunds-kollektivhus/

McCamant, K. & Durrett, C. 1988. Cohousing - A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves. Berkeley, California: Habitat Press/Ten Speed Press.

Nordh, J. 2015. Lokaltidningen, Malmö Limham. 2015-01-22. Last accessed: 2017-12-06 at http://malmo.lokaltidning- en.se/f%C3%B6r-de-goda-grannarna-finns-det-inget-tvaang-att-g%C3%B6ra-allt-tillsammans-/20150122/artik-ler/150129963/

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palm Linden, K. 1992. Kollektivhuset och mellanzonen. Om rumslig struktur och socialt liv (Collective housing and intermediary space. About spatial structure and social life). PhD thesis, Lund University, Building Functions Analysis, School of Archi-tecture.

Sandstedt, E. & Westin, S. 2015. Beyond Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Cohousing Life in Contemporary Sweden. Housing, Theory & Society. 2015, Vol. 32 Issue 2, pp: 131-150.

Sargisson, L. 2012. Second-Wave Cohousing - A Modern Utopia? Utopian Studies. Vol. 23 Issue 1. 2012, pp: 28-56.

Selåker Hangasmaa, K. 2016. Därför vill allt fler bo i kollektivhus. Expressen. 2016-03-20. Last accessed: 2017-11-06 at htt-ps://www.expressen.se/kvallsposten/hem-och-bostad/darfor-vill-allt-fler-bo-i-kollektivhus/

Vestbro, D.U. 2000. From Collective Housing to Cohousing – A Summary of Research. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Vol 17:2.

Vestbro, D.U. 2012. Saving by Sharing – Collective Housing for Sustainable Lifestyles in the Swedish Context. 3rd Interna-tional Conference on Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity, Venice, 19 – 23 September 2012.

Wickberg, J. 2017. Flyttade från ensamhet till ett åldersblandat kollektiv. ETC. 2017-04-04. Last accessed: 2018-01-08 at http://malmo.etc.se/inrikes/flyttade-fran-ensamhet-till-ett-aldersblandat-kollektiv

Woodward, A. 1989. Communal Housing in Sweden. A Remedy for the Stress of Everyday Life? Franck, K.A. & Ahrentzen, S. (eds): New Households, New Housing. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 71-94.

Appendix

List of the interviews:

Interview 1. Frida Jorup, at Sofielund’s Collective House 10.11.2017. Interview. 2. Ylva Karlsson, at Sofielund’s Collective House 13.11.2017. Interview. 3. Vera Rastenberger, at Sofielund’s Collective House 13.11.2017. Interview 4. Dana Lötberg, at Sofielund’s Collective House 20.11.2017. Interview 5. Daniel Sestrajcic, at Sofielund’s Collective House 11.12.2017. Interview 6. Julia Lundberg, at Sofielund’s Collective House 11.12.2017.

Business Improvement Districts and Their Role

in the Swedish Context

Maja Stalevska & Dragan Kusevski

Abstract

The overarching aim of this research is to capture the general picture concerning the conception and delimitation of BIDs (Business Improvement Districts) in Sweden, and in particular, to understand the present-day perspectives both of municipalities and property owners with respect to their formation. Given the lack of previous research providing a general overview of the Swedish context, an inventory on all operating BID-like partnerships in Sweden is presented, with the aim to capture the general specificities of the Swedish BID-model. Particular focus is paid on partnerships operating in residential areas – referred to here as Neighbourhood Improvement Districts (NIDs). The paper provides a rough comparison of seven residential areas in Gothenburg, Stockholm and Malmö, as delimited by the geographical extents of the seven identified NID partnerships. A spatial analysis of the cases - their socio-eco-nomic context and spatial delimitation - goes to show that a geographic consideration of the spaces, i.e. where they appear, is pivotal to understanding their role and function, or why they appear: namely, to strengthen legitimacy of urban governance in spaces of attractive property development. Despite the local specificities and differences between the cases, based on the empirical data, we argue that the formation of NIDs is mainly preconditioned by three particular factors: the vulnerable socio-economic environment, the high economic potential of the areas, and a specific property-ownership structure, usually dominated by one or few bigger (often public) property actors. This particular geographic pattern of emergence is specific to Sweden and has not been recognized in other contexts so far. However, the main concerns in regard to enabling the creation of BID partnerships in general remain valid for the Swedish context as well, as they, much as their UK and US counterparts, remain largely unburdened by accountability, democratic dialogue or social justice considerations.

Keywords: Business/Neighbourhood Improvement Districts – Sweden - Property owners - Municipal housing companies – Regeneration tactics - Legitimacy

Introduction

In the wake of the 1990’s economic crisis, rising unemployment and increased immigration influx in Sweden, a deepening urban segregation pattern and uneven urban development within major cities have put the political fo-cus on lifting the most socio-economically challenged residential areas. Within this context, emerges a new category of public-private partnerships, or so-called business improvement districts (BIDs), formed by property owners with the support or in collaboration with politicians and local authorities, with a primary objective to improve the att-ractiveness and increase the property values in vulnerable residential areas (Holmberg, 2009; 2016; Olsson, 2017). This study is generally concerned with the conception and delimitation of the Business Improvement Districts in Sweden, and particularly, with the present-day perspectives of municipalities and property owners with respect to their formation. Accordingly, we suggest that the BID co-operation in Sweden is a three-sided process, with three particularly important perspectives that need to be considered in view of their analysis: the municipality-, the pro-perty owners-, and the residents’ perspective. Since the forming of BIDs is mainly preconditioned by the indepen-dent interests that the first two parties maintain in specific relegated resiindepen-dential area, in addition to presenting the particularities of their emergence and activities, we will also provide an account of the contestation over the lack of democratic dialogue arising from placing land and property ownership in the centre of the BID as a precondition, or condicio sine qua non, for formal participation.

In the seemingly binary public/private constellation of BIDs, the interest of public housing companies has been particularly perplexing, mainly in relation to their dual role of acting as business-like entities on one hand, and public actors bound by social responsibility on the other. Following this, the study focuses particularly on capturing the perspectives of the public actors involved in the BID process, not least arising from the fact that all BIDs in Sweden have been, without any exceptions, formed on the initiative of public housing companies and/or local public authorities. Although the initiatives do sometimes intertwine and can come from different parties at the same time, we suggest that public actors are a particularly important factor for understanding this case as they do, without question, act as drivers of the BID process in Sweden from day one.

In trying to understand why public actors would consider engaging in the promotion of BIDs, we turn to the current wave of urban regeneration of socio-economically challenged and stigmatized areas in Sweden, and the potential role BIDs might have in this context. Thus, while most previous research on BIDs has considered the organizational form as such, we maintain that a spatial analysis of the Swedish cases i.e. where the BIDs are located and how they are delimited - is pivotal to understanding their role and function: namely, to strengthen legitimacy of urban governance in spaces of attractive property development. In other words, we suggest that by initiating BIDs - or local partnerships for urban development, public housing companies and local governments try to create a solid ground for prospective change in stigmatized areas where the interest in investing is low and/or there is no middle-class housing spillover demand. In doing so, both parties actively work to attract support and larger in-vestments toward the area in order to effect bigger structural changes along the way. Furthermore, both public and private property owners (management) seek to gain legitimacy through the process and establish themselves as cre-dible agents of change. We relate to Van Gent’s (2010) theory of adopting social transformation strategies according to the local housing context, and particularly to Parker and Madureira’s (2016) development of that theory which includes notions of legitimacy to better understand the actions of management within the specific housing context.

BIDs play multiple roles in the reaching of the above-mentioned overarching goals. First and foremost, they serve as means of getting local property owners to commit to developing the area - both their own property and the public space around it - with the primary objective of raising the property values. Additionally, the formation of BIDs is always preceded by some form of initial research and problem description of the entire urban area in question.

The reason for persuading private property owners to join is to commit them to invest in raising the standard of their housing stock, and potentially engage in upgrades and investments in the public space, which is in effect directly related to the aim of BIDs to institute social change in deprived residential areas. Upgrading a residential area by gradually raising the living standards through physical upkeep and upgrade of public amenities is a strategy for social-transformation often adopted in neighbourhood regeneration, mainly when the housing context (Van Gent, 2010, Parker and Madureira, 2016) does not allow for, or constraints, the use of a more radical approach such as for example demolition, reconstruction or tenure-restructuring, as is the case with vulnerable residential areas in Sweden.

By the same token, BIDs also provide an effective way to focus policy attention and public funds to the areas in question, as they enjoy a privileged access to city officials and are treated favourably by city and district admi-nistrations.

In line with the general aim of the research and given the lack of previous studies providing a general overview of the Swedish context, an inventory on all operating BID-like partnerships in Sweden is presented in this paper, with the aim to capture the general specificities of the Swedish BID-model. Particular focus is paid on partnerships operating in residential areas – referred to henceforth as Neighbourhood Improvement Districts (NIDs). The paper provides a rough comparison of seven residential areas in Gothenburg, Stockholm and Malmö, as delimited by the geographical extents of the seven identified NIDs. The remainder of the paper is consequently organized in two parts. The first part begins with a general overview of the BID concept, its origins and dissemination in different contexts, followed by an overview of the main concerns related to its institutional set up and main operations. This is followed by an overview of the two types of BID-like partnerships found in Sweden, and an introduction of the separate case studies which represent the focus of the research.

The second part provides a discussion of our main findings, organized around three central themes, each at-tempting to capture a particular aspect of the NIDs specific emergent geography. Despite the local specificities and differences between the cases, based on the empirical data, we argue that the formation of NIDs is mainly pre-conditioned by three particular factors: the vulnerable socio-economic environment, the high economic potential of the areas, and a specific property-ownership structure, usually dominated by one or few bigger (often public) property actors.

In the first chapter of the second part we explore concepts of spatialized crime-prevention theories particularly employed in the country’s national crime policies and explore their use and appropriation by NID partnerships in order to better understand their operations in socio-economically vulnerable areas with high crime rates and high levels of insecurity.

The second chapter explores NIDs emergence in what we argue are vulnerable areas with a high economic potential. We will present the context of urban regeneration practices, public-private partnerships, urban policies and area-based initiatives in Sweden, as we build on the notions of state-led gentrification and the ‘social-mix’ prin-ciple. At the end, we’ll discuss the implications that these processes may have on urban governance, social justice, property and democracy. We’ll also give a review of the contestation and voices of resistance that have appeared as a reaction to the NIDs urban regeneration tactics.

The third chapter will deal with the specific ownership structure of the housing stock in the NIDs areas. We believe that it is of crucial importance to point to the specificities of the property-ownership structure and its con-nection with the formation of NIDs. We are going to discuss the Swedish housing context and the role that muni-cipal housing companies have in relation to the occurrences in the housing market and the formation of the NIDs in particular. The notion of legitimacy by Parker and Madureira (2016) will be used to explain their movements in these areas, as we believe that it has to do with presenting themselves as credible agents for future bigger-scale regeneration.

The final chapter summarizes the conclusions from the research and reflects on the study’s limitations and pro-vides recommendations for future research.

PART I

1. Introduction of the BID concept and its transfer to Sweden

The definition of BIDs shifts considerably along different countries and regions since the legislation and the parti-cular forms of organization are shaped according to local conditions. Each country, region, even individual BIDs, have their specific definitions of what constitutes a BID, which renders more difficult the attempt to coin a general definition that will cut across discrete regional models. Moreover, the geographical and legal peculiarities have also implied a varied nomenclature: BIDs in the USA, BIAs (Business Improvement Areas) in Canada, UID (Urban Improvement Districts) and NID/HID (Neighbourhood / Housing Improvement District) in Germany, and so on. However, this traveling concept has some distinguishable features that make it recognizable despite its local va-riations. In general, a Business Improvement District (BID) is the most often used term for organized collaboration within a geographically defined area as a means to increase its attractiveness and promote economic activity: “BIDs provide street-level services and small-scale improvements to streets, parks, and other common areas beyond what local government is willing or able to provide” (Foster, 2011: 105). Their scope of operations and activities varies across regions, depending on the legal framework and the nature or conditions of the designated areas.

The origin of the BID concept can be traced back to North America, from where it has spread to other countries including Sweden. The main reason for its emergence is considered to be the general trend of retail decentralization

that took place back in the 1970-80s and saw town centres, both all over Western Europe and North America, losing pedestrian flow and commercial activity to suburban, businesses like malls and shopping centres (Morçöl, et.al., 2008). This has prompted many local businesses and property owners, located along Main Streets and com-mercial strips in Canada and the USA, to form self-taxing co-operative schemes in an attempt to revitalize run-down city centres and increase business revenues. Responses in Europe have been somewhat different, with the UK and Sweden opting for Town Centre Management (TCM) schemes instead which, unlike their counterparts in North America, are based on a voluntary membership and funding system. Compared to Sweden however, the trajectory of UK’s TCMs has taken an earlier turn toward the introduction of a BID legislation in 2004, as a way to overcome the limitations of TCMs for long term funding and install a more sustainable funding mechanism in lieu of decreasing public financial support (Hogg et al., 2007). With respect to the increased interest for institutio-nalizing BIDs in Sweden, the Swedish TCMs are also exploring the possibility of re-aligning their activities in that direction.

According to Lloyd and Peel (2008), TCM and BIDs differentiate in three particular ways. They argue that “BIDs represent a step-change in urban economic policy and urban revitalization practice because they institutio-nalize the more informal and localized partnership arrangements put in place through TCMs” (Lloyd and Peel, 2008: 15). Second, they point out that BIDs are a mechanism for addressing a complex of environmental, eco-nomic, social, and resource issues associated with urban sustainability, and third, that BIDs represent a new form of contractualism of state-market-civil relations because they are subject to a formal ballot, legitimated through specific legislative and financial provisions (Morçöl, et.al., 2008). Thus, the transformation of TCMs and the call for institutionalization of BIDs in Sweden are a manifestation of the structural transformations that took place in the public sector in the 1990s, and the shift from traditional welfare policies to a more neoliberal urban governance approach. The emergence of the BID concept is historically seen as part of a wider trend of decentralizing policy efforts, seeking to increase the number of actors actively involved in the process of urban governance. In fact, many scholars regard the creation of BIDs to be emblematic of the new forms of governance and the shift toward urban entrepreneurialism, as well as a part of a general trend of neoliberalizing urban policy (Ward, 2007; Lloyd and Peel, 2008).

However, the emergence of the BID model in Sweden is to some extent also the result of policy transfer (Hoyt, 2008; Cook and Ward, 2012; Peyroux et al., 2012). According to Hoyt, BIDs are a rather new urban revitaliza-tion policy, which in the context of a diminishing public-sector influence over urban development, urban policy entrepreneurs are spreading both inside and outside countries as a new coping mechanism for urban decay (Hoyt, 2008). According to Ward and Cook (2012), the two-day conference on BIDs that took place in Sweden in 2009 is a part of that important arena through which the transfer and mobilizing of such urban policies occur. According to Hoyt’s definition on policy mobility, Sweden is right now in the emergence stage which is the importing stage before the introduction of the enabling legislature. Conferences on BIDs with expert-speakers from other countries like the one in Stockholm, as well as policy tourism entailing trips to famous BID examples from the US such as Bryant Park, are all a part of this importing process which entails analysis of so-called best practice examples, pro-motion and lobbying for the enabling legal framework.

Conversely, many scholars are calling for caution in relation to quick or uncritical adoption of policies from contexts that are drastically different from the host, as chances are they could be unsuccessful or worse, further exacerbate the condition of the targeted area. Morçöl et al. (2008) also point to the potential risks and difficulty of transferring policy in different historic or social contexts and argue that there must be some compatibility. They point to the case of the TCM in the UK which served as a valuable conceptual predecessor according to which the BID model could be locally fitted. The long tradition of TCM in Sweden has also been informing the process of advocating for BID enablement and might serve as a valuable resource of local experiences in the tradition of collective action.

Main concerns relating to the operations of BIDs

Before moving on to examples from the Swedish context, we’ll give a short account of the critical voices, as well as advocates for BIDs, and their general thoughts on the shortcomings and advantages of these organizations.

Several authors have taken a critical stance towards BIDs, questioning their purpose and pointing out the pos-sible dangers for the urban social environment. Foster (2011) recognizes three main concerns in regard to enabling the creation of BIDs: the risks of scaling up, distributional issues, and the threat of ossification.

The scale is important since it determines the level of complexness in terms of functionality and the heteroge-neity of the user groups. Foster also argues that the “size of the geographic commons managed by certain groups

and the type and range of functions required or delegated to the group make it difficult for local authorities to effectively monitor these groups” (Foster, 2011: 122). Although BIDs are subject to local government monitoring, she argues that “in practice, it is not at all clear how much attention city officials devote to monitoring these groups” (ibid: 124).

The distribution issues refer to the risk of relying on private actors to manage local goods and services, “without creating or aggravating inequalities in their distribution” (Ibid: 124). Foster argues that more prominent areas will be able to “raise and dedicate private funds, while poorer neighbourhoods will be left underfunded” (ibid: 125). Moreover, “the more that sub local communities are able to manage their own commons, provide for their own public goods, and pay for them directly, the less likely they are to be supportive of citywide services (and taxes) that provide those goods and services to other communities “(ibid: 125), which happen to be particularly vulnerable social groups.

The third issue relates to their durability, that is the fact that despite their limited term, depending on the local government to continue their functioning, BIDs “rarely dissolve” (Ibid: 130). Here, Foster points out the dangers of ossification and emergence of “commons cartels”. She argues, “given what we know about the principles of long-enduring institutions, they work to provide one set of commons users a privileged place at the table... they punish those who challenge the values of incumbent users” (Ibid: 132).

Likewise, Cook (2008: 31) finds the transfer and construction of the BID policies questionable at best. However, what he finds particularly problematic is the “lack of involvement by employees, residents and the wider public”. He continues “from New York City to Bristol, they continue to be unable to vote in local BID elections and are largely absent from local partnership boards […] instead, the direct needs and desires of employers, businesses and, to a lesser extent, consumers prevailed” (ibid: 31).

Ward (2007) recognizes the emergence of the BIDs as a part of the arsenal of neoliberal urbanization. He points out to three signs suggesting this: first that “BIDs are presented as solutions to the failures of the past policies and practices of the state”. Second, “BIDs constitute the dividing up of the city into discrete, governable spaces…that encourage inter-urban competition, as one BID competes with another to capture value, and a share in the spatial division of consumption” (Ward, 2007: 667). This ‘localism’ often can lead to exclusionary practices (Amin, 2004) and creation of insiders and outsiders. Ward comments: “This is all well and good if you look and act appropriately. However, if they feel your presence in the area threatens the veneer of civility that they are active in producing they may have a quiet word, perhaps suggesting you leave the vicinity” (Ward, 2007: 657). Finally, “BIDs are presented as a flexible way of governing”, capable of implementation of programs “more rapidly and cheaply”, avoiding slow bureaucracy, with ‘market-like’ dynamic. He concludes that, as other neoliberal urbanization tools, BIDs “constitu-te the redrawing of sta“constitu-te-market relations not the diminution of sta“constitu-te capacities”. (Ibid: 668)

Despite the critical writings and calls for caution around BIDs, their advocates refer to them as “one of the most important developments in local governance in the last two decades” (MacDonald,1996, np). “We live in an incre-asingly competitive world, where people and capital are ever more mobile. Towns, cities, regions and countries that provide safe and attractive places to live and work will be the winners,” stated UK Prime Minister Tony Blair while announcing the UK legislation for Business Improvement Districts (in Ward, 2007). Some state the positive effect that BIDs can also have to neighbouring areas, counting on the ‘trickle-down’ effect and emphasizing the ‘win-win’ situation. “Benefits produced by BIDs are available to all city residents, not just BID members. We are all free riders on BIDs expenditure”, argues MacDonald (in Cook 2008: 32).

A rich insight of the view of BIDs, can be extracted from the paper by Paul Levy, executive director of a BID in central Philadelphia. He argues that “BIDs seek to make our cities liveable and competitive again. Cleaning, safety, marketing, and parking programs are only a means to this end. This becomes clear when examining the origins of BIDs” (Levy, 2001: 125). He claims that the reason for the formation of BIDs usually lays in “fear or opportunity”. He also argues that BIDs mean change in governance, however warning that “it would be wise not to overstate this idea of governance” (ibid: 130). He seems to confirm the position of many critics who place the BIDs in the shift towards entrepreneurial ways, with statements like “[a] plurality (of the BID managers) defined their primary role not as public servant or supervisor but rather as entrepreneur” (ibid: 127); “the skill they considered most essential to success had little to do with either delivering services or managing staff? Rather, it was the ability to speak effecti-vely to audiences. Often, you do not have to spend money or deliver programs. You simply need to be empowered to take charge and persuasive enough to build consensus” (ibid: 127).

2. Data and Methods

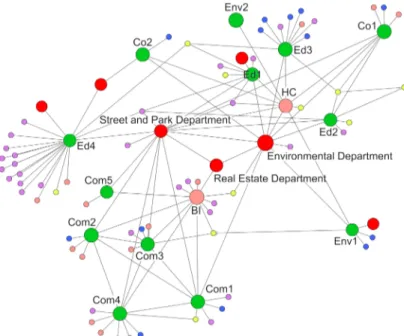

This research has begun as an investigative work with the aim to identify the existing forms of BID-like partnerships in Sweden and hopefully provide some insight into the perspectives of municipalities and property owners with respect to their formation. Although there are certainly many local particularities which could potentially provide a more in-depth understanding of the specific context of each case, we have nonetheless, partly because of the lack of a previous research which provides a more general overview, decided to keep the focus on all seven cases with the aim to capture their general specificities. Accordingly, the paper provides a rough comparison of the seven residen-tial areas in Gothenburg, Stockholm and Malmö, as delimited by the geographical extents of the seven identified NID partnerships. The general data for each area such as population structure, employment levels, education levels and so on, have been obtained from the official statistics of the respective municipalities, government and muni-cipal documents, policy documents, and partly from NIDs’ reports, surveys and interviews with NID managers.

Empirical material regarding the general information for the NIDs such as their geographical boundaries, the organizational forms, the details around the formation process, the membership lists and so on, have mainly been obtained from interviews with NID members and managers, NIDs’ annual reports, web-pages, safety surveys, as well as previous research concerning some of the cases. We have conducted a total of 10 semi-structured interviews with an average length of 50 min per interview. Interviews were made with some of the NIDs managers, board members, representatives of the MHCs, politicians and so on, obtained through a so-called ‘snowball sampling’.

Concerning the geographical data regarding property boundaries and property ownership structure in each area, we have used NIDs official maps of the property ownership and membership structure, obtained from their web-pages. For four of the NIDs (Rågsved, Centrala Hisingen, Gamlestaden and Malmö) which haven’t produced such layouts, we tried to do a rough mapping ourselves by using GIS data from Lantmäteriet’s online geodata da-tabase, combined with property ownership data from public and private real estate companies’ annual reports and web-pages. We haven’t been able to do a complete mapping since some data is not public. Nonetheless, we have been able to get the general picture of the ownership structure for these areas as well. All of the maps, both produ-ced by the authors and obtained from the NIDs, are presented as appendixes to the text.

Additionally, we used data from official documents such as regional, comprehensive and detailed urban plans, plan programs, visions, protocols, printed materials from the NIDs, as well as media reports.

3. BID-like partnerships in the Swedish context

Town Centre Management partnerships (TCMs)

Against the backdrop of retail decentralization in the 1980s Sweden, along with the UK, saw a slightly different version of BID-like collaborations emerging in its emptying town centres. According to Forsberg et al. (1999), the TCM is one of two distinct local policy responses to the 1980s wave of retail decentralization in Sweden - the al-ternative response being a form of continued support for suburban and out-of-town retail centres aimed to keep or increase consumer demand (Forsberg, 1994, 1995). The TCMs (or Stadskärneforening in Swedish), are a form of public-private partnerships still operating in town-centres with the aim to revitalize them as a vital part of the city’s commercial core. They were formed mainly by municipalities, local retailers and businesses, which communicate either through projects or a limited liability company (Edlund and Westin, 2009). However, the National TCM association (Svenska Stadskärnor), includes in its membership both individual municipalities as well as interested businesses which are not necessarily involved in any form of a TCM partnership but rather see a possibility to ex-tend their business networks. The idea is, according to the president of the association, to offer help and education to concerned politicians and municipalities who “see their cities dying and don’t really know how to work with this” (personal communication, October 3, 2017). Additionally, the association collaborates with the National Housing Office (Boverket), the association of Private Property Owners (Fastightesägarna), the National Transport Office (Trafikverket), Visita (the association of the Swedish Hospitality Industry), the Swedish Trade Federation (Svensk Handel), and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting).

The focus of the TCMs is, as already mentioned, increasing the attractiveness of town centres and commercial strips, which entails mainly street-level activities such as cleaning and maintenance of the space around the retailers’ property. Their activities also often extend into organization of promotional events and festivals, as well as occasion-al capitoccasion-al improvements and redevelopment projects, mainly in collaboration with other externoccasion-al actors. In lack of a legal framework for self-taxing, TCMs are funded only by annual membership fees which means that compared to other institutionalized forms of BID-like partnerships, they have a rather small budget at their disposal. Thus, activities such as project-based investments entail additional funding outside their regular budgets, covered either