You shall not pass

A study about Barriers and subsequent Consequences of Sustainable

Business Models in the Swedish Clothing & Textile Industry

PAPER WITHIN Business Administration

AUTHORS: Carl Munck af Rosenschöld, Joel Lindholm, TUTOR: Naveed Akhter

i

Acknowledgments

We want to give many thanks to everyone that has helped us through the journey of writing this thesis. Especially, our tutor Naveed Akhter who helped us several times getting on the right track when we needed it the most. Additionally, we want to give a big thank you to Annika Hall who, despite not being our dedicated tutor, helped us tremendously.

A warm thank you should also be given to every participant of this study. Without your knowledge and expertise, this thesis would never have been possible to conduct. Last but not least, a special thanks to our supportive friends and families for the immense support.

Thank you!

_______________ _______________

Joel Lindholm Carl Munck af Rosenschöld Jönköping 2021 - 05 - 23

ii

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: A study about Barriers and subsequent Consequences of Sustainable Business Models in the Swedish Clothing & Textile Industry

Authors: Carl Munck af Rosenschöld & Joel Lindholm Tutor: Naveed Akhter

Date: 2021-05-23

Key terms: Sustainable Business Model, Organisation Barrier, Circular Economy, Clothing & Textile industry

Abstract

Background: Sustainability is becoming increasingly important from a consumer’s

perspective when it comes to their preferences. Simultaneously, mass-market apparel brands are struggling to meet the demand for sustainable clothing and textile products. The industry is in dire need for sustainable development as it is responsible for 8-10% of world’s greenhouse gas emissions and is the cause of 20% of the world’s wastewater. Therefore, it is vital to explore what the barriers are that hinders the development of sustainable business models and the consequences of these barriers.

Purpose: This thesis aims to explore which barriers and subsequent consequences Swedish clothing & textile organizations face when developing a sustainable business model.

Method: This study follows the interpretivist approach with inductively inspired reasoning. Qualitative semi-structured interviews are conducted on three different cases, which are analysed and compared using the general analytical procedure. The study used Snoek’s (2017) theoretical framework of internal and external barriers to explore the barriers in the Swedish clothing & textile industry.

Findings: This thesis contributes with comprehensive knowledge about barriers and their consequences in the Swedish clothing & textile industry with the help of Snoek’s (2017) framework of internal and external barriers. A total of 24 barriers were classified under four barrier categories; “Costly business model”, “Lack of awareness & low willingness to pay”, “Lack of transparency”, and “Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T

iii

industry”. Nine were new out of these 24 barriers. A theoretical framework is brought forward illustrating the interconnectivity between “consumer awareness”, “demand and willingness to pay for sustainable products”, “companies match the demand”, and after that “, creating demand for sustainable products”. This study’s findings extend the knowledge about the Swedish clothing & textile industry for organizations that wish to develop sustainability into their business model.

iv Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Problem statement 2 1.3 Purpose 4 1.4 Research Questions 4 1.5 Terminology 4 1.6 Abbreviation 5 2 Frame of reference 6

2.1 Method of constructing the Frame of reference 6

2.2 Sustainability 7

2.3 Sustainable business models in the clothing and textile industry 7

2.3.1 Circular fashion 8

2.3.2 Certification in the C&T industry 9

2.4 Organisational barriers 10

2.4.1 Overview of Barriers within the C&T industry 11

2.5 Internal Barriers 12

2.5.1 Technical Barriers 12

2.5.2 Operational Barriers 12

2.5.3 Financial Barrier 13

2.5.4 Knowledge & information Barriers 13

2.6 External Barriers 13

2.6.1 Market Barriers 13

2.6.2 Societal Barriers 14

2.6.3 Coordination & Cooperation Barriers 14

2.6.4 Infrastructural Barriers 15

2.6.5 Policy & Regulation Barriers 15

2.7 Gaps and summary 15

3 Method and Methodology 16

3.1 Methodology 16 3.1.1 Research paradigm 16 3.1.2 Research approach 17 3.1.3 Research design 17 3.2 Method 17 3.2.1 Data collection 17 3.2.2 Interview 18 3.2.3 Data analysis 21

v 3.3 Data Trustworthiness 23 3.3.1 Credibility 23 3.3.2 Transferability 23 3.3.3 Dependability 24 3.3.4 Confirmability 24 3.4 Ethical considerations 25 4 Empirical Findings 26

4.1 Costly Business Model 26

4.1.1 Company A 26

4.1.2 Company B 27

4.1.3 Company C 28

4.1.4 Aggregate findings for Costly Business Model 29

4.2 Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay 30

4.2.1 Company A 30

4.2.2 Company B 31

4.2.3 Company C 32

4.2.4 Aggregate findings for Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay 32

4.3 Lack of Transparency 33

4.3.1 Company A 33

4.3.2 Company B 34

4.3.3 Company C 35

4.3.4 Aggregate findings for Lack of Transparency 36

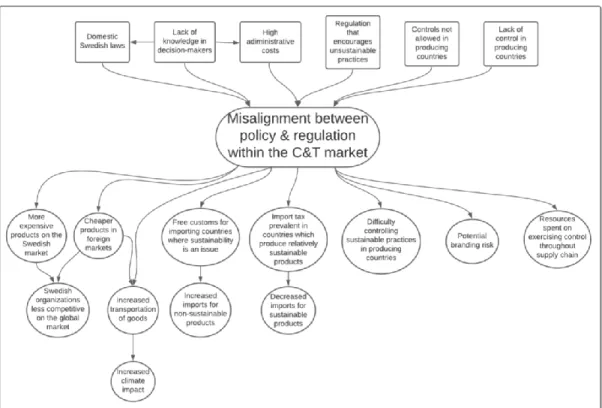

4.4 Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T market 36

4.4.1 Company A 36

4.4.2 Company B 38

4.4.3 Company C 39

4.4.4 Aggregate findings for Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T

market 39

5 Analysis 40

5.1 Costly Business Models 40

5.1.1 Increased material purchasing cost 41

5.1.2 Acquiring latest technologies 41

5.1.3 Lack of competence 41

5.1.4 Economic conflicts between countries 42

5.1.5 Difficulties finding external investments 42

5.1.6 Supplier selection when forming new relationships 42

vi

5.1.8 Aggregated overview of Costly Business Model 43

5.2 Lack of awareness & Low willingness to pay 44

5.2.1 Lack of consumer awareness 44

5.2.2 Consumers preferring price over sustainability & demanding sustainability at the

same price as conventional products 45

5.2.3 Lack of information about the impact of transportation on the environment 46

5.2.4 Companies not willing to pay for costly SBM 46

5.2.5 Uncertainty of payback from sustainable solutions & Lack of general definition of

sustainability 46

5.2.6 Aggregated overview of Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay 47

5. 3 Lack of transparency 48

5.3.1 Lack of advanced tracking systems 48

5.3.2 Costs related to implementing transparency 49

5.3.3 Selling channels pricing strategy 49

5.3.4 Aggregated overview of Lack of Transparency 50

5.4 Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T market 50

5.4.1 Domestic Swedish Laws 50

5.4.2 Lack of knowledge in decision-makers 52

5.4.3 Controls not allowed in producing countries & Lack of regulation in producing

countries 52

5.4.4 Aggregated overview of Misalignment between policy & regulation within the

C&T market 52 6. Conclusion 54 7. Discussion 56 7.1 Theoretical framework 56 7.2 Theoretical contributions 57 7.3 Managerial implications 58 7.4 Limitations 58

7.5 Suggestions for further research 59

8. Appendix 60

8.1 Quotes used from interviews in relation to the identified barrier categories. 60

8.2 Figures 70

8.3 Interview Questions 76

vii Figures

Figure 1. Process overview of General Analytical Procedure ... 21

Figure 2. Barrier Category identification process ... 22

Figure 3. Aggregate findings for Costly Business Model ... 29

Figure 4. Aggregate findings for Lack of awareness & low willingness to pay ... 33

Figure 5. Aggregate findings for lack of transparency ... 36

Figure 6. Aggregate findings for misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T market ... 40

Figure 7. Sustainable Supply & Demand Cycle ... 56

Figure 8. Aggregate findings ... 70

Figure 9. Costly Business Model for Company A ... 71

Figure 10. Costly Business Model for Company B ... 71

Figure 11. Costly Business Model for Company C ... 72

Figure 12. Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay for Company A ... 72

Figure 13. Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay for Company B ... 73

Figure 14. Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay for Company C ... 73

Figure 15. Lack of Transparency for Company A ... 74

Figure 16. Lack of Transparency for Company C ... 74

Figure 17. Misalignment between policy & regulation and the market for Company A ... 75

Figure 18. Misalignment between policy & regulation and the market for Company B... 75

Figure 19. Misalignment between policy & regulation and the market for Company C... 76

Tables Table 1. Table of abbreviations ... 5

Table 2. Search parameters for the frame of reference ... 6

Table 3. Information about the interviews ... 20

Table 4. Figure description ... 26

Table 5. Overview of barriers & consequences for Costly Business Model ... 44

Table 6. Overview of barriers & consequences for lack of awareness & low willingness to pay ... 48

Table 7. Overview of barriers & consequences for lack of transparency ... 50

Table 8. Overview of barriers & consequences for misalignment between policies & regulation within the C&T market ... 53

Table 9. Quotes regarding Costly business model for company A, B & C ... 62

Table 10. Quotes regarding lack of awareness & low willingness to pay for company A, B & C ... 64

Table 11. Quotes regarding lack of transparency for company A, B & C ... 66

Table 12. Quotes regarding misalignment between the market and policies and regulations for company A, B & C... 69

1 1 Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________

In this section, the reader is introduced to the background of the topic, the problem

statement, the purpose of this study, the chosen research questions, abbreviation table and terminology used throughout this research.

___________________________________________________________________________ 1.1 Background

The ever-increasing pressure of our planet’s scarce resources is leaving its mark on the global clothing & textile (C&T) industry (Niinimäki et al., 2020). The industry is in dire need of sustainable development. It is a $2.4 trillion-dollar industry that employs 60 million people worldwide (Un Alliance For Sustainable Fashion, n.d.). It is responsible for 8-10% of the world’s greenhouse gas emission, 20% of the world’s wastewater and 500 billion dollars lost due to underutilisation and lack of recycling (Un Alliance For Sustainable Fashion, n.d.). Therefore, making the C&T industry a great candidate for sustainable development as there is much room for improvement. Brand management, marketing and retailing are perspectives generally studied in the industry (Caniato et al., 2012). However, sustainability is

increasingly becoming a priority. The current linear “take-make-dispose” business model from the C&T industry needs to transition over to a more circular and sustainable business model (SBM) (Kim et al., 2021).

Previous literature has shown the importance of sustainability in the C&T industry for companies to remain competitive (Caniato et al., 2012). There is a considerable shift in demand for more sustainable products (Cheng, 2019). A SBM provides a green reputation which raises unit sales and prices due to increased willingness to pay for sustainable products (Moon et al., 2002). As a result, larger firms proactively develop sustainable initiatives (Wang et al., 2011). Sustainable initiatives such as recycling, upcycling and material circularity is a focus set by many organisations in the C&T industry (H&M Group, n.d; ESPRIT, n.d; Patagonia, n.d.).

The C&T industry plays an important role to reach the 17 sustainable development goals (SDG) by 2030 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). The SDGs intend to provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for the people and the

2

planet (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). Additionally, these SDGs are a guideline to reach the Paris Agreement, an agreement between countries to limit global warming to the preferable 1,5 degrees Celsius (United Nations Climate Change, n.d.). Patwary (2020) argues that the C&T industry needs to reduce its current emission level by half to reach the agreement. Patwary (2020) also argues that the top priorities of the C&T industry are to resort to renewable energy, minimise the usage of fossil fuels, improve energy efficiency, and attain a circular economy (CE). This focus on sustainable development from the Paris Agreement and SDGs encourages organizations in the C&T industry to adopt a more SBM.

Sustainability is becoming increasingly important from a consumer’s perspective when it comes to their preferences (Lee et al., 2020). Simultaneously, mass-market apparel brands are struggling to meet the demand for sustainable fashion products, as only 1% of new products introduced in the first half of 2019 were tagged as sustainable (Cheng, 2019). This

contradiction brings up the question that something is hindering C&T organisations from becoming sustainable. So, what are the barriers stopping C&T organisations from developing a SBM?

1.2 Problem statement

A sad truth about the C&T industry is that “a truly sustainable item does not exist in the market” (Patwary, 2020). Instead, products are made partially sustainable through, for

example, using 100% natural fibres or the significant stages in the production process running on renewable energy. Even if many organisations seek sustainability, there are gaps in the knowledge regarding how to make C&T products sustainable in all steps of the production process. Pal & Gander (2018) argue that what is essential to understand in designing a SBM in the C&T industry is that the value extends beyond customers and the company, which means the inclusion of the environmental and social impact of the organisation. Some examples of what a SBM can include are renewable energy and energy efficiency, eco-friendly raw materials, circular fashion, product longevity, supply chain transparency and conscious consumers (Patwary, 2020).

Further research is needed to understand the conditions when developing sustainability approaches (Lion et al., 2016). Additionally, more studies regarding barriers to developing a

3

SBM in the C&T industry is required (Kazancoglu et al., 2020). Studying barriers would provide a more holistic view of the sustainability challenges and opportunities (Pedersen & Andersen, 2015).

Hiller Connell (2010) brings forward the different barriers to C&T consumption and describes the necessity of further research within this area. As the industry is highly consumer-driven (Butler & Francis, 1997), many studies of barriers linked to the C&T industry have the perspective as consumer-centric (Ertekin & Atik, 2014; Desore & Narula, 2018). Barriers such as limited availability of ethical clothes, high price for sustainable products and lack of information towards environmentally friendly clothing are examples that hinder many organisations today in their decision-making (Desore & Narula, 2018). There is a clear need for knowledge sharing and collaboration between and across companies and sectors (Pedersen & Andersen, 2015). Chen et al. (2021) describe that there is “very little in the literature on the implementation of circular economy in the textile sector”.

A recent report from McKinsey (2020) states that to achieve short-term sustainability and reach the SDGs, fashion companies need to focus on improving their current business models through, for example, R&D and innovation. Opposing literature has also shown the

importance of making incremental improvements instead of drastic decisions (Pal & Gander, 2018), leading to a lack of competitiveness, customer value and profit. In more extreme cases, this can even lead to organisational failure. The fear of organisational failure can explain why large companies tend to focus more on incremental changes to develop a SBM (Caniato et al., 2012). There is a clear dilemma in which drastic improvements are necessary to reach the SDGs and Paris Agreement. However, incremental improvements are favourable for the sake of creating a long-term and durable SBM.

Qualitative research will be conducted on 3 Swedish organisations within C&T industry through semi-structured in-depth interviews. With the intent to explore, identify and illustrate the different barriers when developing a SBM. Additionally, to acknowledge their subsequent consequences, as to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, has not yet been targeted by previous research. This inductively inspired research will contribute with comprehensive knowledge about developing a SBM by exploring and illustrate the barriers within the C&T industry, both internal and external. This research provides organisations with an

4

barriers can then be considered in strategic organisational decision-making when trying to transition over to a SBM.

1.3 Purpose

This research aims to explore which barriers Swedish clothing & textile organisations are facing when developing a sustainable business model. Specifically, it is to add knowledge about the barriers in the Swedish clothing & textile industry and acknowledge the subsequent consequences of these barriers when developing a sustainable business model.

1.4 Research Questions

To meet the purpose of the proposed study, these are the research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What are the internal and external barriers within Swedish clothing and textile organisations when developing a sustainable business model?

RQ2: What are the subsequent consequences of these barriers within Swedish clothing and textile organisations when developing a sustainable business model?

1.5 Terminology

Circular Economy - A development model that seeks to minimise the negative impact of

human activities by applying principles related to the “3Rs”: reduce, reuse and recycle (Li et al., 2010), to maintain the highest utility value of products, components, and materials at all times (Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2015).

Circular Fashion - Clothes, shoes or accessories designed, sourced, produced and provided

to be used and circulate responsibly and effectively in society for as long as possible in their most valuable form and hereafter return safely to the biosphere when no longer of human use (Brismar, 2015).

Markup - The amount added by a seller to the cost of a commodity to cover expenses and

5

Stakeholder - Person who, besides their expertise, also are interested in shaping a given

reality because they are part of it (Mielke et al., 2017).

Sustainable Business Model - A business model that embraces the eight archetypes of

sustainable business models (Bocken et al., 2014); 1) Maximise material and energy efficiency, 2) Create value from “waste”, 3) Substitute with renewables and natural processes, 4) Deliver functionality, rather than ownership, 5) Adopt a stewardship role, 6) Encourage sufficiency, 7) Re-purpose the business for society/environment and 8) Develop scale-up solutions.

Sustainable Development - “The ability to meet the needs of the present without

compromising the same ability for future generations” (Brundtland, 1987).

Transparency - Being honest and open when communicating with stakeholders about matters

related to the business. May include transparency with 1) Investors and Shareholders, 2) Customers, 3) Employees, and 4) in the Supply Chain (GAN Integrity, n.d.).

1.6 Abbreviation

Abbreviation Description

BM Business Model

C&T Clothing & Textile

CE Circular Economy

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CF Circular Fashion

GOTS Global Organic Textile Standard

SBM Sustainable Business Model

SDG Sustainable Development Goals

6 2 Frame of reference

In this section, the reader is introduced to the theoretical framework, a review of existing literature on sustainability, sustainable business models, organisational barriers, internal barriers, external barriers, and gap & summary.

2.1 Method of constructing the Frame of reference

This theoretical framework provides a literature review of earlier research. The aim was to find relevant literature which ties barriers to the development of a SBM. Several keywords deemed relevant to the topic were chosen and used on Primo JU and Google Scholar

databases. The researchers performed an extensive search of only peer-reviewed articles and scholarly books, which got narrowed down to the most relevant to this research. The most relevant articles were chosen by skimming through the literature and only selecting the ones that correlated with barriers towards the development of a SBM. Recent articles ten years or less were preferred, but older ones were also accepted if deemed relevant enough. The reasoning behind the timeframe was due to the rapidly changing environment in the C&T industry.

Databases Primo (JU Library), Google Scholar

Keywords Sustainability, Circular fashion, Sustainable business models, Certification in clothing and textile organisations, Organisational barriers, Barriers when implementing sustainable business models, Textile industry, clothing industry, Barriers Sustainable Textile Industry

Sources Academic Articles, Academic Books, Websites

7

The purpose of this frame of reference is to guide the reader from a broad perspective about sustainability and then narrow it down to the topic of choice. After being introduced to the concept of sustainability, the reader is introduced to a SBM and, after that, Circular Fashion. Then, certification within the C&T industry will be brought up and thereafter introduced to barriers, both internal and external.

2.2 Sustainability

Sustainability is a vast and complex research area. One of the biggest challenges when it comes to sustainability research is the lack of a standard definition. Additionally, there is an abundance of synonyms used for it (Moore et al., 2017). One of the first definitions of sustainability was about development and defined it as the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations (Brundtland, 1987). Since then, sustainability has become increasingly popular within organisations and links to other business-oriented concepts such as internalization, organisational strategy, leadership, competitiveness, and organisational change (Kolk & Pinkse, 2008). Despite this, numerous gaps in the sustainability literature still exist. For example, the notion of sustainability is still not agreed upon in the research field and a standard definition for it (Bateh et al., 2013). According to Fibuch & Way (2012), “there are at least 50 definitions of sustainability in the literature” (p.36). Hence, sustainability would benefit from a standard definition due to leaders in organisations creating a narrow view of sustainability that only fits their sphere of performance (Bateh et al., 2013). The definition brought forward from Brundtland’s report (1987) is the most widely accepted definition throughout the sustainable development literature, and will be used in this study.

2.3 Sustainable business models in the clothing and textile industry

To include sustainability in an organisation’s business model (BM) has become a strategic mean by management. To fulfil the demand for sustainability, especially from younger consumers and get a competitive edge (Kim et al., 2021). The development of a SBM derives from the regular BM that maps out the creating, delivering, and capturing value in the

organisation (Viciunaite & Alfnes, 2020).

According to Nosratabadi et al. (2019), there are four main approaches to designing a SBM; Sustainable value proposition, creation, delivering and sustainable partnership. They all stress the importance of including the environmental and social aspects (Pal & Gander, 2018). What

8

is essential to understand in designing a SBM in the C&T industry is that the value relationships extend beyond customers and the company.

For an organisation to develop a SBM, they need to find innovative ways to include environmental values as a core driver in the business (Todeschini et al., 2017) instead of “business as usual”, where profit is the main driver. This transition needs to succeed without compromising the current customer value provided by the organisation, as that could lead to a loss of competitiveness, customer value, and profit (Pal & Gander, 2018). Due to this, it would be interesting to explore what barriers organisations in the C&T industry need to overcome in order to achieve a SBM.

Several trends are pushing for increased sustainability within organisations in the C&T industry. Firstly, the consumers are getting more aware of the environmental damage and prefer green products (Todeschini et al., 2017). Jung & Jin (2016) found that consumers are willing to pay a premium price for slow fashion thanks to the increase in perceived value when consuming sustainable products. Secondly, the CE is becoming a way for C&T

organisations to transform their linear business model towards an increased circular one, thus improving their sustainability (Todeschini et al., 2017). The CE is a development model that seeks to minimize the negative impact of human activities by applying three principles, also called the “3 Rs”: reduce, reuse & recycle (Li et al., 2010). These 3Rs have then developed into the 9Rs: Refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle, recover, refuse, rethink, reduce, reuse and repair (Kazancoglu et al., 2020).

One way of achieving a CE is to look at the flow of materials in the different stages of production and try to narrow, slow and close the different steps (Pal & Gander, 2018). If C&T organisations are going to provide consumers with a SBM, transparency throughout the supply chain is vital. Without it, consumers will not gain the added value of sustainable initiatives (Viciunaite & Alfnes, 2020).

2.3.1 Circular fashion

The term circular fashion (CF) is a relatively new concept in the C&T industry. CF inspires itself from the CE and its principles. Hence, reducing the environmental impact due to less resource usage and less waste from keeping materials in a circular loop (Muthu, 2018). CF has three principles: designing out waste and pollution, keeping fashion products and materials in longer continuous use, and regenerating natural systems (Ki et al., 2020). CF is

9

the movement and commitment to transform the products and systems in the C&T industry towards increased ecological integrity and social justice (Kim et al., 2021). Different CF examples are good working standards, sustainable business models, and organic materials (Ki et al., 2020).

The Take-back system is one way to transform the linear business model to become increasingly circular. This system focuses on taking back clothes and textiles in good condition and thereafter selling them in the second-hand market (Kim et al., 2021), which is also applicable for unsold stock. The implementation of take-back systems is increasingly introduced by C&T retailers to facilitate value creation from the second-hand market (Hvass & Pedersen, 2019). Take-back systems can be implemented in organisations, meaning the development of recycling, reusing, and up-cycling systems that will close the loop of the product life cycle (Corvellec & Stål, 2019).

According to Wagner & Heinzel (2020), consumers’ awareness of CF and sustainable manufacturing with the use of recycling, reuse, and up-cycling are the key elements to decrease the impact which the C&T industry has on the environment. One of the findings provided by Kim et al. (2021) shows that emotional value is the most crucial incentive for consumers' awareness when it comes to CF. However, the perception of a sanitary risk is the biggest reason for consumers not buying recycled, reused, and up-cycled clothes. This perception allows organisations to act as educators when it comes to take-back systems and a chance to increase the emotional value consumers will gain from CF.

Second-hand shopping is one of the best ways to contribute to CF, thanks to the satisfaction of both sustainability and profitability. Online second-hand stores have become increasingly popular with the digital era, making social media platforms such as Instagram with their younger user base an essential driver towards CF (Shrivastava et al., 2021). That could be explained by the increased awareness from millennials and gen Z about environmental issues and their consequences (Kim et al., 2021).

2.3.2 Certification in the C&T industry

Certifications have been around since 1977 (Grolleau et al., 2015) but have rapidly grown in numbers and usage due to the increased consumer awareness and globalization. Certification is any mark, logo, or symbol provided by a third party to help consumers make educated

10

purchasing decisions (Lee et al., 2020). Currently, in the C&T industry, there are over 100 eco-labels used (Henninger, 2015).

According to Muthu (2015), certifications show several aspects of the product: That it is safe in terms of human health, produced with environmentally friendly materials & technologies, produced by taking into consideration the health and safety of the workers, and produced concerning social criteria in terms of the human rights of workers. Another study also brings up that certifications are highly driven by strategic factors, marketing considerations and information when it comes to sustainability in the C&T industry (Oelze et al., 2020). Their study also states that certifications give organisations competitiveness in the market and sustainability awareness in the C&T supply chain.

Findings by Lee et al. (2020) about certifications in the C&T industry states a significant correlation between certification and trust from consumers. But also, a significant increase in purchase intention. That can be explained by the trust that certification gives consumers when purchasing a product or service. The certifications provide information about the product's best attributes, but they could also be used to greenwash the products (Grolleau et al., 2015). That can happen due to many different certifications in the C&T industry, making the

consumer think they purchased a green product. However, the certification means something else (Grolleau et al., 2015).

2.4 Organisational barriers

While change is crucial for organisations across industries, organisations still report a high failure rate regarding change initiatives at about 70% (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, 2015). This failure results from barriers companies face and hindering their ability to carry out the

change. Since change is such a pivotal factor within organisations (Robbins & Coulter, 2016), knowing what factors hinder it would greatly benefit any organisation that wants to stay competitive in its respective market.

According to the current literature on organisational barriers, they are industry-specific (Desore & Narula, 2018). Many studies have had the focus on revealing organisational drivers & barriers (Worku, 2016; Vladislav et al., 2016; Kahiya & Dean, 2016) and the integration of sustainability into their business models (Renukappa et al., 2013; Rezaee, 2016; Cici & D’Isanto, 2017).

11

2.4.1 Overview of Barriers within the C&T industry

Most of the current literature about barriers within the C&T industry focuses on transforming from a linear economy to a CE and sustainable supply chain management (Kazancoglu et al., 2020; Galvao et al., 2018; Snoek, 2017.). Below, earlier research about barriers within the C&T industry will provide an overview of the barriers to developing sustainable practices. Kazancoglu et al.'s (2020) article about sustainable supply chain management plays an essential part in developing a SBM within the textile industry. Their research found 25 barriers within nine categories: Management and decision making, Labour, Design

challenges, Materials, Rules and regulations, Knowledge and awareness, Integration and collaboration, Cost and Technical infrastructures.

Galvao et al. (2018) analysed 195 papers about the barriers when implementing CE and found that the most frequent barriers were; Technological, Policy and regulatory,

Managerial, Performance indicator, Customer, and Social.

Juliane & Ana’s (2020) article regarding the integration of sustainability into corporate strategies within the C&T industry found the barriers to be: Standards and regulations,

consumer behaviour, limited options and comparability, sustainability as a business case, value chain management, data handling and trade-off between quality and durability.

Chen et al.'s (2021) study about analysing the causal relationships among the CE barriers in the textile sector brought forward 12 different barriers through their literature review:

Consumers' lack of knowledge and awareness about reusing/recycling, the high purchasing cost of environmentally friendly materials, lack of successful business models and

frameworks to implement CE, lack of support supply and demand network, obstructing laws and regulation, design challenge to reuse and recover products, limited availability and quality of recycling material, lack of information exchange system between different stakeholders, unclear vision in regards of CE, insufficient internalization of external costs, high short-term costs and low long-term economic benefits and make the right decision to implement CE most efficiently.

Snoek (2017) brought forward a framework that consists of two parts, internal and external barriers, to develop CE practices within the textile industry. The internal categories include

12

barriers. The external categories include market barriers, societal barriers, cooperation & coordination barriers, infrastructural barriers, and policy & regulation barriers. Snoek's

(2017) framework is studied in the start-up context, but in the research, Snoek mentions that it can be applied to other contexts. Therefore, the researchers of this study deemed it relevant to use the framework in the Swedish C&T industry due to its generalizability. In section 2.5 and 2.6, the previous literature about barriers in the C&T industry brought forward in section 2.4.1 will be discussed through Snoek's framework to find similarities and differences. 2.5 Internal Barriers

2.5.1 Technical Barriers

The first barrier mentioned in Snoek’s (2017) framework is the technical barrier that organisations can face. Snoek (2017) brings up the lack of infrastructure to shift a linear business model towards a circular one. The products are made from various materials, which decrease the ability to extract resources from products. These difficulties in extracting resources due to the complexity in the material composition are also brought forward in Kazancoglu et al.’s (2020) study. This study also mentions materials and design challenges when developing CE. In addition, Chen et al. (2021) also brought up design challenges but focuses on the reuse and recover aspect of these products.

Furthermore, Juliane & Ana’s (2020) brings up the trade-off between quality and durability. This barrier describes that sometimes sustainable measures can harm the quality aspect of the product. Meaning sustainable material does not always have the same quality as new

conventional products. 2.5.2 Operational Barriers

The operational barrier when developing a SBM usually comes down to the need for a complex data system that can handle all the information (Snoek, 2017; Chen et al., 2021; Juliane & Ana, 2020). Kazancoglu et al. (2020) argue that the lack of a detailed and

standardized measurement system that can provide feedback and performance index hinders the ability to implement CE. In the same article, the lack of traceability is brought up.

Meaning that organisations need ways of tracing their recycled materials, where the materials came from and whether the information is correct. However, Juliane & Ana (2020) does not mention a need for an accounting system. However, they bring up the difficulties of handling

13

large and complex sustainability data from different sources and efficiently using it and generating a more significant customer value.

From another perspective, Kazancoglu et al. (2020) mention the barrier of lack of acceptance of new business models as it requires fundamental changes in organisational structure, company culture, supply systems, manufacturing methods, and target market.

2.5.3 Financial Barrier

When transitioning toward an improved SBM, the investment cost for sustainability is significantly higher than conventional practices (Snoek, 2017; Kazancoglu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). At the same time, there is an uncertainty in profitability and returns on these investments of sustainable practices due to the low demand, which hinder the large-scale production of sustainable products (Kazancoglu et al., 2020). Additionally, Juliane & Ana (2020) confirms this increase in cost with sustainable products by highlighting one barrier; the increased cost of sustainable materials. These costs explain the uncertainty of profitability and return on investment. Sustainable material usage comes with a high short-term cost and low short-term benefits (Kazancoglu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). Furthermore, the production cost, limited and availability of sustainable material, difficulties in establishing correct product prices and limited funding are several factors that increase the cost of sustainable products (Chen et al., 2021).

2.5.4 Knowledge & information Barriers

Kazancoglu et al. (2020) and Snoek's (2017) both state that a barrier to implementing CE is the lack of awareness regarding CE and the benefits of implementing it. They also brought up the lack of technical and theoretical knowledge within an organisation. Meaning that

organisations do not have the competence or capacities within the business on how to

implement sustainable practices, what materials to use and how to develop new technologies. 2.6 External Barriers

2.6.1 Market Barriers

A market barrier that is prevalent in Snoek (2017) is the lack of willingness from consumers to pay for the markup in products. Due to the market being dominated by low prices,

14

companies have difficulties highlighting the advantages of sustainable C&T products online and competing with the growing low-price market (Juliane & Ana, 2020). This habit of low prices contributes to the low willingness to pay for consumers. Additionally, the lack of sustainable options on the C&T market is a barrier itself as there is a lack of sustainable products at a larger scale.

2.6.2 Societal Barriers

Consumers' lack of awareness regarding environmental problems is a barrier to develop a SBM, as they do not see the benefits of sustainable products, which makes organisations hesitant to change, and continuously operate business as usual (Snoek, 2017). Consumers' lack of awareness and interest regarding sustainability will make managers and policymakers even more hesitant within an organisation where the culture does not support sustainability (Chen et al., 2021). The study from Juliane & Ana (2020) agrees with this; however, they bring up that consumer awareness can be a driver towards sustainability as it is increasing. In contrast, they also underline that consumers are educated to buy low-priced products instead of sustainable ones, as long organisations such as Primark and H&M continuously offer cheap bargains. Thus, consumers' low willingness to pay makes it difficult to raise the prices for sustainable products higher than conventional ones.

2.6.3 Coordination & Cooperation Barriers

According to Kazancoglu et al. (2020), there are three barriers to coordination and cooperation in the supply chain. Firstly is the lack of sharing information, meaning not effectively communicating about the awareness of CE. Juliane & Ana’s (2020) study also highlighted the barrier of not sharing information and effectivizing communication as this would lead to suppliers not following sustainability initiatives from the organisation. Secondly, organisations do not have long-term suppliers, leading to quality problems from raw material to the finished product. The dependability of other suppliers that lack long-term relations is often accompanied by a lack of, or low, level of trust (Snoek, 2017). Thirdly is the lack of shared vision and willingness to collaborate between supply chain partners, which is emphasised by Juliane & Ana (2020) and Snoek (2017).

15 2.6.4 Infrastructural Barriers

The lack of support for recovery after engaging in environmental activities is an

infrastructural barrier (Snoek, 2017). Kazancoglu et al. (2020) added the complexity of reverse logistics and how it hinders organizations from implementing CE practices. Their study brought forward the collection & separation problem and the inadequate facility infrastructure. Juliane & Ana (2020) mentioned the transportation barrier within the

infrastructure where transportation from Asia to Europe is challenging to render sustainable, and the need for plastic packaging to protect products from the external environment. 2.6.5 Policy & Regulation Barriers

Chen et al. (2021) bring up the barrier of obstructing and unsupportive laws and regulations on waste management from government authorities. Kazancoglu et al. (2020) complement this by bringing up the lack of sectorial standardization, leading to failure in certain standards to collect and recycle waste. In addition, this study and Juliane & Ana (2020) mention the lack of sustainability labels covering the entire life cycle of a product. Julaine & Ana (2020) also bring up competing and overlapping sustainability standards addressing similar issues, creating confusion and uncertainties among companies. Companies feel the lack of

government support and regulations not being industry-friendly towards achieving sustainability in a more general sense.

2.7 Gaps and summary

After conducting a literature search and acquiring a good overview of the current literature regarding barriers towards implementing a SBM in the C&T industry, some gaps became visible. Firstly, barriers had been categorised and identified in several studies (Snoek, 2017; Kazancoglu et al., 2020; Juliane & Ana, 2020; Chen et al., 2021), but to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, none have brought forward the consequences of these barriers that the organisations are facing. Juliane & Ana (2020) have specified that further research is needed in the form of multiple case study analysis in their study about integrating

sustainability into corporate strategy. In Kazancoglu et al.’s (2020) study about barriers for circular supply chains for sustainability in the C&T industry, the developed framework was applied to the Turkish context. The need for other contexts is mentioned along with Juliane & Ana’s (2020) study.

16

In a more general sense, the C&T has little literature about CE development (Chen et al., 2021). As the C&T industry is a long way from becoming fully sustainable, understanding what is stopping companies from adopting a SBM can aid the development of sustainable solutions to overcome these barriers.

3 Method and Methodology

_________________________________________________________________________

This section introduces the reader to four categories; methodology, method, data trustworthiness, and ethical considerations. The methodology will include the research paradigm, research approach, and research design, while the method will provide in-depth knowledge about the data collection, the interview process and data analysis. Data

trustworthiness brings forward the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the study. Finally, ethical considerations will be provided.

________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research paradigm

The research paradigm serves to know what philosophical framework will be used as a base of how the study will be carried out when it comes to the research methodology. There are two main paradigms, positivism and interpretivism. The interpretivism paradigm embraces the belief that social reality is not objective but is shaped by our perception, making it highly subjective (Smith, 1983). This study will become subjective as the researcher will interact with the social reality of the cases and influence the research. Additionally, this correlates with the qualitative methods that “seek to describe, translate and otherwise come to terms with the meaning, not the frequency of certain more or less naturally occurring phenomena in the social world” (Van Maanen, 1983) used by interpretivists and in this study.

In contrast, the positivist paradigm stems from the belief that social reality is independent and objective, that the research of a phenomenon is not affected by the researcher (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Thus, the positivism approach cannot be undertaken in this study as it fails to consider the subjective aspect of the development of a SBM within the C&T industry.

17 3.1.2 Research approach

As an interpretivist research philosophy leads this study, the reasoning will be inductively inspired, which means that the study will not be purely inductive with no use of prior theories. Instead, this study will use existing theories and literature to build a foundation of pre-existing knowledge, which will then contribute to the development of new findings using acquired empirical data collected from the interviewed organisations. By taking this

approach, the discovered patterns from the empirical data combined with existing literature extend our current knowledge about this phenomenon (Bryman & Bell, 2019) and develop a potential theory. In terms of this study, the phenomenon is organisational barriers and subsequent consequences in the Swedish C&T industry when transforming towards a SBM. 3.1.3 Research design

The research design refers to the choices in terms of methodologies and methods made to satisfy the purpose of the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The chosen design of this study is a multiple case study to explore the differences and similarities between various cases

(Gustafsson, 2017). The reason behind this is to obtain in-depth knowledge about barriers when developing a SBM and contrast different cases to seek various patterns and

relationships. Multiple case studies will provide more trustworthy and credible data thanks to findings grounding themselves in several cases compared to a single case study (Baxter & Susan, 2008).

As this study is looking for patterns within collected data to develop findings, this study is exploratory. Snoek’s (2017) framework of internal and external organisational barriers for implementing CE practices in the C&T industry is used to categorize the empirical data from this study. Due to the similarities between Snoek’s study and this one, the researchers deemed it suitable to select this theory and apply it to the Swedish context.

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Data collection

The data collection process started with searching for companies with a well-known sustainability certification in the Swedish C&T industry. The reasoning behind this was to select companies that showed the intent of becoming sustainable. Additionally, the

18

researchers deemed it interesting to discover the barriers to sustainable development when efforts had already been made within organisations, which certification represents. The sustainable certifications were the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), Fairtrade, Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), Global Recycled Standards (GRS), Responsible Wool Standard (RWS), and the Responsible Down Standard (RDS).

The researchers contacted about 15 organisations in the Swedish C&T industry by using the search engine Google to find companies with the mentioned certifications and are based in Sweden. These organisations were contacted through emails and contact forms. Additionally, the researchers used joint contacts to find the participants that fit the criteria mentioned above. The researchers requested interviewees who could answer questions targeting barriers and consequences when developing a SBM.

Out of the 15 organisations the researchers contacted, ten responded. Five out of these ten agreed to participate in the study. The other five organisations declined due to time and resource constraints. When planning the dates for the five onboard companies, only three answered, and the remaining two did not respond. Due to this small batch of cases, the researchers felt the empirical data was too scarce. Therefore, follow-up interviews were conducted with each company to acquire sufficient data and gain in-depth knowledge about the subject to come up with a satisfactory analysis.

This study used interviews as a primary data collection method to get an in-depth

understanding of the phenomenon. Additionally, the reasoning behind using interviews was to utilize the interviewee’s expertise to get their opinion and facts on the phenomenon. The chosen interview structure was semi-structured with open-ended questions to allow the interviewee to add concepts and information that were not asked initially from the structure of the interview questions.

3.2.2 Interview

The interview aim was to explore the different barriers Swedish C&T organisations encounter when developing a SBM. Additionally, acknowledging how these barriers affect the

organisations. Every question provided consisted of two different sections. The first section tackled the identification of the barriers and the second the consequences that the barrier had

19

on the organisations when developing a SBM to answer both research questions. The total time of the first interviews aimed to be approximately 60 minutes to respect the time taken from the respondents. The follow-up interview aimed to be 20-30 minutes.

To start the interviews in an easy and comfortable way for the participants, the researchers asked them to start by introducing themselves and share their professional position in their organisation. The researchers then introduced the purpose of the study and offered the interviewee anonymity if requested to respect their privacy. Lastly, before starting the interview itself, permission to record was asked for the researcher to go back and transcribe the interview to find patterns. The goal was to ensure a comfortable environment by starting with internal organisational barriers and questions where answers are straightforward. Thus, to improve the interviewee's confidence so the quality of answers could be improved. The interview consisted of two parts; internal barriers and external barriers of the Swedish C&T organisation. The two parts aimed at gaining an overview of the industry and the organisation at hand.

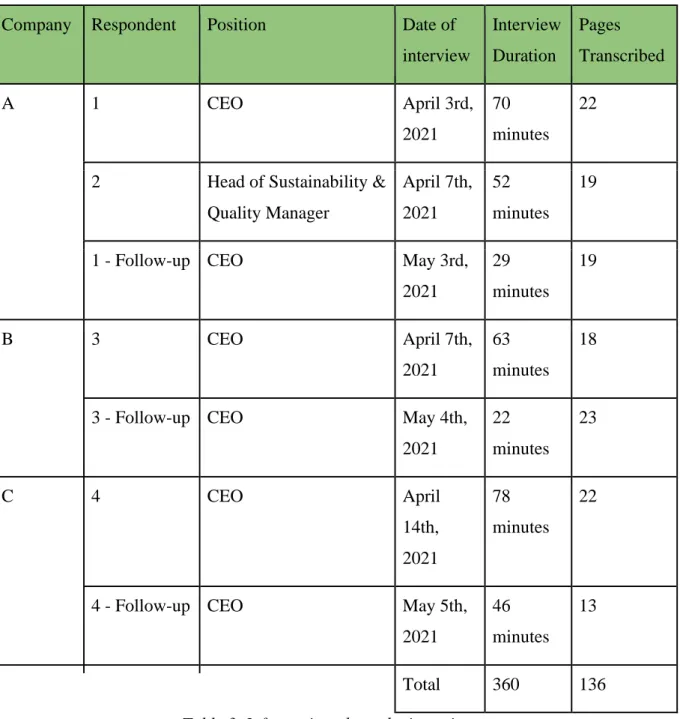

This study included people which professional position are involved in developing business models and sustainability within the organisations. That would provide the most relevant data and information for the study. Additionally, the interviewees could choose the language for the interview, either in Swedish or English, based on what they deemed would provide the interview with the best possible data. To provide a sense of comfort and flexibility compared to being obligated to speaking English and possibly creating a language barrier. Table 3 below brings forward an overview of relevant information of the interviews.

20

Company Respondent Position Date of

interview Interview Duration Pages Transcribed A 1 CEO April 3rd, 2021 70 minutes 22

2 Head of Sustainability & Quality Manager April 7th, 2021 52 minutes 19

1 - Follow-up CEO May 3rd,

2021 29 minutes 19 B 3 CEO April 7th, 2021 63 minutes 18

3 - Follow-up CEO May 4th,

2021 22 minutes 23 C 4 CEO April 14th, 2021 78 minutes 22

4 - Follow-up CEO May 5th,

2021

46 minutes

13

Total 360 136

Table 3. Information about the interviews

A pilot study was conducted to ensure the quality of questions and was performed a week before any other interview. The pilot study provided the opportunity to improve any questions that felt irrelevant or challenging to a greater extent. Furthermore, it lets the

researchers refine their interviewing techniques and provide a better experience for all parties in the upcoming interviews.

21 3.2.3 Data analysis

The general analytical procedure from Miles and Huberman (1994) guided the data analysis process. The general analytical procedure is not tied to any particular data collection method and can be analysed systematically. The procedure includes three steps: 1) Data reduction, 2) Data display and 3) Conclusions and verification.

Figure 1. Process overview of General Analytical Procedure

The first step regarding the data analysis in this study was the data reduction, where the data collected was reduced to the most relevant findings. This study followed Snoek's (2017) theoretical framework of internal and external barriers. This framework aided in the sense that pre-existing categories could enable the researchers to structure the data collection process. After that, the data coding began where the researchers divided the transcript to code the data separately using these categories. The researchers then compared the codes to

mitigate the bias of the study and, at the same time, reduce the data collected to find recurring patterns and themes. After comparing the findings from both researchers, the transcripts could be narrowed down to 24 codes within Snoek's framework, as shown in figure 8 in the appendix. After that, these codes were compared to find similarities for themes to emerge. This data display fulfils the second stage of the general analytical procedure by displaying the data.

The empirical findings present the barrier categories along with the analysis. The criteria for these categories were that 1) They were relevant according to this study, and 2) They covered

22

numerous identified barriers. In total, four barrier categories were identified and are the following: Costly Business Model, Lack of awareness & low willingness to pay, Lack of transparency and Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T market. Chapter 4 & 5 discusses these barrier categories further.

The final step in the general analytical procedure in this study is the conclusion and

verification. The conclusions and verifications were done by analysing the identified findings internally and after that externally. Internally means that the cases were analysed

individually, and if there was more than one interview per case, the findings were compared to recognise if the data was cohesive. Therefore, increasing the dependability of the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). After that, the cases were externally analysed with a cross-analysis to find similarities and deviations to answer the research questions.

While exploring the different barriers, the focus was also on asking about these barriers' consequences. Figure 2 shows the data collection process of the barrier, barrier categories and consequences. Figure 8 brings forward these results in the appendix.

23 3.3 Data Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is essential to ensure that the data being collected and analysed will provide quality findings. There is a high level of validity in an interpretivism methodology due to the in-depth data collection methods, with sample sizes representing the phenomenon. However, a lack of reliability occurs due to the interpretation of data differentiating from person to person. Therefore, this study has taken into account four different steps to increase trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.3.1 Credibility

In a qualitative study, the perspective is about the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings to ensure the highest quality possible (Cope, 2014). Credibility refers to the research being conducted to ensure that the phenomenon is identified and described in a trustworthy way (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, triangulation is a way to increase credibility and trustworthiness by using multiple data sources, methods, researchers, and theories. Hence, in this study, the interpretation of the findings will have multiple perspectives due to several cases, primary data, earlier research, two researchers, which will increase credibility and reduce the bias of the findings (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

In this study, to get a broad and rich understanding of the topic and at the same time increase the credibility, a multiple case study method was used to collect the primary data. The

interviewed people had different positions within the organisation. To compare organisations and several perspectives to get a more nuanced result and stronger credibility than a one case study would provide. Furthermore, to get a comprehensive understanding of the topic and reduce bias when conducting the interviews, earlier research was used to produce the frame of reference and the problem statement. During the interviews, notes were taken separately by the researchers. The researchers analysed the data separately and then compared it

collectively to reduce the bias and increase the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings. The triangulation resulted in increased credibility and trustworthiness in the study.

3.3.2 Transferability

Transferability is concerned with the possibility of applying the findings to other settings or groups that are sufficiently similar to permit generalization (Cope, 2014). The generalization

24

is the ability to extend findings from the research of the sample group and often towards the population (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Hence, the transferability corresponds to the external validity of the study. This study will result in high validity due to the in-depth findings collected from purposeful sampling with CEOs and the Head of sustainability with the use of multiple cases. Furthermore, due to the professional top-positions of the sample, the results can likely be transferred into similar contexts.

3.3.3 Dependability

Dependability in qualitative research is to what extent the study could be repeated by other researchers and have similar findings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). A way to achieve this is by having another researcher agree with the decisions made at each stage of the process (Cope, 2014). Therefore, the researchers have kept all documents notes on all the process steps, audio tracks from interviews, and transcripts in this study. To aid the study being performed again by other researchers and get similar findings. Thus, increasing the study's

trustworthiness, but what needs to be kept in mind when doing a qualitative study under the interpretivism paradigm is that the findings are interpretations of the researcher and his/her reality. Therefore, even if this study is transparent, other researchers can interpret the findings differently.

3.3.4 Confirmability

Confirmability is the neutrality of the research interpretation (Collis & Hussey, 2014), which means the researcher's ability to prove that the data and findings represent the participants' reply and not the researchers' biases or viewpoints (Cope, 2014). In this study, to gain an objective understanding of the research context, a literature review of the most current articles was conducted. It made it possible to structure the interview questions in categories taken from Snoek (2017), therefore reducing the bias of questions asked during the

interviews. During the data analysis, quotes provided transparency and trustworthiness to produce unbiased findings. All this, to obtain a high degree of confirmability.

25 3.4 Ethical considerations

This research has considered the ethical side throughout every process. Including the research problem, research questions, research design, data collection, data analysis, and the reporting of the thesis. Therefore, due to the competitive nature of the C&T industry, sensitive

information has been handled with the utmost care. Hence, it was vital to provide

confidentiality for the participants of this research and respect their will to be anonymous. Full consent from every participant was obtained before their interview to ensure

confidentiality if necessary.

Additionally, the study's purpose was sent beforehand with the interview questions. The reasoning behind this was to ensure full transparency of the study and improve the quality of answers. The participants were informed during the interview of how their data would come to usage in this study. Furthermore, it was made clear that the participants could withdraw at any given time from the study if they chose to do so. Participating in the study was voluntary, and no incentive was given to the participants to avoid any form of bias.

Another considered issue was the importance of remaining objective throughout the study, especially during the interview. The researchers tried to not be suggestive in any way to get unbiased, organic data during the interview. The aim was to clarify if something felt unclear through repetition but not to bring forward new ideas or findings that could negatively affect the research's authenticity.

26 4 Empirical Findings

_________________________________________________________________________

This section introduces the empirical findings to the reader. The findings consist of several barrier categories. The identified barrier categories are Costly Business Model, Lack of awareness & Low willingness to pay, Lack of transparency, and Misalignment between policy & regulation within the C&T market. Company A, B and C are then applied to these categories.

_________________________________________________________________________

A figure with the aggregate findings is displayed at the end of each category. Table 4 below displays the shapes and meaning of the barrier, barrier category and consequences of the empirical data in the aggregated findings. This table ensures that the readers will have all the information necessary to understand figures 3, 4, 5 and 6. Quotes relevant to each company and barrier category are presented in Tables 9, 10, 11 and 12 in the appendix.

Shape Meaning

Barrier

Barrier category

Consequence

Table 4. Figure description

4.1 Costly Business Model

4.1.1 Company A

After conducting the interviews, it was evident that the lack of financial strength from developing a SBM was a significant barrier. Several findings showed that this is an issue across many different barrier categories and often tied to the costs that a SBM within the Swedish C&T industry brings with them. For company A, this was mentioned several times

27

during the interview across various barriers. Interviewee 2 even defined this as the “biggest obstacle” within their BM. All interviews mentioned this barrier category.

Firstly, the higher production costs from the material purchasing and the sustainable methods mean that the overall products become more costly to produce when compared to the average conventional, non-sustainable methods. As interviewee 1 stated:

“Throughout the supply chain, it is more expensive to make a truly sustainable business model than fast fashion” - CEO.

Additionally, due to the complexity of sustainable textiles, it is necessary to gain considerable expertise in the area. This expertise is either in-house or outsourced but remains a cost in both cases. This knowledge about sustainable materials, methods, and the product itself is an upfront cost when acquiring them. It requires continuous follow-ups to guarantee that sustainable methods are executed correctly throughout the supply chain. As interviewee 1 states: “You need certain skill sets which are more expensive”.

Another barrier that a SBM brings in regards to cost is supplier selection. Sustainability is often tied to long-term relationships but is prone to increased costs when trying to build trust with new suppliers and “commit to suppliers in another way” when compared to conventional BM. A consequence mentioned of these increased costs is the lowered margin for sustainable products.

Furthermore, it is difficult for companies to find investments, especially from banks. Interviewee 1 also stated that it is a “huge problem for smaller businesses to get financial support for their business models”.

4.1.2 Company B

Two areas surfaced during this interview. Firstly, was the dependability organisation had on the margin of products which hinders organisations from developing a SBM. “If it is listed companies or investment companies that are in, then the margin is always the most

28

is used instead of organic. Additionally, companies chose certifications with less strict standards and cheaper options to increase the margin.

“All brands are after all, especially now during the corona, everyone is so dependent on their margin [...] Now they go back to either conventional cotton and produce in Bangladesh in bad factories or they go to a cheaper alternative such as better cotton initiative.” - CEO

The second financial struggle was finding external investment when trying to develop

sustainable projects within the organisation, which hindered the development of a SBM. This, in turn, leads to sustainable projects requiring financing not being able to be developed.

Furthermore, interviewee 3 brought up three negative factors that further increased the cost of producing sustainably, one being the Trade War between The United States and China. All the Chinese cotton was banished, and organisations instead started to buy up the remaining cotton in India. This resulted in a cotton shortage and made it extremely hard to find organic cotton. Also, at the same time, the certification organisation GOTS went through their transaction document and saw that they had certified 2000 metric ton of organic cotton in India. However, the country is only able to produce 800 metric ton. They found that the producers and intermediaries had diluted the organic cotton. GOTS then removed 80% of all who had the certification and processed organic cotton. Furthermore, cotton traders in India saw where this was going and purchased the remaining cotton and put it in storage to drive up the price even further. As interviewee 2 stated: “The price of cotton is higher than it has ever been”.

4.1.3 Company C

The first issue in this regard was that acquiring the latest technologies often entailed a trade-off in costs.

“So, a technical barrier is when the machines become more expensive.” - CEO

This cost of acquiring new technologies is tied to reduced profit margins and leads companies only to adopt sustainable solutions if they have to. As demand for conventional cheap

29

products is still higher than sustainable products, organisations selling textiles can utilize this and keep selling the current demand to keep the margins high.

The second area which was covered when it comes to costly business models was the competence needed to transition towards a SBM. Knowledge about the complexity that sustainability brings can be achieved by hiring external consultants or employing people. As interviewee 3 states: “...you can buy competence, but it costs. In the end, it will very much be a financial or resource issue.”

4.1.4 Aggregate findings for Costly Business Model

As seen in the figure below, the first row represents the identified barriers from the

interviews, which form the barrier category on the second row - Costly Business Model. The third row consists of the consequences of this barrier category that emerges from the

previously identified barriers.

30 4.2 Lack of Awareness & Low willingness to pay

4.2.1 Company A

According to interviewee 1 & 2, if the consumers have the choice between a cheaper, non-sustainable product and a more expensive, non-sustainable one, the customer will most often choose the cheaper one. As interviewee 2 states:

"If you get the question, you usually say that you would pay more for a sustainable product. But when it comes to the crunch, that is not always the case." - Head of Sustainability.

The lack of willingness to pay proved to be a significant barrier and was identified across all conducted interviews and was prevalent both for consumers and companies. As sustainability is "part of their DNA" for company A, this issue targets consumers only. Sustainability as an incorporated strategy facilitates the ability to adopt sustainable solutions, including the increase in willingness to pay for sustainable materials. Consumers for company A are:

"...very educated when it comes to the matter of sustainability and prefer sustainable products. But that does not mean they are always willing to pay for it." - Head of Sustainability.

The lack of information about the impact of transportation is leading to many customers overusing features such as free transportation and returns. With the increase in e-commerce, interview 2 says that transportation's climate impact has risen to "11% of the total greenhouse gas emissions on a product's life cycle". The consequence of this overuse of transportation leads to increased resources used, time spent, increased cost and, overall, a higher climate impact. As interviewee 2 says, "... we have to work on educating our customers in what the consequences are".

The consequences of this lack of awareness lead to several issues within Company A. First of all, customers unaware of the need for sustainability will have difficulties changing their habits. As previously stated, these habits usually involve buying conventional cheaper

products instead of more sustainable, but more expensive, products. Furthermore, the demand for sustainable products becomes lower and therefore also impacts the environment.