i

Cookbook for Open

Innovation Platforms:

Designing a Sustainable

Future

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Global Management AUTHOR: Eva Medvecová & Alina Karola Neuer TUTOR: Duncan Levinsohn

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Cookbook for Open Innovation Platforms: Designing a Sustainable Future Authors: E. Medvecová and A.K. Neuer

Tutor: Duncan Levinsohn Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: open innovation, open innovation platforms, collaborative networks, sustainability

Abstract

Background: Open innovation platforms are a tool to solve sustainability challenges through innovation. These platforms facilitate the collaboration among diverse stakeholders, which is challenging but necessary to solve complex sustainability challenges. However, there is little research on how to design open innovation platforms to support collaboration and feedback from platform members is needed to understand their viewpoints.

Purpose: The study aims to understand the perceived benefits and challenges of participants from sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms. Based on this, the study intends to provide guidance for designing these platforms to increase the benefits for its participants.

Method: To understand the different viewpoints better, a qualitative research design in the form of a case study was chosen. Data was collected from interviews with participants from the open innovation platform Climate-KIC and analysed with the help of the Framework method.

Conclusion: The results emphasise that open innovation platforms must support their participants throughout the whole open innovation process. Special attention must be paid to the diversity of the participants that require different support from the platform based on their maturity level.

iii

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all those who contributed to our thesis and supported us during this process. It was an amazing learning experience that enriched our personal and professional lives, allowed us to meet interesting people, and led us to enrich our knowledge through authors and topics that we are passionate about.

We would especially like to express our gratitude towards our thesis supervisor Duncan Levinsohn, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Sustainable Business, Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), for his continued support and guidance throughout the whole process, his insightful feedback, and his ability to make us reflect on our work and improve it. Besides, we want to thank the participants of our seminar group for their valuable comments and feedback, which enabled us to continuously refine our work.

We would also like to thank our research respondents for devoting their time and entrusting us with sharing their experiences and perspectives. Especially, our gratitude belongs to EIT Climate-KIC that let us explore their organisation and provided us with priceless insights. Finally, a special thanks for the continued support and encouragement goes to our families and friends.

Thankfully,

iv

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research Problem ... 3

1.2 Research purpose and question ... 4

1.3 Delimitations ... 4

2 Literature Review... 6

2.1 Open innovation and open innovation platforms ... 6

2.1.1 Open innovation processes ... 7

2.1.2 Motivations for open innovation ... 8

2.1.3 Barriers to open innovation ... 9

2.1.4 Open innovation stakeholders ... 10

2.1.5 Open innovation platforms ... 12

2.2 Collaborative networks ... 15

2.2.1 Prerequisites... 16

2.2.2 Operating a collaborative network ... 17

2.2.3 Governance of collaborative networks ... 19

2.2.4 Benefits of collaborative networks ... 20

2.3 Guiding principles for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms ... 21

2.3.1 Purpose/goals (What) ... 22

2.3.2 Stakeholders (Who) ... 23

2.3.3 Processes (How) ... 23

2.3.4 Motivation (Why) ... 25

2.3.5 Governance (management, control, incentives) ... 25

3 Methodology ... 26 3.1 Research philosophy ... 26 3.2 Research approach ... 27 3.3 Sampling ... 28 3.4 Data collection ... 31 3.5 Data analysis... 32 3.6 Research ethics ... 34 3.7 Research quality... 35 4 Findings ... 37 4.1 Climate-KIC ... 37 4.2 Problem owners ... 39 4.2.1 Benefits ... 40

v 4.2.2 Challenges ... 41 4.3 Problem solvers ... 44 4.3.1 Benefits ... 44 4.3.2 Challenges ... 45 4.4 Jury ... 48 4.4.1 Benefits ... 48 4.4.2 Challenges ... 49 4.5 Platform managers ... 50 4.5.1 Benefits ... 50 4.5.2 Challenges ... 51 5 Analysis ... 54 5.1 Purpose/goals (What) ... 54 5.2 Stakeholders (Who) ... 56 5.3 Processes (How) ... 58 5.3.1 Obtaining ... 58 5.3.2 Integrating ... 60 5.3.3 Commercialising ... 62 5.3.4 Interaction ... 64 5.4 Motivation (Why)... 65 5.5 Governance ... 67

5.6 Model for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms ... 70

6 Conclusion ... 73 6.1 Theoretical implications ... 74 6.2 Managerial implications ... 75 6.3 Limitations... 76 6.4 Future research ... 77 7 Reference list ... 79 8 Appendix ... 89

vi

Figures

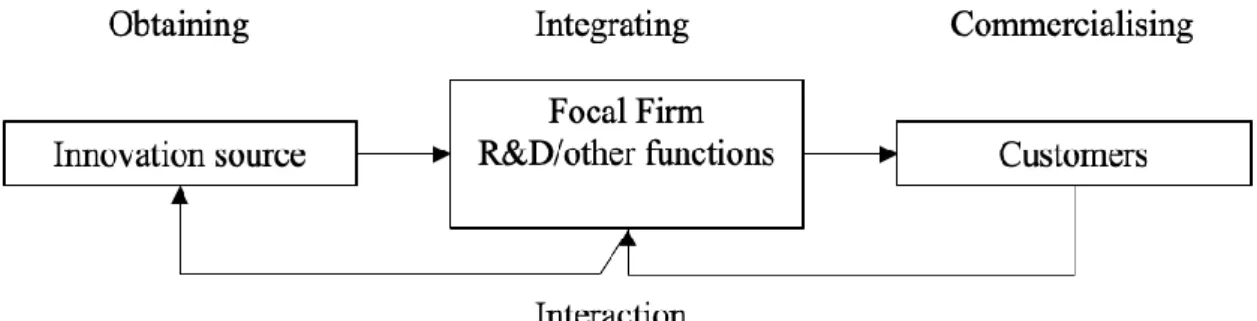

Figure 1 Phases of open innovation (West & Bogers, 2014) ... 8

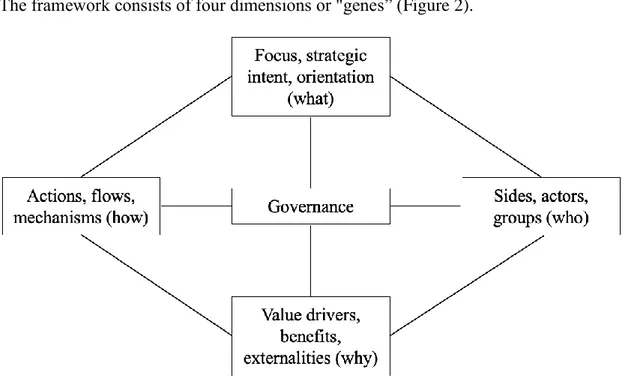

Figure 2 Conceptual framework of a multisided OIP for sustainable development (Elia et al., 2020) ... 14

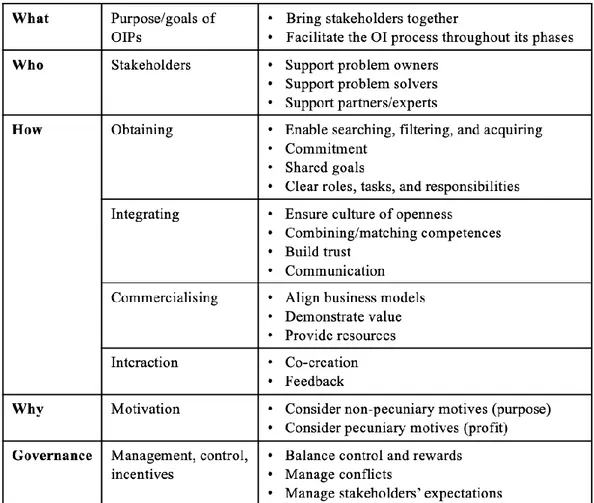

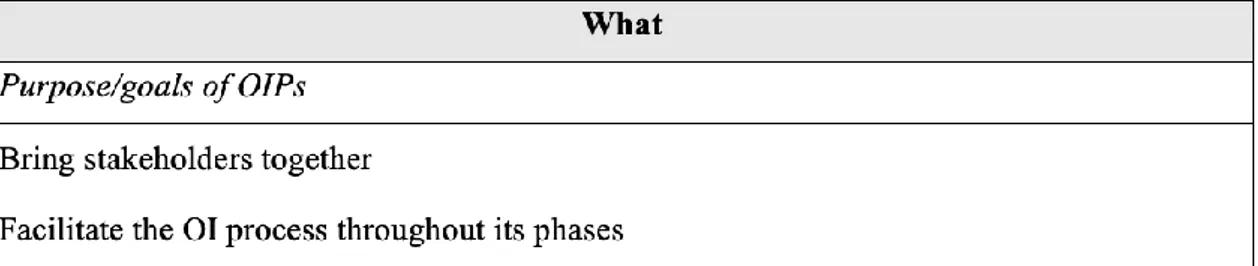

Figure 3 Guiding principles for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms ... 22

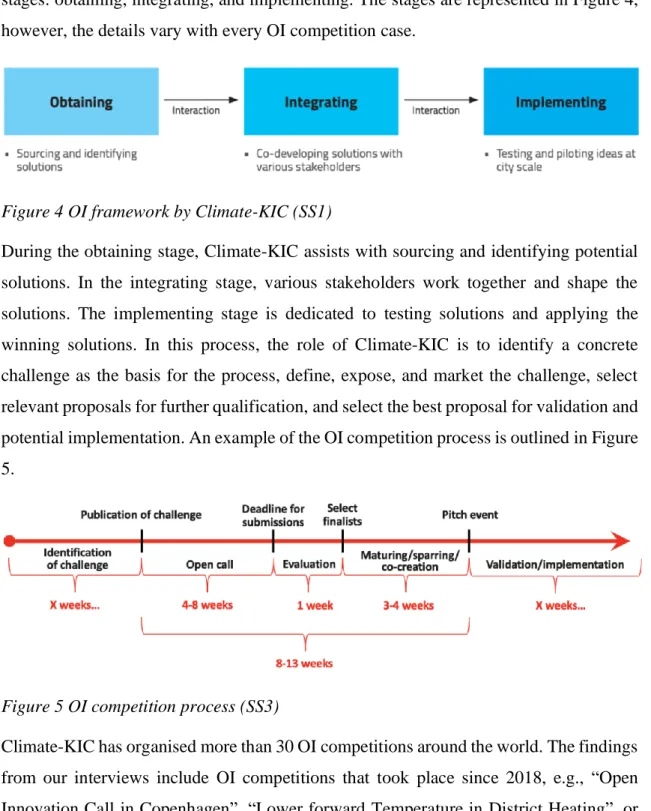

Figure 4 OI framework by Climate-KIC (SS1) ... 38

Figure 5 OI competition process (SS3) ... 38

Figure 6 Revised guiding principles for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms .. 69

Figure 7 Model for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms ... 70

Tables

Table 1 Overview interview partners ... 30Table 2 Overview secondary data sources ... 31

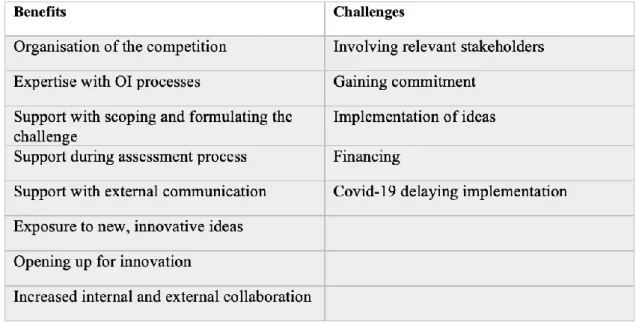

Table 3 Benefits and challenges for problem owners ... 43

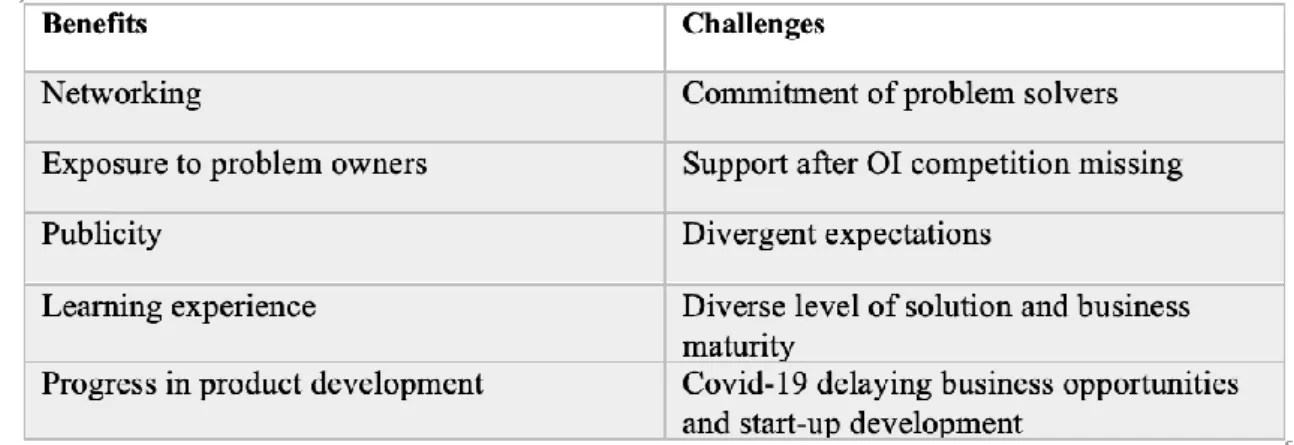

Table 4 Benefits and challenges for problem solvers ... 48

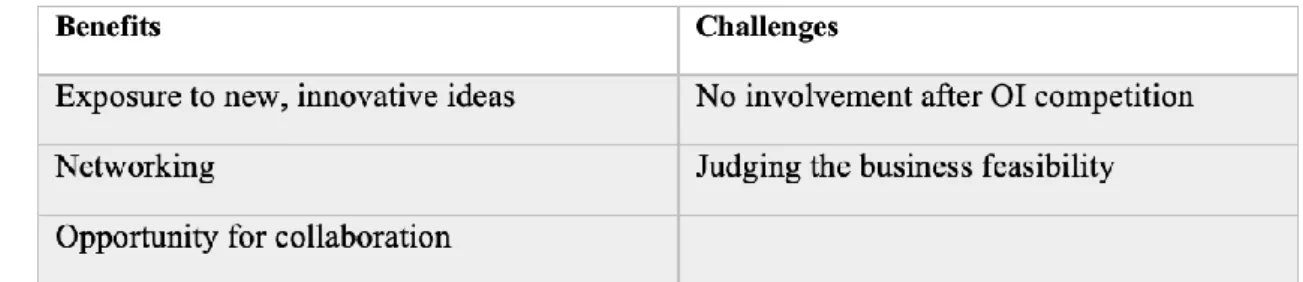

Table 5 Benefits and challenges for jury members ... 49

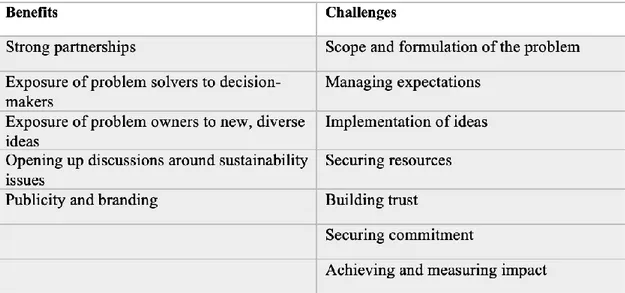

Table 6 Benefits and challenges for platform managers ... 53

Table 7 Guiding principles for what-dimension ... 56

Table 8 Guiding principles for who-dimension ... 57

Table 9 Guiding principles for how-dimension – obtaining ... 60

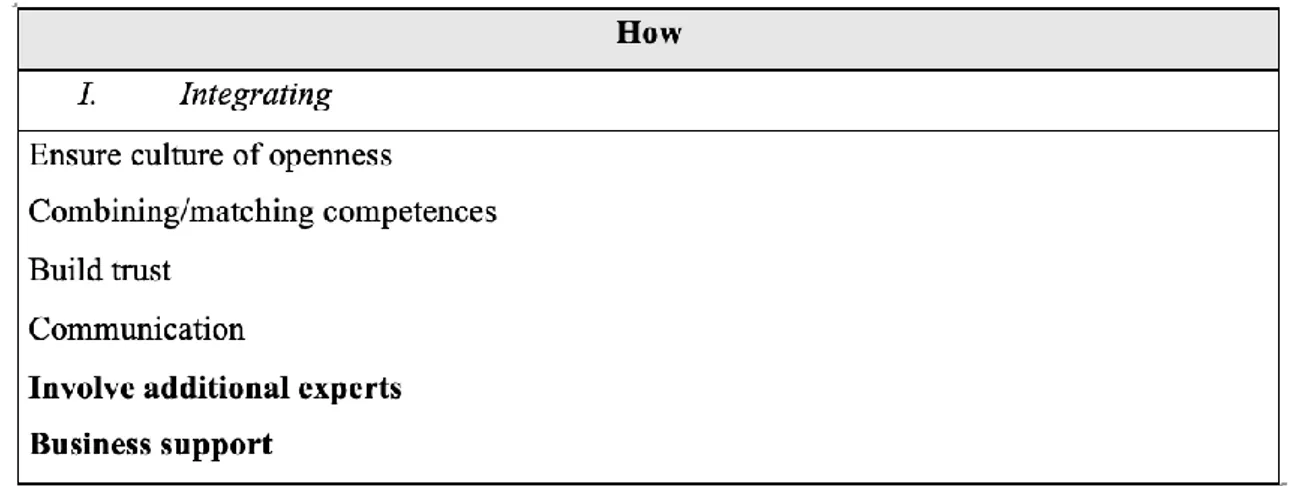

Table 10 Guiding principles for how-dimension – integrating ... 62

Table 11 Guiding principles for how-dimension – commercialising ... 64

Table 12 Guiding principles for how-dimension – interaction ... 65

Table 13 Guiding principles for why-dimension ... 67

Table 14 Guiding principles for governance-dimension ... 69

Appendix

Appendix 1 References for secondary data ... 89Appendix 2 Dates and duration of interviews ... 90

Appendix 3 Interview guide platform managers ... 92

Appendix 4 Interview guide problem owners ... 93

Appendix 5 Interview guide problem solvers ... 95

Appendix 6 Interview guide jury members ... 96

Appendix 7 Examples coding ... 97

Appendix 8 GDPR consent form interviews ... 106

1

1 Introduction

The state of the planet is broken. Dear friends, humanity is waging war on nature. This is suicidal. Nature always strikes back, and it is already doing so with growing force and fury. […] Human activities are at the root of our descent toward chaos. But that means human action can help to solve it. Making peace with nature is the defining task of the 21st century. It must be the top, top priority for everyone, everywhere.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres at the World Leaders Forum, December 2020 (United Nations, n.d.-b) Even though these concerns about the negative effects of human-induced climate change on nature have been raised for many years, the world has so far failed to act. Global greenhouse gas emissions and the planet’s temperature have risen compared to pre-industrial times (Olivier & Peters, 2020; Ritchie & Roser, 2020) and the economy has a major impact on this development (Ge & Friedrich, 2020). In 2015, the United Nations have established 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) as a call for action for all member states to support initiatives regarding sustainable development (United Nations, n.d.-a). In recent years, also governments have increased their pressure on companies to become more environmentally sustainable, e.g., by linking funds to a green transition (European Council, 2021). Also, the general public is demanding more sustainable behaviour through targeted policies according to the Peoples' Climate Vote 2021 (United Nations Development Programme, 2021).

However, sustainability is not only a threat to companies. Environmentally-friendly products can open up opportunities for companies such as the creation of new product categories, new markets, or the development of new technologies (Dangelico et al., 2013). This raises the question, why companies and organisations have been failing to find solutions although the threat is severe and benefits can be enormous?

One of the main reasons is that sustainability-related issues are considerably complex, often identified as Wicked Problems (WPs) (Newman-Storen, 2014; Rittel & Webber, 1973). WPs are characterized by social complexity and even experts often disagree about their exact nature, causes, and the best way to tackle them (Newman-Storen, 2014). Since WPs concern different groups of people holding different values, finding solutions is

2

complicated. Often, problem-solution for one is problem-generation for another and there is no universal truth about who is right and who should have its needs fulfilled (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Dealing with WPs requires diverse perspectives and trans-disciplinary approaches. It requires looking at the whole system, not just an individual, to find new ways of doing things (Grint, 2008). Collaboration is often mentioned as a way of dealing with WPs. It has been defined as a “process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited version of what is possible” (Fobbe, 2020). Bogers et al. (2020) claim that addressing sustainability challenges requires a great deal of collaboration, imagination, and dedication. George et al. (2016) refer to sustainability problems, such as climate change as, “super-wicked” problems or grand challenges which can only be solved through coordinated and collaborative work. De la Vega Hernández & Barcellos de Paula (2020) demonstrate an increased presence and convergence of the terms innovation and sustainability in academia. They argue that combining innovation and sustainability will be important to solve the great challenge of the society of simultaneously achieving competitiveness and respecting the environment.

A form of collaboration that can help to tackle WPs such as sustainability problems is open innovation. Open innovation (OI) refers to the collaboration between companies, institutions, or individuals to develop innovative products and services (Chesbrough, 2003). It is based on the idea that companies cannot rely only on their own research but can benefit from sharing their knowledge and innovating with partners. One way to foster OI is to implement an open innovation platform (OIP) (Adamczyk et al., 2012; Schlagwein & Bjorn-Andersen, 2014). In most cases, a platform is used to define how to organise interactions related to product development or other innovation with external partners (Kahl, 2011; Thomas et al., 2014). A platform defines the modes of cooperation that usually open the process for new actors and consider new forms of value creation. These include technological product platforms (e.g., iPhone), value chain platforms (e.g., the car industry), and industrial platforms (e.g., technologies) or a platform that has been used to describe internet-based business models as digital platforms (e.g., Facebook and Uber) on which value creation is highly dependent on the ability to attract users or developers to use the platform (Hagiu, 2014).

3

OIPs depend on the successful collaboration between the participating parties. Since collaboration is a process of shared creation (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006), the collaborating organisations must be linked and connected closely (Head, 2008). To connect with diverse organisations or people to reach common or compatible goals, organisations can get involved in collaborative networks (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006). Research on collaborative networks (CNs) has concentrated on how to design and manage these collaborations and on analysing their outcomes (Appio et al., 2017). Since OIPs are a form of CNs, insights from this research can be valuable for designing OIPs.

1.1 Research Problem

OI can bring several benefits and opportunities. Organisations might be able to develop products that they would not be able to create on their own, and it is often faster and cheaper to look outside for the technology than to develop it in-house (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). However, Gassman et al. (2010) argue that the process by which companies manage OI is still more trial and error than a professionally managed process. According to their study, a guide or an integrated framework that could help managers to apply OI is missing in the literature. Yet, managing OI activities is going to be crucial in the future, and therefore we need to know more about the failures and challenges of OI (Hossain, 2013).

The idea of collaboration is what connects OI with sustainability and has been recognized as a key element to solve complex sustainability problems (Bogers et al., 2020). However, new forms of collaboration can be challenging to form and manage. Partnerships often collapse for different reasons, such as incorrect allocation of costs and benefits or distrust between collaboration members (Le Ber & Branzei, 2010). Understanding and efficiently managing the different CN dimensions that emerge between the different organisations that engage in OI is a critical factor to better develop efficient collaborations (Nunes & Abreu, 2020). Therefore, adding insights from CN theory to OI theory can be valuable. According to Nambisan et al. (2018), future research that fully examines the varied roles in both OI and platform contexts and their implications on collaboration capabilities would be invaluable. Moreover, Elia et al. (2020) claim that little research has been conducted on how OIPs can better design collaboration flows. Moreover, the authors add

4

that feedback from such platform community members may provide useful insights into how to design collaborations more effectively to achieve better performance of sustainability solutions. Therefore, to develop principles for a better design of OIPs, applying research from CNs can be valuable.

For these reasons, the development of a theory for OIPs that combines sustainability, OI, and CNs is needed.

1.2 Research purpose and question

Following the identified research gap and the relevance of the topic, the purpose of this thesis is to extend research on OIPs by applying theory from OI and CNs on sustainability-oriented OIPs. By concentrating specifically on platforms that foster sustainability, we want to contribute to research on sustainability and OIPs by exploring the opportunities and challenges organisations experience when adopting an OI approach for sustainability by participating in an OIP. The practical aim of the study is to provide guidance to OIPs that support sustainability-oriented innovation. We want to give recommendations on how to design the platform to maximize the benefit for the participating organisations.

Following the aim of our research, our research questions (RQ) are as follows:

RQ 1. What benefits and challenges do participants of sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms experience?

RQ 2. How can platforms be designed to maximize the benefit for their participants?

1.3 Delimitations

For this study, we define sustainability-oriented OIPs as web-based networks of diverse organisations (private, public, or research institutes) that collaborate in an organised form intending to achieve sustainable innovation. The platform can be managed by any kind of organisation. The role of the platform is to foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing among members, provide tools, training, and resources as well as share best practices. We define sustainability as aiming to meet the “[…] needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987). We consider all three pillars of sustainability, which encompass protecting the

5

environment, maintaining economic growth and development, and facilitating equity (Portney, 2015).

6

2 Literature Review

The literature review introduces the topics of open innovation (OI), open innovation platforms (OIPs), and collaborative networks (CNs). We then present the theoretical framework that guides our research, which was enriched with OI and CN theory.

2.1 Open innovation and open innovation platforms

OI has emerged as an important concept in academia, industrial practice, and the public policy domain (Bogers et al., 2018). It has become one of the hottest topics in innovation management, but also in a wide range of other disciplines such as psychology or cultural anthropology (Huizingh, 2011). OI was originally introduced by Henry Chesbrough (2003) who defined OI as:

“A paradigm that assumes that firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to markets, as the firms look to advance their technology” (Chesbrough, 2003, p. 24).

The OI paradigm is explained by Chesbrough as the antithesis of the traditional vertical integration model in which internal innovation activities lead to internally developed products and services, which Chesbrough (2012) describes as a closed innovation model. On the contrary, OI aims to integrate innovations from outside the firm (outside-in) and vice versa (inside-out), which can bring several benefits such as technological advancements, accelerating innovation, or ensuring competitive advantage (Chesbrough, 2012; Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006; Chesbrough, 2003).

Over the decades, OI acquired several meanings. Some of the recent nuances are open source innovation, user innovation, crowdsourcing, community-based innovation, or networking (Rauter et al., 2017). According to Rauter et al. (2017), these concepts are falsely overlapping with OI in literature. Both, Rauter et al. (2017) and Chesbrough (2012) stress the importance to differentiate OI from concepts such as open-source innovation, where the users are expected to share their knowledge for free, which is not necessarily the case in OI. On the other hand, von Hippel (2005) argues that the benefits of OI should be used and shared freely by its users and communities. In our work, we will refer to OI based on the definition of Chesbrough (2003), as it offers the original and universal explanation of OI. Nonetheless, we support the view of Trott and Hartmann (2009b) who suggests that the basic premise of OI is that companies should open their

7

innovation process. We agree with the authors that OI is a work in progress rather than a radical invention and that companies should be open and welcome future variations of OI (Trott & Hartmann, 2009).

In recent years, several authors have connected OI to sustainability (Bogers et al., 2020; Elia et al., 2020; Payan-Sanchez et al., 2021; Rauter et al., 2017). Sustainability appeared in almost 80% of the OI articles published from 2015 to 2019, thus becoming one of the most relevant themes in OI research (Payan-Sanchez et al., 2021). OI can be an effective way to approach sustainability challenges and the combination of these two topics has the potential to become the domain ‘Sustainable Open Innovation’ (SOI) (Bogers et al., 2020). Chesbrough (2012) suggests that the future of OI will be more extensive, more collaborative, and will engage a wider variety of participants. Designing and managing innovation communities is therefore going to become increasingly important to the future of OI (Chesbrough, 2012).

2.1.1 Open innovation processes

There are two main types of OI processes: outside-in (inbound) and inside-out (outbound) (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). Outside-in processes aim to integrate external ideas and solutions into the company’s internal innovation processes, while inside-out processes allow external parties to use internally formed know-how (Chesbrough, 2012). For more in-depth understanding, Dahlander and Gann (2010) describe two inbound processes, sourcing and acquiring, and two outbound processes, revealing and selling. Sourcing implies getting external ideas and knowledge from suppliers, customers, competitors, or other stakeholders, which is connected to indirect, non-monetary benefits. Acquiring means acquiring inventions to the innovative process through informal and formal relationships, usually for profits. Revealing is explained as revealing internal resources to the external benefits for indirect or non-monetary benefits. Selling refers to out-licensing or selling products to the market. The coupled process was introduced as a third concept that combines the outside-in and inside-out processes by working in alliances with partners (Gassmann & Enkel, 2004). However, Chaurasia et al. (2020) argue that OI for sustainability needs a more elaborate perspective besides the three traditional types of processes that allows different co-creative partnerships, interactions, and the integration of a wider network. Similarly, West and Bogers (2014) stress the importance of including the aspect of interaction in OI processes. They suggest a four-phase model in which a

8

traditional linear process consisting of obtaining, integrating, and commercialising is complemented with the fourth phase of interaction (Figure 1). This includes feedback loops, co-creation, and integration with networks and communities. The obtaining phase consists of searching, enabling, filtering, and acquiring with specific mechanisms for each step. The integrating phase elaborates on absorptive capacity, culture, incentives to cooperate, and competencies that need to be managed properly. Commercialising emphasises how external innovations create value and how this value is captured. In this phase, the value creation potential of external sources is important and business models need to be aligned. Overall, more focus is needed on the motivation of the collaborating partners, especially where the collaboration is driven by non-pecuniary motivations (West & Bogers, 2014).

Figure 1 Phases of open innovation (West & Bogers, 2014)

2.1.2 Motivations for open innovation

When it comes to motivation and incentives for OI, many authors refer to financial mechanisms (profits) called pecuniary mechanisms, and non-financial mechanisms (purpose) called non-pecuniary mechanisms. In OI in a sustainability context, purpose represents the initial motivating factor, however, in the next phases of OI, profits must be fulfilled, especially within the private sector. This pathway of purpose to profits is a success factor of sustainability-oriented OI (Bogers et al., 2020).

While OI in the private sector usually has new product development as a goal, OI in the public sector usually focuses on creating public value and improving services. Other motives driving OI in the public sector are reducing expenses or letting citizens participate in decision-making processes (van Genuchten et al., 2019). Moreover, the role and motives of big corporations and SMEs are different. While the motives of corporations are inventions, the main motive for SMEs is commercialisation (van de Vrande et al.,

9

2009). Managing collaborations might be difficult when participants are motivated by different incentives (Wallin & von Krogh, 2010). Often, employees get involved in OI activities for little or no rewards (Nakagaki et al., 2012), or platform members participate as volunteers (Wallin & von Krogh, 2010). Therefore, there is a need to introduce a reward system that promotes the efforts of employees or other participants (Saebi & Foss, 2015).

Research has identified several advantages of applying OI, such as leveraging external knowledge inputs to accelerate internal innovations and expanding the markets for applying new innovation (Saebi & Foss, 2015). Chesbrough (2003) explains that companies with a closed innovation approach might miss opportunities because many fall outside the organisation's business or need to be combined with external technologies to unlock their potential. When companies look for external technologies, they minimize risks by investing in technology that is already proven in other places (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). To tackle wicked problems, not only technological innovation is needed, but mostly a societal change, in which OI can be a helpful strategy (Saebi & Foss, 2015). One of the greatest benefits of effectively managing OI is the positive impact on economic, social, and environmental sustainability (Rauter et al., 2017).

2.1.3 Barriers to open innovation

The managerial and organisational barriers to OI are very diverse. Chesbrough and Crowther (2006) refer to the Not Invented Here (NIH) syndrome when individuals and organisations tend to avoid things created externally. Resistance to OI can stem from the belief that seeking solutions outside the company is an admission of failure, which is why a switch of mindset is crucial (Nakagaki et al., 2012).

OI in SME’s is often hindered by a lack of resources, due to the size and boundaries of their organisation, therefore they need to rely on their network. Collaborating with bigger companies can help SMEs to overcome issues with their main challenge of commercialisation. Also, the corporate organisation and culture of SMEs are barriers to OI when SMEs start to collaborate with external partners since they manage OI differently. This leads to problems concerning the division of responsibility and tasks, the balance between innovation and day-to-day tasks, and communication problems between and within organisations (van de Vrande et al., 2009).

10

Several authors also suggest that we have a limited understanding of the costs and failures of openness. Openness can negatively affect innovative performance because of over-search and since the innovation over-search can be time-consuming, expensive, and laborious. Therefore, the enthusiasm for openness needs to be tempered by an understanding of its costs (Saebi & Foss, 2015). According to Laursen and Salter (2006), the returns from OI can decrease as the costs of openness exceed the benefits. They suggest that search efforts should not be spread across too many channels and that too many innovations can also be a challenge in OI processes (West & Bogers, 2014). In addition, since organisations might hide failures of OI, the full picture of the disadvantages of OI might be missing (West & Bogers, 2014).

Moreover, the call for OI involves maintaining an internal commitment over time to realize the benefits of adopting the concept. To address this, companies must provide top management support and funding at the beginning of the initiative, create OI champions to manage integration processes, and review internal processes, metrics, and incentives to trigger adoption (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). It is necessary to find individual leaders who are willing to explore the approaches of OI within their departments. Second, it is necessary to identify individuals with specific problems who are prepared to try new approaches to their solution (Nakagaki et al., 2012).

Another difficulty in managing OI is aligning rewards with efforts. Organisations must identify individuals with a passion for OI who are willing to support OI activities. For those who choose to engage in OI it creates extra work for them and their teams on top of their daily tasks. There is no formal reward or recognition for people running OI projects unless it is linked to tangible progress in the project. In principle, there is often no convincing enough reason to try a new approach to solving a problem (Nakagaki et al., 2012).

2.1.4 Open innovation stakeholders

Organisations enter OI processes with different roles and OI activities can be initiated and managed by different players. While OI was first understood and implemented as a collaboration between two organisations, today, the concept is often used to orchestrate a significant number of players across multiple roles and industries (Chesbrough, 2012). There are different roles and approaches of the private and public sector engaging in

11

sustainability-oriented OI. While the private sector aims at tackling sustainability challenges through product innovation, the public sector aims at creating an environment for collaboration and bringing different actors together (van Genuchten et al., 2019). In the private sector, companies involved in OI are increasingly influenced by external stakeholders who transfer their ideas and knowledge into the companies’ internal innovation process (Payan-Sanchez et al., 2021). For successful sustainability-oriented OI initiatives, active participation, interaction, and collaboration with several stakeholders are important (Chaurasia et al., 2020). OI has been criticized for concentrating on for-profit actors while ignoring non-profit, even though both are crucial for achieving innovation in sustainability (Holmes & Smart, 2009).

Yet, in recent years, the importance of the public sector in sustainability-oriented OI initiatives has increased (Payan-Sanchez et al., 2021). Public institutions and organisations increasingly initiate collaborative innovation by co-creating projects aiming to achieve sustainability through different networks and platforms (Payan-Sanchez et al., 2021; Rupo et al., 2018). Municipalities play a crucial role in coordinating OI activities aiming to find solutions to their sustainability challenges (van Genuchten et al., 2019). Their role can vary from facilitating OI practices, building infrastructure for OI, or taking part in the co-creative processes. OI activities can be also initiated by regions (van Genuchten et al., 2019), NGOs (Holmes & Smart, 2009), or governments (Chaurasia et al., 2020), while the public can be invited to participate in OI challenges and propose solutions (van Genuchten et al., 2019). Additionally, public agencies can help to support initiatives and have a better reach than private actors. OI can, therefore, help reaching public organisations, which is crucial for pursuing sustainable OI (Bogers, 2020).

To succeed with the OI projects across different organisations, there needs to be a win-win for all collaborators, which is only possible if the business model, costs, and risks of each party are considered (Bogers et al., 2020). The differences between collaborating partners in their organisational structure, business models, culture, or bureaucracy can hinder OI. For overcoming these challenges, ensuring ‘proximity’ between the collaborating partners is needed, what can be done by providing sufficient knowledge about their culture, organisations, and bureaucratic restrictions (Boschma, 2005). Yun (2019) suggests building an OI culture to overcome existing cultural barriers. For OI, a culture that is open to something new to enhance and maintain creativity is needed

12

(Gassmann, 2010). In sustainability-oriented OI, Nordic business leaders fulfil a prerequisite for effective OI as they tend to have good relationships with the government and cooperate with research institutions and universities (Bogers et al., 2020).

In a sustainability context, OI needs to be orchestrated over a longer period and, therefore, the willingness of all stakeholders to participate is crucial, as it provides an important early validation. Demonstrating “early wins” is crucial to continue with OI efforts (Bogers et al., 2020). A series of small wins should also be presented to the management to demonstrate the value of OI for receiving a green light to continue. Therefore, the value of OI activities needs to be measured and quantified (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006; Nakagaki et al., 2012). Rauter et al. (2017) suggest that moving from having ad hoc processes to clearly defined OI practices, roles, and responsibilities can help to ensure the successful integration of OI.

To conclude, to successfully apply OI, important changes need to be made to business models, organisational culture and structure, and corporate governance across multiple collaborating parties (Bogers, 2020).

2.1.5 Open innovation platforms

Since establishing collaborations is time-consuming and challenging, some authors question whether organisations should do it by themselves. OI can also be managed through intermediaries who can organise the network and manage network members (Lee et al., 2010). In this context, Ojasalo and Tahtinen (2017) refer to an innovation intermediary or platform that is often used in public institutions like the EU, cities, or regions. They are mostly publicly funded and have a non-profit character, e.g., helping SMEs with administrative, financial, and other challenges when facing barriers due to lack of resources. The authors define innovation platforms as an approach to facilitate external actors to develop solutions to problems of platform owners. The main goal of innovation platforms is attracting, facilitating, and orchestrating other organisations’ innovation. It is, therefore, a tool for organising rather than a virtual or physical space (Ojasalo & Tahtinen, 2017). Their focus is to capture external knowledge and combine it with existing knowledge. They act as intermediaries helping and initiating collaborations and building networks (Eito-Brun, 2020).

13

Similarly to innovation platforms, OIPs have been described as a new way of co-creation spaces that facilitate innovation and enable the different actors to interact (Rho et al., 2020). These platforms play a key role in the innovation ecosystem by facilitating collaboration, diversity, and social sustainability (Aryan et al., 2021; Elia et al., 2020; Nambisan et al., 2018; Rho et al., 2020). Rho et al. (2020) define OIPs as an organisational model for the coordination of OI processes and Raunio et al. (2018) add that OIPs integrate different actors, both the producers and the users of innovation, for mutual value creation. According to Raunio et al. (2018), it is important to underline that OIPs facilitate innovations rather than introducing them. OIPs can work as web-based platforms where companies can publish innovation challenges and others can analyse and propose solutions (Eito-Brun, 2020). They can intermediate needed connection, match partners with challenges, or ‘problem owners’ to ‘problem solvers’ from all around the world (Rho et al., 2020). The digital aspect of OIPs, knowledge sharing, and their role as an intermediary for problem-solving, are the most common characteristics of OIPs highlighted in the literature. OIPs gain increasing importance as a place for value creation and capture (Nambisan et al., 2018). However, the value of shared knowledge is only created when participants cooperate with the platform (Zhang et al., 2020).

The value of OIPs lies in helping community members to propose ideas, express their needs, and help companies or other stakeholders to develop new, better, and more personalized services to satisfy them (Situmeang et al., 2019). Platform stakeholders are those that interact with the platform, such as citizens, companies, scientists, or policymakers. Roles for actors can be identified based on their knowledge and expertise to facilitate discussions and matchmaking (Elia et al., 2020). OIPs can help not only companies but also the stakeholders that are involved to develop networks where they can share ideas, exchange knowledge, or propose new challenges (Eito-Brun, 2020). OIPs have unleashed numerous opportunities for entrepreneurs in various industries (Nambisan et al., 2018) such as generating large amounts of solutions for problems, but identifying the best solutions can be expensive and time-consuming (Klein & Garcia, 2015). The main motives for users to contribute to platforms range from community citizenship to self‐reward, peer recognition, and reputation (Aryan et al., 2021).

14

Elia et al. (2020) have built the conceptual framework of a multisided OIP as a collaboration place for different actors to respond to sustainable development challenges. The framework consists of four dimensions or "genes” (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Conceptual framework of a multisided OIP for sustainable development (Elia et al., 2020)

The what-dimension concentrates on the vision and specialization of the platform. This facilitates discussions and actions and gives an understanding of the orientation of the platform. Platforms with a focus on transactions can function as a marketplace, others with a focus on innovation can support design and creation, or platforms can be a hybrid form of both (Elia et al., 2020).

The who-dimension includes all actors and stakeholders that affect or are affected by the platform in terms of its policies, goals, and actions. It further includes those that are interested in interacting with the platform. These can be e.g., citizens, companies, scientists, or policymakers. Roles for actors can be identified based on their knowledge and expertise to facilitate discussions through contribution policies and matchmaking algorithms (Elia et al., 2020).

The how-dimension describes all processes that are set up for coordinating and managing relations and knowledge flows between members. These processes should be designed to support the strategic focus of the platform and can include, e.g., aggregation mechanisms and matchmaking functions. In sustainability-oriented platforms, processes should align

15

the expertise, aspirations, and capabilities of sustainable development. Further, the stability of the platform can be ensured by monitoring members’ behaviour and using digital services effectively and purposefully (Elia et al., 2020).

The why-dimension includes the benefits for members to be involved in the platform and contribute to discussions and joint actions. These benefits can stem from the coordination of members and value increase through network effects such as resource optimization and matchmaking, efficiency-seeking, and cost reduction. In sustainability-oriented platforms, the feeling of reacting to sustainability issues and the ability to contribute to public discussions and shared solutions generation processes can make organisations want to join the platform (Elia et al., 2020).

The governance of platforms covers the set of explicit and implicit rules, which regulate the selection, participation, and interaction of members within the platform. It further comprises the quality assurance of provided services as well as financial, human resources, and conflict management within the platform (Elia et al., 2020).

To conclude, the idea of collaboration is what connects OI with sustainability, which calls for more coordinated and collaborative effort under the framework of OI (Aryan et al., 2021; Elia et al., 2020; Nambisan et al., 2018; Rho et al., 2020).

2.2 Collaborative networks

Collaborative networks (CNs) were first defined by Camarinha-Matos and Afsarmanesh (2006) as networks that connect a diverse set of entities. These can be e.g. individuals, firms, universities, or governments (Tidd et al., 2005). The entities collaborate to reach common or compatible goals by enhancing each other’s capabilities. For that, they share risks, resources, responsibilities, and rewards. The participating entities are mostly independent, geographically dispersed, and heterogeneous. The heterogeneity can stem from different corporate cultures, goals, operating environments, or social capital (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006). It is important to maintain a heterogeneous set of organisations to ensure the existence of different but dependent competencies that can be combined (Chituc et al., 2008). In contrary to other forms of working together, collaborating organisations must be linked and connected more closely. Collaboration requires them to go beyond their normal structures and create new roles and functions specifically aimed towards the collaboration (Head, 2008). Following the definition of

16

Camarinha-Matos and Afsarmanesh (2006), we define collaborative networks as networks connecting diverse participants to reach common or compatible goals.

CN theory concentrates on designing and managing collaborations (Appio et al., 2017). Coordinated collaboration is critical for sustainable action since it helps to go beyond the individual entities’ capabilities and vision to achieve effective and sustainable solutions (Borges et al., 2016). By creating concepts, methods and tools, CN theory promotes the commitment and interaction of multiple stakeholders to solve the complexity of sustainability issues. CN theory has, e.g., developed tools for knowledge sharing and coordination of heterogeneous organisations, or governance methods to manage trust in collaborations. By that, it helps to foster action towards sustainability (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2010).

2.2.1 Prerequisites

The success of CNs is dependent on several prerequisites, which affect the ability of organisations to form and get involved in the network (Appio et al., 2017). Firstly, processes that form and manage trust are crucial in CNs since the participants must rely on each other due to their interdependencies (Rampersad et al., 2010). According to Sanzo et al. (2015), trust in collaborations is composed of the three dimensions capability, honesty or integrity, and benevolence. Capability represents the belief that the collaborating partner has the required competence to add value to the collaboration. Honesty or integrity implies the belief that the partners will keep their promises and that they agree on and follow corresponding values. Lastly, benevolence includes the belief that the partners are concerned about each other’s welfare (Keast & Mandell, 2013). Prior conflicts between participating organisations or individuals, hidden or differing goals, a lack of information sharing, or the failure of partners to fulfil their commitments can be challenges for building trust (Linden, 2010). Furthermore, competitive orientation within the network can hinder trust. It derives from the challenge of organisations to remain autonomous while collaborating with partners. When partners have a lower level of trust, they act more self-orientated, independent, and risk-avoiding, which harms the effectiveness of collaborations (Austen, 2018). In contrast, Thorgren and Wincent (2011) claim that trust can cause rigidities due to the cognitive and relational closeness from sharing knowledge, developing routines and responsibility patterns, and being dependent

17

on each other’s resources. Even though trust can create rigidities, we still consider it a crucial factor for establishing successful collaborations in networks.

Further, shared values should be fostered through the set-up of processes. Shared values secure social cohesion, support transactions mechanism, and help understanding the collaborator’s behaviours (Abreu & Camarinha-Matos, 2008). Heterogeneous members often have different sets of values, which influence the member’s behaviour. Therefore, it is beneficial to ensure common or compatible values in these collaborations (Abreu et al., 2009). Especially cross-sectoral collaborations, which are needed for sustainability initiatives, are at risk to be negatively affected by the different values and purposes of the collaborators, which impedes knowledge sharing (Borges et al., 2016).

Moreover, structural mechanisms support the networking processes in CNs by fostering knowledge sharing (Appio et al., 2017). Spallek et al. (2008) highlight the importance of personal communication in networks as a critical source of information. Therefore, networks should support personal communication among collaborators and support less-connected members in the network through opportunities for group discussions. This fosters knowledge sharing and the development of trust among members.

2.2.2 Operating a collaborative network

Depending on their objectives, the influencing policies, the complexity of the problem, and the structure of stakeholders, CNs can have various forms and goals and can, therefore, require different management. CNs can, e.g., be described as bottom-up or top-down networks. Bottom-up networks are formed gradually by their participants while top-down networks are initiated and/or funded by government agencies that can have a significant influence on the dynamic of the network (Head, 2008). A CN needs particular management of capabilities, that is different from the management of organisations (Shahabi et al., 2020). The network structures should support the creation of incentives, ensure fairness, and make the contribution of the network members transparent (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006). Network management can support CNs by ensuring network stability, which is needed to build long-term relationships among network partners. These help the partners to develop consistent responses to stakeholders and secure efficient network management in the long run (Provan & Kenis, 2008). However, too rigid structures can impede collaboration since they prevent the network

18

from reacting flexibly to changing environments. Thus, CNs must also ensure a high level of flexibility to improve the effectiveness of the network (Willem & Lucidarme, 2014). Milward and Provan (2006) identified several areas of management tasks in CNs. Firstly, networks lack the organisational structures for accountability and authority, which makes it difficult for members to understand the benefits gained from the collaboration (Mischen, 2015). Therefore, incentives for collaborations, e.g., more access to some assets, and punishments for selfish or free-rider behaviours, e.g., higher cost for the access to the network’s services, can be put in place (Abreu & Camarinha-Matos, 2008). Secondly, the legitimacy of the network must be built and maintained (Milward & Provan, 2006). On the one side, internal legitimacy supports the collaboration of network members, that can otherwise be competitors, by showing the benefits of the collaboration (Provan & Kenis, 2008). Network managers can assist members with their demand articulation, e.g., identifying the problem, articulating ideas, and transferring them into needs. Additionally, by noting potential connections between network members due to complementary assets such as knowledge or funding, network managers can connect members to foster collaboration. This is especially helpful for different types of members that have different interests and cultural backgrounds (Batterink et al., 2010). On the other side, external legitimacy attracts customers, secures funding, and helps in dealing with governments. Since the internal legitimacy needs of members can deviate from the external legitimacy needs of the network, conflicts between those two dimensions must be managed (Provan & Kenis, 2008).

Lastly, networks must ensure the commitment of their members. To exploit the benefits of CNs, the participating entities must be committed to the overall change process and to making major changes in the organisation’s operations (Keast & Mandell, 2013). While many organisations collaborate with several stakeholders, most of them do not go far enough in changing their organisational practices (Fobbe, 2020). A high degree of commitment fosters knowledge sharing in collaborations, leading to higher innovation capabilities (Sanzo et al., 2015). To secure the participant’s commitment, networks should provide information about the function of the network and its contribution to the goals of its stakeholders (Milward & Provan, 2006). Helping the participants to understand how other participants add value to the collaboration increases respect among participants (Keast & Mandell, 2013) and helps to ensure a common understanding of the

19

network’s value. It thereby facilitates the development of shared goals (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006) and thus supports network stability (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006). 2.2.3 Governance of collaborative networks

CNs need to set up and continuously develop governance structures (Milward & Provan, 2006). Several authors concentrate on the role of a network orchestrator for governing the CN. A network orchestrator is typically a large and dominant firm, e.g. the hub firm, within the network (Batterink et al., 2010). Shahabi et al. (2020) propose that the network orchestrator is mainly responsible for internal and external communication, management of resources, conflict management, the fair distribution of network output, and the recruitment of new members.

CNs must attract participants that can contribute to the success of the network. This process involves the identification of selection criteria and the strategic decision-making about partners (Appio et al., 2017). Thereby, the size, diversity, autonomy, and density of connections in the network can be influenced and, thus, the network’s status (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006). For sustainability-oriented collaborations, involving multiple stakeholders is crucial for solving the challenges (Fobbe, 2020). However, many of the multiple stakeholder-collaborations fail due to the heterogeneity of the partners’ values, missions, and purposes that impede knowledge sharing (Borges et al., 2016). For example, CNs with public actors often have an increased need for formal documentation with regards to rules, protocols, responsibilities, and accountabilities (Head, 2008). The orchestrator must, therefore, be able to bring members together, help to overcome cultural differences, and make members feel comfortable to share ideas, resources, and power (Keast & Mandell, 2013). To make the goal of the network clear to everyone, the degree of co-dependency and common interests should be communicated to potential network members (Shahabi et al., 2020).

It is also the network orchestrator’s responsibility to manage relationships and foster socialisation among members (Shahabi et al., 2020). Socialisation can be fostered through formal and informal communication channels and promotes knowledge mobility within the network (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006). Further, the network orchestrator should manage the relationships by setting up mechanisms for conflict resolution and acting as a neutral mediator between the members (Milward & Provan, 2006). The heterogeneity of the

20

organisations can generate conflicts between the members of the network. Decisions could be advantageous for one member while being disadvantageous for another (Andres & Poler, 2020). Also, industry and research institutes are often very different in terms of their mindsets, expectations, and timeframes. Conflicts often occur as a result of hidden agendas, different expectations, or a lack of motivation (Batterink et al., 2010). Therefore, mechanisms to overcome conflicts are critical for the circulation of knowledge within the network (Ingles Yuba & Puig Barata, 2015). Having transparent processes and being open to all members are important factors for solving conflicts and thus creating stability in the network (Batterink et al., 2010). Knowledge mobility can further be supported by engaging in the formation of trust and collaboration (Shahabi et al., 2020).

However, Barrutia and Echebarria (2020) argue that the role of network orchestrators has been overrated. In a study with public managers involved in a sustainability network, they identified the internal motivation of the organisations and the managers’ identification with the network as a main influence on the network. Therefore, the role of network orchestrators would rather be to identify what members have in common and build a shared identity based on these similarities. This can be achieved by defining prototypical projects while letting members co-create the precise content. It also calls for a more careful selection of new partners that fit in based on their internal motivations. Due to the large agreement among researchers that network orchestrators have an influential role, we follow this opinion while keeping in mind that the individuals working in CNs have a strong influence on its dynamics, which needs to be considered by network orchestrators. 2.2.4 Benefits of collaborative networks

CNs help organisations to deal with complex problems that they could have not solved on their own (Keast & Mandell, 2013). By participating in CNs, companies can share risks and join complementary skills, resources, and technologies. They are confronted with new ideas and practices and can create synergies. This allows them to access new knowledge, markets, and resources while concentrating on their company’s core competencies and staying highly agile. CNs thereby foster innovation and the creation of new value (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006). Besides, members of the network can take part in valuable social exchanges that can for example improve their status and help them gain legitimacy (Barrutia & Echebarria, 2020). All in all, the goal of CNs is to

21

maximize a component of the entity’s value system, for example, economic benefit or social recognition (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh, 2006).

As collaboration has been identified as a key element in solving complex sustainability challenges, CNs have received an increasingly important role (Fobbe, 2020). CNs can support sustainability efforts in diverse settings such as sustainable agriculture, transportation systems, water management, or tourism (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2010). Despite challenges with divergent values and the commitment of partners, CNs can have a positive effect on sustainability endeavours. Zubeltzu-Jaka et al. (2018) claim that companies involved in CNs with relevant stakeholders such as research institutes and public agencies are more likely to engage in sustainability-oriented innovation. Further, Dangelico et al. (2013) found out that gaining external knowledge from CNs fostered the integration of environmental issues in product development. This so-called green product design had in return a positive effect on the companies’ performance due to the opening of new markets, product areas, and technologies.

The success of CNs is difficult to define and is influenced by the network’s structure of stakeholders and the context of policies in which the network is operating (Head, 2008). Appio et al. (2017) identified innovative outcomes, such as technological knowledge distance and profits from innovative products, and other factors such as cost reduction, prestige, and agility as the main components of CN success. In contrast, Head (2008) claims that the main elements of network success are outcomes and processes. While outcomes refer to the measurable benefits for stakeholders, processes refer to the quality and coherence of processes in the network that support the resolution of problems.

2.3 Guiding principles for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms

Based on theory from OI and CN, we have developed guiding principles for sustainability-oriented OIPs based on their dimensions. We used the five dimensions of the conceptual framework of Elia et al. (2020) as a basis since it helps to analyse the relevant structural dimensions of OIPs to identify the main sources of benefits and challenges. Further, it is a very recent and the only existing model that combines the sustainability aspect with OIPs. However, it does not provide a dynamic view of the collaboration processes within an OIP. Yet, it would be interesting to observe these processes at different stages. Therefore, we enrich the framework with the OI phases

22

model of West and Bogers (2014). We include the phases in the how-dimension, which is concerned with the actions, flows, and coordination mechanisms of OIPs, as these should be aligned with the OI processes of the platform participants. The model of West and Bogers (2014) was chosen due to its high relevance and since the OI phases are general enough to be applied to different kinds of contexts. Additionally, the model from Elia et al. (2020) misses information on how to design OIPs to increase benefits for the participants. Since collaboration is crucial for solving sustainability issues through OI, we combined main aspects from the presented CN and OI theory and added them as guiding principles to each dimension (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Guiding principles for sustainability-oriented open innovation platforms

2.3.1 Purpose/goals (What)

OIPs as intermediaries help problem owners to search for solution providers or problem solvers. They enable problem owners to develop their problems with other stakeholders and communicate them. Problem solvers can then submit their solutions. OIPs can also facilitate OI activities to enable the obtaining, integrating, and commercialising of

23

solutions developed by problem solvers. Their goal is to bring different stakeholders together, help them benefiting from OI, organise different OI projects, or orchestrate co-creation.

2.3.2 Stakeholders (Who)

Both the public and private sectors have an important role in OI. While the public sector is crucial for bringing important stakeholders on board, the private sector provides innovative solutions in the form of products and services. Problem owners are often companies but also public institutions such as municipalities, regions, governments, or the EU, especially in the sustainability context. They can act as problem owners, but can also co-create, facilitate, or initiate OI projects themselves. Manufacturers, retailers, customers, companies, or even the public, can bring solutions for sustainability problems and act as problem solvers. Moreover, experts holding specific knowledge can help with evaluating the solutions, so that the best ideas can be chosen. The structure of stakeholders and the context of their policies influence the OI activities.

2.3.3 Processes (How)

Obtaining

During the obtaining phase, platforms need to organise the search for sources of ideas or solutions. OIPs, therefore, facilitate the sourcing, filtering, and acquiring of new solutions. Multiple stakeholders should be involved to discuss the benefits, cost, and goals of OI projects. This strengthens their commitment and helps to avoid unexpected challenges. OIPs should find leaders committed to OI activities to ensure the continuation and success of OI projects. Commitment fosters knowledge sharing and contributes to collaborative behaviour. Platform managers can also encourage the commitment of stakeholders by providing strong support and making sure that the value from OI is clear to everyone. In the sustainability context, where problems are complex, heterogeneous stakeholders and the alignment of their motives and values is needed. Shared goals and values secure cohesion and help to understand other stakeholders, which contributes to more effective collaborations. Tasks, roles, and responsibilities should be planned and matched with the individuals or teams in this stage. Further, managers should be aware of possible managerial and political biases and different interests.

24

Integrating

Involving diverse stakeholders in the process of integration ensures the existence of different but dependent competencies that can be combined. The internal competencies to apply OI and the level of acceptance for OI should be ensured. Platforms can assist stakeholders with identifying problems with regards to their open-mindedness and help

problem owners with accepting that the source of knowledge or solution might lie outside of their organisation. Platform managers can help to identify the roles of different stakeholders in the specific OI processes and tasks and consider how they can contribute to the OI process. Setting up formal and informal communication channels is important to foster socialisation and knowledge sharing. Building trust by making goals clear to everyone, sharing information equally and ensuring the fulfilment of commitments is needed. Platforms should provide help to overcome cultural differences, thereby ensuring a positive environment where members feel comfortable sharing their ideas and resources.

Commercialising

To enable commercialisation, the business models of the various stakeholders need to be aligned, as each stakeholder should benefit from the OI activities. Results, or small wins, of OI must be demonstrated to the decision-makers to show the value and benefits of OI to ensure the continuation of OI projects. Lack of resources might create barriers, especially for SMEs. Therefore, they should be assisted by platforms by providing them with a network to receive help from established companies, intermediaries or public agencies.

Interaction

Platforms need to ensure interaction, which includes feedback, co-creation, network collaboration, and community involvement, as an important part of the OI process. This is especially crucial in sustainability context when collaboration between more diverse partners occur. Platforms can support participants to stay flexible during the OI process to react to changing environments by moving between stages. This can be a challenge for the public sector that has more complex governance structures.

25 2.3.4 Motivation (Why)

Platforms should advise that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of participants need to be considered. Intrinsic or non-pecuniary motives, i.e., purpose, are a main motivational factor at the beginning of OI processes, especially in sustainability projects. Extrinsic or pecuniary motives, i.e., profit, are a driving motivator thereafter and are needed to continue with OI initiatives. Therefore, both the need for purpose and profit must be fulfilled. Moreover, platform managers can look for new ways of social rewards such as peer recognition, networking, or access to a community, which often motivate stakeholders to participate in OI.

2.3.5 Governance (management, control, incentives)

Platform managers should choose governance mechanisms that allow stakeholders to contribute by balancing controls and rewards. Cross-sectoral collaborations are needed for sustainability, but the heterogeneity of values, mission, and purpose can generate conflicts. Therefore, conflict management is crucial in collaborations of heterogeneous partners. This can be achieved through transparent processes, being open to all members, and engaging in the formation of trust. Incentives for collaboration and punishment of non-collaborative behaviour also within companies should be established. Moreover, all participants need to understand the OI process and what to except from it. Platforms can, therefore, assist them with managing their expectations.

Based on literature from OI and CN, an adapted model for OIPs was created. We will compare this model with the results of our research and adjust it where needed.

26

3 Methodology

In this chapter, we present and argue for the choice of our methodology referring to our research purpose. First, we discuss how our research philosophy of relativism and social constructionism has influenced our research. We then argue for our choice of combining induction and deduction and applying a single case study. Subsequently, we present our sampling strategy, data collection through qualitative interviews, and data analysis based on the Framework Method. In the end, we discuss our research ethics and quality.

3.1 Research philosophy

It is crucial to be conscious about our philosophical assumptions as the research philosophy affects our choices and thus the research outcome (Easterby-Smith, 2018). In our study, we explore how individuals from different organisations, roles, and backgrounds perceive collaboration through one OIP. Due to their heterogeneity and different roles, we aim to understand how they experience the benefits and challenges of OIPs. We believe that it will enrich our study to consider these different perspectives since thereby our findings will be more credible and accurate (Saunders et al., 2016). Our study, therefore, follows the ontological approach of relativism that suggests that facts, events and experiences depend on the perspectives from which they are observed (Saunders et al., 2016). In line with relativist ontology, we follow the epistemological approach of social constructionism, based on the idea that reality is constructed through social interaction in which individuals create meanings and realities, rather than external factors (Easterby-Smith, 2018). Through our research, we want to gather rich data on how participants make sense of and interpret their collaboration with OIPs since we believe that their diverse interpretations are crucial for sense-making. Consequently, we, as researchers, are part of what is under observation and influence it. By aiming to understand the different realities of the participants, we take a subjective position to make sense of and understand the participants’ motives, actions, and experiences in a meaningful way (Saunders et al., 2016). These assumptions will help us understand the meaning participants ascribe to OIPs and are flexible to adjust our study to new themes as they arise.

27

3.2 Research approach

Aligned with our research philosophy and purpose, we base our study on qualitative research for collecting rich data since we want to gain a deep understanding of the participants’ experiences with OIPs. Qualitative research studies the meanings of and relationships between participants to develop a conceptual framework and contribute to the theory (Saunders et al., 2016). This is part of our research purpose since we want to contribute to the existing theory of OI and OIPs. Further, qualitative research helps us to understand the participants’ interpretations of their experience and what meaning they give to it. By conducting qualitative research, we can examine the participants’ constructed reality and sense-making processes (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011) as participants can express their perspectives in their own words, which is not possible with quantitative research (Hammersley, 2013). Thus, it helps us to better understand their perceived benefits and challenges of participating in OIPs and their perspective on how OIPs can be improved.

Combination of inductive and deductive approach

A combination of induction and deduction is often applied in qualitative research and offers several advantages (Saunders et al., 2016). The pre-existing theory on OI and CNs provides us with relevant concepts and areas of research. Therefore, a deductive approach is dominant in our research. In deduction, researchers move from theory to data. First, the theory and hypothesis are developed, then a research strategy is designed to test this hypothesis (Saunders et al., 2016). In deductive analysis, codes or themes are mostly predetermined and systematically searched for within the collected data (Easterby-Smith, 2018). In our work, the pre-existing theory guides our data collection and analysis by providing relevant themes. Yet, we complement our research with an inductive approach as the purpose of our thesis is to gain a deep understanding of the benefits and challenges of OIPs for participants and to develop opportunities for improvements. Induction results in the formulation of a theory or conceptual framework as a result of the data analysis. It allows to let ideas emerge from the data, which helps to learn about experiences and perceptions (Saunders et al., 2016). We follow an inductive approach by asking open-ended questions inspired by main themes. We then derive codes from the data and add sub-themes to the pre-existing main themes. By complementing induction with deduction, we become aware of relevant themes that should be considered while we avoid too rigid