Nyorienteringar inom området musikteori

Ett

musikvetenskapligt symposium

på

Hässelby slott

5-6 december

1969

För

att icke fira Svenska samfundets för musikforskning go-årsjubileum endast med

yttre åthävor beslöt styrelsen ett drygt

åri förväg att försöka anordna ett musik-

vetenskapligt symposium med deltagare från både Sverige och de nordiska grann-

länderna. Som huvudtema valdes »området musikteori i vidaste mening, inklude-

rande ’teorier om musik’, nya metoder inklusive kvantitativa (med eller utan com-

puter), musikpsykologiska grundproblem

o. dyl.» i avsikt att framför allt »fritt

diskutera nya synsätt

och

nya metoder» (citerat efter den inbjudan som utgick den

8.9.1969).

Jämte samfundet fungerade institutionen för musikvetenskap

i

Uppsala,

institutionsbildningarna i Stockholm och Göteborg, Uppsala-filialen i Lund och

kompositionsseminariet vid Kungl. Musikhögskolan som inbjudare. Den definitiva

rubriken blev »Nyorienteringar inom området musikteorin.

Symposiet ägde

rum

den

5 och

6

december på Hässelby slott utanför Stockholm

och lockade

53

förhandsanmälda deltagare jämte ett antal »extra» åhörare. (Av

de 53 var

IOfrån Danmark,

3

från Norge, ingen från Finland.)

För samman-

komsternas organisation och genomförande hade anslag erhållits från Utbildnings-

departementet.

De med förberedda inlägg aktivt deltagande blev inalles

niopersoner, därav

tre från Danmark, nämligen Finn Egeland Hansen (Aarhus), Jens Brincker (Kö-

penhamn) och Jørgen Pauli Jensen (Köpenhamn) samt sex från Sverige, nämligen

Ingmar Bengtsson (Uppsala),

BoAlphonce (Uppsala), Bernt Castman (Uppsala),

Carl Lesche (Stockholm) samt Björn Lindblom och Johan Sundberg (Stockholm).

Den

Inovember

1969

inbjöds samtliga aktiva deltagare att »bli medförfattare

i en uppsatsgrupp i Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 1970» kring symposiets

huvudtema. Härvid angavs särskilt att det ej skulle vara fråga endast om »konferens-

referat»; i stället skulle varje medverkande ha möjlighet att

»såfritt han behagar

utforma ett bidrag på grundval av sitt inlägg och vad som kan komma ut av dis-

kussionerna». Vidare angavs att »även enquètebidrag av diskussionsdeltagare kan

komma ifråga». De som

såönskade kunde få sina bidrag översatta till ett icke-

skandinaviskt språk, företrädesvis engelska.

Ett av bidragen förelåg vid symposiet endast i skriftlig form. Bo Alphonce be-

fann sig i USA och fick sitt inlägg uppläst. Ett bidrag av Finn Mathiassen, som

uteblev i sista stund, återfinnes nedan. Aven ett par andra bidrag som utlovats men

utgick vid symposiet kan väntas i kommande STM-årgångar.

Vad som publiceras i denna årgång är i enlighet med denna planering e n grupp

uppsatser baserade på symposieinlägg, i några fall (såsom undertecknads korta in-

troduktion) identiskt med vad som faktiskt anfördes, i andra fall (såsom bidraget

av Lindblom

&Sundberg) väsentligt utbyggt och omredigerat. Däremot har ingen-

ting av diskussionerna medtagits annat än

i den utsträckning uppsatsförfattarna

velat

tagahänsyn till debattinlägg.

Samfundsstyrelsen och tidskriftsredaktionen vill gärna uttrycka sin tacksamhet

över de medverkandes stora beredvillighet

attinkomma med uppsatsmanuskript.

Detär också redaktionens förhoppning att uppsatsgruppen skall kunna främja

symposiets huvudsyfte att förmedla »nyorienteringar inom området musikteori» till

ett större forum än de 53 deltagarna på Hässelby slott.

A

redaktionens vägnar:

Ingmar Bengtsson

Symposiebidrag:

INGMAR

BENGTSSON:

Kort introduktion om ämnesval och om symposiets syften.

Bo ALPHONCE:

Music theory

atYale-a

case study and a project report.

BERNT CASTMAN:

Musik och computer.

FINN EGELAND

HANSEN:

Musikalsk analyse ved hjælp

afmodeller.

JENS

BRINCKER:

Statistical analysis of music.

An application of information theory.

JØRGEN PAULI JENSEN:

Om musikkens psykologi og sociologi som en del af den

CARL LESCHE: Några kritiska synpunkter på akustisk-auditiva mätningar samt för-

FINN MATHIASSEN:

Om begrebet »covariation».

BJÖRN LINDBLOM

& JOHANSUNDBERG:

Towards a generative theory of melody.

totale musikvidenskab.

slag till andra matematiska beskrivningsmetoder.

INGMAR

BENGTSSON:

Introduktion

Det

är en stor glädje för mig att å Svenska sam-fundets för musikforskning och övriga inbjudares vägnar få hälsa alla närvarande välkomna till detta symposium om »Nyorienteringar inom området mu- sikteorin. Särskilt hälsar jag givetvis de aktiva del- tagarna välkomna. Utan dem hade det inte blivit något symposium! Det har varit mycket spännande att följa hur anmälningarna om inlägg kommit in och hur rubrikerna formulerats. Tack vare de med- verkande har vi arrangörer blivit mer och mer över- tygade om att själva ämnesvalet varit meningsfullt och att vi kommer att få vara med om intressanta presentationer och diskussioner dessa dagar. Vi vågar till och med uttrycka förhoppningen att det som kommer att hända härute på Hässelby slott kan få viss betydelse i den närmaste framtiden och kanske leda till mer bestående resultat, både i form av publicerat material och i form av kommande initia- tiv och alltså få räckvidd utöver dessa sammankomster och tankeutbyten två mörka vinterdagar.

För några år sedan ägde det rum en annan mu- sikteorikonferens här på Hässelby, som nog flera av de nu närvarande var med om. Den handlade huvud- sakligen om den grundläggande s. k. teoriundervisningen vid konservatorier och musikhögskolor och i någon mån om universitetens lågstadier. Den kon- ferensen var bitvis ganska givande, men den rörde sig över rätt begränsade delar av det musikteoretiska faltet. I centrum stod som vanligt musikalisk tekno- logi eller hantverkslära och därmed förknippade pe- dagogiska problem. Det viktigaste nya som därvidlag visade sig ha hänt under senare år är, såvitt jag minns, dels att man försökt få med modernare reper- toarskikt, dels att man lagt ökad tonvikt vid s. k. strukturlyssning och i det sammanhanget givit större utrymme åt den .klangliga» sidan i betydelsen klang- färgsiakttagelser och instrumentationsstudier. Allt detta är förträffligt, och för Sveriges del finns många av de nya pedagogiska greppen väl samlade och briljant framställda i Radiokonservatoriets serie av läroböcker.

Men varken när det gäller musikvetenskaplig verksamhet eller högre utbildning, t. ex. av blivande forskare, är den sortens teorikunskaper tillräckliga. Vi måste hålla oss med ett väsentligt vidare musik- teori-begrepp! Redan genom att nämna samman- sättningar som »konstteori» och »litteraturteori» har i viss mån antytts vad det kan vara fråga om för utvidgningar. Man kan också lite tillspetsat fråga i vad mån den s. k. musikteori vi vanligtvis räknat

och räknar med verkligen sysslar med »teorier om musik» eller ens med frågan om i vilka bemärkelser och hänseenden det alls existerar teorier om musik.

»Teori» kan definieras på många olika sätt och efter mer eller mindre stränga kriterier. Jag skall här inte taga upp tiden med att diskutera olika så- dana möjligheter; den kommer för övrigt att både direkt och indirekt att bli belyst i flera av symposie- inläggen. Bidragen dessa båda dagar exemplifierar nästan över förväntan just sådana synsätt, aspekter och metodfrågor, som enligt min mening måste aktualiseras och ges ökat utrymme inom både forsk- ning och forskarutbildning.

Jag nämner avsiktligt forskning och forskarutbild- ning i ett andetag, ty de måste ses i ett sammanhang. Vill vi ha en forskning på hög nivå, som effektivt söker draga nytta av nya idéer och framsteg, som är relevanta för dess utveckling, så krävs att de blivande forskarna fått erforderliga tanke- och metodinstrument att arbeta med. Men det i sin tur förutsätter att vi förfogar över lärare, som är kapabla att sätta de nya instrumenten i händerna på de studerande, och det förutsätter tillgång till lämpliga läroböcker eller kom- pendier eller allra minst omsorgsfullt genomarbetade litteraturanvisningar.

Har vi allt detta? För egen del tror jag man måste svara nej över nästan hela linjen

-

med det enda undantaget att några enskilda forskare förmått ut- veckla intressanta specialiteter och ligger »väl fram- me. när det gäller den internationella och tvärveten- skapliga orientering, som för varje dag blir alltmera oumbärlig. I övrigt upplever åtminstone jag det som att vi är på väg in både i en växande eftersläpning och en ond cirkel, som någonstans måste brytas och inte tycks kunna brytas på någon annan punkt än den som de kvalificerade teorilärarna representerar. Skälen till att vi håller på att hamna i en sådan situation är både uppenbara och förklarliga. Det kanske viktigaste skälet här i de nordiska länderna är att de personella resurserna är så begränsade, var- till kommer de snäva möjligheterna till specialisering på hög nivå, detta samtidigt som vårt ämnesområde blir allt mera mångförgrenat och svårt att överblicka. Ett annat skal är att de idéutvecklingar, som kan bli relevanta på musikteoretiskt område, sker på allt- flera vetenskapliga områden och med accelererad fart. Det är inte bara praktiskt taget utan helt och hållet omöjligt för den enskilde att ens hyggligt följa och och sätta sig in i alla dessa angränsande områden. Och till och med inför de områden, som han ellerhon söker följa, finns risker för att förbise väsent- ligheter, fastna för redan föråldrade synsätt

-

och hamna i dilettantism. Ytterligare ett skäl kan vara att det är svårt att fungera väl som lärare i dessa stycken och på dessa nivåer om man inte själv i någon form sysslar eller har sysslat med forskning, och det är som bekant inte alla teorilärare förunnat.Bland botemedlen vill jag beträffande både forsk- ning och forskarutbildning nämna ett, som kanhända hör till de viktigaste: att man får till stånd ökade kontakter över ämnesgränserna och att man etablerar forskarteam, överhuvud »arbetsgrupper». Även på den punkten är reaktionerna på inbjudan till detta symposium glädjande och belysande. Här kommer att medverka fackpsykologer, e n lingvist, en musik- akustik-expert, en datamaskin-specialist. Två av dessa personer representerar i sitt gemensamma bidrag explicit ett teamwork över gränserna språkvetenskap och musikvetenskap. (I förbigående kan nämnas att vi i de nya svenska studieplanerna för s. k. forskar- utbildning dragit en formell konsekvens av dessa tendenser; det anges uttryckligen att avhandlingar till den nya doktorsexamen må kunna utarbetas en- skilt eller i team.)

På

denna plats i min introduktion hade jag ur- sprungligen tänkt ge en del konkreta exempel på vad för slags nya idéer, kunskaper och metoder det kan vara fråga om. Men just när detta avsnitt var underarbete kom i expressbrev ett bidrag från Bo Alphonce (i USA), som i många stycken innehåller ungefär vad jag ville nämna och ger en hel del principiellt viktiga synpunkter därutöver.

Jag kan därför underskrida mitt föreskrivna antal minuter med hänvisning till Bo Alphonce’s bidrag. Avslutningsvis vill jag blott beröra två punkter, som gäller vad som kan komma ut av dessa dagar längre fram i tiden.

För det första skulle vi från arrangörernas sida mycket gärna se att detta symposium kunde leda till en samling publicerade texter. Vi tror att det verk- samt skulle kunna bidraga till en nyorientering och kunna bli till direkt pedagogisk nytta. En tanke är

att be alla medverkande att skriva bidrag i en upp- satsgrupp för Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning och därvid vara fria att överarbeta sina inlägg som de behagar; inget hindrar heller att ytterligare andra bidrag tillkommer.

För det andra borde man dryfta behovet av fort- bildning eller vidareutbildning av redan »etablerade» musikforskare, musikteoretiker och teorilärare. Kanske kunde det önskemålet i någon mån kunna förverk- ligas genom anordnande av en eller ett par sommar- kurser arrangerade i nordiskt samarbete?

Jag förklarar härmed symposiet »öppnat» och häl- sar än en gång alla hjärtligt välkomna.

Bo ALPHONCE:

Music theory

at

Yale-a

case study and a project report

IThe evolution of theory i n many sciences nowadays is so rapid as to make it practically impossible for anybody to be well informed. Nevertheless, i n music, where the theoretical aspect has been, and still is, underdeveloped, the challenge of keeping up to date with the latest developments i n neighbouring fields is imperative—and, indeed, stimulating. In certain cases the level of abstraction may seem discouraging, but the close relationship between many of the relevant theories should encourage the student and promote understanding. Music theory has connections with a great many other research fields; the enorm- ous theory expansion which is in full sway i n some of those fields again and again touches upon inter- disciplinary problems that are shared with music

analysts and for which existing music theory is in- efficient.

In the present discussion of requirements for a modern education in advanced music theory the greatest problem will be to remain within reasonable limits. During the subsequent stroll across our own and some neighboring pastures I will be intentionally unreasonable at times, only for the sake of emphasis. Also, any “no trespassing” sign between music his- tory and theory will be respectfully disregarded.

T o avoid mere capricious speculation I will present an existing program, of which I have rewarding ex- periences as a student-the Ph.D. program at Yale- then attach some comments and desiderata of my own and further illustrate the program with two project reports.

The new Swedish doctor’s degree is partly modelled after the American Ph.D., for which the graduate programs at Yale form a highly representative and qualitative preparation. The average student devotes

his first two years to courses and readings from ex- tensive literature lists; the two to maximally four following years are spent on his thesis. Before en- tering graduate school he has been to college for up to four years for a degree that is somewhat lower than the Swedish Filosofie kandidat degree.

The music theory program at Yale requires a minimum of eight full-year courses. The maximum load permitted for credit is four courses per year; besides these the student is free to audit any courses in any department, upon obtaining the consent of

the Director of Graduate Studies and the teacher, American universities traditionally demand a very active participation in the credit courses; consequently there is usually little time left to take advantage of the excellent opportunities for interdisciplinary orientation. In this respect the theory program is an exception. Lack of funds is a reality at many American universities these days; it also affects Yale, and the number of courses offered in the music theory program has had to be kept to a minimum. Instead, the student is encouraged to complete the requirements by taking courses in music history or in other departments, and so he has the chance to turn this necessary limitation into a very rewarding in- volvement i n some related field. This may include courses in one of the professional schools that form the typically conglomerate American university. Yale has, among others, a drama school, an art- and archi- tecture school, a school of engineering, of forestry, and a complete music conservatory.

At present there are four year-courses offered i n music theory. Two of them are given each year, “Computer Techniques for Research i n Music”, and “Special Research Topics in Computer and Electronic Music”, the first concentrating on analysis, the other on synthesis of music-both by means of computer programs. The remaining two courses form a two- year cycle in analysis, the first year in tonal music, the second in atonal.

The history courses follow a three-year cycle; the most natural choice for the theory student is “Theory and Aesthetics”, where the first year deals with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the second with the Baroque and Classic Eras, the third with the period from around 1830 up to the most recent years. These courses and the course in notation (offered yearly) bring the student in close contact with the heritage of theory treatises and yield opportunities to gain perspectives on neighbouring fields, such as

syntax and semantics.

Especially interesting outside the Music Depart- ment is an interdepartmental program that has been run on a trial basis for a number of years. It focuses on communication theory, with the departments of Philosophy, Psychology, Linguistics, Mathematics, Statistics, Engineering, and Administration involved. For some reason none of the fine arts departments has embarked on this project. In itself it is a com- plete doctoral program; for someone who is already enrolled in a full-time program it is not easy to benefit from this brilliant idea; to sit i n on one or

two courses out of this totality is not very profitable. Otherwise it would seem very natural for a music theorist to look for his complementary courses in precisely this direction. T o offer communication theory with an aesthetic specialization i n combina- tion with the existing music theory program could seem a natural step.

To take a closer look at the music courses, let us start with analysis. It is well known that music theory at Yale is strongly influenced by Heinrich Schenker -just open the Journal of Music Theory at random for evidence. It might not be clear to everybody, however, that from the metaphysical mists and dog- matic thickets that often meet Schenker’s reader, a strikingly successful model for analysis has been extracted, which moreover is applied with a constant watch for theory traps. The method is by no means free of objections, but, then, which existing music theory model could be cited as being so? In the light of the recent development in structural linguistics it seems very apt for a syntax-oriented redefinition. Incidentally, several years ago a syntactic formalization of Schenker’s theory of tonality was begun by Michael Kassler.’

Professor Allen Forte teaches the analysis course. The first phase gives an excellent training i n the analysis of tonal music according to a modified Schenker model. The second phase presents his own theory for the analysis of atonal music (“atonal” here having its usual reference to the pre-dodecaphon-

1 The project is described in M. Kassler, A Trinity of

Essays (Ph.D. thesis, Princeton 1968); also reported in E . Bowles (comp.), Computerized Research in the Hu-

manities (ACLS Newsletter, Special Supplement, June 1966, P. 42).

For an introduction to Schenker’s theories, see Allen

Forte, Schenker’s Conception of Musical Structure (Jour- nal of Music Theory, vol. 3: I, 1959, pp. 1-30).

For an exhaustive bibliography of publications by and about Schenker, see David Beach, A Schenker Biblio- graphy (Journal of Music Theory, vol. 13: 1, 1969, pp.

ic music of Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, and many of their contemporaries). i t implies a set-theoretic systematization of pitch class sets and the investiga- tion of compositional sets and their interrelations in the music studied. A recent stage in the develop- ment of this analytic model includes generative principles i n the sense that each structural entity is analysed as one of several possible outcomes of the immediately preceding entity according to a pre- defined generative scheme. This whole system of ana- lytical algorithms is programmed for the computer.2 The computer analysis course teaches one or more programming languages and involves programming exercises right from the outset, to be run at the Yale Computer Center. This year Forte has been teaching the SNOBOL versions 3 and 4 (for an IBM 7094 and 360/50 respectively) and MAD. For the encoding of musical input data Stephen Bauer-Mengelberg’s “alternate representation of musical notation”, the so-called Ford-Columbia code, is used. The course also presents and discusses examples of music re- search projects, where the computer is the main tool. One special topic of interest this year is the recently finished syntax analysing program by Raymond Erick- son (built as part of his Ph.D. thesis o n organum duplum); written primarily for musical tasks, it is

general enough for any well defined syntax. The computer synthesis course has a special con- nection with Sweden, since part of the research be- hind the synthesis program employed was carried out by the programmer and teacher of the course, As- sistant Professor Wayne Slawson, during his stay at the Speech Transmission Laboratory of Stockholm University. The program is a very general model of

the human vocal tract and is able of synthesizing practically any timbre.3 In the course the program is used for composition and research projects, often in collaboration with the rapidly developing electronic music studio of the Yale School of Music. As a preparation for this course students are recommended

to take Slawson’s one-year course i n psycho-acoustics at the School of Music. This course comprises four phases: elementary acoustics, the physiology and acoustics of the ear, the acoustics of speech sounds- espeically formant theory-and a brief view of

psycholinguistics with a discussion of syntactic as- pects of musical structure.

About the course in theory and aesthetics not much needs be said besides the obvious: it deals with the history of music theory with all the thoroughness that six terms allow. Last fall, for instance, with Pro- fessor Claude Palisca teaching medieval and renais- sance theory, two months were spent on Guido’s Micrologus, which was used as a focus of all the

early medieval theory. What is often called the modern “theory fragments” (Riemann, Schenker, Kurth, etc.) are dealt with in the last part of the three-year cycle, usually taught by Mr. Forte. The influence from modern extra-musical theories, such as information theory and structural linguistics, is also discussed i n this part of the course.

It is hoped that this quick look at the Yale music theory program has revealed a strong interest i n the computer as a research tool, alertness for fruitful quantizing models and methods of structure analysis from non-musical fields, as well as breadth and depth in the treatment of the musical material itself. W i t h this powerful program as a point of depar- ture I turn now to some personal reflections. One main task of music theory is, in my opinion, to supply composers and performers, researchers and teachers with efficient tools for analysis, explanations and predictions of musical structures i n the widest sense of the word for all their different purposes. Two main ways to reach this goal should be the careful construction of new theories i n close contact with theory development in related fields, and the evaluation of existing music theories. The following is a selective list of what I feel the need for i n order to fulfill some part of this task. It will partly emphasize things that are given ample attention in the program just described, partly call for studies that for practical reasons were left out and might never fit into a budget-squeezed university program anywhere i n the world but should still be the challenge of the individual student.

The first item on the list is something I would wish any theory program to see as a fundamental ele- ment, a meta-theoretic discussion. A reliable training in logic and the philosophy of science is, in my opinion, a basic prerequisite for a prospective music theorist. For the understanding of serious attempts

of theories it is a n excellent help; for the evaluation and critique of theories or for original attempts to construct theories it is an absolute necessity.

Sharpened logical tools will likewise find an im- mediate use in the history of music theory. Much has been done and is being done to map out the very

2 A phase of this work is described in Allen Forte, Syn-

tax-Based Analytical Reading of Musical Scores (Massa- chusetts Institute of Technology, MAC-TR-39, April 1967; printed earlier in Journal of Music Theory, vol. IO: 2, 1966, pp. 330-364, under the title A Program

for the Analytical Reading of Scores).

3 W . Slawson, A Speech-Oriented Synthesizer of Corn-

puter Music (Journal of Music Theory, vol. 13: I , 1969,

PP. 94-127).

mixed heritage the music theory tradition has handed down to us. A lot remains to be done, however, be- fore we will be able to present anything comparable

to the achievements of Anders Wedberg in his bril- liant opus on the history of philosophy4-a filtrate of those ideas that can withstand logical examination.

In our case the history of theory of course pre- supposes a great deal of work more properly carried out by philologists and linguists. Most of the treatises need critical editions and flawless translations, in which the role of the theorist might be only ad- visory; they also require commentaries, and this apparently is a large-scale task for a growing number of music theorists. For those parts of the heritage written in Latin and Greek these tasks might even be urgent, considering the decline of the classical lan- guages in modern education. In spite of the evident need for specialists, knowledge i n the classical lan- guages and a philologic training in text-critical edition techniques and translation certainly does not hamper a music theorist; it greatly helps teamwork with the relevant experts.

Some of the later parts of the heritage, the theory fragments from the last hundred years, deserve special attention because of their survival in teaching. Their authors were mostly rather unaware of the dangers of ambiguous language and metaphysical concepts. Their theories could use a thorough logical examina- tion to extract possibly fruitful ideas, trim vague and ambiguous terminologies, and separate entangled strata of description.

The development of new theories for the analysis of musical structure is a more constructive task than criticizing the historic ones. For the physical aspect efficient and reasonably stable theories are available; physical acoustics of course is an indispensable part of the equipment of a music theorist. Several psycho- logical theories are relevant for the perceptual as- pects. Accurate and updated knowledge of these is necessary for at least two reasons: any theory for perceived structure in any kind of communication has to be developed i n close contact with valid psychological theories; since psychological theories are in a constant flux, keeping track of them can save the theorist from the familiar mishap of making his own theories dependent on misunderstood, outmoded, or soon abandoned psychological ideas.

For investigations of a psycho-acoustic nature knowledge of the intermediary links, the neuro- physiological processes, gain more and more impor- tance. The inner ear as a preprocessor of acoustic signals suggests intriguing possibilities especially for

the understanding of how timbre is experienced. The particularly interesting relation between the inter-

pretation of timbre and speech sounds leads over to another of the modern hybrid sciences, psycho-lin- guistics. These two young fields seem to offer some of

the most exciting approaches to structure analysis; accordingly, they belong to the prime concerns of a music theorist.

Whether, i n dealing with structure analysis, we aim at properties of the compositional material, the notated representation, the physical or neuro-physio- logical processes, or the experience of the receiving subject, it is reasonable to find some problems in- dependent of that material specific for the respective aspect and related to problems in other areas of

structure theory. Above all, structural linguistics and communication theory have offered such points of

connection i n recent years.

Syntactic theories i n linguistics are concerned with questions that are in so many respects analogous to possible problems in music analysis, that it seems highly probable that a great deal of its methods and results would be adjustable for music theory. Lin- guistic models have already been applied i n music theory. As an example, besides the contribution of Johan Sundberg and Björn Lindblom for the present essay group, I will only mention Terry Winograd’s article in the Journal of Music Theory, 1768, where he applies M. A. K. Halliday’s Systemic Grammar to the analysis of tonal harmony. Any one of the current syntactic models-generative grammar, transforma- tional grammar, phrase-structure grammar, stratificational grammar—could be utilized i n similar ways. Inside as well as outside linguistic discussion, models from communication theory are given an important place. The “communication chain” has already materialized i n this paper. This simple model has proved fruitful for a definition of the very scope of music theory and has probably acted as one of the strongest impulses to the new developments now under way in music theory. One of the most dis- puted sections of communication theory, information theory, has exerted a less than successful influence o n recent music theory. The peculiarities it has led to in some cases have been due rather to circum- stances outside the theory as such, particularly to con- fusion about the applicability of theories to fields they were not built for; this again is a case where a basic training i n the philosophy of science functions as a powerful accident insurance.

Information theory presupposes statistical theories.

4 A . Wedberg, Filosofins historia ( 3 vols., Stockholm

1958-66). An essential contribution for the history of music theory is Allen Forte, Musical Theory in the 20th Century: A Survey (for publication in John Vinton (ed.), Dictionary of 20th Century Music, New York).

This is among the obvious reasons why an ele- mentary training i n statistics should be part of the edu- cation of the music theorists. For investigations in style analysis statistical methods may play an important part; take as an example Hampus Huldt-Nyström’s excellent essay “Det nasjonale tonefall”5 on style characteristics in Norwegian folk music, or Fucks and Lauter’s methodologically thoroughly provocative “Exaktwissenschaftliche Musikanalyse”.6 In this con- nection I want to call attention to the recent series of books on “Mathematical Linguistics and Automatic Language Processing”, especially the anthology on “Statistics and Style”, edited by Doležel and Bailey.’

Sometime in the future somebody will write the history of the influence of the computer on the development of sciences and humanities. I will not say that the computer would be responsible for the linguistic explosion, but no doubt it has meant a lot. In journals reporting computer projects the humanities columns abound in linguistic reports, while music projects appear infrequently. Of course the computer does not create any new methods by itself-it is just an unusually efficient tool. But it is demanding, and in one sense seemingly creative. It does demand a rigorous logic, and that is some- thing music theory could use. It offers a powerful feed-back of ideas for analytical approaches. Dif- ferent programming languages lend themselves more or less easily to different types of data structures. There are interesting connections between some as- pects of musical structure and some data structures. For instance, it is not hard to conceive of the notated representation of musical structure as an array. Or a musical structure could be regarded as an unfolding sequence of possible alternatives and the choice be- tween them. Such a model can be described as a tree structure, which is one of the most usual computer data structures. For different data structures many general analytical techniques, parsing algorithms, and other theory-like devices are available. These often yield valuable impulses for the analytical approach

to specific structures such as notated or perceived music. A programming language is in itself a syn- tactic structure, often of a considerable elegance. Also a long-time involvement with a programming lan- guage can result in analytical methods that might never otherwise have come to mind.

Other seductive knowledge trees show up-graph theory, heuristics, not to mention the whole complex

of artificial intelligence-but let us not go astray. Already imagining a person as an expert i n logic, the philosophy of science, the history of music theory, philology, medieval Latin, acoustics, statistics, communication theory, syntax, semantics, oto-laryngology,

psychology, aesthetics, and on top of this a

good musician and computer programmer, might seem somewhat unreasonable. Some of the fields, however, are no doubt necessary for a serious music theorist; “some familiarity”, as course requirements may have it, with the others should be to his ad- vantage.

Now what became of counterpoint and choral har- monization? I simply took the liberty of regarding a thorough experience in music, obtained by musician- ship and all kinds of useful musical gymnastics, as a matter of course in the elementary preparation for music theory i n the strict sense of the word. II

To further illustrate the scope of what I like to think of as an adequate education i n music theory, I want to report two of my research projects, which are being planned and carried out within the stim- ulation circle of the Yale music theory program.

The first project concerns computerized style analy- sis. At the present stage, plans involve a combination of syntactic and statistic approaches. Structural ele- ments will be regarded as style characteristics if they, or stable combinations of them, can be proved to belong to a class of factors that single out one group of musical works from another. It is to be expected that such a class for a certain composer will inter- sect with the corresponding class for his period, “school”, or otherwise defined stylistic group. For most composers the class of characteristics will be expected to change more or less with different periods in his development. For some, a work in a special genre might have more characteristics in common with other works in that genre and that period than with other works of the same composer, and so forth.

For computer processing a code for the musical data is needed first of all. The presently most useful code for notated music is the above-mentioned Ford- Columbia music representation. The next step neces- sary is a program that stores the input code in ma- chine memory or some peripheral memory device i n a form that makes it easily accessible for analysis programs. Several such programs exist, however, none of them handles the complete code nor saves its full information. A complete reader is presently being prepared for encoding in either SNOBOL4 or

5 Oslo 1966.

6 Porschungskrichte des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen,

No. 1519; Köln und Opladen 1965.

7 David G. Hays (State University of New York at Buf-

falo) is general editor of the series, in which Statistics and Style is no. 6 (New York 1969).

PL/I.

In the latter case, the previously mentionedsyntax analyzer by R. Erickson might be used to

great advantage. This program might also serve some

of the actual analysis, provided that a sufficiently rigorous syntax can be defined for structural events. When, and if, more or less invariant patterns of structural elements have been extracted, their distribu-

tions in different selections of music will be meas- ured. For this phase efficient standard routines are available. The most challenging phase will be the search for invariant patterns, especially since both “invariance” and “pattern” will probably have to be defined rather generously, possibly involving refer- ence to substructures, derived according to some well defined syntax. Preferably, this phase should be entrusted to the computer by means of heuristic programming techniques.

The project is large and will take considerable time; it will have to be carried out in several stages.

A series of programs I have been experimenting with lately deal with the problem of similarities between pitch collections (in the actual musical structure used

as melodic or harmonic events). Referring to a pre- defined system of similarity degrees (“similarity” taken primarily i n terms of compositionai resources, secondarily as experienced by the listener), based on Forte’s set-theoretic work,8 the programs compare two musical structures, registering with great accuracy how the one relates to the other. The input could be any two structures; a meaningful output can be expected, if the two structures are the theme of a

fugue and the entire fugue, a twelve-tone row and

a piece built on that row, a theme and variations on that theme, or why not two “dialectal” versions of the same piece of folk music.

The second project, started at the end of last spring, deals with timbre and also utilizes the com- puter. It originated in a challenging assignment in Slawson’s psycho-acoustics course. The task was to attempt to classify instrumental timbres in terms of

speech sounds. i listened to several recordings of a great many instruments, trying to perceive speech sounds. It worked very well, but not the way I had expected. Instead of being able to assign a certain speech sound to each instrument, as I had innocently anticipated, I heard a series of vowel sounds ranging from / o / (as in bought) over the neutral vowel to- wards / e / (as in bait) and / i / (as in beat) in prac- tically every instrument, as a function of raising pitch or, in some percussion instruments, of the contact point on the instrument or the decay phase of the sound, especially in cymbals. Few investiga- tions about instrumental formants have been carried out; presumably, the small bibliography in F. Frans-

son’s papers on the oboe instruments9 still is virtually complete. H e demonstrates formants in all the in- struments he used for his experiments. The ones I came to work with especially were the flute, the oboe, and the clarinet. The sound qualities that I related to the vowel series probably were something dif- ferent from the timbre that Fransson relates to the measured formants. In my case the series of vowel sounds seemed perceptually separate from a, so to speak, instrument-defining timbre, which all the time seemed to be stable, continuous, one-and-the-same, while the vowels were changing. I was completely unable to identify this more stable timbre as a vowel sound or any other speech sound.

My first hypothesis to account for the vowel series was that formants would be observable in all of the instruments, possibly being movable i n a way system- atically related, but not proportional to the funda- mental frequency of the sound. A number of physical problems are inherent i n this hypothesis. In the case of the oboe the second half of it is contradicted by Fransson’s results, according to which the formants of the oboe remain practically unaffected by chang- ing source frequency.10 It collapsed completely, when I found that I could hear the same series of vowels over a narrow span of tones practically anywhere within the range of the instrument; on the other hand the same series was sufficient for a wide span of tones, comprising almost the full range, as long as the tones belonged to the same phrase. A set of

alternative hypotheses was formulated: ( I ) the per- ception of a vowel series is an exclusively psycho- logical phenomenon, that is, it can not in any measurable way be related to any of the physical parameters of the sound or the instrument; ( 2 ) if the

player is at all able to affect the timbre, for instance by changing the shape of his oral cavity, then his reaction to combinations of phrase-beginning and phrase-ending with low pitch and high pitch (rela- tive to the range of the phrase) might involve a

regular adjustment of his embouchure, resulting i n the series mentioned; ( 3 ) somewhere along the line from air pressure waves to the brain the fundamental frequency of the sound is interpreted as the first

8 Allen Forte, A Theory of Set-Complexes for Music

(Journal of Music Theory, vol. 8: 2, 1964, s. 136-183) and Allen Forte, The Domain and Relations of Set- Complex Theory (Journal of Music Theory, vol. 9: I,

1965, s. 173-189).

9 F. Fransson, The Source Spectrum of Double-Reed

Wood-Wind Instruments (technical reports from the Speech Transmission Laboratory of Stockholm University, STL-QPSR 4/66 and 1/67).

Fig. I . The five notated tones were played on a clarinet

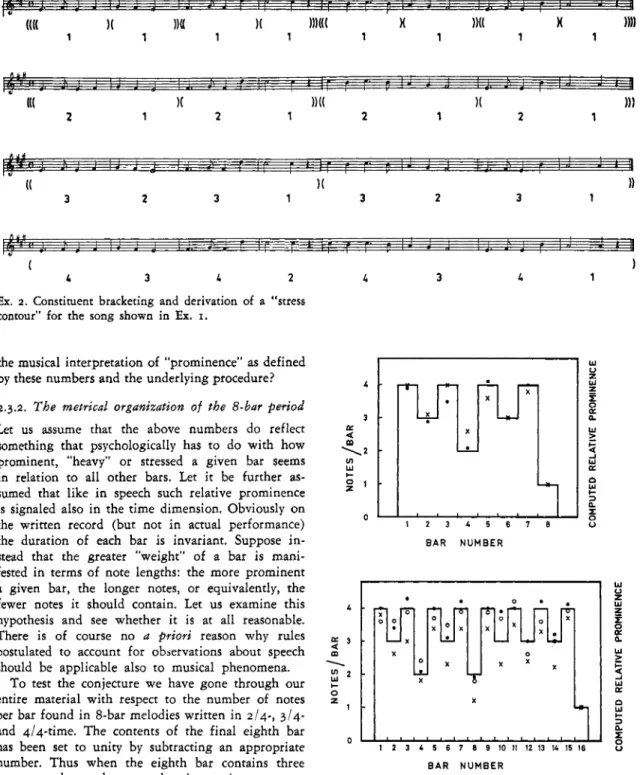

and recorded on tape. The registration above the notes was made by a Sonagraph from this recording and shows frequencies and relative intensities of their partials. The phonetic signs, roughly corresponding (left to right) to the vowels in “boat”, “but” (unstressed), “bat”, “bet”, and “bit”, are approximations of the vowel qualities actually perceived. These were all closer to the neutral vowel than the signs indicate. The formant-pattern hypo- thesis receives some support from the fact that each one of the five fundamental frequencies lies within the possible range of the second formant of the respective vowel-like sound (the first formant would be below the fundamental frequency in each case).

formant and the signal is passed on, as if, relative to the context, it represented a vowel in a correspond- ing series of relocating formants. Apparently, none of the hypotheses is completely satisfactory; each one, however, hints at a direction, along which experi- ments could help to refine, confirm or reject the re- spective hypothesis.

In collaboration with Slawson, a set of recordings was made of a flute, an oboe, and a clarinet. For each instrument the material consisted of a few short, rising tone sequences, most of moderate range and i n different parts of the instrument range, some compris- ing most of the instrument range. I listened carefully to the recordings and tried to take down the vowel sounds I heard, using a set of phonetic signs which

I invented for this purpose. My observations in the

previously described listening sessions were confirmed on the whole. The / o / (bought) was frequent in low beginnings, /e/ (bait) and / i / (beat) in high endings, while intermediate tones often sounded close to the neutral vowel, all regardless of what part of the in- strument range was covered by the range of the phrase. These observations of course d o not par- ticularly favor any of the hypotheses. Sonagraphs were made of the recordings. The results were far from unambiguous. For all three instruments concentrations of acoustic energy were obvious, but it was hard to decide whether certain neighboring partials owed their high amplitudes to a common broad peak in the spectrum or to several relatively sharp peaks or

F I F2 F I F2

Ljud 3 300 4 000 “ -I” Ljud 4 I 500 3 000 “

+

Ä”Ljud 2 600 4 500 “ + I ” Ljud 5 I 600 2 000 “

+

A” Ljud I I 000 4 000 ‘‘+

E” Ljud 6 I 800 I 900 “ - A ”Fig. 2 . The marks which are located so to speak in the

extension of Peterson and Barney’s vocal areas, show relative values of the two first formants of six sounds that were synthesized by means of Slawson’s synthesizer. The third and fourth formants of these sounds were kept constant at 5 000 and 5 500 Hz respectively.

even to one mobile peak (Fig. I). In some cases the partial-tone structure came close to the formant pattern of the heard vowel. This could suggest a re- finement of the third hypothesis, to the effect that even a poor approximation of the formant pattern of a vowel would be interpreted by the ear or brain as the vowel in question, at least in the sort of biased listening situation I was i n when I wrote my phonetic hieroglyphs.

So the margin is crowded by question marks. Plans for a continuation include a psychological experi- ment, where stimuli would be three different kinds of sounds-instrumental, speech, and synthesized- and the subjects would identify the sounds as either one of instrumental or speech sounds, without know- ing which were which. T h e sounds would be pre- sented one by one or in a simple musical context as i n the above-mentioned recordings. The synthetic sounds would be construed either as speech sounds or instrumental sounds or outside the scope of either category. The synthesizing could be accomplished by use of the computer programs designed by Slawson. Fig. 2 shows six such “outside” experimental sounds,

projected on to the coordinate system of fig. 8 i n Peterson and Barney’s article i n the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, March 1952 (vol.

24: 2), pp. 175-184. One of the questions to the material would be whether any significant difference could be observed between the attributions of speech sounds or instrument names to sounds with and without a phrase context; another whether there would be any significant correlation between the characterizations in terms of speech sounds and those in terms of instrument names for identical stimuli.

Literature

The purpose of the following list is to propose a few introductory works for some of the fields men- tioned in the article. Most of them contain extensive bibliographies.

Philosophy o j Science

E. Nagel, The Structure of Science (London 1961),

C. G.

Hempel, Philosophy of Natural Science (Engle- wood Cliffs 1966; i n Prentice-Hall Foundations of Philosophy Series, edited by E. and M. Beardsley).Nagel’s and most of Hempel’s books deal with con- cept formation and explanation i n the natural and the social sciences and in historiography.

Acoustics

The modern standard work in musical acoustics is

J.

Backus, The Acoustical Foundations of Music (NewYork 1969).

A thorough presentation of the acoustics of speech is given in

I. Lehiste (ed.), Readings in Acoustic Phonetics (Cam- bridge, Mass. 1967).

Still a standard reference in psycho-acoustics is S.

S.

Stevens andH.

Davis, Hearing. Its Psychology and Physiology (New York 1938). The Subject index of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America is excellent for newer references.Psychology

S.

S.

Stevens (ed.), Handbook of Experimental Psychology (New York 1951). This selection of essays and bibliographies for the whole field of experimental psychology is still representative. For an orientation i n musical psychology, consult for instanceR.

W.

Lundin, An Objective Psychology of Music (New York 21967).An interesting approach to the analysis of experiential contents is presented in

C.

Osgood, G. Suci, and P. Tannenbaum, The Meas- urement of Meaning (Urbana 1957).Linguistics

Most fundamental works i n structural linguistics are referred to i n

J. Fodor and J. Katz (eds.), The Structure of Lan- guage. Readings in the Philosophy of Language (Englewood Cliffs 1964).

A very representative selection of papers i n psycho- linguistics is found in

S. Saporta (ed.), Psycholinguistics. A Book of Read- ings (New York 1961).

Communication theory

C. Cherry, On Human Communication (Cambridge, Mass. 21966).

“...

ranging from Helmholtz on tones to Lewin on topological psychology to Whittaker oninterpolatory function theory to Wittgenstein on logic; from Shannon o n communication to Zipf on behavior and least effort to Toynbee on history to Jakobson on phonemics

...”

(from the quotation of Physics Today on the paper-back edition). With the additions for the second edition the bibliography contains more than 400 titles.Some of the latest in content analysis is described in G. Gerbner et al. (eds.), The Analysis of Communica- tion Content (New York 1969), which contains re- vised editions of papers read at a conference at The Annenberg School of Communications, University of Pennsylvania, spring 1966.

T h e computer as a research tool

D . Flanagan (ed.), Information (San Francisco 1966). This book, the chapters of which were originally published in the September 1966 issue of Scientific American, is the standard introduction to this field. It describes its main functions and uses; in spite of the substantial development since 1966, it is still topical. The concluding chapter by Marvin Minsky on Artificial Intelligence deserves special attention. Applications in music are described in, for instance, the following anthologies:

H . Heckmann (ed.), Elektronische Datenverarbeitung i n der Musikwissenschaft (Regensburg 1967), G. L e f k o f f (ed.), Computer Applications in Music (Morgantown 1967). The latter consists of papers read at a conference at West Virginia University, April 1966.

H. B. Lincoln (ed.), The Computer and Music (Ithaca and London 1970).

An excellent survey of the current state in com- puterized music analysis is offered in

R. Erickson, Music Analysis and the Computer (Jour- nal of Music Theory, vol. 12: 2, 1968, pp. 240-263; a slightly shorter version was first published in Com- puters and the Humanities, vol. 3: 2, November

1968, pp. 87-104). The bibliography also contains references for all the programming languages men- tioned i n the present article.

The following titles focus on computerized sound synthesis and composition:

W .

Slawson, A Speech-Oriented Synthesizer of Com- puter Music (Journal of Music Theory, vol. 13: I,1969, S. 94-127),

M . V . Mathews, The Technology of Computer Music (Cambridge, Mass. 1969),

H.

v. Foerster&

J.

Beachamp (eds.), Music by Com- puters (New York 1969; based o n papers presented at the 1966 Fall Joint Computer Conference). Computerized research projects i n music are reported in a t least the following journals:Computers and the Humanities (1966-; published by Queens College of the City University of New York, ed. J. Raben),

The ICRH Newsletter (1965-69; published by The

BERNT CASTMAN:

Musik och computer

Computern eller datamaskinen är det i särklass bästa hjälpmedel som människan har idag. Den används inom snart sagt alla områden. Fabriker styrs av data- maskiner, forskare löser allt flera problem med hjälp av datamaskiner, ja hur många exempel som helst skulle kunna plockas fram för att visa datamaskinens fördelar. Man skall dock inte glömma att den är en maskin. Computern har därför också naturligtvis alla de nackdelar som en maskin har. Den kan t. ex. inte tänka. Allt som datamaskinen utför, måste i förväg ha kodats och matats in i dess minne. Detta innebär att datamaskinens användningsområde begränsas av hur omfattande de instruktioner som den försetts med är. Därvid kan konstateras att maskinen är i högsta grad beroende av den eller de människor som förser den med uppgifter.

Mitt anförande skall inventera datamaskinens möj- ligheter som hjälpmedel vid musikvetenskaplig un- dervisning och forskning. Jag har delat upp de upp- gifter som kommer ifråga i tre grupper. Dessa är inga fristående objekt utan hör mer eller mindre ihop, men för att inte göra ämnet alltför komplicerat, kommer de att behandlas var för sig. Grupperna är:

I) Noterad musik, 2) Ljudande musik och 3) Elek- tronmusik.

Vi betraktar först den noterade musiken. Dess första punkt upptar översättning mellan olika koder,

Institute for Computer Research in the Humanities, New York University, ed.

G.

Horowitz),Computing Reviews (1960-; published by the Asso- ciation for Computing Machinery, New York, ed.

E. Weiss).

An early inventory of such projects was published in E . Bowles (comp.), Computerized Research in the Humanities (ACLS Newsletter, Special Supplement, June 1966).

Artificial Intelligence The standard introduction is

E. Feigenbaum and

J.

Feldman (eds.), Computers and Thought (New York 1963).A series of fascinating new experiments and theories is reported in

M. Minsky ( e d . ) , Semantic Information Processing (Cambridge, Mass. 1968).

t. ex. Ford Columbia, Numericode, Alma etc. Me- ningen med detta är att man skall kunna lagra musik på ett för datamaskinen lämpligt sätt. Ett av sätten, när det gäller noterad musik, är att helt enkelt skriva av notbilden och lagra koden i datamaskinen. Då finns olika tillvägagångssätt. Ett är att skriva av not- texten, precis som den ser ut, lägga i n notlinjer och övriga representationer på något sätt, och det är vad dessa koder skall göra. Fördelen med detta är, att man skulle kunna tillhandahålla ett hur stort bib- liotek som helst av noterad musik. Man skulle kunna mata in musiken med vilken kod man vill, bara man också talar om hur koden ser ut eller är uppbyggd. Sedan bildar man en bibliotekskedja i någon form, där man kan byta dylik information. Det skulle då bli ganska lätt för musikforskaren att komma å t det verk han önskar. Denna tanke har skymtat i mitt samarbete med Bo Alphonce, där vi började lägga upp en del Bachkoraler för att ev. användas enligt den metod som beskrivits. Det arbetet finns alla möj- ligheter att fortsätta. Problemet är som inom alla forskningsområden en fråga om pengar. Kan man på något sätt erhålla medel för ett dylikt projekt, kan man skaffa fram en hur stor samling datamaskin- uppmatad musik som helst. Sedan kan en musik- forskare begära att få ett visst verk utmatat i någon form. Idag är det väl inte så stor valmöjlighet. Man

får ut verket i motsvarande kod igen eller eventuellt översatt till någon av de andra koderna. Det existerar, såvitt jag vet, översättningsprogram mellan de tre

ovan nämnda koderna, Iåt vara att de inte är full- ständiga. I framtiden skulle man kunna utvidga för- farandet till flera utmatningssätt, som är mera lämp- liga för den musikkunnige. Man skulle t. ex. kunna få utmatning direkt på notpapper, alltså kunna skriva ut verket precis som det är noterat. Det är endast en fråga om kodning och därmed en kostnadsfråga. Det finns inte någon principiell datasvårighet vid Iösandet av detta problem. Det existerar en lösning, och det är bara att koda av den. Dock måste t. ex. utmatningsorgan hos datamaskinen förses med speci- ella skrivtecken.

I detta sammanhang vill jag fråga: på vilket sätt skulle detta kunna komma svensk eller nordisk utbildning i musikvetenskap till godo, och är det realistiskt att man försöker lösa detta problemkom- plex i Norden? Jag vill ställa dessa frågor, när det gäller alla de arbetsuppgifter som jag berör, och kom- ma fram till vad man hos oss lämpligen bör välja som arbetsfält åt datamaskinen inom musiken.

Att institutioner i Norden skulle bli centraler för den föreslagna bibliotekskedjan tycks mig orimligt, framför allt beroende på de höga kostnader som ett sådant projekt skulle medföra. Att man skall med- verka i det anser jag fullt givet, därför att projektet med gemensamma ansträngningar bör vara genom- förbart. Oberoende av var i världen man befinner sig och om man använder något av de generella programmeringsspråken, som finns inom datatekni- ken, så kan man dra nytta av resultatet på alla ställen, där motsvarande språk används. Program- meringsspråk är faktiskt en av de saker ifråga om datamaskiner, som är internationella. Man skulle kunna f å mycket stora mängder noterad musik in- lagrad i datamaskinen en gång för alla, och man skulle kunna tillhandahålla en lagringsform så att ingenting går förlorat, exempelvis genom dokument- förstöring. Man skulle i framtiden kunna skriva ut materialet på ett mera acceptabelt sätt än vad som är möjligt idag. Sedan skulle det kunna användas som underlag för en hel del undersökningar om noterad musik.

Statistik är en av de vetenskaper som tillämpas mycket ofta inom snart sagt alla områden, och stati- stik är ett genomgående begrepp när det gäller nutida musikforskning. Där skall man dock tänka på att inte göra statistik för statistikens egen skull, utan man bör göra meningsfull statistik. D å uppstår proble- met: Vad är meningsfull statistik? Mitt svar på denna fråga är: Det är kanske bättre att göra ett försök i onödan som är galet, än att inte göra försöket alls.

Då har man i alla fall kommit fram till att den meto- den kanske inte var den allra bästa.

Samarbetet med Bo Alphonce hade egentligen som huvudsyfte att undersöka möjligheterna att detektera förekomsten av mönster i noterad musik. Vi under- sökte först möjligheten att med statistik beräkna före- komsten av vissa ackord i tolvtonsmusik, vilket gav lyckat resultat. Därefter förberedde vi undersökning av större mönster, enligt den s. k. pattern recognition- metoden.1 Denna är något som kan vara aktuellt även inom ljudande musik, dvs. man försöker leta efter mindre eller större mönster, strukturer, i den musik man vill analysera. Där möter man en ganska stor svårighet. Man har sysslat med motsvarande problem inom lingvistiken i femton år och har väl ännu inte kommit fram till något särskilt lysande resultat. Man kan konstatera, att pattern recognition-metoden är en av de metoder man behöver för automatisk språköver- sättning. Man måste kunna fastställa var i satsen ett ord står, alltså inte bara vad det betyder. Frågan är om man kan tillgodoräkna sig dessa femton års erfarenheter, när det gäller motsvarande problem inom musiken. En del av de undersökningar man gjorde på ett tidigt stadium, kan förmodligen till- lämpas direkt. Viktigt är bl. a. att man inte väljer för stort mönster. Ej heller ett för litet mönster är att rekommendera, eftersom man får mycket svårt att kombinera dessa små pusselbitar. När det giller stora mönster, är problemet att datamaskinundersökningen

tar lång tid och blir mycket dyrbar.

Är det lämpligt, att man försöker lösa detta kom- plex i Norden? Jag tycker inte det, bl. a. därför att vi har ringa erfarenhet av datalingvistik. Det är möj- ligt att vi kunde göra vissa delundersökningar och försök, men projektet som sådant är datamässigt inte så långt avancerat i Norden, att man vill rekommen- dera Nordens musikforskare att angripa detta pro- blem med computer

-

än så länge.En hel del intressanta frågeställningar berörs av detta pattern recognition-problem. Man skulle t. ex. beträffande okända musikstycken kunna konstatera att de med stor sannolikhet skrivits av den eller den tonsättaren genom att man på något sätt fastställer hur en viss tonsättare går till väga när han skriver sin musik. Detta förutsätter att tonsättaren är konse- kvent och stabil i sin kompositionsteknik. Enligt vad jag blivit upplyst om, skulle detta gälla exempelvis J. S. Bach. Det är bl. a. därför vi började uppmatning av vissa Bachkoraler, för att så småningom använda materialet till att kontrollera, om Bachs kompositions- teknik verkligen var så stabil. Jag vet inte om upp- fattningen är riktig, men principen bör kunna ge-