L U L E Å I U N I V E R S I T Y

OF T E C H N O L O G Y

2004:12

DOCTORAL THESIS

Life-story Perspective on Caring

within Cultural Contexts

Experiences of Severe Illness and of Caring

Terttu Häggström

Department of Health Science

Division of Nursing

Life-story perspective on caring witfiin cultural contexts

Experiences of severe illness and of caring

Terttu Häggström

Department o f Health Science D i v i s i o n o f Nursing

Vi bär redan en hel del av vår unika kommande ålderdom med oss, när vi går genom livet.

(We are already carrying a great deal of our unique coming old age with us

when we are going through life.)

Life-story perspective on caring i n cultural contexts

Experiences o f severe illness and o f caring

Terttu H ä g g s t r ö m

Division o f Nursing, Department o f Health Science, The Faculty o f Arts and Sciences,

Luleå University o f Technology, Sweden

Distribution:

Department o f Health Science Division o f Nursing

H e d e n b r o v ä g e n

SE-961 36 Boden, Sweden

Phone:+46 921-758 00 Fax:+46 921-758 50

Homepage: w w w . h v . l t u . s e

Terttu H ä g g s t r ö m

Life-story perspective on caring i n cultural contexts. Experiences o f illness and o f caring.

ISSN: I S R N

Cover picture: Irja Almgren-Hedman © 2004 Terttu H ä g g s t r ö m

Printing O f f i c e at Luleå University o f Technology, Luleå Sweden, A p r i l 2004

A B S T R A C T

Häggström, T. (2004). Life-story perspective on caring within cultural contexts. Experiences of severe illness and of caring. Department of Health Science, Luleå University of Technology, S-97187 Luleå Sweden.

People are afflicted b y severe illnesses and adversities in life and they practice care privately and professionally in different cultural contexts f r o m the view o f their o w n life-story perspective. Five studies w i t h a qualitative approach were linked together w i t h the overall a i m o f disclosing the experience o f severe illness and caring w i t h a life-story perspective i n different cultural contexts. Audio-recorded, transcribed narrative and reflective interviews were analysed w i t h a phenomenological hermeneutic approach. Data were from 34 people living w i t h a stroke i n Sweden and Vietnam, five Vietnamese relatives and 29 professional carers caring f o r people w i t h a stroke i n Vietnam, w i t h dementia i n Sweden and girls living on the streets i n East A f r i c a .

I n this study, living w i t h a stroke meant living w i t h a sudden, adverse event that had interrupted the past o f the life story from continuing i n a similar fashion i n the future. Apparently, some interviewees had not integrated the stroke event w i t h their narrative identity and their life stories. They seemed to be confused about what had happened to them. The sensed feelings o f living w i t h a stroke i n the study from Sweden were conveyed w i t h the use o f a metaphoric language. L i v i n g w i t h a stroke i n Vietnam meant feeling as a weakened thread i n the f a m i l y net. Caring professionally in this context meant collective narrative identity w i t h a view o f being assistants, advisers and supporters o f a ' f a m i l y network'. Carers identified as good at achieving an understanding o f people w i t h dementia used maternal thinking emanating from personal experience together w i t h knowledge about each resident's life stories and the course o f the disease. These carers used affect attunement and personal talents. The carers tuned into a resident's affective state, noticed signs, put these into sentences and stories that corresponded w i t h the narrative identity and the l i f e story o f the resident i n the caring situation. Professional carers working among girls l i v i n g on the streets i n East A f r i c a felt that they became committed to caring and had motherly feelings when they met w i t h the girls. Caring f o r these girls meant fighting against the grip o f street life, but also experience o f satisfaction and hope. I t meant experiencing powerlessness and frustration, and the carers felt squeezed between integrated values and the perceived demands from the girls i n their meeting w i t h them, whilst conveying visions to the girls o f a better future.

Inspired by Ricoeur's philosophy on language and personal identity, the findings from the f i v e papers indicate that a life-story perspective can serve as a framework f o r bringing human experience i n various cultural contexts and different ages into comprehensible language. This perspective should be useful in professional nursing when caring f o r people who encounter adversities i n l i f e as an afflicted person or relative. I t is suggested that a life-story perspective can serve as a framework f o r professional nursing care that aims at a good qualify o f care.

Keywords: Caring, nursing, l i f e story, experience, maternal tWnking, narrative identity, metaphors, stroke, dementia, living on the streets, culture.

Häggström, T. (2004). Life-story perspective on caring within cultural contexts

Experiences of severe illness and of caring.

ERRATA

Page

Para-graph

12 1

13 2

24 1

27 Table

28 1

28 2

28 Last

32 1

40 Table 5

57 2

63

(D

323

Line Error Should be

10 ..patients as well their

realtives..

3 ... s described by J. and H.

ErÜcson(1982,1988).

1 ... inspired by Ricoeur's (1976)

is under...

Last = Professional carers...

5 (Table 1)

2 These informants had had

eating problems ...

2 ... 17 males and 20 males.

6, 9 (Leininger, 1985; (Mishler

1986)

Mrs Incomplete text

Cilia

and

Olga

3 .. .the first author..

Last Bauman, Z. (2000). Colure as

praxis

Table 1 (Women with nonembolic

infarction) 59

... patients as well as their relatives

.. .as described by Eriksson (1982) and

his wife (Erikson, 1988).

.. .inspired by Ricoeur's (1976)

interpretation theory is under ...

*= Professional carers...

(Table 2)

Eighteen of these informants had had

eating problems...

... 17 males and 20 males (V).

(cf. Leininger, 1985; (cf. Mishler 1986)

Respect. Two mothers' understanding

of having children with problems

.. .the second author..

Bauman, Z. (2000). Culture as praxis

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

O R I G I N A L P A P E R S 1 I N T R O D U C T I O N 2

Nursing as a caring profession 4

The human caring 5 Cultural aspects 6

L i f e story and personal identity 9 L i v i n g with severe illness and in adverse circumstances 10

A i m s in the thesis 14 P H I L O S O P H I C A L A N D T H E O R E T I C A L P E R S P E C T I V E 15

O u r narrative identity 15 C a r i n g as the human mode of being 16

Sharing an understanding of the meaning of our experience 17

O u r praxis constructs our culture 20

M E T H O D O L O G Y 22 Pre-understanding 24 Material and methods 26

Research settings 26 Informants 28 Ethics 29 Data collection 30 Projective interviews 31 Narrative interviews 31 Narrative and reflective group-interviews 32

Reflective, individual interviews 33

Observations 33

Analyses 34 F I N D I N G S 35

L i v i n g with a stroke 35 Being involved as a relative 37

C a r i n g professionally for people who are in vulnerable situations 37

R E F L E C T I O N S 42 Personal identity, severe illness and caring 42

Narrative identity and being a relative 45 Narrative identity and being a professional carer 46

Professional carers and the narrative identity o f people w i t h dementia 47

Professional caring 48 Understanding experience 50

Understanding the meaning i n actions 50 Meaning embedded i n metaphoric language 52

C a r i n g and culture 53 Theoretical and methodological considerations 55

S U G G E S T E D I M P L I C A T I O N S F O R N U R S I N G C A R E 59

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S 61

R E F E R E N C E S 63 G L O S S A R Y A N D D E F I N I T I O N S I N T H E T H E S I S (Appendix) 73

O R I G I N A L P A P E R S

The dissertation is based on the f o l l o w i n g papers, w h i c h w i l l be referred to i n the text b y their roman numerals.

I H ä g g s t r ö m , T., Axelsson K . , Norberg A . (1994). The experience o f living w i t h

stroke sequelae. Illuminated by means o f stories and metaphors. Qualitative Health Research 4, 3, 321-337.

I I H ä g g s t r ö m T., Norberg A . , Trän Quang Huy. (1995). Patients', Relatives', and

Nurses' experience o f stroke i n Northern Vietnam. Journal of Transcultual Nursing, 7:1, Summer.

I I I H ä g g s t r ö m T., Norberg A . (1996). Matemal thinking i n dementia care. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 2 4 , 4 3 1 -438.

I V H ä g g s t r ö m T., Norberg A . (1998). Skilled carers' personal ways o f achieving an

understanding o f people w i t h moderate and severe dementia. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 12, 3 239-266.

V Sävenstedt, S., H ä g g s t r ö m T. Counselling for re-direction o f l i f e stories. Narrated

experiences o f female professionals working w i t h girls l i v i n g on the streets i n East A f r i c a . Revised manuscript sent for publication M a r c h , 2004.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Care-receivers', relatives' and professional carers' views on care, relationships and families vary i n different parts o f the w o r l d as they are influenced b y traditions and religions (Rarcharneeporn & Dale, 2000). Reasonably, integrated values and caring praxis i n relation to f a m i l y bonds and professional care w i l l affect the understanding o f meeting w i t h adversity i n l i f e as an afflicted person, as a relative and as a professional carer.

Our w o r l d is rapidly becoming a global community w i t h the trends i n migration, travel and communication. Nursing has a history o f attention to culture and nowadays this attention is demonstrated i n the curricular content o f nurse education programmes, and health care institutions are increasingly becoming aware o f issues relating to language and culture. The efforts made, so far, to increase an understanding between people f r o m different cultures mainly concentrate on the differences i n various cultures rather than on the founding communalities shared by all us, for example personal change that takes place when people interact ( D u f f y , 2002). The subtle communalities i n a human life, such as experience and feelings, can easily be shadowed by observable differences i n behaviours and languages when people f r o m different groups or countries meet i n situations o f professional caring.

As humans we are unique persons, steadily changing beings and related to ourselves and to others regardless o f where we live our lives. A l l o f us are also undergoing a maturation process that takes place f r o m infancy to old age that changes our views on life and its meaning (Erikson, 1982; Erikson, 1988; Tomstam, 1994; 1999). This v i e w contradicts a common perception o f ageing after middle age as a state o f deterioration or retrogression to developmental stages, passed earlier. A t both ends o f our lives, as newborn infants and as very old people we are fragile, vulnerable and dependent on others f o r our survival and well-being. However, the experiences gained and the maturation processes undergone constitute a significant difference between a very old person and an infant. During adulthood there is, for most people, a period o f relative independence, even i f we as adult,

autonomous people are fragile and vulnerable, although to a seemingly lesser extent (Bauman, 2000 p. x v ) . I n addition, accidents, serious diseases, or other adverse circumstances can alter our relative independence.

Ricoeur's (1992) philosophy on our identity and our understanding o f ourselves and others has inspired m y understanding o f our human condition. He suggests that we are bound to live i n relationships w i t h others and advocates that we be sensitive toward others' uniqueness w i t h a responsibility towards ourselves and others. The sensitivity towards the uniqueness o f a person makes it possible to respond to the perceived demand and at the same time ground our o w n uniqueness. I t can be presumed that a care receiver, regardless o f age and condition, conveys appeals to be understood as a unique person w h o needs assistance. Caring relatives or professional carers cannot experience their care-receivers' experiences, but they can utilise their sensitivity towards the uniqueness o f the person. The sensitivity guides a caring response to the perceived demands (Lögstrup,

1971; van Manen, 2002; Ruddick, 1989; Roach, 1997). The caring response is inseparable f r o m our nature as human beings, but the sensitivity towards others can be desensitised and thus people can become non-caring (Gaylin, 1979; Roach, 1992).

Language is used f o r telling stories about the personal experiences we gain throughout our lifetime. This human ability makes it possible f o r us to understand ourselves and others and to share an understanding o f the meaning o f our experience w i t h other people (Ricoeur, 1976). I n professional caring situations the meaning o f the care receiver's experience should be shared w i t h the care-receivers and their relatives. Such dialogues w i l l both reflect and influence the understanding o f the meaning o f the experience o f all involved. People, who are l i v i n g w i t h severe illness such as a stroke or Alzheimer's disease, as w e l l as children without caring parents, are subjected to other people's willingness and ability to caring for and about them. A s some o f these people have various difficulties i n using verbal language they also depend o n other people's ability and willingness to share the meaning o f their experience w i t h them. Assumedly there are f a m i l y and professional carers w h o can sense subjective, tacit meanings o f their

care-o f ccare-omprehensive language they may use figurative expressicare-ons that can assist them w i t h tuning in to feelings and promote creative thinking (Gendron. 1994). Comprehensible stories can be developed, altered and mutually agreed upon as being relevant.

Nursing as a caring profession

Nursing as a caring profession is founded i n a combination o f art and human science. The art of nursing is practised when the carers are able to sense the meaning o f the care-receivers' and their relatives' experience and skilfully perform care to the satisfaction o f all involved (Johnson, 1994). A r t as understood in everyday language can also be used i n caring. For example, music and drama can be used i n order to stimulate expressions o f feelings (Aldridge, 1996), to achieve a dialogue in caring f o r people w i t h dementia (Aldridge, 2000) and music can be used to convey and to develop our identity (Ruud,

1998).

Nursing has been described as performing within a relation w i t h care-receivers and their relatives ( L ö v g r e n , 2000, pp. 26-29; Watson & Smith, 2002) and it has been suggested that it is undesirable to have one definition. I n this thesis nursing care is understood f r o m the perspective o f the Swedish concept ' o m v å r d n a d ' , which relates to the task aspects o f caring as w e l l as to the relational aspects (Sjöstedt, 1997) that is founded i n our mode o f being. Caring, as an expression o f our humanity, is not unique to any profession, but can be seen as unique i n nursing as it embodies qualities and essential characteristics o f nursing (Roach, 1992). ' O m v å r d n a d ' can be shown i n caring episodes that satisfy the care receivers and their relatives. These episodes have an embedded meaning w i t h regard to the quality o f the caring performance (Asplund, 1994; Szebehely, 1996) and o f the caring relationships (Roach, 1997). Good quality in caring involves a carer's attitude towards the unique person as a care-receiver w i t h her or his relatives, rather than an attitude towards generalised care-receivers. The carers' attitude should support the personhood o f the care-receiver, regardless o f her or his ability to use verbal communication ( K i f w o o d , 1997; Malmsten, 1999).

Education i n nursing presupposes that students assimilate scientifically based knowledge, acquire practical skills, and integrate both w i t h their personal experience. Personal experience and knowledge that is integrated w i t h people's ways o f reacting and acting i n different situations has been referred as k n o w i n g more than we can tell, 'tacit k n o w i n g ' . Such 'tacit k n o w i n g ' emanates f r o m experiences that give a sensed wordless meaning to similar situations later i n life (Polanyi, 1983). Theoretical (knowing that) as w e l l as practical knowledge (knowing how) are needed f o r developing a practical expert i n caring (Benner, 1984). It can be assumed that i t is possible to make some 'tacit' knowledge explicit through making professional carers reflect o n what they have been observed doing.

Most professional carers are women (Evans, 1997; Ryan & Porter, 1993; Villeneuve, 1994), even i f men f o r long have worked as nurses i n asylums, military service and private associations (Macintosh, 1997). M e n w o r k i n g as nurses i n Sweden; N o r w a y and Finland emphasise their task-orientated behaviour as opposed to women nurses who emphasise their people-orientated behaviour. This v i e w is seen as influenced by the historically predominant social pattern o f men as breadwinners, hardly participating i n domestic w o r k and i n caring for children (Kauppinen-Toropainen & L a m m i , 1993). It can be assumed that this reflects the prevailing situation i n most countries, even i f research indicates that men as fathers are i n a process o f involving themselves more i n f a m i l y l i f e , including caring for children (Plantin, 2001).

The human caring

A s humans we have experience o f being cared f o r and about. Most people care f o r their children, beloved relatives, friends and acquaintances; and people i n general possess a reflexive readiness to respond to helplessness. V i e w i n g our capacity to care as our nature as human beings presupposes a relational way o f being and it implies philosophical, ethical and epistemological concerns (Gaut, 1983; G a y l i n , 1979; Roach, 1992; Ruddick,

Caring for children has a special and familiar relationship to human dependency that can be relevant f o r other caring relationships where dependency on carers prevails. It includes emotional aspects and has historically i n most societies been regarded as a private domain o f women. However, it should be considered as denoting a broader meaning o f 'parenting' and not as something limited to and exclusively inherited i n the biology o f women ( H o l m , 1993; Ruddick, 1989). I n a broader meaning, mothering as described by Holm (1993) and maternal thinking and practice as described by Ruddick (1989) can be seen as actualising our inherent humanness.

Holm (1993) and Ruddick (1989) advocate that taking on the responsibility as a mother is basically a social practice, based on an uneven relation that should not be violated. The uneven relation has ethical implications that are applicable i n other caring and uneven relations. The changes that take place when somebody is mothering cannot be explained with biology and can only be reflected upon in retrospect. ' M o t h e r i n g ' is to H o l m (1993) "a condition one enters, a relation between two human beings, a social institution with norms, roles and expectations, and a traditionally transmitted practise with aims, demands, procedures, competences, virtues, vices and nowadays even so-called experts and professionals {ibid., p. 101, H o l m ' s italics i n bold)". Ruddick (1989, pp. 13-27) has an epistemological view. Maternal thinking is the intellectual activities that are different from, but not separated f r o m emotions being practised. She suggests that the development o f capacities to mother means developing lasting qualities that she names 'maternal'. A similar development o f desirable qualities i n caring can take place when people care f o r relatives, f o r example, caring f o r a relative w i t h Alzheimer's disease (Bar-David, 1999). It can be presumed that being sensitive to the caring demands o f people i n vulnerable situations and adapting oneself to these situations forms minking, knowing, and a preparedness to create reciprocal relationships.

Cultural aspects

Questions about quality o f care are largely questions o f values. Meeting w i t h people and gaining knowledge steadily influence carers' values and beliefs that are embedded w i t h i n the story or the l i f e experiences o f a person (Heliker, 1999). This may or may not be

congruent w i t h those o f the professional discipline. Professional carers i n institutions construct together a caring culture w i t h i n each department, ward or group dwelling, which constitutes 'a mini-world of being in here' (Bauman, 2000, p. x x x ) . The culture in such ' m i n i w o r l d s ' also reflects the common values i n the surrounding society, that may or may not support caring as being as part o f our nature and as essential for human development throughout the lifespan. Whatever the prevailing values are i n a ' m i n i w o r l d ' or i n a society regarding for example caring and gender, they cannot be used as an excuse f o r cruelty and violation o f human rights (Okin, 1999).

Group dwellings f o r people w i t h dementia i n Sweden can be seen as ' m i n i worlds'. A home like caring context can support residents and carers to i d e n t i f y themselves as 'being i n here' {cf. Bauman, 2000). Professional carers i n such units should ideally consider these homes as being more than their working places. I f they share a meaning o f caring f o r a home-like atmosphere w i t h the residents' relatives and each other, i t should support their efforts to understand and support the residents' meaning o f being at home in a broader existential sense (Zingmark, 2000, pp. 30-31).

The education o f professional carers i n Sweden has been developed over years, has varied i n content and length and is regulated by authorities. M o s t countries i n East A f r i c a are, like Vietnam, considered to be developing countries, w i t h a comparatively short history o f educating caring professions. The educational programmes are greatly influenced by Western 'models' and way o f minking, w h i c h does not always correspond w i t h the prevailing values i n these countries. The education o f registered nurses ( R N ) and enrolled nurses ( E N ) i n Zambia was almost a copy o f the British model around the 1980s and many professionals i n the health sector got their health education i n the West before and after achieving independence around the 1960s. The influence f r o m the West continues o n several levels i n East A f r i c a , for example among other symbols o f wealth i n Kenya today are having one's children i n schools abroad and going o n shopping tours to Europe (Kilbridge, Suda & N j e r u , 2000, p. 78), which assumingly interfere w i t h several traditional values.

Westerners have been involved i n developing the nursing profession in most countries i n East A f r i c a and some places i n Northern Vietnam. U n t i l recently there was no professional concept used f o r nurses i n Vietnam, regardless o f the length o f education. Instead an expression was used w i t h a connotation to a general meaning o f taking care o f children, sick people, elderly etc. The Vietnamese traditions w i t h Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism and a 'very f o r e i g n ' language to people f r o m the west seem to have resisted most Western influence o n values related to f a m i l y life (my experience).

I n spite o f Western influence, the carers i n these countries have to perform their care i n the context o f their culture. The society i n East A f r i c a is i n rapid transition and young girls nowadays admire females starring i n Western f i l m s and soap operas showing on television (Frederiksen, 2000). B i g cities i n Vietnam are also rapidly becoming ' m o d e m ' with regard to education and technical development, but the 'traditional f a m i l y ' that still has agricultural roots, seems to remain as the main institution f o r supporting its members throughout the entire life cycle (Johansson, 2000, p. 16); even i f higher-income households i n Asian countries shift their service demand to more qualified providers, such as hospitals (Toan, 2001, p. 17).

I n East A f r i c a , the development is hampered by political instability, corruption and internal conflicts. The societies have f e w structures and hardly any resources to deal w i t h refugees, droughts and poverty. I n large cities such as Nairobi, the organisation reflects migration and a youthful population. The former traditional, extended family system, that took responsibility f o r all its children's care, is breaking down as w e l l as other supporting traditional systems (Gracey, 2002). No structures i n the society have replaced their caring function for children when parents die or i f they f o r social reasons cannot care f o r their children. I n the increasing number o f street children, girls are especially vulnerable. Unprotected, they are often sexually abused, often infected w i t h various sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and get pregnant (Kilbridge, et al, 2000). These authors (p. 3) claim that street children represent a worldwide phenomenon despite cultural differences and that the backgrounds of street children are remarkably similar.

There should be interesting meanings, o f the experience o f living w i t h a severe illness and o f caring in Vietnam, where the 'traditional f a m i l y ' still exists, and o f professional caring in East A f r i c a where the tradition o f 'extended f a m i l y ' is disappearing.

The quality o f professional caring i n institutions depends on the carer's knowledge and skills as w e l l as on A culture that supports qualify admits a variety o f meanings to be expressed. The actions w i l l be characterised b y open rules and a development o f practice, which is different f r o m routine practice (Göranzon, 1988). Excellence i n caring can be seen as what the social group's culture notifies as good. Professional carers should develop a shared meaning o f good quality o f care w i t h care-receivers, their relatives and colleagues as a foundation f o r providing good care (Benner, 2000). Traditions, values and structures i n a society may support or hinder professional carers f r o m being caring.

L i f e story and personal identity

Each human has an inherited uniqueness as a person that remains throughout our lives. A t the same time we are steadily growing older, developing and steadily influenced b y l i v i n g in relations w i t h other people. This gives each person a steadily changing narrative identity that is constructed when we tell stories, that makes i t possible to understand the meaning o f our o w n and others' experience (Ricoeur, 1992). The ability to tell stories about experience i n life is universal and concerns meaning and coherence f o r a person w i t h i n a specific culture (Cohler, 1991).

Memories o f our experience o f being understood, not being understood or being misunderstood are interrelated w i t h feelings and connected w i t h various contexts i n our life stories. Professional carers should aim at achieving an understanding o f the care-receivers and their relatives' experience through shared narrative dialogues (Norberg, 1994), w h i c h is a different approach f r o m care receivers and their relatives being given pre-set questions to answer (Skott, 2001). Narrative dialogues w i t h a life-story perspective can enhance the professional carers' options for achieving an understanding o f the care receivers' and their relatives' experience o f their situation as a basis f o r making appropriate care plans (Heliker, 1999), care-receivers w i t h cognitive impairment

Some people are disabled or, f o r various reasons, unable to tell stories about then-experience. So are often people w i t h a severe stroke, dementia ( f o r example Alzheimer's disease) or children w h o might be restricted b y social norms. K i t w o o d (1997) held that others can preserve a person's narrative identity and Thomasma (1984) argued that our responsibility toward the dependent young is to guide and to 'protect the future'. He saw that as different f r o m our responsibility toward o l d people or people w i t h chronic illness, whom we must honour and respect to protect the past.

Living with severe illness and in adverse circumstances

People w i t h severe stroke or a dementia disease like Alzheimer's are vulnerable as they are living w i t h severe illness. Young girls living on the streets are also vulnerable as they are living i n adverse circumstances. These three different groups o f people have i n common that they, to various degrees, depend on others' care f o r survival and well-being and they are likely to face difficulties i n conveying their experience and preferences.

Severe stroke and Alzheimer's disease are neurological and chronic illnesses that need to be managed by the afflicted person and the f a m i l y , o f t e n together w i t h professional carers (Wright, Hickey, Buckwalter & Clipp, 1995). Stroke as a disease (ischemic or haemorrhagic) is reasonably the same all over the w o r l d . I t has an acute onset and is defined as rapidly developing clinical signs o f focal (or global) disturbance o f cerebral function lasting more than 24 hours w i t h no apparent cause other than vascular origin (Asplund, Tuomilehto, Stegmayr, Wester & Tunstall-Pedoe, 1988). L i v i n g w i t h the diagnosed disease is to be living w i t h an illness as a subjective, often stressful experience and a desire to be understood (Toombs, 1992, 1995; Söderberg, Lundman & Norberg, 1999). A severe stroke attack w i l l suddenly change the course o f a person's life story as w e l l as the story o f the people involved i n that l i f e story. The severity differs. The most dramatic symptoms can subside w i t i i i n the first f e w weeks. The dimension, position and cause o f the in jury w i l l influence the recovery. Researchers have found that people w i t h a stroke include an existential dimension i n their experience o f stroke. They regarded their

experience as an extremely distressing struggle to manage i n various situations in l i f e (Nilsson, Jansson & Norberg, 1999).

Unlike the acute onset o f stroke, Alzheimer's disease, being the most common dementia disorder, is characterised by a progressive deterioration o f the person's memory and thinking. Relatives have expressed i n retrospect that they had suspected f o r a long time that something was w r o n g and they were uncertain about the nature o f the diagnosis. (Garwick, Detzner & Boss, 1994; K i r k & Swane, 1996). According to D S M - I V ( A P A = American Psychiatric Association, 1994 pp. 134-143) people w i t h Alzheimer's disease are gradually affected b y cognitive deficits and impaired functions due to pathological changes that are slowly progressing i n structures o f the brain. The memory is prominently affected and the sufferers' ability to learn new things becomes impaired, or they forget previously learned things. The inability to use language (aphasia), a steadily decreasing ability to accomplish motor activities (apraxia) and difficulties i n recognising familiar things (agnosia) make i t d i f f i c u l t to interact and communicate w i t h others as well as manage daily caring matters. According to Norberg (2001) people w i t h Alzheimer's disease or other dementia i n advanced stages do suffer. This suffering can be understood as not feeling at home i n an existential meaning, but there is also the suffering o f being degraded that can be inflicted b y care.

L i v i n g w i t h severe stroke or Alzheimer's means l i v i n g w i t h various impairments i n perception and cognition. The person afflicted by a stroke may f i n d i t d i f f i c u l t to understand what has happened (Anderson, 1992) and can experience sensations o f 'not being the same' (Gustavsson, Nilsson, Mattsson, Å s t r ö m & Bucht, 1995; Jacobsson, Axelsson, Österlind & Norberg, 2000). People who are afflicted b y a stroke have not only difficulties i n handling their physical disabilities, but they also experience that the stroke attack challenges their whole being as a person (Nilsson, Jansson and Norberg, 1997; 1999). This indicates that people living w i t h severe stroke may need assistance to reconstruct their narrative identity as a person and to re-interpret their l i f e stories.

The person w i t h dementia experiences that the meaning o f the life-world alters during the course o f the disease (Nygård, 1996) and carers should make an effort to share an understanding w i t h the afflicted people about how they experience their situation (Kitwood, 1997; Wogn- Henriksen, 1997). Such sharing may be extremely difficult i f the afflicted person has severely impaired memory, cognitive functions and speech, influencing her or his capacity to express experiences and feelings in words (Arendt & Jones, 1992) and yet; the carers have to take over greater responsibility for decisions (Thomasma, 1984). Disturbed communication due to stroke also places special demands o n the carers' meeting w i t h the care receivers (Sundin, 2001, pp. 47-61) and calls f o r attention to the long-term psychological problems o f patients as w e l l their relatives (Santos, Farrajota, Castro-Caldas & de Sousa, 1999).

Dementia is referred to as a ' f a m i l y illness' as i t involves family members' support emotionally, socially and practically (Almberg, Jansson, G r a f s t r ö m & Winblad, 1998) and so does stroke (Anderson, 1992, p. 10). Relatives can be seen as significant parts o f a person's familiar, communicative context, when it comes to conversing and engaging i n shared dialogues (Jansson, 2001). Professional carers should be aware o f their task o f seeing to the relatives' need for information, counselling, and accessibility (Hertzberg, 2002, pp. 53-54; van der Duijnstee, Hamers & Abu-Saad, 2000; van der Smagt-Duijnstee, Hamers, Abu-Saad & Zuidhof, 2001).

Miesen (1992, 1993) suggested that people w i t h dementia function on t w o levels. On one level they are aware o f their situation and on the other level this awareness is missing. He further suggested that attachment behaviour gains increasing importance between elderly people w i t h Alzheimer's disease and argues that it is attachment w h i c h links older people to their environment, and attachment is vital i f human development is to continue. Attachment behaviour as described b y Miesen (1992, 1993) can be seen as similar to infants' attachment behaviour ( B o w l b y , 1973) and as a sign or code that carers who are sensitive see as a call for caring.

It is not only diseases that suddenly or gradually make us dependent on professional care. Almost half o f today's T h i r d W o r l d population lives i n conditions w i t h extreme poverty. The governments cannot cope w i t h the problems arising w i t h rapid urbanization. Because o f the breakdown o f extended f a m i l y structures and other supporting mechanisms the children i n these areas can be trapped i n cycles o f homelessness, under-education, drug addiction and despair. Some children do voluntarily run away f r o m the misery at such homes and others are left orphaned to live l i f e on their o w n at the bottom o f the status hierarchy. Girls living o n the streets are living a life that is hazardous f o r their health. Establishing a caring relationship w i t h these girls is a challenge. Most o f them have lost the trust i n adults; either they have no parents or they have run away f r o m home and most o f them have experienced that adults meet them as suspects i n general (Kilbridge, et al, 2000). This can make it d i f f i c u l t f o r professional carers to get inside these girls' network, and being left out may w o r k counter to caring.

Children living on the streets may have difficulties w i t h 'solving' developmental psycho-social conflicts. It can be d i f f i c u l t to f i n d mothers, parents or other significant others that are essential for this process as described by J. and E. H Erikson as (1982, 1988). They may also lack opportunities to participate i n constructive, story-telling activities i n order to develop a personal, socially accepted identity as described by, f o r example, Ricoeur (1992) and Ruud (2001, pp. 51-54). I t can also be assumed they have difficulties i n thinking about the future o f their l i f e stories or that they have little concern about the future as they are preoccupied w i t h getting hold o f daily necessities.

Reasonably, integrated values and caring praxis in relation to f a m i l y bonds and professional care influence our understanding o f living w i t h severe illness and meeting w i t h adversity in life throughout the l i f e span f r o m the perspective o f being an afflicted person, a relative or a professional carer.

Aims in the thesis

The overall aim of this thesis was to disclose the experience o f severe illness and caring w i t h a life-story perspective i n different cultural contexts.

In Paper I the aim was to describe the stroke-affected person's experience o f living w i t h stroke sequelae and their future expectations.

In Paper II the aim was to explore nurses' and relatives' experiences o f caring for stroke patients and to illuminate stroke victims' experience i n Northern Vietnam.

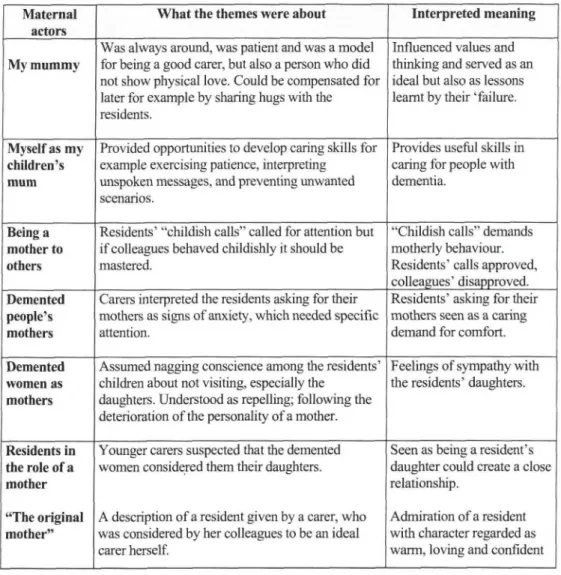

In Paper 111 the aim was to illuminate the thinking o f identified good dementia carers i n an attempt to make explicit attitudes and means o f communication embedded i n a seemingly good caring atmosphere and i n episodes narrated and interpreted as resulting in mutual understanding.

In Paper IV the aim was to illuminate individual skilled professional carers' ways o f achieving an understanding o f people w i t h moderate or severe Alzheimer's disease. In Paper Fthe aim was to elucidate the meaning o f caring f o r girls o f the street (GOS) as experienced b y female staff members w o r k i n g i n street children projects i n Eastern Africa.

P H I L O S O P H I C A L A N D T H E O R E T I C A L P E R S P E C T I V E

The five papers in this thesis are linked together on founding conditions, w h i c h I presume we share as healthy or seriously i l l humans, regardless o f age or where we live. M y choices o f philosophical and theoretical perspectives reflect four conditions. I have used them as pillar-stones for disclosing the meaning o f the experience embedded in seemingly diverse studies: our narrative identity; caring as the human mode of being; sharing an understanding of the meaning of our experience; and our praxis constructs our culture.

O u r narrative identity

M y understanding o f our identity as unique, speaking and acting persons is inspired by m y understanding o f Ricoeur's philosophy on people's identity (1992). Supported b y the grammars o f natural language he advocates that the term 'identical' has more than one meaning. The meaning o f 'identical t o ' may be equivalent to ' s e l f , but it may also mean 'same [as]'. For example a person can be identified b y her- or himself and b y others as M r s . Person, even i f some time has elapsed since last meeting and her understanding o f herself and others continuously changes throughout the course o f life. As humans we cannot think or talk about ourselves without involving others. We use narratives to seek our identity and connectedness i n life and to give sense and coherence to our lives. W e compare us w i t h ourselves and w i t h others. There is dialectic between the T as the same (idem=same) and T as the self (ipse) i n an existential meaning i n which a narrative identity is disclosed. Through telling stories and through listening to others' stories people develop both their individual and their collective identity.

Story-telling i n narrative dialogues is a means to order and to allow details, events, meanings as w e l l as history to be conveyed and reflected upon as whole stories (Cohler, 1991, p. 174; Maclntyre, 1993, p . 203; Polkinghorne, 1995; Ricoeur, 1992). M r s . Person may tell: "They found me unconscious i n the garden, and brought me to the hospital. That's where I found m y s e l f . . . " Such a story w i l l trigger o f f , or rather continue a

re-We share stories i n various relations. L i v i n g w i t h others and being related has also to do with the comprehensible w o r l d and what transcends it i n time and space and what people may believe transcends it (Buber, 1958; Roach, 1997). Relations beyond actual meeting might also influence us. Just thinking about someone may influence m y mood and contribute to a sense o f both o f us as true beings [that are] lived in the present (cf. Buber, 1958, p. 13, Buber's citation i n italics).

Presumably, we have a great influence on each other's narrative identity i n relations where we are involved i n each other's life stories over longer periods o f time. Members in a family and close friends have long-lasting, mutual emotional bonds and obligations throughout the 24 hours o f a day. They are likely to continue their involvement in each other's stories, continuously re-constructing the narrative identity o f each person and the family or group when a person instantly or insidiously becomes seriously i l l or cannot be cared f o r i n ordinary homes (cf. Herzberg, Ekman & Axelsson, 2001). Professional carers can also influence receivers and their relatives b y their participation i n the care-receivers' and their relatives' l i f e stories over a limited period o f time.

C a r i n g as the human mode of being

M y understanding o f caring as the human mode o f being is inspired by Roach, (1992), who has a Judeo-Christian background against w h i c h she explores caring. Caring i n her view can be actualised and manifested i n caring activities. She does not subordinate spirit to matter, but advocates that caring is k n o w n through the spiritual nourishment o f experience, expressed i n art (ibid, 1997). M y interpretation o f 'actualisation o f caring as a mode o f being' connotes the Swedish expressions ' b r y sig o m ' and van Manen's (2002) 'as-worry'. I n this view the person o f the carer affects and is affected b y the care-receivers and their relatives (Watson, 1988). I n the same way caring as manifested connotes the Swedish expressions ' v å r d a / ta hand o m ' . The view highlights that the desire to care is a human response to dependency and human values, not as something being valued b y me, but as something that includes sacredness o f human life and the preciousness o f the human being.

A globally well-known and familiar actualisation and manifestation o f caring as a human mode o f being is caring f o r children as the maternal relationship can provide a model for other relationships (Grimshaw, 1986). Ruddick (1989), as a feminist philosopher, claims an epistemological view on maternal thinking and practice i n that meeting the demands and adapting oneself to these demands i n maternal practice is founded i n reason that forms thinking, knowing, and a preparedness to create and retain reciprocal, trustful relationships. The practice forms a consciousness, w h i c h she names maternal thirddng. This can be seen as embodied knowledge (Benner, 1994, p. 52; 104-105).

According to Ruddick (1989) maternal practice involves a universal, unspoken but perceived demand f r o m infants w h o convey vulnerability and need o f care and protection. She further states like Roach (1992) that there is ethics involved i n responding to such demand. M y understanding o f this ethics is that it is a radical, silent, ethical demand, corresponding w i t h L ö g s t r u p ' s (1971, p. 59) v i e w on our human responsibility i n general - the other has to be served through word and action. And we must make this decision on the basis of our own selfishness and our own understanding of life. Carers who are a f f i r m i n g caring and perform caring actions as a response to the ethical demand can in some respects be compared to mothers' meeting w i t h their infants.

The main responsibility f o r establishing relationships between carers and the care receivers lies w i t h the carers. Professional carers as w e l l as 'mothers', regardless o f sex, are faced w i t h immediate unspoken and radical, ethical demands, which need not correspond w i t h what the care-receivers or their relatives express, i f they are able to talk. The carers are supposed to determine what to do and say i n caring situations as the care receivers' lives and well-being are i n their hands (cf. L ö g s t r u p , 1971, pp. 46-47).

Sharing an understanding of the meaning of our experience

M y understanding o f how it is possible to share an understanding o f the meaning o f our experience through language is also mainly inspired by Ricoeur (1976; 1993). The

meaning o f our experience (Ricoeur, 1976, pp. 15-16). The sensation o f understanding somebody or being understood i n a conversation exceeds the words, expressions and language that are used. When we meet and talk w i t h each other there are characteristics that are not present i n written document, even i f such documents convey a meaning that we interpret. We use sounds and actions, besides expressing words and sentences, and we influence the emotions o f each other (Ricoeur, 1993). These w i l l guide our intention to understand and to be understood as the use o f spoken language can produce a mutual understanding o f sameness of the shared sphere of meaning (Ricoeur, 1976, p. 73). Ricoeur (1976; 1991) makes a distinction between language as a closed system providing codes and words f o r communication and language as an event when we are using the words f o r exchanging messages (Table 1). Language as system is composed o f single letters, signs or words ( = codes) that are neither true nor false, and they lack temporality. The function o f this system is to provide people w i t h codes to be combined i n a communication. Language as discourse requires a synthesised connection o f words i n sentences to carry messages that are meant b y someone and are orgamsed as stories. The sense o f the meaning proceeds f r o m integration o f the parts to larger wholes that always are about something (Ricoeur, 1976, p. 7).

Table 1. Language as system and as used i n discourse (Ricoeur, 1976; 1991).

Language as system Language as used in discourse

Basic unit Sign or word (=code) Sentence

Function Provides the codes for communication

Provides a world for exchanging messages

Relation to user Lacks subject

Collective

Anonymous and not intended

Refers to a speaker Individual

Intentional and meant by someone

Relation to time Lacks temporality.

Elements set in contemporaneous time (synchronic system)

Realised temporarily in the present, but presented as temporal events in succession = a story over time (diachronic dimension)

Exists as A compulsory, virtual system for a given speaking community

Personally decided opinions (= arbitrary) that depends on what is happening or the circumstances at hand (= contingent)

Appearance in science

Finite signs and sets to be investigated and described as homogenous objects within semiotics

Descriptions that can fall under many sciences.

People's meetings enable experiences to be shared, not only through verbal communication, but also as sensations o f understanding each other's experience (Buber,

1972, p. 3). Caring f o r infants may serve as an example. Stern (1985) suggested that there was 'affect attunement' between a mother and her infant i n their communication w i t h each other. Their understanding o f each other's experience through verbal language is not possible, but it can be understood as an influence o f the oral discourse and the actions on emotions and affective attitudes (Ricoeur, 1976). Through use o f imaginations i n narratives about the child's past and its future, the mother can anticipate suitable actions to be tried in order to satisfy the child and herself {cf. Ricoeur, 1991, pp. 168-181).

The meaning o f our experience is often conveyed i n a language o f metaphors (Ricoeur, 1976, pp. 51-52). When using metaphoric language we compare our experience w i t h concrete matters as our conceptual system o f m m k i n g and acting is fundamentally

symbols have a non-semantic side that resists transcriptions, whereas a metaphor {ibid., 1993, pp. 38-39; 1976, chap. 3) is a semantic innovation. A metaphor conveys new meaning through productive imaginations, has emotive values and offers new information, but has no status i n established language. It should be seen as having one o f the emotive functions i n a discourse as the words we use can have different meanings and functions i n different contexts.

Beloved relatives and skilled professional carers are at times caring for people i n vulnerable situations, who are disabled or unable to use language. It can be assumed that these carers are sensitive to signs shown and single words expressed by the care receivers. Productive imagination can assist them to put these signs and words {cf. Ricoeur, 1991, pp. 168-174) into integrated wholes o f stories that are brought into comprehensive language as meant by the care receiver.

O u r praxis constructs our culture

M y understanding o f culture as being constructed through our unending activities is inspired b y Bauman (2000) and Ricoeur (1992). Together w i t h others we create our identity that gives meaning to the T as a unique being. Our social identity guarantees that meaning and gives meaning to the ' w e ' as being included and accepted w i t h i n a face-to face network. There is a context to which we belong and feel secure (Bauman, 2000, introd.; Ricoeur, 1992). Being 'inside' such a network is described b y Bauman (2000, p. x x x i i i ) as 'being at home'. Being 'outside' means being i n a space that contains things one knows little about, one from which one does not expect much andfor which one does not feel obliges to care {ibid., x x x i i i ) . The same author (2000, chap. 1) claims that i n Western mentality 'culture' is often understood as a hierarchical concept i.e. a 'cultured person' is w e l l educated, polished and above a 'natural state' contrasting w i t h an 'uncultured person'. It is also used w i t h a meaning o f difference between various groups o f people and nations. He suggests a generic understanding o f 'culture', connoting an ongoing process whereby people structure the w o r l d through their use o f tools and

language. The sfructuring activities constitute human praxis; the human mode o f being i n the w o r l d . Bauman's (2000) view on culture as praxis seems to correspond w i t h Ricoeur's (1992) view on people's narrative identity and the development o f practical wisdom: It is through public debate, friendly discussions, and shared convictions that moral judgement in situation is formed (ibid., p. 290). I also see it embracing mothering as praxis ( H o l m , 1993) and caring as the human mode o f being (Roach, 1992). The required strength o f our identity w i l l not come b y itself. It must be created i n a culture where there is education, teaching and training (Bauman, 2000). A n epistemological view (Ruddick, 1989) on maternal tWnking and practice adds an important dimension to one way o f understanding how knowledge about care is achieved.

M E T H O D O L O G Y

The studies i n the thesis had a qualitative approach w i t h the intention o f understanding more about the meaning o f the experiences o f severe illness and o f caring. The choices o f methods and the application o f them, were discussed and agreed upon w i t h the co-authors o f t h e papers. Generally, the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur's (1976; 1991; 1992; 1993; 1994) writings on the nature o f language and meaning, o f action, as w e l l as o n interpretation and subjectivity have been inspiring throughout the work.

Ricoeur (1993, pp. 114-115) advocates that meaning is an ontologicai, phenomenological question that presupposes hermeneutics as the meaning is concealed. People's experiences are not objects that can be studied as such, neither can they be conveyed f r o m one person to another, but the meaning o f experience can be shared i n narrative dialogues. Such dialogues w i t h a sense o f being together can make it possible to achieve a mutual understanding o f sameness o f t h e shared sphere o f meaning o f t h e experience i n question (Ricoeur, 1976) f o r example o f living w i t h the experience o f stroke and o f caring.

Narrative dialogues can be established i n narrative interviews as a means to collect data for investigating the meaning o f peoples' experience. Narrative is the f o r m that people spontaneously use to formulate and to create meaning i n their life experiences (Polkinghorne, 1988, p. 183). The interviewer as a researcher has to be aware o f the mutual influence sounds, actions, words and sentences used during the interview have on emotions and the affective states (cf. Ricoeur, 1976, chap. 1). The awareness can assist the interviewer to use signs, gestures and words to stimulate the interviewee's narration and to give further explanation. It is the responsibility o f the researcher to change the direction o f the discourse i f focus is lost.

The transcribed text f r o m audio-recorded, narrative interviews is seen as grounded in the objectivity of meaning of oral discourses (Ricoeur, 1976. p. 91). Also meaningful actions can be objects for science under the provision that they are f i x e d as discourse (Ricoeur, 1991, pp. 150-152), f o r example observed actions can be reflected o n i n narrative interviews at a later stage. The meaning that is present i n the oral discourse and actions

can be understood in a dynamic reading o f a text that is transcribed verbatim f r o m audio recorded interviews. Every text w i l l involve several potential horizons o f meaning that can be actualised during the interpretation process. (Ricoeur, 1976).

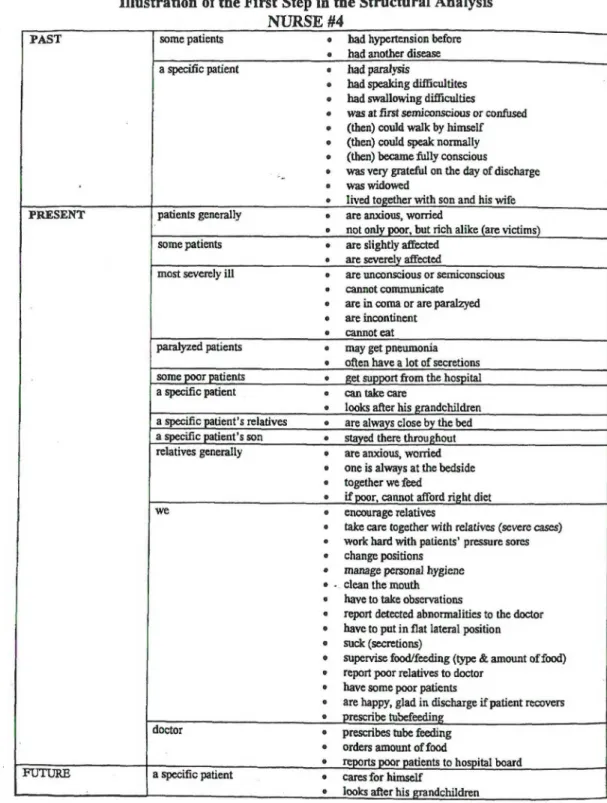

The dynamic, interpretation process o f a text should, according to Ricoeur (1976), f o l l o w a path o f three stages in the dialectic o f explanation and understanding. Initially, the meaning i n the text is seen as something whole that can be grasped i n a naive understanding and guesses about structures i n the text can be made. The guessed structures are then looked f o r and thoroughly 'mapped u p ' . I f the guessed structures cannot be f o u n d or they contradict the meaning grasped i n the naive reading, the latter has to be scrutinised and a new naive reading has to be performed. A t this stage the text is like any object that can be looked at f r o m several sides, but only one side at a time i.e. each structure must be looked at separately. The finalising stage is to comprehend the understanding in the naive reading and the explanations f o u n d in the structural analyses together i n a comprehensive, critical understanding o f the meaning as a whole. This is an appropriation o f the meaning o f the text itself as an existential matter that must not be mistaken f o r an understanding o f the inner life o f the informants or o f the researchers. The whole process should instead provide a disclosure o f a possible way o f looking at things and a new mode o f being.

The guesses made i n the process cannot be validated through logic or empirical verification, but through presentation o f good arguments for a most probable and qualitatively best-construed verbal meaning f o u n d i n text. The guesses i n the naive reading are not validated as logical verification through structural analyses, but as arguments i n favour o f the understanding that is presented. There is no validation o f what the interviewees intended to tell, as the intention o f the interpretation is to f i n d the meaning that is embedded i n the transcribed text. I suggest that this interpreted meaning i n a text can be conveyed i n a language o f metaphors, as this language, according to the author is an integrated part o f our conceptual system o f Ihinking, talking and doing that goes to the depths o f human experience.

The approach to analysing data as inspired by Ricoeur's (1976) is under development f o r use i n nursing research. I t has been used for interpretation o f transcribed interviews among others by researchers at the Department o f Nursing, U m e å University, Sweden (e.g. Rasmussen, 1999, p. 46; Söderberg, A : 1999, pp. 18-20; Söderberg, S., Lundman & Norberg, 1999) and the Department o f Nursing and Health, University o f T r o m s ö , Norway (e.g. Talseth, Lindseth, Jacobsson & Norberg, 1999).

Pre-understanding1

In order to hold some assumptions and suppositions at bay (van Manen, 1990, pp. 46-51; Öhrling, 2000, pp. 28-30) I have made an effort to make explicit some o f the pre-understanding that may have influenced data collection, the findings i n the five papers and the summary o f them. I am aware that such knowledge is doomed to remain partial (cf. Ricoeur, 1993, p. 245).

M y personal experience o f caring emanates f r o m being cared for i n t w o foster homes as a 'Finnish child o f the w a r ' w h o has given an understanding o f being involved i n a f a m i l y ' s network as 'being one o f us' at times, but also o f not being f u l l y involved, w h i c h the paradox 'being just as one o f us' expresses. The experience also includes being cared f o r by beloved relatives and friends. A s an adult I have been involved i n a f a m i l y w i t h three boys and later on in their families w i t h four grandchildren. I have also experience o f caring for elderly relatives at the end o f their lives. The years o f practising care as R N , Public Health Nurse and o f teaching nursing care as a Nurse Tutor on different levels as well as i n different countries have contributed to m y pre-understanding o f caring i n different cultural contexts. However, the main contributor f o r studying nursing research was my husband's severe stroke attack.

1 The concept pre-understanding is amongst others used by the phenomenological researcher van Manen (1990, pp. 46-51). He advocates making the researcher's

•common sense' pre-understanding explicit. The concept is used by Ricoeur (1993, pp. 243-247) to denote that all objectifying knowledge is preceded by a relation of belonging on which we arc unable to entirely reflect, but it can be constituted in relative autonomy through dislanciation. It is always partial, fragmentary. The

non-completeness is hermeneutically founded, and concerns the coirect usage ofthe critique of ideology as a task that must be begun but can never be completed

I spent several months at his bedside as he underwent various, severe complications. During that time I often wondered what 1 should have done i n many o f the delicate situations that occurred, had 1 been a practising R N . I also questioned what m y colleagues and I taught the RN-students and the EN-students i n order to prepare them f o r these complex and d i f f i c u l t situations.

I got the impression that most carers just d i d their duty i n a correct and polite manner; but there were some f e w w h o draw m y attention i n a positive way and they made me confide i n them2. I t was their way of being, more than the uttered words, that made me feel that

they shared an understanding o f our situation. These nurses' understanding, as I sensed it, constituted their platform f o r their performance o f skilled care. N o t only did we appreciate their presence; I admired their skills, including their handling o f the sophisticated technical equipment. These carers significantly contributed to m y understanding o f good care. I presumed that these skills were anchored i n their thiriking, knowledge and experience and I assumed that their talents were experienced and appreciated b y other patients, relatives and their colleagues.

These carers supported m y involvement i n the whole situation and they assisted me and us together to endure the several serious complications that came along. W h e n I was mentioned as a 'visitor' by some other staff, I felt strong objections towards being regarded as a 'visitor'. I felt inseparably involved i n whatever happened to m y husband. A frequent use o f the concept 'visitor' contrasted sharply against the experience I and the f a m i l y had f r o m w o r k i n g i n developing countries. Memories f r o m four years i n Zambia, where the extended f a m i l y system worked at that time, had taught us lessons about relationships between people, family bonds, and o f respecting elderly people as having acquired ' l i f e skills'. A student nurse asked me as lecturing tutor: " W h o is teaching your children to live?" This question still remains, challenging that an answer be formulated, but I sense that it influences m y understanding o f the meaning o f caring. Also, memories o f a couple o f years i n Vietnam recalled scenes w i t h at least one relative at the bedside i n

a hospital throughout the twenty-four hours o f the day. I had been told that: "For us Vietnamese people it is more important to be alive socially than to die physically". The saying seemingly conveys an important message about people's living i n relations.

M y interest i n language, i n its broadest sense, may have been influenced b y memories o f arriving i n Sweden and not being able to understand and to make myself understood. This situation was repeated fifteen years later when I met m y biological mother and m y sisters. I spent some days w i t h a sister without having a verbal language i n common, but I felt convinced that we shared a meaning o f several experiences through use o f gestures, signs and some expressions.

Material and method

The research settings f o r collecting data varied i n cultural contexts (cf. Leininger, 1985, pp. 7-12 and 1991, chap. 1). Purposive samples o f people w i t h a stroke, relatives and professional carers were selected (Table 2) and the informants were approached w i t h ethical considerations before, during and after collecting the data. A phenomenological hermeneutic method as described before was used f o r analysing the data.

Research settings

The choice o f settings started w i t h investigations o f l i v i n g w i t h stroke sequelae i n Northern Sweden, which was a familiar context (I). A hospital, built and supported by Sida during the 1980s and 90s i n Northern Vietnam, was chosen as a suitable setting f o r further investigation o f people's experience o f stroke. I t was assumed that the prevailing traditional values w i t h strong f a m i l y bonds could influence the experience o f stroke ( I I ) .

Six women and one man resided i n the chosen group dwelling f o r people w i t h dementia. Five selected professional carers' interaction was studied w i t h five o f the residents, the man included. These residents were investigated and diagnosed w i t h Alzheimer's disease b y a specialist prior to moving into the dwelling. Their mental ability as estimated by the primary carers w i t h the help o f a ' M i n i - M e n t a l State' test protocol ranged f r o m 0 to 21

(Folstein, Folstein & M a c H u g h 1975) ( I I I , I V ) . Ten enrolled nurses ( E N ) w i t h varying educational backgrounds worked part-time in shifts during daytime and t w o nurse aids ( N A ) were on night duty between 9 P M and 7 A M . One additional E N supervised the staff at two similar group dwellings. A l l but one carer had worked i n the d w e l l i n g since it was established f o u r years prior to this study ( I I I , I V ) .

East A f r i c a was k n o w n to be a society i n transition influencing f a m i l y bonds, w h i c h was assumed to influence professional carers' experience o f caring f o r girls l i v i n g on the streets, w h i c h was a comparatively new phenomenon i n this area ( V ) . The setting f o r these interviews was at the different non-governmental organisations' ( = N G O ) project offices in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania (Table 2) ( V ) .

Table 2. The five papers' geographical area, subjects, context and methods o f data collection. Number o f subjects, interviews and observations are given i n brackets.

Geographical area

(Paper No)

Subjects (No) Context of data collection (No)

Method of data collection (No) Northern Sweden (I) Post-stroke patients (29) Private homes (27) Institutions (2)

Projective, individual interviews (29)

II Northern Vietnam (II) Post-stroke patients (5) Relatives (5) Nurses (5)* Hospital (3) Private homes (2) Private homes (2) Hospital (3) Hospital (5) Individual interviews (15) Northern Sweden

(in, iv)

Carers (5)* Carers (5)* Carers (5)* and their colleagues (6)*Group dwelling for people with dementia (all)

Individual interviews (5) Observations (25)

Reflective, individual interviews after observation (25)

Group interview (1) Group interview (1)

V East Africa Female carers (13) Offices of NGOs (5) Individual interviews (7) Group interviews (2)

Informants

Totally 73 informants contributed i n the studies w i t h data; 34 people thereof had experience o f living w i t h a stroke, f i v e o f being caring relatives, and 29 informants had experience o f professional care. I n addition, five residents i n the group dwelling contributed w i t h contextual data as the professional carers' interactions w i t h them were observed. The focus f o r these observations was on the carers (Table 1).

Ten women and 19 men between 60 and 91 years o f age participated i n a f o l l o w - u p study 18-22 months after a stroke attack. These informants had had eating problems during the acute stage. They also had remaining neurological sequelae at a 12-month medical check-up (Axelsson, 1988) ( I ) . T w o women and three men aged 28, 31, 54, 60 and 65 o f age participated i n Vietnam ( I I ) . Their caring relatives, identified at the time for the interview were: a younger brother (27 years), mother (60 years), younger sister (51 years), w i f e (48 years), and sister's son i n law (39 years) (II).

Five Vietnamese RNs between 27 and 35 years o f age w i t h three to four years o f nursing education and seven to twelve years o f nursing experience were included ( I I ) . Five professional carers i n the selected group dwelling for people w i t h dementia were identified by their colleagues and themselves as being good at understanding people w i t h Alzheimer's disease. They were married women w i t h children, aged 29, 33, 4 1 , 47, and 55 years respectively. T w o had ten weeks o f nursing education as nurse aides and three ENs had about t w o years o f nursing education. Their caring experience ranged f r o m ten to 27 years (Median = 14 years). Eleven o f the totally 13 possible carers i n the dwelling participated i n a final group interview; one was on sick leave and one had been on night duty ( I I I , TV).

Transcribed text f r o m 13 female informants aged between 20 and 45 years was selected f r o m interviews w i t h a total o f 17 females and 20 males. The selected text was identified as 'saying' something about female professional carers' experience o f w o r k i n g among girls living on the streets. Five o f the selected carers worked i n projects where the girls resided i n institutions. M o s t o f them had children, all o f them had more than t w o years o f

experience o f w o r k i n g among girls and three o f them had a formal education i n social work.

Ethics

The benefits o f collecting data f o r these studies were judged to be greater than the risks for the participants. A l l the participating informants were informed about the a i m o f the studies and the method f o r the data collection. They were also told that they could refuse participation and could withdraw at any time, as w e l l as reassured that refusal or withdrawal w o u l d not affect their treatment, care or working conditions. They were assured o f confidentiality and asked to give their informed consent to participation, and they were made aware o f the applicability o f the studies ( W M A , 2002). The Ethical Committee, U m e å University, approved the written plans o f the projects before the data collection began.

I participated i n analysing the data without further information about the informants i n order to keep the ensured confidentiality (I).

As the residents i n the group dwelling f o r demented people were unable to give their informed consent to having the project carried out i n their 'home', their relatives were approached and informed i n w r i t i n g ( I I I , I V ) . They gave their informed consent by telephone. A n effort was made to minimise the disturbance o f m y appearance on the homely atmosphere i n the dwelling. I got advice f r o m the carers that seemed to suit the described 'semi-participant' observations. The interviews w i t h the carers were performed w e l l out o f the residents' sight and hearing. I tried not to look as a newcomer each time I appeared; f o r example I wore the same clothing every time. I also adopted the carers' way o f not greeting each other o n arrival, but rather meet w i t h the residents. I was also told not to say goodbye on departure, as that was k n o w n to make residents wonder i f they also were supposed to leave. D u r i n g the observations I never entered the toilet w i t h the subjects, but remained outside. During analyses and i n the presentation o f findings the participants appeared w i t h given names and the only residing man was given a woman's