CITIZEN PERCEPTION OF

PRIVATE SECURITY GUARDS IN

MALMÖ

TOBIAS BENGTSSON

Degree project in criminology Malmö University

61-90 hp Faculty of health and society

May 2015 Department of criminology

2

ALLMÄNHETENS UPPFATTNING

AV VÄKTARE I MALMÖ

TOBIAS BENGTSSON

Bengtsson, T. Allmänhetens Uppfattning av Väktare i Malmö. Examensarbete i kriminologi 15/30 högskolepoäng. Malmö högskola: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle, institutionen för kriminologi, 2015.

Trots en markant ökning av vaktpersonal i privat regi under de senaste decennierna finns det inte mycket empirisk forskning om allmänhetens uppfattning av väktare. I detta arbete undersöks malmöbornas tillit till och tillfredställelse med väktare och syftet med studien är att får en inblick i

allmänhetens inställning till vaktpersonal. Enkäter delades ut i Malmö med frågor angående upplevd tillit till väktare, tillfredställelse med väktare samt frågor om respondenternas uppfattning av väktares professionalitet, ansvarskyldighet,

framställning och artighet. Urvalet bestod av 78 respondenter och resultaten tyder på att den allmänna uppfattningen av vaktpersonal är mer positiv än negativ. Upplevd professionalitet hos väktare påverkade tillit till väktare och upplevd artighet hos väktare påverkade tillfredställelse med väktare. Hur man upplevt väktares beteende vid personlig kontakt visa sig påverka uppfattningen av både tillit till och tillfredställelse med vaktpersonal. Studier om allmänhetens

uppfattning av vaktpersonal kan användas i utbildande syfte för vaktbolag för att påverka väktares beteende och agerande mot allmänheten. Ökad kännedom av allmänhetens inställning till vaktpersonal är även relevant för politiker i deras ställningstagande av framtida reglering av den privata säkerhetsindustrin.

Nyckelord: privata vaktbolag, väktare, allmänhetens uppfattning av väktare,

3

CITIZEN PERCEPTION OF

PRIVATE SECURITY GUARDS IN

MALMÖ

TOBIAS BENGTSSON

Bengtsson, T. Citizen Perception of Private Security Guards in Malmö. Degree project in criminology 15/30 högskolepoäng. Malmö University: Faculty of health and society, Department of criminology, 2015.

Despite the rapid increase in private security guards in recent decades, little is known about citizens’ perception of security guards. In this paper citizens’ trust and satisfaction with security guards is assessed. The aim of the study is to get an insight into citizens’ perception of private security guards in Malmö. Paper and pencil surveys were distributed in Malmö with questions regarding perceived trust and satisfaction with security guards and about security guards’ professionalism, accountability, imagery, and civility. The sample consisted of 78 respondents and the findings suggest that the overall perception of security guards was more positive than negative, however, the results were largely mixed. Perceived professionalism predicted satisfaction with security guards and perceived civility predicted trust in security guards. Also, security guard behavior while interacting with the public was a strong predictor of both trust and satisfaction with security personnel. Results from this study and similar studies can be used by private security organizations to educate staff in order to improve the public perception of security guards. It may also be useful for policy makers in order to make more educated decisions about future regulation of the private security industry. Keywords: Private security, security guards, citizen perception of security guards, citizen trust in security guards, citizen satisfaction with security guards, Malmö.

4

Contents

Background/introduction ... 5

Purpose of study ... 6

Research questions ... 6

The emergence of private security ... 7

Private security in Sweden ... 8

Reasons for criminological interest in the private security industry ... 9

The relevance of public perception ... 11

Citizen perception of law enforcement ... 13

Former research ... 14 Methodology ... 17 Sample ... 18 Dependent variables ... 18 Independent variables ... 18 Analysis ... 19 Cronbach’s alpha ... 19 Data treatment ... 20 ANOVA ... 20

Ordinary least square ... 21

Ethical considerations ... 21

Results ... 21

Descriptive variables ... 21

Contact variables ... 22

Findings on citizen’s perception of security guards ... 23

Analysis of variance ... 25

Ordinary least square ... 27

Discussion and Conclusion ... 28

Results ... 29 Limitations ... 31 Future research ... 32 References ... 33 Appendices ... 37 Appendix 1. ... 37 Appendix 2. ... 38 Appendix 3. ... 40

5

BACKGROUND/INTRODUCTION

This paper is dealing with the private security industry, which is gaining increasing financial strength, political power as well as an increased public presence. The private security industry is a multi-billion euro industry, hiring hundreds of thousands of people worldwide and the sector is projected to grow steadily in the years to come (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007; Krahmann, 2011; Wakefiled, 2003). In Europe alone the total yearly turnover of the industry was 35 billion euros in 2011 and in that same year the total number of security companies in Europe was 52 300 (Confederation of European Security Services, 2011). In addition, the average market growth per year was 13, 5 percent between the years 2005-2011 (ibid.).

For the first 150 years of policing, the state police was the only actor providing security to the public. However, over the past 50 to 60 years the world has experienced a massive increase in private security solutions (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2009; Gill & White, 2011; White, 2012). Europe and most of the western world has according to Wakefield (2003) felt a greater demand for security and also a declining faith in law enforcements’ ability to prevent crime (Wakefield, 2003). This has led to a diffusion of formal social control (ibid). In this paper social control refers to organized responses to crime, delinquency, and other forms of deviant and socially problematic behavior, which is Stanley Cohen’s interpretation of the term (as cited in Wakefield, 2003). Additionally, private security has become a prominent actor in the field of policing, resulting in a rapid increase in employment of security guards on a global scale (Wakefield, 2003). Policing and governance of security has therefore become more

decentralized. Private security officers are also becoming more police-like in their responsibilities and the uniforms of many companies in the sector resemble those of the police (Button, 2007).

However, the expansion of private security has not occurred without public resistance, despite the fact that there seems to be a greater demand for security in society (Wakefield, 2003; Button, 2007). Since the police historically have had a monopoly on policing, the increased presence of private security measures and the

6

public/private collaboration have been criticized in several societies (Button, 2007).

In order to make the transition of social control smoother and to increase their own authority, private security organizations tries to create strong bonds with the police (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007). This is also to influence societal norms regarding private security and the increased presence of security guards. One common strategy to close the gap between public and private among private security organizations is to openly hire former police officers as well as former military personnel (ibid.).

In this paper the private security industry refers to companies and organizations that have security guards, alarm systems, closed circuit television cameras (CCTV), risk management, and risk consultancy as their main products and services (Abrahamsen & Williams 2009). The costumer base of these

organizations consists of national and international organizations, governments, and private citizens (ibid.). Wakefield (2003) makes a distinction between ‘manned’ security services and the provision of security hardware services. The latter refers to technological security solutions while the former refers to the provision of security guards (ibid.). The focus in this paper, however, will be on the ‘manned’ or ‘staffed’ security services since citizens’ satisfaction and trust in security guards is what will be assessed.

Purpose of study

The purpose of this study is to assess the public opinion of private security guards in Malmö. The aim is to get an insight into the level of satisfaction and trust citizens in Malmö have of private security guards.

Research questions

What level of trust and satisfaction do citizens in Malmö have of private security guards?

Which factors affect the level of perceived trust and satisfaction with private security guards?

7

The emergence of private security

Relatively few criminologists have focused their research on the emergence of the private security industry. Most research related to the topic has been directed to the private military aspect of these companies, which is likely due to the highly political nature of the topic (Zedner, 2007).

For the social scientists that have focused on the phenomenon, political and economic factors have been in the center of the debate. The fall of welfare states across the western world and the decreased investment in the public sector has according to White (2011) resulted in a security vacuum that the police could not fill. During the 1970 s and the 1980s many advanced democratic states did, due to financial constraints on public spending, no longer keep up with the demand for domestic security. White (2011) explains that the public demand for domestic security was driven by increasing crime rates, which resulted in a security deficit. This supply deficit or security vacuum was filled by private security companies (Button, 2007; White, 2011). Also, increased individualism in society, which encourages individuals to provide their own security to a larger extent, has been stressed as a contributing factor to the expansion of the sector (Button, 2007). Abrahamsen & Williams (2007) describe an important global shift in the way societies view crime. During the 1970s the attitudes and norms regarding crime were that it was a product of poverty and the social environment. This “welfarist” view of crime started to change in the 1980s and was replaced by a more

“economic” view of crime, which focused more on rational calculations by the criminal as well as the opportunity to commit crime. These changes in norms and crime policy have been crucial for the rapid expansion of the private security sector (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007).

Berndtsson (2011) and Krahmann (2011) associate the expansion of the sector with Ulrich Beck’s theory of the risk society in which the society produces new technology as well as greater risks. Beck’s theory describes both actual and perceived risks, both of which are capitalized on by private security companies. The sense of greater risks in society encourages private citizens, governments, and businesses to discuss, calculate and strive to mitigate risks to a larger extent (ibid.). In this type of society security expertise and security guards working with

8

risk mitigation are of great importance. According to Berndtsson (2011) private security is where an increasing number of organizations, governments and private citizens turn to with the objective of mitigating risks. Abrahamsen & Williams (2007) explain the growth of private security largely by the sector’s unique ability to create its own market. By reminding people of the risks, both actual and

subjective, private security companies create a demand for security- expertise, personnel and technology (Abrahamsen & Williams 2007; Berndtsson; 2011; Krahmann, 2011; Wakefield, 2003). Krahmann (2011) refers to this as the industry advertisement of fear.

Additionally, according to Abrahamsen & Williams (2007) and Wakefield (2003) property rights have gained greater social power and this has been beneficial for private policing both regarding their authority as well as their financial gain. Competition in the industry together with increased efficiency and globalization of the flow of capital has made a transnational expansion possible. It is mainly the larger actors in the sector that move to the international market (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007; Abrahamsen & Williams, 2009; Button, 2007; Wakefield, 2003) The larger private security organizations have due to their size, resources, and economic growth become important actors in the nations in which they operate. Their economic importance has also resulted in political influence (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007). The largest private security firm in the business

Group4Secure (G4S), operates in 120 countries and has a total of 618 000 employees (Group4Secure, 2015). Not only is G4S the largest company in the business, it is one of the largest private employers in the world (ibid.).

Private security in Sweden

According to the confederation of European security services (CoESS), the number of security guards in Sweden in 2010 was 20 000 and there were 250 private security companies operating in the country (Confederation of European Security Services, 2011). The same year CoESS reported that the private security sector has more employees than the state police in Sweden. The ratio of security guard per population in 2010 was 1/467, whereas the ratio of police officer per population was 1/552 (ibid.). Considering the annual growth of the sector, which has ranged between an increase of five and seven percent per year over the last ten

9

years, there is reason to believe that security guards outnumber police officers in Sweden by an even greater margin in 2015 (ibid.).

However, it is problematic to find accurate and reliable statistics about the private security industry (Van Steden & Nalla, 2010). It is a sector with fierce

competition and many organizations are due to commercial reasons hesitant to disclose information about their number of employees, turnover, and their market share (ibid.)

Sweden’s private security sector is regulated by the Security Companies Act, which was enacted in1974 (Svenska stöldskyddsföreningen, 2008). The areas of the sector which are specifically covered by law are general guarding, airport security, cash-in-transit, maritime security, and monitoring and remote

surveillance (ibid.). The law was passed in order for the government to ensure a certain standard of performance by private security companies. Therefore the police administrative board regulates the industry and the county administrative board supervises the industry regarding approval of the authorization of security personnel, training/education, equipment, and uniforms (ibid.).

Reasons for criminological interest in the private security industry

As mentioned earlier, considering the growth to date, the projected continued growth as well as the increased presence of the private security industry in society, it ought to be a field of strong criminological interest, especially

regarding situational crime prevention. Nonetheless, criminologists have largely disregarded research of private policing, as Wakefiled (2003) puts it;

“While private security is no longer a subject that languishes on a forgotten scholarly back burner, it remains surprisingly under-researched”

(Wakefield, pp: xvii, 2003).

Furthermore, the shift in security norms and the rapid expansion of the private security sector calls for a change in the way criminologists and other social

scientists view crime prevention and crime control (Zedner, 2007). Security norms have shifted towards more individualism, where the public to a larger degree is empowered to secure their own interests (Button, 2007; Wakefield, 2003; Zedner,

10

2007). Regardless of philosophical or political view of the increase in security officers in particular, and expansion of the private security sector in general, the average citizen is equally as likely, if not more likely, to come in contact with private security guards as police officers (Moreira et al, 2015). Zedner (2007) discusses the issue further by problematizing whether criminology, which generally can be considered a post-crime discipline, can adapt to a world that to larger extent focuses on security, and what can be referred to as a pre-crime society. In a post crime society the society tends to react to the crime after it has occurred (ibid.). Conversely, in a pre-crime society the aim is to foresee and prevent crime before it has occurred. Thereby calculations, risk assessments, and surveillance are relevant aspects of the pre-crime society (ibid.). In this type of society security is a product or a service that can be sold for a profit on an open market, and is generally provided by the most efficient actors in the field (Abrahamsen & Williams 2007; Zedner 2007; Wakefield, 2003).

There are, however, branches of criminology that focus on situational prevention, which are adapted to what Zedner (2007) refers to as the pre-crime society. Various criminological theories deriving from rational choice theory are intended to deter offenders from crime before the crime has occurred. Routine activity theory, which was developed by Felson & Cohen (1979), is one of them.

According to the theory, crime will not occur unless there is a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the lack of a capable guardian (ibid.). Since capable

guardians can be for instance police officers, security guards, alarm systems, and CCTV cameras the theory is highly compatible with the trends in crime policy. It is important to stress that situational prevention is attractive to implement by policy makers, since it is often viewed by the public as a hands on tactic to decrease criminal activity (Cornish, 1993). Many other criminological theories focus on indirect factors or background factors of crime, such as poverty, which are often more difficult to influence by policy makers.

These trends in crime policy have made the field of policing more proactive, which in turn has created vast opportunities for private security and the implementation of security guards. Thus criminology as a scientific discipline should analyze crime prevention and formal social control in the context of contemporary societies, in which private security plays an increasing role.

11 The relevance of public perception

The expansion of the private security sector and the global increase in security guards has not occurred in a social vacuum. The private security industry does not have an ideal reputation, regardless of their rapid growth and financial success (Van Steden & Nalla, 2010). The competence of security guards has often been criticized and their profession is regularly portrayed as low paid and inadequately trained (Hart & Livingstone, 2003; Van Steden & Nalla, 2010). According to Hart & Livingstone (2003) the occupation is also portrayed as tainted with corruption and poor performance. Critique of this nature is frequently brought up in studies of the qualities and shortcomings of security guards and the private security industry (Van Steden & Nalla, 2010).

Furthermore, Moreira et al (2015) describe an overall negative description, and a negative stereotype of private security guards in the media and by popular culture. This certainly affects the image of security personnel negatively. Additionally, investment in private security solutions is largely considered to be driven by low prices instead of high quality and this may also have a negative effect on the status of security guards (Goold et al, 2010; Mulone, 2013). In order to gain more knowledge regarding societal norms of security officers, it is of great relevance to research citizens’ perception of private security officers and possible reasons why the public has certain perceptions of the profession.

In the security industry, authority is central to effective performance and the authority of an industry has an effect on the regulation of the industry (Button, 2007; Hart & Livingstone, 2003; Moreira et al, 2015). Authority is not something that can be created by the security industry itself and neither can policymakers directly create authority for an industry. Instead it is created in relation to public norms (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007).

“This view of authority takes account of its socially constructed nature, that is, its dependence on an audience or society whose norms and values recognise certain persons, institutions or statements as authoritative. In this way, authority

12

Thus private security organizations can benefit from more precise knowledge of the way the public view security guards. Negative opinions about their work may result in lower authority and status in the eyes of private citizens. This can have negative effects on legitimization of the private security sector as a whole.

Moreover, data about citizens’ perception of private security guards is highly relevant for governments since they are the regulators of the private security sector and also a customer (Moreira et al, 2015; Van Steden & Nalla, 2010). Due to the fact that governments do contract private security officers, the industry plays an increasing role in protecting public interests. In addition, policy makers must have a sense of the public opinion regarding security guards due to their increased presence and increased contact with citizens (Moreira et al 2015). With a clearer picture of citizens’ confidence in security guards, more effective

decisions can be made regarding for example the regulation of private security (Shearing et al, 1985).

Also, one should not forget that citizens are the recipients of private security and their opinions can help steer the industry in a positive direction. Hence the present study and similar research can also be used to provide improved services from private security organizations, by way of educating security guards to act and perform in a more satisfactory and reliable manner in citizens’ view. The public is a beneficiary of more effective and more costumer oriented work by security personnel, and it may enhance citizens’ sense of security (Van Steden & Nalla 2010).

Lastly, the phenomenon of a global increase in the number of security guards has been heavily criticized since it according to several scientists follow the logic of the market instead of the logic of the public good (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007; Berndtsson, 2011; Button, 2007). While law enforcements’ role in society is to protect and serve all citizens regardless of status and financial situation, private security services are largely directed towards property owners and businesses that are willing and capable to finance costumed security solutions (Abrahamsen & Williams, 2007). In relation to this, it is not difficult to draw the conclusion that increased implementation of private security in society may result in an uneven distribution of security. Thus the development of the private security industry may

13

create potential opportunities for states and nations but it may also create

problems such as increased inequalities. However, the present study is conducted with the intention to shed light on the public perception of security guards in Malmö, and whether the development of the industry is favorable or not is beyond the scope of this paper.

Citizen perception of law enforcement

One out of the many scientists who have researched citizens’ satisfaction with the police is W. G. Skogan (2005). He concluded that the major determinant of public satisfaction with law enforcement was police behavior when interacting with the public (ibid.). These factors include policemen and policewomen being polite, fair and willing to explain the reason for their involvement (ibid.). It was also

concluded that the behavior of the police towards the public was linked to social factors such as age, race and linguistic capabilities. Another major study on the subject by Cheurprakobkit and Bartsch (2001) suggested that professional knowledge, professional conduct, honesty, and fairness were more strongly related to high citizen satisfaction with police officers than politeness, friendliness, and helpfulness.

One might argue that research on public satisfaction with the police and security guards are of marginal importance and that their effectiveness and efficiency is where all focus should be concentrated. Conversely, in a study by Tyler (2004), it was found that a more positive public perception of the police made the work of the police more effective. People who had a positive view of law enforcement were more likely to comply with orders or requests by the police (ibid.). It was also found that individuals who felt disrespected by the police showed less compliance with police orders. A study by Sunshine & Tyler (2003) also found that police behavior influence people’s willingness to obey the law, even when officers are not present.

These findings may or may not be applicable to security guards, nonetheless, it no longer makes sense to solely focus the research on public attitudes towards the police when large private actors are increasingly present in the field of policing in today’s society. In many nations, including Sweden as previously mentioned, private security guards outnumber the police. In England for instance the ratio of

14

police officer per population is 1/382 and the ratio of security guard per

population is 1/170 (Confederation of European Security Services, 2011). Poland is another European example where the number of security guards per citizen is more than double the number of people working in the police force per citizen (ibid.).

Former research

As mentioned, in relation to law enforcement, the private security industry is under-researched and the topic of citizen perception of security guards is no exception. Prior research findings on the topic of citizens’ perception of security guards have showed mixed results. However, generally research show that the public has a more positive image of security guards than the one often portrayed by the media and popular culture.

Shearing et al. (1985) conducted the first major study with the intent to increase the knowledge of citizens’ perception of private security guards. The study found that the opinion of security guards in the sample was based on the behavior and personality of the guards, rather than the imagery of the industry in popular culture. The research was based on data from interviews from a sample of 209 respondents in Canada (ibid.). A more recent study on the subject was made in the United States in 2002 with a sample of 631 university students (Nalla & Heraux, 2003). The outcome showed a more a positive perception of private security guards than projected. Close to half of the students reported that they trust security guards to protect their lives and property, and two thirds reported that they believe that security personnel are helpful and that their profession is stressful and

dangerous. Conversely, only 17 percent believed that security guards are well educated and only 35 percent believed that security guards are professional (Nalla & Heraux, 2003). In addition, the research showed that females reported a more positive perception of security guards than males. Also, individuals who had had encounters with security guards reported more negative opinions of the profession (ibid.). Having friends or family in security did not affect the perception of

security guards according to the study (ibid.). In accordance with studies of citizen satisfaction of the police, the independent variables race, income, and

employment had moderate effects on the reported satisfaction with security guards (Nalla & Heraux, 2003; Skogan, 2005; Tyler, 2004). For instance, middle class

15

respondents and white respondents held a more negative perception of security guards than minorities and upper and lower class respondents (Nalla & Heraux, 2003).

Two studies conducted in Asia showed positive results regarding citizen satisfaction and trust in private security (Nalla & Lim, 2003; Nalla & Hwang, 2004). One study took place in Singapore in 2003 and the other Asian study took place in South Korea in 2004 (ibid.). In Singapore 260 students participated in the study and close to 70 percent of the sample reported that they believe private security guards together with the police reduce crime and make society safer (Nalla & Lim, 2003). Circa half of the students found the guards helpful and, in contrast with the study in Canada, interaction with security guards improved the level of reported satisfaction on a general level (ibid.). The study indicated that the Singaporean student sample holds an overall positive perception of the professionalism, image, role, and the nature of security work (ibid.).

In South Korea the sample also consisted of students and the respondents generally reported positive opinions regarding the politeness and the overall interaction with clients (Nalla & Hwang, 2004). It was also reported that most respondents felt that security guards were not compensated enough for their work and younger respondents and females were found to have a more positive

perception of security officers (ibid.). In accordance with the study in Singapore, the students believed that security workers collaborated effectively with the police and that their work reduced criminal activity (Nalla & Lim, 2003; Nalla &

Hwang, 2004). However, contrary to the students’ perception in Singapore, the South Korean students held negative views of the professionalism of security personnel (Nalla & Hwang, 2004).

Nalla et al. (2006) found different results in a similar study in Slovenia with a sample of 509 university students. The perception of security guards was overall negative and the students reported that security personnel exhibit low

professionalism and they believed that security guards had a low level of

education (ibid.). In addition, security guards were thought to be helpful to their clients but not to the general public (ibid.). The study divided the sample between

16

criminal justice majors and other students but found no significant differences between the groups regarding the overall results (ibid.).

A study from the Netherlands by Van Steden and Nalla (2010) with a sample of 428 respondents showed that 50 percent of the sample found private security guards to be helpful, and that they handle situations courteously. Overall their view of security personnel’s conduct was satisfactory (ibid.). However, only 20 percent of the sample reported that they have trust in security guards’ ability to protect lives and property. Additionally, only 30 percent of the respondents reported confidence in security guards’ ability to handle complex situations, and only 30 percent believed that Dutch security guards have adequate training. Also, 37 percent reported that they believe guards to have a low level of education (ibid.). The results in this study were neither overly positive nor negative, but the overall results showed more positive attitudes than negative.

Indian research suggests positive attitudes toward private security guards regarding trust, professionalism, and imagery. Close to two thirds of sample (64 percent) stated that security work is dangerous, 71 percent stated that security guards are professional, and 61 percent reported trust in security guards to protect their lives and property. There was also significantly higher reported satisfaction of the work of security professionals by younger respondents and females (Nalla et al, 2013). The most recent study on the topic was made in Portugal 2013 by Moreira et al. (2015) with 163 respondents from the city of Porto. The research found that 61 percent of the sample reported satisfaction with security guards and 63 percent stated that they believe the job is dangerous. Conversely, only 32 percent thought that security work is complex and only 41 percent expressed trust in security guards to protect their lives and property (ibid.). Again, younger respondents and females reported more positive attitudes towards security officers.

Lastly, overall citizens have reported ambivalent opinions of private security guards and studies in different nations have showed different results. Therefore it is difficult to draw any general conclusions from the combined prior research, however, females and younger individuals appear to generally report more trust and higher satisfaction with private security guards.

17

METHODOLOGY

For this research a quantitative survey was developed in order to answer the research questions (see appendix 2), which concern citizen trust and satisfaction with security guards in Malmö. In total the survey contained 26 questions and the survey instrument was heavily influenced by similar surveys constructed by Nalla & Heraux (2003), Van Steden and Nalla (2010), and Nalla et al (2015). However a number of questions were left out since they were not relevant to the study at hand. The questions which were excluded were one demographic question regarding race and four questions regarding security guard’s collaboration with the police. The survey questions that were chosen were considered to be

sufficiently related to satisfaction with and trust in security personnel. The reasoning behind basing the survey on surveys previously used in other studies was the value in comparing and contrasting the results as well as to increase the validity.

In order to reach more people and to increase both validity and reliability of the survey instrument, circa 90 percent of the questionnaires (70) were written in English and translated into Swedish. Circa 10 percent of the surveys (10) were written in English and never translated since many inhabitants in Malmö do not speak Swedish, or do not speak Swedish well enough to fill out a relatively linguistically complicated survey.

Paper and pencil questionnaires were handed out on two different occasions in May 2015, in Malmö. The questionnaires were handed out on weekdays between noon and late afternoon, which may have influenced the sample. Citizens were approached and informed about the purpose and the nature of the study as well as the conditions of participation. Only adults were asked to participate in the study and participation was contingent on verbal consent. Data were gathered at Värnhemstorget and Gustav Adolfs torg. The two locations were chosen since they are two major squares in Malmö, which are open to the public and often busy during the day.

18

Sample

The sample in the present research consists of 78 participants. The study is a small scale research which was limited by time and resources, and this is evident in the size of the sample. According to Denscombe (2009) survey research on a smaller scale generally consist of between 30 and 250 respondents. The study may not be a representable sample for the entire population in Malmö, due to the low number of participants. Therefor one should be cautious of drawing any generalizable conclusions from the findings. However, with the lack of previous research on the field, a smaller sample may suffice as a first insight into citizens’ perception of security guards in Malmö, which can give indication of the public opinion.

Dependent variables

The dependent variables for this research were the statements ‘Citizens can generally trust security guards to protect lives and property’ and ‘Generally I am satisfied with the way security guards conduct themselves’. Respondents may report trust in security guards but not report satisfaction with their work and vice versa, therefore the dependent variables were constructed into two separate statements. These two statements were answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 equals strongly disagree and 5 equals strongly agree.

Independent variables

As for the independent variables, the respondents had to answer several questions about their perception of the professionalism, the imagery, the civility, and the accountability of security officers as well as the characterization of their contact with security officers, if any. Similar to the dependent variables, these statements were answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 equals strongly disagree and 5 equals strongly agree. The perception of security guard’s

professionalism was measured by the three statements ‘Security guards are well educated’, ‘Security officers, in general, are able to handle complex situations’, and ‘Security officers are well trained’. The statements dealing with citizen’s perception of the imagery of security guards were ‘Security work is complex’, ‘Security work is dangerous’, and ‘Security guards run a high risk of getting injured in the course of their work’. Additionally, the three statements about the accountability of security guards were ‘Existing laws are adequate to control the activity of security guards’, ‘Existing supervision of the work of security guards is

19

effective to prevent abuses of power and other offenses’, and ‘Security guards are held accountable when they abuse their power or other offenses’. Last, the three statements regarding civility were ‘Security guards are generally helpful’, ‘Security guards, in general, are sensitive to the public, and ‘Security guards handle calls for assistance with politeness’.

Moreover, the survey also includes a number or demographic questions regarding age, marital status, education, income, and property ownership status. These variables were added in order to find possible mean differences in the reported trust in and satisfaction with private security guards within the demographic variables. In addition, the survey contains a question of whether the respondent has had any type of personal contact with a security guard as well as a question about having family or friends working in security. The question about personal contact was followed by enquiries regarding the experience as well as the behavior of the security guard.

The reason for enquiring whether the respondents have friends or family working in the security industry was due to the potential bias towards the industry these individuals may have. The variable regarding security guard contact was added since it is relevant to this particular study to assess if personal contact with

security guards affects the perceived trust in and satisfaction with security guards.

Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha

As previously mentioned, the independent variables were divided into four different subgroups. Cronbach’s alpha test is a measure to assess the reliability of the indexed items and it assesses the internal consistency or the average

correlation of the indexed scales (Field, 2013). In other words Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of the reliability of the variables used for analysis of the underlying construct, which in this case were professionalism, imagery, accountability, and sensitivity. The scale ranges from 0 to 1, and results over 0.7 are considered to indicate a sufficient reliability and correlation between the variables (ibid.). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study showed moderate to strong internal consistency since the scores ranged from 0.73 and 0.88. This indicates that the items were statistically coherent and therefore theoretically sound.

20 Data treatment

Dependent and independent variables listed on Likert scales were computed from five categories into three categories in order to simplify the overview of the statistical display. The categories ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’ (coded 1 and 2) to the perception statements were computed into one category. Also, the categories ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ (coded 4 and 5) were computed into one category, whereas ‘neutral’ (coded 3) remained unchanged.

To answer the research questions, the percentages and the number of respondents who reported their attitudes to the various statements were presented in a table, which also displayed the mean and the standard deviation. This in order to measure the level of trust in and satisfaction with security guards that the sample reported as well as the perception of professionalism, imagery, accountability and sensitivity of security guards.

ANOVA

In order to compare mean scores of the perception of security officers, depending on demographic characteristics and contact variables, analysis of variance

(ANOVA) was conducted(Field, 2013).The ANOVA test measures if the different mean scores of two or more variables differ significantly (ibid.). Generally, as a matter of good scientific practice, the limit for statistical significance is 0.05, meaning that there is only a 5 percent probability of

observing an effect, at least as extreme as the observation, due to chance (ibid.). The present study is an exploratory study and even less significant mean variances were of interest, therefore also significance at the level of 0.1 and lower were noted. It is important to remember that significance testing is directly related to the size of the sample and the same effect will have different significance values in different sized samples. A small difference may be considered significant in a large sample and a large difference can be deemed insignificant in a small sample (Field, 2013). Since this study is based on a small sample the mentioned

significance level was chosen.

Before analyzing the significance in the ANOVA table Levene’s test of equality of variance was analyzed. This test measures the variance within the groups. If the p-value in Levene’s test is over 0.05 the variance within the groups are considered

21

normally distributed (Field, 2013). All variables in this study displayed a normally distributed variance.

Ordinary least square

In order to assess the relationship between the constructs of professionalism, imagery, accountability, and sensitivity and the dependent variables trust in and satisfaction with security officers, ordinary least square (OLS) regression was employed. Before performing the OLS regression and analyzing the results, the three questions associated with the respective construct were computed into one variable. Thereby each construct ranged from 3 to 15, since each question related to the construct ranged from 1 to 5.

Ethical considerations

The survey includes questions about age, education, income, and perception of security guards, which can be considered sensitive information. Thus it is

important to inform the respondents of the purpose of the study, the anonymity of participation as well the confidentiality of the gathered data. In all forms of research the purpose or the benefit of the research must be contrasted and

evaluated against the potential harm for the participants (Mellgren & Tiby, 2014). In the present study the potential harm for participants is not significant since this quantitative survey research is anonymous with closed multiple choice questions. The respondents, as citizens of Malmö, are potential beneficiaries of a research of this nature since the gathered data can serve to increase the knowledge of citizens’ perception of private security. This can in turn result in more efficient services from security guards and help policy makers to make more educated decisions about future regulation of the industry.

RESULTS

Descriptive variables

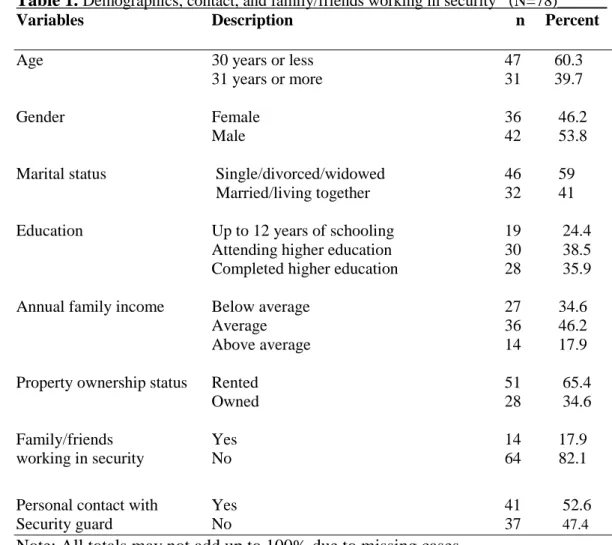

As shown in Table 1, 78 respondents participated in this study, 36 females and 42 males. Age was computed into a binary variable and the results show that 60.3 percent of the respondents were 30 years old or younger. More than a third of the participants (38.7 percent) are attending higher education, 35.9 percent have completed university and 24.4 percent have 12 years of schooling or less. 17.9

22

percent have family or friends working in security and more than half of the sample (52.6 percent) have had personal contact with security guards.

Table 1. Demographics, contact, and family/friends working in security (N=78)______ Variables Description n Percent

Age 30 years or less 47 60.3

31 years or more 31 39.7

Gender Female 36 46.2

Male 42 53.8

Marital status Single/divorced/widowed 46 59 Married/living together 32 41

Education Up to 12 years of schooling 19 24.4 Attending higher education 30 38.5 Completed higher education 28 35.9

Annual family income Below average 27 34.6 Average 36 46.2 Above average 14 17.9

Property ownership status Rented 51 65.4 Owned 28 34.6

Family/friends Yes 14 17.9 working in security No 64 82.1

Personal contact with Yes 41 52.6 Security guard No 37 47.4 Note: All totals may not add up to 100% due to missing cases

Contact variables

As displayed in Table 2, slightly less than half of the respondents (48.1 percent) who reported to have had personal contact with security guards reported the experience to have been positive. A third (34.1 percent) reported the experience as neutral, and 17.1 percent reported the experience as negative. Additionally, over half of the respondents found the behavior of the security guard to be neutral. One third (34.1 percent) reported that the security guard acted courteously and 14.6 percent found the security guard’s behavior rude or impolite.

23

Table 2. Contact with security guard (N=41)

Variables Description n Percent

Reason for contact Needed information/help 14 34.1 Information/help offered 4 9.8

Remark from guard 9 22

Other 14 34.1

Type of experience Negative 7 17.1

Neutral 14 34.1

Positive 20 48.1

Security guard behavior Impolite/rude 6 14.6

Neutral 21 51.2

Courteous 14 34.1

Findings on citizen’s perception of security guards

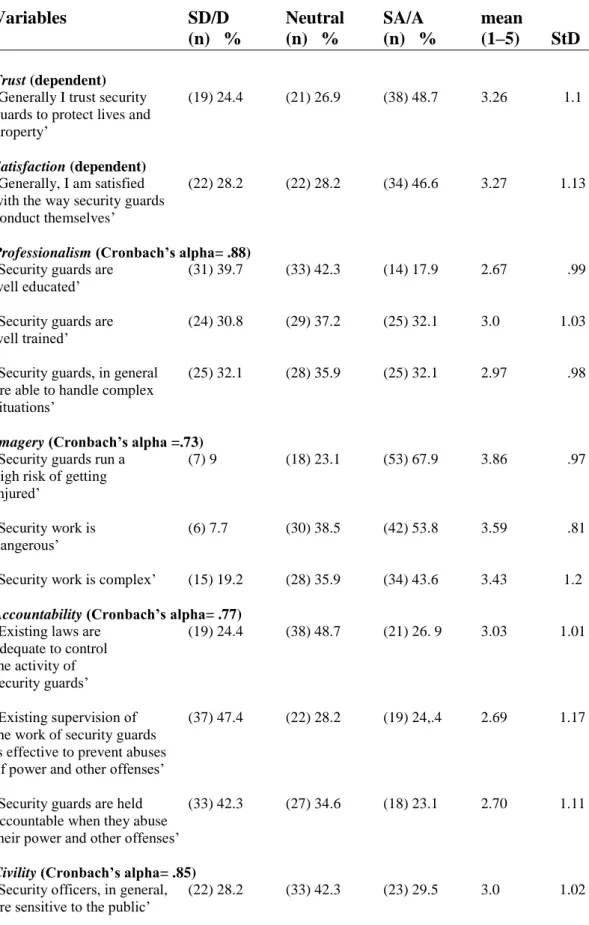

Results in Table 3 indicate that close to half of the respondents (48.7 percent) reported that they either agree or strongly agree to the statement ‘Generally I trust security guards to protect lives and property’. Circa one quarter (26.9 percent) were neutral to the statement and the remaining 24.4 percent strongly disagreed or disagreed. Less than half of the sample (46.6 percent) reported satisfaction with the way security guards conduct themselves, while the remaining answers were evenly divided between a neutral stance (28.2 percent) and dissatisfaction (28.2).

Regarding professionalism, merely 17.9 percent believe that security guards are well educated and only one third (32.1 percent) of the sample believe that security guards are well trained. The study shows more positive results about the imagery of the profession. Two thirds of the sample (67.9 percent) answered that they believe that security guards run a high risk of getting injured during the course of their work, and a majority (53.8 percent) believe that security work is dangerous. To statements regarding accountability respondents were more negative. Close to half (47.4 percent) do not believe that existing supervision of the work of security guards is effective in preventing abuses of power and other offences, and 42.3 percent believe that security guards generally are not held accountable when they abuse their power. Furthermore, in the category civility relatively mixed results are displayed. 47.7 percent report to find security guards helpful. However, less

24

than one third (29.5 percent) find security officers to be sensitive to the public and only one third of sample (34.6 percent) believe that security guards handle calls for assistance with politeness.

Table 3. Citizen perception of security guards (N=78)

Variables SD/D Neutral SA/A mean

(n) % (n) % (n) % (1–5) StD Trust (dependent)

‘Generally I trust security (19) 24.4 (21) 26.9 (38) 48.7 3.26 1.1 guards to protect lives and

property’

Satisfaction (dependent)

‘Generally, I am satisfied (22) 28.2 (22) 28.2 (34) 46.6 3.27 1.13 with the way security guards

conduct themselves’

Professionalism (Cronbach’s alpha= .88)

‘Security guards are (31) 39.7 (33) 42.3 (14) 17.9 2.67 .99 well educated’

‘Security guards are (24) 30.8 (29) 37.2 (25) 32.1 3.0 1.03 well trained’

‘Security guards, in general (25) 32.1 (28) 35.9 (25) 32.1 2.97 .98 are able to handle complex

situations’

Imagery (Cronbach’s alpha =.73)

‘Security guards run a (7) 9 (18) 23.1 (53) 67.9 3.86 .97 high risk of getting

injured’

‘Security work is (6) 7.7 (30) 38.5 (42) 53.8 3.59 .81 dangerous’

‘Security work is complex’ (15) 19.2 (28) 35.9 (34) 43.6 3.43 1.2

Accountability (Cronbach’s alpha= .77)

‘Existing laws are (19) 24.4 (38) 48.7 (21) 26. 9 3.03 1.01 adequate to control

the activity of security guards’

‘Existing supervision of (37) 47.4 (22) 28.2 (19) 24,.4 2.69 1.17 the work of security guards

is effective to prevent abuses of power and other offenses’

‘Security guards are held (33) 42.3 (27) 34.6 (18) 23.1 2.70 1.11 accountable when they abuse

their power and other offenses’

Civility (Cronbach’s alpha= .85)

‘Security officers, in general, (22) 28.2 (33) 42.3 (23) 29.5 3.0 1.02 are sensitive to the public’

25

‘Security guards are (11) 14.1 (29) 37. 2 (38) 48.7 3.47 .90 Generally helpful’

‘Security officers handle calls (16) 20.5 (35) 44.9 (27) 34.6 3.18 .87 for Assistance with politeness’

Note: All totals may not add up to 100 percent due to missing cases

SD/D=strongly disagree/disagree, SA/A=strongly agree/agree, StD=standard deviation

Analysis of variance

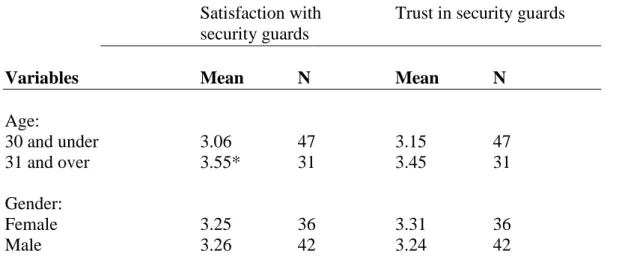

In table 3 an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in order to detect any significant mean differences within the demographic variables regarding trust in and satisfaction with security guards. The means of the characteristic variables were compared and none of these variables showed statistical significance at the benchmark level of 95 percent significance (p < 0.05). The results indicate that respondents who were 31 years of age or older reported higher levels of

satisfaction with security guards than younger respondents. This, however, was marginally significant (p < 0.1). Older respondents also reported higher levels of trust in security guards, but the results were not statistically significant. Gender did not appear to affect trust in or satisfaction with security guards. Furthermore, university students showed a higher level of trust in and satisfaction with security guards than university graduates, and individuals with up to 12 years of schooling. The results, however, were not statistically significant. Having family or friends working in the security industry did appear to influence both trust and satisfaction with security guards, and the results were marginally significant (p < 0.1).

Respondents who reported to have had personal contact with a security guard reported higher satisfaction but marginally lower trust. Again, the results were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Comparison of means between demographic variables (N=87)

Satisfaction with Trust in security guards security guards

Variables Mean N Mean N

Age: 30 and under 3.06 47 3.15 47 31 and over 3.55* 31 3.45 31 Gender: Female 3.25 36 3.31 36 Male 3.26 42 3.24 42

26 Education: Up to 12 years 3.05 19 3.11 19 Attending university 3.43 30 3.43 30 Completed university 3.21 28 3.21 28 Income: Below average 3.19 27 3.19 27 Average 3.33 47 3.19 47 Above average 3.14 14 3.57 14 Property status: Renting 3.25 51 3.25 51 Owning 3.26 27 3.30 27 Residential area: Rural 3.14 22 3.18 22 Urban 3.30 56 3.30 56 Family/friends in security: Yes 3.71 14 3.79 14 No 3.16* 64 3.16* 64

Personal contact with security guard:

Yes 3.44 41 3.24 41

No 3.05 37 3.30 37

*p<.1;**p<.05; ***p≤.01

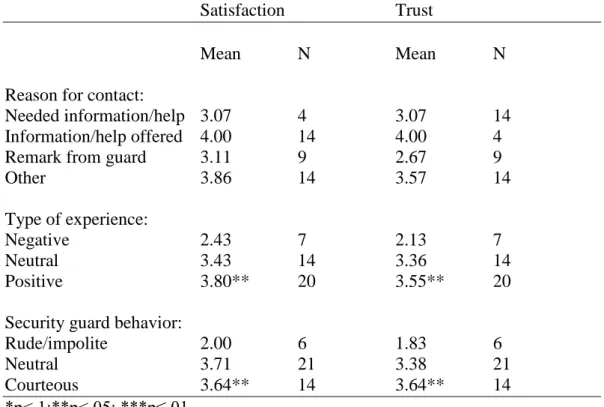

Further analysis of variance was conducted in order to assess any significant mean differences between the contact variables. In the sample, 41 respondents reported to have had personal contact with security guards and the contact variables which were assessed were; reason for contact, type of experience, and security guard behavior. As visible in table 4, the type of experience and the behavior of the security guard have a statically significant influence on the respondents’

perception of security guards. Unsurprisingly, a negative experience with security personnel influences the trust and satisfaction with security personnel negatively, and similar results were found for respondents who reported impolite or rude security guard behavior. No statistically significant mean difference was found in the variable ‘reason for contact’.

27

Table 5. Comparison of mean context of contact with security guard (N=41)

Satisfaction Trust

Mean N Mean N

Reason for contact:

Needed information/help 3.07 4 3.07 14

Information/help offered 4.00 14 4.00 4

Remark from guard 3.11 9 2.67 9

Other 3.86 14 3.57 14

Type of experience:

Negative 2.43 7 2.13 7

Neutral 3.43 14 3.36 14

Positive 3.80** 20 3.55** 20

Security guard behavior:

Rude/impolite 2.00 6 1.83 6

Neutral 3.71 21 3.38 21

Courteous 3.64** 14 3.64** 14

*p<.1;**p<.05; ***p≤.01

Ordinary least square

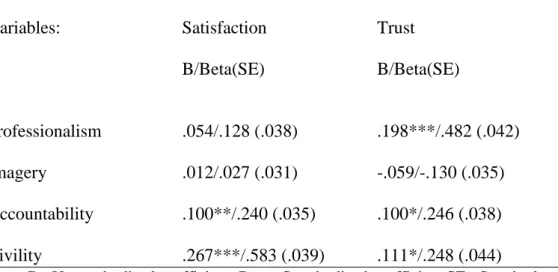

In table 6 the dependent variables satisfaction with security guards and trust in security guards were regressed against the key independent variables;

professionalism, imagery, accountability, and civility. As shown in the table below, out of the four key independent variables, civility (b=0.267, p < 0.001) was the strongest predictor of reported satisfaction with security guards, when controls were applied for the other key variables in the model. Conversely, professionalism (b=0.198, p < 0.001) was the strongest predictor of trust in security guards but it did not predict satisfaction at a significant level. Also, reported accountability of security guards predicted both satisfaction with security guards (b=.100, p < 0.01) and trust in security guards (b=.100, p < 0.05). Interestingly, imagery did not appear to predict neither satisfaction nor trust in the security guard profession. The key independent variables account for 85 percent (R= 0.85) of the variance in the dependent variable satisfaction with security guards, and 80 percent (R= 0.80) of the variance in trust in security guards. This means that the reported

professionalism, imagery, accountability, and civility of security guards together explain a substantial portion of the variation in reported satisfaction with security guards and reported trust in security guards.

28

Table 6. Ordinary least square regression of trust in and satisfaction with security

guards and key independent variables

Variables: Satisfaction Trust

B/Beta(SE) B/Beta(SE)

Professionalism .054/.128 (.038) .198***/.482 (.042)

Imagery .012/.027 (.031) -.059/-.130 (.035)

Accountability .100**/.240 (.035) .100*/.246 (.038)

Civility .267***/.583 (.039) .111*/.248 (.044)

Note: B= Unstandardized coefficient; Beta= Standardized coefficient SE= Standard error

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p≤0.001

In summary, the overall results indicate a more positive than negative perception of security guards. However, these results indicate that the citizens in the sample were largely ambivalent in their perception of security guards. Older citizens appear to have a higher degree of satisfaction with security guards and having friends or family working in security predicts more satisfaction and trust in security personnel. Having had personal contact with security guards did not, however, predict trust or satisfaction on a statistically significant level. On the other hand the type of experience one has had with security guards as well as the behavior of the guards did predict trust and satisfaction with security officers. Lastly, reported civility was the strongest predictor of satisfaction with security guards and professionalism was the strongest predictor of trust in security guards.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This research intended to shed light on citizens’ perception of security guards, which was measured as trust in and satisfaction with security guards in Malmö. Focus was also on finding possible factors which affect citizens’ trust and satisfaction with security guards.

29

Results

Findings indicate a more positive than negative perception of security guards, however more than half of the respondents reported a neutral or negative stance in terms of their satisfaction and trust in security guards. This shows that

respondents in this sample do not have a clear perception of security guards on a group level, but that the image is not as negative as the depiction of the profession in the media and popular culture. This is true not only for the research in Malmö. Prior research in various parts of the world (Moreira et al, 2015; Nalla & Heraux, 2003; Shearing et al, 1985; Van Steden & Nalla, 2010), including North America, the Netherlands, and Portugal, indicate an ambiguous perception of the private security industry, but the overall image of the security guard profession appears to be more positive than negative.

The factors which affected citizen’s trust and satisfaction most significantly in this study were the type of experience with security guards and the security guard behavior. Similar results were found in the Netherlands (Van Steden & Nalla, 2010) with a much larger sample (N=426). Although the sample of respondents who had interacted with security guards in this study was small (N=41), the fact that similar results were found in a more extensive study can increase the validity of the results. The findings were also in accordance with many studies of citizens’ perception of the police, including Tyler (2004) and Skogan (2005). Additionally, the category ‘civility’ predicted both satisfaction and trust in security guards and this shows that courteous security guard behavior can influence the overall perception of the profession.

Findings of this nature may create incentives for private security organizations to implement more training and education regarding customer service and polite security guard behavior. However, the main responsibility of security guards is certainly not to provide hospitality to the public. Instead, their main

responsibilities are to prevent loss for their clients and to maintain order. The actions of security guards are therefore not always desirable for people coming in contact with them. Nonetheless, security guards can almost always behave in manner that is perceived as fair, and this is worth stressing when discussing people’s perception of security guards.

30

Moreover, research show that a more positive public perception of the police makes police work more effective and more efficient (Skogan, 2005; Tyler, 2004). Due to the decentralization of social control, the increased employment of security guards and the increased public/private partnership between law enforcement and private security, it is realistic to assume that the public perception may have similar effects on the work of security guards. Hart &Livingstone (2003) state that in the same manner as the public’s image of the police is fundamental to the success of police operations, the image of private security is central to its

operations, authority, and legitimacy. As discussed earlier, authority is crucial for effective performance by private security companies. Since authority is an effect rather than an entity, the public perception is central to establishing authority. Without taking a stance on whether the increased presence of security guards is favorable or not, increased efficiency of security work can benefit society in terms of for example increased public sense of safety.

It should also be noted that several respondents mentioned either in writing (although there was no open question in the survey) or verbally that recent media coverage of power abuses by security guards in Malmö affected their perception negatively. This, although not empirically validated, indicates that the media has a role in shaping the perception of the security industry. In relation to this, 42 percent of the respondents reported that security guards are not held responsible when abusing their power and close to half of the sample reported that existing supervision of security guards is inadequate to prevent power abuses. These largely negative perceptions of the accountability of security guards may therefore be partly based on media discourse.

Furthermore, the relatively positive perception of security guards in this study indicates a level of acceptance of the profession which is inconsistent with image often portrayed in the media and popular culture. It is possible that the perception of increased risks in society contributes to a legitimization of the work of private security personnel, which in turn influences the perception of the industry. This would be in accordance with Ulrich Beck’s theory of risk society, which both Krahmann (2011) and Berntsson (2011) associate with the expansion and the legitimization of the private security sector. Additionally, shifting security norms

31

and contemporary crime policy, which to larger extent focuses on situational prevention, may also influence the public perception of security personnel.

Lastly, due to the expansion of the private security sector, more citizens come in contact with security guards. Thus it is likely that an increasing number of citizens base their perception of the profession on personal contact rather than the image portrayed in various media outlets. This might explain the relatively positive attitudes towards security guards displayed in this sample. In the present study over half of the respondents reported to have had personal contact with security guards, and this gives an indication of the presence of security guards in Malmö.

Limitations

The most evident limitations of the study are the size of the sample and the lack of variation in the sample. The sample in this study is relatively small (N = 78) and it does not have the diversity of a representable sample for the population in Malmö. One should therefore be cautious of drawing generalizing conclusions from the findings. The sample was also possibly affected by a relatively large external omission. It is estimated that circa one third of the individuals asked to participate declined participation. However, the internal omission was low (0.25 percent), which may indicate that the participants found the research topic to be relevant and that the survey was well-constructed.

In addition, it is possible that students and former students were more likely to participate in the study since they have likely conducted some form of survey research themselves at university. A large amount of the respondents (43.6 percent) were between 18 and 25. This might also explain why a large proportion of the sample attended university (38.5 percent). A possible reason for the

disproportionally high number of young respondents and university students may be that the surveys were distributed, on two different occasions, between noon and late afternoon on weekdays. The population with a daytime occupation was

therefore less likely to participate. Thus, the sample can be considered a convenience sample, which can be explained by time and resource limitations. Another flaw in method of the research is that a limited amount of information (N=78) was fitted into a large amount of variables. Ideally, the survey should have been less extensive and more adapted to the size of the sample. Nonetheless, this

32

exploratory study aimed to give an indication of the public opinion of security guards in Malmö, rather than a fully generalizable picture.

Future research

Future research should address citizens’ perceived safety in the presence of security guards. It would be interesting if the perceived safety in the presence of private security personnel was assessed and compared to the perceived safety in the presence of law enforcement. In a time where it is equally as likely to come in contact with private security personnel as police officers a study of this nature would be highly relevant.

33

REFERENCES

Abrahamsen, R., Williams, M. (2009). Security Beyond the State: security assemblages in International Politics. International Poltical Sociology. 3, (1) 1-7.

Abrahamsen, R., Williams, M. (2007). Securing the City: Private Security Companies and Non-State Authority in Global Governance. International Relations. 21, (2) 237-253.

Berndtsson, J. (2011). Security Professionals for Hire: Exploring the Many Faces of Security Expertise. Millennium- Journal of International Studies. 40, (2) 303-320.

Button, M. (2007). Assessing the Regulation of Private Security across Europe. European Journal of Criminology. 4, (2) 109-128.

Cheurprakobkit, S., & Bartsch, R. A. (2001). Police performance: A model for assessing citizens' satisfaction and the importance of police attributes. Police Quarterly, 4(4), 449-468.

Cohen, L.E., and M. Felson. (1979). Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588-608.

Cohen, S. (1985). Visions of Social Control. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Confederation of European Security Services. (2011). CoESS Facts & Figuers 2011. Retreived 2015-05-10, from http://www.coess.eu/?CategoryID=203

Cornish, D. (1993). Theories of Action in Criminology: Learning Theory and rational Choice Approaches. In Clarke R.V. & Felson M. (eds), Routine Activity and Rational Choice. Advances in Criminological Theory 5, 351-382.

Denscombe, M. (2009). Forskningshandboken: För småskaliga forskningsprojekt inom samhällsvetenskaperna. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

34

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll. London; Los Angeles: Sage.

Gill, M., White, A. (2012). The Transformation of Policing: From Ratios to Ratinonalities. The British Journal of Criminology. 53, (3) 73-93.

Goold, B., Loader, I., & Thumala, A. (2010). Consuming security?: Tools for a sociology of security consumption. Theoretical Criminology, 14(1), 3-30.

Group4Secure. (2015). Where we operate. Retrieved 2015-05-15, from

http://www.g4s.com/en/Who%20we%20are/Memberships%20and%20accreditati ons/

Hart, J., Livingstone, K., (2003). The Wrong Arm of the Law? Public images of Private Security. Policing & Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy, 13(2), 159-170.

Krahmann, E. (2011). Beck and beyond: Selling security in the world risk society. Review of International Studies, 37(1), 349-372.

Mellgren, C. & Tiby, E. (2014). Kriminologi –en studiehandbok. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Moreira, S., Cardoso, C., & Nalla, M. K. (2015). Citizen confidence in private security guards in Portugal. European Journal of Criminology, 12(2), 208-225.

Mulone, M. (2013). Researching private security consumption. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 19(4), 401-417.

Nalla, M., Heraux C. (2003). Assessing goals and functions of private police. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31(3), 237-247.

Nalla, M., Hwang, E. (2004). Assessing professionalism, goals, images, and nature of private security in South Korea. Asian Policing 2(1), 104–121.

35

Nalla, M.,Lim, S. (2003). Students’ perceptions of private police in Singapore. Asian Policing 1(1) 27–47.

Nalla, M., Mesko, G., Sotlar, A., Johnson ,J. (2006). Professionalism, goals and the nature of private police in Slovenia. Journal of Criminal Justice and Security, 8(3), 309-322.

Nalla, M., Ommi, K., Murthy, S. (2013). Nature of work, safety, and trust in private security in India: A study of citizen perceptions of security guards. In: Unnithan NP (ed.) Crime and Justice in India. New Delhi: Sage, 226–243.

Nalla, M., & Steden, v., R. (2010). Citizen satisfaction with private security guards in the Netherlands: Perceptions of an ambiguous occupation. European Journal of Criminology, 7(3), 214-234.

Shearing, C., Stenning, P., Addario S. (1985). Public Perceptions of Private Security Canadian Police College Journal, 9(3), 225-253.

Skogan, W. G. (2005). Citizen satisfaction with police encounters. Police Quarterly, 8(3), 298-321.

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review, 37(3), 513-548.

Svenska stöldskyddsföreningen (2008). Säkerhet - på juridisk grund. (3., rev. utg.) Stockholm: Svenska stöldskyddsföreningen (SSF).

Tyler, T. R. (2004). Enhancing police legitimacy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 593(1), 84-99.

Wakefield, A. (2003). Selling security: the private policing of public space. Cullompton: Willan.

36

White, A. (2011). The new Political Economy of Private Security. Theoretical Criminology. 16, (1) 85-101.

Zedner, L. (2007). Pre-crime and post-crimonology? Theoretical Criminology. 11, (1) 261-281.