This paper was presented at The ISPIM Innovation Conference – Innovating Our Common Future, Berlin, Germany on 20–23 June 2021.

Event Proceedings: LUT Scientific and Expertise Publications: ISBN 978-952-335-467-8

1

Factors enabling global innovation teams

Mikael J. Johnsson*

Mälardalen University, Box 325, Eskilstuna, Sweden

E-mail: mikael.johnsson@mdh.se, mikael.j.johnsson@gmail.com * Corresponding author

Abstract: In this research, a systematic literature review of factors enabling global innovation teams has been conducted. In innovation work, global companies can benefit from, for example, accessing talents and working around the clock. On the other hand, the call for reduced travelling may be hinder global innovation teams from conducting innovation work. Previous research has developed knowledge of team models, virtual teams and innovation teams. In this study, a distinction is made between virtual teams and global teams, even though both types of team connect through technology. Virtual team members can meet under certain circumstances, while global team members cannot meet without travelling far distances. Building on prior research, the study proposes factors enabling global innovation teams and a model to demonstrate and illustrate the different perspectives of the global innovation team. Limitations are discussed, and further research is proposed.

Keywords: innovation management; innovation team; global innovation team; global team; virtual team; innovation group; multidisciplinary; x-functional.

1 Problem

This study contributes knowledge of factors enabling the work of global innovation teams. To set the scene and define the concept of a global innovation team, I first define innovation team and global team separately. I take Johnsson’s position (Johnsson, 2017a) that an innovation team is purposely created to innovate; that is to say, it is not just any working team being innovative. In this sense, the innovation team needs accurate innovation-related competence and proper preparation (ibid); 2). Even though global and virtual team members meet by means of technical devices (Olson et al., 2014), there are significant differences between the two types of team. Global teams’ members are located in different countries; they cannot meet physically without travelling far distances (Derven, 2016). In contrast, virtual teams may meet in person more easily because virtual team members may be located close to each other, for example, in the same region, locality, or even the office next door (Franz, 2012). Consequently, a global innovation team is defined as a team purposely created to innovate, be distributed globally and not meet in person without great effort.

For global companies, there are several advantages to working globally, for example, accessibility to talent (Manning et al., 2015) and continuous work around the clock (Haywood, 1998). To create a global team, Derven (2016) stresses the importance of meeting in person as the team develops, and Johnsson (Johnsson, 2017b) suggests a

physical kick-off to begin innovation projects. There are, however, arguments against travelling because it has negative effects on the environment (Morris, 2008). Travel also makes people less productive (Sack, 2009) and negatively impacts work quality (Lahiri, 2010). Today, not travelling is more relevant than ever due to the COVID-19 situation, which has made physical meetings nearly impossible. Still, global innovation teams are relevant to global companies. Therefore, a review of factors enabling global innovation teams’ work is indicated.

As further studies of global innovation teams might follow, this paper can serve as inspiration. Practitioners preparing for global innovation work may benefit from the knowledge presented in this paper.

2 Current understanding

Research on factors enabling teams’ work is well known, to name a few studies in the following. In 1965, Tuckman (Tuckman, 1965) developed a four-phase forming-storming-norming-performing model of group development; the GRPI model (goals, roles, procedures, interpersonal relationships) was developed by Rubin et al. (Rubin et al., 1977) to demonstrate team collaboration; Katzenback and Smith (Katzenback and Smith, 1993) added factors such as accountability, commitment and skills to their model, elaborating on effective teams and performance results; the T7 model was developed by Lombardo and Eichinger (Lombardo and Eichinger, 1995), who also highlighted the importance of, for example, team members’ trust, team leadership and culture; Hackman (Hackman, 2002) proposed key conditions for team productivity as he deepened the focus on team members’ fit with the team and added the importance of context to the previous models; Lencioni (Lencioni, 2002) introduced ways to overcome team dysfunctionality through an emphasis on trust, conflict, commitment, accountability and results. These models have been further developed and well researched; for example, Wheelan et al. (Wheelan et al., 2020) proposed that the group transforms into a team or even hgh-performing team if it reaches the performing phase (referring to Tuckman, 1965).

Considering the definition of global innovation teams, comprehensive reviews of factors enabling such teams’ work are not yet conducted. Instead, research shows a scattered area focusing on specific areas. The only comprehensive review yet found of enablers for innovation teams’ work was conducted by Johnsson (2017a). In his work, he identified 20 factors and organised them into three perspectives, namely the organisational, innovation-team and member’s perspectives, as demonstrated in Table 1.

However, literature reviews focusing on global, virtual, or distributed work are quite numerous in the past decades (Ebrahim et al., 2009; Scott and Wildman, 2015; Seshadri, 2019). The most relevant and comprehensive review on virtual teams identified was conducted by Clark et al. (2019). In their research, aiming to identify the most important factors influencing virtual project teams’ performance, they identified twenty-two factors influencing virtual team’s performance positively (ibid, p. 42).

Research gap

Previous team models (e.g. Tuckman, 1965; Lencioni, 2002; Wheelan et al., 2020) include neither innovation nor virtual or global aspects. Clark et al. (2019) do not focus on innovation teams specifically, and Johnsson (2017a) does not consider global aspects.

Therefore, further investigations are motivated. This study aims to develop additional knowledge to contribute to the identified knowledge gap in this research area.

3 Research question

Based on the problem and identified research gap, the following research question has guided the work conducted: What factors enable global innovation teams’ work?

4 Research design

To contribute knowledge toward the research question, a systematic review was conducted. First, search strings were developed. Because innovation is sometimes referred to as product development or design, the following search strings were used: “virtual team*” AND innovation OR “product development” OR design; “distributed team*” AND innovation OR “product development” OR design; “global team*” AND innovation OR “product development OR design”. Second, the search engine Primo, which covers multiple databases provided by the university, was used. Primo was suitable for the review conducted, because innovation is multidisciplinary; Google Scholar was used for the same reason. Papers not available through these two search engines were not reviewed in this work.Third, after I had reduced doublets and selected papers based on relevance by reading titles and abstracts, sixty-eight papers remained for analysis. The articles were read and thematically analysed (Boyatzis, 1998) to identify factors enabling global innovation teams’ work. Ten themes were identified: characteristics, collaboration, communication, culture, diverse knowledge/function, management/leadership, sense-making, social interaction, technology and trust (Table 1). For articles to be relevant to the current study, the title and abstract needed to explicitly contain keywords or phrases leading to, or interpreted as such, factors enabling global innovation teams’ work.

The identified factors were then analysed against the work of Clark et al. (2019) and Johnsson (2017a) to develop a comprehensive picture of enablers for global innovation teams. In his work, Johnsson identified and categorised each enabler according to three perspectives: that of the organisation, the innovation team and the innovation team member. Clark et al. do not make this distinction in their review, nor do they explain/define the identified factors or visualise their findings in a model. Therefore, Clark et al.’s work was re-analysed, resulting in further clustering from twenty-two to fifteen factors. For example, 1) cultural characteristics and cultural diversity were clustered to culture; 2) leadership activities, leader qualities, leadership structure and leadership training were clustered to leadership. Both Clark et al.’s work and the identified papers were analysed from organisational, team and individual perspectives, as suggested by Johnsson (2017a). Substantial overlaps with Johnsson and Clark et al. were identified in the systematic literature review conducted. Considering that virtual teams are not always global teams, in the analysis of the identified factors against Clark et al.’s work, it was understood that the factors influencing virtual work were related to global innovation teams. Therefore, they were merged, adding two new enablers to Clark et al.’s work: sense-making and diverse knowledge. The new set of factors, in total seventeen, was then analysed against Johnsson’s work on enablers for innovation teams. Here, nine new factors were identified: characteristics, communication, interaction, sense-making, satisfaction, synchronicity, task

structure, technology and trust. The remaining seven factors were considered synonyms contributing new dimensions to already identified enablers, resulting in a total list of 30 factors enabling global innovation teams (Table 1). In this work, it was not possible to compare references; therefore, the potential for doublets in the presented findings must be considered.

5 Findings

In the following section, the identified enablers from the systematic literature review are briefly demonstrated in order of volumes of identified papers, using a selection of identified papers. It is followed by conclusion of the study conducted.

5.1 Factors enabling global innovation 5.1.1 Communication

Focusing on setting up communication systems for dispersed teams are vital, as communication is argued to build trust (Olson and Olson, 2012), resolve conflicts (Gibson and Gibbs, 2006). Communication is also important for knowledge transfer to reduce knowledge gaps (Castellano et al., 2017) and not affect performance negatively (Hosseini

et al., 2017). One challenge regarding communication is to handle time zones, as it is a

barrier for dispersed teams (Jasper, 2019). Further, language policies and language training are needed for effective communication (Klitmøller and Lauring, 2013). Spurring communication, side channels for instant or informal communication between members not necessarily concerning the entire team, are proposed (Larsson et al., 2002).

5.1.2 Technology

Technical equipment is what brings global teams together, enabling knowledge sharing and support relationship building (Henttonen and Blomqvist, 2005). There are numerous examples of technical equipment bringing remote team members closer, such as “transparent” walls to enable people to interact on distance (Fruchter and Bosch-Sijtsema, 2011) or 3D virtual environments (Bosch-Sijtsema and Haapamäki, 2014). However, by adding video to an online meeting, trust and collaboration can increase (Olson et al., 2014). There is, however, a need to allow adjustments depending on the purpose (Dadriyansyah

et al., 2010), as monitoring of team members will potentially lead to trust issues (Alge et al., 2004), and too much communication can lead to information overload (Hammond et al., 2005).

5.1.3 Trust

To establish trust in a global team conducting innovation work is important for team effectiveness (Muethel et al., 2011), collaboration (Alsharo et al., 2017) and job satisfaction (Morris, 2008), which can be achieved through team feedback (Peñarroja et

al., 2015). When team members get to know about each other’s behaviours, trust can be

built more easily (Robert et al., 2009). To stimulate trust in dispersed teams, standard team-building tools may be used (Holton, 2001).

5.1.4 Management/leadership

Virtual leadership faces many challenges, for example, creating the team and setting up communication channels (Manole, 2014). In virtual teams, emergent leadership has positive effects on performance (Charlier et al., 2016) as well as a coaching style (Rousseau

et al., 2013) and transformational leadership (Li et al., 2016). Task-oriented leadership

(Pinar et al., 2014) and leaders who build trust and psychological safety, set guidelines, communicate regularly and build relationship increase the chances for creativity and success (Han et al., 2017).

5.1.5 Collaboration

Global teams based on diverse functions show a positive impact on collaboration (Batarseh

et al., 2018) and speed up creativity processes (Karlsson et al., 2005). It is even possible to

develop high-performance teams that only meet through technical devices if putting attention to relationship, interpersonal trust, frequency of communication and time spent on interaction (Olaisen and Revang, 2017). However, it is important to choose tools that support knowledge sharing through non-verbal behaviour, for example, smiles, headshakes and eye contact (Gressgård, 2011). To avoid bullying, potential members are strongly advised to be evaluated on negative workplace acts and abusive personalities before assigned to a team (Creasy and Carnes, 2017).

5.1.6 Diverse knowledge/function

Research shows that diverse knowledge in global innovation teams supports innovation (Batarseh et al., 2017a, 2017b). About different roles in virtual teams, two studies using Belbin’s team role composition (1981, 2014) has been identified: the first suggests (Meslec and Curşeu, 2015) that balanced teams perform best in the initial phases and that women in teams increase the quality and avoid conflicts to a higher degree than others; the other study suggests (Eubanks et al., 2016) that doers are important for high performance.

5.1.7 Interaction

Interaction can be divided into social and technical interaction, where both these aspects need continuous improvements to stimulate collaboration (Painter et al., 2016). However, personal trust is significantly important to develop to obtain team interaction (Ocker and Hiltz, 2012). Regarding trust in distributed teams, it is pointed out that social capital is gained through interaction, finding out who-knows-who and who-knows-what, to learn who-to-trust. This becomes especially important when team members must rely on people’s advice, not in one’s own area of expertise (Larsson, 2007). However, distance doesn’t need to be a problem for innovation, as it is seen that the greater the relation is to the problem, the more significant results may be possible (Tzabbar and Vestal, 2015).

5.1.8 Sense-making

Sense-making in distributed teams is complex. It brings other aspects not similar for co-located teams, such as stakeholders, language barriers, interpretation of uncertainties, which ambiguities should be addressed and discussed carefully (Laine et al., 2016). In practical design work, team members use, except for sketches and prototypes, various objects to explain ideas or functions followed by negotiations and decisions, which is complex for global teams. Therefore, virtual environments to ease mutual understanding is

vital for global design teams as a physical object is only accessed at one place at a time (Larsson, 2003). To solve some of these problems, software has been developed to support creativity and group decision making (Chen et al., 2007). However, physical objects are not considered.

5.1.9 Culture

Culture plays a significant role in global teams, as different behaviours and perceptions affect interaction and performance. In a cross-cultural study, thirteen behaviours were identified to be aware of (Dekker et al., 2008). However, to overcome cultural issues, it is suggested to educate involved parties in advance, especially on cross-cultural collaboration, reaching agreements, sharing knowledge, and making progress (Duus and Cooray, 2014).

5.2 Conclusion

The literature review conducted were focusing on a global perspective. However, taking a system thinking approach, the identified factors are also applicable from an organisational -, innovation team-, and innovation team member.

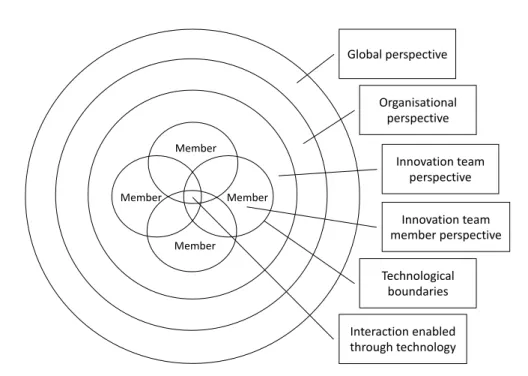

Based on the research by Clark et al. (2019) and Johnsson (2017a) and on previous research into team models (as above), a new model emerged (Figure 1). The innovation team is in the centre, working as one unit, affected by the innovation enablers. The proposed model illustrates factors enabling the work of the global innovation team’s work from four perspectives, that is, from the perspectives of the organisation, the team and the individual, all of whom are surrounded by a global dimension and connected through technology. It illustrates that international influences and circumstances affect global innovation teams and that technology both makes the practical global innovation team functional and enables its members to interact.

Figure 1 The global innovation team, its context and surrounding perspectives. Following the logic of Johnsson (2017a, p.9)’s, i.e., organising the identified factors and the factors of Clark et al. (2019)’s based on how the enables are addressed the innovation team’s work, the following structure emerged (Table 1).

Table 1 Factors enabling global innovation teams

Factors enabling global innovation teams

Factors Count

total

Perspective

Global Org. Inn. team Member

Management 74 Z X, Y, Z Y, Z Collaboration 59 Z X, Y Y, Z Mindset 53 X, Y Characteristics 43 Y Y Knowledge management 40 X, Y, Z Trust 40 Z Y, Z Y, Z Technology 38 Z Y, Z Y, Z Y, Z Communication 37 Z Z Y, Z Y, Z Member Member Member Member Global perspective Organisational perspective Innovation team perspective Innovation team member perspective Interaction enabled through technology Technological boundaries

Culture 26 Z X, Y, Z X, Y, Z Y, Z Climate 20 X X Dedication 20 X, Y Incentives 20 X Interaction 19 Z Y, Z Knowledge 16 Z X, Z Empowerment 15 X, Y X, Y Process 15 X Education 12 X Capabilities 10 X Human resources 10 X Awareness 9 X Entre-/intrapreneurship 9 X Strategy 9 X Economy 8 X X Time 7 X X Synchronicity 7 Y Y Satisfaction 5 Y Task structure 4 Y Y Need 3 X Sense-making 3 Z Z Dispersion 3 Y Y

X = Johnsson (2017a), Y = Clark et al. (2019), Z = This literature review

In this work, I strive to reflect the identified papers’ focus and not what I personally think affects global innovation work or how an individual person might interpret it in practical use. However, as seen above, the identified enablers are intertwined and related to each other, not easy to isolate, which could be considered a limitation of the study. For example, culture is defined as people’s behaviour in a specific context, which reflects their shared values and norms, conscious or unconscious (Nanda and Singh, 2009). However, it is the individual who contributes to the culture, directly or indirectly affecting, for example, the global innovation team’s collaboration, communication or interaction. A global perspective requires cultural influences to be handled in new ways that do not consider organisational or team culture in isolation. Even though the organisation is the same, management or employee style/behaviour may differ depending on the culture, which can cause misunderstandings or conflicts. In this literature review, it became clear that the use of technology distinguishes global innovation teams from local innovation teams. Through the use of technology, global innovation team members can not only communicate but also interact and build relationships over distance (Fruchter and Bosch-Sijtsema, 2011),

potentially making the dispersed team members a team if they pass through all necessary phases (Tuckman, 1965; Wheelan et al., 2020), even reach to the high-performing phase (Olaisen and Revang, 2017).

6 Contribution

This study contributes to prior research on teams, virtual teams and innovation teams in that factors enabling global innovation teams’ work are identified. A new model is proposed that includes global and technical aspects, adding knowledge to previous research and bringing understanding to the innovation management community, where its results can be further discussed. An attempt to organise all identified factors revealed a fairly complex picture that opens up further research avenues. First, analysing the relevance and potential replacement of other factors enabling global innovation teams’ work should be evaluated through empirical studies. Second, this research does not evaluate or assess the enablers’ importance for or effect on global innovation teams’ innovation work. Again, this can be further researched through empirical studies. Third, methodologies for how to create global innovation teams can be explored using the content of this research as a basis.

7 Practical implication and future work

Based on this literature review, practitioners and teachers of innovation management can develop programmes that either educate managers and innovation teams, preparing them for global innovation team work, or educate students, helping them master the knowledge on a theoretical and practical level. To whichever end this work is used, the limitations of the study should be considered, as new knowledge is constantly being developed.

References

Alge, B.J., Ballinger, G.A. and Green, S.G. (2004), “REMOTE CONTROL: PREDICTORS OF ELECTRONIC MONITORING INTENSITY AND SECRECY”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 57 No. 2.

Alsharo, M., Gregg, D. and Ramirez, R. (2017), “Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust”, Information and Management, Elsevier B.V., Vol. 54 No. 4, pp. 479–490. Batarseh, F.S., Daspit, J.J. and Usher, J.M. (2018), “The collaboration capability of global virtual

teams: relationships with functional diversity, absorptive capacity, and innovation”,

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, Taylor and

Francis Ltd., Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 1–10.

Batarseh, F.S., Usher, J.M. and Daspit, J.J. (2017a), “Absorptive capacity in virtual teams: Examining the influence on diversity and innovation”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 21 No. 6, available at:https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2016-0221.

Batarseh, F.S., Usher, J.M. and Daspit, J.J. (2017b), “Collaboration capability in virtual teams: Examining the influence on diversity and innovation”, International Journal of Innovation

Management, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte Ltd, Vol. 21 No. 4, available

at:https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919617500347.

Bosch-Sijtsema, P.M. and Haapamäki, J. (2014), “Perceived enablers of 3D virtual environments for virtual team learning and innovation”, Computers in Human Behavior, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 37, pp. 395–401.

Boyatzis, R.E. (1998), Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code

Development, Sage.

Castellano, S., Davidson, P. and Khelladi, I. (2017), “Creativity techniques to enhance knowledge transfer within global virtual teams in the context of knowledge-intensive enterprises”,

Journal of Technology Transfer, Springer New York LLC, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 253–266.

Charlier, S.D., Stewart, G.L., Greco, L.M. and Reeves, C.J. (2016), “Emergent leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel investigation of individual communication and team dispersion

antecedents”, Leadership Quarterly, Elsevier Inc., Vol. 27 No. 5, pp. 745–764. Chen, M., Liou, Y., Wang, C.W., Fan, Y.W. and Chi, Y.P.J. (2007), “TeamSpirit: Design,

implementation, and evaluation of a Web-based group decision support system”, Decision

Support Systems, Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 1186–1202.

Creasy, T. and Carnes, A. (2017), “The effects of workplace bullying on team learning, innovation and project success as mediated through virtual and traditional team dynamics”,

International Journal of Project Management, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 964–977.

Dadriyansyah, G., Ibrahim, A. and Hassan, M.G. (2010), “Virtual Integration as an Approach to Engender Product Innovation and Accelerate Product Development Time: A Literature Analysis”, 17th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering

Management : October 29-31, Xiamen, China, IEEE.

Dekker, D.M., Rutte, C.G. and van den Berg, P.T. (2008), “Cultural differences in the perception of critical interaction behaviors in global virtual teams”, International Journal of Intercultural

Relations, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 441–452.

Derven, M. (2016), “Four drivers to enhance global virtual teams”, Industrial and Commercial

Training, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 1–8.

Duus, R. and Cooray, M. (2014), “Together We Innovate: Cross-Cultural Teamwork Through Virtual Platforms”, Journal of Marketing Education, SAGE Publications Inc., Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 244–257.

Ebrahim, N.A., Ahmed, S. and Taha, Z. (2009), “Virtual Teams: a Literature Review”, Australian

Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 2653–2669.

Eubanks, D.L., Palanski, M., Olabisi, J., Joinson, A. and Dove, J. (2016), “Team dynamics in virtual, partially distributed teams: Optimal role fulfillment”, Computers in Human

Behavior, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 61, pp. 556–568.

Franz, T.M. (2012), Dynamics and Team Interventions: Understanding and Improving Team

Performance, Wiley-Blackwell.

Fruchter, R. and Bosch-Sijtsema, P. (2011), “The WALL: Participatory design workspace in support of creativity, collaboration, and socialization”, AI and Society, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 221–232.

Gibson, C.B. and Gibbs, J.L. (2006), Unpacking the Concept of Virtuality: The Effects of

Geographic Dispersion, Electronic Dependence, Dynamic Structure, and National Diversity on Team Innovation, Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 51, available at:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25426915.

Gressgård, L.J. (2011), “Virtual team collaboration and innovation in organizations”, Team

Performance Management, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 102–119.

Hackman, J.R. (2002), Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Hammond, J.M., Harvey, C.M., Koubek, R.J., Gilbreth, L.M. and Darisipudi, A. (2005),

Distributed Collaborative Design Teams: Media Effects on Design Processes, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION, Vol. 18.

Han, S.J., Chae, C., Macko, P., Park, W. and Beyerlein, M. (2017), “How virtual team leaders cope with creativity challenges”, European Journal of Training and Development, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 261–276.

Haywood, M. (1998), Managing Virtual Teams: Practical Techniques for High-Technology Project

Managers, Artech House.

Henttonen, K. and Blomqvist, K. (2005), “Managing distance in a global virtual team- the evolution of trust through technology mediated relational communication”, Strategic

Holton, J.A. (2001), Team Performance Management, Vol. 7.

Hosseini, M.R., Bosch-Sijtsema, P., Arashpour, M., Chileshe, N. and Merschbrock, C. (2017), “A qualitative investigation of perceived impacts of virtuality on effectiveness of hybrid construction project teams”, Construction Innovation, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 109–131.

Jasper, S. (2019), The Effect of Time Zone Disparity on the Performance of Dispersed Innovation

Teams in the Australian Biotechnology Industry.

Johnsson, M. (2017a), “Innovation Enablers for Innovation Teams-A Review”, Journal of

Innovation Management Johnsson JIM, Vol. 5, pp. 75–121.

Johnsson, M. (2017b), “Creating High-performing Innovation Teams”, Journal of Innovation

Management Johnsson JIM, Vol. 5, pp. 23–47.

Karlsson, L., Löfstrand, M., Larsson, A., Törlind, P., Larsson, T., Elfström, B.-O. and Isaksson, O. (2005), “INFORMATION DRIVEN COLLABORATIVE ENGINEERING: ENABLING FUNCTIONAL PRODUCT INNOVATION”, CCE ’05 ; the Knowledge Perspective

Incollabotative Engineering, Sopron, Hungary, 14t-15th April, 2005.

Katzenback, J.R. and Smith, D.K. (1993), The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance

Organization, Harvard Business School Press.

Klitmøller, A. and Lauring, J. (2013), “When global virtual teams share knowledge: Media richness, cultural difference and language commonality”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 48 No. 3, pp. 398–406.

Lahiri, N. (2010), “Geographic Distribution of R&D Activity: How Does It Affect Innovation Quality?”, The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 53 No. 5, pp. 1194–1209. Laine, T., Korhonen, T. and Martinsuo, M. (2016), “Managing program impacts in new product

development: An exploratory case study on overcoming uncertainties”, International

Journal of Project Management, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 717–733.

Larsson, A. (2003), Making Sense of Collaboration: The Challenge of Thinking Together in Global

Design Teams.

Larsson, A. (2007), “Banking on social capital: towards social connectedness in distributed engineering design teams”, Design Studies, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 605–622.

Larsson, A., Törlind, P., Mabogunje, A. and Milne, A. (2002), “Distributed design teams: embedded one-on-one conversations in one-to-many”, Common Ground : Design Research

Society International Conference 2002 Held 5-7 September 2002, London, UK, Staffordshire

University Press, p. 234.

Lencioni, P. (2002), The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Li, V., Mitchell, R. and Boyle, B. (2016), “The Divergent Effects of Transformational Leadership on Individual and Team Innovation”, Group and Organization Management, SAGE Publications Inc., Vol. 41 No. 1, pp. 66–97.

Lombardo, M.M. and Eichinger, R.W. (1995), The Team Architect User’s Manual, Lominger Limited., Minneapolis.

Manning, S., Larsen, M.M. and Bharati, P. (2015), “Global delivery models: The role of talent, speed and time zones in the global outsourcing industry”, Journal of International Business

Studies, Palgrave Macmillan Ltd., Vol. 46 No. 7, pp. 850–877.

Manole, I. (2014), Virtual Teams and E-Leadership in the Context of Competitive

Environment-Literature Review, Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People, Vol. 3.

Meslec, N. and Curşeu, P.L. (2015), “Are balanced groups better? Belbin roles in collaborative learning groups”, Learning and Individual Differences, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 39, pp. 81–88. Morris, S. (2008), “Virtual team working: Making it happen”, Industrial and Commercial Training,

Vol. 40 No. 3, pp. 129–133.

Muethel, M., Siebdrat, F. and Hoegl, M. (2011), When Do We Really Need Interpersonal Trust in

Globally Dispersed New Product Development Teams?

Nanda, T. and Singh, T.P. (2009), “Determinants of creativity and innovation in the workplace: a comprehensive review”, International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 84–106.

Ocker, R.J. and Hiltz, S.R. (2012), “Learning to work in partially distributed teams: The impact of team interaction on learning outcomes”, Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 88–97.

Olaisen, J. and Revang, O. (2017), “Working smarter and greener: Collaborative knowledge sharing in virtual global project teams”, International Journal of Information Management, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 1441–1448.

Olson, J. and Olson, L. (2012), “Virtual team trust: Task, communication and sequence”, Team

Performance Management, Vol. 18 No. 5, pp. 256–276.

Olson, J.D., Appunn, F.D., Mc Allister, C.A., Walters, K.K. and Grinnell, L. (2014), “Webcams and virtual teams: An impact model”, Team Performance Management, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 20 No. 3–4, pp. 148–177.

Painter, G., Posey, P., Austrom, D., Tenkasi, R., Barrett, B. and Merck, B. (2016), “Sociotechnical systems design: coordination of virtual teamwork in innovation”, Team Performance

Management, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., Vol. 22 No. 7–8, pp. 354–369.

Peñarroja, V., Orengo, V., Zornoza, A., Sánchez, J. and Ripoll, P. (2015), “How team feedback and team trust influence information processing and learning in virtual teams: A moderated mediation model”, Computers in Human Behavior, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 48, pp. 9–16. Pinar, T., Zehir, C., Kitapçi, H. and Tanriverdi, H. (2014), “The Relationships between Leadership

Behaviors Team Learning and Performance among the Virtual Teams”, International

Business Research, Canadian Center of Science and Education, Vol. 7 No. 5, available

at:https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v7n5p68.

Robert, L., Denis, A. and Hung, Y.T. (2009), “Individual swift trust and knowledge-based trust in face-to-face and virtual team members”, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 241–279.

Rousseau, V., Aubé, C. and Tremblay, S. (2013), “Team coaching and innovation in work teams: An examination of the motivational and behavioral intervening mechanisms”, Leadership

and Organization Development Journal, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 344–364.

Rubin, I.M., Plovnick, M.S. and Fry, R.E. (1977), Task Oriented Team Development, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Sack, R.L. (2009), “The pathophysiology of jet lag”, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 102–110.

Scott, C.P.R. and Wildman, J.L. (2015), “Culture, Communication, and Conflict: A Review of the Global Virtual Team Literature”, Leading Global Teams, Springer New York, pp. 13–32. Seshadri, V. (2019), “Article ID: JOM_06_01_013 Cite this article Vinita Seshadri and Dr.

Elangovan N, Innovator Role of Manager in Geographically Distributed Team”, A Review

Journal of Management, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 122–129.

Tuckman, B.W. (1965), “Developmental sequence in small groups”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 63 No. 6, pp. 384–399.

Tzabbar, D. and Vestal, A. (2015), “Bridging the social chasm in geographically distributed R&D teams: The moderating effects of relational strength and status asymmetry on the novelty of team innovation”, Organization Science, INFORMS Inst.for Operations Res.and the Management Sciences, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 811–829.

Wheelan, S.A., Akerlund, M. and Jacobsson, C. (2020), Creating Effective Teams, SAGE Publications.