THE

HAMBURG-ST.-PAULI-BRAND-DIALECTIC

Examining Hamburg’s city branding approach and its effects

on the local Red-Light-District

Miriam Green

Urban Studies

Master’s Urban Studies (Two-year master) 30 Credits

Spring 2019

THE

HAMBURG-ST.-PAULI-BRAND-DIALECTIC

Examining Hamburg’s city branding approach and its effects

on the local Red-Light-District

Miriam Green

Executive Summary

“What is certain is that the question of […] re-making a landscape of prostitution in the city […] needs to be viewed as part of a changing, global discourse on the nature of contemporary

cities” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 114).

Prostitution – associated with well-known Red-Light Districts – has for a long time been seen as “a significant urban activity that relates to other economic and social functions of the city [and contributes] […] to the cognitive image of a city held by both residents and non-residents, even those who have never frequented them” (Ashworth, White & Winchester 1988, p. 201). It is therefore no surprise that within the neoliberal framework of inter-city competition, these once notorious districts, commonly associated with crime and violence, ascended into spaces of entertainment and consumption, neatly aligning with entrepreneurial city branding strategies. The Reeperbahn, Hamburg’s famous mile of sin, located within the district of St. Pauli is no exception to this rule. As a place traditionally located outside Hamburg’s social and physical city limits, it is nowadays frequented by thousands of tourists and party seekers, drawn in by the area’s myths and shady reputation (Khan 2012). Actively fostering the (economic) attractiveness of the so-called Kiez has long been part of Hamburg’s city politics and was reinforced with the creation of the Hamburg Brand Marketing Strategy in 2002, where the Entertainment Mile Reeperbahn alongside Hamburg’s Pulsating Scenes became two of the key success modules in branding the city. The repercussion this has had not only for the district and its inhabitants but specifically for the red-light industry has largely been understudied.

This Master’s Thesis therefore, aims at studying the general effects of city branding, such as displacement and conflict over spatial uses in the face of Over-Tourism and re-development strategies. Looking at the specific case of the Reeperbahn, it closes the gap of the somewhat understudied effects of gentrification on St. Pauli’s unique culture. By interviewing different local stakeholders, conducting a broad literature review as well as undertaking field work, the Hamburg-St.-Pauli-Brand-Dialectic will be analyzed subsequently, showing, how the Hamburg Brand and the city as a whole have profited from St. Pauli’s reputation and what consequences this has had in turn for the district.

Key Words: City Branding, Tourism, Gentrification, Red-light District, Prostitution, Sex Work,

Content

Executive Summary ... 2

Acknowledgements ... 5

Introduction ... 6

1. Research Status ... 7

1.1 The Neoliberal City ... 7

1.2 The Creative City... 8

1.3 The Revanchist City ... 9

1.4 The Dubiousness of Public Space ... 10

1.5 Prostitution and the City ... 11

1.6 Spatial Dimensions of Sex Work – Red-Light Districts (RLDs) ... 14

1.7 Social Dimensions of Sex Work ... 15

2. Research Methods ... 18 2.1 Ethnographic Research ... 19 2.1.1 (Participant) Observations ... 19 2.1.2 Recordings ... 21 2.1.3 Interviews ... 21 2.2 Content Analysis ... 23 2.3 Limitations ... 24

3. Hamburg: From a social to an entrepreneurial city ... 26

3.1 Development of Hamburg ... 27

3.2 Hamburg – an entrepreneurial city ... 29

3.3 City Branding ... 30

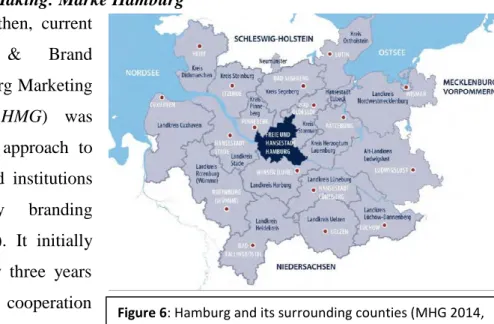

3.4 Hamburg in the Making: Marke Hamburg ... 31

3.5 Counter movements ... 38

4. Reeperbahn – St. Pauli ... 40

4.1 The district in numbers ... 40

4.2 Early developments ... 44

4.3 Upswings and downfalls ... 45

4.4 The contemporary St. Pauli ... 46

5. Prostitution in Hamburg ... 53

5.1 Gesetz zur Regelung der Rechtsverhältnisse der Prostituierten – ProstG ... 53

5.2 Prostituiertenschutzgesetz and recent developments ... 54

5.4 Fighting stigmatization through education ... 57

6. Trends and developments at the Reeperbahn ... 60

6.1 Business Improvement District Reeperbahn+ ... 60

6.2 Rent development ... 66 6.3 Re-development strategies ... 71 6.3.1 Esso Häuser ... 75 Conclusion ... 79 Literature ... 82 Picture Sources ... 91 Annex ... 93 1. Glossary ... 93 2. Interview Guides ... 99

3. City Guide Review ... 101

4. Word Cloud Table ... 107

5. Observations... 110

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Guy Baeten, for his advice, feedback and foremost the liberties he granted me in carrying this work out as seen fit. My grateful thanks are also extended to Professor Els Enhus and Lucas De Melo Melgaço, who excellently introduced me to the field of criminology and laid the groundwork for my research question. Their valuable insights have fed this work in many instances. In this context I would also like to thank Malmö University for making my exchange in Brussels possible, which granted me many new opportunities.

I am also particularly grateful for the support of my interview partners, Julia Staron, Stefan Nöthen, Margot Pfeiffer, Steffen Jörg, Josefa Nereus and the Anonymous Interview Partner, whose insights have enriched this work and truly turned it into what it is.

Finally, I wish to thank my friends, co-workers and roommates for their constant support, interest and encouragement, guiding me and making me believe in the content and the scope of this work. In this context I would like to especially extend thanks to Russell, Vivi and Nora for taking the time to read through my work and give me extensive and valuable feedback. This, and more of course goes foremost for my mother, who has always supported me and enabled me to come this far.

Introduction

St. Pauli, home to the world-famous Reeperbahn, has traditionally been a place physically

and socially outside of Hamburg’s city limits. Whereas originally, people felt ashamed about living here, today the district is frequented by thousands of tourists or party seekers each weekend, mainly attracted by the area’s myths and shady reputation (Khan 2012). The repercussion this has had, not only for the district and its inhabitants but specifically for the red-light industry, has largely been understudied.

Within the paradigm of globalization, cities all over the world have entered a state of competition, where residents, infrastructure and businesses become assets to boost economic growth. “Planners now have a set of neoliberal tools and policies at their disposal that goes largely uncontested and is applied worldwide to different degrees and in different forms” (Baeten 2017 p. 108). Some of these tools include city branding, urban development projects or cooperation between the state and private investors to create an urban setting attractive to the so-called Creative Class. This has also been the case in Hamburg, where the neoliberal agenda has been pushed ever since the 1980s, leading to the implementation of a strategic marketing plan based upon twelve so-called success modules in 2009. Next to economic, cultural and aesthetic aspects, these modules also included Pulsating Scenes and The

Entertainment Mile Reeperbahn, covering large parts of the formerly working-class and

transition district St. Pauli. Met by an immense uproar, the Hamburg Marketing GmbH faced much criticism, when the Creative Class responded with the Not In Our Name Manifesto, refusing to be instrumentalized as a location factor and instead demanding a shift towards more socially sound planning and development strategies. While this movement gained much (international) attention, effects for the Reeperbahn have largely been left undebated.

This Master’s Thesis therefore aims at studying the general effects of city branding, such as displacement and conflict over spatial uses in the face of Over-Tourism and re-development strategies. Looking at the specific case of the Reeperbahn, it closes the gap of the somewhat understudied effects of gentrification on St. Pauli’s unique culture. By talking to different local stakeholders, conducting a broad literature review, as well as undertaking field work, the Hamburg-St.-Pauli-Brand-Dialectic will be analyzed subsequently, showing how the Hamburg Brand and the city as a whole have profited from St. Pauli’s reputation.

1. Research Status

“A spectre has been haunting Europe since US economist Richard Florida predicted that the future belongs to cities in which the ‘creative class’ feels at home. […] Many European capitals are competing with one another to be the settlement zone for this ‘creative class’”

(NION 2010, p. 323)

This rise of entrepreneurial cities, largely discussed by David Harvey in the 1980s (Harvey 1989), based upon attracting more jobs and investment while functioning as spaces of consumption, emerged within a post-modernistic paradigm from the 1975s onwards. Here, post-industrial modes of production, the emerging service industries and new, distinctive consumer demands took over, creating the need for different lifestyles and spaces (Zukin 1998). “Cities are no longer seen as landscapes of production but as landscapes of consumption” (ibid., p. 825), catering to new patterns of leisure, culture and travel. Urban planning increasingly started considering these trends, catering to specific population segments, which resulted in (unwanted) consequences such as the rise of low-paid jobs, a decline in economic viability and global competition trends (ibid.). This cultural turn paired with the rise of a symbolic economy, caused for a new social divide based upon structural and institutional inequalities. Urban space in this context has become the battlefield of class struggles, actively fueled by neoliberal politics.

1.1 The Neoliberal City

Neoliberalism is based upon

“[…] an unbridled belief in the natural superiority of the market to allocate land in the most efficient way; a principled distrust in state planning per se as it distorts the market; the mobilization of the state to dismantle its own planning functions; the outsourcing of planning functions to the private sector; and the reinforcement of the authoritarian state to fulfil repressive functions (such as forced displacement) that private actors cannot achieve” (Baeten 2017, p. 106).

In the early 1980s, neoliberal politics pushed for the state’s continuous restriction (roll-back Neoliberalism), followed by the so-called roll-out Neoliberalism from the 1990s onwards, retracting the state to combat emerging social downfalls. The present stage of Neoliberalism has been coined by Keil as “roll-with-it neoliberalization” (Keil 2010), where neoliberal politics have largely been accepted as the status quo, unquestionable and untouchable. For Swyngedouw, this post-political stage of acceptance, where “neoliberal governmentality […] has replaced debate, disagreement and dissensus with a series of technologies of governing

that fuse around consensus, agreement and technocratic management” (Swyngedouw 2007, p. 59), has caused for a general state of acceptance, without any alternatives to the current political, economic or social system. In this context political freedom and choice become merely an illusion, since true politics are shaped by fundamental conflict, aiming for revolutionary change. Translated into space, this means that “Urban regions […][have become] the collective actor and strategic terrain in the globalized struggle for location of individual enterprises, sectors of the economy, branch plants of multinational corporations […] and so forth […] [being] both prime sites of and major laboratories of neoliberal restructuring and state rescaling” (Keil 2010, p. 238). Competitive advantages, in the form of hard and soft location factors, have become key for the economic viability of cities.

1.2 The Creative City

The works of Richard Florida, published around the turn of the century, became a key tool of urban entrepreneurialism and how to make cities more profitable. Based upon a range of vague assumptions concerning the motivation for labor migration, Florida claimed to have found a one-fits-all recipe for (de-industrializing) towns, turning them into suitable hotbeds for the Creative Class. “In Richard Florida’s social and economic theory this creative class is assumed to constitute a new economic power and the so-called creative capital of a society, which can be regarded to be the most relevant capital for economic growth in general”

(Zenker 2009, p. 23), since their creativity and innovation will attract businesses, foster

growth and ensure competitiveness. In order to attract this Creative Class, the three Ts Technology, Talent and Tolerance are needed (Florida 2004). “Although FLORIDA’S approach received strong criticism from different scientific disciplines, his perspective has been readily qualified via the implementations of new creativity-based political actions initiated by local and regional authorities” (Pohl 2008, p. 317), aiming at elite consumption and creative niches. It has led to a multiplicity of problems such as the erosion of public space through commercialization and privatization, the return of the city of rents based upon financialization and rentiership as well as gentrification and social inequality (Smith 1996; Lees, Bang Shin & López-Morales 2015). Much has been theorized around gentrification since its proclamation in the 1960s (Glass 1964) and it has become clear that delineating its particular features is not clear-cut. “Contrary to early formulations, gentrification does not occur only in inner cities, it does not manifest itself only through renovation, it is not only market-driven, it is not limited to residential spaces, and it is not even limited to specific classes” (Hedin et. al 2012). The textbook example of post-industrial space acquiring charm and uniqueness through the invasion of creative pioneers, eventually attracting so-called Young Urban Professionals and

re-development strategies, driving out its original population, has long become much more complex.

1.3 The Revanchist City

Within the larger frame of Neoliberalism, policing has started to comply with trends of inter-city competition, following the Culture of Control (Garland 2002) by policing especially inter-city centers in order to assure their impeccable appearance. This “’de-personalization of preventive strategies’” (Künkel 2017, p. 731), based upon spatial and situational interventions have led to refraining from social prevention strategies, and efforts have been placed on situational crime prevention strategies such as Zero Tolerance Policing (ZTP). ZTP, emerged in 1990s New York under mayor Giuliani, trying to revitalize the city by creating a clean and orderly outside appearance following the Broken Window Theory. According to this theory, seemingly neglected areas, such as houses containing broken windows, would appear less supervised and eventually attract more criminal activities (Wilson & Kelling 1982). ZTP would therefore punish so-called quality of life offenses (minor activities seen as harmful such as loitering or graffiti), in order to deter potential offenders and induce a revaluation of public space (Belina 2011). Its vagueness and flexibility turned ZTP into a highly political and social tool, feeding into discourses around sociological and environmental impacts on criminal behavior as well as fear of crime (Belina & Helms 2003, p. 1848). Consequently, it led to the increased over-policing of marginalized population segments, held responsible for urban erosion, instead of being seen as victims thereof. This process has been intensified by the idea of a “revanchist city” (Hubbard et. al 2008, p. 372), which “[…] claims that the city has been stolen from the White middle class by all sorts of minorities” (Belina & Helms 2003, p. 1846). Consequences have been even stronger over-policing and efforts to clean city centers and to give assets to especially old, industrial cities to compete within the inter-city market. One can therefore pinpoint “[…] the discursive link between urban entrepreneurialism and ZTP as consisting of an initially straightforward assertion that crime and fear of crime are bad for business in the city centre and therefore a significant obstacle for successful interurban competition” (ibid., p. 1850). Traditionally, neoliberal politics have been known for hollowing out the state, but within the field of policing the opposite is true, turning police (inter)action into an increasingly wanted and provided public service. However, the idea of safety remains shaped by the needs of the majority, feeding into deeply embedded structural inequalities, creating so-called coercive care (Künkel 2017, p. 742). “The whole approach is ideological as it arguably addresses problems of crime and fear of crime, and in

fact serves the purpose of an aesthetic upgrading of city centres” (Belina & Helms 2003, p. 1862).

1.4 The Dubiousness of Public Space

As already mentioned above, public space makes up an important area of tension when it comes to the spatial manifestation of neoliberal politics. Starting by its mere definition, it remains questionable if space can ever truly be public since it is always based upon (land)use struggles. Belina, for example, claims that “[…] public/private differentiation emerges as a social product, in which are inscribed power relations and meaning that actors can exploit by themselves by exerting strategic influence on this differentiation. In this sense, the public/private differentiation represents a strategy that can be used in socio-spatial conflicts” (Belina 2011, p. 15). The idealization of publicly accessible and usable space then becomes a tool to divert from other underlying problems and is essentially reinforcing structural inequalities, since “[…] assumption of an all-inclusive public sphere is and has always been an ideological tool for the few who are and were allowed to participate, […] [and denies struggles] about the placement of individuals and groups within socio-spatial power relations that are produced by structuring categories of class, race, gender, sexuality, and age” (ibid., p. 16). Contrary to public perception no space is accessible to everyone in the same manner since the ones in power will always determine its looks, purpose and usage, according to what is claimed to be the greater good. Consequently, minority and marginalized groups are banned from and often held responsible or criminalized for causing discomfort, essentially legitimizing their exclusion, where “[…] debates and practices concerning the treatment of racialized bodies, the poor, and other undesirables whose exclusion and expulsion from urban spaces are legitimized with reference to the quality of ‘public space’ in the context of ‘broken windows’ policing” (ibid., p. 13). These strategies largely divert from invisible crimes of the powerful by holding powerless entities responsible for visible and targetable actions (see the Crime Prism: Lanier, Henry & Anastasia 2015). “The discussion should instead be about capitalism, racism, and their neoliberal versions, which entail the punishment of the poor” (Belina 2011, p. 22), or other minorities such as homeless people, drug addicts and prostitutes. Their supposed status of self-inflicted poverty and misery is used as legitimization to push these people towards the edge of society. That society entails a variety of lifestyles and people might deliberately choose to sleep on the streets or offer sexual services for money is often unthinkable within society’s rigid norms and values, creating severe socio-spatial consequences.

1.5 Prostitution and the City

Within the growing field of criminology much attention has been given to policing, police protection and preventative measures (Trevor, Newburn & Reiner 2017) as well as their socio-political consequences (Beck 1992; Garland 2002; Newburn 2007b). However, other segments, such as sex work, remain largely understudied. Sex work is one of the oldest existing occupations, established at least in the 18th century (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008), with its extent, geographic location as well as socio-political handling, differing over space and time due to problems of definition, localization and a general lack of social and political acceptance.

Throughout history, sexual displays in public (e.g. nudity, transvestism or homosexuality) have always been a topic of discussion, often associated with obscenity and profanity. Consequently, prohibition or censorship thereof was imposed early on, directly criminalizing sex workers. Where restrictions were not fruitful, so-called “’politics of concealment’” (Hubbard et. al 2008, p. 366) were applied, limiting the visibility of said activities through spatial marginalization by command-and-control or zoning techniques. From the 1990s onwards, rising demands and social support for sex work moved the debate on its legalization into the public realm in Europe (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008; Aalbers & Sabat 2012). Common responses led to the pursuit of either complete prohibition (the British Model), its abolition (the Swedish Model) or its legalization (the Dutch Model).

The British Model is based upon growing legislations from the 1950s onwards, increasingly penalizing both, procurers as well as solicitors of sexual activities. However, certain tolerance zones e.g. in the form of red-light districts, have often remained, where sex work has been allowed under strict supervision. Unfortunately, these zones of tolerance are usually subject to “’moral authoritarianism’” (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008, p. 145), underlying struggles over land use, over-policing and vigilantism. The introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs) within Britain’s ZTP strategies in the late 1990s, have increased the control of Toleration Zones even further. “Collectively, these laws have created a situation where it has proved virtually impossible for women to sell sex without breaking a number of laws” (ibid. p. 144). Furthermore, further stigmatization is fueled by the equation of human trafficking and sex work, leading to displacement and worsening working conditions. Therefore, “As has been argued before, removing sex work from the public space will not reduce the demand for sexual services or prevent the exploitation of sex-workers” (Van Liempt & Chimienti 2017, p. 1576), since recent figures show, that “the off-street trade has

not only grown in size and scope but has also steadily spread out across London into the suburbs and Home Counties” (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008, p. 148).

In Sweden, prostitution was decriminalized in 1964 and sex workers were no longer portrayed as socially deviant or a burden to the social health care system, uncontrollably spreading sexually transmitted diseases. However, in the years to follow, liberalization faced a lot of critique, especially in the context of European expansion and growing anxieties around trafficking and forced prostitution. Eventually, this prominent counter narrative lead to the Act on Prohibiting the Purchase of Sexual Services in 1998, criminalizing the buyer of sex, instead of its provider. The procurement of sexual services has ever since been punishable with fines or even imprisonment. Besides taking control of the matter, this act further reinforced national identity, conveying the impression of Sweden being able to take a stance for its values. While some might prefer this compromise over complete prohibition, its effects are all but the same, since sex work might disappear from the public sphere, but is merely displaced to less visible, less revised and unsafe spaces. Consequently, overall working conditions and public acceptance have dropped immensely (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008).

The Dutch Model (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008; Aalbers & Sabat 2012) generally sees sex work as a legal activity, however, an activity underlying extensive regulation. Until the 1980s, public display of sex work was also highly restricted within the Netherlands. However, counter movements led by the organization Rode Draad started challenging popular perceptions: “Sex workers wanted to have sex work recognized as a service, a type of work, and themselves as legal workers and not as ‘fallen’ women or victims” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 121). Therefore, from 1997 onwards, prostitution was officially legalized with the aim of fighting organized crime, forced prostitution, trafficking and illegal migration. Whereas legally, this led to further liberalization of sex workers, morally it enhanced their stigmatization. “Denying the idea that immigrant women might voluntarily become prostitutes, political debate figured all non-EU prostitutes as trafficking victims and, in the same move, as illegal migrants” (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008, p. 142). Increasing obligations, such as official registration and supervision, aiming at steering and improving overall working conditions, essentially had a contrary effect. Especially the more vulnerable demographics were pushed towards informality, trying to avoid tax payments and inspections, and protecting their anonymity and safety. “The result is that foreign non-EU prostitutes become the main target of the police, they often begin to rely on pimps to regulate their work,

have less choice in the customers they choose, in the prices they set and in general, in the conditions under which they work” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 121). It shows that the Dutch Model, while allegedly having the liberalization of sex workers at heart, is in fact partially leading to their further imprisonment. A more holistic approach on liberalization would be needed, in order to break the social barriers of marginalization and stigmatization, truly elevating sex work as a full job like any other. Otherwise, liberalization will only remain a tool to exert further socio-spatial control (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008; Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015).

The variety of models, as well as tendencies of re-scaling political power within the EU, have created a highly but unevenly regulated landscape of sex work shaped by discretion and selective enforcement. However, this complexity also comes down to the very nature of sex work, a very broad work field, were its core elements are hard to pinpoint. Sex work covers more than just sex for money, and rather includes a variety of activities such as escort services, striptease or erotic massages. At its core, it is based upon the commodification of sexual services and can happen in the open or behind closed doors (Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015). Whereas offline, outdoor and street-based prostitution is rather straight-forward, the organization of indoor activities can vary according to the service provided, ranging from big brothels over agencies to self-employed residential prostitution.

In this context it is important to acknowledge the changes increasing digitalization brought on in terms of possibilities and menaces. New, different forms of sexual encounters increasingly move sex work into a sphere which lacks (public) supervision, granting consumers increasing anonymity while completely exposing their suppliers. Furthermore, growing online sex work is taking a toll on traditional Red-Light Districts, draining them of customers and causing re-orientation.

1.6 Spatial Dimensions of Sex Work – Red-Light Districts (RLDs)

“Since the nineteenth century, prostitution districts – often describe as vice districts – have been features of cities” (Van Liempt & Chimienti 2017, p. 1569), serving as gathering places for marginalized demographics as well as otherwise unwanted activities. Homelessness, criminality, poverty and drug addiction have therefore often co-existed alongside red-light activities. This might be due to the fact that moral acceptance is much higher in these areas but is also commonly led back to the fact that these often poor RLDs don not have the means to keep unwanted activities out. Furthermore, the spatial concentration of deviance is often actively fostered by politicians, which “may have grown accustomed to dumping socially undesirable functions in these neighborhoods” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 115).

Generally speaking, “Red-light districts are areas in cities or towns that are themed around sex […] [and] can be widely known outside the immediate area” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 114). While similar at the core, their configuration as well as their target group can vary over space and time, where each demographic brings along different necessities, translating into distinctive access, opportunities and constraints. Traditionally, big cities have largely entailed inner city prostitution, where RLDs have emerged in so-called transition or buffer zones between the more affluent and blighted areas of the city. Here, red-light activities often find space in former working-class or industrial areas, marked by poverty, high turn-over and low real estate prices. Furthermore, RLDs are often strategically positioned close to areas of transit e.g. airports, harbors or major train stations and try to cluster a multitude of sex-related activities and infrastructure, profiting from agglomeration economies (Martin 2008). “The services of prostitutes have always been in particular demand by travelers and it is not surprising that transport nodes in the city should be attractive locations” (Ashworth, White & Winchester 1988, p. 208). Due to their necessity of drawing in customers on the one hand and their sometimes complicated legal status on the other hand, they are dependent simultaneously on high and low visibility. “It is this paradox between visibility and invisibility that is characteristic of all red light districts” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 115). Since “soliciting in public is understood by sex workers to be both a risk to their personal safety as well as to their sense of self” (Hubbard & Sanders 2003, p. 87), RLDs also function as safe spaces, providing privacy, acceptance and a feeling of community.

Challenging the traditional characteristics of RLDs, increasing economic pressures has recently turned many central red-light zones into fully commercialized entertainment districts, offering a “complete package of sex-related activities” (Ashworth, White & Winchester 1988, p. 204). Essentially, these districts target mainly tourists, providing them with stores, clubs,

bars and entertainment venues, beyond purchasable sex. However, economic pressure has also led to the extension of RLDs in neglected, blighted and run-down areas, alongside poverty, criminality, drugs and organized crime, especially in countries where sex work is still considered illegal. Furthermore, new forms of communication have increasingly placed erotic services outside traditional RLDs. “Widespread dispersal is thus possible and offers attractions to both prostitute and client, whose anonymity is not threatened by a visit to the notorious red-light area” (Ashworth, White & Winchester 1988, p. 206). These districts, however, mainly cater to immediate residential demographics, creating multifunctional spaces in coexistence with other activities, often resulting in severe struggles over land use due to moral rejection.

1.7 Social Dimensions of Sex Work

It becomes clear that the landscape of sex work covers everything between high-class and poverty struck offerings. Whatever their nature, RLDs have turned into a common urban feature or “a necessary moral equalizer” (Aalbers & Sabat 2012, p. 112) of urban spaces, assembling activities, normally not tolerated within society and turning them into “a significant urban activity that relates to other economic and social functions of the city [and contributes] […] to the cognitive image of a city held by both residents and non-residents, even those who have never frequented them” (Ashworth, White & Winchester 1988, p. 201). Their ability of “offering a window into the unconscious of the city” (Hubbard 1998, p. 61), has helped to (re)define moral standards, by externalizing immoral actions spatially and socially, constructing myths around the pure Western women and the immigrant sex worker, all while reaffirming “male bourgeois values” (Hubbard & Sanders 2003, p. 75). Placed in social twilight zones, sex workers are often subject to constructions around femininity, racialization and exoticization, exposing structural inequalities around gender and overarching hegemonic male fantasies. Whereas certain myths around sex workers, describing them as unhygienic, socially disconnected, diseased and submissive sex objects as well as outlets for the natural male excess remain, in reality sex workers generally don not comply with this socially constructed “spoiled identity” (ibid., p. 79).

Contrary to popular perception and portrayal, sex work cannot be equalized with poverty and exploitation, since only a minority of sex workers is actively forced into involuntary prostitution or subject to human trafficking. The United Nations has defined human trafficking as

"[…] the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs” (UNHR 2000).

Whereas “Scholars routinely observe that sex work and sex trafficking are empirically distinct phenomena” (Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015, p. 281), the popular discourse around these essentially de-coupled phenomena, paints them as supposedly interrelated, neatly aligning with mainstream nationalistic politics. Therefore, “the violation of the body of the trafficked sex worker has become emblematic of the violation of the state’s boundaries” (Hubbard, Matthews & Scoular 2008, p. 140) and is being used as a basis for increased securitization and states of exception on migratory matters. However, “contemporary law enforcement is actually enhancing opportunities for exploitation by perpetuating abandonment and exclusion” (ibid., p. 138).

Another important social function of sex work has been its impact on debates around feminism, gender equality, and self-determination. Whereas Abolitionist Feminism sees prostitution as a form of modern sexual slavery feeding into the omnipresent heteropatriarchy, the “’sex workers’ rights’ based approach” (Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015, p. 281) delineates sex work as a conscious and deliberate choice. The latter stands firmly against abolition and instead focuses on fighting other structural inequalities, such as police violence, employer accountability, secure payments or unionization, seeking overall social improvements. Furthermore, instead of playing into traditional gender roles, liberal feminists claim that prostitutes “are [in fact] subverting gendered expectations of appropriate behavior for women” (Hubbard 1998, p. 67), since “Within a rational and heterosexually-ordered city, street prostitution is seen as polluting because it challenges the notion that a woman can express her sexuality only in the confines of the home” (Hubbard & Sanders 2003, p. 82). Liberalization counters women’s inferiority to men by giving women the right and the power not only to actively shape their own lives but also to have an impact on the overall social development. Unfortunately, “While sex workers have incorporated new and innovative strategies for cultural activism, these perspectives are still often marginalized by mainstream, sensationalized portrayals of sex as an ‘iconic unequivocal, and perpetual human rights violation’” (Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015, p. 283). This is likely due to very unequal power

balances, since prostitution poses the capacity of becoming “a threat to the stability of a patriarchal society in which domesticised, vanilla hetero-sex is constructed as the norm […][and] the sight of women taking a more active sexual role is one that provokes considerable male anxiety” (Hubbard 1998, pp. 66-67).

Overall, it becomes clear that, while heavily understudied, sex work in fact is not a mere side issue, but lays “at the nexus of global capital, mobility, and the nation state” (Musto, Jackson & Shih 2015, p. 282), giving insights into social, criminological, spatial as well as political matters, while exposing processes of gentrification, speculation and displacement. The very famous vice district St. Pauli in Hamburg, entailing the sex and entertainment mile

Reeperbahn, in this context has been heavily understudied; a gap which this study will try to

bridge. After laying out the methodology of this study, part three will start off by giving a brief overview of the development of Hamburg and its marketing strategy. Subsequently, the district of St. Pauli and its residing red-light activities will be presented, before moving on to the last part where recent trends and developments at the Reeperbahn in light of increasing economic and marketing pressures are introduced. Some concluding thoughts and ideas will finalize this work up.

2. Research Methods

“Research design is ‘the entire process of research from conceptualizing a problem to writing research questions, and on to data collection, analysis, interpretation, and report writing’”

(Wilson 2016a, p. 39).

This thesis started out by looking at the Hamburg-Brand-Reeperbahn-Dialectic, exploring the effects local marketing efforts have had on the world-famous Reeperbahn and specifically its sex work industry. Since “It is a necessary and worthwhile endeavor to continually refine and reframe a question until it captures precisely the uncertainty you wish to resolve” (Wilson 2016e, p. 175), the angle of this thesis shifted slightly once the actual research had begun. Taking an inductive approach, the primary exploration of the Reeperbahn and its surroundings led to new discoveries, unfamiliar stakeholders and different perspectives, extending the focus onto the Hamburg-St.-Pauli-Brand-Dialectic.

Moving away from the traditional dichotomy of quantitative versus qualitative methods, mixed methods approaches have increasingly gained ground within research. “Mixed methods research is a systematic integration of quantitative and qualitative methods in a single study for purposes of obtaining a fuller picture and deeper understanding of a phenomenon” (Wilson 2016d, p. 57). It includes qualitative approaches, exploring the reasoning behind phenomena, eventually leading to the formulation of theoretical concepts as

well as quantitative measures, including mathematical and statistical tools. „Qualitative research is generally used as a broad umbrella term for a range of research methodologies, with differing epistemological assumptions” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 378), including the Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin 1996), Case Studies as the “science of the singular” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 379), Narrative Research, based on detailed stories or life experiences, or Phenomenology, as the non-bias exploration and universality of unique experiences (see Figure 1). However, due to arguments over the objectivity and

Figure 1: The scope of Qualitative Research (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 382)

therefore accuracy, dependability and replicability of findings, qualitative research does acknowledge that it is far from unflawed and in need of control measures such as triangulation, transfer onto other contexts and simple disclosure of limitations. Overall, qualitative studies might not be completely transferable or generalizable, nevertheless, they can give insights into sociological processes and uncover underlying structural mechanisms.

Looking into structural and sociological matters were key aspects of this work, placing this research in the midst of qualitative investigation. In order to gain an overview on central concepts such as prostitution, city branding or Neoliberalism, as well as some case specific historical and socio-spatial facts, a documentary analysis was undertaken as a first step. This was based on written sources, amongst others several academic journal articles, marketing reports, an array of Hamburg city guides as well as online newspaper articles, documentaries, web pages and blogs. Since “Fundamental to analysis of documents is identifying the context of the document, establishing who wrote it and for what purpose” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 381), sources were selected carefully, and their context taken into account. With this strong background of concepts and ideas in mind, subsequently an ethnographic research approach was pursued, entailing next to the document review, observations, interviews as well as mappings.

2.1 Ethnographic Research

The roots of Ethnography lie in the establishment of Comparative Cultural Anthropology in the early 20th century, aiming at analyzing cultural patterns. At the core of this approach therefore lie participant observations, a method that “[…] centers a long-term intimate engagement with a group of people that were once strangers to us in order to know and experience the world through their perspectives and actions in as holistic way as possible” (Shah 2017, p. 51).

2.1.1 (Participant) Observations

Ideally, researchers conducting ethnographic research, immerse themselves into a foreign context for at least a year, preferably 18 months or more, in order to uncover patterns of social interactions. Key is to conduct observations in a context which is foreign enough to recognize processes which self-reflexivity would not be able to uncover, but which are not too abstract to comprehend. Observations can be planned or informal, can be controlled or naturalistic, can happen at a distance or participative (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012). “Participant observation means that you try to experience the life of your informants to the extent possible;

it doesn’t mean that you try to melt into the background and become a fully accepted member of a culture other than your own” (Bernard 2013, p. 346). Balancing precisely this trade-off between engagement and objectivity posts probably the biggest challenge within ethnography, where researchers need to detach from their reality without losing themselves. Therefore, despite ethnography’s potential of creating new knowledge, uncovering structures that were once invisible and neglected, by “[…] taking seriously all those people and their histories that would be easily and willingly ignored by others” (Shah 2017, p. 56), findings can never be seen as purely objective, since their basis remains the researcher’s subjectivity. Furthermore, “While observation enables the researcher to see (and hear) exactly how individuals act and interact in a given situation, the presence of the researcher may influence behaviour” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 381), adding yet another layer of distortion. However, participant observation can be a “revolutionary praxis because it forces us to question our theoretical presuppositions about the world, produce knowledge that is new, was confined to the margins, or was silenced [becoming] […] a profoundly political act, one that can enable us to challenge hegemonic conceptions of the world, challenge authority, and better act in the world” (Shah 2017, p. 45).

A complete immersion into the field would have been optimal for this study, creating more interaction with sex workers and making experiences more reliable and detailed. However, due to personal boundaries and time as well as space limitations, the ethnographic character of this study had to be limited to punctual observations. Nonetheless, attentively walking through the district not only gave away tacit experiences, shaped by weather conditions, entertainment establishments as well as crowds of people, but led to the discovery of certain unknown phenomena. Throughout this research, a total of six observations were undertaken at the Reeperbahn, both during the week and on weekends at different times of the day (see Annex 5). They all covered a time span from around 45-60 minutes and were undertaken while walking through the district, trying to blend in with the general public. Four observations took place during night-time and only two during the day, since the focus of this research laid on the district’s night-time value and (restricted) red-light-related activities. Spatially, observations were focused on the Reeperbahn and its surrounding areas – it being the main vein of the local socio-spatial micro-cosmos. The first observation was explorative, strolling around the Reeperbahn and its side streets. Since it showed which areas were more fruitful and interesting, it led to the establishment of a more or less set route for the coming observations (see Figure 21 on page 50). These dynamic observations were recorded via

jottings and multiple pictures. Blending into the crowd was a constant balancing act, causing for multiple confrontations and even verbal aggressions. Whereas people generally do not enjoy being observed, a working environment as sensitive as a RLD increased the necessity for respecting everyone’s privacy – something easier said than done.

2.1.2 Recordings

Whereas observations might be the backbone of ethnographic studies, they often go hand in hand with recording methods such as field notes, audio- or visual tapings or mappings. According to Bernard, there are four types of field notes: Jottings, a diary, a log and proper field notes (Bernard 2013). Whereas a diary and a log fulfill a logistical and methodological purpose, creating space for personal experiences and feelings, as well as describing the layout and agenda of conducted observations, jottings and proper notes inform the actual research content-wise. Jottings are quick notes taken in the field, serving as triggers in order to bring back memories of incidences or details otherwise forgotten, which will later translate into well-formulated Proper Field Notes. Helpful in expanding one’s memory can be other types of recordings, such as audio or video clips as well as pictures. Another complementary tool can be different types of mappings, such as mental, emotional or concrete sketching, revealing personal experiences and different uses of space (Scheiner 2000).

Within this research, notes throughout the observations were initially written down as jottings or scratch notes and subsequently turned into proper descriptive field notes. Even though the sensitive nature of the field made it hard to take long breaks and write down distinctive details in the field, a prompt elaboration and certain triggers made it rather easy to reconstruct specific situations or settings. Furthermore, a variety of pictures was taken, helping the reconstruction process and serving as a visual add-on throughout this thesis (see Annex 6).

2.1.3 Interviews

Another valuable element of ethnographic research in order to extend or complement the further understanding of individual or collective experiences is interviewing is interviewing. It can take the shape of structured, semi-structured or unstructured interviews according to their degree of preparation and flexibility. “The conduct of semi-structured interviews involves a few pre-determined areas of interest with possible prompts to help guide the conversation” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 380) and offers openings for new discoveries while remaining within the frame of the research area. They can vary from one-person interviews to focus groups, questioning a variety of stakeholders simultaneously. Individual and foremost

face to face interviews can give more in-depth information and offer insights into personal traits, whereas group

interviews uncover social dynamics. Another important step is the choice of (a) suitable interview partner(s). Their sampling can be non-probable, not assuring the coverage of any specific elements and therefore not generalizable (see Figure 2). This includes Accidental or Convenience, Quota, Purposive, Snowball or Self-Selection Sampling (Wilson 2016c, pp. 45-46), or is based upon probability and accurate representation of proportions, via Simple Random, Systematic, Stratified Random or Clustered Random Sampling (ibid.). Records of interviews can happen either via manual notes or via audio (-visual) recordings, which then need to be developed or transcribed. Subsequently, an analysis needs to be conducted to identify relevant information or citations.

Once the research design for this thesis was set up, an initial stakeholder analysis identified potentially important interview partners, including prostitute’s organizations, the local police station as well as city planning entities. These were hence based on theoretical sampling. Additionally, multiple contacted stakeholders provided further contact points, expanding my net of interview partners in a snowballing manner. This was especially true for the communication with city planning instances, which unfortunately could not spare time even for a short interview, constantly referring me to other colleagues. Apart from that, it was rather easy to get in touch with other stakeholders and set up prompt interviews. Throughout the course of this research six interviews were conducted (see Table 1), generating a total of approximately four hours of interviews. All but one interview were semi-structured, loosely based upon a previously elaborated set of questions, fed mainly by the literature review and later by previous interviews (see Annex 2). One interview, however, took place in the form of a recording, following the clear structure of the provided questions and later sent via e-mail.

Interviews

Person Occupation Contacted Replied Interview

Anonymous Interview Partner

Social Worker at a counseling center for sex workers

31.01.2019 11.02.2019 13.02.2019 at the office

Julia Staron

Business Improvement District Reeperbahn+ Manager

16.02.2019 17.02.2019 19.02.2019 at her venue Kukuun Stefan

Nöthen

Head of Strategy & Brand Management at the Hamburg Marketing Office

31.01.2019 16.02.2019 25.02.2019 at his office

Margot Pfeiffer

Police Commissioner at the Davidwache 07.02.2019 11.02.2019 25.02.2019 at the Davidwache precinct Steffen Jörg

Social Worker at GWA St. Pauli within the field of neighbourhood politics 05.03.2019 05.03.2019 19.03.2019 at localities of the GWA Josefa Nereus

Sex worker, press spokeswoman and activist

18.03.2019 19.03.2019 27.03.2019 in the form of audio tapes

Following the iterative nature of this research, interviews were fed by other methods such as document analysis and observations and vice versa. For an easier and more complete analysis, all interviews were loosely transcribed, refraining from transcriptional language or translation. In order to make transcriptions easier, they were conducted within one week of the interview, taking advantage of the freshness of the memory. Subsequently, all interviews were analyzed.

2.2 Content Analysis

Content analysis goes back to the study of mass communication which emerged during the 1950s and is based upon classification and coding, either along qualitative or quantitative guidelines. Coding entails “allocating labels to events, actions and approaches” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 378). Content can then be processes in a qualitative or relational manner, translating codes into broader concepts and comparing them across different data sets or considering them as valid numbers and counting within a conceptual analysis. “Quantitative analysis [then] starts with a hypothesis and a predetermined coding scheme that is designed to test the hypothesis” (Wilson 2016b, p. 41). This coding scheme can entail for

example a codebook, delimiting set standards, making counting and evaluation numerical. A qualitative approach filters concepts in an iterative process, feeding the codebook throughout the process, looking for new links, entry points and relations between the codes.

While analyzing the transcripts, a qualitative approach was pursued, identifying common patterns, wordings or concepts through all or several interviews. Cues were especially aspects which were related to the branding of the Reeperbahn and the district St. Pauli, as well as its revaluation and gentrification process. These ideas and codes were then supported by key quotes, which were filtered out of the individual documents, merged into summaries and later weaved into the overall argument. A different form of coding was conducted while going through the guidebooks. Here, a mix of quantitative and qualitative coding was pursued, were initial concepts were actively looked for, nevertheless expanding the code book throughout the process of analysis. The amount of naming for each of the concepts was later fed into an online word cloud tool, making visual representations possible. However, the necessity of a clearly laid out quantitative research design became apparent throughout the city guide analysis, since the iterative approach of the design, caused confusion and potential inaccuracy. Seeing that this was the first time such coding was used, there has been a clear learning curve and realizations which will be taken into future research projects.

2.3 Limitations

This study tried to minimize the distance between researcher and topic of investigation. Instead of writing about the district and its inhabitants, representative stakeholders were pursued in order to give voice to underrepresented individuals such as sex workers, migrants or less culturally rich inhabitants. Unfortunately, as mentioned before, one of the big limitations was the sensitive nature of the sex industry, making it rather difficult to reach out to individuals directly involved within the milieu. As a study concerning the perspective of homeless people at the Reeperbahn (Scholtz & Strüver 2017) showed, prior contacts are a valuable asset when reaching out to less prominent individuals, something that was lacking for this study. The afore-mentioned approach was based on spatialized narrations through mobile interviews, where interviewer and interviewee were walking through the neighborhood, casually talking about perceptions, experiences etc. This was further complemented and visualized by mental mappings, spatializing experiences on paper. Ideally, such an approach could have been done with residents or sex workers of St. Pauli throughout this study. However, a lack of the necessary social connections as well as time limitations impeded the creation of strong connections to the district. However, the insights provided by

interview partner Josefa Nereus, can stand somewhat representative for at least a certain segment of sex workers and made this work much more reliable and rooted. Furthermore, moving marginalized individuals and topics more into the public realm has been the major reasoning behind this study something considered a success, which will become apparent within the following results.

3. Hamburg: From a social to an entrepreneurial city

“Hamburg is one of the poorest cities in the Global North and at the same time one of the richest”1

(Birke 2010, p. 185) The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg is

located in the Northwest of Germany (see Figure 3) and with its 1.8 million inhabitants it is the second-largest German city after Berlin. “Hamburg is Germany’s most economically viable and dynamic city” (HMG 2014, p. 44)2, mainly due to its geographic position near the Elbe River, and its connection to the North Sea, making the city Europe’s third-largest port after Rotterdam and Antwerp and amongst the top 20 container ports worldwide (Hafen Hamburg Marketing e.V. 2018). Hamburg is one of Europe’s most important logistics locations, but is also known for its aeronautic engineering, creative industry and media scene (HMG 2014). Furthermore, due to its

historical, cultural and architectural particularities, tourism in Hamburg has experienced tremendous growth over the years. A short historical overview will explain how Hamburg became one of the most dynamic and powerful regions in Europe, known for its liberal and alternative scenes, something actively instrumentalized by the Hamburg Brand in order to attract tourists, investors and capital, simultaneously causing social and spatial fragmentation.

1

All German quotes have personally been translated into English and the originals referenced in a foot note. Original quote: “Hamburg ist eine der ärmsten Städte im globalen Norden, aber zugleich auch eine der ganz reichen”.

2

Original Quote: “Hamburg ist Deutschlands Stadt mit der höchsten Wirtschaftskraft und den besten ökonomischen Zukunftsaussichten”.

Figure 3: Hamburg on the map of Germany –

3.1 Development of Hamburg

Throughout its 1000 years of existence, the City of Hamburg, like many others, faced many successes and challenges. The modern city of Hamburg is located where a village called Hammaburg near the River Bille used to be, a prominent point when crossing the Alster Lake from North to South. From its very origin, the city therefore turned into a dynamic trading point. This was consolidated in the official trading license issued in the 12th century and the joining of the League of Hanseatic Cities, a trading alliance founded in the city of Lübeck in the 13th century. The latter gave Hamburg a crucial economic position in the world and is still anchored in its name – Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (Schafer 2017).

It was not until the end of the 18th century that Hamburg started its first trading with sugar, coffee and caoutchouc towards the Americas, becoming an established “merchant republic” (Lindemann & Lau 2018, p. 325). Furthermore, throughout the mid-19th century Hamburg became known as the “Tor zur Welt” – the Gate to the World (Amenda 2006), since next to Bremerhaven, it became the most important European harbor for migration towards the New World. This also marked the birthmark of the so-called “Auswandererhallen” (Brinkmann 2016, p. 240) at the beginning of the 20th century, a small city on the Veddel Island created by famous ship owner Albert Ballin, making space for thousands of people waiting for their ship connections. Over time the so-called BallinStadt became one of the most important European counterpoints to Ellis Island, the migration gate in New York and simultaneously strengthened Hamburg’s maritime position (Schafer 2017). Other significant changes throughout the 19th and 20th century was the installation of an open tide harbor, the shift from sailing to steamboats, the installation of a tax-free zone in 1881 and finally the construction of the warehouse district Speicherstadt, inaugurated in 1888, relocating large parts of the population into so-called Gängeviertel (ibid.). Throughout the 20th century the harbor was constantly modernized and in 1913 ascended to the third-biggest harbor in the world after London and New York. Unfortunately, Hamburg’s ongoing economic success was strongly inhibited by both World Wars, destroying around 80% of the harbor and 50 % of the

Speicherstadt and causing economic decline. A phase of reconstruction towards the end of the

century leading to expansion and remodeling of the harbor towards a large container port and put Hamburg back on the map, by (re)turning the city into “[…] the main hub for traffic from and to the Baltic Sea and a gateway for cargo to Central Europe” (OECD 2015 p. 232).

From Hamburg’s very origin, the city’s harbor did not just shape its political and economic development, granting the city independence, wealth and excellent connectivity within the region and the world, but also shaped its demographics, social patterns and culture. An important transition happened when de-industrialization stroke from the 1980s onwards. During this time, especially German port cities such as Hamburg and

Bremen were led into economic crisis due to the shipbuilding decline, causing for unemployment rates surpassing the national average (Birke 2014). Hamburg’s political and economic response was a shift towards the service sector as well as economizing and improving the urban layout. “Already by 1983 the city became an avant-garde laboratory of neoliberal urban politics when former mayor Klaus von Dohnanyi of the Social Democratic Party forsook the redistributive principles of the soziale Stadt for the competitive principles of the unternehmerische Stadt, the ‘entrepreneurial city’” (Ufer 2015, p. 66). A shift towards agglomeration of technologies, manufacturing, finance and services is characteristic for post-industrial cities and clearly left its imprint on Hamburg. It is therefore no surprise that today 80 % of the city’s yearly gross value added derives from the financial sector (including insurances as well as property market), the trading sector (including mobility, logistics and IT) as well as other service sectors (including health, education etc.) (Handelskammer Hamburg 2018b), showing clearly how the Hanseatic city has turned into a service-oriented economy, focused on human capital, innovation and growth, catering to multiple post-industrial profiles, namely logistics, finances, business but also tourism as well as culture (Figure 4).

The transition to a service-led entrepreneurial city has brought on common trends such as urban renewal and gentrification, led by public private partnership and neoliberal politics. The

HafenCity, including the Elbphilharmonie, does not only function as the city’s new flagship

project but further facilitates city branding strategies within an era of inter-city competition Figure 4: Post-industrial economic city profiles (Anttiroiko 2015, p.

(Balke et. al 2017). Therefore, even though “The port has historically been the city’s economic growth engine and a central part of its identity as a city of trade” (Grossmann 2008, p. 2062), strategic global location factors such as urban attractiveness and a higher quality of life have become increasingly important, where “Both new economic sectors and inner-city waterfront space are crucial assets for the success of the city in the post-industrial society” (ibid., p. 2071). This so-called Glocalization (Robertson 1995), a combination of local patriotism and self-perception within the increasing pressures of globalization, has clearly translated into Hamburg’s city marketing strategy – The Hamburg Brand.

3.2 Hamburg – an entrepreneurial city

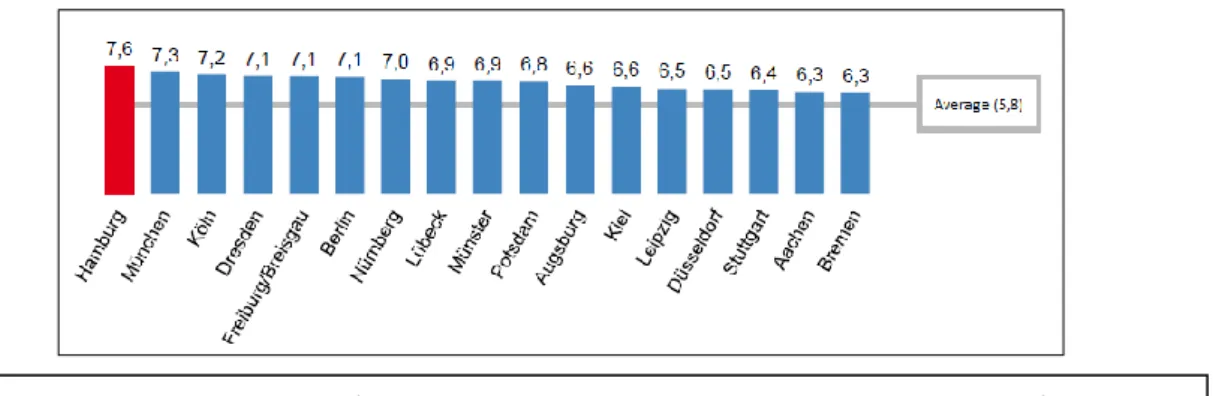

“[...] Hamburg is now Germany’s strongest city brand” (Kautsch 2017, p. 2)

A clear movement towards place marketing and city branding started in the 1980s in Germany and by 2009 reached around 70 % of all German cities. Place branding became very popular since it is said that “[…]high attractiveness and a strong appeal ensure the future of towns and cities of all sizes; secure the next generation of skilled workers that are so critical to companies; attract investors and businesses; create popularity among tourists, and, ultimately, increase the number of local residents” (Kautsch 2017, p. 1). Aiming for amenities, such as urbanity and diversity, nature and recreation, high job chances and cost-efficiency under this premise, shed a positive light on a city’s image and improved the chances of innovation and growth (Zenker 2009, p. 26).

In this context already from the 1980s onwards, Hamburg became one of the first German states to embrace a proactive growth-oriented policy, under the label “‘Unternehmen

Hamburg’” (Novy & Colomb 2012). By promoting the pre-existing concentrations of artists,

cultural industries and events, Hamburg tried to target four groups specifically: visitors, residents and workers, businesses and industries and the export market (Zenker 2009, p. 24). Almost four decades later, this enterprise management has turned Hamburg into a global city and a logistic hub, however, not free from socio-spatial repercussions. “Hamburg has become one of Germany’s prime sites for real estate speculation, the deregulation of the housing market, and gentrification” (Ufer 2015, p. 66), with rent controlled apartments having dropped from 23 % in 1994 to 11 % in 2011 and vacant office buildings reaching up to one million square meters (ibid.). Furthermore, under the label Over-Tourism, some areas of the

city have claimed being unable to withstand the increasing socio-economic pressures caused through the active marketing of the city.

3.3 City Branding

The strategy of branding derives from the private economy sector and traditionally refers to the presentation of a specific product, making it stand out against its competition by fostering the same positive associations over a long period of time (Pirck 2005). Traditional marketing therefore aims at reducing genericness and enables concrete and clear ways of communication to increase word of mouth propaganda. Whereas classical product branding has enjoyed a long-standing tradition, city branding is fairly new and very particular, since it does not promote a unitary and static commodity, but rather stands for an ever-changing social construct made up by buildings, people and practices (Lefebvre 1991). In other words, “a city is not a deodorant. The important aspect is that we will never be able to compare a city with a commercial product. But we can apply some techniques where suitable” (Interview Nöthen 2019)3. Simplifying this complex reality into something comprehensible and transmittable, while remaining authentic and inclusive, presents an unavoidable conflict. The self-image of the city therefore becomes increasingly important, because citizens are not only targets but become brand makers too (see Figure 5).

3

Original quote: “Eine Stadt ist kein Deo […]. Das Wichtige ist aber, das wir nie die Stadt mit einem Produkt vergleichen werden. Das sind eher Techniken, die wir aus dem Bereich anwenden, aber halt auch nur da wo es funktioniert“.