Killing Women

A Critical Study of Gender Equality

in the U.S. Criminal Justice System Regarding

the Most Severe Form of Punishment

Sally Erisman Supervisor: Carlo Pinnetti Malmö University, Department of Global Political Studies Human Rights III Spring Semester 2012

About 1 in 10 murders in the United States are committed by a woman. Meanwhile, only about 1 in 50 death row inmates are women. This initially suggests that women are favored in capital cases. There have been two predominant viewpoints attempting to explain the statistical imbalance: on the one hand there is Rapaport’s theory of gender-related crime in relation to existing legal directives on what warrants a capital sentence; and on the other hand is Streib’s theory of chivalry, that women are receiving lenient treatment in capital cases because they are women. This study has examined both theories, and tested their validity, by analyzing statistics and other material supporting or opposing their respective claims. The entire study has been carried out through a feminist theoretical perspective, questioning how “gender” plays an active part in capital cases, and relating committed crime to the victim, subsequently finding that even though Rapaport and Streib advance different theories, neither theory supports a claim that favoritism is incorrect.

Keywords: capital punishment, death penalty, equality, United States, women Word count: 15,479

1

Contents

Abstract I

1. Introduction 2

1.1 Purpose of the study 4 1.2 Research question 4 1.3 Method 5

1.3.1 Statistical analysis 5 1.3.2 Legal case study 7 1.4 Theory 8

1.4.1 The basic elements of feminist theory 9 1.4.2 Differences within the theory 10

1.4.3 This study’s theoretical selection 11 1.5 Delimitations 12

2. Material 13

2.1 Historical review 13 2.2 Crime-based theory 14

2.2.1 Executive clemency 16

2.2.2 Gender-related capital crime statistics 18 2.3 Chivalry theory 24

2.3.1 Origins of chivalry concepts 24

2.3.2 Application of chivalry in criminal justice 25 2.3.3 Evil Woman Theory 26

2.4 Dominance and power structure 27

2.4.1 Different voice and dominance theory 27 2.4.2 Rescuing subordination 29

3. Analysis 31

3.1 The inequality rationale 32 3.1.1 ”Male” crimes 32

3.1.2 Sentencing and execution 33 3.1.3 The ranking of severity 34

3.2 The fallacious appreciation of women 37 3.2.1 The practice of chivalry 38

3.2.2 The downside of chivalry 39 3.3 Chivalry vs. consideration 40 3.4 Conclusion 42

3.4.1 Future research 43

4. References 44

Appendix A – Federal laws providing for the death penalty 48 Appendix B – Death sentences imposed on females 49

2

1

Introduction

In a statistical review by the Death Penalty Information Center covering the years 1973-2011, it was found that about 1 in 10 murders in the United States are committed by a woman. Meanwhile, if one were to look at all death sentences handed down during the same time period, women have accounted for about 1 in 50. There is no arguing whether or not there is a statistical imbalance between the sexes; the disagreement lies in determining the reasons for the imbalance. United States law does not actively encourage selective treatment of either sex, nor are jurors supposed to treat men and women differently in cases involving a possible capital sentence, suggesting that the origins of the disproportion may be found elsewhere. As a result, a number of theories have been constructed to explain these figures, and answer the questions of why women are sentenced to death to a substantially less degree than men.

There have been two predominant viewpoints attempting to solve this question. One approach focuses on the nature of the crimes themselves, by looking at possible surrounding factors, primarily what crimes warrant a death sentence, and whether or not the corresponding gender distinction can be found in those figures. This theory has attempted to uncover gender-related patterns of criminal behavior, to determine if there are certain crimes, in this case capital crimes, which are especially male or female. The content of this research has included an overview of the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim, the level of heinousness of the murder, and most importantly, the relationship between male and female, and domestic and public. The general idea is that a gender-related imbalance of death sentences given to men and women can be explained by gender-related crime, in relation to the outlines of the law of what warrants a capital sentence.

The other major approach has a different focus from the nature of the crime itself, rather seeking to prove that women are being held to a different standard than men in a criminal justice setting, more or less regardless of the nature of the crime. Most supporters of this theory are concerned with what they believe to be greater leniency offered to women than to their male counterparts. They find that women are granted

3 lighter sentences because they are women, and that their crimes are accordingly often perceived as less severe.

Such a claim has inevitably generated a counter-reaction, or alternative branch, to the theory, which finds that women are being judged and subsequently punished differently, especially regarding possible capital crimes, but these women need to meet a certain criterion related to perceptions of gender in order to receive special, i.e. positive, treatment. Otherwise, they might – contrary to receiving leniency – be judged more harshly.

Criminal justice has traditionally been very much of a man’s world, with little effort to take a woman’s perspective into account. While both approaches to explain the statistical inequality are in constant debate, both theories have been used with varying frequency to explain the outcome as an alleged bias in favor of women. In the overall pursuit of gender equality as the main objective, this concern of gender-related partiality in cases of capital punishment is in great need of further exploration. As equality is of extreme importance to the field of Human Rights, an alleged bias needs to be proven or discredited, which is the purpose of the study1.

The introductory chapter will continue with section 1.1, containing an explanation and purpose of the study – why it is needed, and how it intends to contribute to this field – followed by the research question in section 1.2. Section 1.3 will address the decision to base a lot of the research on statistical analysis, and the study of legal cases, as well as provide some explanation for the selection of other theoretical material. After that, section 1.4 will present the basic principles of feminism, a theory with great focus on discussions of gender-related inequality, which will be further elaborated and discussed in the final analysis. The last part of the introductory chapter, section 1.5, will briefly make known the necessary restrictions made to the study.

Following the introduction, the material will be presented. Chapter 2, section 2.1 and will contain some brief historical information on especially noteworthy capital cases,

1

Note: Most papers written on capital punishment are about the pros and cons of the death penalty itself. I feel it necessary for me to disclose that I am very much against the death penalty, and believe it to be an inhuman punishment – in many ways even a glorified form of torture – and a direct violation of human rights. While this study might reflect this opinion of mine, I will refrain from discussing the legitimacy of the

punishment itself, so as to not have it become another abolition paper. Therefore, to all my fellow death penalty opponents, forgive me if I use words like eligible or warranted when referring to capital punishment.

4 followed by 2.2, which presents the crime-based theory about the capital sentencing of women is related to the crimes themselves; the existing discretionary guidelines for sentencing; and statistics on the capital sentencing in the current death penalty era. The following section, 2.3, will present the opposing theory, stating that women are treated differently in capital cases because of their gender, not because of the nature of the crime. The last part of the material chapter, section 2.4, will provide some alternative feminist views on women and dynamics of power in a criminal justice setting. The final chapter, 3, will contain the analysis of the material, where the presented material will be discussed through a feminist theoretical perspective, followed by a conclusion, and finally a recommendation for future research.

1.1 Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study is to critically investigate existing opposing theories as to why there is such a large statistical gap between men and women on death row in the United States. By reviewing the empirical and theoretical material behind their conclusions, this study is an attempt to uncover the errors or inadequacies of their reasoning, as well as provide an alternative interpretation.

There is a wide range of existing work about racial discrimination related to capital punishment, but in comparison, gender inequality seems to be mentioned to a significantly smaller degree; sexism even less. This study, however, will place principles of gender equality and selective treatment in capital cases in direct focus, as gender and women have been widely overlooked in this debate despite the displayed statistical differences between how men and women are treated and sentenced in the courts. The discussion as to why this imbalance has occurred has largely been constructed through a preconceived view that women are benefitting disproportionally to their male peers from this imbalance. It is this notion that this study intends to explore.

1.2 Research question

5

1.3 Method

The study is conducted through a combination of legal method and statistical analysis. The combination of the two methods has allowed a both general and individually applicable conclusion, by presenting detailed information about specific cases, as well as a broad understanding of the greater scope of the issue.

1.3.1

Statistical analysis

Statistics can be used to create a base for a study, i.e. generate a platform from which one can further investigate and explore. By reviewing the statistical raw data of one or just a few aspects, one can expose a greater, more general problem. Statistics can enable the researcher to draw generalizing conclusions about figures taken from a representative group of the entire population, instead of actually including each individual separately in the study. It serves as an excellent component in any research that is trying to reach a scientific conclusion in a productive way (Delorme 2006:1).

Statistics can also be very helpful in generating potential research questions, and help visualize a problem, especially a comparative one. To this study, where inequality and comparative analysis of men and women are the main focus, the statistical records have been crucial, as they have both provided substantial and vital information, as well as generated a discussion about possible interpretations of their content. In short, they have in a clear way demonstrated existing imbalances, which have been further explored with complementing material.

Statistical reliability can vary greatly due to certain factors, e.g. the number of participants in proportion to the entire group of interest to the study, or the process of how the participants in the study have been selected. Many feel that a random selection would be the most fair and unbiased, as it would not subjectively reflect the researcher’s purpose of the study. However, a random selection could at the same time be misleading, e.g. by excluding some sub-categories of the population, thus yielding results that fail to reflect the entire population. With that said, the validity of any statistical analysis increases by increasing the percentage of the sampling group to represent the entire population or targeted area of the study (CSUN 2007; Delorme 2006:1,7). In the case of

6

this particular study, the statistics used are not subject to this concern, as there was a non-discriminatory selection of participants. They have been made up by information in the modern era of capital punishment, during which time we can assume that detailed and correct documentation has taken place. Therefore, no selection of participants has been made, but rather all subjects involved have been included.

The statistics used in this study have been extracted from previous studies on gender and the death penalty, as well as from, the United States Department of Justice (USDOJ) and the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) database. The DPIC is a widely recognized non-profit organization, which is often cited in accredited media such as the New York Times, BBC, and Reuters. The organization has been acknowledged by both pro and con death penalty associations as a highly reliable source of objective information on capital cases (Stewart 2008; DPIC1).

Statistical data cannot account for the reasons behind their content; rather, such data disregards all environmental surroundings. Statistics can thus come across as very shallow and narrow, and have been criticized, especially by constructivists, as “short-sighted” and even dangerous, as it excludes all contexts (Moses 2007:246). In accordance with this critique, this study finds that statistical analysis is an insufficient method on its own, and has required other material, largely found in previous research. Such material has been used to create a foundation for statistical interpretation, analytical discussion and the final conclusion. The previous studies used have primarily been the work of Elizabeth Rapaport and Victor L. Streib. Rapaport is an accredited author and scholar, with a Ph. D. in philosophy, and a J.D. in law and public policy. Her work is highly respected, and often quoted in other publications on the topics of feminism and law (USFCA 1999). Streib is a law professor, and former prosecutor and defense attorney, whose work has been referred to in several Supreme Court hearings (ONU 1999). Both authors are commonly referred to in studies about gender and criminal justice, but with very different views on equality and discrimination and the mechanisms that drive them. For the purpose of this study, these two authors have provided two opposite views of or approaches to the same problem, i.e. different interpretations of the same statistical data.

The figures discussed in this study can briefly be described as statistical differences between men and women sentenced to death; what crimes are most represented on death row, and the relationship between the male or female perpetrators and their correlating victims. These statistics were included in this study partly due to the fact that they formed the basis of the two opposing theories of Rapaport and Streib, and partly due to how they

7

help illustrate the errors of these theories. This study will show that the selection of statistical information affects the outcome of a study, as well as how the interpretation of statistics is largely influenced by the purpose of the study and subjectivity of the researcher.

1.3.2

Legal case study

Statistics only provide a very limited range of information, including neither the surrounding factors – e.g. historical aspects of the death penalty other than numbers – nor specific cases to examine more closely. Therefore, this study has in addition to statistical analysis, incorporated some elements of the legal method (Shelton 2006:322), in order to provide a more in-depth understanding of capital cases in the United States. This study has not conducted a single case study per se; rather, it has incorporated information from several capital cases which were selected for their relevance to this study, primarily capital cases of women, but also others which have in some way shown to have had a significant impact on courts’ perceptions of gender discrimination.

Unlike statistical material, reviewing a specific case can allow focus to be placed on the descriptive qualities rather than the bottom line. A case study is a qualitative method, in contrast to the quantitative statistical analysis, that does not focus on the general applicability of the subject, but rather asks the question “why” when a concern has already been established. A specific case can help display possible scenarios of a certain problem, generate problem questions and create an understanding of which areas require extra consideration. It can also provide a level of authenticity and applicability to both the researcher and the reader in the otherwise sometimes very abstract nature of scientific research (CSU 2012).

One of the cases which I will discuss is that of Karla Faye Tucker. Her case shows how the issue of gender cannot be ignored as playing an active part in a capital case. It depicts how a female predator, on capital trial, is not only discussed in terms of the crime she committed, but in terms of questioning her very womanhood. This opens up for further elaboration, for instance on our perceptions of what “feminine” actually is.

The critique against the case study method has perhaps more to do with comparing a case study to other methods of research when it in fact holds unique qualities. Its primary benefits are perhaps not reliability and validity, but rather depth and verifiability.

8 Like the possible implications of the statistical method, studying a specific case often draws criticism for being highly subjective – from the initial selection to the analysis of the results (CSU 2012). Consequently, not only the Tucker case, but all the capital cases that were included in this particular study were very intentionally selected based on the purpose of the study. However, they serve primarily as catalysts for further discussion rather than as empirical evidence. In social science, a case study is better off being included in the broader scope of the legal method, rather than attempting to have it suffice on its own.

Apart from the specific court cases, this study will include further exploration of the legal framework by looking at existing regulations and guidelines available for those who serve as judges and jurors in capital cases, and well as the very stipulation of what constitutes a capital crime. The application of legal sources and argumentation, and reviewing both theory and practice of the legal framework, will provide a broad understanding of the judicial process in capital cases – from sentencing to execution.

The legal method faces some critique as a research process due to the breadth of the method – that due to the vast quantity of information, it can result in a very shallow study (Gray 2010:86), which does nothing to provide the reader with anything directly applicable, or for that matter new and exciting. Moreover, the breadth of the scope might create some unclarity, e.g. in cases of overlapping laws (Shelton 2006:322). Because of this risk, this study has not considered the individual state laws in relation to federal law, rather generalizing the United States and the death penalty as a whole; as well as using specific court cases and statistical data for a more focused direction.

The limited qualities of statistical raw data and the explicit and descriptive qualities of examining specific legal cases, combined with a broader spectrum when reviewing within the scope of the judicial system, have collectively provided a general, yet focused discussion of the gender-related inequalities within the United States criminal justice system, with regards to the death penalty.

1.4 Theory

When considering matters of sexism, gender inequality and possible discriminations, the decision to conduct this study through a feminist theoretical

9 perspective seemed highly appropriate, as the theory questions socially, historically, and profoundly engrained ideas of qualities and behavior that are associated with a person’s sex. The decision for selecting this theoretical approach was also greatly influenced by the fact that the author of the one theories in question, Elizabeth Rapaport, is a feminist scholar; and the fact that the author of the other theory in question, Victor Streib, has faced much critique for ignoring aspects of gender. By selecting another theoretical approach, the outcome of this study would likely have been much different. To fully understand this selection of theoretical approach, this section will provide some brief history of the feminist theory, as well as describe the key elements of its take on reality.

1.4.1

The basic elements of feminist theory

The first International Women’s Conference was held in Paris in 1892. Before then, “feminism” was not part of the English language (or any other language for that matter) vocabulary, but now it came to mean “the struggle for equality between genders”. Today, “feminism” is sometimes used as the term to describe the political and social women’s right movement primarily in the United States and Europe, but for others it refers to the principle of an oppressed gender. There is, however, a clear distinction between the feminist movement in action, largely concerned with women’s rights; and feminist theory, which includes all inequalities and sexism – facing both women and men. It is important to recognize that “feminism” is therefore not limited to women’s rights. Ensuring or depriving women of the same rights as men in the legal or legislative sphere does not necessarily result in an equal society. Rather, societal structures, cultural practices, and our general consciousness regarding issues of oppression, equality and sexism are what really effect change, and that is what feminist theory is about (Chafetz 1997:97-98; SEP 2003).

While acknowledging the original and strictly biological definitions of male and female, feminist theory also focuses on masculine and feminine, i.e. both the biological and the behavioral aspects. The notion of gender varies within feminist theory, but an overall thought is to say that what we consider “feminine” and “masculine” personalities develop at an early age on an unconscious level to be further enforced in a social setting that evolves it into a personality and ego. These gendered personalities reflect the stereotypical behaviors to which the child is exposed, and certain qualities are then

10 perceived as male and female. In other words, if children at the earliest stages in life were to be exposed to an alternate, gender neutral, environment – one that does not enforce these gender personalities – they might become more resistant to future exposure to gender stereotyping. This stereotyping is an assumed collectiveness among the gender one belongs to – that one shares characteristics with all others within that group – characteristics that at the same time separate one gender from the other. According to feminism, such a distinction will inevitably be flawed, as it does not take into account other aspects within one’s gender that may overlap to the opposite gender – such as race, culture and class. Moreover, it is an unnecessary focus, as even if there were distinct qualities among the separate sexes, the importance is to recognize that one is not above the other (Baym 1995; SEP 2008).

1.4.2

Differences within the theory

While some feminist theorists would say that the main purpose of the feminist discourse would be to end the oppression of women, others apply a much broader scope to include ending all oppressions affecting women. This would include everything from race and religion to age and class. There are many reasons to believe that fighting other injustices than those against women specifically is in fact necessary to fulfill feminist goals. Some feminists consider this extensive view of oppression to be a struggle separate from feminism, even if they are co-dependent in their common goal to end all forms of domination and inequality. The broadness of the theory has left some scholars feeling that there is a need for new terms to divide certain aspects of feminism into smaller concepts. One example of this is the not yet broadly established “womanism”, referring to the subcategory of women of color (SEP 2003).

Some feminists focus more on sexism than anything else, and believe that this is the only place where men and women can truly come together in a mutual understanding and effort to overcome existing power dynamics. This focus allows the theory to move away from problems with defining the different concepts of feminism, and merely place all its focus on its main goal – equality. Oppression, the primary obstacle for equality, can be described as a social structure that limits one set of people: that enables one group by limiting the other, not in a single instance, but as a pattern, creating a profoundly understood societal structure. Oppression does not emerge overnight, but has great

11 historical bearing and is profoundly engrained, both with the oppressor and the oppressed. What separates sexist oppression from other oppression is that we can say that oppression – in many shapes and forms – harms women, but sexist oppression harms women because they are women. This element is why sexist oppression has a greater platform within the feminist discourse than other forms of oppression (SEP 2003).

Feminist theory has two elements: the normative quality, i.e. the moral claims of how women should have the same rights and that we’re all equal under the law; and the descriptive quality , which describes the situation like it is today, that women are currently oppressed to varying degrees worldwide for their gender and don’t experience the same benefits men do because of it. One could say that the descriptive component looks at the how and what, while the normative asks why. Feminist theorists often have disagreements regarding both components: either on what constitutes “equality”, “justice”, and “oppression”; or what the actual problems are out there today for women to face regarding these issues. Mainly, the disagreement can be found in determining the reasons behind the injustice, and how to rectify them. In mainstream society, one can assume that not everyone, not even all of those who would like to see more equality between the genders, would fully accept both the normative and the descriptive qualities. Someone might agree with the principles of equality, and justice for all, without reviewing themselves and the life they lead, where inequality can be found all around them, while others might want to involve themselves in a specific feminist concern, but not have any greater moral considerations about life and society overall. It is important to include both qualities in the discourse, if for no other reason than that applying normative qualities to the theory would probably merely attract the scholars, the philosophers, and be confined within existing social and political relations. But the descriptive quality of the theory is something that is very specific and to which more people can relate (SEP 2003).

1.4.3

This study’s theoretical selection

Existing notions of gender infiltrate every part of our lives. Consequently, feminist theory can be applied to any scholastic research, but most appropriately, one in social science. For the purpose of this study, the selection of feminist theory has enabled the

12 research to be conducted through normative critique and analysis, illustrating the severe outcomes of allowing these existing notions to color the judicial process in capital cases.

The decision to use Rapaport’s feminist approach was due to the descriptive qualities of her work, possibly influenced by her experience in criminal law; as well as the normative qualities of her work, possibly influenced by her philosophy background. Hers is, however, not the only theoretical approach in this study. Other feminist theories have also been briefly included, such as Carol Gilligan’s “Difference Theory”; the opposing “Dominance Theory” by Catharine MacKinnon; in addition to the more general feminist critique of criminal justice by feminist scholars such as Renée Heberle. Together, they have helped this study avoid excessive generalizations about probable feminist responses to the material at hand.

1.5 Delimitations

Statistics of manslaughter, compared to those about murder, have needed to be excluded from this particular study due to the applied restrictions on the length. These restrictions have also made it necessary to make some drastic cuts as to what to include in this work. Primarily, factors such as race and sexual orientation have had to be eliminated from the study. Racial bigotry, or prejudice regarding sexual orientation, may very likely have greatly influenced capital crime procedures – factors which have not been allowed consideration in this very limited study.

13

2

Material

This chapter will present information related to women, crime, and the death penalty. It will also include the two opposing theories on the gender-related, statistical imbalance of death row inmates, as well as feminist theoretical views related to criminal justice. This chapter starts with a brief historical summary, primarily to illustrate the origins of the legal guidelines for determining and evaluating capital cases, followed by the content of Rapaport’s theory and statistical data. The chapter then moves on to the opposing theory by Streib. The last part of the chapter provides some additional theoretical aspects of equality, followed by the analysis.

2.1 Historical review

In 1972, the United States Supreme Court had received concerns about possible violations of the 8thAmendment of the United States Constitution (hereinafter referred to

as the Constitution), and they decided to review four capital cases. The cases were 2 rape cases, 1 murder case, and 1 accidental killing. The accidental killing was the case of Furman vs. Georgia (Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 1972), where Furman, who suffered from psychotic episodes, fatally shot someone when he accidently fired a gun as he tripped over a cord when breaking into a house (Pope 2002:268-269). The Supreme Court found that capital punishment was used in a discriminatory way on the basis of “race, religion, wealth, social position, or class” (Barron 2006). The Court’s ruling was far from unanimous, establishing that Furman was not eligible for the death penalty by a narrow 5 to 4 majority decision. After reviewing all four cases, the Court found the death penalty was arbitrary in its entirety, as it showed no consistency in penalizing, and had great discriminatory elements, and they issued a nationwide moratorium (Pope 2002:269). “Gender” was never formally discussed as a possible discriminatory factor, but Supreme Court Justice Marshall did state in the official records that:

14 “There is also overwhelming evidence that the death penalty is employed against men and not

women. It is difficult to understand why women have received such favored treatment since the purposes allegedly served by capital punishment seemingly are equally applicable to both sexes.”

(Marshall in Reza 2005: 180)

The problems with capital punishment were things that the Court considered to be fixable – that state representatives would have greater influence in the criminal justice process and lawmaking. The Court would also impose limitations on jury discretion during sentencing with new and improved guidelines for determining capital cases. Only a few years later, in 1976, the Court found that the necessary revisions had been made, and that the death penalty could no longer be considered arbitrary. They allowed states to reinstate capital punishment as they saw fit, which 35 states chose to do, even if the state representatives still reflected a mainly white, male, middle-or upper-class, as many states still had highly engrained practices of racial segregation, and women were still much underrepresented. (Pope 2002:272-273)

Given the large number of states that chose to reinstate this punishment, the Court found justifications for their decision on grounds that it reflected a great community wish. However, the decision on whether or not to reinstate the death penalty was up to state legislators, and the Court did not question whether or not these legislators in fact represented their community. Nevertheless, they concluded that juries were now able to provide an objective, non-discriminatory application of the death penalty. What makes this all the more interesting is that a capital jury at that time did not consist of randomly selected individuals of a community, but was only allowed to be made up of those supportive of capital punishment in the first place (Pope 2002:272-273).

2.2

Crime-based theory

In developing her theory that any leniency shown towards women is based on the nature of the crime itself, rather than on actual consideration of gender, Elizabeth Rapaport focused on the post-moratorium application of the guidelines of the Supreme Court. The revisions implemented by the Court in light of the Furman case consisted of rather leaving it up to the discretion of the jury and the judge. The Court implemented weighing factors when determining whether or not a case should be up for capital

15 punishment – factors which were supposed to be highly scientific, to assure the equality and fairness of the justice system. There are three components in these guidelines for the jury to abide by in determining if someone is eligible for capital punishment: 1) prior criminal record, 2) the severity of the crime, and 3) the level of culpability that can be determined (Pope 2002:277-278; Rapaport 1991:372).

The revisions by the Court not only limited the discretion of the jurors, but also completely rejected the death penalty for certain crimes previously eligible if they could not be proven to have resulted in the loss of a life, such as espionage, trafficking etc. The mandatory death penalty sentence for certain crimes was also replaced by more discretionary sentencing – further limiting what crimes were eligible for the death penalty to crimes with an excessively aggravated nature (Rapaport 2010:555-556).2

States vary in determining what the aggravating and mitigating factors might be, and it is left to the discretion of each state court to make that interpretation, but most states have also passed statutes covering such required factors. Generally, it can be said that the types of murders that can be categorized as eligible for the death penalty are: 1) predatory murder; 2) killing to resist law enforcement or legal consequences (for instance killing a police officer, a corrections officer or other law enforcment person); and 3) murders that were committed with extreme heinousness and brutality:

1) Predatory murder is murder that is committed for some gain. Usually it involves financial gain, but it can also be other factors such as sexual. These murders are sometimes committed through a hired third party, and as such the offender might be convicted even if he or she did not actually carry out the murder. Hiring someone would in fact show the planned nature of the crime, which could be interpreted as one of the aggrevating factors.

2) Resisting law enforcement includes murders carried out to prevent oneself from being arrested. States differ on which of these kinds of cases are to be considered capital offenses. For instance, in some states this goes beyond those I already mentioned, to include all government officials.

3) In determining the heineousness of the crime, jurors consider the very nature of the offense, for instance if it was a multiple-victim case, the process of the kill – methods such as the use of explosives, or poison are considered especially harsh – along with any other act of torture (Rapaport 1991:376-377).

16

2.2.1

Executive clemency

The reforms regarding the discretionary guidelines and restrictions on judges and jurors have not managed to do the same for executive powers which have been spared and protected by the Constitution. This authority is subject to very little inspection and has therefore a lot of power with little to no examination or legal review. Before the Furman case, there was neither the extensive appeal process there is today, nor the same possibilities to have one’s sentence commuted or even pardoned. Today, each U.S. death penalty state has some procedure outlined for clemency (Rapaport 2001:974-975). In 15 states (DPIC2), that power is solely the authority of the governor, with the exception of the United States President, who has had the opportunity to exert that power provided to him by the Constitution (U.S. Constitution, 11th amendment, section 2). Contributing

factors to a Governor’s decision might reflect personal or political bias, for instance, that a liberal governor might free someone convicted of narcotics possession, while a conservative governor might free someone convicted of a gun-related offense. An executive decision can, in other words, have more to do with political conviction rather than the severity of the crime (Rapaport: 2001:969,1001).

Two-thirds of all death sentences have been commuted, but very few of those by executive power (Rapaport 2001:975-976). The probably most well-known or frequently discussed female capital case was that of Karla Faye Tucker in Texas. Tucker and her boyfriend, Danny Garret, broke into the home of Jerry Dean to rob him, primarily of his motorcycle. When they entered his home in the middle of the night, they both brutally assaulted Dean – Garret with a hammer, Tucker with a pickax. They later discovered Dean’s girlfriend, Deborah Thorton, in the next room, and Tucker proceeded to “pick” her as well. According to Tucker herself, both victims begged to be killed during the picking. The following day, when police searched the apartment, they found the pickax still inserted in Thorton’s chest. While in custody, Tucker revealed that she felt sexual pleasure from the picking, and she apparently told her sister that “I come with every stroke”. The heinousness of the crime was taken into special consideration by the Court, along with the sexual gratification, and the pecuniary motive. They found that due to her “turbulent past”, and “disturbingly unfeminine manner”, she would never be able to be reinstated in society (Rapaport 2010:34-35).

In Tucker’s case, it was former president (then Governor) George W. Bush who had the option of stopping the planned execution. This event was surrounded by a lot of

17 media coverage and speculation as to whether or not it would benefit his political career retirement (Rapaport 2001:967-968).

“If you believe in capital punishment for one, you believe in it for everybody. If you don’t believe in it, don’t believe in it for anybody.” (Karla Faye Tucker in Cruishank 1999:1113)

Tucker explicitly stated that the issue of gender was not relevant in her case, but this might have been an effort to save her own life. This statement was made in the last phase of her appeals, when only a commutation from the Governor could spare her life, and in light of the media attention given to this case, largely regarding the fact that Karla was a woman, Bush made a statement that gender would not factor into his decision. By undermining the gender issue, some have argued that this might have been Tucker’s attempt to appeal to Bush’s better graces (Cruishank 1999:1114).

Since the Tucker case, many other governors with this power of commutation have been equally, if not more, convinced that allowing a female to be executed under their watch would no more bring into question their capabilities and political integrity than it would to commute her sentence, as this might raise questions of gender bias (Rapaport 2001:967-968). However, since 1973, 271 out of 8,392 death sentences have received executive clemency. Out of those, only 11 were women (DPIC2). Most women received their clemency from Governors close to retirement (Rapaport 2001:968). In fact, since 1976, there have been five occasions when a retiring Governor has granted clemency for all death row inmates at once, accounting for over 200 of 271 clemencies (DPIC2).

A couple of years after Tucker’s death sentence, another capital case stood out, and once again was of interest for the Supreme Court in light of the 8th and 14thAmendments

of the Constitution. This time, the accused was a man, Warren McCleskey, who was found guilty of robbery and murder in the state of Georgia, who claimed that there was a clear racial bias in the state of Georgia to the disadvantage of blacks. However, the Supreme Court found that while they could recognize that the system was not perfect, no system was, and that failing to issue a capital sentence to McCleskey would unduly affect other similar cases, perhaps even regarding lesser punishments, all in the name of discrimination (Rapaport 2010:7-8).

18 “The claim that [McCleskey's] sentence rests on the irrelevant factor of race easily could be extended to apply to claims based on unexplained discrepancies that correlate to membership in other minority groups, and even to gender."

(Supreme Court Justice Powell in Rapaport 2010:8)

The outcome of the case was the consensus of the Supreme Court justices that no one is to be spared from their punishment on the ground of discrimination, if he or she cannot prove that the discrimination was deliberate. Furthermore, that it would be absurd if claims of racial discrimination would lead to claims regarding gender discrimination (Rapaport 2010:7-8).

2.2.2

Gender-related capital crime statistics

There have been a total of 1,295 executions in the United States since 1976 (DPIC4); 3,189 persons remain on death row (DPIC5), and 58 of those are women (Streib 2011: 7). Since the Furman case, 174 women have received a death sentence in the United States: of those, 12 have been executed; 104 have had their sentenced reduced, received clemency, or died of natural causes; and currently, 58 women remain on death row (Streib 2011:8-9). For a complete list of these 174 sentences, see Appendix B. The DPIC annually releases a compilation of death penalty statistics in the United States, this year with the help of extensive research conducted by law professor, attorney, and author Victor L. Streib. One out of ten (10%) of those arrested for murder are women; about one out of 50 (2.1%) of those receiving a death sentence are women; one out of 67 (1.8%) of those currently on death row are women; and about 1 out of 100 (0.9%) of those actually executed in the modern death penalty era (post-moratorium) are women. Below is an annual breakdown of men and women death sentenced since the Furman case (see Table 1):

19 Table 1: Death sentences for female offenders 1973-2011

Year Total Death Sentences Female Death Sentences Portion of Total 1973 42 1 2.4% 1974 149 1 0.7% 1975 298 8 2.3% 1976 233 3 1.3% 1977 137 1 0.7% 1978 185 4 2.1% 1979 151 4 2.6% 1980 173 2 1.1% 1981 224 3 1.3% 1982 265 5 1.8% 1983 252 4 1.6% 1984 285 8 2.8% 1985 266 5 1.8% 1986 300 3 1.0% 1987 289 5 1.7% 1988 290 5 1.7% 1989 259 11 4.2% 1990 252 7 2.7% 1991 267 6 2.2% 1992 287 10 3.5% 1993 289 6 2.0% 1994 315 5 1.6% 1995 318 7 2.2% 1996 320 2 0.6% 1997 276 2 0.7% 1998 300 7 2.3% 1999 279 5 1.8% 2000 231 7 3.1% 2001 163 2 1.3% 2002 159 5 3.2% 2003 144 2 1.4% 2004 125 5 4.0% 2005 128 5 3.9% 2006 115 4 3.5% 2007 115 1 1.8% 2008 111 3 2.7% 2009 106 2 1.9% 2010 112 2 1.8% 2011 78 5 6.4% Totals: 8,392 174 2.1% Source: Streib 2011:8-9

20 With the exception of the year 2011, with the highest number of female death sentences in the current death penalty era – more than three times the post-Furman average – women have since 1972 accounted for less than 5% of all capital sentences each year, and out of the total amount of 8,392 people, only account for 174, or 2.1% (Streib 2011: 8-9).

Elizabeth Rapaport has conducted a string of studies about women and capital punishment throughout the past two decades, and she believes that the statistical imbalance can be explained by the existing legal directives, and indeed her theory is based on relating gender bias to the nature of the crime itself, including the felon’s criminal background. Looking at the implemented guidelines from the Supreme Court to the jurors in determining capital cases, when it comes to the first of the factoring components – prior convictions – men are much more likely to have prior convictions for violent crimes; in fact, more than 95% of all violent crimes committed in the U.S. are by men (Rapaport 1991:372; 2010:10). As for determining the severity of the crime, the judges and jurors are asked to take into consideration excessive violence, torture, or extremely heinous features of the offense. Such factors are left to the discretion of the court, and are inevitably treated very subjectively. It can be noted that similar to dominating the statistics on violent crime, men account for a much higher degree of excessively violent murder. Moreover, one factor which can be more objectively measured when determining the brutality of a killing is to consider the number of murder victims in the case. This component is substantially more common with a man as the offender rather than a woman. In fact, from 1976-1987, close to 93% of all multiple-murder suspects were men. This suggests that a statistical imbalance can in fact be explained in an objective way (Rapaport 2010:373). The third aspect – determining the level of culpability – is where the main difficulty lies, and where subjective notions of the jurors have greatest influence. This entails looking at ulterior motives, for instance pecuniary gain or escaping punishment, but also at the behavioral patterns of the suspect and possible mitigating factors present. This will be further elaborated on in section 2.3.

In light of the revision by the Supreme Court, murder, as a crime on its own, is very seldom considered a capital offense, and when looking at the nature of the crimes, while women commit 1 in 10 murders, they very seldom commit felony murders, i.e. a murder committed together with another serious crime – another felony. Nationally, felony murders make up over 75% of all capital sentences in the U. S., and in some states, that

21 number is well over 80%. The largest category of felony murders represented on death row is robbery murder – a crime where men are 24 times more represented as the offender than women. Other felonies can be rape, burglary, arson etc. These are all factors taken into account when determining sentencing (Rapaport 1991:370; 2010:9-10).

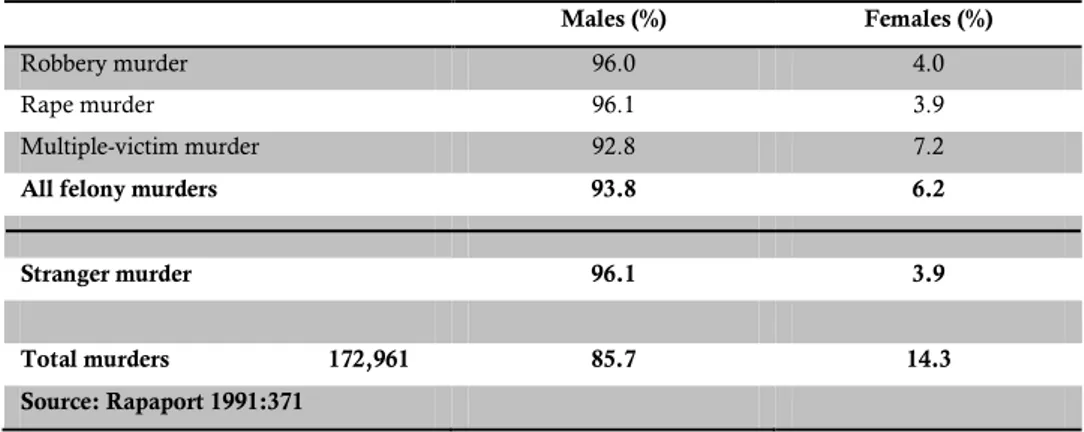

In one of Rapaport’s studies, where she focuses on the first decade after the reinstatement in 1976, she looks at the statistics of men and women and the categories of murder they commit, specifically those types that are most likely to lead to the death penalty. According to her research, out of all 172,961 murders (including domestic killings) committed during those years, women were responsible for 14.3%. They accounted for 6.2% of all felony murders and or multiple-victim murders – those that have been determined by the Supreme Court to be considered the most severe, and that are most likely to become capital cases (see Table 2).

Table 2: Types of Murder Most Eligible for Capital Punishment, Committed 1976-1987

Males (%) Females (%)

Robbery murder 96.0 4.0

Rape murder 96.1 3.9

Multiple-victim murder 92.8 7.2

All felony murders 93.8 6.2 Stranger murder 96.1 3.9 Total murders 172,961 85.7 14.3 Source: Rapaport 1991:371

Stranger murder is significantly dominated by men, specifically 96.1%. We find much greater equality between the sexes when it comes to domestic homicides. Rapaport’s study shows that during the same time period, over 90% of murders committed by women were against an intimate (spouse, child, etc.), or other person known to the suspect. Table 3 breaks down the categories of murders by male and female suspects. As we can see, the gap between intimate murder and stranger murder is 65.5% to 5% for women, for men, the same gap is only 22.1% to 20.4% (Rapaport 1991:371).

22

Relationship of Victim to Suspect Murder by male suspects (%) Murder by female suspect (%)

Intimate: 22.1 65.5

Spouse, lover, ex 11.8 48.9

Child 2.7 10.4 Other family 7.6 6.2 Acquaintance, friend, other known 47.1 26.9

Stranger 20.4 5.0

Unknown 10.2 3.3

99.8% 100.0%

Source: Rapaport 1991:371

In a similar study, Rapaport found that of those men and women on death row, domestic killings account for 12% of the men, and 48% of the women (see Table 4). This she says is due to the fact that stranger violence is considered much more heinous than domestic violence. Reasons for this she finds are that in domestic killings, the victim is considered to have part in the killing, for reasons such as abuse or abandonment, while stranger killings seem much more unprovoked, and therefore more frightening. They are generally thought to be cold-blooded and calculated, assuming that felony murders are planned and intentional when in fact they often are not (Rapaport 1991:381). Stranger killings may also be regarded as more severe due to the element of future danger– allegedly that there is a greater risk that people who kill strangers may kill again. Domestic killings are believed to be the result of a more targeted anger with a specific objective, less likely to continue after completion. This does not, however, consider the future possible danger to other family members (Rapaport 2010:63). That we regard stranger violence as more severe than domestic violence, Rapaport argues, is the reason for the statistical imbalance between men and women on death row – not an alleged leniency (Shatz 2011:19). This theory is in stark contrast with the theory proposed by Streib, as we will see in section 2.3.1 below.

Motives behind domestic killing have a clearly dinstict gender separation as to what is more frequent, according to Rapaport. Women are likely to kill an intimate due to fear or an act of self-defense. Such crimes seldom become capital cases unless there was some other gain as a motive linked to the kill (Rapaport 1991:370; 2010:10). For men, domestic killing is largely motivated by jealousy and separation – usually when a woman has left her male partner, and he proceeds to stalk her and kill her. Being a victim of infidelity, and the sense of abandonment, can be conceived as mitigating factors, i.e. lessening the severity of the crime. Separation killings by men are often reduced to manslaughter due

23 to the emotional trauma the offender has suffered, pushing him into a state of panic – even without a temporary insanity plea, and even with a lack of remorse (Rapaport 2009:1540; 2010:61). North Carolina, Illinois and Florida have gone so far as to include exemption clauses for their use of capital punishment for just such circumstances of separation killings (Pope 2002:275). In contrast, those women who do end up on death row for domestic murder, the motive behind the crime has primarily been pecuniary, whereas for men, domestic killings have primarily had a retaliatory motive (see Table 5).

Domestic Death Row – Gender and Motive, 1978-1989* Table 4:

Men (No.) Men (%) Women (No.) Women (%) No. of death sentences 699 54

Total in which killer and

victim were intimates 83 12 26 48 Source: Rapaport 2009:1517 Table 5: Men % Women % Pecuniary motive 13 69 Retaliatory motive 48 8 Other 39 23 Total 100 100 Source: Rapaport 2009:1517

*Because of the relatively few women on death row, while she focused on men sentenced in Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, North

Carolina, and Pennsylvania, she needed to include women sentenced nationally.

Domestic homocides rarely became capital cases unless there was a pecuniary gain, there were multiple victims, or the violence was particularly heinous (Rapaport 1991:378). Considering that women statistically account for much more intimate murders than stranger murders, some suggest that this is the result of some leniency specifically towards women. Meanwhile, women are also the more often than men killed in the home; in fact, women in no other place than a domestic setting are more likely to become a murder victim (Shatz 2011:39). Domestic murder is an extremely limited part of the much broader problem of domestic violence, where women are the primary victims (Rapaport 2010:63). In a statistical compilation by USDOJ, they found that from 1998-2002, murder accounted for less than 0.5% of all cases of domestic violence; women were

24 the victims of about 85% of all spouse- or partner-inflicted abuse; and men were the violent actor in about 75% of all reported domestic violence cases (USDOJ 2005:1).

To summarize the Rapaport theory, gender bias in capital crimes and sentencing is clearly argued to be based on the nature of the crime only, and her theory dismisses or discounts the notion of any leniency shown towards women on the basis of consideration of their gender as such.

2.3 Chivalry theory

One of the most widely endorsed theoretical approaches attempting to explain the statistical imbalance between men and women within the U.S. criminal justice system is the “Chivalry Theory”. In contrast to other presumably disadvantaged social groups, for instance African-Americans and the poor, it has been claimed that women have benefitted from their social stance because of their gender. This is the basis of chivalry theory, which thus takes an entirely different approach to Rapaport’s theory, i.e. that leniency towards women is based on the nature of the crime itself.

2.3.1

Origins of chivalry concepts

Chivalry – a code of conduct traced back to the Middle-Ages, was a set of norms for men to on how to behave when there was no real existing governance. Initially, chivalry was a standard for how to act with honor at for instance a time of war, not on the basis of gender, but of class. However, with time, it came to be understood as a grace exclusively bestowed upon women, for the sake of being women (Shatz 2011:2-4).

As late as the 1960s, the Supreme Court validated Florida state laws that relieved women from participating in public responsibilities, specifically jury duty, as they had other obligations in the home and with their family. This was clearly a case of chivalry granted exclusively towards women, emphasizing the public and private spheres as platforms in which gender separation was explicitly accepted. After loud critique from the gradually growing feminist movement in the 1970-early 80s, the Court responded by shifting their views, finding that women would not benefit from being treated differently, not even by “positive” special treatment – even calling it unconstitutional, as it would

25 suggest that women, as an entire gender, suffered from some handicap that ultimately made them inferior to men (Shatz 2011:5-6).

2.3.2

Application of chivalry in criminal justice

The developments in the Court’s attempts to curb the possible influences of chivalry did not, however, terminate notions of chivalry nor, some would say, chivalrous behavior. The chivalry hypothesis suggests that because women are weaker, and more dependent on male influences and protection, they can’t be fully responsible for their actions, nor be regarded as equally culpable as their male counterparts. This was first introduced and discussed in the 1970s, in relation to an overwhelming consideration that women would be more agreeable and able to rehabilitate (Heberle 1999:1107; Herzog, Oreg 2008:45). The theory was further elaborated by Victor Streib in the late 1990s, and he is now considered to be the author of the theory.

Streib believes that the statistical inequality can be traced to a gender bias within the U.S. criminal justice system. He calls the legal proceedings for women being tried for capital cases “rare and inconsistent” and even irrational. He believes that we are inclined to show more sentiment towards a woman capital offender than to a man (and this goes for judges and jurors as well), regardless of the nature of the murder in question, and that the criminal justice process “take[s] it easy on women” (Streib 2006a), for expressing what he calls a “female quality of emotionality” (Streib 2006b:5). Streib suggests that in order to rectify this imbalance, women ought to be judged on the same grounds as men, but that unfortunately society will not condone a change in procedure that would seem to punitively affect women because of the existing chivalry attitude (Streib 2006a).

Criminal Justice and Sociology professors Sergio Herzog and Shaul Oreg have written a paper further elaborating Streib’s theory, and exploring the sexist nature of this chivalry. They claim that chivalry can be found in all levels of criminal justice procedures – that whenever judgment is within the discretion of the court, women benefit from it and receive lesser punishments than men do. They also found that in accordance with a social understanding that women are weak and need protection rather than punishment, they are less responsible for their wrongdoings, and are much more the “victims of an environment that has failed to provide the necessary guidance and supervision that women generally deserve.” (Herzog, Oreg 2008:47-48)

26

2.3.3

Evil Woman Theory

Herzog and Oreg did, however, find that the concept of chivalry was not universally applicable, because in many cases they found that women sometimes received harsher treatment than men, especially in capital cases. This discovery gave rise to “Selective Chivalry”, more commonly called “Evil Woman Theory”, suggesting that leniency can be found only in cases where the woman in question has performed in accordance to her stereotypical gender role. In other cases, she does not receive any chivalrous treatment, as she is considered to be in direct defiance of her own identity. Such defiant behavior could be a mother killing her own child; or even a woman with a tough appearance, and particularly a woman who maintains her innocence and shows no remorse. She needs to fit certain gender criteria in order to receive these benefits of chivalry, e.g. she should be financially subordinate to her male peers, be heterosexual, and hopefully be a married housewife (Herzog, Oreg 2008:48-49). Traditionally, a woman killing her “master” was considered not only to have committed murder, but also treason (Shatz 2011:41).

A woman is thus not merely judged for the crime she has committed, but her very femininity is questioned. Feminist professor and author Renée Heberle says that if a man were to commit the same crime, there is nothing to suggest that his masculinity would be similarly questioned. If anything, the only related concern would be that perhaps he took his masculinity too far (Heberle 1999:1106; Herzog, Oreg 2008:50). In this sense, women much more than men need to portray themselves in a certain way – as a good mother, loving wife, even an obedient daughter – in order to avoid a harsh sentence, and in fact there appears to be a difference is the average punishment for men vs. women who kill their parents (Pope 2002:275). Other factors such as race and economy certainly also elicit prejudice and discrimination, but the evaluation of the offender’s social stance is never so bluntly exposed and incorporated in the judgment as when it comes to gender (Heberle 1999: 1106; Herzog, Oreg 2008:50).

Heberle studied two cases of filicide: Darlie Lynn Routier and Susan Smith. In both cases, the prosecutor failed to prove that the deaths were premeditated. When studying the court materials from both cases, Heberle found that Routier, who kept swearing her innocence, is described as “remote and cold”, and most importantly, she is described as not motherly. Meanwhile, Smith, is described weak and vulnerable, incapable of being in control of her emotions, much like a child. Unlike Routier, Smith’s identity as a mother

27 is never questioned. Smith received a life sentence, Routier a death sentence, and is currently on death row awaiting execution (Heberle 1999:1106; Streib 2011:14).

Herzog and Oreg find two distinct types of sexism: hostile sexism and benevolent sexism (Herzog, Oreg 2008:51). Hostile sexism views women as inferior or even duplicitous. Sociology professor Otto Pollack, in his controversial “Criminality of Women”, stated that since women are capable of concealing their menstruations and faking their orgasms, they are also capable in concealing criminal behavior. Therefore, women are getting away with severe crimes (Heberle 1999:1103). Pollack’s theory falls very well into the concept of hostile sexism. Benevolent sexism, which as the term suggests is considered a positive bias towards women, embodies more traditional views of women as the primary caretakers of their children and the home, valuing their feminine qualities as strengths that men do not possess. They do, however, very much correlate, both expressing an existing male dominance and maintaining a patriarchal societal structure. These two types of sexism have also been referred to as “the carrot and the stick” of the criminal justice system, which in accordance with the Evil Woman Theory work together to keep women in line with their gender identity (Herzog, Oreg 2008:51).

To summarize Streib’s chivalry-base theory, the focus is clearly placed on leniency shown towards women based on the fact that they are women, arising from deep-seated traditional and social perception of women as needing to be treated more gently than men, regardless of the nature of the crime itself.

2.4 Dominance and power structure

2.4.1

Different Voice and Dominance Theory

Traditionally, feminism has aimed to question and crush established notions of what constitutes “female” and “male” qualities – as a factor in criminal behavior or in any other societal aspect. But in the early 1980s, Carol Gilligan wrote a book contradicting this belief, where she found unique characteristics belonging to the respective sexes, and that emphasizing our distinct qualities is the only way to create a society that equally embodies both, rather than the male dominance we see today.

28 Specifically when it comes to law, Gilligan claims that while men are primarily focused on duties, rationality, and justice (“the ethic of justice”), women are more empathetic and caring (“the ethic of care”). The male ethic of justice is clearly the dominant method of legal practice, where circumstantial elements in a crime have little or no significance in a legally just outcome, even in a capital case (Pope 2002:260-261). Ethics of care, in contrast, constitute a different voice which feminists claim could influence the otherwise cold and dispassionate environment of criminal law with a broader approach – specifically by giving more attention to relationships and interdependencies existing within a criminal case (Pope 2002:263). However, Gilligan also claims that even though more and more women have “infiltrated” the otherwise highly male arena of criminal law, women have assumed an existing male approach to it, rather than adding their feminine qualities to the mix – enabling an “ethic of justice” dominance to prevail and preventing it from being tempered by the “ethic of care” (Pope 2002:362).

As a critique to Gilligan’s theory, we have Catharine MacKinnon’s “Dominance Theory”. MacKinnon says that further emphasizing a supposed difference between genders simply enhances any existing inequality, rather than fights it (Pope 2002:264). An alleged concept of gender characteristics must be removed altogether, rather than appreciated and valued as positive, but distinct qualities. Instead of focusing on “gender” as a way to measure equality, she stresses that feminist efforts should go towards concepts of “dominance” and “powerlessness”. By this she means that women have been made powerless, in a legal setting as well as any other, and the challenge is to gain power, any means necessary (Ukeles 2007:27-28).

There is a continued male dominance in the U.S. criminal justice system, where in the higher legal institutions such as the Supreme Court, women are far from represented according to their percentage of the United States population. Even in more local state judicial systems, women are significantly underrepresented. Furthermore, capital punishment is still being discussed from a U.S. Constitution perspective – written entirely by white men (Pope 2002:258). “Different Voice Theory” and “Dominance Theory”, while not in agreement, find common ground in acknowledging the predominantly male presence in the legal system.

29

2.4.2

Rescuing subordination

Aristotle believed that punishment should not be distributed equally based on crime, but be individualized and given in proportion to a person’s worth, based on their position in societal hierarchy. Not surprisingly, he found that a patriarchal society – both publicly and domestically – is the most proper and preferable form of governance (Horowitz 1976:187). His concept of woman as “a mutilated male” (Horowitz 1976:184), and inferior to men has been an enduring notion lingering thousands of years, and remaining an active part of society today – as a matter not limited to size and physical strength, but to include capabilities of the mind (Coughlin 1994:29)3.

Along the lines of “Chivalry Theory”, there is a widespread idea that women have been relieved from the same legal consequences their male counterparts would face, on the grounds that women cannot be expected to resist pressures from their male partners – even if it includes criminal activity – an excuse not afforded to men. This suggests that women lack the responsibility in maintaining authority and the capability of lawful conduct when there are unlawful influences by their male partners (Coughlin 1994:5-7).

The U.S. criminal justice system shows signs of wanting women to embrace their victim status. Up until the 70s, there was such a thing as the “marital coercion defense”, which only applied to married women. The theory, and correlated legal defense, noted that regarding minor threats, women were able to maintain self-control, but when facing greater threats, women would abide by the will of their husbands. Not only did this defense underline an already established theory that women are psychologically weak in relation to men, it made some great assumptions about the relationship between a man and a woman in a marriage (Coughlin 1994:29-31).

This defense has since been replaced by the current “Battered Woman Syndrome”, in an attempt to minimize the severity of the committed crime. In brief, the defense entails that if a husband, or other strong male figure, is present at the time of a crime committed by a woman, she can be assumed to have acted on behalf of the male – under his will – which would require the prosecutor to prove the independent action of the woman. This “male presence” has even been broadly interpreted as a mere psychological one, rather than physical (Coughlin 1994:29-31). This defense could also include bringing

3 Note: Aristotle went to far as to draw the “conclusion” that because of their natural inferiority, women

have fewer teeth than men. As Bertrand Russell would later point out, if Aristotle had ever bothered to open Mrs. Aristotle’s mouth and count, he might have seen the error of his conclusion (Russell 1952: ch.1).