Theorizing the External Actorness of

the European Union in Global

Development Governance

The Case of Aid Effectiveness in Post-Cotonou Development

Policy

Maria Ioannou

International Relations

Dept. of Global Political Studies Bachelor programme – IR103L 15 credits thesis

Thesis submitted [Spring/2021] Supervisor: [Corina Filipescu]

Abstract

The European Union (EU) is the world’s leading development donor, playing apivotal role in shaping development norms. This paper aims to investigate the extent to which the EU has been effective in its external aid actorness towards global poverty eradication during the post-Cotonou negotiation period (2000-2020). The theoretical framework of Sjöstedt’s (1977) Actorness

Theory is constructed upon the premises of Social Constructivism. To

operationalize “actorness”, Brattberg and Rhinard’s (2012) criteria of context,

coherence, consistency, and capability are utilized. The research triangulates

the methods of Discourse Historical Analysis and Thematic Content Analysis to assess the EU’s nom-setting policy discourse. The analysis suggests that the Union scores highly in the context and capability criteria, as it is recognized as a legitimate development actor and possesses mechanisms to reach aid agreements, while lacks coherence and consistency due to inadequate policy implementation and commitment to McKee et al.’s (2020) Aid Quality Index. The thesis concludes that the EU’s aid effectiveness has decreased due to its actorness being increasingly linked to foreign policy considerations in response to emerging challenges in development cooperation. The research underlines the significance of analysing the empirical linkage between EU’s actorness and effectiveness for the field of International Relations.

Keywords: global development governance, aid effectiveness, EU actorness, Social

Constructivism, Role Theory, norms, poverty eradication, foreign policy, development policy.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Background and Research Problem ... 1

1.2. Research Aim and Objectives ... 2

1.3. Thesis Outline ... 2

2. Literature Review... 3

2.1. Theorizing the EU as a Global Development Actor: A Framework of Analysis ... 3

2.2. EU Development Policy and the New Aid Architecture ... 5

2.3. The EU’s Leadership Paradox: Between Actorness and Effectiveness ... 6

2.4. Summary... 8

3. Methods: Measuring EU Effectiveness in Development Cooperation ... 9

3.1. Ontology and Epistemology ... 9

3.2. Variables and Normative Research Design: Longitudinal Case Study Research ... 10

3.3. Data Selection and Source Criticism ... 11

3.4. Qualitative Discourse Historical Analysis (DHA) ... 12

3.5. Quantifying EU Aid Effectiveness: Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) ... 15

3.6. Strengths and Limitations ... 17

4. Analysing the EU’s Aid Effectiveness in Development Cooperation: Actorness Theory ... 18

4.1. Context: Are there favourable structural conditions for the EU to act? ... 19

4.1.1. The EU’s Empirical Policy Setting in Development Governance ... 19

4.1.2. The EU’s Internal Actorness Context ... 20

4.1.3. The EU’s External Actorness Context ... 21

4.1.4. Summary ... 23

4.2. Capability: Does the EU utilise practical instruments in development effectiveness negotiations? ... 23

4.2.2. The Busan Declaration (2011) Negotiations ... 25

4.2.3. Summary: The Post-Busan Negotiation Framework ... 26

4.3. Coherence: Does the EU display aligned values and policy outputs? ...27

4.3.1. The 2005 European Development Consensus (ECD) ... 27

4.3.2. The 2009 Lisbon Treaty (LT) ... 28

4.3.3. The 2011 Agenda for Change (AfC) ... 29

4.3.4. The 2016 Global Strategy (EUGS) ... 30

4.3.5. The 2017 European Consensus for Development (ECD) ... 31

4.3.6. Summary and Comparison... 32

4.4. Consistency: Does the EU carry out its commitment to aid quality within its policy documents? ... 32

4.4.1. Prioritization ... 34

4.4.2. Ownership ... 35

4.4.3. Transparency ... 35

4.4.4. Learning ... 36

4.4.5. Summary and Comparison... 36

4.5. Discussion: The Evolution of the EU’s Aid Effectiveness Norm in post-Cotonou Development Policy...37

4.5.1. Assessing the EU’s Donor Role: Normative Power Europe? ... 37

4.5.2. Analytical Significance and Delimitations ... 40

5. Conclusion ... 40 5.1. Future Research ... 42 6. Bibliography ... 43 7. Appendices ... 55 Appendix A ...55 Appendix B ...56 Appendix C ...56

Appendix D ...57 Appendix E...60

List of Figures and Tables

Figures

Figure A. Visual Representation of the DHA Model on EU Development Aid Actorness. 13 Figure B. Evolution of EU Actorness Context in the face of Internal and External

Development Challenges during the Cotonou Convention (2000-2020). ... 20 Figure C. Bar Graph of TCA Depicting the Presence of Aid Quality Indicators within EU Development Policy Documents... 34 Figure D. Official Development Assistance: The EU is the world’s largest donor. ... 55 Figure E. Systematic decline of EU gross ODA since the year 2016. ... 56 Figure F. Visualization of the Evolution of Theoretical Work in the Political Science of the EU ... 56 Figure G. Updated Actorness Framework for Future Analyses on the EU. ... 60

Tables

Table A. Actorness Criteria for DHA... 14 Table B. Quality Index Coding Manual for TCA of Actorness consistency variable. ... 15 Table C. Evolution of the EU’s effectiveness norm in post-Cotonou development policy negotiations (2005-2017). ... 40 Table D. Coding Manual Protocol: Word search of Aid Quality Indices in Five Major EU Development Policy Documents... 57

List of Abbreviations

AfC: Agenda for Change

BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa DAC: Development Assistance Committee

DHA: Discourse Historical Analysis:

ECD: The European Consensus for Development EU: European Union

EUGS: Global Strategy

GNI: Gross National Income

GPEDC: Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation IR: International Relations

LT: Lisbon Treaty

MDGs: Millennium Development Goals ODA: Official Development Assistance

OECD: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development PCD: Policy Coherence for Development

SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals TCA: Thematic Content Analysis UN: United Nations

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Global poverty constitutes one of the most pressing threats in the global political scene creating an imminent demand for Western countries to provide development assistance to reduce inequality, through having four-times stronger economies than the sum of the developing world (Clair, 2006: 139; Hunt, 2017:162). The need for development aid in response to rising poverty levels constitutes an issue of high politics in the pursuit of global governance, creating a rising demand for donor action (Carbone, 2007:11).

Development aid is defined as the delivery of expertise and funds in response to financial,

environmental, and humanitarian issues, reflecting the mechanism for global wealth distribution (Lundsgaarde, 2012: 704; OECD, 2018: 11). Aid allocation instigated after World War II through the formation of the neoliberal Bretton Woods Institutions, and is aligned with the democratic principles of distributive justice (Hoeven, 2000:5). Aid’s significance is the eradication of extreme poverty, in line with the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the UN 2030 Agenda and the pro-poor paradigm of “leaving no-one behind” (ibid).

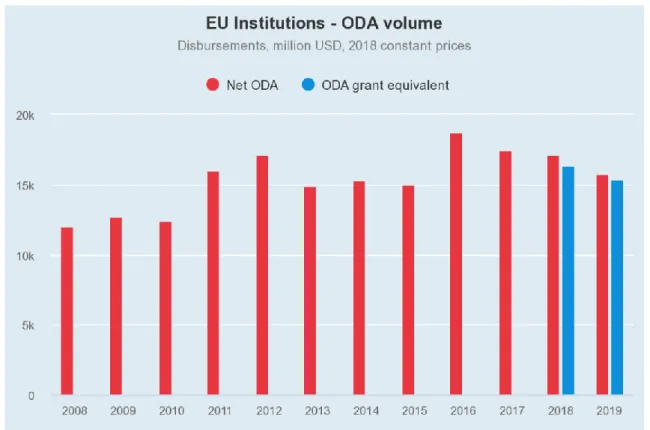

Through providing more than half of the world’s development aid, the European Union (EU) is the largest multilateral donor, namely allocating approximately 75.2 million euros and being present in all developing countries (OECD, 2018: 17, Appendix A). Therefore, the promotion of sustainable development and poverty eradication in the global South represent pivotal commitments of the EU (Bretherton and Vogler, 2008: 401). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) constitutes the overarching legal framework for the promotion of Official Development Assistance (ODA) since 1961, coordinating the EU’s attainment of the 0.7% UN target in aid from its Gross National Income (GNI) (Carbone, 2010: 17). Thus, it acts as a “moral bookkeeper” between OECD donors to strengthen aid effectiveness norms (Hattori, 2003: 244). Aid

effectiveness is defined as “policy attainment” in development governance (Brattberg and

1.2. Research Problem

Nevertheless, since the early 2000s, the development aid discourse has witnessed an increased politicization, resulting in aid diverting from its original humanitarian objectives (Barder et al., 2010:25; Koch, 2015:383). Hence, there has been considerable debate in IR revolving around the EU’s development policy discourse due to its growing ineffectiveness in reducing global poverty, evidenced by a tendency towards “policy evaporation” and aid fragmentation in recent years (Bountagkidis et al, 2015: 85; Dearden, 2008: 188). To illustrate, since 2016, the EU’s aid volumes have significantly decreased, revealing a growing “aid fatigue”, plaguing the twenty-first century development cooperation landscape (OECD, 2018: 56; OECD, 2020:2; Appendix B). Hence, the shifts in the Union’s institutional framework together with the emergence of a contemporary aid architecture have uncovered fault-lines in its development policy (Mah, 2015: 58; Carbone and Keijzer, 2016: 40).

1.3. Research Aims and IR Relevance

Subsequently, the rationale of this paper is to problematize the Union’s normative discourse driving its development aid policy. By analysing the external dimension of the EU’s development policy, its effectiveness role in development cooperation will be evaluated. This brings about the research question: “To what extent is the European Union

effective in its external actorness in implementing development aid policy during the post-Cotonou (2000-2020) negotiation period in the fight towards the eradication of global poverty?”. This thesis aims to assess the impact of EU’s actorness on its development aid

effectiveness through evaluating policy documents published during the post-Cotonou Convention based on Sjöstedt’s (1977) Actorness Theory. The hypothesis holds that the EU is not a neutral development donor and has been ineffective in its external actorness due the impact of emerging challenges in global development governance and the lingering politico-economic interests hampering its aid effectiveness (Carbone, 2013a: 494). This research opts to contribute to the IR debate regarding the impact of norms on the EU’s external aid actorness (Saltnes, 2018: 525).

1.4. Thesis Outline

The upcoming section is Chapter 2, which will offer a critical examination of the existing literature on the EU’s role in development policy, uncovering the theoretical

framework, motivations and issues surrounding its actorness in global development governance and identifying the gap surrounding the EU’s development effectiveness discourse. In Chapter 3, a methodological design will be constructed, drawing upon the emerging theoretical approaches from the reviewed scholarship. Chapter 4 will present an analysis and comparative discussion of the EU’s effectiveness in aid allocation through a Discourse and Content analysis of its development policy documents published during the post-Cotonou period. The conclusion will be outlined in Chapter 5, providing an answer to the research question, summarizing the findings’ implications, and setting the premises for future research on the EU’s development actorness.

2. Literature Review

There is an expanding body of literature that examines the EU’s actorness role in global development governance which can be grouped into three dominant themes, specifically with regards to Theorizing the EU as a Global Development Actor, EU Development Policy

and the New Aid Architecture, and finally The EU’s Leadership Paradox.

2.1. Theorizing the EU as a Global Development Actor: A

Framework of Analysis

The debate revolving around the EU’s international actorness is one of the longest standing in the domain of IR (Rhinard and Sjöstedt, 2019: 4). The roots of stem from sociological historical institutionalist theory through the power of norm-formation (Bretherton and Vogler, 2006:21; Carbone, 2007:29). Exploring the nature of the EU’s actorness therefore has a normative nature and can be viewed according to Social

Constructivism as a “process” of IR (Hill and Smith, 2005: 10-11). According to the

Constructivist “logic of appropriateness”, the conception of a “role entrepreneur” influences the EU’s policymaking process (Orbie, 2008: 3 Krügiel and Steingass, 2019: 429). The intersubjective construction of the EU’s external actorness role in international affairs can be further elucidated through the normative lens of Role Theory (Aggestam and Johansson, 2017:1209). Scholar Klose argues that actorness requires participation in global governance and international law, interdependence in decision-making, and a legal framework (2018: 1145). Rondinelli and Heffron add that leadership is pivotal in the process of framing the EU’s actorness identity (2009:2; Aggestam, 2006: 17).

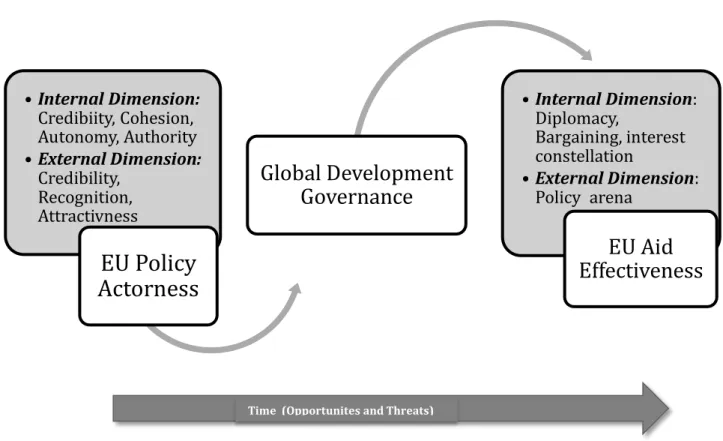

Scholar Sjöstedt’s Actorness Theory is utilized within the literature as the fundamental theoretical model to explain the EU’s external relations, which he defines as “the capacity to behave actively and deliberately in relation to other actors in the international system” (1977:16). Building on Sjöstedt’s work, Jupille and Caporaso (1998: 216-217) along with Bretherton and Vogler (2006: 24) have developed specific criteria for evaluating the EU’s international actorness, namely those of “recognition, authority, cohesion, autonomy, opportunity, and presence”, which are informed by the Social Constructivist tradition. Recognition entails partnership and interaction with third parties, authority

concerns the legal competence to act, autonomy concerns the distinctiveness of the EU’s

institutional apparatus during negotiations, cohesion refers to the extent of success in formulating common policies (Niemann and Bretherton, 2013: 267). Opportunity denotes the external contexts framing EU action, presence conceptualizes the EU’s ability to exert global influence thorough structural power and finally capability deals with the internal determinants of policy coherence (Bretherton and Vogler, 2006: 24-29).

Nevertheless, Niemann and Bretherton have criticized Sjöstedt’s Actorness Theory as difficult to operationalise and apply to specific cases due to the unique nature of the EU as a supranational and state-level actor, together with the extensive number of approaches to actorness being developed amongst scholars (2013: 265). Hence “conceptual clarity” is required within the field through the formation of mutually exclusive criteria (Driekens, 2017:1542). To tackle this conceptual limitation, Brattberg and Rhinard have presented an updated framework for actorness through employing a more empirical application of the theory to the domain of global governance, which simplifies the actorness definitions to four analytical variables, namely those of “context, capability, coherence and consistency” (2012:564, Table A). Within the literature, the EU has been found to generally portray high actorness in terms of context, and capabilities, but suffers from coherence and consistency issues (Brattberg and Rhinard, 2013:361).

By theorizing the EU’s actorness, pertinent scholarly work by Bretherton and Vogler (2006), Brattberg and Rhinard (2013), Rhinard and Sjöstedt (2019) have underlined its increasing importance as an international entity through conceptualizing it as a unique, “sui generis”, credible and effective actor in global affairs. A certain group of scholars has looked particularly into the EU’s role in foreign and security policy through investigating policy documents (Kaunert, 2010; MacKenzie, 2010; Brattberg and Rhinard, 2012; Mälksoo, 2016), while others have explored its role in climate policy (Delreux, 2014;

Groen and Niemann, 2013). However, a very limited number of authors have discussed the EU’s role as a development actor in its aid policy albeit being the largest global donor (Bretherton and Vogler, 2008: 401; Carbone, 2008; Orbie, 2012: 17; Lightfoot and Kim, 2017:1). According to Role Theory, the EU’s leadership role construction reflects its external actorness in development cooperation through as a social interaction between its partner countries (Klose, 2018: 114; Aggestam and Johansson, 2017: 1206). Hence, the EU carries a significant normative role in development cooperation to provide aid under the auspices of “humane internationalism” (Mah, 2015: 53).

2.2. EU Development Policy and the New Aid Architecture

Development policy is a clear case of the EU’s external actorness, acknowledging the fight towards global poverty reduction as the primary objective (Mah, 2015: 46). Nevertheless, it constitutes a constant test to the extent to which the EU can act effectively in the modern world order (Smith, 2013: 7). Scholars Rhinard and Sjöstedt, have pinpointed that the interactive nature of the EU’s aid actorness in development cooperation is impacted by internal and external factors that tend to intersect (2019: 16). Moreover, empirical analyses of the Union’s development actorness are relatively rare, while the impact of its development policy has been largely overlooked (Carbone, 2017: 531; Brattberg and Rhinard, 2013: 360).

This omission is surprising as the development landscape has undergone significant changes since the beginning of the 2000’s through the proliferation of development actors which are increasingly challenging the EU’s actorness norms (Carbone, 2015: 1-2). Particularly, research by scholar Mah has illustrated that the Cotonou Agreement instigated important changes for the EU’s development policy, placing increasing focus on aid coordination (2015: 45). The led to the creation of the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, which represents a milestone in global development governance for improving aid financing, resulting in an increase in development policy actorness by the EU (Carbone, 2010: 18; Sjöstedt, 2013: 144).

Since Cotonou, the EU has exerted significant donor influence through implementing development policies upon the developing world (Mold and Page, 2007: 19). According to Carbone (2013b:341) and Bountagklidis et al. (2015: 85), the recipient areas the EU’s post-Cotonou development policy has been predominantly focused on is the Eastern Neighbourhood, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa, while research by Kim and

Jensen emphasizes that human rights records of recipient countries significantly influence the EU’s allocation volumes, creating “aid darlings” and “aid orphans”, namely certain developing countries receiving less aid than others (2018: 178). Furthermore, research by Gore illustrates that the proliferation of non-DAC donor partnerships has negatively impacted the EU’s development discourse (2013:774). This is portrayed by the fact that the United States is a partner reluctant to cooperate and China is an emerging BRICS donor that deviates from the DAC’s normative principles in its development practices (Carbone, 2013: 350).

Furthermore, Smith (2013:2) and Kiratli (2021:14) have underlined a tendency towards the politicization of the EU’s development policy, creating a “security-development-migration nexus” that is resulting in a “spill-over effect” in aid allocation. Hence, throughout the years, EU development policy has broadened through incorporating “beyond aid” issues within its development agenda (Mold, 2007: 240). Moreover, realpolitik tends to interfere in the EU’s foreign aid policy, through evidence of neo-colonial attitudes and politico-economic motives within its discourse (ibid). Media coverage is found to accelerate political tendencies within the EU to provide aid towards humanitarian emergencies, creating the “CNN effect” and resulting in aid diverting from the altruistic poverty objectives (Arts et al, 2004: 90). Fejerskov highlights that for the Union to enhance its aid performance, its development policy should be constricted to fewer policy domains and abstain from asymmetric donor-recipient relations (2013: 6).

2.3. The EU’s Leadership Paradox: Between Development

Actorness and Effectiveness

One of the most researched areas in development policy is aid effectiveness (Carbone, 2017: 535). Hence, scholarly interest in examining the EU’s role as a development actor has diverted from the assessment of its internal actorness role to its external impact in the global arena (Bretherton and Vogler, 2008: 402). This is because its internal actorness does not always translate into external effectiveness (Carbone, 2015:1). In evaluating the EU’s actorness in aid effectiveness, much of the empirical work has been focused on recipient countries, omitting donor actorness (Bretherton and Vogler, 2006; Aggestam and Johansson 2017; Barder et al, 2010; Chaban et al, 2013; Carbone, 2013b).

The literature on aid effectiveness has therefore overlooked the role the EU plays as a global donor (Carbone, 2013b:344). Moreover, Kiratli pinpoints that most research disregards the multilevel and time-variant determinants impacting development aid effectiveness (2021: 3). Research by Niemann and Bretherton has attributed this tendency to the fact that the EU’s effectiveness is difficult to assess due to the lack of a clear-cut definition which is challenging development cooperation (2013: 267; Bretherton and Vogler, 2008: 402). To tackle this issue, scholar Carbone has defined aid effectiveness as “policy goal attainment” (2014:113). He further pinpoints that to assess effectiveness in the EU’s external development policy, Sjöstedt’s (1977) theory of

Actorness should be utilized (2013b:350).

Through being the largest allocator of development assistance worldwide, the EU has been deemed by an array of scholars as a global leader in the development landscape since the 1990’s (Dearden, 2008: 187; Chaban et al, 2012: 435). Specifically, scholars have portrayed the Union as an ethical (Aggestam, 2008), normative (Manners, 2002) and civilian (Freres, 2000) donor, following the principles of good governance in its development policy through the exertion of ideational power. Its discourse is therefore aligned with the “untying” of aid towards the implementation of aid effectiveness norms (Carbone, 2014: 103).

However, others have characterized the EU’s identity as increasingly hybrid, inconsistent and exclusive, portraying it as a “ghost” (Fejerskov and Keijzer, 2013), a “fortress” (Bretherton and Vogler, 2006: 60) and a “body-builder” (Lightfoot and Kim, 2017:3) in the international negotiation fora. This advances a clear paradox in its development actorness (Aggestam and Johansson, 2017). The EU’s development objectives have therefore been criticized for not effectively tackling the structural causes of poverty (Barder et al., 2013:848). Since the EU is both a “problem-solving” and a “bargaining” donor that is driven by a policy of “cooperative exchange”, this plagues its actorness from “effective multilateralism” to “selective multilateralism” (Smith, 2013:18). Increased EU actorness has consequently resulted in reduced aid effectiveness in recent years (Niemann and Bretherton, 2013:271).

Within the literature, there are internal factors hampering the EU’s Constructivist “logic of effectiveness” (Aggestam and Johansson, 2017: 1204; Fejerskov, 2013: 5). Barder et al. argue that the EU does not act unilaterally, as its effectiveness is impeded by member state interests (2010: 33). Specifically, the foreign aid agenda of Central EU

states tends to be focused on ideologically aligned countries that pursue mutual trade partnerships (Klingebiel et al, 2016: 145). Southern states manoeuvre their aid allocation strategy towards “near abroad” policies (Mold and Page, 2007: 19). On the other hand, Northern members are frontrunners in the politics of untied aid and are consistently above the 0.7 UN target, deemed as “moral superpowers” in the development assistance discourse (Vázquez, 2015: 311; Dahl, 2006:898). This differentiation in aid allocation motives is constraining the EU’s normative identity (Elgström and Jönsson, 2000:68; Elgström, 2000:459).

Consequently, within the Union’s foreign policy panoply, development objectives tend to be deprioritized (Mold and Page, 2007: 16). This results in aid selectivity and a lack of cooperation, which is weakening the EU’s external actorness (Carbone, 2014: 105). To combat these diverging interests amongst EU members and ensure the “Europeanization” of its development policy, the Commission monitors aid provision underlining the need for “policy isomorphism” (Carbone, 2007: 48; Wong, 2005:138; Delputte etal, 2016: 74). To gain legitimacy in its policy actorness in development governance, the EU needs to reassert its external effectiveness role to tackle these challenges (Aggestam and Johansson, 2017:1217).

2.4. Summary

Overall, the picture of the EU’s role in development cooperation is an extremely complex one. From the reviewed literature it can be concluded that the EU’s development actorness discourse is understudied, despite the academic significance of aid effectiveness for the field of European Affairs (Arts et al, 2004: 3). The theoretical framework of Actorness based on Social Constructivism and Role Theory is perceived within the scholarship as a meaningful way of mapping the EU’s external relations and opens the floor for extensive empirical investigation of its effectiveness in the post-Cotonou (2000-2020) development cooperation landscape (Niemann and Bretherton, 2013: 262). Therefore, this thesis aims to fill this gap within the literature through offering a current and empirical perspective to assessing the EU’s effectiveness as a development actor.

3. Methods: Measuring EU Aid Effectiveness in

Development Cooperation

The following section will outline the methodological framework of the thesis. Initially, the ontological and epistemological premises of the research will be presented, followed by a detailed outline of the research design and variables. It will proceed by presenting an overview of the means of data collection and the material that will be used. Finally, the two methods to process the data on the EU’s development actorness, namely discourse and content analysis will be explained in addition to the study’s strengths and limitations.

3.1. Ontology and Epistemology

Since the 1990s, the field of European Affairs has witnessed a “constructivist turn” in its methodological premises (Rosamond, 2015: 24, Appendix C). The unit of analysis in Constructivist research is that of ideology, embedded into the hypothetico-deductive research model (Lysggaarde, 2019: 5). Therefore, a deductive and theory-testing approach will be pursued (Lamont, 2015: 44). What is more, most research on the EU has thus far focused on meta-theory, however marginal on empirically testable hypotheses, which has led to methodological inadequacy in the field, indicating the need for clear operationalization of variables in Constructivist research designs (ibid:31).

Considering this, this research design will be utilizing the Actorness Framework informed by Social Constructivism to evaluate the EU’s development aid policy in the post-Cotonou international aid architecture. The ontological grounds of this research are Constructivist, indicating that the EU’s policy-making epistemology is constitutive and relative, influenced by norms in external relations (Lamont, 2015: 23). The aim is to investigate the effectiveness of the EU as a global actor in development aid policymaking (Saltnes, 2019: 530). Such normative research designs follow the interpretivist means of “hermeneutics” to explore effectiveness over time in social contexts and are situated within the premises of Critical Social Theory (Manners, 2015: 229).

Nevertheless, the measurement of the overall effectiveness of the EU’s development policy possesses a key methodological difficulty, as it is difficult to isolate confounding variables from the research (ibid). Hence, analysing aid effectiveness requires a

multi-causal perspective through a longitudinal analysis and process-tracing (Orbie and Carbone, 2016: 6). In this process, methodological pluralism is required in investigating the EU’s external relations (Hill and Smith, 2005:7).

3.2. Variables and Normative Research Design: Longitudinal

Case Study Research

Since the EU’s actorness in global development governance is an issue requiring macro-analysis, this research design will adopt a longitudinal Single-N Case Study approach, as it combines empirical rigour and theoretical richness allowing for an in-depth analysis through the strategic selection of analytical periods to test the framework of Sjöstedt’s (1977) Actorness Theory (Manners, 2015: 227; Halperin and Heath, 2017: 213). The use of normative case research is common in the study of the EU within IR scholarship (Lightfoot and Kim, 2017; Carbone, 2015). Hence, the investigation of the effectiveness of the EU over a longitudinal time-period is required to illuminate policy change (Manners, 2015:228-230).

The independent variable (IV) in this design is the development cooperation regime which will be operationalized through the EU’s role and policy progress during the Cotonou Convention (Whiteman, 2004: 133). The term development cooperation refers to an “actor’s policies and how these affect the welfare of other countries’ people and economies” (Mitchell, 2021: 248). Traditional and emerging development actors are the confounding variables in this framework. The dependent variable (DV) is the aid

effectiveness of the EU as a global development actor which is defined a “policy

attainment”. To holistically investigate the EU’s effectiveness in development cooperation, a sequential exploratory mixed-methods approach will be employed, through the triangulation of two different research methods in data-processing (Manners, 2015: 232).

Specifically, the research will begin with a Discourse Historical Analysis on qualitative data to explore the EU’s engagement in post-Cotonou multilateral negotiations for effective development cooperation from the Paris Declaration (2005) and the Busan Declaration (2011). Following, a second phase of a Thematic Content Analysis will be executed, generating quantitative data relating to the EU’s commitment to aid quality within its policy documents during that post-Cotonou period, to indicate whether its

effectiveness discourse is systematic and representative. The longitudinal case study method will be employed to examine if progress has been made in the Union’s aid effectiveness discourse in the implementation of those agreements, through evaluating the fulfilment of its actorness role in the post-Cotonou development architecture.

3.3. Data Selection and Source Criticism

The process of data selection will consist of an analysis of both primary and secondary sources, in the form of EU policy documents, OECD and AidWatch reports, as well as journals articles accordingly. Primary documents will constitute the predominant source of data in the analysis as they possess high analytical usefulness in macro-level longitudinal studies for the identification of discursive categories (Lynggaard, 2019: 48). Specifically, five policies published by the European Commission will form the core of the analysis, namely the European Development Consensus (2005), the Lisbon Treaty (2009), the Agenda for Change (2011), the Global Strategy (2016) and the Updated Development Consensus (2017).

These documents were strategically selected as they constitute the cornerstones of the EU’s development policy and have a high normative impact for the for the promotion of global development goals towards poverty eradication (Elgström, 2000: 466). Furthermore, the increase in policy publications during this period signifies the importance of these policies for the EU’s development effectiveness discourse. Thus, they constitute current and empirical textual evidence of its development actorness and indicate an evolution of the EU’s policy discourse.

The advantages of utilizing policy documents are that they are “low-cost data”, indicating that they are easily accessible through official archives (Lynggaard, 2019: 51). Moreover, they are digitized which allows for quick and accurate text searches, enabling the conduction of the content analysis. Finally, they constitute an unobtrusive method of data collection which suggests that researchers are not involved in the data production process, allowing for an unbiased assessment of the existence of discursive practices within the texts (ibid: 48). Hence, a longitudinal analysis of these documents will be executed through a process of retroduction to investigate the evolution of the EU’s development aid effectiveness discourse under the impact of emerging challenges, through assessing whether its actorness has increased or decreased over the period of 2000 to 2020 (Halperin and Heath, 2017: 340).

Since a plethora of data used in the analysis will be obtained from the EU policy documents published by the EU Council and Commission, there is the risk of observer bias in their evaluation process. To counter this and achieve impartiality in the research, the findings will be complemented with the analysis of formal data obtained from 2012, 2018 and 2020 OECD evaluation reports published on the EU institutions. These reports are constantly peer-reviewed based on the DAC’s assessment criteria, which enhance their validity for the research purposes (Chianca, 2008: 42).

3.4. Qualitative Discourse Historical Analysis (DHA)

In line with Foucault’s (1972:27) definition, a discourse is conceptualized as a “limited range of possible statements promoting a limited range of meanings” (Larsen, 2018: 65). Discourse analysis has recently increased in presence as a methodological field within the EU scholarship (Lysggaarde, 2019: 3). Chiefly, it highlights how the power of intersubjective understandings can advance specific policy outcomes (ibid:9). DHA is a variant of Critical Discourse Analysis that is used as a macro-approach in Constructivist discussions of the EU’s foreign policy, putting emphasis on identity construction (Aydin-Düzgit, 2014: 358). Scholar Wodak suggests that DHA is “problem-oriented, not focused on specific linguistic items” (2001: 69). The theory and methods therefore interlink through a process of abstraction, indicating the constant movement between the theory and empirical data, while the historical context is embedded within discursive interpretation (ibid: 70). It therefore explores how textual data is entrenched into broader socio-political and historical issues, as visualized in the figure below (Resigl and Wodak, 2017: 93; Figure A).

Figure A. Visual Representation of the DHA Model Application on EU Development Actorness.

Adapted from: Halperin and Heath, 2017: 341.

The case of the EU’s development aid actorness is a central to approach from a discursive perspective, as it is found to be empirically constructed as a global actor (Larsen, 2018: 67). To name a few, previous research by Mah (2015), Carbone (2013), Kinglabiel (2017) and Lightfoot and Kim (2017) have conducted a discourse analysis of the EU’s development actorness to evaluate its effectiveness. Similarly, this paper will employ a Discourse Historical Analysis (DHA) to explore the language and meaning behind the EU’s policy documents, established through its pursuit to become a global leader in the global development governance discourse.

Additionally, time is a crucial factor in DHA for understanding political outcomes, and longitudinal studies provide the grounds for temporal comparison (Lynggaard, 2019:31). Since discourses are characterized by continuity and change, it is essential to specify the temporal dimension of this research design, which will be the 2000-2020 negotiation period towards the implementation of the Cotonou Convention (ibid: 32). The Theory of Actorness will be used as the analytical framework to examine the cases in which the EU possesses the ability to exert global leadership through utilizing Brattberg and Rhinard’s (2012: 564) four actorness criteria that are operationalized below, to evaluate the EU’s fulfilment of those criteria (Table A).

Table A. Actorness Criteria for DHA. Actorness Criteria Operationalization Sub-indicators Hypothesized impact on effectivness

1. Context Favourable structural conditions

Recognition, Opportunity, Authority

Are there favourable

structural conditions for the EU to act?

2. Capability Ability to mobilize instruments towards policy goals

Instruments, Negotiations

Does the EU utilise practical instruments in development effectiveness negotiations? 3. Coherence Aligned policy priorities

in efforts to project influence Values, Preferences, Procedures, Policies

Does the EU display aligned values, procedures, and policy outputs?

4. Consistency Making uniform

commitments between its policy discourse and practice

Legitimacy, Aid quality

Does the EU carry out its commitments in an aligned fashion within its policy documents?

Adapted form: Brattberg and Rhinard, 2012: 564.

The above common themes will be investigated within the EU’s policy discourse to investigate the impact of development aid negotiations on its actorness. These themes are operationalized according to the language that is used to fulfil the “context, capability, coherence and consistency” criteria respectively amongst the policy documents. This will be executed through the objective of measuring its progress and policy changes in through evaluating its empirical implementation of the actorness criteria within its discourse. Thus, a detailed analysis of the policy documents will be executed to shed light upon how meanings of the actorness discourse are promoted within the EU’s development policy (Larsen, 2018: 65). The intersubjective understandings of EU actorness will be explored through the means of process-tracing, by identifying correlations within the discourses (Lamont, 2015: 115).

3.5. Quantifying Aid Effectiveness: Thematic Content Analysis

(TCA)

Within the literature on European Constructivist analyses, there have been relatively few attempts to quantitatively measure aid quality through a dominance of qualitative over quantitative methods (Lamont: 2015 30; Mitchell, 2021:257). To counter this issue and achieve a quantitative evaluation of aid effectiveness, the DAC has launched a set of indicators to improve aid effectiveness based on the Paris and Busan Declarations for effective development cooperation (Gore, 2013: 773). Moreover, scholars Faure et al. (2015: 15) and Knack et al. (2011:1913) have engaged in longitudinal quantitative analyses on the Commitment to Development Index, which offers a holistic outlook on the EU’s development effectiveness with regards to multidimensional indicators.

Building upon this research, recent work by McKee et al (2020: 6) has constructed an updated framework for assessing aid quality of EU ODA, which combines the 2005 Paris Declaration criteria of aid effectiveness “selectivity, alignment, harmonization, results, mutual accountability” and the 2011 Busan Declaration criteria “ownership, results, inclusive partnerships, transparency”, resulting in the Aid Quality Index constructed to quantitatively assess the effectiveness of aid in global development governance, as operationalized according to the analytical categories presented in the table below (Table B). This study’s qualitative assessment will therefore be reinforced by the secondary method of Quantitative Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) to assess the consistency variable of Actorness theory, against the Aid Quality Index.

Table B. Quality Index Coding Manual for TCA of Actorness consistency variable. Coding Criteria Operationalization

Sub-Variable

Indicator

1. Prioritization Are countries and channels selected for effectiveness?

Harmonization Aid allocation to “aid orphans” against “aid darlings” (recipients under-aided or over-under-aided by EU)

2. Ownership Is there evidence of partner-country ownership and use of national systems? Alignment with development objectives Reliability and predictability EU’s future aid plans

3. Transparency Does transparency form the basis of mutual accountability? Accountability Timeliness of published information and “untied aid” (altruistic aid provision)

4. Learning How strong are the evaluation systems?

Focus on results Quality of evaluation systems planned with recipients.

Source: McKee et al., 2020:6.

TCA utilizes statistical analysis through measuring occurrence frequency of word categories across specific texts (Lynggaard, 2019: 57). It constitutes one of the most common approaches to quantitative analysis (Bryman, 2012: 578). The criteria outlined in Table B will therefore be applied to the five policy documents outlined in section 3.3, to evaluate the EU’s aid effectiveness under the actorness consistency criterion.

The TCA coding manual will be theoretically driven, as Social Constructivism constitutes the background for operationalisation of the Aid Quality indicators, which will then be empirically explored through process-tracing (ibid: 58). The aid quality key words will be processed thematically according to the operationalizations that are defined in Table B. Only the word occurrences that are relevant to the research purposes will be investigated to avoid divergence from the research focus. Following, a coding of the numerical frequency of the criteria appearing in the policy corpus will be conducted, constructing a statistical bar graph based on the results, to visualize and compare which criteria understandings appear the most and unveil the specific areas of the EU’s effectiveness in development cooperation, to understand whether its actorness has increased or decreased across this period (Lamont, 2015: 89).

3.6. Strengths and Limitations

Following, research reflexivity will be acknowledged for the execution of this case study. This research project will be employing a triangulation of quantitative and qualitative methods, which enhances the validity and reliability of the thesis. However, a correlation and not a causation will be sought between the EU’s actorness and aid effectiveness in development governance. Considering the complementarity of these two approaches in this research synthesis, the thesis aims to offer a holistic analysis of the EU’s effectiveness (Lamont, 2015: 119).

On the qualitative level, DHA constitutes a flexible approach to the evaluation of language in social science, since policy documents are commonly used within the field (Bryman, 2012: 539). The drawbacks of the qualitative data used is that it is not as reliable as quantitative. Specifically, data processing will be time-consuming thick data is generated, which is rich in scope however lacks the accuracy of thin data. This can result in the “Heisenberg effect” due to the danger of “interpellation”, a discursive process where a concept’s meaning is altered when repeated over time. Additionally, there is the risk of “path-dependency” when analysing past institutionalised development policy discourses of the EU (Lynggaard, 2019:68). Path-dependency constitutes a process of resistance to political change that has an “excluding effect” on DHA, which however can be tackled through the triangulation with TCA (ibid:69).

On the quantitative level, the method of TCA equips the research with descriptive statistics regarding discursive categories through common theme identification (Lynggaard, 2019: 59). Hence, it is useful for exploring correlations between the IV and the DV, as well as being an efficient illustrative tool for uncovering discursive patterns of development aid effectiveness (ibid: 58). The benefit of analysing quantitative data is that thin data is generated, which is objective and easily replicable, fostering the research grounds for “specificity, transparency and aggregation”, diminishing the risk of bias (Lamont, 2015:99; Halperin and Heath, 2017: 354).

However, a methodological drawback of TCA is that it risks being detached from policy context through oversimplifying effectiveness to certain criteria, resulting in the danger of yielding inaccurate results which are not representative and score low in ecological validity. Furthermore, the differing page length amongst the five-document corpus risks affecting the coding result frequency. Nevertheless, the empirical context provided by the triangulation of the normative foundations of DHA will supply the results

with considerable analytical depth and reliability. To counter research bias and coding errors, cross-checking will be performed amongst the documents in addition to repetitive coding trials. Regarding temporality, relatively recent journals will be used as a secondary source of data to complement the primary source of the policy documents, offering credibility to the research. This time-period is chosen strategically as the signing of the Cotonou Agreement instigated a new era in development governance, placing the eradication of extreme poverty as the primary goal, the proliferation of donors and the emergence of complex global challenges (United Nations, 2020:53).

Finally, the longitudinal case study approach adopted allows for a detailed analysis of development effectiveness and for the generalizability of findings to the broader context of the EU’s foreign policy which enhances the external validity of the research, but also risks selection bias due to the “false universalism” of the case study (Lamont, 2015: 132). However, since the chosen case of EU development policy touches upon a theoretically meaningful debate whcih is linked to many empirical contexts of external action such as trade and climate policy, it illustrates high ecological validity (Halperin and Heath, 2017: 153, 214). In the process of conducting the DHA and TCA, abductive reasoning will be employed through alternating between the empirical data and the theoretical framework, grouping the textual data into thematic categories based on the Actorness

Theory and the Aid Quality Index (Lynggaard, 2019: 57). No health or ethical

considerations are associated with the study since it is not conducted on human subjects.

4. Analysing the EU’s Aid Effectiveness in Development

Cooperation: Actorness Theory

This chapter will pursue an analysis of the effectiveness of the EU’s normative role as a global actor through the evolution of its development policy during the post-Cotonou (2000-2020) period. As the EU’s development aid effectiveness is an outcome of its external action, it is essential to consider its actorness (Carbone, 2013b: 341). Thus, Sjöstedt’s (1977) Actorness Theory will be utilized which is informed by the Social Constructivist tradition. The theoretical framework will be operationalized using the Brattberg and Rhinard’s (2012) actorness indicators of “context, capability, coherence and consistency” (Table A).

The analysis will begin by investigating the EU’s effectiveness through a Discourse

Historical Analysis reviewing its empirical policy and negotiation setting to explore the context and capability criteria, proceeding to detailed evaluation of its five policy

documents to examine its coherence in aid provision. To analyse the EU’s consistency in translating aid quality into practice within its policy documents, the assessment will be reinforced by a Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) according to McKee et al’s Aid Quality Index (2020:6). As presented in Chapter 1.3., it is hypothesised that the EU’s aid effectiveness has declined during the post-Cotonou period due to its actorness being increasingly linked to foreign policy objectives.

4.1. Context: Are there favourable structural conditions for the

EU to act?

Development aid policy represents a significant case for exploring the factors impacting the EU’s actorness context in global development cooperation, as it constitutes one of the primary pillars of its external action, together with foreign, security, and trade policy (Carbone, 2015: 6). According to Social Constructivism and Role Theory, the Union undertakes the dual role of acting both as implementer of its own development policy and as coordinator of its member states’ policies (Orbie, 2012: 68).Despite the EU being a case of a supranational institution composed of individual donor countries, it will be viewed as a unitary donor actor for the purposes of this analysis (ibid: 18).

4.1.1. The EU’s Empirical Policy Setting in Development Governance

The EU’s actorness role in development has originated since the Rome Treaty (1957) through the formation of the European Economic Community (Orbie, 2012: 18). This led to the signing of the 1975 Lomé Convention that instigated cooperation with Asian, Latin American as well as with African, Caribbean and Pacific States (ACP). Since the 1990s, the Union has established itself as an altruistic donor in its foreign aid provision, putting major focus on the needs of the developing world through exercising structural diplomacy (Krugiel, 2020: 166). However, due to the Convention’s failure to prevent economic recession in aid receiving states, the Cotonou Agreement was signed in 2000 (Holden, 2020: 106). Since then, the EU has become more attuned with this changing development context through aligning itself with the World Bank and the World Trade Organization (Michalski, 2020: 10-11).

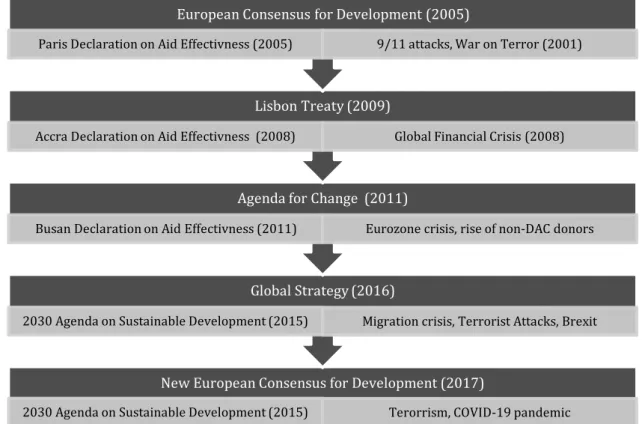

During the Cotonou period, the EU’s actorness context has markedly transformed through the emergence of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) which is situated in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) institution (Holden, 2020: 107). The meta-norm of the OECD is to monitor altruistic aid provision to increase the effectiveness of aid (ibid). Its high actorness in response to the DAC recommendations can be indicated through its increase in the publication of development policies since the early 2000s, specifically after every major aid effectiveness negotiation to enhance its effectiveness (Figure B). This suggests that it has exerted normative donor influence upon development policy through operating under the auspices of a liberal foreign policy to promote its civilian and ethical identity (Holden, 2020: 108; Smith, 2013:519).

Figure B. Evolution of EU Actorness Context in the face of Internal and External Development

Challenges during the Cotonou Convention (2000-2020).

Adapted from: Kugiel, 2020: 170.

4.1.2. The EU’s Internal Actorness Context

From the figure it can be indicated that internal challenges within the EU’s policymaking have increased since the 2008 global financial crisis, exemplified through the 2014 Eurozone crisis in Southern states such as Greece, Portugal, and Spain

New European Consensus for Development (2017)

2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development (2015) Terorrism, COVID-19 pandemic

Global Strategy (2016)

2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development (2015) Migration crisis, Terrorist Attacks, Brexit

Agenda for Change (2011)

Busan Declaration on Aid Effectivness (2011) Eurozone crisis, rise of non-DAC donors

Lisbon Treaty (2009)

Accra Declaration on Aid Effectivness (2008) Global Financial Crisis (2008)

European Consensus for Development (2005)

(Bodenstein et al., 2017: 443, Figure B). The EU’s lack of effectiveness can therefore be attributed to the fragile internal actorness context instigated by the economic crisis (Keijzer, 2011:9). Moreover, the impact of the 2016 decision for Brexit on the EU was that it reduced its actorness in implementing the 2016 Global Strategy (EUGS) as the UK was hardly engaged (Mälksoo, 2016: 375). The crisis has thus challenged the effectiveness of the Union as the UK was one of the largest contributors to its development aid (Furness et al., 2020:92). Moreover, the 2015 migration crisis has aggravated the EU’s actorness context due to uneven exposure levels to migration issues amongst its members states (Kiratli, 2021:3; Smith, 2013:24).

Additionally, EU states vary in their geographical aid actorness, with Denmark and Germany tending to focus on Africa whilst Hungary, Poland, Finland, and the Czech Republic being concerned on the Eastern Neighbourhood (Allwood, 2019: 10). Southern states tend to finance their neighbouring countries due to migration and security concerns, namely Italy assisting the Mediterranean region while Greece aiding the Balkan states (ibid). In contrast, France, UK, Belgium, and the Netherlands opt to assist their former colonies due to lingering postcolonial ties (Galvez, 2012: 5). Since collective decision-making characterizes the EU’s actorness context, this has to a “joint-decision trap”, as diverging interests amongst EU states’ bilateral aid programs have resulted in a “stalemate” in development agreements, impeding the promotion of the EU’s aid effectiveness norm due to the collective action problem (Bodenstein et al., 2017: 448; Galvez, 2012: 5).

4.1.3. The EU’s External Actorness Context

Due to the introduction of non-DAC donors in development cooperation, the EU has reduced its actorness through compromising its normative identity in aid allocation (Carbone, 2015: 13). Specifically, China is an emerging donor that is not aligned with the normative principles of the DAC and the US is reluctant to commit to the untying of aid which has aggravated development cooperation (AidWatch, 2012: 21). Moreover, the replacement of the MDGs with the SDGs in the post-2015 development agenda has favoured the EU’s actorness context in aid effectiveness through being richer in scope (Fejerskov and Keijzer, 2013: 51). However, their normative power has been denuded due being overly ambitious, curtailing the EU’s aid effectiveness (Holden, 2020: 106).

A further challenge to the EU’s effectiveness is the securitization of its development policy since the 9/11 attacks (Orbie, 2008: 82). Namely, aid is allocated geo-strategically by the EU to conflict-torn countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq, which was reflected in the 2005 ECD and later in the EUGS, through underlining that “security is a primary condition for development” (EEAS, 2013: 30). This document was published in a challenging actorness context within the EU due to being severely affected by the 2015-16 terrorist attacks in its two democratic hubs, Paris and Brussels (Figure B). Hence, development objectives were marginalized in favour of foreign policy ambitions, challenging the normative foundations of the EU’s development policy (Orbie, 2008: 82; Smith, 2013: 526). On the other hand, the Union’s increasing actorness context was unveiled in its focus on “diplomatic efforts” within the EUGS document, underlining the importance of normative power within its policy discourse (EEAS, 2016: 11, 23).

Furthermore, the 2015 migration crisis has accelerated these securitization pressures within the EU’s actorness context as an overwhelming number of refugees and asylum seekers entered its Mediterranean borders, impacting its actorness through the creation of two development policy documents during that period, namely the EUGS and the 2017 Consensus (Bodenstein et al., 2017: 443; Figure B). This led to the formation of a “development-security-migration nexus” discourse within the EU’s policy (EEAS, 2016:27; European Commission, 2017: 15). However, this resulted in the politicization of irregular migrants due to their linkage to extremist terrorism (Michalski, 2020: 19-20). Hence, the Union acted in accordance with the “logic of emergency” through “Othering” migrants, evidenced through adopting policy targeted at curbing the influx of migrants to Europe rather than viewing migration through the normative perspective of positive development (ibid: 21). This is illustrated by the fact that language used in the EUGS has become very pragmatic compared to the discourse optimism of previous policy documents, through utilizing terms such as “the European project” is “being questioned”, and “times of existential crisis” (Mälksoo, 2016: 380; EEAS, 2016: 13). Hence, the de-politicization of migration is required to increase its aid effectiveness (Fejerskov and Keijzer, 2013: 32).

Likewise, the post-2015 development challenges have resulted in aid selectivity in the EU (Michalski, 2020: 22-23). To illustrate, the OECD evaluation report has indicated that from the EU’s top ten aid recipients in 2018, five were middle-income countries, with its “primary recipient being Turkey” (OECD, 2018:11). The allocation of aid to neighbouring

states indicates that the Union is prioritizing geopolitics, underlining elements of tied aid in the EU’s actorness context (Furness et al., 2020:97; Orbie, 2008: 80-81). Most recently, the EU’s development policy has been faced with the unprecedented coronavirus pandemic in 2020, which uncovers the context criterion, through COVID-19 impacting its aid allocation levels (Furness et al., 2020:91). To exemplify, the OECD has reported that EU aid has witnessed a “historical fall” due to the crisis which is problematic (2020: 8). To enhance its effectiveness, the Union has increased its development funding through the European Investment Bank to rapidly distribute medical assistance to developing countries in response to the pandemic (Manservisi, 2020: 6).

4.1.4. Summary

Overall, the EU appears to fulfil the context criterion in its development discourse through policy document publication after every major development effectiveness negotiation and development challenge, portraying increased actorness in policy formulation (Figure B). However, the changing internal and external development context in the post-2015 framework represents an ongoing challenge to the EU’s actorness, limiting its aid effectiveness (Smith, 2013: 521). Specifically, there is a lack of internal coordination due to the EU’s collective competence, the rise of South-South cooperation and the pressing threats of terrorism, migration, the financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic which have resulted in aid stringency and ineffectiveness within the EU (Smith, 2013: 523; Galvez, 2012: 13-14).

4.2. Capability: Does the EU utilise practical

instruments in development effectiveness negotiations?

The EU is characterized as a “negotiation state”, as it increasingly utilizes negotiations as the mode of furthering its development actorness (Elgström and Jönsson, 2000: 684). Analysing the construction of the EU’s actorness capability empirically is significant for the investigation of its effectiveness as a norm-setter in development cooperation (Manners, 2002:235; Orbie, 2008:3). To achieve this, its normative role will be evaluated from the Paris (2005) to the Busan (2011) negotiations on aid effectiveness. These declarations were selected strategically as they constitute important high-level forums for enhancing effectiveness within the EU’s discourse (Orbie, 2008:19). To evaluate its actorness in these negotiations, the European Council 2008, 2009 and 2011 policy

document adopted after each respective negotiation, will be analysed as they reflect the EU’s policy priorities for aid effectiveness.

4.2.1. Paris Declaration (2005): From the Rome to the Accra Negotiations

The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD, 2005) constitutes the cornerstone of the aid effectiveness norm for twenty-first century development policy (Brown, 2020: 1236). The EU’s commitment to the Paris Declaration provided an opportunity to fulfil its leadership role through “setting an example” in its implementation of aid effectiveness principles (Dearden, 2008: 8). During the negotiations, the EU stressed for the declaration to contain more quantifiable objectives to empirically assess the fulfilment of its commitments, indicating increased actorness for aid effectiveness (ibid:9). This was also indicated in the Council document through promoting “further untying of aid going beyond existing OECD recommendations” (Council of the European Union, 2008:22). However, the EU only partially implemented the Paris Declaration due to undermining the role of recipient governments and civil society in its aid provision (Dearden, 2008:9).

The subsequent Accra Agenda for Action (OECD, 2008) negotiations attempted to clarify the Paris norms through underlining the need for inclusion of a more actors in development cooperation due to the complexity in the aid landscape. Thus, it encouraged the EU to use the Paris Declaration principles as reference points to reduce aid fragmentation (Brown, 2020: 1237). In its documents, the EU therefore pushed to further engage with “civil society and local stakeholders to ensure transparency and strengthen democratic ownership”, increasing the impact of its aid (Council of the European Union, 2008: 3). It also urged “all stakeholders to intensify the dialogue on how aid can be best delivered” (ibid: 17). Hence, the EU placed emphasized for increased accountability on both donor and recipient countries (Brown, 2020: 1237). This was achieved through pledging to adopt a “long-term perspective to their support to capacity development and to take the effects on incentives for local expertise into account”, indicating increased actorness capability since Paris (Council of the European Union, 2008:19).

Furthermore, the Union pledged to “making the EU annual reporting process, in particular on financing for development” to enhance its actorness capability in response to the financial crisis (ibid: 10). Its actorness role is also visible in the 2009 document titled “EU support to developing countries on coping with the global economic and financial crisis” as it reiterated the aid effectiveness norm through further focusing on the

“division of labour” (Council of the European Union, 2009: 2, 14; Keijzer, 2011:4). Consequently, the Paris and Accra negotiations were deemed as relatively successful negotiations for the EU, through portraying strong actorness capability in achieving consensus (Carbone, 2015: 13; Fejerskov and Keijzer, 2013: 40-41). This is further evidenced in the 2011 document which stressed that “the EU has performed above the average in implementing the Paris and Accra commitments”, suggesting increased external aid effectiveness (Council of the European Union, 2011:2).

4.2.2. The Busan Declaration (2011)

The Busan negotiations (OECD, 2011) constituted an important turning point for the aid effectiveness agenda (Lightfoot and Kim, 2017: 1). Specifically, it urged for the advancement of the multi-stakeholder Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) forum to replace the Western-dominated OECD in leading development negotiations, and the EU portrayed active support for this decision (Brown, 2020: 1231; Bodenstein et al., 2017: 444). To illustrate, the Union emphasized the need for the Busan Declaration to “take more detailed decisions on aid effectiveness governance so as avoid lengthy discussions” in the negotiations (Council of the European Union, 2011:9). What is more, the Council added that “the EU and its Member States will support more inclusive frameworks for a strengthened involvement of partner countries”, indicating that it is enhancing its capability as a global actor (ibid:23).

Despite these objectives, the EU did not outline a clear timeline for implementing the Busan priorities, in contrast to the Accra negotiations when it published its priorities early in advance, showing decreased actorness capability (Keijzer, 2011: 8). Moreover, the EU prior to Accra emphasized that “human rights, democracy and the rule of law are fundamental underlying principles for each development agreement” (Council of the European Union, 2008: 11). Nevertheless, in Busan, it lacked the willingness to endorse these principles due to continuing to follow the Paris principles in its development assistance, limiting the effectiveness of its aid (Brown, 2020: 1240; AidWatch, 2012: 21). This is evidenced through stating that it has been “less successful in transparency and predictability in its aid allocation due to increasing aid fragmentation” since Accra (Council of the European Union, 2011: 3). Hence, it portrayed reduced actorness

capability during the Busan negotiations, due to pursuing “beyond aid” policies (Carbone,

Another setback in the EU’s actorness capability to advance a clear leadership role in Busan was the internal divide amongst its members. To illustrate, states facing financial problems, namely Italy, Ireland, and Spain, adopted a critical outlook towards development cooperation (Carbone, 2015: 12). Furthermore, the EU was accused by the civil society for taking an “observer role” in aid effectiveness issues, resulting in being side-lined by major powers in the aid system, namely China and the US (ibid:12). Additionally, the emerging BRICS donors were reluctant to sign the Busan agreement as they viewed the aid effectiveness norm to be reflecting Westernized principles that were incompatible with South–South norms, deeming the OECD framework poorly adapted to the changing development landscape (Brown, 2020: 1238). This indicates that the geopolitics of aid have shifted through the multiplicity of actors which is impacting the EU’s actorness capability to reach effective agreements (Carbone, 2015:12).

Overall, the Busan agenda weakened the Paris effectiveness norms which were restated as ideals, indicated a reduced actorness capability in aid negotiations which deteriorated the EU’s external effectiveness (Brown, 2020: 1239; Carbone, 2015: 13). Moreover, the EU’s effectiveness was limited by the dominance of climate change policy negotiations during that period due to their higher geopolitical salience (Fejerskov and Keijzer, 2013: 40-41). To enhance its actorness capability in the post-Busan framework, the Council document stated that the EU should “strengthen joint programming at the country level under the leadership of partner countries wherever possible” through better utilizing aid instruments during negotiations (Carbone, 2015: 13; Council of the European Union, 2011:6).

4.2.3. Summary: The Post-Busan Negotiation Framework

On balance, the inclusive nature of the Paris and Busan negotiations has contributed to furthering the EU’s aid effectiveness norm, making it easier to expose its actorness

capability (Michalski, 2020:12). In contrast to Paris and Accra, the EU lacked sufficient

actorness in the Busan negotiations due to it its passive stance and absence of willingness for cooperation (Lightfoot and Kim, 2017:8; Keijzer, 2011:9). Its actorness has been further hampered by the increased politicization within the EU, caused by the rising bargaining power of its member states (Bodenstein et al., 2017: 444). A more effective leadership role would increase the EU’s future actorness in shaping international