Coworking spaces as

facilitators for

professional coworker

development

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business

AUTHOR: Stephanie Muth, Sven Julian Marius Rauscher JÖNKÖPING 18th May 2020

A study about coworking spaces in mid-sized cities in

Sweden

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Coworking spaces as facilitators for professional coworker development Subtitle: A study about coworking spaces in mid-sized cities in Sweden

Authors: Stephanie Muth and Sven Julian Marius Rauscher Tutor: Matthias Waldkirch

Date: 2022-05-18 Acknowledgement

We would like to thank everyone who supported us throughout the process of writing our master thesis from January till May 2020.

Very first, we would like to thank our supervisor Matthias Waldkirch for his support, his constructive feedback, and helpful advices and guidance over the past five months.

Second, we would like to thank our classmates who provided us with constructive feedback and helpful advices in the seminars.

Finally, we want to thank all participants in this study, who provided us with helpful insights and personal experience. Without them it would not have been possible to draw up the results of this study.

Stephanie Muth Sven Julian Marius Rauscher

Abstract

This master thesis investigates how independent coworkers, such as entrepreneurs and freelancers, develop their entrepreneurial competencies through social and professional interactions in a coworking space. Since its early beginnings in 2005, coworking spaces have grown to a global phenomenon. Hence, a continually increasing number of individuals work from these spaces. The reason for this is, that coworking spaces help people to feel more socially integrated and to get social and professional support. In the empirical part, this thesis focuses on coworking spaces of mid-sized cities in Sweden. By conducting a qualitative research, we identify professional developments that can be clustered in different entrepreneurial competencies. As stated in the findings, these competencies particularly develop through a combination of the following three theories: (1) experiencing a social community, (2) receiving professional knowledge, and (3) exchanging professional knowledge. In more detail, five types of entrepreneurial competencies have been found: (A) openness, (B) being socially inclined, (C) entrepreneurial thinking, (D) planning, and (E) self-selling. Professionals from 5 different coworking spaces participated in the empirical study. The findings are a result of a research method based on social constructionism with 13 qualitative, semi-structured interviews. In addition to presenting empirical findings and a conclusion, the thesis has a thorough discussion by highlighting theoretical and managerial implications, and the influence of coworking spaces for society and its potential future developments. Moreover, limitations of this study and areas for future research are outlined at the end.

Key words: CWSs, coworking, entrepreneurial competencies, social interactions, professional interactions,

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem discussion ... 3

1.3 Purpose and research question ... 4

2.

Literature Review ... 6

2.1 Background of coworking and CWSs ... 6

2.1.1 Definition of coworking ... 7

2.1.2 Definition of CWSs ... 8

2.1.3 Coworkers’ motivation to join a CWS ... 9

2.1.4 The community manager and its role for social interaction in a CWS ... 10

2.1.5 Encounter for entrepreneurs ... 11

2.1.6 Learning and knowledge collaboration ... 11

2.2 Entrepreneurial competencies used by coworkers ... 12

2.2.1 Definition and aspects of entrepreneurial competencies ... 12

2.2.2 Development of entrepreneurial competencies ... 12

2.2.3 Coworker competencies ... 14

3.

Research Method ... 15

3.1 Methodology ... 15 3.1.1 Research philosophy ... 15 3.1.2 Research approach ... 16 3.1.3 Research design ... 163.2 Data collection and sampling ... 18

3.2.1 Collecting primary data ... 18

3.2.2 Interview design ... 18

3.2.3 Population and sampling ... 19

3.3 Data analysis ... 22 3.4 Research quality ... 24 3.4.1 Credibility ... 24 3.4.2 Transferability ... 24 3.4.3 Dependability ... 25 3.4.4 Confirmability ... 25 3.4.5 Research ethics ... 26

4.

Empirical Findings ... 27

4.1 Experiencing social integration ... 27

4.1.1 Social community interactions ... 28

4.1.2 Social activity interactions ... 31

4.2 Receiving professional knowledge ... 34

4.2.1 Social support interactions ... 34

4.2.2 Professional support interactions ... 37

4.2.3 Professional activity interactions ... 39

4.3 Exchanging professional knowledge ... 40

4.3.1 Social interactions for professional knowledge exchange ... 41

4.3.2 Social interactions for professional knowledge collaboration ... 42

4.4 Entrepreneurial competencies ... 43

4.4.1 Openness ... 43

4.4.2 Being socially inclined ... 44

4.4.5 Self-selling... 48

5.

Conclusion ... 51

6.

Discussion ... 54

6.1 Theoretical implications ... 54 6.2 Managerial implications ... 56 6.3 Limitations... 596.4 Areas for future research ... 60

Figures

Figure 1 A time view of the development of work ... 6 Figure 2 Selected layers of research construction based on the framework of

Easterby-Smith et al. (2018) ... 17 Figure 3 Analysis methods - strategy (grounded theory) by Easterby-Smith et al. (2018)

... 22 Figure 4 Model for entrepreneurial competencies development ... 27 Figure 5 Interconnectedness of coworker development theories with entrepreneurial competencies ... 50

Tables

Table 1 List of interviewees participating in this research ... 21 Table 2 Grounded theory - analysis: coding process ... 23

Appendix

Appendix1 Topic guide for interviews ... 68 Appendix 2 Informed consent ... 69

1. Introduction

1.1 BackgroundModern information technologies and devices that are holistically accessible, wireless communication, and systems of data storage enabled exceptional flexibility for professionals. This can be seen when looking at how and where they decide to execute their work (Armondi & Vita, 2017; Moriset, 2013). Hence, labour has become increasingly mobile, less geographically dependent and more time contingent.

Over the last twenty years global dispersion has been observed as the novel office phenomenon, called coworking space (CWS), as noted by Akhavan et al. (2019). This observation was made in the setting of an expanded worker’s knowledge and a sharing economy that is still growing. Since the beginning of CWSs in the United States in 2005, Akhavan et al. (2019) claim that they extended throughout the entire globe. It is reported that, since 2006, the coworking society nearly doubled its scope every year (Akhavan et al., 2019). Hobson (2019) verify this notion by stating that CWSs grew in exponential form in the last 10 years. In 2007, only 14 CWSs were recorded. In the year 2017, this amount rose to 14,411 CWSs world-wide. In Sweden, one of the earliest, established CWS is called ‘Impact Hub Stockholm’ and was established in the year 2014. Other CWSs in Sweden can be found in smaller cities, such as Malmö, Lund, or Helsingborg. The coworking concept has enlarged in Sweden by numerous and distinct approaches. For instance, a trend for CWSs that are centred around real estate can be classified. Here, the motivation behind the CWS is to rent out desks primarily. However, an increased amount of CWSs ground their concept on establishing a community between professionals first (Nenonen & Lindahl, 2017).

The advent and fast extension of CWSs are mentioned by Ross & Ressia (2015) and Spinuzzi (2012). They argue that CWSs originated from aspects of interconnected nature, like technological aspects that modify the way of life, an enhanced intricacy of international business, and the rise of people’s isolation. This stays in alliance with the intention of Brad Neuberg, the founder of the first CWS. He mentioned the word ‘coworking’ for the first time and launched “an alternative office centre for non-profit cooperation in San Francisco” (Krause, 2019, p. 58). His conception fulfilled the needs of professionals operating in communities of virtual and digital nature (Krause, 2019).

Foertsch & Cagnol (2013) show in their study from Deskmag.com that 58 percent of coworkers moved from at home to working at a CWS. Hence, 84 percent of the coworkers

claim to have more social interactions, while 84 percent value “random encounters and

opportunities” and 77 percent appreciate the “sharing of information and knowledge”. Moreover,

scholars claim that a CWS is the “third space for work, learning and play” (Akhavan et al., 2019, p. 3).

According to Spinuzzi (2012), Bouncken et al. (2016) and Foertsch and Cagnol (2016), over one million workers with distinct experiences operate in collective workplaces around the world. Hence, more and more, individuals set higher preference to work independently rather than on tasks that are paid. They strive for being independent, empowered and autonomous, that can tacitly be linked to the freelancer status (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Isaac, 2016).

This goes even further, as indicated by the Global Coworking Survey. In 2018, the total amount of CWS members world-wide reached 1,27 million (Global Coworking Survey cited in Tintiangko & Soriano, 2020).

Clifton and Crick (2016) note that the goal of a CWS is the combination of formal (such as functional and productive) and informal (such as social) aspects of a work surrounding. This appears to encourage a number of valuable interactions, like “opportunities for socialisation,

peer-support/mentoring, professional networking, idea/knowledge sharing and collaboration” (Brown, 2017, p.

113). Spinuzzi (2012) further explains, that the majority of professionals who work independently operated from home before paying for a coworking workplace. Back home, those individuals potentially experienced the sense of isolation, beneath other issues. Moriset (2013) explicates, that CWSs bring these isolations of entrepreneurs and freelancers to an end, that are notably appearing in digital labour.

Along with Castilho & Quandt (2017), CWSs incorporate social aspects and environmental issues. Gaining access to a CWS and its technological infrastructure brings along many advantages. For example, the ambiance, the connection with other coworkers, events, and the community for networking are the most common reasons for the usage of a CWS. A community entailing coworkers with comparable mindsets might establish collective behaviours of work, distinct capabilities, and alike life conceptualizations as stated by Capdevila (2013), Moriset (2013) and Garrett et al. (2017). This enlightens their contentment, welfare and social integration which might result in extra economic benefits, as they have improved work-life conditions. Decreasing obligations related to administration, opening great locations, and social connections that offer inspiration permit “(…) exchanging views,

learning from others, forming teams and projects [that] motivates the use of a CWS” (Bouncken &

1.2 Problem discussion

We found that recently, a lot of scholars were investigating the crucial role of CWSs. Those give independent coworkers (in the following named coworker) the feeling of social integration, which they would not have while working remotely from home. As discussed in Orel (2019b), Merkel (2019) and Akhavan et al., (2019), a lot of freelancers face social isolation while working at home. Therefore, they seek support in CWSs and want to increase collaboration among other coworkers which further leads to shared knowledge and learning, and in a higher state, builds communities and networks within the CWS (Brown, 2017; Merkel, 2019).

References for social benefits of coworking can be seen in many scientific papers, for example, there are aspects like having less distractions (de Peuter et al., 2017), or a better work-leisure balance (Orel, 2019a). More aspects include combating social isolation (Spinuzzi, 2012), or receiving social support (Gerdenitsch et al., 2016). Other scholars highlight the importance of community building in CWSs (Capdevila, 2014), knowledge exchange processes in CWSs (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019) or solidarity and knowledge sharing that arise by social support and trust between coworkers in CWSs (Bianchi et al., 2018). According to Cremin (2003), coworkers need to develop and establish entrepreneurial skills and a mindset for self-branding in order to acquire customers in an entrepreneurial landscape. Furthermore, Bouncken and Reuschl (2018) found that there is a gap in the literature of how social and professional interactions in CWSs lead to self-efficacy among coworkers and that future studies should investigate on that. The identified research gap of Bouncken & Reuschl (2018) motivated us to dedicate our empirical study to this topic. To the best of our knowledge, no scientific research has investigated how the combination of social and professional interactions in a CWS may lead to improving coworkers’ entrepreneurial competencies. We found that Bouncken and Aslam (2019) come closest to this in providing empirical research on knowledge sharing in CWSs in their model. They state that “the synergies within CWSs help to (…) facilitate mutual learning and knowledge sharing among

diverse users working in various domains” (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019, p. 2072). The aspects

mentioned in the model were a major inspiration to our topic of interest. It provided us with many aspects that mayenhance the development of professional competencies of coworkers by social and professional interactions.

Further, we found that scientific papers highlight the importance of the Entrepreneurial Competencies framework (EntreComp) for Entrepreneurial Education, as can be seen in the

paper of Bacigalupo et al. (2016). Additionally, we found another source for 12 entrepreneurial competencies in the article of Kyndt & Baert (2015). Lastly, Lindner (2018) highlights that, entrepreneurial education may generate and support the procedure to build entrepreneurial competencies.

1.3 Purpose and research question

We build on the notion that was highlighted before by Bouncken & Reuschl (2018) that shows, how social and professional interactions in CWSs can lead to self-efficacy among coworkers. We transfer this into our own purpose, thus the goal of our study is to examine, how independent coworkers can develop themselves professionally. In addition, we want to display their entrepreneurial competencies by working in CWSs that encourage social and professional interactions. Hereby, the focus of our study is set on mid-sized Swedish cities. By doing so, we aim to add on other current research in the field of CWSs, that has mainly examined social support or benefits, that coworkers in a CWS receive, to have an increased well-being and a feeling of social integration. This may happen, for example, by working next to other motivated and open-minded coworkers. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, current literature about CWSs does not cover any notion on what kind of entrepreneurial competencies are visible among coworkers in CWSs, nor how they may be developed in a CWS. To shed light on this, we aim to demonstrate, how social and professional interactions can facilitate each of a coworker’s development, leading to the enhancement of their entrepreneurial success.

For example, certain social activities that bring along social interactions, are aimed to be explored. This may include random social conversations between coworkers, meetings, or gatherings, such as after-work events, breakfast meetings, coffee and fika breaks (a special kind of coffee break practiced in Sweden), or different kind of games, that either take place in public spaces of the CWS, or outside of it. Here, we are mainly interested in exploring, whether those social activities provide aspects for the development of professional competencies, in addition to the already more investigated improvement of social skills. Moreover, we want to study if social support, provided by other coworkers in case of issues or problems related to the work of a coworker, can add up to their professional growth. Moreover, another goal of our study is to find out if coworkers are offered professional support, provided by business professionals, and what kind of professional support they receive to improve professionally. We intend to take notion on typical forms of interactions and activities for business purposes: business trainings, seminars, webinars, mentoring,

workshops, or lectures. These activities are being provided by business experts and organised by the host of the CWS, or its community manager. In addition to this, we take professional networking activities into account, such as mingle events, that take place outside of the CWS, but are organised by the CWS.

Lastly, the aim of this thesis is to show to what extent coworkers are interested in exchanging information between each other, and how they could enhance professional and entrepreneurial progress by doing so. Here, we want to add knowledge to the scientific paper provided by Bouncken & Aslam (2019).

As a result, we developed our research question in the following way:

How do independent coworkers develop their entrepreneurial competencies through professional and social interactions in a CWS?

2. Literature Review

2.1 Background of coworking and CWSs

In 2005, the first CWS called ’Spiral Muse’ opened its doors in San Francisco to be the first mover in the market and to give self-employed professionals as well as freelancers a place to work. Until that time, only ‘unsocial’ business centres existed which were not a very good alternative beside the option to work from home. The opening of the first CWS happened only three years before the economic crisis of 2008, and thus, before the speed for the proliferation of CWSs picked up (Foertsch & Cagnol, 2013; Merkel, 2015).

This movement was a result of a long growing process of virtualisation for more than two decades. The virtualisation of work started in the early 1990s, when the idea of personal computers in private households began to develop. The first move was then followed by a second wave during the 2000s when mobile technologies became common to use in companies and for work and thus, employees were able to work remotely from anywhere at anytime. Besides, the virtualisation of work was brought to a next level with the movement of CWSs. More and more workers started a remote job due to the fact of having more freedom and flexibility for when and where to work. Hence, the need for new working places outside of traditional offices or from home was born (see Figure 1) (Johns & Gratton, 2013; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Isaac, 2016).

According to Moriset (2013) with the fast expansion of CWSs, the question arises of how, when and where work takes place in the future. Hence, coworking occurred due to two interconnected trends, first the development of the knowledge economy and second, the replacement of physical capital by cognitive capital.

Furthermore, the so-called “open source community approach to work” was born. This reflects one of the key characteristics of coworking, particularly the establishment of a social community between the coworking members to foster collaborative practice.

Figure 1 A time view of the development of work

1990th

Telework &

personal

computer wave

e ar ly 20 00 sMobile

technologies &

remote work

from 20 05 onCoworking in

coworking

Spaces

2.1.1 Definition of coworking

The occurrence of coworking combined the two different ways of work, that existed until then: the ‘standard’ work-life of a traditional office job limited to a company environment and the independent work-life of a freelancer and entrepreneurs, characterised to be free and independent but also isolated while working at home. Thus, coworking brought those two ways of work together, where coworkers work individually for themselves, yet together in a shared office (Gandini, 2015).

In this thesis, we are using the term coworker regarding to individuals in CWSs. This stays in contrast to co-workers who are professionals working closely together with each other at the same part of work as described by Fost (2008).

In 2013, coworking had developed to more than 2,498 spaces world-wide with a trend of further growth. Hence, coworking had become a worldwide phenomenon, where local roots were strengthened, while creativity of urban areas increasingly emerged (Moriset, 2013). As Johns & Gratton (2013) stated, CWSs are the same for knowledge work as what bike-share programs are for transportation. Namely, a solution based on a community, eco-friendliness, convenience, and low costs.

This led coworking to become well established and embedded in different innovation-driven businesses (Capdevila, 2013). Thus, coworking implies a new form of organizing work that enables opportunities for collaboration and encourages different workers to gather within a shared place to build a new community (Johns & Gratton, 2013).

Two years later, Merkel (2015) observed that the growth of coworking is going more towards a decentralized and highly dynamic global movement. This movement brought along a collaboration between coworkers and coworking hosts to discuss and further develop coworking. Hence, the nature of coworking unifies people in a way that it facilitates solidarity and collaboration amongst each other.

This new way of work has led people to transform the way how they organise their work and how to collaborate between each other. Further, it resulted in a disruption of classic work organisation models and fostered autonomy and empowerment of workers (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Isaac, 2016). Furthermore, Bouncken and Reuschl (2018) stated that coworking is characterised by social interaction and flexibility which foster coworkers’ creativity, knowledge exchange and development amongst each other.

To conclude, according to what we found in the literature about coworking, we decided to define our own definition of coworking for the purpose of this thesis: Coworking is a

independent coworkers who favour autonomy and flexibility in their work a frame for their work setting. Further, it provides an environment of like-minded people who seek social interaction to build solidarity and a community. The outcome is to strengthen collaboration and knowledge exchange between coworkers, which fosters their professional development. 2.1.2 Definition of CWSs

The development of information and communication technology (ICT) fostered a steady increase of remote workers, freelancers and coworkers (Spinuzzi, 2012). Hence, a new form of urban socio-material infrastructure developed and aimed to facilitate and coordinate an alternative to organise community-based labour (Merkel, 2015). Another reason why CWSs succeeded with their business model is the irony of working anywhere. A reason for this is that not any place is designed for people to work. Essential equipment, such as stable wi-fi connections or basic office equipment, is often missing (Jackson, 2014). Hence, at the beginning, coffee shops were used by coworkers, but as soon as CWSs developed, these spaces became preferred workplaces for lot of remote workers (Merkel, 2015a).

Thus, CWS is defined as a shared workplace, where different kinds of professionals, mainly freelancers, from various backgrounds and fields of specialisation come and work together (Gandini, 2015). This definition is used for the purpose of this master thesis to investigate how these environments foster the development of the coworkers.

The five core values of coworking, named community, openness, collaboration, sustainability, and accessibility (Moriset, 2013; Merkel, 2015) form the basis of a ‘collaborative approach’ and build the foundation of the five characteristics on which CWSs are built on: access to information, knowledge, resources, social capital and opportunities for random encounters. In the following, we will see, how CWSs foster these characteristics to provide a valuable environment for their coworkers.

Nowadays, two thirds of knowledge work take place in non-traditional working environments. Thus, CWSs have become important places to foster such knowledge exchanging environments (Waber et al., 2014). According to Castilho & Quandt (2017) a CWS fosters a business ecosystem, that provides the opportunity for knowledge exchange and sharing, as well as for different learning practices. Furthermore, these ecosystems can lead to business, product, or service innovation.

Spinuzzi (2012) argue, that the aim of CWSs is to bring the formal and informal aspects of work together. These are reflected in professional and functional, as well as social aspects which, when combined, encourage valuable interactions. Moreover, the physical proximity

and design of a CWS has an impact on its coworkers and their interaction (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019). Thus, CWSs are great alternatives for coworkers, as these places offer interaction with other coworkers while providing all kinds of necessary infrastructure of an office and usually include some cafeteria or kitchen area (Orel, 2019a). Hence, an open space plan with the arrangement of tables and community spaces such as a kitchen area are important to allow eye contact and to foster personal interactions between coworkers (Merkel, 2015). Hence, these environments foster a side-by-side working with other professionals and therefore strengthen daily routines and work performance (Gandini, 2015). This also strengthens the willingness and motivation of their users to share resources and work side-by-side with other coworkers (Spinuzzi, 2012).

Furthermore, events and social activities promote networking possibilities and nurture contact initiation. Consequently, the main achievement of a CWS is to form its own community, where all members of the space engage with each other (Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018).

Finally, CWSs offer a fixed environment for flexible and mobile workers, who do not have a permanent working environment of an office. This new form of shared office places offers coworkers the possibility to rent out an office desk for a short period of time. These short rental contracts, varying from daily to monthly rentals, give coworkers much more flexibility than they would have with a regular office rental contract (Merkel, 2015) and is providing them with all necessary office equipment for their daily work (Gandini, 2015).

2.1.3 Coworkers’ motivation to join a CWS

From the social point of view, coworking has become the Airbnb for sharing the same workplace and thus, combines the triangulation of cultural, social and economic motivation (Merkel, 2015).

The interaction in CWSs takes different forms. Spinuzzi (2012) claims that some coworkers simply want to have a workplace and just work alongside each other, while others engage with each other to give and receive feedback, collaborate, share ideas, and join networking events. Being stuck in social isolation while working at home fuels the need of many coworkers to meet like-minded people, who deal with the same challenges, such as access to knowledge and acknowledgement of their work as well as increasing one’s professional network (Merkel, 2015). As Garrett et al. (2017) point out, one of the main interests of a coworker is to create a strong social environment with a sense of belonging. Therefore, a main function of the CWS is to enhance social interactions (Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018) and

to foster an open and honest atmosphere which helps coworkers to engage and exchange with each other on a basis of trust (Merkel, 2015).

Beside the social aspect, CWSs have another quality which makes them interesting for coworkers. Akhavan et al (2019) present CWSs as well-equipped with essential technological infrastructure. Equipment such as whiteboards, conference rooms and open spaces encourage communication and collaboration among their users (Merkel, 2015) and give a lot of coworkers the freedom to work outside regular working hours (Akhavan et al., 2019). Hence, we claim that CWSs provide all the necessary infrastructure for entrepreneurs, freelancers and start-ups who usually do not have the money for it.

2.1.4 The community manager and its role for social interaction in a CWS

The shared office environment of a CWS offers opportunities for coworkers to socialise and to find social interaction with other coworkers (Gerdenitsch et al., 2016). This also reflects a statement of WeWorkLabs, which describes itself as a place for social and physical network for coworkers (Merkel, 2015).

Although CWSs offer all the necessary equipment of a ‘plug and play’ environment, this does not necessarily promote engagement between the coworkers and foster community building, as most of the coworking hosts claim. Hence, they state that only providing the space with a shared context is not enough to foster engagement and community building (Spinuzzi, 2012), because the two components of trust and collaboration do not develop incidentally. Moreover, the fact of just ‘being there’ is not enough to create a community with shared values (Merkel, 2015).

Therefore, hosts have to take actions and proactively foster collaboration and trust between the coworkers. As many coworkers are looking for social interaction when they operate at a CWS, it is helpful to receive the support of a host or community manager to connect with other coworkers to build trust and collaboration (Tremblay & Scaillerez, 2020).

Usually, the host is the founder and manager of the CWS and therefore responsible to live the values of the CWS in its daily actions and to give the CWS its own identity by taking care of the coworkers (Merkel, 2015).

Beside the hosts, a community manager can have a vast impact on the social interaction within a CWS. Beside the hosts, a community manager can have a vast impact on the social interaction within a CWS. This person fosters encounters between coworkers and acts as a matchmaker to bring workers together and takes the lead role in organising networking and social events, in order to bring like-minded people together (Tremblay & Scaillerez, 2020).

Furthermore, the community manager encourages knowledge exchange, and learning, and helps their coworkers to find the right connections for their field of interest (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019).

As reported by Merkel (2015), many hosts explored that eating together works as an effective method for socialising. Therefore, many hosts organise regularly common events such as breakfast or lunch together, which is then used to introduce new members or to discuss projects (Merkel, 2019).

2.1.5 Encounter for entrepreneurs

A lot of professionals from different backgrounds come together in a CWS, as they are known to be places for random encounters (Merkel, 2015). In consequence, this also raises the interest of business people and entrepreneurs to come to a CWS, as they have the possibility to access a network of professionals with different backgrounds, skills, and knowledge. Hence, the socialisation culture of a CWS encourages professionals such as freelancers, entrepreneurs, or remote workers to engage and exchange knowledge and ideas with each other (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019).

Entrepreneurs receive helpful innovation ideas and advices from other coworkers and take advantages from the received knowledge which leads to the contribution of personal and business development. Thus, CWSs foster encounters between professionals and entrepreneurs which benefits both sides. Coworkers find solutions for their work challenges and entrepreneurs benefit from the interaction and the knowledge of the coworkers (Tremblay & Scaillerez, 2020).

2.1.6 Learning and knowledge collaboration

The environment of CWSs encourages coworkers, such as entrepreneurs and freelancers to engage in knowledge collaboration with each other and to exchange ideas (Bouncken & Aslam, 2019). These knowledge collaborations benefit both sides, one independent coworker may receive help and assistance, while another one may access a pool of knowledge and experience that help to find solutions that contribute to their business development. One way how this knowledge collaboration takes place is through events organised by the community manager (Tremblay & Scaillerez, 2020) or through common lunch breaks where members of the CWS can discuss their projects (Merkel, 2019). Moreover, the open architectural structure of lots of CWSs fosters an open and easy exchange and facilitates a self-directed interaction between coworkers (Bouncken, Aslam & Qiu, 2020).

Bouncken et al. (2016) state that learning is dependent from the social environment and thus, is highly influenced by the actors, groups, or individuals around. Hence, the community aspect within a CWS has a high influence on the willingness for knowledge exchange as well as work satisfaction of its members (Bouncken et al., 2020). Therefore, CWSs can support learning through organising seminars, trainings and workshops. These events offer immediate learning opportunities about latest technology trends, innovation processes, business models and techniques, as well as promote network building ( Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018; Bouncken & Aslam, 2019). Hence, they facilitate peer-to-peer learning and take specific needs and requests of their coworkers into consideration while planning the events. 2.2 Entrepreneurial competencies used by coworkers

2.2.1 Definition and aspects of entrepreneurial competencies

One of the early explanation of entrepreneurship competencies by Bird (1995) describes them as fundamental elements like general and explicit knowledge, motivations, traits, self-perceptions, skills, and social roles. Those competencies support the start, persistence, or expansion of a company (Man et al., 2002) and allow people to operate in a successful manner (Mitchelmore & Rowley, 2010). Later on, this explanation was developed further by different researchers who claim that those competencies are modifiable, achievable and learnable by knowledge, coaching, and instructing (Man et al., 2002; Volery et al., 2015; Wagener et al., 2010) and that entrepreneurial competencies demonstrate a pattern of characteristics related to prosperous development of a business. Hence, competencies include particular skills and expertise, as well as personal motivation and individual traits (Olien & Wetenhall, 2013 cited in Gustomo et al., 2019). After summarizing the different explanations and definitions about entrepreneurship competencies from the literature, we decided on the following working definition for this thesis: Entrepreneurial competencies refer to a set of skills, characteristics, motivations and personality traits, that can be acquired through learning, knowledge exchange and experience, as well as having the mindset for constant development. Entrepreneurial competencies are extremely valuable to thrive as an independent coworker in the setting of a CWS.

2.2.2 Development of entrepreneurial competencies

Entrepreneurs maintain the economic vibrance through applying novel ideas and as Lindner (2018) states further, entrepreneurial competencies are fundamental for a functioning economy and a vivid society to overcome individual life challenges. For this reason, society

demands for individuals with entrepreneurial competencies. Those competencies include being ready for calculated risk-taking, an enhanced self-esteem, developing solutions for problems, or being responsible for personal instances. Hazlina Ahmad et al. (2010) continue claiming that aspects like motives, skills, and expertise are essential for a company to grow and to have success. Nwachukwu et al. (2017) even point out that competency in entrepreneurship decides on if a company is successful, or if it fails. Therefore, it is important to elaborate on how these competencies can be fostered and developed.

Gustomo et al. (2019) state that one way to develop entrepreneurial competency is through entrepreneurship education. Therefore, he refers to the European Commission who developed The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (EntreComp). The framework can be applied to different aspects of life, such as encouraging personal development, actively taking part in society, having access to the labour market, thriving a business idea and founding a start-up (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Other researchers used this framework to develop their own model of competence development. Hence, Armuña et al. (2020) utilize the Entrecomp framework as a guidance to characterize entrepreneurship education programs. Their findings account for identifying competencies whose advancement may enhance the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) entrepreneurship mentality with the help of Bacigalupo et al. (2016).Beside Armuña et al. (2020), other scholars such as Gustomo et al. (2019), Lindner (2018) and Nwachukwu et al. (2017) also refer to the EntreComp in their studies. They use this framework to additionally split factors that create competencies in entrepreneurship into attitudes, skills, and knowledge as well as to measure the concepts of

“entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial competencies, entrepreneurial leadership and firm performance”

(Nwachukwu et al., 2017, p. 3; Gustomo et al., 2019). Hence, they developed their own research approach and defined their entrepreneurial competencies based on the framework of EntreComp.

Another approach to entrepreneurial competencies has been introduced by Kyndt and Baert (2015). They highlight the importance of 12 entrepreneurial competencies in their paper. Those are: “perseverance, self-knowledge, orientation towards learning, awareness of potential returns on

investment, decisiveness, planning for the future, independence, building networks, ability to persuade, seeing opportunities, insight into the market, social & environmentally conscious conduct” (Kyndt & Baert, 2015,

p. 17). All the three papers of Bacigalupo et al. (2016), Kyndt & Baert (2015), and Lindner (2018) have been taken as an orientation for our empirical study. However, they do not form the basis of our empirical investigation.

2.2.3 Coworker competencies

To the best of our knowledge, there is no specific definition about coworker competencies in recent literature related to coworking. Until present, authors rather elaborate on other terminologies in their papers that may be set in relation to competencies. Most significantly, a lot of authors refer to developing and sharing skills through CWSs ( Bouncken & Aslam, 2019; Merkel, 2019; Orel, 2019b; Bianchi et al., 2018; Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018; de Peuter et al., 2017; Brown, 2017). Others highlight the development of expertise (Bianchi et al., 2018; Bouncken & Aslam, 2019; Orel, 2019b), or self-efficacy (Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018; Gerdenitsch et al., 2016). We could see by scanning the literature, that until now, most likely there is no existing definition in the literature yet related to coworker competencies. Thus, we decided to create our own definition: Coworkers competencies are characterised by a diverse skill set based on their experiences and backgrounds. But more importantly, they share the same attitude towards knowledge exchange and knowledge collaboration. Moreover, coworkers highlight entrepreneurial mindsets and thrive towards self-efficacy and constant improvement.

3. Research Method

3.1 Methodology3.1.1 Research philosophy

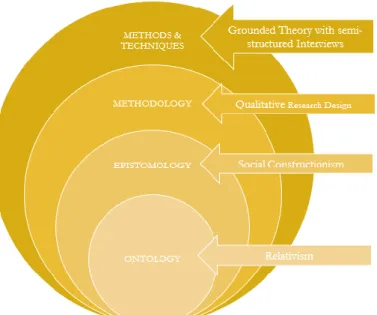

When research is conducted, the key guiding concept is new knowledge development. We described our research purpose to explore how independent coworkers develop themselves professionally while operating in CWSs, as well as what kind of entrepreneurial competencies they develop based on our theoretical research about entrepreneurial competencies. Accordingly, our decision on the research philosophy had an impact on the approach of the research and the methods utilised for empirical data collection and analysis. We defined our position of the philosophy while we conducted research. This gave us the opportunity to have a better notion on how truths function and the way we might scrutinize them.

Primarily, two comprehensive concepts exist, that we acknowledged, so that we can conceptualize the research philosophy. Those are called ontology and epistemology (Saunders & Lewis, 2012). Ontology describes the point of view about the nature of reality. In research, theories from researchers concerning beings (or reality) are examined via ontological philosophy (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). For us, it was crucial to note that CWSs and entrepreneurial competencies do not just have a single reality. This is because both concepts develop continuously and might find different interpretations in different settings. Hence, we found that a relativistic approach is a suitable fit for the ontological research philosophy. As mentioned by Easterby-Smith et al. (2015), the term relativism describes “an

ontological view that phenomena depend on the perspectives from which we observe them” (Easterby-Smith

et al., 2015, p. 825). For this reason, a debate happening between a number of involved individuals leads to a single truth, that does not negate that additional truths exist (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015).

The second layer of the research philosophy, epistemology, is described as knowledge philosophy (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015; Saunders & Lewis, 2012). In our thesis, we aimed to implement social constructionism as part of the epistemological philosophy. The standpoint of social constructionism relates to our approach of relativistic ontology, because it incorporates that social reality primarily is built through individuals exchanging interactions and experiences. Thus, distinct realities may exist, which depend on the viewer. This is because social constructionist realities are constructed on the basis of how people comprehend their environment (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015).

3.1.2 Research approach

Social constructionism implicates the emphasis of this thesis on the utilisation of a qualitative approach to collect data and to generate novel theories on social reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). Qualitative research essentially is linked to social constructionism (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015; Staller, 2013). Nevertheless, Easterby-Smith et al. (2015), additionally argue that an easy data access is not given by a qualitative approach. Hence, our duty was to pursue a procedure that is transparent and to simply explain our path of investigation towards the problem, the gathering of data, the analysis of findings, and a description of any utilised techniques and methods. Moreover, investigations of qualitative research asks for divergent data as useful knowledge streams which enable knowledge generalisation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015; Staller, 2013).

Saunders & Lewis (2012) defined two different research approaches: inductive and deductive. While using the inductive approach for this thesis, we had to be aware to base our research question on a previously defined theory. In order to do so, we conducted a comprehensive literature review about entrepreneurial competencies. Furthermore, the inductive concept allows a development of a new theory. This is because it sets an emphasis on gathered data as basis for developing knowledge by allowing data to communicate for itself. By the interpretation of empirical conclusions, inductive analysis might combine social interaction, examinations and novel theories (Staller, 2013). Hence, the induction went along with the constructionistic epistemology of this thesis by considering reality of the coworkers’ perspective.

This thesis’ data was collected by social conversations (in form of online face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews) between us and the members of CWSs in Sweden, that were willing to share their coworking experiences and developments. Induction additionally activates the issue of cautiously built knowledge which might be effortlessly argued against when contravene experience are observable (Staller, 2013). This once more conforms properly with the choices regarding epistemology and ontology.

3.1.3 Research design

As we described, we selected social constructionism as an epistemology for our thesis. This leads us further to the choice of a qualitative research design based on grounded theory. The usage of grounded theory allowed us to develop our own theory based on our research findings for independent coworker development of freelancers and entrepreneurs in the context of a CWS. Consequently, the grounded theory approach gave us the possibility to

base our study in a theoretical research first, and then test and develop our own theory throughout the analysis process of the conducted interviews. Thus, we could simultaneously explain and investigate about a coworker’s development in CWSs. Furthermore, conducting interviews allowed us to investigate how our own theory on entrepreneurial competencies developed.

However, we were aware that the decision for a research design with grounded theory also had its limitations. First, as we aimed to collect and analyse data simultaneously, we had to be aware of the influence they had on each other. Hence, it was not easy to describe all the research steps beforehand as it is an iterative process. Second, as our research was limited by time, we had to make compromises on the number of participating CWSs or conducted interviews. This had an impact on the research results. Finally, Easterby-Smith et al. (2015) states, that students may use grounded theory without being aware of different approaches of this theory. For a clear overview on the selected layers of research that we used in our master thesis, please refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2 Selected layers of research construction based on the framework of Easterby-Smith et al. (2015)

3.2 Data collection and sampling

Furthermore, using this approach provided us with a guideline for our research setup. According to Corbin & Strauss (1990), we could structure and proceed our research based on the eleven aspects of canons and procedures (Corbin & Strauss, 1990).

Corresponding to our defined topic and the detected research gap we wanted to come up with a theoretical suggestion of how coworkers, such as freelancers and entrepreneurs develop themselves socially and professionally throughout the environment of a CWS. Hence, we aimed to verify whether we could adopt aspects of entrepreneurial competencies as found in the theory and how to adapt those to the frame of our research. By doing so, we could draw our research study on the development of a theory and can derive our own research approach from it.

3.2.1 Collecting primary data

According to Tracy (2020), interviews provide different ways for mutual discovery, understanding, reflection, and explanation. Moreover, interviews unveil personal life experiences and subjective point of views of people. Hence, interviews were used by researchers to get access to information about phenomena which otherwise would have been difficult or impossible to get. Therefore, we decided to collect primary data for our study by conducting interviews, as our research aimed to explain the development of entrepreneurial competencies of coworkers in CWSs. The interviews were conducted in English.

However the native language of most of the interviewees is Swedish, which we are not confident enough with, we decided to conduct the interviews in English.

3.2.2 Interview design

To make sure that we did not have any bias in our interviews and to receive subjective answers, we decided for a semi-structured interview design by guiding our interviewees through our research topics. This helped us to stay focused on the topic, but still gave the interviewees the freedom to speak freely about their experiences and competencies. In order to guide them through the interviews, we had to prepare the frame for the interview in form of an interview guide in advance (see Appendix 1) (Tracy, 2020). By doing so, we were able to ask open-ended questions during the interview which gave us the opportunity to follow an exploratory approach (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). By using the laddering technique, we were able to investigate much more from the questions. So, during the interview we focused on “why” questions (laddering up) and asked for examples and experiences (laddering down)

the interviewees had gained (Tracy, 2020). To be able to transcribe the interviews afterwards and to focus on the interview while conducting it, we recorded the audio and video of the sessions. The interviews lasted between one hour and one and a half hours.

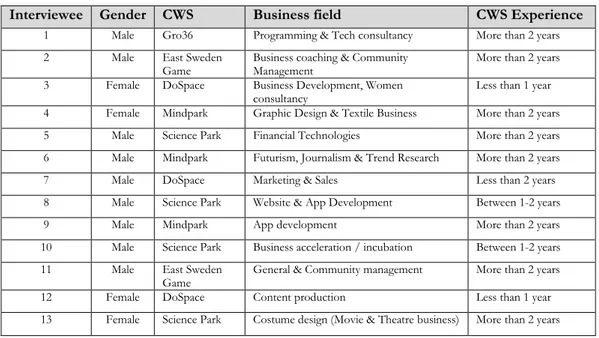

Even though face to face interviews provide the best verbal and contextual way to collect, understand and interpret data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015), we decided for online interviews with Zoom for two reasons. First, due to the global Covid-19 crisis, people were asked to stay at home and keep social distance. Second, as we had reached out to CWSs from all over south of Sweden, we received interview request from CWSs out of different regions in a relatively short time. Hence, travelling around and meeting the interviewees in person would not have been possible. Thus, online interviews with Zoom gave us the best opportunity to collect as much data as possible in just a short time frame. It also offered our interviewees much more flexibility as they could participate from home. The participants were informed in advance, that we were conducting an online video interview. Nevertheless, it was up to the interviewee to decide, whether they wanted to activate the video function or not. Lastly, we conducted the interviews individually with every coworker, as we were interested in their personal experiences and competencies. Those are both very subjective viewpoints. Therefore, any other option beside single interview was not of interest for this study. 3.2.3 Population and sampling

In accordance with Easterby-Smith et al. (2015), at first we used a purposive sampling method whose guiding concept is the theoretical sampling approach. This was done as we had a clear notion on what sample components are desirable based on the research purpose of our thesis. Consequently, we identified a number of criteria under which we were able to select, whether or not an interviewee can be taken into account. Firstly, the interviewee had to be an independent coworker. Secondly, they had to have at least six months of coworking experience to be able to adequately report about their experiences and developments. Thirdly, we researched about CWSs operating in small and mid-sized cities in Sweden. Consequently, most CWSs in those cities are not older than two to three years so far and have not been subject to major studies. Lastly, we made sure, to conduct interviews from the coworker perspective, as this is the main focus of our thesis. In order to get sufficient interview partners, we started approaching the local CWSs of Jönköping. Those are Gro36, DoSpace, Friendly Corner, and Science Park. After explaining the idea behind our master thesis to the community manager of DoSpace and asking for potential interviewees out of its community, we got invited to set up a posting with all the relevant details about the idea

behind the interview in an external document with a link to MeetingBird, an online platform where people can sign up individually for interview slots. The community manager then submitted the document for us in the community of DoSpace, which has 400 members. Our original intention was, with the success we had with DoSpace, to focus the study around this particular chain of CWSs. Also, because it has subsidiaries in other small cities in Sweden like Norrköping and Linköping. However, we raised concerns if enough coworkers would participate. Indeed, the feedback until the end was quite poor. Luckily, we were able to schedule one interview like this. To get more participating coworkers, we started an acquisition offensive, where we researched about Swedish CWSs. In an excel list, all the CWSs with relevant contact data were documented, and afterwards contacted. Additionally, the status was noted, for example, whether we were currently waiting for feedback of a community manager. The idea behind this approach was to be able to get more interviewees following the procedure we had taken at DoSpace Jönköping. Thus, we wanted to get the collaboration of those CWSs to submit our posting, which we modified for every single CWS, for their online communities to reach out to a high number of coworkers simultaneously and without the need to physically meet in those times of the Covid-19 crisis. The first official means of contact was via e-mail, so most e-mails have been sent to info e-mail addresses, some were directly addressed to community managers if the information was available on the webpage, and in some cases, contact formula have been used. However, we were right in our assumption, that also here, the feedback would not be vast and that it might need longer to get any kind of feedback than by other means of contact. For this reason, we started approaching CWSs via social media. Hence, explicit members, primarily CEOs, founders, community managers, and interns, of each CWS were contacted via LinkedIn. We also sent messages to the official pages on Instagram and Facebook. This approach is very straight-forward, as coworkers, after selecting an interview slot, automatically receive an invitation to the interview and a link to Zoom, and at the given time, all of the attendees only have to enter the online face-to-face interview via the given link. As a result, all the communication beforehand and during the interview was held digitally. In addition to this, we also reached out to Science Park Jönköping and to its Facebook community, where we were able to connect with a couple of interview partners. Also here, we were able to schedule 5 interviews, with the main part from the Science Park coworking community on Facebook. The idea behind the first two interviews was to find out, whether the selected questions of us turned out to be understandable and also to find potential adjustments. We conducted those two interviews at the beginning of our research. They helped us to identify weaknesses in our

interview guide and strengthened our questions, but we decided to not include them into the analysis as they did not fit well to our sampling strategy. In addition to the Science Park community group, we were also successful in acquiring interviewees from the Mindpark Sweden Facebook community. They were also offered to receive the results of our study after the completion of this thesis. As it turned out, some of our interviewees had signed up only for the purpose of receiving the results after the study is completed, as they are either conducting similar research in the same research field or are interested in our result for the purpose of future development of their CWS. What is more, is that two interviews were found based on direct referrals from coworkers that already had the interview with us and that met the criteria for our study. Accordingly, here we used the snowball sampling approach by Easterby-Smith et al. (2015) as a second sampling method. After receiving the contacts, we double-checked their eligibility before conducting the interview. The reason for why we chose this snowball sampling approach, is because finding independent coworkers in general turned out to be difficult. So, our plan to conduct 15 interviews was challenging, due to the current circumstances and because of time constraints. But in total, we were able to conduct 15 interviews, whereof 2 interviews were with solely employees of start-ups working in Science Park CWS. The other 13 Interviewees were either solely entrepreneurs, freelancers, or a combination of both, as can be seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1 List of interviewees participating in this research

Interviewee Gender CWS Business field CWS Experience

1 Male Gro36 Programming & Tech consultancy More than 2 years 2 Male East Sweden

Game Business coaching & Community Management More than 2 years 3 Female DoSpace Business Development, Women

consultancy Less than 1 year 4 Female Mindpark Graphic Design & Textile Business More than 2 years 5 Male Science Park Financial Technologies More than 2 years 6 Male Mindpark Futurism, Journalism & Trend Research More than 2 years 7 Male DoSpace Marketing & Sales Less than 2 years 8 Male Science Park Website & App Development Between 1-2 years 9 Male Mindpark App development More than 2 years 10 Male Science Park Business acceleration / incubation Between 1-2 years 11 Male East Sweden

Game General & Community management More than 2 years 12 Female DoSpace Content production Less than 1 year 13 Female Science Park Costume design (Movie & Theatre business) More than 2 years

3.3 Data analysis

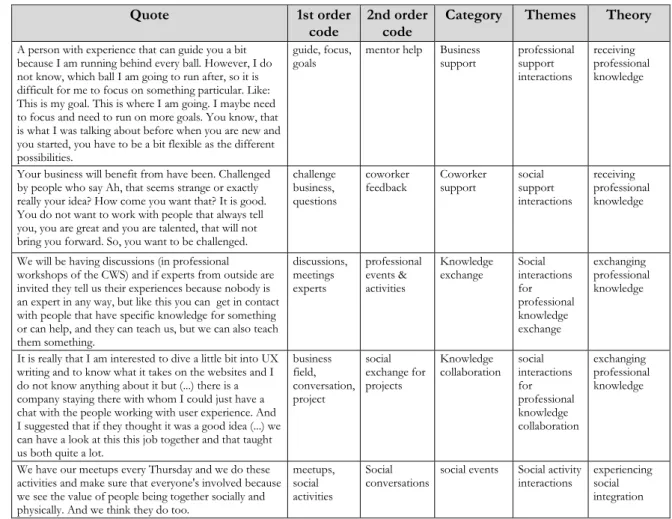

The fundamental idea of grounded theory is that data collection and analysis happen simultaneously. As the analysis started right from the beginning with the first interview, it allowed us to direct our next interviews and detect irrelevant or misguiding questions early in the process.

Therefore, we transcribed the recorded interviews in order to prepare the collected data for further analysis. The careful preparation of the data was important to ensure a complete and rich data basis which was analysed in the next step.

For the analysis we set up a concept for the codification of our data as we could not build our theory on raw data. Only by doing so, we could compare incidents and draw conclusions on same terms. This further allowed us to develop and relate the codes or concepts into categories that show similarities. By doing so, we constantly compared our coded data in order to detect similarities and differences and we hoped to achieve higher accuracy and consistency. Finally, identifying patterns and variations helped us to structure the data and allowed us to organise the categories (see Figure 3) (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Figure 3 Analysis methods – strategy (grounded theory) by Easterby-Smith et al. (2018)

To follow the approach taken in Figure 3, we firstly screened all our interview transcripts for relevant aspects related to our topic. By doing so, we highlighted suitable quotes for our

study and copied them into an Excel file to get an overview of the essential quotes from all the interviews. After completing the Excel list with the quotes, we identified descriptive codes, the so-called first order codes. These codes describe the quotes in general and sum them up in a couple of keywords. After this, we were able to establish second order codes, which are narrowed down and summed up in only one code. This is followed up by the categories, where the different kinds of second order codes have been grouped together. Like this, we were able to identify a total number of 20 categories. Then, those 20 categories were further clustered into seven themes. Ultimately, the following three theories resulted out of the themes and indicate the result of the entire coding process: (1) experiencing social integration, (2) receiving professional knowledge, and (3) exchanging professional knowledge. To be able to sort the different theories, themes, categories, and codes at the end, we implemented a filter function in Excel. Then, we ran different filters, and could identify the quotes that belong to a specific rubric. Because there were so many quotes in total, we had to focus on the most relevant quotes. Hence, only those were included in the empirical findings. For a more detailed notion on the process, please refer to Table 2. Table 2 Grounded theory – analysis: coding process

Quote 1st order

code 2nd order code Category Themes Theory A person with experience that can guide you a bit

because I am running behind every ball. However, I do not know, which ball I am going to run after, so it is difficult for me to focus on something particular. Like: This is my goal. This is where I am going. I maybe need to focus and need to run on more goals. You know, that is what I was talking about before when you are new and you started, you have to be a bit flexible as the different possibilities.

guide, focus,

goals mentor help Business support professional support interactions

receiving professional knowledge

Your business will benefit from have been. Challenged by people who say Ah, that seems strange or exactly really your idea? How come you want that? It is good. You do not want to work with people that always tell you, you are great and you are talented, that will not bring you forward. So, you want to be challenged.

challenge business, questions

coworker

feedback Coworker support social support interactions

receiving professional knowledge

We will be having discussions (in professional workshops of the CWS) and if experts from outside are invited they tell us their experiences because nobody is an expert in any way, but like this you can get in contact with people that have specific knowledge for something or can help, and they can teach us, but we can also teach them something. discussions, meetings experts professional events & activities Knowledge

exchange Social interactions for professional knowledge exchange exchanging professional knowledge

It is really that I am interested to dive a little bit into UX writing and to know what it takes on the websites and I do not know anything about it but (...) there is a company staying there with whom I could just have a chat with the people working with user experience. And I suggested that if they thought it was a good idea (...) we can have a look at this this job together and that taught us both quite a lot.

business field, conversation, project social exchange for projects Knowledge

collaboration social interactions for professional knowledge collaboration exchanging professional knowledge

We have our meetups every Thursday and we do these activities and make sure that everyone's involved because we see the value of people being together socially and

meetups, social activities

Social

conversations social events Social activity interactions experiencing social integration

3.4 Research quality

The aim of our study is to establish trustworthiness in our research and to make it visual for the reader how scientific criteria had been applied to this study. Therefore, we used to framework of Guba (1981). He defines four criteria of trustworthiness, named credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability.

However, this study was conducted in the context of a master thesis. This means that we only had a limited timeframe and scope for our research and thus, we were not able to fulfil the criteria of Guba (1981) in the way, as other researchers are able to, with less constrains and more contributing resources.

Nevertheless, it has been our honest interest to ensure the criteria of trustworthiness best possibly to our findings. Hence, we made sure to follow the criteria of trustworthiness as described by Guba (1981).

3.4.1 Credibility

In order to keep the credibility of the study, we carried out a comprehensive literature review to get familiar with our research topic and to find a research gap that we were able to close with our research. Only after doing so, we started with the data collection and analysis. The literature review together with the description of our data collection and analysis helped us to keep the focus of our research question and address it more precisely in the interviews. In order to keep the approach aligned with our research constructionism, we used different sources, and thus, applied the concept of triangulation to our research target to keep the confidence and accuracy in our research (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). By doing so, and by using different kinds of triangulation techniques, we were able to keep a neutral perspective as best as possible. During the data collection process, we conducted interviews with different coworkers who had lot of experience with CWSs, ranging from half a year up to 4 years. Nevertheless, the table of interviewee shows their time of experiences in CWSs. Furthermore, in the seminars we received helpful advices on what we had to pay attention to and what we should consider while conducting the interviews.

3.4.2 Transferability

Lincoln and Guba (1986) defined transferability as a way to apply research findings to other contexts. Usually, the used sample size of a qualitative study is not sufficient to permit a generalization of the results. Nevertheless, the aim of all researchers conducting qualitative study should be transferability of results to go beyond the limitations of the study. To do so,

a detailed description of the approach, the sampling strategy and the used methods of the data collection are a necessary part of the study. Hence, we provided a comprehensive description of all three to ensure the transferability of our study to future research. Moreover, we used primary data throughout our research process. This helped us to create our own theory and develop a better understanding of our research topic by investigating the context of a CWS and its members. Furthermore, we explained our analysis approach in detail before we started analysing the data to ensure that our analysis process was aligned with our method. During the sampling of our interviews, we followed our prior defined sampling strategy of interviewing independent coworkers, such as freelancers and entrepreneurs with minimum 6-month CWS experience of mid-sized CWSs in Sweden. This helped us to keep the frame of our research and to provide helpful insights into a new field of research.

3.4.3 Dependability

Dependability describes the extent to which other researchers can reproduce this study. The objective of dependability is to ensure that other researchers who would like to conduct the given research under the described circumstances would come up with the same results and conclusions. In order to allow this, a carefully documented process is necessary to provide all the given and necessary information for it (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). Hence, we provided all the necessary information about methodology, used methods for data collection as well as analysing techniques and presented our data. The conducted interviews were recorded, afterwards transcribed, and then coded and categorized in order to derive the results from them. It is important to mention, that our interviewees were talking about personal experience, characteristics, and competencies which needs to be considered, as therefore our data reflected subjective opinions and experiences. Hence, other researchers should be aware of this fact, as this can have a big influence and may change answers and results of future conducted research in that field.

3.4.4 Confirmability

The objectivity of results has a high importance in qualitative studies. This is achieved when the researchers keep a neutral perspective during their research (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). Hence, during the interview process we were aware that as researchers we were part of this process and thus, that we had to keep a neutral perspective as best as possible. Therefore, we guided our interviews only with a few unstructured questions to avoid any possible bias or leading them into a certain direction. At the end of our interviews, we always asked our

interviewees if they had something to add or mention to our discussed topic or if they would like to clarify something what we discussed, to make sure, that they had all necessary opportunities to express themselves. To conclude, our research findings were analysed and interpreted based on the given quotes in the interviews and thus were not influenced through a bias of us.

3.4.5 Research ethics

During a research process several different ethical issues can arise which need to be considered in advance. Therefore, we followed the key principles in research ethics introduced by Bell and Bryman (2007). By doing so, we were able to ensure that no harm came to the participants, that the dignity was respected as well as privacy and anonymity were protected, and that research data was treated fully confidential. This was only possible by fully anonymizing the data to ensure that traceability to a specific participant in the study was not possible. Furthermore, throughout the usage of an informed consent (see Appendix 2), we made sure that the participants were informed about the context of the study in advance and that we were conducting it for the purpose of our master thesis from the Jönköping International Business School, to declare the affiliation of the research and to avoid any deceptions about the nature of our research. Moreover, the interviewees were informed that their data and the content of the interviews is only used for the purpose of the study and will not be revealed to anyone outside of our master thesis seminar group. At the beginning of each interview we provided further information about the context of the research to ensure transparency and honesty in communication and asked the interviewees to confirm, whether they still want to participate in the research. Finally, while conducting the interviews we made sure to avoid misleading questions that may have caused false research findings.

4. Empirical Findings

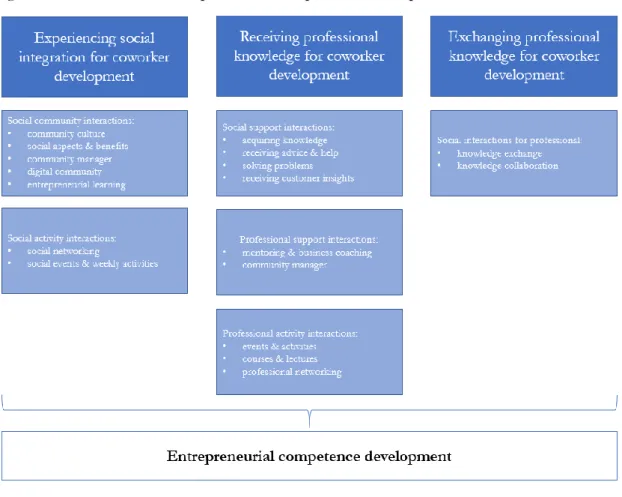

In this chapter we summarise our findings from our empirical study. After the coding of the interviews had been completed, we were able to develop the following three theories, which combine seven themes. Those seven themes combine the before defined 20 categories (the categories are not shown in the findings). For a more detailed notion of the theories and the themes, please refer to Figure 4.

Figure 4 Model for entrepreneurial competence development

4.1 Experiencing social integration

In this chapter we summarise how social interactions within the community, such as a CWS culture or a community manager foster social aspects and benefits as well as strengthen a digital community and thus lead to experiencing social integration for professional coworker development.