Trade shows from a SME

perspective

- an opportunity for internationalization?

Authors:

Helena Sigge

Sissy Viklund

Tutor:

Peter Lindelöf

Program:

Tourism programme

Subject:

Business Administration

Level and semester: Bachelor level Spring 2009

Baltic Business School

2

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this thesis was conducted at the division of Baltic Business School at Kalmar University.

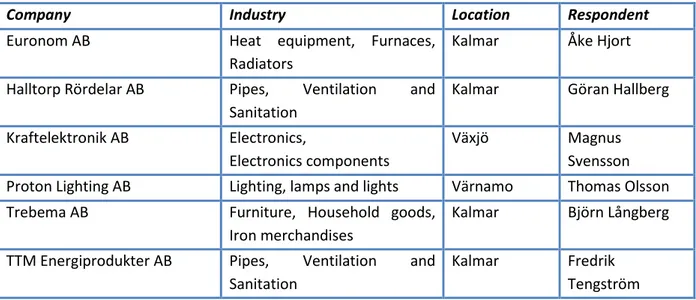

There are certain key persons that have enabled this research. First of all we would like to thank the company respondents Åke Hjort, CEO at Euronom AB; Göran Hallberg, CEO at Halltorp Rördelar AB; Magnus Svensson, District Manager at Kraftelektronik AB; Thomas Olsson, CEO at Proton Lighting AB and Björn Långberg, Export Manager at Trebema AB as well as Fredrik Tengström, Financial Manager at TTM Energiprodukter AB. All of them have been very helpful during our study.

We would also like to thank our supervisor Peter Lindelöf for his valuable opinions and guidance throughout the thesis process.

Kalmar, May 2009

3

Abstract

When SMEs have decided to internationalize their business, several different ways can be chosen to enable that process. In this research, trade shows exemplify an aid for internationalization at the same time as trade shows are portrayed as a good networking tool. Motives for participating in trade shows tend to vary; some companies see trade shows as an opportunity to launch new products and conduct sales whereas others consider trade shows as a good occasion to find new customers at the same time as they can maintain current customer relationships. Trade shows are furthermore a great opening to establish new business contacts, which consequently can provide an inroad into foreign markets. The aim with this dissertation is to analyze how SMEs use trade shows as a trigger or first step to internationalize and to investigate which role networking plays in a trade show context. Furthermore the aim of the study is to examine how SMEs’ networks affect their internationalization process. This research was carried out by conducting multiple-case studies of six companies from the region of Kalmar, Sweden. The results gained by the case studies confirmed that trade shows play an important role for SMEs when aiming to internationalize and expand the business network. Further, the case studies indicated that network connections are crucial for enabling the internationalization of SMEs.

4

List of contents

1. Introduction ... 6

1.1 Background ... 6

1.1.1 International trade shows and participation motives ... 6

1.1.2 Pre-show, at-show and post-show activities ... 7

1.1.3 Strengths and weaknesses of participation in trade shows ... 7

1.1.4 Visiting instead of exhibiting ... 8

1.2 Problem discussion ... 9

1.2.1 Trade shows as a marketing communication tool ... 9

1.2.2 Demarcations ... 10

1.3 Problem definition ... 10

1.4 Purpose ... 10

1.5 Outline of the study ... 10

2. Theoretical framework ... 12

2.1 Trade show performance: Outcome- and behavior-based control system ... 12

2.2 Motives for internationalization ... 13

2.3 The Uppsala internationalization model ... 13

2.4 The Network model ... 15

2.4.1 Four cases of internationalization ... 16

2.5 Internationalization of SMEs ... 18

2.5.1 International market selection of SMEs ... 19

3. Methodology ... 21

3.1 Research purpose ... 21

3.2 Research approach ... 21

3.3 Research strategy ... 22

3.4 Data collection method ... 23

3.4.1 Interview techniques ... 24 3.5 Sample selection... 25 3.5.1 Sample criteria ... 25 3.6 Data analysis ... 26 3.7 Research quality ... 27 3.7.1 Validity ... 27 3.7.2 Reliability ... 27 4. Empirical data ... 29 4.1 Euronom AB ... 29 4.1.1 Company background ... 29

4.1.2 The company’s trade show participation ... 29

4.1.3 Motives for trade show participation... 29

4.1.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 30

4.1.5 Internationalization ... 30

4.1.6 Networking ... 31

4.2 Halltorp Rördelar AB ... 31

4.2.1 Company background ... 31

4.2.2 Trade show participation ... 31

4.2.3 Motives for trade show participation... 31

4.2.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 32

4.2.5 Internationalization ... 32

4.2.6 Networking ... 32

4.3 Kraftelektronik AB ... 32

4.3.1 Company background ... 33

5

4.3.3 Motives for trade show participation... 33

4.3.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 33

4.3.5 Internationalization and Networking ... 34

4.4 Proton Lighting AB ... 34

4.4.1 Company background ... 34

4.4.2 Trade show participation... 34

4.4.3 Motives for trade show participation... 35

4.4.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 35

4.4.5 Internationalization ... 35

4.4.6 Networking ... 36

4.5 Trebema AB ... 36

4.5.1 Company background ... 36

4.5.2 Trade show participation... 36

4.5.3 Motives for trade show participation... 37

4.5.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 37

4.5.5 Internationalization ... 38

4.5.6 Networking ... 38

4.6 TTM Energiprodukter AB ... 38

4.6.1 Company background ... 39

4.6.2 Trade show participation... 39

4.6.3 Motives for trade show participation... 39

4.6.4 Planning and follow-up of trade shows ... 39

4.6.5 Internationalization ... 39

4.6.6 Networking ... 40

5. Discussion & conclusions ... 42

5.1 Trade show performance ... 42

5.2 Motives for participation at trade shows ... 43

5.3 Motives for internationalization ... 44

5.4 Internationalization theories in connection to the six companies ... 45

5.5 Internationalization from a trade show perspective... 46

5.6 Trade shows as a networking tool ... 47

5.7 The importance of networks ... 48

5.8 Future research suggestions ... 49

List of reference Appendix A: English interview guide Appendix B: Swedish interview guide List of figures Figure 2.1: The Uppsala model ... 14

Figure 2.2: Internationalization and the Network model ... 17

Figure 2.3: Summary of theories ... 20

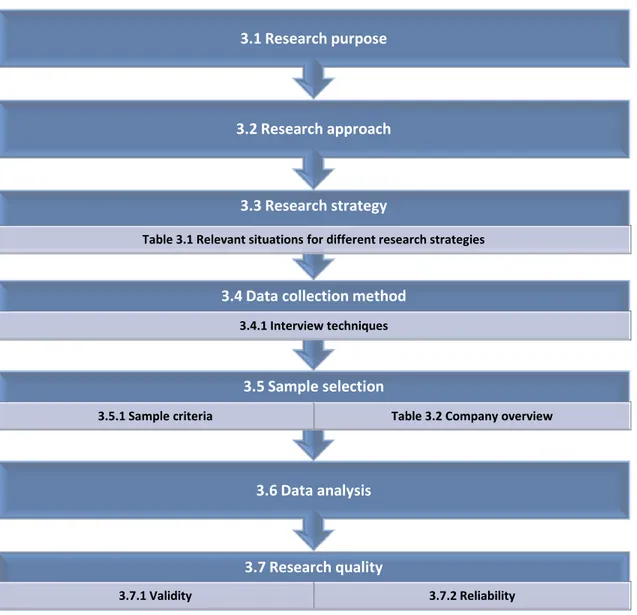

Figure 3.1: Summary of research methods ... 28

List of tables Table 3.1: Relevant situations for different research strategies ... 22

Table 3.2: Company overview ... 26

1. Introduction

In this chapter a background to our research area will be described, followed by a problem discussion. Further on, we will explain the purpose of the thesis and present the research questions connected to this. Finally we will declare the limitations made by us and conclude this chapter with an outline of the study.

1.1 Background

The history of trade shows began during the early medieval era when two major trading unions were founded in Europe; one in the southern parts of Europe and the second in the northern parts of Europe. The most common goods sold in the southern parts of Europe were jewelry, ivory, gold and textiles from the Far East, whereas in the north, trade included necessities such as fish, wool, tar, salt and iron. This new way of trade constituted the foundation for international trade shows. During the trade shows, buyers and sellers would meet for a few weeks every year to present new products but also to look at what competitors had to offer.A further reason was to exchange experiences among the traders. Since the participants of trade shows came from different countries, a special currency was needed and consequently developed (Flodhammar, 1990).

The development of the phenomenon of trade shows1 started in the Champagne region in France and has since then spread all over the world (Flodhammar, 1990). Germany can be said to be a Mecca of trade shows today, approximately 66 per cent of the world’s leading trade shows occur in Germany (Kirchgeorg et. al., 2005). One of the first German trade shows was held in Leipzig in 1165, in the beginning mainly being a marketplace, later developing into a general, industry specific exhibition. The Leipzig Show has since then been a model for many new trade shows (Alles, 1988). Research from Europe and the U.S.A. has shown that trade shows are one of the most important marketing tools for a firm. It is considered as a vastly cost-effective way of meeting many potential suppliers and buyers in a short period of time. Today the main reasons for a firm to participate in a trade show are to gather general market information and information about competitors as well as the latest technology. Visitors, on the other hand, participate for the reasons of collecting information about market opportunities, new products and potential suppliers (Ling-Yee, 2005). 1.1.1 International trade shows and participation motives

International trade shows can be seen as large industry gatherings where the main reasons for participation are to create brand awareness and increasethe firm’s image and reputation. A further reason is to build up an interest for the firm’s products on an international market (Hansen, 1999). However, as can be read in several articles, such as Seringhaus and Rosson (2004) and Evers and Knight (2008), the motives for participation in international trade shows do not differ to a great extent from the motives of participation in domestic trade shows.

According to Hansen (1995), firms participating in trade shows both have selling and buying motives. The selling motives can be divided into two types, namely selling and non-selling. The selling motives include identifying new potential customers, serving current customers, introducing and testing new products as well as actual selling. Non-selling motives, on the other hand, consist of collecting

1 According to Krirchgeorg et. al. (2005) are trade shows, trade fairs, fairs and exhibitions used as synonyms. In this thesis the term trade show will be used.

7 information about competitors, improving the firm’s image and maintaining the company’s strength (ibid). Moreover, Hollensen (2007) recognizes the building of new relationships as a non-selling motive. Buying motives can mainly be ascribed to visitors (Hansen, 1995).

Three kinds of international trade shows do exist. The first mentioned are the in-country shows that are mainly set up for domestic consumers. This type is best suited for firms that are already established in that country. Second, are the special-interest global shows; these are attracting exhibitors and attendees from all over the world no matter of its

location. Lastly, the

broader-interest trade shows attract visitors and exhibitors with very different broader-interests (Chapman, 1995). 1.1.2 Pre-show, at-show and post-show activitiesFor a firm, to get the most out of the trade show, Goldberg (2001) as well as Hansen (1995) discusses three phases. These are pre-show, at-show and post-show activities. The phases need careful planning and a lot of hard work from the firm in order for them to get the most out of the event and thereby increase the return of investment (Goldberg, 2001; Hansen, 1995).

Seringhaus and Rosson (2004) explain that an important pre-show activity is announcing the firm’s participation to current and potential new customers; this can be done via mail, fax or by telephone calls. The firm also needs to set up clear objectives about how to create awareness about the firm and their products.Another objective is to seek new or repeat sales. These objectives have to be clear in order to give the staff the right training before the event. To be able to attract visitors beforehand, firms may send out invitations, product brochures and free entry tickets. The company can moreover pronounce giveaways and advertise in industry- and trade magazines (Ibid). Stevens (2005) argues that it needs to be remembered that pre-show activities are the most important activities for attracting the right visitors to your booth.

To be successful at the trade show the firm needs to make a long-lasting impression on the visitors. Factors affecting the visitors’ impression are how the staff acts and behaves during the show but also if product demonstration is performed in an impressive manner (Hansen, 1995).

The last phase, post-show activities, concerns follow-ups on contacts made during the trade show. This process can be conducted either by phone calls or personal visits (Hansen, 1995). Follow-ups should be done within a preferably short period of time, as “hot” customers may turn into “cold” if the firm does not act fast enough. Another post-show activity is evaluating the final cost of the event, such as personnel costs, booth costs and promotion costs (Seringhaus & Rosson, 2004).

1.1.3 Strengths and weaknesses of participation in trade shows

Trade shows are seen as one of the best marketing tools for firms and has been so since the very beginning of the phenomenon. One of the strengths with participation in trade shows is that trade shows constitute a great marketplace to meet with current and potential customers. In fact, most of the visitors attracted arrive with an intention of buying new products, which in turn, leads to increased sales for the exhibiting firm (Stevens, 2005).Hollensen (2007) lists further strengths, such as trade shows being a great opportunity for a firm to display, promote and to demonstrate new products. It is important to remember that some of a firm’s products may be difficult to sell without seeing and trying them first. Moreover, are trade shows an excellent marketing tool for SMEs, as it helps them to find new business partners and build new relationships (ibid).

8 However, there are a number of weaknesses with the phenomenon. Trade shows are an expensive event that takes a lot of time and effort for the firm, both regarding the planning and executing of it. The decision on which trade show to attend can be difficult as there are a wide range to choose from (Hollensen, 2007). Additional problems involve the difficulties to measure the outcome of the event afterwards and that firms tend to put the largest amount of their trade show budget on the stand (Stevens, 2005). Offered giveaways in the stand also have disadvantages, as this can attract visitors for the wrong reason, meaning that visitors only come to the booth attracted by giveaways, instead of being genuinely interested in the firm’s products (Hollensen, 2007). Firms need to remember that planning, promotion and follow-ups after the show constitute the most important part when participating in trade shows (Stevens, 2005).

Moreover, the firms’ intentions about participating at trade shows differ with regard to what relationships they are looking for. For firms seeking short-term sales, trade shows are not a profitable event. These events are more suitable for companies who want to make long-term commitments to new business partners and markets (Hollensen, 2007).

1.1.4 Visiting instead of exhibiting

Firms may choose to visit a trade show instead of exhibiting. Reasons for this are that it is an opportunity for the firm to learn, buy products and develop networks as well as to create brand-awareness within the industry. Additionally, the firm can see and analyze the competitor’s products (Chapman, 1995).

Kirchgeorg et. al. (2005) categorizes trade show visitors into four groups, namely:

Intensive trade show users. With the main goals of gathering information, uphold contacts

and to survey the industry.

Focused trade show visitors. These visitors know exactly what they want and address the

main target groups on their own.

Practice-oriented trade show users. They do not have clear objectives by attending to the

trade show; instead they seek general information about products.

Trade show browsers. Normally use trade shows with the reason of gaining experience about

the event.

Before visiting a trade show the firm declares objectives for the participation at the trade show, which further will affect their behavior at the show. This objective-behavior aspect is also named by Kirchgeorg et. al. (2005) as the means-end concept, this means that “*…+ a trade fair visitor gains an

impression of the suitability of an exhibit (means) for fulfilling individual visitor objectives (end)”

(p.999). What needs to be remembered is that visitors do not necessarily share the exhibitors’ objectives concerning trade show participation (ibid).

However, time is money and the firm needs to consider that a trade show may last for a whole work week and it thereby becomes important to set up clear desirable goals for what the company wants to achieve by visiting this event. At the same time, the firm needs to discuss what might have been achieved if they stayed at home instead (Chapman, 1995).

9

1.2 Problem discussion

The matter of trade shows is a well researched field in general. However, research about how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from Sweden have used trade shows as a mean for internationalization of their firm is still unexplored. Therefore, this area needs further research as SMEs are the major source of employment throughout Europe. Out of the 25 member countries in the EU, approximately 23 million SMEs provide 75 million jobs and represent 99 per cent of all enterprises (European Commission, 2005). Statistics show that Swedish companies are characterized by being SMEs; out of Sweden’s 900 000 companies 99.9 per cent are SMEs (www.ekonomifakta.se, 2009-04-10).

As this thesis will discuss how Swedish SMEs use trade shows as a first step or trigger to internationalize their firm, a definition of a SME is crucial. The European commission defines SMEs as “the category of micro; small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are made up of enterprises which

employ fewer than 250 persons and which have an annual turnover not exceeding 50 million euro, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding 43 million euro” (European commission, 2005,

p.5).

For this thesis it is also important to give a definition of the term trade show. Kirchgeorg et. al. (2005) explains that trade shows are characterized by that they are temporary and normally occur once a year in a certain location (ibid). Hollensen (2007, p.560) extends the definition by describing that “a

trade fair or exhibition is a concentrated event at which manufacturers, distributors and other vendors display their products and/or describe their services to current and prospective customers, suppliers and other business associates and the press”.

Kirchgeorg et. al. (2005) extends this discussion by defining certain kinds of trade shows; general-, specialized-, multi-industry- as well as corporate trade shows. In general trade shows, the exhibitors display their products towards general consumers. Specialized trade shows are directed towards a certain industry or segment. In multi-industry trade shows exhibitors originate from many different industries. Lastly, in corporate trade shows all presented products come from one manufacturer or wholesaler (ibid).

A firm’s internationalization process can also be connected to trade shows as this is a marketplace where orders might be encouraged. Firms in the starting of internationalization can be supported by export assistance, meaning that the firm gets a stand in a government-organized and sponsored booth. This kind of stand does not only get at lot of attention but also helps firms with little experience from international markets and trade shows (Seringhaus & Rosson, 1999).

1.2.1 Trade shows as a marketing communication tool

Trade shows are normally seen as part of a firm’s marketing strategy, especially appropriate for industrial products. The event is a great occasion for a company to directly speak to their main target group and increase sales, as some products have to be seen and tested before a purchase decision can be made (Kirchgeorg et. al., 2005). Further, are trade shows a marketing tool that helps a firm to become even more competitive and successful internationally (Seringhaus & Rosson, 1998).

Hollensen (2007) argues that business (B2B) marketing varies from the business-to-customer (B2C) marketing. This by defining what a B2B market is; the market has not as many buyers as the B2C does and is often concentrated to a certain region. In the process of purchasing, the

10 buyers are many and professional, hence the absence of intermediaries. Lastly, the relationship between the buyer and seller in a B2B context is often closer and developed during a long period of time (ibid). In trade shows aimed at the B2B industry, the selling process of a firm’s products occur in a face-to-face environment; also being a common factor with trade shows aimed at B2C (Stevens, 2005). Hollensen (2007) considers personal selling as a very effective method at the same time as this is a very expensive affair for SMEs due to their limited resources.

1.2.2 Demarcations

Extensive research has been conducted about trade shows and limitations are required for this study. Considering the time span available, we have decided to focus on Swedish SMEs that participate in trade shows. The limitations towards SMEs became apparent because of that larger companies (LSEs) hold other prerequisites than SMEs and often already have an established international business. Furthermore, the development of SMEs internationalization process is according to us a more interesting phenomenon. Besides that, the research is limited to SMEs from the region of Kalmar and the area of Småland on the south-east coast of Sweden.

The research has also been limited due to that we received lists from the largest trade show organizers in Sweden, Svenska Mässan in Gothenburg and Älvsjö Mässan in Stockholm. These lists were limited to participants from the trade show named ‘Nordbygg’ in Stockholm, which is the largest industry trade show for construction as well as ventilation and sanitation. The list provided by Svenska Mässan contained firms participating in the trade show called ‘El-Fack’, focusing on the electricity industry. Interview respondents were chosen based on the firms listed.

‘Nordbygg’ and ‘El-Fack’ are aimed at the B2B context, which is the reason for the exclusion of firms participating in trade shows directed towards the B2C segment.

1.3 Problem definition

How do SMEs use trade shows as a trigger or first step to internationalize?

Which role does networking play in a trade show context?

How does the SMEs network affect their internationalization process?

1.4 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to investigate how Swedish SMEs use trade shows as a trigger or first step to internationalize their business. Moreover, this study aims to examine which role networks play for SMEs in a trade show context as well as an international perspective.

1.5 Outline of the study

Chapter one provided an introduction of the phenomenon of trade shows as well as an outline of our

research problem. The remaining outlook of the thesis will be as followed:

Chapter Two provides an overview of the theories the research will be based upon. The theories

being presented are about the outcome- and behavior-based control system, the motives for internationalization, followed by the Uppsala internationalization model. Furthermore, the Network model will be discussed as well as the four cases of internationalization. The chapter will be finalized with a theory concerning the internationalization process and market selection of SMEs.

11

Chapter Three gives an overview of research methods used in this study. The chapter starts with an

outline of the research purpose and the approach used during the study. Different research strategies are being presented followed by a discussion of the different data collection methods used. Further, the sample selection process is accounted for as well as the research quality.

Chapter Four will present the empirical data collected through interviews with Euronom AB, Halltorp

Rördelar AB, Kraftelektronik AB, Proton Lighting AB, Trebema AB and TTM Energiprodukter AB.

Chapter Five will provide a discussion of our theories in connection to our empirical data; this in

order to examine if theory matches reality. The chapter will be finalized with future research suggestions.

12

2. Theoretical framework

The following chapter gives an outline of theories about trade show performance, networks as well as the internationalization processes of firms. The theoretical framework will make it easier for us to collect and interpret our empirical data and to examine our research problem.

2.1 Trade show performance: Outcome- and behavior-based control system

Trade show performance is a research field that is limited or none existent on a theoretical level according to Hansen (1999). Hansen (1999) used the marketing control system to explore the trade show performance field, which is divided into the outcome-based control system and the behavior-based control system. A control system is defined by Hansen (2002, p.2) as “*…+ an organization´s set

of procedures for monitoring, directing, evaluating, and compensating its employees.”

The outcome-based control system has traditionally been used for measuring trade show performance with a focus on the activities carried out during the trade show. These activities include for instance the number of booth visitors, amount and cost of new business contacts as well as cost per visitor (Hansen, 2002). In behavior-based control systems the process of the trade show is the focal point instead of its outcome. In this case, the sales force has to behave according to the company’s marketing strategy. Hansen (2002) points out that the term ‘behavior’ refers to what people do.

Hansen (1999) identified one outcome-based dimension and four behavior-based dimensions. The outcome-based dimension considers sales related activities and includes sales conducted during and after the trade show. Furthermore, the launching of new products and direct selling are regarded as parts of these activities. The behavior-based dimensions, on the opposite, include the following activities:

Information gathering activities include, as the name reveals, information gathering about competitors, customers, new industry trends as well as products. These activities are a potential objective by the exhibiting firm.

Image-building activities concern image building of the company and to maintain a good reputation. Three motives for image building are identified; competitive pressure, customer expectations as well as to use the trade show for transferring the company’s image to the marketplace.

Motivation activities refer to keeping the staff and customers motivated during the trade show.

Relationship-building activities include the building of new relationships as well as the maintaining of current relationships. Four variables are defined; to maintain relationships with current customers; to develop relationships with new customers; to meet important actors within the industry; and to personally get in touch with the clientele (ibid).

The control system constitutes a basic framework for measuring trade show performance and shows how these systems influence the staff present during the trade show (Hansen, 1999). Behavior-based control is supposed to generate a higher level of performance in order to meet the customers’ needs as well as to achieve the companies marketing goals in a long-term perspective. On the opposite, the outcome-based control will lead to a higher performance with regard to sales at the show (ibid).

13

2.2 Motives for internationalization

Hollensen (2007) explains that internationalization occurs when a company has decided to expand some of its business activities into an international market. Activities that can be internationalized for example are R&D, production as well as selling. For SMEs the internationalization process often is discrete, which means that the management regards each internationalization undertaking as distinct and individual (ibid).

Coviello and Munro (1997, p.115) define internationalization as: “*…+ the process by which firms both

increase their awareness of direct and indirect influences of international transactions on their future, and establish and conduct transactions with other countries.”

Firms which have decided to internationalize usually do so to make money according to Hollensen (2007). This alone, seldom is the only reason as a lot of other factors have to be taken into account when making such a decision. A lot of internationalization motives exist and are divided into proactive and reactive motives. Proactive objectives focus on implementing a strategy change to exploit new market opportunities. Reactive motives show that the firm is reacting on pressures or threats in its home market or foreign market and in relation to this changes its activities over time (ibid).

The major proactive objectives for internationalization of a business involve profit and growth goals, a managerial urge to start the firm’s internationalization, technology competence or the possession of a unique product. Moreover, foreign market opportunities and economies of scale as well as tax benefits are included in the category of proactive motives. Reactive motives, on the other hand, are about that the firm feels pressure from its competitors who have succeeded in their internationalization or that the domestic market has become saturated and growth opportunities thereby limited. Furthermore, overproduction and unexpected foreign orders can be included to reactive objectives. A seasonal demand in products could also be a reason for exporting as well as the physical and psychological closeness to the foreign markets (Hollensen, 2007).

Chetty and Campbell-Hunt (2003) further describe that the attitude of the decision makers, the management’s expectations on growth as well as the manager’s commitment towards internationalization are important influences when the firm desires to expand its business to foreign markets. The authors argue that it is not enough for a firm to have the right product, the firm also needs to have the right attitude (ibid).

On the other hand, non-driving forces for internationalization are present, which include insufficient knowledge about foreign markets, a lack of international experience as well as inadequate language skills. Other firms may not have any intentions at all to expand their business abroad (Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2003).

2.3 The Uppsala internationalization model

The Swedish researchers, Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) and Johanson and Vahlne (1977) from the University of Uppsala conducted a lot of research during the 1970s on the internationalization process. The researchers studied the internationalization of Swedish manufacturing firms and in connection to this they implemented a model of the firm’s market choice and foreign entry mode. One of the first observations they made was that firms tended to internationalize towards nearby foreign markets and stepwise, with growing experience, entered

14 more distant markets. The second observation made by the researchers, was that companies had a tendency to enter new markets through exports. Very few firms entered new markets with their own sales organizations or production plants (Hollensen, 2007). According to Armario, Ruiz and Armario (2008) firms develop their business in domestic markets and internationalization occurs in line with incremental decisions, which are limited by two factors, namely resources as well as insufficient information. This means that the two factors constitute a major barrier for expanding to foreign markets. Nevertheless, SMEs can overcome these barriers by joining business networks as this will give them access to more resources at the same time as the firm will benefit from being larger in size through the network (Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2003).

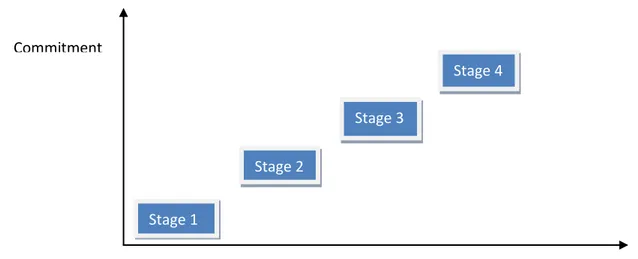

Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) have recognized four different international entry modes for a firm; each stage representing a higher experience and higher degree of market commitment. The following model illustrates the Uppsala internationalization model, which is followed by a description of the four stages:

Figure 2.1: The Uppsala model

Stage 1: No regular export activities, meaning that the firm does not have enough resources or information about the foreign market.

Stage 2: Export occurs through independent representatives. Stage 3: The firm establishes a foreign sales subsidiary.

Stage 4: Foreign production or manufacturing units are being established (ibid).

Companies start their international business on markets with low uncertainty (Armario, Ruiz & Armario, 2008). According to Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) firms tend to internationalize their business towards close markets which are easily understood and which have a low degree of psychic distance. Psychic distance refers to differences in language, culture and political systems; factors that can influence the communication between the firm and the foreign market. Only gradually, firms will enter markets with a greater psychic distance (ibid). Armario, Ruiz and Armario (2008) explain that as soon as the firm has gained sufficient international experience, further decisions on entering new markets will be based upon factors such as market size or the global economic climate. The Uppsala model is an incremental internationalization process, accelerated by a stronger commitment and experience of the foreign market (ibid). Johanson and Vahlne (1977)

Commitment Time Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4

15 argue that market knowledge and market commitment are closely related. According to the authors, knowledge can be seen as a resource, which means that the more knowledge the firm has about a market, the more valuable become the resources. This leads to that the firm’s commitment to the market gets stronger (ibid).

The Uppsala model has nevertheless encountered critique according to Nordström (1991). Not every firm is following the concept of the model, as some firms tend to leapfrog certain stages of it. This means that companies enter markets with a greater psychic distance in an early stage. Nevertheless, it is claimed that internationalization processes of firms generally occur in a faster pace today (ibid). ‘Born globals’ are emerging on the market; firms that have the ability to internationalize much faster than firms with a long experience from their home market. It is common for ‘born globals’ to be established in international networks before the company has been founded. This means that the company’s internationalization process is eased due to their earlier experience and knowledge from foreign markets (Johanson, Blomstermo & Pahlberg, 2002).

2.4 The Network model

Ford (2002, p.229) puts the network model into a simple definition: “*…+ the network approach sees

internationalization in terms of a company’s existing home or overseas relationships, those that it may have to establish to operate in a new market (and perhaps break elsewhere) and the actions of both the company itself and others around it. In other words, as a process driven by the interaction of all the actors in a network.”

Hollensen (2007) defines business networks as a network where business actors are interdependent and linked to each other through relationships. These relationships are seemingly flexible and may change in connection with environment changes (ibid). The network approach assumes that firms cannot be seen as individual actors; rather they have to be related to other actors in the international environment. Firms are interdependent of each other and relationships with other firms can be used to connect with other international networks (Johanson & Mattson, 1988). Through these relationships the different firms can take advantage of each others resources in the network (Håkansson & Snehota, 1989). On the other hand, Ritter (1999) claims that not all relationships carry good things with it; mistrust and dependencies may come up. Moreover, it is a time consuming and costly process to gain access to external resources through relationships (ibid). Every actor within the business network keeps the network in function as long as everyone within the network engages in relationships with each other. The shape of the network can change easily as any actor within the business network can change relationships and engage in new ones; thereby changing the structure of the network (Hollensen, 2007). According to Johanson and Mattson (1988) a network can either be tightly structured or loosely structured; in tightly structured networks the interdependence of firms is high and the positions of them well defined at the same time as the bonds between the companies are very strong. On the opposite, the loosely structured networks have no well defined positions of the firm nor do they have any strong bonds between them (ibid). Simply put, certain networks are strong whereas others are weak (Donaldson & O’Toole, 2002). Networks are divided into three categories by Donaldson and O’Toole (2002); social networks, bureaucratic networks as well as proprietary networks. The social network relies on human interaction, with personal networks being most important for small businesses. These personal ties

16 ease a successful competition, which is accomplished through informal person-to-person networks, word-of-mouth rumors as well as repeat business. Bureaucratic networks are highly formalized and can differ depending on the power of the members of the network. In the proprietary network, the ownership of assets is regulated in advance; joint ventures being an example in this category (ibid). Hollensen (2007) defines the actors inside of a network as connected through a number of ties, for example technical, social, administrative or personal ties. He explains that there exists a basic assumption about the network model that the single firm is dependent on the resources controlled by other firms. These resources in turn, get accessible through the firms network positions. Despite that, entering into a business network is not an easy task as it requires motivation and the willingness of other actors within the network to interact with the firm outside of it (ibid). Håkansson and Snehota (1989) clarify that a relationship status only is accomplished if the other party at least has taken some action to it.

As mentioned earlier, every actor within a network brings with it resources; for some actors being unique resources whereas for others working as a complementing resource to its own one. From a network perspective the combination of resources from different actors is a great strength, as this gives the individual firm a stronger position. Additionally, this results in new knowledge within the reinforced network. Networks are often considered as a knowledge resource due to that the sharing of resources builds learning as well as adaptation skills among its members (Donaldson & O’Toole, 2002). It is the ongoing interaction with other companies within the network that gradually leads to the learning of how the market works at the same time as this interaction strengthens the engagement of each actor (Johanson, Blomstermo & Pahlberg, 2002).

Business networks can cross country borders according to Hollensen (2007), at the same time as the network view lays down that an internationalizing firm primarily connects with a domestic network in the initial stage. These domestic network contacts later on can be used as connections to other networks abroad. The author concludes that the internationalization of a firm can be eased by entering a business network (ibid).

Johanson, Blomstermo and Pahlberg (2002) claim that the network context is important as it is a source of information about the environment. Every business is conscious of their own company and how it works, but by having close relationships to other actors a company can easily get access to information about other businesses and how these work. The authors further explain that the formed relationships can give the company an insight to the other firms’ thoughts about the future. Close relationships enable the company to estimate and understand trends which can be critical for the company (ibid). Seringhaus and Rosson (1995) referred to by Evers and Knight (2008) claim that trade shows are a good opportunity and forum for networking. Further, it is recognized that the network approach is important for firms as all gained relationships are crucial for the firm’s survival. Network relationships have a great affect on small firm’s internationalization process (Evers & Knight, 2008).

2.4.1 Four cases of internationalization

Ford (2002, p.229) describes internationalization as “an outward extension of a single company’s

17 The earlier presented Uppsala model presents internationalization as independent, with no regard to competition or the situation on the market. These aspects can be combined; Hollensen (2007, p.72) explains: “A ‘production net’ contains relationships between those firms whose activities together

produce functions linked to a specific area. The firms degree of internationalization shows the extent to which the firm has positions in different national nets, how strong those positions are, and how integrated they are.” According to Johanson and Mattson (1988) the term ‘net’ is used specifically to

identify parts of the total network. Production net refers to a firm’s relationship connected to a certain product area, whereas national nets consider networks in other countries (Chetty & Holm, 2000).

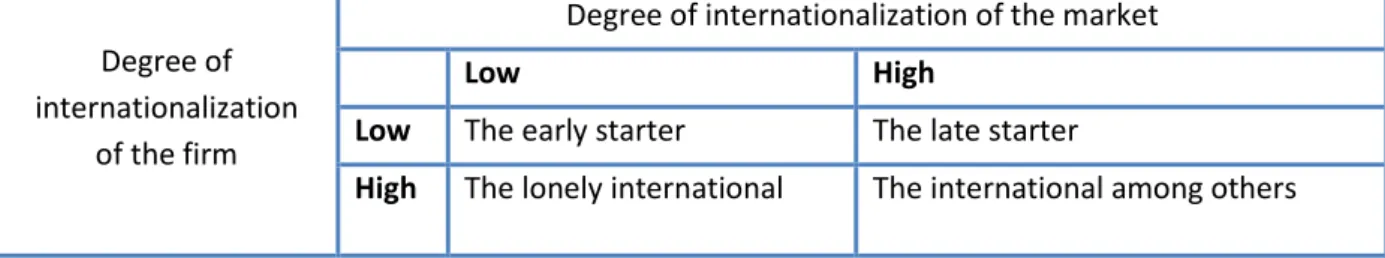

Hollensen (2007) extends this definition by relating to four different cases of internationalization among firms; firms with a low or high degree of internationalization and on the opposite, a low or high degree of internationalization of the market (ibid). Johanson and Mattson (1988) further explain these four situations as internationalization processes connected to the network model.

Figure 1.2: Internationalization and the Network model

Degree of internationalization

of the firm

Degree of internationalization of the market

Low High

Low The early starter The late starter

High The lonely international The international among others Source: Johanson & Mattson, 1988, p. 298

The first case of internationalization, described by Hollensen (2007) is the ‘early starter’. Here, there is no existing important relationship between competitors, customers, suppliers or other firms, neither on the domestic nor on the international market. The internationalization process is in this case described with a slow and stepwise involvement in the market, often arranged by an agent (ibid). The firm is inexperienced in foreign markets and Johanson and Mattson (1988) argue that such experience cannot be gained from relationships in the firm’s domestic market. Hollensen (2007) explains that the more knowledge the firm has gained about the foreign market, the more committed it becomes. This scenario also is confirmed by Johanson and Mattson (1988), who add that firms rather choose markets which are similar to the home market as the firm already contains a certain degree of knowledge about it. The authors bring out that the ‘early starter’ prefers to export products instead of manufacturing them abroad. As soon as the firm’s internationalization has increased, it will change from being an ‘early starter’ to become ‘a lonely international’ (ibid).

‘The lonely international’ describes the firm as experienced regarding relationships with other foreign countries. The firm handles situations outside its own environment and cultural values (Hollensen, 2007). Considering the structure of networks, ‘the lonely international’ can easier get access to tightly structured networks as it already has gained a lot of knowledge about different national markets (Johanson & Mattson, 1988). Hollensen (2007) explains that any taken initiative for further internationalization does not origin from inside the production net, as the actors within this network have a limited knowledge about internationalizing processes. This is not a problem though, as the ‘lonely international’ has the capability to promote its production net as well as the firms involved in it (ibid). These statements are also confirmed by Johanson and Mattson (1988), but they

18 add that the firms which have internationalized before their competitors may gain advantages by that, especially in tightly structured networks. This due to that the firm already has its network position before their competitors.

The third case of internationalization, ‘the late starter’ has the disadvantage of being less experienced in other markets compared to its competitors. Moreover, the firm often has the problem to establish new positions abroad because of tightly structured networks (Johanson & Mattson, 1988). The best distributors already conduct business with competitors and as a newcomer; actors within the net can make the business unprofitable because of high pricing. Timing is an important aspect to take into consideration when internationalizing a business. In this case, also the size of the firm has to be taken into account. SMEs can generally adjust more easily to foreign environments as the firm is flexible, which is an important factor in an international net. A small firm can easier adjust itself and react faster on initiatives of other firms, which is crucial in the case where other firms in the net already are international (ibid). Larger firms (LSEs), on the other hand, are often less specialized, making their situation much more complex than in the case of the SME (Hollensen, 2007). Johanson and Mattson (1988) point out that there exists a general problem for internationalizing firms; a firm that already is large in its home market may have difficulties in finding a niche on the international market.

Lastly, ‘the international among others’, gives the firm the possibility to use connections in one net for further extension or penetration into other nets (Hollensen, 2007). The establishment of sales subsidiaries is common in this stage as the firm has a high international knowledge at the same time as a stronger need for coordinating activities between the markets is required (Johanson & Mattson, 1988). The ‘international among others’ mainly meets competitors with a high international integration and operates in tightly structured markets. Changes in the firm’s position may only occur through for example joint ventures or acquisitions. The driving forces for internationalization in this case are based on that the firm has the urge to use its network position in a strategic manner (ibid). It is concluded by Hollensen (2007) that internationalization is seen as process where knowledge and learning go hand in hand, even though if internationalizing occurs in a fast pace.

2.5 Internationalization of SMEs

Hollensen (2007) makes clear that globalization is threatening the internationalization of SMEs. Globalization is increasing the competition for SMEs due to that more and more multinational corporations emerge on the market. Furthermore, as a consequence of globalization, trade liberalizations all over the world result in the losses of earlier protected markets, at the same time as this brings new international market opportunities. For SMEs, the entering into a foreign market brings several advantages by offering new and more profitable markets as well as it may give the firm a more competitive position. But, to manage such a competitive environment the management of a SME should preferably conduct an entrepreneurial management style (ibid).

Manolova and Bush (2002) referred to by Hollensen (2007), argue that when it comes to the internationalization of SMEs, ‘personal factors’ become important; some more than others. The authors believe that if the firm’s manager has a positive attitude towards the international environment, the firm will more likely succeed in internationalizing their SME. On the other hand, Hollensen (2007) points out that SMEs have limited resources to be able to compete with larger multinational firms, both in their home market as well as with emerging actors from abroad.

19 Globalization is creating a more or less hostile business environment for smaller firms, at the same time as SMEs with an entrepreneurial spirit have the capabilities to overcome those challenges. Nevertheless, for a SME, it is of large importance to be prepared when internationalizing. To conduct a plan in advance is crucial in international business as the business environment becomes much more complex than in the home environment (ibid).

2.5.1 International market selection of SMEs

SMEs select their international markets differently than LSEs, as these two types of firms have diverse prerequisites. According to Johanson and Vahlne (1977), which Hollensen (2007) refers to, choose SMEs their international markets based on the following criteria:

“Low ‘psychic distance’: low uncertainty about foreign markets and low perceived difficulty of acquiring information about them. ‘Psychic’ distance has been defined as differences in language, culture, political system, level of education or level of industrial development.

Low ‘cultural’ distance: low perceived differences between the home and destination cultures

Low geographic distance” (Hollensen, p.244)

SMEs often choose to internationalize towards neighboring countries due to that a close geographic distance often involves cultural similarities likewise as the firm has a better international knowledge to close markets and easier can get access to information. Overall, it is common for SMEs to select markets that are most similar to them and thereby easier to understand. The SMEs selection is limited to nearby countries and gives the company two choices; to stay in the home market or to expand to a nearby country. This behavior of market selection often can be explained by that SMEs choose their markets based on intuition and practical reasons (Hollensen, 2007).

20 Figure 2.3: Summary of theories

Source: Constructed by the authors

2.5 Internationalization of SMEs

2.5.1 International market selection of SMEs

2.4 The Network model

2.4.1 Four cases of internationalization Table 2.2 Internationalization and the network model

2.3 The Uppsala internationalization model

2.1 The Uppsala model

2.2 Motives for internationalization

21

3. Methodology

This chapter will cover the methodology used during the research process. The choice of research method is based on our research purpose and the connected research questions to it. Additionally, we will give our motivations and justifications for each chosen method.

3.1 Research purpose

The purpose of a research can be classified into three different research designs; the exploratory, descriptive as well as casual design (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). Explorative research considers collecting as much knowledge and information about a research area as possible, which means that a comprehensive view of the study field is presented. This research design often involves different techniques of information gathering (Patel & Davidson, 2003). In descriptive studies the problem is structured and a lot of information about the problem already exists. Casual research is well structured as is the descriptive study, but additionally aims to answer questions with relation to cause and effect (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005).

In this study, the research purpose is well defined as we exactly know what to investigate and in what way. There is a lot of written and published material about trade shows, giving us as researchers a good initial position. But, as we aim to investigate how SMEs participation at trade shows is connected to their internationalization, answers of cause and effect relations are demanded. This is why this thesis will be based upon a descriptive and casual study design.

3.2 Research approach

According to Ghauri and Grønhaug (2005) all researchers need to collect data to get answers to their research questions. But to decide which method and technique is most suitable for the study depends on the research problem and its purpose. Two research strategies do exist; the quantitative as well as qualitative method (ibid). Quantitative research method involves a lot of measurements and statistical analysis in the information gathering process (Patel & Davidson, 2003). It has a larger emphasis on tests and verifications, which means that the data is based on meanings derived from numbers (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). The qualitative method, on the other hand, is more focused on a deeper understanding of a certain phenomenon and data is collected through interviews and analysis of text material (Patel & Davidson, 2003). Ghauri and Grønhaug (2005) present the qualitative research further on as a method with emphasis on understanding, where the collected data is based on meanings being expressed. The researcher has a limited knowledge about it and thereby aims to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon.

For a researcher, it moreover becomes important to relate existing theories to reality, which often is regarded as a major issue in all scientific work (Patel & Davidson, 2003). The relationship between theory and reality can occur through deduction, induction and abduction; all three of them representing different ways to work after. The deductive approach is marked by that the researcher starts by testing various hypotheses on existing theories, followed by the collection of empirical data. Finally, the empirical findings get compared with the original theory, to either confirm or dismiss the made hypotheses. Induction works the opposite way, where the researcher starts with observations from reality and in connection to this comes up with a theory on the basis of the empirical data results (ibid). Gillham (2008, p.7) explains the inductive approach as “making sense of what you find

after you’ve found it.” Patel and Davidson (2003) consider the inductive approach as risky as it may

22 third approach, relies on a preliminary theory based on an individual case. Here the deductive and inductive approach meet due to that the preliminary made theory is tested against new empirical findings, which enables the altering of theory.

Our study will be based upon a qualitative research method as we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of trade shows and how SMEs use and can use these events as a trigger or first step to internationalize. We will gather all required information through interviews with the concerned firm representatives as well as through written and published text material, making the qualitative method the most appropriate choice. Furthermore, this dissertation will be based upon an inductive approach, with empirical findings made through interviews. On the basis of the performed interviews, appropriate theory findings have been implemented by us; to later on constitute the base for our discussion and conclusions.

3.3 Research strategy

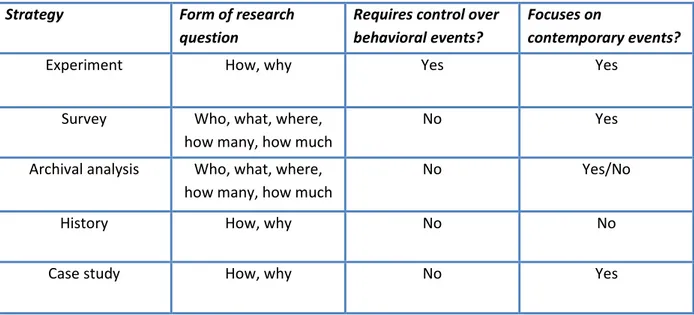

Collecting data occurs in many different ways, Yin (1984) mentions five research strategies connected to this; experiment, survey, archival analysis, history as well as case study. These strategies are distinguished by three conditions, namely the type of research question asked, the degree of control the researcher has over behavioral events and the degree of focus on contemporary in opposition to historical events. Yin (1984) has come up with a table presenting these three conditions and how they are related to the mentioned five research strategies.

Table 3.1: Relevant situations for different research strategies

Strategy Form of research question

Requires control over behavioral events?

Focuses on

contemporary events?

Experiment How, why Yes Yes

Survey Who, what, where, how many, how much

No Yes

Archival analysis Who, what, where, how many, how much

No Yes/No

History How, why No No

Case study How, why No Yes

Source: Yin, 1984, p. 17

This research will be based on the case study research strategy. Yin (1984) points out that the aim of using a case study as a strategy should be to investigate a contemporary event, over which the researcher has little or no control. A case study in business studies usually is conducted when it is hard to investigate the problem outside its natural habit as well as when the collected data is difficult to quantify (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). Ejvegård (2003) further explains that the aim with case studies is to take a small part of a large course of events and hereby describe reality with the help of the case. As we aim to investigate SMEs participation at trade shows and how this relates to the firms’ internationalization as well as networking, we can exclude the history aspect due to that this strategy is focused on the past (ibid). Survey research mostly occurs within quantitative studies and is

23 about collecting data mainly through questionnaires or structured interviews (Bryman & Bell, 2003); therefore it could be excluded from this study. Our research will neither make use of experiments. Experiments are conducted when the researcher has the possibility to directly manipulate behavior in a systematic way (Yin, 1984). Further on, Bryman and Bell (2003) explain that experiments are rare in business and management research due to the difficulties of achieving the essential control in the organization experimenting with. Since our research questions are not aimed to answer questions of who, what, where, how many and how much, the archival analysis also could be excluded from our research strategy.

Yin (1984) mentions two types of case studies; the single-case study and the multiple-case study. Single case studies are used when a certain case is significant and the researcher wants to test it on an already established theory (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). This type of case study can be used when the case has a unique characteristic or the aim is to conduct an exploratory research (ibid). A multiple-case study is conducted as soon as more than one case study is performed. Usually two or more cases of companies are used for comparison, which puts the researcher into a better position to test which theory will fit and which can be dismissed (Bryman & Bell, 2003). Multiple-case studies, moreover, are regarded to be more extensive than single-case studies, which has the disadvantage of being a more time consuming research strategy (Yin, 1984).

This research is based on a multiple-case study as six different respondents from different companies got interviewed. The multiple-case study research was used by us to gain a better and broader understanding of how SMEs use trade shows in their daily operations and how their participation at trade shows can lead to the entering of new foreign markets. Moreover, this strategy was selected as we aim to compare how different companies from the region use trade shows as a networking opportunity.

3.4 Data collection method

Patel and Davidson (2003) talk about primary- and secondary data, where the type of data is dependent on the proximity to the information provider. Primary data is collected through eyewitness descriptions and interviews, whereas secondary data consists of all remaining sources (ibid). In case study research, data can be collected through six sources of evidence, namely documents, archival records, direct observation, participant observation, physical artifacts as well as interviews (Yin, 1984).

Yin (1984) means that data collection through documents is almost used in every case study and can take many different forms. Nevertheless, a researcher using documentation as a data collection method has to be aware of that any document was written for a special purpose and for a certain group of people, why a critical interpretation of the written content becomes crucial. Archival records consist of service- and organizational records, maps and charts, lists, survey data as well as personal records; the value of these data is individual for every conducted case study (ibid). Ghauri and Grønhaug (2005) present the data collection method through direct observation as a possibility to watch and listen to other people’s behavior, which will lead to a learning outcome and the option to make an interpreting analysis about the observations. Closely connected to this is the participant observation, where the observer becomes a part of the situation or company (ibid). Physical artifacts are according to Yin (1984) a tool or instrument, a work of art or some other type of physical data. Normally this data collection method occurs within field visits (ibid). At last, interviews are often

24 considered to be the best data collection method. Two types of interviews exist; the structured as well as the unstructured interview. Both can be conducted in three different ways; by a telephone call, by mail or in a personal manner (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005).

In this case study research, data collection occurred by mainly using interviews and documentation. Archival records were not valuable for our case study, nor were physical artifacts. Observation was excluded as this is a vastly time consuming procedure and due to our limited time this method was not considered as an alternative. Moreover, observation would not help us to answer our research question. Documentation was used to get a better overview of the company’s business and their product range. Interviews became an obvious choice of data collection method as this enables us as researchers to gain a deeper knowledge of the company’s participation at certain events and to get a better overall insight into the organization.

Bryman and Bell (2003) talk about ‘triangulation’, which according to their definition means, that the researcher has collected information through multiple sources. This is the case for our research since both interviews and documents have been used for data collection.

Besides that, Patel and Davidson (2003) bring out that it is of great importance to critical review the collected data and to question the purpose and author of the written material. In this dissertation we mainly have used existing theories to emphasize the results from our empirical research. The theories are well recognized and mentioned several times in international business contexts as well as in other implemented researches.

3.4.1 Interview techniques

As mentioned before, there are two types of interviews; the structured and the unstructured interview, with a third type, the semi-structured interview emerging in literature discussion (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). The structured interview is about using a standard questionnaire with fixed and limited alternatives of answers, which often is regarded as a quantitative interview type (ibid). Bryman and Bell (2003) moreover consider the structured interview being inflexible due to the standardized approach this alternative brings with it. The unstructured interview or qualitative interview is unlike the structured type more flexible (ibid). Standardization is no matter of fact in this type of interview and the respondent has the freedom to answer in his or her own words. The interview more or less takes the form of a conversation between interviewer and interviewee (Patel & Davidson, 2003). The semi-structured interview, which is discussed by Bryman and Bell (2003), is the interview approach that will be used in this dissertation.

In this type of interview, the interviewer has an interview guide with prepared questions sorted into different topics. The interviewee still has a great freedom to answer in own words as the questions more work as a guide. New questions can arise during the conversation as the interviewee’s answers can lead the interviewer to new ideas. However, more or less all questions from the interview guide will be asked (Bryman & Bell, 2003).

In this thesis we have used both telephone and personal interviews with the chosen company respondents. Two interviews were conducted via telephone due to the geographical distance to the companies. The third interview held via a telephone call occurred in this manner because of the respondent’s tight schedule and his limited office hours. Despite that, three personal interviews were conducted, as the respondents suggested a personal interview, at the same time as we had a close

25 geographical distance to these companies. The interview guide was sent before-hand to the interviewees, to enable them for preparation. Further on, an e-mail was sent to the interviewees to confirm the time and date of interview as well as to give them a reminder of our research purpose and to ask them for the permission to record the interview. During all interviews we used the same interview guide, with scope for follow-up questions. The interviews were approximated to take between 30 to 45 minutes and a tape recorder was used to record the interviews for making later transcriptions of them possible. Ghauri and Grønhaug (2005) consider the recording via tape recorder as a useful method, at the same time as they recommend some note taking during the interview.

The six conducted interviews, all together lasting for approximately 3,5 hours, were later transcribed by us. During the transcriptions some issues had to be dealt with, such as dialectic problems as well as noises through the telephone. This led to a prolonged transcription time as the interview had to be rehearsed a lot of times. To be sure that our transcriptions agreed with the taped interviews, we sent the transcribed versions to the respondents, to enable them to fill in missing gaps and to clarify certain statements. During the compiling of our empirical findings more questions arose, why some follow-up questions were sent to the company respondents. Answers to these questions were necessary in order to be able to solve our research problem.

3.5 Sample selection

This research will, as mentioned earlier, conduct a multiple-case study due to the fact that six different case studies are included. The cases will be based upon six different interviews with representatives from the following companies; Euronom AB, Halltorp Rördelar AB, Kraftelektronik AB, Proton Lighting AB, Trebema AB as well as TTM Energi AB.

Ghauri and Grønhaug (2005) present two sampling alternatives, probability sampling and non-probability sampling. Probability sampling is about random selection, giving anyone a chance to be selected. The results gained from here later on allow the researcher to draw general inferences from that. Non-probability sampling works the opposite way, making the results gained from this sampling procedure non-“representative”. Results not being “representative” cannot be applied on a whole group. On the other hand, this type of sampling may be useful when aiming for a deeper understanding of a certain phenomenon (ibid), which is the intention for our study. For that reason, this research will be based upon a non-probability sampling.

3.5.1 Sample criteria

When selecting the companies and the persons being interviewed, we used criteria closely related to our research purpose and problem. As we aim to investigate the phenomenon of trade shows and how SMEs use these events as a trigger or first step for internationalization, our first criterion was to interview companies that have participated in trade shows. Moreover, this research focuses on SMEs why only firms within this category were chosen for our case studies. We also selected SMEs that already have internationalized or at least have some kind of international interest, as the aim of this dissertation is to have an international perspective. To restrict our field of research, we decided to investigate firms within Kalmar region and its surroundings. An industry specific criterion was not included in this research.

The companies, fitting our criteria were found by calling two of Sweden’s largest trade show organizations; Svenska Mässan in Gothenburg and Älvsjö Mässan in Stockholm. Our aim of research