vensK Botanisk

Tidskrift

Utgiven av

SvensKa BotanisKa Föreningen

Redigerad av

STEN AHLNER

BAND 62

1968

HÄFTE 4

SVENSKA BOTANISKA FÖRENINGENS

styrelse och redaktionskommitté år 1968.Styrelse:

J. A. NANNFELDT, ordförande; T. HEMBERG, v. ordförande; L. BRUNKENER, sekreterare; S. AHLNER, redaktör och ansvarig

utgivare av tidskriften; P. OLROG, skattmästare; E. BJÖRKMAN, N. FRIES, G. HARLING, E. v. KRUSENSTJERNA, T. NORLINDH,

W. RASCH, H. WEIMARCK. Redaktionskommitté:

F. FAGERLIND, N. FRIES, E. FIULTÉN, J. A. NANNFELDT, B. PETTERSSON, C. O. TAMM.

SVENSK BOTANISK TIDSKRIFT utkommer med fyra häften årligen.

Prenumerationsavgiften (för personer, som ej tillhöra Svenska Botaniska Föreningen) är 45 kronor. Svenska och utländska bokhandlare kunna direkt hos föreningen erhålla tidskriften till samma pris.

Medlemsavgiften, för vilken även tidskriften erhålles, är 35 kronor för medlemmar, bosatta i Sverige, Danmark, Finland, Island och Norge, och kan insättas på föreningens postgirokonto 29 86 eller översändas på annat sätt. Giroblankett för inbetalning av påföljande års medlemsavgift åt följer häfte nr 4. Har inbetalning ej skett före utgivandet av häfte nr 1, utsändes detta mot postförskott, varvid porto debiteras. Medlemmar er hålla i mån av tillgång tidigare årgångar av tidskriften till ett pris av 24 kronor per årgång.

Generalregister över de första 40 årgångarna finnas nu tillgängliga.

SVENSK BOTANISK TIDSKRIFT, edited by Svenska Botaniska Föreningen (The Swedish Botanical Society), is issued quarterly.

An annual fee of 45 Sw. Kr., which includes the journal, applies to mem bers outside Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Norway. The jour nal is available to booksellers for the same amount. Back volumes are available to members at 24 Sw. Kr. according to supply.

A general index, in two parts, to Volumes 1-40 is now available.

NEW RECORDS OF SCANDINAVIAN BRYOPHYTES.

BY

A. C. Crundwell and Elsa Nyholm.

Department of Botany, University of Glasgow, and Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm.

This paper records the occurrence of some bryophyte species in Scandinavian provinces from which they are hitherto unknown. Records for which no collectors’ names are cited are our own. The remainder are based on specimens in the Naturhistoriska Riks museet, Stockholm, or on specimens kindly loaned to us by the Trondheim Museum (TRH). When appropriate the previously recorded distribution of the species is given in square brackets for

each country for which new records are reported.

Pallavicinia lyellii (Hook.) Gray ex Trev. SWEDEN. Skåne, Hallands

Yäderö: edge of marsh near L. Sandhamns hallarna, 25.8.1965; northern margin of Tångakärret, 25.8.1965; east side of Oadammen, 26.8.1965. New to Sweden. Previously known in Scandinavia only from two localities in Denmark.

All three habitats were very similar. The first was the outer part of a Juncus effusus zone surrounding a marshy depression dominated by Eleo- charis sp. and itself surrounded by a Rubus plicatus- Dryopteris austriaca community. The second was a Rubus plicatus-Dryopteris austriaca com munity on the edge of Alnus glutinosa woodland. It was here that the Pallavicinia was found in greatest abundance, on and at the sides of cow- paths and in other damp spots where the vegetation was not too dense. The third place, where Pallavicinia was present only in very small quantity, was at the side of a small cow-path leading from grassland down through a Rubus plicatus- Dryopteris spinulosa zone to damper vegetation dominated by Juncus effusus. In all three places the soil was peaty.

Beside Juncus effusus, Rubus plicatus and Dryopteris, constant associates of the Pallavicinia were Agrostis stolonifera and Hydrocotyle vulgaris. Di- cranella heteromalla was the only bryophyte present in all three places, but Aulacomnium palustre and Lophocolea heterophylla were each prominent in two of them. Other associated species were Carex fusca, Rumex acetosa, Sphagnum palustre, S. fimbriatum, Dicranella cerviculata, Lophocolea cuspi- data, Cephalozia bicuspidata and Campylopus pyriformis.

Pallavicinia lyellii has sometimes been confused with Moerckia flotoviana and M. hibernica. The Moerckia species are without the central strand of Pallavicinia and are calcicolous.

Dicranella riparia (H. Lindb.) Mårt. &Nyh. NORWAY. Nordland: be

low snow patch, on soil on old road (‘materialvägen’), 450 m alt., between Haugfjell and Katterat stations, 8.7.1963. Present in considerable quantity, fruiting freely and associated with Drepanocladus uncinatus and hepaticae. The fifth known locality for this rare Scandinavian endemic, the others being in Opdal (Norway), Lule Lappmark and Torne Lappmark (Sweden) and the Karelian Isthmus (Russia, formerly Finland).

Cynodontium jenneri(Schimp.) Stirt. SWEDEN. Småland: cave in

north-south ravine, Jungfrun, Misterhult, 1917, E. Du Rietz. Värmland: Gårdsjö, Gillberga, 28.6.1881, N. C. Kindberg. Närke: by stream ca 1 km south-east of Fagertärn (Trolldalen), Askersund, 29.6.1963, N. Hakelier. Södermanland: rocks in spruce forest, Tremaskogen, Utö, 24.7.1965. [Bl., HL, Boh., Dis., Ög.?, Upl.] This very good species is probably more wide spread than the published records indicate, as the older floras did not give it specific rank and it has often been confused with C. polycarpum.

Alonia ambigua (B. & S.) Limpr. SWEDEN. Skåne: clay cliff, south coast of Ven, 30.8.1961. New to Sweden. Previously known in Scandinavia only from Denmark, from two localities in Själland (Holmen 1959). There are a number of older Scandinavian records of this species, but these are erroneous, being based on misidentifications of A. rigida (Persson 1944).

Desmatodon leucostcma (R. Br.) Berggr. (D. suberectus (Hook, ex

Drumm.) Limpr.). SWEDEN. Torne Lappmark: earthy ledge, 820 m alt.,

limestone rocks on east side of Kärkevagge, 4.7.1963. The second report of this species in Sweden, the first being from Härjedalen by Hakelier

(1966). The other Scandinavian records are all from Norway (Opl., STrd., Nrdl., Fnm.). Associated in Kärkevagge with Stegonia latifolia, as in Härje dalen and its two Scottish localities.

Tortella inclinata(FIedw. f.) Limpr. SWEDEN. Södermanland: limestone

rocks by the sea opposite Tallholmen, Utö, 23.7.1965. [Sk., Ö1., Gtl., Vg., Ög., Vrm.] Very abundant, associated with T. tortuosa and T. rigens.

T. flavovirens (Bruch) Broth, var. flavovirens. SWEDEN. Bohuslän:

on shell sand influenced by salt water, inner end of Brokilen, Kalvö, Ta- num, 5.8.1965, P. Hallberg. Previously known in Sweden only from one locality in Skåne (Crundwell & Nyholm 1962).

Krusenstjerna (1964), in his excellent account of the mosses of the Stockholm region, gives two localities for T. flavovirens on Utö. We have been unable to see the specimens on which these records were based, but we suspect that they are either T. inclinata or T. flavovirens var. glareicola, which we have previously reported from the island.

Schistidium atrofuscum(Schimp.) Limpr. SWEDEN. Torne Lappmark:

limestone rocks, 820 m alt., east side of Kärkevagge, 4.7.1963. A few well grown sterile tufts, associated with fruiting S. apocarpum. The only other Scandinavian records are from Öland and Gotland in Sweden and from Opland in Norway.

Bryum violaceum Crundw. & Nyh. SWEDEN. Småland: Gränna,

20.10.1912, A. Arvén (in Phascum acaulon). Närke: SSW of Latorp farm,

Tysslinge, 17.11.1957, N. Hakelier (in Astomum crispum). Västmanland:

Älvhyttan, Viker, 2.11.1957, N. Hakelier (in Astomum crispum). Söder manland: between Marieberg and Konradsberg, Stockholm, 28.5.1864, C. A. Fredriksson (in P. cuspidatum). Uppland: Uppsala, 2.4.1878, E.

Vetterhall (in P. cuspidatum); waste ground behind Botany Department,

Riksmuseum, Stockholm, 15.1.1965. Jämtland: with Phascum cuspidatum and Bryum klinggraeffii on soil at edge of forest road 2 km north of Tands- byn, Lockne, 10.8.1966. [Sk., Vg., Ög., Dls.] FINLAND. Åboland: ad mar- ginem viae, Pargas, 15.6.1912, V. F. Brotherus (in Bryotheca Fennica

219, Phascum acaulon). Åland: Qvarnbo, Saltvik, 5.1870, J. O. Bomansson

(in P. cuspidatum). Nyland: clay soil at Tavast Tull, Helsingfors, H. Lind

berg (in P. acaulon). New to Finland.

B. klinggraeffii Schimp. SWEDEN. Östergötland: Roxens strand, Lin

köping, 9.9.1887, E. Nyman (in Physcomitrella patens). Närke: Latorp,

Tysslinge, 30.10.1874, C. Hartman (in P. patens). Jämtland: on soil at edge of forest road 2 km north of Tandsbyn, Lockne, 10.8.1966. [Sk., Boh., Vg., Srm., Upl., Gstr.] NORWAY. Sör-Tröndelag: near Haakker, Opdal, 6.9. 1882, C. Kaurin (in P. patens). [Akh., Hord.] FINLAND. Kemi Lappmark: in argilla nuda, Sumbula, Rautus, 10.8.1897, H. Lindberg (in P. patens).

[Ah]

B. tenuisetum Limpr. DENMARK. Jylland: on heath soil, Tved, near

Ribe, 21.6.1863, F. Möller (in Entosthodon ericelorum). New to Denmark;

previously known from many localities in Germany and in Sweden.

B. micro-erythrocarpumC. M. & Kindb. SWEDEN. Södermanland, Utö: stony ground among rocks by the sea, north-east of Nasknäsudd, 21.7.1965; path in field near the church, 24.7.1965; sandy depression near the sea, Stora Sand, 25.7.1965. [Sk., Sm., HI., Boh., Vg., Ög., Dls.] NORWAY. Aust-Agder: Landvik 26.7.1891, F. E. Conradi (in Pleuridium alternifo- lium) (TRH). [VFld., Hord., Möre.]

B. rubens Mitt. SWEDEN. Närke: SSW. of Latorp farm, Tysslinge, 17.11.1957, N. Hakelier (in Astomum crispum). Västmanland: Odensvi,

6.5.1844, J. Ångström (in Phascum cuspidatum). [Sk., BL, Gtl., Sm., Vg., Ög., Dls., Vrm., Srm., Upl.] NORWAY. Östfold: Trondalen, Onsö, 17.5.1895, E. Ryan (in Pleuridium alternifolium) (TRH). Telemark: Falkumelv,

Gjerpen, Skien, 26.5.1886, N. Bryhn (in Pleuridium alternifolium) (TRH). Sör-Tröndelag: Charlottenlund, Strinda, 21.3.1914, J. Hagen (in Phascum

cuspidatum). [Akh., VFld.] FINLAND. Nyland: prata humida in fossa, Lojo, 9.6. 1891, H. Lindberg (in Pleuridium subulatum). [Al.] DENMARK. Fyen: Stenlöse Skov, 6.1901, H. F. Poulsen (in Astomum allernifolium). Lolland: in soli agri prope Sundby, 12.4.1895, C. Ostenfeld-Hansen (in Pleuridium allerni folium). Falster: Kohaven, Nyköbing, 11.4.1895, H. G. Simmons (in Pleuridium alternifolium) (TRH). [Mö., Sj.]

Rhynchostegiella compacta (C. Müll.) Loeske. FINLAND. Aland: on sea shore S. of Ytterby, Mariehamn, 22.7.1968. New to Finland. In fair quantity, associated with Amblystegium serpens, Poltia heimii and Bryum spp.

REFERENCES.

Crundwell, A. C. & Nyholm, Elsa, 1962: Notes on the genus Torlella. I. T. inclinata, T. densa, T. flavovirens and T. glareicola. — Trans. Rrit. Rryol. Soc. 4, pp. 187-193.

Hakelier, N., 1966: Ridrag till Sveriges mossflora. V. — Sv. Bot. Tidskr. 60, pp. 216-217.

Holmen, K., 1959: The distribution of the Bryophytes in Denmark. -

Bot. Tidskr. 55, pp. 77-154.

Krusenstjerna, E. von, 1964: Stockholmstraktens Bladmossor. — Stock

holm.

Persson, H., 1944: On some species of Aloina, with special reference to

their dispersal by the wind. — Sv. Bot. Tidskr. 38, pp. 260-268.

THE GENUS DATRONIA IN FENNOSCANDIA.

BY

LEIF BYVABDEN. Botanical Museum, University of Oslo.

The genus Datronia sensu Donk (Donk 1966) includes two species,

viz. D. mollis (Sommerf.) Donk and D. stereoides (Fr.) Byv., which both occur in Fennoscandia. This paper gives the exact distribution of the two fungi in Fennoscandia. In addition, some taxonomic questions are discussed. The discussion is based on the examination of material from the following institutions: Botanisk Museum, Copenhagen, Botaniska Museet, Gothenburg, Naturhistoriska Riks museet, Stockholm, Institutionen för systematisk botanik, Uppsala, Forest Research Institute in Finland, Helsinki, Institute of Phyto pathology, Helsinki, Botaniska Institutionen, Helsinki University, Helsinki, Oulun Museo, Oulo, Department of Botany, University of Turku, Turku, the botanical museums in Oslo, Trondheim, Bergen and Tromso, The Norwegian Plant Protection Institute and The Norwegian Forest Research Institute, both at Vollebekk, Norway. I thank the curators of these institutions for their kind cooperation. Mag. phil. Lalli Laine from The Finnish Forest Research Institute

in Helsinki has kindly forwarded me a list of material of D. mollis in The Finnish Institute of Phytopathology, Helsinki, and Dr. Yrjö

Mäkinen, Dept, of Botany, University of Turku has localized some Finnish placenames. I am indebted to both of them for their valuable help.

Datronia mollis (Sommerf.) Donk.

Basionym: Dsedalea mollis Sommerf. in Supplementum florae lapponicae

p. 271, 1826. Other synonyms: Trametes mollis (Sommerf.) Fries, Elenchus p. 71, 1828; Polyporus cervinus Pers., Mycol. Europ. 2: 87, 1825; Antrodia mollis (Sommerf.) Karsten, Medd. Soc. Faun, et Fl. Fenn. 5: 40, 1897.

Typus in Botanical Museum, Oslo.

Fig. 1. Datronia mollis (Sommehf.) Donk. Typus, about 0.8 x. y*,

Km,

mm

The name Polyporus cervinus Pers. is invalidated by Boletus cer-

vinus Schw., a pore fungus described in 1822 by Schweinitz in his

paper Synopsis Fungorum Carolinae superioris, Sehr. Natur- Gesellschaft zu Leipzig I p. 20-131. The identity of this fungus seems to be unclear (cf. Overholts 1953 p. 329).

Sommerfelt’s collection was done in Saltdalen, a valley in the

county of Nordland in Northern Norway (appr. 67° North, 15°30' East) in September 1822 on dead wood of Alnus incana and is shown on fig. 1.

D. mollis is a quite variable fungus, and the type covers this varia

tion very well as it includes some young specimens, with more or less entire pores, as well as one mature specimen with the typical somewhat lamellate and irregular pores. The hat is covered with a dark brown, fine tomentum, which some places along the edge has disappeared in thin and somewhat indistinct zones. The context is about 1-2 mm thick and light brown, towards the tomentum limited by a very fine dark line. The porelayer is 2—8 mm thick, umber- coloured in a lighter shade than the context. No spores could be

found.

D. mollis grows predominantly on dead wood of deciduous trees—

more rarely on living trees. From Fennoscandia I have seen no col- So. Bot. Tidskr., 62 (1968) : i

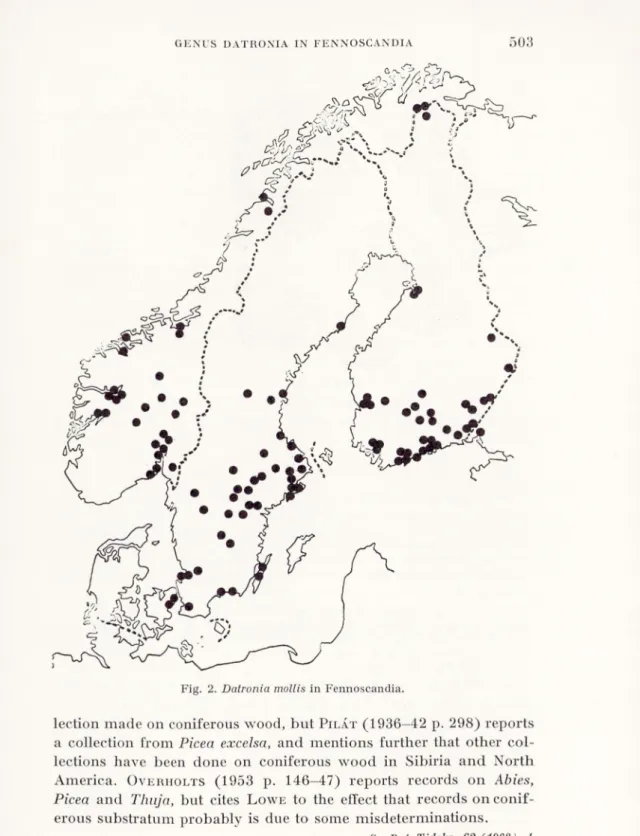

Fig. 2. Datronia mollis in Fennoscandia.

lection made on coniferous wood, but Pilat (1936—42 p. 298) reports

a collection from Picea excelsa, and mentions further that other col lections have been done on coniferous wood in Sibiria and North America. Overholts (1953 p. 146—47) reports records on Abies,

Picea and Thuja, but cites Lowe to the effect that records on conif

erous substratum probably is due to some misdeterminations.

Of 191 collections from Fennoscandia where the substratum was given, the following trees were represented :

68 collections on Populus tremula, 21 on Betula sp., 20 on Salix sp., 13 on Sorbus aucuparia, 13 on Prunus padus, 12 on Alnus incana, 8 on Corylus avellana, 6 on Alnus glutinosa, 5 on Fagus silvatica and

Acer platanoides, 4 on Fraxinus excelsior, 2 on Acer nigrum and Ulmus sp. and 1 on Quercus sp., Rhamnus frangula, Prunus avium, Malus sp., Primus cerasus and Amelanchier sp.

Fig. 2 shows the distribution of I), mollis in Fennoscandia. The fungus is obviously quite rare in Denmark. The few collections in the northern part of the area may be due to the poor mycological in vestigation of this area, some climatical factors may also be in volved.

D. mollis is a circumpolar plant known from France through

Central Europe and Sibiria to North America.

Pilat (op. cit. p. 298) mentions a collection made by Cooke in

New South Wales in Australia, but according to Cunningham (1965

p. 275), no specimens from the area could be found in the Kew her barium. Until further confirmation, D. mollis can not be regarded as a bipolar plant.

Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryvarden.

“Flora over Norges Kjuker” Universitetsförlaget p. 42. 1968.Basionym: Polyporus stereoides Fries in Syst. Mycol. p. 369, 1821.

Other synonyms: Polyporus planus Peck in Rep. New York State Mus. 31: 37, 1879; Trametes steroides var. kmetii Bres. in Atti R. Accad. Agiati III 3: 92, 1897; Coriolus planellus Murr, in Bull. Torrey Bot. Cl. 32: 649,

1906; Trametes kmetii (Bres.) Bres. in Ann. mycol. 18: 68, 1920; Polyporus planellus (Murr.) Overh. in Wash. Univ. Studies 3, 1: 29, 1915; Antrodia stereoides (Fr. per Fr.) Bond & Sing, in Ann. Mycol. 39: 61, 1941; Trametes epilobii Karst, in Notis. Sällsk. Fauna et Fl. Fenn. Förh. 9: 361, 1868;

Datronia epilobii (Karst.) Donk in Persoonia 4: 338, 1966.

Typus in Institutionen för Systematisk Botanik, Uppsala, Sweden. My combination Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. in Blyttia 25: 168, 1967, is due to an error not valid, and the combination was properly remade when “Flora over Norges kjuker” (Flora over the Nor wegian non resupinate pore fungi) was published by Oslo University

Press. Fries’ description of Polyporus stereoides in Syst. Mycol. p. 369 is this:

P. stereoides, pileo coriaceo pertenui pubescente zonata griseo poris minutis difformibus albis.

Proximus P. abietino. Vix csespitosus, tarnen imbricatus 1/2 unc zonis depressis concoloribus. Ad truncos abiegnos (v.v.).”

In his last paper where the fungus was mentioned, viz. leones selectaj Hymenomycetum nondum delineatorum (p. 86), the de scription was more detailed, and he also gave a picture of the fungus (pi. 187 nr. 3). Later the identity of the fungus was doubted, mostly due to the words “proximus P. abietino” (today very often called

Hirschioporus abietinus (Dicks, ex Fr.) Donk) and “ad truncos abiegnos”.

In his paper “Hymenomycetes of Lappland” (1912 p. 23), Romell reports several collections of I), stereoides from Northern Sweden and gives the following latin description of the fungus:

Coriaceus, tenuis vix 1 mm crassus, nunc totus resupinatus nuns effuso-reflexus, cervino-fuscus, nigricans, parte reflexa zonata, usque ad 3 cm. lata. Pori minuti, 4-5 per mm, pallide canescentes, sicut pruinati, intus dilatati, dissepimentis ad ora pororum crassis, ceterum tenuibus. Sporae hyalinae, oblongae, intus grumosae, 9-12 x3j-4

He also discusses the identity of P. stereoides Fr. and says in this connection:

This plant should probably be considered as the true and original Pol. stereoides of Fries. The name is well adapted as the habit very much

resembles a Slereum. It agrees exactly with a specimen from Femsjö in the herb, of Fries so named. The label is written by Rob. Fries, and Elias

Fries probably suggested the name or at least approved it, so that the

specimen can be held authentic. If this specimen were the only one, the question might be considered settled in spite of the statement ‘ad truncos abiegnos’ which may be correct, though more probably is a mistake since nobody else, so far as I know, has found this plant on conifers, but only on deciduous trees. There is, however, also another authentic specimen (with a label written by El. Fries himself) but this belongs to Pol. cervinus Pers. (Daedalea mollis Somm., Trameles mollis Fr.), a species which is really closely allied, though in my opinion specifically distinct ...”

In 1966 (p. 338) Donkrejected the name P. stereoides as a nomen

dubium and proposed Datronia epilobii (Karst.) Donk as a new

name. This name is based on Trametes epilobii Karst., a fungus Karsten described from Southern Finland (see above), and which

later authors (Romell 1912 p. 24, PilAt 1936-42 p. 299 and Lowe

1956 p. 122) have found synonymus with P. stereoides Fr., Donk

gives the following arguments in favour of his opinion:

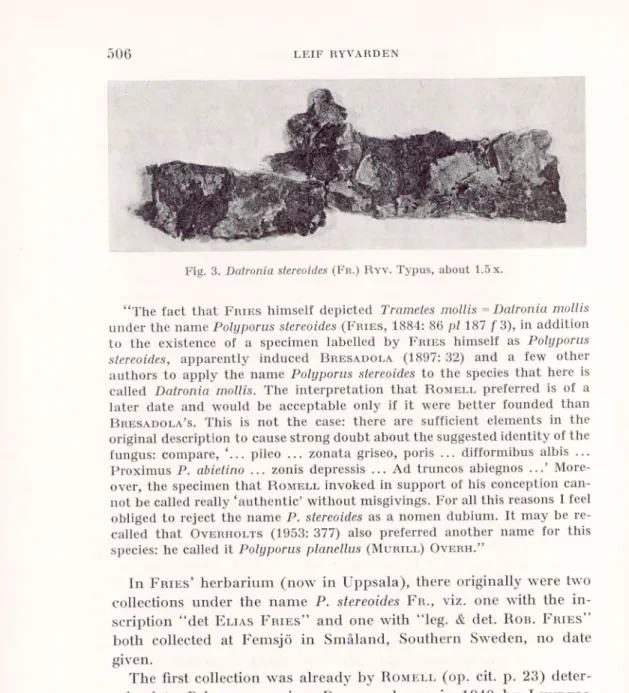

Fig. 3. Dalronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. Typus, about 1.5 x.

“The fact that Fries himself depicted Trameles mollis =Dalronia mollis

under the name Polyporus stereoides (Fries, 1884: 86 pi 187 f 3), in addition to the existence of a specimen labelled by Fries himself as Polyporus stereoides, apparently induced Bresadola (1897: 32) and a few other authors to apply the name Polyporus stereoides to the species that here is called Datronia mollis. The interpretation that Romell preferred is of a

later date and would be acceptable only if it were better founded than Bresadola’s. This is not the case: there are sufficient elements in the

original description to cause strong doubt about the suggested identity of the fungus: compare, ‘... pileo ... zonata griseo, poris ... difformibus albis ... Proximus P. abietino ... zonis depressis ... Ad truncos abiegnos ...’ More over, the specimen that Romell invoked in support of his conception can

not be called really ‘authentic’ without misgivings. For all this reasons I feel obliged to reject the name P. stereoides as a nomen dubium. It may be re called that Overholts (1953: 377) also preferred another name for this

species: he called it Polyporus planellus (Murill) Overh.”

In Fries’ herbarium (now in Uppsala), there originally were two collections under the name P. stereoides Fr., viz. one with the in scription “det Elias Fries” and one with “leg. & det. Rob. Fries” both collected at Femsjö in Småland, Southern Sweden, no date given.

The first collection was already by Romell (op. cit. p. 23) deter mined to Polyporus cervinus Pers. and was in 1940 by Lundell transfered from the sheet to Trametes mollis (Sommerf.) Fr.

The last specimen is a typical Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. and is shown on fig. 3. It is an old specimen whose hat is partly glabrous, and brown to grey, and partly minutely tomentose and dark brown with some narrow and indistinct zones. The contex is light brown, about 1 mm thick, while the porelayer is lighter brown (partly white with a brown tinge) and also about 1 mm thick. The pores are entire,

but somewhat elongated in random directions, 3-6 per mm. The context is separated from the tomentum on the hat by a very narrow dark line or zone. The spores are cylindrical to slight elliptical and hyaline. Three spores measured 11x3, 10x4 and 10x3 fx. The hyphae is non septae and thin, 1-1,5 [x thick.

The specimen is preserved on a bit bark which professor F. Roll- Hansen at The Norwegian Forest Research Institute at Vollebekk kindly has examined microscopically and concluded that it prob ably derives from a decidous tree (Roll-Hansen in litt.).

Hirschiporus abietinus (Dick, ex Fr.) Donk is normally covered with a white tomentum, and the pores are first violet to brown, later more pure brown. It is always found on dead, coniferous wood. Old and partly glabrous specimens of this fungus and of D. stereoides may, as far as my experience go, be confused, though a closer exami nation easily would reveal characteristic differences. Today, we may say that Fries’ comparison was not very good, probably due to the fact that he never saw more than the one specimen in his herbarium. This specimen was found and determined by his son Robert, but the father included the specimen in his collections without correc tions. This means that he had a clear concept of what he included within P. stereoides Fr. even if this also included D. mollis (Som- merf.) Donk. That he had a broader concept than accepted today, has, however, no influence on the taxonomic question discussed here.

I have seen no collection from Fennoscandia made on coniferous wood, neither does Pilat mention this type of substratum, but Overholts (1953: 378) mentions one collection from Thuja. Fries’ statement of “ad truncos abiegnos” is probably due to a misidentifi- cation of the substratum. This is quite understandable, as D. ste

reoides seems to prefer rotten wood, which often can be difficult to

determine without microscope. The other characters from Fries’ de scription given by Donkas “elements sufficient to cause doubt about the identify” viz. “pileo zonato griseo, poris—difformibus albis, zonis depressis”, are all characters which fall well within the normal range of variation for D. stereoides in Fennoscandia.

In leones selectse Hymenomycetum nondum delineatorum II (1877—84) pi. 187 nr. 3, there is a picture of P. stereoides Fr. Some authors (Pilat op. cit. p. 299 and Donk op. cit. p. 338) state the opinion that this picture shows D. mollis (Sommerf.) Donk. Per sonally, I am not sure, as no scale is given. It may be a small

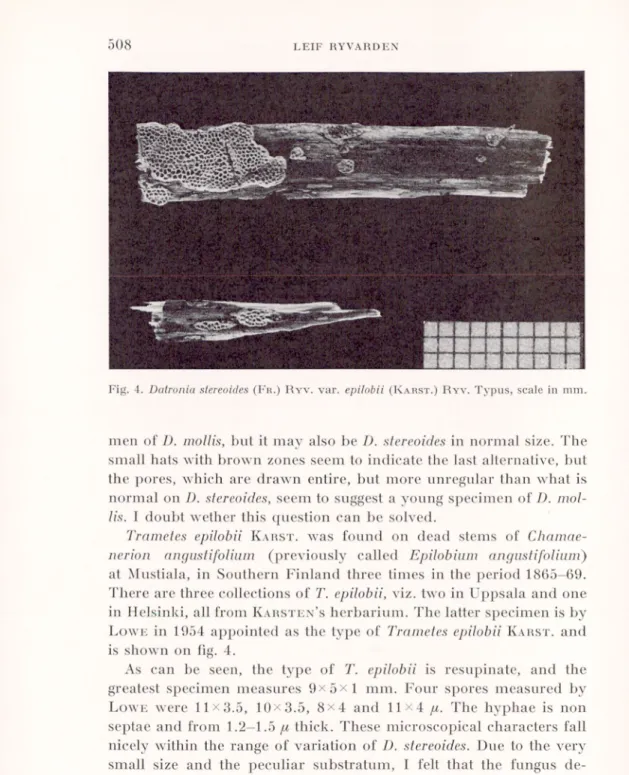

Fig. 4. Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. var. epitobii (Karst.) Ryv. Typus, scale in mm. MH ■i

Mi

'k ■i' BHHHImen of /X mollis, but it may also be I), stereoides in normal size. The small hats with brown zones seem to indicate the last alternative, but the pores, which are drawn entire, but more unregular Ilian what is normal on D. stereoides, seem to suggest a young specimen of D. mol

lis. I doubt wether this question can be solved.

Trametes epilobii Karst, was found on dead stems of Chamae- nerion angustifolium (previously called Epilobium angustifolium)

at Mustiala, in Southern Finland three times in the period 1865-69. There are three collections of T. epilobii, viz. two in Uppsala and one in Helsinki, all from Karsten’sherbarium. The latter specimen is by Lowe in 1954 appointed as the type of Trametes epilobii Karst, and is shown on fig. 4.

As can be seen, the type of T. epilobii is resupinate, and the greatest specimen measures 9x5x1 mm. Four spores measured by Lowe were 11x3.5, 10x3.5, 8x4 and 11x4

p

. The hyphae is nonseptae and from 1.2—1.5 p thick. These microscopical characters fall nicely within the range of variation of D. stereoides. Due to the very small size and the peculiar substratum, I felt that the fungus de served to be remembered and named it Datronia stereoides var.

epilobii (Karst.) Ryv. (Blyttia 1967, p. 168).

If we reject P. stereoides Fr. as nomen dubium, the fungus treated

Fig. 5. Datronia slereoides in Fennoscandia.

here should be called Datronia epilobii (Karst.) Donk (Donk 1966

p. 338), as Trametes epilobii is Ihe first valid name given the fungus after P. stereoides. The specimen shown on fig. 4 should consequently be the type.

We would in this case be forced to accept as the type the most untypical specimen imaginable. The type does not have any of the characteristics concerning the hat (the fine brown tomentum, the fine zones, partly tomentose, partly glabrous, the dark zone between the hat and the context etc.). Further, the pores will be untypical as they are poorly developed. Briefly, it should be difficult to find a specimen more untypical.

My conclusion is that even if there are some doubt concerning the identity of P. stereoides Fa., this doubt is not strong enough to justify a rejection of the name as nomen dubium. Further can be mentioned that if we accept P. stereoides Fr., we will have a fine and typical specimen from Fries’ own herbarium as the type. In addition, the name will be well adapted. Otherwise, we get a most untypical specimen as type and a name that is ridiculous.

Fig. 5 shows the known distribution of D. stereoides in Fenno- scandia. All collections have been done on dead wood of deciduous trees, and the following species are represented:

19 collections on Salix sp., 9 on Sorbus aucuparia, 4 on Betula sp., 3 on Populus tremula and 1 on Prunus padus, Corylus avellana and

Ribes glabellum.

As var. epilobii (Karst.) Ryv. on dead stems of Chamaenerion

angustifolium.

D. stereoides is a circumpolar plant, known from central and

northern Europe through Siberia to North America (Pilat p. 300

and Overiiolts p. 378). Pilat also mentions a collection (by

Cooke) from Australia, but according to Cunningham (1965 p. 281)

this is due to a misidentification.

Summary.

This investigation shows that Datronia mollis (Sommerf.) Donk

in Fennoscandia is rare in Denmark and north of the Polar Circle, more common in between. All documented records from the area are made on deciduous wood, usually dead wood, more rarely on living trees. Of the 19 host species represented, Populus tremula is the most common as more than 50 % of the collections are done on this tree.

Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. was described by Fries in Systema

mycologicum, but the description was short and included some words which have caused doubt about the identity of the fungus. In Fries’s

herbarium there were two collections named Polyporus stereoides.

One collection which already Romell(1912) determined to D. mollis

(Sommerf.) Done, and one which is a very typical D. stereoides (Fr.) Ryv. The last collection was made and named by Robert

Fries, but Elias Fries included the fungus in his collection without

any comments, which indicate that he had a clear concept of what he included in Polyporus stereoides, even if his concept was broader than accepted today.

Done (1967) has rejected P. stereoides Fr. as nomen dubium and proposed Datronia epilobii (Karst.) Done, based on Trametes

epilobii, a fungus Karsten found on dead stems of Chamaenerion

angustifolium. Later authors have found this fungus to be synonymous

with P. stereoides Fr. Though there might be some doubt concerning the identity of P. stereoides Fr., my conclusion is that this doubt is not strong enough to justify a rejection of the name as nomen dubium. Consequently, I consider the typical specimen from Fries’s her

barium as being the type of Datronia stereoides (Fr.) Ryv.

D. stereoides is rare in Fennoscandia and is only found on dead

deciduous wood. 50 % of the collections are done on Salix spp., then follows Sorbus aucuparia (25 %) and Betula spp. (8 %).

REFERENCES.

Cunningham, G. H., 1965: Polyporaceae of New Zealand. — Dep. Sei. Ind.

Res. Bull. 164.

Donk, M. A., 1967: Notes on European Polypores I. •— Persoonia 4: 337-343.

Fries, E., 1821: Systema mycologicum. — Lund».

—»—, 1874: Hymenomycetes Europaei. — Upsali®.

—»—, 1875-84: leones select» Hymenomycetum nondum delineatorum II. — Holmise et Upsali».

Lowe, J., 1956: Type studies of the polypores described by Karsten. —

Mycologica 48: 99-125.

Overholts, L. C., 1953: The polyporaceae of the United States, Alaska and

Canada. •— University of Michigan press. Ann Arbor.

Pilat, A., 1936-42: Polyporaceae. Atlas des Champignons de l’Europe. —

Praha.

Romell, L., 1911: Hymenomycetes of Lappland. —- Arkiv f. Bot. 11, no. 3.

Ryvarden, L., 1967: Flora over Norges kjuker. — Blyttia 25: 137-216.

—i)—, 1968: Flora over Norges kjuker. — Universitetsförlaget, Oslo.

SMÄRRE UPPSATSER OCH MEDDELANDEN.

Föreningens medlemmar uppmanas att till denna avdelning insända meddelanden om märkliga växtfynd o. d.

Utbredningen av Eleocharis acicularis och E. parvula på

strandängslokaler vid den svenska norrlandskusten.

Under mina pågående undersökningar av strandängslokaler vid norr landskusten, har jag gjort ett stort antal nyfynd av flera submersa arter, av vilka jag nu bara skall redogöra för de två små Eleocharis-arternas före komst.

Eleocharis acicularis är en sötvattensart, som har förmågan att tränga in i bräckt vatten, medan E. parvula är en utpräglad brackvattensart. Detta medför att E. parvula får en nordgräns i Östersjön, medan E. acicularis får en sydgräns, beroende på salthaltsgradienten i Östersjön.

Fig. 1 visar fördelningen av de fynd jag gjort av de bägge arterna på strandängslokaler, varvid de, som tagits upp i den efterföljande förteck ningen, faller utanför de punktmarkeringar, som gjorts i Hultén (1950). Eleocharis parvula är en i östra Svealand lokalt mycket vanlig art, som förekommer ännu i norra Uppland (Almquist 1929). I Gästrikland saknas

den dock helt, förutom alldeles vid Upplands-gränsen, vilket sannolikt be ror på att gynnsamma växtlokaler saknas och inte på att området är dåligt undersökt, vilket Hylander (1966) lämnar som möjlig orsak till en del utbredningsluckor för arten. I Hälsingland återkommer arten på tre loka ler, varav två nära Hudiksvall (Samuelsson 1934) och en vid Mellanfjärden

(ny). Samuelsson (op. cit.) påpekar, att av de finländska observationerna

av arten att döma borde den svenska nordgränsen inte på långt när vara nådd. Redan några år senare rapporterar också Samuelsson (1937) arten

från fiskeläget Skatan vid Björköfjärden, Njurunda k:n i Medelpad. Egen domligt nog tar inte Hylander (1966) upp denna observation. Av den an

ledningen sökte jag speciellt noga efter arten vid Björköfjärden och fann den också vid Vikarbodarna, någon kilometer norr om Samuelssons lokal. Björköfjärden har länge varit landets nordligaste lokal, men Samuelsson

(1937) ansåg, att arten borde finnas även i Ångermanland, även fast han då inte hade funnit den där. 1967 fann jag dock E. parvula på två lokaler i Ångermanland (se förteckningen).

Den nuvarande nordgränsen i Östersjön går vid ca 3.5 %. salthalt, i trakten av Gamla Karleby (Segerstråhle 1957). Luther (1951) anger, att E. parvula förekommer ned till 3 %, i Ekenäsområdet. Samuelsson (1934)

föreslår, att högre vattentemperatur på finska sidan skulle betinga den nord ligare förekomsten där (jfr Hultén 1950, karta 300).

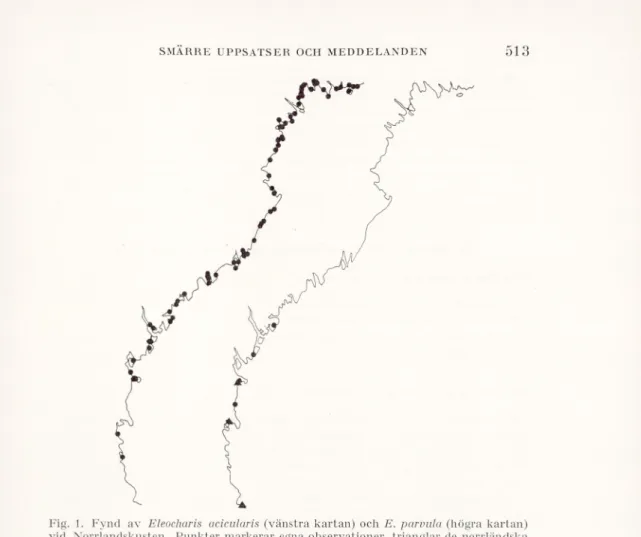

Fig. 1. Fynd av Eleocharis acicularis (vänstra kartan) och E. parvula (högra kartan) vid Norrlandskusten. Punkter markerar egna observationer, trianglar de norrländska

observationer av E. parvula, som medtagits i Hultén(1950).

Observations of Eleocharis acicularis (left) and E. parvula (right) at the Swedish Both- nian coast. Black points indicate my own observations, triangles observations of

E. parvula in Hultén(1950).

Den lägsta salthalten jag uppmätt på någon E. parvula-\oka\ är 4.4 %„. För flera Östersjö-växter gäller samma förhållande, att nordgränsen på den svenska sidan går vid en högre salthalt än vid den finska, trots att den svenska nordgränsen ligger betydligt sydligare (Segerstråhle 1957). Den svenska nordgränsen betingas säkerligen av såväl salthalt och temperatur som brist på lämpliga växtlokaler inom artens möjliga utbredningsområde och artens spridningsmöjligheter. Strömmarna i Östersjön löper moturs, vilket för diasporer norrut vid finska sidan och söderut vid svenska.

Eleocharis acicularis fördrar ett mer sandigt underlag än E. parvula, man kan t. o. m. finna arten på rent sandunderlag, men bestånden är då glesa. Den högsta salthalt jag uppmätt på någon acicularis-lokal är 5.3 men Luther (1951) anger att arten i Ekenäsområdet går över 6 %, och en ligt Wi instedt (1943) skulle sydgränsen i Östersjön vara Nexo på Born

holm. Normalt ligger salthalterna på acicularis-lokalerna dock under 4 %«.

På de lokaler där arten förekommer, är den ofta ymnig, speciellt på mindre finkornigt underlag, där den mer högvuxna vegetationen ej tagit överhanden. På de allra mest utsötade lokalerna i nordligaste Bottenviken är E. acicularis något mindre ymnig just p. g. a. konkurrensen från den högvuxna vegetationen. E. acicularis växer ofta tillsammans med andra submersa växter som Subularia, Limosella, Crassula, Elatine spp., Isoetes spp. och Polamogeton spp. E. parvula förefaller att oftare förekomma i enartssamhälle, åtminstone att döma av observationer i östra Svealand.

Nya fyndorter för

Eleocharis acicularisoch

E. parvula. Eleocharis parvula (6-8 aug. 1967).1. Mellanfjärden, Harmångers k:n, Hls. 2. Södra Fällviken, Ytterfälle, Säbrå k:n, Ång.

3. Omnefjärden vid Omne, Nordingrå k:n, Ång. Ny för Ångermanland (herb. Wallentinus nr 315).

Eleocharis acicularis (15 juli 1967 -15 aug. 1968).

1. Nordmalings k:n, Ång (Nordmalingsfjärden, 4 lokaler): Nordmalings- fjärden vid E4, Rundvik, Rönnholm och Skåpet.

2. Umeå stad, Vb (1 lokal): Strömbäck.

3. Holmsunds köping, Yb (2 lokaler): Obbola fritidsområde och Bredvik S om Obbola.

4. Bygdeå k:n, Vb (6 lokaler): Rovågern (2 lokaler) och Täfteå vid Täfte- fjärden, samt Stuguviken N om Brednoret, Rickleå och Sikeå.

5. Nysätra k:n, Yb (1 lokal): Gumboda hamn.

6. Lövångers k:n, Vb (2 lokaler): Lövångersnoret och Kallviken.

7. Skellefteå stad, Vb (5 lokaler): Risböle, Burviks hamn, Harrbäcksand, Selsvik och Kinnbäck.

8. Piteå stad, Nb (5 lokaler): Jävre, Nötön, Borgarudden, Harrbäcks- fjärden (Håkansö) och Trundön.

9. Nederluleå k:n, Nb (6 lokaler): Mörön, Alhamn, Bensbyn, Örarna, Brändön och Sundom.

10. Råneå k:n, Nb (4 lokaler): Mjöfjärden, Kängsön, Strömsund och Rörbäck.

11. Kalix k:n, Nb (8 lokaler): N om Siknäs, Töre, Törehamn, Törefors, Rånäsudden, Storö hamn, Vånafjärden vid E4 och Lappbäcken.

12. Haparanda stad, Nb (1 lokal): Granvik på Seskarö.

Summary. The distribution of Eleocharis acicularis and E. parvula on

Bothnian shore-meadows.—During 1967 and 1968 I observed the two Eleocharis species on the localities indicated in fig. 1. Some of them are new and these are listed above. Eleocharis parvula has now its northern limit in Ångermanland, where this species is not observed earlier.

LITTERATURFÖRTECKNING.

Almquist, E., 1929: Upplands vegetation och flora. — Acta phytogeogr.

Suec. 1.

Hultén, E., 1950: Atlas över växternas utbredning i Norden. — Stockholm.

Hylander, N., 1966. Nordisk kärlväxtflora II. — Stockholm.

Luther, H., 1951: Verbreitung und Ökologie der höheren Wasserpflanzen im Brackwasser der Ekenäs-Gegend in Südfinnland. I. Allgemeiner Teil. — Acta Bot. Fenn. 49.

Samuelsson, G., 1934: Die Verbreitung der höheren Wasserpflanzen in

Nordeuropa (Fennoskandien und Dänemark). — Acta phytogeogr. Suec. 6.

—»—, 1937. Nya nordgränser för Typha angustifolia L. och Scirpus parvu- lus R. et S. — Sv. Bot. Tidskr. 31: 430-432.

Segerstråhle, S. G., 1957: Baltic Sea. — Geol. Soc. America, Mem. 67:

751-800.

Wiinstedt, K., 1943: Cyperaceernes Udbredelse i Danmark. I. Scirpoideae.

— Bot. Tidsskr. 47: 3-94.

Hans-Georg Wallenlinus. Botaniska Institutionen, Stockholms Universitet, S-104 05 Stockholm 50

Usnea longissima Ach. found in north-western Spain.

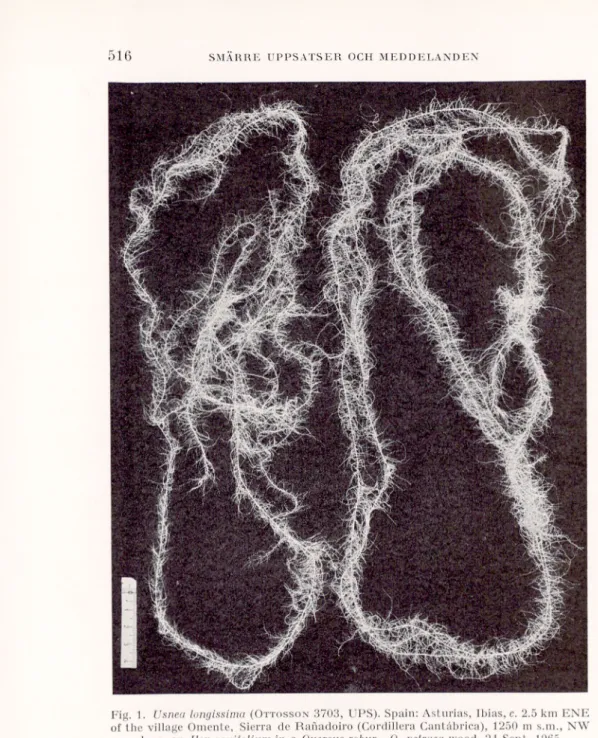

In 1965 and 1967 I stayed in the western part of the Cantabrian Moun tains, north-western Spain, for the purpose of studying the morphology and ecology of Quercus robur L. and Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl. During my ex

cursions I also collected other plants and on two localities I found the lichen Usnea longissima Ach. (Fig. 1). This species is very rare in Europe

and seems not to have been collected on the Iberian Peninsula before. The statement by Låzaro e Ibiza in his Flora (1906; 1920, pp. 460-461) that it

should occur at Siete Picos in Sierra de Guadarrama (central Spain), where the woods consist of Pinus silvestris L., is obviously incorrect. I could not find the species there during two visits in October 1967 and the search for material from Sierra de Guadarrama in the herbaria of Madrid (MA and MAF) did not give any result. Nor is it reported from Spain or Portugal by Ahlner (1931, pp. 404-408; 1948, p. 97), Motyka (1936-1938, pp. 427-432),

Keissler (1958-1960, pp. 665-669), Gams (1961, p. 168, and Map 3). The finds of Usnea longissima were made in the south-western corner of the province of Asturias, north-western Spain. The mountains here belong to Sierra de Ranadoiro, an offshoot from the western part of the Cantabrian Mountains (Cordillera Cantåbrica) and running almost in the direction of S to N.

One locality is situated c. 2.5 km ENE-NE of Omente, 1250-1300 m s.m., on a NW-W slope. The species occurred very abundantly on one Ilex

. aw y27"v%»l

mWrå

W;. t-v»j --8J»jäÉP «$

Jpi» ,Sk/aSFig. 1. Usneci longissima (Ottosson3703, UPS). Spain: Asturias, Ibias, c. 2.5 km ENE

of the village Omente, Sierra de Ranadoiro (Cordillera Cantåbrica), 1250 m s.m., NW slope, on Ilex aquifotium in a Quercus robur—Q. pelraea wood, 24 Sept. 1965.

Photo F. Hellström.

folium and one Quercus robur, about 1-1.5 m long parts of the thallus hang ing down freely from the tree branches.

The other locality lies c. 1.5 km NE of Valdebuyes, 1300 m s.m., on a SW slope, where the species was collected on a Quercus robur.

Omente and Valdebuyes are two small isolated villages in Ibias (concejo) 8 km from each other. (Mapa topogräfico de Espana a escala 1:50,000. Nos. 75 and 100.)

The woods on the localities are mainly formed by old oaks with a diameter of about 0.2-1.2 m. Traces of cutting are rare, but many trunks have been damaged by fire. On the uppermost parts of the slopes (here up to 1400 m) the stands are formed by Quercus robur. There various Usnea spp. are very abundant. Lower down on the steep slopes Q. pelraea becomes common and constitutes the woods. Besides, numerous oaks have a more or less inter mediate morphology, and are obviously of hybrid origin. On more shady places, e.g. ravines, Ilex aquifolium is rather frequent. Betula pubescens Ehrh. and Sorbus aucuparia L. also occur. From the shrub and field layer

were noted: Rubus sp., Genista florida L., Sarothamnus scoparius (L.) Wimm., Rhamnus frangula L., Hedera helix L., Erica arborea L., Vaccinium mijrtillus L. (often as epiphyte several meters up in old oaks), Lonicera periclymenum L., Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott, Asphodelus albus Mill., Erythronium dens-canis L., Luzula silvatica (Huds.) Gaud., Arrhenalherum elatius (L.) M. &K. ssp. bulbosum (Willd.) Hyl., Deschampsia flexuosa (L.) Trin., Holcus mollis L., Anthoxanthum odoratum L., Slellaria holostea L., Arenaria montana L., Anemone nemorosa L., Cory- dalis claviculata (L.) DC., Saxifraga umbrosa L., Oxalis acetosella L., Teu- crium scorodonia L., Linaria triornithophora (L.) Willd., Digitalis purpurea L., Melampyrum pratense L., Jasione montana L., Solidago virgaurea L.

In addition to Usnea longissima I also collected the following lichens from trunks and branches (the determinations made by Dr. Rolf Santes-

son, Uppsala): Sphaerophorus globosus (Huds.) Vain., Lobaria pulmonaria (L.) Hoffm., L. scrobiculata (Scop.) DC., Nephroma laevigatum Ach. ( =Ar. lusitanicum Schaer.), Ochrolechia tartarea (L.) Mass., Pseudevernia furfu- racea (L.) Zopf, Hypogymnia physodes (L.) W. Wats., H. tubulosa (Schaer.) Havaas, Parmelia sulcata Tayl., Platismatia glauca (L.) W. Culb., Evernia prunastri (L.) Ach., Alectoria implexa (Hoffm.) Nyl., A. jubata (L.) Ach., A. sarmentosa (Ach.) Ach., Ramalina farinacea (L.) Ach., R. pyriformis (Nyl.) Mot., Usnea spp.

The specimens of Usnea longissima collected by me were sterile, which is almost always the case in this species (cf. e.g. Keissler, 1958-1960, p. 665).

The climate in north-western Spain is pronouncedly oceanic. The atmo spheric humidity is especially high at higher levels in the mountains due to considerable precipitation (about 1500 mm or more) and frequent mist. As a consequence, the epiphytic lichen vegetation is rich.

Gams (1961) emphasizes the great importance of the mist for the occur

rence of Usnea longissima in mountain regions and characterizes it as a con tinental mist lichen. His map of its distribution in Europe is shown in Fig. 2. The position of the new area, the westernmost in Europe, is denoted with an open ring.

Usnea longissima seems only to grow where the tree stands are old and nearly intact. According to the literature the majority of the finds of this species in Europe have been made on conifers, especially Picea abies (L.) H. Karst, and Abies alba Mill., but quite a few on deciduous trees, e.g. Fagus

Euronci

Fig. 2. The distribution of Usnea longissima in Europe, after Gams, 1961, with addi tion of the two new adjacent localities in north-western Spain (within O). The two lo

calities in the Pyrenees are situated on the French side (cf. Motyka, 1936-1938, p. 427).

silvatica L. In Fennoscandia it has almost exclusively been observed on Picea abies (Ahlner, 1931; 1948).

In the western part of the Cantabrian Mountains, where the bedrock is mainly silicious, the woods or remains of woods are dominated by Quercus robur L., Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl., Q. pyrenaica Willd., or Fagus silvatica

L., according to habitat conditions. Especially on north-facing mountain slopes at high altitudes (about 1200-1700 m) Betula pubescens Ehrh. (B.

celtiberica Rothm. et Vasc.) is frequent, often forming small woods. Be

sides, Taxus baccata L., Corylus avellana L., Sorbus aucuparia L., Ilex aqui- folium L., and Acer pseudoplatanus L. occur. There are no indigenous conifers, except the low shrub Juniperus communis L. var. montana Ait.

(J. nana Willd.). As a rule the villages are surrounded by old plantations of Castanea saliva Mill., which grows on ground once covered by Quercus woods. Furthermore, by human activity the original forests (mainly of Quercus spp.) on the slopes have been destroyed over vast areas and replaced by extensive heaths. The following are the most important heath-forming species: Erica arborea L., E. australis L. ssp. aragonensis (Wk.) P. Cout., E. cinerea L., E. umbellata L., Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull, Genistella triden- tata (L.) Samp., Ulex minor Roth.

Material (from the locality near Omente) has been distributed to the fol lowing herbaria (abbreviations according to Lanjouw & Stafleu, 1964): BC, BM, C, H, LD, LISU, MA, MAF, O, PC, S, SANT, UPS, and UPSY.

Acknowledgement. I wish to thank Dr. Rolf Santesson, Institute of

Systematic Botany, Uppsala, who kindly verified the determination of Usnea longissima and determined the other lichens mentioned in the text.

Resumen. La Usnea longissima Ach. hallada en el noroeste de Espana. — Recolecté este liquen, que es muy raro en Europa, en dos sitios durante excursiones en 1965 y 1967 enla parte occidental de la Cordillera Cantåbrica (sudoeste de Asturias). Su existencia no ha sido conocida con certeza en la Peninsula Ibérica anteriormente. Låzaro e Ibiza, en la segunda y tercera

edicion de su Flora (1906; 1920) cita la Usnea longissima de Siete Picos (Sierra de Guadarrama), creciendo sobre Pinus silvestris. Sin embargo, esto ultimo es incorrecto, puesto que la busqué alii en octubre de 1967 pero sin poder encontrarla.

REFERENCES.

Ahlner, S., 1931: Usnea longissima Ach. i Skandinavien. Med en översikt av dess europeiska utbredning. (Mit deutscher Zusammenfassung.) — Svensk Bot. Tidskr. 25 (1931). Uppsala.

—»—, 1948: Utbredningstyper bland nordiska barrträdslavar. (Verbrei tungstypen unter fennoskandischen Nadelbaumflechten.) Diss. — Acta Phytogeogr. Suecica 22. Uppsala.

Gams, H., 1961: Usnea longissima Ach. als kontinentale Nebelflechte. —

Ber. Geobot. Inst. ETH Stiftung Rübel 32 (1960). Zürich.

Keissler, K. von, 1958-1960: Usneaceae. In Rabenhorst, L.: Krypto- gamen-Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Bd 9. Abt. 5: 4. — Leipzig.

Lanjouw, J. & Stafleu, F. A., 1964: Index Herbariorum. 1 The herbaria

of the world, ed. 5. — Regnum Vegetabile 31. Utrecht.

Låzaro e Ibiza, Blas, 1906: Botånica descriptiva: Compendio de la Flora

espanola. Segunda edicion. — Madrid.

—»—, 1920: Botånica descriptiva: Compendio de la Flora espanola. Tercera edicion. — Madrid.

Motyka, J., 1936-1938: Lichenum generis Usnea studium monographicum.

Pars systematica. — Leopoli.

Ivar Ottosson. Institute of Ecological Botany (Yäxtbiologiska institutionen), University of Uppsala.

Fynd av Sonchus palustris L. i Bohuslän.

Att Sveriges största ört har kunnat framleva en sommar i oskyddat läge bara 10 meter från allmän landsväg utan att veterligen ha observerats av någon botanist är ägnat att förvåna. Vid foten av det tvåstammiga exemplar som undertecknad i medio av juli d. å. upptäckte, ligger nämligen fjolårs- exemplarets välbevarade stammar. Årets strandtistels ena stam är 2,6, dess andra 2,3 meter hög. Diametern vid basen 25 resp. 20 mm. Samman lagda antalet holkar är ca 200. Blomningen började den 20 juli och pågick i slutet av augusti ännu för fullt. Flertalet blommor ha gått i frukt och fruk terna ha spritts för vinden.

Detta praktexemplar av Sonchus palustris står i den övre sötvattenpå- verkade delen av strandängen vid den inre norra delen av Styrsvik vid Åbyfjorden norr om Lysekil. Lokalen ligger ca 10 meter från landsvägen Brodalen Slävik mitt emot gården Styrsvik.

Strandängen synes betraktas som impediment. Den varken slås eller betas. Den inbjuder inte till strandhugg, ty viken utanför är mycket lång grund med lerig botten. Mellan stranden och fyndplatsen finns en mindre vassrugge, men här finns ingen strandtistel. Följande arter ha noterats i den nivå där strandtisteln står:

Juncus effusus och Filipendula ulmaria (dessa båda äro dominerande), Lythrum salicaria, Iris pseudacorus, Achillea ptarmica, Epilobium palustre, Senecio viscosus, Potentilla anserina, Cirsium vulgare, Galeopsis bifida, Lycopus europaeus, Angelica silvestris, Rumex crispus, Peucedanum palustre, Calystegia sepium, Mentha arvensis, Ranunculus acris, Holcus lanatus och närmaste anförvanten Sonchus arvensis.

I början av augusti hade jag nöjet få visa lokalen för lektor Svante

Suneson, som ägnat stor uppmärksamhet åt de svenska förekomsterna av Sonchus palustris. I Sunesons i Bot. Not. 1946, H. 1, lämnade samman

ställning för arten i Sverige nämnes bland odlade förekomster Björkbacken i Ödsmål i Bohuslän. Avståndet härifrån till Styrsvik är fågelvägen ca 40 km. Jag besökte i början av september framlidne trädgårdsdirektör E. Almqvists dotter, fru Jochnick på Björkbacken. Sonchus palustris har

hållit sig kvar där. Två utblommade exemplar observerades vid mitt besök. År 1959 upptäckte tullkontrollör Folke Lundberg (Sv. Bot. Tidskr. 53

(1959): 4) en förekomst av Sonchus palustris vid Tjolöholm i Halland samt omnämnde en norsk förekomst (sedan 1956) nära Kristiansand på Vest- landet. Styrsvikslokalen ligger mellan dessa båda men är uppenbarligen yngre.

Det vore onekligen intressant att veta, varifrån frukten har kommit till den nya lokalen, men härom kan aldrig något med säkerhet utrönas. Yad man däremot kan konstatera är att frukten i Styrsvik funnit gynnsamma växtbetingelser och vuxit upp till en planta av imponerande mått.

Vargön den 21 september 1968.

Sigge Bergh.

Ny lokal för Neottia nidus-avis på Frösön i Jämtland.

Vid ihärdigt letande efter skogsfrun, som enligt uppgift skall finnas på norra sidan av Frösön, några hundra meter väster om Hjälmtorpet, träffade jag helt oförmodat på några enstaka exemplar av Neottia nidus-avis, som växte intill en stig. Ett större bestånd på cirka 25 ex. fanns då (omkring 1 aug. 1966) intill en glänta i skogen, 15 meter från stigen, växande under några stora granar.

Även 1967 återfanns nästroten på denna lokal i ungefär samma antal och på exakt samma platser.

1968 fanns inga exemplar på dessa platser; däremot växte på motsatta sidan av stigen (cirka 40 meter om den gamla platsen) ett bestånd på 26 blommande Neottia nidus-avis. Samtliga stod tätt tillsammans under 5 stora granar, vilka bildade en cirkel. I en glänta intill fanns ytterligare 10 exemplar, också dessa stående i klunga, och intill stigen 2 exemplar till. Bland de blommande exemplaren stod fjolårets med torra kapslar.

Skogen består på platsen av höga granar, här och var växer små gråalar (Ainus incana). I gläntorna växer Aconitum septentrionale, Anemone he- patica, Viola mirabilis, Geum rivale, Fragariavesca, Linnaea borealis, Majan- themum bifolium, Luzula pilosa, Carex Halleri, C. ornithopoda och Lastrea dryopteris. Dessutom 1 ex. av Coeloglossum viride. I vegetationen under granarna: lingon samt 2 ex. Coeloglossum viride. Mossor: Ptilium crista- castrensis, Hylocomium splendens samt Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus.

Normalt är denna del av skogen fuktig, men i år är även här mycket torrt på grund av den intensiva torkan sommaren 1968.

Beläggexemplar av nästroten är insänt till Riksmuseets Botaniska Sektion, Stockholm.

Den gamla lokalen för Neottia nidus-avis anges till Mällbyn, Frösön; denna lokal skulle ligga strax ovanför nuvarande Lövsta-badet i en skogs dunge, där emellertid nästroten ej finns längre. Platsen är starkt besökt bl. a. på grund av två skidbackar samt det nya Lövsta-badet, vilket kan förklara nästrotens försvinnande.

Skogsfrun har jag dock ännu ej funnit på Frösön. Frösön den 29 juli 1968.

Lars Thofelt.

RECENSIONER.

Flora of the Queen Charlotte Islands. Part 1. Systematics of the Vascular Plants. By James A. Calder and Roy L. Taylor. 660 pp.

Price $12.50, in foreign countries 13.65. Do., Part 2. Cytological Aspects of the Vascular Plants. By Roy L. Taylor and Gerald A. Mulligan. 148

pp. Price $7.50, resp. 8.30. — Canada Department of Agriculture, Research Branch, Monograph No. 4, Part 1 and 2. Ottawa 1968. Available by mail from the Queen’s Printer, Ottawa.

Queen Charlotte Islands, 156 miles (about 260 km) in length, compose a triangular archipelago consisting of some 150 islands off the coast of British Columbia between the latitudes 52°N and 54°N. The land area is about 3600 sq.miles (about 9300 sq.km) which is mostly made up of the two large islands Graham I. and Moresby I. Three zones can be distinguished: a small lowland area at the NE corner of Graham I., a central plateau, and a south western mountainchain, with peaks up to 3-4000 feet (920-1200 m) sloping steeply to the Pacific Ocean down to a depth of approximately 10,000 feet (3000 m).

The oldest rocks are Triassic limestones. In the Cretaceous period the islands may have been crudely outlined in their present shape.

The woods are similar to those of the adjacent mainland and southeastern Alaska with Tsuga heterophijlla, Thuja plicata, Picea silchensis, and Pinus conlorta in varying proportions, and at higher elevations also Chamaecyparis noolkatensis and especially Tsuga mertensiana. As stunted trees occur to the summits of the mountains, a high-alpine zone is missing.

The Flora includes 476 indigenous and 118 introduced taxa of vascular plants, of which no less than 136 occupy a more or less circumpolar range, a further 89 are American-Asiatic and 242 are American. Grasses dominate with 68 taxa, sedges total 51, while Composites are 42, Rosaceae 31, Ranun- culaceae 25, Juncus and Saxifraga 21 each.

The first botanical collections in these islands were made as late as 1878, and up to the 1950s only about a dozen collectors had visited them, mostly accumulating small collections. In 1957-1964 Calder, Savile and Taylor, partly accompanied by the bryologist Schofield, made an intensive survey

of the flora bringing together about 5500 numbers and 25,000 sheets from all parts of the Archipelago. These collections form the main base for the Flora, published as Part 1 of the total work. The main part of my review will deal with this volume.

The chapter dealing with the climate is very comprehensive, 39 pages. It is questionable whether the vegetation can be expected to respond to the Su. Bot. Tidskr., 62 (1968):

h-very sudden and local climatic variations along with the h-very large varia tion from year to year within such a minutely dissected mountainous area, 55 miles (90 km) across the north, 30 miles (48 km) in the middle and only a few miles in the south. Still the authors regret the small amount of data from the west side and the lack of data from the interior. The summers are very cool and the winters very mild. Strong winds and cloudy skies prevail. The autumn and early winter is rainy, and precipitation varies from 40-50 inches (100-125 mm) to 200-300 inches (5000-7500 mm). Agriculture is restricted to a few farms.

The chapter on plant communities commences with the statement: “We have found no simple answer to the problem of clearly defining the plant communities on the Queen Charlotte Islands.” This is really to be regretted, it would have been an universal sensation for biologists and phytogeo graphers the world over!

The chapter contains a conventional description with enumeration of species on sand and shingle beaches, salt marshes, mires, bogs or rock and cliff communities, forest communities and “montane communities” and so on, with no attempt at a closer analysis. A number of black and white photographs give a good idea of the nature of the area as do some of the coloured photographs. Many of the latter are, however, not of the quality that warrent publication. Those of Silene acaulis (p. 330) and Potentilla villosa (p. 403) are unrecognizable, not to mention others! It is a pity as coloured plates are expensive.

In the introduction to the chapter “Phytogeography” the authors write: “The difficulties inherent in the taxonomic and geographic delimitation of taxa that are widely distributed in the circumboreal and circumpolar zones are nowhere more explicitly evident than in such works as Hultdn’s, The Circumpolar Plants, Part 1, and The Amphi-Atlantic Plants. Many of the distributions are inaccurate on a regional basis, and others, especially in their central and eastern Asiatic sectors, are based on too few records for accurate depiction of ranges.”

These sentences reveal the inability of the authors to understand the nature of phytogeographical mapwork and to read and interpreat such maps.

It is a field where a continuous flow of new information constantly leads to development and refinement. In the above works an attempt has been made to provide a base for further work by summarizing the knowledge now available. Very few botanists would be willing to take the trouble to consult the more than thousand botanical works on which the maps in these works are founded. The present writer has never dreamt of providing final maps which can not be further developed. On the contrary they are meant as a base for further additions and corrections. The opinion about the ranges in Eastern Asia and Central Siberia is most remarkable, and has not been shared by Russian critics. Practically all sources that have been available from these areas have been used, actually 257 of them only for “The Amphiatlantic Plants”, not to mention studies in herbaria (also Russian) and three years of field experience in Eastern Asia. The main features will only very excep tionally be changed. The criticism concerning Eastern and Central Asia is So. Bot. Tidskr., 62 (1968) : 4

the more surprising as the authors of the Queen Charlotte Islands Flora have never worked with Asiatic plant geography, nor have quoted a refer ence to a single Russian work dealing with that flora.

The same inability to interpret phytogeographical maps is demonstrated for instance in the discussion of the species Triglochin palustre (p. 177). The authors write: “Hultén (1962, p. 113, Map 104) has mapped this species as occurring in three separate areas in western Canada. His distribution pat- perns are unrealistic as this species is widely distributed throughout central British Columbia, Mackenzie District, Saskatchewan and Alberta.” These authors do not understand that the facts given in the maps are the dots, the actual places where the plant is known to occur. The reader can thus judge for himself. The lines encircling the dots are intended to help the reader to summarize them quickly and to express the map writers proposition as to the reasonable actual range of the plant.

In the case of Triglochin palustre the intention of these lines is to indicate that the species does not occur in the high mountains and that it may have one southern and one northern area in Western America as is the case with so many other plants. It must be doubted that it occurs throughout Mac kenzie District, Saskatchewan and Alberta. In Breitungs’ Saskatchewan Flora (1957) it is said to be “Occasional in bogs” and two localities in the southern part of the province are mentioned.

It is to be regretted that the extensive collections from interior British Columbia made by Calder and others have not been published. British

Columbia is actually one of the least known areas of corresponding size in the boreal belt. It is the task of the Canadian botanists to survey it and publish the result.

In the chapter on Phytogeography the authors write "... a detailed analysis of the circumboreal and circumpolar zones is still not possible”. The truth of this categoric declaration depends on what is meant by “de tailed”. It is easy to ask for just a little more than is possible. What we know today can doubtless be used as a basis for many phytogeographical dis cussions. It has long been customary to discuss without knowledge of even the most crude distributional facts.

On p. Ill we can read: “Our botanical investigations of the flora of the Pacific Northwest support the geological evidence that the Cordilleran ice sheet extended to the southern, northern and eastern boundaries of British Columbia at the time of maximum Wisconsin glaciation, but we have re servations as to the extent of glaciation in the Queen Charlotte Islands.” This is certainly no understatement. The authors do not seem to realize that such decisions are extremely complicated and hardly solved in a trice! The conditions in Scandinavia are actually very similar to those in British Columbia. There they have been discussed during well 100 years and not yet settled definitely. The geologists say that Scandinavia was completely overridden by ice during the last glaciation, but the botanists maintain that there must have been refugia. Geologists suppose that also Queen Charlotte Islands have been completely covered by ice, and here again the botanists don’t agree. It would have been appropriate to compare the two cases. The comprehensive Scandinavian literature could have provided clues.

The authors claim 11 endemic species to Queen Charlotte Islands. An examination of them from two viewpoints is necessary! How different are they from their closest relatives; and how can we know that they really are endemics? They are discussed below.

1. Calamagrostis purpurascens ssp. tasuensis. Judging from description and drawing (figs. 110-113), this plant is very similar if not identical with the population of C. purpurascens subsp. arctica occurring from the Beering Sea to Japan. It seems to represent the southernmost extention of that taxon, beeing consequently of somewhat more luxurient growth than spe cimens from the exposed Bering Sea islands. C. purpurascens is by the way an extremely variable species.

2. Lloydia serotina ssp. flava. Taller, up to 40 cm and with yellow or green instead of purplish veins of the sepals. Such specimens were not seen in Alaska or any other part of the worldwide range of this species.

3. Salix reticulata ssp. glabellicarpa. Specimens with adult capsules glabrous were collected by the reviewer at Juneau. Apparently a weak endemic.

4. Isopyrum Savilei. One of the best taxa claimed as endemic. 5. Saxifraga Taylori. One of the best taxa claimed as endemic.

6. Geum Schofieldii. Most probably the hybrid G. calthifolium x Rossii. Not rare in the Aleutian Islands. Described as Sieversia macrantha by Kearney.

7. Viola biflora ssp. carlottae. Differs from the typical “phase” by blunt sepals, ciliate only in the upper half, prominently marked with purple mid- stripe, and large flowers and seeds. A Viola of biflora type with sepals answering to this description and with fairly large flowers was collected at Craig by I. L. Norberg. As it has stolones it was interpreated as V. semper- virens by the reviewer. It seems reasonable that it is the same plant as V. biflora ssp. carlottae.

8. Cassiope lycopodioides ssp. cristapilosa. As pointed out in the reviewers recent paper “Comments on the flora of Alaska and Yukon”, the leaves are tipped with hairs even in the type specimen of C. lycopodioides. There can thus at most be a quantitative difference from the typical plant.

9. Mimulus guttatus ssp. haidensis. This taxon is distinguished by more acute stemleaves and pedicels which are short-hairy, lacking capitate glands. The form of the stemleaves is variable. In the Aleutian Islands many specimens, especially those from exposed habitats, lack glands on the pedicels as do some specimens from SE Alaska. In many specimens the pubescence of the pedicels is a mixture between the two types. Very weak as an endemic.

10. Pedicularis Pennellii ssp. insularis in the reviewer’s opinion is P. parviflora J. E. Sm.

11. Senecio Newcombei. Judging from the drawing p. 544 it is practically identical with specimens which occur within the very variable population of S. resedifolius from the unglaciated Bering Sea area. The two plants should be carefully compared. No specimen of S. Newcombei has been available to me for examination.

These views, whether accepted or not, show at least that there is a lot to discuss around the “endemics”. To say that the endemics constitute 4.5 per cent of the flora (p. Ill) is apparently misleading.

With regards to this viewpoint: how can we know that the so called endemics really only occur on the Queen Charlotte Islands? It must be em phasized that the outer coast of southeastern Alaska from Cross Sound to the southern boundary of the state as well as the coast of British Columbia south to the southern end of Vancouver Island has not in a single place by far been subject to such intense botanical survey as Queen Charlotte Islands. The few places from which occasional collections have been made are chiefly close to the shore. How can the authors be sure that their “endemics” do not occur somewhere on this more than 800 miles (1300 km) long botanically unsurveyed or poorly known coast?

Furthermore, the refuge theory must be discussed in connection with the fluctuation of the sealevel during the climatical changes of the quaternary period. Once it was lowered as much as 400 feet (135 m).

The above considerations do not mean that Queen Charlotte Islands can not have been a refugium but that they may well be the only part of a larger coastal area where plants can have survived the last glaciation. The present knowledge doesn’t allow such categoric conclusions to be drawn as the authors of the flora have done.

On p. 114 the authors express the opinion that many questions for instance if the “endemics represent end products of speciation as a result of insular isolation or represent remnants of more wide-spread preglacial taxa” probably never will be answered. The reviewer is more optimistic! Pollen analyses and other micropaleontological methods will help a lot, as will age determinations of fossil remains or even a closer study of the variation within the present populations.

In the systematic part of the Flora the families are in systematical order but the genera within each family in alphabetical order, which is somewhat bewildering, as closely related genera sometimes are placed far apart. The species names are supplied with author references, but only with selected synonyms that have been used in earlier reports from the islands or the adjacent mainland. No taxonomic description is given to the species “be cause many of our taxa are represented by only a few specimens”. Instead “we have concentrated our study on the interspecific and intraspecific relationship of each taxon”. This apparently means critical remarks on other authors’ treatment of the group concerned, together with a report on its appearence on the islands in question. In a number of cases these re marks need to be commented upon.

Sparganium minimum. It is surprising that this species is reported as common. It is very rare in Alaska. The confused discussion under S. simplex seems to indicate that the determinations of Sparganium taxa should be reconsidered.

Scirpus caespitosus. The authors write: “Although there are slight differ ences between the lowland and northern-alpine populations of S. caespilosus from Europe, we have not seen a large enough series from the Old World to