Urban Studies

Master’s (Tow-Year) Thesis 30 Credits

Autumn Semester 2019 Supervisor: Jonas Alwall

Perceived Residential Environment Quality

in Relation to Gender

An Exploratory Study in Lindängen, Malmö

i

Perceived Residential Environment Quality in Relation to Gender

An Exploratory Study in Lindängen, Malmö

Elahe Shams

MALMÖ UNIVERSITY

FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis

Supervisor: Jonas Alwall

ii

Abstract

This master’s thesis deals with some concepts and theories related to public space and everyday life and points to how neglecting women’s needs and preferences in public spaces can lead to the formation of gendered urban spaces which prevent women from earning their right to the city. Concepts such as quality of life, quality of place, living environment, residential perception and satisfaction, and place attachment overlap and have many interrelations. One cannot consider, for example, the quality of residential environment independent of residential satisfaction or ignore its influence on the quality of life. This study focuses specifically on the perception of residential

environment quality, in the medium scale (neighborhood).

Despite a wide range of studies in the field of perceived residential environment quality, the review of literature reveals that studies in this field lack sufficient attention to power relations which among others (cultural, ethnic, etc.), can be gender related. Given the mentioned issues, this study explores women’s perceptions of residential environment quality in the Lindängen neighborhood in Malmö, Sweden. Drawing upon the analysis of a questionnaire, the study presents four scales of REQ in which women’s perceptions have been different from men’s: Recreational services, Safety, Public furniture and Commercial services. In the next stage, a set of semi-structured interviews were done with five women living in the neighborhood. These interviews explore the way women’s ideas and perceptions about their neighborhood, more specifically about the four aforementioned scales, affect their daily lives.

The findings of this study highlight the influence of the residential environment quality on everyday lives of women and indicates their different needs for urban facilities and infrastructures (such as recreational or commercial services, as this study indicates) as compared to men.

Keywords: Perceived residential environment quality, Gender and right to the city, Everyday life of women, Neighborhood, Lindängen.

iii

Table of Content

Abstract ... ii

Table of Content ... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... v

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. Research Objectives and Questions ... 3

1.2. Review of previous research ... 4

1.2.1. Perceived Residential Environment Quality ... 4

1.2.2. Gender and residential perception ... 8

1.2.3. Summary of literature review ... 9

1.4 Layout of the paper ... 10

2. THEORY ... 11

2.1. The Importance of Public Spaces ... 11

2.2. Place and social construction of space ... 13

2.3. Everyday Life and Right to the City ... 14

2.4. Gendered public spaces - Women’s right to the city ... 16

3. METHODOLOGY ... 19 3.1. Research Design ... 19 3.2. Participants ... 20 3.3. Measures ... 21 3.3.1 Questionnaire: ... 21 3.3.2 Interview ... 23 3.3.3. Photographic observation ... 24 3.4. Limitations... 25

4. PRESENTATION OF OBJECT OF STUDY ... 26

iv

4.1.1. Statistics summary ... 28

4.1.2. Buildings (residentials) development history ... 29

4.2. Projects & social Places ... 30

4.3. The image of Lindängen from the eyes of an outsider ... 31

5. PRESENTATION OF DATA AND ANALYSIS ... 33

5.1. Discriminative scales ... 33

5.1.1. Recreational Services and Stimulating vs. Boring ... 34

5.1.2. Safety ... 37

5.1.3. Public furniture and cleanliness ... 39

5.1.4. Commercial Services ... 41

5.2. Non-Discriminative Scales ... 41

5.3. Analytical conclusion ... 42

6. DISCUSSION ... 44

6.1. Research questions ... 44

6.2. The image of Lindängen from the eyes of an insider... 46

7. CONCLUSION ... 48

Some suggestions for further research ... 49

8. REFERENCES ... 50

9. Appendices ... 54

9.1. Questionnaire – English ... 54

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Jonas Alwall for providing invaluable guidance and advice throughout writing this thesis and also for his continuous encouragement even when the road got tough. Further, I would like to thank the academic crew of Urban Studies department for providing the valuable learning opportunities.

Thanks to all residents in Lindängen, especially all the women who kindly participated in this research.

My special thanks

to Mattias, Olivia and Sahar for their help and kindness, and

to my dearest sister Armaghan, for providing me with unfailing support during my years of study in Malmö.

vi

‘The response to environment may be primarily aesthetic: it may vary from the fleeting pleasure one gets from a view to the equally fleeting but far more intense sense of beauty that is suddenly revealed. The response may be tactile, a delight in the feel of air, water, earth. More permanent and less easy to express are the feelings that one has toward a place because it is home, the locus of memories, and the means of gaining a livelihood’.

1

1. INTRODUCTION

The interaction and relationship between society and space in the discipline of urban planning and the extent to which individuals and collective social behavior is determined by the geographical or physical characteristics of the built environment has been debated widely before. by many scholars (Shirazi, 2018). Urban environments, like the entire world they belong to, are experienced and evaluated according to their relatively objective features, although these experiences are also influenced by people’s subjective traits, expectations, and needs (Dębek M. , 2014). The way people feel about their city, their neighborhood and their housing, is part of their life experience. Thus, the characteristics of the built environment and its perceived quality has impact upon the quality of life.

Environmental quality is a container concept; different theories relate to different aspects of environmental quality, and the concept is multi-dimensional (Kamp, Leidelmeijer, Marsmana, & Hollander, 2003). Researchers who worked on perceived environment quality acknowledged that theoretical analyses and empirical studies on these fields, traditionally examined place of residence on the three levels – the city, neighborhood, and home (Bonaiuto, Aiello, Perugini, Bonnes, & Ercolani, 1999; Fornara, Bonaiuto, & Bonnes, 2010). In this study the focus will be on residential environment at the medium level: the neighborhood, rather than at the level of smaller (home) or larger scale places (the city). Neighborhood is an important social and spatial scale at which urban life takes place, but it is not a bounded space; it is rather one among many urban spatialities (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). “Neighborhood” and “community” denote concepts popular with planners and social workers. They provide a framework for organizing the complex human ecology of a city into manageable subareas; they are also social ideals feeding on the belief that the health of society depends on the frequency of neighborly acts and the sense of communal membership (Tuan, 1974). As Carp and Carp (1982) state, an extensive literature on the behavior of persons within their neighborhoods shows important relationships between where behaviors take place and people’s satisfaction with activities, and between activity patterns and overall environmental satisfaction. They also mention the possibility that characteristics of the neighborhood affect

2

perceived health and satisfactions with friendships, with work, with the financial situation and, possibly, even with marriage, all of which in turn have impacts upon perceived quality of life. The chosen neighborhood of this study is the Lindängen area, in the city of Malmö. Like many other parts of Malmö, Lindängen has undergone a rapid population growth and expansion especially during 1960’s and 1970’s. In recent years, a great deal of planning work on the renewal of the center of Lindängen has been carried out. Malmö city's various administrations, property owners and many residents have been involved in this process, which in the next few years will result in more housing, the construction of a new school and the establishment of a public square. In this study, I approach neighborhood not just as a bordered and defined district, but rather as a social relations, meetings and interactions. As Tuan define it. In this sense Lindängen has a strong sense of neighborhood concept due to different reasons; firstly, the geographical borders of the area are quite distinct, and the area is separated from its surroundings. Secondly, the quantity of social activities is high in this area, and it has created a social bond between residents. The neighborhood, in the same sense, can be understood as community, identified with a bounded place, ‘able to exist because of the intimacy of face- to- face communication’ (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). As Maurice Merleau-Ponty demonstrates, what we perceive through our bodies are not only things but also ‘interspaces between things’ (2012, p. 35). What this means is that in perceiving through our bodies, we form syntheses in our everyday activities as a means of linking together a great multiplicity of objects to form spaces (Löw, 2006 ).

Finding women’s needs and preferences, as a large group of users of public space, should be studied and be the subject of research and design as well. As Gardner (1989) also states, gender should be considered as a significant and underappreciated social category in public places. Starting from women’s everyday practices and experiences enables us to explore how these are defined by engendered social relations and structures and also how women’s everyday actions (re)produce and (trans)form these relations and structures (Smith 1988, cited in Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). Gardner (1989) points out the importance of looking at public places from a feminist point of view not only to understand how women behave in public places, but more fundamentally to understand the nature and substance of public places in the first place. It was in the 1980s that feminist geography became more than an occasional curiosity and took its place as

3

a firm part of the geographic curriculum (McDowell, 1993). Traditional studies from Doreen Massey and Linda McDowell have drawn upon time-geography as a method of studying everyday life (Hägerstrand 1985). Time-geography offers a different view of time in relation to spatial contexts as it proceeds through the notions of ‘paths’ and ‘projects’—i.e. positions, movements and activities of individuals in time and space. This perspective has been taken up by many researchers of everyday life, particularly in Scandinavian countries (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). Many explorations have been made of what a “nonsexist city” might look like and how cities might differ if they were designed equally for men and women (see, for example, Hayden, 1980). These remain important insights, but many questions raised remain underexplored.What accounts may help us to understand the ways in which women are able to access the city and the role of planning in supporting these processes? How can a focus upon the everyday help us in understanding the gendered mediation of space? Yasminah Beebeejaun (2017) suggests that a greater engagement with everyday spatial practices provides critical insights into how claims to urban space and the exercise of rights are inherently gendered.

In this paper, I approach the urban from an everyday life perspective and look at the ways in which the urban environment and perceived quality of it define and shape women’s everyday practices and their different uses of space. Thus, I focus on the relationship between inhabitants' perceptions of residential environment quality in the scale of neighborhood, through a gender perspective. The research aims to address women’s needs and preferences, to identify the existing barriers and open the way to finding solutions for optimizing the quality of their current environment. There can be many factors which affect the perception of environment by women in different ways than men since their needs and preferences can differ.

1.1. Research Objectives and Questions

This research is a path of discovery. I intend to contribute to the empirical research area by exploring the residential environment quality perceived by women in Lindängen, Malmö.

4

• How do women’s perceptions of their residential environment in Lindängen relates to:

- Men’s perceptions of the neighborhood?

- The daily life experiences of the women in the neighborhood?

1.2. Review of Previous Research

Concepts such as livability, living quality, living environment, quality of place, residential perception and satisfaction, the evaluation of the residential and living environment and quality of life do overlap and are often used as synonyms – but may every so often also be contrasted (Kamp, Leidelmeijer, Marsmana, & Hollander, 2003). According to Dębek & Janda-Dębek, non-uniform definitions of quality of life, quality of environment, residential satisfaction, and numerous other concepts cause fundamental ambiguities as to how these phenomena can be measured and gauged (Dębek & Janda-Dębek, 2015). It is not possible to give a thorough review of all approaches, definitions and models within this paper, and instead I will focus on quality of residential

(neighborhood) environment and the perception of it. The research interests of this paper stem

from the concern to understand women’s perception of urban environment and its effects on their everyday life and their actions and presence in public spaces. The objective, then, is to gain insight into which concepts are needed to investigate residential environment considering women’s perspectives. In this regard, I present the literature review under two subtitles: residential environment quality and, its perception through a gender lens.

1.2.1. Perceived Residential Environment Quality

Mulligan, Carruthers and Cahill (2004) interpret QOL (quality of life) as the satisfaction that a person receives from surrounding human and physical conditions that are scale-dependent and can affect the behavior of individual people or groups (Marans & Stimson, An Overview of Quality of Urban Life, 2011). Marans and Stimson believe this definition more accurately reflects quality of urban life (QOUL), rather than QOL (Marans & Stimson, 2011). An example of a model based on this approach is the residential satisfaction model of Marans and Couper (2000), in which a distinction is made between different scale levels: house, neighborhood and city (Kamp,

5

Leidelmeijer, Marsmana, & Hollander, 2003). Marans and his collaborators (Marans & Rodger, 1975; Lee & Marans, 1980 and Connerly & Marans, 1985) have built on the seminal work by Campbell, Converse and Rodgers (1976) to explore the objective–subjective relationships in investigating Quality of Urban Life (QOUL), asserting that the quality of a place or the geographic setting at various levels of scale is in fact a subjective phenomenon and that each person occupying that setting might differ in their views about it (Marans & Stimson, 2011).

Neighborhood satisfaction, which refers to residents’ overall evaluation of their neighborhood environment, has long been a major research subject in sociology, planning, and related disciplines (Hur, Nasar, & Chun, 2010). The quality of the urban environment (and of the residential environment in particular) is a key factor influencing people’s overall quality of life (Bonaiuto & Fornara, 2017). Very few studies have dealt with the behavioral component of residential satisfaction (mostly in terms of intentions to move from the present residence), whereas the cognitive and the affective dimensions have been studied in greater depth. The latter aspects are grasped by two important constructs that are strictly related to, and partly overlapping with, residential satisfaction: place attachment and perceived residential environment quality (PREQ), respectively (Bonaiuto & Fornara, 2017). The perceived residential environment quality has represented a topic of great interest in environmental psychology research (Fornara, Bonaiuto, & Bonnes, 2010). Residential quality is a multidimensional construct focusing on different specific aspects of a place such as spatial features, human features or functional features. People who live in the neighborhood (residents) have daily experience of it, and therefore it is vital to understand their opinions and points of view about the place. A subjective evaluation of a place of residence is formed by the interaction of the residents’ traits and their multidimensional assessment of the place’s physical quality (Dębek & Janda-Dębek, 2015). Yet, spaces are not static sites but animated by physical characteristics, history, location, time of day or week, season, or the presence of other people (Beebeejaun, 2017). As Tu and Lin (2008) state, the scales or factors of residential environment quality identified by most studies have been based on experts’ views of residential environmental quality, and may therefore only reflect partial, not holistic, evaluative structures of the residential environment quality perceived by residents. Many scholars believe that residents’ perceptions of their environment differ substantially from experts’ in their appraisals of the

6

environment (Bonnes, Uzzell, Carrus, & Kelay, 2007; Hur, Nasar, & Chun, 2010; Nasar, 1989; Tu & Lin, 2008).

Among existing studies, some scholars have conducted repetitive emprical studies to define the scales and factors of percived residential environment quality (PREQ) and to verify the capacity of the instrument in discriminating between different cities and residential environments (Bonaiuto, Aiello, Perugini, Bonnes, & Ercolani, 1999; Bonaiuto, Fornara, & Bonnes, 2003; Bonaiuto, Fornara, & Bonnes, 2006; Bonaiuto, Fornara, Ariccio, Ganucci Cancellieri, & Rahimi, 2015). In one of their first studies, Bonaiuto et al., focused more on the issue of the multidimensionality of residential satisfaction, preparing a Residential Satisfaction Scale (RSS) articulated in 20 dimensions, covering specific aspects of spatial, social, functional, and contextual features. In that instrument, residential satisfaction was operationalized in terms of a large set of very specific items, each one addressing a single feature of the neighborhood, rather than directly asking for a single general evaluation of satisfaction with the neighborhood. The operationalization of residential satisfaction was aimed at measuring subjects' perception of their residential environment (i.e. subjective indicators of urban quality), rather than measuring global residential satisfaction (e.g. `How satisfied are you with your neighborhood?' or `How would you define your neighborhood as a place to live?') (Bonaiuto, Aiello, Perugini, Bonnes, & Ercolani, 1999). Later the authors developed the questionnaire Perceived Residential Environment Quality & Neighborhood Attachment (PREQ & NA) indicators (Bonaiuto, Aiello, Perugini, Bonnes, & Ercolani, 1999) which were used in different ways by many scholars. (Bonaiuto et al. 1999, 2003, 2006, 2015). This questionnaire is one of the first PREQ & NA questionnaires which comprised 126 statements concerning perceived residential environment quality and is a popular and oft-cited international instrument for measuring people’s perceived urban environmental qualities (Bonaiuto, Fornara, & Bonnes, 2003; Tu & Lin, 2008). Following in-depth qualitative explorations and theoretical deliberations, Bonaiuto et al. (1999) established 11 significant thematic scales for evaluating residential environment dimensions: (1) architectural and town-planning space, (2) organization of accessibility and roads, (3) green areas, (4) people and social relations, (5) punctual social-health-assistance services, (6) punctual cultural-recreational services, (7) punctual commercial services, (8) non-punctual (in-network) services (transportation), (9) lifestyle, (10) pollution, and (11) maintenance/care. These scales reflect positive-negative perceptions of specific

7

environmental qualities of the neighborhoods in which respondents lived (Dębek & Janda-Dębek, 2015).

Fornara et al. (2010) presented an abbreviated version of PREQ, called the Abbreviated Perceived Residential Environment Quality Indicators (PREQI), doing research in various neighborhoods of eleven cities in Italy. In this article, the territorial unit of analysis is the neighborhood, which can be considered as a link between home and city levels in people’s perceptions and actions toward the residential environment. The PREQIs are included in eleven scales, which cover the four macroevaluative dimensions of residential quality. More specifically, the dimension of architectural/urban planning features is covered by the scales Architectural and Urban Planning Space, Organization of Accessibility and Roads, and Green Areas; the dimension of sociorelational features is covered by one scale (named exactly Sociorelational Features); the dimension of functional features is covered by the scales of Welfare Services, Recreational Services, Commercial Services, and Transport Services; the dimension of context features is covered by the scales of Pace of Life, Environmental Health, and Upkeep and Care. In another studies, Michał Dębek, Bożena and Janda-Dębek made a Polish adaptation of this model with 66 item (Dębek & Janda-Dębek, 2015) and Tu and Lin (2008) used these scales to investigate how Taipei City residents assess the quality of their residential environment in high-density and mixed-use settings. Craik and Zube (1976), stress that “A truly comprehensive assessment of environmental quality would include an appraisal of the quality of the experienced environment” (as cited in Carp & Carp, 1982, p. 296). Marans and Stimson (2011) suggested that the residents view of quality of environment would reflect each individual’s perceptions and assessments of a number of setting attributes that could in turn be influenced by certain characteristics of the occupant, including their

past experiences. Those past experiences thus represent a set of standards against which current

judgments are being made. Those judgments include other settings experienced by the resident of a place, and they also include their aspirations. Addition to these, I believe other factors can also affect these experiences. Different groups of society (ethnic, age, gender, etc.) can experience their surrounding environment differently and thus, have different perception of their living environment. Gender, for example can affect the individual’s perception of environment based on personal experience, social norms or historical memory.

8

1.2.2. Gender and residential perception

The feminist critique of urban theory and planning that developed in the 1970s demonstrated how urban planners have created gendered environments that are predominantly suited to the needs of men and the heteronormative family (Beebeejaun, 2017). As extensive theoretical and empirical research has shown, women’s experiences and their daily lives are different from men’s and so is their use and perception of the urban environment (Vaiou D. , 1992). Literature on “gendered space” and “spatiality of gendered space” argues that urban spaces is spatially encoded with ideas of gender (Massey 1994; Scraton & Watson 1998; Beebeejaun 2017; Shirazi 2018). Carol Brooks Gardner (1989) in her critical work on Goffman’s theory of everyday life (Goffman, 1956), correctly points out that the sociology of everyday life has provided concepts for and ways of looking at public places that did not faithfully represent the place of women, nor of disadvantaged groups like minorities and the disabled. She proposes that analyses of interaction in public places, like other elements of social interaction, cannot be presumed to be gender neutral (Gardner, 1989). Genderization of space is affected by the individual’s perception of environment and the power of this perception on their actions and presence in public spaces. In their paper, Vaiou and Lykogianni (2006) discuss everyday life in urban neighborhoods from a feminist perspective. They state that everyday life is connected to places where women and men live, work, consume, relate to others, forge identities, cope with or challenge routine, habit and established codes of conduct—i.e. neighborhoods, understood as one important urban spatiality, among many.

Different factors relating to perception of environment have been investigated by many researchers. However, the review of previous research demonstrates that there are very few studies investigating gender related environmental perception. In the scale of city, Scraton and Watson (1998) studied on the city of Leeds in order to explore how women perceived Leeds as a city, what the city meant to them and how they used this ‘24-hour city’. The authors state that the women in their study, in many ways, continue to be marginalized from public city leisure and continue to create their own meanings and opportunities much as many women have done in local communities and in private spaces.

In another study by Frances M. Carp and Abraham Carp (1982), authors investigate the perceived environmental quality of neighborhood and developing assessment scales and their relation to

9

gender along with age. More focused on the age factor, they conclude that environmental characteristics are positively related to age. After stating that some gender differences were observed in their research, the authors believe that the importance of these differences should not be stressed, since gender differences are usually not difficult to find in psychological research, and differences in three of 15 scales suggests a modest role. They reduce the reasons of such differences by stating that “the tendency of women to be more concerned about their safety is understandable in view of their generally smaller size, lesser strength, and more meager preparation as well as physical capacity to fight or flee” (Carp & Carp, 1982). I believe, contrary to the aim and the title of this study, the authors haven’t been able to provide an appropriate gender analysis of the context. As an example, they ignored the power relations and social structures of fear and have simply reduced these issues to an individual level by connecting it to one’s strength or ability of defending themselves.

1.2.3. Summary of literature review

Most of the studies explored have been more concerned with measuring the residential satisfaction levels, and identifying important predictors of residential satisfaction and defining relevant scales to measuring perceived qualities, than understanding how or why different residents perceive their residential environment quality in different ways (by cognitive models).

Based on the literature review there is a gap in the studies regarding gender perspectives; although a plethora of past research has studied residential environment quality perception, fewer studies have delved into subjects like how different groups of people have different perception and experience the environment differently. As Beebeejaun also points out, gender, class and ethnicity divides are virtually absent from the studies of environment perception, a flaw that inevitably leads to a confirmation of existing social hierarchies and urban orders (Beebeejaun, 2017). These studies rarely can be considered comprehensive. In other words, it is highly possible that the ‘factors’ or ‘dimensions’ of residential environment quality extracted from such surveys, could only depict the reality partially, not comprehensively, and that they represent a privileged group’s perspective.

10

1.4. Layout of the Paper

Having reviewed the literature and framing the research questions, this thesis continues as follows: In the next chapter, I will present the most important theories and concepts which have helped me frame this paper. Based on the research objectives, I mainly focus on theories about space and the social construction of it, and women, right to the city and everyday life. In Chapter 3, I describe the methodologies I have used during the field work and explain how different methods have been used to gain a sufficient amount of data. In Chapter 4, I will provide a brief description of the case study (the Lindängen area in Malmö), followed by a presentation of data and analysis of data in

Chapter 5. The data will be analyzed considering aforementioned theories, concepts and literature.

In Chapter 6, I will discuss more about the results of the data analysis. I share reflections and observations considering the main aim and objectives of the study and will answer the research questions. At the end, after presenting a concluding summary in Chapter 7, will end this paper by suggesting some potentials for further research. References and appendices will be provided in chapters 8 and 9.

11

2. THEORY

In this chapter I present the theoretical concepts that shape the structure of this paper. The study seeks to investigate the different perceptions of residential environment quality between women and men and its possible effects on women’s everyday life in public spaces. In this regard, I will present the theoretical concepts in three main parts: First, I discuss the importance of public space, mentioning different types of activities that can take place in public space, as defined by Jan Gehl. Then I discuss about the social construction of space, everyday life and at the end women and the concept of The Right to the City in relation to gendered public spaces.

2.1. The Importance of Public Spaces

There is a connection between urban spaces and the everyday life of citizens. This connection can only be formed in order to meet the basic needs and daily activities of citizens, or in a better situation can be a context for shaping social actions and interactions, relaxation or enjoyment. In his work, Life between the buildings: using public space (2006), Jan Gehl highlights the importance of the life in public spaces and investigates the interaction between the physical environment and different activities that take place in outdoor public spaces. He also discusses basic outdoor activities such as walking, standing, sitting, seeing, hearing and talking, and their spatial characteristics (Shirazi, 2018). According to Jan Gehl (2006), a vibrant city is where its public spaces have different functions. He emphasizes that the attractiveness of an urban space can be gauged by the mass of people who gather in its public space and spend their time there. He divides people’s activities in the urban space into the three categories of necessary (functional),

optional (recreational), and social activities, and emphasizes that these activities occur in an

intertwined pattern and each require different properties in the built environment (Shirazi, 2018). The first type of activities that Gehl names are “necessary activities.” These activities extend from people’s use of space via walking. Examples include everyday tasks, such as walking to work or school, getting the mail, or walking a dog (www.1). Gehl claims that these activities would occur

12

in every type of weather and at any time of the year as participants have no choice but to engage in this category of activities. So, the necessary activities take place regardless of the quality of the physical environment and thus, it has the least impact on these activities among the three types (Gehl, 2006).

The second type of activities Gehl identifies are “optional activities,” which occur when there is a desire to participate in these activities and a time and a place favorable to participating in them. Examples include sitting outside or jogging. Unlike necessary activities, optional activities are unlikely to occur in poor weather, but rather, when outside conditions are optimal, for instance, when the weather is favorable. The frequency of optional activities is also dependent on the non-weather-related environment (www.1). In dense urban settings of low-quality optional activities exist at a minimum level. However, in a good physical environment, optional activities occur with high frequency (ibid.). In a nutshell, the better a place is, the more optional activities occur.

“Social activities” are the third way in which people animate public space. Social activity occurs spontaneously when people meet in a particular place. Like when people congregate in a place and socialize (www.1). These activities include children playing, friends coming together to converse, and simply, passersby briefly acknowledging each other, seeing and hearing other people. As mentioned before, these activities are often spontaneous in nature and can occur in a wide variety

Increasing the social activities

Group Meetings - Interaction with Others - Experience (Praxis) Increasing the Optional Activities

Enjoying the public space - jogging - individual activities Good Condition for Necessary activities

Suitable furniture - adequate lighting - cleanliness of the environment

13

of settings. Gehl says that these activities are “resultant” because they frequently evolve from activities in the other two categories as people in the same space meet, if only briefly (www.1). Same as optional activities, social activities are conditioned by the physical setting of the space (ibid.).

An interrelation of different types of activities in public space can be seen in Figure 1. I will use the definitions and functions of these activities later for analyzing the data and will discuss about them more in Chapter 6 as well.

2.2. Place and Social Construction of Space

Place is a repository of meaning, where one has attained a degree of ‘dwelling’ (Norberg-Schlutz,

1976), described by Hummon (1992) as ‘everyday rootedness’ (as cited in Hay, 1998). In a geographical sense, a person can become bonded to a restricted geographical locale; the ‘place’ includes the area in which that person routinely travels or is aware of in a detailed way, such as an urban metropolitan region, town land environs, small valley/island, or county/district (Tuan, 1974). When affective bonds to such a place are studied in a social context, the general place is assessed as a ‘center of felt value’, a ‘field of care’ (Tuan, 1974) or a ‘social field’ containing shared meanings (Hay, 1998). Following Massey’s formulation, “a place is formed out of the particular set of social relations which interact at a particular location” (Massey, 1994, p. 168) and its singularity is formed out of the specificity of interactions at that particular location and the social effects they produce, as well as out of the links and articulations of those relations with broader processes which stretch beyond the borders of that location. ‘Place’ is, in many ways, open and provisional rather than bounded, fixed and static. This kind of place is open to contestation and to different readings by individuals and groups who have differently constructed boundary experiences and preoccupations (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). It is also:

constructed out of movement, communication, social relations which always stretched beyond it. In one sense or another most places have been ‘meeting places’; even their ‘original inhabitants’ came from somewhere else. (Massey, 1994, p. 171)

14

Henry Lefebvre in particular in "the production of space", defines space not as a natural or transcendental phenomenon but as a historical integrity and social production. He believes (social) space is the outcome of a sequence and set of operations, and thus cannot be reduced to the rank of a simple object (Lefebvre, 1991). Lefebvre criticizes the classical opposition between physical (natural) space and mental space and believes that what really matters to humans is the social space. This space is constructed in a dialectic way through mutual actions. Living space is a space in which humans consciously or unknowingly, without verbal means, make a direct relationship with it and express themselves in it.

To summarize, public spaces are not only geographical locations of action, but also represent the possibility of shaping individual actions and social relations. Therefore, their dimensions are not only physical but also social and symbolic. From the anthropological point of view, space is where human beings live; where they are constantly interacting with, nourishing from it and change it; people move in the space and with this move they create meaning in the space; they transform the components of space into meaningful signs for themselves and add some elements to it as well. Different groups of people give different meanings to space, thereby transforming it into a multilayered place, showing how the concept of space is defined and understood by the users / groups of users. Based on the anthropological explanation that Lefebvre gives of space (as social production), the place where we live is on the one hand, the experience of our historical memory, and on the other hand, the experience of our everyday life (Fakouhi, 2003). In fact, space is also a result of the accumulation of past experiences and collective memory, as well as the result of our daily routine (time of work, leisure and travel) in the environment.

2.3. Everyday Life and Right to the City

The writings of Lefebvre influence the understanding of how space as a social and historical set of processes is understood, constructed, lived, and perceived (Merrifield, 2006; Beebeejaun, 2017). He emphasizes the solidarity between everyday life and urban space in his theory of the right to

the city. In fact, the right to the city is the public right of production of space; spaces that are

produced and reproduced in the city. For Lefebvre, as I mentioned before, the urban is not simply limited to the boundaries of a city, but in fact, includes its social system of production. The “right

15

to the city” represents the right to participate in society through everyday practice (e.g., work, housing, education, leisure). Hence the right to the city is a claim for recognition of the urban as the (re)producer of social relations of power, and the right to participation in it (Gilbert & Dikec, 2008). For Lefebvre, everyday life and the urban are inextricably connected.

Lefebvre also discusses the connection between everyday life and the dynamics of the urban. He mentions both the misery and the power of the everyday which are reflected and constituted in urban space: on the one hand, the tedious tasks, the humiliations, the preoccupations with bare necessities; on the other hand, the coincidence of need with satisfaction and pleasure, the extraordinary in the very ordinariness, the feeling of fulfilment (Lefebvre, cited in Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). As Jürgen Habermas, the contemporary philosopher and sociologist, points out, enabling human communicative action in the public domain and in the context of everyday life leads them to liberate themselves from routines, signifying the importance of everyday life and social activities. Ágnes Heller, in her seminal work Everyday Life (1984), points out that people do have the possibility to overcome the alienation of everyday conditions within the very everyday. In this line of thinking, Lefebvre marks out the political dimension and the revolutionary meaning of the (concept of the) everyday, which is also developed by Heller, although not in exactly the same terms, in her discussion of the potential, indeed almost a utopian promise, included in everyday life for the reconstruction of meaning and the transgression of alienation (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006).

Everyday life, as Heller (1984) states, does have something to tell us about the structure of society and about generic development. People lead very different everyday lives in a given society, their differentiation turning upon such factors as class, stratum, community, order etc. Everyday life of women can thus be different based on the social role of women in different societies. While traditional definitions mention equality, communality and homogeneity as part of what citizenship means, new forms of this notion incorporate issues of difference and cultural, ethnic, racial and gender diversity, wherein the exercise of power is challenged (Fenster, 2005). Urban spaces are actively constituted through the spatial practices of different groups. Yet developing an understanding of the multiple users who may either be in conflict or create gendered patterns of exclusion is rarely the focus of planning attention, much less policy intervention (Beebeejaun, 2017).

16

Beebeejaun (2017) asserts that Lefebvre’s concern with the alienating impact of the modern city emphasized an increasing disconnection between urban inhabitants and their abilities to participate in the production of spaces. The right to the city offers a series of perspectives regarding the redemptive political potential of the urban experience (p. 325). Lefebvre cannot be described as a feminist, yet his theoretical understandings of the social dynamics of space have clear implications for gender relations (Shields, as cited in Beebeejaun, 2006). Nonetheless, ‘contemporary urban theory that draws upon Lefebvre’s work rarely develops a feminist or gendered understanding of space’ (Beebeejaun, 2017, p. 325). She also names Fenster, 2005 and Vaiou and Lykogianni, 2006, as notable exceptions in this regard.

In the same sense, I agree with Tovi Fenster (2005) stating that Lefebvre’s theories of the right to the city don’t challenge any type of power relations (ethnic, national, cultural), let alone gendered power relations as dictating and affecting the possibilities to realize the right to use and the right to participate in urban life. The gendered aspect is not the only one absent in Lefebvre’s model. Other identity related issues and their effects on the fulfilment of the right to the city seem to be missing as well (Fenster, 2005).

2.4. Gendered Public Spaces - Women’s right to the city

Drawing on a detailed critique of the work of Harvey (1989) and Soja (1989), Massey argues that space continues to be theorized from the premise of the universal male norm, where women (and one would add, racialized groups) are generally regarded as other, to be subsumed within analyses concentrating on perceived changes in the relations of production and consumption. As Massey (1994, p. 213) notes: ‘. . . both postmodernism and modernism remain so frequently, so unimaginatively, patriarchal.’

The only point I want to make is that spaces and places, and our senses of them (and such related things as our degrees of mobility) are gendered through and through. (Massey,

1994, p. 186)

Similarly, the dichotomy public-private demands further theorizing and empirical investigation. Traditionally, urban geography located men in the public city spaces and women in the private,

17

domestic spaces, usually on the outskirts or in suburbia. This was critiqued by feminists (see, for example Hall, 1992) and more recently by a postmodern discourse that views the city as a democratized space where individual lifestyles reflect a new heterogeneity of choice, freedom and consumption (Scraton & Watson, 1998). Everyday ritualized use of space has a clearly gendered dimension as usually daily use of space is connected to gendered divisions of household duties. Women around the world are those who are responsible for the caring of the household members’ needs, either by themselves or with the help of other women (Fenster, 2005). Public places are arenas for the enactment and display of power and privilege; for the enactment of inequality in everyday life for women and for many other groups (Gardner, 1989). Many scholars believe that when the roles of women in societies changed, current cities have become increasingly inappropriate environments for them. They say that presumptions and male domination on urban planning and design lead to the creation of numerous discriminatory spaces against women. There is, among these researchers, an agreement that contemporary planners ignore the specific needs of "women of today" (MacKenzie, 2008). The gendered identity of the space is often shaped by the greater presence of men in the public spaces and the presence of women in the private. This situation has been shaped by dividing the work outside the home and the further separation of industrial production from private and domestic areas. And this division of the two domains into the male and female domains led to the gender segregation in public sphere. The cumulative result has been the reinforcement and policing of the spatial separation of the ‘natural’, male, public domains of industry and commerce from the private, female domain of homemaking (Knox & Pinch, 2006). The system of production which capital established was founded on a physical separation between a place of work and a place of residence (Harvey, 2010).

We need to think about how women’s experiences in public realm are partially constituted by and through their location in the web of social relations that make up any society. We also need to know how these experiences are affected, and how they affect - or enable or compensate for - the consequences of men’s activities, as well as their implication in class or race relations (Vaiou D. , 1992). Public spaces have a great impact on women's daily lives; women often have a close relationship with their urban environments and generally spend a lot of time outdoors and in urban social spaces. In their work, Variou and Lykogiani (2006), mention the role of women in shaping urban spaces thorough daily activities. They explain that women play a key role in the process of

18

family settlement: they are responsible for making ends meet in their households and it is they, rather than the men, who develop strategies of gradually appropriating urban space, using the city and the neighborhood and establishing daily routines— all of which contribute to build a more bearable everyday life in the city (Vaiou & Lykogianni, 2006). They also put emphasis on the importance of neighborhood in women’s everyday lives as a place of social interaction and development of strong or weak local ties, which contribute to a sense of security and belonging. In a fluid and unstable universe, women’s uses and perceptions of space and time are transformed along with the changing geography of everyday life. What is also changed is the realm of women’s struggles to redefine gender relations and put forward new understandings and practices of social change – of which the relationship between society and (urban) space is an integral part (Vaiou D. , 1992). Urban spaces should allow all individuals in society, regardless of age, gender or race, to be present equally and also provide a safe place for them to engage and be active; not only a place to do necessary activities but also a space to enjoy being and spending time in it. In this case, the city can become a vibrant and dynamic space instead of being static and objective. It will not just be a place for living but as Lefebvre states, it’s a reflection of society and social relations. The right to the city can be fulfilled when the right to difference on a national basis is fulfilled too and people of different ethnicities, nationalities and gender identity can share and use the same urban spaces (Fenster, 2005). In a nutshell, the right to the city cannot be achieved without the possibility of daily access to urban spaces. Gendered power relations should be considered in order to achieve “women’s right to the city”. Not considering women’s perception of the urban environment can finally lead to gendered discriminative urban spaces.

Here, at the end of the chapter, I should also mention that one of the most important and characteristic features of everyday life is its heterogeneity. Women, their actions and, consequently, their everyday lives cannot be considered as homogeneous. The norms and rules for action, the objectiveness, among which the person acts out their everyday life, are heterogeneous as compared with each other. But as Heller points out, this doesn’t exclude the possibility of more or less homogeneous spheres of action and objectivation – on the contrary, it is their pre-condition.

19

3. METHODOLOGY

In this chapter, I will present the methodological framework of this thesis, which is designed based on aims and research questions, and guided by theoretical concepts from previous chapter. I describe applied methods for gathering and analyzing the data. A literature review has been taken as the primary guidelines which then been developed in next stages of the field work to designing the questionnaire and interview structure. The study employs both quantitative (questionnaires) and qualitative methods (interviews and ethnographic photography). After a brief explanation of the research design, participants and measures of collecting material will be discussed. I will end this chapter by describing the limitations and obstacles I came across during the field work.

3.1. Research Design

As I mentioned before, the overarching goal of the study is to investigate the difference in perceived residential environment quality between women and men in the Lindängen neighborhood, Malmö, and its effects on everyday lives of women. In doing so, I have used different ways and methods to explore the gendered perception of the environment and its influence on everyday life of women. Theory has been playing a significant role in this research and particularly in framing the research method and analyzing the data, i.e., I used theories and literature for framing the way I should do the field work and later I used them as a help for decoding the data from observations and interviews. As Maxwell (2013) underlines, the traditional view that only quantitative methods can be used to credibly draw casual conclusions has long been dispute by qualitative researchers (e.g, Britan, 1978; Denzin, 1970; Erikson, 1986; Miles & Huberman, 1984). In this research both quantitative and qualitative methods have been used to gain a rich and sufficient amount of data. The hypothesis that the evaluations of environmental characteristics are related to gender has been tested with different methods and within a methodological process (Figure 2).

20

3.2. Participants

A sample of 55 residents (18 years and older) was drawn in this study. Among those, 50 participants, 26 females and 24 males, filled out the questionnaires. The participants were approached in different public spaces in Lindängen (centrum, Lindängen library, the playground, etc.). I tried to approach different age groups and different people but also tried to keep a balance between the number of female and male participants. A table of participants demographic can be seen in Figure 3.

In the next stage, five women living in Lindängen, were selected to participate in interviews. Again, at this level I tried to choose women from different age groups and different backgrounds. Table 1 summarizes the interviewees’ status.

0 9 5 11 24 Time of residency Up to 2 years 3 to 5 years 6 to 10 years More than 10 years

Designing the Questionnaire Literature Designing the Interview Questions

Questionnare Interviews • Analysis

0 7 17 10 9 7 Age 15 - 25 26 - 40 41 - 55 56 - 70

Figure 3- Demographic of respondents to questionnaires based on age and time of residency Figure 2- Methodological Process of the research

21

Table 1- Summary of interviewee’s information

3.3. Measures

I used three main ways of gathering data during the field work: filling out questionnaire, conducting interviews and observations which I have done during field trips to the area in different days and times. These measures will be explained more in detail in the following parts.

3.3.1 Questionnaire:

For designing the questionnaire, among different models, I used the framework introduced by Bonaiutto et al. (1999) which is assessed by some scholars as a common ground in research on residential environment quality and has been widely used by other researchers in a variety of settings (Dębek & Janda-Dębek, 2015). In their work, Dębek and Janda-Dębek (ibid.) defined 11 thematic scales of the questionnaire to measure Perceived Residential Environment Quality (PREQ) which has been previously mentioned in Chapter 2. These scales (consisting 32 statement) were chosen and modified to design the questionnaire, based on the case study neighborhood (Lindängen) and the subject of study. Theses scales are:

• Architectural & Urban Planning Features • Safety

Name Age Time of residency Working status children

Mina 37 29 years Working No

Paula 44 20 years Not working 3 grown up children

Noha 47 11 years Working as volunteer 5 children, 3 grown up

Shahinaz 49 2 months Working (self-employed) 4 grown up children

22

• Sociability

• Commercial Services • Recreational Services • Stimulating vs. Boring

• Transport Services and External Connectivity • Relaxing vs. Distressing

• Public Furniture • Upkeep and Cleanness • Neighborhood Attachment

The decision to drop some items and choose some others was made based on the study size, and consequently, number of respondents, time and resource limitation and the context of research as the large scale of the original questionnaire (126 items) is not very well suited for conducting an on-street survey.

The questionnaire has three main parts. The first part is gathering the personal information of respondents (including gender, age and time of residency in the neighborhood). The second part comprised 32 statements concerning 6 scales of perceived residential environment quality on a 5-point Likert-type scale. In the end, and in the third part of questionnaire, participants were asked to answer 2 descriptive questions about their neighborhood.

The English version of questionnaire was translated into Swedish. Both English and Swedish versions were used during the field work. A majority of residents used the Swedish version and in one case a translation to Arabic was done for one respondent. The English versions of the PREQ questionnaire along with its Swedish translations are given in Appendices 1 and 2. The total number of respondents was 50, comprising 24 women and 26 men. The respondents to the survey were chosen in different parts of Lindängen, mainly in the centrum and the Lindängen library. Responses to descriptive questions were 21 individuals, 10 men and 11 women. The answers from descriptive questions also provided an insight about how residents feel about their neighborhood and what is important for them.

Based on current questionnaire, the perceived residential environment of respondents could be compared by different variable factors: gender, age and length of residency. Of particular interest

23

here, following the main purpose of my study, was to find the in residential environment perception between men and women. So, gender is the main variable factor in analyzing the data of questionnaires in this study.

3.3.2 Interview

As Maxwell (2004) states, qualitative researchers usually study a relatively small number of individuals and preserve the individuality of each of these in their analysis, rather than collecting data from large samples. With this approach researchers are able to understand how events, actions, and meanings are shaped by unique experiences of each of individuals. In the same regards, the number of participants in this research were kept small in order to put more focus on every individual.

Based on primary data analysis by SPSS, 4 categories of perceived environmental quality at the neighborhood level have been developed to design questions for semi-structured interviews among female residents. Those were the items where considerable differences between female and male respondents could be observed. In another word, questions which had the most significantly different responses between men and women were used in the interviews in order to gain a deeper understanding of women’s responses to those questions.

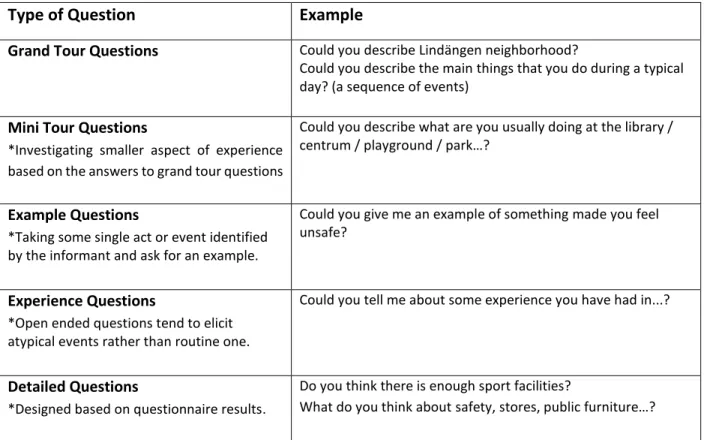

I conducted a total five one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with women living in Lindängen. These audio-recorded interviews were carried out at different places (Lindängen Library, ReTuren, and Folkuniversitet). I began each interview by enquiring the background and basic information of each of the participants. Then, I continued the interview/conversation based on designed question. The interview questions focused on how these women use the public spaces in Lindängen and what their main needs and concerns are, specifically with respect to the four aforementioned categories from the questionnaire. I should mention that I tried to keep the interview in an open way and let the interviewee help me to ask more in-dept questions. In the same way, the responses from each interviewee helped me to gain a better understanding of the concepts and therefore, in some cases I could make more detailed questions about the same topic from next interviewees. On average interviews lasted approximately 40 minutes. The main questions of the interviews were designed based on 4 types of descriptive questions defined by Spradley (1979): Grand Tour

24

Questions, Mini Tour Questions, Example Questions and Experience Questions, followed by more detailed questions related to the questionnaire.

A sample of main questions in the interviews can be seen in Table 2.

Type of Question Example

Grand Tour Questions Could you describe Lindängen neighborhood?

Could you describe the main things that you do during a typical day? (a sequence of events)

Mini Tour Questions

*Investigating smaller aspect of experience based on the answers to grand tour questions

Could you describe what are you usually doing at the library / centrum / playground / park…?

Example Questions

*Taking some single act or event identified by the informant and ask for an example.

Could you give me an example of something made you feel unsafe?

Experience Questions

*Open ended questions tend to elicit atypical events rather than routine one.

Could you tell me about some experience you have had in...?

Detailed Questions

*Designed based on questionnaire results.

Do you think there is enough sport facilities?

What do you think about safety, stores, public furniture…?

Table 2- Designing the questions, based on James P. Spradley’s four types of questions with addition of Detailed Questions retrieved from questionnaires data analysis.

3.3.3. Photographic observation

The pictures show how women deal with space, ways to use space, specific areas that are most used by women, or conversely spaces that are mostly male dominant. There was no interaction with the users during the shooting and I did not interfere with the users' behavior and only recorded the existing conditions. All photos are taken with a digital camera or cell phone and are not edited after shooting.

25

3.4. Limitations

Limitation in time and resources has affected the number of respondents to the questionnaire, the number of interviewees, and the quantity of ethnographic research. Another factor affecting the fieldwork was climate situations since the study is about outdoor everyday activities. I have different field trips to the area during different times (from January to December 2019). During sunny days of summer outdoor activities are at the highest while, during the rainy or cold days almost no one spends time at outdoor spaces, unless for shopping, walking dogs or in some occasions for running or jogging.

Another factor that its effects cannot be ignored is the language barrier. The main used language to approaching people for filling the questionnaires were Swedish. Although in some cases English translation were used but, in some cases, it happened that a person did not fill the questionnaire since they were not comfortable with neither Swedish nor English. Similarly, although the interviews were conducted both in English and Swedish, but it should be considered that neither of these languages are the main language of most of the residents in the neighborhood.

26

4. PRESENTATION OF OBJECT OF STUDY

In this chapter I present a picture of the Lindängen neighborhood in Malmö, Sweden. I will, first, give a brief description of the area by providing some statistics, history and socio-economic description of the area. After naming some initiatives active in the area, I will provide a brief description of how the neighborhood has been presented and how it can be perceived from the eyes of an outsider.

4.1. Lindängen Neighborhood

The city of Malmö, in southern Sweden with a population of somewhat over 300,000 inhabitants has a direct link to Denmark and the European continent via the Öresund bridge. Malmö has undergone a rapid transformation from an industrial city in decline with its roots in shipping industry towards an ambitious and innovative city, redefining itself as a “city of knowledge”. Like many cities around Europe, in Malmö a great deal of social diversity has emerged since industrialization; an ethnic diversity related to labor migration, refugee waves and family immigration. At the same time as diversity has increased, socio-spatial polarization has also increased through exclusionary processes and produced residential areas where socially excluded people have gathered.

Lindängen is located in the south-east of the inner ring road of Malmö and is a part of the Fosie district, between Trelleborgsvägen and the railway towards Trelleborg and Ystad, which also consists of Almvik and the residential area Kastanjegården (Bebyggelseregistret, u.d.) (see figures 4 and 5). The area has had a varied development and consists of several different parts: it is divided in the north-south direction by a strip consisting of the green area Lindängen (in the north), the block with schools and center facilities and a sports area (in the south). In the east-west direction Lindängen is divided by Munkhättegatan (Bebyggelseregistret, u.d.).

27

From the beginning, the main vision of building the area was that it would have a wide range of services and activities, and the center of Lindängen1 was planned to provide unique service facilities. When the area was built, it was MKB (Malmö Kommunala Bostäder2) that both owned and managed the rental apartments. However, with the change of power that took place in 1985 when a liberal-conservative government took over, all of MKB's housing stock on Lindängen was sold to private property owners (Sjöblom & Österberg, 2013). Until now, many buildings in the area, including the center outdoor

space have private owners.

1 - Lindängen centrum

2 - Malmö municipality real estate company

Figure 4- Lindängen, located in sought east of inner ring road of Malmö, is a primarily residential area characterized by large green spaces.

Figure 5- In Lindängen there are large nice green areas, a city park, an amphitheater, an outdoor swimming pool.

Figure 6- Bus routes connecting Lindängen to other parts of Malmö

28

4.1.1. Statistics summary

Lindängen is a fast-growing, socially, culturally and socio-economically diverse area with a population of around 7000 inhabitants (as of 2014, 6,874). Figures from January 2010 indicate that Lindängen has a young population with more than thirty percent aged 6-24 years (Malmö city, 2010). Many in the area live in multi-family houses, mostly rental townhouses built in the 1970’s and 80’s. 12% of families have more than one child, mostly in the preschool age.

Lindängen is one the neighborhoods in Malmö which has been identified as especially “vulnerable”, where residents have relatively low rates of post-secondary school education, employment, election participation and life expectancy as compared to other areas of the city and country (Malmö, Sweden, 2019). 29 % of residents are highly educated, 42 % have upper secondary educations and 21 % have primary educations. The employment rate is consistently about 20 percentage points lower than the employment rate for Malmö as a whole, just over 40 percent compared to just over 60 percent since the mid-1990s. About 45 % of people between 20 and 64 years old are employed. Malmö's level of employment is consistently more than 10 percentage points lower than the national average. Thus, the employment rate in the area is markedly lower than both the municipal and the national average. As expected, the low employment rate strikes through at the income level in the area, which is considerably lower than the municipality as a whole. Disposable income, calculated on all persons of working age, is 70 percent of the average for the entire city of Malmö (which is among the lowest in the municipality) and 38 percent lower than average in Sweden. (Salonen, 2014).

Almost a third of newly moved-in people move out of the area already the year after they moved there, and a fifth after a maximum of 2 years. More than half of all those who moved to Lindängen during the current period have lived in the area for a very short time and then moved on (Sjöblom & Österberg, 2013). This demonstrates the fluidity of the area and that the area seems increasingly to be a passage area where many only live for a short period.

29

4.1.2. Buildings (residentials) development history

In Sweden, rapid urbanization, growing prosperity and demands for higher housing standards led to years‐long housing queues. To end the housing shortage once and for all, the Swedish parliament decided that a million new dwellings should be built in the period 1965 to 1974 (Hall & Viden, 2006). Lindängen was one of the areas in Malmö that developed rapidly during the late 1960s and 1970s as a part of Sweden’s Million Program3 and has met socio-economic challenges

right from the beginning. The majority of buildings in the area are residential apartments both public utilities and private tenancy. The buildings have a total of about 2,600 apartments. About 1,000 residents live in the four buildings that are included in the Lindängen demo site constructed during 1970’s. Builders of Lindängen were three of the major players in Malmö's construction: EIA, HSB and BGB. The houses were designed by, among others, HSB architectural offices in Malmö, Thorsten Roos & Bror Thornberg and Fritz Jaenecke & Sten Samuelson (Bebyggelseregistret, n.d.).

Lindängen has a mixed development that reflects the ideals of different times the accommodations as well, consist of residential estates built during different periods: In 1960s and during The Million Program simple slab houses were built in yellow brick or with concrete facades. In the early 1970s more building with darker color and smaller scale were build. More fancy buildings from the years around 1980 added to the area as a result of the criticism to the Million Program. The northern part of Lindängen is characterized by an open, right-angled and large-scale structure. Many of the older houses in Lindängen have undergone facade changes that reflect recent critical views on the architecture of the Million Program (Bebyggelseregistret, u.d.).

In 1967 and 1968, city plans were drawn up for different parts of the area. The first plan included the Kantaten and Hymnen block and provided a three and eight-floors settlement where the lower one would be facing Fosie church. The plan also included an outdoor swimming pool in the northern part of the area. The plan was not immediately accepted, but a planned 154-meter-long high-rise building had to be shortened to about 80 meters, as the proposed design made the house too close to both the feed route and the entrance to the area. Munkhättegatan and Eriksfältsgatan