International Migration and Ethnic Relations Bachelor Thesis

15 Credits Spring 2016

Supervisor: Camilla Safrankova

An Investigation of Discourses on

Ethnic Minority Children

Experiences from Danish Preschool Pedagogues

Emma Becker

920424T047

Abstract

This study seeks to identify discourses on ethnic minority children in the preschool system of Copenhagen, and in extension investigate what consequences the discourses have to the “subject position” of the children. The study includes a small-scale qualitative study of Copenhagen institutions based on the collection of three semi-structured interviews with preschool pedagogues. Additionally, the “Inclusionguide” from the municipality of

Copenhagen have been included to strengthen the analysis. The material has been analysed using a range of theoretical concepts of Michel Foucault. Based on the analysis, the thesis identifies several elements, which permeates discourses surrounding ethnic minority children. The thesis concludes that discrepancies between the institutional sphere and the family sphere can cause the children be categorised as “wrong” or “abnormal” according to the discourses reproduced in the institutions. Furthermore, the thesis suggests that discourses are based on dualistic assumptions and controlling power relations, and are problematic to challenge.

Contents

1 Introduction ... 5

1.1 Research Background ... 5

1.2 Purpose of this Study ... 5

1.3 Research Questions ... 6

1.4 Definitions and Limitations ... 6

1.5 Thesis Outline ... 7

2 Review of the field ... 8

2.1 Previous Research ... 8 3 Material ... 10 4 Method ... 11 4.1 Research Paradigm ... 11 4.2 Semi-Structured Interviews ... 12 4.2.1 Interview Planning ... 12 4.2.2 The Setting ... 13

4.2.3 Ethical Reflections Prior to Interviews ... 14

4.2.4 Data Collection ... 15

4.3 Text Analysis of Discourses ... 15

4.3.1 Coding ... 15 5 Theory ... 16 5.1 Theoretical framework ... 16 5.1.1 Discourse ... 17 5.1.2 Institutions ... 18 5.1.3 Power as Discipline ... 19 5.1.4 Knowledge ... 20 5.1.5 Subject Position ... 20

6 Analysis and Discussion ... 21

6.1 Themes ... 22

6.2 Language as a Barrier ... 22

6.3 Discourse of Discretion ... 24

6.4 Institutional Reproduction of Discourses ... 26

6.6 Discourse on Modernity and Progression ... 29

6.7 Subject Positions ... 29

6.8 The Ambiguity of Initiatives ... 31

7 Conclusions ... 32

7.1 Results ... 32

7.2 Evaluation ... 33

7.3 Recommendations for Further Research ... 33

9 Appendices ... 35

Appendix A: Information letter ... 35

Appendix B: Consent form (Translated from Danish) ... 36

Appendix C: Interview Questions ... 37

Appendix D: Transcription INT1 ... 38

Appendix E: Transcription INT2 ... 48

1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

As a result of international migration flows in all varieties, the positions of ethnic minority children in the educational systems of receiving countries have become increasingly relevant to address. This thesis will discuss discourses on ethnic minority children and how they position the ethnic minority children in the preschool institutions in Copenhagen, Denmark. Ethnic encounters in educational systems have gained significant attention

throughout modern history. The perhaps most controversial and publicly discussed case is the initiative of affirmative action, which has its roots in the U.S. and the oppression of African Americans. This thesis argues that discourses on ethnic minority children in the educational system and their influence are strongly connected to the field of International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER) in modern society. This research project is of fundamental

relevance to IMER studies, as it strives to address an area that has a central influence on traditional IMER concepts, such as integration and multiculturalism. Nevertheless, such complex concepts will not be explored in this thesis. While this study will avoid the all-encompassing discussion of whether notions of “ethnicity” and “race” should be

acknowledged or not, the emphasis of the study is to identify discourses on ethnic minority children in preschool of Copenhagen and discuss how discourses regulate the subject positions made available for the ethnic minority children.

1.2 Purpose of this Study

The aim of this study is to identify discourses on ethnic minority children in the preschool institutions of Copenhagen, Denmark, and furthermore, investigate what

implications these discourses have on the positioning of ethnic minority children. This will be explored through an analysis of 1) three semi-structured interviews with preschool

pedagogues, and 2) the “Inclusionguide” issued by the Municipality of Copenhagen.

Pedagogical researchers have approached the issue of the role of ethnic minority children in the institutional sphere before. However, aiming to provide the missing social science contribution, I will approach the topic from a sociological perspective, connecting the

micro-level of my empirical data, to the societal and structural micro-level, using sociological concepts of Michel Foucault.

1.3 Research Questions

The topic of this study will be investigated through the following research questions.

1. What discourses can be identified on ethnic minority children in preschool institutions in Copenhagen, Denmark?

2. What implications do the discourses have on the subject position of ethnic minority children?

The research questions are based on the assumption, that the concept of discourses can be applied and discussed in all social settings. This assumption originates in the research paradigm, as well as in previous research.

1.4 Definitions and Limitations

It is a challenging task to define research questions within the IMER field. As the majority of IMER subjects are sensitive and ambiguous, the researcher must maintain alert to the use of language to avoid including certain pre-assumptions in the research questions. Similarly, the language used in the research questions of this particular thesis demanded thorough consideration in regard to how to address the issue in a way that ensured the flexibility for interviewees to address the subject from their perspective.

One main issue was to consider the definition of the group of children I wished to address. In the early work, I began to describe the children as “immigrant children”, yet the impreciseness became evident early on. For example, the group of 2nd generation and 3rd generation immigrant children can be convincingly argued to belong to that group. However, I do not wish to investigate the children themselves, but instead, examine the discourses and how they position the children.

I have chosen to use the term, “ethnic minority children”, for the children in interest. While this term is likely to have different interpretations and understandings for the

belongs to the group or not. What is interesting is the discourses and how, whomever someone ascribes to the group, is positioned within the discourses.

Secondly, I have chosen to emphasise that the investigation is carried out in

Copenhagen. The emphasis highlights that it is within an urban setting the investigation takes place. It is possible that the results could have been different, if the investigation was carried out in another place, perhaps in a rural environment in Denmark. It can be argued that the flow of people is bigger and more constant in bigger cities. According to Statistics Denmark, the Copenhagen Region has the largest percentage of immigrants and descendants, as they constitute 17,5 per cent of the regional population, whereas the percentages in the other four regions are less than the national average of 11,6 per cent (Danmarks Statistik, 2015). Without going in depth with this issue, I recognise the possibility that amount of the immigrant and descendants population, can affect the discourses of “ethnic minority children”.

Lastly, I wish to elaborate on the use of the term “preschool institutions”. In Denmark, the term “preschool institutions” includes both “vuggestue” and “børnehave”. These institutions are both found individually or as “integrated institutions”, which combine the two. The integrated institutions, therefore, include children from 9 months to 5 or 6 years. Physically, socially and academically, these institutions carry great responsibility of the development of the child, in the way that they establish the foundation for the child’s relation to the institutional and educational setting, as well as society at large.

1.5 Thesis Outline

In Chapter 1, I have been introducing the research problem, aim and research

questions. Furthermore, I have begun to describe the definitions and limitations of the study. Chapter 2 starts out by outlining the previous research in the area of ethnic minority children in the context of Danish preschools, as well as in an international context, and continues to locate this study within that frame.

Chapter 3 includes a brief introduction to the material used.

Chapter 4 briefly begins to presents the overarching research paradigm of social

constructivism. The chapter continues to present the methodological framework of the study, discussing the choice of methods, and explaining the strengths and weaknesses of semi-structured interviews. The chapter will also briefly outline the method of coding and the applied text analysis.

In Chapter 5 the theoretical framework of the study is described, presenting the Foucauldian concepts that are central to the study.

Chapter 6, the analysis and discussion, starts out by presenting the findings of the interviews. The chapter continues to relate the collected data and the Inclusionguide to the previously outlined concepts of Foucault, presenting a thorough analysis and discussion of the data in connection to the research questions.

The final chapter 7 sums up the core findings of the study and validates its usefulness for further research.

2 Review of the field

2.1 Previous Research

There has been significant research and fieldwork on the role of minority children in the educational system, both within a Danish context as well as in the international context. Based on her Ph.D. thesis, Danish cultural sociologist Charlotte Palludan wrote the book

Børnehaven Gør en Forskel (The preschool makes a difference) in 2005, which seeks to

investigate how sociocultural differences and inequalities are established and re-established in preschool children’s encounter with the pedagogues. Palludan’s ethnographical work contains a great emphasis on detail in her everyday observations, as some of her focus points are rhythm, tone and placement of the everyday activities (2005: 185). Thereby her focus is the physical meeting between the child and the pedagogue. Her study shows that through the hierarchical encounter between preschool children and pedagogues an idea of “the

respectable body” is constructed, and characterised by calm actions and constructive dialogue. By compliance to this idea, the children can obtain the most useful and equal relationship with the pedagogues (171). Thereby she implies that the discourses, which framework is decided upon from the state through the pedagogues, decide what is

“respectable”, what is “normal”, and what is “abnormal”. Thereby the discourses imply how the children must behave and interact in order to be seen as part of the “respected

community”.

Similarly, anthropologist Helle Bundegaard and pedagogical anthropologist Eva Gulløv have developed the ethnography Forskel og Fællesskab (Difference and Community), which investigates how the everyday life is carried out in two institutions, which consists of

children with different social and cultural backgrounds. The book concludes by stating, that in some cases, differences are established and empowered in preschool institutions and that the integrative project of the municipality has ambiguous outcomes (2008: 206). With the inclusion of the municipality’s integrative project, Bundgaard and Gulløv presents the ambiguous position of the pedagogues, who is required to adopt certain tools of inclusion, however, these tools presents an issue in regard to seeing each child individually.

I have no knowledge of international research that addresses ethnic minority children in preschools. I am doubtful and hesitant about the causes hereof, however, it could be caused by different perceptions of preschool institutions internationally as presented in my data, yet that claim is not based on evidence. Nevertheless, many authors have addressed schools, as researchers agree that school have immeasurable influence on the life of children, and more specifically on the life of ethnic minority children. In the book Children of Immigration (2001), Carola and Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco explore the experiences of immigrant youth in the United States.

C. and M. M Suárez-Orozco explicitly investigate the workings of the school.

We focus attention on their schooling because schools are where immigrant children first come into systematic contact with the new culture. Furthermore, adaptation to school is a significant predictor of a child’s future well-being and contributions to society. (C., and M.M Suárez-Orozco, 2001: 3)

The research of C. and M.M Suárez-Orozco was motivated by the same reflections as this research, as both studies strived to discuss and interpret the mechanisms that contribute to the role and positions of respectively immigrant children, and ethnic minority children, in

educational systems.

C. and M.M Suárez-Orozco address the issue of overcrowded school in areas of violence and poverty. Similar to my data they argue that savvy parents and charismatic mentors, for example, teachers play a decisive role. They request investment in the troubled schools and require additional resources. They argue ‘[cultural] sensitive information to immigrant families about how they can ensure that their children will receive a solid education clearly should be a policy goal’ (C. and, M.M Suárez-Orozco, 2001: 152).

While I will place myself within some of the same frameworks of institutional concerns as Palludan, Bundegaard and Gulløv, I will strive to link the ethnographical data to the macro level of state discourses, providing a theoretical approach using concepts of Foucault. The

research will continue to discuss the claim of C., and, M.M Suárez-Orozco by analysing the investment in inclusion by the municipality of Copenhagen. Thereby I will contribute with a theoretical approach, which strives to determine how the case of ethnic minority children in the Danish preschool system can be understood in relation to larger matters of International Migration and Ethnic Relations.

3 Material

The analysis of discourses is based on primary empirical data, however, secondary material is also used to strengthen the analysis. For the collection of “on the ground” empirical data, three semi-structured interviews of approx. 30 min, have been designed and conducted by the researcher. The semi-structured interviews were carried out to ensure an in-depth understanding of the relationship between the interviewee and the phenomenon

investigated.

I, trying to stay as close to the spoken word as possible, have transcribed the interviews, which can be found in appendices D-F. The interviews contained several instances of unfinished sentences as well as implicit messages. I have pursued to make the message clear by using brackets to indicate what is presumably meant or referred to. While it was a priority for the research to pursue a dialogue-format of the interviews, the questions were not always kept to the exact wording planned, and the spoken questions are therefore put in brackets following the original questions. In the analysis “INT” will be used as a substitute for “Interviewee”, and Interviewee 1, 2 and 3 will, therefore, be referred to as “INT1”, “INT2” and “INT3”.

For supporting material, the analysis will include an analysis of the Inclusionguide. The Child and Youth administration of the municipality of Copenhagen developed the Inclusionguide, in order to help pedagogues reach higher levels of inclusion in institutions (Børne- og Ungdomsforvaltningen, 2010: 10). The guide is not legislation, nor does it contain concrete ways to achieve a higher level of inclusion. Instead, it should be understood as a document with suggestions for areas of action and ideas to evaluate the level of inclusion. The document covers 6 focal points: open and development oriented teaching environments; academically, personal and social development for everyone; flexible resource allocation, early and preventive interventions, holistic thinking and bride building and inclusion as a

dynamic and renewable process. It is suggested that the focal points can be approached from three levels; the management level, the pedagogical level, and the parent level.

4 Method

4.1 Research Paradigm

The thesis adheres to the social constructivist and qualitative research paradigm. The paradigm describes a research approach, which includes a philosophical and theoretical framework. These frameworks outline a set of beliefs and understandings that establish a common ground for scientists researching within the field. The paradigm also notes a set of research methods, which correspond to the epistemological, ontological and methodological assumptions the paradigm carries. The approach advocates that reality and truth do not exist in a pure and objective format, but instead are given meaning by people. In extension, truth has different meanings, as individual and social characteristics shape the way the individual perceive the world (Moses and Knutsen, 2012: 10). The research paradigm affects and underlines the selection of both method and theory in the thesis, as this research recognises different perceptions of realities and truths of the world.

One key belief of the social constructivist approach is the notion of “human agency”, which refers to the capability and willingness of humans to adhere to a certain attitude towards the world. The recognition of humans as intellectual and reflective individuals challenges the naturalist ontological and epistemological beliefs; that the world exists only of what can be directly experienced and observed, and therefore relied on as true knowledge (Moses and Knutsen, 2012: 8). Nevertheless, the belief in human agency complicates these ontological and epistemological ways of reasoning. The concept expands the methodological framework as the social constructionists avoid using fixed criteria in their evaluation of the reliability of knowledge production (Moses and Knutsen, 2012: 10).

While these acknowledgements threat the possibility of presenting a reliable claim based on my findings, it is important to stress that my conclusions and claims should not be understood as generalizable “truths”, but instead as more narrow claims of existing

4.2 Semi-Structured Interviews

For this research, three semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain a high level of adaptability. In his book Social Research. Issues, Methods and Process (2011) Tim May argues that the high level of adaptability in semi-structured interviews allows the researcher to probe beyond the interview questions in case an interesting point or theme appears (134). The adaptability and flexibility of semi-structured interviews allow for more quality and perhaps relevance of data, however, it complicates the comparison between the interviews, as the focus might not be the same (May, 2011: 135-136). While this can be argued to be problematic, this research is significantly interested in the variety of discourses. This implies that the outlined discourses, due to lack of supporting material, should not be interpreted as “truth”, but rather as an interpretation of different expressions of discourses. Qualitative research does not strive to confirm postulated truths but is instead eager to investigate different understandings of the phenomenon of interest. Additionally, the

structured aspect of the semi-structured interviews does allow the research to outline possible similarities between the answers of the interviewees, and in the analysis come together and outline general tendencies of the discourses.

4.2.1 Interview Planning

Similar to the research questions, the planning of the interview needed thorough consideration and the interview questions were developed with carefulness to avoid the project to carry significant sensitivity. The concept of ethnicity is by some people understood or interpreted as a connotation to the concept of race, which carries a long history of

controversy. The development of the interview questions, therefore, required significant work on the wording, the theme, the tone, the framing, the order etc. to avoid controversy and increased sensitivity. The translated interview questions can be found in appendix C.

Several other aspects needed attention in order to obtain more “valid data”, in the sense that it should not be biased or somehow guided by the interviewer. While these points have gained widespread attention, I acknowledge that my world-view and the discourses I am surrounded by, are inherited in the communication skills, behaviour, interpretation and analysis of the thesis. May argues

… interests have guided our decisions before the research itself is conducted. It cannot be maintained that research is a neutral recording instrument, whatever form it take. The very construction of a field of interest it itself a matter of academic convention that should be open to scrutiny. (May, 2011: 31)

Thereby my initial motivation for conducting this research has influenced how the research has been carried out. While this impossible to avoid, the researcher must consider this in relation to the results.

The interview questions are mainly non-directive, which means that they carry an “open-ended” format. The open-ended questions allow for both longer and independent answers. John W. Creswell, Professor in Educational Psychology, argues that the interview questions should be ‘…emergent rather than tightly prefigured’ (Creswell, 2014: 181). The interview questions should be understood as preliminary, as the execution of the interview might cause the questions to be refined or changed. The adaptations of the questions are shown in brackets following the original question (See Appendices D-F).

Another important aspect in the conduction of semi-structured interviews is the establishment of “rapport” between the interviewee and interviewer. To establish rapport is the building of trust between the interviewer and the interviewee, which will allow the interview to unfold more naturally and freely (May, 2011: 140). May argues that the establishment of rapport between the interviewee and the interviewer is ‘… of paramount importance given that the method itself is designed to elicit understanding of the

interviewee’s perspectives’ (May, 2011: 143). One way to help establish rapport is to “build up” the interview, and I, therefore, initiated the interviews with descriptive questions. In this way, a dialogue is initiated, and the risk of the interview feeling like an interrogation is avoided. Also, it allows me to behave and represent myself as a non-judgemental, understanding and interested listener throughout the first and less sensitive section of questions.

4.2.2 The Setting

The interviews were planned to take place in the workplace of the interviewees, however due to lack of time, it was only possible for one out of three interviews to be carried out in the workplace. The additional interviews were carried out in the home of the

interviewee was believed to ensure that the replies of the interviewees would be based on experiences in the institutional setting, and not be expressions of the private sphere. However, during the interviews, it became evident that the children of interest are often discussed between pedagogues, and that the interviewees largely use both their professional and personal reflections in their work. Thereby the line between their private and personal opinions become less clear, and the influence of the setting become less predictable, and perhaps less relevant to address.

4.2.3 Ethical Reflections Prior to Interviews

I developed two precautious tools to ensure transparency and trust from the first contact with the interviewees. Initially, I developed an information letter, which included a short description of the research project as well as thorough information about the interview, covering themes such as anonymity, timeframe and rights. The letter was used in the initial correspondence prior to the interview and was also presented in print at the interview. Secondly, I produced a consent form, which ensured that the research project is carried out with the correct ethics. The form ensures written consent of the interview and allows the interviewee to permit the use of anonymous citations as well as the audio recording of the interview. Furthermore, it gives the interviewee the possibility of receiving a copy of the transcript as well as the final thesis. The information letter and the consent form can be found in appendices A and B.

I have 5 years of working experience in the preschool environment in Copenhagen, and can, therefore, be argued to have gained comprehensive insights to the job of

pedagogues, which can contribute to my understanding of the interviewees. However, other personal attributes also influence the information made available. The sex, language and accent of the interviewer can be argued to be positive notions, as they are predominantly similar to those of the interviewees. The only exception is INT 2 who is male, however, the other personal attributes, such as language and accent are similar to mine. This gives me a lead in relation to the establishment of a common framework, however, it also presents a possibility of the dialogue to be implicit.

Yet, the age gap between the interviewee and the interviewer might affect the confidentiality of the interview. The different sets of experiences and different sets of

to strengthen the analysis, as it causes the analysis to be less implicit, and requires the

researcher to look for, and thoroughly describe, clear expressions of discourses and opinions.

4.2.4 Data Collection

To find interviewees I went to several institutions and presented my project to the institutional leader. After approval from the leader, my information letter was presented in the office for the pedagogues to see. Thereby the pedagogues were free to contact me to set up an interview. The group of interviewees consisted of two women and one man, who all have been working as pedagogues for approximately 30 years. While it can be argued to have been more representative to interview a broader age range, I hope their experience in the field will provide me with concrete data as they presumable have been confronted with such subjects previously.

4.3 Text Analysis of Discourses

This thesis uses discourses of minority children as theoretical concepts from Foucault and does not strive to use discourse in a methodological sense. However, Fairclough (2003) argues that it is impossible to understand the social effects of discourses without analysing language (3). Therefore, this thesis will include a text analysis of the interview transcripts, which strives to gently seek to outline the concepts and categories the interviewees use and through those present one or several existing discourses.

4.3.1 Coding

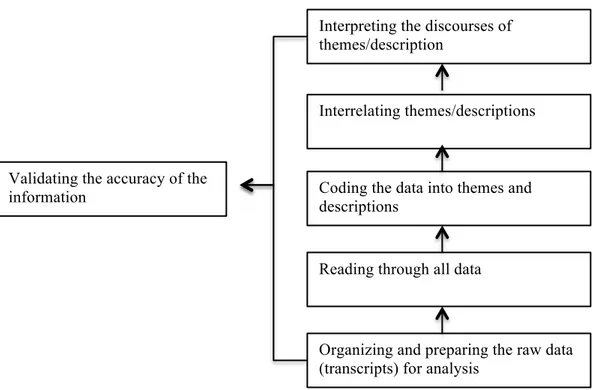

To establish a framework for further analysis of the data I have applied the method of coding. The general idea of coding is to organize the data into sections and assigning a word representing a concept or category, which is often based on the language of the participants (Creswell, 2014: 198). Thereby the method of coding allows the researcher to conceptualise the data and create a more tangible starting point for further analysis (May, 2011: 152). The 6 steps suggested by Creswell in his book Research Design. Qualitative, quantitative, and

mixed methods approaches (2014) have inspired the coding process of this study (197-200).

The steps proposed by Creswell are interpreted and slightly modified in Figure 1, and are applied to the material in Chapter 6: Analysis and Discussion.

Figure 1 - Interpretation of Creswell's 6 steps of coding

The initial step was to transcribe, organize and prepare the raw data, i.e. the interviews, for interpretation. Following the preparations, I thoroughly read through all the data and began the coding process. This was done by hand, by using coloured markers to highlight the different themes and subjects that I had noticed during my reading.

5 Theory

5.1 Theoretical framework

In the choice of research methodology, one must develop a set of research questions, and choose the tools and methods that the researcher believes are the strongest candidates to answer the research questions. However, the researcher must also decide upon a theoretical framework to work from (Rose, 2007: 1). This thesis will draw on theoretical concepts from Michel Foucault (1926-1984), a French theorist. While his profession was a philosopher, his work ranges across several disciplines, including philosophy, history and sociology.

Although his work and influence are impossible to describe in short, one can argue that he

Validating the accuracy of the information

Interpreting the discourses of themes/description

Interrelating themes/descriptions

Coding the data into themes and descriptions

Reading through all data

Organizing and preparing the raw data (transcripts) for analysis

was one of the key players in the break with the ways of thinking at the time, which maintained the idea of an underlying truth and the tradition of hermeneutics (Lindgren in Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 331).

Lindgren outlines the pursuit of Foucault shortly and precisely. He argues that in contrast to most previous philosophers, Foucault did not strive to develop general theories that apply to all humans and societies (Lindgren in Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 331). On the contrary, his entire work strives to prove the unfairness, destructiveness and the violence of the development of universal theories and discourses. An example of this was Foucault’s continuous struggle to avoid being labelled within a certain discipline or ideology. Instead, Foucault describes the fruitfulness of concrete research through defined and limited empirical fields (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 331). From this belief comes the idea of working within the discursive tradition, which is researching within a limited context. As mentioned earlier, the work and influence of Foucault are close to impossible to delimit, and I, therefore, feel the need to point out that the work I will deal with is the work on the modern society’s social control, the social construction of subjects and finally the role of power. The

contributions to this research will be the concepts of “discourse”, “institutions”, “power as discipline”, “knowledge”, and “subject position”.

5.1.1 Discourse

The overacting concept used in this thesis is the concept of “discourse”, which should be understood as the social production of norms, morals and values, which sets out to

regulate how individuals engage in society. Foucault investigates the historical and political conditions, which cause discourses to be seen as truthful. While Foucault’s approach to knowledge is based on the idea of socially, politically and institutionally constructed “truths”, which cause the subjects to be constructed as objects within social science, he does not search for meaning and truth outside the discursive field (Bang and Dyrberg, 2011:10). Instead, he investigates how, and due to what mechanisms, discourses are constructed and maintained. Foucault (1970) argues that discourses are a part of the order of laws, and while it posses intimidating power to us, the only ones who give it power are us (51). While the power of discourses is frightening to us, we are the ones feeding it, and most importantly controlling it.

In the attempts to decrease the power of discourses, every society has set up numerous procedures to control, select and organise and essentially “master” the overarching discourse (1970: 52). To control discourses states regulate and legislate to “tame” it, however, the

prohibitions reveal the foundation for discourses, the division of “reason” and “madness” (1970: 53). While Foucault traces the origin of individuals behaving and speaking within discourses to the Middle Ages, one can argue that the pursue to control discourses, has resulted in the issue of dualistic thinking, which permeates modern thinking. Modern ways of understanding are based on the idea of dualism and polarities. For example, there is no such thing as happiness, if there is no sadness; nothing is tall, if nothing is low etc. Similarly discourses are built upon the assumption of the overarching dualisms of right and wrong, true and false, normal and abnormal.

Foucault argues that the “will to truth” is yet another system of exclusion, which rests upon the power of institutions. The system of exclusion is continuously renewed and

reinforced by states, which gives ground for the idea that discourses are neither constant nor fixed (1970: 55). Thereby the “will of truth” is used to justify prohibitions and definitions of “reason” and “madness”. Foucault (1970) argues that individuals define their “reciprocal allegiance” in their adherence to the same discursive ensemble (63). Thereby the only requirements for belonging to a certain group are the recognition of the same truths and adherence to the same endorsed discourses.

5.1.2 Institutions

In the discursive mind-set, Foucault repeatedly refers to the power of institutions. He describes institutions to be a tool of the state to renew, reinforce and maintain appropriate discourses. For example, politicians maintain superior power through the control of

educational institutions in regards to what discourses, i.e. what “truths” that are presented for children. His perhaps most well-known analysis of the power of institutions is his analysis of the “Panopticon” prison design, which was developed by English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, in 1791. The model was designed to meet the demand for more effective

monitoring, for institutions requiring observing, i.e. prisons, hospitals, schools, factories etc. The design was constructed around the issue of how the majority could be monitored by the minority, and was therefore designed with an inner tower, and an outer ring of cells, which at all times could be monitored from the inner tower (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 337). Foucault later described the panopticon design to be an expression of a system, which through monitoring, shapes and controls the way we live our lives. Andersen and Kaspersen argues that in Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison (1975) Foucault evaluates how this way of societal punishment gained power so fast. He concludes that what has caused the

effective change was the “process of discipline”, which he argues is an inevitable effect of a growing capitalistic society (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 337).

While institutions maintain the strong position in regard to forming society according to Foucault, he rejects the idea that power “belongs” to certain institutions. Instead, he believes that power precedes institutions, which means that institutions reproduce power, yet they do not produce it. In that sense institutions are operative instances, which integrate and reproduce already existing power relations.

Foucault is critical and reflexive about the unchallenged power exercised through institutions, however, he acknowledges the positive effects as well. In Naissance de la

Clinique (1963a) Foucault deals with the change in medical discourse from 1760 to 1810, and

recognizes that the power relations were essential for the positive change (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 334). The discussion on the central role of institutions in modern society leads us to the next concept from Foucault: “Power as discipline”.

5.1.3 Power as Discipline

Power as discipline can be argued to be the strength behind the discursive production of knowledge and meaning in modern society. Thereby, power is the force that drives

discourses. To Foucault, power is an abstract concept. He does not refer to power as a

resource or an ability that someone possesses. Neither he describes power as an institution or a structure, and nor does power takes specific time or place (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 340). Andersen and Kaspersen (2005) suggest that Foucault understands power as en

elementary force, which is essential to social formations, and a basic component for any social relation (340). Once again Foucault underpins the importance of understanding the twofold consequences of the system, arguing that the system is productive in producing positive docile subjects (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 338). He argues that the force of power is neutral in its form, and instead takes shape according to how it is exercised.

The previous example of the panopticon design and the norms and morals it strives to determine is a manifestation of the sovereignty of capitalism. The disciplinary systems and institutions of capitalistic societies construct firm discourses of “right” and “wrong”, “normal” and “abnormal”. Andersen and Kaspersen (2005: 337-338) argue that what characterise this form of disciplinary power is its hierarchical format and control. What is essential here is the idea that, while institutions and governments maintain a large influence on the disciplinary power, the power is additionally reproduced and maintained by

individuals. Sociologist Steph Lawler argues, that according to her understanding of Foucault, power is ‘…a force which works positively through our desires and ourselves, which sees categories of subjects as produced through forms of knowledge and which theorizes the relationship of the self to itself…’ (2008: 55). Power and knowledge thereby lead back to the dualism of modern ways of thinking. The dualistic categories that present our way of making sense of our surroundings are a product of power and the need for power to construct relations, which are determined by power itself.

5.1.4 Knowledge

Binding together the concepts of “power” and “subject position” is the issue of “knowledge”. Previous philosophers have proposed the idea that ‘the attainment of knowledge will set us free from the workings of power’ (Lawler, 2008: 56). In short the general understanding of previous philosophers was that knowledge equals power, and one could, therefore, obtain power by obtaining knowledge. This idea, however, presumes the idea of “true knowledge” and a “true self”, independent of the social world and the workings of power (Lawler, 2008: 56).

Foucault opposed this idea arguing that knowledge does not equal power, instead, he argues that the production of “truths” about the world is why power works. These “truths” become obvious and necessary within certain discourses or power relations and therefore form the foundation of a coherent and controlled social world, in which the individual is positioned (Lawler, 2008:56). This argument leaves us with the last Foucauldian concept prior to the discussion, “subject position”.

5.1.5 Subject Position

As mentioned above, subject positions are the positions and roles made available for subjects through their relation to the discourses. The attributes and personality of the subject are evaluated according to the norms and truths of certain discourses, and based on that assessment different subject positions are made available to the subject. Bang and Dyrberg (2011: 10) argues that one of Foucault’s main aims was to investigate under which historical and political conditions individuals become the object of knowledge, how it is problematized and finally, decide how the subjects are created and transformed within the idea of

During the cause of Foucault’s research, he maintained two different approaches to the construction of morality, and by extension the relationship of the self to itself. Initially, he referred to the “law-oriented morality”, which is justified through social control, exercised by organizing and regulating institutions. However, later he referred to the “ethics-oriented morality”, which allowed the idea of a reflective subject that is capable of acting according to its own considerations (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 342). Before this shift, Foucault was widely criticized for his disregard of the “reflective subject”. Psychologist Stephanie Taylor argues that the Foucault’s method was criticized as “deterministic”, as it did not allow focus to be on the people, but instead focused on free agents, i.e. meanings (The National Centre of Research Methods, 2015). The “law-oriented morality” assumed that only meanings shape people, and does not consider people to make meaning themselves, which was opposing the social constructivist idea of “human agency”.

The shift from “law-oriented morality” to “ethnics oriented morality” did not imply that Foucault opened up for the idea of an individual with original and “true” abilities and universal morals. Foucault argues that work by philosopher Claude Lévi-Strauss and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan showed us that ideas of “meaning” and “truth” ‘ probably was nothing else than a superficial effect … and what in fact permeated individuals, what existed to us, and retained us in time and space, was the system’ (Eribon, 1991: 336 in Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 335). Foucault stresses that individuals, i.e. subjects form themselves, and better themselves, according to the discourses that surround them and the social spheres in which they find themselves (Andersen and Kaspersen 2005: 343).

6 Analysis and Discussion

The understanding of the concept “discourse” is fundamental in order to comprehend all other work of Foucault, and I, therefore, find the need to recap the idea that

Discourses are not simply representations, or ways of speaking; they are what [literary theoretician] Edward Said (1991: 10) calls ‘epistemological enforces’, creating the rules of what can be said and thought about, and of how those things can be said and thought about… (Lawler, 2008: 57-58)

Discourses regulate what can be said and what can be understood, as well as ideas of what cannot be said.

With this approach to discourses, I will now proceed to analyse and discuss the empirical data. This chapter will begin with a brief outline of the themes found in the coding process. I will then continue to approach the material and theory from the research questions. I will identify discourses on ethnic minority children, and then continue to discuss the

consequences of the discourses in relation to the subject position of the children. Finally, I will reflect upon the ambiguity of the initiatives surrounding ethnic minority children.

6.1 Themes

In my coding of the three interviews, I found 6 overarching themes; language, discretion, the institution, culture and parents, the children, and initiatives and resources. Additionally, there were reflections on the theme of gender. However, similar to the

theoretical limitations that exclude the theme of gender, I have chosen to approach the gender descriptions from the interviews from the concept of culture. The themes will not be

individually elaborated upon, but will instead be dismantled in relation to the research questions.

6.2 Language as a Barrier

The empirical data of the thesis undeniably points to the importance of language. All interviewees point out that language is the foundation of all socialisation processes and for the well functioning of the child, and agree that one of the biggest challenges for ethnic minority children is language acquisition (See Appendices D-F). For my 4th interview question, INT2 argued that the language is the most evident challenge ‘… as demands from society increase, the more important it becomes to learn [the language]’ (See Appendix E). INT2 not only refers to the children, but to the family and the parents as well, as the acquisition of the Danish language will enable the parents to support their children

throughout their institutional life. On the other hand, if the parents speak faulty Danish, ‘the children will make the same faults’ (See Appendix D), and thereby inherit the same lingual errors.

The role of parents is always essential to the growth and development of a child. According to INT1 dialogue between parents and children is important, however, she argues

that some parents neglect this, yet unintentionally by some. She further argues, that toys and activities are not only exercised to entertain but should also be used to promote and motivate language development through dialogue (See Appendix D). Thereby a part of a beneficial parent and pedagogue relation is the exchange of, and dialogue about, methods that can increase the language acquisition of the child. Equally, The Inclusionguide stresses the importance of a meaningful linkage between the institutional life and the family life, and suggests that parent corporation should be a priority to achieve such a connection

(Inclusionguide, 2010: 11).

INT1 expresses that the most important issue in the work with children with a minority background is adequate initiatives and support in their development of the Danish language, as well as their mother tongue. She argues that it is possible for children to comprehend two languages, but emphasises the importance of institutional support in the learning process, as the capacity of their vocabulary tend to be limited. Similarly, INT2 argues that the parents should present some culture from their country of origin so that the children will practice their mother tongue as well (See Appendix E).

The Inclusionguide supports this argument and argues that to be included as a valued member of the group, the child must be able to communicate with a clear objective. To reach this requirement, the institution, the management as well as the parents must support the children in acquiring knowledge and understanding of language, concepts and symbols so that the child is able to communicate with objectives (Inclusionguide, 2010: 22). In that sense, the Inclusionguide probe beyond the mere case of the spoken language. The knowledge of concepts and symbols that directs language can be argued to imply that the children must come to understand the contents of the discourses of the institution.

INT1 argues that the stories of H.C Andersen, among other things, are well known by most children in the institutions, and therefore lacking knowledge of his stories can lead the child to be excluded from a conversation or games about an H.C. Andersen story (See Appendix D). It is thereby not only important for the children to learn sufficient Danish to express his or her own feelings, but it is also important to understand the language of others and to know the cultural references that the other children use. That understanding can be argued to be the knowledge of the discourses that exist in the institution.

INT3 acknowledges that she, in some situations, have found herself using the “teaching tone” to a much larger extent towards ethnic minority children than she does towards the “Danish-speaking children”. She describes the “teaching tone” as a more didactically way of speaking, for example, ‘this is the red ball, this is the green ball’ (See

Appendix F). She stresses that this issue is something that she discusses with her colleagues, and she expresses conscience about this, as she acknowledges that excessive use of the tone will have a bad influence on the children in the long run (See Appendix F).

Foucault argues that subjects are defined from the relations they find themselves in, and additionally that all relations are some sort of power relation. Similarly, power is always relational (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 342-343). Thereby Foucault argues that the world, and the subjects and the power within, are based on some sort of relation. Communication in any form precedes relations, and the empirical data and Foucault thereby find a common ground in the sense that language, both in the spoken and unspoken form, is foundational for the well functioning of the subject. This section has identified discourses, which value language skills to be foundational for an equal dialogue. The lack of language skills thereby categorises many ethnic minority children as “vulnerable”, and in extension as “abnormal” according to the discourses surrounding language.

6.3 Discourse of Discretion

Discretion, and to some extent avoidance to talk about ethnic categorization, can be argued to be an important part of the discourses on ethnic minority children in the

Copenhagen preschools. In retrospective, these discourses of discretion were also visible during my initiation process. I prioritised the wording of my definitions and questions in order to approach the issue the “right” way. Thereby, I am similarly influenced by the discourse of discretion. This sensitivity can also be detected in the transcript of interview 1, in which I ask INT1 if she works with ethnic minority children in her everyday job. She replies ‘I do. a lot actually… Or what do you mean? Other ethnic? …Yes, that should cover it’ (See Appendix D). This statement underlines that INT1 wants to make sure that she understands correctly and that the term does not include any hidden implications. Thereby she expresses the need to make sure that her statements stay according to the rules of the discourses, which states that statements related to ethnicity, must be discrete and thought through.

The research does inevitably address the question of ethnicity itself, however throughout the interviews only very few ethnic categorizations were made. While she encountered the term ethnic minority children early in the interview, INT1 continuously referred to the children of interest as “bilingual children” (See Appendix D). While this can

be argued to be a result of her focus on language, it can also be argued to be a way of avoiding the use of ethnic categorization as the identified discourse ascribes.

Similarly, the Inclusionguide does not mention ethnic minority children explicitly. The introduction mentions that the guide shall promote inclusion for all children and youth, and ‘especially the children, who are at risk of getting in a vulnerable position, which can lead to exclusion’ (Inclusionguide, 2010: 10). While the ethnic minority children are not mentioned, it is evident that whoever is different, or has different prerequisites than the norm and the majority, is hoped to be included in the institutional life.

In his book The History of Sexuality (1978), Foucault discusses how the theme of sex and sexuality is controlled by rigid discourses, which determine what can be said, and who can say it. In this discussion, he mentions how silence and the avoidance to say certain things are very important parts of discourses.

Silence itself–the thing one declines to say, or is forbidden to name, the discretion that is required between different speakers–is less the absolute limit of discourse, the other side from which it is separated by a strict boundary, than an element that functions alongside the things said, with them and in relation to them within over-all strategies. There is no binary division to be made between what one says and what one does not say; we must try to determine the different ways of not saying such things, how those who can and those who cannot speak of them are distributed, which type of discourse is authorized, or which form of discretion is required in either case. There is not one but many silences, and they are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses. (Foucault, 1978: 27)

The silence of ethnic minority children in official documents, like the Inclusionguide, can thereby be argued to present a form of discretion, which are believed to be “correct” within the discourses encouraged by the state and the municipality.

The silence on ethnic minority children is an important aspect of the discourses, as it presents a strong expression of what can, and what cannot be said. Foucault’s concept of “governmentality” signifies a certain way to think about governing, and the mentality aspect suggests that these strategies are based on a historical and collective framework for thoughts (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 344). The silence of the Inclusionguide can, therefore, be argued to be the result of historical events related to ethnic minority children, or just ethnicity.

6.4 Institutional Reproduction of Discourses

The societal discourses presented in preschool institutions are important as they can be argued to be the child’s first meeting with society. INT2 maintains that it is where the child has its first meeting with the realities of society. ‘You can say that it is the child’s first meeting with the harsh realities actually’ (See Appendix E). All three interviewees

acknowledge their fellow responsibility for giving the children a good introduction to institutional life, which they stress, applies to both ethnic Danish and ethnic minority children. Nevertheless, they recognise, that in some cases of ethnic minority children, they are more aware of this introduction, as they estimate a lack of “understanding” of the system by the parents. INT3 gives an example of this, as she mentions the case of an Indian family, in which the parents understands the pedagogues as school teachers, and the pedagogues are therefore put on a pedestal by the parents (See Appendix F). The pedagogues consider equality as the core of a good pedagogue and parent corporation, and this incompatible understanding of the role of the pedagogues, therefore, become problematic.

Foucault stresses the importance of education as an instrument to access discourses, however, he also suggests that educational systems are possibly the single most important tool to control social appropriation of discourses. The preschools, as institutions, construct and distribute the “respectable discourses”, as well as constitute a “doctrinal group”. Foucault argues that education is a system of ‘…ritualization of speech, a qualification and a fixing of the roles for speaking subjects, the constitution of a doctrinal group… a distribution and an appreciation of discourse with its power and knowledges…’ (Foucault, 1970: 64).

Subjects that, someway or another, do not qualify to access the group, are thereby positioned in the institutional life based on their (power) relationship to the group and the respectable discourses. INT3 argues ‘when the language barrier is present, then you become an observer of [the world], instead of being a part of it (See Appendix F). Thereby the positions of ethnic minority children in the preschools are vulnerable, as some, through their linguistic insufficiencies, do not qualify for the doctrinal group.

The Inclusionguide addresses this issue and argues

‘In an including practice the focus is shifted from the insufficiencies of the child to the resources and contribution of the child, thereby the focus is no longer the child as an isolated individual, but on the child’s relations to the surroundings.’ (Inclusionguide, 2010: 11)

In Foucault’s approach, it is problematic to assume that focus on relations will provide a vulnerable child with dialogue, trust and equality. In section 5.1.3, I reflected upon the Foucauldian understanding of power as discipline and argued that according to Foucault power can be understood as an elementary force, which is essential to social formations, and a basic component for any social relation (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 340). With this argument I do not wish to suggest that an equal and respectful relation is impossible, however, I wish to emphasise again that all relations are infiltrated with complex power relations, which should not be ignored.

Pedagogues must acknowledge the power inequality in their relation to the children in order to “exercise” their power in a beneficial way. INT3 argues that she discusses these considerations with her colleagues ‘… we discuss the thing about the “teaching tone” a lot … because it causes inequality. [Whereas] If you have a dialogue, then there is equality’ (See Appendix F). However, as previously argued language skills precede the dialogue, and it is, therefore, difficult for some ethnic minority children to enter an equal dialogue. The powers exercised through institutions thereby maintain the ethnic minority children in a limited range of subject positions, which are usually categorised as outside the norm.

6.5 Discourse on Cultural Difference

As stated previously, discretion towards using ethnic categorization can be identified in relation to both the interviewees and the Inclusionguide. Instead of mentioning ethnicity the interviewees used the argument of something being “culturally different” repeatedly. The interviewees mention a common misperception of the concept of preschool. They argue that the concept per se is new, or have another meaning to some parents. INT1 mentions parents, who were not brought to such institutions growing up and therefore struggle to leave the responsibility of their children with the institution. ‘It is culture … it doesn’t come from their country to deliver the children [in institutions] … and in their culture you have to take care of your child yourself ’ (See Appendix D). She continues arguing that in some cultures, it might be seen as a bad thing, not looking after the children yourself, and they, therefore, strive to take time off work as much as possible (See Appendix D). However, she argues that in the “Danish perspective”, going to day-care and preschool are considered as essential steps in the language acquisition and socialisation process of children. The benefits of institutions are thereby recognised as “truth” or accepted “knowledge” in the “Danish perspective”.

In Les Mots et Les Choses (1966) Foucault argues that knowledge is bound to the historical and cultural context, i.e. knowledge is not universal (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 334). Knowledge is situated and contextual. The knowledge that children are required to have, prior to entering the Danish primary school, is therefore not “the one true

knowledge”. Conversely, the society and the Danish educational system are built up around the “Danish situated” knowledge, which has its roots in Danish history, and in extension the “Danish culture”.

In order for children to be able to keep up in the school system, INT1 argues that ‘they would have to attend at least three years of preschool … preferably more’ (See Appendix D). This argument is based both on the lingual requirements, but also largely on the cultural considerations. The Inclusionguide similarly stresses the importance of a structured and informed transition from preschool to primary school. Pedagogical curriculums and child environment evaluations are therefore implemented to provide a systematic collection of information about the child prior to the transition (Inclusionguide, 2010: 23). Yet, it is questionable if these sort of standardised tests correspond to the aim to recognise each child and its resources individually.

The Inclusionguide suggests that in order to obtain an including culture within the institution, there must be dialogue with the local community (Inclusionguide, 2010: 11). Similarly, INT1 proposes the guideline that institutions shall be able to present “the large society” within “the small society” of the institutions (See Appendix D). Thereby she suggests that institutions ideally should have dollhouses to represent houses, animals for nature or the zoo, a little play kitchen, books and pictures of forest and beach. In this way, the children can relate the ”reality” to some small models.

The knowledge of the national practices during certain celebrations, such as

Christmas and Easter, is similarly important to stimulate. INT2 argues that it is of course not required for the children to join the traditions, but being a part of society at large requires the knowledge of such traditions (See Appendix E), which will increase the feeling of belonging. INT1 mentions that, in some cases, the latitude of parents to introduce the societal

surroundings to the children can be problematic. She argues that some ethnic minority families, which have 7-8 children, do not have the resources to stimulate the children culturally (See Appendix D). She argues that practical errands, such as cooking and doing laundry, remove the focus from needs of the children (See Appendix D). If the children don’t experience their surroundings, they will fall behind both language-wise as, well as in their range of reference points. INT1 argues that a normal way to react to this kind of social

exclusion is to exit the situation silently. The lack of knowledge about the surrounding culture is then argued to cause the children to be left out, and thereby positioned outside the “respectable group” defined by the discourses.

6.6 Discourse on Modernity and Progression

Based on the interviews discourses on modernity and progression can also be sensed. INT1 repeatedly return to the idea that, some children come from cultures or countries that live by practices, which in Denmark, are considered out-dated. It can be described as

different discourses, in which the norms of the practice of raising children are very different. INT1 gives an example, in which she visits bilingual families to talk about lingual

development. She argues ‘… only in two out of ten homes they had a book for a child. And then we can begin to think about Denmark in… I mean before the 1950s right?’(See

Appendix D). Both INT1 and INT3 mention the case of “Muslim boys” or “Arabic boys”, and INT1 again implies an out-dated approach to gender, she argues

…within Islam, boys are looked upon differently. You begin to raise them, when they are quite a bit older right? And the girls they are, like, they have to help, and be like their mother, and they have to show affection. (See Appendix D)

This argument contains several interesting topics. To refer practices to a significantly

different time in Danish society carries the expression of discourses, which are motivated by different intentions and, which are therefore difficult to combine.

Secondly, the statement and the tone it conveys are clear expressions of an unequal power relation, a power relation based on the idea of “ true knowledge”. As Foucault notes, the idea of something “true” is fundamental to discourses, and in this case, the discourses are presented through their own idea of “true”. The Danish discourse on the practice of raising children is thereby based on the idea that modern Danish society has gained more access to the “true knowledge” of raising children since the 1950s, and that the practices of some ethnic minority parents thereby deviates from the “right” way of raising children.

6.7 Subject Positions

As described previously it was a central claim of Foucault that the subject itself is produced in discourse, ‘… discourse themselves were the bearers of various

subject-positions: that is, specific positions of agency and identity in relation to particular forms of knowledge and practice’ (Stuart Hall, 1997: 303). Thereby the subject’s relationship to, and compliance with, the recognised knowledge and practices of a certain discourse produce certain subject positions available for the subject. INT3 argues that language, but also the cultural background can affect the children’s relationship to the curriculum and the

expectations of the pedagogues, which can be argued to express the recognised knowledge and practices of the discourses. She states, ‘it is probably generalising, but there are some, Arabic boys, who have incredible few rules at home, right? And they are not used to getting corrected in any way’ (See Appendix F). The children are not used to being told no or being corrected, and the children are therefore surprised and overwhelmed if the pedagogues

correct them (See Appendix F). Thereby the knowledge and practices of the children’s homes become significantly important.

I do not wish to locate a responsibility for the discrepancy between the discourses in the institutions and the discourses in the family spheres. However, I wish to argue that the ethnic minority children often do not have an influence on, or power to change, the subject positions made available through the discourses reproduced in the Copenhagen preschools. While the pedagogues argue that they strive to obtain a relationship of equality and trust with the parents, the clash of discourses are difficult to address. The fine line between cooperation for the benefit of the child and invasion of the private sphere can be understood differently. Yet, negligence of addressing such issues carry significant social issues for the children as mentioned above. INT3 argues that the children, who are missing boundaries at home and are also lacking language, sometimes develop some adverse forms of behaviour to order to obtain status, which they can’t achieve in other situations. That could, for example, be to ‘…take the lead in doing different forms of mischief, or maybe lie a little’ (See Appendix F).

Pedagogues and parents are challenged in their cooperation. Situations like the one mentioned above can cause the children to be categorised as, for example, “troublemakers”. The discrepancy between the expectations of the parents and the expectations of the

pedagogues cause the child to be defencelessly categorised as “wrong” or “abnormal” according to the discourses reproduced by the institutions. In order for the child to obtain the possibility to adhere to “the normal” within the institutional discourse, it can be argued to be essential that institutions and parents understand each other, and find a common ground for the development process of the child.

Yet, returning to the arguments on the power of institutions and institutions as a tool for state regulations of discourses, this can be argued to be impractical. It would require

increased flexibility from the parents, however, it would also require institutions to

consciously think about the discourses they represent and actively work to understand and accept that there are other equal discourses. Yet, it can be questioned whether it is possible to regard other discourses as equal, understanding that discourses, as well as society, are based on dualistic assumptions and controlling power relations. This leads me to my last argument on the ambiguity of initiatives.

6.8 The Ambiguity of Initiatives

The question of initiatives, and in extension resources, is where the Inclusionguide and the interviewees can be argued to disagree. The Inclusionguide argues that the key for using the resources correctly is to work systematically, be in constant dialogue about how pedagogues can increase the inclusion level, and develop a varied organisation of the activities, for example, change in group structures (Inclusionguide, 2010: 15; 18). However, the interviewees stress the urge for more resources, as they struggle to find enough time to exercise their professional intentions and skills in depth, in their work (See Appendix F). For example, INT1 implies that the individual time for each kid is so limited, that in order for the pedagogues to have half an hour of dialogue, they would have to be on their ways to the emergency room (See Appendix D). While this is perhaps an exaggeration, it is a clear symbol of the frustration she experiences in her work.

INT1 argues that the children-pedagogues ratio should be linked to how many bilingual children there are, as they require more time and dialogue (See Appendix D). She states that if the system would invest more in language for all age groups, they would see significant improvements as ‘language is the thing that binds everything together’ (See Appendix D). Additionally, INT2 criticises the way the assessment of pedagogical work is done, as municipalities send out forms for pedagogues to assess whether the child

understands certain words (Inclusionguide, 2010: 23). According to INT2, that procedure is not what lingual improvement and understanding are about. It is about understanding the situation or context in which the word is said (See Appendix E). These statements begin the discussion of how the governments assess the state of institutions.

In the Inclusionguide, it is argued that the focus should be shifted from the defects and weaknesses of the child to the child’s resources and contribution to the group (2010: 11). In this way, the focus is shifted from the adaptability of the child to the inclusion of the institution. However, as INT2 notes, the municipalities, by request of the state, send out

structured and fixed schemes for pedagogues to assess the level of inclusion. In a theoretical perspective, this situation can be argued to be an expression of the issue of “power as

discipline”. To be able to maintain power the government must, as a minority, use these kinds of regulating tools to control and from the majority, i.e. the population. The modern way of governing is, according to Foucault, closely linked to the constitution of the economy as a reality, as well as, the invention of the population as an object for the states to regulate (Andersen and Kaspersen, 2005: 334). Following Foucault, the only ways for modern governments to govern is by using the tool of power as discipline, and measure their influence through regulating tools, such as the inclusion schemes.

7 Conclusions

The aim of this study was to investigate the discourses on ethnic minority children in the Copenhagen preschools. Based on the findings, I continued to discuss the implications the discourses have to the “subject position” of the child. Empirical data was collected through three semi-structured interviews with employees at preschool institutions in Copenhagen, Denmark. The “Inclusionguide” issued by the Municipality of Copenhagen was used as secondary data to support the empirical data. The following were the research questions.

1. What are the discourses on ethnic minority children in preschool institutions in Copenhagen, Denmark?

2. What implications do the discourses have on the subject position of ethnic minority children?

7.1 Results

Based on the analysis this study has been able to identify several elements in discourses on ethnic minority children in the Copenhagen preschools. On one hand, the pedagogues and the Inclusionguide express, directly or indirectly, a desire to provide an inclusive

environment for ethnic minority children, and value the resources of each child. However, discourses of ethnic minority children are permeated with a historical dependent avoidance to refer directly to the ethnicity of the children. Due to this silence the content of discourses are hidden by discretion, nevertheless, they exist.