Examining play behaviors of

children with internalized

emotional disturbances in

preschool context

A systematic literature review

Alice Meropi Batsopoulou

One year master thesis 15 credits Supervisor

Interventions in Childhood Madeleine Sjöman Examinator

ABSTRACT

Author: Alice Meropi Batsopoulou

Examining play behaviors of children with internalized emotional disturbances in preschool context

A systematic literature review

Pages: 56

Child initiated play appears as a means for children to express their inner world and personality and works as a milestone promoting their overall development. Internalized emotional disturbances constrain children’s functioning and have an impact on their general behavior, hindering their development. Most of the times, it appears challenging for teachers to identify a child with internalizing problems in the preschool classroom and most interventions are targeting children with externalized problems. Since play is a way for children to express, observations of children’s behavior while playing, provide information about their inner thoughts and concerns. The aim of the present study was to identify play behaviors and tendencies in types of play that children with typical and atypical internalized emotional disturbances show in free play situations in preschool. A systematic literature review was conducted in order to reach this goal. Six articles were included in which five internalized emotional disturbances were mentioned -one typical and four atypical. Findings revealed eight overt play behaviors, with prevalent these of non-play, solitary-passive behavior, unconscious play activity and desire for peer play but no attempt for it. Regarding engagement in play types, children exhibiting internalized problems were more prone to constructive and creative play and less engaged in symbolic play, which can be possible indicator of developmental delays. This study works as a tool for professionals in order to identify play behaviors of children with internalized emotional disturbances in preschool child initiated play. Subsequently, the findings assist interventionists on providing adequate support and clinicians on shedding light on the dubious field of emotional and behavioral disorders in early childhood.

Keywords: child initiated play, play behaviors, play types, internalized emotional disturbances, kindergarten, free play, preschool Postal address Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation (HLK) Box 1026 551 11 JÖNKÖPING Street address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036–101000 Fax 036162585

2 Background ... 1

2.1 Child Initiated Play (CIP) ... 1

2.1.1 Piaget’s constructivist theory about play ... 2

2.1.2 Types of CIP ... 3

2.1.3 The benefits of CIP ... 4

2.2 Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED) ... 5

2.2.1 Common IED ... 6

2.2.2 Preschool children with IED ... 9

2.3 Play behaviors in preschool context ...10

2.4 Engagement ...11 2.5 Aim ...12 2.6 Research questions ...12 3 Method ...13 3.1 Search procedure ...13 3.2 Selection criteria ...13 3.3 Selection process ...15

3.3.1 Title and abstract screening ...16

3.3.2 Full text screening ...16

3.4 Quality assessment ...16

3.5 Data extraction ...18

4 Results ...19

4.1 Information about the selected articles ...19

4.2 IED being mentioned in the selected articles ...21

4.3 Play behaviors being identified ...22

4.4 Types of CIP children manifesting IED tend to engage in ...24

5 Discussion ...27

5.3 Methodological issues ...32

6 Conclusion ...33

References...34

EBD Emotional Behavioral Disorders GAD Generalized Anxiety Disorder IED Internalized Emotional Disturbances MDD Major Depressive Disorder

PTSD Post Traumatic Stress Disorder SAD Separation Anxiety Disorder SP Social Phobia

1

1 Introduction

Play in children’s life constitutes a developmental mediator, promoting their social and emotional skills; thus appearing as a way through which children unravel their inclinations and personal characteristics. Contrariwise, preschoolers with Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED), diagnosed or not, exhibit persistent dysphoric behavioral patterns that hamper their daily functioning and social involvement within preschool. Manifestation of IED can be a corollary of more severe disorders (including mental disorders) later in a child’s life and, epecially in preschoolers, etiology can derive from diagnostical, contextual or both factors. Therefore, observation of children’s play behaviors along with the types of play in which they show tendencies are crucial.

Hence, the research will help professionals obtain an essential insight of the etiological mechanisms underlying the social and emotional functioning of children with internalized emotional problems. Subsequently, the upcoming results may operate as a foundation for educators and interventionists to identify those children within the classroom and develop special support practices. This is justified due to the fact that most of the interventions being developed in preschool aim at children with externalized emotional disturbances (Cohen & Mendez, 2009; Gosar, Holnthaner & Praper, 2015; Gresham & Kern, 2004). Especially for children in early childhood education, understanding their behavior through several routine situations, as it is free play, provides assistance to interventions and play therapies targeting children with manifestation of IED. In addition, with the present research, clinicians will gain a better knowledge of the ambiguous area of preschool children’s psychopathology.

2 Background

2.1 Child Initiated Play (CIP)

In order for a well-rounded definition to be provided, firstly the term ”child initiated” shall be defined within preschool context. The term ’child initiated’ is based on children’s own interest and choices in activities whereby they can earn social skills and learn. Children are the actual ’leaders’ in the procedure and explore external stimuli depending on their own reasoning and senses (Lindon & Rouse, 2013). As a consequence, teachers have a minor involvement in child-initiated activities, leaving space for children to decide in what ways they wish to act and engage with people and objects in the learning process (Uren & Stagnitti, 2009).

Play in children’s life is a crucial component for their generic optimal development and hence it has also been declared as a fundamental right by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989, Art.31). Subsequently CIP, also known as ‘free play’, corresponds to types of play which the child takes the initiative to start and to be involved in, according to curiosity, personal inclinations and preferences (Frost

2 et al. 2008; Lindon & Rouse, 2013). The procedure of play is done spontaneously, following the child’s needs for amusement and occupation. It takes place both indoors and outdoors in the preschool environment with the use of both outdoor and indoor materials, such as natural resources, playgrounds and toys (Burdette & Whitaker, 2005). This procedure is deemed as educational as it is recreational for preschoolers, since it assists them on exploring the environment, receiving constant stimuli and improving their critical thinking (Roussou, 2004).

As it is defined ’child-initiated’ play, teachers have minor involvement in it. This involvement is restricted to allowing time and space, providing appropriate material, dissolving disagreements when needed as well as eliciting further possibilities for play (Craft et al. 2012; Frost et al. 2008). Namely, it is a child-led but adult-supported play, meaning that it enables children to learn by following their instincts and unfurling their imagination, however with proper adult superintendence (Rubin et al. 1976). As Lindon & Rouse (2013, p.6) stated ”through their personal choice, young children are busy directing their own learning”.

However, the cultural aspect of CIP is to be noted, since it does not carry the same meaning and significance in all nations. For instance, in Sweden CIP covers an essential part of early childhood education and higly contributes to the procedure of learning. Contrariwise in other nations as USA and Japan, CIP is mainly considered a way for children to enjoy their free time as a recess from the actual educational procedure (Izumi-Taylor et al. 2010). Of interest for the present study is also the educational aspect, thus to examine CIP as a holistic contributor in children’s learning and development.

2.1.1 Piaget’s constructivist theory about play

Within the wide spectrum of CIP, several play types are encompassed in early childhood settings and development. Regarding the latter, Piaget (1951/57) has established a breakthrough theory about play and its types as befitting the developmental stages a child goes through. Piaget stated that as children proceed along with their normal biological maturation, the play types, that they prefer, are being adapted to their cognitive and overall development. As the child moves from infancy to early childhood, the internalization of the different schemas that he/she gains through experiences –or as Piaget named it ‘assimilation’- is overt through several play types.

More specifically, until the child reaches the age of two and while going through the sensorimotor developmental stage, the mental representation of objects as well as child’s fantasy and imagination prevail on the play types. Thus, exploratory play is most common in this age. Subsequently, between the age span of two to seven years, namely in the preoperational stage, children are able to make symbolic representation of objects and pretend that the object can be something else, reaching the peak of their imagination skills. Speaking of imagination, in this age children are also prone to discover and unfurl their creativity skills and create stories and games. As named, symbolic and creative play types are prominent in this stage. Other types of CIP

3 pertaining to preschool age and contributing to the overall development of the child are also creative and constructive play. Talking from a societal perspective, children tend to be involved in more social and interactive types of play as they move from one developmental stage to another. For instance in the preoperational stage the play becomes more cooperative than it is in the sensorimotor stage (Pellegrini, 2011; Piaget, 2007). Thus, taking Piaget’s play theory into consideration, the different play types are adapted and appertain to the child’s age, cognitive functioning and developmental stage (Frost et al.2008; Piaget 1951/57).

2.1.2 Types of CIP

From a societal perspective, CIP can be solitary, cooperative or parallel (Craft et al. 2012). In solitary play, the child plays alone without mingling with peers. Cooperative play is when children are involved together into play situations, sharing and interchanging materials and ideas. Cooperative play is also known as associative, interactive or social play, since assisting on a child’s social development and competence. Consequently, in parallel play children play side-by-side, however without cooperating and interacting. (Anderson-McNamee & Bailey, 2010; Cornelli Sanderson, 2010; Craft et al. 2012).

Taking into consideration the above and according to preschoolers’ language skills and developmental stages, the most eminent CIP types pertain to children’s bias, experiences gained by their environment, imagination and creativity (Jamison et al. 2012; Piaget 1951).

Most common play which preschool children are involved in –and depending on the preoperational stage- is symbolic play. This type of play not only helps development but also indicates normal cognitive, social and emotional development in preschool children (Stagnitti & Unsworth, 2000; Uren & Stagnitti, 2009). As Uren and Stagnitti state (2009), it is the most social play and assists preschoolers to build social competence. Psychologists have attributed a number of synonyms for this play type regarding its characteristics. Thus it is also known as pretend or fantasy play. Namely, children use objects and materials (‘symbols’) in order to represent other objects as well as scenes from their everyday life experiences. They also attribute properties and characteristics to the objects. This type of play can additionally be a way for children to pretend to be another person and/or to have a specific property and characteristics, utilizing their imagination and creativity skills to a great extend (Hughes, 2012; Maxwell et al. 2008; Stagnitti & Unsworth, 2000; Uren & Stagnitti, 2009). Symbolic play also exists in the literature as role play, since preschoolers explore adults and their functions by engaging in them, hence imitating them on an imaginary level. Symbolic play is usually cooperative in the preschool context, where a group of children takes different roles (Hughes, 2012).

An eminent play type in preoperational developmental stage is also creative play. In this type of play children’s creativity and critical thinking are stimulated by a variety of simple materials, with and through which they discover new things such as combining different colors for a painting or using different materials for the same construction. As being mentioned on the definition of CIP, in creative play teachers’ involvement

4 is constrained on providing time and space along with all the available and appropriate tools for children, giving them the freedom to select among and express their fantasy in their own way (Hughes, 2012; Maxwell et al. 2008; Lindon & Rouse, 2013). Creative play is also known as expressive play and it can be cooperative, however it is mostly solitary or parallel, since children tend to be “lost in their own imaginary world” (Maxwell et al. 2008). This type takes part both indoors and outdoors where children explore nature or play in playgrounds. (DeVries et al. 2002).

Additionally, exploratory play is also a type of creative play where children utilize their senses of smell, taste and touch with a view to experiencing the function and/or texture of the things around them. However, it is more common in younger ages1 and conencted with the sensorimotor stage (DeVries et al. 2002;

Watterson, 2012).

Another common play type in the preschool context which children take the initiative to involve in is the constructive play. Namely, children use different tools and objects in order to make and construct things manually, utilizing their creativity and fine motor skills to the fullest (Wood & Attfield, 2005). Constructive play can also take place both outdoors and indoors, giving children the opportunity to ‘build’ their knowledge as they build things emerging from their imagination. This type can be solitary, interactive or parallel; however research has shown that it is the most common type in solitary or parallel play (Piaget, 2007; Rubin et al. 1976; Rubin & Coplan, 2010). Constructive and creative/expressive types of play are also known as manipulative play, since children have the ability to ‘manipulate’ objects by coordinating their fine motor skills (Child Development Laboratory, 2017; Drew et al.2008; Wood & Attfield, 2005).

It is essential to point out that all types of CIP enhance children’s gross and fine motor skills depending on the normative development and their developmental stage. However, this is only one aspect of the profits that CIP has to offer to early childhood development (Drew et al.2008; Milteer et al. 2012; Piaget, 2007).

2.1.3 The benefits of CIP

Plenty of studies and conventions have highlighted the importance of play in children’s development (Frost et al. 2008; Piaget, 2007; UNCRC, 1989, Art.31; Uren & Stagnitti, 2009) . Especially in preschool age, CIP is not only essential for learning outcomes but for a healthy mental, physical and social development as well. It stimulates the nervous system and assists the development of language, fine and gross motor skills (Anderson-McNamee & Bailey, 2010; Goldstein, 2012). Referring to children in preschool age and more specifically in ages 2 until 7 years old, the offer of CIP in their development is salient. Preschoolers are being involved unconsciously in an effective learning procedure; one that indirectly boosts them to develop their finesses and critical thinking in several situations, while at the same time they are utilizing their imagination to the hilt (Ginsburg, 2007; Lindon & Rouse, 2013).

5 Research has shown that during CIP, children optimize their brain functions and ameliorate their problem-solving ability to a great extent (Burdette & Whitaker, 2005). All these outcomes contribute on enhancing the preschoolers’ cognitive development and assist them on constructing their intellectual skills (Piaget, 1957; Roussou, 2004). Children also learn to share, sympathize and interchange ideas with others, improving their social skills and reinforcing their emotional development (Ginsburg, 2007).

Since teachers have a minor involvement in CIP, preschoolers are able to build up leadership skills and be familiarized with risk-taking and decision-making procedures; competences that are essential to adulthood (Ginsburg, 2007; Lindon & Rouse, 2013). Children become active helpers in their own general development being provided with the opportunity to explore their surroundings and evolve their creativity (Roussou, 2004). Nevertheless, preschoolers with manifestation or diagnosis of IED face serious difficulties expressing themselves in general, a fact that has an impact on their general development and socialization into preschool settings (Fantuzzo et al.2003). Many professionals identify and define the severity of preschool children’s emotional disturbance by how much they are playing, along with the level of their concentration during play activities (Millar & Almon, 2009). Therefore, it is of high importance to observe and measure the way that these children act and behave through play activity in preschool settings.

2.2 Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED)

IED appertain to the wide spectrum of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders (EBD). Children manifesting EBD are characterized by behaviors inconsinstent with their age group that affect their academic performance and social competence as well as hampering their functioning in everyday life situations (Achenbach & Ruffle, 2000; Heward, 2009). Some of these behaviors are apparent and frequent among children as it is anti-social behavior, aggressiveness and/or conduct disorder. However, not all of them are externalized and hence not being overt, especially if no proper diagnosis have been provided (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1978; Cullinan et al. 2004). As Algozzine (1980, p. 113) mentions, externalized behaviors are ”disturbing to others in the social environment” and internilizing behaviors are ”disturbing to the individual”..

IED are under the ’umbrella’ term of mental disorders -excluding mental retardations- and present inward, deviant from normal behavior patterns. These patterns are commonly difficult to be interpreted by professionals, because symptoms such as inappropriate cry, withdrawal and inhibition, are considered normal in young children (Quinn et al. 2000). Additionally most children with IED tend to somatize their emotional problems, complaining about constant pain or sickness, without any obvious medical reason. The diagnostical issues occur because, as it was stated above, most of these symptoms are normal reactions of children under certain circumstance (Achenbach & Ruffle, 2000; Cullinan & Sabornie, 2004; Luby, 2009).

6 The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)provides a well-rounded definition on Gresham and Kern’s chapter (2004) about IED characterizing them as “a condition exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree which adversely affects school performance” (pp. 263). As follows, the characteristics appertain to (i) difficulties in learning which are not attributed to intellectual, sensory or health reasons, (ii) an incapability to form and maintain teacher and peer relations, (iii) improper behavioral patterns and feelings under normal situations, (iv) generalized prevalent feelings of dysphoria and/or melancholia (v) a tendency of somatizing personal or school problems and connecting them with general fears (Gresham & Kern, 2004). It is also stated that IED expand in more areas than the social- emotional development, since they additionally effectuate disturbances on a child’s physical and cognitive development, thus they can easily lead to more severe delays (Lecavalier, 2006). Thus, critical attention has to be drawn on the common types of IED and their symptoms.

2.2.1 Common IED

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-5, APA, 2013) is the most common diagnostic classification of IED and of psychopathology in general. According to the manual, several symptoms and/or mental disorders are attributed to the spectrum of IED. It is of high importance to be noted that, even if the person only shows manifestation of IED, it is essential to address the different types of these disturbances, since the symptoms being occurred may eventually lead to a diagnosed clinical disorder (APA, 2013; Gresham & Kern, 2004). Among the most prevalent IED are Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Social Phobia (SP) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or mostly known as depression. All the above, except for the latter, appertain to anxiety disorders. Research has shown that anxiety disorders are among the most common psychopathological disorders in children and adolescents affecting 7 to 15% of the population. It is also common that two or more IED can occur together; a phenomenon known as comorbidity (Beesdo, 2009; Ollendick et al. 1994). Each of the above IED has several characteristics in order to be properly identified.

2.2.1.1 Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

The most well-known IED, with prevalence of almost 3% of the population, is Generalized Anxiety Disorder or GAD (ADAA, 2016). Namely, when anxiety is more than a normal reaction to a stressful event and lasts over a period of at least 6 months, the stress becomes a pathological and -in most cases- everyday condition. This intense stress is overt in multiple activities and situations. A person with GAD suffers from dysphoric thoughts and feels anxious even when no tangible stressors exist (Hintze, 2002; Kendall & Chansky, 1992). Most common symptoms of GAD include persistent and obsessive worrying even for minor daily problems, crying (especially to young children), inability to feel relaxed and concentrate to tasks and activities (regarding preschool), distress on decision making and difficulty in handling uncertain situations (Costello et al. 2005; Heimberg et al. 2004). GAD includes the somatization of the above symptoms. That is to say, the

7 person often exhibits fatigue, trembling and muscle tension, insomnia, sweating and/or headaches (Dugas et al.1998; Heimberg et al. 2004; Spitzer et al.2006). In short, GAD is overt and severe when the person has “pervasive worry about worrying” (Borkovec et al. 2004, pp.19).

2.2.1.2 Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is a type of anxiety disorder, mostly frequent in young children, normally aged from 8 months to 7 years old (Shear et al. 2006). SAD is the most common anxiety disorder in children under 11 years of age, with prevalence of 4% of the population worldwide (Masi et al. 2001). It is characterized by unreasonable and excessive anxiety after child’s separation from home and parents or other people that the child is attached with (Tonge, 1994). In the preschool context, the child appears extremely shy, usually manifests excessive crying and refusal to participate in activities. From a physical perspective, a child with SAD often complains about stomach aches, dizziness, headaches and general pains in the body (Francis et al. 1987; Tonge, 1994). Due to the fact that distress and worry after separation from parents is a usual and common phenomenon for young children, the situation is rendered pathological only if it occurs for more than 4 weeks and has an impact on the child’s academic and social competence (Gresham & Kern, 2004). In addition, SAD can be manifested in adolescents and adults too, however it is deemed considerably rare (Lipsitz, 1994

2.2.1.3 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) commonly occurs after a person’s exposure to an extreme, shocking and usually threatening stressor, bringing about continuous worry and fear in the life of the person. Most people display symptoms of PTSD after a traumatic incident (Gresham & Kern, 2004). However it must be pointed out that PTSD is only considered a pathological condition when it lasts more than one month and hampers the person’s concentration and functioning in daily life (Costello et al. 2005; Kendall & Chansky, 1992). With prevalence of 3.5% worldwide, PTSD causes three types of symptoms, named re-experiencing, avoidance and arousal symptoms (PTSD: National Center for PTSD, 2015). Re-experiencing symptoms come with flashbacks (reliving the trauma, causing physical symptoms such as sweating and/or fast heartbeat). Other symptoms are daunting thoughts and inhibition of the normative focus and attention of the person. Avoidance -as named- entails abstaining places, people and events that evoke the traumatic experience, while arousal symptoms are related to irritability, insomnia, outbursts and being constantly alert (Gresham & Kern, 2004; Horowitz, 1997; PTSD: National Center for PTSD, 2015).

In young children, the most prominent symptoms are acute nightmares and crying. However, in many cases aggressiveness is prevalent too, depending on the severity of the traumatic event (Gresham & Kern, 2004). Children at school usually complain about aches, experience acute stress and do not easily trust other

8 people. Symptoms begin, within 3 months of the traumatic event; yet sometimes can ensue years afterwards. Most common reason of PTSD in children is sexual abuse and exposure to the death of a parent (PTSD: National Center for PTSD, 2015).

2.2.1.4 Social Phobia (SP)

Social Phobia (SP) is currently considered the most common anxiety disorder, with 7% rating of the population universally (ADAA, 2016). A person with SP is characterized by excessive fear and stress regarding the interaction with the surroundings as well as speaking in public places. The reason above this is that the person is concerned about being judged and evaluated critically and negatively by other people (ADAA, 2016; APA, 2013; Black et al. 2005). More specifically, the symptoms include intense and pervasive distress in situations where the person encounters people. The distress also occurs when the person has to introduce oneself to unfamiliar people, is being watched while acting as well as being criticized (Black et al. 2004). The somatization of the symptoms in SP is of the most overt. The symptoms encompass physical manifestation such as trembling, fast heartbeat, dry throat, muscle twitch, excessive sweating and blushing (Costello et al. 2005). In extreme cases people with SP could faint, especially when they are in front of many people or an audience (Black et al. 2004).

In preschool context, children with SP face difficulties in peer interaction and in participating in the majority of the activities. Preschoolers with SP have the fear of being degraded, while it is extremely common to also exhibit low self-esteem and introversion (Albano et al. 2003; Reynolds, 1978). When referring to preschool children, nightmares of being humiliated in front of peers, is the most frequent symptom (Albano et al. 2003).

2.2.1.5 Depression (MDD)

Depression is considered the most severe psychiatric disorder along with schizophrenia (APA, 2013). Clinically, is mostly known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). It is also the most prevalent of the IED, being rated with more than 8% of the total population (APA, 2013; Kessler et al. 2003). MDD is considered a clinical condition when one or more major depressive episodes ensue for more than two weeks on a daily basis (Pietrangelo, 2015). These episodes include symptoms such as loss of interest for the majority of activities and daily tasks, insomnia or excessive sleep, loss of appetite and severe decline in energy (Kessler et al. 2003). On an advanced stage of MDD, the person feels unworthy, hopeless and helpless as well as having suicidal tendencies (Gresham & Kern, 2004).

Few incidents of diagnosed MDD have occurred in early childhood (Gresham & Kern, 2004). However, several researches have presented its manifestation (Egger & Angold, 2006; Kashani et al. 1997). Consequently, children with MDD are more likely to exhibit irritability in mood, rather than sad feelings (Egger & Angold, 2006). Other symptoms include poor self-esteem, withdrawal from the majority of activities

9 in school, lack of concentration, a decision-making inability along with somatic complains (Poznanski, 1979; Wagner et al. 2004). Depression commonly co-occurs along with one or more anxiety disorders as it happens with the anxiety disorders themselves. This co-occurrence is scientifically known as comorbidity (Beesdo, 2009).

2.2.1.6 Comorbidity

Comorbidity is the phenomenon when two clinical disorders occur together in the same person and normally interact; meaning the symptoms of both disorders can happen at the same time. This concomitant has an impact on the prognosis of both disorders later in life (Egger & Angold, 2006; Maj, 2005). Normally, some symptoms of several anxiety disorders overlap as it happens with GAD and SP (Maj, 2005). However, most commonly comorbidity happens with depression and a type of anxiety, as it is GAD or SAD (Gorman, 1996; Grensham & Kern, 2004). Considering this overlapping manifestation, most of the times it may be challenging to distinct the symptoms in the two different disorders on a person and especially on preschool children (APA, 2013; Egger & Angold, 2006).

2.2.2 Preschool children with IED

Despite the fact that proper diagnosis of IED in preschoolers has rather scarce evidence, several recent researches suggested that professionals should start scanning and examining possible symptoms of IED. This scanning has to start no later than preschool age with a view to preventing and averting the onset of more severe mental and psychiatric disorders (Cohen & Mendez, 2009; Egger & Angold, 2006; Kashani et al. 1997). Regarding the latter, research has proved that preschool children with manifestation of IED who do not receive early support, are more likely to develop mental illnesses, poor academic performance and serious dearth of social skills. This also brings about alienation and marginalization of the child in the upcoming school years (Egger & Angold, 2006; Feil et al. 2000). Additionally, unrecognizable manifestation of IED in preschool age could be associated with drug abuse and even delinquency in adulthood (Gosar et al. 2015).

In the last decade, the prevalence of preschoolers with multiple symptoms of IED has increased significantly up to 7%, especially in the age span of 2 to 5 years old (Brown et al. 2012). This means that one in five young children is at risk of developing a severe type of IED later in life, due to lack of identification in early years (Brown et al. 2012; Egger & Angold, 2006). The most common IED types that children are likely to develop later, are depression and anxiety disorders (Tick et al. 2007).

The appearance in preschoolers usually includes symptoms such as behavioral inhibition; meaning that the child shows self-restraint and is unable to express oneself. Other symptoms are withdrawal from social activities, alienation and automanipulative behavior (such as biting one’s nails, pulling his/her hairs etc.). Akin to these symptoms are excessive fear and anxiety for social interaction and difficulty to control emotions. Thus children appear to cry often (Braet et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2012; Egger & Angold, 2006). However, early

10 educators can only assume a possible onset of IED from such symptomatology, in view of the fact that multiple reasons can lurk behind such behaviors (Gresham & Kern, 2004; Quinn et al. 2000; Tick et al. 2007). Thus, observation on play behaviors within this category of preschoolers may shed light on the nosology of IED in early years as well as on possible treatment and interventions that can be implemented.

2.3 Play behaviors in preschool context

Behavior, in a broader sense, are deemed the internalized coordinated responses of an individual to internal and/or external stimuli. These responses can be actions or inactions (Purcell, 2008). A behavior is a mannerism of reaction, by which a person’s temperament is governed, towards environmental stimulus. That is to say, when a person is behaving, he/she is in total reciprocal action (or inaction) with his/her surroundings. Thus, the expression of a behavior requires an actor, a context and the interaction in between (Purcell, 2008; Skinner, 1976; Zuriff, 1985).

Speaking of preschool, children’s behavior while playing can take multiple shapes. From a societal perspective, play behaviors within preschool context can be prosocial, anti-social or asocial (Porter, 2007). Prosocial is the kind of behavior where children are governed by empathy, altruism and caring, aiming at helping their peers while playing (Porter, 2007; Santrock, 2015). In prosocial behavior the child voluntarily and positively cooperates with other children and plays harmonically with them. Contrariwise, anti-social behavior is characterized by aggressiveness, reaction to authorities (e.g. towards the teachers), anger and temper tantrums for no severe reason. Anti-social play behavior is also known as solitary-active play due to its characteristics (Porter, 2007). Namely, the child ends up playing actively alone as his/her behavior effectuates peer exclusion and rebuff. Solitary-active behavior violates the normal flow of social interaction during play (Pellegrini, 2011; Porter, 2007; Santrock, 2015). Regarding asocial behavior, children tend to withdraw from social play and reciprocal actions with peers. Instead, they prefer to alienate and play quietly alone. Thus this type of behavior is also referred as solitary-passive (Jamison et al. 2012). Solitary passive-play includes silent engagement in play activities, in which the child does not communicate or collaborate with other children to play (Jamison et al. 2012; Porter, 2007; Rubin & Coplan, 2010).

Besides the above mentioned behaviors, another type exists which is not in response to any kind of societal behavior. This is known as non-play behavior, where the children do not articulate any alacrity on involving in play activities (Rubin & Coplan, 2010). On the contrary, they seem fearful and hesitate to engage in any kind of play, either solitary or communal. They also appear to be unoccupied, looking other children play and just standing inside or outside the classroom. For the above reasons, this play behavior also exists in the literature as reticence and/or onlooking and appears with frequency of 20% in preschoolers (Piaget, 2007; Porter, 2007; Rubin & Coplan, 2010).

11 Apart from these salient play behaviors, several other behavioral patterns can be identified during preschooler’s engagement in play, which are in accordance with their temperament, mood induction and possible problems and disorders.

2.4 Engagement

Engagement can be widely defined as a person’s commitment into the environment (Fredricks et al. 2004). Moreover, the ICF-CY closely connects engagement with the concept of participation, delineating both as ”a person’s involvement into life situations” (WHO, 2007, pp.9). Thus, engagement and consequently participation are examined separately from the concept of Activity which appertains to the execution of a task. Engagement, such as participation, is a multifaceted concept which evolves over time (Almqvist & Granlund, 2005; WHO, 2007). Moving into preschool context, engagement is related to the time a child spends while being involved in a task, accompanied by adults and/or peers. This involvement assists the child’s development and well-being in the long-run (Sjöman, 2015). The same happens in child-initiated play. When children engage in play, they are involved in several activities, according to their preferences and spend time interacting with the environment and the people within it (Cielinski et al. 1995). Thus, it is the actual engagement in play –and not just the play itself- that promotes preschoolers’ social, emotional and cognitive development (Piaget, 2007).

As mentioned that engagement is a multidimensional concept, three types of it are determined in young children: behavioral, emotional and cognitive engagement. Behavioral engagement includes the idea of involvement in school and extracurricular activities and it is essential for academic achievement. Emotional engagement encompassess the interaction with teachers and peers, whereas cognitive engagement appertains to the effort that a child does to comprehend complex issues and master difficult skills (Fredricks et al. 2004).

12

2.5 Aim

The goal of the present systematic literature review is to identify and appraise previous studies that focus on play behaviors and tendencies in types of play that children with typical and atypical internalized emotional disturbances show in free play situations within preschool context.

2.6 Research questions

What play behaviors of children with internalized emotional disturbances are found in child initiated play?

In what types of child initiated play do preschool children with internalized emotional disturbances mainly tend to engage in?

13

3 Method

For the present study a systematic literature review was conducted. Several databases were used as a research tool, including key words. Namely, this method appertains to identifying, critically appraising and reporting with clarity the research having already been conducted within a specific topic. The appropriate research studies were selected after a number of inclusion and exclusion criteria has been applied. The method additionally incorporates the scrupulous analysis and the quality assessment of the collected data (Moher et al. 2009).

3.1 Search procedure

The search for this study was conducted in total three databases, more specifically in PsycINFO, ERIC and ScienceDirect. All the above databases carry researches from the field of education, psychology, occupational therapy, health care and clinical psychology, thus carrying relevant for the present topic information. A hand search procedure was also conducted in order to reach the maximum possible amount of relevant articles.The search was performed in March 2017.

The search words were selected according to relevance with the aim and research questions and also in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 3.1). A flowchart is exhibited in Appendix A, describing the overall search procedure. A combination of thesauri and free text key words was used in the two out of three databases, namely in PsycINFO and ERIC, while only free text was used in ScienceDirect. In all databases search words were used for the clusters ’play behaviors’, ’play’ and ’internalized emotional disturbances’. Applied filters (e.g. for Age group) and some truncations (*) of words were additionally implemented in the databases. In PsycINFO and ERIC, the search procedure was conducted in ”Advanced Search mode” whereas in ScienceDirect the search was done in ”Expert mode”. The total list with all the search words used in the three databases is appeared in Appendix G.

Some filters were also applied. In PsycINFO those filters appertained to the Age group ("Childhood (birth-12 yrs)" OR "Preschool Age (2-5 yrs)" OR "Infancy (2-23 mo)"), the Type of publication ("Scholarly Journals") and the Date Range (2000 to 2017). Accordingly, in ERIC the filters concerned again the Publication type (”Scholarly Journals”), the Education level ("Early Childhood Education" OR "Preschool Education" OR "Kindergarten" OR "Grade 1") and the Date range (2000 to 2017). Finally, in ScienceDirect only the date range was limited to 2000 until 2017 along with the publication type which was restrained to scholarly journals.

3.2 Selection criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria, as they appear in Table 3.1, were applied in order to facilitate the research and limit the number of the -appropriate for the topic- articles. Thus, the present study included only

14 articles that were peer reviewed, empirical studies and published from year 2000 until 2017. The purpose of the date restriction was to identify more current researches in order for the topic to be up to date. Regarding the sample, both clinical and nonclinical cases of Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED) were taken into consideration in the search procedure. The reason of the selection lies in the fact that preschooler’s nosology of IED is a field yet being examined, due to the fact that early childhood is an age that children still go under rapid social and emotional alterations (Egger & Angold, 2006).

Therefore, both children who were diagnosed and children with symptoms of IED were incorporated in the study, whereas children with typical development were excluded. The original plan was to limit the age span of the children to 3 to 6 years old, however due to the fact that only four studies were identified, the age span was expanded from 2 until 7 years old, hence including the first year of compulsory school.

Systematic reviews were also excluded since they encompass their own inclusion criteria. In this point it must be highlighted that two experimental studies were also incorporated. Thus, an experimenter and/or researches weres initiating the play and provided the appropriate material. Consequently they just observed the targeted children playing. The reason above this is that the adults did not lead the play and remained on observations. As it is mentioned in the one experimental study “these postgame waiting periods, each of which lasted 4 minutes, constituted the SolFP situation. It was the children’s behavior during these situations in which the authors were actually interested” (Mol Lous et al. 2000, pp.251). Additionaly, as it is stated in the other included experimental study ”the adult player conducted the session in a nondirective manner, showing interest, reflecting feelings or the content of the play, and gently facilitating play when necessary” (Cohen et al. 2010, p.166). Moreover, since the main focus of this study is observational studies in child initiated play, any kind of articles containing adult-led activities and interventions were excluded.

15 Table 31 Inclusion and Exclusion criteria (for title/ abstract/ full text screening)

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria Population

-Preschool children 2-7 y. with internalized emotional disturbances (clinical and nonclinical samples)

Focus

-Internalized emotional disturbances -Child initiated play

-Play behaviors

Publication type -Article

-Peer reviewed

-Full text available for free -In English

Published from 2000 until 2017

Design -Qualitative -Quantitative -Mixed -Adults -Adolescents

-Children <2y and children >7y -Children with typical development -Children with other disabilities

-Externalized emotional disturbances -Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) -Interventions

-Play therapy

-Book chapters -Study protocols

-Reports, working papers and other grey literature

-Full text to pay

-Other language than English -Published earlier than 2000

-Systematic Literature Reviews

3.3 Selection process

The results from the three databases used in the present study were transferred in and checked via Covidence, a web-based data extraction protocol used for the process of screening, extraction and analysis of the articles (Babineau, 2014). The total number of articles being identified was 854. A manual search was also applied, thus 7 more articles were identified. Therefore, the articles reached the number of 861 in total, of which 2 were duplicates hence automatically being excluded from Covidence. . The procedure on Covidence included the reduction of articles using the choices “Yes”, “No” and “Maybe” on title and abstract level and “Include”, “Exclude” on full text level. The manual search articles were not included on Covidence and they were examined separately. After title and abstract along with full text screening, the final selection included 6

16 articles that were totally adapted to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as they appear on Table 3.1. A flowchart displaying the total process of selection can be found in Appendix A.

3.3.1 Title and abstract screening

From the remaining 859 articles, 792 were reviewed on title and abstract level. The biggest number of excluded articles referred to measurements which focused on externalized behaviors and children above the age of seven years old (n=582). Another reason of exclusion was the adult-led play activities and the fact that the study focus was on children’s social competence and emotional regulation (n=147). From the remaining 147 articles of title and abstract screening, 56 articles were not available for free and 11 articles referred to wrong outcomes such as play therapies and interventional processes and 49 articles assigned children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Finally, 18 articles referred to the effect of a specific kind of play on children with emotional problems and teachers attitudes. Information about the number of articles and the reasons of exclusion can be obtained from the flowchart in Appendix A as well.

3.3.2 Full text screening

After the title and abstract appraisal of 792 articles, 67 articles were addressed for full text review. From the above total number (n=67), 23 articles were immediately excluded, due to the fact that they were not available for free. The remaining 44 articles were carefully examined first for meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria and then proceeding on methods and results part. Subsequently, 28 more articles were excluded from the research, since they concentrated on wrong study focus, which was mainly the academic performance, emotional dysregulation and social competence of the targeted group.

Another reason for exclusion was that many studies measured different behavioral outcomes and included children with externalized behaviors and specifically with focus on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) syndrome (n=19). This fact left the full text screening with nine articles. Three more articles were then excluded due to the fact that the results appeared disordered and confusing to interpret. Thus the outcome of the study was unclear. The above procedure left the present study with 6 articles in total for analysis, which were adjusted on an extraction protocol (see Appendix E).

3.4 Quality assessment

Reagarding the quality assessment, two quality assessment tools were used in the present study; one for the quantitative studies being included and one for the case study. As for the former, the Quantitative Research Assessment Tool (CCEERC, 2013) was utlized. Regarding CCEERC, the quality assessment tool is a means to evaluate the selected studies and facilitate the procedure of reviewing and analyzing the desirable results, depending on the quality of each included study. Thus, normally, articles with low quality are either

17 excluded from the research, or are viewed cautiously (especially when the number of included articles is below five, thus critically limited).

In the present study, the above tool was adjusted2 in order to justify the aim and research questions, hence

containing additional sections about peer review, aim and research questions, study design, control group as well as information about play behaviors and types of play. The rating of the tool was also altered to 2 for the highest, 1 for the medium and 0 for the lowest, since the official tool contained a scale of 1, 0 and -1. The official tool also included a ’Not Applicable’ (NA) option which was erased for the present study. Thus, the articles were assessed whether they presented a High, Medium High, Medium Low or Low quality (see Appendix C for final results). The final edition of the quality assessment tool included 17 items in total, being incorporated into 4 broad sections. Namely, the Article publication & Background section (i) included questions about peer review, aim and research questions, while the Method section (ii) incorporated questions about play behaviors types of play, study design, control group, population, randomized selection fo participants, sample size, response and attrition rate. The Measurement section (iii) contained questions about main variables or concepts and operationalization of concepts, whereas in the Analysis section (iv) information about numeric tables, missing data, appropriateness of statistical techniques, omitted variable bias and analysis of main effect variables can be found (see Appendix B for adapted version of the tool).

As for the case study being included, the Quality Assessment tool for Case Series Studies (NIH, 2014) was adapted. The above mentioned is an assessment tool provided by the National Institutes of Health, tailor-made for Systematic Evidence Reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines in order to gauge and examine the quality of a case study. Therefore, the article was assessed on a rating scale of High, Medium and Low quality. The official tool contained three possible answers of ”Yes”, ”No” and ”Other (CD, NA, NR)3 without rating

points. However, in the present study, the ”Yes”, ”No” and NR answers were used and were rated with 2, 1 and 0 points respectively, due to measurement convenience. The tool initially consisted of nine questions, where one more was added (regarding types of play) and one of the existed nine was adjusted for the purpose of the study (regarding play behaviors). Therefore ten questions in total were answered for the quality of the case study (see Appendix D).

After the assessment, regarding the quantitative studies, three were found of Medium High quality and two of Medium Low quality. Regarding th case study, it was rated as High quality (see Appendixes C and D for scores). Therefore all six studies remained for review and analysis.

2 The adaptation of the quality assessment tool followed Camille Richert’s (2016) structure, who used the same tool for her personal systematic literature review (see reference).

18

3.5 Data extraction

All data from the selected articles were transferred into an extraction protocol on an Excel sheet (see Appendix E for information that the extraction protocol contained). The procedure assisted the researcher on accumulating all the –relevant for the study- information into a tailor-made form, in order to facilitate the upcoming analysis of the studies. Therefore, the protocol contained five categories, along with their subcategories, fitting into columns on an axial system. The final form of the protocol consisted of 32 columns and seven lines. The categories and subcategories were formed in a manner which was compatible with and justified the research questions of the present study.

The first category appertained to General information. This category incorporated all the initiate information that a reader should know about an article. For instance, information about the name of the study, author, year along with some basic information about the study design and participants can be found in this category. In the second category, the Play behaviors were further analyzed into four subcategories: Non-play, Solitary-active, Solitary-passive and Reticence/Onlooking. The third category contained information about the Internalized emotional disturbances (IED), namely the type of IED, either typical or atypical (symptomatology) and possible cause of its appearance. Regarding the fourth category, the Free play formed a category with three subcategories: Types of play, Interactive/With peers, Indoors/Outdoors. It is essential to be mentioned that in all three above categories (Play behaviors Internalized emotional disturbances, Free play), ways of measurement were included as a subcategory. The scales, with which the play behaviors and engagement in play types were measured, are also mentioned in the protocol (see Appendix F).The fourth and final category was the Summary. In this category the findings and the limitations of each study are presented in a way that both the researcher and the reader can comprehend them. All the information on the protocol helped the procedure of analysis of the results. Further and more analytical information about the categories and subcategories can be found on Appendix E. The overall extraction protocol can be provided by the researches upon request.

19

4 Results

After the screening of 861 articles in total, six studies were found eligible for the present systematic literature review (see Table 3.2). Out of the six, two were experimental studies (Cohen, Chazan, Lerner & Maimon, 2010; Mol Lous, De Wit, De Bruyn, Riksen-Walraven & Rost, 2000), three were longtitudinal (Coplan, DeBow, Schneider & Graham, 2009; Coplan, Prakash, O’Neil & Armer, 2004; Nelson, Hart, Young, Yang, Wu & Jin, 2012) and one was a case study (Cath, 2009). Those studies were in accordance with the aim and the (2) research questions. All six articles were published between the date range of 2000 and 2016, as the inclusion criteria required. Additionally, four of the six selected studies (Cohen et al. 2010; Coplan et al. 2009; Coplan et al. 2004; Mol Lous, 2000) included a control group (children with typical development) in order to compare it with the target group. Due to convenience, the articles will be referred with the Study Identification Number while reporting the results (see Table 3.2).

Table3.2 Information about the total articles being included, along wth SIN*.

SIN Country Author

I UK Cath (2009)

II Israel Cohen et al. (2010)

III Canada Coplan et al. (2009)

IV Canada Coplan et al. (2004)

V The Netherlands Mol Lous et al. (2000)

VI China Nelson et al. (2012)

Note. SIN* = Study Identification Number

4.1 Information about the selected articles

Regarding the case study conducted in UK (I), a child (two years and nine monthsold) was observed over a period of 18 months during his staying at the preschool. The study was part of a larger (four-year) research project examining young children’s resilience and well-being. Some observations were also conducted at his home, in accordance with his parents.These observations were basically about separation and reunion moments with the parents. The study did not provide any further information about the scales and/or measurements being used for the observations and for assessing the child’s symptoms.

In the study conducted in Israel (II) the target group was compared with a control group. The target group constituted of 29 children three years and five months old to seven years old whereas the control group constituted of 25 children between four and seven years old. The target groupwas exposed to direct4 terror

attacks, while the control group was indirectly exposed to terrorism, since they were all living in outlying areas previously exposed to high levels of terrorism. Care was taken to match both groups of children in terms of

4 Direct exposure was defined as having firsthand experience with a terror attack themselves and/or an attachment figure.

20 age and the socioeconomic and educational level of their caregivers. The recruitment was made by school psychologist with the formal consent of all parents. The observations took place on the children’s preschool in Israel over a time period of 45 minutes for the target and the control group respectively. To rate and measure the videotaped play sessions sessions the Children’s Play Therapy Instrument–Adaptation for Terror Research (CPTI-ATR; Chazan & Cohen, 2003) was used. Questionnaires were also filled by caregivers and preschool teachers; however no further information is provided upon this.

In one of the two studies conducted in Canada (III), 12 targeted children were compared with a controlgroup of another 12 children both between the ages of three years and five months old to five years and five months old. After preschool teachers’ permission and parents’ formal consent the children were recruited from local child care centers, nurseries and preschools in a mid-sized city. The childrens’ symptoms were assessed by parents’ and teachers’ ratings who filled the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop et al. 2003). BIQ is a 30-item scale designed to asess behavioral inhibition in peer situations and in response to behavioral challenges and novel situations in general. The observations lasted for three days and were assessed by researchers using the Play Observation Scale (POS; Rubin, 2001). The other study being conducted in Canada (IV) consisted of 119 children between three and five years old who were recruited from local preschools and child care centers in accordance with parents’ formal consent. To assess childrens’ symptoms of IED parents filled the Child Social Preference Scale (CSPS) which measures childrens’ conflicted shyness, social withdrawal and social motivations in play. CSPS is a 14-item scale. For each scale the parents answered the question “How much is your child like that”. For the observations researchers used the Play Observation Scale (POS; Rubin, 1989) and the procedure lasted for six months. Within these six months each child was observed every now and then for three to four minutes during CIP until the researcher completed 20-minute behavioral observa-tions.

Considering the study from the Netherlands (V) eight children with diagnosed MDD were compared with eight non-depressed children, both aged between three and five years, 11 months old. The depressed children were diagnosed according to their clinical files which were in correspondence with DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. These children were recruited from two institutions for young children with somatic, psychiatric and psychosocial problems. The control group was recruited from an urban preschool. For both groups the formal consent of the parents was obtained; for the target group the psychiatrist of the institution also provided consent and the clinical files needed. The two groups were matching in age, group and socioeconomic status. It is to be noted that this was one of the two included experimental studies, thus the observation was conduct-ed only once for each child in both groups in a tailor-made room reminding a preschool classroom. The observation lasted 20 minutes in total and the researcher was merely involved providing the tools and asking questions. However no further information about the questions asked and scales or measurements for behaviors are given in the study.

21 Finally in the study conducted in China (VI) 506 children took part, aged three years and five months old to six years old. The recruitment was done from four full-day Chinese preschools after parental consent. Both variables of children’s symptoms and behaviors were measured by teachers ratings who filled the Teacher Behavior Rating Scale (TBRS; C. H. Hart & Robinson, 1996). TBRS assesses various aspects of behavioral outcomes in early childhood including subtypes of sociable, aggressive/immature, depressive and anx-ious/withdrawn behaviors. Teachers were asked to rate each child on behaviors while “thinking about the child’s present behaviors relative to others in this age group that you know or have known” (Nelson et al. 2012, p.86). The study does not provide further information about duration of observations and their content.

In all six articles the purpose of the observations aimed at watching and appraising the spontaneous actions and behavioral patterns that children were exhibiting during free play situations. The above information can also be seen briefly in Appendix F.

4.2 IED being mentioned in the selected articles

For the present study, various Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED) were probed –no IED was excluded during selection process. Thus, symptoms of five IED are addressed in the selected articles (see Table 3.3). From the five, only Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) was clinically diagnosed (article V), according to DSM IV-5. While in regards to the other four, the preschool children only showed manifestation. More specifically, one article (I) referred to mainifestation of Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), one (II) to preschoolers with symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), whereas manifestation of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) was the most prevalent (III, IV and VI). It is to be noted that in two articles, manifestation of GAD was comorbid with Social Phobia (SP) (IV) and MDD symptoms respectively (VI). Reports and questionnaires were filled by parents, teachers, caregivers and researchers in order to gather information about symptomatology of the IED along with the manifestation of play behaviors. On Appendix F more information for the above can be obtained along with the scales being used as measurements for the play behaviors and play types.

22 Table3.3 Types of Internalized Emotional Disturbances (IED), in relation to each article. Comorbidity was also taken into consideration.

Types of IED

(diagnosed and non-diagnosed)

SIN GAD SAD SP PTSD MDD

[diagnosed] [symptoms] MDD Comorbidity I X II X III X IV X X X V X VI X X X

Note 1. SIN = Study Identification Number. See Table 3.2

Note 2. GAD= Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SAD= Separation Anxiety Disorder; SP= Social Phobia; PTSD= Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; MDD= Major Depressive Disorder

4.3 Play behaviors being identified

In total, eight behavioral patterns were highly overt during free play observations. These were: Reticence/Onlooking (Non-play behavior), Solitary-passive (asocial behavior), Behavioral changes (’moody’ behavior), Interruptions during play, Unconscious play activity, Anti-social behavior/Morbid themes in play, Desire to initiate peer play, however fear of trying it and Repetitive actions during play. All the above play behaviors are presented in Table 3.4 in relation to the selected articles (SIN) and IED. Further analysis of each play behavior will follow, in correspondence with symptomatology of IED being found in each article.

23 Table 3.4 Play behaviors being identified, in relation to the IED and the selected studies.

SIN and IED

PB I [SAD] II [PTSD] III [GAD] IV [GAD & SP] V [MDD diagnosed] VI [GAD & MDD] Reticence/Onlooking (Non-play behavior) X X X X Solitary-passive (asocial behavior) X X X Behavioral changes (’moody’ behavior) X Interruptions during play X Unconscious play activity X X Anti-social behavior/ Morbid themes in play X

Desire to initiate peer play, however fear of

trying

X

Repetitive actions during play

X

Note 1. SIN= Study Identification Number. See Table 3.2 Note 2. PB= Play Behavior

As it appears in Table 3.4 the Reticence/Onlooking (Non-play behavior) appeared the most prevalent among preschoolers with IED. Four studies (III, IV, V, VI) hadthis behavioral pattern as a finding. Among the four was also the only study where MDD was officialy diagnosed. Hence, in this category preschoolers appeared to wander aimlessly, looking at peers playing (’onlooking’) with an indifferent and non-exploratory manner. They seemed reluctant (’reticent’) on free play activities and/or they did not show any purpose on playing.

24 Solitary-passive (asocial behavior) was the second most ubiquitous, since being identified in three out of the six studies (IV, V, VI). More specifically, preschool children who manifested symptoms of GAD comorbid with SP and GAD comorbid with MDD symptoms exhibited such behavior. Namely, they tended to alienate from the preschool surroundings, playing alone (”solitary”) and not interacting with other children (”passive”).

The third category named Behavioral changes (’moody’ behavior) was identified in only one article (V) as it is overt in Table 3.4 Only children with diagnosed MDD were found to alter their behaviors essentially fast during play. Thus, as it appears, they presented a more disorganized and disrupted play behavior, experiencing changes in their mood while being involved in free play.

Moving on, indicator of Interruptions during play was again only one study (II). It is evident that preschoolers with manifestation of PTSD tend to interrupt their play, showing less coherence and more disorganization during free play activities.

Subsequently, the behavioral pattern of Unconscious play activity was observable in two studies (II, V). Particularly, preschoolers with indices of PTSD and preschoolers with typical MDD showed that they did not had the insight of acting during play. This means that, despite the fact that they engaged in free play situations, they were not aware of playing. Thus, they could not experience the feeling of playing actively.

Regarding the sixth category of Anti-social behavior/Morbid themes in play, children with indicators of PTSD were identified (II). Preschoolers showed reactive behavior and negative feelings such as sadness. They also seemed to represent morbid and macabre themes during free play activities.

In one study (IV) the children showed the seventh play behavior, named Desire to initiate peer play, however fear of trying (see Table 3.4). This was the study in which comorbid symptoms of GAD with SP were presented. Namely, preschoolers manifested the desire of involving in free play with peers. However, they did not try to achieve it because of fear and reticence.

Considering the last behavior being identified as Repetitive actions during play (see Table 3.4) it was apparent only in one study (I). Specifically, as it is mentioned in the study the preschooler with symptoms of SAD enjoyed connecting and disconnecting, taking apart and fitting back together objects. He manifested considerable satisfaction when he managed connecting and fitting back objects, hence appearing to repeat such actions multiple times (see also Appendix F).

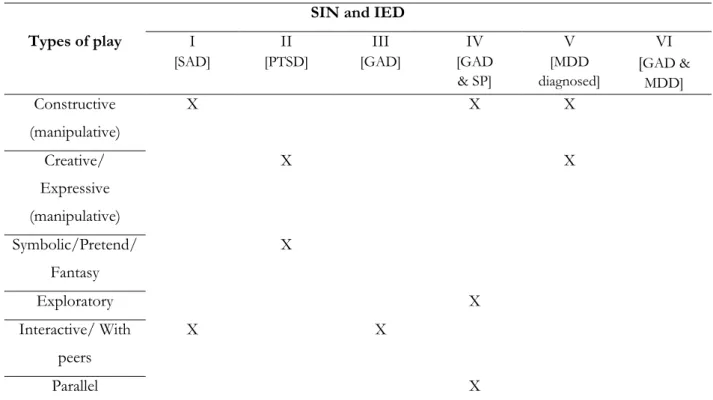

4.4 Types of CIP children manifesting IED tend to engage in

Regarding the second reasearch question of types of play preschoolers with IED mainly tend to engage in, the foundings detected six types in prevalence. These play types were Symbolic (also known as pretend or

25 fantasy), Creative (also known as expressive), Constructive, Exploratory, Interactive (with peers) and Parallel (communal type of play). Creative and Constructive play appertain to the category of manipulative play. Thus, when the studies referred to manipulative play, it was considered that both above types were of importance. Table 3.5 shows more analytically the types of play in relevance to the selected studies (SIN) and the IED mentioned within.

Table 3.5 Types of play children with IED tend to engage in, being identified in the selected studies. SIN and IED

Types of play I [SAD] II [PTSD] III [GAD] IV [GAD & SP] V [MDD diagnosed] VI [GAD & MDD] Constructive (manipulative) X X X Creative/ Expressive (manipulative) X X Symbolic/Pretend/ Fantasy X Exploratory X Interactive/ With peers X X Parallel X

Note. SIN= Study Identification Number. See Table 3.2

As it appears in Table 3.5, preschoolers with IED were mostly inclined to engage in constructive play. More specifically, three studies (I, IV, V) found prevalence of constructive play. Those were the studies in which children with symptoms of SAD, comorbid GAD with SP and clinically diagnosed MDD took part. Subsequently, creative play was also found to be popular among preschoolers with IED. Children with PTSD and the clinical sample of children with MDD tended to involve in this type of play (II, V). Regarding symbolic play, only children with PTSD symptoms showed preference of engagement (II). As far as exploratory play is considered, again only one study (IV) found indices of inclination among preschoolers. This study pertains to children with manifestation of comorbid GAD and SP.

From a societal perspective, in two studies (I, III) the preschoolers were occupied in interactive/peer play. However, regarding children with GAD, the study revealed that interactive play evoked them anxiety. Specifically, it was stated in the study that they were observed to display “overt indices of anxiety during free