,

STOCKHOLM SWEDEN 2020

Cross-Functional Team

Success Factors

A Case Study at a High-Growth Scale-Up

JONATAN AHLQVIST

EDWARD ALPSTEN

KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Cross-Functional Team Success Factors

A Case Study at a High-Growth Scale-Up

by

Jonatan Ahlqvist

Edward Alpsten

Master of Science Thesis TRITA-ITM-EX 2020:268 KTH Industrial Engineering and Management

Industrial Management SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM

Framgångsfaktorer för Tvärfunktionella Team

En Fallstudie av ett Snabbväxande Scale-Up

av

Jonatan Ahlqvist

Edward Alpsten

Examensarbete TRITA-ITM-EX 2020:268 KTH Industriell teknik och management

Industriell ekonomi och organisation SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM

Cross-Functional Team Success Factors

A Case Study at a High-Growth Scale-Up

Jonatan Ahlqvist Edward Alpsten Approved 2020-06-03 Examiner Charlotte Holgersson Supervisor Johann Packendorff

Commissioner Contact person

Abstract

In a growing digital economy, the possibilities for newly established companies are immense, and the market for innovative, disruptive products has grown exponentially. In this environment, single-person start-ups exist alongside billion-dollar organizations with thousands of employees. Somewhere in the middle, scale-ups have become an

increasingly interesting topic of study as they can be seen as the "successful" start-ups that are experiencing the transitional challenges of establishing themselves in an increasingly competitive market. As fast-growing scale-ups juggle customer's demand for new, innovative products/services alongside investor's demand for a viable business model, a need for a fast and adaptive product/service development environment arises. Here the concept of cross-functional teams becomes increasingly interesting as a tool for facing the challenges that such scale-ups face.

This paper is an exploratory case-study following a cross-functional team at a tech scale-up in the Stockholm region. The company currently inhabits the gaming market and offers B2C products/services to thousands of customers. This case study follows the cross-functional team from its early inception to the later stages of its progress. This paper draws conclusions for optimal conditions and success factors that allow for cross-functional teams to reach their full potential. Being a case study, this paper is also able to analyze how different contextual factors have implications on how

cross-functional teams operate. In the end, success factors are laid out, both generally and contextually, giving readers insights into the benefits and challenges that go hand-in-hand with cross-functional teams at high growth scale-ups.

Key-words

Cross-functional Teams, Organizational Communication, Organizational Culture, Business Stages, Emergent Networks, Stage Setting Elements, Enablers, Team Behavior

Framgångsfaktorer för Tvärfunktionella Team

En Fallstudie av ett Snabbväxande Scale-Up

Jonatan Ahlqvist Edward Alpsten Godkänt 2020-06-03 Examinator Charlotte Holgersson Handledare Johann Packendorff Uppdragsgivare Kontaktperson Sammanfattning

I en snabbväxande digital ekonomi är möjligheterna för nyetablerade bolag enorma. Efterfrågan efter innovativa och disruptiva produkter har vuxit exponentiellt. I denna miljö existerar det både små start-ups och miljardbolag med tusentals anställda. Någonstans i mitten mellan start-ups och miljardbolag finns det ett bolagsstadie som benämns scale-up. Scale-up kan ses som framgångsrika start-ups som handskas med de utmaningar som kommer med att snabbt växa och samtidigt konkurrera i en tuff marknad. Snabbväxande scale-ups behöver balansera kundernas efterfrågan för innovativa produkter/tjänster samtidigt som eventuella investerare kräver bevis på att företaget har en lönsam affärsmodell. För att uppfylla allt detta krävs det en snabb, innovativ och adaptiv utvecklingsmiljö för företagets produkter och tjänster. Cross-functional teams är en intressant modell för att hantera några av de utmaningar som scale-ups står inför.

Denna studie är en explorativ fall-studie som följer ett cross-functional team på en svensk scale-up i baserad i Stockholmsregionen. Företaget är en leverantör till gamingindustrin och erbjuder B2C produkter och tjänster till tusentals kunder. Denna studie följer ett cross-functional team från initierandet av teamet och under flera veckors tid.

Studien bidrar med slutsatser gällande vilka förutsättningar och framgångsfaktorer som bidrar till att ett cross-functional team kan uppnå sin fulla potential. Denna fall-studie bidrar också med insikter kring hur olika kontextuella faktorer påverkar arbetet för cross-functional team. Slutligen, presenterar studien olika framgångsfaktorer, både generella och kontextuella för cross-functional teams. Studien bidrar även med insikter gällande de olika fördelarna och utmaningarna som uppkommer om man arbetar med cross-functional teams.

Nyckelord

Tvärfunktionella/Cross-functional team, Organisatorisk kommunikation,

This study was carried out at fast growing tech-company in Stockholm and thus, both the success of this project and our positive experience, was solely in the hands of the case company. Therefore, we want to extend a massive thank you to everyone at the company who helped and welcomed us during our time there. We especially want to thank David for his continued support. By allowing us to write our thesis there, inviting us to meetings, and even setting up a bi-weekly advisory board to help us along with our thesis, he laid the foundation for the success of this research. On that note, we would also like to give a big thank you to our advisory board, Constanza, Gustav, Jamie, and David, who’s insights and advice throughout the project were invaluable. Another big thank you goes out to all the members of the cross-functional team for allowing us to take part in meetings, being open for interviews, and supporting us where necessary.

A final thank you goes out to our fellow students at the Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, for constructive feedback during the seminar series.

1 Introduction

3

1.1 Background . . . 3 1.2 Problematization . . . 5 1.3 Purpose . . . 5 1.4 Research Question . . . 5 1.5 Delimitations . . . 6 1.6 Outline . . . 62 Theoretical Background

7

2.1 Business stages . . . 72.1.1 Fast stage transition because of tech and venture capital . . . 8

2.1.2 Organizational structure at different stages of organizational development 9 2.2 Organizational Communication . . . 9

2.2.1 Communication Networks . . . 11

2.2.2 Emergent Networks and Interaction . . . 12

2.2.3 Organizational Culture . . . 13

2.3 Cross-functional teams . . . 13

2.3.1 Stage setting elements . . . 14

2.3.2 Enablers . . . 15

2.3.3 Team Behavior . . . 17

2.4 Our theoretical lens . . . 19

3 Research Design / Methodology

21

3.1 Research Process . . . 213.2 Research approach . . . 22

3.3 Research Design . . . 23

3.3.2 Rationale for selected company . . . 24 3.4 Data collection . . . 25 3.4.1 Daily Syncs . . . 26 3.4.2 General observations . . . 26 3.4.3 Interviews . . . 27 3.4.4 Interview Referencing . . . 28 3.5 Research Quality . . . 28 3.6 Method of analysis . . . 30 3.6.1 Interviews . . . 31

3.6.2 Observations: General and Daily Sync . . . 31

4 Empirical Findings

32

4.1 Stage setting elements . . . 324.1.1 Conveying the importance and priority of the project . . . 32

4.1.2 Presence of enablers in start-up meeting . . . 34

4.1.3 Setting goals . . . 34

4.1.4 Team composition . . . 36

4.2 Team behavior . . . 36

4.2.1 Communication . . . 37

4.2.2 Cross-functional Teams Role in Bridging Communication Gaps . . . . 38

4.2.3 Daily Syncs . . . 39

4.2.4 Location: Spending time together builds teams . . . 41

4.2.5 Leadership and Ownership . . . 42

4.3 Enablers . . . 42

4.3.1 Reinventing goals . . . 42

4.3.2 Limited involvement during the project . . . 44

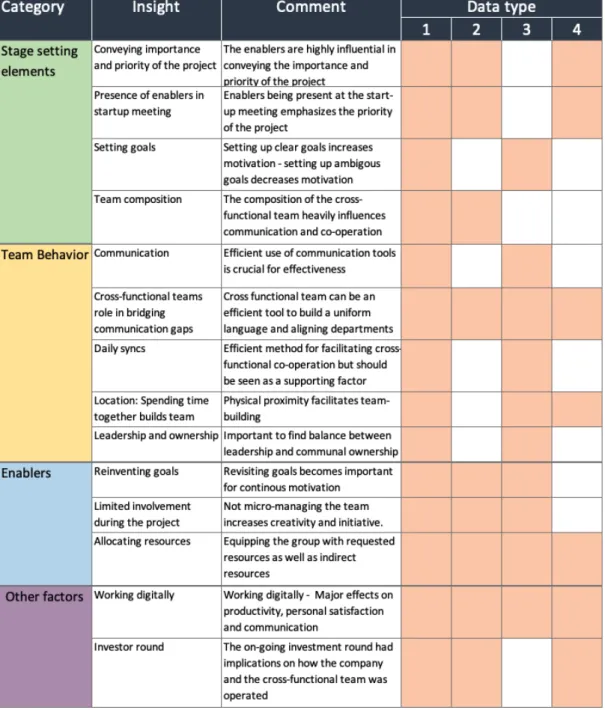

4.3.3 Allocating Resources . . . 44 4.4 Other factors . . . 45 4.4.1 Working Digitally . . . 45 4.4.2 Investor round . . . 48 4.5 Aggregated findings . . . 49

5 Analysis

52

5.1 General Analysis . . . 525.1.2 Initializing a cross-functional project . . . 54

5.1.3 Revisiting and reiterating priorities/goals . . . 56

5.1.4 Leadership and ownership . . . 58

5.1.5 Team building: Spending time together . . . 59

5.2 Contextual Analysis . . . 60

5.2.1 Aligning organizational communication . . . 60

5.2.2 Shared location for team building . . . 61

5.2.3 Investor round: Shifting priority . . . 63

5.2.4 Working from home . . . 64

6 Conclusions

66

6.1 Summary of Findings . . . 666.2 Relating to previous research . . . 69

6.3 Contributions . . . 70 6.4 Limitations . . . 70 6.5 Future research . . . 70 6.6 Managerial Implications . . . 71 6.7 Authors . . . 72

References

73

A Core Member Interview Questions

80

B Enabler Interview Questions

84

2.2.1 Communication Networks . . . 11 2.3.1 Success elements by category. . . 19 3.1.1 Sequential order of the research process . . . 21 3.3.1 Mock figure - illustrating the company structure and the members of the

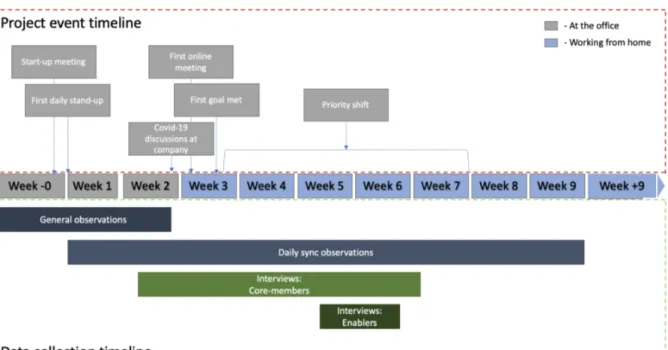

cross-functional team . . . 24 3.4.1 Timeline - of the project and the data collection . . . 25 4.5.1 Table of the empirical findings . . . 51

3.4.1 Table of Interviewees . . . 27 3.4.2 Table of Interviewees referencing . . . 28

Introduction

This chapter includes background and contextual information that introduces the reader to the setting in which this study is conducted and emphasizes its relevance. The chapter will also describe the problem at hand, how the research questions were initiated, and finally, how it was formulated. Shortly following, delimitations and overall structure will be presented for further context to the research.

1.1 Background

The majority of organizational research concerns start-ups and established organizations. However, another prominent business structure that often goes overlooked is the tech scale-up, ”also referred to as fast-growing market innovating new enterprises, disrupt and revolutionize entire industries. They embody ingenuity, innovation, and foresight” [13]. Scale-ups are often in a precarious market situation characterized by fast changing objectives, high growth, and hard deadlines. Timing is key [13] and therefore these scale-ups, which often have a newly established workforce, are forced to quickly adapt and maintain a fast-paced product development process. Therefore, cross-functional teams, which have seen an increased use with regards to complex and innovative products and services at at rapid development pace[46], are a potentially key structure necessary for scale-up success.

One industry that embodies fast-paced product development, innovations, and high growth is the gaming industry. The global gaming market amounted to $152 billion in 2019, with an average year-on-year growth of 13.5% since 2015 [51]. People who play video games spend more than 7 hours each week playing, with the playing time increasing by 19% since 2018.

Consumers of video games are often very engaged in their hobby and demand qualitative and innovative games and services [50]. Speed to market and continuous consumer feedback are important factors for companies in the gaming industry. The products and services released to the market are generally not fully finalized. As the consumers are using the product or service, the companies collect valuable user data that can be used to improve the product or service. Companies can use this valuable information to shorten the time to market for the product or service.

Numerous start-ups are founded in the high pace and lucrative gaming industry, and they are not uncommonly funded by external investors, such as venture capitalists [51]. Venture capital can provide companies with funding and business guidance. To monitor an investment or evaluate a future investment, venture capitalists request certain business and operational targets to be met [5]. Companies are fighting for the market’s attention by developing and offering innovative and competitive products and services. The rapid development and diffusion of technology as well as increased competition has spurred the need for complex and innovative products and services at a rapid development pace. The result is an increased use of cross-functional teams for product development and projects [46].

So what is a cross-functional team? A cross-functional team in an organization consists of members from multiple different functions. The members of the team are chosen based on the department they represent and the expertise they contribute with to the team. Most often, a cross-functional team is initialized when a project is complex, important and requires a wide range of experience. Cross-functional teams span over multiple departments in an organization to integrate diverse knowledge, skills, and expertise in the company [2]. Furthermore, the cross-functional team can be used to align the efforts of the cross-functional team’s project with the represented departments. When all members of the cross-functional team co-operate, utilize each individual’s expertise, and combine the sum of the team’s knowledge, the potential of a cross-functional team can be realized [32, 41]. Implementing a cross-functional team is a complex organizational effort with no guarantee of success. The performance and result of a cross-functional team depend on numerous factors, including the organizational context in which the cross-functional team operates and the internal infrastructure of the company [46]. Previous research has investigated cross-functional teams and their effect on performance [16, 17, 46].

However, there is little in-depth qualitative research and few case studies analyzing how different factors contribute to the success of a functional team and what challenges a

cross-functional team entails. Furthermore, there is little research concerning the effects of contextual factors, including size and industry, on the performance of the cross-functional team [46]. The aim of this study is to gain an in-depth understanding of how different factors contribute to the performance of the cross-functional team. Furthermore, the study examines the relationship between different factors. Also, the study examines the effect contextual factors have on the performance of the cross-functional team.

1.2 Problematization

As fast-growing, customer-facing scale-ups are juggling the customer’s demand for innovative and qualitative entertainment products/services alongside investors requesting a demonstration of a viable business model, a need for a fast and adaptive product/service development environment arises. As products/services need continuous iterations and improvements to satisfy the customer while also ensuring that the investor’s operational and business targets are met, the company needs a structure that captures the various and complex expectations that span over several departments. Hence, the challenge is to construct a team with representatives from several departments to combine their expertise and facilitate co-operation to face the challenges the customers and investors bring. While there is research covering cross-functional teamwork methods, there is little research about cross-functional teams in high-growth organizations in digital settings and what challenges and success factors that entail.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate how product development projects in fast growing digital scale-ups companies can be implemented using cross-functional teams and advance our understanding of what factors are important contributors to a successful project.

1.4 Research Question

RQ1: What factors are important to the success of a cross-functional team, and how do they influence the performance of the cross-functional team?

RQ2: What effect does a company’s contextual environment have on the performance of a cross-functional team?

1.5 Delimitations

For this project to be feasible within the allotted period, delimitations had to be made. The first delimitation (made when the project was first undertaken) was that the research was limited to a case study of the organization itself, where challenges and areas of research would be company-specific. While the first month of research involved thorough observations regarding the organization’s overall communication structure, a second delimitation was made, and the study was to be focused on a newly-formed cross-functional team at said company.

1.6 Outline

The report will follow this format:

1. Introduction: Introduction to the study. Problematization and research questions are presented.

2. Theoretical Background: This will serve as a platform for the theories that will shape the research as well as the theoretical lens with which the empirical findings will be analyzed. 3. Methodology: The research methodology will be described, and primary sources of data and analysis will be further developed.

4. Empirical Findings: The collected data will be synthesized and the primary empirical findings will be outlined.

5. Analysis: The empirical findings will be analyzed and previous research will be taken into account.

6. Conclusions: The research questions will be answered, reflections will be made and suggestions for further research will be presented.

Theoretical Background

In this chapter, the theoretical framework of the research topic is introduced through the reviewed literature. A deeper look into business stages and transitions are investigated and what implications it has on the organization. Then a definition of communication is presented, and organizational communication is elaborated upon with focus on communication networks and culture in organizations. Furthermore, a detailed overview of cross-functional teams and important factors for successful projects is made. Moreover, the relationship between communication networks and cross-functional teams is discussed. Also, the implications culture has on cross-functional teams are discussed. Lastly, the theoretical framework is proposed.

2.1 Business stages

A number of researchers have presented life cycle models to describe businesses progress through various stages as a chronological evolution of the businesses, from early-stage to mature companies [14, 27, 37, 42, 62]. Generally, the task of deciding on a specific definition of a stage/phase and setting the boundaries between them is ambiguous as the boundaries between the stages are fuzzy and often overlapping [53]. The life cycle models have differences in the number of stages and what activities and characteristics is associated with each stage, but generally, they follow the same progression of stages [40]. For example, Scott and Bruce [42] proposed stages are: Inception, Survival, Growth, Expansion and Maturity. Scholars commonly identify that each business progresses through different stages of growth, with varying problems and challenges which must be addressed and requires different management skills, priorities, organizational structures and processes. In each stage, the business is preceded

by a crisis/challenge, or a set of crisis/challenges. The business can either overcome it and progress/grow to the next stage, cope with it and remain at the same stage or be defeated by it and regress to the previous stage or die [40].

2.1.1 Fast stage transition because of tech and venture capital

For businesses in the high-technology context, it is not unusual to grow rapidly and grow from start-up to mature companies in just a few years. Businesses face crisis and challenges earlier and more consistently as the business progresses through the stages, as a consequence of the rapid growth [27].

A study of venture capital (VC) investment’s effect on entrepreneurial firms growth in Europe by Grilli and Murtinu (2014) concluded that investments from independent venture capital firms showed positive development and statistically significant impact on the firm’s growth in sales [25]. VC investments have a considerable positive impact on the growth of a firm’s sales and employment and contribute to the firm’s growth by: 1. Providing the firm with necessary funding for needed investments and expenditures 2. Being active in knowledge sharing and constituting a valuable coaching function. 3. VC investments are a signal of the quality of the firm for uninformed third parties which facilitates sales, partnering with other firms and attracts talent [5]. As a consequence of the rapid growth spurred by the VC investments, it is not uncommon that the firm faces crisis and challenges more often as the firm progress through the life-cycle stages.

Before venture capital investors invest in a company, they usually conduct a thorough due diligence of the company. Investors examine and evaluate the company’s current state and future prospects. The due diligence process can be quite stressful for the evaluated company as they are expected to provide the investors with requested data and proof that the company is moving in the right direction at the appropriate speed, showing that the company is a worthwhile investment. Companies that are looking to attract external investors are generally interested in presenting the best version of the company to the investors. Consequently, the company is focusing on improving areas of the company that they have identified to be especially important for the investors, ”dressing up the bride” so to say.

2.1.2 Organizational structure at different stages of organizational

development

It is a difficult task to determine communications strategies for internal organizational communication because they a reliant on whether the company requires high-efficiency communication or not [52]. What the company requires will then depend on its size and the situation for the company. These factors will vary significantly between different organizations, and there is no ”one size fits all” answer. Therefore an in-depth investigation is necessary before specific communications strategies are determined and implemented.

When taking a closer look at appropriate communication structures, certain questions become apparent: What type of company is it, what size is it, and what culture is present? An article by Kwiatkowski [38] mentions the importance of open and informal communication but stresses the difficulty of managing internal communication in larger companies. In the article, Kwiatkowski argues that it is much easier for a company with 15 employees and more difficult for a company with over 100 employees.

In larger organizations, many studies look at optimal communication structures and find both positives and negatives in formal and informal actively adopted communication structures. For example, an article by Ingvarsson and Strombäck [33] acknowledges findings from previous studies (Barret 2002; DiFonzo and Bordia 1998) that top-down structures are optimal in large corporations, but also acknowledges the problems with information being lost on the way. They, therefore, present the importance of having project managers placed in a more central role in the communication structure, being able to communicate both up and down and facilitating further conversations.

These more structured approaches to communication are, however, often criticized with regards to more creative fields and in start-up companies because they impede creativity and company performance. Kwiatkowski [38] suggests reinforcing the formal means of communication with informal ones.

2.2 Organizational Communication

When individuals interact, communication comes naturally and easy that few reflect on its underlying complexity. Communication is regarded as a back and forth process between two or more individuals. Communication must be done carefully and thoroughly encoded and decoded by all involved parties in order for the original message to make sense and resemble

the intended message. If the receiver does not give appropriate feedback to the sender, on the received message, the communication is regarded as not complete and is therefore ineffective [57].

Bolarinwa and Olorunfemi(2009)[7] define communication as a transactional means by which two or more people interact within a defined environment, how they are linked, and how they work together to reach a common goal. Schramm believed that an individual’s cultural background, experience, and knowledge affects how a message is received and interpreted. Individuals with diverse backgrounds, industry experiences, religions and cultures tend to interpret the message in different ways [57]. Robbins viewed communication as a transfer of meaning and understanding between individuals and comes in the form of messages, symbols or certain languages so that all individuals involved receive the information and understand the purpose of the information [55]. The audience that a sender intends to communicate with and what message is being distributed determines what communication tool is used [28]. In other words, communication tools can be e-mails, Slack messages, video conferences, meetings, notes, face-to-face interactions, etc.

There is research defining organizational communication [36][66], and the overarching idea is that it is the process of a [sender] relaying message to a [receiver] and the message being understood by both parties. While this definition seems simple enough, in practice, the process of communication can become far more complicated because of the intricacies within the organization and the organizational structure. The path that a message takes will vary based on an organization’s size, culture, and hierarchy and can, therefore, become distorted if these aspects are not clearly defined.

The importance of employee communication is brought up in many studies. A study by Watson Wyatt (2010) showcases the importance of effective communication within a company by drawing parallels between communication and return on investments (ROI); the study showed that “effective employee communication is a leading indicator of financial performance and a driver of employee engagement. Companies that are highly effective communicators had 47 per cent higher total returns to shareholders over the last five years compared with firms that are the least effective communicators” [64]. There are also intangible benefits of good communication, such as employee satisfaction, creativity, and engagement [34], aspects that are important in any firm, but even more so in firms in a high-technological context.

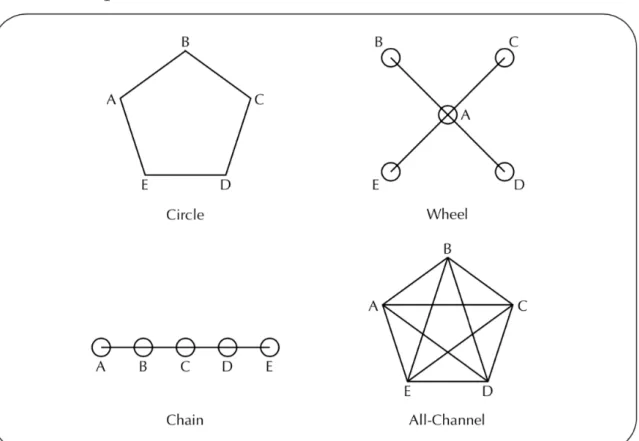

Figure 2.2.1: Communication Networks

2.2.1 Communication Networks

As researchers began to realize that the most important work in organizations was done by small groups of people, interest in communications networks increased [18]. It became increasingly interesting to look at what communication structures existed and how they affected performance. Shaw (1964) [59] drew images of potential communication networks for groups of three, four, and five persons where they were defined by dots and connecting lines that showed how communication occurred. These models have been continuously studied, and Scott (1981) clearly identified the four main small-group communication structures: circle, wheel, chain, and all-channel (see figure 2.2.1) [58].

These four small-group communication structures can be split up as being either centralized or decentralized. The circle and the all-channel network can be seen as highly decentralized, while the wheel and the chain network can be seen as centralized [18]. There are both pros and cons to both types of networks, and both have been seen as positive in different situations. Early on, it was recognized that the chain and the wheel networks (centralized) were much more effective than their decentralized counterparts. Leavitt (1951) showed this in terms of the speed in which

these groups were able to complete tasks [39].

Centralized networks can have drawbacks in certain aspects, compared to more decentralized ones. While centralized groups perform quickly and efficiently with relation to tasks that require efficient coordination, they do impede progress in tasks that are more ambiguous and complex [58]. In these types of tasks, the decentralized networks are often more efficient because they allow for open communication, which in turn can lead to error correction as well as creative thinking.

2.2.2 Emergent Networks and Interaction

There has been a theoretical distinction in communication networks where formal and emergent

networks have been studied separately as well as how they coexist within an organization [49].

Emergent networks can be seen as communications structures that emerge from formal and informal communication between people who work together [18]. In other words, emergent networks are informal communication structures that don’t follow the formal and mandated structure that would be depicted in an organizational chart but are built as a result of it. The reason that studying the emergent networks in an organization is important is that much of an organizations communication can be missed if only the formal organizational structure is analyzed [4]. Therefore, understanding where, why, and what type of informal communication is happening in an organization is equally important to understanding the established, formal communication structures. For example, while a certain work task is supposed to be relayed via company e-mail, it might instead be communicated at the water cooler.

These groups that emerge within the formal organizational structure will have implications on the interactions that occur within a company. The informal groups can span across departments, i.e. cross-functional groups, and will have an effect on the communication density within a company. As Eisenberg writes in his book [18], the communication density in a company is defined as the number of links (of people who communicate with each other) divided by the number of possible links if everyone at the organization communicated with each other. This density has been showing to have an effect on the speed at which an organization adopts to change [1]. High communication density companies have displayed a faster adoption of new technologies and ideas.

2.2.3 Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is something that is directly linked to communication within a company. It is commonly seen as the way people in an organization communicate, interact, and how decisions are made and conveyed [52]. This definition gives a general idea of what organizational culture is and why it is so important. Because it affects the way people interact, it will shape an organization’s change capabilities, communication channels, and to what degree employees work towards a common goal.

One of the leading scholars in the field of organizational culture is Edgar H. Shein (2004), and he defines organizational culture as: “A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solves problems of external adaption and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems” [60]. Culture can exist on multiple levels, and there are sub-cultures in different departments and groups of people in an organization. Culture can ease communication with people within the culture and hinder communication across cultures. Shein’s definition of culture makes the concept increasingly interesting because it showcases the tendency of culture being passed on within the organization. This has implications when a company expands because a culture that was deemed “valid” in a small company may not be equally valid in a larger organization, yet it could still be passed on.

Grey defines culture management as coming from the concept of ”personhood” and the benefits of having a driven workforce with a common goal[24]. However, Smirchich discusses the difficulties of managing culture because it is often ”uncontrollable.”[61] When managers try to create a culture that matches their own aspirations, it will sometimes not match the aspirations of the workforce. In these cases, employees can often resist and try to steer away from it. Campbell[11] argues that mission statements themselves are of very little value, and companies with good mission statements can still have unmotivated co-workers. Therefore, managers need to consider the culture that already exists and how it can be steered towards one that is beneficial to the company.

2.3 Cross-functional teams

The rapid development and diffusion of technology as well increased competition has spurred the need for complex and innovative products and services at a rapid development pace, with

the result being cross-functional development teams [46]. Cross-functional teams span over multiple departments in an organization to integrate diverse knowledge, skills and expertise which spurs creativity and innovation [2].

As earlier mentioned, communication networks that span over different departments is a natural reaction to projects or challenges that involve multiple departments in an organization. The characteristics of the project or challenge shape the structure of the emerging network [58]. One can argue that formalized cross-functional teams are a formalized answer to the spontaneous emergence of communication networks in an organization. The communication network is evidence for the need and benefits of establishing cross-functional teams in an organization, particularly in complex and innovative projects. As previously mentioned, there exist sub-cultures in an organization which can ease communication for members within that organization but also hinder communication across cultures. Cross-functional teams ensure representation throughout organizational departments and therefore allows the project to be shaped in a way that is optimal for represented departments and cultures.

The success of using cross-functional teams for product development is not guaranteed, and its suitability depends on the organizational context within which the cross-functional team operates, including the size of the firm and the industry in which the organization operates [29].

To better what factors contribute to the success of cross-functional teams McDonough [46] has divided the key variables for cross-functional team performance into three main categories, namely Stage-setting elements, Enablers and Team Behaviors.

2.3.1 Stage setting elements

Stage setting elements set the foundation and the purpose on which the work of the cross-functional team takes place [46]. Clear and consistent Goals equip the team members with a common frame of reference for all members in the group which facilitates co-operation [54]. Clear goals give directions to the team members on what actions to perform and what to prioritize [8]. Hence, appropriately set goals, increase the likelihood of project success. Cross-functional teams that are efficiently empowered performs better [8, 15]. Providing team members with greater decision-making responsibility lead to a higher degree of commitment and increase the probability of goal completion. Empowering a team also creates a performance-enhancing climate, as the team perceives their work and themselves as more influential. As a result, they are more motivated, and their personal satisfaction is higher [19].

Allocating decision-making authority at low levels increases the speed at which decisions can be made.

The Climate where the cross-functional team and the product development initiative operate affects the performance and result of the work. Management is mainly responsible for setting the climate for the effort of the cross-functional team and does this consciously or unconsciously [46]. One way for management to do this is by empowering the team members, and another one is to create a sense of urgency and importance for the project [48]. Thamhain [63] refers to this as a ”priority image”. To ensure that the team members are committed and excited about the project, it is the senior management’s responsibility to convey the importance of the project. The composition of the team members, i.e. Human Resources, is crucial for the success of any project/initiative. Senior management is responsible for setting the stage for the project by selecting the members of the team with the right technical and interpersonal skills [29, 68]. The knowledge and expertise embodied in the team members are one of the greatest strength of a cross-functional team. A great mix and fit of team members can increase the speed and quality of work, with a diverse set of perspectives being beneficial for the team [29, 46]. If the project is radical and innovative, it is helpful to choose members for the team that are new to the company [45], as new members not yet been coloured by the company culture and can bring new ideas to the table. Constructing a team from different departments with various perspectives, skills and knowledge can help the project to identify problems at an early stage, and fix them before they grow too big [46].

McDonough [46] means that the variables Goals, Climate, Empowerment and Human

Resources together constitute the stage setting elements and precedes the development

initiative. Management is mainly responsible for setting the scene for the development initiative, providing the team with clear expectations, instructions, resources and authority. The stage setting elements build the foundation of the development initiative, and a solid foundation will enhance the probability of success.

2.3.2 Enablers

Enablers are individuals who have the potential to enable the success of the cross-functional team. These individuals can facilitate the team’s efforts and support the development initiative. Enablers play different roles, including leading the team, providing support and championing the project [46].

the development process by working closely with the team and are in frequent contact with the team. Research on the relationship between the performance and leadership of cross-functional teams indicates that successful team leaders are not directly involved in the team’s efforts. Successful team leaders work indirectly to enable the success of the development initiative [10, 20]. In a study, McDonough and Barzak [47] found that a team leader with a participatory style of leadership - giving the team considerable freedom to explore, discuss, make their own decisions, decide what problems to solve and what tasks to undertake - was associated with higher project performance. The key was that the team leader worked as an enabler by ceding responsibility to the team, i.e. empowering them. Team leaders setting realistic expectations and efficiently communicating the expectations to the organization team as well as sharing information and knowledge broadly and efficiently can contribute to the success of a cross-functional team [46].

Leaders of the cross-functional team do not uncommonly take the role of a communicator, including communicating project focus, changes, developments and individual responsibilities with the team and the rest of the organization [46]. Successful team leaders are effective in the communication with senior management and the rest of the organization by lobbying for resources and protecting the team from outside interference [3]. Successful team leaders are efficient in juggling expectations, communication and resource allocation with the team and the rest of the organization, including senior management and translating the project conditions, i.e. stage-setting elements, into tangible results.

Senior management support and involvement during the project have an impact on the

performance of the cross-functional team [63, 68]. Senior management can support the team in numerous ways, including providing resources, freeing up time for team members, demonstrating commitment, giving authority and encouraging the team [8, 30, 31, 68]. Lack of senior management support, unrealistic expectations, and short term orientation can be reasons for delays in the project [26]. Senior management can increase the likelihood of project success by supporting the team, and a lack of support can contribute to failure[31].

Champions are characterized as taking an extraordinary interest and supporting a project,

product development initiative or a certain aspect or process of one of the recently mentioned. The role of a champion is ambiguous and can vary a lot. For instance, a champion can advocate for a project to management and make sure the project gets the resources and attention required or stimulate awareness for a project. There is little research looking at the champion’s effect on project performance, but the general view on the champions is that they contribute to the

success of projects/initiatives [46]. In a study by Markham and Griffin [43], they argue that the role of a champion in project outcomes is more indirect than direct. In the light of this, champions can be seen as enablers for the project or initiative.

To summarize, Team Leaders, Senior Management and Champions constitute what McDonough call enablers [46]. Their involvement and support in the project and for the cross-functional team vary, and the relationship can be complex. Traditionally, the enablers impact on the project success is indirect, but can also be direct on rare occasions. Enabler’s impact on the project is particularly significant in the process of establishing the stage-setting elements.

2.3.3 Team Behavior

Team behavior is the way individuals and the team as a whole behave, which affects the performance of the project. The team behavior is heavily influenced by the enablers and the stage-setting elements. McDonough divided Team Behaviors into four key variables, namely

Cooperation, Commitment, Ownership, and Respect.

”Cooperation, i.e. working together to accomplish the work of the team, has been variously defined as collaboration, teamwork, interaction, communication, and integration” [46]. Open, frequent and accurate communication in a team increases the volume and diversity of shared information, with fewer misunderstandings and increased job cohesion [35]. Clear goals facilitate cooperation by focusing individual’s efforts to specific, tangible and common goals [54]. Additionally, specific goals can be used to measure project performance and help promote integration across functions [8]. As previously mentioned, culture heavily influences how communication, interaction and collaboration are made in the company. Hence culture plays an integral part in the cooperation in a cross-functional team. Project leaders with efficient interpersonal skills can be important to facilitate integration between functions [46]. For example, the project leader may facilitate cross-functional discussions in and through meetings by easing discussions and inviting all functions to participate.

Commitment is defined by Weiner [65] as ”the totality of internalized normative pressures to

act in a way that meets organizational interests”. Commitment can be viewed as the sense of duty an individual or a team feels towards a project or an organization. Commitment can also be considered as the willingness to work hard to achieve the goals of a project or organization. Project teams that have a good mix of skills and expertise, in other words, people from different functions in the company that complement each other, may enhance each member’s confidence in fellow team members. Increased confidence and trust in fellow members may increase

the team members willingness to commit to the project and to put in the work to make it successful [8]. Project teams with committed team members throughout the project have a higher probability of achieving the project objectives [56]. This shows the importance of carefully assembling a team with the right mix of expertise and skills. Thus, the stage setting element Human resources is an essential precursor for a committed project team.

Ownership refers to the team members’ feeling of wanting to make a difference. It goes

beyond duty, i.e. commitment, members are tying an identity to the outcome of the project. Hence they are putting in extra work to ensure the project’s success [46]. The stage setting elements empowerment , establishing climate, and setting goals affects the team members sense of ownership. Out of these three, setting specific and clear goals early on is most likely to foster ownership. To do this, it is important to involve the team members early so the team together can translate the goals into tangible statements and action points for the team to execute upon [8]. In this process, the leader plays an important role in actively fostering involvement from the team members.

Respect between the members of the team may lead to open communication and feelings of

trust. When team members trust each others’ judgement and have an honest interaction with each other, it is an expression of respect for each other [46].

Summary (Cross-functional teams)

Looking at the factors mentioned, it is evident that the factors for success are dependent on each other in numerous ways. For example, the stage-setting elements are heavily reliant on

senior management’s support to get the resources and attention needed to carry through the

project successfully. Also, the commitment, ownership and respect in the team depends on the composition of the team i.e. human resources.

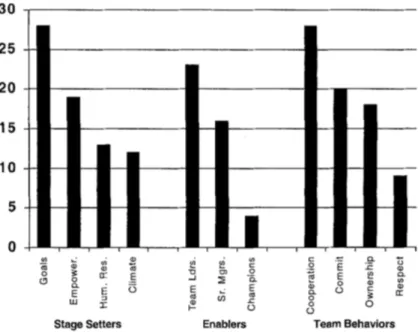

Multiple factors are contributing to the cross-functional team’s project performance. The relative importance of different factors for a specific project depends on the characteristics of the project, including, for example, technological complexity, newness involved in the development process, the newness to the market, and importance of speed to market. Furthermore, it depends on other contextual factors, including the size of the organization and industry. In a quantitative study by McDonough [46] (see figure2.3.1), conducted on members of the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA) with 112 respondents, it was investigated which factor was most associated with project success in a cross-functional team project. The study concluded that Goals was the most important stage setting variable,

Figure 2.3.1: Success elements by category.

Team Leadership was the most important enabler variable and Cooperation was the most

important team behavior variable. In figure 2.3.1, numbers on the bar chart equal percent of respondents mentioning an item (n=112).

2.4 Our theoretical lens

For the purpose of this research we draw on McDonough’s three categories, i.e. Stage Setting

Elements, Enablers and Team Behaviour, to elaborate on what factors may contribute to the

success or failure of a project or product development initiative[46]. Stage Setting Elements builds the foundation and sets the purpose on which the work for the cross-functional team takes place [46]. Factors in Stage Setting Elements include, goals, Empowerment, Climate and Human resources, of which all are set before the project/product development initiative is initiated. Responsible for setting the stage for the project, i.e. stage setting elements, are most often people in management positions. Management identifies a need/problem/challenge of a complex nature, which requires people from different departments in the company with a diverse set of skills to work together. Management has the authority to construct a cross-functional team and provide them with the necessary expectations, instructions, resources and authority to carry out the project/product development initiative. In this sense, management carries out Senior Management Support, which is an important factor for success and belongs to McDonough’s Enablers category. Additional factors in Enablers include, Team Leadership and Champions. Enablers are individuals that have a significant impact on the outcome of the

project by supporting them, giving authority, allocating resources and championing the project, most often by indirect involvement. The third category,Team Behavior refers to the individual’s sense of commitment, ownership and respect to the team and the project. Co-operation and communication in the team are also important variables in the category team behavior and impacts the performance of the cross-functional team.

Stage Setting Elements, Enablers and Team Behaviour will be analyzed by their given

characteristics as well as how they are affected by organizational communication,

organizational culture, and current business environment. By examining the effects of these

three aspects in tandem with cross-functional teams, organizationally specific factors will be taken into account to draw specific and grounded conclusions. This will allow for a thorough analysis of potential success factors for cross-functional teams in this context.

Research Design / Methodology

In this chapter, we motivate and explain the methodology used to acquire relevant empirical data for our study. The chapter is divided into six sections. The first section outlines our research process. In the second section, we put forward our research approach. In the third section, we elaborate on our research design. In the fourth section, we describe how we collected relevant data which forms the basis to our analysis. In the fifth section, we discuss the quality of our research. In the sixth section we explain how we conducted our analysis.

3.1 Research Process

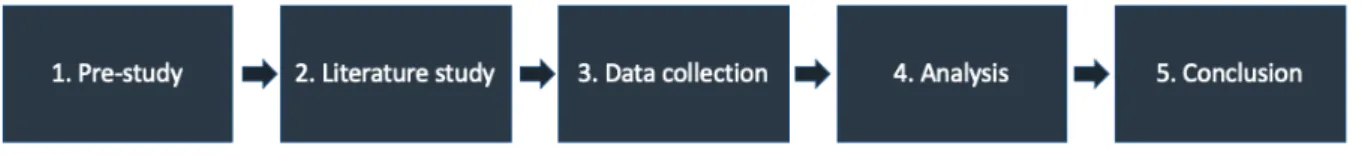

The research process is outlined in figure 3.1.1

Figure 3.1.1: Sequential order of the research process

Pre-study - For us to understand the company and the investigated phenomena, we conducted

a pre-study at the company. In order to understand the company, we spent weeks at the office talking to people and attending internal and external meetings. As the company has an open office space and most of the people working at the case company were very prone to talk two master thesis students it was easy to engage in conversation with people at the office. Furthermore, we conducted interviews with members of senior management, middle managers and other employees with the aim of understanding their individual and their department’s role in the company. All this gave us great insights into the company situation, the people working

there, and what challenges they face.

Literature study - The findings from the pre-study and the study’s focus on cross-functional

teams defined an area of relevant literature. Naturally, a substantial part of the theoretical framework was designated to literature concerning cross-functional teams. Additionally, the input from the pre-study guided us to read up on literature pertaining organizational communication, communication networks, organizational culture and business stages, aspects that in different ways influences how the cross-functional team operates in the case company. Furthermore, additional research literature was reviewed on aspects that we found interesting for the studied phenomena as the study progressed.

Data collection - General observations of the company was conducted to gain context on the

company and the environment in which the cross-functional team operates. We followed the cross-functional team’s work by attending their daily stand-ups and doing observations during the meetings. Additionally, we conducted interviews with the core members of the cross-functional team as well as key enablers for the project. The literature study guided the interview questions. Eventually, the empirical insights also somewhat steered literature study as we found new interesting aspects to study. This allowed us to be flexible and adjust our literature study to the empirical findings and to put it in the right context.

Analysis - The empirical findings were analyzed using the categories outlined in Empirical

Findings. We also investigated how the different categories and factors were interlinked.

Furthermore, we analyzed our empirical findings together with our Theoretical Framework presented in chapter 2. We strategically divided our analyses into two major themes based on our two Research Questions. For the first theme, we analyzed how different factors affected the performance of the cross-functional team. For the second theme, we investigated how the contextual environment that the cross-functional team operated in affected the team and the project.

Conclusion - In this chapter, the research questions were answered based on the analysis in

Chapter 5. Furthermore, we present what theoretical and managerial implications this study

has. Lastly, we give recommendations on next steps for future research.

3.2 Research approach

The purpose of this study is to advance the understanding of what factors contribute to the success of a product development project using a cross-functional team and what challenges

come with it. Our aim was to gain a deep understanding of the organizational process and structures as well as the personal thoughts and experiences of the people involved, leading to a holistic understanding of the investigated phenomenon. In this case, an in-depth qualitative study is appropriate to render a holistic and deep understanding [6]. A quantitative study, for instance, by using surveys, would not capture the deep and detailed understanding that was desired. Therefore, a quantitative approach was disregarded in favour of a qualitative approach. As we are studying one cross-functional team at a target company for a limited period of time, we have chosen an inductive approach for our study. An inductive approach is appropriate when we are starting to look for patterns in observations, and then theories are proposed at the end of the research process [22].

3.3 Research Design

We conducted an in-depth qualitative case study at a single company. A case study is a means of investigating an ongoing phenomenon in the real-life context it appears in [67]. Furthermore, a case study is an appropriate research method when investigating the underlying motivations for why and how a phenomenon is the way it is [6]. We chose to go with a single case-study of a selected company over a multiple case-study approach for two main reasons. Firstly, although multiple case studies would render a more generalized understanding of the phenomena, our scope of the study points us to gain a deep and detailed understanding of the studied phenomena, forcing us to spend a substantial amount of time at a single company. Secondly, the contextual environment of the company and the cross-functional team were unique, and it was hard to find similar cases that resembled the conditions at the case company.

Our qualitative case study consisted of interviews with people at the company relevant for the cross-functional team, observations of the cross-functional team, and general observations of the company and the cross-functional team. Using interviews and observations is a standard methodology to describe, contextualize, and gain in-depth insights into a specific phenomenon. To gain in-depth knowledge, of what factors contribute to the success of a product development project using a cross-functional team and what challenges come with it, we had to study the organization closely and be present at the company. For us to be present at the company, attend meetings, and interview people we had to sign an NDA (Non-Disclosure agreement), where we guaranteed that some potentially sensitive aspects of the organizations were left out in this study. The aspects relevant to this study were not considered sensitive by the company. Hence, the study was not in any way affected, obstructed or back-tied by the signed NDA.

3.3.1 Company Background

The target company is a rapidly growing high-tech scale-up in the gaming industry, offering digital entertainment products directly to the end customer. The company had approximately 150 employees at the start of the study, growing from 40 employees from the year before. For the entire duration of the study, we were present at the case company which eased the collection of data and access to interviewees. At the time of the study, the company was rapidly growing and evolving from a start-up with innovative new offerings and untapped market potential to a fast-growing scale-up with attractive offerings and rapidly growing customer volumes.

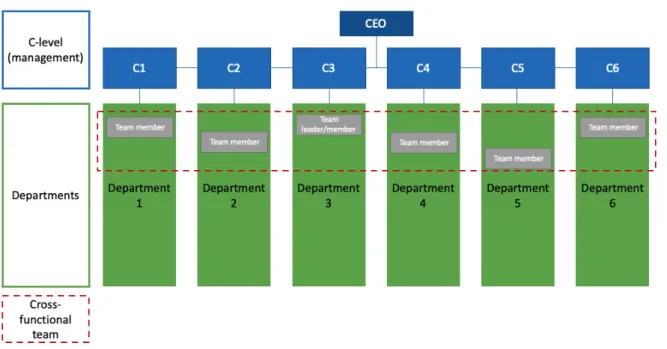

The study was conducted on a cross-functional team which was assembled for a project by management to focus on an important product development initiative. The team members chosen for this project came from different departments in the company, with a diverse set of skills and expertise necessary to drive this project. (See 3.3.1)

Figure 3.3.1: Mock figure - illustrating the company structure and the members of the cross-functional team

3.3.2 Rationale for selected company

During the time of the study, the target company was continuously tweaking and improving the offerings to the customer to increase volume, customer satisfaction, retention and conversion. This made the company in question an ideal prospect for analyzing the potential of implementing a cross-functional team. The fast growth pace, coupled with the high adaptability

offered a unique platform for this study because routines had not been firmly established, and a rapid influx of employees lead to a very diverse group of employees.

A cross-functional team with representatives from different departments was assembled for a critical product development project of the company’s core product (at the time). The study was focused on this cross-functional team, and we followed this project from the initializing start-up meeting to the end of the project. The length of the project amounted to more than ten weeks. Having the ability to be present from the very inception of the cross-functional team was very insightful. We closely monitored the cross-functional team for ten weeks. Following the team from inception and over ten weeks allowed for broader aspects, stage setting elements, and results to be observed.

3.4 Data collection

Multiple different methods of data collection were conducted, including interviews with core-members and enablers, observations of the team’s meetings, and general observations.

Three weeks after the initiation of the cross-functional team, a work-from-home order was issued by management due to the rapidly spreading COVID-19 virus. This drastically changed the data collection methods and will be further explained with regards to the different data collection methods.

3.4.1 Daily Syncs

One of the main sources of data collection was observations of the cross-functional team’s daily syncs that occurred at 10:00 AM every morning from Tuesday to Friday. These syncs were a means of gathering all core cross-functional team members in one place and allowed them to share their current progress as well as gain input from other departments. These daily syncs started immediately after the initial start-up meeting, and we attended all meetings during teen weeks.

By silently observing the cross-functional team members, and other colleagues attending the meeting, we were able to see them work, communicate and co-operate in a true setting. When we attended and observed the meetings we wanted to be ”a fly on the wall”, basically just being there but not engaging with the team members or influencing the meetings. After the Covid-19 pandemic forced the company to issue the work-from-home order, we attended and observed the meetings in Google Hangouts. We decided to turn our camera and microphone off, not to influence the meeting in any way - practically our presence in the online meetings was unnoticed.

Data gathered from the daily syncs consisted of observations regarding attendees, team dynamics, communication, co-operations and attitudes.

Online format (COVID-19)

After approximately three weeks of daily syncs, a work-from-home order was issued to the company, and within one day, these daily syncs that were commonly held in the office began being held in Google Hangouts. This added a whole other level to our analysis, as we were now able to not only record behavior and communication but also record the changes that occurred when the format was changed from face-to-face to online. Aspects such as ”using camera” and ”muted microphone” were now recorded in these journals as well. This data, along with the data already recorded, gave us a platform to analyze the effects of online meetings and interactions on cross-functional teams and daily work in general.

3.4.2 General observations

We practised passive and observational data collection by spending time at the office and recorded general observations and findings. We also had access to the company’s general communication platform, Slack. We were members of the company’s general Slack channels as well as channels connected to specific teams and initiatives, including the cross-functional

team. For this, we used journals to record and date all observations made at the company. Data collected from the general observations consisted of communications, co-operations, culture and office layout.

3.4.3 Interviews

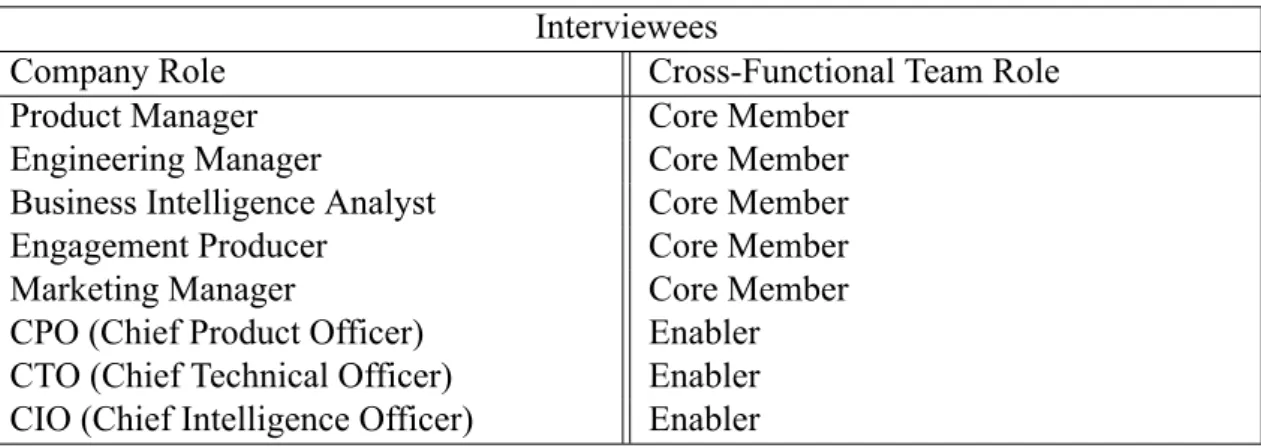

One source of data collection was interviews with members of the cross-functional conversion team as well as enablers of the team. Table 3.4.1 lists the interviewees.

Interviewees

Company Role Cross-Functional Team Role Product Manager Core Member

Engineering Manager Core Member Business Intelligence Analyst Core Member Engagement Producer Core Member Marketing Manager Core Member CPO (Chief Product Officer) Enabler CTO (Chief Technical Officer) Enabler CIO (Chief Intelligence Officer) Enabler

Table 3.4.1: Table of Interviewees

The interviews lasted from 35 minutes to 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. The interviews were semi-structured, and a range of predefined and pre-coded questions were prepared before each interview. These served to steer the conversations in certain directions, but individual inputs and points-of-interest were encouraged.

By asking direct questions concerning sensitive subjects, e.g. ”Do you respect the other team members?”, the interviewee might urge to say ”Yes, I fully respect all the team members”, as the interviewee recognize this is the preferred answer from management and other colleagues but not necessarily the truth. By asking open-ended questions, e.g. ”How are you communicating in the team?”, ”How close have you worked with the team members before?” and ”Do you co-operate well with person x?”, we can read more into the interviewee’s answer. Building upon this, we decided not to send our interview questions to the interview subjects beforehand, we wanted spontaneous and honest answers. By providing the interview subjects with the questions before the interview, they are given the time to potentially construct the preferred answers to the questions, which we wanted to avoid.

Upon reflection, the interviews were all very informative and insight-heavy. This was mainly due to the semi-structured format that allowed the interviewees to rationalize what they found important. That being said, some interviewees were more prone to share than others, and we,

therefore, asked follow-up questions in order to encourage deeper reasoning. With interviewees who were less inclined to elaborate, this proved to be successful as they progressively began to elaborate on their answers.

Online Interviews (COVID-19)

Due to the work-from-home order being issued before the interviews started, all interviews were conducted via Google Hangouts. This posed no further difficulties, although using cameras was encouraged in order to get a more engaging conversation.

The interview template was adapted to include questions regarding the online format. This was to give us insights on the effects of the online format as well as personal opinions on the online meetings and interactions.

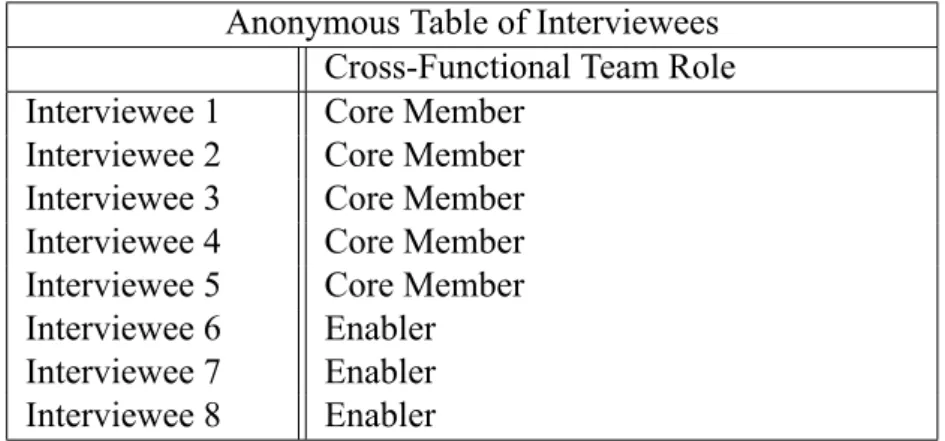

3.4.4 Interview Referencing

Table 3.4.2 shows our anonymous referencing table and was used to reference interviews in the Empirical Findings section and the Analysis section of the paper. The table was shuffled.

Anonymous Table of Interviewees Cross-Functional Team Role Interviewee 1 Core Member

Interviewee 2 Core Member Interviewee 3 Core Member Interviewee 4 Core Member Interviewee 5 Core Member Interviewee 6 Enabler Interviewee 7 Enabler Interviewee 8 Enabler

Table 3.4.2: Table of Interviewees referencing

3.5 Research Quality

Validity and reliability”Validity and reliability are key aspects of all research. Meticulous attention to these two aspects can make the difference between good and poor research and can help to assure that fellow scientists accept findings as credible and trustworthy. This is particularly vital in qualitative work” [9].

In the research process, there are several pitfalls which weaken the validity, including shortcomings in the data collection process, faulty procedures, and inaccurate measurements [12]. Gibbert et al. [21] have proposed three important criteria to enhance the validity of the research. Namely, the researchers should formulate a clear research framework, use pattern matching, and use theory triangulation to verify findings.

To enhance the validity of our research, we have thoroughly outlined our research methodology and why our chosen methodology is particularly appropriate for the studied phenomena and our research question. Our research is a single qualitative case-study with data collection, mainly including observations and interviews.

Our thorough pre-study equipped us with important knowledge about the company and the context in which the cross-functional team operates. This made it easy for us to identify key people for the cross-functional team, both the core-members of the team, but also non-core-members that was important for the project, i.e. the enablers. Having interviews with the most relevant people for the project enhances the quality of the empirical data collected from the interviews. Furthermore, we strived to gain as many insights as possible from each interview by asking follow-up questions. Also, to ensure that our understanding was aligned with their indented answer, we asked: ”We understood your answer like this - did we get it right”? Nevertheless, there is a risk that we misunderstood the interviewee, interpreted their answer in the wrong way, or read to much into their answer and made the wrong conclusions.

The semi-structured format of the interviews encouraged the interviewee to formulate their own answer and focus on aspects they chose, with the benefit of providing us with rich and nuanced answers but with the risk on missing out certain aspects interesting aspects. The semi-structured format relies on our, the researchers’, ability to use intuition and steer the interviewee enough to talk about the subject the researchers are interested in, a risk being the researchers’ ability to steer the conversation.

Theory triangulation was performed using all the different types of data collected, including the observations, the interviews with different stack-holders in the company, and the reviewed literature.

Reliability refers to the absence of error, meaning that if the study was to be conducted again by another researcher, would that researcher get the insights. The aim is to minimize the errors in the research process. To achieve great reliability, the research process should be highly transparent and replicable [21].

This study is a qualitative case study with data collection and analysis subject to the researchers’ ability to capture relevant, empirical data and analyze it without being subjective. Studying a particular phenomenon in a specific organization generally generates low reliability. The setting and the context in which this particular cross-functional team operates within is highly unique for several reasons: The company is a pioneer in developing this type of product, the company is young and growing rapidly, the technological capabilities changes drastically for this type of business, and the cross-functional team is the company’s first try using this work method. By default, the reliability of this study is low, but there are a few measures used to increase the reliability of the study. By interviewing all the core-members of the cross-functional team, that were part of the core-team for the entirety of the project, we increased the reliability of the study. Furthermore, we attended almost all of the cross-functional team’s daily stand-ups during the studied period, with the aim to capture the aggregated sum of findings from all meetings. Additionally, we thoroughly outlined our research process.

Generilizability

Generilizability refers to the study’s ability to account for general phenomena not only in the

setting in which it is studied but also in other settings [21]. A single case-study can never be entirely valid for other cases, even for similar cases. Nevertheless, some of the insights can be valid for other cases.

The conclusions drawn from this case-study are not fully generalize. Nevertheless, there are some interesting insights with regards to the cross-functional team that can apply to organizations sharing the same characteristics as the case company and also organizations that are not very similar. However, other researchers or organizations should be careful when using the insights from this study, as there are features making it very unique.

3.6 Method of analysis

One of the primary strengths of this research project was the multiple data sources because they allowed for the cross-functional team to be studied from multiple different perspectives. The interviews allowed us to study the team from the inside, from the perspective of the team members themselves. The daily sync observations allowed us to study the team objectively from the outside. The general observations allowed us to study the project externally based on the surrounding factors, providing context to the studied phenomena. These data sources could then be combined and compared so that less biased and more grounded conclusions could be