Expert perceptions on renewable

energy implementation in ASEAN

An angle from cross-sector collaborations

Oana Maries & Nathalie Zauels

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2018

ABSTR AC T

The world today is built on energy. Every process, whether industrial or civil, from the moment one awakes in the morning all throughout the day and into the late night, is fuelled by energy. There is an energy consumption going on twentyfour hours, every day of the year (IEA, 2017). The traditional energy mix (coal, gas, oil) has been used up to now with disrupting effects on our planet. In order to stay in the sustainable development concept, the demand for energy will be optimally met with renewable energies (RE), so to also keep the global temperatures under 2°C or even 1.5°C, if ambitious measures are used (IPCC, 2011).

The focus of this study is on the Association of South East Nations (ASEAN), because it has an unexploited potential to increase the usage of RE, due the fact that the region has over 140 million in population without access the electricity (Shi, 2016, IEA, 2017). The region is also still developing its energy infrastructure and decides on energy road maps for the next couple of years (Zamora, n.d., Brahim, 2014, Alison Riddell, Steve Ronson, Glenn Counts, n.d., Renner et al., 2018). Thus, this is the right time to research why ASEAN has not yet implemented more RE into its nations.

The paper will explore the experts perceptions on the RE implementations in ASEAN as well as how does the government regulation and policy structures involve in the renewable energy implementation. To provide a better understanding of the impacts in the implementation phase of RE in ASEAN, the PESTEL framework helps to analyse the area on a macro level from six different perspectives. This framework will also help to identify and give suggestions to overcome several obstacles that have emerged in the implementation of RE in ASEAN.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 2

GLOSSARY ... 4

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1ENERGY POWERING THE WORLD ... 1

1.2DEFINING RENEWABLE ENERGY ... 3

1.3PROBLEM FORMULATION ... 4

1.4PURPOSE &RESEARCH QUESTIONS... 5

CHAPTER 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK... 7

2.1THE PROBLEM TREE ... 7

2.1.1 Causes ... 8

2.1.2 Effects ... 9

2.2COLLABORATIONS BETWEEN GOVERNMENTS AND ORGANISATIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ... 9

2.2.1 Institutional perspective on intersectoral collaborations ... 11

2.2.2 Collaborations for policy making ... 11

2.3PESTEL FRAMEWORK... 13

2.3.1 Development of a conceptual frame as an analytical tool to identify the drivers and barriers based on the PESTEL framework ... 14

CHAPTER 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 16

3.1.RESEARCH DESIGN ... 16

3.2.KEY INFORMANT (SELECTION OF INTERVIEWS) ... 17

3.3.DATA ANALYSIS /CONTENT ANALYSIS ... 18

3.4.ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 20

CHAPTER 4. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS... 21

4.1GOVERNMENTAL STRATEGIES & OBSTACLES FOR INVESTMENTS:POLITICAL AND LEGAL ANALYSIS ... 21

4.1.1 Governmental strategies ... 21

4.1.2 Obstacles to foreign investment ... 23

4.2DEVELOPMENT OF RE REGULATION:ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS ... 25

4.3INFRASTRUCTURE, PRICE OF ENERGY AND FINANCING:ECONOMICAL ANALYSIS... 26

4.3.1 Price of energy ... 26

4.3.2 Infrastructure ... 27

4.3.3 Financing ... 27

4.4THE OTHER CRISIS:SOCIAL &TECHNOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ... 29

4.4.1. Know how ... 29

4.4.2. Quality of life ... 30

CHAPTER 5. DISCUSSION ... 32

CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ... 34

6.1 Contribution to research ... 34

6.2 Recommendations & Implication for further research ... 34

6.3 Limitations ... 35

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 36

GLOSSARY

AEC – ASEAN Economic Community AFTA – ASEAN Free Trade Area

APAEC - ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation ASEAN - Association of South East Asian Nations APS - Advancing policy scenario

BAU - Business as usual

CDM – Clean Development Mechanism (from Kyoto Protocol regarding new models of governance) COP 21 – The United Nations Climate Conference

DOE – Department of Energy

ERC – Energy Regulatory Commission (The Philippines) FDI – Direct Foreign Investment

FIT – Feed-in-tariff

GIZ - German Government Cooperation Agency (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH)

GHG – Green House Gases

IEA – International Energy Agency

IRENA – International Renewable Energy National Agency IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (from UN)

PESTEL – Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental legal framework PPA – Power Purchase Agreement

PPP - Public Private Partnerships R&D – Research & Development RE - Renewable Energy

Solar CSP – Concentrated Solar Power Solar PV – Solar Photovoltaic System TTP – Trans-Pacific Partnership

1.1 ENERGY POWERING THE WORLD

The world today is built on energy. Every process, whether industrial or civil, from the moment one awakes in the morning all throughout the day and into the late night is fuelled by energy. There is an energy consumption going on 24h, every day of the year (International Energy Agency (IEA), 2017). One starts to realise the amount of energy used, once it is not available anymore or when the monthly bill is composed of too many numbers. The energy used to power all the daily needed processes is conventionally based on oil, coal and natural gas. These sources have been highly disputed drivers in the economic progress. In the capitalist era, they were seen as a reason for economic growth, while today the situation can be seen differently (Vinci et al., 2017, International Energy Agency, 2017).

For the last decade, talks around how these sources are damaging the environment irrecuperable, have been surfacing and have pushed researchers into creating alternatives, renewable alternatives(IEA, 2017). Renewable technologies for creating energy, have been created as clean energy sources that can provide the same amount of energy needed, while also minimizing environmental impacts, while also being an infinite source when used correctly (IEA, 2017). RE (renewable energy) is a much-discussed opportunity in the fight against CO2 emissions and the struggle to reduce global warming (IRENA & CPI, 2018).

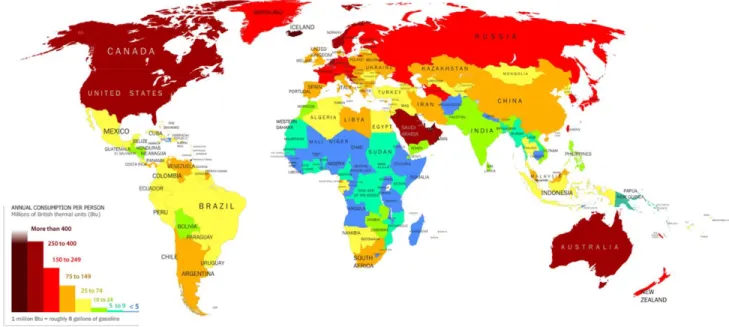

Figure 1 – Energy Consumption per person by country, 2010 (“MAP: How much energy is the world using?,”2016.)

Predictions made by The World Bank (“Renewable energy consumption (% of total final energy consumption) | Data,” 2016) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) forecast an increase in the demand of energy needed in the years to come (figure 1). This is based mostly on the fact that ASEAN nations are increasing their energy demand as they go through a phase of eradicating poverty. Demand for energy and its associated services is increasing due to industrialisation, that arises from the economic development needed to eradicate poverty that brings with it the need to also improve human welfare (IPCC, 2011, page 7). With the increase in energy demand comes also the increase of green house gas GHG emissions, if the energy comes from an unrenewable source.

The increase in demand would bring the worlds emissions to alarming numbers in a very short time frame, if the demand forecasted is met with the traditional means of energy creation: coal, gas and oil.

Also, a report by the World Energy Council, draws attention to the main issues that can cause future conflicts when it comes to the energy production sector. This research paper mentions as main macroeconomic risks, the economic growth, as also mentioned earlier in this chapter, the energy-water-food nexus1 (due to changing weather patterns with direct effect on energy production and supply), energy

access and availability as well as cyber threats 2 (“World Energy Issues Monitor,” 2017).

The energy trio mix (coal, oil and gas) has always been used as energy creators, while using renewable energy was not considered an alternative. Wind and solar energy is intermittent ( intermittent character given by the hours of sun shine per day or the needed speed of wind for RE) and gives an unreliable character, thus making the usage of oil and coal the safe way out. However, they too are unreliable if one thinks of the drilling process and predictions of volumes of the non-renewable sources (Danish Energy Agency, 2016). One wrong step or calculation could affect the energy creation thus making it unreliable as well. The same problem arises with coal and to its extraction process (International Energy Agency, 2016, Birol, 2017).

Also, besides the problems brought to the environment by the classic energy development methods, today there is also a clear alarm signal being pulled by climate change researchers with regards to the social sustainability (Birol, 2017). If one looks at the extraction process of coal in a more inclusive angle, from a social sustainable development, coal mining is also seen as a silent killer, with the workers developing pneumoconiosis, more widely known as black lung (Wilson, 2010).In order to stay in the sustainable development concept, the demand will be optimally met with renewable energies, so to also keep the global temperatures under 2°C or even 1.5°C if ambitious measures are used (IPCC, 2011).

The focus of this study is on the Association of South East Nations (ASEAN), because it has an unexploited potential to increase the usage of RE, due the fact that the region has over 140 million in population without access the electricity (Shi, 2016,IEA, 2017). The region is also still developing its energy infrastructure and decides on energy road maps for the next couple of years (Zamora, 2015, Brahim, 2014, Alison Riddell, Steve Ronson, Glenn Counts, n.d., Renner et al., 2018). Thus, this is the right time to research why ASEAN has not yet implemented more RE into its nations. ASEAN is composed of ten member states and was founded in 1967, with the first five members: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand (“Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) | Treaties & Regimes | NTI,”).

The focus within ASEAN is on three specific countries out of the ten countries composing it, due to their current progress in implementing RE and their connections to foreign associations like GIZ (German Government Cooperation Agency (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH)). First, Vietnam was chosen, because they are the wind energy experts in ASEAN and are developing education focused on RE (“VIETNAM Energieeffizienz und Energiemanagement in Vietnam www.german-energy-solutions.de,”).The second country with a special focus in this research, the Philippines was chosen, since they expressed their desire of becoming a role model in the implementation of RE. Also, the Philippines, is the only ASEAN nation that has developed a direct collaboration agency (National board of Renewable Energy), in which the private sector has direct communication to the legal side of new policies regarding RE (Brahim, 2014, “National Renewable Energy Program | DOE |

1 “The water, energy and food (WEF) nexus means that the three sectors — water security, energy security

and food security — are inextricably linked and that actions in one area more often than not have impacts in one or both of the others.” (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, n.d.)

Department of Energy Portal,” 2018). Lastly, Indonesia has been chosen because it has the largest energy consumption in whole ASEAN and thus, from a sustainable development point of view, can have the greatest positive impact when implementing more RE (International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 2017).

1.2 DEFINING RENEWAB LE ENERGY

This thesis focuses most on RE, therefore a thorough explanation of the terms that form RE should be made. RE as a concept is composed of six different types of renewable energies, all explained in this subchapter.

Renewable energy: according to the IPCC, RE are “a heterogeneous class of technologies that can supply

electricity, as well as produce fuels that are able to satisfy multiple energy service needs. Some RE technologies can be deployed at the point of use (decentralized) in rural and urban environments, whereas others are primarily deployed within large (centralized) energy networks. Though a growing number of RE technologies are technically mature and are being deployed at significant scale, others are in an earlier phase of technical maturity and commercial deployment or fill specialized niche markets. The energy output of RE technologies can be variable and—to some degree—unpredictable over differing time scales (from minutes to years), variable but predictable, constant, or controllable.” (I.P.C.C., 2011)

Wind power: “Wind energy harnesses the kinetic energy of moving air. The primary application of

relevance to climate change mitigation is to produce electricity from large wind turbines located on land (onshore) or in sea- or freshwater (offshore). Onshore wind energy technologies are already being manufactured and deployed on a large scale. Offshore wind energy technologies have greater potential for continued technical advancement. Wind electricity is both variable and, to some degree, unpredictable, but experience and detailed studies from many regions have shown that the integration of wind energy generally poses no insurmountable technical barriers.” (I.P.C.C., 2011)

Bioenergy: can be produced from a variety of biomass feedstocks, including forest, agricultural and

livestock residues; short-rotation forest plantations; energy crops; the organic component of municipal solid waste; and other organic waste streams. Through a variety of processes, these feedstocks can be directly used to produce electricity or heat, or can be used to create gaseous, liquid, or solid fuels (IPCC, 2011).

Direct solar energy technologies: harness the energy of solar irradiance to produce electricity using

photovoltaics (PV) and concentrating solar power (CSP), to produce thermal energy (heating or cooling, either through passive or active means), to meet direct lighting needs and, potentially, to produce fuels that might be used for transport and other purposes (IPCC, 2011).

Geothermal energy: utilizes the accessible thermal energy from the Earth’s interior. Heat is extracted from

geothermal reservoirs using wells or other means. Reservoirs that are naturally sufficiently hot and permeable are called hydrothermal reservoirs, whereas reservoirs that are sufficiently hot but that are improved with hydraulic stimulation are called enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). Once at the surface, fluids of various temperatures can be used to generate electricity (IPCC, 2011).

Hydropower: harnesses the energy of water moving from higher to lower elevations, primarily to generate

electricity. Hydropower projects encompass dam projects with reservoirs, run-of-river and in-stream projects and cover a continuum in project scale. This variety gives hydropower the ability to meet large centralized urban needs as well as decentralized rural needs (IPCC, 2011).

Ocean energy: derives from the potential, kinetic, thermal and chemical energy of seawater, which can be

transformed to provide electricity, thermal energy, or potable water. A wide range of technologies are possible, such as barrages for tidal range, submarine turbines for tidal and ocean currents, heat exchangers

for ocean thermal energy conversion, and a variety of devices to harness the energy of waves and salinity gradients (IPCC, 2011).

RE is the sector that can help in the decarbonising process ASEAN is trying to pursue. The region presents potential in all forms of RE and therefore is a good ground for research when it comes to studying the implementation of sustainable development through RE (Shi, 2016) .

1.3 PROBLEM FORMULATION

In the last decades ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) went through a rapid growth in economics and population, which led to an increase in industrialization and urbanization growth. Due to the high intensity of growth compared to the amount of time, the development was not focused on sustainability, but rather on efficiency. Thus, also the energy production focused firstly on how to produce energy efficient and effective (ACE, 2015; IEA, 2017; Khuong, 2017; Shi, 2016). Moreover, except of Brunei, which is high in production of gas and oil, all other ASEAN countries are facing an energy deficit to their demand (Khuong, 2017).

The GWEC report shows that there is a slow development of renewable energy alternatives. The main concern is, that these developments are not developing at a speed directly proportional with the demand increase in energy. In order for that demand not to be met with non-renewable energy development, there is a need for speeding up the process of developing renewable electricity alternatives. (Global Wind Energy Council, 2015)

The same report shows a significant increase in the Asian region with China taking the lead when it comes to RE, followed by India and Japan. However, there is a stagnation in the MW3 installed by country members of the ASEAN region4. The report only contains data on Thailand and the Philippines and both have no progress from 2014 onward to 2015 (223MW for Thailand, respectively 216 for the Philippines) (Global Wind Energy Council, 2015). This poses a set of questions since there is an evident market for wind power that is not being exploited to the fullest. What could hinder the development of RE in this region? The contemporary research on RE has mainly focused on the Western part of Europe or North America. Thus, the know-how process is originated in the westernised countries. The Global Wind Report Annual Market Update from 2015 shows that Europe alone had 147.771 MW newly installed, and increase of 13.520 from 2014 installed MW (Global Wind Energy Council, 2015).

There is a potential for the energy demand in ASEAN to be met with RE. The drawback is that the know-how is mainly developed in Europe and the US and the ASEAN region is missing the specialized work force to lead the implementation process. There is also a weak collaboration between organisations wishing to develop RE projects and the government since the projects for RE are not done at a speed directly proportional with the speed of the growing need for energy.

3

“

A megawatt is a unit for measuring power that is equivalent to one million watts. One megawatt is equivalent to the energy produced by 10 automobile engines.

A megawatt hour (Mwh) is equal to 1,000 Kilowatt hours (Kwh). It is equal to 1,000 kilowatts of electricity used continuously for one hour. It is about equivalent to the amount of electricity used by about 330 homes during one hour”. (Clean Energy Authority, n.d.)

4 “ASEAN is composed of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam and was developed in 1967 to accelerate the economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region through joint endeavors” (“ASEAN | One Vision One Identity One Community”).

1.4 PURPOSE & RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In order to discover how RE development could evolve in ASEAN, the purpose of this study is to research the expert perceptions on RE implementation in ASEAN on different aspects ( legislation, financial, environmental regulations, cross-sectoral collaboration). Mainly, this focuses on the collaboration between organizations in private sector and governments of the focused countries. This study will look into the efforts made for implementing RE. This main research question of this study is:

What are the expert perceptions on renewable energy implementation and

development concerning legislation, financial aspects, environmental regulations

and cross-sectoral collaboration of governmental institutions?

By expert perception, the study refers to the angle of the specialists from within the industry, such as wind power engineers, energy economists, energy professors, advisors on RE, global energy investment specialists. The study will focus on ASEAN member countries experts, with a focus also on Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. The reason for narrowing down the focus is based on the potential that these three countries possess:“Vietnam and the Philippines are the most promising growth spots in ASEAN”, according to the Asian Competitiveness Institute at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (Asian Competitiveness Institute, 2016).

In the ASEAN Economic Community report, paragraphs 1, 2, 5, 8 state that the region chosen for research in this paper is striving to become a “a highly competitive economic region, a region of equitable economic development and a regions fully integrated into the global economy”(“ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint,” 2008). The above paragraphs from the ASEAN report are reinforcing their importance by paragraph 55, section B2 – Infrastructure development, where the following is stated:

“… it is important to ensure that such development is sustainable through, among others, mitigating greenhouse gas emission by means of effective policies and measures, thus contributing to global climate change abatement. Recognising the limited global reserve of fossil energy and the unstable world prices of fuel oil, it is essential for ASEAN to emphasize the need to strengthen renewable energy development, as well as to promote open trade, facilitation and cooperation in the renewable energy sector and related industries as well as investment in the requisite infrastructure for renewable energy development” (“ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint,” 2008, page 22).

As stated in the Southeast Asia Energy Outlook report, all countries in the region “will achieve universal energy access by early 2030, using a wide range of technologies” 5(IEA, 2017). Currently, Southeast Asia is an important user of the energy mix, but will face several challenges in the near future in their quest to meet the energy demand (IEA, 2017).

Theoretical contribution: Therefore, the research sees a high potential for the emerging countries of the ASEAN region to directly implement RE in areas where the energy demand is now on the rise. Supplying it with popular energy mix would preferably not be on the discussion table due to the current status in global warming. Still, there is a slow process since the countries don’t have the means to support

5 Sustainable Development Goals refer to universal energy access as universal access to affordable,

reliable and modern energy services in goal 7 – Affordable and Clean Energy (Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform, 2017)

RE investment (IRENA & CPI, 2018). They are now trying to eradicate poverty through industrialisation, which means that funds are being redirected into that area.

Practical contribution: This research paper hopes to be of use to organizations that are now lobbying for the development of RE in ASEAN, such as the Chambers of Commerce of interested countries with ties to the ASEAN region. It could also serve useful to policy makers in the region since the study hopes to find the hindering forces behind the development of RE. Last, but not least, the research hopes to be an eye opener to the people of ASEAN and to show them the potential that this new technology has and how it can positively impact their country on all levels of sustainable development with close to immediate impact. With the inclusion of the NGO’s in the decision- and design process of the RE implementation, as well as the NGO’s acting as a connection between the civil society and the governments, this paper tries to contribute in increasing the awareness process in RE.

CHAPTER 2. THEORETIC AL FR AMEWOR K

The following chapter is divided into three main parts, starting with the problem tree, that describes how the authors organized the theoretical foundation for the study, followed with discussion theories in relation to collaborations between governments and organisations for sustainable development and concluding with a description of the PESTEL. These different parts will build the theoretical framework that is used for this thesis, which is used for a macro-level analysis of the topic. The research duo decided to focus on this level because it is the most interesting when it comes to international collaboration in ASEAN to achieve RE development and implementation. The macro factors of political, legal, economic, environmental, social and technological highlight important factors that play a large role in why the implementation and development phase of RE is lacking in ASEAN.

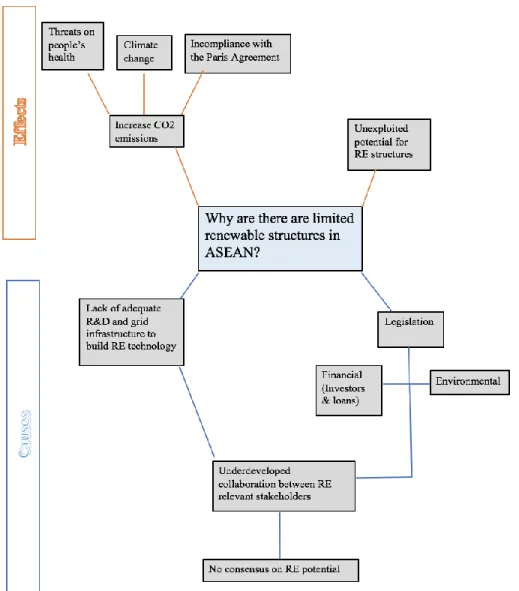

2.1 THE PROBLEM TREE

In trying to identify the causes and effects of the problem that this research is exploring, the writers have developed a problem tree (see figure 4). The tool was created using the methodology from the “Manual for Logical Framework Approach” (Vagnby, 2000).

A problem tree is “an image of reality that represents the main obstacles and negative effects in a certain situation and the relationship between them” (Vagnby, 2000, pg 17). The tool has helped to better clarify the causes of the researched problem as well as its (negative) effects. By simplifying the problem through identifying the causes, the minimizing effects process becomes clearer (Vagnby, 2000).

The central problem was identified as “Uncertainty of why there are limited Renewable Energy (RE) structures in Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines” (Zhu, 2010, European Comission, 2015). SE Asia as a region has an untapped potential for renewable energies that could, in the long run help improve the economic and local development and offers energy security because if RE is managed correctly the source can be infinite (Ottinger, Leong, & Delos Santos, 2013, Sample, 2008).

The next two sub-chapters will further elaborate on the causes and effects of the established problem tree.

2.1.1 CAUSES

The lower half of the problem tree is focusing on the causes and is divided into two main sections, that have been developed from research in secondary data. The first one is “Lack of adequate R&D and grid infrastructure to build RE technology” while the second one is “Legislation”. In this research “legislation” focuses on the policy making and policy structure to simplify the implementation of RE in ASEAN. Structural policies affect the economic structures of a country in the long-term due to the fact that it influences the choices made by the private and public sector. Further structural policy highlihgts all of the changes that can be made in the legal and bureaucratic structures and the relationships in the economy that influence these structures (Allard, 2018).

To understand and grasp all state of the art technology within the RE market requires extensive research. This also becomes a challenge if the country has limited financial resources to invest in the domain and in addition makes them very dependent on countries and companies, who have the technology.

Thus, the barrier for the emerging countries lies in having no financial assets for the development and in combination between consistently depending on others and not having strategies in place to become independent (Ottinger et al., 2013, Brahim 2014, Zamora, 2015, Renner et al., 2015). This brings us to the second cause, legislation, which was further split into financial policies (investment) and environmental policies. Most of the ASEAN countries are focused on coal and gas power solutions. This is due to the fact that some countries have rich resources (e.g. Vietnam and Malaysia), but also underlines these countries who put less focus on RE development lack in a future-thining and future-planning vision (“VIETNAM Energieeffizienz und Energiemanagement in Vietnam,” 2017).

These two main causes form a third important cause that overall underlines the main problem – limited RE structures in Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. The difficulty of the communication process between stakeholders involved in the industry should optimally flow without complication. Because if miscommunication and other difficulties within collaboration appear, problems for the stakeholders in their desire to invest and develop RE structures emerges.

Although some countries started to evolve their legislations regarding RE, the effects are still small and arrive very slowly (Brahim, 2014, Renner et al., 2018, Santos, 2013). Thus, this research will also focus on this problem: the collaboration between governments and the private sector and what the barriers are for the complex collaboration.

There is a high retention for investors due to instabilities and risks in communication process and political environment, which also underlines the last cause within the problem tree “No consensus on RE potential”. This is highly important as well as a negative effect that might be the cause for the focal problem in the problem tree. By not making themselves appealing to internal and external investors, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines are having difficulties in working towards solving the effects mentioned above (Ane & Rosellon, 2017, “VIETNAM Energieeffizienz und Energiemanagement in Vietnam,” 2017, Renewable Energy Agency, 2017).

2.1.2 EFFECTS

The upper section of the problem tree depicts the effects that are encountered. They were divided into two main categories. The first one, “Increase in CO2 emissions”, is further split into other inter-related effects

of equal importance: climate change, threats on people’s health and wellbeing, as well as incompliance with COP 216 (Knopper & Ollson, 2011, Song, Sun, & Jin, 2017, “United Nations Treaty Collection,” 2018). Climate change is affecting Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines by means of drastic weather conditions like draught, heavy and violent rain, heat waves, etc (“Impact of Climate Change on ASEAN International Affairs. Risk and Opportunity Multiplier,” 2017).This has a direct impact on the people’s quality of life by creating health problems (e.g. asthma, lung cancer) or by affecting the agriculture of the region, which leads to difficulties in providing food. Lastly, by having increased CO2 emissions, Indonesia, Vietnam and

the Philippines are also not compliant with the COP 21 agreement signed in 2016 (“United Nations Treaty Collection,” 2018, Knopper & Ollson, 2011). Lastly, the problem tree has helped the writers discover a third effect: “the unexploited potential for RE structures”. Given that the RE trend comes from Europe and the USA (IRENA & CPI, 2018), the emerging countries could benefit from collaborating with these countries for education, technology and production advises.

The problem tree has helped in better understanding the problem areas through the underlining and prioritizing of causes, effects and development of the central problem.

2.2 COLLABORATIONS BETWEEN GOVERNMENTS AND ORGANISATIONS

FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVE LOPMENT

The policy makers of international environmental law recognized already in 1992 during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that for a sustainable development the cooperation between the civil and business sector needs to be given (Harangozó & Zilahy, 2015). Within the global issues of climate change, energy security and water scarcity, it becomes clearer that all three sectors (government, private sector and civil society) need to work together to lower the risks of failure and to create a more effective and successful cooperation between all three actors regarding projects in sustainable development (L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006) (Kaye, 2013). All three actors need to contribute to a more sustainable development because they all had a dismissive approach to growth by neglecting the impacts of waste, excessive water consumption and environmental degradation. According to Kaye (2013), NGO’s can be the missing link between the private sector and governmental institutions to act as consultants on how to change operations to be more sustainable.

The following chapter will provide an overview regarding the different theoretical frameworks on collaborations between different sectors (governmental, private sector and civil society) to achieve sustainable development and to tackle complex sustainable global issues. Regarding the collaboration between governments and organisations, the impact that civil society can achieve for sustainable development should not be underestimated. Collaborations can take a variety of different forms and act under different lengths of time. For instance, collaborations can be within institutions partnering for a specific project from different departments, or they can be between different actors of the three sectors within a society (Van Huijstee, Tte, Francken, & Leroy, 2007, L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006, Selsky & Parker, 2005). This chapter will mainly focus on the later one. The problematisation of environmental issues has been done by Hartman et al. (1999), who addressed that these increasingly complex issues cannot be tackled only by governmental actions but need the help of the private sector including businesses, NGO’s,

6 COP21: The United Nations Climate Conference in 2015 in which the Paris Agreement was signed (The

citizens and other stakeholders. Thus, Hartman et al., (1999) identified that to solve these issues, cross-sector collaborations will have good potential to find better solutions (Maak & Pless, 2009, page 537). Civil society actors, such as NGO’s can have immense power in raising awareness regarding specific topics, e.g. RE and help, as advocacy networks with matching events and communication between civilians and the governance (L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006). Brown and Timmer (2006) argue that within transnational governance the cooperation between governance and civil society actors (e.g. NGO’s) becomes a problem solver in many domains, including environmental protection, democratic energy, sustainable development and corruption. The area of transnational problems is mostly focused on social, economic and environmental challenges. Also, the challenges that are connected to the successful implementation of RE in ASEAN on high developed levels are in different areas and involve many different departments on a governmental level, such as legislation, but also within technology and social capital. Therefore, the concept of transnational social learning capacities underlines to adopt a better overview of managing risks and recognizing opportunities when facing multilevel challenges (L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006). Further, the authors developed a five-step learning process in transnational governance to tackle challenges in policy making and other contexts:

- “(1) identifying emerging issues, - (2) facilitating grassroots voice,

- (3) building bridges to link diverse stakeholders,

- (4) amplifying the public visibility and importance of issues, and

- (5) monitoring problem-solving performance”(L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006, page 6)

Florini (2003) underlines that for a growing number of international and national challenges that are connected to human societies and development, the existing institutional arrangements are tested and the existing structures are questioned, due to the lack of effective solution practice. To tackle these issues, the authors clain that the involvement of multiple stakeholders plays an important part so that the skills and knowledge that is often required to solve these challenges, can be combined for more practical solutions (L. D. Brown & Timmer, 2006, De Los Ríos-Carmenado, Ortuño, & Rivera, 2016). Thus, the evolving benefits of cross-sectoral collaborations according to Brown and Timmer (2006) can be an increase in sustainable problem-solving because actors come from different domains and levels and have thus different capabilities, knowledge and skills to identify, address and solve challenges; further, the cross-sector collaborations can increase awareness, capacities and repertoires within the social domain that has not been established before.The authors identified several reasons of the benefits of collaborations between government and the private or public sector, that can enhance innovation, development and help the smart solution process. Therefore, their theoretical input is highlighted in this research to support the theoretical framework of this paper.

Other articles also underline that partnerships can support development. The authors Reed & Reed (2009) note that partnerships between the government and the private sector (e.g. businesses) or partnerships between governments and social actors (e.g. NGOs and local community organizations) are gaining importance on a global scale (Harangozó & Zilahy, 2015). Especially, within the green movement, NGOs seem to have a large impact on business relations and how they can influence corporate greenifying. This means that NGOs can have the power to push corporateion to more sustainable and environmental friendly business procedures (Salla Laasonen, Martin Fouère, & Arno Kourula, 2012). But not only stakeholders from the civil society can enhance the results and solutions for challenges by collaborating with the government. Also, research institutions can help governments to understand certain aspects of the macro-level, to support sustainable production and consumption systems (Corral & C.M., 2003, Harangozó & Zilahy, 2015). However, in ASEAN context, this can also lead to a better understanding on how policies

should be changed or added with the help of research centres and NGOs (Teegen, Doh, & Vachani, 2004, page 477).

2.2.1 INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE ON INTERSECTORAL COLLABORATIONS

The collaboration between above named sectors (governmental, private-sector, civil sector) are also often named intersectoral collaboration, which can be described as collaborations between actors that come from different backgrounds within society (Van Huijstee et al., 2007). Van Huijstee et al. (2007) discussed two main reasons why the rise of intersectoral collaborations increased in the last decades. Firstly, she highlights the fact that sustainable problems are often characterized by complexity and thus require the partnership of different actors to be able to solve the issues, this was also discussed during the 1992 WSSD. Secondly, the concept of sustainable development underlines the balance between social equity, environmental health as well as financial wealth (Arts, 2002, Van Huijstee et al., 2007). This puts in context what has been earlier separated:“Business for economic development, government for the protection of public goods of which social and natural capital are important aspects), and civil society for the enhancement of civility and social cohesion (of which social and environmental quality are important aspects as well” (Van Huijstee et al., 2007). Further, Van Huijstee et al. (2007) identified two separate theoretical frameworks in regard to intersectoral collaborations: institutional perspective & actor perspective. She describes the actor perspective as a means to another instrument to achieve actor-specific goals, which in the case for the private sector, e.g. businesses could be to focus on their corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy. However, actor perspective is mostly focused on the private sector and how it can collaborate with civil society actors, therefore this paper will focus more on the institutional perspective (Van Huijstee et al., 2007). The institutional perspective focuses on the governance regime. Governance is described as “the overall system of steering mechanisms in society, in which traditional top-down government steering is only one among many governance options” (Van Huijstee et al., 2007). Other governance options are described by Visseren-Hamakers & Glasbergen (2007) later in this chapter.

Further, the institutional perspective underlines a natural alignment and fusion between governance actors and private actors or civil sector actors to support the governance on mostly environmental problems within the country. One example of this partnership, can be the UK model of public-private partnerships, which is a role model for enhancing sustainable development, driven by the private sector and influencing the government (Kaye, 2013)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b)(Kaye, 2013b). This project helped specially in developing the public road infrastructure, which is also one major issue in ASEAN for RE project development since civilians do not want RE projects close to their homes due to different types of pollution (e.g. noise) (Knopper & Ollson, 2011). Also, the institutional perspective focuses on national and global society at large, thus underlines the macro perspective that this research is focusing on.

2.2.2 COLLABORATIONS FOR POLICY MAKING

Regarding the context of collaborations for policy making, the research by Arts (2002) and Pattberg (2004) needs to be pointed out. Arts (2002) underlines the benefits of private sector collaborating with NGO’s on environmental policy making and regulations in his research paper. The author also analysed the effectiveness of the “green alliances” from a political modernization and policy arrangement perspective. Here, political modernisation underlines actors from the government, private sector and the civil society (Arts, 2002). Thus, Arts’ (2002) research stresses out that more green energy alliances are formed because firstly the actors from all three sectors want to be more involved into the environmental regulation and

policy making; secondly, the above-named actors are also more concerned about sustainable development and therefore want to change policies to enforce these sustainable developments. Pattberg (Pattberg, 2004) researched within the industrial transformation research field, which aims at finding sustainable solutions for the constant driving forces within the world that demand change. Here, the complex characteristics of sustainable solution findings are highlighted. Within his literature analysis, Pattberg identified the gap on coherent research on the importance of private institutions being a support for global governance. The author argues that civil society actors have only started to become involved in environmental policy making and sustainable policy research (Arts, 2002, Tamiotti & Finger, 2001, Reinalda & Verbeek, 2001).

Further, Pattberg (2004) developed a conceptual framework of private rule-making by institutions (private-sector) that can provide research and consultancy for governments. The author discusses “how the valuable contribution of partnerships can be integrated into a democratic and legitimate governance of global environmental affairs” (Pattberg 2004, p.64) . Other researchers also argue about this challenge and come to the conclusion that public-private governance increases the discussion on policy-making, but that these collaborations are often not democratically chosen (Van Huijstee et al., 2007, Blowers, 1998, Ottaway, 2001). Nonetheless, most of the above-named authors argue that there needs to be certain conditions set before collaboration can be created and become beneficial for both sides (Arts, 2002, Streck, 2004, Pattberg, 2004, Bäckkstrand, 2006). While some argue that NGO’s goals need to be within the core of the collaborating company (private-sector), or within the environmental focus when focusing on the government (Arts, 2002), other stress that supranational organizations should become more important to the government when discussing institutional environmental regulations, the so called “global public policy networks”. This network indicates that governments should collaborate and shift responsibilities with different actors in the same or cross sector to decide upon policy makings (Bäckkstrand, 2006). Samii et al. (2002) highlight five main pre-conditions for a successful partnership;

- (1) resource dependency (actors understand that they can only succeed together and not alone) - (2) commitment (willingness to share resources)

- (3) overlapping goals (collaboration highlights reciprocal advantages)

- (4) converging work cultures (“partners do not have to be the same but should not exclude cooperation”(Samii et al., 2002)

- (5) intensive communication.

Charlotte Streck (2004), who is known for her research in environmental policies and clean development mechanisms (CDM), that were developed during the Kyoto Protocol 7and focus on new models of governance. CDM analyse how collaborations between the government and external actors benefit policy making and implementation of international treaties. In addition, it is designed to enrich the cooperation between industrialized and emerging countries for sustainable development and the reduction of emissions (Streck, 2004, page 296). The authors stress especially the benefits of collaborations that work on implementing regulations that have been made internationally (treaties) or nationally and help local actors with the implementation processes. Further, she proclaims that governments often lack the resources as well as political future view, to achieve the goals and changes that have been made on an international level. Thus, governments are lacking the capabilities to achieve sustainable development without partnership. This has mainly also to do with the changing environments that governments work in and that the adaptation phase of governments is slow (Streck, 2004). Consequently, governments need to be more open minded to partner up with the private-sector and delegate aspects to external actors with the goal to build a stronger “global public policy network” (Streck, 2004 Reinicke 2000).

Also, other authors highlight the need for structural changes within the governmental systems.

7 “The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which commits its Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets.“ (United Nations Climate Change, 2017)

Visseren-Hamakers and Glasbergen (2007) published a research paper on the partnerships in forest governance. Their paper analysed the lack of active regulation implementation by governments and examined the positive impacts that private-sector actors could have to limit the lack. The authors came to the conclusion that governments should change their structure from a top-down hierarchy to a “meta-governance”, to be able to face the multilevel challenges from the environment. The concept of metagovernance underlines political fair-play and highlights the building of networks between government and external actors to support the implementation of regulations nationally (Ingrid J Visseren-Hamakers & Glasbergen, 2007). The conclusion of Visseren-Hamakers & Glasbergen (2007) correlates with Bäckstrand (2006), who stressed out the rise of global public policy networks.

Another perspective to look at cross-sector collaborations is from a stakeholder group’s angle. Here, Selsky and Parker (2005) published several research papers that analysed how organisations from the private and public-sector can collaborate with another. Also, they highlights that during these collaborations the actors receive different perspectives on the issue, become motivated by different goals and to also apply different tools and approached to find solutions for the challenges. Also, the challenges within social issues are often multifaceted, and therefore traditional settings for solution findings are often not capable to tackle these challenges any longer without collaborations (Selsky & Parker, 2005, Waddell, 2005).

As mentioned throughout the chapter the collaborations between governments and different sectors (e.g. private or public) will underline a deeper understanding and analysis of benefits and obstacles within these collaborations to help governments improve their sustainable development processes. Also, the concept of collaborations between different parties will help to answer the research question.

2.3 PESTEL FRAMEWORK

To provide a better understanding of the impacts in the implementation phase of RE in ASEAN, the PESTEL framework helps to analyse the area on a macro level from six different perspectives. This framework will also help to identify and give suggestions to overcome several obstacles that have emerged in the implementation of RE in ASEAN.

The PESTEL framework indicates an analysis from six different perspectives, which will be broken down to further sub-factors: P Political E Economic S Social T Technological E Environmental L Legal

For sustainable development it is recognized that environmental factors play a large role in the planning process for long-term goals in industries. The underlining idea behind the PESTEL analysis is that organisations (including governments and companies) can understand the market conditions better and learn to react to external changes to cope with the market conditions (Gupta, 2013).

Political impacts in this research analyse the political system, in specific in ASEAN countries the general

political agreements on RE. Economic changes or impacts include the effects of economic cycles, financial means of a country to integrate RE, labour markets and rates and the economic relationship to specific suppliers of RE tools and customers. Social impacts and changes include the awareness level of citizens to RE, concerns about environment and sustainable development for instance. Technological barriers and drivers covers the technological know-how on products and product-use in terms of smart-grid for instance.

up to political agreements, e.g. Paris agreement. The legal barriers and drivers will focus on regulations and legislation in ASEAN countries, regarding RE development, sustainable investments for RE and open trade regulations (Gupta, 2013; Song, Sun, & Jin, 2017, Akella, Saini, & Sharma, 2009).

2.3.1 DEVELOPMENT OF A CONCEPTUAL FRAME AS AN ANALYTICAL TOOL TO

IDENTIFY THE DRIVERS AND BARRIERS BASED ON THE PESTEL FRAMEWORK

The PESTEL framework provides a good base to understand the different impacts from six different perspectives on a macro-level. To further understand the drivers and barriers from a literature point of view the research duo created an analytical tool that identifies the current status of each perspective in regard to implementing green energy. The political and legal perspective are combined because they intertwine in many aspects, thus the combination makes it easier for the reader to understand the parallelism. This research will refer to an analytical tool as “an analytical way of doing an analysis that involves the use of logical reasoning” (“Cambridge English Dictionary,” 2018).POLITICAL AND LEGAL APPROACH

This subsection will introduce the current relevant topics from a political and legal perspective to RE. One of the biggest discussed topics on RE is the emerging social movement term of democratic energy, which enhances the transitions to RE by resisting fossil-fuel energy production while at the same time trying to create a more balanced energy mix. The movement is calling for more social justice by linking policies together with economic equity to RE transitions (Burke & Stephens, 2017). Several ASEAN governments announced new policies and better political support for the renewable energy industry in their countries (ACE, 2015).

However, ASEAN are still in disadvantage in several factors compared to developed nations. Especially in the financial sector, which in a final result often effects the political sector as well. For instance, Vietnam’s second biggest energy source comes from coal plants (“VIETNAM Energieeffizienz und Energiemanagement in Vietnam,” 2017). The country also has high resources of natural coal reserves, however, it is also facing a coal shortage and need to import coal since 2015 because the nation exports its own high-quality coal to other nations and then imports lower quality coal from e.g. Malaysia, Russia and China (M. Brown, 2018, IEEFA, 2017, IEA, 2017). However, the coal prices are rising and according to the IEEFA, Vietnam should start focusing on other energy production methods to become more independent and prepare for future demands (ACE, 2010, “VIETNAM Energieeffizienz und Energiemanagement in Vietnam,” 2017). A higher cooperation between ASEAN and their different energy production methods could also help to become a higher independent collaboration of nations and become more independent from other energy suppliers outside of the region, which will be be further analysed in chapter 4. ASEAN countries have the power to influence their market with different political and legal tools, e.g. fiscal and non-fiscal incentives (feed-in-tariffs; green energy options etc.) (Santos, 2013).

ECONOMIC APPROACH

“These factors are determinants of an economy’s performance that directly impacts a company and have resonating long term effects. For example, a rise in the inflation rate of any economy would affect the way companies’ price their products and services. Adding to that, it would affect the purchasing power of a consumer and change demand/supply models for that economy. Economic factors include inflation rate, interest rates, foreign exchange rates, economic growth patterns etc. It also accounts for the FDI (foreign direct investment) depending on certain specific industries who’re undergoing this analysis” (Rastogi & Trivedi, 2016, page 385).

The renewable energy market starts to become a big industry for the financial market, because energy demand is rising and private-companies as well as investors want to be part of it. Many governments signed

the Paris agreement and in additional other agreements that all underline a more sustainable development within the energy industry, thus investing into RE (ACE, 2010, Akella et al., 2009).

SOCIAL APPROACH

“The sociological factor takes into consideration all events that affect the market and community socially.” (Rastogi & Trivedi, 2016, page 385).

This also underlines that the surroundings of the public or communities need to be considered. Examples for these events within the social approach, can be cultural expectations, norms, population dynamics, healthy consciousness, career altitudes, global warming, etc. Taking these factors into account is very important when analysing this macro-level because the factors have a direct effect on current cultural trends and demographics for instance (Rastogi & Trivedi, 2016, page 385).

From a social perspective, RE also has small side-effects on close by living communities. For instance radio and TV receptions suffer from close-by wind farms because of connection issues. However, renewable energy also offers new jobs within countries where the unemployment rate is high (Johnson, 2014).

TECHNOLOGICAL APPROACH

When analysing the technology level, crucial factors are within innovation and R&D. That determine whether a market is favourable or not for e.g. technology organisations or new development projects. Further, the innovation and R&D sector underline technological awareness and automatization of systems within the analysed market (Rastogi & Trivedi, 2016, page 385).

Especially for this section, the research duo discused certain changes with experts, regarding doing RE in Europe and in a tropical climate in ASEAN. From a technology point of view, there might be many differences regarding planning and maintenance, that are interesting to find out and to compare, to see whether these are some factors that are included in the barriers of foreign investment.

ENVIRONMENTAL APPROACH

“These factors include all those that influence or are determined by the surrounding environment. Factors of a business environmental analysis include but are not limited to climate, weather, geographical location, global changes in climate, environmental offsets, ground conditions, ground contamination, nearby water sources, etc. (Rastogi & Trivedi, 2016, page 385). In this section the focus will be especially on environmental NGOs, because they have potential to be the strongest awareness raiser in ASEAN, due to the fact that education is rather general and not targeted on energy and RE within these nations (The World Bank Group, 2014).

The PESTEL framework underlines a structured analysis of the macro-level areas that affect the process of sustainable development and the implementation of RE in ASEAN. The research in the six different approaches highlights that there is an information gap to connect all approaches to the implementation in RE because many reports do no mention these categories within their reports, but mostly focus on political, legal and economic information about ASEAN countries.

CHAPTER 3. RESEARC H M ETHODOLO GY

The goal of this research thesis is to explore and describe how could the RE development evolove in the ASEAN from different aspects (legislation, financial, environmental regulations, cross-sectoral collaboration). Also, the research will focus on the collaboration between organizations in private sector and governments of the focused countries.

As with many other emerging fields, both the theories and observations about the green energy concept in ASEAN countries are still in their early development stage. Out of this consideration, the authors decided to take a more in-depth look into the phenomenon using a qualitative approach.

The study is an inductive study with the data gathered from an expert panel composed of ten specialists in the RE sector in ASEAN. The study is framed as inductive since the data analysis has been made through observations and search of patterns within the data (Woo, O’Boyle, & Spector, 2017). This distinction needs to be made since “scientific inquiry typically involves alternating between deduction and induction. Both methods involve interplay of logic and observation and both are routes to the construction of the thesis (Babbie, 2010). Induction was chosen as a framing since the research started with a discovery process of a problem (inductive observation) and proceeded with find the explanations needed (Hanson & Hanson, 1958).

3.1. RESEARCH DESIGN

The nature of the research strategy chosen for this research thesis is guided by the research question developed. More precisely, the method chosen to conduct this research is based on semi structured interviews since the expert perceptions were sought after. Interviews were used since contact with the experts chosen for data collection were based in ASEAN and this contact method was preferred by interviewees and interviewers compared to surveys for example.

The main goal and starting point of the research was to gather information about a rather new domain in an emerging market (ASEAN). Therefore, literature reviews from reports from within the region as well as interviews and their analysis were used. The interviews have been made with different experts in RE in the region of ASEAN. As explained earlier in the research, by expert perception, the study refers to the angle of the specialists from within the energy industry, such as wind power engineers, energy economists, energy professors, advisors on RE, global energy investment specialists. The experts in the domain are professionals with 10+ years of experience in the RE sector with a special focus on ASEAN.

The research strategy will follow the main steps of a qualitative research as presented by Bryman in “Social Research Methods” while semi-structured interviews will be considered primary data and the e-research of RE reports from within the RE sector, as well as peer reviewed articles in the RE domain, will be considered secondary data (Bryman, 2004, page 268):

Step 1 – General research question: this is the starting point of the research as well as the catalyst for the

research process. The broad question of “What is the future of renewables in SE Asia and what is the current status in the domain?” has always been ground for discussion (ACE, 2015; M. Brown, 2018; IEA, 2017; Khuong, 2017; Shi, 2016). Through multiple brainstorming session as well as informal talks to peers, the research duo managed to narrow down the research question to the one presented in chapter 1.3.

Step 2 – Selecting relevant subjects: once the research question has been made definitive, the research

process continued with a literature review. Being that the focus is RE, there is a majority of reports coming from the IEA – International Energy Association as well as IRENA – The International Renewable Energy Agency.

Step 3 – Collection of relevant data: according to Bryman in “Social Research Methods” (Bryman, 2004),

there are multiple research methods associated with qualitative research. This research will use both qualitative interviewing as well as the collection and qualitative analysis of reports and documents from the field of RE in this researched area.

Step 4 – Interpretation of data: the data will be analysed through conventional content analysis on the

topic of RE in the ASEAN countries (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Also, the interview findings will be analysed through a coding process (see chapter 3.3.)

Step 5 – Describing findings/conclusion: main key findings will be discussed from a critical point of

view and will portray the expert perceptions on RE development and implementation in the region studied. It will also show the governmental regulations and policy structures made use of in the implementation process of RE.

In step 3, the selection of the interviewed persons was made using the e-network of each of the researchers. Also aid from professors from Malmo University, Faculty of Culture and Society at the Department of Urban studies was used in order to reach a larger number of professionals within the domain.

The researchers also used a two folded recruitment process – one researcher used mainly LinkedIn and contacted contacts from within the network. Also, a LinkedIn post was made with a call for participation, which was viewed more than 1.300 times and that put the researchers in contact with professionals from outside their network. The other half of the research duo contacted German and Swedish Embassies and Chambers of Commerce in ASEAN countries. This has brought in more data since some professionals were not available for tele-conference interviews due to their work schedules. However, they provided the research team with reports from 2017 and 2018 that portray the RE situation in the respective countries or with written/recorded answers to the interview guide.

The interview structure was semi-structured interviews. An interview guide was developed with a focus on finding answers to the main research question as well as sub research questions. Mainly the interviewee had a great flexibility in choosing how to reply. The approach and the researchers encouraged the interviewee to respond freely, without setting any boundaries to the chosen method to reply. This way raw information was gathered and used further in the analysis. Also, by having interview questions that begin broad in scope, the researcher can could ask more specific questions along the interview, making the interview process more direct and targeted on aspects of interest along the way.

Another extremely important mention needs to be made: due to the focus of this research geographical wise and the limited time frame for conducting the research, some of the interviews were conducted through VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol), more commonly known as Skype (Lo Iacono 2016). This type of method of communication is growing increasingly important since it can open new research doors all over the world.

VoIP opens new contact possibilities in contacting interviewees in a time efficient as well as economically affordable manner. However, the drawback of the VoIP is that the interviews conducted through this tool will not portray non-verbal cues or face expressions that could also be included in the analysis part as interviewer input (Lo Iacono, 2016).

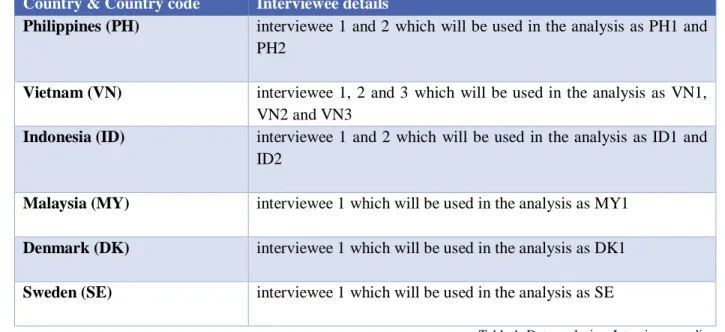

3.2. KEY INFORMANT (SELECTION OF INTERVIEWS)

The study used qualitative analysis of reports and documents in the field of RE in ASEAN as well as semi - structured interviews. The authors decided to pursue with a mixed data collection design since data resulting from multiple sources can further help in the analysis stage, given that multiple perspectives can

provide a holistic picture and allow for a more critical reflection and result formation. The semi-structured interviews will be considered primary data and the e-research of RE reports from within the RE sector, as well as peer reviewed articles in the RE domain, will be considered secondary data.

In order to receive more specialised data, interviews were conducted with experts in the field of RE, also known as key informants. The structure of the interview is semi structured, with the interviewees as highly qualified professionals within the sector from which there is a wish to extract data from. The experts are professionals within the RE sector, such as wind power engineers, energy economists, energy professors, advisors on RE, global energy investment specialists.

The selection of the expert panel was done by the authors with four main categories in mind. The categories for selection were chose after reviewing reports from the RE sector developed by similar experts:

- relevance to the RE sector

- experience within the RE sector (all professionals are at a senior level) - involvementt in RE in international projects

- specialists in RE currently based in ASEAN and working in the industry

The four main categories above were used to make sure that the experts fully understand the topic of this research paper, thus having a meaningful input.

The key informant framework was chosen for the study since it “can help gather qualitative and descriptive data that would be difficult to unearth through structured data gathering techniques such as questionnaires or surveys” (Tremblay, 1957).

3.3. DATA ANALYSIS / CONTENT ANALYSIS

The research targets experts from the field of RE and that have knowledge of the implementation of RE in not yet fully explored areas of SE Asia.

In order to gather data from multiple aspects of RE, professional with different focuses have been interviewed: off-shore wind structures engineers, green energy experts, professionals within renewable economics, etc. Overall, since the persons approached and interviewed have different backgrounds and the information that can be extracted from them is of different nature, but with the same scope, the interview questions will be different and adjusted for each professional category – engineers, energy expert, energy economist, etc.

The analysis was performed with connection to the theoretical framework of the cross sector-collaboration based on institutional perspective by Van Huijstee et al (Van Huijstee et al., 2007). Also Streck (Streck, 2004) established the global public policy network which describes environmental regulation policy making in collaborations. The analysis will run through the theoretical framework to see if the current situation in the researched countries corresponds or overlaps with the existing research in the field.

Some experts come from the GIZ pool of researchers in the ASEAN. GIZ is the German Government Cooperation Agency (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH) with a focus on different development projects in education, economics, politics, technology, etc. The interviews were made with experts from the wind development projects that GIZ is running in ASEAN.

GIZ was chosen since Germany is among top leaders in RE in Europe and they also are among the countries that possess the know-how in the RE sector through their large companies like Siemens.

The selected experts were from Philippines (coded as PH), Vietam (coded as VN), Indonesia (coded as ID), Malaysia (coded as MY), Denmark (coded as DK) and Sweden (coded as SE). The codes stand for the internationally known country codes.