Malmö University School of Arts & Communication K3

Museums on Instagram

Engagement with audiences on social media

Maria Algers

Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries One-Year Master’s Thesis, 15 Credit Points

2018

Examiner: Bo Reimer

Date of examination: 10th September 2018 Advisor: Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt

Abstract

This thesis will explore the engagement modes of museums on Instagram by looking at the content of 1230 posts published by forty museums in Sweden and New Zealand over a three month time period. The analysis will focus specifically on the museums intention behind each post, with the use of an analytical grid developed by Lotina and Lepik. The museums’ invitations for engagement and participation with their audience will be the main focus of the study,

drawing on concepts of civic engagement and the role of public institutions as democratic forums where collaboration is championed. The results indicate a trend of a low number of invitations for the public to collaborate and engage with the museum, while marketing is instead the most common engagement mode, in particular among art museums. The concluding

discussion reflects on these results, as well as the initial assumption that museums should be places for democratic collaboration.

Table of Contents

Abstract 1

Table of Contents 1

Figures, Images and Tables 2

1. Introduction 3

2. Background 4

2.1 - An Introduction to the Museum Sector 4

2.2 - Instagram as Museum Media 6

3. Theoretical Framework 7

3.1 - New Museology 7

3.2 - Web technologies and Multivocality 8

3.3 - What is Participation? 9

3.4 - Citizenship, Participation and Deliberative Democracy 10

3.4.1 - The Issue of Equality 11

3.4.2 - The Issue of Representation 11

3.4.3 - The Issue of Authority and Authenticity 12

3.5 - The Duty to Engage 12

4. Previous Research 13

4.1 - Lack of Funding and Strategy 13

4.3 - Lotina and Lepik’s study 15

5. Research Aim and Questions 17

6. Methodology 17

6.1 - Data Collection and Sample 18

6.1.1 - Museum Selection 18

6.2 - Data Analysis 20

6.2.1 - Engagement Mode Categories 23

6.2.2 - Application of the Categories 26

7. Ethics 27 8. Results 28 8.1 - Informing 30 8.2 - Marketing 32 8.3 - Consulting 35 8.4 - Collaboration 36

8.5 - Connecting with Stakeholders and Professionals 38

8.6 - Connecting with Audiences 39

8.7 - Image 43

9. Discussion 44

9.1 - Assumptions and Expectations 44

9.1 - Understanding the Results 44

9.3 - Museums and Audience Engagement 45

References 48

Figures, Images and Tables

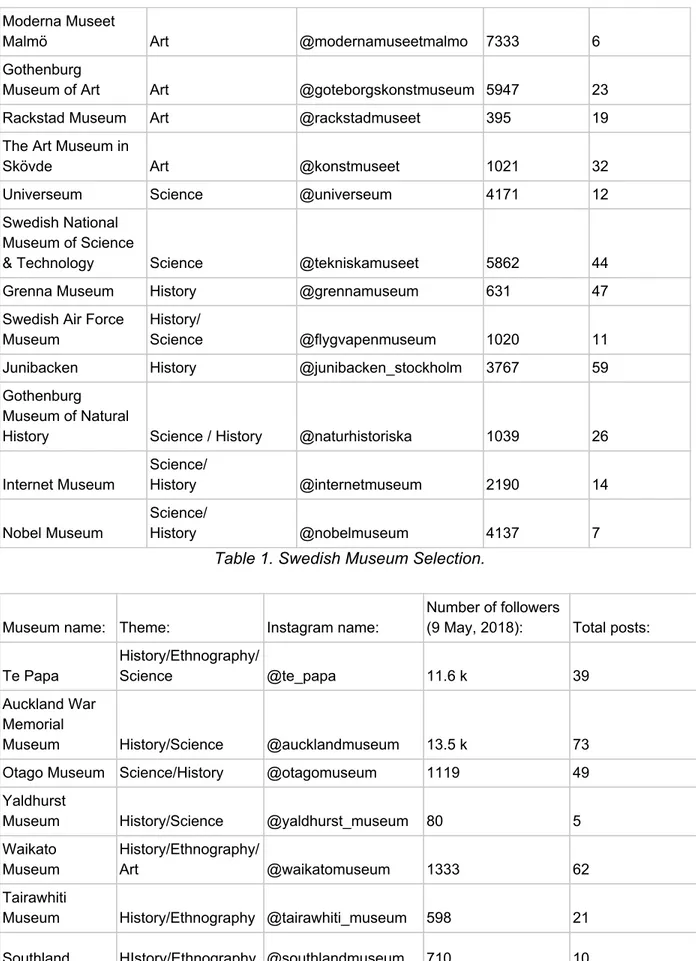

Table 1. Swedish Museum Selection 18-19Table 2. New Zealand Museums Selection 19-20

Table 3. Describing the Review of Engagement Modes 22

Image 1. The Vasa Museum’s Instagram account 21 Image 2. Waikato Museum’s Instagram account 27

Image 3. Malmö Museums’ Instagram account 30

Image 4. Auckland Art Gallery’s Instagram account 36

Image 5. Waikato Museum’s Instagram account 37

Image 7. Grenna Museum’s Instagram account 42

Image 8. Kulturen in Lund’s Instagram account 45

Graph 1. Distribution of Categories in New Zealand Museums 29

Graph 2. Distribution of Categories in Swedish Museums 29

Graph 3. Informing vs. Marketing in New Zealand Museums 32

Graph 4. Informing vs. Marketing in Swedish Museums 33

Graph 5. Informing vs. Marketing in Different types of Museums 34

Graph 6. Connecting with Stakeholders and Professionals vs. Connecting with Audiences in 40 New Zealand Museums Graph 7. Connecting with Stakeholders and Professionals vs. Connecting with Audiences in 41 Swedish Museums Graph 8. Connecting with Stakeholders and Professionals vs. Connecting with Audiences 42

across Museums of Different Themes

1. Introduction

The aim of this thesis is to find how museums use Instagram to communicate with the public, and if they provide invitations for the public to engage.

Social media platforms are rising in popularity, both among private individuals and companies. Museums are now present on sites such as Instagram, where, if they wish, they can

communicate and engage with the public. Museums have voiced their interest in engaging with younger audiences, and some are hoping they may find a connection with such users through social media applications (Hannon 2016). Instagram demographics are ideal for such purposes; recent statistics show that just over sixty percent of users are between the ages of 18-34

(Statista, 2018). Some individuals have also argued that engagement is greater on Instagram than on other Social Networking Sites (SNS), demonstrating preference over other major SNS such as Facebook (Elliott, 2015).This may be particularly relevant to businesses who use Instagram for marketing. This thesis will look at museums’ use of the Instagram site to engage with their audience, and compare museums in two countries: New Zealand and Sweden. By looking at the content created by the museums, the intended engagement mode of each post will be analysed. The research takes the point of view of the museum, and will therefore focus on museum created content, and not on the responses from audiences on Instagram.

The thesis will begin by looking at the museum sector in Sweden and New Zealand, and by describing Instagram as a tool used by museums. The theoretical section will then develop the concepts of participation and engagement, and discuss how these theories pertain to the use of social media by museums. This will provide a basis for the ‘Previous Research’ section, which will use examples of research studying audience engagement in museums, in particular through the use of online channels, to outline the field and contextualise the results presented in this thesis. The methodology section will then outline the methods used for research, and will detail

how Lotina and Lepik’s categories for analysing engagement modes were adapted and implemented for the purposes of this study. The results will be described in relation to each category, and the distribution of engagement modes between the two countries will be

compared. Finally, the results will be discussed with respect to the proposition that museums ought to function as places for democratic engagement.

2. Background

2.1 - An Introduction to the Museum Sector

The museum sectors in Sweden and New Zealand share several similarities. For example, statistics reflecting cultural participation suggest that such activity is high in both countries (Stats, 2018; Authority for Cultural Analysis, 2017). According to a study representing New Zealanders’ participation in cultural activities between April 2016 to April 2017, just over 94% of adults had participated in a minimum of one cultural activity during the one year period, while 78% had done so in the last four weeks (Stats, 2018). Over 15% of respondents had visited an art gallery or museum in the past four weeks (ibid.). Comparatively, 80% of Swedish

respondents in a recent report by the European Commission stated that they had visited a museum or gallery at least once in the last 12 months, compared to a European average of 50% (European Commission, 2017, p. 50). The survey also reflects that Swedes are highly interested in learning more about Europe’s cultural heritage (82% of respondents) (ibid., p. 26), as well as being particularly active cultural heritage participants, compared to the other 27 countries included in the survey (ibid., p. 49-50).

The number of museums in each country suggest that Sweden is more ‘museum dense’, with approximately 1600 museums in relation to the population of 10 million residents (SCB, 2018; Sveriges Museer, 2018). New Zealand, on the other hand, has approximately 470 museums servicing the 4.9 million population (Museums Aotearoa, 2013; Stats, 2018). These numbers indicate that Sweden has approximately 1.6 museums per 10’000 residents, while New Zealand has just under 1 per 10’000.

Museum visitor demographics across the two nations indicate a few typical traits. A 2017 survey of New Zealand museum visitors found that 58% were female (Museums Aotearoa, 2017), while a Swedish study from 2015 suggested that women were more culturally active than men, and women reported visiting museums to a greater extent than men (Authority for Cultural Analysis, 2017, p. 17). In addition to this, cultural activity appeared to correlate with higher levels of education across both countries. The New Zealand survey found that 69 % of museum visitors had a partial tertiary qualification, or higher (Museums Aotearoa, 2017), while the Swedish study reported correlations between higher levels of education and higher levels of participation in cultural activities, in particular with regards to activities such as visiting a museum or art exhibition (Authority for Cultural Analysis, 2017, p. 24). These results suggest that audiences across Sweden and New Zealand share several similarities. But there are also differences worth

mentioning, such as variations regarding the age of the average visitor. While 57% of respondents in the New Zealand museum visitor survey were over the age of 50 (Museums Aotearoa, 2017), the Swedish study found that respondents under the age of 50 were more likely to have visited a museum during a 12 month period, compared to visitors over the age of 50 (Authority for Cultural Analysis, 2017, p. 19).

The figures above suggests that museum audiences in the two countries are similar in several respects, which allows for a suitable comparison. However, attitudes to culture and museums may vary across the two nations. Thus, a look at the Ministry for Culture in each country may help to clarify the nations’ approach to culture, and could also help to contextualise

discrepancies in the results of this study.

The Swedish Ministry for Culture’s Policy Objectives emphasise that “culture is to be a dynamic, challenging and independent force based on freedom of expression, that everyone is to be able to participate in cultural life, and that creativity, diversity and artistic quality are to be integral parts of society’s development” (Swedish Government, 2015). These objectives clearly show that Sweden’s Ministry for Culture consider the public’s participation and access to culture an important goal, while they also argue for culture’s influence on a society’s development. They also highlight that, with regards to cultural environment, their activities should promote “public participation in cultural environment activities” (ibid.). This statement reflects an attitude towards culture which is insistent on its independence and freedom of expression. The statement does also emphasis diversity, which suggests that a number of different views are integral to Swedish culture. The statement also appears to welcome debate through its insistence on culture as a challenging force which everyone is able to take part in and which supports the development of society.

In comparison with Sweden, New Zealand’s Ministry for Culture places specific emphasis on the distinctive nature of New Zealand’s culture and its potential to enrich lives, by describing the government's main goal for the cultural sector in the following way; “The Government’s goal recognises that our distinctive culture is a core part of what makes New Zealand a great place to live. Culture is important to our personal, social and economic wellbeing, as it contributes to positive outcomes for individuals and communities in a range of areas, such as education, health and the economy. A key element in our distinctive culture is its celebration of the place of Māori and our increasingly diverse peoples.” (Ministry for Culture & Heritage, 2015) The

statement highlights the importance of Māori culture, the indigenous population of New Zealand. It is also particularly focused on wellbeing, and the effect which culture may have on both

individuals and society as a whole.

The New Zealand ministry also detailed three desired outcomes in support of this main goal. These include; (1) Create, (2) Preserve and, (3) Engage (ibid). The ‘Create’ outcome is focused of the production of distinctively New Zealand art which is financially successful, while the ‘Preserve’ outcome emphasises the need to preserve cultural artifacts while also providing access to New Zealanders (ibid.). Finally, the ‘Engage’ outcome states that “increasing

participation in and engagement means wider enjoyment of our culture not just by New Zealanders but also by international audiences. This in turn benefits the cultural sector, our wider community, and the New Zealand economy” (ibid.). This focus on participation is to some extent in line with Sweden’s emphasis on the same, however, with a specific focus on the financial benefits that may result from such activity. In fact, New Zealand’s Ministry for Culture mention financial success at several times when outlining their goals and outcomes, while Sweden’s ministry appear to emphasise the vision of culture as an independent and challenging force instead. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but these short statements iterate primary goals and desired outcomes, and perhaps encapsulate the respective nations’ attitude to culture. Sweden’s ministry mentions culture as a force and influence on the development of society, while New Zealand chooses to emphasize its effect on personal wellbeing as well as the wellbeing of society and communities. Regardless, in both cases, culture is extolled as a force for good, affecting and influencing both individuals and broader society.

2.2 - Instagram as Museum Media

The Swedish survey of cultural practices among members of the population found that rural residents participated less in cultural life, compared to urban residents (Authority for Cultural Analysis, 2017, p. 46). While the study suggests that this may be due to demographic and socioeconomic variables, access appeared a significant influence on participation when adjusting for other factors (ibid.). Digitisation was mentioned as a possible tool for providing access to culture in rural areas. Several authors have argued for the possibilities that the internet can provide with regards to museum communication, and some of these articles will be explored critically in this text.

Museums in both Sweden and New Zealand are active on Instagram, as well as other social networking sites, which is not particularly surprising based on the immense popularity of the platform. Instagram was first launched in October of 2010 and was later acquired by Facebook, in April of 2012 (Instagram, No date). By July of that same year, the community had grown to 80 million, and by the end of that year it was available in 25 different languages (ibid.). The

Instagram platform currently claims to have over 800 million monthly active users, with more than 500 million daily active users (ibid.).

Droitcour, writer for Art In America, argues that when museums engage in communication on SNS they become “one of many users” (2017). He suggests that online versions of museums often resemble their physical counterparts, due to their use of design and language with an institutional look or tone (ibid.). They may for example use press images containing branding which also feature on their exhibition posters and museum facades. Droitcour suggests that museums may gain a closer relationship with their followers by using a more personal voice, perhaps through social media ‘takeovers’ where artists are allowed to communicate through the museum’s social networking site (SNS) account (ibid.). The article emphasises the museum’s tone when speaking with its followers, and how they may also use artists to gain a separate view on their collections or events. These methods may be popular with users, who would

probably be drawn to the ‘under-cover’ images that an artist ‘takeover’ may provide. Such positive consequences could be achieved, with the right strategy. A study by Padilla-Meléndez and del Águila-Obra concluded that, while use of social media may be popular and

advantageous, a lack or strategy may cause the negative results to out-way the positive (2013, p. 897). On the other hand, various experiments with tone and engagement on Instagram could help museums connect with their followers, and would be refreshing, as opposed to the often academic and institutional tone one might find on the wall in a physical museum space. Use of Instagram to engage with museums followers will be explored further in this thesis, based on the theoretical framework established below.

3. Theoretical Framework

Since the research undertaken for this thesis is based on previous research by Lotina and Lepik (2015), their theoretical framework is also relevant in relation to this text, and will therefore be explored in more depth. Section 3.1 will begin with a look at the concept of the ‘new museum’ and a shift towards marketing and entertainment in the museum sector, and will then continue with a discussion regarding the concept of ‘New Museology’. Section 3.2 will consider how webb technologies could be used in relation to ‘New Museology’. Section 3.3 will continue with a discussion of ‘Participation’, its use in relation to museums, and its application to this study. The term ‘Engagement’ will also be discussed, since it is the concept which will be used to refer to the study and results presented in this thesis. Section 3.4 will continue with a discussion regarding citizenship and deliberative democracy, drawing on texts by Dahlgren, while

considering several issues with regards to public engagement with museums. Finally, section 3.5 will consider museums’ duty to engage the public.

3.1 - New Museology

Traditionally, museums were seen as custodians of cultural artifacts and distributors of

knowledge. They cared for cultural objects, and were therefore in a position to curate and create the narrative surrounding them, while teaching the wider public about their own culture as well as others’. According to Russo et al., this role “placed museums as provider of both authoritative and authentic knowledge” (2006, p. 2). However, a shift in the 1980s changed the role and operation of museums; management began to focus more on entrepreneurial values, such as marketing, rather than the traditional function of museums (Bieldt, 2012, p. 2). These changes took place in Europe as well as in several other places around the world. Bieldt describes and problematizes this shift in museum culture in New Zealand, with a specific focus on the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. She writes;

“Where the ‘old’ museum had ‘display’ and the ‘museum visitor’, the new entrepreneurial museum has the ‘museum experience’ and the ‘museum consumer’” (2012, p. 3).

This shift meant that there was an increased attention to the visitor’s immersed experience, and to economic activity embedded in the museum, such as cafes and shops. Bieldt bases her argument around Jennifer Rowley’s concept of “the total customer experience”, which is an approach focused on measuring museums visitor satisfaction from the moment the visitor approaches the museum (Rowley, 1999, p. 303). Alongside this shift towards a more

entrepreneurial museum, the concept of ‘New Museology’ developed. According to McCall and Gray, ‘New Museology’ developed as a reaction against traditional museology, which was perceived as top-down, old fashioned and elitist (2014, p. 20). Since museums often received public funding, their perceived mismanagement was considered a wasteful use of money (Ibid.), and resulted in a call for ‘New Museology’ museums which were socially relevant and involved with the public.

Furthermore, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel describe how this shift placed museums in the political field, as democratic institutions, and in this position museums became linked with ideas of participation and cultural citizenship (2018). They argue that as a result, “the democratic museum is perceived as socially relevant: as an inclusive museum across all dimensions of museum practice, from education and exhibitions to collecting and documentation” (ibid., p. 4). As such, ‘New Museology’ depends on engagement with visitors, and ongoing involvement with the public. In contrast, museums which disregard public opinion and allow no influence on its activities may become irrelevant.

Although the ideals of ‘New Museology’ appear to have changed how museums operate, a study by McCall and Gray found that while the concept “has been a useful tool for museum workers,” it has had “less practical effect” than anticipated (2014, p. 31). They explain that this is due to several outside factors beyond the museums’ control (ibid). This may for example include funding constraints, which halt the implementation of certain changes. Again, the importance of a cohesive communications strategy, pointed out by Padilla-Meléndez and del Águila-Obra, can determine how successful the museum will be in engaging the public (2013).

The ideals of ‘New Museology’ and theories related to museums as democratic institutions are useful when considering the museums’ duty to engage the public, as well as their position of authority. These theories will help to evaluate how museums engage the public, and if they do so according to the ideals of ‘New Museology’. These theories will also relate to the different engagement modes used by the museums on Instagram, and will inform an evaluation of these engagement modes in relation to the museums’ role in society.

3.2 - Web technologies and Multivocality

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel stress that museums must decide between a model which either engages the public, or disregard their involvement (2018, p. 4). Drawing on ideas from Tatsi (2013), they discuss a scale of museum communication, from monovocal to multivocal, where at the multivocal end of the spectrum the museum involves the public and representation is based on several different voices (Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt & Runnel, 2018, p. 4-5).

Multivocality may be achieved through the use of social media and other web technologies, since such platforms can act as ‘forums’ where the public voice their opinions and discuss issues. Dudareva explores the potential of web technologies in relation to cultural production and interactions between consumers and companies as well as museums, in particular through the “facilitation of community creation” (2014, p. 43). Padilla-Meléndez and del Águila-Obra also point out the potentials for visitors to contribute to the production of the cultural service that the museum offers, and that this can involve “a worldwide network of potential visitors” (2013, p. 892). In this way, web technologies and social media has the potential to enhance a museum’s multivocality and involvement with the public. Therefore, such tools appear to be a natural component of a democratic institution, as discussed by Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel (2018).

However, the mere availability of platforms to facilitate discussion and engagement is not enough. It is crucial to look at how they are used, and if they are used to their full potential. Jenkins argues that while companies and institutions have digitised their communications with the public, there has been a lot of focus on the issue of digital access, rather than the

“opportunities to participate and to develop the cultural competencies and social skills needed for full involvement” (Jenkins et al., 2009, p. 4). While museums have been quick to move to social media communications, this does not necessarily mean greater participation or engagement with the public. The theories relating to multivocality will assist in evaluating whether Instagram is used by museums to invite discussion and input from their audience.

3.3 - What is Participation?

The concept of participation developed internationally alongside the emergence of ‘New

Museology’, and became prevalent across different disciplines (Harder, Burford & Hoover, 2013, p. 41). However, participation can take several forms, and the concept has been adopted to refer to a variety of different activities. As a result, there is some confusion regarding its meaning. For this reason, the concept of participation will now be explored in more depth. There are many different definitions and theories linked with participation, and no one definition of what participation constitutes. Ekman and Amnå point out that the term has been used to refer to both ‘manifest’ political participation, as well as what they refer to as the more ‘latent’ type of civic engagement (Ekman & Amnå, 2012, p. 283). Political participation has been discussed extensively in recent years, which some argue is due to concerns that public trust and engagement with political processes is declining (ibid.). Others disagree, and argue that a scepticism towards established political systems is not the same as a lack of engagement (ibid). An article by Harder, Burford and Hoover is particularly useful when describing the plasticity of the term participation, and for defining its use (2013). They set out to clarify the concept with the use of three dimensions; depth, breadth and scope, and they argue that these dimensions can be evaluated on a scale. Depth refers “to the extent of control over decision-making by the

stakeholders” (ibid., p. 44), which will indicate the various power relations of actors engaged in some form of participation. The depth-scale begins with ‘denigration’ at Level -1, which

effectively represents non-participation, and moves up the scale to “neglect (Level 0), acknowledgement/‘learning about’ (Level 1), engagement/‘learning from’

(Level 2), interculturality/‘learning together’ (Level 3), and full partnership/‘learning as one’ (Level 4)” (ibid.). The breadth-dimension, on the other hand, “refers to the diversity of

stakeholders invited to participate,” while the dimension of scope is used to clarify the different levels of decision-making which stakeholders may participate in (Ibid.). This framework shows that participation can take place at different stages and at varying levels. Using a spectrum to describe participation facilitates conversations regarding how the participation took place, and how it influenced the final product or process.

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel believe that the concept of participation, and the closely linked idea of interactivity, is too narrow for their application of the term (2018, p. 3). Similarly to Lotina and Lepik, they adopt the term ‘engagement’ instead. Lotina and Lepik define social media engagement as interaction between digital communities and organisations, which is facilitated by SNS (2015, p. 124). This definition suits the study in this thesis as well, since it is not the participation or interactivity between museums and their audience which will be studied in this case, but the attempt to engage with audiences on social media. Therefore the term engagement will be used to refer to the study and results described on the following pages. Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel argue that “the term engagement permits a whole repertoire of activities” (2018, p. 3-4), which is useful when considering the research in this thesis.

Nevertheless, Harder, Burford and Hoover’s scale will be used to determine the type of

engagement the museum’s are encouraging, and the term ‘participation’ will be used to discuss the theories linked with engaging museum visitors.

This thesis is specifically focused on how online forums are used by museums to encourage engagement with their followers. In that sense, according to Harder, Burford and Hoover’s scale, the participation breadth is exclusively focused on the museums’ Instagram audience. Since this thesis looks at engagement from a museums perspective, the research is based on whether museums invite their followers to engage online, and if so, how. By using Lotina’s categories we can classify the types of posts used to engage, but follower’s responses will not be evaluated. Therefore, it is the invitations which encourage audience engagement which is being evaluated, not whether the studied posts actually lead to interaction and participation with the audience. Therefore, the scope of participation will not be studied. However, the depth-scale relates to the type of engagement museums try to achieve with their posts. At times, the

intention may be to learn from their audience, by inviting feedback. In other instances, audience members may be encouraged to collaborate with the museum, and in such cases

participation-depth may reach level 3, as museum and audience members are learning together. Thus, the level of engagement will be evaluated, with the use of examples, in the presentation of results.

3.4 - Citizenship, Participation and Deliberative Democracy

The popularity of the concept of participation may be due to its link with democracy, and the increasing number of people demanding influence over decision-making which will affect their lives and the communities they live in (Harder, Burford & Hoover, 2013, p. 41). Participation has been described, in relation to sustainable development, “as a core ideal, both as a human rights issue and as a means of increasing the efficacy of interventions” (ibid.). This reflects the idea that the public’s participation is an integral part of a society’s development, and that when the public is involved in decision making, results are assimilated more effectively.

Theories of democracy are also frequently discussed in relation to participation, since such theories often place communication among citizens at the core of democratic activity (Dahlgren, 2002, p. 5). The ideas of civic discussion and deliberative democracy have been explored by Dahlgren (2002; 2006) as concepts for theorising citizenship. He argues that the public will develop and connect with each other through participation (2006, p. 269).

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel have applied this theory to interaction between museums and their visitors, where they “treat museums as cultural institutions central to democratic society, with potential to advance cultural citizenship through participation and dialogue with museum audiences” (2018, p. 2). As such, participation is considered an integral part of cultural citizenship, allowing individuals to take part and represent themselves.

3.4.1 - The Issue of Equality

Yet, Dahlgren criticizes the concept of deliberative democracy, since he argues that while the concept is based on ideals of equality and all individuals equal opportunity to participate, this is rarely the case due to the power relations and varying degrees of cultural capital between actors (2006, p. 277). This can be applied to online participation as well, and while Padilla-Meléndez and del Águila-Obra point out that digital technologies can increase audience reach and create new opportunities to engage with customers (2013, p. 893), it is important to consider that everyone does not have the opportunity to access such technologies. Those that do not have the knowledge or means to use these tools cannot engage in online participation. Therefore, while democratic activity may occur online, it is not open to all. Differences in class,

geographical location and economic security play a role here. The nature of what is discussed may also create barriers for some, which, according to Dahlgren, “undercuts the universalist ideal” (2006, p. 281).

3.4.2 - The Issue of Representation

However, according to Jenkins et al., there are several other potential benefits from civic engagement and participation worth considering, such as; “the diversification of cultural

expression, the development of skills valued in the modern workplace, and a more empowered conception of citizenship” (2009, p. 3). Rather than the top-down approach of traditional

oneself and one's culture. Social media are platforms which facilitates self-publication, and allows users a chance to represent themselves in some form. As raised by Lotina, social media platforms have changed the way that stakeholders interact, as well as communications between museums and other public institutions and their audiences, which allows institution access to cultural expertise in the community, and provides individuals with the means to voice their opinions (2014, p. 282).

Theories of participation and democracy often mention the idea of voice. In fact, according to Dahlgren, “talk among citizens is seen as fundamental to - and an expression of - their participation” (2002, p. 6). Since social media facilitates communication among and between people and organisations across geographical locations, it has become a forum for such

participation. The SNS also provide museums with the ability to engage the public in discussion, and to collaborate online.

3.4.3 - The Issue of Authority and Authenticity

While this may be an ideal view of a public institution, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel also point out that “to reject the view of the museum as authoritative institution is not easy, and some museums are slow to recognise the value of seeing audiences as active cultural participants” (2018, p. 2). Again, this relates to the uneven playing field of cultural capital, where museums often hold a position of authority, even when inviting others to speak.

Rejecting the museum’s knowledge about cultural content is not always easy, or desireable. As Russo et al. point out, “in the social media environment, one of the challenges for the museum is to ensure that the veracity of information surrounding cultural content is not abandoned” (2006, p. 6). However, museums must balance their position of authority with authenticity, ensuring that their information is correct and that they engage the public and value their input. If so, Russo et al. are hopeful that social media may serve to “extend this authenticity by enabling the museum to maintain a cultural dialogue with its audiences in real time” (ibid., p. 2). Yet Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel argue that it is crucial that the museum in willing to listen to the public’s input if such engagement is to be possible (2018, p. 13).

When it comes to SNS, having a platform to communicate is not the same as using it for democratic engagement. Although there is a potential for increased collaboration and

discussion, organisations and companies may simply use SNS as a marketing tool, and as a method to reach the expanding audiences who spend their time there. Finally, as Lotina points out, “a shortage of face-to-face contact makes it easier for both communication partners

(organisation and participants) to withdraw” (2014, p. 282-283). Since online interaction on SNS is often brief it is easy for either party to discontinue engagement at any time, while it may not be as easy to dismiss or cancel a physical meeting.

Despite the limitations discussed above, some argue that museums have a duty to encourage participation with the public. Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel consider museums

“responsible for creating opportunities for democratic and participatory culture,” because of their role as public institutions (2018, p. 2). They argue that the social responsibilities of museums are central in today’s society, in particular with regards to “being included in or excluded from the practices of cultural representation and cultural heritage” (ibid.). Black has also explored the responsibility of museums to engage their audience in current issues and debates (2010, p. 129). He argues that museums, as public institutions, should empower and encourage individuals and communities to participate, engage with their displays and contribute to their content (ibid.). Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel takes the argument one step further, and suggest that a truly collaborative and democratic museum should let participants’ agenda guide them to “unexplored territories of mutual gain” (2018, p. 13).

Similarly to Black, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt and Runnel, Dudareva found that engagement with the visitor is a main museums priority (Dudareva, 2014). Yet, Dudareva suggests that

maintaining engagement outside of the museum experience is a challenge for museums (ibid., p. 38). Perhaps, online technologies, or SNS, could facilitate such engagement. Black argues for the potential of technology as a tool for networking and promoting engagement among audience members, but it is not clear whether he considers new technology a place where public engagement can occur, as well as a means for promoting it. The functions of networking and promoting activities are stressed by Black, but he only alludes to further possibilities for participation through new technology (2010, p. 135).

The theories and concepts discussed in this section become relevant when considering the study and results in this thesis. The theories of citizenship, participation and deliberative democracy will assist in considering the museum’s role in society, and whether their use of Instagram is in line with expectations of democratic institutions. On the one hand we have the desire and ambition to engage the audience in discussions and democratic activity, on the other we have the museum culture which is in a position of power, driven by economic growth and satisfied customers, rather than challenged visitors. Can these conditions be integrated? This study will look at how museums use their social media accounts, based on the engagement they offer with each post, and thereby discuss the potential and use of social media by cultural institutions.

4. Previous Research

This thesis is based on previous research undertaken by Lotina and Lepik (2015). Therefore, their study will be discussed and explored in more detail, both in the final part of this section and in the methodology section. In addition to this, a separate study by Lotina (2014), as well as a few other articles will be mentioned briefly, since they help explain the relationship between the concept of participation, social media and museums.

4.1 - Lack of Funding and Strategy

Lotinas 2014 study focused on Latvian museums professionals, and examined their attitudes towards online channels to encourage participation. The study was based on interviews with museum staff, and analysed the motivations and difficulties which influenced their use of social media. The study found that SNS were not used for participatory purposes to a particularly large extent by the researched museums (Lotina, 2014, p. 286). In fact, some of the interviewees believed that forums for communication between professionals were better suited for discussion, rather than the museums’ own websites and SNS (ibid.).

These findings may indicate a lack of prioritisation of webb technologies within museums. Both Lotina’s study (2014) as well as a report presented by Johnson & Witchey, focused on the impact of new technologies in the museum environment, found that the limited availability of funds was a critical issue with regards to museums’ use of SNS (2011, p. 39). Johnson & Witchey’s report also mention a lack of training of museum staff, resulting in difficulties when dealing with new technological opportunities (ibid.). This could be due to limited resources, and may be an additional factor leading to low use of SNS .

The limited use of SNS for participation may also be due to attitudes among staff members. Lotina’s findings suggested several aspects which influenced the museums’ use of SNS, such as the interviewees’ opinions regarding the usefulness of such sites (2014, p 287). This included concerns regarding “the credibility of the SNS; the amount of time museum professionals are ready to spend on communication; the characteristics of the main museum target groups and the usage of SNS by these audiences; and the scepticism about the participatory potential of users” (ibid). Again, these results suggest that museums suffer from a limited amount of resources to spend on new technology, and that they struggle to keep up with changing audience behaviour through online technologies.

These challenges highlight the lack of specific knowledge and implementation of a well defined strategy in museum management, which both Johnson & Witchey’s report (2011, p. 39) and Padilla-Meléndez and del Águila-Obra’s study (2013, p. 897) found to be crucial for museums. A comprehensive strategy which reflects the goals and values of the institution in question is critical if museums wish to extend their reach online.

Keeping up with ever changing SNS technology, public behaviour and use of SNS appears to challenge both museums and their staff. It is relevant to take these findings into consideration with regards to both Lotina’s study, and the study which will be presented in this thesis. While analysing how museums use SNS will provide insight into the ambition behind museum

engagement online, these findings show why museums may be limited in their use of SNS, and why they choose to use it in certain ways. Previous research is relevant to keep in mind when considering that all museums may not have the knowledge to use SNS, or may not be inclined to due to their perception of its usefulness. This may influence their strategy and use of SNS. If such views do indeed vary among the wider community of museum professionals, their choices

regarding use of SNS may be evident in the results of the study presented in this thesis. We will return to these findings in the concluding discussion of the results of this thesis.

4.2 - Museums in a Position of Authority

Even when museums implement participatory media, the results may be problematic. Jensen (2013) is one of the few articles which discuss museums’ use of Instagram as well as their participatory culture with visitors. Jensen looked at a number of Danish museums, and how they choose to use their social media accounts. The study investigated to what extent audiences were allowed to ‘take the lead’ on museums’ SNS, but found that participation was always on the museums’ terms. According to Jensen, “the institution does not loose authority in the process” (2013, p. 314). This is a significant finding, since it indicates that although the

institutions studied by Jensen where encouraging participation on their Instagram accounts, that participation was structured in a way which was limiting for participants. If the aim in inviting the public to participate is to encourage a democratic space, such limits must be discussed as a challenge to democratic participation.

A separate study by Noy (2017) also suggests that while museums invite discussion, the participation may be structured so that the museum remains in a position of authority. Noy’s discourse analysis study took place in The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia, US in 2017, and was based on in-situ participation, rather than on social media. Yet, her research is relevant to platforms such as Instagram, as well as to public discourse, since it explores the museum’s use of a text based forum for discussion on one of the museum walls. Visitors were invited to contribute with their views, and respond to the museum and each other.

Noy’s study explored the idea of the ‘new museum’, which is characterised by the shift towards new museology, where traditional museum formats changed from the “top-down narratives anchored in collections of authentic artifacts, to immersive, experiential, and ‘visitor-friendly’ post-modern media environments” (Noy, 2017, p. 40). The article examines the use of post-its in an installation called the (CIF) Contemporary Issues Forum, which was used to encourage discussion and debate amongst visitors. The installation centered around questions such as ‘‘Is it ever appropriate for the US Government to censor speech?”, and visitors were asked to contribute to the discussion, in writing, by using supplied post-its with the title of ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘Um..’ (ibid., p 41). Noy points out that the questions asked where always structured to elicit yes/no responses, and that the museum, by choosing which questions to ask, “marks what is worthy of public debate (and what isn’t) and how it is to be discursively articulated and

physically displayed” (ibid.). In this sense, the museum had welcomed visitors to express their opinions on certain issues, but at the same time they ‘curate’ the discussion, by articulating questions in a certain manner, and by inviting certain responses. This is relevant to keep in mind when looking at the types of engagement museums encourage through their social media accounts as well. Is engagement only encourage on the museums’ terms?

4.3 - Lotina and Lepik’s study

Lotina and Lepik’s study, which this thesis is based on, analysed the engagement modes encouraged by museums through their social media accounts. The study, which was published in 2015, is based on observations and analysis of the Facebook pages pertaining to four museums, of which two were based in Latvia and two in Estonia. While the previous study by Lotina, based on interviews with museum staff, found that museums often balance the

marketing and participation potentials of SNS (2014, p 286), this study aimed to discover how museums in fact used their online sites to engage with the public.

Lotina and Lepik developed an analytical grid, and proceeded to classify the museums’ Facebook posts based on seven separate categories. The analytical grid was based on “two main components: a list of audience engagement modes that embraces online museum activities, and adaptation of the model of sign functions” (Lotina & Lepik, 2015, p. 124). Thus, the analysis was centered around the different types of engagement that the museums seek to achieve with the help of their online channels. By looking at sign functions, Lotina and Lepik argue that they are able to “convey the semiotic approach to the sign’s functions in the social media context by analysing the different aspects of the ‘message’ as it relates to modes of engagement” (ibid.). By taking this approach, they use a method of close reading which looks at the meaning behind the use of certain phrases. For example, when looking at a Facebook posts by a museum, a phrase such as “Welcome to our exhibition opening at 6pm!” can be

categorised as ‘Marketing’, since the phrase is used to promote an event at the museum. The categories used by Lotina and Lepik will be adapted and implemented in this study. Therefore, the definitions and boundaries of the categories, as well as the process of analysis, will be further developed and defined in the methodology section of this thesis.

Lotina and Lepik found that posts categorised as ‘Marketing’ were the most common type of engagement mode when analysing museum’s Facebook posts (ibid., p. 132). ‘Informing’-posts were also a frequent occurrence, while posts encouraging ‘Collaboration’ or aiming to consult their audience were not particularly common (ibid.). These results suggest that engagement on social media is rarely encouraged by museums, and that SNS are rather being used for their marketing potential.

Lotina and Lepik’s study is particularly relevant to this thesis, since their analysis centers around museums’ use of social media to engage with audiences. Although their study is based on Facebook, the analytical grid and categories for defining engagement are well suited to analysis of Instagram, which this thesis will focus on. Lotina and Lepik’s study is based on the

engagement with audiences from the museums perspective, therefore focusing exclusively on the content created by museums. As such, the research which will be described and presented on the following pages of this text hopes to expand on their study, and the research design was therefore also based on the perspective of museums.

The other articles explored in this section suggest that museums rarely use SNS for its participatory potential, and this could be due to issues such as; lack of funding, training and strategy, as well as attitudes towards SNS for engagement with the audience. Even when attempts are made to invite engagement, the engagement is often structured in such a way that the museum retains its position of authority. Although Lotina’s 2014 study found that museums balanced the participatory and marketing potentials of SNS, the subsequent study by Lotina and Lepik suggested that marketing was in fact much more common. We will return to this issue in the concluding discussion of this thesis.

5. Research Aim and Questions

The aim of this thesis is to discover how museums use their Instagram accounts, with a

particular focus on how museums engage with the public and provide invitations to engage. The first research question is therefore phrased as follows; How do museums in Sweden and New Zealand use their Instagram accounts to engage with the public? The research has been designed to answer this specific question, and will therefore focus on material produced by the museums. A second question will aim to focus this research, by asking; What type of

engagement modes do museums in Sweden and New Zealand use to connect with their audiences? Finally, to bring in the comparative aspect of the study, the third question asks; Do Museums in Sweden and New Zealand, and different types of museums, use these

engagement modes differently?

6. Methodology

The study is based on an epistemological research perspective where the researcher is positioned as an outsider and an observer. Through this perspective, the museum material is observed and interpreted into trends in museum communication with the public. These trends are analysed in light of the principles of new museology.

The approach of data collection and categorisation according to Lotina and Lepik’s model was chosen because of its specific attention to museum-created content online. In addition to this, their method allows the researcher to categorise posts according to engagement modes, which results in a clear overview of different types of communication from the museums. This method is particularly suitable in relation to the research questions above, since it looks specifically at how social media is used by museums in order to engage and communicate with their

audiences online. Additionally, method is suitable since it allows for comparisons of data from different museums.

The research design does not include any attention to audience activity online; instead the study looks exclusively at the perspective of the museum, and museum created content. Whilst

research regarding the audience interaction and engagement with the museums would have provided another perspective on this type of online engagement, this was not within the scope

of this study. Audience engagement with museums on Instagram would, however, be an interesting and complementary addition for future studies.

6.1 - Data Collection and Sample

The data sample consists exclusively of museum posts on Instagram. Data consisted of

observations from museums who actively used Instagram to post during the time span of 1st of January until the 31st of March 2018. The time span was selected to cover a significant amount of time, which could include a variation of posts, while also keeping the amount of content collected for analysis within the scope of this study. 20 museums from each country were selected for analysis, in order to gather a large enough sample to detect trends or variations in museum behaviour on Instagram. All posts by these museums during the selected time span were included in the study. Museums of varying size, location and themes were selected with the intention of gathering a broad sample, which could include a number of varying engagement modes. Therefore, both rural and urban museums have been included. The selection includes historic and ethnographic museums, as well as museums with an art and science focus. By looking at several types of museums across two countries, results may indicate differences in behaviour which could be a source for further study. But if results appear similar in both countries and when comparing different types of museums, then it is possible to argue for a trend in museum behaviour.

In order to best respond to the research questions and aim of this study the posts made by museums have been collected, while comments, likes and other types of activity have not been included in the data collection and have not been studied or counted. A list of all studied

museums, detailing their Instagram account names, followers and number of posts during the selected time period can be found below.

6.1.1 - Museum Selection

Museum name: Theme: Instagram name:

Followers

(9 May, 2018): Total posts: The Nordic Museum History/ Ethnography @nordiskamuseet 20.8 k 44

Skansen History/ Ethnography @skansen 13.5 k 27

The Vasa Museum History/ Ethnography @vasamuseet 7681 54 Gotlands Museum History (and art) @gotlandsmuseum 1505 43 Bohusläns Museum History (and art) @bohuslans_museum 1011 26

Kulturen History (and art) @kulturenilund 1562 75

Malmö Museums History @malmomuseer 2358 58

Moderna Museet

Moderna Museet

Malmö Art @modernamuseetmalmo 7333 6

Gothenburg

Museum of Art Art @goteborgskonstmuseum 5947 23

Rackstad Museum Art @rackstadmuseet 395 19

The Art Museum in

Skövde Art @konstmuseet 1021 32

Universeum Science @universeum 4171 12

Swedish National Museum of Science

& Technology Science @tekniskamuseet 5862 44

Grenna Museum History @grennamuseum 631 47

Swedish Air Force Museum

History/

Science @flygvapenmuseum 1020 11

Junibacken History @junibacken_stockholm 3767 59

Gothenburg Museum of Natural

History Science / History @naturhistoriska 1039 26

Internet Museum Science/ History @internetmuseum 2190 14 Nobel Museum Science/ History @nobelmuseum 4137 7

Table 1. Swedish Museum Selection.

Museum name: Theme: Instagram name:

Number of followers

(9 May, 2018): Total posts: Te Papa

History/Ethnography/

Science @te_papa 11.6 k 39

Auckland War Memorial

Museum History/Science @aucklandmuseum 13.5 k 73

Otago Museum Science/History @otagomuseum 1119 49

Yaldhurst

Museum History/Science @yaldhurst_museum 80 5

Waikato Museum

History/Ethnography/

Art @waikatomuseum 1333 62

Tairawhiti

Museum History/Ethnography @tairawhiti_museum 598 21

Museum /Art City Gallery

Wellington Art @citygallerywellington 8057 27

Gus Fisher

gallery Art @gusfishergallery 1483 17

NZ Portrait

Gallery Art @nzportraitgallery 1052 14

The Dowse Art

Museum Art @thedowse 4859 44

Forrester

Gallery Art @forrestergallery 248 10

DPAG Art @d.p.a.g 1128 4

COCA Art @coco.chch 2286 7

Christchurch Art

Gallery Art @chchartgallery 7250 42

Auckland Art

Gallery Art @aucklandartgallery 15.1 k 35

Tauranga Art

Gallery Art @taurangaartgallery 2410 28

MOTAT History/Science @motatnz 1355 35

Air Force

Museum History/Science @airforcemuseumnz 655 21

NZ Maritime

Museum History/Science @nzmaritimemuseum 5362 27

Table 2. New Zealand Museum Selection.

The sample was not downloaded. Instead is was observed and analysed simultaneously, and comprehensive notes were kept for each museum. Each museum’s Instagram account was found on the Instagram site, and posts that were published during the selected time-span were then analysed and immediately placed in a category. In this sense, the researcher's role did not affect the sample, since the data observation and analysis took place retrospectively, and the observation was ‘natural’, since the environment was not controlled by the researcher (Collins, 2010, p. 132).

6.2 - Data Analysis

The data analysis consisted of both image and text analysis combined. Each post was analysed with the use of close reading and labeling according to Lotina and Lepik’s categories. The engagement mode of each post was determined based on both the image and text in

Lotina and Lepik’s categories for analysis of Instagram content. The pilot study included a sample of six museums (three from Sweden and three from New Zealand) and analysed all of their Instagram posts over the course of the selected time-span.

In order to determine the applicable category for each post, Lotina and Lepik used an adapted version of Roman Jakobson’s (1960) classic model for determining language functions. The later, adapted model was developed by Thwaites, Davis and Mules (2002). The model analyses posts based on “the following message functions: (1) content; (2) code; (3) form; (4) addresser; (5) contact; (6) addressee; (7) context” (Lotina & Lepik, 2015, p. 130). By looking at these functions, it is possible to determine which of the engagement categories the message adheres to. Lotina and Lepik applied this model to museum posts, detailing content, code and context. Their table was very useful when categorising Instagram posts for the purposes of this thesis, therefore it has been included as Table 3.

The Image 1. will assist in illustrating the look of a Instagram post (from a desktop device), and the elements which will be analysed in order to categorise the engagement mode of each post. All posts must fit into the format above. The left side of the post is dominated by one or more images, and may sometimes include moving images. The right side of the post always contains the account name and profile picture at the top. The blue text reading ‘Follow’ allows the reader to click and thereby ‘follow’ or ‘subscribe’ to posts by the user. The subheading allows the user to expand their name, include symbols or additional information. The caption follows underneath this header, always beginning with the account name in bold. This particular caption includes both Swedish and English text. The caption can contain ‘hashtags’ which groups posts together with other posts containing the same hashtag, which makes the post searchable. The above example contains the hashtags #vasamuseet and #thevasamuseum. The caption may also contain tags beginning with and ‘@’ symbol, followed by an Instagram account name, which will then lead to the tagged account. Comments follow underneath this section, but the comments have been covered by a black rectangle in the examples used in this thesis, since they are not being studied, and in order to keep the identity of commenters private. Below this, the heart and speech bubble symbol allows the reader to ‘like’ and/or comment. At the very bottom of the page the amount of ‘likes’ and the date of publication is displayed, followed by a message urging the reader to log in to like or comment. As mentioned above, comments will not be studied in this thesis. Instead, the captions and images included in posts will form the basis of analysis in order to determine the applicable engagement mode category.

Lotina and Lepik’s table (Table 3) was used to review and determine the engagement mode of posts studied in this thesis. Applied to Image 1 above, the content, code and context was established in the following way:

Content: Along with a photograph of the museum building, the message encourages the reader to visit the museum by supplying information regarding opening hours, thus serving as a news board. This fits with the content related to ‘Marketing’ posts. The message mentions the dark winter, and suggests that a museum visit will lighten up the reader’s day.

Code: The message contains an invitation to visit, along with a photograph of the museum. The message also provokes interest and emotion, by mentioning the darkness outside, and the tempting light and presumed warmth inside the museums. Again, this encourages the reader to visit, and fits with the ‘Marketing’ category.

Context: In this case the context is the museum activities over the weekend, and as such an upcoming event. This also fits with the ‘Marketing’ category.

6.2.1 - Engagement Mode Categories

Informing

This type of engagement mode “refers to strictly educational activities and excludes any

promotional intentions on behalf of the museum, the exhibitions or other products offered by an organisation or stakeholder” (Lotina & Lepik, 2015, p. 129). Thus, posts which are educational but also promotes an activity by the museum/stakeholder is categorised as ‘marketing’ rather than ‘informing’. In Lotina and Lepik’s research, three sub-categories where identified as pertaining to ‘informing’. These include (1) educative content regarding objects/activities in the museum, (2) information “related to the broader context within which the museum works,” and (3) other educational facts (ibid., p. 131).

Marketing

This category refers to any type of promotion of museum events or activities, and include invitations to visit. Marketing may also refer to posts that encourage participation in a related event, or promoting a stakeholder. This may, for example, promote the museum cafe or shop. As Lotina and Lepik points out, such posts may “enchain users’ attention by adding playful activities like quizzes and other type of game with or without prizes” (ibid., p. 129). A marketing post may include a large amount of information, for example regarding an artist which the museum is featuring in an exhibition. However, if the post mentions the ongoing exhibition, of encourages the reader to visit, the post will be categorised as ‘marketing’ rather than ‘informing’. This category includes information relating to access, and other functional information such as opening hours.

Consulting

This category refers to posts which encourage feedback or expression of opinion from followers. Such posts may raise issues for debate, or may ask followers to raise their own issues. The purpose of this category is to identify posts that “invite collective expertise from the community” (ibid., p. 130). When analysing posts that ask questions, it has become apparent that not all such posts fit within the ‘Consulting’ category. Consulting must allow the museum to learn something new from the audience, or to gain their perspective or view on something. For

example, although quizzes ask questions of the audience, they do not provide the museum with information they did not already know. Therefore, posts which contain quizzes have not been labelled ‘Consulting’. Instead, quizzes can be labeled ‘Marketing’ due to their ability to draw the user’s attention, or, in some instances, quizzes may be categorised as ‘Information’, since the post provides answers that inform the audience.

Collaboration

Collaboration posts “invite users to participate in social processes, to act as volunteers, fundraisers, donors, etc.” (ibid., p. 130). These type of posts encourage followers to contribute something, and to work together with the museum to create something new. Lotina and Lepik

further differentiate between the categories of ‘consulting’ and ‘collaboration’ by stating that while ‘consultation’ invites followers to contribute with their opinions, ‘collaboration’ invites them to act in some way (ibid., p. 134). The engagement can be temporary as well as continuous. Connecting with Stakeholders and Professionals

These posts constitute two separate categories in Lotina and Lepik’s article. Yet, based of the results of the pilot study, it appears appropriate to combine these into one category for the purposes of this study. In Lotina and Lepik’s article, posts applicable to the ‘Connection with Stakeholders’ category “emphasises the museum’s role as stakeholder in the network of related organisations and includes reposts to news posted by others” (ibid., p. 130). Essentially, the category refers to posts which place the museum in relation to other organisations, companies or public individuals in a favorable manner. On the other hand, the ‘Connecting with

Professionals’ category “refers to the users who already have some kind of professional knowledge in the specific field of museum” (ibid.). Lotina and Lepik go on to explain that this category describes posts which inform followers regarding scientific events, and that they “show that the museum organisation is part of a professional network, it communicates with and is trusted by colleagues” (ibid.). While the distinction between the two categories may serve to distinguish posts on Facebook, the network functions on Instagram are different. While Facebook allows the user to join groups and post content on other individuals profiles,

Instagram follows a simpler model, which is based on images posted by the user, and the ability to comment on other user’s posts. Therefore, when a museum publishes a post on Instagram it will reach all of its followers, not a select group. For example, there is no function for creating groups or events which will only reach professionals.

Based on the pilot study, it became apparent that museums sometimes used Instagram to post messages related to events outside of the museum, and at times ‘tag’ other organisations or artists. Museums may also post regarding a conference they attended, or an award they have won. These posts all appear to stress the museums role in a network, and shows that the organisation is trusted by others. Therefore it was determined that these two categories will be treated as one, for the purposes of this study. Examples will be provided, in the results section. Connecting with Audiences

The term ‘Connecting with Participants’ (used by Lotina and Lepik) was changes to ‘Connecting with Audiences’, since this was more applicable to this study. The actual participation was not studied, therefore the change of category name reflects that it is the effort to connect with the audience which is being studied. This category “refers to the posts that stress the duration of the museum’s relationship with a community” (ibid., p. 130). This may for example consist of

messages with references to history or shared memories, such as historic images of the museum and its visitors. It may also consist of ‘behind-the-scenes’ images, or other posts that show the processes that take place in the museum while showing a “less formal type of organisation” (ibid.).

Images

This category was not present in Lotina and Lepik’s research, but based on the analysis of the pilot study it has been included here. The category refers to posts that mainly consist of an image, with very little information or context. Based on observation, museums occasionally post images of, for example, the weather outside of the museum. These type of posts may also include short messages, but do not fit with any of the previous categories. The intention behind these posts may simply be to remind followers of the museum’s presence, and for that reason the category could perhaps be considered marketing. However, these posts include no

promotion or invitation to visit the museums or a stakeholder. The need for this category may indicate a slight differences between Instagram and Facebook, and therefore it was included in the analysis section. The category will be discussed further in the results section.

6.2.2 - Application of the Categories

After establishing that the categories were applicable to museum posts on Instagram, the analysis proceeded to the second stage; applying the slightly adapted categories to all the museum posts with the use of close reading. By using the categories above, the analysis employed the method of open coding, which is a comparative method (Collins, 2010, p.150). As described by Collins, open coding asks questions of the data, and works to group similar

incidents together (ibid.). In this case the coding took place with the aid of the engagement mode categories described above, as well as by looking at the content, code and context identifiers described in Table 3.

Each museum’s instagram page was found on the Instagram platform and the posts for the selected time period were reviewed one by one, and allocated into to the above categories. A record was kept for each museum. The record reflects the total number of posts, as well as the number of posts which qualify into each of the categories. Posts which were a particularly strong example of a certain category were marked down with a reference to the date of publication. Some posts fit into several categories, but each post was only categorised as belonging to one category. When a post contained several modes of engagement, the predominant engagement mode was identified and the post was allocated to the appropriate category. Thus, there is no overlap in the presentation of results. Posts containing both marketing and information were always categorised as ‘Marketing’, since Lotina and Lepik established that educational content “may also be a part of promotion because posting marketing information does not exclude delivering educational content,” (2015, p. 129). As such, some of the posts labelled ‘Marketing’ contain information (such as educational content), but none of the posts categorised as

‘Informing’ contain marketing.

The Image 2. will be used to illustrate how a post can contain several engagement modes. The caption refers to a short video posted by the museum, where the curator describes the life and work of a local Maori woman. Since the video provides the viewer with educational information

regarding local cultural customs as well as details of an important figure’s life, the post was categorised as ‘Informing’. However, the post also places emphasis on the museum’s role in collecting, preserving and disseminating such information. Therefore the post connected the museum with the local Maori community, and thus contain the engagement mode ‘Connecting with Audiences’. While such connections are made, it was established that the main purpose of

Image 2. Waikato Museum’s Instagram account, March 8th 2018.

the post was to provide educational information. As such, the post was only categorised as ‘Informing’.

After categorising all the posts, the data was entered into a spreadsheet, which allowed for comparisons between the different countries, museums and categories. This part of the analysis employs selective coding, which is able to detect phenomena and trends in the data (Collins, 2010, p. 152). The comparisons, trends and phenomena will be presented in the ‘Results’ section, and will be discussed further in the ‘Discussion’ section.

Finally, when considering the data analysis, it is relevant to point out that the research was undertaken by one person. This is a methodological limitation related to the analysis, since there was no cross referencing with other researchers when applying the categories to the museum posts. For future work on the subject, it would be advisable to use a group of

researchers for the same set of data, since this would ensure agreement on the application of categories while limiting the risk of bias.