A statistical descriptive analysis on how management consultants’

personal background affects their work

Bachelor’s thesis within Change Management/ Management Consultancy

Author: Ronnie Cau Nicklasson Johan Melinder

Sofie Törner Tutor: Francesco Chirico

Bachelor’s Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Management Consultants Differ

Author: Ronnie Cau Nicklasson, Johan Melinder, and Sofie Törner

Tutor: Francesco Chirico

Date: 2012-05-18

Subject terms: Change, Change Agents, Change Management, Management

Consultants, Change Agent Bias, Problem Identification,

Abstract

Organizations constantly face the challenge of identifying, adopting and implementing necessary changes in order to stay competitive. An option for executing these changes is to contract an external management consultant with experience and expertise in organizational development. Our aim is to find if and how certain demographic variables of management consultants’ background affect how they identify an organizational development problem. This thesis is focused on management consultants within organizational development, and their responses when presented with a laboratory business simulation. There are limited generalization parallels to other consultancy areas and situations beyond the specific area of organizational development.

We conducted a descriptive experimental study with 83 responding management consultants. Participants answered a questionnaire in combination with the presented business simulation, regarding how they identify problems based on their personal background. The data set was compiled statistically and rendered in IBM SPSS. Furthermore the answers were analyzed using multiple regression analysis and single correlation test statistics.

We found that Management consultants showed a preference towards external environment as major contributing factor to the problem(s) at hand. Furthermore we found a positive relation to “Age” and “School”, and negative relation to “Work-life experience”. Consequently, management consultants do differ in their problem identification approach based on their personal background.

With greater understanding of how management consultant differ, clients and supplier of management consulting services can better align consultants with organizational problem(s), in order to generate better synergy effect.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge and thank everyone who contributed

to the success and completion of this Bachelor thesis.

Many thanks to all of those who participated in our survey,

without you our work would never had been completed.

More thanks to friends, colleagues and family who helped us,

with comments, feedback and guidance throughout the process

of making this thesis.

And, a special thank you to our tutor Francesco Chirico for your

patience, guidance and help during this semester.

T able of Contents

1

Introduction ... 6

2

Background ... 8

2.1 Change and Organizational Development and why it Exists ... 8

2.1.1 Change Management ... 9

2.1.2 What is a Change Agent? ... 10

2.2 Management Consultants ... 11

2.2.1 When and Why Do Organizations Use Management Consultants? ... 11

2.2.2 Management Consulting Market Overview ... 12

2.3 Previous Research on how Management Consultants Differ ... 13

2.3.1 Tichy and Nisberg’s Research on Change Agent Bias ... 13

2.3.2 Burke and Bazigos Research on OD Practitioners’ Choice of Theory ... 14

3

Problem Statement and Research Question ... 16

4

Purpose ... 17

5

Definitions ... 18

6

Theoretical Model ... 20

6.1 The Burke-Litwin Casual Model of Organizational Performance and Change ... 20

6.1.1 Transformational and Transactional Dynamics ... 22

7

Hypothesis ... 25

8

Method ... 30

8.1 Research Design ... 30

8.1.1 Data Collection ... 30

8.1.2 Experimental and Descriptive Research Design ... 30

8.1.3 The Time, Scope and Environment ... 31

8.1.4 Quantitative Research ... 31

8.1.5 Survey ... 31

8.1.6 Questionnaire ... 31

8.1.7 Simulation ... 32

8.1.8 Feedback on Business Simulation and Questionnaire ... 34

8.2 Sampling, Sample and Response Rate ... 34

8.3 Use of Hypothesis ... 34

8.4 Multiple Regression ... 35

8.4.1 Correlation Matrix ... 35

8.4.2 Independent and Dependent Variables Explained ... 35

8.4.2.1 Dependent Variables ... 35

8.4.2.2 Independent Variables and Corresponding Dummy Variables ... 36

8.4.3 Reference Points ... 36

8.4.4 Statistical Power ... 37

9

Results and Analysis... 38

9.1 Sample Statistics ... 38

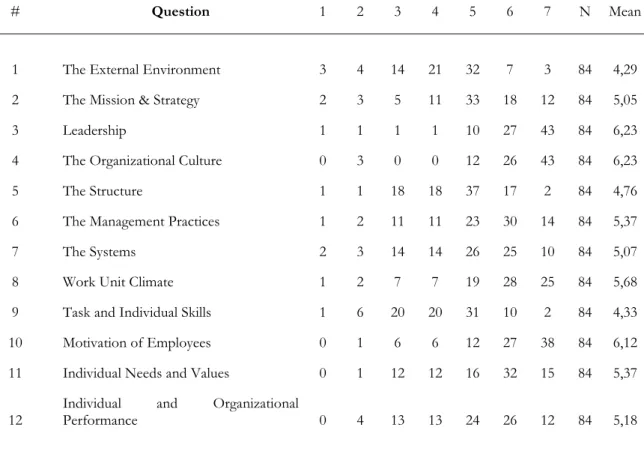

9.2 Data Presentation and Interpretation ... 39

9.2.2 Table for Hypothesis 1a, 1b and 1c ... 41

9.2.3 Hypothesis 1a: “First Impression – All Variables” ... 42

9.2.4 Hypothesis 1b: “Transactional Dynamics – All Variables” ... 43

9.2.5 Hypothesis 1c: “Transformations Dynamics – All Variables” ... 43

9.2.6 Table for Hypothesis 1d ... 44

9.2.7 Hypothesis 1d: “The 12 Dynamics – All Independent Variables” ... 48

9.2.8 Supplementary Data ... 49

9.3 Discussion ... 49

10

Conclusion ... 52

10.1 Purpose and Research Question ... 52

10.2 Contribution ... 52

10.3 Implications for Practice ... 53

10.4 Limitations ... 53

10.4.1Type I and II Error due to High Alpha Level ... 53

10.4.2Sample Limitations ... 53

10.4.3Business Simulation ... 54

10.4.4Swedish Respondents ... 54

10.4.5Demographics and Dummy Variables ... 54

10.5 Further research ... 54

11

Reflections on the Writing Process... 56

List of References ... 57

Appendix

Appendix 1. Questionnaire ... 62Appendix 2. Independent Variables' Corresponding Dummy Variables…...65

Appendix 3. Feedback on Business Simulation and Questionnaire ... 66

Tables and Figures

Table 2-1 Management consultant market overview ... 13

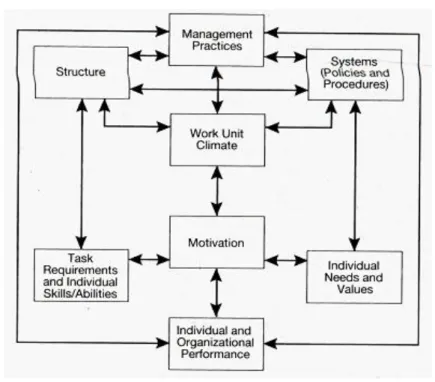

Figure 6-1 Burke-Litwin Model ... 21

Figure 6-2 Transformational Dynamics ... 23

Figure 6-3 Transactional Dynamics ... 24

Figure 8-1 Laboratory Business Simulation ... 33

Table 9-1 Sample Statistics... 38

Table 9-2 Regression Performance for Hypothesis 1a, 1b and 1c ... 41

1

Introduction

“…Winds which vary from warm summer breezes that merely disturb a few papers to hurricanes that cause devastation to structures and operations that require reorientation and rebuilding.”

Senior and Swailer (2010, p.7) envisage the forces that bring change within an organization to the passing variations of our climate. It is necessary to adapt to the volatile organizational climate in today’s society; however perfectly adapting is close to impossible. Even the gentlest breeze may evolve to a roaring hurricane in the same way as a hurricane can abate to dead calm. The concept of change is something that breaks from the ordinary and makes the organization rethink and rebuild. It is important to realize that change happens continuously and dynamically and need specific attention and facilitation. According to Paton and McCalman (2008, p. 9), the key point of change is that it is an ongoing process where planned change is often difficult to achieve. Other authors, such as Kotter (1996) and Romanelli & Tushman (1994) are just a few of many who emphasize the need for change and the many ways on how to initiate change. One thing that these authors have in common is the belief that change should be implemented through people, namely change agents, and through change management.

Change management is recognized within business academia as an effective way to drive an organization forward. It is however crucial to be objective in the process according to Paton and McCalman (2008). Therefore, it is common that organizations use the advice of an external management consultant, which offers an increased objective perspective. A management consultant can be contracted to advise, diagnose, plan or implement strategic actions, which often lead to situations that requires change (Margulies and Raia, 1972). Hence, a management consultant is considered to be a change agent. The specific industry turnover of organizational development management consultancy services in Sweden amounted to 49.6 billion SEK. The largest client of management consultancy services was commercial organizations, representing 85 percent of net sales (Sweden Statistics, 2003). As the statistics show, management consultancy is used and accepted in Sweden as a means of helping Swedish organizations to progress, whether it is by advising in change situations, diagnosing or implementing the change.

Tichy and Nisberg’s (1976) research on how change agents are biased in their work depending on their personality are a perfect example of an earlier study on a similar subject as ours. They claim that management consultants differ in the way they practice their work when exposed to identical situations. Burke and Bazigos (1997) research on change agents and how they prefer different kinds of theoretical models within change management is another.

The aim of this bachelor thesis is to present a descriptive statistical analysis of how management consultants identify a problem differently, with consideration to their different backgrounds. The reason why we decided upon this topic is our common interest in the industry and its interdisciplinary character. Some previous research has been done in this specific subject. Our objective is to see if there are any demographic variables that might be an underlying predictor to what makes management consultants’ work differ. The data for this thesis will be compiled by statistical results and analyzed with a multiple regression analysis method, further explained in the Method section.

To conclude our thesis, we will present a descriptive discussion. The discussion’s aim is to reflect over the interdependencies that can indicate a management consultants’ specific background, and their identification of different problems in a given change situation.

2

Background

In this section, we will present the background and frame of reference to our work. As will be discovered, concepts of change, change management and change agents are all coherent and practiced in the business world today. We would like to enlighten that a management consultant is defined within the academia of change management as a change agent; an external consultant who is contracted for a limited time by an organization in need of help in a change situation. Below we will discuss the concepts of change and change management, management consulting, as well as previous research on the subject of organizational development practitioners (OD practitioners) by Tichy and Nisberg (1976) and Burke and Bazigos (1997). An OD practitioner and a change agent is Tichy and Nisberg and Burke and Bazigos preferred terminology of an organizational development management consultant. In order to not manipulate the authors’ intent we will use their terminology in the text concerning their research. However, to avoid further confusion we will consistently use the definition management consultant in the text compiled by us.

We hope that by discussing the essence of these concepts, a wider knowledge and understanding on the subject and potential issues can be obtained, which will be useful for the understanding of the thesis.

Further explanations of presented definitions and terminology can be found in the section Definitions.

2.1

Change and O rganizational Development and why it

Exists

The importance of change lies in when change is needed and what the impact is. Paton and McCalman (2008) make an effort to identify six major external changes that creates a need for internal change within any organization. Firstly, they acknowledge how enhanced technology and international competition affect the global market. Secondly, how environmental issues has become an influencing variable for governments worldwide. Thirdly, that there is a permanent trend of health awareness amongst all age groups. Fourthly, they recognize a trend in lifestyle changes, and how people view work and leisure time. Fifthly, the changing workplace creates a need for non-traditional employees. Lastly, they identify the increasing need of knowledge assets in order to stay competitive. Moving from status quo and adjusting to external changes can be seen as triggers to internal change but we should not assume that need for internal change is entirely due to external triggers. An additional cause of these external changes is when organizations try to be proactive by anticipating problems in the market or negate the impact of worldwide problems such as recessions.

In contrast, according to Toffler (1970) there are 3 factors that drive change. First, impermanence and transience are both increasingly important features of a modern life because of the accelerating pace, scope and scale of change itself. Change foremost affects people’s lives and relationships with things, places, other people, organizations and ideas. These changes in turn, create a demand of adaptability in order for both individuals and organizations to cope. Increasing focus on technology and innovation is the second factor that drives change. Also, Toffler (1970) argues that diversity is becoming a more important factor that drives change.

Kotter (1996) states that in a globalized economy, sometimes organizations are forced to make dramatic improvements in order to stay competitive and sometimes for merely surviving. The globalized economy creates an environment where opportunities and threats are everywhere and for everyone to explore. Hence, globalization itself is affected by improvements in technology, deeper and wider economic integration between countries and home country markets that matures.

Toffler (1970) further explained what role globalization plays in organizational development and change. In general terms, organizational development is regarded as a planned, ongoing effort to change an organization to be more effective and humane (Beer and Walton, 1987; Greiner and Schein, 1988). Organizational development is used to describe approaches, processes, and methods to improve the functioning and effectiveness of organizations. It normally involves consultants or change agents that help the organization restructure or develop and implement new structures and practices (Senge, 1992).

2.1.1 Change Management

Paton and McCalman (2008) argue that change management never is a choice between technological, organizational or people-oriented solutions; instead, implementing successful change involves combining these factors into the “best fit”.

There are vast amounts of research done within the field of change management studies, each one with its own niche. However, John Kotter, Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership, Emeritus at Harvard Business School, has over time developed a well-recognized definition of change management. Kotter (Forbes, 2011), distinguish change management as set of important tools or structures designed to keep any change effort under control. Kotter emphasizes that change management is about pushing the organization onwards, meanwhile trying to minimize disruptions, and basically keeping things under control. Change management is according to Kotter done with small change management groups

inside the organization, sometimes with external consultants that are specialized in the area.

This definition of Change Management is connected to use of external management consultants, as mentioned by Kotter above. This connection needs some further elaboration. Hiring a management consultant as a tool to resolve change related issue is considered as best practice since the management consultancy industry is constantly growing, as presented in the background section.

2.1.2 W hat is a Change Agent?

The concept of change agents has transformed during the past decades, resulting in more than one definition. Traditionally change agents were seen as charismatic leaders with close to heroes’ status who destroyed rigid and inflexible structures Caldwell, 2003, p.1). Harvard Literacy for HR Professionals, (2005 p. xiii) defines the change agent’s task as: “Initiate and lead the organizational changes that a company must make to remain competitive in the face of major business shifts.” Other authors have defined change agents as:

”A change agent is a person who leads change—an influencer who initiates or helps others implement new ideas and strategies”

(Carr, 2008, p. 48) “A change agent is a person who: leads a project or initiative that creates a

change in the “way things are done around here;” defines how the change(s) will be implemented; defines the reality of what’s involved in the change, regardless of the popularity of the change; selects and identifies who and what they need for the change to be successful; and troubleshoots challenges throughout the change process”

(Cohen, 2006, p. 114) What they have in common and what can be agreed upon is that a change agent leads change for the greater good of the organization. There are still many models and types of change agents as well as endless situations where they are needed (Caldwell, 2003). The most common differentiation between change agents is that they can be either internal or external ones. Kurt Lewin was the first to classify change agents as either someone who can be found internally within a company or someone brought in externally to initiate change. Change agents can be divided into different types (Jagodic, 2009). In this paper we will focus on the external change agent also referred to as a management consultant. There are pros and cons with both approaches; an internal change agent is already familiar with the company’s culture and is thus less inclined to create disruption. However an external may prove unbiased to ‘old’ ways of doing things and contribute with a fresh view (Harvard Literacy for HR Professionals, 2005).

2.2

Management Consultants

Below we discuss when, and for what reason, management consultants are commonly used. We also discuss the different approaches and limitations using the services of a management consultant for the client view. Finally, we present the width, growth and importance of the industry.

2.2.1 W hen and W hy Do O rganizations U se Management Consultants? One common reason to use a management consultant is the need for additional skills and experience. In organizations there can be a shortage of specific skills that can be adjusted or complemented by contracting an external management consultant. A reason to bring in a management consultant is for the fresh and objective perspective (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). When working closely with a problem for a period of time, it is easy to become narrow-minded and focus only on one single solution. It can be hard to diverge from certain logic, especially if there is a personal interest in the matter. Another common reason to use management consultants is the lack of time for managers to address projects beyond regular work assignments. A management consultant can also be acquired when investigations of legal, regulatory or ethical matters is requested for any reasons (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). Management consultants work individually or in a team with the purpose to advise and assist organizations of how to improve their business. Management consultancies focus on management problems such as overall business strategy and operational techniques. Commonly, management consultants provide practical recommendations for the employing organization. (Business Dictionary, 2012; All Business, 2012).

Other authors recognize that the management consultants usually gather data first in order to provide concrete ideas and recommendations. While doing so, it is important that the management consultant stays essentially objective and detached of the client (Margulies and Raia 1972). However, in process oriented management consultancy the consultant is more involved and aim to facilitate clients to develop their own solution to their problems. The consultant forms a relationship with client and its staff. Instead of focusing on a single problem the consultant give consideration to other parts of the organization (Margulies and Raia 1972). This approach to management consulting can be defined as the prescriptive approach. The consultant listens to the client, gather necessary data, interpret given information and finally present a solution or a recommendation to the client. The style is based on the assumption that the client lack skill, expertise and objectivity to suggest solutions themselves. Even though the client might lack the expertise of the consultant the client is likely to have some opinions of their own, which makes it essential for the consultant to be careful not insult or alienate the client while presenting suggestions (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009).

There are some disadvantages and limitations with management consultants. Cost is one of the arguments against using management consultants. However, when consultants’ are requested it is generally because the organization needs their expertise and experience. Therefore when addressing the issue of costs it is important to monitor and balance it against value provided to the client (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). Another disadvantage is the fear and resentment that may rise amongst employees. The employees may take offence and be less than co-operative in fear that the consultant’s result and recommendations may cause cut-offs (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). Even with internal management consultants, resentment may occur as employees may interpret that they are not skilled or experienced enough to solve the problem. Also, lack of familiarity with client and the organization may offset the advantage of fresh perspective. This is because resources must be spent for the management consultant to first learn about the organization before effective consultancy can be conducted (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). A fourth issue with external consultants is their shortage of responsibility/accountability of results. Often a management consultant’s work is finished as recommendations are presented to the client organization. Hence follow-up and implementation is left to the client to handle while the management consultant avoids responsibility of the recommendations effectiveness or implementation (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009).

2.2.2 Management Consulting Market O verview

The industry of management consultancy started to grow considerably after the 1970’s. Revenue of management consultancy firms registered with the Management Consultants’ Association (MCA) doubled by 1980’s and by 1987 the revenue had further increased fivefold. Furthermore the number of consultants registered with MCA in the UK, quadrupled to 6963 between 1980 and 1991. In the early 1990’s it is believed to have been around 100,000 consultants worldwide and recent years have showed a continued growth. For example, the largest company, Andersen Consulting showed a regular 9 % growth, and the second largest company, McKinsey doubled their revenue between 1987 and 1993 (Ramsie, 1996).

In a study from 2003 compiled by Swedish Statistics (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2012, p.8) shows an overview of the Management Consultancy business, with focus on organizational development. The statistics shows the following distribution (based on number of employees):

Table 2-1 Management consultant market overview

0 - 19 20 - 49 50 - 99 100 - 249 250 - Total

No. Companies 40 033 206 50 21 16 40 326

No. Employees 29 710 6 196 3 401 3 071 11 970 54 348

These statistics shows a clear dominance of small enterprises with less than 19 employees. However, the top 16 enterprises employ 22 percent of the total number of employees, with an average of approximately 748 employees per company. On the other hand the smaller enterprises employees less than one person per company. The number of companies has increased significantly since the initial year 1998, amounting to 2 percent from 2000 and 26 percent from 1998. The number of employees has increased with 2 percent from 2000 and 25 percent from 1998. Looking at the historical development we can assume that these figures have a continuous growth pattern. Hence, making today’s population larger. There is however no recent research available to emphasize this.

The industry of management consultancy has experienced an increase in net turnover since 1998, an increase of nearly 43 percent. The specific industry of organizational development was responsible for approximately 70 percent of this increase. Swedish Statistics has made the observation that the industry’s dominant customers are commercial, profit-driven organizations, corresponding to 85 percent of total net sales. If we incorporate export-driven sales the figure amounts to 91 percent. Government and public sales amounted to 9 percent of net sales, and private actors to a mere 1 percent.

2.3

Previous Research on how Management Consultants

Differ

The following two sections incorporate previous research on management consultancy (change agent) bias, and choice of theory. The research below works as an inspiration for our thesis.

2.3.1 Tichy and N isberg’s Research on Change Agent Bias

The research compiled by Tichy and Nisberg (1976) focuses on the different contexts OD practitioners (change agents) come from and what impact that has on the diagnostic interventions they propose. Tichy and Nisberg served seventy-five OD practitioners with a case study that concerned a dispute among factory-line employees in a manufacturing firm. The authors asked the OD practitioners what

were the ten ‘most important’ diagnostic questions they would ask before accepting a contract with the firm. Tichy and Nisberg proceeded on this route to establish whether there was any correlation between the preconceived frameworks and assumptions the OD consultants held and the OD interventions that they proposed. OD practitioners may come from a variety of backgrounds that encourage them to see things in terms of either personal or interpersonal dimensions, technical and structural dimensions or in terms of cultural dimensions. The OD practitioners that were evaluated were guided in their work by their particular sets of assumptions and beliefs, however in many of the cases the evidence of such guidance was implicit and hidden.

Tichy and Nisberg (1976) have made a number of conclusions based only on their own interpretations of the results of the surveys. The authors rely strongly on their own previous work and reference other sources only three times. This demonstrates a lack of scope to the research and findings and ultimately diminishes the persuasiveness of the arguments. Although the research and article is nearly 36 years old and somewhat questioned, Tichy and Nisberg shows us that this specific area of organizational development and change agents’, potential bias is subject of further discussion and investigation.

2.3.2 Burke and Bazigos Research on O D Practitioners’ Choice of T heory

Burke and Bazigos presented in 1997 a report on existing theories that guide OD practitioners in their work. The authors argue that there is an increasing focus on how OD practitioners’ values, motives, competences and activities differ and how this affects their work. The article tries to capture the different diagnostic models and theories used within organizational development and by OD practitioners. The authors try to relate this to a new and overall model that can be used by all OD practitioners. By conducting a questionnaire, OD practitioners could rank and choose among different theories and models on a 40 item scale (40 questions). The 40-item scale corresponded to 8 different organizational development theories with 5 questions, or statements, on each theory. The participants ranked the extent to which they felt that one statement (out of 40) corresponded to their beliefs, values or how they normally work (Burke and Bazigos, 1997).

Some of the findings showed significant differences among those theories that were used or preferred. These results were also found to correlate to demographical differences among the participants (Burke and Bazigos, 1997). Burke and Bazigos also recognize that:

“… It is likely that practitioners, heterogeneously prepared, do not act from a uniform knowledge base. From the ensuing statistical “noise” that heterogeneity creates, the strongest discernible factors to emerge are

intuitive perceptual framework.” Furthermore, that “…the picture of organization perception mirrors a taxonomy of person perception.”

(p. 403). Hence, Burke and Bazigos (1997) recognize that OD practitioners’ diagnosing and interpretation of organizations are different when OD practitioners’ comes from different backgrounds and environments.

3

Problem Statement and Research Q uestion

As the research presented in our Background section shows, the way management consultants’ conduct their work varies and can be influenced by the management consultants’ background. The market for management consultants yields substantial revenue. Hence, a clear and transparent characterization of a management consultants’ background and its effects on the management consultants’ way of identifying a problem seems beneficial. This may provide up-front knowledge and information to potential clients of management consultancy services. Also, it would offer the industry of management consultancy a chance of more self-criticism and awareness.

We will throughout this bachelor thesis work with the following research question:

“Do management consultants background have an impact on their identification process of problems in a given consultancy situation?”

In extension, we elaborate on this research question to bring clarity to the issue: “How do management consultants’ background affect the way they identify

problems in a given consultancy situation?”

We wish to investigate if there is a pattern between how a management consultant identifies problems in a given business simulation and their background, given by a number of demographic variables. We will test the demographic variables and compare these with the way a management consultant identifies a problem within an organization, i.e. recognize a need for change. The focus of this report will be strictly descriptive and whether or not each management consultant’s background affects the way they identify problems.

As to our knowledge there is no extensive research focused on our specific area of interest. It is our ambition to enlighten the relationship, which we believe exist, between a management consultant’s background and actual practice. We find that this descriptive analysis might be interesting for scholars as well as practicing management consultants. Scholars within change management strive to innovate their field of study and hopefully this descriptive analysis might inspire to study a dimension of management consultants’ behavior, which has not yet been extensively explored. Practicing management consultants, mainly within organizational development, may find this work interesting as a further exploration of a management consultant’s unique characteristics.

4

Purpose

We will conduct an experimental, descriptive study in order to statistically test if our independent, demographic variables have any effect on the dependent variables, which reflects a management consultants perceived preference when identifying problems. The independent, demographic variables will as mentioned before, constitute the management consultant’s background. We will measure this by exposing management consultants’ to a laboratory business simulation. The information is to be collected through a self-administered questionnaire survey. The purpose of this research study is to test whether there is any pattern or relationship between management consultants’ personal background and how they identify a given set of problems.

5

Definitions

Change – When you break the status quo or make something different (Oxford Dictionary, 2012). Several authors within change management and organizational development (Defined below) highlights the importance of change, namely that organizations and companies adjust its processes, systems, strategies and businesses to be more aligned with the external environment (Kotter, 1996)(Paton and McCalman, 2008)(Senior and Swailer, 2010).

Change Management – Change management can be defined as how you plan change and conduct its implementation in a systematic manner. Kotter (2011) defines change management as the set of basic instruments and models used to keep the change process under control. Hence, the theories and academia of change management helps businesses to facilitate change.

Change agent (Internal and External) – Harvard Literacy for HR Professionals, (2005 p. 13) define change agent as: “Initiate and lead the organizational changes that a company must make to remain competitive in the face of major business shifts.” Others have defined change agents as: "A change agent is a person who leads change—an influencer who initiates or helps others implement new ideas and strategies” (Carr, 2008). What they have in common and what can be agreed upon is that a change agent leads change for the greater good of the organization. As noted by Richard Beckhard (1969), change agents can be an internal one, employed by the organization, who can facilitate change. Or he or she can be an external change agent, and is then contracted by the organization and comes from outside the organization, to facilitate change.

First Impression – We have used this definition as a collected measure in our statistical analysis and hypothesis motivation. This definition is given by the management consultants’ preference regarding the 12 organizational dynamics presented by Burke and Litwin (1992), ranked on a 7 grade Likert scale.

Organization Development (OD) – Thomas Cummings (2004) defines organizational development as structured methods and planned actions. This creates systematic change so that organizations can more easily adapt to its external environment and become more effective and efficient. Organizational development theory is considered as the theoretical framework used in organizations, when a specific outcome is desirable in a change processes.

OD practitioner – In terms, and OD practitioner is a person who exercises organizational development practices. He or she can either be internally employed or externally contracted (Cummings, 2004). Due to its similar nature, change agents and OD practitioners are in many cases similar roles if not exactly the same, which is why Tichy and Nisberg (1976) use these concepts interchangeable throughout their research.

Management Consultant – A management consultant represents a consultancy firm that is contracted by an organization or company to exercise specialist skills, and/or advise them in different matters, depending on the needs of the organization (Hilditch-Roberts, 2012).

Due to management consultants similar role to an external change agent or an external OD practitioner, we will treat these three concepts as one: A person who externally enters an organization with intention to advice in, mediate or realize a situation which requires a change of behavior, structure, processes or strategies.

6

T heoretical Model

As discussed earlier in the Background, both internal and external forces can trigger change. This is also reflected, in the different models and tools used when diagnosing organizations within the field of change management and organizational development (Burke and Litwin, 1992). Extensive research has previously been made in the subject, and a number of different models are available within the area. However, we will concentrate on the Burke-Litwin’s “Casual Model of Organizational Performance and Change” since it is a comprehensive model within organizational development. Burke and Litwin furthermore (1992) acknowledges that their model is strongly influence by the work of other well know researchers in the field, such as Nadal and Tushman, Kotter and Weisbord.

6.1

T he Burke-Litwin Casual Model of Organizational

Performance and Change

Kotter’s integrative model of organizational dynamics and Nadler and Tushman’s (1980) congruence model are both models that stresses that organizations are means of taking inputs (externally) and transforming it (internally) to outputs. Hence, both models emphasize the importance of a functional transformational process that occurs within an organization, due to its external and internal environment (Porter, Nadler and Cammann, 1980). Both models, and the idea of inputs that transforms to output through and with the help of the organization, have been the foundation for the Burke-Litwin model (Burke and Litwin, 1992). Burke and Litwin (1992) recognized that an organization consists of several linkages and processes that can be nearly impossible to control or to predict. Hence, in order to easier understand how different influences, such as culture, strategy, leadership etc. affects an organization, Burke and Litwin developed their “Casual Model of Organizational Performance and Change” in 1992 (Burke and Litwin, 1992)

Figure 6-1 Burke-Litwin Model

In order to comply with our research question and purpose with this report we feel a more clear definition of the different dynamics, or “boxes”, in the model is needed.

External environment: Refers to any outside influence, factor or situation

that would affect the performance of the organization.

Mission and Strategy: Refers to the mission and strategy defined by the

management of the organization and how employees interpret this as the purpose of the organization.

Leadership: Refers to leaders’ behavior and the perception by employees of

these leaders.

Culture: Refers to the collection of rules, norms, values, and principles that

guides the organizational behavior.

Structure: Refers to how functions are related to each other and how people

have been allocated different roles and responsibilities. It also involves norms on how to communicate; decision-making processes and defines the relationship between different functions.

Management practices: Refers to how management reassures that human

and material resources are utilized and managed, to be aligned with the organization’s strategy and mission.

management to control the utilization of human and material resources. Examples of these are control systems, reward systems, information systems, budget development etc.

Climate: Refers to current work climate among employees within an

organization. The impressions, feelings and expectations that employees expresses and their relationship towards coworkers and managers.

Task requirements and Individual skills: Refers to the job-person fit between

individuals, the skills, knowledge and attributes these possess and what is required of them to carry out the job effectively.

Individual needs and values: Refers to the intrinsic and extrinsic values and

needs of individuals.

Motivation: Refers to the motivation is needed to satisfy individuals and

make them work towards realized goals.

Individual and organizational performance: Refers to the actual outputs of

the inputs and transformational process that occurs within an organization.

(Burke and Litwin, 1992) The Burke and Litwin model emphasizes the external environment as provider of inputs to an organization. The organization then transforms the inputs into outputs, which corresponds to the “Individual and Organizational Performance” dynamic, in the Burke and Litwin model. What differs from precedent models is that Burke and Litwin acknowledges that the individual and organizational performance also affects its external environment through interactions with external environment. These interactions take the form of products, services and customer service, which the organization provides as outputs (Burke and Litwin, 1992).

Burke and Litwin also acknowledge that the model only shows what relative weight, or importance, each influence or dynamic has to potential change. As an example, Burke and Litwin argue that a change in an organization’s mission or strategy foremost corresponds to changes in external environment. Hence a change in mission or strategy affects other dynamics of the organization (Burke and Litwin, 1992).

The model indicate no importance of to where the change progress actually start, but instead gives a framework on how to describe the dynamics that need to be taken into consideration when diagnosing an organization.

6.1.1 T ransformational and T ransactional Dynamics

Burke and Litwin also suggest that the 12 dynamics can be divided and categorized into two smaller models. The upper half of the original model, including: “External

Environment”, “Mission and Strategy”, “Leadership”, “Organizational Culture” is

called Transformational dynamics (Burke and Litwin, 1992). By transformational, Burke and Litwin refers to areas of an organization that might change as an effect of external environment. These external forces ultimately influence the organization to such a degree that it alters the behavior of the organization. Changes like these often fundamentally affect the organization so that it needs to acquire whole new sets of behavior or strategies to work by (Burke and Litwin, 1992).

Figure 6-2 Transformational Dynamics

Transactional factors on the other hand, refer to dynamics within an organization that can more easily be altered or modified. Transactional changes within an organization derive from the internal environment, and by undertaking smaller changes, enable the organization to become more streamlined and efficient (Burke and Litwin, 1992).

Figure 6-3 Transactional Dynamics

The concepts of transformational and transactional dynamics both derive from academic theories within the field of leadership studies. We intend to use these two concepts and models as an extension of Burke and Litwin’s original model to more thoroughly test our data. This will be elaborated in the following section where we motivate our hypotheses.

7

H ypothesis

As first discussed by Lewin, presented in the work by Crowther and Lancaster (2009), a change agent is a professional who initiates change in an organization. The change agent is either employed by the organization or externally hired as a management consultant. Margulies and Raia (1972) argue for several situations when an external management consultant is to be appointed. Firstly, organizations often fail to acknowledge what is wrong, and the organization need help to locate the actual problem. The authors point to a catch 22 in this situation, namely since the organization do not know the problem; it cannot seek the correct help. Secondly, if the client organization learns to diagnose its own strengths and weaknesses with management consultants’ objective help, the client can be more effective in the future. Lastly, the management consultant is an expert on how to diagnose processes and problems of all variations, and how to establish effective supportive relationships with a client. An effective problem consultation involves passing on the ability to identify problems to the client. Margulies and Raia emphasize that since the decision to change is the client’s; it is necessary to work jointly with the organization members to generate a successful solution. A collaborative approach between the external management consultant and client is therefore essential.

The role of an external change agent undoubtedly varies depending on the variation of the problem; specifically what organizational developments are necessary in order to implement change. Caldwell (2003) claims that a change agent may be an advisor, educator, counselor or analyst all depending on what the client needs in that situation. A management consultant is either oriented towards solving a single task (task oriented approach), or implementing a complete process (process oriented approach). In the former the consultant’s role is that of a ‘technical expert’ hired to solve a problem normally centered to only a part of the organization (Margulies and Raia, 1972). Henderson (1990); Tilles (1961); Zeithaml (1990) all emphasize these two different approaches. Consultants interchangeable use the different approaches with one client in the problem identification and solving process (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). There is no overall framework available of how to conduct a consultancy project since every project varies considerably in problem, nature and context. However, the natural starting point is to identify the problem and underlining issues (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009).

Herman, Dunham and Hulin (1975) and Talbibi, Pfeffer and Sharif (2012) argue that peoples’, and in extension management consultants’, behavior varies depending on their background. Hence, it is logical to assume that people with similar backgrounds show similar behavior pattern. As a consequence we will test if different backgrounds among management consultants lead to different behavior when identifying a problem. Bell, Villado, Lukasik, Belau and Briggs (2011) emphasize in their research that depending on the situation, different

demographic variables, which constitute the personal background of a management consultant, show either positive or negative relationship to performance and result. The demographic variables used to denote a management consultant’s personal background in this thesis are: “Age”, ”Country of Birth”, ”Location of Office”, “Childhood”, “School”, “Education”, ”Work-life Experience”, “Employer/Company” and ”International Experience”.

People within the same age range share characteristics associated with that age range, such as beliefs, attitudes and expectations (Kotler, Armstrong, Wong and Saunders, 2008). Older people have more life experience from which they extract knowledge compared to someone younger, due to the simple fact that they have lived longer. Differences in age also become noticeable when looking at what stage in life people are. Someone in their mid-twenties does not share the same priorities as someone in their mid-fifties (Cogin, 2012).

”Country of Birth” denotes where someone is born. It is a widely accepted concept for ethnicity, describing peoples’ heritage and cultural background. The advantage of ”Country of Birth” is its objectivity and stability compared to the concept of ethnicity (Stronks, Kuku-Glasgow and Agyemang, 2009).

Cultural geography is important because people are affected by where they live and reside. It affects lifestyles, practises and how people differentiate themselves from others (Crang 1998). Hence the variable ”Location of Office” is important since it indicates where management consultants live. Also, for similar reasons the variable “Childhood”, the country where people spent the majority of their upbringing, affect peoples’ cultural background. During early years of childhood to young adulthood, children absorb the culture of their surroundings to a high degree and these early influences stay with them for life (Crang 1998).

Educational background has a significant impact on peoples’ differences in behavior (Bell et al. 2011). In this thesis, different “Schools” and varying “Education” constitutes a management consultant’s educational background. “Schools” differ in how they teach e.g. different professors, literature and teaching approaches (Personal communication May 15, 2012). Furthermore, universities have their own niche of how to present themselves e.g. Jönköping International Business School distinguish itself through entrepreneurial and international focus (JIBS website, 2012) while Uppsala University strives for quality, knowledge and creativity since 1477 (Uppsala University website, 2012). Educational fields reflect peoples’ type of knowledge, within which area of expertise and how their learning experiences have differed (Bell et al. 2011). The variable “Education”, used in this thesis reflects which main academically field management consultants focused upon during their studies.

Organizational tenure is a measure of the time people have invested in an organization, the concept is important due to understanding of social knowledge,

productively operate within the organizational system (Bell et al. 2011). In substitute to organizational tenure we use the term professional tenure, in which participants’ work life experience as management consultants within organizational development, is measured. Giffords (2009) describe the term as:

“Professional collegiality, which represent a distinct professional subculture characterized by a sense of community, shared identity, and common values of the profession.”

(p.390) Management consultancy firms have specific guidelines on how employed management consultants are to conduct their work (Personal communication January 24, 2012. As mentioned, organizational tenure affect norms and behavior within an organization. However with specific guidelines, being employed at a certain company indicates similar behavior without long tenure. From this point of view the company itself should have a large impact on how its management consultants perform and execute their work.

Erichsen (2011) is one among many who has investigated how international experience affects people. A general agreement is that international experience change peoples’ perception, widen their horizon and self-awareness. Our variable ”International Experience” is divided between studying and working in order to notice if there are any difference between the two.

Based on the above discussion we argue that depending on each management consultant’s personal background; constituted by the demographics above, have an impact on how they identify a problem, given by their “First Impression”. Hence, we give the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a: “The demographics (Age, Country of birth, Childhood, Location of Office, School, Education, Employer/Company, Work life Experience, International Experience) that constitutes a management consultant’s background have an impact on the First Impression”

Burke and Litwin (1992) emphasized in their research that the 12 organizational dynamics presented in their model could be divided into two separate compilations. As discussed earlier, Burke and Litwin label these two compilations “Transactional Dynamics” and “Transformational Dynamics”. The “Transactional Dynamics” symbolize the primary way of change via relatively short-term mutual exchange among people and groups. Transactional behavior is associated with the everyday interactions and exchanges that more directly create the work unit climate in the organization. An organization will experience transactional related problems if there is e.g. a lack of vision and mission clarity, or when role and responsibility structure is not enforced by manager practice. The “Transactional

Dynamics” is according to Burke and Litwin (1992) concerned with soft values, namely the more subjective orientation of organizational issues.

“Transformational Dynamics” is concerned with the processes of organizational transformation, which is fairly fundamental changes in behavior (e.g. value shifts). Such transformational processes are required for genuine change in the culture of an organization. Organizational change, e.g. an overhaul of the entire organizational strategy, originates from external environmental impact rather than any other variable. The “Transformational Dynamics’” compilations concern the areas in which change is likely caused by interactions with environmental forces (e.g. changes in the competitive business environment and government regulations) that will require an entirely new behavioral set from the client. Burke and Litwin (1992) emphasize that not only external factors spring transformational change, but also transformational leaders play an important role. Burke and Litwin conceptualize this section of the 12 organizational dynamics as hard values, namely the objective orientation of the organizational issues.

The authors emphasize the transactional compilations of the original 12 organizational dynamics with the research of Cummings (1982). Burke and Litwin stress the compilations as one of two approaches to increase the performance in the organization, i.e. a way of initiating change. Hence, as it exist two approaches, management consultant might prefer one or the other, preferring a soft (transactional) or a hard (transformational) approach to initiate change. Accordingly, we give the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b: “The demographics (Age, Country of birth, Childhood, Location of Office, School, Education, Employer/Company, Work-life Experience, and International Experience) that constitute a management consultant’s background have an impact on the Transactional Dynamics.”

Building on the above arguments, we give the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1c: “The demographics (Age, Country of birth, Childhood,

Location of Office, School, Education, Employer/Company, Work-life Experience, and International Experience) that constitute a management consultant’s background have an impact on the Transformational Dynamics.”

We will further test our belief by measuring the impact of each of the 12 organizational dynamics (“Age”, ”Country of Birth”, “Childhood”, ”Location of Office”, “School, Education”, “Employer/Company”, ”Work-life Experience”, ”International Experience”) impact each of the 12 dynamics (“External Environment”, “Mission and Strategy”, “Leadership”, “Organizational Culture”, “Structure”, “Management Practices”, “Systems”, “Climate”, “Task requirements and Individual skills”, “Individual Needs and Values”, “Motivation” and “Individual and Organizational Performance”). Hence we also hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1d: “The demographics (Age, Country of birth, Childhood, Location of Office, School, Education, Employer/Company, Work-life Experience, International Experience) that constitutes a management consultant’s background have an impact on each Dynamics individually

8

Method

Below we present our choice of method to answer the research questions and test the hypotheses. We begin the section with a summary of how the research was conducted, for more elaborative details see individual subheadings.

We have chosen to conduct an experimental, descriptive cross-sectional research study. We will apply a monitor process of data collection and use a quantitative method in the form of a self-administered online questionnaire survey, which is assessed through Qualtrics and distributed to participants by email.

The questionnaire is constructed in a manner, in which the respondents have to answer each of the closed questions on a laboratory business simulation.

The participants in this thesis were chosen through a systematic random sampling process.

Hypothesis was tested using multiple regression model analysis in order to find statistically significant functions between our dependent and independent variables. Furthermore correlation between variables was investigated using a correlation matrix.

8.1

Research Design

First, we want to acknowledge the purpose of putting together a well-disciplined research design. As Cooper and Schindler (2011) define it, research design is concerned with the structure and framework of the research itself. By thoroughly look into the research design we will consider the research’s data collection methods, the purpose of the study and the research environment.

8.1.1 Data Collection

We have chosen to collect our data through a monitoring process, as suggested by Cooper and Schindler (2011). A monitoring process can be described as when the research attempts to document frequencies or totals.

8.1.2 Experimental and Descriptive Research D esign

By conducting an experimental and descriptive research design, we can investigate whether different variables have any relationship with other variables. Also, with a descriptive study, we can make use of hypothesis or more investigative expressed research questions, which is often perceived as more formal and structured and

works better when investigating correlation and association between variables (Cooper and Schindler, 2011).

8.1.3 T he T ime, Scope and Environment

Cooper and Schindler (2011) emphasize some aspects that need attention during a research, such as the time dimension, the scope and environmental conditions. The research for this thesis is conducted as a cross-sectional study, meaning it is conducted at a specific point of time. With regards to the scope of the research, we will use statistical studies, which are concerned about the wideness and generalization of the study, and includes hypothesis tested through quantitative data collection. We will create a fictive research environment that is considered as being manipulated or conceived, to control the research variables. Our laboratory research design is developed through a simulation, which replicate conditions from an authentic scenario.

8.1.4 Q uantitative Research

We can conclude that quantitative research is often used when describing the relationship between independent and dependent variables or the cause and outcome of different observations (Hopkins, 2000). Therefore we will collect quantitative data through a self-administered questionnaire survey, in order to comply with our research question and research design. Furthermore, it offers many benefits with regards to time and cost dimensions (Cooper and Schindler, 2011)

8.1.5 Survey

We use survey as communication approach. Cooper and Schindler (2011) explain that surveys are tools, which can be used to derive information from a sample chosen by the researcher. The gathered information can later be compared so differences, associations, relationships and similarities can be found. The use of surveys as a research tool is encouraged by Crowther and Lancaster (2009), when looking for descriptive data, and that survey research is essentially and excessively used when there is a need of many respondents.

8.1.6 Q uestionnaire

It is important that the questionnaire is straightforward, unbiased and aim to keep the respondent interested and motivated throughout the questionnaire (Charlesworth and Morley, 2000).

We used closed questions since these are easy to structure and analyze the answers. There are limited options or alternatives on what and how to answer the closed question (Charlesworth and Morley, 2000).

When enabling ranking among answering alternatives in the survey, we adapted a “Likert Scale” (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). The scale is a tool used to rank attitudes towards different statements and was first developed by Rensis Likert in 1932. The scale normally ranges between disagreeing and agreeing on a specific statement and how intense the respondent feels about a statement (Albaum, 1997). Following the same logic our respondents ranked organizational dynamics between 1 (extremely unimportant) and 7 (extremely important).

The answering alternatives, the organizational dynamics, were derived from Burke-Litwin’s “Casual Model of Organizational Performance and Change” (Burke and Litwin, 1992), presented earlier in this report. Respondents ranked the importance they placed on the different dynamics presented in the model, using the Likert scale. Giving us respondents’ ranking on each organizational dynamic associated with the set of problem(s) in the laboratory business simulation.

See Appendix 1 for the questionnaire.

8.1.7 Simulation

The laboratory business simulation used in our research is based on an authentic situation and inspired by researchers’ personal experience. When developing the laboratory business simulation we took into consideration several highlighted characteristics that constitute a business case, according to the handbook by William Ellet (2007).

8.1.8 Feedback on Business Simulation and Q uestionnaire

We presented the business simulation and questionnaire survey to colleagues and practitioners within organizational development, along with friends and family. According to Cooper and Schindler (2011), this momentum that is called pilot testing is often used to test the test statistic and look for any potential environmental or control issues that might occur in the research study. We disregarded this momentum in our pilot testing, and only chose to test for errors in design and language, and letting the respondents question and give feedback on any complicated or misinterpreted information, questions or technique. See Appendix 2 for test feedback.

8.2

Sampling, Sample and Response Rate

Russel Bernard’s (2000) Social Research Methods give a comprehensive explanation on the use and differences among samples. According to Swedish Statistics of the year 2003 there were approximately 54 000 people employed as management consultants. Due to difficulties in mapping the whole population of management consultants, we accumulated a systematic random sample out of the whole population.

We chose to contact management consultants that work within organizational and strategy development, at management consultancy firms with 10-200 employees. The management consultancy firms were singled out using a systematic approach where we selected every fifth firm out of 890. Our sample frame (Bernard, 2000) constituted a total of 39 selected organizations that corresponded to a total of 1000 management consultants (121.nu, March, 2012).

Out of 1000 contacted, 167 answered and 83 partially or fully completed the survey. Because of confidentiality reasons, we cannot give any further detailed information regarding participants, respondents or companies contacted.

8.3

U se of H ypothesis

Aczel and Sounderpandian tell us that hypothesis testing is an important function within statistics (2009). The authors describe hypothesis testing as the process of testing if a thesis, a proposition, is true or not. For this thesis we will use explanatory hypothesis, which is the most used type of hypothesis. Explanatory hypothesis are propositions thesis regarding the association between two or more variables and how changes in one variable affect the other variable(s) (Cooper and Schindler, 2011).

8.4

Multiple Regression

As explained by Copas (1983) regression models and analysis are used to statistically predict or to forecast outcomes. By testing for associations between independent variables and dependent variables, a function and statistical relationship can be found between the two. Since we have more than one independent variable in our regression model we need to use a multiple regression model. It is used to explain how or how much a dependent variable may change when an independent variable changes, when other variables are held constant (Aczel and Sounderpandian, 2009).

8.4.1 Correlation Matrix

By putting together a correlation matrix, we can test for correlation between single variables. We used Pearson´s product-moment coefficient as test statistic, formally known as “Pearson correlation” (Aczel and Sounderpandian, 2009) and conducted 2-tailed tests on all (64) variables. Whether correlation is significant or not depends on the alpha or significance level chosen by the researcher.

8.4.2 Independent and Dependent Variables Explained

Researchers are often interested in how different variables affect each other, what cause and effect relationship they carry. A variable or factor that is affected by another interrelated variable is called dependent variable. The dependent variable will be influenced by other variables or factors in the research, called independent variables. The independent variable can be employed and influenced by the researcher.

8.4.2.1 Dependent Variables

We constructed a series of dependent variables, derived from Burke-Litwin’s “Casual Model on Organizational Performance and Change”. By using change management terminology and Burke-Litwin’s extensive and recognized model as a foundation for our dependent variables, we ensured correct terminology and objective communication with our sample population. This enhanced the possibility of more accurate responses that easier allowed categorization, statistical comparison and interpretation. The dependent variables were constructed as such, that they corresponded to or included, fully, partially or separately the 12 organizational dynamics of the Burke-Litwin’s model presented in the Theoretical Framework (figure 6-1).