Digital Transformations in

Family Businesses

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration - Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Pontus Lindholm & Brandon Stewart TUTOR: Karin Hellerstedt

An exploratory study examining how non-financial aspects

influence digital transformations in family businesses

Master Thesis within Business Administration

Title: Digital Transformations in Family Businesses: An exploratory study examining

how non-financial aspects influence digital transformations in family businesses

Authors: Pontus Lindholm & Brandon Stewart

Tutor: Karin Hellerstedt

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Digital transformation, Family business, Non-financial aspects, Socioemotional wealth, Change management, Organizational change.

Abstract

Background: The advancement and spread of digitalization is reshaping the commercial landscape for firms, executing proper and adequate digital transformations have therefore become a necessity in order to thrive in the digital era. Existing literature has indicated that the unique and distinctive characteristics that family businesses possess may shape the way such firms handle various change efforts. However, research of how family firms handle digital transformations is heavily undeveloped, where the non-financial aspects’ influence on such transformations has yet to be assessed.

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to investigate how non-financial aspects could influence a digital transformation process in family businesses. By fulfilling this purpose, additional insights can be contributed and enable a more thorough understanding of how non-financial aspects influence digital transformations in a family business.

Method: This qualitative and exploratory thesis, guided by an inductive approach, has utilized a multiple case study containing four different cases in order to generate more insights and create a better understanding regarding the topic at hand. Eleven semi-structured interviews have been conducted and a thematic analysis has served as guidance when interpreting and analyzing the data.

Conclusion: The results of the research reveal that four non-financial aspects were identified through the multiple case study. However, merely three of the four non-financial aspects identified were found to influence digital transformations in family businesses, encompassing both advantages and challenges which consequently affect a digital transformation. Additionally, the results show that one of the non-financial aspects solely had a positive influence on digital transformations, while the other two had both a positive and negative

Acknowledgments

We would like to express a big thank you to our tutor Karin Hellerstedt who has provided us with great feedback and guidance throughout the entire research process. With the advice and feedback from Karin, useful ideas and insights have been implemented in this thesis.

Secondly, we wish to thank all the participants who took part in this study. We are extremely grateful for the time and effort you have spent on this thesis, helping us gain valuable and fruitful insights.

Thirdly, we thank the fellow students in our seminar group for all the constructive feedback you have given us during the entire research process and the many valuable discussions.

Lastly, we express thank you to anyone else who in some way has contributed to our study and supported us along the way.

Jönköping

24th of May 2021

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 5 1.4 Definitions ... 62.

Literature Review ... 7

2.1 Digital Transformation ... 72.1.1 Incentives for Digital Transformation ... 8

2.1.2 Five Phases in a Digital Transformation ... 9

2.2 Change Management ... 11

2.2.1 Change Management Models ... 11

2.2.2 Resistance ... 14

2.3 Family Business ... 15

2.3.1 Familiness ... 17

2.3.2 Socioemotional Wealth (SEW) ... 18

2.4 Organizational Change in Family Businesses ... 20

2.4.1 Digital Transformation in Family Businesses ... 22

3.

Methodology... 23

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 23 3.2 Research Design ... 24 3.3 Research Approach ... 25 3.4 Research Strategy ... 26 3.4.1 Case Selection ... 26 3.4.1.1 Case A ... 28 3.4.1.2 Case B ... 28 3.4.1.3 Case C ... 28 3.4.1.4 Case D ... 293.5 Data Collection and Data Selection ... 29

3.5.1 Interview Guide ... 30

3.5.2 Interview Design ... 31

3.6 Analysis Method ... 32

3.7 Research Quality Insurance ... 34

3.7.1 Credibility ... 34 3.7.2 Transferability ... 34 3.7.3 Dependability ... 35 3.7.4 Confirmability ... 35 3.8 Research Ethics ... 36

4.

Empirical Findings ... 37

4.1 Why Family Businesses Conduct Digital Transformations ... 37

4.2 How Digital Transformations Unfold in Family Businesses ... 38

4.3 Non-financial Aspects Prevalent in Family Businesses ... 42

4.3.1 Authority and Influence ... 42

4.3.2 Engagement and Affection Towards the Family Business ... 43

4.3.3 Long-term Orientation ... 45

4.3.4 Building a Reputable Firm and Developing Strong Internal and External Relationships ... 47

4.4.1 The Decision-making Process ... 49

4.4.2 Inclusive Work Environment... 51

4.5 Digital Transformation Challenges for Family Businesses ... 52

4.5.1 Inertia Regarding Digital Transformations ... 52

4.5.2 Lack of Competence ... 53

4.5.3 The Role of Family Involvement and Influence ... 54

4.6 Resistance Towards Digital Transformations ... 56

5.

Analysis ... 58

5.1 Why Family Businesses Conduct Digital Transformations ... 58

5.2 How Digital Transformations Unfold in Family Businesses ... 59

5.3 Non-financial Aspects Prevalent in Family Businesses ... 60

5.3.1 Authority and Influence ... 60

5.3.2 Engagement and Affection Towards the Family Business ... 61

5.3.3 Long-term Orientation ... 62

5.3.4 Building a Reputable Firm and Developing Strong Internal and External Relationships ... 63

5.4 Digital Transformation Advantages for Family Businesses ... 64

5.4.1 The Decision-making Process ... 64

5.4.2 Inclusive Work Environment... 65

5.5 Digital Transformation Challenges for Family Businesses ... 68

5.5.1 Inertia Regarding Digital Transformations ... 68

5.5.2 Lack of Competence ... 69

5.5.3 The Role of Family Involvement and Influence ... 70

5.6 Resistance Towards Digital Transformations ... 71

6.

Conclusion ... 73

7.

Discussion ... 76

7.1 Theoretical Implications ... 76

7.2 Managerial Implications ... 77

7.3 Societal and Ethical Implications ... 77

7.4 Limitations ... 78

7.5 Future Research ... 79

Reference List ... 81

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter initially consists of a background regarding the topic of digital transformations and family businesses. Secondly, a description of why this topic is of interest as well as the purpose of this thesis is presented. Lastly, definitions of significance are included to enhance the understanding of what the thesis will contain.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The advancement and spread of digitalization have changed the way organizations operate and act in their surrounding environment (Schwarzmüller, Brosi, Duman & Welpe, 2018). The rapid acceleration of digitalization involves the rise of new digital technologies and innovative business ideas (Verhoef et al., 2021). It presents disruptions for organizations worldwide as society and firms must deal with the changes enacted by digitalization, which are currently reshaping the commercial landscape and challenging the status quo (Cortellazzo, Bruni & Zampieri, 2019). Furthermore, the changes and the general increased usage of digital technologies influence the organizational structure, work design (Colbert, Yee & George, 2016), and other critical functions of a firm (Sousa & Rocha, 2019). However, for businesses to be adaptive and thrive in the digitalized era, it is vital to re-evaluate existing business models and its associated dimensions in order to find new avenues for value creation (Dörner & Edelman, 2015), also known as a digital transformation (Fitzgerald, Kruschwitz, Bonnet & Welch, 2014). Hence, it is important to properly execute and handle different digital transformations, as they are crucial for the firms’ survival (Alonso, Kok & O’Shea, 2019). Furthermore, Verhoef et al. (2021) imply that a more digitalized world causes customer requirements and behavior to alter, which businesses could successfully manage and embrace through a well-executed digital transformation (Westerman & Bonnet, 2015).

Recent surveys indicate that transformations brought forth by digitalization are a major concern for family businesses that impose strategic challenges for family firms worldwide, which are of particular importance for the global economy given that two-thirds of firms in western countries are family businesses (Basly & Hammouda, 2020). A

multitude of family businesses are found to be small and medium-sized enterprises (Campopiano, De Massis & Chirico, 2014), generating a substantial amount of wealth and jobs across the world (Gulzar & Wang, 2010; Nordqvist, Melin, Waldkirch & Kumeto, 2015). Nonetheless, considering that family firms operate at the intersection between the work system and the family, complexities often arise (Melin, Nordqvist & Sharma, 2013). Family firms generally have a strong linkage between the business and family concerns, creating a more complicated organizational culture and structure to transform (Pounder, 2015). This close linkage is commonly referred to as familiness, impacting the way family firms function and operate (Habbershon & Williams, 1999; Moores, 2009). Furthermore, research suggests that family businesses possess distinctive characteristics, making them inherently different and unique (Poza & Daugherty, 2020). One major contributor to this reasoning is the fact that the literature suggests that family firms tend to emphasize non-financial goals and strive to preserve non-financial aspects (Batt, Cleary, Hiebl, Quinn & Rikhardsson, 2020; Berrone, Cruz & Gomez-Mejia, 2012). In relation to this, a prominent paradigm related to family business is the concept of socioemotional wealth, abbreviated SEW (Cleary, Quinn & Moreno, 2019). Although the non-financial goals and aspects may vary from firm to firm, literature suggests that they are highly intertwined with SEW, where an example is exerting influence over the business and keeping it within the family (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Chrisman, Sharma, Steier and Chua, 2013). According to Kammerlander and Ganter (2015), family businesses tend to pursue non-financial motives in order to accumulate SEW, sometimes forgoing economic goals in order to reach higher SEW. SEW is argued to play an incremental role in family businesses, where it acts as a crucial denominator to why family firms behave and act distinctively, hence instating that SEW is one major reason for why a family firm could be considered a unique entity (Berrone et al., 2012).

Family businesses, given their alignment of unique characteristics, are facing issues in the trajectory of coping with digital transformations (Chirico & Salvato, 2008; Pwc, 2018). Building upon the differences and unique elements prevalent in family firms, including the prioritization of non-financial aspects, entails both opportunities and challenges in coping with transformations and changes (Canterino, Cirella, Guerci, Shani & Brunelli, 2013). Given the specific dynamics that family firms operate under, research suggests that family businesses may face several challenges, where parameters such as

family involvement and losing control may inflict the change process (Kotlar & Chrisman, 2019; Szymanska, Blanchard & Kuhns 2019). On the contrary, literature also suggests that family businesses could possess advantages in terms of coping with changes, such as digital transformations, given their idiosyncratic characteristics tied to the firm (Reisinger & Lehner, 2015). Thus, family businesses could face both hampering effects as well as opportunities in relation to adapting to changes associated with a more digitalized business setting (Batt et al., 2020; Bennedsen & Foss, 2015).

However, digital transformation does not merely revolve around adopting new and improved technologies in the organization, it represents the process of how and when the change is implemented where the organization must act to reap the benefits associated with the digital era (Weill & Woerner, 2018). For family firms, it encompasses keeping a fine balance in maintaining and emphasizing non-financial aspects (Batt et al.,2020) whilst simultaneously finding avenues to successfully leverage transformations in order to thrive in a dynamic and everchanging business environment.

1.2 Problem Discussion

Research indicates that the diffusion and spread of digitalization and the associated disruptions change the way organizations conduct their operations (Schwarzmüller et al., 2018; Weill & Woerner, 2018). The rise of digital technologies, new innovative business ideas, and digital disruptions implies a need for change and calls for organizations to adapt accordingly (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Verhoef et al., 2019). Digital transformation stems from increased digitalization which emits into utilizing digital technologies, altercating business models and structures, subsequently entailing adaptation and changes in order to succeed and create value in the current business environment (Wrede, Velamuri & Dauth, 2020). Therefore, firms should find new avenues to successfully leverage digital transformations and tailor the organization to meet the challenges prevalent in the digital world (Weill & Woerner, 2018).

Nevertheless, characteristics that are common to family businesses such as handing down the business to future generations, family control and other critical non-financial aspects (Berrone et al., 2012; Miller & Le-Bretton Miller, 2005), could arguably signify

opportunities as well as inhibitory outcomes with respect to changes caused by digitalization (Batt et al., 2020; Bennedsen & Foss, 2015). Contemporary literature on how family businesses handle transformations is inconclusive. On one hand, various sources indicate that family firms have advantages when leveraging transformations as a result of their distinctive and unique pool of characteristics, such as high family presence and an idiosyncratic array of resources which for instance could yield access to social capital, tacit knowledge, and ease the decision-making process (Kotlar & Chrisman, 2019; Reisinger & Lehner, 2015). On the other hand, literature also suggests that family businesses tend to be disinclined and face several major challenges related to change due to reasons such as the fear of losing control over the business and diminishing their influence (Canterino et al., 2013; Ceipek, Hautz, De Massis, Matzler & Ardito, 2020; Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007). This could imply that specific family business dimensions, such as various non-financial aspects, could either hinder or ease how such firms adapt, confront and handle the corresponding changes brought forth by digitalization. Given the unique and distinctive attributes prevalent in family firms (Berrone et al., 2012; Poza & Daughtry, 2020), the interest in further exploring how family businesses leverage organizational change, and more specifically, digital transformations, has emerged. Also, current literature has neither acknowledged nor answered how family firms respond to the rise of more rapid changes due to digitalization and how such firms handle the subsequent process of digital transformations. Vardaman (2019) elaborates on this notion, claiming that research at the intersection of organizational change and family business remains heavily undeveloped where further refinement is needed. Considering that family businesses are a form of business that is incremental for the global economy (Basly & Hammouda, 2020), the topic becomes of great importance. Thus, providing an interesting and conducive gap in contemporary research.

Furthermore, the strong linkage and influence between the family and the firm itself normally influence how family firms conduct their business operations (Chrisman, Chua, De Massis, Minola & Vismara, 2016). Hauswald and Hack (2013) elaborate on this by claiming that through this close linkage, the value from SEW can be derived. This is something literature highlights as potentially affecting the behavior of the family firm, giving their aim to preserve and accumulate SEW (Schepers, Voordeckers, Steijvers and

Laveren, 2013). Prior research further suggests that SEW may inflict and shape the way family firms handle strategic initiatives in order not to damage or diminish SEW (Berrone et al., 2012; Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia & Larraza-Kintana, 2010). Therefore, the continuous prioritization and emphasis on non-financial aspects could potentially affect a digital transformation as well, as the SEW derived from different non-financial aspects influence how family firms handle various strategic initiatives and transformations (Cleary et al., 2019).

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this paper is derived from the problem identified from the existing literature as it has failed to provide sufficient knowledge and insights regarding the influence non-financial aspects may have on a digital transformation in a family business. Therefore, the purpose is to investigate how non-financial aspects could influence a digital transformation process in family businesses. In order to fulfill the purpose, this paper aims to answer the two research questions that have been outlined below:

(1) What non-financial aspects influence a digital transformation process in a family business?

(2) How do these non-financial aspects influence a digital transformation process?

1.4 Definitions

Digital transformation: “a change in how a firm employs digital technologies, to

develop a new digital business model that helps to create and appropriate more value for the firm” (Verhoef et al, 2021 p. 889).

Digitization: “the conversion of analog to digital information and processes in a

technical sense” (Loebbecke & Picot, 2015 p. 149).

Digitalization: “the use of digital technologies to change existing business processes” (Wrede, Velamuri & Dauth, 2020 p. 1550).

Change management: “the process of continually renewing an organization’s direction,

structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers” (Moran and Brightman 2001, p. 111).

Family business: “The family business is a business governed and/or managed with the

intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.” (Chua, Chrisman

& Sharma 1999, p. 25).

Socioemotional wealth: “non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s

affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty” (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, p. 106).

Familiness: “the unique bundle of resources a particular firm has because of the systems

interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business” (Habbershon

2. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter provides an overview of the theoretical background and relevant literature related to the topic of digital transformations in family businesses. Therefore, three main areas are covered, namely, digital transformation, change management, and family business. The chapter ends with a brief section integrating the three streams of literature.

______________________________________________________________________

The three main areas included in the frame of reference, which are depicted above, helps promote a well-grounded theoretical foundation to successfully investigate the topic at hand and fulfill the purpose. To ensure that the frame of reference is of high quality and provides a nuanced outlook for the topic of this thesis, the sources of information are mainly peer-reviewed journal articles and academic books. According to Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson and Jaspersen. (2018), such sources of information are commonly depicted as being of high-quality and appropriate for a research paper. Thus, enabling the researchers to answer the intended purpose and research questions in a suitable and reliable manner.

2.1 Digital Transformation

The emergence of new digital technologies and unconventional business ideas force many organizations and companies to transform digitally in order to be adaptive (Fitzgerald et al., 2014; Gfrerer, Hutter, Füller & Ströhle, 2020), and plays a vital role for the survival of the organization (Alonso et al., 2019). The term digital transformation is defined as “a

change in how a firm employs digital technologies, to develop a new digital business model that helps to create and appropriate more value for the firm” (Verhoef et al., 2021

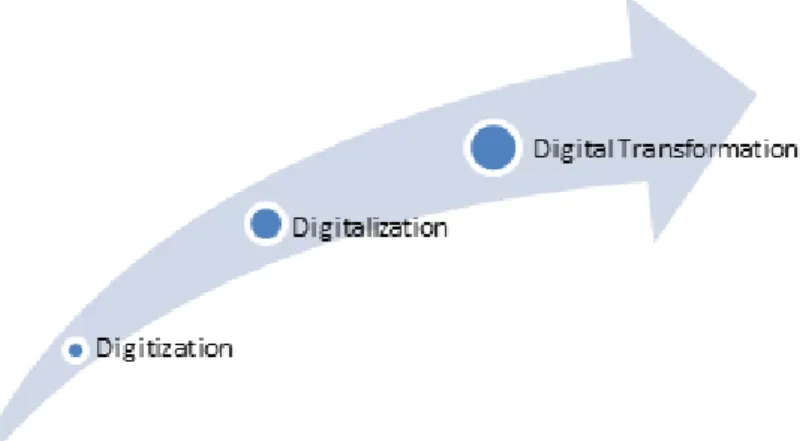

p. 889). Moreover, Verhoef et al. (2021) further argue that digital transformations consist of three phases, where the first two phases are digitization and digitalization, which creates the foundation for the final and last phase, namely the digital transformation. To illustrate the relation between the different phases, a figure is presented below (see Figure 1). The first phase, digitization, is defined as “the conversion of analog to digital

information and processes in a technical sense” (Loebbecke & Picot, 2015 p. 149). As

technologies, leading to changes in organizational processes (Wrede, Velamuri & Dauth, 2020). When simplified, it could be depicted as “becoming digital” (Gobble, 2018). The third and final phase is the actual digital transformation, which redesigns and affects the entire organization (Amit & Zott, 2001). As previously mentioned, digital transformation is when businesses develop a new business model by integrating digital technologies in their operations to generate more value (Pagani & Pardo, 2017; Shahi & Sinha, 2020). Furthermore, prior literature also argues that the main objective for businesses when undertaking digital transformations is to capture more value by being more competitive and adaptive towards new customer behaviors (Verhoef et al., 2021).

Figure 1 - Three phases of digital transformation

2.1.1 Incentives for Digital Transformation

Although existing literature emphasizes the importance of digital transformation to tackle digital disruptions and changes (Gfrerer et al., 2020), one cannot exclude the importance to have a unified vision and share the same objectives regarding digital transformations (Ivancic, Vuksic & Spremic, 2019; Yukl, 2013). Without a comprehensive understanding of the incentives behind a digital transformation, inconsistencies such as resistance to change could emerge, potentially hampering the process and resulting in unsatisfactory outcomes (Soluk & Kammerlander, 2021). Nevertheless, digital transformations are generally of unconventional nature and involve rapid fundamental organizational changes, such as changes in the business model, processes, strategies, as well as the firm’s products and services (Brosseau, Ebrahim, Handscomb & Thaker, 2019; Mugge, Abbu, Michaelis, Kwiatkowski & Gudergan, 2020). This could cause the vision of the digital

transformation to continuously change as well as creating an unpredictable future (Solberg, Traavik & Wong, 2020). Thereby, leading to a necessity for companies to evaluate the incentives of the digital transformation and only execute transformations of strategic character with a beneficial outcome (Shahi & Sinha, 2020).

However, dependent on the firm, there are various incentives for digital transformation (Matt, Hess & Benlian, 2015). For instance, the incentives can vary between generating more value (Pagani & Pardo, 2017) or simply leveraging digital transformations for the survival of the company (Alonso et al., 2019). Regardless, the incentives are, in most cases, developed from different key drivers, such as increased competition (Verhoef et al., 2021) or changes in consumer behavior (Kannan, 2017). Additionally, Covid-19 has also shown to be a major driver, with an immense impact on the urgency for digital transformations (Autio, Mudambi & Yoo, 2021; Lee & Trimi, 2021), causing digital transformations to accelerate even quicker (Belhadi et al., 2021). Hence, insinuating the importance for firms to be unafraid of structural changes and to have a strategic plan in place (Matt et al., 2015; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006). The strategy can alternate based on the nature of the firm and the desired outcome of a digital transformation (Ivancic et al., 2019). Furthermore, Schallmo, Williams and Boardman (2017) present five general phases commonly prominent in digital transformations. If properly understood, they could enhance the possibility to successfully execute digital transformations.

2.1.2 Five Phases in a Digital Transformation

The literature clearly shows how digital transformations involve fundamental changes of the entire organization (Brosseau et al., 2019; Shahi & Sinha, 2020). Many businesses tend to struggle with such crucial changes (Hinings, Gegenhuber & Greenwood, 2018), for instance, applying necessary modifications to the business model (Mugge et al., 2020). Initially, in accordance with the five phases outlined by Schallmo et al. (2017), it is important for a company to understand its digital reality by outlining its existing business model while analyzing relevant information regarding how the digital transformation would be beneficial and add value. Hence, companies need to be aware of the changes occurring in the digital era, such as new customer requirements and changed behaviors

(Verhoef et al., 2021), which could be embraced through an appropriate digital transformation (Westerman & Bonnet, 2015). This leads to the second phase, digital

ambition, which is derived from the digital reality and is the phase where new objectives

for the business model are set to fit the digital reality (Schallmo et al., 2017), something that Westerman, Bonnet and McAfee (2014) also claims to be an important factor for firms to consider in terms of digital transformations. Literature also argues that firms need to be ambitious and redesign the business model that coordinates with new opportunities and threats (O’Reilly & Binns, 2019), also known as the digital reality.

After the digital reality and digital ambition have become clear, the firm needs to establish and specify appropriate practices, thus finding their digital potential, and start to develop a suitable digital transformation strategy and a revised digital business model (Schallmo et al., 2017). The fourth phase, digital fit, is the phase where the firm evaluates the new digital business model and assures that it coincides with the three previous phases (Schallmo et al., 2017). It is important that the new objectives and customer requirements are included whilst simultaneously performing suitable activities and practices, as it enables firms to successfully deal with changes in the digital era (Gfrerer et al., 2020). Furthermore, the final phase of the digital transformation involves the actual implementation of the newly redesigned digital business model, the implementation

phase (Schallmo et al., 2017). An important and complex phase that firms need to

strategically manage (Verhoef et al., 2021) since the success of the whole digital transformation depends on the acceptance of the organizational members (Solberg et al., 2020). When considering different organizational changes, resistance towards changes commonly arises due to the absence of acceptance (Lines, 2004; Olafsen, Nilsen, Smedsrud & Kamaric, 2020), especially when dealing with digital transformations (Soluk & Kammerlander, 2021). Hence, creating an understanding of the importance of a well-functioning change management process in connection to the digital transformation (Ivancic et al., 2019; Mugge et al., 2020).

2.2 Change Management

Moran and Brightman (2001, p. 111) define change management as: “the process of

continually renewing an organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers”. As today’s business

environment is highly embossed with rapid changes at both the strategic- and organizational level, change has become more frequently occurring, which firms should seek to handle and manage (By, 2005). For organizations, change management plays an incremental role in dealing with the changes brought forth by a continuously disruptive, competitive, and ever-changing environment (Paton & McCalman, 2008). This notion is further elaborated as literature on the topic suggests that prosperous and successful transformations call for adequate change management, where appropriate actions and decisions need to be undertaken in order to steer the organization towards the desired state (Gfrerer et al., 2020). Literature also highlights that leadership and change management are highly correlated, implying that leadership is about handling, leveraging, and managing changes in an organization (Beerel, 2009; By, Burnes, Oswick, 2012). As leaders potentially can affect and influence other members in the organization in relation to change, it becomes necessary that leaders should strive to positively influence others as well as communicating the message of change to ensue successful efforts (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, 2006; Mugge et al., 2020).

2.2.1 Change Management Models

Existing literature highlights several models and frameworks which fill the purpose of guiding and helping organizations to tackle and implement change endeavors (Cameron & Green, 2019; Rosenbaum, More & Steane, 2017). Literature suggests that Kurt Lewin is one of the most prominent figures and theorists within change management, where he often is referred to as a “founding father” within this discipline (Cummings, Bridgman & Brown, 2016). Lewin brought forth the three-step model, a widely popular change management model that later laid the foundation for several other change models (Bamford and Forrester, 2003). The model revolves around three different phases and steps, (1) Unfreezing, (2) Changing and (3) Refreezing, where the initial step in the change process is constituted of creating an overall understanding that the organization must be changed and signify that old habits and behaviors are not working effectively

(Murthy, 2007; Schultz, 2010). The second step brings attention to the actual change and it is in this stage where the change is carried out. The second step further entails carefully crafting and identifying new behaviors, structures, and tasks which subsequently should be followed (Schultz, 2010). The last step revolves around establishing the new changes in the organization and aims to reduce the need to forgo what has been implemented by providing the necessary resources to support the new change (Murthy, 2007; Schultz, 2010). Nevertheless, central to this model is that the change entails moving away and abandoning old structures, processes and culture in order for the new change and behavior to be successfully implemented (Bamford and Forrester, 2003; By, 2005).

Furthermore, another widely popular and well-known change management model is John Kotter’s eight-step model (By, 2005; Mento, Jones & Dirndorfer, 2002). Kotter’s (1995) model is based on eight steps that enable the organization to transform successfully. Kotter (1995) states that the goals of the examined companies in his study are derived from the need to change in accordance with their environment, however, many change efforts fail. Many of these failed change efforts are a result of not establishing a proper vision for the change nor creating a sense of urgency within the organization (Kotter, 1995; Kotter, 2012). Mento et al. (2002) further state that the two key points derived from this model are that the change process itself undergoes several stages where mishaps in any step could inevitably lead to failure of the entire process or undermine its effect. The model is summarized in Figure 2, where a description of every step is outlined. Nonetheless, Appelbaum, Habashy, Malo and Shafiq (2012) argue that, despite the majority of the eight steps are supported by existing research, the model as a whole lacks a solid scientific foundation. However, the authors still state that the model is a valid and useful tool when implementing change.

2.2.2 Resistance

Whilst assessing the literature regarding change management, resistance is a topic within the discipline that has received a great extent of attention and it commonly concerns an individual’s resistance to various change efforts, creating barriers to successfully leverage organizational change (Mathews & Linski, 2016; Thomas & Hardy, 2011). Despite change being necessary in order to remain competitive and adapt to new realities, organizational members’ resistance plays a vital role in why change efforts fail (Mathews & Linski, 2016). Resistance towards organizational change can stem from both the individual member’s perception and attitudes, as well as resistance from the organization itself and its leaders (Michel, By & Burnes, 2013). Literature distinguishes several factors and causes that could yield resistance to change from the perspective of organizational members. Dent and Goldberg (1999) describe that, organizational members do not necessarily resist the change effort itself, but rather the consequences of the change, such as losing one’s job, diminishment of status, or loss of comfort. The authors further list twelve reasons why resistance could occur, all of which are indicated below.

1. Surprise 2. Inertia

3. Misunderstanding 4. Emotional side effects 5. Lack of trust

6. Fear of failure 7. Poor training

8. Threat to job status/ security 9. Work group breakup

10. Fear of poor outcome 11. Faults of change 12. Uncertainty

Palmer, Dunford and Buchanan (2017) discuss a wide range of causes for resistance linked to change in organizations. The authors highlight several sources and reasons for resistance, some of which coincide with the thoughts brought forth by Dent and Goldberg (1999). However, Palmer et al. (2017) denote that resistance could result from change

that threatens the organizational identity. As the organizational identity constitutes of what the organizational members believe is central, distinctive and fundamental to the specific organization, resistance can arise due to the fact that the change contradicts with the beliefs and fundamental assumptions of the organization in the eyes of its members. Moreover, resistance might also originate from organizational members not perceiving the change as appropriate or necessary for the organization (Self & Schraeder, 2008). As stated by Palmer et al. (2017, p. 257) “change, as a key component in the enactment of

strategy, can thus expose widely divergent views of how to achieve that vision”. Hence,

the authors imply that one reason why individuals do not perceive the change as appropriate, right, or necessary could be since organizational members have different visions for the organization and so forth view the change in dissimilar ways, which could yield resistance.

2.3 Family Business

Family businesses have been widely researched in contemporary literature, however, a common definition has yet to be established. For the purpose of this study, family business will be defined in accordance with the definition provided by Chua et al. (1999). The family business is a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families. (Chua et al., 1999 p. 25)

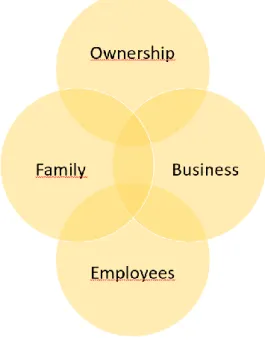

Literature highlights that family firms operate at the intersection of the work system and family, where family members influence strategic decisions and visions for the organization (Melin, Nordqvist & Sharma, 2013). Habbershon and Williams (1999) further denote that the relationship and intersection of the family and the business itself entails behaviors and complexities often significant to family firms. This is further elaborated by Chua, Chrisman and Steier (2003), who state that The Three Circle Model (see Figure 3) has been at the forefront in explaining the intricacies within a family business. The model consists of three reciprocal components, namely the business, the family, and ownership. According to Gersick, Lansberg Dunn (1999), the Three Circle Model assumes the family business as a complex entity where the previously mentioned

dimensions, here denoted as subsystems, intersect with one another. Gersick et al. (1999) further highlight that this model could help to understand the family business dynamics and how such organizations function. Nonetheless, in relation to what has been described above, Poza and Daugherty (2020) highlight several characteristics that sum up to the distinctiveness and uniqueness of family, that is, what makes them inherently different. The authors state five reasons for this, (1) Family presence, (2) the overlap of management, ownership, and family, (3) The emphasis put on family-specific values and non-financial goals, (4) Keeping the business within the family across generations and (5) distinguished sources for competitive advantages, such as long-term horizon which is derived from the overlap between the subsystems. In the next section, this paper will elaborate on the uniqueness of family firms to yield a more thorough understanding of the complexities associated with family businesses.

2.3.1 Familiness

Aforementioned, family businesses generally possess certain characteristics, for instance, distinguished goals, traditions, and values which are a priority for the family (Canterino et al., 2013). Typically, family businesses tend to concentrate the business operations towards their defined long-term goals, many of which are of non-financial nature, involving a high level of emotion and commitment from the family (Chirico & Salvato, 2008). According to Chrisman et al. (2013), the objectives of the non-financial goals could, for instance, be to keep the business within the family and maintain influence over the organization, thus shaping the distinctive characteristics and behaviors apparent in family firms. Although the non-financial goals could vary among different family firms, research implies that they are closely interconnected with the accumulation of socioemotional wealth (Chrisman & Patel, 2012), where socioemotional wealth briefly entails “the non-economic utility family business owners derive from their business” (Cleary et al., 2019 p. 120). Thus, this may explain the reason why family firms allocate a considerable amount of resources to fulfill non-financial goals (Daspit, Chrisman, Sharma, Pearson & Long, 2017; Naldi, Cennamo, Corbetta & Gomez–Mejia, 2013).

Given the well-defined emotional relationship to the business in family governed firms, a more complex and distinctive business setting emerge (Daspit et al., 2017; Eddleston & Morgan, 2014; Ingram, Kraśnicka & Głód, 2020), involving close linkages between the family and the actual business, commonly referred to as familiness (Frank, Kessler, Rusch, Suess–Reyes & Weismeier–Sammer, 2017). Habbershon and Williams (1999 p. 11) further define familiness as “the unique bundle of resources a particular firm has

because of the systems interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business”. Prior literature argues that familiness has an impact on the operations and the

functioning of the family firm (Habbershon & Williams, 1999; Moores, 2009). Family firms’ significant characteristics and incentives are influencing the way such firms do business (Chrisman et al., 2016), especially as the family members perceive the actual business as an extension of the family (Memili, Eddleston, Kellermanns, Zellweger & Barnett, 2010). Nevertheless, Beech, Devins, Gold and Beech (2020) argue that familiness influences what non-financial aspects family firms prioritize to accumulate and preserve SEW.

2.3.2 Socioemotional Wealth (SEW)

Literature within the field of family business has drawn particular attention to socioemotional wealth, SEW, as an important aspect whilst studying family businesses (Berrone et al., 2012; Clearly et al., 2019). Literature highlights that family businesses strive to pursue non-financial goals, sometimes disregarding feasible economic purposes, in order to achieve and maintain their SEW (Kammerlander & Ganter, 2015). Research further suggests that SEW is particularly important for family firms, showcasing itself in various forms within family businesses, for example, sustaining family dynasty, being able to exercise control, maintaining family specific-values, and governing social capital (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007 p. 106) further provide a definition, where they refer to SEW as: “non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s

affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty”. Furthermore, Berrone et al. (2012) indicate that SEW

is one of the most influential factors in determining why family businesses behave and act distinctively and differently, hence implying that SEW is what makes family businesses unique. The SEW paradigm is argued to be of uttermost importance for the family business, where its value is derived from the close relationship between the business identity and family (Hauswald & Hack, 2013). Schepers et al. (2013) further argue that SEW might affect family firm behavior as they typically wish to preserve SEW, leading to the firm’s behavior being altered. As the family tends to prioritize keeping control over the organization as well as influencing the daily operations, research indicates that such behaviors are directly related to maintaining their SEW (Vardaman & Gondo, 2014). According to Berrone et al. (2012), the owner-family might allow for actions and decisions that have no financial denomination in order to successfully preserve SEW and its subsequent endowments, especially if the socioemotional endowment is under threat. The socioemotional endowment can briefly be described as the value that the family derives from owning and controlling the business, such as asserting family influence and maintaining a family identity (Berrone et al., 2012). However, according to Zellweger (2017), family businesses might be inclined to accept SEW losses if they face vulnerability, for instance, performance decline and the overall threat to the survival of the organization. Such situations of vulnerability may lead family businesses to initiate change efforts, become more risk-inclined and hence, disregard SEW to a greater extent.

Research has provided empirical evidence for the concept of SEW, linking how it could affect various business outcomes and its overall importance in family businesses. Gomez-Mejia, Makri and Larraza-Kitana (2010) provide evidence that strategic decision making and diversification are affected by SEW. They further state that family businesses struggle to balance SEW and diversification decisions such as investing in innovation as it could bear a higher risk of diminishing SEW. Considering this, Berrone et al. (2012) also demonstrate that studies have indicated that family businesses tend to diversify less in terms of technology as it could impose damage to SEW. Moreover, Berrone et al. (2010) describe how firms controlled by a family pollute less than their counterparts in industries generally seen as major polluters in order not to damage the family reputation and image, or rather, its SEW. Nonetheless, Kellermanns, Eddleston and Zellweger (2012) suggest that SEW may impose a dark side. The authors argue that when family businesses pursue SEW, family needs are valued higher which could lead to negligence of non-family stakeholders. SEW and its associated dimensions, such as family firm identity, could then imply that family members disregard other interests, especially the ones that involve other stakeholders besides the family itself (Kellermanns et al., 2012).

Furthermore, the literature has tried to conceptualize SEW and its dimensions adequately (Swab, Sherlock, Markin & Dibrell, 2020). The seminal work by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007), whose viewpoints have been outlined above, provides a good starting point in understanding the concept of SEW. However, Swab et al. (2020) argue that the FIBER conceptualization by Berrone et al. (2012) is the most influential framework in explaining SEW and its dimensions. Cleary et al. (2019) describe that the FIBER is suitable for observing SEW within a family business since it is based on prior research. The first dimension, family control and influence, refers to the influence and control that the family exercises within the organization. This could be through both informal and formal influence and control over the organization’s affairs and decisions (Berrone et al., 2012). The second dimension, family members’ identification with the firm, commonly perpetuates through the family name where the firm is viewed as an extension of the family itself in the eyes of external and internal stakeholders, such as the employees. It could imply that both the internal and external image and reputation need to be maintained as the family might be sensitive to such aspects (Swab et al., 2020). The third dimension,

binding social ties, can briefly be described as the social relationships developed from

social capital and kinship where the ties are demonstrated both within the family, but also with other stakeholders. These ties and relationships usually transcend to the employees, creating a sense of belonging and commitment to the organization despite not being a part of the family (Berrone et al., 2012; Swab et al., 2020). Emotional attachment, the fourth dimension, refers to the emotions involved in the family business where aspects such as security, belonging, and involvement play an incremental role, thus, potentially affecting and influencing business decisions (Berrone et al., 2012). The last dimension, renewal of

family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession, signifies that the family business

wants to keep the business within the family and hand it down to future generations, i.e., succession., which is a clear non-financial goal prevalent for family firms (Berrone et al., 2012). The FIBER dimensions are highlighted in Table 1 below with a brief description.

Table 1 - The FIBER dimensions (Cleary et al., 2019 p. 120)

2.4 Organizational Change in Family Businesses

According to Basly and Hammouda (2020), family businesses are commonly told to favor stability to change over rapid and more disruptive changes. However, literature found in the field of family business is rather inconsistent whether family businesses possess advantages or disadvantages when dealing with change given their specific nature which they operate under or are influenced by. Kotlar and Chrisman (2019) illustrate that family businesses could face major challenges when dealing with change as a result of the family involvement inflicting the change process. The authors further state that family businesses

have a propensity to be loss averse in terms of SEW and therefore show a tendency to maintain the status quo which might hamper organizational and strategic change. This notion is further elaborated by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007) who argue that adopting and changing processes within the family business might be difficult as it might entail changes in the status quo. In relation to this, Szymanska et al. (2019) also bring forth similar viewpoints, stating that family businesses could become discontented from implementing change as the family might lose control over the organization. Chirico and Salvato (2008) denote that family businesses often are disinclined to pursue change, even though the change being highly anticipated and needed. They argue that it could stem from the high level of emotions and feelings from the family members in relation to the organization, thus creating resistance to change.

On the contrary, family businesses could possess advantages and experience great opportunities when dealing with change given their unique alignment of characteristics (Canterino et al., 2013). According to Batt et al. (2020), family businesses have esteemed decision-making power, high flexibility, and autonomy which serves to provide such organizations with greater advantages when leveraging transformations. Zahra (2005) argues that family firms, given their unique governance structure, easily can overcome inertia whilst simultaneously taking rapid and resolute decisions, hence leading to implementation of change in an effective and timely manner. It is further understood that family businesses, due to family involvement, can yield access to valuable resources such as reputation, social capital, and knowledge, leading to change management efforts becoming easier to handle and leverage (Kotlar & Chrisman, 2019). The same authors also highlight that family businesses could, if facing threats against the survival of the firm, forgo non-financial goals and other family intrinsic values to initiate change efforts. However, research in the intersection of family business and organizational change is argued to remain largely underserved where additional literature and further academic inquiry is needed (Vardaman, 2019).

2.4.1 Digital Transformation in Family Businesses

As outlined above, existing literature is contradictory as to whether family firms possess advantages or disadvantages regarding the process of organizational changes. As family businesses operate in different industries and pursue different non-financial goals in order to accumulate SEW, a variance may occur among family firms as well (De Massis, Wang & Chua, 2019). According to Verhoef et al. (2021), companies tend to enter collaborations with competitors in order to be more adaptive when addressing the constant appearance of new digital technologies and innovative business ideas. Although external collaborations could be beneficial for family firms as well, they usually disregard the opportunity, leading to more inadequate transformations (De Massis, Frattini & Lichtenthaler, 2013; Fitz‐Koch & Nordqvist, 2017). This is due to the family firms’ tendency to see various external collaborations as threats to the family’s influence on the business, i.e., SEW (Frank et al., 2017; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Accordingly, the constant interaction between additional factors apparent in family businesses, the three-circle model, could increase the complexity for family firms to manage digital transformations as well (Claßen & Schulte, 2017; Frank, Lueger, Nose & Suchy, 2010). Furthermore, due to the fear of losing control over the business, family firms tend to mainly pursue digital transformations that do not endanger the family’s SEW, causing them to forgo certain digital transformations that potentially could be beneficial (Ceipek et al., 2020). Nonetheless, it could be particularly important for family firms to understand a digital transformation’s different phases and utilize suitable change management strategies and actions as guidance to handle this type of complex transformation. However, as SEW and its interconnected non-financial goals and aspects are the basis for why and how family governed firms do business and manage transformations (Cleary et al., 2019), it may entail that change management and digital transformation strategies and actions need to be attuned in relation to the family firms’ non-financial aspects and goals.

3. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter presents the research method and methodology applied, describing how the research was conducted. Initially, the section elaborates on the research philosophy, design, approach, and strategy, followed by the data collection and data analysis. Thereafter, a description regarding the research quality insurance is presented together with the ethical considerations that have been applied.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy serves as the foundation of the entire research process, influencing the research design and acting as a contributing factor to the coherence and overall quality of the research (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The philosophical standpoint is derived from the researcher’s views and assumptions about the nature of reality (Collis & Hussey, 2021). According to Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), there are two epistemologies that are the most common, namely positivism and social constructionism. The former entails interpreting and understanding the gathered data objectively, without any influence from humans (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2016). On the contrary, social constructionism displays the reality as socially constructed and that it is influenced by human interpretations (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The researchers of this thesis have a philosophical standpoint in accordance with the latter, social constructionism. As this study aims to explore how non-financial aspects could influence a digital transformation process in family businesses, the researchers’ philosophical stance assumes that several views could be present, and the reality is determined by the participants’ knowledge and experiences. Furthermore, according to Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), the philosophical position of social constructionism also indicates that the researchers’ interaction and interpretation influence the determination of the reality as well. Additionally, social constructionism is a subcategory of interpretive methods, which corresponds with the researchers’ ontological approach of relativism, where several truths may exist that could differ depending on which perspective they are being observed from (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the philosophical position aligns with this thesis’ intention to provide a comprehensive understanding regarding the topic. The empirical data collected will yield insights from several perspectives since the non-financial aspects prevalent in family firms generally differ due to for instance operating in various industries, having different values and visions (De Massis et al., 2019). This further coincides with the epistemological standpoint since social constructionism emphasizes the fact that people possess different knowledge and experience, therefore, think in dissimilar ways (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence, allowing the researchers of this thesis to analyze the influence of non-financial aspects on digital transformations in family firms from different perspectives.

3.2 Research Design

According to Ghauri, Grønhaug and Strange (2020), the focal difference between quantitative research and qualitative research is the fact the former revolves around procedures for quantification and various statistical methods to conduct research. The latter, qualitative research, entails a different approach where the focus is rather on utilizing non-numerical data to gain a comprehensive understanding of the given topic (Saunders et al., 2016). As this thesis seeks to yield a deeper understanding of the subject of digital transformations in family businesses, a qualitative research design has been applied. The nature of a qualitative research design is in line with the researchers’ philosophical positioning and given the need to understand how the topic at hand unravels, where research is sparse, a qualitative approach is appropriate (Ghauri et al., 2020; Saunders et al., 2016). Furthermore, Saunders et al. (2016) highlight four purposes for the research design, namely exploratory, descriptive, evaluative, and combined studies. However, for the purpose of this thesis, an exploratory study is appropriate as this thesis seeks to interpret “how” non-financial aspects influence digital transformations in family businesses, since the nature of this specific topic is largely unknown. Moreover, as exploratory studies typically are used in order to gain new and fruitful insights as well as gain deeper knowledge of the phenomena, it becomes highly suitable for this thesis (Saunders et al., 2016).

3.3 Research Approach

Literature distinguishes three major approaches to theory, deductive, inductive, and abductive, where every individual approach takes a different stance towards developing theory in a research paper (Saunders et al., 2016). This thesis follows an inductive approach as the paper is of exploratory nature, where the researchers seek to draw generalized conclusions derived from the empirical evidence rather than testing preexisting theories. As an inductive study entails drawing conclusions from the empirical observations where qualitative research typically is utilized (Ghauri et al., 2020), this approach could therefore be argued to be adequate and suitable. Also, an inductive approach lets the research emerge from vital themes derived from the data, something that is in line with the reasoning and the scope of this paper (Saunders et al., 2016; Thomas, 2006). In relation to this, albeit extensive literature being found in certain specific contexts, i.e., family business, there is arguably a lack of research addressing the narrower scope pertaining to the research questions of this thesis where more contexts are included. Thus, utilizing preconceived theories and testing them or rather following theory to generate data, such as with a deductive approach, will not be suitable for the purpose of this thesis (Saunders et al., 2016). This standpoint could be true for an abductive approach as well, since it entails providing a modified or new theory that should be tested which is not the intention in this study. Furthermore, Saunders et al. (2016) argue that the approach of a deductive study entails that the conclusions brought forth through the research should be considered true when premises are also true. However, as this study seeks to understand how non-financial aspects could influence digital transformations in family businesses, one could argue that the logic will differ as the paper will derive conclusions that will yield various and alternative explanations to the phenomena. These explanations may then differ depending on the respondent’s interpretations. Thus, aligning with an inductive approach that resonates with the researchers’ philosophical assumptions.

Nonetheless, it is hard to forgo the fact that prior literature will help and act as guidance when analyzing the empirical data, implying that an inductive approach will not be solely pursued as some dimensions that are prevalent for deductive and abductive reasoning are present. However, as this research seeks to draw generalized conclusions regarding the phenomena and not to test theories, it can be argued that an inductive approach is most

suitable. Hence, guiding the thesis to develop a comprehensive understanding of the topic at hand.

3.4 Research Strategy

The research strategy represents the methodology to acquire relevant data to fully investigate and answer the purpose of the thesis (Saunders et al., 2016). As this is a qualitative study with an inductive approach, investigating a rather unexplored area, a case study is argued to be appropriate (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). However, for the purpose of this thesis, a multiple case study design has been implemented since it enables the collection of more comprehensive data, generally implying a more thorough understanding about the research topic (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Also, a multiple case study approach is commonly considered to be more robust compared to single case studies (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Yin (2018) further suggest that, if possible, a multiple case design is preferable over a single case design, as it allows to more easily find patterns and relationships within as well as across the different cases.

Furthermore, as family businesses tend to be dissimilar (De Massis et al., 2019), a multiple case study enables the possibility to clearly define findings that are not only apparent in one specific case (Yin, 2018). Therefore, by using a multiple case study design, the researchers were able to interview several individuals with significant roles regarding different digital transformation processes in family firms from various industries. Although multiple case studies are commonly more correlated with a positivistic philosophical position (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018), the study design supports and facilitates this research’s purpose, to obtain a deep understanding about the subject and to subsequently provide compelling answers to the research questions.

3.4.1 Case Selection

Whilst assessing the chosen cases, it is important to have an adequate sampling strategy in place since it enables the researchers to draw conclusions and more general statements derived from the collected empirical data, hence influencing the overall quality of the paper (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). For the purpose of this thesis, a purposive sampling

design has been implemented. Given that it is a sampling technique that aligns with a non-probability sampling design, it implies that the researchers carefully need to choose cases where one’s judgment plays a critical role in determining suitable cases and respondents to be included (Saunders et al., 2016). Therefore, the cases in this multiple case study, which are different family firms, were selected based on a few eligibility criteria guided by both theory and judgment as well as suitable definitions derived by the theoretical background. The selected companies had to be considered small and medium-sized companies located in Sweden, as they are of particular importance, accounting for nearly 99,9 percent of the total number of companies in Sweden (Tillväxtverket, 2021). Furthermore, the companies needed to be defined as family business who has or currently is going through a digital transformation. Additionally, to ensure that potential patterns and relationships are associated with family firms, the dimension and context of family businesses are held constant, while the industry varies among the selected companies. This enables the researchers to observe the phenomena from different perspectives, which goes in line with the interpretive philosophical positioning of relativism and social constructionism as well as yielding a fruitful and representative outlook pertaining to the topic at hand. (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

According to Yin (2018), the number of cases in a multiple case study design should be broad enough with necessary variation to ensure a robust base, which later supports the validity of the findings drawn from the collected data. To identify adequate companies, the researchers initially consulted with contacts in well-established business networks to gain professional suggestions of potential candidates. Thus, different family firms were selected, where the definition provided by Chua et al. (1999) was used to determine whether the companies in fact could be considered as a family business. Furthermore, the CEO was contacted in order to confirm that the suggested family firms have or are going through a digital transformation that fits Verhoef et al. (2019)’s definition of digital transformations. Hence, when confirming that the companies fulfilled the eligibility criteria, four family firms were selected from different industries with some variation in the business setting.

3.4.1.1 Case A

Case A is a second-generation family-owned business founded at the beginning of 1980, which started as a distributor of high-quality shoe care products, now focusing on shoe accessories as well. The company is today one of the biggest actors within the industry of shoe accessories in Scandinavia. The family has far-reaching professional expertise and knowledge in terms of shoe care and shoe accessories, a contributing factor for their leading position in the industry. The firm has in between succession been partially owned by a major retail conglomerate, controlling fifty percent of the company and the family owning the rest. The current owner and second-generation successor bought back fifty percent and today owns seventy-eight percent, where the rest is owned by two other employees in the company.

3.4.1.2 Case B

The second family firm is a retailer of machinery, tools, and other accessories for cutting processing and welding within the engineering industry. The company has served the entire Scandinavia with machinery and tools for over 100 years, and the family governed firm continuously grows and has increased its revenue for each and every year. The firm is fully owned by various family members, where some are still present in the day-to-day operations and some being solely in the board.

3.4.1.3 Case C

Case C is a family business that is active within the food, catering, event, and production industry. It is currently operated by the second generation of family members, where the first generation and founders still are active within the firm. Furthermore, it is understood that since its birth, the company has grown tremendously and expanded its services to a widespread of areas. The family firm targets both businesses as well as private consumers, making it one of Sweden’s biggest catering firms. The ownership is centered around three family members who together own a hundred percent of the parent company. The family also has several subsidiaries which they fully own or have the majority in.

3.4.1.4 Case D

The fourth family firm was founded approximately 60 years ago, where its operations revolve around managing and owning properties. The real estate company rents out apartments, offices, and retail space to consumers and businesses alike. The governing body is run by a third-generation family member where the emphasis is still highly concentrated on developing their hometown in various ways, for instance, supporting local initiatives and clubs. Several family members, including the CEO, are active in the company and the rest are present in the board which only consists of family members and one external board member.

3.5 Data Collection and Data Selection

As previously mentioned, the purpose of this study is of exploratory nature through an inductive approach that builds on non-numerical data. According to Saunders et al. (2016), semi-structured interviews are suitable for qualitative research of exploratory nature as it is a more flexible approach facilitating for the researchers to obtain more open-ended qualitative data. Hence, the data collected is mainly primary data, gathered through semi-structured interviews in each of the cases, which is suitable for this thesis and could result in new insights about the phenomena (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). However, secondary data has also been integrated into the research, for instance, information from the websites of the companies. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with approximately three to four participants from each company, with one exception. The interviewees had different positions in the family firm, where all participants had a linkage to the company’s digital transformations. This allowed the researchers to align the collection of empirical data with the philosophical position of social constructionism and relativism, where the reality is determined by both the perspective of the participants as well as from which perspective the participants are being observed from (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). This could imply that depending on the interviewee’s experience and knowledge as well as the researchers’ interpretation, the same subject within the research scope could be seen differently and with opposing views.

In terms of selecting appropriate interviewees, these individuals were included mainly due to their position at the company and their involvement in a digital transformation as