Ambidexterity facilitated

through Knowledge

Sharing Mechanisms

MASTER THESIS

WITHIN: Business Administration

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Ambidexterity facilitated through Knowledge Sharing Mechanisms Authors: Marc Ottenthal and Pedro Magnani

Tutor: Ziad El-Awad Co-Grader: Duncan Levinsohn Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Ambidexterity, Knowledge Sharing, Embedded Knowledge, Single Case Study, High-Tech Industry

Abstract

Background: Surviving in times of rapid technology changes requires quick adaptability of processes in companies. Facilitating ambidexterity can be an integral part of the overall organizational goal and the strategy on a firm level, enabling companies to adapt to the rapidly changing environments. The current body of ambidexterity literature has been very much focused on how we can facilitate parity between those two orientations. However, there is limited understanding on how they can utilize knowledge sharing between those orientations mentioned above. Purpose: Analyzing how successful knowledge sharing mechanisms are institutionalized, this study aims to advance the understanding behind the linking mechanism to manage and implement ambidexterity in mature companies and new ventures.

Method: We conducted a single-case analysis with embedded multiple-units design of explorative- and exploitative-oriented teams in a listed Swedish high-tech company. We administered semi-structured interviews based on non-probability purposive sampling. The primary data was coded following the principles of thematic analysis.

Conclusion: The knowledge sharing mechanism we identified requires the routinization of (1) a strong knowledge sharing company culture, (2) knowledge brokers as linkage, and (3) moderating mechanisms defining the boundaries in alignment with company strategy where knowledge is allowed to flow freely.

Implications: Our findings indicate that routinizing knowledge sharing mechanisms offers an extension towards structural ambidexterity since it lowers resource requirements to alleviates tensions and amplifies synergies. Towards practitioners, it offers a novel and resourceful approach of implementing ambidexterity for new ventures and mature companies.

Acknowledgments

Sic parvis Magna – big things from small origins.

This master thesis would not have happened if we did not decide to leave our family and friends from our home countries to pursue this Swedish adventure.

During those two years in Jönköping, we made new friends at JU who were facing the same battles as us. Having like-minded people pursuing the same goal motivated us to stay focused on our end goal, although, as we learned during this journey, the end goal is

never the end goal. Sharing knowledge with them has proven to have a greater impact on

ourselves than any type of formal learning.

In addition, when the thesis semester finally arrived, this close group of friends managed to create a collaborative writing environment at “Das Studio”.

Our special acknowledgment goes to Ziad El-Awad, who provided fruitful insights on how we should “kill our darlings” in order to achieve something truly great. He challenged us to apply critical thinking while approaching our research question. We were impressed by the amount of time that he dedicated to offering fair and constructive feedback. Without him, this thesis would not be the same.

This thesis also would not have happened if we did not have passionate people from our thesis company to interview. We were surprised by how many people were willing to talk about topics that they like. What we perceived as the most challenging part of the thesis turned out to be the most enjoyable one.

Lastly, thanks to our proofreader Jacqueline who gave us her valuable influx of inspiration.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ... iv

List of Figures ... vi

List of Tables... vi

1

Introduction ... 7

1.1 Purpose ... 10 1.2 Thesis Outline ... 112

Literature Review ... 12

2.1 Ambidexterity ... 12 2.1.1 Forms of Ambidexterity ... 132.1.2 Critical Assessment of Ambidexterity Forms ... 17

2.2 Knowledge ... 18

2.2.1 Explicit and Tacit Knowledge ... 19

2.2.2 Knowledge Utility ... 20

2.3 Understanding Knowledge Sharing ... 21

2.3.1 Dimensions of affirmative knowledge sharing ... 21

2.3.2 Cognitive Ability ... 22

2.3.3 Motivations ... 22

2.4 Intra-firm knowledge sharing and company culture ... 23

2.5 Operationalizing Knowledge into the organization ... 25

2.6 Literature Synthesis ... 27

3

Research Methods... 29

3.1 Methodology ... 29 3.1.1 Philosophical Stance ... 29 3.1.2 Research Approach ... 30 3.1.3 Research Instrument ... 30 3.2 Chosen Case ... 313.3 Data Collection Method ... 32

3.3.1 Selection of Participants ... 33 3.3.2 Data Collection ... 34 3.3.3 Interview Structure ... 34 3.3.4 Primary Data ... 35 3.3.5 Secondary Data ... 36 3.4 Research Quality ... 37

3.4.1 Adjustments during the Data Collection process ... 38

3.5 Research Ethics ... 40

3.6 Data Coding and Analysis ... 41

3.6.1 Thematic Analysis ... 41

4

Findings ... 46

4.1 Prologue ... 46

4.2 Team Level Knowledge ... 47

4.2.1 Team Member Traits ... 47

4.2.2 Embedded Knowledge ... 47 4.2.3 Team Orientation ... 48 4.2.4 Knowledge Awareness ... 50 4.2.5 Knowledge Origin ... 51 4.3 Company Culture ... 53 4.3.1 Values ... 53 4.3.2 Self-Governance ... 53 4.3.3 Transparency ... 54

4.3.4 Promote Social Activities ... 55

4.4 Knowledge Brokerage ... 55

4.4.1 Linking Individuals and Teams ... 55

4.4.2 Shared Tools ... 57 4.4.3 Channel ... 57 4.5 Corporate Strategy ... 58 4.5.1 Strategic Alignment ... 58 4.5.2 Enabling Structures ... 59 4.5.3 Common Language ... 60 4.5.4 Moderating Relationships ... 62

5

Analysis ... 64

5.1 Knowledge Assessment ... 645.1.1 Team Member Traits ... 64

5.1.2 Embedded Knowledge ... 66 5.1.3 Team Orientation ... 67 5.2 Knowledge Synchronization ... 68 5.2.1 Company Culture ... 68 5.2.2 Knowledge Broker ... 69 5.3 Corporate Moderator ... 71 5.3.1 Strategic Alignment ... 72 5.3.2 Moderating Relationships ... 72 5.3.3 Enabling Structure ... 73

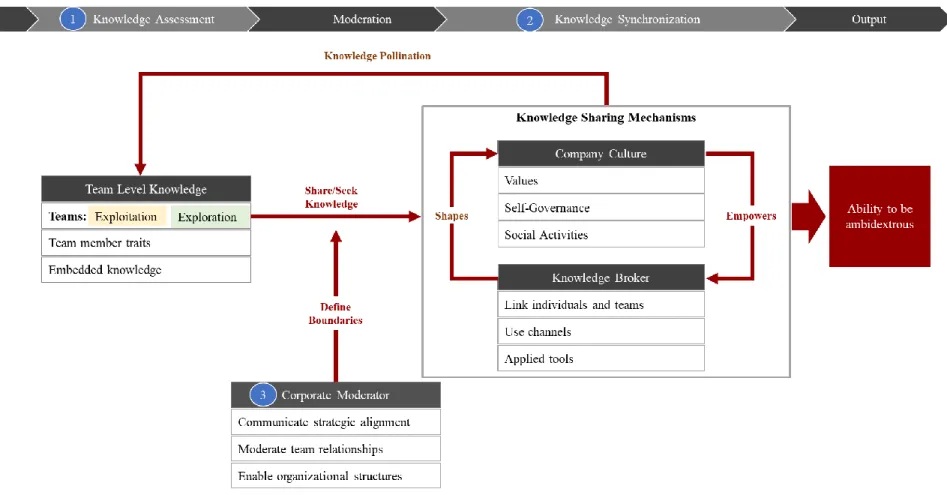

5.4 Knowledge Sharing Mechanism – the Model ... 74

6

Conclusions ... 78

7

Implications ... 80

7.1 Theoretical Implication ... 80

List of Figures

Figure 1 – Sender/Receiver Model of Communication ... 21

Figure 2 – Multilevel learning mechanism ... 26

Figure 3 – Literature synthesis of ambidextrous activities and knowledge sharing ... 28

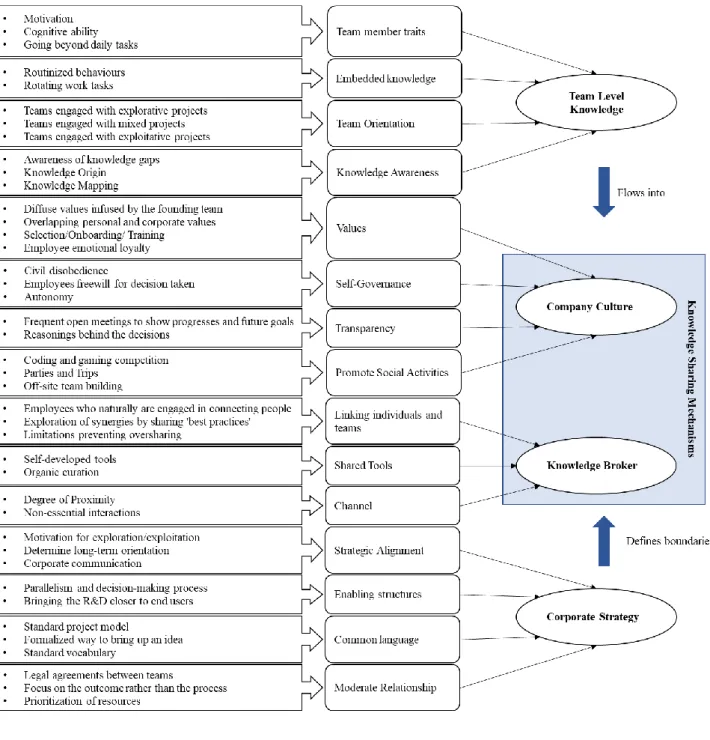

Figure 4 – Codes-to-theory model ... 43

Figure 5 – Data Structure ... 44

Figure 6 – Conceptual framework for routinizing knowledge sharing mechanisms ... 75

List of Tables

Table 1 – Interview participants ... 36Table 2 – Challenges in developing rapport ... 39

Appendix

Appendix A – Interview Protocol ... viiAppendix B – Sample of Saldana’s suggestion of coding ... viii

1 Introduction

In this chapter, we will introduce the concept of ambidexterity – the ability of organizations to balance exploration and exploitation strategies. Whereas prior research suggests developing multiple organizational structures as a facilitator of ambidexterity, we propose knowledge sharing as an alternative view.

Given the current momentum in which technologies become obsolete in an eye-blinking fashion, the dominant business logic is continuously challenged by the changing environment. With it, the strive for gaining a competitive edge is on an all-time high. Engaging in actions to make organizations resilient to rapidly changing environments is a theme that we have seen throughout business history. References can be found in cases such as Toyota’s vertical integration (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000) or Hewlett Packard’s market orientation shifts (Boumgarden et al., 2012). Restructuring organizations is another avenue which companies have been taking to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Restructuring organizations manifests in structural separation, as seen in Google into Alphabet (Page, 2015) or structural reintegration, such as Ubisoft (Chiambaretto et al., 2019).

Managing knowledge sharing within the company can play a fundamental role in facilitating those structural reorganizations, which improved companies’ adaptability (Ott et al., 2017). Evidence can be found at Fujifilm/Astalift (Komori, 2015) and Kodak (Wang et al., 2018).

Resonating with rapid social and technological change, the field of ambidexterity research tries to appease the understanding of what enables companies to adapt to the changing

The attempt to reconcile the differing organizational approaches to the challenges of exploitative and explorative activities, where tensions reside in the duality of the requirements, has been ongoing in the academic realms (Turner et al., 2013).

Ambidexterity research points out three forms of tensions. Firstly, tensions arising from the cognitive strain on an individual level (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016). Secondly, tensions arising from the competition for finite resources (both tangible and intangible) between the competing roles of exploration and exploitation (Carmeli & Halevi, 2009). Thirdly, tensions resulting from structural demarcations (O’Reilly et al., 2009). This is contingent upon successfully dealing with the arising tensions of an explorative and exploitive orientation while acknowledging the necessary dualities on an organizational level (Raisch et al., 2009).

While the debate around the effectiveness of different ambidextrous approaches is still crystallizing (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016), research has found cohesion that, if well-managed by corporations, ambidexterity will increase the likelihood that organizations can achieve sustainable growth and improve their financial performance (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008).

From a strategic perspective, ambidexterity must be an integral part of the overall organizational goal and strategy on a firm level. However, the importance in understanding ambidexterity better is not the fact that companies engage in explorative and exploitative behavior at the same time, which is a thoroughly researched topic in current literature (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; Snehvrat et al., 2018; Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016), but rather how they can create a synergy between those two different activities. Creating and implementing mechanisms to leverage shared assets, all connected through selected linking methods, is crucial (O’Reilly et al., 2008, 2009). We are interested in analyzing how companies could create synergies to connect those opposing orientations and improve their ability to be ambidextrous.

Literature has been very much focused on how we can facilitate parity between those two orientations. In the current body of ambidexterity literature, there is a need for understanding whether and how knowledge sharing mechanisms can alleviate tensions on an intra-firm level. Hence, we follow the suggestion: “…investigating the way knowledge

another promising avenue for future research to explore” (Chiambaretto et al., 2019, p.

597).

Analyzing how successful knowledge sharing mechanisms are institutionalized in companies could advance our understanding behind the linking mechanisms needed to manage tensions in ambidextrous companies. Hence, examining how information processing and sharing is done, is a crucial step in developing a mechanism which harmonizes the tensions arising from exploitation and exploration.

However, the operations within a company often take place within teams and their learning behavior capability (Ott et al., 2017; El-Awad, 2019). This is particularly salient in high-tech firms (e.g., software and hardware manufacturers) where most work is undertaken in teams (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006; Davidsson & Honig, 2003). Hence, explorative and exploitative behavior taking place among members of teams that comprise the core units of a company, cannot be detached from each other. Getting insight into how knowledge sharing mechanisms support teams to explore and exploit at the same time, helps us understand how companies can institutionalize ambidextrous behavior on a company level.

There is little understanding in how teams with different explorative and exploitative orientations share knowledge. Internal processes and mechanisms that would facilitate this kind of coordination between exploration and exploitation, particularly when it comes to knowledge sharing, is a topic that has yet been thoroughly researched. In this way, we ask:

How do companies institutionalize knowledge sharing mechanisms that facilitate their ability to be ambidextrous?

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to understand how companies institutionalize knowledge sharing mechanisms that facilitate their ability to be ambidextrous. In answering our research question, we are creating a model that serves a twofold purpose. For scholars, we want to develop a manifestation of the underlying mechanism to understand the knowledge sharing mechanism in the context of ambidexterity. Towards practitioners, we are striving for the managerial and practical implication that companies and new ventures could follow to strengthen and improve their ambidextrous abilities

Considering the granularity of the analysis within the company, understanding how high technology companies institutionalize knowledge sharing means understanding the teams operating within those companies. Therefore, the focus of this thesis will be on teams interacting in or on the interface with R&D departments, since high-tech industries, due to the shorter life cycle of their product, constantly rely on their R&D departments for explorative and exploitative behaviors (Kim et al., 2013).

This study will contribute to the ongoing academic discussion both in the organizational as well as the strategy-focused ambidexterity literature. Hence, we are contributing to the body of ambidexterity literature from authors such as Birkinshaw & Zimmermann (2016), O’Reilly & Tushman (2013), and Boumgarden (2012). Furthermore, the model will suggest a solution for tensions discovered by scholars such as O’Reilly et al. (2008,2009) and Chiambaretto et al. (2019). Examining the intricacies of routinization processes, we contribute new insights for the applications of El-Awad’s (2019) multilevel learning mechanism. Using the multilevel learning mechanism from El-Awad (2019) will help us explore how knowledge sharing is operationalized, leading to specific routinized behaviors. We aim to introduce knowledge sharing as a linking mechanism that bridges ambidextrous tensions between teams with different ambidextrous orientations.

1.2 Thesis Outline

To answer our research question in line with the purpose, we engaged in a qualitative single-case research where we analyzed a listed Swedish company operating in the high-technology industry. The thesis starts with the literature review (chapter 2) to present the current discussion of broader concepts of ambidexterity and knowledge sharing and their interconnections. Following this, chapter 3 presents our methodological assumptions, which influenced our data collection and analysis. After pointing out our empirical findings (chapter 4), we move further to our analysis (chapter 5). There, we highlight how the knowledge sharing mechanisms took place within the organization and discuss how those mechanisms work in relation to existing literature. Chapter 6 presents our conclusions, a consequence of the empirical material, and the body of literature. In the remaining chapters we present our implications for theory, management, limitations as well as our suggestion for future research.

2 Literature Review

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a theoretical background to the topic of ambidexterity and knowledge sharing. Starting with ambidexterity and its forms, we map out the attributes and characteristics of ambidexterity in companies. The second major topic is knowledge and knowledge sharing, implementations and implications are discussed thoroughly. Both topics are set into context by addressing the interface of embedded knowledge through routinized behaviors. The synthesis of the reviewed body of literature guides us in understanding when and where the theoretical learnings will be applicable in the following analysis.

2.1 Ambidexterity

In order to describe the implications of ambidexterity for an organization, one must take a step back and take a stroll on history lane. Scholars have been longing for an academic framework that describes the challenge to both efficiently exploit current opportunities and explore and create opportunities for the future (Rauch et al., 2009). In the early stages of research, scholars where quite consent over the fact that the dichotomic nature of the problem can only be answered by taking both facets isolated. This led to a dichotomic focus on either exploitation or exploration to explain competitive advantage arising from that strategic orientation (Hannan & Freeman, 1977; Miller & Friesen, 1986).

Subsequent research, however, contradicted that dichotomic approach introducing the concept of ambidexterity. According to the field of ambidexterity, a company would be ambidextrous if it can simultaneously address the business challenges of today while being flexible enough for shifts in the tide of tomorrow, thus encapsulating exploitative and explorative behavior in a harmonic fashion (Birkinshaw & Gibson, 2004; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996).

Companies that successfully dealt with the arising conflicts of an explorative and exploitive orientation while acknowledging the necessary dualities on an organizational level were able to get a sizeable lead over competitors (Raisch et al., 2009). Looking at the structure of a company through an ambidextrous lens evoked the field of

organizational ambidexterity (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Raisch et al., 2009). Tackling those dualities can be done through different cases of ambidexterity, which will be drawn out in the following.

2.1.1 Forms of Ambidexterity

According to the literature, ambidexterity was defined as the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontinuous innovation from hosting multiple contradictory structures, processes and cultures within the same firm (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996), one can derive the different forms being

structural, contextual and temporal ambidexterity.

Structural Ambidexterity

Structural ambidexterity describes the method to implement the conflicting approaches of exploitation and exploration with the help of dual structures in the company. Following this archetype, differentiated organizational units are created, each of which deals with replication (exploitation) and innovation (exploration). According to this definition, units that specialize in exploitation are more characterized by formalization, hierarchy, and structuring. The mainstream business unit (henceforth B.U.) remains focused on exploitation utilizing systems, internal processes, and culture in harmony with its goals (O’Reilly et al., 2008). It is shielded by the complexity and uncertainty associated with disruptive ideas lowering the mental strain on the individual operation in each respective B.U.

On the other hand, units specializing in exploration have start-up-like structures, i.e., they are more informal, experimental, autonomous, and risk-tolerant. Furthermore, the exploration unit is shielded by the forces of inertia and profit expectations of the mainstream B.U. The challenge of structural ambidexterity is to create a suitable

other and thus have an optimal spill-over effect (Selig et al., 2019). Separating those roles into teams requires distinct skills and leadership styles to select appropriate team members as well as team leaders according to these tasks (Smola & Sutton, 2002). The implementation of those bridges is, at its core, a leadership issue more than anything else. Hence, top management needs to ensure coordination so that integration knowledge flows between separated organizational units (Smith & Tushman, 2005).

Considering studies made on firm performance, there is a strong indication that it is positively correlated for multiple organizational alignments (Hill & Birkinshaw, 2014; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013), intra-organizational and alliances (Lavie et al., 2011; Phene et al., 2012), given its correct application (Raisch et al., 2009).

Notwithstanding the positive correlation with firm performance, a more nuanced look at the topic is required. The argument for organizational ambidexterity to achieve high-performance hinges on the assumption that the negative externalities caused by the duality of organizational setup can be moderated or minimized through the help of proficient management (Boumgarden et al., 2012).

An apparent weakness of structural ambidexterity is that it hinders effective coordination between exploitation and exploration, with exploration-oriented activities often being unable to be effectively integrated with exploitation-oriented activities, both short and long term. Moreover, structural ambidexterity may also reduce the ability or motivation of those participating in exploitation-oriented activities to seek or pursue new opportunities themselves both internally or, even worse, externally (Smith & Tushman, 2005; Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

Contextual Ambidexterity

Challenged by their local delimitations that were accompanied by the concept of structural ambidexterity, Birkinshaw & Gibson (2004) presented the model of contextual ambidexterity. They argued that while structural implications of separated B.U. enable ambidextrous activities, the organizational contexts of performance management and social aspects such as support and trust are also able to promote ambidexterity in organizations. They defined contextual ambidexterity as the behavioral capacity that can demonstrate simultaneous alignment and adaptability across an entire B.U. (Birkinshaw

& Gibson, 2004). Alignment in that context is the coherence of the entire B.U towards a common goal. Adaptability is the capacity to rearrange tasks on demand, resonating with the contextual environment. In the contextual approach, the choice between exploration and exploitation use is made at the individual or team level (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

In order to set up a framework that supports the decision making on an individual level over time dividing between exploitation- and exploration-oriented tasks on a daily base, a supportive and high-performance organizational context (structure, culture, and climate) is required (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

Presupposing that performance on an individual is directly or indirectly derived on managerial decisions, frameworks that engage with the interface of management and individual performance can help understand the implications of contextual ambidexterity. Senior executives must have cognitive and behavioral agility to alleviate paradoxical tensions (Carmeli & Halevi, 2009). Here, paradoxical leadership, which couples strong managerial support with high-performance expectations has proven to moderate learning orientation and individual ambidexterity (Kauppila & Tempelaar, 2016). Ghoshal and Bartlett (1994) introduced the concept of stretch, trust, discipline, and support, which are relevant for an organizational context and, if developed, are very relevant for individual initiative, cooperation, and collective learning (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1994). Furthermore, self-efficacy correlates positively with learning orientation on the individual level. While contextual ambidexterity was able to address the many delimitations of structural ambidexterity, there is an argument to be made that it shifts the problems on individuals dealing with conflicting tasks simultaneously. The main issue that many scholars see with its current position in literature is the interface between what should, theoretically, and what is in a real-life adaptation. While it is conceptually trivial to draw a connection between exploitation and exploration on an individual level, a real-life adaptation unveils

opportunities (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016) or at least is just effective for business-unit levels at large firms (Birkinshaw & Gibson, 2004).

Both contextual ambidexterity and structural ambidexterity talk about the firms’ scope of how to tackle the dualities of an ambidextrous orientation simultaneously; however, the dimension of time was yet to be proposed. Sequentially introducing the dualities of ambidexterity could reduce the dilution of top-management behavioral integration, while providing resourcefulness to the organization.

Temporal Ambidexterity

Temporal ambidexterity represents the notion of a company being able to realign its structures and reflecting the changed environmental conditions in a sequential fashion. Companies engaging in temporal ambidexterity tend to be semi-structured, which means that some organizational features are determined, i.e., responsibilities and time intervals between projects, while other characteristics are vacillating. Sequential ambidexterity in the context of semi-structures exhibits partial order and tries to moderate between a very rigid and highly chaotic organization (Nickerson & Zenger, 2002). The degree of manifestation is linked to temporal shifting, which directs attention simultaneously to different time frames and ties between them while following sequential steps ex-ante (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). The reason for delimitating the organizational change to the structure is that when switching between exploitation and exploration in a metronomic fashion, it tends to be easier when done between formal structures than between the informal composite that is the organizational culture. This process has been referred to as vacillation between exploitation and exploration modes (Boumgarden et al., 2012). Oscillating between explorative and exploitative orientations is a topic that has been discussed by scholars long before the introduction of ambidexterity (Chandler, 1977). Considering the evolution of major companies like US Today or Hewlett Packard trans tempus, companies adapted in times of change, altering structures to align with the new underlying market conditions (Boumgarden et al., 2012).

In the theory of punctuated equilibrium, Tushman and Romanelli (1985) attempt to encapsulate this temporal ambidexterity change over time. They developed a model of organizational development based on simultaneous consideration of the elements for

stability, the forces for radical change and the role of top-level management in mediating these opposing dynamics. In order to get a better understanding of the crucial role of environmental discontinuities on current behavior, this approach points towards a careful balance in organizational development, which emphasizes both the commencement and the cessation throughout the history of organizations (Tushman & Romanelli, 1985). Analyzing temporal ambidexterity is done over long periods and usually in large samples. Patterns in those studies indicated that temporal ambidexterity tends to be useful in stable, predictable, and gradual changing market environments (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013). They offer a practical solution for smaller firms where there is a lack of resources to simultaneously engage in exploitation and exploration (Chen & Katilla, 2008).

Temporal ambidexterity has two significant advantages for the organization.

Firstly, it overcomes the downsides of structural ambidexterity in that operations are never separated from each other and disjunct in their scope. Secondly, it lowers the strain on the individual induced by contextual ambidexterity in that it needs to focus both on explorative and exploitative factors at the same time. This ensures that knowledge and capabilities from exploitative actions are integrated into explorative tasks and vice versa (Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

The downside resides in the costs of changing between organizational systems adhering to the perceived need for exploitation and exploration.

In managing ambidextrous organizations, tensions often arise which warrant actions to alleviate them. Companies must be engaged in developing practices to promote a knowledge sharing culture within their organization. This action would facilitate access to the right resources to perform ambidextrous routines.

coordination between the structural demarcations through linking mechanisms is an ongoing challenge to companies (Smith & Tushman, 2005; Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

Furthermore, the top-down imposed structure from the senior management is prone to leave the individuals lacking motivation and the sense of participation in the long-term perspective of the company (Boumgarden et al., 2012). Solving this issue by imposing contextual ambidexterity on the individual is shifting the burden from structural tensions to individual cognitive strains, which, according to the literature, also does not lead to long-term improvements rather than incremental ones (Gilbert, 2005; Zimmermann & Birkinshaw, 2016).

Having a more organic emerging, top-down induced but bottom-up striving approach could offer a remedy to the challenges above in connecting, informing, and routinizing the linkage of explorative and exploitative activities within the company. Understanding and utilizing knowledge and knowledge sharing could offer a solution to this wicked problem.

2.2 Knowledge

In order to understand how knowledge sharing occurs within a company context, one has to define the components, starting from what knowledge is and which types of knowledge exist.

Undertaking a definition of knowledge is not only a paradox on a surface level rather than one of the most controversial definitions possible. While most of the English speakers use the word quite thoughtlessly, its origin tells us a lot more than one might think. In ancient Greek, knowledge means Gnosis, literally disambiguation, the dispersion of ambiguity. The word could be described as a cognitive onomatopoeia and played a fundamental role in developing the origin of ancient philosophy.

Ibert (2007, p.104) expresses this paradox quite nuanced when categorizing knowledge as the type of word that “one knows exactly what it means – until forced to define”. Resulting from this incoherent definition of knowledge, differences, and divisions started

to emerge and being developed (Lai, 2013). Hence, this thesis delimits its focus on the individual-level and firm-level perspectives for business management applications. From an individual-level, knowledge is a combination of cognitive actions where individuals become familiar with, aware of, or apprehend something or someone. This cognitive process consists of facts, information, or skills acquired through life-time experience, beliefs, or education, either by perceiving or learning (McCracken, 2003). Prominent researchers in the field of firm-level knowledge argued that knowledge is a well-founded belief, reinforced by the fact that individuals continuously search for confirmation of their believes. Moreover, it is the result of constant self-adjustments made by individuals who seek to propose and meaning (Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Nonaka, 1994)

Concluding the aspects mentioned above, knowledge is a dynamic and unstable definition. In order to encapsulate these dynamic elements, the following can be stated. Knowledge involves some degree of tangible information, past experiences must be considered, and personal values create flow patterns for knowledge acquisition (Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Nonaka, 1994).

2.2.1 Explicit and Tacit Knowledge

Benefiting from knowledge can be a complex and dispersed endeavor since it lays both within and beyond company boundaries. This dissemination across multiple layers leads to limitations when trying to retrieve and manipulate knowledge. Consequently, potential opportunities may be hindered since decision-makers prefer to focus on easily available information, leading to uninformed decisions resulting in low-quality outcomes (Lai, 2013). Polanyi (1966) suggested two types of knowledge: explicit (tactic) and implicit (tacit).

to transfer, senders may still struggle to code, explain and articulate the information to its receiver (Mu et al., 2010).

Implicit knowledge, on the other hand, is more complex to express. It can be compared to an information system: input > processing > output. Therefore, it is the outcome of observations and experiences. This type of knowledge, at its core, emerges from subjective cognitive areas, such as insights, intuitions or hunches which cannot be codified into a tangible material (Kim et al., 2013; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Nonaka, 1994; Teece, 1998).

So as to find a unifying approach to those entirely disperse types of knowledge, Becker-Ritterspach (2006) suggested a systemic framework of knowledge integration in corporations’ subsystems, where knowledge must be disembodied, interpreted and integrated for the learning to take place.

2.2.2 Knowledge Utility

In an intense-competition setting as in high-technology industries, Davenport, (1997) suggested that every company could reach the same level of technological development when having access to the same resources, therefore, having technology is not a synonym of competitive advantage for modern companies but a fungible good. Hence, to differentiate from their competitors, the focus of companies has to be on knowledge-based activities to foster creativity over productivity (Lai, 2013).

Knowledge-based activities could translate into making informed decisions regarding their market-entry, product development, and operations lifecycles. To maintain a competitive advantage, large companies focus on accumulating internal and external knowledge to foster their business goals. Since this knowledge could be stored within the organization, individuals could benefit from practical experiences and be more proactive towards the decision-making process (Lai, 2013).

2.3 Understanding Knowledge Sharing

Dhanaraj et al. (2006, p. 660) defined knowledge sharing as ‘the ease with which

knowledge is shared, acquired, and deployed within the network’. Network in this context

means the individuals to whom this phenomenon would occur when there is a sender do disseminate information and a receiver to absorb the intended content to be transferred. This transfer would follow specific rules and will require a channel such as social interactions for this exchange to take place (Carlile, 2004).

Figure 1 - Sender/Receiver Model of Communication

Source: Mu et al., (2010, p. 33) adapted from Berlo (1960)

Mu et al. (2010, p. 33) stated that “those network structures respond to many forces and

factors in the environment, ties between individuals and the effects of one actor on another are crucially important to the building and maintenance of networks”.

Furthermore, the performance of a network is affected by members who control and distribute resources, information, and knowledge. Therefore, this complex and dynamic network emphasizes the social relation among knowledge transfer and senders (Tsai, 2002). In a firm-level knowledge sharing, routines such as daily tasks, project cooperation, and social interaction for relationship building should set the foundations for potential diffusion of both types of knowledge (Mu et al., 2010).

2.3.1 Dimensions of affirmative knowledge sharing

Whether knowledge sharing is positively executed hinges on two dimensions: cognitive ability and motivation to do so. They are both independent dimensions that positively reinforce each other.

2.3.2 Cognitive Ability

A collective group of researchers investigated complex knowledge networks and agreed to its systemic nature and stickiness of knowledge (Inkpen & Dinur, 1998; Lord & Ranft, 2000; Simonin, 1999; Szulanski, 1996; Zander & Kogut, 1995) which, if not managed accordingly, will hinder the diffusion of tacit and tactic knowledge. Stickiness here refers to the recipient's lack of absorptive capacity, causal ambiguity, and an arduous relationship between the source and the recipient (Szulanski, 1996).

However, it is essential to stress the importance of individual motivations for this transfer to happen. Thus, this topic is highly investigated by academia (Noorderhaven & Harzing, 2009). Authors found evidence that high levels of motivation have a positive impact on the quantity of knowledge sharing (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Tsai, 2002). On the other end of the spectrum, Szulanski (1996) suggested that a lack of motivation will create barriers for the exchange to take place. Especially since the cognitive abilities of employees are less prone to external stimulation and are somewhat “static”, whereas motivation can be considered “soft”. Therefore, Pérez-Nordtvedt et al. (2008) concluded that motivation is the driving pillar over the decision whether knowledge will be exchanged or not, following the Sender/Receiver Model of Communication (Mu et al., 2010 p.33).

2.3.3 Motivations

Assessing the mechanisms behind motivations, a straightforward observation must be stated. Every single employee is an individuum unique in its traits, character, and goals. As aforementioned, successful knowledge transfer is contingent on the right cognitive attributes in the individual. That, in turn, means that knowledge can be worth something to others, which makes it a bargaining power in social interaction. This is under the ceteris paribus that once the knowledge is shared, the employee will be less valuable to the company because out of the set of knowledge he possessed, parts have been made common (Husted & Michailova, 2002; Ray et al., 2013).Research on knowledge sharing

at the individual level has revealed that knowledge holders may be more reluctant to share their knowledge with colleagues if this knowledge has strategic value for their role and professional opportunities (Davenport & Prusak, 1998).

Additionally, the perceived quality of the knowledge shared influences the motivation ex-ante. The knowledge employees share could either be objectively wrong, as in flawed or subjectively wrong, as in deviating from conformity, which would damage their reputation (Husted & Michailova, 2002).

Furthermore, the availability of time, financial resources, and human capital were often perceived as a hindrance to sharing knowledge. This was especially true for employees with busy daily routines, where this sharing was seen as an extra burden (Chiambaretto et al., 2019). Acknowledging the existence of these dissuasive factors, companies could utilize their economic and factual power disparity to enforce this knowledge sharing to take place (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000). However, the ideal would be the goodwill from the employee (Caniëls et al., 2017). Knowledge sharing then could be seen as a voluntary and, at least partially, altruistic one-sided act.

2.4 Intra-firm knowledge sharing and company culture

Taking into consideration that knowledge has different levels of complexity, Hansen (1999) argued that the intra-firm ties are indeed relevant when dealing with the sender/receiver model, even when people are motivated to share. A weak tie would lead to a slow exchanging process when dealing with complex knowledge. For example, exchanging tacit knowledge depends on the level of interaction and trust between sender/receiver (Hurmelinna-Laukkanen et al., 2012). Tacit knowledge in this context is often considered complex in its core. For trivial knowledge, the transmission is faster. Granovetter (1985) highlighted the relevance of face-to-face interactions. For instance, in explorative tasks, the exchange of knowledge does not follow a structuralized way. It

cognitive ability to expose their perspective (Wegner et al., 1991). (2) This co-constructed interpretation highly contributes to improving teams’ performance (Peng & Mu, 2011) and (3) this virtuous circle would act as a facilitator for teams to raise the complexity, accuracy and shared beliefs of their embedded knowledge (Hollingshead & Brandon, 2003); thus, ties become a fundamental factor knowledge share to take place within the company.

For units with strong ties, even complex knowledge is shared in a faster manner when compared to weak ties (Hansen, 1999). This is a direct result of the underlying drivers for knowledge exchange, namely motivation between the actors sharing the knowledge. Moreover, intra-firm knowledge sharing is more likely to happen between units who already have shared practices, e.g., sales and marketing or different R&D projects, and therefore possess a stronger tie (Noorderhaven & Harzing, 2009; Brown & Duguid, 2001). When there is the broker figure, the tie just has to happen within the broker and the employee, not necessarily between the knowledge emissary and the other employee. They would access the knowledge through the broker (Fleming et al., 2007).

Individual motivation being the primary trigger for sharing knowledge, studies add by suggesting that employees from the same company are more predisposed to exchanging knowledge. Further, this is enhanced by sharing a physical space in which they are performing their tasks, as mentioned by Brown & Duguid (1991), working and learning transpire together. Thus, the knowledge exchange would be initialized by observation and casual communication, such as “can you explain to me what you did?” (Reagans et al., 2005). Employees have better usage of existing knowledge in a network than if they were working alone, so this physical proximity and similar pre-existing knowledge trigger the sharing culture (Reagans et al., 2005). Not so, companies (e.g., Novartis) co-located their R&D department as a way to increase unplanned FTF employees’ interaction on their open multi-space office. This led to an environment where enabled socialization,

externalization and combination of knowledge (Coradi et al., 2015, p. 251).

Thus, companies take action to stimulate this culture, either by having a knowledge broker or integrating all their internal networks (Boari & Riboldazzi, 2014; Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000). Preventing risks malicious to this spirit, such as free riding, will reduce costs related to gathering and retrieving knowledge and will motivate members to engage in the sharing culture (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000). As a by-product, awareness of the actions

of other units is heightened within the organization (Aalbers et al., 2013; Hargadon, 1998).

Regardless of how companies organize themselves to promote this culture overall, there is a hub in charge of organizing and promoting the knowledge exchange (Dhanaraj, Charles and Parkhe, 2006). This integrative framework will foster motivation for employees to engage in knowledge sharing practices (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000). By offering this cohesive force, members would feel confident enough to expose themselves and will act in good faith to share what they possess (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Orton & Weick, 1990).

2.5 Operationalizing Knowledge into the organization

Sharing knowledge on an individual level hinges on the cognitive ability as well as the motivation or lack of dissuasive elements to do so. Furthermore, individual learning happens through the “experience of doing”, which enables them to recognize entrepreneurial opportunities (Politis, 2005). Individuals process information and, through trial and error, update their decision algorithms and, in an iterative process, improve their decision making and ultimately gain knowledge assessing the performance (Minniti & Bygrave, 2001; Ott et al., 2017). On an organizational level, it was shown that shared rules and procedures could help to diffuse knowledge (Franco & Haase, 2009). In order to encapsulate the process of embedding knowledge into an organization, El-Awad (2019) proposes mechanisms that facilitate the transmutation of knowledge.

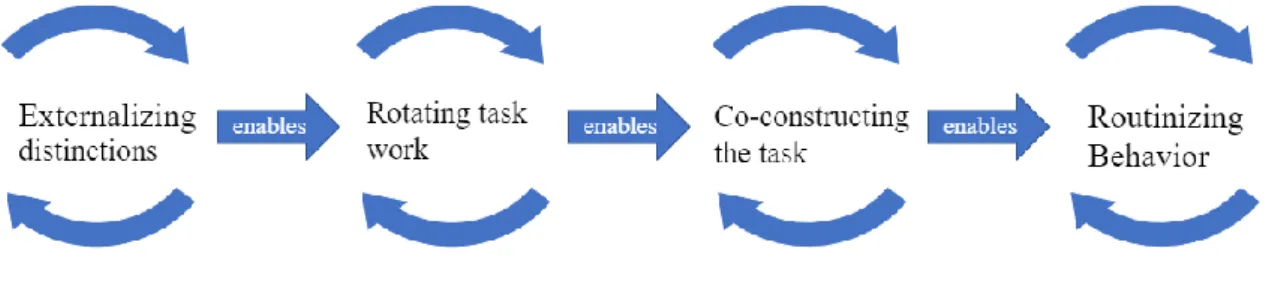

In El-Awad’s model, the process between individual learning and the organizational embedding transposes in four different phases.

Figure 2 - Multilevel learning mechanism

Source: Adapted from El-Awad (2019).

The first stage, externalizing distinctions, describes the process where team members start verbalizing specific experiences, perceptions, opinions, and ideas. The result of this process on the knowledge base is twofold. Firstly, it maps the knowledge base of all individuals involved, which presents an overview of the knowledge base on which members can draw upon (Argote & Ren, 2012). Secondly, the mapping process enables the individuals to identify knowledge clusters in persons, the “who knows what”. Furthermore, it minimizes dissuasive elements of knowledge sharing amongst individuals in that the level of risk associated with the decision to share is significantly lower (El-Awad, 2019).

Externalizing distinctions enable rotating task work. This mechanism describes the

process where members get assigned to new tasks where they are less knowledgeable. This rotating work exposes team members to existing team knowledge, which transposes to new knowledge on an individual level. According to Lewis & Herndon (2011), this process contributes to improved task performance. Furthermore, it introduces a catch-up mechanic that leads to heightened technical and product knowledge on an individual level and, thus, as a derivative, across the teams (El-Awad, 2019; Widding, 2005).

In the third stage, co-constructing the task allows the rotating employees to draw patters based on the additional perspectives they were able to get on previous positions in the

rotating task work stage (Wilson et al., 2007). The insights from mapping existing team

knowledge and nurturing constructive conflict by learning with and from other team members constitute an improved business knowledge. This is primarily related to the customer, market, and work-process knowledge (El-Awad, 2019). Integrating these insights and experiences hinges on the motivation and cognitive ability of the individual

acting in the team environment. Pitfalls to this learning process are contradicting cognitive interpretations and the disregard thereof (Dougherty, 2001).

Lastly, co-constructed tasks are getting embedded into the company level, leading to

routinizing behavior. Through the observation of patterns and routines, team members

can infer general principles guiding their work (El-Awad, 2019). This cognitive representation emerged from different individuals performing similar tasks, which enabled them to construct a conceptual framework.

2.6 Literature Synthesis

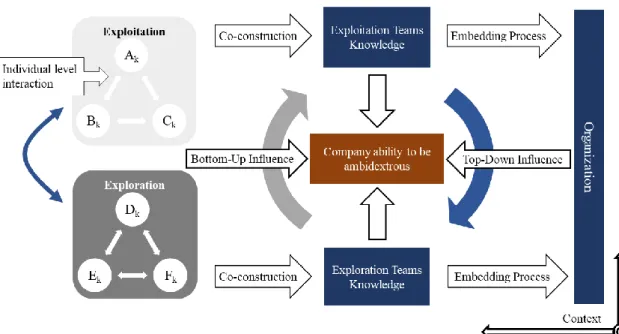

In the following, the literature review will be briefly recapitulated and put into the context of the thesis. Synthesizing the body of literature on ambidexterity and knowledge sharing, Figure 3 introduces a preliminary model on the interface of knowledge sharing and ambidexterity. It further displays the embedding process of knowledge into Teams and, thus, into the organization. The model incorporates the conceptual understanding from the body of ambidexterity literature as well as the different manifestations of ambidexterity.

Understanding the different iterations of and oscillations in-between forms of ambidexterity is vital to understand the implications of knowledge sharing on ambidexterity, hence a thorough review of the ambidexterity body was imperative. Here, recognizing contradictory structures, processes and cultures within the same firm simultaneously executed (O’Reilly et al., 2009; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013) transmutes our understanding of the underlying state of ambidexterity in the case at hand, which is displayed by the two bubbles on the left-hand side in Figure 3. Our insight on ambidexterity is extended by its three distinct identified forms (Contextual, Structural and Temporal), which are prevalent in the current body of ambidexterity literature.

Figure 3 – Literature synthesis of ambidextrous activities and knowledge sharing

Source: Own creation

The preliminary model is expanded with the topic of knowledge and horizontally traversed by knowledge sharing. The granularity of the model, the level of analysis, goes from left to right, starting with individuals over teams and leading to the organization. On the individual level, knowledge is shared on a peer to peer basis and hinges on cognitive ability and motivation. Teams, comprised of said individuals, are essentially the core unit of a company when talking about the importance of sharing knowledge. Additionally, knowledge on a team level is more significant through the process of co-construction. The extensions of the multilevel learning mechanisms support the understanding of how a company can embed and transpose knowledge over different levels. Especially the process of externalizing distinctions can support us in our understanding of knowledge diffusion on the team level.

What remains unknown is the influence of the organization on the individual, respectively, from the Top-Down or the Bottom-Up, and other factors in the context of ambidextrous ability formation. The main focus in the following will be routinizing formal or informal knowledge sharing processes, whether and when knowledge is shared on a team level or an individual level, and the implications it has on the ability to act ambidextrous.

3 Research Methods

The purpose of this chapter is to define the methodological assumptions to answer the proposed research question. We introduce the case and how the data collection process took place, followed by how this material was processed before converting it into grounded theory. The whole process was guided by our philosophical assumptions and ethical rigor.

3.1 Methodology

The chosen methodology will define how this study was conducted. In this section, we present our philosophical assumptions, our research approach, and the research instruments we engaged in before presenting our case.

3.1.1 Philosophical Stance

A question is “a sentence or phrase used to find out information” (McCracken, 2003). It has an addressor and an addressee that seldom originate in the same entity. The beauty in life is that we depend on people to answer our questions. Those people are actors in a reciprocal relationship with their environment, which makes the answer to our question dependent on the product of the environment as well the actor. Therefore, in our undertaking to answer our question, we must also consider the environment for the integrity of the answer. Such a philosophic stance is in accordance with a socially constructed perception of the nature of reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018), which is a strong argument for qualitative study design.

Although the chosen case has a company culture based on transparency, which is a strong trigger for promoting knowledge sharing (Zheng et al., 2010), the aforementioned environmental conditions will affect their behavior during the interviews. Additionally,

and stances on the surrounding actors interacting with and being influenced by the environment led us to engage in a qualitative study design.

Therefore, this work is drafted following the ontological principles of relativism, where the reality based on the perspective of the viewer, and each piece of qualitative data is an individual truth. Overall, we must consider multiple perspectives to obtain this holistic view based on a blurred reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

3.1.2 Research Approach

The research design would aim to guide us through the planning and execution process of this thesis by providing a framework of how to collect and analyze the data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Since we are investigating a dynamic factor, managing ambidexterity, we followed Merriam (1998) and Yin (2009), where they mentioned that a pre-understanding of the theory would ease the start of the researching process and move forward to the data collection process. However, this existing literature will not define our conclusions.

This thesis followed an abductive approach, meaning that the data collection and literature must walk “hand-in-hand” to empower us to make a better sense of the empirical material, as well as driving towards a better conclusion (Dubois & Gadde, 2002; Jebb et al., 2017). To conduct this approach, going back and forth between empirical material and existing literature was essential in finding the ultimate answer to the research question.

3.1.3 Research Instrument

To answer our proposed question and based on the identified epistemological stance of social construction, the most reliable method to extract the complexities of a phenomenon to the context in which it is inserted would be an exploratory single-case (Yin, 2016). It will provide ground for much more in-depth analysis if compared to multiple cases, where the authors have to divide their focus to understand both sides before reaching a conclusion (Doz, 2011).

Most researchers conducted multi-firms quantitative research; however, little attention was given to one firm case study (Snehvrat et al., 2018). We acknowledge that it would

be easier to generalize theories by comparing different companies through quantitative analysis. Nevertheless, when dealing with a single-case company, a qualitative case would be more suitable (Denicolai, Zucchella, & Moretti, 2018) and would open doors for further studies. Following this, we follow a pars pro toto argument when engaging in a qualitative single-case study. Additionally, due to the nature of the company case, we choose to engage with an embedded multiple-units analysis design. Meaning that the answer for our research question will emerge from a combination of the perceptions from each B.U., as well as our body of literature (Edmondson & Mcmanus, 2007).

3.2 Chosen Case

Due to the short life cycle of their products, companies operating in high-tech industries continuously rely on their R&D departments to create competitive advantage of their existing products while attempting to anticipate future events (Kim et al., 2013). Rapid technology changes precede quick adaptability and fast knowledge sharing across locations and business units (Lubik & Garnsey, 2016), which resonates much with the field of interest. Hence, we choose to seek out a company operating in a high-technology environment.

The company at hand provides an exceptional case for our investigation of the interface of ambidexterity and knowledge sharing. It is a Swedish listed company which produces unique software and hardware devices to supply their market. It was founded in the early 2000s, nowadays has around 1,000 employees (with 400 dedicated to R&D activities), and reported an average of €130m over the last few years as net revenue. Their operations are spread worldwide, with production facilities in China, USA, and Sweden, and also has sales offices in 9 other countries. In 2015, the company went into a significant restructuring process initiated by the acquisition of an external company. The top-level management decided to split the R&D by Business Units (B.U.) instead of having a

keep the vanguard in their niche, the company’s capital expenditure in R&D represents an average of 40% of their total expenses, making it a prominent line on their financial report, which is adding another strong argument towards it being an exceptional case for this thesis. Moreover, the company has R&D departments in 4 different countries. The company holds full ownership over its three different B.U. Each of them has its own organizational chart, as well as a dedicated R&D department to support their particular market needs. However, since they use the same core technology, those B.U. regularly (in theory) communicate with each other to exchange knowledge. The company has shared synergies in areas such as common facilities and finance. However, they remain mostly independent from each other in terms of marketing, production, and sales. What happens eventually is that the company may influence resource allocation, such as employees or financial resources from one B.U. to another, aiming to maintain the wellbeing of the group.

Based on that same shared core-technology, exploitative and explorative decisions are being continuously made but also may differ in their nature depending on the use-case for each respective department. That means that an exploitative use for one department could be ground for an explorative use in another.

3.3 Data Collection Method

Aiming to understand how companies institutionalize knowledge sharing mechanisms that facilitate their ability to be ambidextrous, we decided to gather empirical material from qualitative data with a semi-structured interview and secondary data as supporting material. When it comes to the selection of candidates, Easterby-Smith et al. (2018) introduce both probability and non-probability sampling. In probability sampling, each employee would have the same likelihood of being chosen, which leaves selection based on chance. This approach is not feasible in our case at hand, for we are interested both in a representable horizontal and vertical cut in the organizational chart with interest in employees working in or with the R&D departments. Hence, we choose to engage in a non-probability purposive sample design. This enabled us to capture a wide range of perspectives following our purposive sampling while having a rather small sample (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

A non-probability purposive sample design opens up the risk of having a strong bias in the participants where the purposive driven participant selection is not representable for the case at hand or based on candidates with specific agreeable character attributes (Saunders et al., 2019). To circumvent this potential unilateral selection process, we followed our participant selection based on set criteria, which are illustrated in the following.

3.3.1 Selection of Participants

To conduct the fieldwork, we defined three requirements for individuals to be considered as an interview participant.

First criterion: Engaging in work routines interacting with/within R&D

Selecting potential subjects is based on the seniority level and different work routines within R&D. For this matter, the employment starting time was purposefully disregarded. That is, if the person was recently employed in the company, we could get insight into how they developed their understanding of the company processes and how they managed to grasp knowledge that they were not aware of.

Second criterion: Ensuring a holistic view

We were aiming for a holistic view of each B.U. R&D. Hence, we shortlisted the first round of potential interviewees by conducting a horizontal cut across the company organizational chart. Therefore, the group CEO, the heads of all R&D departments, were selected. Furthermore, a similar weight of directors and managers across all three B.U.s. was ensured.

Third criterion: Prioritizing the interface

directors, and managers in one B.U. had a counterpart in another B.U. unit performing a similar task.

Those pre-set requirements enabled us to evaluate the statements coming from senior managers and observe how the implementation was diffused across the hierarchical levels of each B.U.

3.3.2 Data Collection

As a start, our facilitator at the company with a relevant position in the HR, contacted all the heads of R&D from each B.U. via corporate email, requesting their availability for an interview. This was giving us legitimacy showing that the thesis was officially supported by the company. Additionally, we hand-picked directors and managers based on the organizational chart.

After their definite answers of the heads mentioned above of the B.U.s, we booked the first round of interviews. During and after the interview, new potential interview candidates emerged based on recommendations. That strengthened our purposive sample design by getting fitting candidates who have not previously emerged from looking at the organizational diagram. However, we avoided the randomness of the so-called “snowball sampling”, where we would interview every recommended person regardless of its relevance for the topic (Kincaid & Rogers, 1981). Instead, we focused on quality over quantity and screening all potential candidates based on the criteria above. Therefore, non-probability purposive sampling was the only method used.

3.3.3 Interview Structure

The interviews were following the semi-structured protocol (cf. Appendix A), covering topics such as ambidexterity, routinized behaviors, knowledge, and cross-unit relation. This approach had a two-fold purpose: getting familiar with each B.U.’s motivations for their R&D activities and understanding the reasoning behind each motivation to deal with their tasks (Aalbers et al., 2013). This flexible structure allowed us to adjust questions and follow-ups depending on each participant’s position. There was a clear difference between B.U.’s orientation and seniority level, and we had the feeling we could not push an interviewee, which was dedicated to one type of project to engage in reflecting on

another project type. Therefore, we followed (Swart et al., 2019) hypothesis that ambidextrous activities vary between the level of seniority and which actions they take on their daily working routines to adapt our interview protocol.

3.3.4 Primary Data

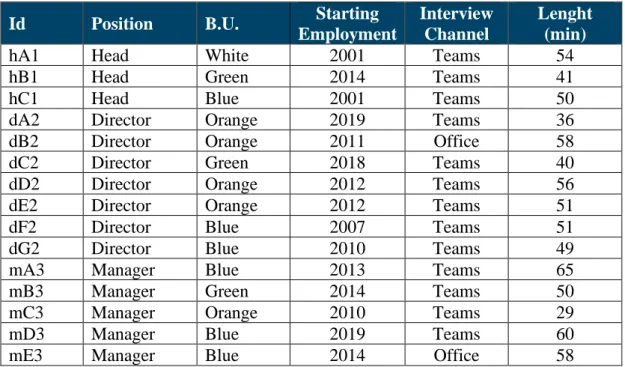

To reach out to potential participants (other than the head of R&D), we used our own corporate email and waited for their availability. Overall, we had a response rate of 80% of all potential interview candidates. In addition to our selection, we were recommended to interview nine other employees. However, only 4 met our purposeful sampling criteria. We had 15 scheduled interviews, where 14 were voice recorded interviews and 1 participant with handwritten notes. This data collection process happened during weeks 11 to 14 in 2020. An average of 50 minutes of recorded material (table 1) and all interviews were conduct in English.

Before starting the recording, we briefly introduce ourselves and the topic to the participant and to ask consent for the recording as well as to build trust and get legitimacy. Adding this “before recording” to the recorded material, we totaled 15 hours of empirical data collection. After every interview, we spent about 20 minutes discussing the initial impressions and exchange notes.

Table 1 - Interview participants

Id Position B.U. Starting

Employment

Interview Channel

Lenght (min)

hA1 Head White 2001 Teams 54

hB1 Head Green 2014 Teams 41

hC1 Head Blue 2001 Teams 50

dA2 Director Orange 2019 Teams 36

dB2 Director Orange 2011 Office 58

dC2 Director Green 2018 Teams 40

dD2 Director Orange 2012 Teams 56

dE2 Director Orange 2012 Teams 51

dF2 Director Blue 2007 Teams 51

dG2 Director Blue 2010 Teams 49

mA3 Manager Blue 2013 Teams 65

mB3 Manager Green 2014 Teams 50

mC3 Manager Orange 2010 Teams 29

mD3 Manager Blue 2019 Teams 60

mE3 Manager Blue 2014 Office 58

On average, selected participants have been working in the company for nine years, compared to the companies’ overall tenure of 4.9 years. We also managed to select participants who were involved in cross-organizational projects and had worked for different B.U.s along their career at the company. Moreover, we had participants engaged in R&D activities in Sweden, United States, Ukraine and China. The colors are representing which B.U. they are working in now, but it does not display past positions.

3.3.5 Secondary Data

In order to triangulate the gathered information, we were granted access to their intranet by having our own corporate e-mail address. Thus, we could access internal presentations and reports used by all teams in the company, assuming the considered use of confidential information. This extra internal information helped us to establish confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and enriching the whole empirical material since it prevents researchers from developing their findings with blurry information (Doz, 2011).

Moreover, part of the company culture is transparency. In the intranet, it was possible to find the roadmaps and business plans for the whole organization and a breakdown of the strategic orientation of each B.U. That enabled us to narrow down our enquires, giving room to the participants explaining more practical examples, such as why projects are

being put “on hold” before the end of the 3-year plan. By triangulating primary and secondary data, we could conduct a richer data collection process.

3.4 Research Quality

One of the major critique points of qualitative research is its subjective results relying on anecdotal experience, which may lead to a lack of precision in the measurements and quantitative rigor (Guba, 1981). The remedy as an answer to that critique is to establish trustworthiness. We attempt to establish trustworthiness by focusing on the credibility and transferability of the study.

Credibility we are addressing by considering the complexities of qualitative research. As

stated in Research Approach, we see the actor and the environment as reciprocal: they cannot be understood disjointed. This means that we must be concerned about the distortion we cause with our presence both in the interviews online and on-site. This was planned, ex-ante, by spending a lot of time on-site, emerging ourselves in everyday life at the company. Furthermore, during the interviewing process, we established a specific time before the recording, where we just conversed semi-casually with the interviewees to adjust them to our presence. At the end of every interview, we engaged in peer debriefing, that is, that we disclosed our full research question and let the participants reflect on that. The feedback and thoughts of the participants guided us in our internal debriefings, ensuring that we are addressing “the real thing”. Through the process of triangulation, we cross-checked data based on multiple participants and secondary data (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008).

Transferability is a devoted effort by using purposive sampling with the intent to

maximize the range of information. We addressed the bias of unilateral selection of interview candidates with participant selection based on the three criteria above. Given the same criteria left by our audit trail, researchers should be able to replicate a similar

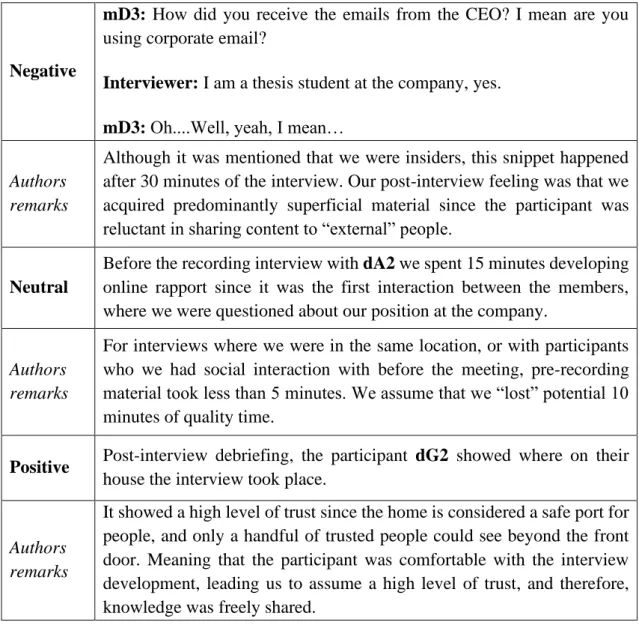

3.4.1 Adjustments during the Data Collection process

The biggest challenge during the data collection was to cope with the current Covid-19 outbreak. The Covid-19 outbreak had major implications, one upfront, moving from face-to-face interviews on-site to online interviews. One unexpected derivative was that we started to lack legitimacy in some interviews.

Concerning the upfront challenge, meetings had to be rescheduled from a face-to-face interaction at the company’s office to the Microsoft Teams platform. We originally planned on staying in the company premises for the whole process over weeks or even months, diving into the company’s daily routines even more than we already did prior to the interviewing process. Facing the uncertainty of the situation, we decided to shorten the collection period by compressing more than one interview per day. This led us to reduce our reflection time after each interview.

In terms of this thesis development, during the data collection period, one member of the team had access to the office in Stockholm while the other returned to Jönköping. This limited us in engaging in informal interactions at the office in events such as “fikas”. We also had limited access to unplanned follow-ups on how employees use specific sharing knowledge tools (e.g., JIRA) or employees’ immediate feelings after our meeting. Although we were granted access to the premises to spend time even when there was no formal interview scheduled, the collection of unexpected data was limited to few employees who were still able to go to the office.

Considering the recorded interviews, none of them had all the participants in the same physical room. Only two interviews had at least two people in the same space and one person online. The ideal scenario would have face-to-face interaction, spotting subliminal information other than the recorded interview, such as body language, to enrich our data collection process (Opdenakker, 2006).

Additionally, moving to online interaction brought the derivative challenge of lacking legitimacy, at least in some interviews. It made it challenging to develop a rapport with the participant (O’Connor & Madge, 2001), as some examples in table 2: