The International Committee of the Red

Cross: A Century of Consistency

A Care Study of Visual Identity on Facebook

Katharine Sarah Lloyd-Thomas

Communication for Development, Degree Project HT20 Word Count: 13, 586

Submitted on January 7th 2021 Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

2

Abstract

The International Committee of the Red Cross and Crescent Moon (ICRC) is a leading global humanitarian organization. Despite an exemplary operational record, the ICRC has an imperfect communication history: slow to respond; painfully neutral; and unwilling change. ICRC history, diplomatic and humanitarian communication has been well researched. However, few studies, outside of Maillot (2017), address ICRC SM communication within the ICRC historical context. There is a fundamental value in understanding how an INGO is responding to the challenges of public advocacy communication on SM. This review should allow the identification of improvement areas for digital diplomacy. As a first mover, ICRC policy on SM would lead the industry through a digital evolution. Inexhaustible SM growth has increased both the type and the frequency of posting. INGOs are now posting multiples times per day; visuals are the dominant media form; and there is a growing need to use visual content that stands out. This sudden proliferation of visual, including 360 ° video footage (Garcia-Orosa, 2020), has opened conversations on the dehumanization of suffering (Chouliaraki, 2006), the lack of representation, and repeated content with colonialist tone. Capability gaps have become apparent as organizations struggle to keep pace with the change. This Case Study reviews the visual content of the ICRC on Facebook within the historical visual context. Focusing on visual Facebook posts from the ICRC, the selected ICRC visual content was analyzed using Barthes (1957) Mythological approach within a historical context. It will be argued that opportunities exist to evolve the visual identity to avoid reinforcing social stereotypes and improve authentic representation. To raise awareness and funds, the ICRC continues to use more old-fashioned and occasionally colonial visual imagery; it feels like the organization is imprisoned by the strength of its historical identity. Solutions are outlined to help define a new way forward including: first, a cultural evolution to help the organization avoid the pitfalls of the past; second, an openness to training. capability gaps are normal – seeking help to train the organization will improve SM effectiveness.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

3

1. Table of Contents

1. List of Figures 4

2. Introduction 5-7

3. Literature Review

3.1 International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) 3.2 Social Media (SM)

3.3 Visual Analysis Theory 3.4 Representation

3.5 Communication for Development (C4D)

7-19

4. Theoretical & Conceptual Framework 20-22

5. Research Methodology 21-27

6. Analysis 28-38

7. Conclusion 38-40

8. Appendix 41-43

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

4

2. List of Figures

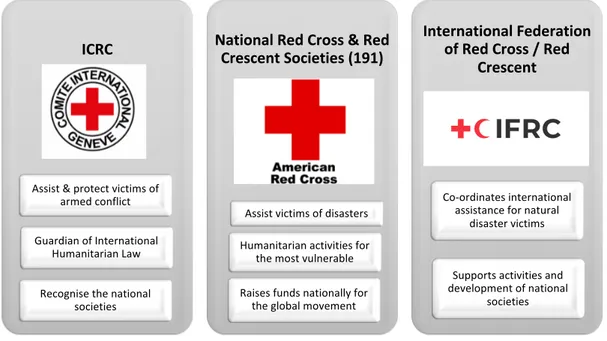

Figure 1: Organizational structure for The Red Cross & Red Crescent Movement

Figure 2: A Modern Snapshot of the ICRC Facebook Page alongside historic visuals of the

organisation.

Figure 3: Digital Around the World in July 2020.

Figure 4: Visual example of how an individual Facebook post can receive Engagement. Figure 5: Four Phrases of Photography and the use of Visuals in Mass Communication. Figure 6: Definition of the 4 elements of the Public Engagement Model (PEM) (Grunig

and Hunt, 1984)

Figure 7: The structure of Barthes (1957) Mythological Approach to Semiotic Analysis

when compared to the purely Semiotic Approach.

Figure 8: Landscape Assessment of Red Cross Facebook pages across various organizations

to understand posting methods & engagement protocols.

Figure 9: Summary table showing the categorization steps for the ICRC Facebook content

pulled from their Facebook page during a six-week period on Autumn 2020.

Figure 10: Breakdown out the main messaging from the posts on the ICRC’s Facebook page

over a six-week period from mid-September until end-October 2020.

Figure 11: Breakout of the type of media posted on the ICRC Facebook page during a

Six-week period from mid-September through end-October.

Figure 12.1: ICRC “COVID-19” post, selected for analysis.

Figure 12.2: Historical Facebook Post from 28th of December 2015 Figure 12.3: Historical ICRC visual from the late 1800s

Figure 14.1: ICRC “War” post, selected for analysis.

Figure 14.2: ICRC’s third ever Facebook Post. Highlighting actions in the Libyan War. Figure 14.3: Red Cross organized schooling during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1948-1950. Figure 15.1: Figure 12.1 and 14.1 analyzed within the PEM (Grunig and Hunt, 1984). Figure 15.2: Publicly available Share of the ICRC Facebook Post (Figure 12.1)

Figure 15.3: Publicly available Share of the ICRC Facebook Post (Figure 14.1)

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

5

3. Introduction

The International Committee of the Red Cross and Crescent Moon (ICRC) has historically been at the forefront of advancement within C4D, an exceptional operational track record and cutting-edge advocacy on international humanitarian law, fundraising and development of industry guidelines. It is one of the oldest global humanitarian organizations (1863) and is documented to be the first organization to use “propaganda” to fundraise (Pinar, 2015). However, the ICRC has an imperfect history. It has been called slow to act; and has been shown to be reluctant to publicly communication on “politically” divisive topics; unwilling to adopt new technologies or adapt to change. The role of traditional ICRC diplomatic and humanitarian communication has been well researched. However, few studies (Maillot, 2017) look into modern ICRC SM communication while considering the historical context. This paper believes that there is fundamental value in understanding how an INGO with a history is responding to the challenges of public advocacy communication on SM. Given the importance of the ICRC historical visual identity, it is interesting to assess if the technological drive of SM has impacted communication style/techniques for the better. Particularly given the importance of ongoing political diplomacy; in the context of the digital power war e.g. the UK government hiring “digital diplomats” (Maillot, 2017); and the potential for being vindicated by “Digilantists”. It is argued that having a winning SM communication strategy is more important than ever. This review should allow the identification of improvement areas for digital diplomacy. As a first mover, ICRC policy on SM would lead the industry through a digital evolution.

SM is one of the fastest growing yet least understood moments of human development in history. The move from traditional media with limited engagement; to a world of fragmented SMPs with individual engagement and a focus on visual identity has transformed how we communicate. SM had the potential to help and hinder INGOs. First let’s review the potential for positive impact. SM enables communicating with

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

6 individuals1 in a new way (Lovejoy et al. 2012). For example, in 2016 more people had

access to a mobile (93%) than access to sewerage (30%) … in sub-Saharan Africa (Mitullah et al. 2016: pp.2). Second, improving their efficacy and fundraising capabilities by reaching more donors (Lovejoy and Saxton, 2012), e.g. peer-peer fundraising campaigns on Facebook2. Finally, cost saving on mass communication thanks to the free

features, enabling new methods for crisis response e.g. big data Disaster Maps from Twitter3 and Facebook4. However, there are a host of potential challenges with the SM

form as well. The continued challenge of representation: communication from INGOs reinforcing colonial stereotypes – “Africa needs our help”; INGOs are complicit in the lack of representation in the media (Chouliaraki, 2006). SM can drive conflict or depoliticizing key issues through “too light” content e.g. Rwandan Genocide. “Light content” can provide an ahistorical understanding of poverty, e.g. the Ethiopian Famine (pp. Dogra, 2013: 3). The digital space amplifies any bad representation or negative narratives through reductive repetition which, with unprecedented speed, repeatedly constructs and popularises a stereotype. For example, Africa underdevelopment is ‘constructed and popularized through ‘reductive repetition’ […which highlights.] Africa’s inadequate characteristics’ (Andreasson, 2005 in Schwarz et al, 2019: 1929). This issue is so prevalent it has led to a genre of development satire mocking the industry. Second, the ‘technologization of action’ (Chouliaraki, 2010) where individuals profess their outrage and act but only ever online. This can lead to radicalization of individuals or expose them to attacks. Finally, the adoption of new tools required education, training

1UNICEF has a huge presence on Instagram with a following of 6.7 Million people (October 2020). Over 6400 posts have been made and UNICEF has a daily post engagement of 20, 000 and hundreds of comments – there is a type of conversation happening that was not happening before: https://www.instagram.com/unicef/?hl=en

2 Example of how you fan raise funds on Facebook using their Fundraiser function: https://www.facebook.com/fundraisers/ . At the time of writing (October 17th 2020) over $2 Billion USD had been raised for nonprofits and personal causes since 2015 and 45 million people have donated or started a fundraiser (Source: about.fb.com). Even NGOs are acknowledging the transformation that this new Peer-Peer donation model has had on their fundraising, Bomber from “No Kid Hungry” campaign calling out the new donations as ‘90% organic, and maybe a little bit more’ (Source: Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhessekiel/2019/09/19/at-2-billion-raised-facebook-fundraising-cant-be-ignored-by-nonprofits/#27113bb6af97 )

3 Digital Humanitarianism – explains how using text and Social Media – Volunteers can map and therefore deploy a response that is proportionate to the need. What is more, it is much more timely than historical “on ground” searches or Ariel assessments from helicopters. The first example of this being extraordinarily effective was in the 2010 Haitian Earthquake when, using OpenStreetMap and text messages from those on the ground, a team was able to map the disaster areas needing highest assistance. More can be found here: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/digital-humanitarianism

4 The Facebook Disaster Map Tool was launched in 2017, it is designed to enable humanitarian organizations to know who is leaving from / moving towards areas of disaster. Fundamentally, it is also helpful because it can show how this picture compares to the local “norm”. For further details see this article from The New Humanitarian by Siefgried (2017)

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

7 and staffing. Without this, SM could simply be a new tool to “impart” the same old information in a unidirectional way. Can SM transform how the ICRC communicate? Or will more traditional diplomacy, visualizations and development stereotypes be maintained across this new media form? The intention was to understand:

• How has a traditional and conservative organization like the ICRC responded to SM? Has

Social Media transformed ICRC Communication? Specifically, when considering the evolution of visual language.

• What is the ICRC visual language communicating on SM? How has the ICRC visual language

evolved with Social Media when compared with: Historical ICRC Communication (i.e. early 1920s-1950s)? And Early Social Media ICRC communication (i.e. early 2000s)? This paper intends to outline a potential way forward for INGO SM management.

This thesis will first ground the reader on the key terms, including a history of the ICRC. Then the theoretical approaches and methodological framework will be outlined. Data analysis of the ICRC Facebook page will be undertaken showing how the ICRC visual language has evolved; links will be drawn to representation and effective communication. Conclusions will be drawn and potential SM reforms for the ICRC, and other INGOs, suggested.

4. Literature Review

4.1 International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

According to Cook et al (2008) the ICRC inhabits a communication ‘Twilight Zone’ (Ibid: 105), caught between the history of private advocacy with utmost neutrality; and the public advocacy that enables attention in the public sphere. These challenges that the organization faces are amplified by the ever modernizing and changing world with transparent and continuous communication updates becoming “the norm”. Cook et al. (2008), Forsythe, (2007) and Moorhead, (1998) all highlight that for the ICRC flexibly adapting to these new norms might be difficult. Here, the history and opportunities of the ICRC organization will be outlined. It will be discussed if the organization is equipped to handle the challenges of the post-cold war, decolonialized world; where nationalist

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

8 and ethnic struggles, terrorism, famines and genocides are escalated by the advancing technology of the battlefield and communication.

The ICRC is an independent and neutral organization established in 1863, that ‘help[s] people affected by conflict and armed violence and promoting laws that protect victims of war’ (ICRC website). Its Mission is: ‘To protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed

conflict and violence and to provide them with assistance.’ (ICRC Website). The ICRC is

an organization that came from a history of strong Swiss nationalism and it is still sustained by its ‘Western Jeudo-Christian values’ (Forsythe, 2007: 62). Like all Red Cross organizations, the ICRC abides by Seven Fundamental Principles: humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, voluntary service, unity and universality. ‘Adherence to these principles ensures the humanitarian nature of the…work and brings consistency to the broad range of activities it undertakes’ (ICRC Website). The structure of the Red Cross Movement should be noted (see Figure 1) as each arm is similarly named, but entirely separate. Here, the terms ICRC and Red Cross will refer only to the ICRC Arm of the body.

Figure 1: Organizational structure for The Red Cross & Red Crescent Movement the

global Humanitarian network of more than 80 million people. (Source: Author constructed from web based searches).

ICRC

Assist & protect victims of armed conflict

Guardian of International Humanitarian Law

Recognise the national societies

National Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies (191)

Assist victims of disasters Humanitarian activities for

the most vulnerable

Raises funds nationally for the global movement

International Federation of Red Cross / Red

Crescent

Co-ordinates international assistance for natural

disaster victims

Supports activities and development of national

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

9 Like any large organization the ICRC has a history and ‘culture’; and a visual identity which influences organization decision making and communication. Historically, the ICRC has led the way in the development of humanitarian communication, the creation of doctrine across a wide range of issues; and it has supported field staff by providing training to ensure safety/security. They used fundamental principles to good effect across thousands of operations: International Humanitarian Law (IHL); Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers; restoring Family Links – including clarifying the fate of missing persons; Economic, Health, Climate & water security; and International Crisis e.g. Natural disasters. These activities are undertaken on behalf of people affected by war (ICRC Website). However, the ICRC has over the years, struggled to prioritize its mandate. Methods of communication; and style of calls to action have changed. Historically the organization has been identified as having ‘a woeful record on public information’ (Foresythe, 2007: 73). They have failed to speak out publicly and denounce tragedies; preferring instead to maintain neutrality. Examples would include: the holocaust (Moorehead, 1998), Biafra in Nigeria (Allen and Styan, 2000: 830), the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela (Forsythe, 2007); ‘remaining publicly silent in the face of continued abuses of individuals’ (Forsythe, 2006: 461). The strong operational track record of the ICRC is undermined by its mixed track record of late and unclear communication. In the age of digital diplomacy, it is fundamental that the ICRC can evolve beyond its opportunities to make digital diplomacy and communication a key tool it its arsenal of Humanitarian Diplomacy (Maillot, 2017).

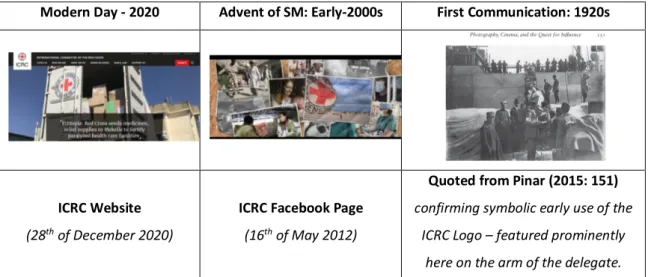

Visually, the ICRC found itself using images of human suffering to appeal for funding as early at 1919 (Pina, 2015: 144). Pina (2015) outlines that this led to the development of a “Propaganda” Unit in 1921; since then visuals have been used to emphasize the result of aid provided on behalf of the organization and the apolitical nature of the ICRC: ‘depict[ing] humanitarianism in its purest form and publish[ing]…engagement with people in need’ (Pina, 2015: 158). Simultaneously a very clear visual language was developed for the organization; which is why, when we think of the ICRC, we think of the consistent assets: ‘symbols on cars, ambulances and the arms of humanitarians’

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

10 (Pina, 2015: 149). Figure Two highlights the prominently display the ICRC Logo across vehicles and people.

Modern Day - 2020 Advent of SM: Early-2000s First Communication: 1920s

ICRC Website

(28th of December 2020)

ICRC Facebook Page

(16th of May 2012)

Quoted from Pinar (2015: 151)

confirming symbolic early use of the ICRC Logo – featured prominently

here on the arm of the delegate.

Figure 2: A Modern Snapshot of the ICRC Facebook Page and Website alongside historic

visuals of the organization.

Today, the ICRC operates in a much more competitive humanitarian field (Moorehead, 1998). Public perception, continued fundraising power and individual advocacy is more important than ever. ‘Once the only body of its kind, the ICRC is now surrounded by similar organizations pursuing the same goals by subtly different means’ (Cook et al, 2008: 105) which ‘invites competition for attention in the public Sphere’ (Ibid: 105). Others realised that photographs were ‘crucial in raising both awareness and funds for humanitarian…agenda’s’ (Fehrenbach et. al.: 2015: 2). The ICRC had started the Arms War; what role could it play in neutralizing it? It is clear that the ICRC is keen to advocate for change, the 2017 launch of the Community Engagement and Accountability Guide (2017)5. How can the ICRC evolve its communication to be more representative and

diverse? While not crippling the private advocacy that occurs behind the scenes? While still using public advocacy to enable fundraising and awareness of its causes?

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

11 This history reveals an organization that struggles with its “raison d’etre”: a desire to help those suffering from conflict and its point of difference: neutrality. This neutral positioning guarantees the organization access and permits reporting clarity. However, in a competitive modern world the ICRC position is imperfect. While there are many that support this notion of an organization constantly striving to improve the lives of others and adjust to new realities; there are others who argue that ‘the ICRC [is] ultra-slow to change, still controlled at the top by excessively cautious traditionalists who are…risk-averse, unilateralist, and slow to recognize gender and racial equality’ (Forsythe, 2007: 64). For this thesis, the idea that the ICRC is not adapting fast enough; and no longer leading the way will be explored through SM communication analysis.

4.2 Social Media

More than half of the world now uses social media (Kemp (2020): 1). That is 3.96 billion users (see Fig. 2 below); with 1 million people joining per day in the last 12 months. The pace of this growth is not slowing, rather, it has ‘accelerated in recent months’ (ibid). The majority of new SM users are joining and interacting on the platforms, especially in the global south. In 2018, 98% of Facebook users were connected via mobile (Forbes (2018):1). Technology usage/adoption varies considerably by region (82% Penetration in North America versus 12% in Middle Africa, Kemp (2020) 2)). Gender disparity is also seen particularly in Southern Asia where only 25% of users are female (Ibid). In short, the people] “online” are not representative of all gender, race, or socio-economic groups.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

12

Figure 3: Quoted from Digital 2020: GlobalStatshot (Kemp (2020))

In this paper SM and SMPs will be used inter-changeably. They were defined by boyd and Ellison (2007) as:

‘web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system.’

Bertot et al (2012) and Lipschultz (2014) agree that it covers the main SM premise: it is designed for social interaction and dialogue i.e. individuals connecting online, using the latest technology, to communicate with variety of media forms. When people are using a new form to develop social groups and create social trends: is important to stop understand (Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955). As SM has evolved so has its user, today SMPs public communication and per-surveillance spaces are driving the formation of new habits. For example, presenting only perfection: idealized self-presentation (Birnbaum, 2013 in Schwarz, 2019: 1930); ongoing feeling of threat from others responses: ‘imagined surveillance’ (Duffy and Chan, 2019 in Schwarz, 2019: 1930); and the entrenchment of established behaviors due to the echo chamber effect e.g. Presidential elections. The importance of these behavior changes and how individuals perceive others and view themselves within the SM space should not be understated. This is influencing willingness to act, engage and interact across SM platforms which is particularly meaningful for INGOs. Second, as SM is leading the new era of visual communication, the most important communication for INGOs, it is great springboard for understanding how INGOs are using this new communication tool.

Numerous SM platforms exist6 and they are fragmented in content and form. Covering

more than one Social Media Platform (SMP) would be ineffective. So, this thesis will focus on drawing learnings from Facebook7. Facebook is the world’s largest SNS with

6Other social media platforms would include: Instagram (also owned by Facebook); Twitter; TikTock; YouTube; QQ (Chinese Parive/Small group Chat); WeChat (Messaging, Social Media and mobile payment App from Mainland China); What’s App (a Private/Small Group Chat service); and Pinterest.

7 The Facebook Mission: ‘give the people the power to build community and bring the world closer together’ (Facebook: Company Info).

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

13 over 2.6 Billion active monthly users (Kemp, 2020: 2). That is double Instagram and eight times Twitter making it the best penetrated SMP globally. In addition, it is the best used SM in the global south, driven by the “low data” Facebook version which can be accessed easily across mobile devices with no data needed. Facebook also enables good engagement from users. It is feasible to have a variety of posts (videos, text, images etcetera). Each post comes with interaction functions that enable individuals to (1) share emotions on the post (Like, Love, Care, Ha-ha, Wow, Sad and Angry); (2) comment (to which others can reply); and (3) share with others through their own profile page. This format makes it more diverse compared with other social networks and makes it possible to measure the quantity and quality of individual engagement.

Figure 4: Visual example of an individual Facebook post: (1) Emotional responses (Like

on the bottom left); (2) Comments from Individuals (See “Comments” bottom right); (3) Share with others (See “9 Shares” bottom right) (Source: ICRC Facebook Page

https://www.facebook.com/ICRC/ , October 18th 2020)

Cho et al (2014: 565/566), classify Facebook engagement into two levels: Low or moderate engagement e.g. using the Like and Share buttons. These simple tools enable individuals to participate. High Engagement: Comments, which can be engagement in discussion with the organization or other users. Here a difference in response levels was perceived by Cho et al (2014: 567), when organizations engaged in two-way symmetrical

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

14 conversation publics were much more likely to engage effectively. Currently, Facebook is not being used by INGOs to engage with the public. Rather, as a tool to convey information.

SM is associated with a number of risks regarding individual protection (from radicalisation, attacks, targeting); data protection (from theft, from discovery) and reputational protection / stigma (as a result of data leaks / poor posting etc). In short, an inappropriate post or comment from an organisation can ruin years of hard work in minutes. This risk level requires careful management and heavy resourcing on two levels: first, on the development of and posting of content; second, on the complex monitoring and tracking to make effective use of the data. It is not yet clear if investment into these resources will pay out for organisations like the ICRC. This is especially true in societies where traditional media still plays an important role in generating and maintaining public conversation, often in countries where SM penetration is lower. Individuals spend more time online versus traditional media by over 2 hours per day (Top Media Advertising, Jan 2020) driven by administrative tasks, including work, that take place online. This trend of SM growth will only amplify with more time spent online. The parallel universes between online & offline highlighted here make the awareness driving role of INGOs even harder. As ICRC works to share real, representative visuals of real humanitarian disasters within a SM world that is increasingly “cultivated” – the juxtaposition can be alarming. It is important for organizations such as the ICRC to move carefully and consistently into the digital diplomacy. See more in the section “Role of

Visuals in SM”.

4.3 Visual Analysis Theory

Visuals were key to the historical development of the ICRC helping it to develop as an organization in global presence and financial status. Given that visual images are also fundamentally important to the evolution of SM, it makes visuals are the natural departure point for a text analysis. However, this visual focus will be advocated for, within a theoretical context, for three reasons: first, the historical relevance of the form to development; second, form accessibility; finally, the role visuals play on SM.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

15

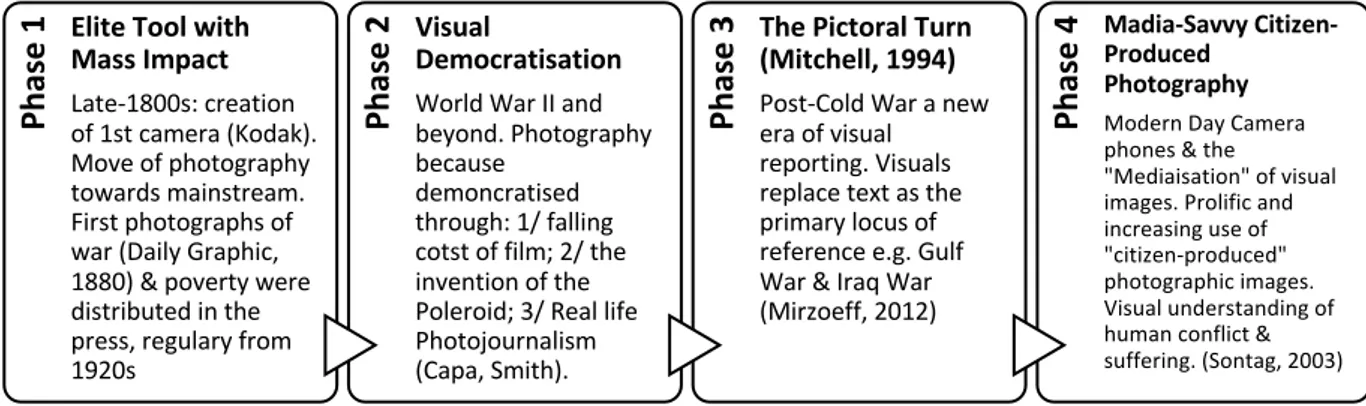

Visuals in Development: A History

The evolution of photography sits in line with the use of visuals in mass communication. As the technology evolved to make photography more accessible, so did the use of visual across mass media. This growth can be divided into four main phases:

Figure 5: Four Phrases of Photography & Visuals in Mass Communication.

Photographs have always been exciting because they offer a unique viewpoint of a moment in time: interesting because of what they show and the truth they imply.

Something worth photographing is an event; photographs are evidence it happened

(Sontag, 1979). Since the turn of the 20th century, photographs have been used to share

newsworthy events and human tragedies across the world. These images of human suffering prompted public responses that involved “taking action” in many forms; but mainly through donations. The funds raised show how effective fundraising can be: e.g. the Tsunami (2004) raised $6.25 Billion (USD) (Kweifio-Okai, 2014). SM has only amplified this responsiveness: e.g., post-Haitian earthquake $9.04 Billion (USD) was raised (Rodgers, 2013). As such, use of images showing human suffering became normalized as “the best way” for INGOs to raise awareness and fundraise. But ‘photographs shock in so far as they show something novel’ (Sontag, 1979: 19); to keep showing novel images, the visuals need to progressively become more shocking images of suffering. After 150 years of giving publicity to human suffering, the mediazation of war and human suffering (Sontag, 2003) is so constant now it no longer feels like “new news”. Highlighting both the importance of visuals for the ICRC on SM, but also the challenge of how to work with this form in that space. This underlines two challenges

Phase 1

Elite Tool with Mass Impact Late-1800s: creation of 1st camera (Kodak). Move of photography towards mainstream. First photographs of war (Daily Graphic, 1880) & poverty were distributed in the press, regulary from 1920s

Phase 2

Visual

Democratisation World War II and beyond. Photography because

demoncratised through: 1/ falling cotst of film; 2/ the invention of the Poleroid; 3/ Real life Photojournalism (Capa, Smith).

Phase 3

The Pictoral Turn (Mitchell, 1994) Post-Cold War a new era of visual reporting. Visuals replace text as the primary locus of reference e.g. Gulf War & Iraq War (Mirzoeff, 2012)

Phase 4

Madia-Savvy Citizen-Produced

Photography

Modern Day Camera phones & the "Mediaisation" of visual images. Prolific and increasing use of "citizen-produced" photographic images. Visual understanding of human conflict & suffering. (Sontag, 2003)

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

16 with the media reliance on visuals. First, continued exposure to dead photographs torn from context (Berger, 2013) and ‘discontinuous to the moment’ (Ibid: 32) where they are seen; it is not possible to shock people any more. Mediazation as ‘dehumanized the suffering of others’ (Chouliaraki, 2006: 107) and resulted in Compassion Fatigue for the ‘Distant others’ (Boltanski, 1999). This can be a very real problem on SM where individuals are exposed to thousands of images daily. Second, photographs have always been a colonial tool, used to reinforce the imperial division of the world (Berger, 2013: 69). The Euro-American centric mass media portrays news from a single cultural perspective and consolidates the economic and political divisions of the world (Chouliaraki, 2006). Moreover, ‘photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention’ (Sontag, 1979: 11); the ‘get your shot, get out’ attitude does not help to drive long term, sustainable, social change. But encourages the ‘boom-and-bust’ reality of humanitarian aid today. How are visuals used by the ICRC on SM today? Does this tool help them to drive a political message without need for words? Can it facilitate their drive for truth?

Maybe. For visuals imply a truthfulness that is unmatchable: the uniqueness of the

photographic image is unbeatable. The camera captures a scene impossible for the human eye to register; hence, photographs are seen as the ultimate truth. Supported by the reliance of law enforcement on images and the continued use of visuals in the press. A photograph is ‘a means of testing, confirming and constructing a total view of reality.’ (Berger, 2013: 20). This is part of their power: photographs might not create a moral position but they can ‘reinforce one – and help build a nascent one’ (Sontag, 1979: 17). However, questioning of visual authenticity is valid. Photographs are only selections from the available evidence. Distrust has existed since the American Civil War; evolving over time with the advancement of photoshopping technology. The veracity of images is no longer taken for granted. Yet, examples of visual manipulation exist across history: Stalin, Mao Tse-tung and Hitler – removing enemies from visuals, and the color manipulation of the O.J. Simpson cover of Time Magazine (Carmody, 1994). This is particularly concerning within the modern world of SM, where truthful representations are rare; rather a studied self is shown to the world.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

17

Accessibility of Photography

Photographs are a medium not yet preserved and protected as an art form; for now, ‘the public [do not] think of photographs as … beyond them’ (Berger, 2013: 17). Photographs taken on smart devices or more traditional cameras are now widely accessible: it is ‘a public medium which [sic] could be used democratically’ (Berger, 2013: 49). This is shown in the recently authority amateur visuals have gained in mass media; ‘the photograph [has come] to symbolize the powerful combination of millions of citizens and their mobile phones’ (Lipschultz (2014): 5). Amateur images now play a vital role in exposing the underside of war and human suffering to the general public. This has, led to a crisis of veracity within photojournalism Becker (2011). However, it does level the playing field for reporting from developing nations; this evolution will be interesting.

Role of Visuals in SM

Since the arrival of SM and smart phones, visuals play a disproportionate role in imagining self and “others”. On SM images are used to share opinions, emotions, and generate individual identities: bringing to life Sontag’s theory that to photograph confers importance (1979: 28). This trend has reach C4D via Digital Humanitarianism where individual volunteers often post images of themselves “helping others”, in this instance the others usually gloriously cheeky children on the African on Asian continents. The vices and virtues of this “Humanitarians of Tinder” trend is immortalized in a website8 and satirized in the famous “Who wants to be a Volunteer?”9 by the

Norwegian Students' and Academics' International Assistance Fund. These satiric pieces tell an important story using humour: it is time for a change in how we visually represent others. This approach respects the growing merging of the online and offline worlds, highlighting the importance of the digital world for processing meaning, particularly for the youth. However, this merge fails to account for the idealised self-presentation which

8https://humanitariansoftinder.com

9 SAIH “Who wants to be a Volunteer?” Satire of the growth of https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymcflrj_rRc

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

18 expresses itself through the constant editing of visuals. People have become desensitized to the gap between SM perfection and reality. This trend can be especially harmful for INGOs who cannot post an idealized version of reality. It would be wrong. So how can these organizations use visuals within this space? A conversation and clear industry leadership from a giant such as the ICRC would go a long way to reset the cultural norms around visual representation.

To conclude, prior to defining visual form, let’s review the other forms available: text only, video or GIF. Video and GIFs imply expertise and financial freedom that is unaffordable. Text as written documents, newspapers or blog posts play an important role in information dissemination. Yet, visuals a new communication form still have the capacity to expand our visual code and ‘enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have the right to observe’ (Sontag, 1979) in a way text does not. To conclude, a visual will be defined as: ‘it presents an event, a seized set of appearances, which has nothing to do with us…or with the original meaning of the event’ (Berger, 2013: 52). Noting that the photographer will always influence the photograph’s nature through construction and interaction with subjects.

4.4 Representation

Representation is the ‘embodying of concepts, ideas and emotions in a symbolic form which can be transmitted and meaningfully interpreted’ (Hall, 2013: xxv). Theoretically there are three possible approaches to representation – reflection, intentional and constructivist. Given analyses the visual nature, a Constructivist approach to representation will be used. For, this considers all aspects of language (written, spoken, visual and signs) to meaningfully construct the world around us. With visuals, the opportunity to reflect on the “total picture” is important of the deeper meaning behind the communication might be missed. For, taking meaning must involve an active process of interpretation; language has to be actively read within the given context, historical period in which it is produced (Hall, 2013: pp. 17). Closely linked to representation is the idea of ‘otherness’ and our relationship with those that are

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

19 different. According to Silverstone (2006) SMP have led to a number of questions about the morality of online communication and the ethics/politics of representation within the online space. He advocates for ‘proper distance’ – arguing that all media users had an unconditional responsibility to imagine other media users through difference as well as shared identity and treat them all morally (Silverstone, 2006: 47 and 770). The notion of ‘proper distance’ will be particularly useful when reflecting on the public engagement of the ICRC postings on Facebook, to help drive clarity on if communal engagement of challenging topics can drive a sense of community and consensus.

4.5 Communication for Development

No single definition captures the Communication for Development (C4D) sentiment. Rather, Enghel’s (2018) definition will be used with important additions. C4D is the ‘intentional and strategically organized processes of face-to-face and/or mediated communication aimed at promoting dialogue and action to address inequality, injustice, and insecurity for the common good’ (Enghel, 2013, p. 119). The additions that should be considered are: First, the impact of SM. Tufte (2017) argues that C4D is ‘being transformed by technology and social innovations…resulting in new methods of action and new conversations on…why communication matters.’ (Tufte, 2017: 4). Second, the importance of “looking good” (Engel, 2018) within the sector driven by: higher visibility; increasing competition for resources; and greater scrutiny from donors driven by more readily available data on all projects10. The need ‘to communicate the good done, via

information and public relations’ should not be underestimated (Enghel (2018): 1). Finally, the role of the individual who plays the lead role in their own development. C4D should help individuals understand their ‘options for change…to help people plan actions…to help people acquire the knowledge and skills’. (Fraser et al, 1998: 63 –

10 SM become common place at around the same time new donors in the development sector were moving to change norms (Fejereskov et al, 2015). Since, 2005 Development became more focused on aid effectiveness and results; from 2015 this was documented through the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Marketisation of the development industry has led to the development of strong competition. (Chouliaraki, 2013: 6). This is around the time that continuous monitoring and tracking from the field became feasible and affordable. The internet and SM enabled tracking and easy sharing of data. It is not possible to isolate either moment; however, it is important to note that the late noughties and early-2010s saw a big shift in the way iNGO’s and other development organisations received funding. This is, in part, due to the arrival of organisations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) who were a Foundation Giant with huge influence.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

20 Quoted in Lennie et. Al, 2013: 4). The definition employed will be the overarching notion of the above thoughts.

5. Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

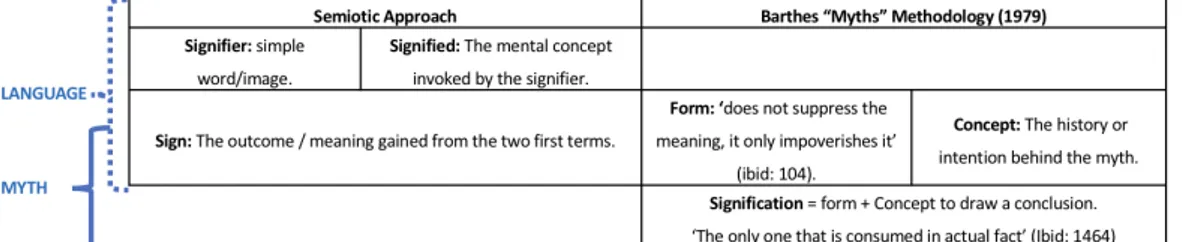

Within the constructivist approach, the textual analysis will be completed using Semiotic methodology. This method, from Saussure, was selected due to the visual nature of the text: images can have multiple signifiers this methodology enables the viewer to remove all layers of culture and history within the narrative and start at the beginning; prior to adding them back in. However, Barthes considers context and history as an enabler of effective text interpretation. For, discourse provides the framework within which understanding can take place. Barthes (1957) argues that, over time, objects/items become charged with ideological meaning and, therefore, come to represent certain political and social ideas of how the world should be. These messages are known as Myths. A Myth ‘is a language’ (Barthes, 1957: 41); and a ‘type of speech’ defined by its intention (Ibid: 1268); and a double system, depending your focus what you perceive will be different. One thing is certain, without understanding the history that led to the text creation, we understand nothing. Even Saussure was convinced that meaning and representation are open to history and change.

Given that the ICRC has considerable history within development; it is argued that makes sense to consider the historical, political and social context when interpreting the text. What is interesting for this thesis are two parts of Barthes idea: the double system and the notion of a language. This author argues that understanding these nuances help viewers to take a new perspective: “looking from the outside in.” In organizations with a strong history and well-established culture being able to alter the focus and review your actions/communication in a new light is key for the resolution of representation challenges or the realities of post-colonial influences. For, this author believes that this methodology unlocks, even for the most involved individuals within an organization, the ability of individuals to pause, reflect and recognize the “other systems” point of view. Here, a visual analysis will be used to attempt to throw light on the hidden language and

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

21 culture of the ICRC which is influencing the ability of the organization to be a truly diplomatic communicator.

The study will therefore be conducted using the Barthes (1957) approach to the Semiotic Analysis (see Figure 7). The following method will be used: Step 1) Denotation - bringing together the physical elements; Step 2) Connotation – association of cultural and societal values to the text; 3) Myth – Summary of 1 and 2 within the world view of the reader.

Figure 7: The structure of Barthes (1957) Mythological Approach to Semiotic Analysis

when compared to the purely Semiotic Approach, Adapted from (Ibid: 1360).

6. Methodology 6.1 Participants

The sole researcher for this study was the author. The comes with strengths and limitations that will be discussed later.

6.2 Research Design

A qualitative approach was selected to determine how the ICRC was using visuals across SM. It was deemed the best approach to understand visual detail. For the Case Study, the researcher selected the organization based on the historical understanding of the ICRC as explained previously. Similarly, why Facebook was chosen is covered earlier in this paper. Conclusions drawn can be extrapolated across ICRC communication; however, SM learnings will be specific to Facebook alone given the study scope. The main method of study will be document analysis. The initial research approach was guided by a preliminary landscape assessment; for, there is a vast amount of data

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

22 available across Facebook – an initial upfront data review should be conducted to enable an effective theoretical selection. An analysis was undertaken (5 Days, August 2020) on the content and engagement of three Red Cross Facebook pages; aiming to understand both the theoretical approach; and compare the regularity, content, and nature of postings. The organizations were selected from the Facebook Search tool. Here, language was a limiting factor, as this author searched in English only11.

ICRC Syrian Red Crescent American Red Cross

# posts /day 3-4 times 2 2-3 times

Type of posts Mix: text, blog, visuals & videos. Mix: visuals & text. Mix: visuals, videos & blog posts.

Amount of Engagement

200-2000 Likes per post. 20-1000 comments. 10-80 shares.

500-2000 likes per post 20-250 comments Less than 10 shares.

2-800 likes per post 20-100 Comments 20-300 shares

Response? No. No. No.

Figure 8: Landscape Assessment of Red Cross Facebook pages across various

organizations to understand posting methods & engagement protocols.

These data confirm that the ICRC Facebook page falls within Red Cross posting norms: similar number of posts per day; content; and levels of engagement. Importantly visuals are consistently used by all three organizations. Consequently, a Foucault-style visual analysis will be undertaken to provide an in-depth commentary on key images; additionally, these “new SM visuals” will be compared to historical images from early SM and early days of the ICRC. All posts contain levels of engagement from individuals; interestingly, limited organizational responses are observed. One key difference was noted between the pages: both the Syrian and American organizations posted on 3 main topics; the ICRC posted on ten topics. This emphasized the need to develop classification system for the type of content; this step was added into the data collection system.

6.3 Data Collection

Data collection started with a learning phase – September 7th through 13th 2020 – to get

a base range for the ICRC Facebook page. The objective was to understand the

11 However, one of the top hit pages was the Syrian Red Crescent. It should be noted that the author could not understand the posts on the Syrian Red Crescent page without the help of the Facebook translation tool; however, this does not limit the understanding of the frequency of posting and levels of engagement.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

23 regularity, diversity and visualizations of the ICRC content. Once regular posting was confirmed (up to three times per day); with diverse topics (different on each set of daily postings); and frequent engagement (interactions were 100+ per post, so 300+ per day); it was decided that a medium timeframe could be considered for data collection. Data collection was conducted over a six-week period between the 15th of September and

the 27th of October 2020. A total of 138 posts were posted by the organization during

this timeframe, all were analyzed. Given the pandemic, posts were gathered from a similar time period during 2019, acting as a control. The form and content of the posts was predominantly the same, with necessary addition of COVID posts in 2020. These posts can be found in Appendix Four.

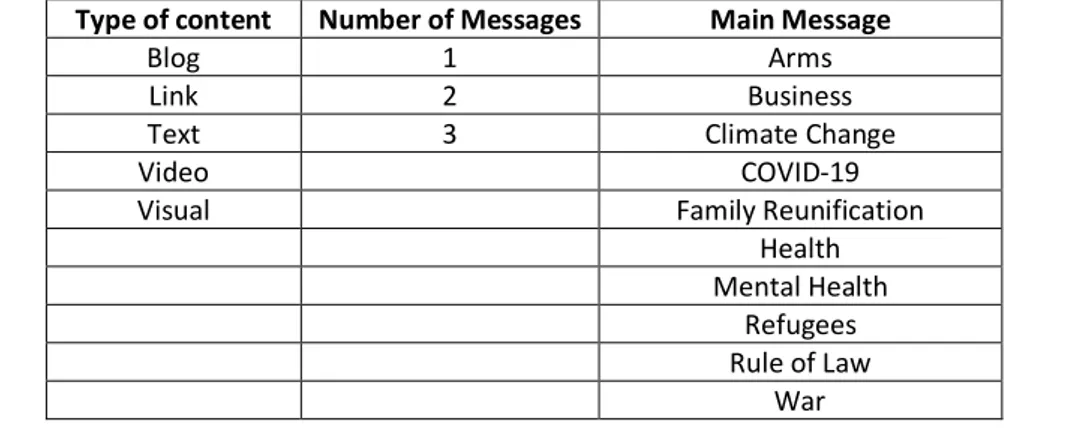

During the research, Facebook Posts were collected daily and placed within an excel datasheet. Posts were categorized immediately on inputting in three different ways: first, type of content for the post; second, the number of messages in the post; finally, the message for each post. In cases where posts were classified to have more than one message, posts were assigned to the primary or main message of the Facebook post.

Type of content Number of Messages Main Message

Blog 1 Arms

Link 2 Business

Text 3 Climate Change

Video COVID-19

Visual Family Reunification

Health Mental Health

Refugees Rule of Law

War

Figure 9: Summary table showing the categorization steps for the ICRC Facebook

content pulled from their Facebook page during a six-week period on Autumn 2020.

Data categorization was undertaken by the researcher. As such, the analysis and resulting categorization represents the perception, cultural/intellectual background and interpretation of the researcher. This researcher bias is a considerable limitation of the methodology. No matter the attempts at mitigation, the researcher is a product of her environment (Kuhn in Ogden, 2008: 61). Raised in a Westernized Culture, there are

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

24 inevitable biases from education and upbringing which will have influenced the visual analysis. One researcher completed all categorization, so at least all posts are treated to the same biases. Efforts were made to limit bias in three ways: first, choosing an extended time-period; second, developing clear classification systems to limit deep thinking and enable easy content categorization. Finally, deciding factors for analysis were made based on numerical classifications to limit further bias introduction. Further, mitigation is limited to self-awareness and acknowledgement from the researcher that she is inseparable from the process. All efforts will be made to look for contradictory data and to be open to alternative interpretations.

To complete the research, the intention was to interview both an ICRC communications specialist and an individual ‘represented’ by the content. The researcher failed to identify an ICRC interviewee willing to participate in the study. The individuals represented on the ICRC Facebook page are protected via the norms of data protection. So, these individuals were not possible to reach. The final option assessed was reaching out to individuals who were commenting on the ICRC Facebook Posts. However, these individuals are not representative. First, limited by the researcher’s language, they would need to be able to communicate in either French or English; second, they already have access to the internet suggesting above-average socio-economic status; finally, individuals who are already engaged enough to comment are likely to have an established opinion on the cause which might not be representative. So, sadly, this leg of the research plan was not completed.

6.4 Data Validation

The qualitative research conducted was verified and validated by assessing its credibility, confirmability and transferability. The research process description explains the tasks performed to enable replication, should individuals wish to repeat the study. This notion of replicability supports the credibility of the research.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

25 The result of the study was clear: The ICRC continues to use old-fashioned visual imagery to raise awareness of human suffering for both fundraising and brand awareness. The organization is imprisoned by the power of its historical identity. The analysis identifies issues that might be similar across NGOs: 1) prolific content without thought regarding reach, sharing or representation; 2) limited capacity or funding to develop new or different visual content; 3) limited capability to tailor-make communication messaging strategy for SM.

6.5 Data Analysis

The ICRC’s Facebook page was reviewed for a six-week period between the 15th of

September and the 27th of October 2020. The analysis commenced once the data

collation was completed with topline results outlines above. During this timeframe the organization made one hundred and thirty-eight posts of which twenty-seven, twenty percent, were repeat postings12. The posts created can be divided into ten main clusters

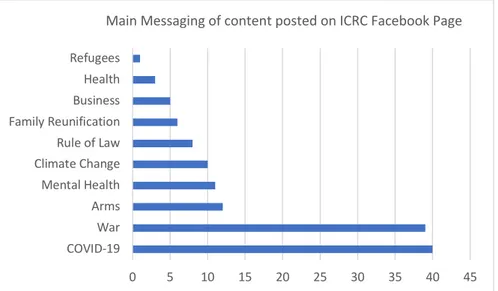

(per researcher classification) that covered everything that was posted ranging from Business and Family Reunification; through to arms, war and rule of law (Figure 4).

Figure 10: Breakdown out the main messaging from the posts on the ICRC’s Facebook

page over a six-week period from mid-September until end-October 2020.

12Here a repeat posting is defined as either: repetition of exactly the same content in terms of visuals and text; or the reposting of the same visual/video content/blog post with a slightly different introductory text. This definition is the authors alone, despite considerable efforts, it was not possible to find another definition.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 COVID-19 War Arms Mental Health Climate Change Rule of Law Family Reunification Business Health Refugees

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

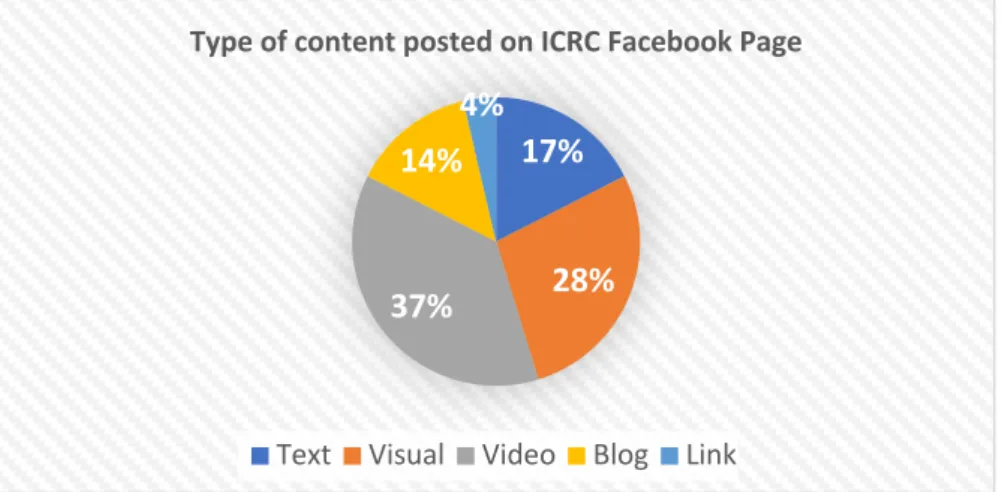

26 While 43% of the posts contained only one message, 50% of posts contained at least two messages, and 7% three (Appendix 1). This should be considered when reviewing the data as specific territories are disproportionately impacted by this: e.g. Rule of Law, which is closely linked both Arms and War and is often a supporting message. Overall, the social media message content is impressively in line with the organization’s focus areas. The ICRC is visibly pursuing their aims as outlined in their global charter. Of these one hundred and thirty-eight posts, the split across the type of content shared was balanced across form: text, visual and video. Interestingly, perhaps driven by the complex nature of its content, the ICRC also posts a large number of posts that are linked to their blog. The posts contained a visual and introductory text but the reader must link to the blog for further detail. It was decided to categorize these separately from visual posts for the introduction of another medium brings complexity. This removed a number of interesting visuals from the analysis. Noteworthy in their presence, no matter the small size, were the links to other organizations or news articles. These were rarely shared and, as such, the 4% run rate identified here feels artificially high. This was due to the successful ratification of the Nuclear Weapons Treaty during the chosen period.

Figure 11: Breakout of the type of media posted on the ICRC Facebook page during a Six-week period

from mid-September through end-October

Once all non-visual forms were removed, thirty-eight posts were of interest for analysis. From here the ten repeated13 messages were removed, leaving twenty-eight Facebook

13As outlined above: a repeat posting is defined as either: repetition of exactly the same content in terms of visuals and text; or the reposting of the same visual/video content/blog post with a slightly different introductory text. This definition is the authors

17% 28% 37%

14% 4%

Type of content posted on ICRC Facebook Page

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

27 posts in consideration. Then all multi-message content (posts that contained messaging on two or more topics) was de-selected. Once all dual message content was removed (fifteen posts), there were only thirteen single benefit visuals remaining. Each post was chosen for the single-minded nature of their commentary. How to select from within these posts? It was decided to analyze a post each from the top two content areas: COVID-19 and War (per Figure Four). A set of criteria was established for selection; it was decided this should be based on a readily available comparable metric. So, engagement level per post was selected: measured as the sum of: reactions + comments + shares. See Appendix Two and Three. From these data, two visuals were chosen and analyzed using a Semiotic Visual Analysis. They will then be compared to a historical image and an early Facebook image (around 2011-14) to review visual identity evolution. Finally, the engagement will be discussed. First, the posts will be classified within the PEM (Grunig and Hunt, 1984); then the levels of the engagement discussed.

alone, the author failed to find others with a definition of this phenomenon suggesting that everyone interprets repeat posting as just that.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

28

7. Analysis: Visual Identity and Engagement

Barthes (1957) argues for visuals to be understood within a historical and cultural context; for example, the fundraising context of an INGO. The ICRC page maybe liked by, and commented on, by global users; but posts are in English and content is geared towards the audience who will donate. However, it is still vital to first using Semiotics to help remove the “filter” and better imagine the photographic intent. Both approaches will be employed to enable the best analysis.

Visual One: ICRC “COVID-19” post

Figure 12.1: ICRC “COVID-19” post, selected from the thirty-eight visual posts shared on

the ICRC’s Facebook page during this time period.

Supporting Text: “What happens when you can’t study from home? In Colombia, we’ve

helped 834 children continue their studies with school kits and 1,300 face masks.”

Visual One (Figure 12.1) Denotation: Four children in brightly coloured clothes, flip flops

and blue face coverings stand with both hands up in front of a white vehicle.

Visual One (Figure 12.1) Connotation: The children in the image seem happy and

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

29 vehicle – smaller than the window; and their response to having their photograph taken – joyful and excited. They are carrying big backpacks which, in many cultures, connotates travel or, more normally, school. The children are wearing light summer clothes implying that it is warm where and when the photo was taken. They are also wearing facemasks. This is something that, only recently outside of Asia, has become associated with stopping the spread of a virus, COVID-19. Generally, masks are only worn when it is not feasible to socially distance from others or people are inside. Given that, in the photo, the children are outside it implies that either: 1) the children have just come from an inside location, supporting the idea that they have been in school; or 2) they have just received the masks from the 4x4 vehicle. This vehicle implies travel across difficult terrain to reach this location. The side of the car displays an internationally recognised symbol: a red cross. This signals neutrality for medical personnel or a Local “Red Cross” providing humanitarian aid. The car itself – big, practical – is a juxtaposition to the smiling children and sunny conditions. The visual implies that the car has brought happiness to the children. Finally, the children also appear to be alone (although the adults could be out of picture) which indicates that they are taking a well-known journey within their neighbourhood. Interestingly, in current times, many children in other countries have yet to return to school driven by the continued spread or the virus and divisive positions on mask wearing.

Here it is interesting to reflect on two points. First, the positive moment of

representation with smiling children. Traditionally, the media and IGCOs paint a helpless

picture of developing countries, using a Euro-American global view with its discourse of normalied inequality (Joye, 2009). Distant sufferers (Boltanski, 1999) are presented as “Others”. The media demands no action from the viewer – the ‘Politics of Pity’ (Boltanski, 1999: 7) or urges them ‘care for [the suffering] and potentially act on the represented misfortune’ (Joye, 2009: 45). These representations reinforce negative stereotypes; dehumanize the suffering of others (Chouliaraki, 2006: 107); and consolidate colonial power divisions. Personal understanding and response to others is derived from how we imagine them. Imagination is fed by the content people see;

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

30 continued exposure to negative representations will lead to harmful responses towards poverty and difference. Development organisations should portray a more normalised global view. Here, the ICRC has departed from human suffering norms; instead, happy children are shown post-school. This step away from the myth that development organisations can only raise awareness through suffering makes the image much more impactful. Reinforcing, visually, a positive image of Colombia, a country stereotypically associated with internal conflict (FARC) and the drugs trade (Narcos). This is “the new style” of humanitarian communication: focusing on positive success stories alongside the “brand message” to generate public loyalty and ensure support. In this sense, resetting the Myth. However, the ICRC is also repositioning the suffering of others and transforming it into something more acceptable and relevant, more western. This development is called post-Humanitarianism (Chouliaraki, 2013: 5).

Second, is enforcing the Western importance of “getting an education” onto other cultures a form of colonial propaganda? This focus on education highlights that, in this respect, the organisation has not evolved much since 1921. In Western culture school and education is perceived to be very important; it is seen as the pathway out of poverty. In this instance, the ICRC is supporting this cultural viewpoint by celebrating the return to school thanks to Facemask and school kit donations. This reinforcement of specific cultural values on to another culture is colonial. In addition, if you read the supporting text associated with the visual, the post feels self-congratulatory and self-interested: ICRC are taking this opportunity to donors by showing positive images of the work that the organization undertakes.

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

31

Visual One Comparative Reflection

Figure 12.2: Historical Facebook Post

from 28th of December 2015

Supporting Text: Lebanese Red Cross ambulances and ICRC vehicles at the Syrian border ready to depart to Beirut airport following the hand-over of wounded persons evacuated from Zabadani. Photo: ICRC/ T. Wheibi

Figure 12.3: Historical ICRC visual from

the late 1800s (ICRC Website,

https://www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-150-years-humanitarian-action )

Supporting Text: Danish military ambulance, 1878. The 1864 Geneva

Convention established a unique

distinctive emblem (a red cross on a white background) for ambulances, hospitals and medical personnel. Other emblems were introduced at a later date, in particular the red crescent.

The ICRC has a clear visual identity. The white vehicles emblazoned with the Red Cross are familiar, either through lived experience or from the news. All ICRC media visual modern and historic, demonstrates that this visual language is one they are proud of. Over time the evolutions seen are limited to: logo evolution and the types/numbers of vehicles used. The logo has evolved to include the organization name; and, in some territories, replacing the red cross with the red crescent to represent the public being served. Outside of this there has been little change. This is for good reason, the logo was signed into International Law (Geneva Convention, 1864) and has since played an important protection role of medical staff and facilities. Until the 1990s the emblem was largely respected; since then there has been growing concern about the respect for the

K. S. Lloyd-Thomas; Communication for Development: HT20 One-year MA: 15 Credits - Autumn 2020

Supervisor: Anders Hog Hansen

32 neutrality of the Red Cross in zones of war14. This is why, perhaps, in Figure 12.2 you see

such a large number of logos: in a war zone the organization does not want their neutrality and medical assistance to be in any doubt.

Visual Two: ICRC War Post

Figure 14.1: ICRC “War” post, selected from the thirty-eight visual posts shared on the

ICRC’s Facebook page during this time period.

Supporting Text: “No school should look like this. In Yemen, over 2,000 schools have

been damaged or destroyed by war. An estimated 2 million children are out of school.”

Visual Two (Figure 14.1) Denotation: A man is standing in front of a group of individuals

sitting on the floor. He is talking to them. They are in a building which is in very bad condition. There are no windows, the floor is falling into the room below. There is exposed metal work from the inside of the walls and floor.

14Emblem and Neutrality – these emblems provide protection for military and medical services and relief workers in armed conflicts (ICRC, 2010). The use of these emblems and logos is clearly defined in law. For further details – please refer to: