A late Neolithic glass scraper from Berthåga churchyard near Uppsala,

Sweden

Kresten, Peter

Fornvännen 2002(97):4, s. [295]-297 : ill.

http://kulturarvsdata.se/raa/fornvannen/html/2002_295

Ingår i: samla.raa.se

Korta meddelanden

A Late Neolithie glass scraper from Berthåga churchyard near Uppsala, Sweden

In the area surrounding Berthåga chapel and churchyard, about 3.5 km west of Uppsala city centre, are eleven registered ancient monu-ments: graves, b u r n t stone mounds, and other settlement sites. Due to a planned expansion of the churchyard, a special investigation of the si-te was carried out in May i g g 5 by archaeolo-gists of the National Heriiage Board, Depart-m e n t of Archaeological Excavations, Uppsala (Fagerlund i g g s ) . During tke first days of work, a r o u n d e d lump of glass, about fist-sized, was found and was discarded as being appa-rently recent material. The subsequent find of a glass scraper initiated an intensive search for tke glass lump, but to no avail.

In May i g g ? , a preliminary survey of" tke area was carried out, resulting in tke recovery of fifteen glass piéces, dassified as flakes and ckips. O t h e r finds included tools and flakes of flint and quartzite (Fagerlund 199g).

The glass scraper

T k e scraper (fig 1) has a maximum length of 4.6 cm, maximum width 12.5 cm, thickness 7 cm, and a weight of 17 g. The glass is dark ycl-lowish green , transparent and appears to be homogeneous. A tiny stringer of translucent greyisk wkite glass occurs near tke surface. Muck of tke item is covered witk a dull, yel-lowisk grey coating, apparently an alteration c r u s t T k e knapping technique used to make the scraper is identical to the one used for flint and quartzite tools at the site and is typical for tke Late Neolitkic and Early Bronze Age (K. Tkorsberg, quoted by Fagerlund iggg), c.

2350-1500 BC. T h e scraper was retouched witk a kigh precision pressure technique typi-cal for tke period in question.

Fig. 1. The glass scraper from Berthåga churchyard.

markable find. Determining the age of the glass was thus of paramount importance. Gam-ma ray spectrometry carried ont on the scraper al the Studsvik research reactor b y j . Chyssler revealed the presence of uraniinn-thoriiim de-cay series elements.

Furtker gamma spectrometric measure-ments were carried out by P. Ros, Department of Radiophysics, University of Lund. Flakes taken from the scraper were dissolved in H F / H N O , , , followed by extraction, ion ex-change ckromatography, dectrodeposition, radon bubbling (for 2 2 t'Ra) and alpha

spectro-metry (for other isotopes). T h e following re-sults were obtained: 238U 0.82, 234U 0.82,

a j o j j ] , . 1 , 2 2 6R a g g > a n d 2 i oP b 3 j m B q af.

ter correction for a blank sample. T h e results indicate near-equilibrium conditions for ura-iiium and tkoriimi as well as an excess of radi-um. As the starting composition with respect to radioelements remains unknown, no precise age determination can be made. However, the glass has to be at least several h u n d r e d years old.

Age of lhe glass

A Late Neolithie to Early Bronze Age glass scra-per recovered in Sweden would be a truly

re-Chemical composition

Analyses of a splinter from tke back of tke scra-per witk the electron microprobe at tke

296 Korta meddelanden Weight-% S i 0 2 T i Oa A l20 3 FeO t o t MnO MgO CaO N a20 K20

p

8o

5 Cl Total Bertiiäga gl Mean 54-85 0 . 1 5 6 . 1 4 1.16 0 . 7 0 3.21 2 1 . 6 6 2-79 5 - 36 2.22 0 . 4 6 9 8 . 7 0 ass scraper Std. Dev. 0 . 6 0 0 . 0 2 0 . 0 8 0 . 0 4 0 . 0 3 0 . 0 3 0 . 2 3 0 0 9 0 . 0 6 0 . 1 2 0 . 0 3 1 55.86 0 . 2 2 2 . 5 0 0 . 8 2 1.28 4.06 23-69 2.58 5 . 1 0 3-34 0 . 4 0 99-85 2 56-34 0 . 0 5 6 . 4 1 0 . 1 5 0 . 7 1 2.62 2 0 . 4 8 1.72 4.24 3-92 96.64 3 55-23 °-53 1 0 . 0 4 7-94 0 . 4 2 2.91 1 4 . 4 8 1.84 4-79 1.80 9 9 - 98i Medieval potash-lime-glass, average of 30 analyses (Wedepohl 2 Greenish window glass, Hessen,

3 Light gl manufactured AD 1 4 73.80 1 3 . 7 0 2 . 3 0 0 . 1 2 1.00 4 . 8 0 4 . 0 0 99-72 '993) 5 79-3° 0 . 8 0 1 1 . 2 0 2-37 0.11 1.30 1.92 0.51 3 . 0 0 1 0 0 . 5 1 090 (Bezborodov ig75:XI) ass, Roman a n d / o r Medieval, Pavia (B. Messinga, pers.

4 Obsidian, Iceland (Barnes & Barnes ig6o) 5 Tektite, average moldavite (Barnes & Barnes 1 9 6 0 )

comm. iggg)

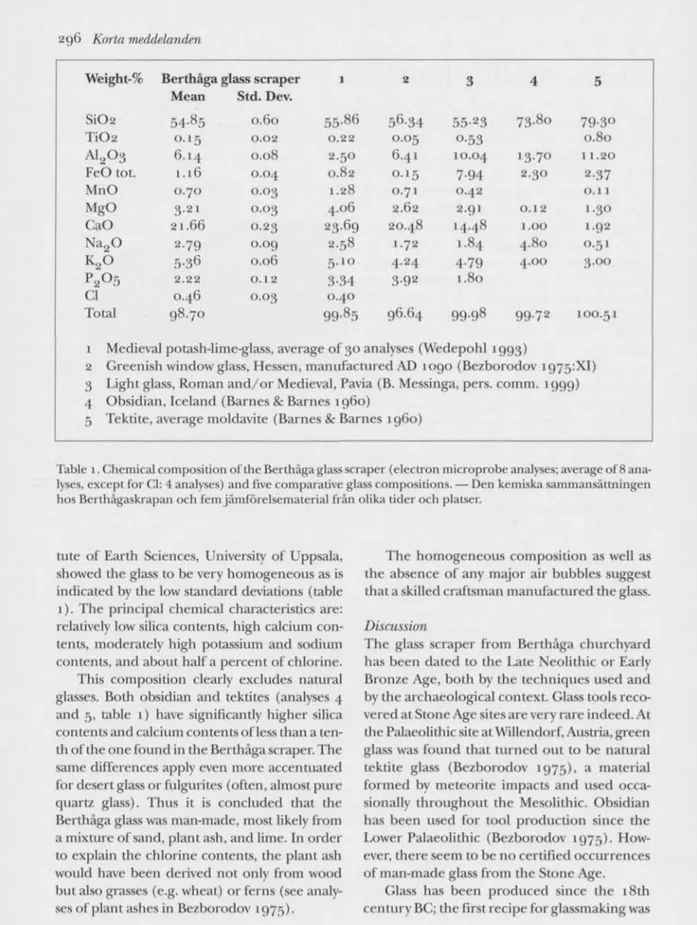

Table 1. Chemical composition of the Berthåga glass scraper (electron microprobe analyses; average of 8 ana-lyses, except for Cl: 4 analyses) and five comparative glass compositions. — Den kemiska sammansällningen hos Berthågaskrapan och fem jämförelsematerial frän olika tider och platser.

tute of Earth Sciences, University of Uppsala, showed the glass to be very homogeneous as is indicated by the low standard deviations (table 1). The principal chemical characteristics are: relatively low silica contents, high calcium con-tents, moderatdy high potassium and sodium contents, and about half a percent of chlorine. This composition clearly excludes natural glasses. Both obsidian and tektites (analyses 4 and 5, table 1) have significantly higher silica contents and calcium contents of less than a ten-th of ten-the one found in tke Bertkåga scraper. Tke same differences apply even more accentuated for desert glass or fulgurites (often, almost pure quartz glass). Tkus it is c o n d u d e d tkat tke Bertkåga glass was man-made, most likely from a mixture of sand, plant ask, and lime. In order to explain the chlorine contents, the plant ash would have been derived not only from wood but also grasses (e.g. wheat) or ferns (see analy-ses of plant ashes in Bezborodov 1975).

T h e homogeneous composition as well as the absence of any major air bubbles suggest that a skilled craftsman manufactured the glass.

Discussion

T h e glass scraper from Berthåga churchyard has been dated to the Late Neolithie or Early Bronze Age, both by the techniques used and by the archaeological context. Glass tools reco-vered at Stone Age sites are very rare indeed. At tke Palaeolithic site al Willendorf, Austria, green glass was found tkat turned out to be natural tektite glass (Bezborodov 1975), a material formed by meteorite impacts and used occa-sionally throughout the Mesolithic. Obsidian has been used for tool production since tke Lower Palaeolitkic (Bezborodov 1975). How-ever, there seem to be no certified occurrences of man-made glass from the Stone Age.

Glass has been produced since the i8th century BC; the first recipe for glassmaking was

Korta meddelanden 2g7

found in tke library of Assurbanipal (Bezboro-dov i g 7 5 ) . However, all ancient and Roman glasses are soda glasses (Bezborodov i g 7 5 , Wedepokl i g g 3 ) , typically containing about 65-70% silica, 6% calcium and 16% sodium. Consequently, the hypothesis of the Berthåga glass as import goods, e.g. from the eastern Mediterranean, can be ruled out.

Medieval glasses have higk calcium contents, and some of tke compositions show distinct si-milarities to the Berthåga glass (analyses 1 and 2, table 1). Could the glass scraper represent a lump of Medieval glass, knapped into a scraper by some practical joker? Probably not. The knapping took place some time ago, as the al-teration crust covering much of the object ta-kes time to develop. Pressure flaking and re-touching techniques, on the other hand, were only reconstructed by archaeologists fairly re-cently.

If the Berthåga scraper does not represent an import from the Mediterranean, and is not a recent fake made of Medieval glass, we are left only with the option of prehistoric glass pro-duction. T h e glass would then represent a dis-covery of the process, i n d e p e n d e n t of the glass production in the eastern Mediterranean. Abundant chips and flakes of glass at the site in-dicate that the scraper (and other glass tools?) was made at Berthåga. Whether or not the glass was a local produet, or if the material was im-ported from elsewhere (much like the flint that probably derives from southern Seandinavia) must remain an open question.

A cknowledgements

Jan Chyssler (Studsvik), Kerstin Engdahl (Stock-holm) , Dan Fagerkind (Uppsala), Hans Harry-son (Uppsala), Per Ros (Lund), and Kalle Tkors-berg (Uppsala) have been of assistance, which is gratefully acknowledged.

References

Barnes, VE. & Barnes, M.A. 1960. Comparison of chemical composition and magnetic properties of tektites and glasses formed by fusion of terre-strial rocks. Nature 187. London.

Bezborodov, M.A. 1975. Chemie und lechnologie der antiken und miltelalterlichen Gläser. Mainz. Fagerlund, D. 1995. Berthåga. Arkeologisk utredning

Berthåga kyrkogård. Uppsala kommun, Uppland. Riks-antikvarieämbetet, UV Uppsala rapport 1995:25. - 1999. Berthåga. Elt boplatsomräde från yngsta

slen-älåer eller äldsta bronsålder. Arkeologisk undersök-ning. RAA 545, Berthåga kyrkogård, Berthåga

11:12, Bond-kyrko socken, Uppsala kommun. Upp-land. Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV Uppsala rapport. Kresten, P. 1999. Analys av glasskrapan från

Bert-håga kyrkogård. Dnr 421-2346-1995, Bond-kyrko sn, Uppland. Geoarkeologiskt Labora-torium, Analysrapport nr 9-1999.

Wedepohl, K.H., 1993. Die Herstellung mitleUillerlirher und anliker Gläser. Abhandlungen der mathema-tisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse Jahrgang 1993, Nr 3. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart.

Peter Kresten Riksantikvarieämbetet Geoarkeologiskt laboratorium Portalgatan 2 A 754 23 Llppsala geodata@hotmail.com Fornvännen gy (2002)