and Communication

The impact of extramural English on students’

willingness to communicate in an EFL context

A mixed-methods study with upper secondary school students in Sweden

ENA314 English for Teachers in Secondary Robert Csanadi

and Upper Secondary School: Degree Project Supervisor: Olcay Sert Term: Autumn 2020

School of Education, Culture Degree project

and Communication ENA314 15 hp

Autumn 2020

ABSTRACT

This study explores the possible relationship between extramural English (EE) and students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) in the EFL classroom in the Swedish upper secondary school. The study employed a mixed-methods approach, and the data was collected through a questionnaire and interviews. The results of the study suggest that EE usage positively affects students’ language proficiency and their self-perceptions of their English ability, which in turn is beneficial for their WTC in all contexts inside the classroom. The results also show that the students who spend the most time in EE contexts reported higher levels of WTC than the non-frequent users of EE. Productive EE activities were also found to be more beneficial for raising students’ WTC than receptive activities. The connection between EE and WTC is, however, not absolute since a minority of the students reported a high frequency of EE but low WTC, which indicates that several other factors might also be influencing upper secondary school students' WTC.

______________________________________________________________

Keywords: Extramural English, L2, willingness to communicate, upper

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Background ... 2

2.1 Extramural English ... 2

2.2 Willingness to communicate ... 4

2.3 The link between extramural English and willingness to communicate ... 7

3 Method ... 8

3.1 Participants and context ... 8

3.2 Data collection ... 8

3.3 Data analysis procedures ... 10

3.4 Ethical considerations ... 12

4 Results ... 12

4.1 Results from the questionnaire ... 12

4.1.1 Reported extramural English activity ... 12

4.1.2 Reported willingness to communicate ... 13

4.1.3 Analysis of the relation between extramural English and L2 willingness to communicate ... 15

4.2 Results from the interviews ... 17

4.2.1 Extramural English use ... 17

4.2.2 Willingness to communicate inside the classroom and the effects of extramural English 18 5 Discussion ... 19

6 Conclusion ... 22

List of references ... 24

Appendices ... 27

Appendix 1– The questionnaire ... 27

List of Figures

Figure 1 Model of WTC (MacIntyre et al. 1998, p.547) ... 5 Figure 2 The amount of time spent on EE sorted by number of participants ... 12 Figure 3 Contexts where EE is used shown as receptive and productive activities sorted by percentage of participants in the study ... 13 Figure 4 Overall WTC sorted by number of participants ... 13 Figure 5 WTC in two different classroom contexts sorted by the number of participants and their reported levels of WTC ... 14 Figure 6 Time spent on EE compared to the average overall WTC score inside the classroom ... 15 Figure 7 Reported WTC in two different contexts inside the classroom compared to the

frequency of EE use ... 16 Figure 8 The everyday use of only RA compared to the everyday use of PA in terms of in-class WTC ... 17

List of Tables

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my special thanks to my supervisor, Olcay Sert, for providing invaluable guidance and motivation throughout this research project. I would like to thank him for sharing his knowledge, for always finding time to assist me whenever I needed it, and for his friendliness. I would also like to thank my close friend, Pontus Lindström, who also supported and helped me with various problems.

1 Introduction

In the modern, globalized Swedish society, exposure to the English language is common. Many people use English on a daily basis to communicate with others, for example in international meetings at work, while playing video games online, or while video chatting with international friends. Furthermore, the Swedish National Agency for Education highlights the importance of being able to communicate in English and claims, in the

curriculum, that knowledge of English “increases the individual's opportunities to participate in different social and cultural contexts, as well as in global studies and working life”

(Skolverket, 2011b, p.1). This statement in the curriculum shows that the English language is important for both educational and social reasons in Sweden.

Nowadays, the Internet and high-tech technological devices, among other things, expose us to the English language like never before, and students have infinite possibilities to engage with and learn the language outside of the classroom (henceforth referred to as extramural English (EE) (Sundqvist, 2009)). Previous research (see e.g., Olsson, 2011; Reinders & Benson, 2017; Richards, 2015; Sundqvist, 2009; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012) has shown that EE provides rewarding learning contexts that increase language proficiency and acquisition outside of the classroom. However, despite the ever-increasing exposure and possibilities to learn English, and the fact that the curriculum states the importance of communicative competence, many teachers face a common problem: some students are unwilling to participate in communication in class.

Participation in interaction is a crucial ingredient for language development inside the classroom, and the ultimate goal of teaching English should be that the students use English as a means of communication. However, to achieve this goal, learners must be willing to communicate inside the classroom. So, why is it that some students are unwilling to

communicate, while others are very much willing and always try to seize the opportunity to use English inside the classroom?

The willingness to communicate (WTC) in a second language (L2) is affected by several factors, such as speaking anxiety, language proficiency, L2 self-confidence, and the context in which the communication takes place, to name a few (MacIntyre et al., 1998). Since EE has proven to increase learners’ language proficiency and self-confidence (e.g., Sundqvist 2009), this project examines if students’ interaction with EE affects their WTC inside the classroom.

Empirical research on the connection between EE and WTC is scarce. By investigating whether there is a link between EE and WTC, I hope to contribute to the growing body of research on why students’ WTC differs in upper secondary school classrooms. The aim of the present study is, therefore, to examine if EE activities affect upper secondary school students’ WTC in a Swedish upper secondary school context, and also if different types of EE and the time spent on these activities affect WTC differently. With this aim, the following research questions will be addressed:

1. What kind of extramural English activities do the participating students engage with? 2. In what ways do the participating students’ extramural English activities affect their

WTC in English inside the classroom?

In order to tackle these research questions, I will employ a mixed-methods approach to investigate a possible relation between EE and WTC. In what follows, I will review research on EE and WTC.

2 Background

In this section, I will provide an overview of previous research regarding both EE and WTC separately, and on the relation between them.

2.1 Extramural English

Sundqvist (2009) defines Extramural English (EE) as “the English learners come in contact with or are involved with outside the walls of the classroom” (p.1). Following this definition, EE can be described as all experiences in English that take place outside of the classroom. These contexts can include activities like playing video games, watching TV, reading books, or communicating in English in online communities. Additionally, Sundqvist states that her definition of EE only includes English learning that is initiated by the learners themselves, and not by their teachers. Thus, the engagement with EE can be considered as voluntary since learners can choose whether to interact with it. Another aspect of EE is, according to

Sundqvist, that it can be both deliberately and non-deliberately used to practice English. This means that some learners intentionally use English outside of school with the aim to improve their language ability or knowledge. On the other hand, others may incidentally acquire language, for instance, vocabulary, while engaging in specific activities, such as online

gaming or reading, where learners’ focus is on the activity rather than the learning process (Hulstjin, 2003).

Some typical EE activities, listed by Sundqvist and Sylvén (2016) are: Watching TV series, movies and video blogs, reading books, blogs and magazines, playing video games (online or offline), interacting with people in English online or face-to-face, and following people, organizations, news etc. on social media. Naturally, there are many other examples of EE, and Sundqvist and Sylvén even claim that since almost everyone in a modern society today has access to the Internet, the opportunities for EE seem infinite.

The question of whether EE is beneficial for L2 acquisition has generated a growing body of research recently (see e.g., Olsson, 2011; Reinders & Benson, 2017; Richards, 2015; Sundqvist, 2009; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). What has frequently been claimed in these studies is that EE contexts provide language learning

opportunities that allow the learners to practice their language more, to a greater extent, and in a lower anxiety environment than the English classroom provides. Furthermore, research has shown that there is a positive relationship between EE and the students’ self-perceived language ability (Lee & Dressman, 2018)

Sundqvist (2009), and Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) studied the effects of gaming as an EE activity and found that it is highly beneficial for language proficiency and vocabulary learning (Sundqvist, 2009; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). Their studies show that frequent gamers outperform those who play less or not at all in terms of L2 ability and vocabulary. Furthermore, Sylvén and Sundqvist argue that online games are better for language

development than offline single-player games, as the online games often include some kind of inter-player interaction, in written form and/or through audio and video modalities. Wood et al. (1976, p.90) introduced the term scaffolding to explain how interaction with more capable peers can provide temporary support for a learner. In a scaffolded interaction, the learner is temporarily supported by an expert or a more capable peer, which allows them to reach higher levels of language comprehension than they would in an unsupported environment. Sylvén and Sundqvist, therefore, claim that since online games include inter-player interaction, they can stimulate scaffolded interactions among players, which can assist language learning further.

Another study on EE was conducted by Olsson (2011) who investigated whether EE impacts the written proficiency of Swedish 16-year-old learners of English. She analyzed two different types of texts produced by the participants, a letter and a news article, and used a

questionnaire and a language diary to map her participants’ EE activity. In her study, Olsson found that frequent and extended contact with EE is beneficial for several aspects of writing proficiency, mainly: richer vocabulary, sentence length, and the ability to adapt different texts to different contexts. Furthermore, she claims that there is a connection between frequent exposure to EE and high grades in the English school subject. However, Olsson does not imply that students with little or no contact with EE perform poorly inside the classroom, but instead that those students that engage a lot with English in their spare time outperform the others.

In the above-reported studies on EE, the main focus has been on investigating the immediate connection between EE activity and language proficiency. Adding on the previous research cited in this section, my study aims to investigate another possible beneficial effect that EE may have on language learning. By looking into the connection between EE and students’ WTC, I attempt to contribute to the literature on the positive effects of EE on students’ classroom participation practices.

2.2 Willingness to communicate

The study of willingness to communicate (WTC) can be traced back to McCroskey and Baer (1985) who investigated first language (L1) WTC. The researchers argue that “an individual’s willingness to communicate in one context or with one receiver type is highly related to her/his willingness to communicate in other contexts with other receiver types” (p.7). Thus, what McCroskey and Baer suggest is that WTC refers to personality-based qualities that are consistent across different communication contexts. However, there are differences between L1 and L2 WTC. According to MacIntyre et al. (1998), L2 WTC is defined as “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using an L2” (p.547). With this definition, the authors suggest that L2 WTC is situation-based and, therefore, not consistent across different speaking contexts as previously claimed by

McCroskey and Baer. The study of MacIntyre et al. is significant since they differentiate L1 and L2 WTC. There are, according to the authors, several factors that affect one’s WTC in L2 that are isolated from L1 WTC, such as language proficiency and communicative

competence. They claim that language proficiency in L1 is assumably very high for most speakers, while L2 proficiency “can range from almost no L2 competence (0%) to full L2 competence (100%)” (p.546). The definition of L2 WTC provided by MacIntyre et al. is

highly relevant in this study since it aims to investigate the connection between EE and WTC at a specific time in an L2 context; in the case of this study, the English classroom.

In their study, MacIntyre et al. (1998) identified 30 variables that could affect L2 WTC at a specific time and created a pyramid model that shows how and why the variables could be influential on L2 WTC (see Figure 1 below). Briefly, their model can be divided into 12 boxes in two sections. The first section corresponds to the top of the pyramid (layers I-III) and shows that certain situation-specific factors can affect the WTC of any speaker at a given moment in time. Situation-specific factors, such as knowledge of the topic, confidence in the situation, and the receivers, can influence a speaker’s (un)willingness to communicate in the L2 in certain situations but not in others. The bottom of the pyramid (layers IV-VI) forms the second section of the model, which represents stable and lasting influences on WTC. These include personal traits such as confidence, communicative competence, motivation, and personality.

As the model shows, the different layers are split into 12 boxes that represent several factors explaining why WTC differs among various speakers, as well as within every speaker. Indeed, the model can be helpful to recognize why some individuals are willing to

communicate in their L2 with some people in one particular context and why the same individuals might hesitate to speak in other situations.

The pyramid model has inspired researchers in recent years to study its applicability in L2 learning contexts and considerable attention has been given to L2 WTC. Many researchers have validated the model of MacIntyre et al. (1998) and investigated different aspects of L2 WTC. In a meta-analysis, Shirvan et al. (2019) examined the results of multiple scientific studies and identified three key variables that had the most significant influence on L2 WTC: perceived communicative competence, language anxiety, and motivation. According to their meta-analysis, perceived communicative competence, namely an individual’s self-perception of their L2 proficiency and ability to communicate, is the most significant influence on L2 WTC. The higher pupils perceive their communicative competence, the higher their level of WTC will be. Furthermore, Shirvan et al. have also found that language anxiety is closely related to WTC. Language anxiety is defined by MacIntyre et al. (1999) as “worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when using a second language” (p. 27) and can thus be traced back to negative experiences with the L2. Lastly, the third key variable to high L2 WTC identified by Shirvan and colleagues (2019) is motivation. The motivation to use and learn an L2 is positively associated with language proficiency and perceived communicative competence and, thus, it is closely connected to the other two variables. This means that motivated students tend to perceive their communicative competence higher and have lower language anxiety than less motivated students (Yashima, 2002).

Although the aforementioned model of WTC (Figure 1) represents many factors that influence an individual’s “readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using an L2” (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p.547), only a few of the boxes in the pyramid are relevant in this study: box 7. L2 Self-Confidence, box 8. Intergroup Attitudes, and box 10. Communicative Competence (p. 547).

L2 Self-Confidence is the individual speakers’ confidence in their L2 ability, which can

be related to actual competence in the L2 (MacIntyre et al., 1998). This means that increased language proficiency may boost L2 self-confidence, which in turn can lead to increased WTC. However, other factors, such as fear of making mistakes inside the classroom, have been found to reduce L2 self-confidence, which, consequently, affects WTC negatively (Fager 2020). According to MacIntyre et al., Intergroup Attitudes refers to the identity and

membership pupils have within the L2 community, and an increased affiliation can thus affect their motivation to learn the L2. The enjoyment and satisfaction of being part of the L2

motivation towards acquiring the language, which thus may improve WTC (MacIntyre et al. 1998; Peng and Woodrow 2010).

Most important for this study, however, is box 10: Communicative Competence. MacIntyre et al. (1998) argue that “one’s degree of L2 proficiency will have a significant effect on his or her WTC” (p.554), and that experience with oral and written communication is vital for the individual speaker’s communicative competence. As mentioned in 2.1, L2 learners’ EE activities have proven to improve language proficiency, which in turn has shown to increase L2 WTC. The following section, therefore, focuses on the aim of this study, namely the correlation between EE and WTC.

2.3 The link between extramural English and willingness to communicate

Even though research on EE and WTC has mushroomed in the last decade, empirical research on the link between EE and L2 WTC inside the classroom is still scarce. Previously,researchers have focused on how EE affects the learners’ WTC while engaging in a specific activity (See e.g., Lee, 2019; Lee & Dressman, 2018; Reinders & Wattana, 2014). Reinders and Wattana (2014) used a digital game to show that games have a positive effect on WTC. They found that before playing the game, the students felt anxious, had low confidence in their L2 ability, and were unwilling to communicate. After playing the game, however, the participants showed increased confidence, less anxiousness, and more WTC in English. Reinders and Wattana argue that the anonymity games offer creates a low anxiety atmosphere for the learners. However, since the digital game in Reinders and Wattana’s research was teacher-initiated, it fails to qualify for the definition of EE in this study. Nevertheless, similar results could be expected from student-initiated gaming since it, too, presents a low anxiety language context (Rama et al., 2012).

In a recent study, however, Lee and Drajati (2019) examined the effects of EE activities on L2 WTC in a digital context. In their research, they separated the EE activities into two subgroups: receptive activities (RA), and productive activities (PA). RA focus on activities where the learner only needs to understand something in English, for instance listening to music and watching tv-series in English, while PA require the learner to take initiative to produce communication in English, such as verbal or written communication in online

communities. Lee and Drajati found that all kinds of EE activities affect learners’ WTC in the informal digital context, which is in line with previous research (Lee & Dressman 2018; Reinders & Wattana, 2014). The findings of this research are noteworthy, since the

researchers also discovered that PA, where the learner is required to participate in and

produce either verbal or written communication, was directly related to the learners’ WTC in non-digital contexts, such as inside the English classroom. Hence, Lee and Drajati’s results indicate that EE activities influence the WTC of EFL learners inside the classroom. Therefore, emphasis should be put on inspiring the students to participate in productive EE activities to increase their in-class WTC.

3 Method

In the following section, an overview of the methods used in the study will be presented along with the data collection and analysis procedures.

3.1 Participants and context

A total of 54 students, 16-19 years of age, from two different classes in the second year of a Swedish upper secondary school participated in a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) that was designed to map their EE activity and WTC in the classroom context. The participants were estimated to be between B1 and B2 levels according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFR (Skolverket 2011a, p.4). In the questionnaire, the students had the option to fill in their email addresses if they wanted to participate in a follow-up interview, and out of the 54, two participants were then selected and contacted again for the interviews (for the selection procedure, see 3.2). The interviewees were both boys from the same class and had the same teacher. Due to the 2020 COVID19 pandemic, both the

questionnaire and the interviews were conducted online. To maintain the validity of face-to-face interviews, an online-video chat-software was used, rather than using emails or phone calls (Denscombe 2009, p.28). Although I was not allowed to be present while the students were filling in the questionnaire, a small pilot study (with three participants) was conducted in advance to foresee any problems of comprehension. Following the pilot study, some minor modifications, regarding small issues such as formulations of questions, were made in the questionnaire.

3.2 Data collection

Both quantitative and qualitative means of data collection were employed. A questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data on the participating students’ EE activity and L2 WTC inside the classroom. Following the questionnaire, and drawing on the data that came out of it,

two qualitative interviews were employed as well. This methodological combination is, according to Dörnyei (2007, p.164), useful to enrich findings when investigating complex matters, such as student WTC, which could be affected by several factors. Thus, a quantitative analysis of data from the questionnaire was used primarily to investigate the possible

relationship between EE and L2 WTC, and the subsequent interviews were then conducted to further explore the results from the quantitative data.

To collect the quantitative data, a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) that was split into two parts was used to map the participant’s EE activity, and to get an overview of the students’ WTC inside the classroom. The first part of the questionnaire (10 questions) was designed to map the participant’s EE behavior. This part provided nominal data on the different kinds of EE the participants engage with, and how much time they spend on it daily. The second part of the questionnaire (7 questions) addressed the participants’ WTC in two different contexts inside the classroom. Context 1 addressed communication with other peers only (3 questions), while Context 2 involved communication with the teacher and other peers (4 questions). The questions regarding WTC were adapted from Lee and Drajati's (2019) questionnaire, and the answers were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= definitely not willing; 5 = definitely willing), providing ordinal data on in-class WTC (Denscombe 2009, p.329).

Following the analysis of the data generated by the questionnaire, two participants were selected to participate in follow-up qualitative interviews. The sampling procedure was based on the data from the questionnaire, and the chosen participants were specially selected based on the probability that they would provide the most valuable data, since their answers either verified or challenged the relationship between EE and WTC (Denscombe 2009, p.37). The interviews were personal, semi-structured interviews, meaning that one participant was interviewed at a time using pre-determined questions. However, during the conversation, the informants were also given space to develop their own thoughts and ideas (Denscombe 2009, p.234). Based on Lee (2019), the interviews aimed to gain further insights into the

participants’ EE habits and their WTC inside the English classroom. To achieve this aim, authentic questions based on the participants’ own responses were used, which allowed the participants to discuss their EE activity and WTC further without being driven by the questions. In addition, each interview lasted around 20 minutes and depending on the participants’ proficiency skill or preference, the interviews were conducted in Swedish or English. Both interviews were recorded digitally with the permission of the participants, and they were transcribed immediately after the interviews were conducted.

The selected participants (henceforth Student A and Student B) were representatives of two different kinds of profiles. Student A frequently used EE and had high levels of WTC, and Student B frequently used EE as well but had low levels of WTC. Thus, Student A was selected to possibly validate the accuracy of the findings from the questionnaire, and Student B was selected since the results showed that frequent exposure of EE do not always correlate to high WTC. The selection was made to reinforce the research findings and to create an in-depth understanding of the kind of factors that affect L2 WTC (Denscombe 2009, p.152). This mixed-methods approach allowed me to expand and enrich the data and knowledge of how and if WTC correlates with EE activity. By selecting a few informants with varying degrees of WTC, I could further investigate the connection between EE and WTC from a different perspective.

Initially, the analysis of the quantitative data from the questionnaire generated three different student profiles, the previously mentioned Student A and Student B, but also Student C, who reported non-frequent EE use and low levels of WTC. However, due to different circumstances, none of the students who matched the profile of Student C wanted to

participate in the follow-up interview. Due to the lack of qualitative data on why non-frequent EE users’ WTC is lower than frequent users, the scope of the data analysis was, thus, limited in this study.

3.3 Data analysis procedures

To analyze the raw data from the questionnaire, the data had to be organized. The nominal data on the participants’ reported EE, from the first part of the questionnaire, were organized based on frequency: non-frequent EE use (≤ 1 hour spent on EE daily), and frequent EE use (≥ 2 hours spent on EE daily) (see Figure 2 in 4.1). The different kinds of reported EE

activities were then sorted into two groups: receptive activities (RA), and productive activities (PA) (Lee & Drajati, 2019). RA include activities where the user needs to understand spoken and written English. PA requires the performer to produce language, spoken or written, in interaction with others. This categorization was necessary to test the correlation between different kinds of EE and WTC.

The second part of the questionnaire generated ordinal data which allowed me to sort the participants into groups based on their WTC. In the seven questions in the questionnaire regarding WTC, the participants rated their WTC on a 5-point Likert scale. To get an overall understanding of each participant’s WTC, they were scored 1-5 points on each question,

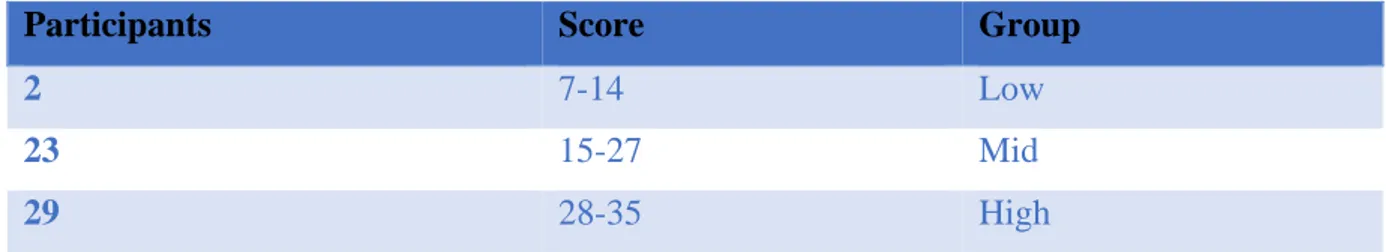

making the possible overall scores range from 7-35 points (7= lowest possible overall WTC, 35= highest possible overall WTC). Following the scoring process, the participants were categorized into three groups based on their WTC score, low WTC (7-14); mid WTC (15-27); high WTC (28-35) (see Table 1). The low-group is characterized by students that are not willing to communicate, the mid-group by students who are willing to communicate in the classroom to some extent, and the high-group by students who are willing to communicate to a greater extent. During the data analysis, the mid-group was, alongside the high-group, considered to consist of students that were willing to communicate inside the classroom. To test the possible relation between EE and WTC, the results of the two different parts of the questionnaire were merged. Firstly, the connection between time spent on EE activities and overall WTC were analyzed. Secondly, the WTC of the two different groups of participants, sorted by frequency of EE use (non-frequent, and frequent), were examined in connection with the two different contexts of communication (see 3.2). Lastly, the participants’ reported overall WTC was analyzed together with time spent on RA and PA respectively, in order to examine if different types of EE produced different in-class WTC.

Table 1 The categorization process of the participants’ reported WTC

Participants Score Group

2 7-14 Low

23 15-27 Mid

29 28-35 High

To analyze the data from the interviews, Content Analysis was employed (Denscombe 2009, p.307). Each interview was transcribed immediately after the meeting, and the ones held in Swedish were translated into English. To process the data, each interview was then re-read several times, and the statement was coded and sorted into groups. Since the interviews were used as a complement to the questionnaire to expand the findings on whether, and if so how, EE correlates to in-class WTC, the statements were labelled and sorted as either EE, WTC, or EE + WTC. Additionally, all data that was not related to this study was discarded from the analysis. During this process, I organized, connected, and analyzed the students’ answers according to the two different parts of the questionnaire.

3.4 Ethical considerations

Throughout the study, the Swedish Research Council’s ethical principles and

recommendations have been followed (Vetenskapsrådet 2017), which means that the participants’ rights, dignity, and integrity were considered. Each participant was informed about the purpose of the study and their role in it. It was also explained that participation in the study was voluntary and their participation could, without any consequences, be ended at any time if they asked for it. It was made clear that everything that was said will be reported confidentially. Prior to both the questionnaire and the interviews, it was also made clear to the participants that their identity would be anonymized in the study so that they would feel safe and secure with their participation and with sharing their thoughts and personal information.

4 Results

4.1 Results from the questionnaire

In this section, I will present the results from the analysis of the quantitative data generated by the questionnaire. The first two parts of the section show the results from the participating students’ reported EE and WTC, respectively. The third and final part of the section shows the results of the analysis of the possible relationship between EE and WTC.

4.1.1 Reported extramural English activity

The first research question was to investigate what kind of EE activities the participating upper secondary school students engage with. The results of the first part of the questionnaire show the participants’ behavior regarding EE. Figure 2 shows that all the participants engage with English outside of the classroom and that a vast majority spend a considerable amount of time on it; 45 out of the 54 participants reported a high frequency (≥ 2 hours daily) of EE

0 9 15 16 14 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

never use 0-1h/day 2-3h/day 4-5h/day >5h/day

N u m b er o f p ar ticip an ts

activity. Figure 3 reveals that the participants engage with a lot of different kinds of EE and that they engage with receptive activities (RA) far more frequently than productive activities (PA). Practically all participants engage with some kind of RA (music, TV, reading), while

only approximately 50% of them engage with PA (speaking and writing). A great majority of the participants, 73%, also reported that they engage with video games. However, since video games can include both receptive and productive elements, depending on the context, it is not counted as either a RA or a PA in Figure 3.

4.1.2 Reported willingness to communicate

The results of the second part of the questionnaire show the participants’ reported L2 WTC inside the classroom. As Figure 4 reveals below, the participants had an overall high WTC, with only two participants reporting low overall WTC (unwillingness to communicate) inside the classroom. Furthermore, a common feature in the mid-group was that the participants had

2 23 29 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

low mid high

Overall WTC

Figure 4 Overall WTC sorted by number of participants

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Music/podcast TV/YouTube Reading Speaking with friends/family

Writing Video games

Perc en ta ge o f all p ar ticip an ts in th e stu d y RA PA Undefined

Figure 3 Contexts where EE is used shown as receptive and productive activities sorted by percentage of participants in the study

high WTC, that is, they were to a great extent willing to communicate in most of the contexts but were unwilling or only to some extent willing to communicate in others, giving them a lower overall WTC. For example, 30% of the students in the mid-group reported high WTC in all but one context where they reported low, as is indicated by the analysis of the

questionnaire question 14: I am willing to speak in English when I give a presentation/speech

in front of the class (Appendix 1). This means that they, to a great extent, are willing to

communicate in most situations inside the classroom.

Figure 5 shows that the different contexts have a significant influence on students’ WTC. Most noticeable is the increase in the number of participants with low levels of WTC in Context 2, communication with the teacher and other peers (see questions 13, 14, 17, 19 in Appendix 1). In this context, 26% of the participants reported an unwillingness to

communicate in English, while Context 1, communication with other peers only (see

questions 15, 16, 18 in Appendix 1), show that only 3% are unwilling. Some participants also portray a large individual variation of WTC between the contexts. For instance, one student reported high WTC in Context 1, communication with peers only, but low WTC when the interaction took place in Contexts 2, communication with the teacher and other peers. The results, therefore, indicate that the participants, overall, have high levels of WTC, but also that different contexts affect, and can also play a significant role, in their WTC inside the

classroom. 2 14 17 13 35 27 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Context 1, peers only Context 2, teacher and peers

N u m b er o f stu d en ts Willingness to communicate

low mid high

Figure 5 WTC in two different classroom contexts sorted by the number of participants and their reported levels of WTC

4.1.3 Analysis of the relation between extramural English and L2 willingness to communicate

To answer the second research question, In what ways do the participating upper secondary

school students’ extramural English activities affect their willingness to communicate in English inside the classroom?, I merged and analyzed the data from the two different parts of

the questionnaire in three steps. The first step in the analysis of the possible relation between EE and L2 WTC was to investigate whether the participants’ overall WTC mirrored the frequency of their EE use. As Figure 6 shows, there is a clear tendency that indicates that the more time students spend on EE the higher their levels of WTC will be inside the classroom.

Non-frequent users of EE (≤ 1 hour spent on EE daily) reported the lowest average of WTC score (21.8), and that the most frequent users of EE (>5 hours spent on EE daily) reported the highest average of WTC score (29.5) (for an explanation of the scoring process, see 3.3). Figure 6 also indicates that the most frequent users of EE were the only group that averaged high WTC overall. Furthermore, the increase of overall WTC score between the different groups of the frequent EE users is minor (2 points on average), compared to the increase from non-frequent to frequent EE use (3.7 points). Thus, this result shows that the average students who spend >5 hours on EE activities every day have high levels of WTC inside the

classroom.

The second step of the analysis of the possible relation between EE and WTC was to compare the frequency of EE use with WTC in two different contexts inside the classroom. Figure 7 below shows that frequent users of EE outscore the non-frequent users of EE in both

21.8 25.5 27.25 29.5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

0-1h/day 2-3h/day 4-5h/day >5h/day

W TC SCO R E TIME SPENT ON EE

Context 1, communication with peers only, and in Context 2, communication with the teacher and other peers. Only 25% of the non-frequent users of EE reported high levels of WTC in both contexts, whereas 75% of the frequent users of EE reported high levels of WTC in Context 1, communication with peers only, and 57% in Context 2, communication with the teacher and other peers. Figure 7 additionally indicates that the number of non-frequent users of EE who are unwilling to communicate increase from 8% in Context 1, to 33% in the more demanding Context 2, while the increase in the group of frequent EE users was only 7%. This

indicates that students that spend much of their spare time on EE activities both have a higher overall WTC in all contexts and that their WTC stays more stable between different contexts of varying pressure.

Lastly, Figure 8 below illustrates the final step in the analysis of the relation between EE and WTC from the questionnaire. The figure shows the results of how the two different types of EE activities, receptive activities (RA) and productive activities (PA), affect students’ L2 WTC. To test this relation, only the participants that used RA or PA every day were

included, regardless of how much time they spent on them daily. To create analyzable data, the participants were only counted once, that is, the participants who engaged with both RA and PA every day were only included in the PA group. In fact, most of the students included in the PA group did engage with both RA and PA daily. 24 participants only engaged with RA daily, and 25 participants engaged with PA every day. As Figure 8 shows, there seems to be no difference in the number of students who are somewhat willing to communicate (mid and high groups). What the figure shows, however, is that EE in PA produces more than twice the number of students with high levels of WTC as RA does. Also noteworthy in Figure 8 is

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Context 1 Context 2

non-freqent EE use

low WTC mid WTC high WTC

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Context 1 Context 2

frequent EE use

low WTC mid WTC high WTC

that all 49 participants used for the figure engage with EE every day, which implies that the type of EE activity students choose to engage with, can influence their in-class WTC.

In summary, the results suggest that there is a relation between EE activity and students’ L2 WTC. In all the investigated cases, EE positively influences students’ WTC inside the classroom. Furthermore, the results show that the average student’s WTC increases in tandem as their EE activity increases and that the frequent users of EE show a higher, and more stable, overall WTC throughout different contexts.

4.2 Results from the interviews

In the following sections, I will present the results based on the analysis of the interviews. The questions in the interviews (see Appendix 2) were related to the participants’ answers in the questionnaire to provide deeper insights into their EE habits and their WTC.

4.2.1 Extramural English use

To answer the first research question: What kind of extramural English activities do the

participating upper secondary school students in Sweden engage with? and to further explore,

and if possible, validate the data from the questionnaire, Student A and Student B (see 3.2), were asked to describe their EE use and the contexts of their activities.BothStudent A and Student B reported a high frequency of EE (≥ 2 hours daily) in the questionnaire. Both interviewees claimed that online communities, such as massively multiplayer online games (MMO), or online chat software solutions, such as Discord, were their main sources of EE.

1 1 15 7 8 17 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 RA PA

low WTC mid WTC high WTC

I play lots of Fortnite and I speak a lot of English during the game. (Student A)

I use Discord and there I meet friends online. I join different servers where I meet new people. We play, chat, speak, and watch movies together. I have found many international friends this way and we speak only English. (Student B)

EE seems to be beneficial for increased language proficiency, both when learners use it deliberately and non-deliberately.

I use English when I play games and watch YouTube and TV-series. […] I feel confident in my English and I think it’s mostly because I use English so much at home. (Student A)

I want to learn and become better at English, so I use it intentionally at home […]. I watch Netflix with English subtitles to learn more. I look-up words I don’t know and use the synonym function [while writing on the computer]. […] it [the English language] is important for future work and for my spare time. I really want to learn English. (Student B)

The participating students’ EE is, thus, characterized by being used in informal digital, online contexts. Both of the participants mentioned that their English proficiency has increased as a consequence of their EE use, which indicates that it is beneficial for language acquisition, even if the language is not deliberately used to learn.

4.2.2 Willingness to communicate inside the classroom and the effects of extramural English

The results from the analysis of the quantitative data indicate that there is a relation between EE and WTC. However, the questionnaire did not provide any data on other factors that might be influencing the students’ WTC inside the classroom. As mentioned previously, both of the interviewed students reported high frequency of EE use; however, Student A reported high levels of WTC while Student B reported low levels. Therefore, to broaden the perspectives received from the questionnaire and to extend the findings, Student A and Student B were asked to describe their feelings regarding communicating in English, both in- and outside of the classroom, and if they saw any benefits in high EE use.

The results indicate that the WTC inside the classroom is affected by the learner’s L2 self-confidence.

I feel that my English is good […] it is as easy for me to speak English as Swedish [in terms of speaking inside the classroom] (Student A).

I used to be very shy [inside the classroom]. I did not speak English because I couldn’t speak [due to lack of proficiency]. I did not want to make errors in front of everybody (Student B).

Furthermore, Student A, with high levels of WTC, claimed to be more willing to

communicate inside the classroom than in an online community, while Student B, with low levels of WTC, claimed the opposite.

I prefer to talk at school because there I can see the people I talk to and I know them too, which makes it easier (Student A).

With people on Discord of my age and with my interests, I dare [to speak] more. The anonymity online [allows me to] avoid confrontation. At school, you have to be perfect, at home it is more relaxed […] and I only talk to those I want to talk to (Student B).

Both informants believe that EE develops their English ability and that it helps them inside the classroom as it raises their WTC.

As I said, I was shy before, but it's better now. Studying English at home has helped me a lot in school (Student B).

My English knowledge comes a lot from using it at home. It has helped me get better […] I gain knowledge about communicating on the Internet. The school is more formal. You learn difficult and advanced words and other things that are not used in everyday life. I use everyday language in a different way [while communicating online] (Student A).

The results from the analysis of the qualitative data, thus, indicate that the participants’ EE use, indeed, is beneficial for the WTC. However, the results also show that other factors, such as shyness due to lack of L2 self-confidence affect students’ WTC inside the classroom. This suggests that some students need the anonymity that online communities can offer to become more confident, while other students who have higher levels of L2 self-confidence are more comfortable to communicate inside the classroom.

5 Discussion

To answer the research questions, and to investigate whether, and if so how, EE is beneficial for students’ L2 WTC, both their EE exposure and classroom WTC had to be mapped. The results from the questionnaire indicated that all the participating Swedish, upper secondary school students interact with some kind of EE on a daily basis and that a vast majority of them spend a lot of their spare time (≥ 2 hours daily) in an EE context. The most common activities

reported by the students were RA, such as listening to music/podcasts and watching

Tv/YouTube, which virtually every participant engaged with daily. Video games were also a common EE context, followed by reading. PA, which require the students to produce

language in written or spoken communication, were less common. Yet, nearly half of the participating students did speak or write every day, and both Student A and Student B claimed in the interviews that the majority of their EE originates in online communities and games where they interact with other people. EE has been proven to be beneficial for language acquisition and language proficiency (see e.g., Sundqvist, 2009; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012), and high language proficiency has, in turn, been shown to play a significant role in student WTC (MacIntyre et al. 1998). In the interviews, both students claimed that their EE habits have improved their language proficiency significantly, which supports the theory that EE is beneficial for language proficiency and simultaneously for WTC.

At the same time, the questionnaire showed that Swedish students are generally very willing to communicate. Almost all students claimed that they are either to some extent or to a great extent willing to communicate and only two students reported an unwillingness to communicate in the L2 classroom. However, the results also showed that the context of the interaction affects students’ WTC. Most of the students in this study are willing to

communicate in small groups with peers, but some students become hesitant and unwilling when the interaction takes place in a more demanding situation with the teacher and a larger group of peers. This finding confirms that an individual’s L2 WTC is situation-based and not consistent across different speaking contexts (MacIntyre et al. 1998).

Initially, the results suggest that there is a clear connection between the frequency of EE and students’ L2 WTC, as it seems that the more time a student spends in an EE context, the higher their classroom WTC will be (see Figure 6 in 4.1.3). The results show that the most frequent EE users have the highest overall WTC inside the classroom and that the only group of students that averaged high WTC levels overall were the students that spend ≥ 5 hours daily in an EE context. This result suggests that students’ WTC correlates with their EE engagement, which indicates that a higher frequency of EE usage rewards higher WTC inside the classroom. Even though this connection is seemingly strong in this study, it is,

nevertheless, not absolute. A minority of students showed high levels of WTC without spending much time on EE activities, and others showed low levels of WTC despite being frequent users of EE. This was, in fact, the case with the interviewed Student B who reported low overall WTC inside the classroom (14 points in overall WTC score, see 3.3) despite being

a frequent user of EE. Even though Student B’s result might be an exception rather than the rule, the analysis of the results supports the theory that students’ WTC can be affected by several different factors (MacIntyre et al. 1998; Shirvan et al. 2019). In Student B’s case, their in-class WTC seems to be affected by low L2 self-confidence due to lack of necessary

proficiency and the fear of making mistakes, which according to MacIntyre et al. (1998), is one of the various factors that can affect students’ WTC. This may be a common case in the Swedish context as Fager (2020) came up with the same finding. However, Student B also claimed to have noticed decreased levels of shyness and increased WTC inside the classroom ever since they started using EE deliberately to develop their language. This implies that even though other factors, such as L2 self-confidence, affect some students’ WTC, EE can, indeed, be a useful tool for increasing it (Lee & Drajati, 2019).

Furthermore, the non-frequent EE users reported inconsistency in their WTC in the different contexts. In the more demanding Context 2, communicating with the teacher and other peers, the number of non-frequent EE users that reported an unwillingness to

communicate greatly increased from the first context, communicating with peers only. On the contrary, however, the students who frequently engage with EE showed a higher and more stable WTC between the two contexts, and most of them reported high WTC in both situations. This was also observed in Student A, who claimed to be very confident in their language proficiency and that much of it derived from EE. Student A had no problems

communicating in the classroom. In fact, the student preferred classroom communication over online interaction. Lee and Dressman (2018) found that there is a positive connection between EE and self-perceived language ability, and in their meta-analysis, Shirvan et al. (2019) discovered that a person's self-perception in their L2 proficiency and communicative competence is the most significant influence on L2 WTC. In connection with the previous research, this provides the insight that students’ EE activities affect their in-class WTC by strengthening their self-perceived language proficiency, which helps them to maintain a stable WTC with others through the different classroom contexts.

Not all EE contexts seem to be equally beneficial for increasing student WTC in the classroom, though. Students who frequently engage with productive EE activities, which require the performer to produce oral or written language, showed higher levels of WTC than the students who only engaged with RA. Although the results showed that the combined number of students with mid and high WTC were practically the same in both the RA and PA group, PA produced more than twice the number of students with high WTC than RA.

MacIntyre et al (1998) argue that experience with oral and written language is essential for learners’ communicative competence, which in turn is key for their WTC. This result, thus, builds on the existing evidence that productive EE activities are directly related to the learners’ WTC in the classroom (Lee & Drajati, 2019) and, therefore, also that more

productive activities inside the Swedish EFL classrooms could be beneficial for the students’ WTC as well. However, in the analysis of the effects of different EE activities on WTC, most students included in the PA group also engaged with RA. This could indicate that the

students’ WTC in the PA group could be also be affected by the combined use of all EE activities rather than just PA.

6 Conclusion

The findings in this study suggest that most Swedish upper secondary school students spend a lot of time in the EE context on both RA and PA. A strong connection can be seen between time spent in an EE context and WTC inside the classroom, and productive EE activities seem to be more effective than receptive EE activities in terms of boosting WTC. The results also show that EE usage positively affects students’ language proficiency and self-perception which in turn is beneficial for their WTC in all contexts inside the classroom. Although the connection between EE and WTC has been found to be strong in this study, there are still some students who reported an unwillingness to communicate even though they were frequent EE users. Since WTC has been claimed to be situation-based (MacIntyre et al., 1998), the differences in Student A’s and Student B's WTC could have been affected by different factors such as the teacher, their classmates, or the classroom environment. However, since both interviewees were from the same class and had the same teacher, it seems reasonable to assume that these factors did not have any major effect on the students WTC. Instead, other factors on a more personal level may also be affecting students’ WTC inside the classroom.

Due to the lack of qualitative data on why non-frequent EE users’ WTC is lower than frequent users, the results of the study could only offer a limited understanding of the relationship between EE and WTC. The results of this study are, therefore, to some extent, inconclusive. The generalizability of the results is also limited by the low number of

participants in the qualitative part of the data collection and a larger sample size could have generated more reliable findings. Further and more extensive research on the relation between EE and WTC is needed to expand the understanding of how EE affects students’ WTC. Future research should use observations to compare EE use with actual WTC inside the

classroom, rather than relying on self-reported data. Since most of the students in this study engaged with both RA and PA, another point of potential interest for future research should also be to investigate the effects of receptive and productive EE activities on students’ WTC separately.

List of references

Denscombe, M. (2009). Forskningshandboken – för småskaliga forskningsprojekt inom

samhällsvetenskaperna. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and

mixed methodologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fager, L. (2020). A qualitative study on students’ perceptions of (un)willingness to

communicate in English as a foreign language (Dissertation, Basic level). Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mdh:diva-47021

Hulstijn, J. (2003). Incidental and Intentional Learning. In C, Doughty. (2003). The handbook

of second language acquisition. ProQuest Ebook Central.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/malardalen-ebooks/reader.action?docID=243543#

Lee, J. S. (2019). EFL students' views of willingness to communicate in the extramural digital context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(7), 692-712.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1535509

Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2019). Affective variables and informal digital learning of English: Keys to willingness to communicate in a second language. Australasian

Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 168-182.

https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5177

Lee, J. S., & Dressman, M. (2018). When IDLE hands make an English workshop: Informal digital learning of English and language proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 52(2), 435-445. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.422

MacIntyre, P. D., Babin, P. A., & Clément, R. (1999). Willingness to communicate: Antecedents & consequences. Communication Quarterly, 47(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379909370135

MacIntyre, P. D., Dörnyei, Z., Clément, R., & Noels, K. (1998). Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation. The

Peng, J.‐E., & Woodrow, L. (2010), Willingness to Communicate in English: A Model in the Chinese EFL Classroom Context. Language Learning, 60(4), 834-876.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x

Richards, J. C. (2015). The changing face of language learning: Learning beyond the

classroom. RELC Journal, 46(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688214561621

Reinders, H., & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50(4), 561-578.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000192

Reinders, H., & Wattana, S. (2014). Can I Say Something? The Effects of Digital Gameplay on Willingness to Communicate. Language Learning & Technology, 18(2), 101–123. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44372

Rama, P. S., Black, R. W., Van Es, E., & Warschauer, M. (2012). Affordances for Second Language Learning in "World of Warcraft". ReCALL, 24(3), 322-338. https://doi-org.ep.bib.mdh.se/10.1017/S0958344012000171

Shirvan, M. E., Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., & Tahereh, T. (2019). A Meta-analysis of L2 Willingness to Communicate and Its Three High-Evidence Correlates. J

Psycholinguist Res 48, 1241–1267. https://doi-org.ep.bib.mdh.se/10.1007/s10936-019-09656-9

Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education]. (2011a). Kommentarmaterial till

ämnesplanen i engelska i gymnasieskolan. Accessed 14 October 2020 at

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6011fe501629fd150a28916/1536831518394 /Kommentarmaterial_gymnasieskolan_engelska.pdf

Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education]. (2011b). English. Accessed 3 December 2020 at

http://www.skolverket.se/polopoly_fs/1.174543!/Menu/article/attachment/English%2 0120912.Pdf

Sundqvist, P. (2009) Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on

Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary. PhD, Karlstad University,

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2014). Language-related computer use: Focus on young L2 English learners in Sweden. ReCALL, 26(1), 3-20.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401300023

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From

theory and research to practice. London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System, 51, 65–76.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.04.001

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302–321.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401200016X

Vetenskapsrådet. (2017) God forskningssed. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Child

Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 17(2), 89–100.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. The Modern Language Journal, 86(1), 54-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00136

Appendices

Appendix 1– The questionnaire

Engelska på fritiden och viljan a kommunicera på engelska i

klassrummet

Information om undersökningen

Alla svar i undersökningen kommer att anonymiseras. Ditt namn kommer endast att ses av mig som undersökare och kommer inte att finnas med eller användas i min rapport. Jag önskar att du läser frågorna noga och svarar på samtliga frågor så ärligt som möjligt. Be gärna om hjälp om du upplever att du har svårt att förstå en fråga. Om du inte vill svara på en fråga så går det bra att hoppa över den. Om du har några frågor om undersökningen kan du kontakta mig via min mejl: XXXXXXXXXXXXX. Tack för ditt medverkande.

1. Namn (ditt namn kommer anonymiseras och inte finnas med eller synas någonstans)

2. E-postadress (vänligen ange din e-postadress så jag kan kontakta dig för en eventuell

uppföljningsintervju)

Del 1. Engelska på fritiden

I denna del kommer du få frågor om din engelska aktivitet på fritiden.

3. Jag använder ENGELSKA på fritiden utanför skolan till följande aktiviteter (Kryssa i alla som passar)

Markera alla som gäller.

Lyssna på musik/podcast på engelska

Titta på film/TV-serier eller YouTube på engelska

Läsa på engelska (böcker, bloggar, tidningar, eller andra texter) Prata på engelska med vänner/familj

Prata på engelska när jag spelar TV/datorspel, läser högt, röst-/videochattar med andra, eller gör annat på fritiden

Spela TV/datorspel där jag använder engelska på något sätt skriva på engelska (bok, blogg, chatt)

Följer engelsktalande personer på sociala medier

4. Jag lyssnar på engelsk musik/podcasts

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

5. Jag tittar på film/TV-serier eller YouTube på engelska

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

6. Jag läser på engelska (böcker, bloggar, tidningar, eller andra texter)

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

7. Jag pratar engelska med vänner/familj

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

8. Jag pratar på engelska när jag spelar TV/datorspel, läser högt, röst-/videochattar med andra, eller gör annat på fritiden

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

9. Jag spelar TV/datorspel där jag använder engelska på något sätt

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

10. Jag skriver på engelska (bok, blogg, chatt)

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

11. Jag följer engelsktalande personer på sociala medier och kollar på deras innehåll

Markera endast en oval. Aldrig

Några gånger i månaden Några gånger i veckan Varje dag

12. Ungefär hur mycket tid av min fritid spenderar jag på aktiviteter som inkluderar engelska (se exemplen ovan + andra aktiviteter)

Markera endast en oval.

0 timmar/vecka 1-5 timmar/vecka 0-1 timme/dag 2-3 timmar/dag 4-5 timmar/dag mer än 5 timmar/dag

Del 2. Viljan att kommunicera på engelska

Dessa frågor handlar om din vilja att använda det engelska språket för att kommunicera med andra i klassrummet.

Läs igenom följande frågor och ange på skalan hur villig du skulle vara att kommunicera på engelska i de angivna situationerna.

1. Inte alls villig. 2. Förmodligen inte villig. 3. Kanske villig. 4. Förmodligen villig. 5. Definitivt villig

13. Jag är villig att använda engelska för att svara på frågor muntligt i klassrummet

Markera endast en oval.

1 2 3 4 5

14. Jag är villig att prata på engelska när jag ska hålla en presentation/ ett tal framför

klassen

Markera endast en oval.

15. Jag är villig att prata på engelska i mindre grupper i klassrummet

Markera endast en oval.

1 2 3 4 5

16. Jag är villig att prata på engelska i klassrummet när jag får göra det fritt med vem jag

vill

Markera endast en oval.

1 2 3 4 5

17. Jag är villig att prata engelska med min lärare när jag behöver be om hjälp

Markera endast en oval.

1 2 3 4 5

18. Jag är villig att skriva en text på engelska som mina klasskompisar ska läsa

Markera endast en oval.

1 2 3 4 5

19. Jag är villig att skriva på engelska på tavlan

Markera endast en oval.

Appendix 2 - Interview questions

1. What type of extramural English activities do you engage with?

a. Can you describe how you engage with those? How do you use English in the activities?

b. What do you read/play/watch/listen to?

c. You claimed that you (claimed activity in the questionnaire) every day. How much time do you spend on an average day on that specific activity?

2. Can you tell me how you feel about communicating in English outside of the classroom?

a. Do you feel comfortable, nervous, and/or confident?

b. Is there any difference in how you feel about communicating in English in your spare time, as opposed to inside the classroom?

c. Do you believe you are more willing to communicate in English when you do it outside of the classroom, as opposed to in class?

3. Does using English outside of the classroom benefit you inside it in any way? Why/why not?