Cooking and Eating

An Exploration of Auditory Cues of Food

Preparation During Commensality

Kevin Ong

Interaction Design One-Year Master 15 Credits

Spring 2017

ABSTRACT

This thesis project covers a ten week exploration in Human Food Interaction. Employing a Research through Interaction Design methodology with a focus on Celebratory Technologies, this paper focuses on the research question, “How can celebratory technologies enhance social engagement between diners in commensality and raise awareness of the otherwise hidden process of cooking using auditory cues of food preparation?” A physical computing prototype using a Makey Makey Board with Processing is integrated into three user test sessions during dinner time to assess the effects of auditory cues of food preparation on the diners. The prototype is then evaluated using the qualities of Celebratory Technologies in addition to considerations of technological limitations and potential for future growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to recognize Anders Emilsson for his supervision and guidance with this thesis project from its conception to delivery. In addition, I wish to extend my gratitude to my cohorts in the Interaction Design Master’s Program for their unrelenting assistance, feedback, and participation. I wish to especially thank the nine test session participants for the hours they set aside to bring this project to fruition. I also wish to thank the Interaction Design Program’s faculty for the copious amounts of knowledge they imparted with me this past year. Lastly, I extend my appreciation to Kelly Ong and Raya Dimitrova for taking the time to proofread and review this paper.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 THEORY

2.1 Celebratory Technologies 2.2 Laying the Table for HCI

2.3 Canonical Examples & State of the Art

2.3.1 EaTheremin

2.3.2 Sounds of the Sea 2.3.3 Living Cookbook 2.3.4 Sounds of Umami

2.3.5 Massimo Bottura’s The Sounds of Cooking

3.0 METHOD

3.1 Desk Research 3.2 Fieldwork

3.3 Research by Interaction Design 3.4 Prototyping 3.5 Physical Computing 3.5.1 Makey Makey 3.5.2 Processing 3.6 Project Plan 4.0 DESIGN PROCESS 4.1 Preliminary Observations 4.2 Reframing

4.3 Conceptualization and Synthesis 4.4 Execution

4.5 Ethical Considerations

5.0 MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN

5.1 Session A 5.2 Session B 5.3 Session C

6.0 EVALUATION AND DISCUSSION

6.1 Attributes of Celebratory Technologies

6.1.1 Gifting

6.1.2 Pleasure and Nostalgia 6.1.3 Family Connectedness 6.1.4 Relaxation

6.2 The Ecologies of Domestic Food Consumption 6.3 Future Considerations

7.0 CONCLUSION REFERENCES

APPENDIX A: Project Timeline

APPENDIX B: Session A Processing Sketch APPENDIX C: Session B Processing Sketch APPENDIX D: Session C Processing Sketch

4 7 7 8 9 9 10 10 11 11 12 12 12 12 13 14 14 14 15 16 16 16 17 18 19 21 21 23 26 29 29 29 29 29 31 31 32 34 36 38 39 40 41

INTRODUCTION

Food is a necessity for survival. However, it does not provide just physical sustenance, but social well-being as well. Food has the ability to bring people from all walks of life together in its production and consumption. This practice of “sharing food and eating together in a social group”(Ochs & Shohet, 2006, p. 37) is called ‘commensality’ and it dates back to the prehistoric era of hunters and gatherers. Family mealtimes in particular are a ritual that “connotes togetherness, cohesiveness, [and] unity… that is central in binding family relationships”

(Chitakunye & Maclaran, 2014). As a society, we enjoy food, the practice of food preparation, the act of consuming food, and sharing food while we socialize with one another (Grimes & Harper, 2008). Socializing and eating can be considered a form of entertainment. Food can symbolize emotional attachments, positive feelings, provide comfort, and serve as a stress- relieving activity (Wei & Nakatsu, 2012). An excerpt from Genevieve Bell and Joseph Kaye’s Kitchen Manifesto puts it best, “Recipes are family secrets, national identities, corporate mysteries, poetry. Foods are memories of lovers, vacations, childhoods, family dinners gone wrong, family dinners gone right, first dates, last dates, and shared memories. Cooking is a chore, an act of love, a ritual, a lesson (2002, pg. 58).” Food is such a central part to our daily lives that it only seems natural that it has come to intertwine with our rapidly developing technology culture.

Food preparation and sharing provide opportunities to support the creative, sensory, aesthetic and social nature of Human Food Interactions (HFI) (Comber, Choi, Hoonhout & O’hara, 2004), a subset of Human Computer Interactions (HCI). Food related behaviors, such as sharing, cooking, eating, and so on can all be considered beneficial to social and personal well being. Digital technologies are increasingly influencing our mealtime experiences in attempts to enhance the flavor of our meals, provide entertainment, create memorable experiences, or aid us in making healthy dietary decisions (Spence & Piqueras-Fiszman, 2013).

On the other side of the coin, digital technologies afford distraction to commensality. As technology advances we have had media encroach and embed themselves into our mealtime rituals such as the newspaper, radio, television, and now smartphones (Chitakunye & Takhar, 2014). Studies have shown that watching television while eating has become a social norm. It is more or less accepted based on the context of the meal. Television shows even provide topics of conversation for the family to discuss. Another aspect of television use during mealtime is that it is only distracting to the family conversation if a person is actually engaged and focused with the broadcasted material (Ferdous, Ploderar, Davis, Vetere, & O’hara, 2016). It has become common for the television to be left on and provide background noise. This allows the opportunity to literally “tune in” and “tune out” of participating with the family (Barkhuus & Brown, 2009).

Smartphones however are small, portable, and its contents are directed and personally

customized to the owner of the device. In studies regarding mobile phone usage at the family dinner table both positive and negative outcomes have been discovered. The leading negative voice is that of the parent who wants to engage with their children and believe that mealtime is family time. However, in that generation gap, children claim that they use their phones to share with their family things they find interesting or even share with the family the

conversations they are having with their friends in order to build up a discussion (Chitakunye & Takhar, 2014). More often than not, mobile devices are being used to access social media or communicate with friends via SMS. These are great applications for keeping up with friends, but what happens when you are already around friends physically (Roberts & David, 2016) (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, 2016)? It is in this situation that phubbing, defined as, “the act of snubbing someone in a social setting by looking at your phone instead of paying attention” occurs (Haigh, 2015). Phubbing is a phenomenon that no one enjoys yet sometimes

unknowingly participate in. So how can we tackle this issue of engagement in a social dining setting in an era that allows for so many distractions through technology?

This is where Andrea Grimes and Richard Harper’s Celebratory Technologies (2008) comes into play. Celebratory Technolgies refers to projects that seek to augment positive behaviors in social situations. This is in contrast to Corrective Technologies that seek to solve or alter unwanted behaviors. It is important to note that Celebratory Technologies exists purely in the subset of HFI as the pair’s goal was to “explore a different path for food research in HCI, one that focuses not on the problems that individuals have with food, but rather one the ways in which people find pleasure and success in their interactions with food (pg. 467).” The reasons to pursue Celebratory rather than Corrective Technologies in human-food interactions are twofold:

1. If there is no desire to change the current state of affairs then there is no need to introduce corrective technology to attempt to fix the current behavior

2. It is necessary to understand what is lost from the existing food landscape when corrective technologies are employed

Instead of seeking a solution in the domain of Corrective Technology to engage the diners and end phubbing, (meanwhile possibly punishing the users from using their own belonging) this project seeks to increase social engagement among peer groups with Celebratory Technologies focusing on the positive atmosphere and behaviors of sharing and socializing with loved ones in order to augment the dining experience. Nonetheless, it is very important to “consider whether it is necessarily always a good thing (to bring technology to the dining table) [and] it is important to remember that it can also provide an unwanted form of distraction (Spence & Piqueras-Fiszman, 2013, pg. 6).”

As mentioned earlier, the field of HFI is broad and the one this thesis will focus on is the dining experience when paired with audio cues from food preparation. Charles Spence states that, “no one has assessed whether auditory preparation cues are sufficiently powerful to override other (e.g. visual or olfactory cues associated with the preparation of a food or beverage item) (2012).” Spence argues that sound is an attribute of flavor that is often forgotten. When questioned, researchers soundly agree that sound ranks lowest as a contributing factor to flavor (Delwiche, 2003), however there are several that have expressed that sound greatly contributes to the consumers food and drink experience (Spence 2012). Consumers have come to expect certain auditory qualities from their food and beverage such as the pop of a can of Pringles, the iconic sound of a bottle of Snapple being opened, or the fizz of a carbonated drink (Spence & Wang, 2015). Background music has also proven to be influential in our food behaviors (Spence 2012). There is an expected relationship between different types of music with different types of dining establishments such as rock music at a sports bar or classical music at a fine dining restaurant. Musicality isn’t limited to the dining experience, but also expands to a consumer’s shopping habits in grocery stores such as time spent shopping and product selection (North, Hargreaves, & McKendrick, 1997). Next, there have been studies that map flavors, textures, and aromas of foods to sonic qualities such as tone, pitch, and timbre (Holt-Hansen, 1968) (Crisinel et al., 2012). Last, but not least, the sound of food preparation can positively enhance the consumption of food and drink such as the sound of grinding coffee beans and the squeal of steam under high pressure. In a study it was suggested that loud and sharp mechanical sounds should be reduced and ambient sounds such as sizzling or dripping could be increased to enhance the consumption experience (Knöferle, 2012).

Described in this paper is a process that identifies an opening in phubbing, but following survey results and observation, finds that there isn’t a desire to upend and alter the current situation. Thus, it becomes unnecessary to forcibly persuade the users to adopt a corrective technology that may end up hindering parts of the current situation. With celebratory technologies, rather than impairing technological stimulation, this project seeks to enhance auditory stimulation with sound bites of food preparation and insert it into the dining environment in order to augment the mealtime experience. While, this thesis does not seek to explore sound’s ability to override the visual or olfactory attributes of food, it certainly wants to explore how auditory food preparation cues affect the dining party’s mealtime experience. Will it trigger an emotional response? Will they feel more connected to the chef preparing the meal? Will the sound bites allow for playfulness and discourse among the diners? Will the auditory cues simply be distracting? Henceforth, our research problem is as follows, “How can celebratory technologies enhance social engagement between diners in commensality and raise awareness of the otherwise hidden process of cooking using auditory cues of food preparation?”

2.0 THEORY

2.1 Celebratory Technologies

Grimes and Harper (2008) define ‘Celebratory Technologies,’ as “technology that celebrates the positive and successful aspects of human behavior (p. 468).” Celebratory technologies came about from the pair studying existing projects on food within the realms of HCI, also known as Human Food Interaction (HFI). They noticed that the majority of projects focused on problems that individuals had with food such as (p. 467):

1. Uncertainty 2. Distractions 3. Inexperience 4. Inefficiency

5. Lack of Nutritional Knowledge

Grimes and Harper defined these projects as ‘Corrective Technologies.’ Corrective Technologies came about from the desire to fix undesirable behaviors that people have with food. As listed above, Uncertainty, is one of the factors that lead to creating Corrective Technologies, such as creating a smart cookbook in order to help decide what to make for a meal. One of the largest contributors is Distractions. In this digital era we live in, distractions come in many forms such as radio, television, smartphones, tablets, and gaming devices. This has resulted in a number of studies focusing on the effects of television at the dinner table. When it comes to cooking and food consumption, worries of Inexperience, Inefficiency, and a Lack of Nutritional Knowledge come hand in hand. As a result, we’ve seen an uptick in smart kitchen devices in the past decade or so that have the intent of telling us what exactly is in our refrigerator, what is in the beverages we consume, and numerous diet tracking smartphone applications. These are all great systems and products that can help benefit the lives of their consumers. However, Grimes and Harper go on to explain, “We certainly agree that individuals do encounter problems in their interactions with food, but it is also true that at times, indeed if not most of the time, they enjoy their food, relish the practice of making it, and above all celebrate the sharing of it. (p. 467)”

On the other side of the coin however, Celebratory Technologies opens the path to do just that, exploring the way food brings people together in its preparation and consumption. Celebratory Technologies’ goals are not to alter current food related interactions, behaviors, or practices, but rather explore new ways of engagement through Human Food Interaction practices through six attributes (p. 471):

1. Creativity

2. Pleasure and Nostalgia 3. Gifting

4. Family Connectedness 5. Trend-seeking Behaviors 6. Relaxation

Attribute such as Creativity, Gifting, and Trend-seeking Behaviors fall more heavily on the side of the cook preparing food. Research that highlights these attributes allow cooks in the kitchen to explore and learn more about cooking and then in turn share that with their loved ones. In a way it directly contrasts the Corrective Technology attributes of Uncertainty, Inexperience, and Inefficiency in addition to addressing one of the reasons for pursuing Celebratory

Technologies that was listed in the Introduction: “It is necessary to understand what is lost from the existing food landscape when corrective technologies are employed.” Gifting in turn lends itself to enhancing Pleasure and Nostalgia, Family Connectedness, and Relaxation. There are immense emotional benefits to cooking and eating with a close social circle. For example, making comfort foods for loved ones makes them feel cared for and when a person's emotional needs are met it is easier for them to relax and open up thus, creating a comfortable space for communication and story sharing. In order to advance in designing for Celebratory Technologies we must assume that the relations between people and their food do not need an intervention for amelioration, but rather seek understanding in order to celebrate the positive aspects of how we as humans interact with food.

2.2 Laying the Table for HCI

Annika Hupfeld and Tom Rodden’s (2012) “study of people’s dining practices with practical emphasis on the tabletop interactions, the spaces where dining occurs, and the artefacts and activities involved. (pg. 119),” provides best practices in setting up a workshop environment for dining. Their study analyzed the configurations of informal and formal dining. Hupfeld and Rodden’s paper state that having friends over makes it more likely for the host to prepare a proper meal and in that sense the dining situation becomes more formal. In addition, “formality is not a hard and fast rule, but rather something that is defined and redefined by the household (pg. 122).” Their study also compared continuous and upfront serving. “Continuous serving of food involved all food being brought to the the table, where eaters could then typically serve themselves” and “serving upfront, on the other hand, involved placing food directly onto plates in the kitchen before bringing it to the table (pg. 123).” The pair state that continuous serving was typically done when the meal involved guests or visitors as it contributes to a social atmosphere and allows the diners to select the items they wish to consume themselves. Last, but not least, of the findings from Hupfeld and Rodden is meal structure. Structured meals have a clear beginning and end, the table would be set, and it would be required for all members of the dining party to be present before starting. Unstructured meals have no set beginning and end and benefits efficiency for individual schedules. However, “commensality and experiencing the meal as a family or group is what makes structure important to a meal (pg. 124).” In their retrospective, Hupfeld and Rodden leave words of wisdom for future interaction designers diving into HFI (p. 126-127):

2.3 Canonical Examples & State of the Art

2.3.1 EaTheremin

“1. Interaction designers may want to think about the degree to which their designs foreground and background the nature of occasion.

2. Interaction designers might wish to think about how their designs draw up on the boundaries between independence and socialization and the gestures that signal them. 3. Interaction designers seeking to augment dining may want to think about the affordances of their designs to promote either sharing within the context or isolation and removal from it.

4. Interaction designers may want to extend their design consideration beyond the immediate context to which their design will be deployed and consider the potential trajectories a dining artefact might take over its lifetime of use.”

EaTheremin (Kadomura, 2011) is a fork-like dining artifact that plays various sounds as the diner eats, creating a source of entertainment. The sounds are created based on human contact with the food on the end of the fork. However, different foods offer different resistance values based on type, length, and thickness, which allows for a playful interaction between the diner and their food. More so, the prototype only activates when the food touches the user’s mouth allowing for control over duration, speed, and rhythm. Although, EaTheremin does not directly address ways that sound can enhance one’s perception of food, it does address social behaviors and awareness in a dining situation. With multiple EaTheremin devices participants at the dining table are able to play and explore the quality of their meal with one another. The project is a prime example of a Celebratory Technology in that it only seeks to enhance currently existing social behaviors rather than correcting any interactions between the users.

Heston Blumenthal, the head chef of three-star Michelin restaurant, The Fat Duck states that, “Sound is one of the ingredients that the chef has at his/her disposal (Spence &

Piqueras-Fiszman, 2013, pg. 2).” Sound has the ability to enhance the taste and flavor of a dish by getting the diner to focus their attention on the meal in front of them. In Blumenthal’s dish ‘The Sound of the Sea,’ the waiter instructs the diner to adorn a pair of earphones with the sounds of the sea prior to consuming the seafood dish. The multisensory experience of eating is amplified and focused now that the diner is not listening to idle background chatter, but the sounds of crashing waves and seagulls overhead. This experience enhances the flavor of the dish by altering perception and transporting the diner to a different point of time and space. In consuming a dish we obviously use taste, sight, smell, and touch, but by adding sound, Sounds of The Sea is able to bring the multisensory experience to another level.

Living Cookbook (Terrenghi, Hilliges & Butz , 2007) is a kitchen appliance that allows users to record, annotate, and playback cooking sessions. This concept explores the kitchen as a design space and cooking as a social activity. More so, it creates a record of the cooking process for the consumer allowing for social and cultural growth between not only cook and diner, but for prosperity as well. Living Cookbook is a project that excels in highlighting the attributes of Celebratory Technologies. Its affordance as an artifact for prosperity displays its properties of Gifting, Family Connectedness, Relaxation and Pleasure & Nostalgia. In addition, its playback features allow for viewers to explore how the cooks in the kitchen were able to display Creativity and Trend-seeking Behaviors over time through generations in a family.

2.3.3 Living Cookbook

2.3.2 Sounds of The Sea

Figure 5: Living Cookbook in the kitchen Figure 3: Heston Blumenthal plating Sounds of The Sea

Figure 6: Living Cookbook’s interface

From March 16 to May 17, 2017, Swedish fast food chain, MAX, began a campaign titled, Sounds of Umami (Max Hamburgers AB, 2017) in collaboration with Stockholm based sound design agency Plan 8. In this commercial application of flavor enhancement via auditory cues, they produced a curated playlist pairing certain flavors to distinct sounds such as: “deep frequencies and subtle, crisp high frequencies to enhance the saltiness and smokiness of bacon” and “high frequencies and faster rhythms to enhance the red onion’s sweet and sour flavors and sharp spiciness.” This is a clear example of HFI research that began with Kristian Holt-Hansen’s exploration in taste and pitch in 1968 and more recently Anne-Sylvie Crisenel et al.’s cross- modal exploration of modulating taste by changing the sonic properties of background music while people were eating.

This is a video (Ancarani, 2016) of Massimo Bottura, head chef of three-star Michelin restaurant Osteria Francescana, and his two assistants cooking his take on lasagna in a sound-proof room with numerous microphones. The trio works in silence as they prepare the dish with the microphones recording every drop, whisk, and chop. The sounds are harmoniously layered together and dynamically engaging. The video concludes with Massimo eating the dish and asking the viewer, “And how does that make you feel?” The execution and production value is beyond my current abilities, but its aesthetic qualities are what I intend to employ in this thesis project. It also resonates very well with Charles Spence’s research describing the ability of the sounds of cooking to enhance the quality of the food or drink to be consumed.

2.3.5 Massimo Bottura’s The Sounds of Cooking

2.3.4 Sounds of Umami

Figure 7: The Sounds of Umami playlist on Spotify

Figure 9: The soundproof room and microphone setup

Figure 8: A diner listening to the playlist while eating

3.0 METHODS

3.1 Desk Research

3.2 Fieldwork

3.3 Research by Interaction Design

In order to familiarize myself with current explorations into the field of HFI, an extensive literature review must occur. Initial readings will be broad with diverse as I grasp a grounding of what currently exists and what openings are available to explore. As the thesis project progresses, the literature review will become more focused and specified based on the research question. In addition to scholarly research, it is important to take a step back and look in from the everyman’s point of view. I will also look into public studies, news articles, and use cases of how food and technology effect social interaction during commensality. The field of HFI is much broader than the insights of interaction designers and researchers so its necessary to consider the perspectives of chefs and diners as well.

In addition to the literature review, I will compose and distribute surveys. These surveys will help shape and form to path move forward with during this thesis project. The first survey is primarily open-ended as people’s relation with food and technology is much too vast, emotional, and subjective to contain in a quick multiple choice form. The second survey is much more refined but still takes on a free response format to shape understanding of current behavior trends. These surveys and their results can be found in Appendix E.

Along with surveys, fly-on-the-wall observations will be employed. I will be observing the actions and behaviors of diners in different dining establishments at different times of day. This is gain a more holistic understanding beyond the survey group as the survey’s narrowness could lead to skewed and nuanced replies that are not representative of the average user.

Jonas Löwgren introduces in Interaction design, research practices and design research on the

design materials (2007), his view towards interaction design, the nature of research in the field,

and the possible forms and contributions that research in interaction design can take on. Löwgren details five strategies (listed below) to approach scientific contributions to HCI mean-while making design an integral party of the knowledge contribution process. Of the five, this thesis project will focus primarily on the first.

1. Designing prototypes for empirical evaluation with the intention to study the qualities of the new design ideas in use.

2. Exploring the potentials of a certain design material, design ideal or technology. 3. Exploring possible futures which are rather far from current situations.

4. Designing artifacts for instantiating a more general theory in a specific design material and assessing the results.

5. Performing a participatory design process where the future users act as experts in their field of practice.

3.4 Prototyping

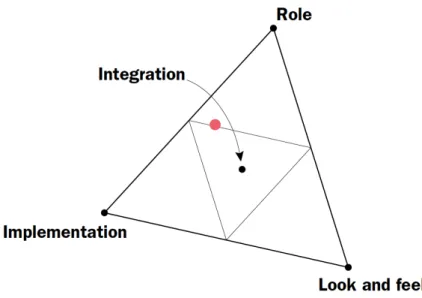

This thesis project will use Stephanie Houde and Charles Hill’s definition of prototype, “any representation of a design idea, regardless of medium (Houde & Hill, 1997, pg. 3).” Houde and Hill define four dimensions that a prototype can take on:

1. Role: the function of the prototype in the user’s life

2. Look-and-Feel: the sensory experience of using the prototype

3. Implementation: the components and techniques that makes the prototype work 4. Integration: a prototype that explores all three of the aforementioned equally Houde and Hill’s diagram of the three attributes has them equally weighted in an equilateral triangle with Integration in the center, however it is up to the designer, myself, to decide where the prototype falls in relationship to them. By prioritizing certain attributes over others, the designer is better equipped to create a prototype that is more informative and beneficial in tackling a specific research question.

This thesis project will focus on a prototype that prioritizes Role and Implementation, Look-and-Feel will be a secondary factor. The protoypes will be tested in three user testing workshop sessions. Feedback from one session will allow for iteration and improvement of the workshop succeeding it. These sessions will be documented with photography, videography, and audio recording for evaluation.

3.5 Physical Computing

Makey Makey is a piece of open source hardware based off of an Arduino board created by Jay Silver and Eric Rosenbaum in 2012. The Makey Makey doubles as a tool for physical computing and a learning toy for children. The circuit board allows users to connect everyday objects with alligator clips to create closed loop electrical signals to send to a computer program via USB either a keyboard stroke or mouse click signal.

Dan O'Sullivan and Tom Igoe state Physical Computing is about, “creating a conversation between the physical world and the virtual world of the computer (2004, pg. xix).” In physical computing, we explore the interactions between human physical energy and mechanic electronic energy bridging the physical and virtual world. Sensors are used to understand embodied human input such as motion, touch, light, heat, sound and so on. This input is sent to a simple

computer, called a microcontroller, which outputs data or whatever a program tells it to do. In this thesis project, the microcontroller I will be using is a Makey Makey board which uses capacitive touch via alligator clips to send input data to the computer. I will be using Processing to create a simple program to process the input data form the Makey Makey into audio output.

Processing is an open source computer programming software created by Casey Reas and Benjamin Fry in 2001. Processing uses a simplified form of Javascript with a graphic user interface. Processing is ideal for teaching and implementing computer programming into electronic and interactive art. It’s simplified language, visual form, and ease of use also allows it to act as a digital sketchbook.

3.5.1 Makey Makey

3.5.2 Processing

3.6 Project Plan

The project plan for this thesis primarily follows the suggested timeline for this course. Here, I will briefly explain the suggested timeline and approach for this thesis project. The full timeline can be found in Appendix A, which details the key dates of events and engagements.

Phase 1 (weeks 1-2): Project Formation

During the first phase, the goal is to establish a topic and research focus for the thesis project. I intended to focus on food, technology, and our relation to it as humans. Following a week of desk research, a couple of project proposals will be submitted along with suggestions from my assigned supervisor. At the end of this phase, the project proposal will undergo review to deem if it is within the scope of Interaction Design.

Phase 2 (week 3): Exploration

The second phase is primarily dedicated to broadening one’s knowledge about the topic of intent. I will take this time to do more desk research and consume more literature surrounding food and technology. Additionally, I will create surveys to gain a foothold on current preconceptions surrounding how people interact with food and technology in their peer groups. During this time I will consider my technological approach to creating a feasible and appropriate prototype for testing.

Phase 3 (weeks 4-5): Conceptual Discovery

In the third phase, I should begin concepting ideas to pursue, meanwhile continuing field research and observations. This is largely a divergent phase of exploration, however I may need to being synthesis before Phase 4 due to the time constraints of this project. At the end of this phase, First Drafts are submitted for peer review.

Phase 4 (weeks 6-7): Synthesis and Detailed Design

At this point, I should have a clear path forward for prototyping and have an understanding of the technological methods I wish to proceed with. The majority of my time in this phase will be spent preparing and executing user testing workshops. Each workshop should provide feedback that allowes me to iterate and improve for the next session.

Phase 5 (weeks 8-9): Thesis Completion and Production of Exam Demo

These final weeks are to be spent compiling and analyzing the data from the user testing workshops and writing up the results and evaluation of those sessions. At the end of this phase is the submission of the thesis paper.

Phase 6 (week 10): Examination

Lastly, is the culmination and examination of ten weeks of work by an assigned examiner in addition to a public audience.

4.1 Preliminary Observations

A 25 question survey inquiring phone usage and behavioral patterns during commensality was distributed. I focused primarily on questions about peer groups, but was also curious about the surveyor’s thoughts and opinions about phubbing within different situational contexts. After a couple of days I had received 18 replies to synthesize and analyze. The majority of the answers leaned in the same direction with few outliers. In a short summary, my survey pool for the most part did not know of the term “phubbing,” but recognized the definition and stated that they have indeed been a victim of “phubbing” and at the same time most likely a phubber themselves. However, the survey pool felt that rules and regulations towards smartphone behavior was unnecessary and that society should have common sense and decent manners when engaging in conversation with friends. If a friend was excessively and rudely phubbing, the surveyed individual would simply ask them to stop and pay attention.

Following the revelations from the survey results, I employed a fly-on-the-wall approach to observe users while they ate. My observations took place during lunch and dinner times at fast food restaurants, cafes, and fine dining establishments over a period of two days. I had found that my assumptions and skewed perspective of the negative impact of phubbing from the survey results had been subverted by observing actual diners. Observations showed that phubbing hardly if ever actually occurs during mealtime. When people are eating, their hands and mouths are thoroughly occupied with the plate of food before them and utensils in hand. Phubbing, should it occur, occurred before or after the dining period. Although the insight into the field was fascinating it was not the situational context I wished to explore during this thesis project. Consequently, reframing was in need and a reevaluation of the direction of the thesis project.

4.0 DESIGN PROCESS

4.2 Reframing

The situation I was interested in exploring was the act of commensality. The entire social atmosphere of eating and talking among loved ones is something I am drawn to and pursuing phubbing was not one I wanted to pursue at this particular moment in time despite the numerous readings and grounding I had found for the topic. In order to reframe and refocus I looked to the past with Sit, Eat, Drink, Talk, Laugh: Dining and Mixed Media (2009), a thesis paper by Edda Kristin Sigurjonsdottir, an alumnus of Malmö University, whose paper hit on the themes and qualities that drew me to pursuing food and interaction design. From here, I was introduced to Grimes and Harper’s Celebratory Technologies which shifted my perspective on how we interact with food and technology. Rather than pursuing corrective technologies to prevent smartphone usage, celebratory technologies offered positive methods of engagement during commensality.

In the following days, I sent out a second survey that focused more on cooking and eating behaviors. During this time I took time to do another literature review primarily on introducing technology to the dinner table. In doing this I became acquainted and fascinated by the sensory and psychological studies of sound enhanced meals (particularly Charles Spence's work) as described in the State of the Art section of this paper.

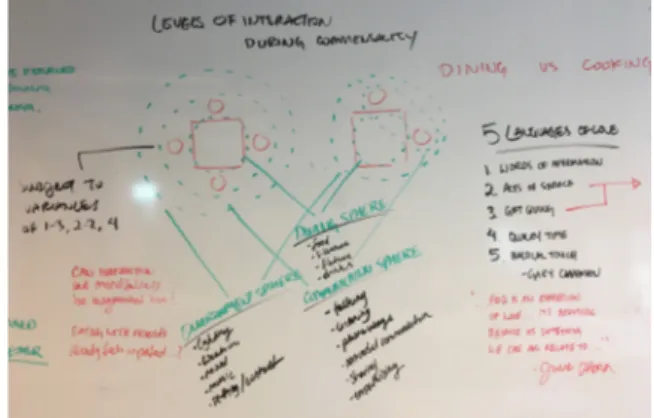

4.3 Conceptualization and Synthesis

Over a couple of days I conceptualized designs that I could demonstrate during a meal

meanwhile keeping in mind the restraints of my time, skills, and materials. I intended to create a prototype to fulfill the parts of Role and Implementation from Houde and Hill’s What

do Prototypes Prototype? (1997). The qualities of Look-and-Feel will be secondary, but primarily

focused on the sensory exploration of the prototype and the experience of using it rather than its visual aesthetics. Naturally, to demonstrate a prototype during a meal, I knew I would be required to prepare meals and have participants willing to take part in a dinner integrated with a digital component. I determined that in order to demonstrate what I have learned over the past year that physical computing with implementation from Processing and Makey Makey would be well within my scope of abilities.

4.4 Execution

Of the five methods detailed in Research by Interaction Design, the one I am employing in this thesis project is: “Designing prototypes for empirical evaluation with the intention to study the qualities of the new design ideas in use (Löwgren, 2007, pg. 6).” This is ideal for demonstrating technical feasibility and semi-abstract knowledge contributions. Three user-testing workshops were planned with each one accommodating three users for the period of a dinner time meal. In the first set of surveys, one of the questions presented was, “What is your favorite dish?” and if possible, to include a link to a video or recipe for said dish.

The format of the prototype sessions were informed by Hupfeld and Rodden’s research as mentioned in the Theory section of this paper. The key points followed in order to create a social and engaging experience were:

1. An unformal dining experience without any strict rules or regulations 2. Continuous serving where the diners serve themselves

3. A structured meal that had a clear beginning time will all participants present

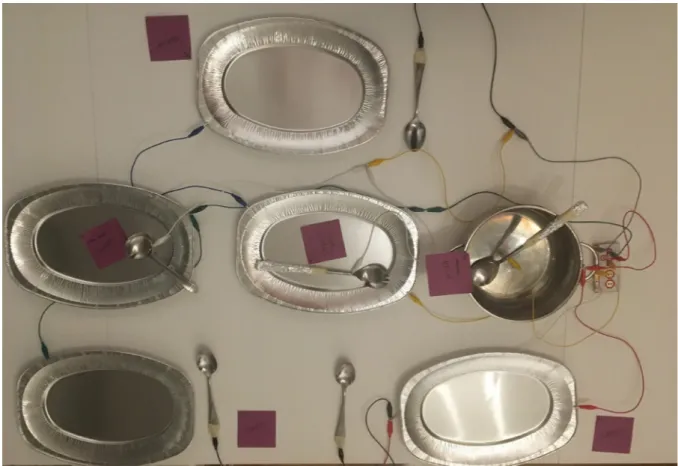

Hours prior to the workshop, three dishes were prepared according to the answers from the three participants (further referred to as “the diners”) attending the workshop. In this prototype, the food preparation was done by me (referred to as “the chef”). Audio recording took place while the chef prepared each meal. This audio recording was arranged and curated to different degrees across the three sessions to bring forward key auditory cues from the cooking process of each meal. These sound bites were then mapped to a keyboard inputs on a Makey Makey board. From the Makey Makey board, alligator clips mapped to the keyboard functions of the board were attached to either communal serving dishes or personal plates. Then, another set of alligator clips were attached to the ground component of the Makey Makey board which were attached to each person’s eating utensils.

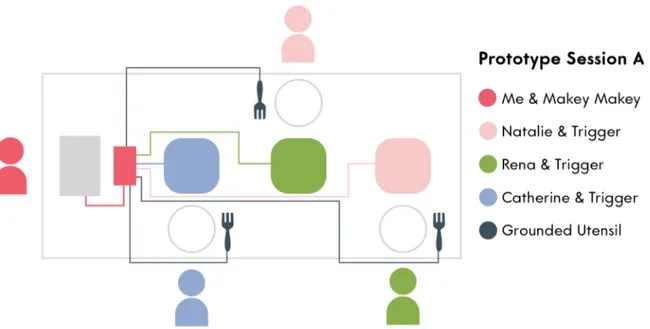

The ideal interaction is as follows: whenever a diner would use their utensils to take a portion of food onto their own plate, the auditory cues of the chef’s food preparation of the diner's favorite dish would playback. The diners would be seated along opposite sides of the table with myself at the head of the table with a notebook computer. This notebook computer would be running the Processing program to the Makey Makey board which I will monitor to confirm contact and address bugs. The notebook computer is the sole source of audio playback. A diagram of this setup can be seen in Figure 19 and 22. During the prototype, I will be video and audio recording in snippets for later observation. After the prototype, I will conduct a post-workshop interview to assess the success of the experience. Ultimately, the goal is to add a new layer of connection between the chef and the diner in addition to offering an entertaining way of interacting with the dishes in front of them and their fellow diners.

4.5 Ethical Considerations

At the beginning of each prototype testing workshop, I requested permission from each

participant to capture their likness in still images, video, and audio recordings. The related media such as audio and video recordings in addition to survey results can be found in Appendix E. The participants were also informed weeks before the session that the testing workshop would involve consuming food to which there was no objection. All meals were properly prepared and no illnesses or otherwise were reported. In the forthcoming section detailing the results of the prototype testing sessions, all of the names of the participants have been altered for privacy.

Figure 17: The setup prepared for Group B with food covered on the table

Figure 18: The participants and dishes during Prototype Session A

5.0 MAIN RESULTS & FINAL DESIGN

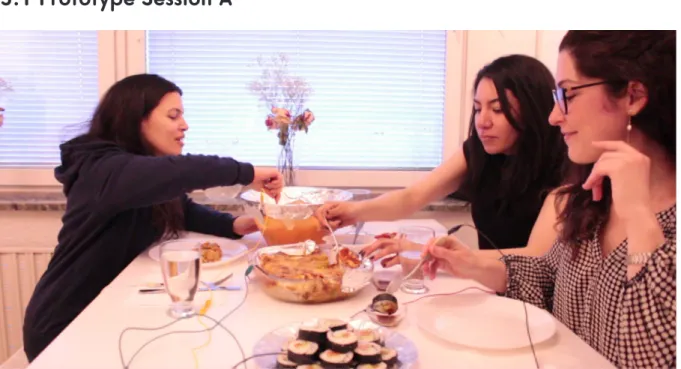

5.1 Prototype Session A

The first test session took place on May 4th with three women, Natalie, Catherine, and Rena. In this session, the participants were given a full set of utensils including a fork, spoon, and knife. In this case, the forks were grounded. They were given porcelain plates and a glass goblet. The three dishes selected from the three women’s favorite dishes were, Gado Gado (an Indonesian salad), enchiladas, and sushi rolls. For this session, the three selections were placed in the middle of the table for sharing with aluminum foil lining their serving containers in order to create a conductive current to activate the Makey Makey.

Being the first test session, it opened a lot of avenues for adjustments and iteration. The largest eye-opener came in the form of a lacking table setting set up. I did not provide serving utensils, so the participants used their spoons to move food from the communal sharing dishes to their personal dishes. This was a problem because, the only way to trigger audio would be to have the forks come in contact with the aluminum foil lining on the communal sharing dishes. So, with spoons as the more active utensil, rarely if ever did the participants trigger a change in audio track playback as they used their forks for personal use.

The group’s initial reaction to seeing a table of utensils and dishes hooked up to wires was, “Are you going to shock us?”. Granted, this is not a “look-and-feel” prototype, but it was not a welcoming reaction. These reactions were immediately dissuaded after seeing the food presented before them and the subsequent realization that it was their favorite dishes made for them. After assuring them that the utensils were safe to use, the group proceeded with their dinner flourished with audio cues from food preparation.

Natalie appreciated the natural sounds of the food preparation process, especially how all the different ingredients afford different types of sounds. She stated, “It’s really cool to hear the sound of the preparation, since it’s something that is normally hidden. The sounds themselves are awesome in the kitchen like the distinct sounds of chopping cucumber or popping

champagne.” Additionally, she enjoyed moments where I talked to myself as I cooked, as they felt natural and relatable.

Rena said, “I feel loved; all my problems disappear. When I heard the sounds, I was immediately transported back home. It reminded me of my mom or myself in the kitchen and just made me very aware of that moment. It triggered memories of home.” What stood out from her reaction was that the sounds offered a more powerful nostalgia for home rather than the visuals or flavors of the dish.

In Catherine’s case, the sounds brought on an exotic atmosphere of a sushi bar. She commented, “It felt like I was dining out, which made me happy. I felt excited as if we were out for dinner. The sounds transported me to a different place and changed my mood. It felt like there was more people and in a fuller place.” She appreciated that it wasn’t a sound she was familiar with, so it felt like she was having a new experience. It reminded her of open kitchen style restaurants and made her feel present in the moment. Despite being noisy or busy, the sounds did not bother her, but rather helped create an engaging atmosphere.

Despite, such positive feedback to the auditory cues, Catherine stated that she was unable to completely relax as she was trying to figure out exactly how all the wires on the table worked with another. Due to the way the prototype was set up, the cause and effect of the interaction between dish and utensil was never clear to the group. They never knew when they were triggering an audio track to be played. This initial ambiguity brought upon elements of exploration and playfulness, but overtime this became frustrating to the point where Catherine thought the prototype was not working at all.

For Natalie and Rena, they felt like they got closer to one another as they learned about each other’s favorite dishes and the significance they carried for each other. Catherine, on the other hand did not feel any closer, as the group was already well acquainted with one another, but she said by the end of the meal she felt significantly happier.

See Appendix B & E for further material.

5.2 Prototype Session B

Figure 20: The participants and dishes during Prototype Session B

The second test session took place on May 7th with two men and one woman, Spencer, Gary, and Isabelle. In this session, the dishes made for them were potato salad, pea soup, and curry. What became apparent with this set was that different types of foods have different affordances and ways of interaction. The selection in the previous session was much more diverse, but in this group all of the dishes could easily be eaten with just a spoon. So with this group, they were only given spoons which were grounded. This time, tin foil containers were used for

communal sharing dishes, serving utensils, and tin plates were used for the diners personal as well. This setup proved to be a vast improvement for facilitating conductivity as opposed to lining plates with aluminum foil.

The materiality of the tin foil containers and plates were intended to offer a more elegant technological solution opposed to aluminum foil and tape, however from the perspective of the diner, they thought I had purchased the dinner from restaurants due to the cultural connotations and expectations of disposable tableware. During the post-session interview they mentioned:

I: “The whole setting you have here may be influencing us. All of the aluminum has a very warzone feeling. It looks like we’re camping somewhere.”

S: “The layout is very geometric. It’s like “Sample A, Sample B, Sample C.” I felt like I had to be careful not to break the order and layout of the food.”

Gary’s first impression was that the sounds being played were an enhancement of real-time interactions with the food such as serving and moving food around. He made some technical observations and commented, “The technical difficulties of recording these ambient sounds is difficult, because you can really pick up the harsh sounds like the clashing of pots, but not softer sounds which would probably be more pleasing. So it can get kind of intense. But it offers a really cool insight of “Oh, that’s Kevin cooking for us,” so you can kind of imagine the work that was put in. If it wasn’t for the context, the sounds by themselves would be stressful.” He also expressed that it was a bit difficult to discern the three tracks from one another as they all had a similar ambiance to them. To this concern, Isabelle suggested that perhaps a performance art or instructional take on the food preparation process would offer another perspective on the origin of the dishes.

Continuing with Isabelle, she found the dining experience to be like a game or puzzle as she tried to figure out exactly what was going on. In her personal opinion, one of the greatest joys of eating with friends is actually preparing the food together, starting with the purchase of ingredients down to consumption. “You’re cooking together, helping each other, probably learning how to cook something that you don’t know. I think it’s something important in the process of sharing a meal.” She continues on saying, “The sounds themselves have no meaning by themselves. They’re just sounds of plates and water, which is actually more noisy than pleasing. The context makes the sounds interesting.”

At first, Spencer was trying to figure out how the sounds were mapped and how they were triggered, but found it difficult to pinpoint what was happening at the dinner table. He was trying to discern the significance and meaning of the audio cues, if they were callbacks to my time in the kitchen preparing the food or if the sounds were live and real-time that were being

enhanced as they ate. The first connection he made was that the sounds felt like an ambient background track as if someone was in the kitchen making food. Spencer also echoed Isabelle’s sentiments about cooking with friends, “I think it’s more fun than eating. It takes much longer so you just end up hanging out together.”

As far as feelings of nostalgia goes, the sounds themselves for Spencer were not specific enough to be tied exclusively to the preparation of potato salad as sounds of mixing and chopping are generic enough that it could have been any dish. This may be more prevalent for him, due to the fact that the potato salad is a dish his mother traditionally makes during the holidays when the entire family gets together so he has strong emotional expectations to the dish that I cannot replicate. For Gary, pea soup has a strong seasonal connection to winter in the form of comfort food, but did not feel like the auditory cues of food preparation enhanced this emotion. What was more profound from the auditory experience was the realization of how much time and effort went into the preparation of dinner. It brought the invisible or behind the scenes aspects of dining to the foreground and really enhanced the feeling of, “Oh wow, somebody made this for me.” In Isabelle’s case, the sounds did not offer an enhanced experience, but the food selection reminded her of specific experiences and memories she has had. She expressed that she felt that the experience was valuable, because she was able to learn about the group’s favorite foods and enjoyed being able to bring to the table the stories that each person has with their dish. As the food preparation process became the topic of the table, the group shared personal

anecdotes of food preparation from family, friends, and work colleagues. This led to an expanded conversations ranging from delicacies of various ethnic cuisines such as the significance of a fish’s head in Chinese cuisine to different naming conventions between foods and their origin such as pigs and pork or beef and cow.

I: “The sounds remind me of home and my mom cooking because she would almost never sit down and eat with us. She would be cleaning the stuff she used to cook while we are eating.”

S: “My dad would do that too.”

I: “She would eat a little bit and then go back to cleaning.” G: “Yeah, thats like my grandmother.”

S: “Do you notice that usually the person that cooks the meal, doesn’t get to enjoy the meal? They’re always in the back taking care of stuff.”

G: “Especially during a barbeque, while they’re preparing the food, they eat a little bit to taste test before he serves it. That’s how he ends up having his meal.”

Overall, this group had a more engaging experience with this iteration of the table setting thanks to the feedback from the first group. There was a significant increase in conversation that stemmed from the auditory cues of food preparation that led to story sharing personal anecdotes as detailed above. As expected, the group offered many insights in their behavior to be considered for adjustment during the third test session.

5.3 Prototype Session C

Figure 22: The participants and dishes during Prototype Session C

The third test session took place on May 12th with three women, Blanche, Alice, Robin. In the final session, the dishes made were an eggplant parmigiana, moussaka, and steak with roasted vegetables. In the third installment of this test session, the participants were given grounded forks and tin foil plates. None of the communal shared dishes were active triggers for audio cues. The more significant change in this session’s setup was the composition of the audio tracks. The two previous groups had audio tracks that were unedited and followed the entire course of the cooking process. The three key pieces of feedback from the previous groups that seemed interesting to test were:

1. The most interesting and personal parts of the food preparation recordings were parts where, I, the cook was making comments to myself such as measuring ingredients. 2. The sounds are all very similar and repetitive so it may be necessary to alter the recordings in a way that offered more variety.

3. Obtaining the ingredients is also an important part of the food preparation process, so it could be interesting to record this step for playback as well.

Subsequently for this third group, the process of grocery shopping was recorded in addition to commentary during the cooking process and then the audio recordings were edited in order to remove excessive white noise and periods of time in the recording that were not deemed as actionable. In an attempt to add another layer of individuality, I played music from three different artists of different genres with each one paired to a different dish so that when playback occurred each audio track would have a distinct feeling from each other when switching back and forth.

Figure 23: An illustration depicting Prototype Session A’s table setup

As the group began their meal, the audio tracks started playing beginning with the grocery shopping phase. The three of them took a moment to pause and figure out where the sound came from and how it was triggered. The three women had completely different approaches to the prototype as the night progressed. Blanche was ultimately more interested in the meal in front of her. Alice took a considerable amount of time and effort into playing with her utensils and plates in trying to figure out how the prototype worked. At one point she directed and coordinated with the other two participants in attempts to understand what triggered the audio cues. She said, “There was one point where I asked everyone to put their utensils down and we had about ten seconds of uninterrupted sound from one dish and it was really awesome. That was really cool, and I feel like the cooking sounds really gives depth to the whole experience.” This group was the quickest to make the connection between the auditory cues and the interaction between the utensils and dishes. Alice explained, “I found myself always looking at the LED that was lighting up. If it wasn’t there than I would have given up earlier on trying to figure it out. When I realized that the LED lights up when I touched, I knew something was happening and working and I needed to figure that out.” However, she also expressed that she was lacking control of how the prototype behaved. Blanche concurred, “I agree that it would be nice to have control. It’s very intrusive if you don’t have control over it.”

Robin also took some time to figure out the prototype, but grew frustrated and ended up focusing on filtering out the sounds so that she could enjoy her meal. Not being able to figure out the wire configuration did not bother her since it did not hinder her dining experience. However, not figuring out what triggered the sounds became frustrating towards the end of the meal because it was preventing her from enjoying her meal. She said, “I enjoyed the talking parts. I think it was the most interesting and I wanted to hear what you were saying, but I couldn’t hear it because of the other sounds and that annoyed me. When the sound played longer it actually engaged me. You can actually hear it, otherwise there is too much interruption.”

Similarly to the second group, this group expressed positive feelings towards audio snippets where I spoke to myself during the food preparation process. Robin mentioned, “I was able to make the connection [that you made the dish] because you were talking about moussaka.” Alice added, “There are parts that I absolutely love, like when you mumble and murmur to yourself. I actually really liked those parts, because I’m not a person that is very interested in food, and that actually got me interested. Like at one point you mentioned ‘carrots’ and I thought, “Oh, there’s carrots in this dish?”. It made me actually think of the food and what it is is made of and the

cultural background of the dishes.” However, Blanche’s responses are an outlier in comparison to the feedback from the rest of the participants. She explained, “I really really didn’t like that someone was talking. I grew up in a family where we would never ever have the TV on while we were eating because we were supposed to interact with each other. I appreciated the ambient sounds more than speaking.”

To elaborate, Blanche explained that she wasn’t interested in the sounds of me talking to myself while cooking or the sounds of the food being put together, but rather she said, “I was paying attention to the atmosphere and background of the food preparation. Like in a restaurant, to find out what kind of person made this, what mood were they in, were they rushing? There’s this feeling of transparency.” She compared the auditory experience to that of a restaurant where the kitchen was open and visible to the patrons, “It reminds me of those restaurants where the kitchens are open and people can actually see the cooks making the dishes. I love that, that’s really cool. If you could create the layout of those restaurants with sound then that would be very cool. That’s a nice experience.” As mentioned before, for this group I deliberately played music in the background while I cooked the meal to create a deeper atmosphere for each track. Blanche reacted positively to those auditory cues, meanwhile the other two did not notice them:

B: “I liked that [music was playing in the background]. R: “I didn’t notice it.”

A: “I didn’t hear the music.”

B: “I noticed immediately actually. It helped me experience what the cook was experiencing.”

R: “I do like music while eating. Like background music at a restaurant.” A: “I think music in public spaces goes very naturally so you tend not to notice it.”

The realization that this group had many more frustrations compared to the previous groups came as a surprise. The adjustments made to this group’s set-up really affected how they interacted and behaved at the dinner table. Alice best described it as a ‘love-and-hate’ relationship. She remarked, “In general, I really enjoyed the temporal aspect and the love for making our favorite foods. I was super interested in how you prepared these dishes. It felt like discovering the dish. I hated the ‘shhh’ noises in the background though. I wish I could experience this again, but without [the grocery shopping] sounds so it would just be very clean sounds of you talking or chopping vegetables.”

Table 1: This table displays key differences in setup for the three prototype sessions

6.0 EVALUATION AND DISCUSSION

6.1 Attributes of Celebratory Technologies

It is only appropriate that the results of the test session are evaluated against the attributes of Celebratory Technologies as mentioned in the research question: “How can celebratory technologies enhance social engagement between diners in commensality and raise awareness of the otherwise hidden process of cooking using auditory cues of food preparation?” I would like to call to attention that although there are six defined qualities of Celebratory Technologies, a design artifact created under this concept does not need to draw from all six. After reviewing the results of the three test sessions, I believe the following four to be discussed are the qualities that this artifact draws upon the most. In analyzing the results of the user test session, I would like to clarify some taxonomy to facilitate the evaluation.

In this segment of the paper I will be discussing the results of the three prototype sessions and evaluating them. The metrics for evaluation will be the two key pieces of theory introduced earlier in the paper: Grimes and Harper’s Celebratory Technologies and Hupfeld and Rodden’s Laying the Table for HCI.

Of course there are other pieces of interaction design theories and methods, such as the aesthetics of interaction design, to use as metrics of evaluation, but I felt like the aforementioned literature is tied much more closely to the field of HFI. Following the analysis, future considerations are discussed for development. Knowledge contributions to the field are discussed in the Conclusion.

Session A

Active Personal

Plates Communal DishesActive Shared GroundedUtensils Heavily EditedAudio Tracks

Session B

6.1.1 Gifting

The saying goes, “friends are family you choose” and I think that holds particularly true for an assortment of international students. I have already mentioned that the auditory cues triggered memories of home and family for a handful of the participants. What I found more engaging during the prototype was that as they dined and listened to the sounds the participants naturally started talking about their families. To reiterate, Rena, Gary, and Isabelle stated that the

prototype reminded them of their mothers and grandmothers cooking in the kitchen. As mentioned in the results, potato salad is a dish that Spencer’s mother traditionally makes during

6.1.3 Family Connectedness

People have different reasons for why their favorite dish is their favorite. The reasons from the nine participants ranged from as intimate as “it reminds me of family” (Natalie) to as detached as “I rarely get to eat it” (Isabelle). However, these are results from taste and sight. The question at hand is if auditory cues of food preparation induced feelings of pleasure and nostalgia. Group A had the strongest positive feedback from the auditory cues. This held true for Rena in particular saying, “When I heard the sounds, I was immediately transported back home. It reminded me of my mom or myself in the kitchen and just made me very aware of that moment. It triggered memories of home.” Catherine did not feel so much Nostalgia as she did for Pleasure. The sounds were able to alter her perception of space, claiming, “The sounds transported me to a different place and changed my mood. It felt like there was more people and in a fuller place.” Group B and C had much more reserved feelings from the auditory cues. For Gary, Isabelle, Alice, and Robin they were most interested in moments where I was talking to myself while preparing food. For them, it offered depth and personality as well as a way to discover and learn about the dish being prepared.

6.1.2 Pleasure and Nostalgia

In this prototype, Gifting isn’t a quality that can be tied to the audio cues driven by interaction with the artifact. However, that does not mean that it isn’t an important part of the experience of the prototype. As stated before, the dishes prepared for each group are the favorite dishes they submitted in the first survey. I chose to proceed with these dishes as I believed they would trigger the most positive emotions towards Pleasure and Nostalgia. A number of the dishes made can be considered comfort foods in that they are connected to feelings of nostalgia, indulgence, convenience, or being physically warm foods (Grimes and Harper, 2008). Isabelle described the joy of eating comfort foods as “being wrapped in a blanket.” In a study of Swedish retired women by Birgitta Sidenvall, Margaretha Nydahl, and Christina Fjellström in 2000 they describe the entire process of preparing a meal from deciding what to serve to the presentation of the meal as a gift.

1. Prototype will refer to the overall dining experience including the act of eating and triggering auditory cues of food preparation

2. Artifact will refer to the physical setup of the Makey Makey board in conjunction with the attached items such as plates and utensils

6.1.4 Relaxation

We all relax in different ways and what relaxes one person may not relax another. Natalie mentions that she finds the sounds of chopping vegetables soothing. Rena echoed that statement saying that she felt like all of her problems went away. Blanche expressed interest in ambient sounds that created an atmosphere that allowed her to experience what I experienced in the kitchen such as background music, shuffling footsteps, or boiling water.

Group A was probably the most relaxed by the auditory cues and Group C was by far the most stressed by it. Group A’s audio tracks had no edits performed on them and were by far the most natural. For the participants in Group B, they found the sounds of actual cooking to be mundane, as if they could be attached to any recipe and that the sounds would be irritating if not for the particular context of a friend cooking their favorite meal for them. In Group C’s case, the soundtracks were the most heavily curated along with the addition of audio recording of grocery shopping and my narration of my cooking process. Group C, was the only group that asked for the artifact to be stopped due to it being a nuisance to the dining experience. These results suggest that a fluid and natural playback recording with intermittent comments of the cooking process would be the most appealing for a wide audience.

6.2 The Ecologies of Domestic Food Consumption

As mentioned in the Theory section, Hupfeld and Rodden list four considerations for designers pursuing HFI, which I will now use to assess the qualities of this thesis project’s prototype. 1. Interaction designers may want to think about the degree to which their designs foreground and background the nature of occasion.

Throughout the prototype testing sessions it became clear that the more I inserted myself into the audio recordings, the more I brought the experience from an ambient space to an active space. the holidays when the entire family gets together. For him, the auditory cues did not trigger feelings of nostalgia or pleasure as his association with the dish was far richer than I could replicate. Robin shared that her aversion to cooking is influenced by her mother’s attitude toward cooking. Blanche shared that as a child she wasn’t a person who spoke much unless she had food in front of her. She expressed that she loves talking to people around the table during mealtime and she finds the table to be a sacred place.

Needless to say, each participant has a colored history with food based on their ethnicity, culture, and upbringing with their family. For some, auditory cues triggered memories of home and for others the auditory cues brought up anecdotes that they then shared with the other participants. I’ve known the participants for a better part of a year, but learned so much more about their families and childhoods in the prototyping session that I may have never found out if not for this thesis project.

6.3 Future Considerations

In future explorations of this project there are a number of things to keep in mind. As stated in the above discussion, the audio playback was most pleasant in Group A and became increasingly disrupting for Group C as more elements were introduced into the recording. The recordings should avoid the noisy setting of a grocery store and narrations of food preparation should not be excessively forced. Blanche aptly suggested, “I do think the background sounds of the food preparation needs to be curated. If it was just ‘chop-chop-chop’ the entire time, I can see how that could be annoying. I should be able to see the intent of the prototype to make me have a certain experience while I am eating.”

This provided mixed responses based on each participant’s dining habits and preferences. As mentioned, some enjoyed the commentary meanwhile others like Robin became frustrated with the prototype as it began to intrude her dining experience.

2. Interaction designers might wish to think about how their designs draw up on the boundaries between independence and socialization and the gestures that signal them. Robin mentioned, “The talking part would have been really nice if I was eating alone. When you’re talking, it’s really interesting and really nice, but it doesn’t seem to go well with the group interaction at the table because it becomes distracting [when it interrupts the conversation at the table].” The parts involving speech aside, the ambient sounds gave off a much more positive reaction where the diners were commenting and talking to each other about what they heard. Also, due to the wired set up of the prototype, the diners had to pass plates around and serve food for each other which added a layer of socialization.

3. Interaction designers seeking to augment dining my want to think about the affordances of their designs to promote either sharing within the context or isolation and removal from it.

Participants in Group B mentioned that the auditory cues of food preparation by themselves offer no benefit, but due to the context and immersion the prototype offered, they could begin to see some value in the experience. Group C was the only group that offered the possibility of greater immersion in a solo dining experience and this is further discussed in the forthcoming Future Considerations section. However, I do think that the conversations that naturally developed from experiencing the prototype with friends and eating your favorite meal offered a space to share stories surrounding commensality.

4. Interaction designers may want to extend their design consideration beyond the immediate context to which their design will be deployed and consider the potential trajectories a dining artefact might take over its lifetime of use.

In its current state, the prototype is very much an object that is unpolished and is best suited for an isolated and controlled environment. However, Catherine and Blanche both mentioned that the auditory cues of food preparation brought upon nuances of dining out or a restaurant with an open kitchen. Other contexts like solo dining is further discussed in the next section.