MALMÖ S TUDIES IN SPORT SCIEN CES V OL 32 JO AKIM IN GRELL MALMÖ UNIVERSIT

WHA

T

DOES

IT

TAKE

T

O

BE

SUCCESSFUL

HERE?

JOAKIM INGRELL

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BE

SUCCESSFUL HERE?

A longitudinal study of achievement motivation

in youth sport

Malmö Studies in Sport Sciences Vol 32

© Copyright Joakim Ingrell Omslag Kim Berkhuizen ISBN 978-91-7877-007-6 (print) ISBN 978-91-7877-008-3 (pdf) ISSN 1652-3180

Malmö University, 2019

Faculty of Education and Society

JOAKIM INGRELL

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO

BE SUCCESSFUL HERE?

A longitudinal study of achievement motivation in

youth sport

Publikationen finns även elektroniskt, se muep.mau.se

ABSTRACT

The focal aim of this dissertation project centers on understanding the

importance of some of the underlying factors responsible for the

sociali-zation of achievement motivation in youth sport and its affective

out-comes. Furthermore, this dissertation project focuses on the specializing

stage of development, more specifically, student-athletes (N = 78)

at-tending a compulsory school with a sports profile.

This dissertation project was guided by the theoretical frameworks

provided by achievement goal theory (Nicholls, 1984, 1989), implicit

theories of ability (Dweck, 2000), Ames’ (1992a, 1992b) motivational

climate, Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect (Marsh, 1984; Marsh & Parker,

1984) athletic burnout (Raedeke & Smith, 2001), and gender as a social

institution (Lorber, 1994).

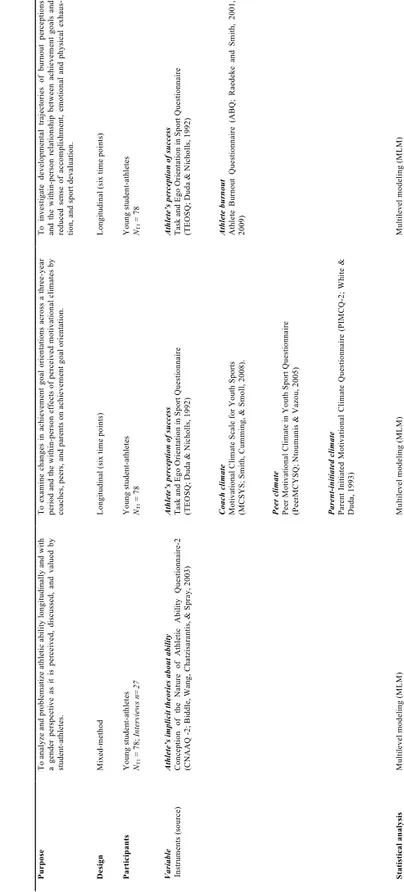

In the first study, the aim was to analyze and problematize athletic

ability longitudinally and with a gender perspective as it is perceived,

discussed, and valued by student-athletes. A mixed method approach

was used in this study consisting of quantitative analysis (multilevel

modeling) of a three-year, six-wave data collection (N = 78).

Further-more, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 27 of the

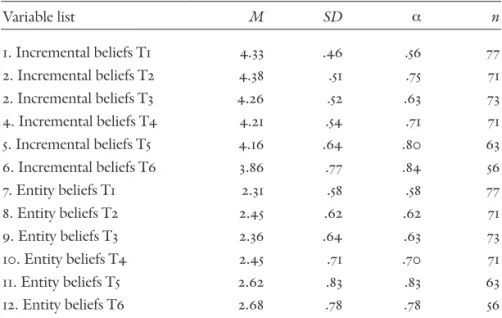

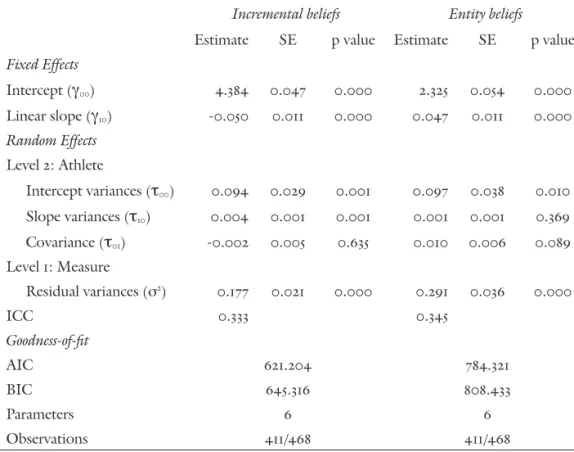

student-athletes. The two main results of this study were that entity beliefs

in-creased, and incremental beliefs decreased during the three-year period,

and that gender added a further understanding of the beliefs of

student-athletes regarding athletic ability.

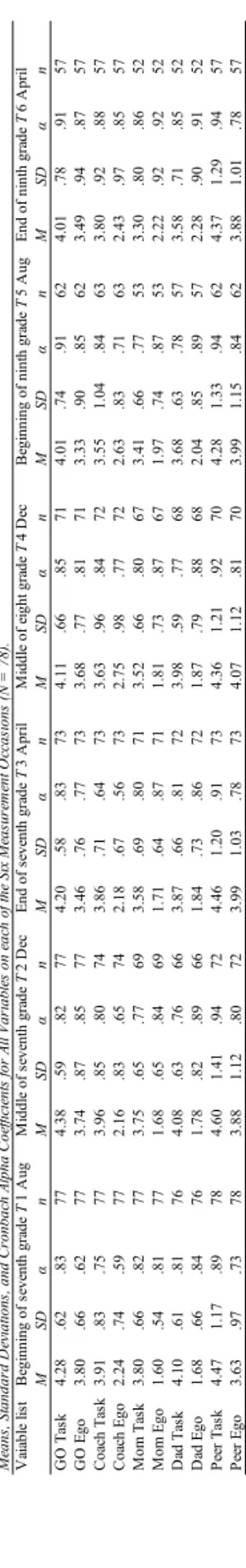

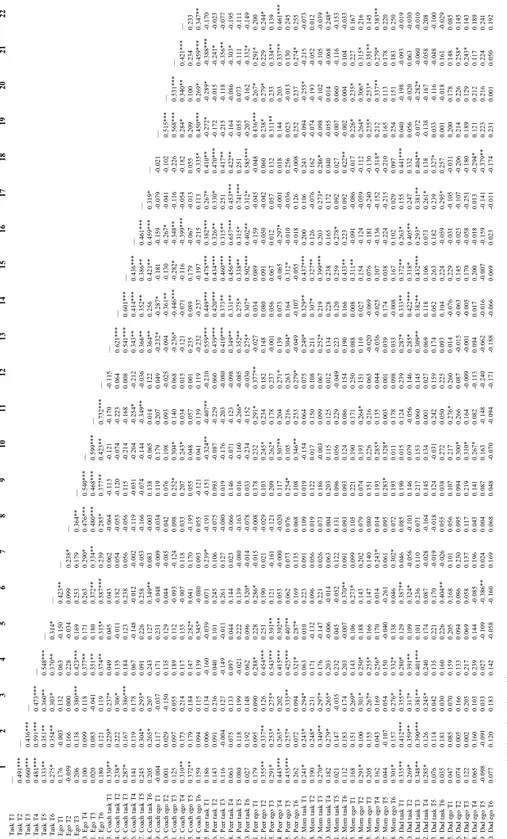

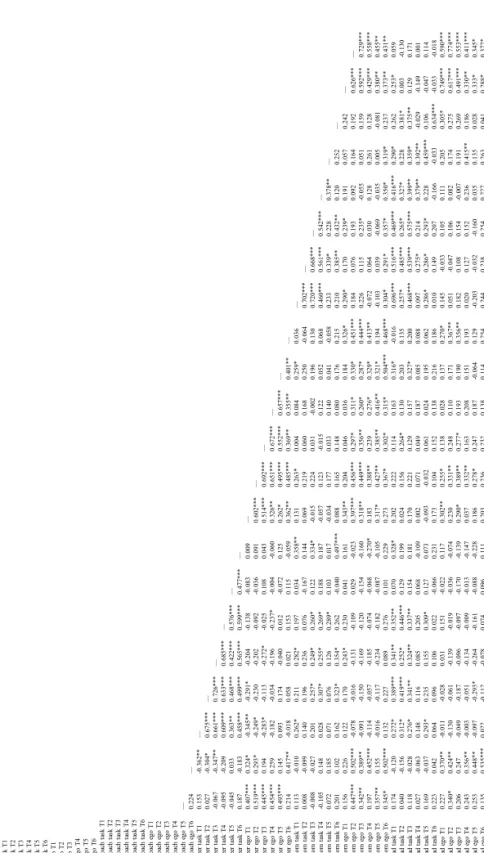

The second study aimed to examine achievement goals in youth sport

longitudinally and the within-person effects of perceived motivational

climates by coaches, peers, and parents on achievement goal

orienta-tions. The student-athletes (N = 78) completed a multi-section

question-naire, six times over a three-year period, assessing the study variables

and the multilevel modeling analysis revealed that both the task

orienta-tion and the ego orientaorienta-tion decreased for this age group over the

three-year period. Furthermore, the perceived task involving peer climate was

significantly and positively related to task orientation, and perceived

ego-involving coaching climate was significantly and positively related

to ego orientation.

In the third study, the aim was to examine the developmental

trajecto-ries of student-athlete burnout perceptions and the within-person

rela-tionship between achievement goals and burnout perceptions. The

par-ticipants (N = 78), time frame, and measurement points were the same in

this study, as in studies I and II. The results from the multilevel growth

models revealed that burnout perceptions increased for this age group

over the three-year period. Furthermore, task orientation was

signifi-cantly and negatively related to a reduced sense of accomplishment and

sport devaluation.

The findings from this dissertation project highlight some of the

com-plexity of achievement motivation in youth sport; the relationships

be-tween this type of motivation and the context, in this case, a school with

a sports profile, and organized sports, and significant others such as

coaches, peers, and parents. Furthermore, the results from this

disserta-tion project underline the advantage of considering a specific

develop-mental stage when studying achievement motivation in youth sport

lon-gitudinally.

SWEDISH SUMMARY

Syftet med detta avhandlingsprojekt var att förstå vikten av några av de

bakomliggande faktorer som kan tänkas vara ansvariga för

sociali-seringen av prestationsmotivation inom ungdomsidrotten samt dess

af-fektiva konsekvenser. Vidare fokuserade detta avhandlingsprojekt på det

specialiserande karriärstadiet, mer specifikt elever (N = 78) som gick i

en idrottsprofilerad grundskola.

Avhandlingens teoretiska ramverk var: målorienteringsteorin

(Nicholls, 1984, 1989), ”mindsets” (Dweck, 2000), motivationsklimat

(Ames, 1992a, 1992b), Big Fish-Little-Pond Effect (Marsh, 1984;

Marsh & Parker, 1984) idrottslig utbrändhet (Raedeke & Smith, 2001)

och kön som social konstruktion (Lorber, 1994).

I den första studien var syftet att analysera och problematisera

idrotts-lig förmåga, longitudinellt och med ett genusperspektiv, utifrån hur det

uppfattades, diskuterades och värderades av de idrottande eleverna. En

kombination av kvantitativa och kvalitativa metoder användes i denna

studie bestående av en kvantitativ analys av en treårig datainsamling (N

= 78) samt semistrukturerade intervjuer med 27 av de idrottande

elever-na. De två huvudsakliga resultaten var att synen på idrottslig förmåga

som statisk, icke kontrollerbar och nedärvd ökade medan synen på

id-rottslig förmåga som förändringsbar, utvecklingsbar och kontrollerbar

minskade. Vidare gav genusperspektivet en ytterligare förståelse för

elevernas föreställningar gällande idrottslig förmåga.

Syftet med den andra studien var att undersöka unga idrottares

målo-rientering över tid samt relationen mellan målomålo-rienteringar och det

upp-levda motivationsklimatet, skapat av tränare, föräldrar och kamrater.

Id-rottande elever (N = 78) svarade på flertalet enkäter, sex gånger över en

treårsperiod, och den statistiska analysen visade att både

uppgiftsorien-tering och egoorienuppgiftsorien-tering minskade för denna åldersgrupp. Ett

uppgifts-orienterat kamratklimat var statistiskt signifikant och positivt relaterat

till uppgiftsorientering. Resultatet visade också att upplevt egoorienterat

tränarklimat var statistiskt signifikant och positivt relaterat till

egoorien-tering.

I den tredje studien var syftet att undersöka idrottande elevers

ut-vecklingskurvor gällande idrottslig utbrändhet i form av emotionell och

fysisk utmattning, reducerad syn på idrottskompetens och nedvärdering

av idrottens betydelse samt relationen mellan målorienteringar och de

tre variablerna kopplade till idrottslig utbrändhet. Deltagarna (N = 78),

tidsramen och mätpunkterna var desamma i den här studien som i studie

I och studie II. Resultaten visade att idrottslig utbrändhet ökade under

treårsperioden. Dessutom var uppgiftsorienteringen statistiskt

signifi-kant och negativt relaterad till reducerad syn på idrottskompetens och

nedvärdering av idrottens betydelse.

Detta avhandlingsprojekt lyfter fram en del av komplexiteten gällande

prestationsmotivation inom ungdomsidrotten, relationerna mellan denna

typ av motivation och kontexten, i detta fall en idrottsprofilerad

grund-skola, organiserade idrott samt betydelsefulla skapare av

motivations-klimatet som tränare, kamrater och föräldrar. Vidare understryker

resul-taten från detta avhandlingsprojekt fördelen av att överväga ett specifikt

utvecklingsstadium vid longitudinella studier av prestationsmotivation

inom ungdomsidrotten.

LIST OF SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

The present doctoral dissertation is based on the following three studies:

Article I

Ingrell, J., Larneby, M., Johnson, U., & Hedenborg, S. (2019).

Student-athletes’ beliefs about athletic ability: A longitudinal and mixed method

gender study. Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum, 10, 117-138

Article II

Ingrell, J., Johnson, U., & Ivarsson, A. (2019). Achievement goals in

youth sport and the influence of coaches, peers, and parent: a

longitudi-nal study. Manuscript submitted for publication

Article III

Ingrell, J., Johnson, U., & Ivarsson, A. (2018). Developmental changes

in burnout perceptions among student-athletes: An achievement goal

perspective. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology,

doi:10.1080/1612197X.2017.1421679

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 7

SWEDISH SUMMARY ... 9

LIST OF SCIENTIFIC PAPERS ... 11

Article I ... 11

Article II ... 11

Article III ... 11

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 15

INTRODUCTION ... 19

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS ... 21

Achievement motivational theories ... 21

Achievement goal theory ... 21

Implicit theories of ability ... 25

Motivational climate ... 26

Longitudinal studies ... 31

Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect ... 33

Athletic burnout ... 35

Gender as a social institution ... 36

Why the theoretical frameworks? ... 39

AIMS FOR THE DISSERTATION ... 42

MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 43

Ethical considerations ... 43

Mixed method ... 45

Samples and procedures ... 52

Measures ... 54

THE EMPIRICAL STUDIES ... 58

Study 1: Student-athletes’ beliefs about athletic ability: A longitudinal and mixed method gender study ... 58

Background and aim ... 58

Method ... 59

Results and discussion ... 59

Study 2: Achievement goals in youth sport and the influence of coaches, peers, and parents: a longitudinal study ... 62

Background and aim ... 62

Method ... 63

Results and discussion ... 63

Study 3: Developmental changes in burnout perceptions among student-athletes: An achievement goal perspective ... 64

Background and aim ... 64

Method ... 65

Results and discussion ... 65

GENERAL DISCUSSION ... 67

Limitations and suggestions for future research ... 73

REFERENCES ... 76

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Finally!

Writing a dissertation is a lonely and anguished journey, and now that

I have arrived at the finish line, I want to begin this chapter by patting

myself on the shoulder. However, I doubt that I could have done it

with-out help and support from the people around me.

To my main supervisor, Urban Johnson, it has been great to have you

on my journey from the start at Halmstad University in 2003 to the

completion of this dissertation. I am very grateful for the way you have

approached me and my thoughts with empathy and professionalism.

Although there has been a geographical distance between us, you have

always been close at hand to give constructive feedback when I needed

it.

To my other supervisor, Tomas Peterson, I want to say thank you for

your autonomy support. Also, I want to thank you for making me, as a

sport psychologist, feel included at the Department of Sport Sciences.

I also want to take this opportunity to thank Andreas Ivarsson. You

were always there when needed to guide me through the tricky but

in-teresting world of statistics.

To the principal, teachers, and most of all, the student-athletes at the

sports school, without you, there would not be any dissertation. Thanks

for contributing!

The colleagues at the Department of Sport Sciences should have a big

thank you! Over the years, I have been involved in interesting

collabora-tions, a special thanks here to Sverker Fryklund, Torsten Buhre, Jenny

Vikman, and Mats Johnsson.

Another colleague, a fellow doctoral researcher, and friend, Marie

Larneby, should have a big thank you. We have participated in the same

research project, supported each other both inside and outside of work,

which has led to a friendship I truly treasure.

For me, the climate is very important, within sports or work. Some

people who meant a lot to the working climate and who I want to thank

are Emelie Niléhn, Björn Hansson, and Annika Larsson.

I would also like to thank the present and former doctoral students Jens

Alm, Jyri Backman, Anna Bergenfeldt Fabri, Daniel Bjärsholm, Sepand

Mashreghi Blank, Niklas Hafen, Anna-Maria Hellborg, Alexander

Jans-son, Kalle JonasJans-son, Isak Lidström, Matilda Lindberg, Mattias

Melkers-son, Julia Rönnbäck, Sofia Sebelius, Marit Stub Nybelius, and Joakim

Åkesson. There are many memories, but it is the little things that stick

with you, such as a nice cup of coffee or hilarious lunches.

I would also like to thank Magnus Lindwall for the inspirational

versation we had during my 90% seminar. I appreciate how you

con-ducted the seminar, and your comments, that took the work forward.

I would also like to thank Susanna Hedenborg for being the senior

re-searcher at the department who gave comments on my manuscript after

the 90% seminar. Furthermore, you have contributed to many interesting

learning activities during my time as a doctoral student.

During my time at the Department of Sport Science, the department

has been run by three individuals who all, in different ways, have been

meaningful to me.

To Aage Radmann, I would like to say thanks for always supporting

me, reinforcing what I did well, and constructively correcting me when

needed.

To Kristian Sjövik, thank you for giving me the opportunity to follow

my heart and be able to move to Stockholm for a while for me to carry

out my commitments from a distance.

Related to this, I would also like to thank Liselotte Ohlson at the

Swedish Sports Confederation for creating both a physical place for me

to sit in and a context for me to grow in during my time in Stockholm.

A big thank you also to Torun Mattson, who went seamlessly from

being a fellow doctoral researcher to becoming our new head of

depart-ment. Thank you for listening to all aspects of me.

My family in Landskrona, Glumslöv, Uddevalla, and Malmö should

have a big thank you for all the love and support. You are absolutely

fantastic! An extra big thank you goes to my mother, who has always

been there.

What would life be without friends? Two friends I especially want to

thank are Michael and Kim. Thanks for being there even when the

geo-graphical distance between us was big and/or when the time apart has

been too long. I would also like to thank Kim for allowing me to use one

of his works, Urban Abstract III, as a motive for the cover of this

disser-tation. I thought this work represented the dissertation's content

brilliant-ly. The growth curves in this dissertation are linear, but if you tear off

the surface, the chaos representing adolescence is revealed.

Also, a shout out to all involved in the yearly, and legendary, crayfish

party. I hope you all know what you mean to me!

I am saving the best for last.

Moa, the love of my life, no words can describe how thankful I am. I

am still amazed at how much love, strength, and wisdom you have. You

were my rock when I was low, but more importantly, you threw yourself

around me and celebrated together with me in moments of success. I

love you and treasure everything we have.

Hilda, my wonderful daughter, oh, how I love you. I will always let

you know, but still, if you ever open up this page, I want you to read

about how you have contributed to this dissertation far beyond what you

ever can comprehend. Being mindful with your curiosity in play, when

you master new skills, and soaking up every laugh you provide has been

a “happy place” necessary for me to go on.

To My, you are one week old when writing this, but I have a lifetime

of love for you.

Joakim Ingrell

INTRODUCTION

Millions of young people participate in organized sport and as argued by

many researcher (e.g., Bangsbo et al., 2016; Støckel, Strandbu, Solenes,

Jørgensen, & Fransson, 2010; Zaff, Moore, Papillo, & Williams, 2003),

children’s early involvement in organized sport is often considered to be a

key opportunity for the development of movement skills, social skills,

self-esteem, and the maintenance of health through physical activity.

However, whether such outcomes are realized could to a large extent be

dependent on the type of influence exerted by social-environmental

fac-tors during these influential formative years (Bélanger et al., 2015;

Wagnsson, 2009). Statistics from the Swedish sports confederation

(Sports in numbers, 2017) show that between the years 2014-2015

ap-proximately 70% of all children between 12-15 years old in Sweden

par-ticipated in organized sport at least one day a week. Because the sports

environment is inherently a competence and achievement context (Støckel

et al., 2010), motivational factors play an important role. Although

im-portant aspects of individuals’ motivations are determined by their own

beliefs, cognitions, and values (Nicholls, 1989), significant influences can

also be exerted by key social agents like coaches, peers, and parents

(Ames, 1992a, 1992b). These three social agents are perhaps the most

consistent and reliable sources of influence across the athlete’s sporting

experience. About athletes sporting experience, models of athletic career

progression have been proposed by both Côté, Baker, and Abernethy

(2003) and Wylleman, Alfermann, and Lavallee (2004). The

initia-tion/sampling stage refers the early career and is characterized by

partici-pants who are generally prompted to try several different sports to see if

they either enjoy them, have some talent, or perhaps both (Côté al., 2003;

Wylleman et al., 2004). Following this period, athletes tend to focus on

one or two sports in which they specialize, learning the key skills, tactics,

and rules. This specializing phase tends to occur from around the age of

11–12 years. The next developmental stage is termed the

invest-ment/mastery stage (Côté al., 2003; Wylleman et al., 2004) and begins

from approximately 15 years of age, depending on the sport. The

invest-ment/mastery stage is defined by a heavy and exclusive focus on

deliber-ate practice, specialist coaching in a single sport, and markedly decreased

parental involvement (Côté et al., 2003). In contrast, it is hard to delineate

the specializing career stage because it is characterized by change. These

changes include (a) decreasing number of sports/activities; (b) a decrease

in deliberate play, being replaced with deliberate practice, and (c) gradual

changes in the roles of coaches (from “helper” to “specialist”), parents

(from direct to indirect involvement), and peers (from

stimulation/co-participation towards the fulfillment of emotional needs) (Côté et al.,

2003). The final stage is called recreational (Côté al., 2003) or

discontinu-ation (Wylleman et al., 2004) and during this period, athletes stop

partici-pating in competitions on the level they had previously achieved but may

continue training for recreational purposes.

This dissertation project is part of an interdisciplinary research project

with the overall purpose of studying the sociological, physiological, and

psychological factors that could potentially affect continuous and/or

successful participation in sports. Furthermore, this dissertation project

focuses on the specializing stage of development, more specifically,

stu-dent-athletes attending a compulsory school with a sports profile. As

de-scribed above, children and young adolescents in the specializing stage

are argued to be influenced by socio-environmental factors that

poten-tially change during this meaningful time period. Hence, this

disserta-tion project has a longitudinal focus on the achievement motivadisserta-tion of

young student-athletes regarding their participation in sport. The focal

aim of this dissertation project, therefore, centers on understanding the

importance of some of the underlying factors responsible for the

sociali-zation of achievement motivation in youth sport and its affective

out-comes. Furthermore, when studying the social influence on these young

student-athletes achievement motivations, I am examining the reasons

behind the motivated actions and how coaches, parents, and peers

influ-ence these reasons over time.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

The foundation for this dissertation project rests upon the theoretical

frameworks used as the lenses through which the research problems and

research questions are being evaluated. Those frameworks are:

achieve-ment goal theory (Nicholls, 1984, 1989), implicit theories of ability

(Dweck, 2000), Ames’ (1992a, 1992b) motivational climate,

Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect (Marsh, 1984; Marsh & Parker, 1984), athletic

burn-out (Raedeke & Smith, 2001), and gender as a social institution

(Lorber, 1994). These theoretical frameworks will be described in more

detail below.

Achievement motivational theories

The theories regarding achievement goals were developed in the early

1980s by, for example, John Nicholls (1984), Carole Ames and Russel

Ames (1984), and Carol Dweck (1986). Each of these theorists has

dis-tinguished between two distinct goals for achievement behavior and

have also offered similar enough conceptualizations to be referred to

to-gether as “the dichotomous achievement goal model.” In this model,

achievement goal is defined as the purpose of engaging in achievement

behavior (Maehr, 1989).

Achievement goal theory

Achievement goal theory (AGT) is a social-cognitive theory that

as-sumes that the individual is an intentional, rational, goal-directed

organ-ism and that achievement goals govern achievement beliefs and guide

subsequent decision making and behavior in achievement contexts. In

developing AGT, Nicholls (1984, 1989) claimed that a person’s internal

sense of ability was a main achievement motive but proposed that in

achievement contexts, ability could be construed in two different

man-ners specifying the goals (purposes or reasons) that direct

achievement-related behaviors. Nicholls (1984) stated:

Achievement behavior is defined as behavior directed at developing or demonstrating high rather than low ability. It is shown that ability can be conceived in two ways. First, ability can be judged high or low with reference to the individual’s own past performance or knowledge. In this context, gains in mastery indicate competence, second, ability can be judged as capacity relative to that of others. In this context, a gain in mastery alone does not indicate high ability. To demonstrate high capacity, one must achieve more with equal ef-fort or use less efef-fort than do others for an equal performance. (Nicholls, 1984, p. 328)