Can risks be defined

while flying blind?

Performing audit risk assessments under environmental uncertainty; a

qualitative study using COVID-19 as an empirical example

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Accounting NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Linnea Klasson & Lovisa Knutsson TUTOR: Timur Uman

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Can risks be defined while flying blind? Authors: Linnea Klasson & Lovisa Knutsson Tutor: Timur Uman

Date: 2021-05-24

Abstract

Background & Problem: Risk assessment is a central part of the audit process. Previous

audit failures have increased the importance further. Several suggested determinants of risk assessments have been explored within literature. However, literature has not up until now explored what reflection environmental uncertainty has on the risk assessment process. Due to the ongoing pandemic, COVID-19, the opportunity to explore the reflection of uncertainty has been made feasible.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore how societal challenges reflect on auditors’

risk assessments of entities. The thesis is conducted using COVID-19 as an event signifying societal challenge.

Methodology: This thesis uses an exploratory and abductive research approach. With a

qualitative strategy, empirical data has been collected through semi-structured interviews with authorized auditors as participants.

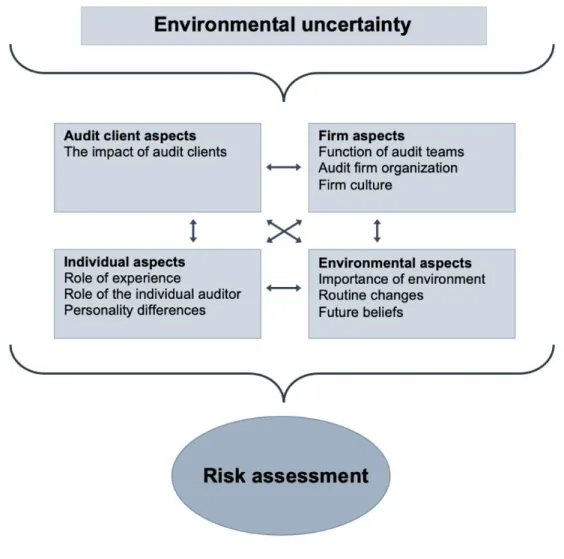

Findings: Our findings conclude that the four aspects being firm, environment, individual,

and audit client together form the risk assessment. In contrast to literature, the audit client aspect was argued as more important. Further, environmental uncertainty is reflected in risk assessments through these four aspects and can affect each aspect individually in various ways.

Future research: Since this study explores reflections of a crisis, while it is still present, we

would find it interesting to examine its aftermath. In line with previous literature and our empirical findings, we foremost would suggest future researchers to explore the impact of a societal challenge on audit quality and whether differences are present concerning audit firm size.

Keywords: Audit, risk assessment, COVID-19, environmental uncertainty, individual

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we would like to thank our tutor Timur Uman for all the guidance and feedback we have received in the process of writing this thesis. Without his engagement, this would not have been possible.

Secondly, we thank all participants in our study for taking their time to provide us with valuable information. Without you, our study would not have been as exciting.

Thirdly, we thank our supportive friends on the fourth floor. Take away laughs and fika, the process of writing this thesis would not have been even half the enjoyment.

Finally, we want to thank each other for always being supportive and willing to brainstorm even the worst of ideas.

Thank you!

Jönköping, May 2021

______________________ ______________________

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Problematization 5 1.3 Purpose 10 1.4 Research question 10 2. Institutionalia 112.1 The regulatory frameworks to follow as an auditor 11

2.2 Generally accepted auditing standards 12

2.3 International Standards on Auditing (ISA) 12

2.3.1 ISA 200 12 2.3.2 ISA 300 12 2.3.3 ISA 315 13 2.3.4 ISA 330 13 2.4 Summary of ISA 13 3. Literature review 15 3.1 Environmental uncertainty 15 3.2 Risk assessment 17 3.2.1 Risk management 17

3.2.2. Audit risk assessment 18

3.2.3 Risk management under uncertainty 20

3.3 Individual aspects 21 3.3.1 Professional judgement 21 3.3.2 Professional scepticism 23 3.3.3 Professional experience 26 3.4 Organizational aspects 28 3.4.1 Professional organizations 28 3.4.2 Partnership structure 30

3.4.3 Big 4 versus non-Big 4 31

3.4.4 Audit teams 34

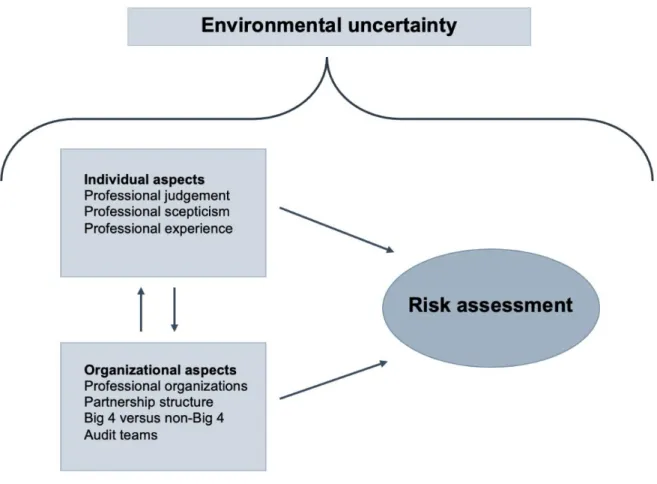

3.5 Integrative model 36

3.6 Research framework 39

4. Method 41

4.1 Research philosophy 41

4.2 Research design and method 42

4.3 Research approach 42

4.4 Research strategy 44

4.5 Literature review and choice of sources 45

4.6 Choice of theory 46

4.7 Data collection 47

4.7.1 Sampling technique 47

4.7.2 Conducting the interviews 49

4.7.3 Operationalization of interviews 49

4.7.3.2 Theme 2: Individual aspects 50

4.7.3.3 Theme 3: Organizational aspects 50

4.7.3.4 Theme 4: Environmental aspects 51

4.7.4 Data processing of interviews 51

4.8 Research quality 53

4.8.1 Credibility 53

4.8.2 Transferability 54

4.8.3 Dependability 54

4.8.4 Confirmability 54

4.9 Ethical research considerations 55

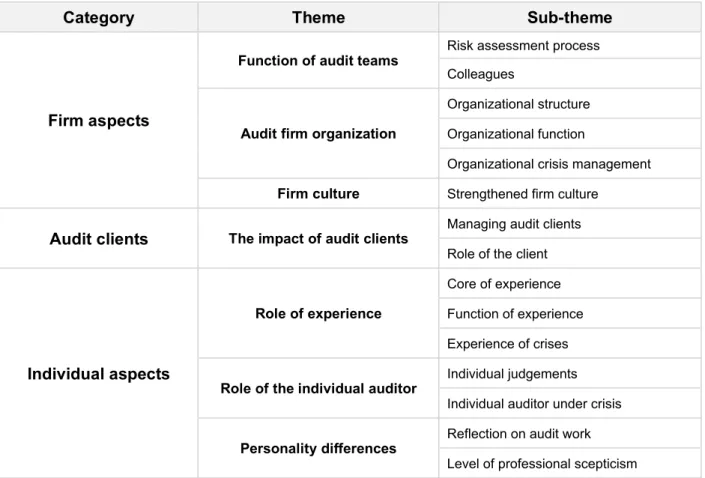

5. Empirical results and analysis 57

5.1 Firm aspects 57

5.1.1 Function of audit teams 57

5.1.1.1 Risk assessment process 57

5.1.1.2 Colleagues 58

5.1.2 Audit firm organization 60

5.1.2.1 Organizational structure 60

5.1.2.2 Organizational function 63

5.1.2.3 Organizational crisis management 64

5.1.3 Firm culture 66

5.1.3.1 Strengthened firm culture 66

5.2 Audit client aspects 68

5.2.1 The impact of audit clients 68

5.2.1.1 Managing audit clients 68

5.2.1.2 Role of client 70 5.3 Individual aspects 71 5.3.1 Role of experience 72 5.3.1.1 Core of experience 72 5.3.1.2 Function of experience 72 5.3.1.3 Experience of crises 74

5.3.2 Role of the individual auditor 75

5.3.2.1 Individual judgements 75

5.3.2.2 Individual auditor under crisis 77

5.3.3 Personality differences 78

5.3.3.1 Reflection on audit work 78

5.3.3.2 Level of professional scepticism 80

5.4 Environmental aspects 82

5.4.1 Importance of environment 82

5.4.1.1 Most prominent environmental factors 82

5.4.1.2 The impact and management 85

5.4.2 Routine changes 86

5.4.2.1 Working digitally 86

5.4.2.2 Specific focus 88

5.4.2.3 Working closer 91

5.4.2.4 Role of the auditor 93

5.4.3 Future beliefs 95

5.4.3.1 Future changes in the audit 95

5.4.3.2 Future risk assessments 97

5.5 Empirical framework 98

5.5.1 Updated research framework 100

6. Discussion and conclusion 101

6.2 Empirical contributions 104

6.3 Practical contributions 106

6.4 Societal implications 107

6.5 Limitations and reflections 108

6.6 Future research 109 7. References 111 8. Appendix 122 8.1 Request letter 122 8.2 Interview guide 123 8.3 Consent form 124

Definitions

IAASB International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board

IFAC International Federation of Accountants

ISA International Standards on Auditing

GAAS Generally Accepted Auditing Standards

Going concern “The entity will continue its operations for the foreseeable future” (ISA 570)

Revisorslag (SFS 2001:883) is translated to Swedish Public Accountants Act Aktiebolagslagen (SFS 2005:551) is translated to Swedish Companies Act

The following list presents the audit firms that in this study are referred to as the Big 4. Other firms are referred to as the non-Big 4 firms.

◦ Deloitte

◦ PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) ◦ Ernst & Young (EY)

1. Introduction

The introduction will start by presenting a background to the importance of auditors and the challenges of the profession. Foremost the most central concept of this thesis, namely risk, will be introduced, focusing on its importance in the audit process. Further, suggested factors influencing risk assessment are presented, pointing out gaps in the literature. From this, the purpose and research question are developed and presented.

1.1 Background

The ideal auditor operates as an essential function within an economic system, performing independent, critical, and professional judgements. Auditors are vital to maintain a continuing and flourish of free-financial markets globally (Duska, 2005). This since the audit profession is a crucial market actor creating trust within markets so that banks, investors, shareholders, customers, and employees, among several others, can make sound decisions based on the financial reports (Andersson, Eriksson, Forssmark & Pyk Hammarqvist, 2019). Society has to believe in the purpose of the profession, otherwise the value of the auditor’s opinion will be zero (DeAngelo, 1981). Hence, the responsibility of the profession is in the public interest and not exclusively to satisfy the needs of a single client (IFAC, 2018). This is usually what characterizes a profession, having a specific possession of skills and knowledge as well as a special attitude, concern, and commitment to work (Freidson, 1984; Moore, 1987). This commitment is an aim for a higher purpose since professionalism relies on their work to be of critical importance to the good, either for the public at large or to a specific important elite (Freidson, 1984; Freidson, 1999).

Because of the central and important role of an auditor within society, the demands on competence are high and regulated closely (Johansson, 2018). The development of the profession is closely tied to its regulation and today a large mass of rules and regulatory guidelines are present (Öhman & Wallerstedt, 2012). The framework that an auditor operates within is regulated on a global level by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), issuing International Standards on Auditing (ISA) (IAASB, 2021). These standards are guidelines for how to audit a client properly (IAASB, 2020). It is the auditor’s job to understand the information processed by a firm and to judge whether or not the information is communicated properly (Duska, 2005). From this, the auditor should then be able to report on the reliability of the annual report, the accounting behind it, and its

management (FAR, 2005). Thus, the responsibility of the auditor is to issue an opinion on whether a financial statement is a fair representation of a firm’s financial position (Duska, 2005).

To issue this opinion as an auditor is not always an easy task; constant changes impact the surrounding audit environment as well as the clients and the regulatory directives (Johansson, 2018). The reporting field has expanded with an increased amount of non-financial information in the form of sustainability reports and more informative annual reports (Murphy & Hogan, 2016). In addition, increased demand from society and media constantly pushes for tightened regulation and improvement in the performance of audits (Halling, 2018). More recently, the greatest factors driving change have been commercialism and globalization, forcing the profession into a more business-driven direction (Spence & Carter, 2014). Altogether, the audit profession is constantly under development and is pushed to change in line with environmental, organizational, and regulatory developments and requirements continuously (Karapetrovic & Willborn, 2000; Murphy & Hogan, 2016; Spence & Carter, 2014).

In particular, audit crises have urged increased regulation (Öhman & Wallerstedt, 2012). The global financial crisis provided interesting insights into the audit profession. Attention was drawn to its limited capabilities and the need to reform practice and regulation (Humphrey, Loft & Woods, 2009). The fact that several banks received clean audit reports immediately before experiencing enormous financial difficulties did not portray the audit profession positively (Spence & Carter, 2014). However, before the financial crisis, there was an even greater scandal shaking the auditing profession (Chaney & Philipich, 2002; Li, 2010). Accounting fraud and creative earnings management in the Enron corporation led to one of the largest bankruptcies in American history (Li, 2010). In fact, it was described as the biggest audit failure ever seen. With the downfall of Enron, it brought the responsible audit firm Arthur Andersen with it, being one of the biggest audit firms at the time (Li, 2010; Chaney & Philipich, 2002). As a result, the entire profession of auditors, their industry, and purpose were questioned (Li, 2010; Linthicum, Reitenga & Sanchez, 2010; Nelson, Price & Rountree, 2008). It is therefore in the highest interest of auditors to be able to adapt to environmental challenges and events, such as financial crises. It is also of importance to professionally uncover untruthful, fraudulent organizations, as the Enron corporation (Da Silveira, 2013; Carpenter, 2007; Nelson et al., 2008). Hence, detecting fraud and assessing risks correctly as an auditor is argued to be the most prior mission for the profession (Carpenter, 2007; Da Silveira, 2013).

Because of this prior mission, the audit process is largely built on risk assessments 1 (Fukukawa & Mock, 2011; Gray & Manson, 2005). Being a continuous process, auditing involves identifying and assessing risks, planning audit procedures, gathering and evaluating evidence, and further reviewing risk assessments and audit plans to collect more evidence if needed (Bedard & Graham, 2002; Fukukawa & Mock, 2011). The risk identification within the audit determines the efficiency of the entire process since it is the main way of effectively identifying material errors (Bedard & Graham, 2002; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990). This risk estimate will foremost help the auditors to identify the areas of importance and by this know what is essential to focus on (Humphrey & Moizer, 1990). Given that time and resources are limited, it is of the highest importance to keep the audit procedure efficient, as well as cost-effective (FAR, 2005; IAASB, 2020). Reducing risks to an acceptable or tolerable satisfactory level is therefore, the aim of the risk assessment (Main, 2004). Because of this risk-oriented practice, if failing to assess client risk properly, the whole process is in danger and the conclusions drawn might be inaccurate (Fukukawa & Mock, 2011). Correspondingly, the quality of the audit process is profoundly dependent on the auditor’s ability to minimize audit risks (Bedard, Mock & Wright, 1999; Hogan & Wilkins, 2008).

The in-charge auditor, commonly being an authorized auditor, is usually responsible for conducting the risk assessment where the information and estimates in turn are communicated to the rest of the engagement team. Even if risk levels are computed in the planning stage, these need to be revised throughout the entire audit process and if new evidence is proving the need for adjustments. However, auditors usually establish a certain belief regarding the risks. Hence, the auditors are unlikely to change their beliefs despite new information obtained, and as a result, the risk assessment will not be changed either (Vinten, Payne & Ramsay, 2005). Also, to assure the appropriateness of an audit plan, large references are usually drawn to the audit in the previous year. Some auditors even express that last year’s audit will be the main starting point of a new audit plan, and that the audit plans might even be identical (Humphrey & Moizer, 1990). Thus, an anchoring bias is usually present based on the auditor’s previous audit, belief, and information about a client (Vinten et al., 2005).

When preparing the audit plan there are situations and specific areas that, under regulatory guidelines, entail higher risk exposure than others (FAR, 2020). Especially caution to statements around going concern, the audit of future information, and management’s estimates and judgements are particularly important (FAR, 2020). However, several additional areas and situations are essential for the risk assessment of a client (Allen, Hermanson, Kozloski & Ramsay, 2006). A broader focus on the overall organization is emphasized, including its key processes and environment, extending the focus from only the financial statements. Hence, a convenient risk assessment needs to entail all possible influences an organization might face, focusing on the internal as well as the external environment of a client (Allen et al., 2006). When failing to detect risk as an individual auditor or an auditing firm, the consequences are usually directed towards the profession with reputational losses (Bik & Hooghiemstra, 2018; Hussin, Iskandar, Saleh & Jaffar, 2017). It could also result in costly litigation for the firms as well as for the auditor (Bik & Hooghiemstra, 2018). The inability to assess risk correctly is a serious concern, given that incidents missed usually uncover after financial statements are audited (Hussin et al., 2017). Apart from the Enron collapse, an additional scandal having an impact on the audit industry is the fraudulent history of WorldCom. The company, which acted in the telecommunication industry, overstated revenues and misclassified costs as expenditures. Thus, both income, as well as the level of assets, were increased (Cernusca, 2007; Lyke & Jickling, 2002). This was a result of an overly optimistic view of the internet growth, which at the time was drastically emerging. However, how and in what way the industry would develop was uncertain (Lyke & Jickling, 2002). When the truth of the fraud unraveled, the critique towards the responsible auditor was large. Critics meant that the audit should have been designed to capture the large misclassifications. But foremost, it should have taken the uncertainty within the industry at the time into account, which signalled an increased risk for possible fraudulent accounting policies (Cernusca, 2007; Lyke & Jickling, 2002).

With previous failures, damaging the reputation of the audit profession, it has become more important to make the audit process more efficient through appropriate planning decisions and precise risk-oriented actions (Chaney & Philipich, 2002; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Hussin et al., 2017). The WorldCom scandal exemplified that the risk assessment needs to entail and capture more than only the organization that is being audited, putting the focus on the contextual aspects in which a client operates and the risk within a specific industry or society (Cernusca, 2007; Lyke & Jickling, 2002). Regulation has come to place and has been adapted

accordingly, acting as the structure for risk assessment that is similar for all auditors (IAASB, 2021; Johansson, 2018; Öhman & Wallerstedt, 2012). However, the interpretations of regulation and the judgements of auditors are usually different (Knechel, 2016). Thus, it is relevant to explore the incentives and determinants of risk assessment and its constitution.

1.2 Problematization

Focusing on the incentives and determinants of audit risk assessment, several factors of importance have been explored and identified by literature (e.g., Cahan & Sun, 2015; Chiș & Achim, 2014; Hussin et al., 2017; Lawrence, Minutti-Meza & Zhang, 2011; Low, 2004; Nolder & Kadous, 2018; Vinten et al., 2005). Regulation emphasizes that to perform an audit process that entails enough appropriate evidence and controlled risks, the auditor needs to plan and perform the process using professional knowledge and other traits. Hence, the individual auditor and the performed judgements are of great importance (IAASB, 2020). In line with this, several researchers have argued for a relationship between the individual traits of the auditor and its reflection in risk assessment (e.g., Bik & Hooghiemstra, 2018; Cianci & Bierstaker, 2009; Guénin-Paracini, Malsch & Paillé, 2014; O’Donnell & Prather-Kinsey, 2010). Foremost the core concepts, being professional judgement and professional scepticism, in relation to risk assessment have been explored and argued to be of high importance (e.g., Chiș & Achim, 2014; Grout, Jewitt, Pong & Whittington, 1994; Hussin et al., 2017; Vinten et al., 2005). This importance is suggested by literature, built upon assumptions drawn primarily from profession theory and behavioural theory, explaining the action of auditors (eg., Freidson, 1984; Moore, 1987; Skinner, 1985)

Focusing on professional scepticism, research suggests that a lack of scepticism commonly is the cause for audit deficiencies and consequent audit failure (Nolder & Kadous, 2018). Professional scepticism is therefore displayed as essential to perform a high-quality audit that entails a proper risk assessment (Vinten et al., 2005). The literature emphasizes the importance of professional scepticism and how it should be exercised continuously throughout the whole audit process (Hussin et al., 2017). The same indications are present for professional judgement as well, with literature expressing its importance in relation to the audit process and foremost the planning stages with the connected risk assessment. Building on professional training, knowledge, and experience, the judgement calls of the auditors are proven to have a direct effect on audit quality and whether risks are correctly addressed (Chiș & Achim, 2014).

In line with the research, literature on profession theory states that the authority of a profession is justified by its professional judgement calls (Freidson, 1984; Moore, 1987). Therefore, exercising professional judgement and scepticism, especially during uncertain situations, legitimizes the existence of professions (Brante, 1988). For auditors and audit firms, professional judgement is fundamental when assessing and considering the levels of materiality, the risks, and the planned activities in an audit (IAASB, 2020). The purpose of having professionals trained with specific skills and knowledge is, according to profession theory, essential to have the abilities to exercise professional judgement on complex issues and problems (Freidson, 1984; Grout et al., 1994; Moore, 1987).

Furthermore, experience is part of both the central concepts of professional judgement and professional scepticism and is in literature displayed as an additional determinator to risk assessment (Hussin et al., 2017; Mock & Wright, 1993). Several researchers have argued for a relationship between the individual auditor’s experience and the performed audit risk judgements (e.g., Cahan & Sun, 2015; Hussin et al., 2017; Low, 2004). Greater knowledge and developed structures entailed by experienced auditors are demonstrated to lead to more accurate risk assessment (Cahan & Sun, 2015; Low, 2004). Moreover, the experience of professionals is presented as an important factor for handling stressful and uncertain situations successfully. Additionally, lower stress levels are displayed as a result of greater experience (Arora, Sevdalis, Nestel, Woloshynowych, Darzi & Kneebone, 2010). Literature has, on the other hand though, expressed how auditor experience tends to establish a predetermined belief from previous audits and engagements with a client. In turn, this could bias the professionalism and make the auditor sightless for new information, missing important aspects for the risk judgements (Vinten et al., 2005). Therefore, one can conclude that during a stable and continuous audit environment, greater experience will foremost lead to more accurate risk assessments, but during times of uncertainty and changing conditions it could make the auditor less responsive or adaptive but at the same time more stress-resistant.

The reflection of individual auditor traits in audit risk assessment is exemplified both by regulation and literature (e.g., Chiș & Achim, 2014; Grout et al., 1994; Hussin et al., 2017; IAASB, 2020; Vinten et al., 2005). Additionally, the literature emphasizes the importance of organizational structure as an additional determinant of audit risk assessment, suggesting that elements of an audit firm, in which the auditor is employed, are of high value (Hussin et al., 2017; Quadackers, Groot & Wright, 2014). In line with institutional theory, organizations act

as a specific institution with their own settings built on norms and practices (Dacin, Goodstein & Scott., 2002; Scott, 1987). Professional organizations are usually characterized by hierarchy, developing an efficient process of work that keeps a high level of monitoring and controlling (Diefenbach & Sillince, 2011). Audit firms are often structured as partnerships, where managers as well are owners. Altogether, this structure of work is argued to be superior for professional work with high knowledge intensity (Greenwood & Empson, 2003). However, during unstable environmental conditions, it is displayed as a dangerous setting unable to react or adapt in a sufficient way (Jeppesen, 2007). Additionally, audit firms, as well as individuals, behave and act non-similarly, in line with both institutional- and behavioural theory (Dacin et al., 2002; Skinner, 1985). Thus, firms tend to differ because of their management entailing people with different driving forces, history, competence, and motives (Adrian, 2014). The working environment is therefore displayed as being reflected in the efficiency in risk assessment, both positively and negatively (Quadackers et al., 2014). This since the environment will influence the behaviour of an individual, which in turn will be reflected on their performance (Hussin et al., 2017).

Within the organizational reflections in risk assessment, one aspect has emerged from the limitations of assessing risks alone (Carpenter, 2007). As a consequence, the importance of team risk assessments has been examined and promoted by literature (Carpenter, 2007; Hoffman & Zimbelman, 2009). The benefits of using audit teams are argued to be several, with foremost the improvement of audit planning decisions and more creative ideas brought up (Hoffman & Zimbelman, 2009). The team aspect is also encouraged by regulation, indicating that the right team composition is of the highest essence for the audit process and its outcome (ISA 300). This since a fit between client needs and staff competence will increase the quality of the final audit (Udeh, 2015). Furthermore, literature has examined the organizational structures of the Big 4 audit firms compared to non-Big 4 and its influence on the audit process (Lawrence et al., 2011). Literature usually concludes that Big 4 auditors are superior to non-Big 4 when comparing audit quality, indicating a superiority within risk assessments (Becker, DeFond, Jiambalvo & Subramanyam, 1998; Behn, Choi & Kang, 2008; DeAngelo, 1981; Palmrose, 1988; Khurana and Raman, 2004).

Irrespective of what is more true regarding performance, firm size is by literature displayed as an important factor in audit risk assessment. Differences in cultural dimensions and local professional behaviour will be reflected in the implementation of audits in all firms and teams

(Bik & Hooghiemstra, 2018). This signals that contextual aspects surrounding audit firms are of importance, independent of size. Despite this, the literature covering influences on audit risk assessment has not yet controlled for, or discussed, possible reflections of societal challenging aspects (e.g., Hussin et al., 2017; Lawrence et al., 2011; Nolder & Kadous, 2018). From profession theory, it is emphasized how the judgement calls and exercising knowledge, especially during uncertain and complex situations, is what legitimizes a profession (Brante, 1988). Hence, it is reasonable to inspect professions from this perspective, having them legitimizing their existence. Also, there are suggestions that the factors deriving audit risk assessment, known by literature, are constant during a stable and continuous environment (e.g., Arora et al., 2010; Cahan & Sun, 2015; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Low, 2004; Vinten et al., 2005). However, in times of uncertainty and changing settings, these reflections might be different or behave differently.

This can be further argued for since uncertain and complex contexts, as societal challenges, in literature have been suggested to push for behavioural changes in multiple professions. For instance, stressful and complex situations are related to ineffectiveness and withdrawal behaviour, resulting in lowered performance (Jamal, 1984). Foremost, increased stress can result in a higher level of improvised work (Konow Lund & Olsson, 2016). Focusing specifically on the audit profession and relying on the theory of professions (e.g., Freidson, 1984; Moore, 1987), several researchers have explored the impact that stress and pressure have on the audit process. Foremost, the concept of time budget pressure within auditing has been examined, where results indicate that this pressure will decrease the ability of auditors to fully exercise judgement and scepticism. As a result, it will impact the auditor to stress the risk assessment and negatively disturb the audit effectiveness (Hussin et al., 2017). Looking at audit effectiveness and audit quality overall, it is suggested to be reduced when auditors are put under increased pressure (Elder & Allen, 2003; McDaniel, 1990). Particularly, the processing accuracy and the sampling adequacy decline when the level of stress increases (McDaniel, 1990). Hence, lower performance levels and effectiveness together with increased levels of improvisation could be the result when operating during uncertain, complex, or stressful situations (Jamal, 1984; Konow Lund & Olsson, 2016).

During societal crises, people will behave differently compared to how they do under stable circumstances (King & Carberry, 2020) and will, in accordance with behavioural theory, form new traits derived from environmental factors (e.g., Skinner, 1985; Watson, 1925). In times of

such environmental uncertainty, one can assume that high levels of stress and pressure are present and reflected in professions. Looking specifically at the audit profession, it is argued that amidst a crisis, the raw edges of audit practice are the most apparent (Humphrey et al., 2009). Hence, this indicates that the profession during a crisis will move closer to its foundation and intended purpose, leaning towards the main pillars of audit practice. Furthermore, during uncertain times, the estimation of probabilities has been shown to be more conservative with extensive information seeking (Leblebici & Salancik, 1981). Therefore, auditors tend to demand a higher level of evidential support trying to create more comfort in their judgement calls (Rowe, 2013). This is demonstrated by auditors including outside competencies with specific knowledge, trying to decrease any large uncertainty present (Jenkins, Negangard & Oler, 2018).

A societal crisis could henceforth have the power to impact a profession and one can again question whether the influences previously known to be related to risk assessment are continuous even during circumstances of challenge and uncertainty. Historically, both the financial crisis and the Enron collapse are two different examples of challenges that pushed and challenged the audit profession to change and adapt but also to work under uncertainty (Humphrey et al., 2009; Li, 2010). Both these situations led to regulatory changes but foremost increased attention to the risk assessments within audit (Da Silveira, 2013; Li, 2010; Nelson et al., 2008).

Today, a new crisis is present causing great environmental uncertainty. In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) categorized COVID-19 as an international public health emergency. With many restrictions and policies introduced by governments around the world, COVID-19 has put all economies and industries, including auditors, to test once again (Argento, Kaarbøe & Vakkuri, 2020; Mårder, 2020). The pandemic will have a long-term effect on societies, and in the short term, regulations and quick adaptations have to be made, possibly causing institutional changes (Argento et al., 2020; Dacin et al., 2002; Scott, 1987). In the audit profession, the pandemic could challenge both the risk estimations specifically as well as the whole profession further, possibly reshaping the audit to fit new circumstances (Hadjipetri Glantz, 2020). Acting as a societal challenge, COVID-19 is an interesting empirical phenomenon where the level of uncertainty and complexity is high since no one can tell when the crisis will end, or what the outcome will be (Baker, Bloom, Davis & Terry, 2020). The

pandemic entails increased risks and going concern issues are becoming more prominent (Hadjipetri Glantz, 2020).

In addition, the crisis has brought new tasks to the audit profession, with increasing digitalization and temporary regulatory changes, such as conversion aids and tax relieves (Mårder, 2020). Annika Engström, who is the Chairman of the Quality Committee for Auditing at FAR, stated that “Because of COVID-19, auditors need to rethink and expand their risk assessments” (Hadjipetri Glantz, 2020). Thenceforth, previously known factors deriving risk assessment can come to be changed or restructured. Hence, now more than ever, it is time to examine how societal contexts reflect on the audit profession. This by using the crisis of COVID-19 as an event signifying societal challenge, focusing on whether societal aspects could be associated with the risk assessment of auditors.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to explore how societal challenges reflect on the risk assessment of auditors. Building on the reflections seen on other professions as well as in the audit profession, under uncertain and stressful situations, we believe that these aspects play a larger role than what literature has, up until now, suggested. The thesis is conducted using the COVID-19 pandemic as an event signifying societal challenge.

1.4 Research question

2. Institutionalia

In the upcoming chapter, the guidelines, principles, and norms that an auditor needs to follow will be presented more in detail. Foremost, the chapter will focus on the regulation and recommendations that are mandatory to serve as an auditor in Sweden. The most relevant regulatory standards are presented, and a summarizing table is presented at the end.

2.1 The regulatory frameworks to follow as an auditor

Each individual audit engagement has to be tailored to fit its client, making every audit unique. However, there are standards, norms, and recommendations that need to be followed regardless of who the client is. In Sweden, the course of action for an audit is defined in the framework by FAR, describing how the audit process should be conducted (FAR, 2020). The base in each audit is ISA, which is an international framework for auditors. The international framework is in turn complemented with national standards that in Sweden refer to the Swedish Public Accountants Act (SFS 2001:883) and professional audit recommendations issued by FAR (FAR, 2020). The ISA are set by the IAASB which is an independent organization serving the public by issuing standards and proposing suggestions for the improvement of the audit profession (IAASB, 2021). It is also an independent committee serving the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) (IAASB, 2021).

Additionally, FAR is a professional organization within auditing and accounting in Sweden that issues statements and recommendations on how to interpret different laws and regulations from their professional perspective. The organization is constituted by members of authorized professionals, specialists, and companies operating within the industry. The mission of FAR is to demonstrate what constitutes professional ethics for accountants and to distribute relevant current information and knowledge through educational facilities and guiding services. The organization also cooperates with international and global representatives, such as IFAC and IAASB, in the development of rules and frameworks within the industry. Additionally, FAR has the authority to authorize accounting, tax, and payroll consultants. The authorization of auditors is instead done by the Swedish organization of Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors. (FAR, n.d.).

2.2 Generally accepted auditing standards

A central concept in Sweden is Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS), which refers to how to perform the audit process (FAR, 2005). GAAS are in Sweden defined in multiple laws, including the Public Accountants Act (SFS 2001:883) and Swedish Companies Act (SFS 2005:551). The concept entails knowledge, experience, and professional judgement and is developed internationally, through Swedish auditing organizations, and by custom and practice (FAR, 2005). Swedish law demands that the audit should be performed with professional scepticism and be as detailed as the Swedish GAAS demands. Additionally, the auditor also needs to follow rules of professional ethics for accountants, entailing ethical norms and regulations that control the professional responsibility (FAR, 2005).

2.3 International Standards on Auditing (ISA)

The framework of ISA entails the goals, demands, relevant applications, and clarifications within an audit and is aimed to support the auditor. The framework entails all steps within an audit engagement from the initial planning phase to the performance and lastly the completing part, and all the areas touched within. The ISA framework should be used consistently throughout all performed audits, whether the company is large or small, and independent of its industry. (FAR, 2020).

2.3.1 ISA 200 “Overall objectives of the independent auditor and the conduct of an audit in

accordance with international standards on auditing”

ISA 200 deals with the responsibilities of an auditor, explaining the objectives that should be met. This entails the responsibility to always follow ISA and the responsibility the profession has towards users of financial statements. When conducting an audit, the overall objective should be to obtain enough reasonable assurance that the financial statements are free from material misstatements and hence be able to issue an opinion about this. To do this, the auditor should act independently and follow all relevant professional ethical demands. Additionally, the auditor needs to collect enough audit evidence, reducing the audit risk. (ISA 200).

2.3.2 ISA 300 “Planning an audit of financial statements”

The objective of ISA 300 is to determine how an audit should be planned for it to be performed effectively. Planning is supposed to help the auditor to solve and put attention to the right issues, to organize and select the appropriate team members and the right competence, and to know when specialists are needed. The extent of planning will vary according to the complexity

of the entity and the previous knowledge and experience with the entity. Specific attention should be put to changes in circumstances occurring during the audit engagement. As a result of unexpected events or changes of conditions, it might be necessary to modify the strategy and audit plan and the connected activities and procedures with consideration to the assessed risk. (ISA 300).

2.3.3 ISA 315 “Identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatement through

understanding the entity and its environment”

Identifying and assessing the risks of an entity is the main objective of ISA 315. This risk assessment procedure includes inquiries of management, analytical procedures, and inspection and observation. Foremost, a client’s environment, its industry, and strategies are important for the assessment of risks. However, all areas of risk should be accounted for. If the information obtained from previous client experience is to be used, the auditor needs to determine whether changes have occurred that could affect the relevance of the information. The initial assessment of risks might change during the audit, alongside new audit evidence or new information. Thus, revising and modifying the planned audit procedures accordingly. Altogether, several conditions and events might indicate a risk of material misstatements. Foremost, operations in regions that are economically unstable, and operations exposed to volatile markets, are of interest. Also, going concern and liquidity issues are conditions and events that might impose a risk of significance. (ISA 315).

2.3.4 ISA 330 “The auditor’s responses to assessed risks”

ISA 330 explains how risks should be managed by an auditor. An auditor is responsible to design and execute responses to the risks which are assessed in accordance with ISA 315. In the response, the auditor should consider the basis for the given risk assessment. The higher the risk is, the more powerful audit evidence needs to be collected. In the same manner, the audit evidence should be relevant to the type of risk assessed by the auditor. (ISA 330).

2.4 Summary of ISA

As mentioned above, the objective of an audit is to be able to express an opinion on whether or whether not financial statements are prepared in accordance with applicable standards and are free from material misstatements. The concept of materiality is applied by the auditor both for planning and performing the audit. In general, misstatements are considered material if expected to influence users’ economic decisions based on the financial statements. The level

of materiality set is a judgement call by the responsible auditor. To be able to express an opinion of a financial statement, enough audit evidence to the enhanced risks for material misstatements needs to be collected and looked upon by professional scepticism and judgement of the auditor. The framework of ISA entails guiding principles enabling the auditor to achieve the overall objectives of auditing. However, audit engagements might widely vary, and all specific circumstances are not anticipated in the standards. Therefore, in the end, it is the auditor’s responsibility to determine the audit procedures necessary to fulfil the requirements stated. (FAR, 2020; ISA 200)

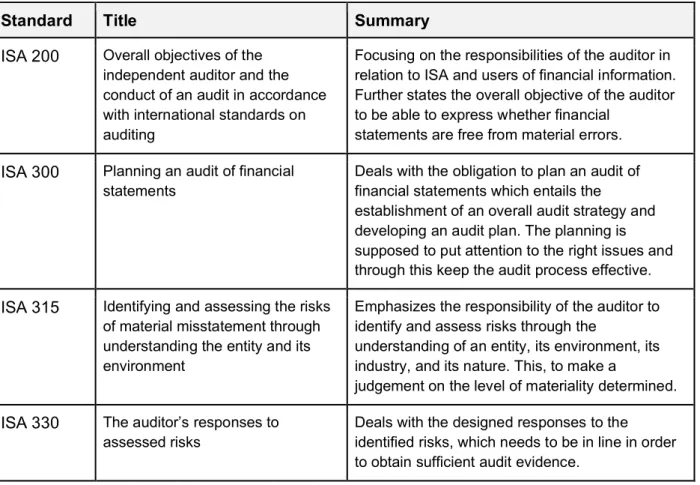

For this thesis, the importance of the auditor’s responsibilities, the initial planning stages of the audit, and foremost the risk assessments are of interest. Therefore, the ISA standards with objectives to these aspects have been described to get an understanding of the regulatory foundation. A summary of these applicable standards is presented below (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the ISA standards

Standard Title Summary

ISA 200 Overall objectives of the independent auditor and the conduct of an audit in accordance with international standards on auditing

Focusing on the responsibilities of the auditor in relation to ISA and users of financial information. Further states the overall objective of the auditor to be able to express whether financial

statements are free from material errors. ISA 300 Planning an audit of financial

statements

Deals with the obligation to plan an audit of financial statements which entails the

establishment of an overall audit strategy and developing an audit plan. The planning is supposed to put attention to the right issues and through this keep the audit process effective. ISA 315 Identifying and assessing the risks

of material misstatement through understanding the entity and its environment

Emphasizes the responsibility of the auditor to identify and assess risks through the

understanding of an entity, its environment, its industry, and its nature. This, to make a

judgement on the level of materiality determined. ISA 330 The auditor’s responses to

assessed risks

Deals with the designed responses to the identified risks, which needs to be in line in order to obtain sufficient audit evidence.

3. Literature review

The literature review will provide a deeper understanding of previous research on risk assessment and its suggested determinants. It will start by presenting the research on environmental uncertainty and its importance for professionals and organizations. Connections to relevant theories are constantly made throughout the entire chapter in order to understand the relations drawn by literature. In the end, the resulting integrative model is described in detail followed by a research framework.

3.1 Environmental uncertainty

Environmental uncertainty can be described as a set of conditions to which an individual perceives and reacts, and thereafter concludes uncertainty. Attributes in the environment need to be structured by an individual to describe uncertainty, and hence, conditions alone are not enough to illustrate this (Downey, Hellriegel & Slocum, 1975). Further, uncertainty is defined as times when a decision-making situation is affected by a lack of information regarding important environmental factors. Thus, the outcome of a specific decision will be unknown and therefore it is not possible to assign probabilities regarding success or failure (Duncan, 1972). Due to changes in the environment causing uncertainty, firms have to adapt to keep control over their operations. Therefore, foresight practices are usually essential for strategic planning in a highly dynamic context (Vecchiato, 2012). It is fundamental to be aware of all forthcomings in order to deal with the possible outcomes. One way of dealing with uncertainty is by scenario planning, where potential outcomes are rehearsed. This prepares an individual mentally of where different decisions could possibly lead (Johnston, Gilmore & Carson, 2008). Within institutional theory, the features of environments are receiving steadily increasing attention. This since it is argued to be the most important determinants for the structure and functioning of societies and organizations at large. Earlier, organizations were portrayed as production and exchange systems with structures shaped by transactions and technologies. The environment was viewed as a source of information, providing resources and exchange partners. However, the connection between organizations and the environment was not fully established. Institutional theory puts attention to the existence of organizations within institutional environments and that these are multiple and enormously diverse and will vary over time being uncertain in their nature. Therefore, the importance, power and presence of this factor should not be overlooked. (Scott, 1987).

Bringing environmental uncertainty, crises are commonly seen as situations that could threaten an organization’s reputation, business, image, and relations. However, a more modern view is to display crises as a natural stage in the ongoing development and evolution and henceforth part of an organization’s learning processes (Falkheimer & Heide, 2006). Either way, a crisis is a factor for institutional change and advancement. Research on institutional change emphasizes that pressure from a societal change or crisis not only in itself will push for changing institutionalised settings, it is also the interpretation and meaning by the involved actors within organizations that legitimizes a change or not. This response by the involved actors is usually built on the existing institutional norms and practices. Therefore, the resulting change is often a hybrid of new and old elements of the institution (Dacin et al., 2002). However, whether institutional change will occur or not is dependent on the current knowledge and capacity within an organization. Foremost, the ability of the actors involved to understand and adapt to changes occurring and transfer this onto habits, behaviour, and norms will determine the time rate of institutional change (Bush, 1987).

The impact a crisis could have on societies, individuals, and organizations is drastic. This can be illustrated by the financial crisis and its disruptive change and uncertainty. During this crisis, individuals were affected both on a personal as well as on a societal level. However, countries with better structured social protection were able to handle the situation more effectively compared to countries less prepared and with low financial reserves. Thus, active labour-market programmes and other social support services were shown to have a good influence on population health. Hence, even during large uncertainty, as a financial crisis entails, some are less troubled than others implying that preparation can be beneficial (Karanikolos, Mladovsky, Cylus, Thomson, Basu, Stuckler, Mackenbach & McKee, 2013). A societal challenge can therefore indeed be a possibility of learning; both learning how to deal with current challenges and how to prepare for future dilemmas. However, it is a challenge in itself to be able to gain valuable knowledge from these situations. Lack of relevant experience can be a driver of applying old solutions to new problems, instead of finding new paths. Not investigating new solutions will lead to individuals not engaging in new investigative contexts and hence, the number of learning outcomes will be low (Moynihan, 2008). Without new solutions and learning outcomes, institutional change will take time (Bush, 1987). Moreover, defensive behaviour leading to a denial of the problems as well as a narrowed focus makes learning and adapting harder. But if challenges can be conquered, the solutions will lead to new insights and

possibly also changes in the prescribed patterns and settings of the institution (Bush, 1987; Moynihan, 2008).

As a result, previous crises are an important source of knowledge regarding behaviour and crisis management. However, even if previous knowledge is a good starting point, earlier solutions can be risky to apply in new situations if the conditions of the crises are not entirely similar. Hence, it is crisis management rather than the solutions that are the most important learning outcome. Therefore, crises should not be generalized and handled through patterns seen in previous challenges, since one never could expect that a crisis ever will occur in exactly the same manner as observed before. (Moynihan, 2008).

3.2 Risk assessment 3.2.1 Risk management

Risk management is widely discussed in literature and within numerous organizational contexts (Power, 2004). The concept and procedures can be traced millenniums back, the research field, however, is still quite young (Aven, 2016). Risk management is important in various aspects and in almost every societal sector. It can put asset- and earnings quality in a new dimension and be an important factor of business strategy and in value creation (Aven, 2016; Power, 2004). Moreover, risk management is an important factor in reducing costs of financial trouble and helping companies towards an optimal capital and ownership structure (Stulz, 1996).

Despite its importance, the definition of risk is not agreed upon within risk literature and several concepts of risk are used. However, the most general perception is to define it as a probability distribution with an expected value of an event or of an uncertainty (Aven & Renn, 2009). The nature of risk is therefore a debate among risk professionals, where some argue that risk is only a social construction and not a real phenomenon while other professionals argue for the opposite. The issue is whether risks are objective probabilities of harm or if it only reflects harm for a specific group of elites or stakeholders. Different cultures will also have different mental representations of what they regard as risks, independent of the probability of harm. Hence, the risk is foremost constituted by mental models. However, the risk is as well represented by what people see and experience in real life, and the consequences observed. Henceforth, risk as a mental construct is built upon the belief that actions of humans are able to prevent harm in advance (Renn, 2008).

Risks are determined and selected by human actors, hence, what counts as a risk to someone might be an opportunity for another one (Renn, 2008). Several behavioural biases are present for each individual assessing risk. For instance, individuals might behave overconfident, exhibit loss aversion, demonstrate an experience and familiarity bias, or be driven by mood and sentiment. As a result, their decision-making and judgement of risks will be anchored or biased (Baker, Filbeck & Ricciardi, 2017). Additionally, people are bound by their rationality when faced with decisions constrained to the ability of the human mind. Hence, humans are limited in their attention, perceptions, memories, and the information processing ability. Therefore, rather than optimising, humans tend to use simplified rules and heuristics (Selten, 1990). Societies, however, have gained experience and knowledge of the impacts and effects of different scenarios, but still, one cannot anticipate all potential outcomes or consequences of an activity or event. Therefore, societies have been selective in what is worth considering and what to ignore. As a result, specialized organizations are established within different industries and societal areas to monitor the environment for hints about future issues and problems, trying to provide early warnings of potential harm (Renn, 2008).

To assess these hints, professionals commonly try to adopt a risk analysis that provides a risk profile of a specific project and all its possible outcomes (Savvides, 1994). A risk analysis can be completed by several methods. One technique is to use historical data and from this draw implications for the future. Usually, this will provide reasonable estimates that are sufficient for a good prediction of the future. However, a big problem occurs if the environment or the situation being analyzed have changed considerably. If this is the case, drawing conclusions based on historical data will most probably result in wrongful decisions. Therefore, risk analysis literature exemplifies alternative methods including probability analysis and statistical thinking. By combining risk analysis with a risk acceptance criterion, it is easier to conclude what is the unacceptable level of risk. From this, a risk analyst can tell what risk-reducing measures to use and to what extent (Aven, 2012).

3.2.2. Audit risk assessment

Risk management within auditing is essential since the audit process is largely built on risk assessments. The audit process is continuous, and the determined risk is supposed to guide the entire process towards the right direction with a proper audit plan (Fukukawa & Mock, 2011; Bedard & Graham, 2002). This risk assessment will henceforth determine the efficiency of the

audit process and its ability to identify material errors (Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Bedard & Graham, 2002). When assessing risks, auditors aim to identify the inherent-, control-, and detection risks which together form the audit risk (Gray & Manson, 2005; Hogan & Wilkins, 2008).

Inherent risk is the risk of material misstatements in the financial statement, irrespective of failures in the internal control (Gray & Manson, 2005). The risk is developed as a function of the client’s business and the environment in which they operate. Even if the risk is demanded to be assessed in every audit, literature concludes that diversity in the practice is found comparing different audit firms (Martinov & Roebuck, 1998). The social environment can have an impact on the inherent risk, where an unstable climate and uncertainty can cause problems in the daily operations of the business (Eilifsen, Knechel & Wallage, 2001). To assess the risk, the auditor has to review various factors that can have an impact on the inherent risk. Apart from the social environment in which the client operates, industry, general economy, past error history, management’s involvement in valuing accounts, and complexity are also factors of importance. Hence, auditors should determine how these factors have an impact on individual accounts. From the perspective of audit firms, determining the inherent risk is important in deciding whether the client should be retained or if it is too risky (Peters, Lewis & Dhar, 1989). Control risk is the risk of misstatements in the financial statements due to failures in or absence of relevant controls in the operation of the entity (Gray & Manson, 2005). Control risk is internal and is hence derived from the decisions made by audit client management. Thus, the appearance of these risks cannot be impacted by the auditor. They can only be assessed in order to plan the required volume of audit work (Blokdijk, 2004). Hence, the control risk is closely related to the quantity of audit evidence collected (Moraru & Dumitru, 2011). Further, control risk can be present due to problems in the social climate among the employees. Low motivation can lead to low-quality performance of important control procedures in the business (Eilifsen et al., 2001). Thus, the control risk is closely connected to the inherent risk with several factors having an impact on inherent risk also having either a direct or indirect influence on the control risk (Messier & Austen, 2000).

Lastly, the risk of an auditor failing to identify misstatements through tests and analytical procedures is known as the detection risk (Gray & Manson, 2005). The risk can further be explained as the probability of an auditor failing to detect material error or fraud in the audit

procedure (Hematfar & Hemmati, 2013). Detection risks are generated by misinterpretation of results and an absent application of specific audit procedures needed. Further, detection risk will be higher if proper audit evidence is non-collectable, indicating a higher level of uncertainty influencing the audit process (Moraru & Dumitru, 2011). When the detection risk is identified, the auditor can decide the nature, timing and amount of substantive testing needed to cover the audit risk. Hence, detention risk is important for the quality of the final audit and ties the risks together (Hematfar & Hemmati, 2013).

3.2.3 Risk management under uncertainty

As mentioned before, risk management literature presents several definitions of risk. However, the suggestions can be divided into two categories: one where risk is defined as means of probabilities and expected values, and another where risk is expressed as a result of consequences, events, and uncertainties. In the latter, risk is characterized as activities that produce different consequences and events that in turn are subject to uncertainty (Aven & Renn, 2009).

Building on the assumptions of risk management literature, audit risk assessments might be reflected by an uncertain environment. Literature argues that a dynamic and changing environment has a great impact on risk judgements, where the assessment has to be constantly changed in order to match the development of the society. Further, an aggressive and highly competitive business environment will influence decision-makers to put more focus on short-term survival and finances, instead of long-short-term aspects such as societal impact and safety (Rasmussen, 1997). Additionally, when performing risk judgements during uncertain contexts, it is of high importance to identify the most critical and essential contributors to risk. However, this is argued to be one of the most challenging parts of the judgement. Researchers therefore have attempted to establish various models for uncertainty risk judgement and management, however, there is no common model agreed upon (Aven, 2016).

Managing uncertainty and its entailed risk is however not only about identifying and handling perceived threats and their implications. It is about identifying all possible sources of uncertainty, which shape the perception of a threat, and exploring and understanding the origins of the complexity. This should be the first step before trying to manage or control the risk, with the goal of understanding where uncertainty is of importance and why. Only after this is clarified, it will be possible to discuss what can be done in order to minimize the uncertainty

(Ward & Chapman, 2003). The outcome of a decision made under uncertainty will show whether it was the right call or not, either derived from great planning or fortune. Therefore, how the situation is handled is usually more important than what is decided. Hence, the actions involved in determining the problem, selecting the options to be evaluated and determining the level of information necessary for making a decision together forming the decision process are of highest essence for the outcome (Finkel, 1990).

Power (2004) argues that the line between risk management and internal control has become thinner, with the two being increasingly co-defined. The reason for an increased focus on risk management is stated to be a response to a more dangerous and riskier environment, where the conditions of operations are more demanding. Over time, risk management seems to have moved from being a back-office operation to an essential component in the business model. However, increased focus on risk management also implies an emphasized focus on processes, hence voluntary codes and in-house procedures are almost as important as laws and regulations (Power, 2004).

3.3 Individual aspects

3.3.1 Professional judgement

To develop a reliable audit plan where risks are addressed accurately, auditors need to exercise professional judgement. It is important when deciding upon the amount of audit evidence that needs to be collected and in choosing proper analyses to be performed (Griffith, Hammersley & Kadous, 2015). Professional judgement should be used in all stages of the audit process. For instance, it is important in testing the financial population of data, drawing correct audit opinions, and accepting new clients. Altogether, it is mandatory for giving assurance that the financial statements are free from material misstatements (Chiş & Sorana, 2015).

The idea of professional judgement is grounded in profession theory since professionals are trained and expected to exercise specific knowledge and skills (Freidson, 1984). When exercising professional judgment, two different types of information can be used to assure the reliability of the financial statements: hard and soft information. Hard information refers to information that is both observable and verifiable while soft information is observable, but not verifiable (Arruñada, 2000). Hence, when assessing risks and taking professional decisions, the base is not only easily quantified and verified data but foremost subjective and non-quantifiable information. This subjective information is often the most useful and important information for

users of financial reporting (Grout et al., 1994). High audit quality increases the informational value for third parties involved and to maximize the value, the soft information needs to reach third parties. Hence, an auditor must process this information with professional judgement, combined with the hard information (Arruñada, 2000). This indicates the importance of the ability of auditors to be able to process and judge a large amount of information (Arruñada, 2000; Grout et al., 1994). Moreover, professional judgement is present throughout the whole audit, hence, including to form conclusions about the validity of the collected evidence and the figures in the financial statements (Gray & Manson, 2005). Thus, allowing professionals in the form of auditors to perform professional judgement and through this assure subjective information. Henceforth, exercising this judgement is of high importance both for the profession as well as for the quality of the audit (Freidson, 1984; Grout et al., 1994).

If applying behavioural theory, individual traits are derived over time (Skinner, 1985). This implies that the trait of professional judgement is derived over time, signalling that events and challenges met throughout the career are shaping the individual ability to perform professional judgements. Furthermore, behavioural theory inclines how an auditor’s ability to make high-quality judgements are reflected by their personal characteristics (Sanusi, Iskandar, Monroe & Saleh, 2018). Within audit literature, a few studies are exploring the effects that individual factors have on the audit judgement performance (Abdolmohammadi, Searfoss & Shanteau, 2004; Iskandar & Iselin, 1999; McKnight & Wright, 2011; Sanusi et al., 2018). The findings suggest that in addition to attributes such as knowledge and experience, traits in terms of leadership, confidence, and communication skills are important and that problem-solving abilities distinguish superior judgements from lower quality ones (Abdolmohammadi et al., 2004). Further, the effectiveness of client interaction together with professional behaviour and attributes are argued to increase the performance of auditors. Also, internal- and external locus of control and the self-confidence of auditors are displayed as factors increasing the amount of work put into audit judgement, determining the quality of these (McKnight & Wright, 2011). Iskandar and Iselin’s (1999) research findings even indicate how variations of materiality judgements between different auditors are due to the personality characteristics of these. Hence, the authors argue that reflections of each individual is important for the performed professional judgements (Iskandar & Iselin, 1999).

Additionally, it is argued that motivation is an important factor for the quality of professional judgement (Libby & Luft, 1993). Kadous & Zhou (2019) contribute to this discussion by

examining salient intrinsic motivation and the connection to judgement. They conclude that individuals with salient intrinsic motivation can handle larger amounts of information better and are better at seeking the most fitting evidence. In an unstable environment, it is more critical with finding and processing information. Hence, having this type of motivation is beneficial in complex situations, where improved judgement is highly valuable and thus, firms need to put effort into ensuring that the auditors are motivated (Kadous & Zhou, 2019).

However, operating within complex and uncertain settings pushes the auditor to make judgements and decisions based on limited knowledge, time, and resources. Because of this, the auditor will turn to simplified rules and heuristics supporting the decisions to be made, within the limits of his rationality. Usually, this is what enables humans to make strategic and foremost fast taken choices and decisions, however, it might as well cause judgemental errors (Gigerenzer & Selten, 2002). Furthermore, professional judgement can be disturbed when the auditor has a long-term work relationship with the client. Hence, to avoid incentive problems, a more frequent audit rotation is needed. Another factor harming professional judgement is regulatory changes in financial reporting. When an auditor has less knowledge of the current regulatory framework, the level of comfort in demonstrating the misstatements in the financial statements will be reduced. Hence, the quality of the judgements will be lower as a result of these changes (Nelson, 2009).

3.3.2 Professional scepticism

Literature expresses that the level of scepticism exercised within auditing is crucial for how the result of an audit process will turn out (Hussin et al., 2017; Nolder & Kadous, 2018; Vinten et al., 2005). Professional scepticism is even displayed as the most common proposed cause for audit deficiencies when the level performed is low (Nolder & Kadous, 2018). To perform a high-quality risk assessment is therefore argued as dependent on professional scepticism (Vinten et al., 2005). The concept of scepticism refers to the habit of suspending judgement until the opposite is proven by reliable information or evidence, and consistent pessimistic rather than optimistic thinking (Hussin et al., 2017). Despite past experiences and thoughts about the management of the client, an auditor should enter an audit with professional scepticism since the possibility of material misstatements always is present. However, scepticism is a broad subject, opening up for different interpretations among both auditors and researchers (Nelson, 2009).