Children’s Influence

-Regarding Home Delivery Grocery Bags with Familyfood Optima AB in Focus.

Master’s thesis within Business Administration Authors: Sophie Stenberg

Josefin Haglund

Tutor: Helén Anderson

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Karin Ahlqvist, Charlotta Alberius and Tobias Gustavsson on Familyfood Optima AB for many rewarding meetings and all their contribution for doing this study possible. We would also like to thank all the respondents that let us into their lives and made it possible for us to assemble our empirical findings.

Furthermore, we would like to thank our tutor Helén Anderson for the good feedback and support we have got through the whole process when writing this thesis. Also we would like to thank the members of our seminar group that have contributed with inspiration and many interesting discussions.

Jönköpings International Business School May, 2012

_________________________ ________________________

Master’s Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Children’s Influence -Regarding Home Delivery Grocery Bags with

Familyfood Optima AB in Focus.

Authors: Sophie Stenberg

Josefin Haglund

Tutor: Helén Anderson

Date: 2012-05-22

Keywords: Children’s influence, Pester Power, Parental Yielding, Purchasing

Decision, Home Delivery Grocery bags, Familyfood Optima AB

Abstract

Background Children are influencing the family’s decision making process regarding food products. The children’s spending power is increasing and they become consumers in an early age. By influencing the parents, the children make them buy products that they had not planned to buy or make the parents avoid products that they usually would have bought. Online food shopping is increasing in Sweden and the home delivery grocery bag is the category of online food that has increased the most from 2010 to 2011. Familyfood Optima AB is one of the home delivery grocery bags companies that deliver grocery bags in the south of Sweden.

Purpose The purpose of this thesis is to find how children affect their parents’ behavior of purchasing home delivery grocery bags.

Method To understand how children affect their parents in the decision of home delivery grocery bags a qualitative approach was used where twelve semi-structured interviews were held. Seven of the interviews were held with customers to Familyfood Optima AB. Four interviews were held with non-customers that had been non-customers to Familyfood Optima AB and one interview was held with a respondent that never had been a customer of a home delivery grocery bag company.

Conclusion Children are influencing their parents in the decision to purchase home delivery grocery bags. They also influence the parents in the decision of whether or not to continue purchasing the home delivery grocery bag. The decision of purchasing a home delivery grocery bag depends on the children’s influence and the extent of the parent’s yielding.

To influence their parents, the child use both direct and indirect influence techniques and three of the five bases of power. The children’s influence is also dependent on the child’s age and the influence from peers.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 Home Delivery Grocery Bags ... 1

1.1.2 Familyfood Optima AB ... 2

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2

1.3 Purpose ... 3

1.4 Research Questions ... 3

2

Children’s Influence versus Parents’ Yielding ... 4

2.1 Children’s Influence ... 4

2.1.1 Direct and Indirect Influence ... 5

2.1.2 Influence through Social Power ... 6

2.1.3 Peer Influence ... 7

2.1.4 Influence Varies by Age ... 7

2.2 Parental Yielding ... 10

2.2.1 Age of the Parents ... 10

2.2.2 Food Culture ... 11

2.2.3 Parental Style ... 11

2.2.4 Education ... 12

2.3 The Children’s Influence Model ... 13

3

Method ... 14

3.1 Sampling Method ... 14 3.2 Respondents ... 15 3.3 Pilot-testing ... 15 3.4 The Interviews ... 16 3.5 Questions ... 16 3.5.1 Customers ... 16 3.5.2 Non-customers ... 19 3.6 Ethics ... 19 3.7 Challenges ... 20 3.8 Data Analysis ... 203.8.1 Children’s Influence Model as an Analyzing Tool ... 22

4

Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 23

4.1 Children’s Influencing Factors ... 24

4.1.1 Direct Influence ... 24

4.1.2 Indirect Influence ... 30

4.1.3 Influence through Social Power ... 32

4.1.4 Peer Influence ... 37

4.2 Parents’ Characteristics regarding yielding ... 38

4.2.1 Parent’s Age ... 38

4.2.2 Food Culture ... 39

4.2.3 Parental Styles ... 43

4.2.4 Education ... 47

4.3 Familyfood Optima AB ... 48

4.4 Concluding Analysis of Children’s Influence ... 50

4.4.2 Indirect Influence ... 51

4.4.3 Influence through Social Power ... 51

4.4.4 Peer Influence ... 52

4.4.5 Age of the Children ... 52

4.5 Concluding Analysis of the Parents’ Yielding ... 53

4.5.1 Parents’ Age ... 53

4.5.2 Food Culture ... 53

4.5.3 Parental Style ... 54

4.5.4 Parents’ Education ... 54

4.6 The Children’s Influence Model ... 54

5

Conclusion ... 56

6

Reflections ... 57

6.1 Discussion and Critique of Method ... 57

6.2 Recommendations to Familyfood Optima AB ... 57

6.3 Further Research ... 58

Figures

Figure 1 The Children's Influence Model. Constructed by Haglund and Stenberg,

2012 ... 13

Figure 2 Children's Influence Model as structure for the analysis ... 22

Figure 3 Children’s Influence Model in a revised version ... 55

Tables

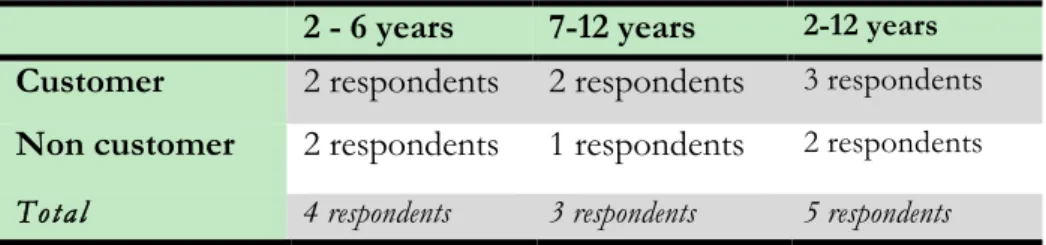

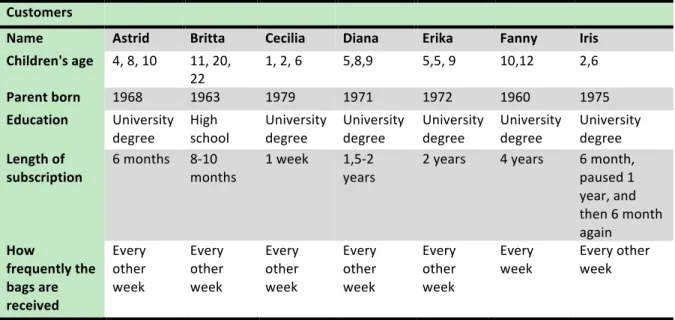

Table 1 Number of respondents and age of the child ... 15Table 2 The customers' background information ... 23

Table 3 The non-customers' background information ... 23

Table 4 Distribution of parents in the different generations and customers or non-customers ... 38

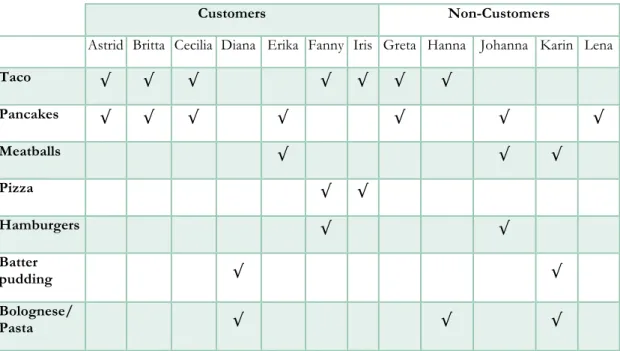

Table 5 Favorite dishes ... 43

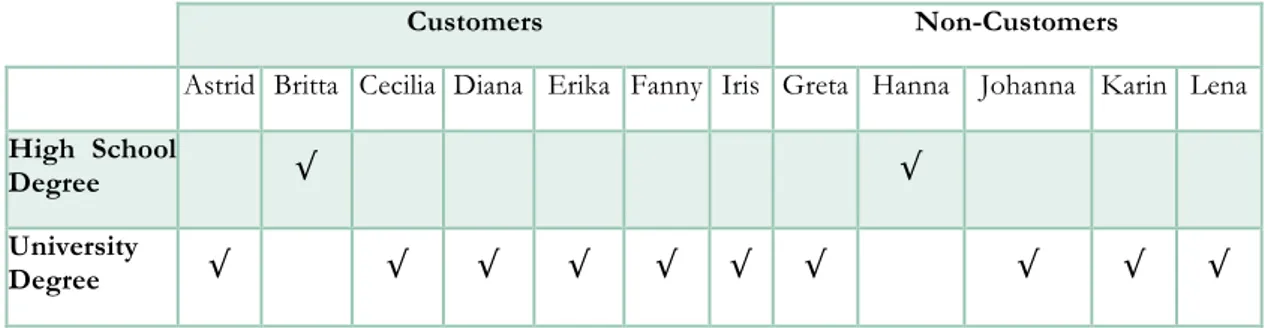

Table 6 The education level of the parents ... 47

Table 7 Summary of the influencing factors ... 50

Table 8 Summary on characteristics that affect parental yielding ... 53

Appendecies

Appendix 1 Interview questions ... Appendix 2 Quotations ... Appendix 3 Coding ...

1

Introduction

In the first chapter the background to the problem is presented, also introductions to the concept of home delivery grocery bags and the company Familyfood Optima AB are given. The chapter continues with problem discussion, purpose and research questions.

1.1

Background

A family’s decision making process is influenced by the children and the children’s spending power is increasing (Shoham & Dalakas, 2005). By influencing their parents, children get their parents to purchase products that are not directly available for them (Berey & Pollay, 1968). Some blame the advertising industry for the reason to why children nag about products (Spungin, 2004).

A concept involved in the influence process is “pester power”. Bridges and Briesch (2006) define pester power as the “nag” factor, meaning that the child influences their parents buying decision by nagging. Shoham and Dalakas (2005) have a broader view on pester power and say that pester power is the influence on the family’s consumption pattern, while Gunter and Furnham (1998) is more precise and say that pester power is the process where the child asks the parent to buy a product. Parental yielding is another concept that means that the parent complies with the children’s requests (Ekström, 1995). E.g. a child asks for a toy and the parent buys the toy for her.

The children’s influence varies depending on what kind of product it is, the influence is higher if it is a product that the child is involved in (Mehotra & Torges, 1977), for example food, snacks, toys and clothes are products that are highly influenced by children (Mangleburg & Tech,1990). Food is a high involvement product that children try to influence (Mangleburg & Tech, 1990; Nørgaard, Bruns, Christensen & Mikkelsen, 2007). When several of the family members are involved in the buying process of food, conflicts may arise (Nørgaard & Brunsø, 2011).

In a study done by Nørgaard and Brunsø (2011) conflicts regarding food arise from four aspects: the individual preferences regarding food, the parents’ childhood habits, if the family members have health habits and the children’s home economics. There are several influence techniques that both the children and the parents can use to get the family to purchase what they prefer. The family member can just say what she like, or she can provide an idea what she likes to have for dinner. If there are several children in a family the siblings can join each other and argue together what they want and in that way try to convince the parent’s to buy what they prefer. (Nørgaard & Brunsø, 2011)

The influence also varies by age (Ward and Wackman 1972; Atkin, 1978; Isler, Popper & Ward, 1987; McNeal, 1999). When the child gets older she tends to decrease her influence attempts but the parent yields more often (Ward and Wackman,1972), and Rust (1993) said that parents yield more often to older children.

1.1.1 Home Delivery Grocery Bags

The online food shopping is an increasing market in Sweden, it increased with 40 percent from 2009 to 2010. Younger consumer groups are more positive towards online food shopping than older consumer groups. (Svensk Handel, 2011)

The main reason for why people tend to shop online is, according to Morganosky and Cude (2000), convenience and especially the time saving constraint. One other reason that

was found in Morganosky and Cude’s (2000) research was the fact that it is beneficial to do the online grocery shopping when the children are present. It can be difficult to take them to the store and it is expensive to pay a babysitter while grocery shopping. (Morganosky & Cude, 2000)

There are three ways of buying food online; purchasing groceries from a grocery store and get it delivered, home delivery grocery bags with recipes and ingredients and smaller stores that are specialized in specific products. The home delivery grocery bags are the category that has increased the most since 2010. (Svensk Handel, 2011)

The Home delivery grocery bag is a business concept where the customers get a bag with food delivered to the door once a week, or less often, including recipes and ingredients for five dinners for four people. There are several companies in Sweden with almost the same concept but it is adjusted to suit different demands and lifestyles. The companies have niches where some focus on healthy food and other on ecological food or their own specialty. The bags can be ordered online at the various companies’ websites and the price for a bag is normally around 750 SEK (approximately USD 105) including shipping. (Familyfood’s webpage, 2012; Linasmatkasse’s webpage, 2012; Middagsfrid’s webpage, 2012).

1.1.2 Familyfood Optima AB

Familyfood Optima AB1 was established in 2007 and they provide their subscribers with

home delivery grocery bags in the south of Sweden. Karin Ahlqvist, Charlotta Alberius and Tobias Gustavsson own the company, that was founded 2007 by Karin and Charlotta. Familyfood also has one employee who works part time. Familyfood delivers approximately between 500-700 grocery bags every week. The consumer can decide if she wants to have the bag delivered every week or every other week. (K.Ahlqvist & C.Alberius, personal communication, 2012-02-08).

The company uses ecological and locally produced food that is produced in the south of Sweden. The owners of Familyfood sets up the recipes every week by themselves and get help from a dietician to control the nutrition in the food from time to time. Familyfood also co-operate with a chef that also is one of Familyfood’s suppliers. (K.Ahlqvist & C.Alberius, personal communication, 2012-02-08)

Familyfood has realized that one reason why a number of their consumers end their subscription is due to children’s negative attitude towards the recipes. A few customers just try the home delivery grocery bag for one week and then go back buying groceries in the store. Familyfood thinks that if the subscriber uses their food and recipes for a longer time the children get a more positive attitude towards the food. (K.Ahlqvist & C.Alberius, personal communication, 2012-02-08)

1.2 Problem Discussion

Atkin (1978), Nørgaard et al. (2007), and Shoham and Dalakas (2005) have all done studies that show that children are influencing their parents in the family decision making. The family’s food choices are one decision among others where children are highly influencing (Mangleburg & Tech, 1990; Nørgaard, et al. 2007). With the new phenomena home delivery grocery bags, the children are not involved in the buying process in the same way

as before. When the family is buying groceries in the store, the child can join them and show their request for specific products in store. But when the groceries are delivered to the home the children cannot influence the food purchase in the same way. But are the children influencing their parents when buying a home delivery grocery bag anyway? And if so, how do they influence their parents? Can they influence by not eating the food? Or do they request for other dishes? The definition of what “influence” is might differ in different families (Jenkins, 1979). Is the influence direct or indirect? Or how do the parents perceive their children’s influence, if they are aware of it at all. According to Ekström (1995, p.24) influence in family decision-making is “a change in a person’s dispositions, as a result of interaction between parents and children”.

Previous studies have shown that the influence varies by age (Atkin, 1978; Isler et al, 1987; Ward & Wackman 1972), those studies have however been made on in-store grocery shopping. The study in this thesis will be held on families who buy home delivery grocery bags online.

The home delivery grocery bag companies need to get a better understanding of their customers’ behavior and the difference between the customers and non-customers. Their target group is families with children, hence the family decision making process is important to understand. Through the understanding of the consumers’ behavior, the companies can adjust their business strategy to get a better relationship with their current customers and try to reach new customers.

1.3

Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to find how children affect their parents’ behavior of purchasing home delivery grocery bags.

1.4

Research Questions

• How essential is the child’s influence when it comes to the parents’ decision of whether or not to purchase a home delivery grocery bag?

• How does the child’s influence on a family’s food purchasing decision vary by age? • Does the children’s influence on a family’s purchasing decision differ between

2

Children’s Influence versus Parents’ Yielding

There are many previous studies to look at in the subject of how children influence their parent’s purchase decisions. In this chapter we are presenting the theories that we think are most important in order to fulfill the purpose of this thesis.

2.1

Children’s Influence

On an average, children between four and twelve years old make around fifteen requests per shopping trip and along with requests at home and on vacation it adds up to around 3000 requests per year (McNeal, 1999). When a child is making requests like this it can be referred to as pester power and it can be defined as “a child’s attempts to exert influence over parental purchases in a repetitive and sometimes confrontational way but -and this is important- also with some degree of success” (Nicholls & Cullen, 2004, p. 77). When a parent brings her child to the supermarket it is most likely to be because there was no other choice than bringing the child (Nicholls & Cullen, 2004). The parent wants to do the shopping quickly but the child sees it as an opportunity to influence the choices of products to purchase (Nicholls & Cullen, 2004).

The fulfillment of the requests vary with the age of the children where the youngest children’s requests tend to be fulfilled more often than when the child reaches an age of six or seven. When the child becomes eleven or twelve the fulfillment rate increases again. One outcome of fulfilling a request is for the parent to get a closer relationship to the child. (McNeal, 1999)

It is argued that the companies encourage children to make requests or “nag” at their parents by directing advertisement directly to the children (Spungin, 2004). The main reason why so much attention has been paid to children and advertising in the social context is the pester power (Preston, 2004). Kurnit (2005, p.10) argues that “the kids industry has done itself no favors by referring to kid product influence with the expressions “nag factor” and “pester power”.

Pester power also implies that children are influencing their parents to buy food that they otherwise would not buy. It is however only one of many factors that are influencing parents purchasing behavior. Other than pester power, the nutrition value and the money value are important factors that influences a parents food purchase. This is according to a research undertaken by raisingkids.co.uk with 1530 parents participating across UK. The same study showed that 80 percent of the mothers had been asked to purchase a new product that was likely that the child had seen advertised. Another important factor was the peer influence. The children want to have the same products as their friends. (Spunging, 2004)

McNeal (1999) has another perspective on pester power where he says that it is the parents way of bringing up their children that make them ask for things they want. He argues that children learn from a young age to ask for products instead of just take it from where they found it. It can occur when a parent and the child are visiting a friend and the child wants to play with a toy that is not hers. The mother will teach the child to ask for it before starting to play with it or wanting to bring it home. Eventually the child will start to ask for products more frequently and the parent will start to see it as nagging instead of the child being polite. McNeal (1999) argues further that marketers are responding on the fact that

parents teach their children to ask for products rather than blaming them for the nagging. (McNeal, 1999)

Advertising is created to increase the demand for products and when it increases the demand for children it is blamed to create pester power as the children will ask their parents for the product they have seen advertised (Preston, 2004). “Criticizing advertising for creating demand is like criticizing a car for moving on four wheels along the ground” (Preston, 2004, p. 366)

To find how children influence their parents, we analyzed five theories; direct- and indirect influence, social power theory, the age of the child and the peer influence. The theories will be explained in the next section.

2.1.1 Direct and Indirect Influence

Children affect their parents purchasing decision both directly and indirectly. Whether the child exerts direct or indirect influence depends on the degree of the participation by the child during the decision-making process. Direct influence is when a child is actively

involved in the purchase. It can be that she hints, asks, demands and recommends products with different wordings. A typical wording could be “can we get these?” (McNeal, 1999, p.88). The request or demands are not only used in the store while shopping, it is also used at home and often in connection to playing, snacking and watching TV. According to McNeal (1999) the influence varies depending on the nature of the product, the child’s age, the stage of the decision process (mostly for expensive durable goods) and the parenting style. (McNeal, 1999)

According to Wells (1965) children have a more direct influence when they are young. The locations where the requests are made are in the store and at home. When the child is older she does not request as often since she knows that some products are not worth asking for since she knows that she will get a “no” as an answer. (Wells, 1965)

Indirect influence is when the parents take their children’s wants and needs into consideration when making a purchase decision (McNeal, 1999). Through indirect influence children have a passive role in the decision-making process (McNeal, 1999). When the child gets older the parents learn what the child wants, the parents know what the child likes and dislikes and therefore buy products that will please the child, Wells (1965) called this “passive dictation” (Wells, 1965). Indirect influence is difficult to measure and thus has not been considered as much as direct influence when it comes to the marketing of products (McNeal, 1999). Indirect influence is however exerted more often than direct influence by children (McNeal, 1999).

We wanted to find out if the concepts of passive/indirect and direct influence also were true when it comes to the parents’ decision of purchasing home delivery grocery bags. The “passive dictation” might be an influence technique that many parents are not aware of or the parents are not thinking of it as an influence technique. In a study done by Jenkins (1979) the definition of what influence is, perceives differently from one person to another. The influence can be seen as only the active aspect while others see the influence as both active and passive. (Jenkins, 1979)

2.1.2 Influence through Social Power

Flurry and Burns (2005) used the social power theory by French and Raven (1959) to understand the children’s influence in a family’s decision process. French and Raven (1959) define five bases of power, which are; reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, referent power, and expert power. These bases of power can be used to influence others and the influence can be derived both from passive and active power (French & Raven, 1959).

If person A has the ability to reward person B in exchange of that person B does something for person A, person A has reward power (French & Raven, 1959). E.g. an employer has reward power over an employee, since the employee needs to work to get paid from the employer. Flurry and Burns (2005) applied the social power theory on family decisions and explain that the reward power in a family can be used by the children to influence their parents by rewarding their parents with a good behavior. For example, if the parents buy something for the child, the child promises to behave well.

Coercive power is similar to reward power, but in this case person A has power over person B just because person B thinks that she will be punished if she does not do as person A wants (French & Raven, 1959). Flurry and Burns (2005) applied this to the family and said that a child has power over the parent if the parent thinks that if she does not do as the child wants the child will misbehave or complain.

Person A has legitimate power when she holds a position or role where other people know she should be respected and listened to, in this position people perceive that person A has the right to influence (French & Raven, 1959). Such a position can be a policeman or a manager. According to Flurry and Burns (2005) a child has legitimate power if the decision is made regarding a product that will be consumed by the child, because it is seen as the children’s right to influence. Examples of such products are food, toys or clothing (Flurry & Burns, 2005).

Referent power is based on to which degree a person wants to be identified with another person and this is because a person wants to be like another person or feel a desire to join that person (French & Raven, 1959). A parent who wants to be identified with her child can change her behavior in certain ways (Ekström, 1995).

Expert power is based on a person’s perception of another person’s knowledge regarding a product, if person A thinks that person B has a broad knowledge about a product, person B has expert knowledge (French & Raven, 1959). A child can have expert knowledge if the parent thinks that the child has a broad knowledge about a specific product (Flurry & Burns, 2005).

The social power theory was used in our study to see if the parents perceive that their children use some or several of these five bases of power to influence the family’s food purchase. According to Flurry and Burns (2005) and Ekström (1995), children use the five bases of power and it was interesting to see if this was true in our study as well.

According to Marquis (2004) who made a study on French children, the most common influence strategies the child uses are telling what food she prefers and having opinions about different food dishes. But children also use more emotional techniques like begging or being especially nice to their parents just to make them purchase what the child wants (Marquis, 2004). We think that these emotional techniques like begging can be seen as

coercive power and the fact that a child is especially nice to their parents to make them buy a product can be reward power.

According to Nørgaard and Brunsø (2011) another influence technique is “conflict avoiding” which is also a communication strategy and part of the conflict resolution. Sometimes the family members need to pick their fights and by purchasing different food options all family members can be pleased (Nørgaard & Brunsø, 2011). In this way the parents let the children have what they want just to avoid a conflict. We think this is a consequence of the coercive power. To avoid that the child will be angry or complain, the parents buy what they think will please them.

2.1.3 Peer Influence

Nicholls and Cullen (2004) argue that peer pressure is one reason for why children want to purchase various products and might pester their parents about it and that advertising is not the reason for it (Nicholls & Cullen, 2004). It can be convenient for the parents to blame the advertising for the nagging the children is exerting (Preston, 2004).

According to Bachmann, John and Rao (1993) a child needs to have developed certain social sensitivities and cognitive skills to get influenced from others in their product decision. Firstly the child needs to understand that others have different perspectives and that their opinion may not be the same as hers. Secondly the child needs to understand that people draw conclusions of each other out of the products they buy. Lastly the child needs to think that other opinions are important when forming her own self-perception. If the child has not developed these social sensitivities and cognitive skills the influence from others will be weak or not present at all. (Bachmann, et al., 1993)

According to Piaget (1964/2008) a child in the age two to six cannot differentiate its own opinions from others, instead the child thinks that everyone has the same perspective and opinions as herself. If it is true that the child needs to have developed a certain social sensitivities and cognitive skills to feel the influence from peers, the peer influence should be weak for children in the age two to six. When the child turns seven, Piaget (1964/2008) said that the child learns how to differentiate its own opinions from others and understand that people have different perspectives. With this in mind, children older than seven should be influenced more by peers than younger children.

2.1.4 Influence Varies by Age

Previous studies have shown that a child’s influence varies by age (Atkin, 1978; Isler et al., 1987; McNeal, 1999; Rust, 1993; Ward & Wackman, 1972). In this section previous studies about how children’s influence varies by age and Piaget’s cognitive development theory is explained.

Different Studies about Age

Ward and Wackman (1972) studied the children’s purchase attempts and the parents yielding on those attempts. Their results showed that children try to influence their parents frequently when it comes to food products, but as the child grows older the attempts decreased. Even though the children ask for less when they grow older, the mother yields more often. Ward and Wackman (1972) could also see a correlation between conflicts and influence attempts, meaning that the influence attempts are part of a disagreement in the family. (Ward & Wackman, 1972)

Atkin (1978) made a study on the parent-child interaction when families go grocery shopping for cereals in supermarkets. Atkin (1978) found that the child’s initiation of purchase decreases when the child is older while the parental yielding increases. Hence an older child is more successful in the requests than a younger child (Atkin, 1978). Both of the studies, the one done by Ward and Wackman in 1972 and the one done by Atkin in 1978, showed that an older child requests less often for products but the parent’s yield more often to the requests.

Isler et al. (1987) also did a study on children and their requests for products. His study showed as Ward and Wackman (1972), and Atkin (1978) that younger children make more requests than older children. Isler et al. (1987) grouped the children into three different groups, three- to four years old, five- to seven years old and nine- to eleven years old. The requests were dependent on what kind of product it was, three- to four year old children often request for toys and candy but these requests decrease with age. The request for cereals and snacks remained constant during the age groups. Isler et al. (1987) also said that the location for the requests changed by age. When the child is in the age of three to four 45 percent of the requests are made at home and 40 percent of the requests are made in store. When the child is in the age eight to eleven 64 percent of the requests are made at home and only 20 percent are made in store. Isler et al. (1987) thinks this can be a result of that older children join their parents to the supermarket less often than younger children. (Isler et al.,1987).

According to Isler et al. (1987) a reason to why the requests decrease by age can be because of “passive dictation” defined by Wells (1965). As explained above, passive dictation is when the child is older and does not need to request for a product since the parent already know what the child prefer (Wells, 1965).

Rust (1993) made a study on how children’s purchase behavior varies in different ages. He defines young children as five years old and below, and older children are in the age of six to fourteen. The study showed that parents yield more often to older children, age ten and older. He also discussed if it can be due to that older children have more power or if the children know in advanced what the parent will yield to. (Rust, 1993)

McNeal (1999) also said that the child’s influence varies by age. When the child is two to three years old the parental yielding is high, the parents yield to around 70 percent of the child’s requests. But the parent’s yielding decreases when the child is four to nine years old, where the parents yield to approximately 50 percent of the child’s requests. When the child is ten to twelve years old the parent’s yielding starts to increase again to approximately 60 percent. (McNeal, 1999)

It was interesting to see that so many previous studies had the same result, that the requests decreased by age and that parents yield more often to older children’s requests. All previous research above has been done in store, the study in this thesis is held in perspective of home delivery grocery bags. The previous studies are compared with our result to see if the same patterns of age can be recognized in families that purchase home delivery grocery bags.

Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory

Piaget (1964/2008) said that the psychology growth starts when a person is born and end when the person is an adult. He divided the children into four different age groups, the sensorimotor stage (0-2 years old), the preoperational stage (2-6 years old), the concrete

operations stage (7-12 years old), and the formal operation stage (13-adult). Six different stages in a child’s psychology development are developed through these four age groups. The three first stages develop in the first age group, sensorimotor stage and then the other three stages are divided one in each age group (Piaget, 1964/2008).

Sensorimotor stage-When the child is born until it is one and a half to two years old the child develops the three first stages in the development process. In the first stage the child starts to get its reflexes. The second stage is the perception stage, the child starts to show reaction to sounds and moving objects, and start to recognize people. In the third stage the child starts to develop its intelligence, which starts before the child learn how to talk. The child shows its intelligence by combining the perception and movements in an act, e.g. the child use a stick to reach an object. When the child is born it cannot differentiate herself from the rest of the world, when the child is around one and a half years old she can different herself from other people and objects and can see the causality. (Piaget, 1964/2008)

Preoperational stage- When the child is two to six years old, she enters the fourth stage. In the fourth stage the child is verbal and starts to socialize with other people. The child also develops emotionally and feels sympathy and respect for others. With the help of the language the child can now communicate with other people but does not know how to discuss subjects. The child knows how to make statements but cannot explain things very well and have a hard time to understand others explanations. The verbal communication is very self-centered and the child does not make any effort to prove its statements since the child cannot differentiate her own opinion from others. People just care to prove statements for others and if they do not understand that their opinion differ from others they do not care to prove it. (Piaget, 1964/2008)

Concrete operations stage- It is an essential turning point in the child’s psychological development when the child turn’s seven and stage five begins. The child learns how to cooperate with others and that is because a child in this age understands that people have different opinions and learn how to organize the opinions. In this age the children also know how to discuss subjects with each other and they develop their ability to give explanations to others. When the child is seven to twelve years old they develop their emotions and new moral feelings arise, which lead to a better “me-integration “ and a more effective control of the feelings. Consensual respect is a part of the new emotions and is important for the child’s social life. (Piaget, 1964/2008)

Formal operations stage- When the child is twelve years old the child enters stage six in the development of the psychology and gets a freer and more reflective way of thinking, the child starts to build abstract theories about situations that might happen in the future. The child can make conclusions of hypothesis that are not real, in contrast with a child under twelve that only can handle a current problem. During this age-period when the person is between twelve and adult, the person’s personality also reaches its final development. (Piaget, 1964/2008)

We think that the different stages in the child’s psychology development are interesting to consider when doing our research. Piaget’s development theory was used to set the age range of the study. We have chosen to focus on children in the age two to twelve because we thought those two age groups were interesting since a lot happens in the development during these years that is relevant to our study. By doing so we can get a better understanding of how children act and think in the different age groups and compare it with our results.

2.2

Parental Yielding

Ward and Wackman (1972) explain parental yielding to be the fact that parents fulfill the requests of their children. Among other products, food is one that children attempt to influence their parents about most often. Food is also the product category where parents are most likely to fulfill the requests. The frequency of those requests is shown to decrease by age. One reason may be that older children are thought to be more competent to make a good judgment about the product. Even though the frequency of the requests decreases by age, the yielding by the parents is shown to increase by age. (Ward & Wackman, 1972) A study undertaken by Ward and Wackman (1972) shows that the more often a child asks for a product the more often the parent will yield to the request. The same study also showed that if the parents were strict about television viewing it was likely not to yield to a request by the child, it would however not reduce the influence attempts by the child. This type of parental control does thus not decrease the nagging from the children. (Ward & Wackman, 1972)

There is a relationship between yielding and the attitude towards advertising for food. Parents with a positive attitude towards advertising are more likely to yield to purchase attempts done by their children. The nagging does however not change with the parent’s attitude towards advertising. (Ward & Wackman, 1972)

Parents use different techniques to decline a request by their child. The two most commonly used techniques according to O´Dougherty, Story & Stang (2006). are that parents provide an explanation or ignore the request. Sometimes the parents give a strict “no” as well but that technique was not used as often in their research. (O’Doughtery et al., 2006). When a parent denies a child to purchase a product it is most often with an explanation such as “it is too expensive” or “it has poor value” (Ward, Robertson, Klees, & Gatignon, 1986).

To find out what affects the parental yielding, we analyzed four characteristics of a parent; the age, their food culture, their parental style and their level of education. This is presented in the next sections of the chapter.

2.2.1 Age of the Parents

A characteristic that we thought could affect how much the parents yield to their children’s request was the age of the parents. There are different generations, which are called, pre-depression generation, pre-depression generation, baby boomers, generation X, generation Y and generation Z.

There are different opinions about where exactly the age line goes between the different generations. According to Williams and Page (2010), the pre-depression generation is born before 1930, depression generation is born 1930-1945, baby boomers are born between 1946-1964, generation X between 1965-1977, generation Y is born between 1977-1994, and generation Z is born after 1994. We have focused on baby boomers, generation X and generation Y.

Baby boomers- According to Hall and Richter (1990) the baby boomers are concerned to stick to basic values, there are no particular values for baby boomers, just that they have their own basic values that they follow, and they feel that they can act on these values. By having these strict values and feel that they can act on them, they also have a strong self-awareness. It requires freedom to live after its own values and they are impatient when it

comes to hierarchical authorities. The baby boomers also have a great concern for its family, and prioritize family before work. According to Hall and Richter (1990, p.11), the baby boomers say “I work to live, I don’t live to work”. (Hall & Richter, 1990)

Generation X- Generation X was the first generation that was introduced to malls in an early age and no generation has spent as much time in malls as generation X (Roberts & Manolis, 2000). Due to this they say that generation X’s main interest are shopping and material things. Generation X was also the first generation to get cable television and is spending plenty of time in front of the television. The television and the Internet have made the generation X consumer oriented and consumer-savvy due to the exposure of marketing messages. (Robert & Manolis, 2000)

Generation Y- According to Tulgan and Martin (2001) generation Y is perceived negatively as lazy and self-interested, but Tulgan and Martin (2001) bring up four positive factors about generation Y. They say that they are a generation with confidence and self-esteem and that they are the most well educated generation. They are further the reason to why the society will be more open and tolerated in the future and they are willing to volunteer. Tulgan and Martin (2001) also say that generation Y thinks it is important to be taken serious at work, that their age should not be important but instead what they do. (Tulgan & Martin, 2001)

According to Roberts and Manolis (2000) age is the most important characteristic for marketers and researchers. We wanted to find out if we could see any differences in parents yielding by looking at their age. For example, since baby boomers think that their own values are important, baby boomers might be less likely to yield to requests outside those values. Generation X is said to be very consumer oriented and consumer-savvy, this might mean that they are more aware of their children’s influence.

2.2.2 Food Culture

Fjellström (2009) argues that food is not just something that we need to survive. The food means a lot more to humans, the meaning of food is connected with how we eat, with who we eat, how we talk about food, how we cook and how we behave around a table. So the human’s identity has a strong connection with food. In Sweden the food culture is connected with many factors, people do not just care about the nutrition in food. Factors connected to food can be emotions, attitudes, values, religion, education, gender, and behaviors. The food is a big part of the human life, how we prepare the food, cook it, present it and consume it, this express how we are as humans. (Fjellström, 2009)

According to Ekström and Jonsson (2009), the nuclear family meal, with a mother, father and two children, where the whole family sits down at the same time around a dining table, might not be that common today as it was before.

Since Fjellström (2009) said that the human’s identity has a strong connection with food, we wanted to find out if the culture around food affected the parent’s yielding. If the parents have a strict food culture, it might make the parents stricter in their decisions what they agree to buy or not.

2.2.3 Parental Style

Baumrind (1966) found three main styles of parenting when making research on preschool aged children. The three styles are called authoritarian, authoritative and permissive.

Authoritarian - In comparison to a permissive parental style an authoritarian style involves a lot of structure where the parent attempts to shape and control the child. As help the parent normally uses standards created by higher authority that also is motivated by the theology. The parent has high demands on the child and wants her to behave well. If their child would misbehave the parent can use punishments to make the child behave in a better way. The parent does not argue with the child, if she says something she expects the child to obey and does not take any verbal discussions. A “no” is a “no” and there is no way the child can change it. (Baumrind, 1966)

Authoritative - An authoritative parental style is not as strict as the authoritarian. The parent encourages verbal discussions and explains the reasoning behind decisions she makes. The children’s activities and wishes are met in a rational manner. The child’s self-will is highly valued by the parent as well as the child’s disciplined conformity. When the parent and the child have different opinions, a parent with an authoritative parental style would exert firm control. Baumrind (1966) said that “She (the parent) enforces her own perspective as an adult, but recognizes the child’s individual interests and special ways” (Baumrind, 1966, p. 891). She uses power, reason and reinforcement to reach her goals. (Baumrind, 1966) Permissive- A parent that uses a permissive parental style does not exert much control or power over her child (Baumrind, 1966). The child can decide on her own what to do, as the parent does not regulate the activities to a great extent (Baumrind, 1966). Instead of using power the parent attempts to use reasoning and manipulation to get the child to do what she wants (Baumrind, 1966). A permissive parental style can thus be that a child who is not hungry does not get forced to eat and if she does not want to have a bath she does not have to.

In the study we wanted to find if we can see that the parents are using the same parental style and thus be able to connect the parental style to which extent the parents yield. Through this we could find out if the parental style affects the purchasing decision when it comes to home delivery grocery bags.

2.2.4 Education

The parents education is one factor that can affect how much influence a child exerts on her parents, it is expected that the children’s influence is higher if the parents have a higher level of education. This can be because those parents allow their children more influence. (Ekström, 1995)

When it comes to specific knowledge there can however be the opposite, that a person with a lower education let her child influence more in a specific area. One example is computers, if the parent does not know much about computers and the child does she is likely to let the child contribute with her knowledge. (Ekström, 1995)

The level of education is also thought to influences a person’s behavior. The consumption expenditures along with many other variables such as income, lifestyle and leisure-time activities are characteristics that have a strong correlation with the level of schooling. As the education influences so many variables in a person’s lifestyle it is a common way to categorize people by social scientists. (Michael, 1975)

Michael (1975) discussed if it is the level of education that is influencing the various characteristics of a person or if there are other variables such as how one uses its time that are the underpinning influence.

In Michael’s (1975) research he concludes that education has a direct influence on consumer behavior and that that is independently of the effect on monetary income. He also argues that “the effect on education is not a random or erratic one, but is systematically related to the changes in consumption patterns attribute to differences in level of income” (Michael, 1975 p.250)

2.3

The Children’s Influence Model

Based on the theories we explained above we constructed a model to get an overview of how they are related. The model in figure 1 explains what affects a family’s purchase decision. The age of the child affect the four influencing factors; direct influence, indirect influence, social power and peer influence. The four influencing factors in their turn, affect how much the children influence their parents. The four characteristics of the parents; age, food culture, parental style and education affect to what extent the parents yield to their children’s influence. The parental yielding and the children’s influence are also affecting each other, which is showed with the arrows between the children’s influence and the parental yielding. The purchasing decision is thus affected by how much the children are influencing their parents and to what extent the parents yield.

Figure 1 The Children's Influence Model. Constructed by Haglund and Stenberg, 2012

The children’s influence model explaines how the different parts in the frame of reference are realated. In the next chapter we explain what method was used to come to the conclusion on how children influence their parents in their decision making.

!"#$%&'() *($+'+,-) !&#(-.&/) 0+(/1+-2) 343) 5%+/1#(-6') 7-8"(-$() 349) 7-1+#($.)7-8"(-$() 34949) 7-8"(-$():%#,"2%) ;,$+&/)!,<(#) 34943) =2(),>).%()5%+/1) 3494?) !((#')7-8"(-$() 3494@) :%()=2(),>).%() !&#(-.')) 34349) :%()!&#(-.'6)A,,1) 5"/."#() 34343) :%()!&#(-.&/);.B/(),>) .%()!&#(-.')) 3434@) :%()C1"$&D,-),>).%() !&#(-.') 3434?) *+#($.)7-8"(-$() 34949) 7-8"(-$+-2)A&$.,#') !&#(-.'6)5%&#&$.(#+'D$')

3

Method

The chapter starts with an explanation of the chosen research design and continues with the sample tech-nique that was used and who the respondents were. Also an explanation is given of how the interviews where pilot-tested, the challenges during the chosen method, the interview questions and how the data was analyzed.

To find how children affect their parent’s behavior of purchasing home delivery grocery bags we used an exploratory research design. This was to gain knowledge in the phenomena of the children’s influence. When knowledge of a phenomenon is researched an exploratory research design is suitable as it gives an understanding of a problem that cannot be measured (Malhotra & Birks, 2007). Further we approached the problem with a qualitative technique, as it is suitable when analyzing a social phenomenon in depth (Andersen, 1990/1994; Widerberg, 2002; Jacobsen, 2000/2002). The purpose of this study was not to generalize but rather to find unique information, hence a qualitative study was appropriate (Jacobsen, 2000/2002). We wanted to get the parents’ perspective on how they perceive their children to influence the purchase decision.

3.1

Sampling Method

All the respondents in the study lived in the Jönköping area, this was because of convenience reasons since both Familyfood and we are located there. In that way we saved time and money. Familyfood helped us to find the respondents by sending an e-mail to their customer database where both current customers and former customers existed. The e-mail was only sent out to potential respondents in the Jönköping region. In the e-mail we wrote a short presentation about our thesis and ourselves and asked parents with children in the age of two to twelve to participate in our study. By writing a presentation about ourselves we hoped to get a more personal contact and hopefully the customers would be more willing to participate. Two cinema tickets were offered to the respondents to motivate the parents to participate in the study.

In total we had twelve respondents, eleven of them were found by the e-mail and one of them we got in contact with through personal contact. We interviewed respondents until we did not gain any new or unique information (Jacobsen, 2000/2002). The interview process was divided into two phases where the customers were interviewed first and then the non-customers (with one exception due to sickness). After the two phases we made a brief analysis of the information we had gained from the two phases and realized that no more unique information had been gained after the last few interviews, hence we had enough information and decided not to go further with the interviews (Jacobsen, 2000/2002).

We think that it was beneficial that Familyfood helped us to send out the e-mail since we think that the customers are more willing to open an e-mail from Familyfood than from a private e-mail address as that might have been perceived as spam. The customer might also think that it is more trustful to participate in a study that Familyfood support.

In the e-mail we suggested to have the interviews in Familyfoods office on Science Park or that we could come to the respondents’ home or work and hold the interview there. We let the respondents decide the location so they could feel comfortable during the interview (Trost, 2012). Five persons preferred to have the interview at Science Park, four persons preferred that we came to the respondent’s home and three respondents were interviewed at their work.

3.2

Respondents

The respondents were parents in families with one or several children, the age of the children were between two and twelve, and were divided into two different age groups according to Piaget’s (1964/2008) cognitive development theory. The study was concentrated to two of the age groups, two to six and seven to twelve, this to delimitate the study due to time constraints. This research was held from the parent’s perspective therefor the children were not interviewed.

Seven of the respondents were customers to Familyfood, five of them were non-customers where four of them had been non-customers of Familyfood before. In this way we could compare the answers with those who were customers today and those who had been customers. We choose to interview one person that never had been a customer because we wanted to see if we could notice any major differences between her answers and the others. We grouped the previous customers and the one who had never tried a grocery bag before into one group called non-customers. Four of the respondents had children in the age two to six, three respondents had children in the age seven to twelve, and five respondents had children in both of the age groups, two to twelve, see table 1. We divided the respondents in these three groups so it was clearer when we categorized the data. However, we differentiated the two age groups two to six and seven to twelve when we analyzed and presented the results.

2 - 6 years 7-12 years 2-12 years Customer 2 respondents 2 respondents 3 respondents

Non customer 2 respondents 1 respondents 2 respondents

Total 4 respondents 3 respondents 5 respondents Table 1 Number of respondents and age of the child

All of the respondents and their children were renamed and rewritten as females, however there were both males and females among the respondents and their children. We did not consider the fact that they were males or females because the gender was a factor we decided not to examine. We do not want to differentiate the boys from the girls among children and choose not to differentiate the mothers from the fathers. Instead we differentiate the parents from the children, the customers from the non-customers, and the different age groups. So we delimitated the study to these factors.

3.3

Pilot-testing

Before we started with the interviews we first tested the interview questions with one test-respondent by phone. The test-test-respondent was a mother of two children in the ages two and four. The advantage with the pilot-testing was that we could see if the questions were well-defined and easy to understand for the respondent. We tested the structure of the interview (Seidman, 1998) to see if the questions had a good flow together and if there were any questions that were missing or any questions that were unessential that we could exclude. The purpose of the study and the research design was also tested through the pilot-test (Wengraf, 2001; Seidman, 1998) After the phone-interview we added some questions and changed the structure and did one more pilot-testing face-to-face with a customer. By testing the interview in a real life situation we could test the questions once again but also test the recording and measure the length of the interview, so we got an

approximate time-frame. We also learned how to make contact and other practical details through the face-to-face pilot-study (Wengraf, 1998).

After the pilot-testing we made a few changes in the structure and a few questions were changed, we also got a clear picture of what we needed to do better as interviewers (Wengraf, 1998). The data was then analyzed with our “coding schema” to see if the analyze technique that we were planning to use worked.

3.4

The Interviews

The interviews were held with one parent per respondent family, and all the interviews were done in a period of two weeks. Time slots were available at all times including weekdays, evenings and weekends to ensure everyone had the chance to participate, regardless of working hours. Two interviewers were present at each occasion, one held the interview and the other observed and was responsible for the recording device. The observer wrote down the answers on a premade template to structure the answers during the interview. The respondents were asked if the interview could be recorded for research purpose and was assured that it would not be published and that we were the only one that was going to listen to it. All of the respondents agreed to the use of a recording device. By recording the interviews we could transcribe everything that was said and that was helpful for the analysis (Ryen, 2004/2004; Trost, 2012). Before the interview started we began with an introduction of who we are and our study (Trost, 2012). We also informed the respondents that they would be anonymous (Trost, 2012). The time of the interviews differed between 30 and 40 minutes.

Semi-structured interviews were used, where questions were set in advance but the opportunity to follow-up questions existed. The questions were developed from the theories in the frame of reference and are presented below in this chapter. As the parents’ perception of the child’s influence was researched, semi-structured interview were suitable as it is flexible and beneficial. (Malhotra & Birks, 2007)

We prepared the interview by bringing the recording device, a copy of the questions for the interviewer, a premade answering sheet for every question for the observer, and we were dressed smart but not too dressed up. During the interview we thought of speaking clearly, not bombard the respondent with questions and not to agree with the answers but rather have a neutral facial expression. (Andersen 1990/1994)

When the session was over a question was asked if we could get back to the respondent via e-mail if any further questions arose during the analysis of the study. This was to open up for contact if needed after all the interviews if something needed to be explored further.

3.5

Questions

The questions for the interviews are shown below. We had two different sets of questions, one for Familyfood’s customers and one for non-customers. Every question is connected with the frame of reference and an explanation for why every question was asked is given. The interviews were held in Swedish and the original questions are attached in appendix 1. 3.5.1 Customers

The first three questions were to categorize the respondents according to the theories in the frame of reference. The children’s age was to categorize the children to be able to find differences between the two age groups two to six and seven to twelve. The age of the

parents was to find out in what generation they were in, and the education level to find out if there were any differences in how the children influence a decision when the parents have a higher or lower level of education.

1. What is the age of your children? 2. When were you born?

3. What level of education do you have?

Questions 4-6 were to gain background information about the parent’s connection to Familyfood.

4. For how long have you been a subscriber of Familyfood’s home delivery grocery bags? 5. How often do you receive a home delivery grocery bag?

6. Why did you start to buy home delivery grocery bags from Familyfood?

Questions 7-8 were to get an insight in the parents and the children’s perception of the food in Familyfood’s grocery bags.

7. What do you think about Familyfood and the meals? 8. What do your children think about the Familyfood meals?

Question 9 was to find out if there were any direct influences the children use when telling their parents how they like the food.

9. How do you find out what the children think about the food?

Question 10 was to find out if the children had influenced the parents indirectly before they decided to start buying the home delivery bags.

10. Did you think of what your children would think of the food before you started to buy the home delivery grocery bags?

Questions 11-13 were to gain an understanding for the food culture in the family. 11. How big is your interest for food in your family?

12. Do you have any special values regarding food in your family? 13. What are your routines during the meals in the evening?

Questions 14-16 were to find out indirect and direct ways that the children influence their parents and if the children are exerting legitimate power.

14. Are the whole family engaged in what food that is going to be bought and the cooking process? 15. Are your children engaged in the food process?

16.

a. Do you try to get your children engaged in your food purchase, if so, how do you do? b. Do you think it is important?

Question 17 was to see if the parents had any other thought and values regarding food and to let them think freely in order to find important facts that we might have missed out on with the above questions.

17. Can you tell me a little bit more about how you think around food?

Questions 18-19 were to find out how much influence the children have on their parents through indirect- and direct influence as well as coercive power (19 c and f). Question 19 b-f were also to get a better understanding of the parental styles and how they act in a situation where the children do not like the food.

18. Do you prioritize that your children like the food that you buy? 19.

a. How do your children react if they do not like the dinner in general? b. How do you react in that situation?

c. Are you cooking another meal for them then?

d. Do you always cook the same meal for the whole family? e. How do you think around that dish in the future? f. Do you avoid buying that food in the future? Why?

Question 20 a and b were to find differences in the amount of pester power the children use to get their requests fulfilled when it comes to the weeks with the grocery bag and the weeks without. 20 c was to find out to what extent the children use direct and indirect influence to affect the parents when it comes to keep subscribing the home delivery grocery bags. 20 d was to find out if the children are exerting reward power.

20.

a. Do you perceive that your children request for other dishes during the weeks when you are receiving home delivery grocery bags?

b. Does it occur more or less often with the home delivery grocery bag?

c. Have you considered ending the subscription with Familyfood due to that the children often request for other dishes?

d. Have your child ever promised to behave well in return to get a dish that she really likes? Question 21 was to find out if the children are exerting expert power.

21. Do you perceive that your children have more knowledge about certain food products than you? If so, do you take their knowledge into consideration?

Questions 22-23 were to get information about requests with a direct influence that is connected to pester power.

22.

a. How often do you perceive your children to ask for food products? b. Does your child repeat the same request more than once?

c. Have the requests increased or decreased with the age of your child?

23. Do you perceive that your children ask for products they have seen advertised on TV?

Question 24 was to find out if the children are influenced by their friends when it comes to food products and in their turn ask their parents for dishes their friends like.

24. Do your children request for food dishes that she has eaten somewhere else?

Question 25 was to find out direct influence and the differences between the different age groups to be able to connect it with pester power.

25.

a. How does your child propose the question?

b. Has the request approach changed by the age of your child? c. Does the request approach vary between your children?

Question 26 was to find out where the requests occur to be able to make connections between the place and direct influence.

Question 27 was to understand how much the parents yield to their children’s requests in different situations.

27.

a. How often do you perceive that you yield to the requests?

b. Do you yield more often to the requests by the increasing age of your child? c. Do you yield more often to requests regarding food than other products? d. Do you yield more often if the child requests more often?

Question 28 was to find out how the parent’s act when they say no to find out what parental style they are using and how they yield to a request.

28. When you do not yield to a request, how do you say no?

3.5.2 Non-customers

When we interview the non-customers the questions concerned the fact that they were current customers to Familyfood were excluded. Also one question was added, question 4, and one was adjusted, question 9. Question 4 was to gain background information about the respondent and her connection to home delivery grocery bags. Question 9 was adjusted and more sub questions regarding the grocery shopping was added, as the families without the grocery bag need to go grocery shopping more often.

4. a. Have you been a member of any home delivery grocery bags company? If yes:

i. What company?

ii. Why did you end your subscription? iii. For how long time were you a member?

iv. What did you think about the food? v. Did your children liked the food?

b. Have you thought of to be a customer to a home delivery grocery bag company? 9.

a. Are your children engaged in the food process?

b. Do you try to get your children engaged in your food purchase, if so, how do you do? c. Do you think it is important that your children are engaged?

d. Do your children join you to the store? e. Do they ask for products in store?

f. Do they ask for products that they have seen on TV when you are grocery shopping? g. Do they ask for products they have seen on TV in general?

3.6

Ethics

When we searched for respondents to our interviews e-mails were sent to everyone in Familyfood’s customer database in the Jönköping area. As mentioned before we wrote a presentation of ourselves in the e-mail and also an introduction of what the study was about. We did this so the respondents knew who we were and what the aim of study was before they agreed to participate (Trost, 2010). Before we started the interview with the respondent we explained once again the purpose of the study and who we were.

The respondents are anonymous, hence no real names were used in the thesis and no one other than the authors have access to the respondents’ personal information (Trost, 2010). During the interviews the respondents were asked if they agreed on that we recorded the