DISSERTATION

Ingrid From

Health and quality of care

from older peoples’ and

formal caregivers’ perspective

Health and quality of care

from older peoples’ and

formal caregivers’ perspective

DISSERTATION

Karlstad University Studies 2011:63 ISSN 1403-8099

ISBN 978-91-7063-402-4 © The author

Distribution: Karlstad University

Faculty of Social and Life Sciences Nursing Science

SE-651 88 Karlstad Sweden

+46 54 700 10 00 www.kau.se

Aim: The overall aim of this thesis was to gain a deeper understanding of older people’s view of

health and care while dependent on community care. Furthermore the aim was to describe and compare formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care, working conditions, competence, general health, and factors associated with quality of care.

Method: Qualitative interviews were conducted with 19 older people in community care who

were asked to describe what health and ill health meant to them and the factors that facilitated health or were obstacles to health. Data were analyzed using content analysis according to Burnard (I). The informants were also asked to narrate a situation when they experienced good and bad care respectively. The interviews were analyzed using the phenomenological method according to Collaizzi (II).

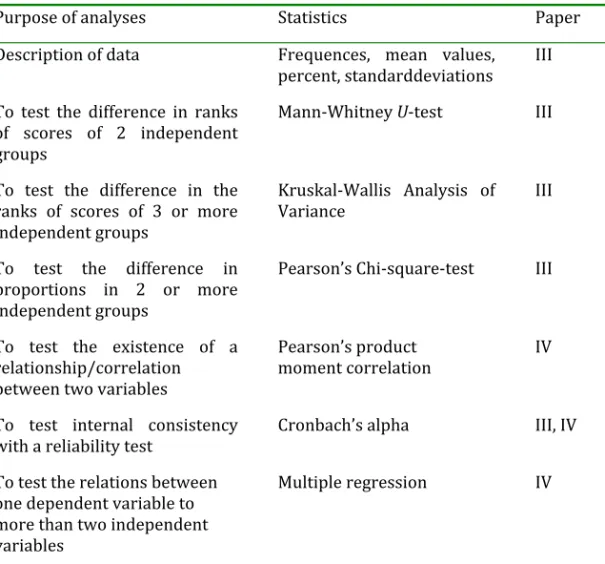

The formal caregivers; 70 nursing assistants (NAs) 163 enrolled nurses (ENs) and 198 registered nurses (RNs), answered a questionnaire consisting of five instruments: quality of care from the patient's perspective modified to formal caregivers, creative climate questionnaire, stress of conscience, health index, sense of coherence and items on education and competence (III). Statistical analyses were performed containing descriptive statistics, and comparisons between the occupational groups were made using Kruskal‐Wallis ANOVA, Mann‐Whitney U‐test and Pearson's Chi‐square test (III). Pearson’s product moment correlation analysis and multiple regression analysis were performed studying the associations between organizational climate, stress of conscience, competence, general health and sense of coherence with quality of care (IV).

Results: The older people's health and well‐being were related to their own ability to adapt to

and compensate for their disabilities (I). The experience of health and ill health was described as negative and positive poles of autonomy vs. dependence, togetherness vs. being an onlooker, security vs. insecurity and tranquility vs. disturbance (I). The meaning of good care (II) from the older people’s perspective was that the formal caregivers respected the older people as unique individuals, having the opportunity to live their lives as usual and receiving a safe and secure care. Good care could be experienced when the formal caregivers had adequate knowledge and competence in caring for older people, adequate time and continuity in the care organization (II). Formal caregivers reported higher perceived quality of care in the dimensions medical‐technical competence and physical‐technical conditions than in the dimensions identity‐oriented approach and socio‐cultural atmosphere (III). In the organizational climate three of the dimensions were close to the value of a creative climate and in seven dimensions the values were near a stagnant organizational climate. The formal caregivers reported low rate of stress of conscience. The NAs reported lower rates than the ENs and the RNs. The RNs reported to a higher degree than the NAs/ENs a need to gain more knowledge, but the NAs/ENs more often received training during working hours than the RNs. The RNs reported lower emotional well‐being than the NAs/ENs (III). The formal caregivers’ occupation, organizational climate and stress of conscience were associated with perceived quality of care, and explained 42% of the variance (IV).

Implications: The formal caregivers should have an awareness of the importance of kindness

and respect, supporting positive thoughts and help the older people to retain control over their lives. The nursing managers should employ highly competent and adequate numbers of skilled formal caregivers and organize formal caregivers having round the clock continuity (III). A possibility for developing competencies on working hours should have high priority in community care. The organizational climate and stress of conscience were reported to be related to quality of care, indicating that improvements in these areas are important for good quality of care and for creating dynamic and attractive working conditions (IV).

Keywords: community care, competence, dependency, formal caregivers, health, older people, organizational climate, quality of care, sense of coherence, stress of conscience.

Syfte: Syftet med avhandlingen var att få en fördjupad förståelse för äldre personers syn på hälsa

och vård när de var beroende av kommunal vård. Syftet var även att beskriva och jämföra de formella vårdarnas uppfattning av vårdkvalitet, arbetsförhållanden, kompetens, generell hälsa, samt faktorer relaterat till vårdkvalitet.

Metod: Kvalitativa intervjuer genomfördes vid tre tillfällen (I, II) med 19 äldre personer i

kommunal vård som ombads beskriva vad hälsa respektive ohälsa innebar för dem samt faktorer som underlättade respektive hindrade upplevelsen av hälsa. Datamaterialet analyserades med hjälp av innehållsanalys enligt Burnard (I). Informanterna ombads även att berätta om en situation där de upplevt bra respektive dålig vård (II). Intervjuerna analyserades med hjälp av fenomenologisk metod enligt Collaizzi(II).

De formella vårdarna; 70 vårdbiträden (VB) 163 undersköterskor (USK) och 198 sjuksköterskor (SSK) besvarade ett frågeformulär med fem instrument; kvalitet ur patientens perspektiv modifierat till vårdares perspektiv, organisationsklimat, samvetsstress, hälso index (III, IV), känsla av sammanhang och frågor om utbildning och kompetens (IV). Beskrivande statistik och inferens statistik användes och jämförelser mellan yrkesgrupperna testades med Kruskal‐Wallis variansanalys, Mann‐Whitneys U‐test och Pearson’s Chi‐två test (III). Pearson’s produkt moment korrelations analys och multipel regressionsanalys testades för variablerna arbetsförhållanden, kompetens, generell hälsa, känsla av sammanhang i association till kvalitet i vården (IV).

Resultat: De äldres hälsa och välbefinnande var relaterat till vilket bemötande de fick, deras

egen förmåga att anpassa sig till och kompensera för sin oförmåga (I). Upplevelsen av hälsa och ohälsa beskrevs som negativa och positiva poler: autonomi kontra beroende, gemenskap kontra utanförskap, trygghet kontra otrygghet och lugn och ro kontra en störande och orolig omgivning (I). Innebörden av god vård (II) var att de äldre av de formella vårdgivarna blev respekterade som unika individer, som gav möjlighet till de äldre personerna att leva sitt liv som de var vana vid, och att de erhöll en trygg och säker vård. God vård kunde upplevas då vårdarna hade adekvat kompetens och skicklighet, tillräckligt med tid och kontinuitet i vårdens organisation (II).

De formella vårdarna rapporterade högre upplevd vårdkvalitet inom dimensionerna medicinsk‐ teknisk kompetens och fysisk‐tekniska förutsättningar än i dimensionerna identitetsorienterat förhållningssätt och sociokulturell atmosfär (III). Organisationsklimatet var i tre dimensioner nära värdet för ett kreativt klimat och i sju dimensioner nära ett stagnerat klimat. De formella vårdarna rapporterade låg grad av samvetsstress. VB rapporterade lägre värden än USK och SSK. SSK rapporterade i högre grad än VB/USK ett behov av att få mer kunskap, men VB/USK fick oftare utbildning under arbetstid än SSK. SSK rapporterade lägre emotionellt välbefinnande än VB/USK (III). De formella vårdarnas yrke, organisationsklimat och samvetsstress var relaterat till deras perception av vårdkvalitet och förklarade 42% av variansen (IV).

Implikationer: Vårdarna bör ha en medvetenhet om vikten av vänlighet och respekt, att stödja

positiva tankar och hjälpa äldre att behålla kontrollen över sina liv. Ledare för vården bör anställa ett tillräckligt antal utbildade vårdare och organisera arbetet så att kontinuitet kan uppnås i vården dygnet runt (III). Möjligheter att utveckla vårdarnas kompetens under arbetstid bör ha hög prioritet. Eftersom organisationsklimat och samvetsstress rapporterades vara relaterade till vårdkvaliteten tyder resultatet på att förbättringar inom dessa områden är gynnsamt för god vårdkvalitet och positiva förändringar kan skapa dynamiska och attraktiva arbetsförhållanden (IV). Nyckelord: arbetsklimat, beroende, formella vårdare, hälsa, kommunal vård, kompetens, känsla av sammanhang, samvetsstress, vårdkvalitet, äldre personer.

List of publications 6 Abbreviations 7 INTRODUCTION 8 Community care in Sweden 8 Quality of care 10 Older peoples’ perceptions of quality of care 12 Formal caregivers’ perception of quality of care 13 Ageing and dependency 14 Health 15 Health among older people 17 Health among formal caregivers 18 Working conditions 19 Organizational climate 19 Stress of conscience 20 Rationale for the study 21 AIMS 23 METHODS 23 Paper I, II 24 Participants and procedure 25 Data collection 25 Data‐analyses 26 Trustworthiness 29 Paper III, IV 31 Participants and procedure 31 Data collection 32 Characteristics of the formal caregivers 32 Questionnaires 33 Quality of care 33 Working conditions 34 Organizational climate 34

Competence 36 General health 37 Sense of coherence 37 Data analyses, statistics and internal drop‐outs 37 Ethical considerations 38 FINDINGS 40 Paper I 41 Older people’s views on health and care 41 Health or ill health – a question of adjustment and compensation 42 Adjustment 42 Compensation 42 Subcategories 42 Autonomy vs. dependency 42 Togetherness vs. being an onlooker 43 Security vs. insecurity in daily life 43 Tranquility vs. disturbance 44 Paper II 44 The meaning of good care 44 Being met as a human being 44 Living life as usual 45 Receiving safe and secure care 45 Paper III and IV 47 Quality of care from the formal caregivers’ perspective and associated factors 47 Quality of care 47 Working conditions 49 Organizational climate 49 Stress of conscience 49 Competence 50 General health 51 Sense of coherence 51 Factors associated with quality of care 51

Discussion of results 52 Methodological considerations 61 The qualitative papers 61 The quantitative papers 62 Validity 62 Reliability 63 Conclusions, implications and future research 64 Acknowledgement 66 REFERENCES 68 PAPER I IV

List of publications

This thesis is based on the following papers, which will be referred to by their Roman numerals: I. From, I., Johansson, I. & Athlin, E. (2007). Experiences of health and well‐ being, a question of adjustment and compensation ‐ views of older people dependent on community care. International Journal of Older PeopleNursing 2, 278‐287.

II. From, I., Johansson, I. & Athlin, E. (2009). The meaning of good and bad care in the community care: older people’s lived experiences. Inter

national Journal of Older People Nursing 4, 156‐165.

III. From, I., Nordström, G., Wilde‐Larsson, B. & Johansson, I. Caregivers in older people’s care: Perception of quality, working conditions, competen‐ ce and personal health. Submitted.

IV. From, I., Wilde‐Larsson, B., Nordström, G. & Johansson, I. Formal care‐ givers’ perception of quality of care for older people – predicting factors. Submitted. Reprints were made with permission from the publishers.

Abbreviations

CCQ Creative Climate Questionnaire EN Enrolled Nurses EWB Emotional well‐being HI Health Index NA Nursing Assistants PR Perceived Reality PWB Physical wellbeing QPP Quality from the Patients Perspective RN Registered Nurses SCQ Stress of Conscience Questionnaire SI Subjective Importance SOC Sense of CoherenceINTRODUCTION

In recent decades, a great deal of research has been conducted focussing on older people’s health and care, and considerable variations have been found with regard to health problems in this group (Hellström & Hallberg 2001; Jakobsson et al. 2003; Borglin et al. 2005). It has also been found that care of older people can be of both good and bad quality (Haak 2006). Nursing is founded on the fundamental idea that care should be based on the needs and problems of the patient (Henderson 1997; Benner & Wrubel 1989). One starting point for high quality community care, should be to study how older people dependent on such care, describe their own experiences and perceptions of health, and good and bad care.

Quality of older people’s care is stressed in many countries as having high priority and being of major importance (SOU 2008:51). High aspirations for quality of care can be reflected in the goals for older people’s care in the communities, sometimes reachable and sometimes unreachable (SOU 2008:51). The older people who are cared for in the communities also have increasingly complex medical and nursing needs (Socialstyrelsen 2007). Accordingly, the overall impact is that greater demands are placed on formal caregivers’ professional skills and other resources in order to be able to provide good quality care (Josefsson 2006).

Community care in Sweden

Community care in Sweden is regulated by the law, the Social Service Act (SFS 2001: 453) and the Health and Medical Services Act (SFS 1982:763). The Social Service Act (SFS 2001: 453) stipulates that the social services should be available for all persons requiring help, based on democracy, solidarity, autonomy and integrity. This should promote each individual’s security, equality and active participation in society. The Health and Medical Services Act (SFS 1982:763) stipulates that the entire population should have the same access to health and care on equal terms, and that health care should be of

good quality. Furthermore, care should be easily available, be built on respect for the patient’s autonomy and integrity, and be carried out in consultation with the patient.

Responsibility for the care of older people in Sweden is divided into three levels (Socialstyrelsen 2007). Goals and directives for health care are determined by the government through legislation and economic governance. The county councils in each region are responsible for health and medical care. Each community, at the local level, has the responsibility to offer their residents housing and social services in accordance with the needs of older people (Socialstyrelsen 2007). In the community, registered nurses (RNs) have the highest qualifications in health care and are responsible for the medical assessment and the nursing care (Josefsson et al. 2007). When necessary, physicians are contacted for further assessment, on a consultative basis (Westlund & Larsson 2002). Furthermore, nurse assistants (NAs), and enrolled nurses (ENs), also provide care in the community (Socialstyrelsen 2007; SFS 2001: 453). In the following text the concept “formal caregivers” will be used for NAs, ENs and RNs.

Most of the care for older people in the community is carried out by NAs and ENs who have different educational backgrounds regarding length and content. Törnquist (2004) showed that 58% of NAs had a 10‐ or 20‐weeks course of training, and 12% had studied in the upper secondary nursing programme or in the social service programme. Twenty‐seven percent had no formal health‐care education. The ENs had either got their education in the upper secondary nursing programme or equivalent adult education in the community. Between 2005 and 2008 the Swedish government provided grants to various educational projects for NAs and ENs in the communities to develop quality and excellence of care for older people (Fahlström & Hellner 2010). It has been difficult to evaluate this as the local variations in education were vast, some are well‐educated and others lacking formal education. In

several studies (Josefsson et al. 2007, 2008; Karlsson et al. 2009) it was reported that RNs also had inadequate competence for their work in older people’s care. They reported a lack of formal education (specialist training in geriatric nursing) and education in many areas such as, for example, dementia and falls (Josefsson et al. 2007, 2008; Karlsson et al. 2009).

Quality of care

According to regulations from the National Board of Health and Welfare (SOSFS 2011:9) the management of health services should be organized in order to respond to high patient safety and quality of care promoting cost‐ efficiency. Quality of care is a relative and neutral term (Donabedian 1980) assessing if a certain property related to care exists and to what extent it exists. The definition differs in particular eras, cultures and societies and various stakeholders can assess the quality of care differently (Donabedian, 1980). The definitions can be based on practical episodes, assessment of benefits and costs (Övretveit 1992), structure, process and outcome (Donabedian 1980). In a review of the relevant literature, Donabedian (1980) formulated a model for quality of care based on patients’ preferences. The model comprised three parts which were related to each other; technical care, interpersonal care and amenities. Donabedian (1980) also presented standards and criteria to assess quality of care by measuring structure, process and result. The structural quality comprises all external prerequisites needed for the implementation of the services, for example human resources. The quality of process concerns the content of the work activities. The quality of result consists of the impact the services have on the customers. Good structural quality offers prerequisites for a high process quality, which in turn impacts on the consequential quality (Donabedian, 1980).

The concept ‘quality of care’ is multidimensional and complex and comprises different perspectives and levels (Wilde et al. 1994; Wilde Larsson 1999). Wilde et al. (1993) developed a theoretical model of patients´ perception of quality of care. According to the model, ‘patients’ perceptions of what constitutes quality of care are formed by their encounter with an existing care structure and by their system of norms, expectations, and experiences. From the patients’ point of view, quality of care can be looked upon as a number of interrelated dimensions which, taken together, form a whole. The content of this whole can be understood against the background of two conditions which could be labeled ‘the resource structure of the care organization’ and ‘the patient’s preferences’ (Wilde et al. 1993, page 40). The former is of two kinds: ‘person‐related’ and ‘physical‐ and administrative environmental qualities’. The patients’ preferences have both ‘rational’ and ‘human’ aspects. Within this framework, patients’ perceptions of quality may be considered from four dimensions of quality of care: the formal caregivers’ medical‐technical competence, the physical‐technical conditions of the care organization, the identity‐orientation approach of the formal caregivers, and the socio‐cultural atmosphere of the organization (Wilde et al. 1993).

From this theoretical model an instrument was created (Wilde et al. 1994) and later modified to the care of older people (Larsson & Wilde Larsson 1998). This instrument has been used in numerous studies of quality of care in different contexts and countries (Larsson & Wilde Larsson 2001; Wilde Larsson et al. 2005) as well as among ageing people in community care (Larsson & Wilde Larsson 1998; Wilde Larsson et al. 2004). The instrument has later been further developed in order to make it possible to study formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care (Larsson & Wilde Larsson 1998, Wilde Larsson et al. 2001).

For a positive development of older people’s care, it is important that the quality of care is continuously evaluated. The National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen 2009) has initiated an ongoing process to improve

health care, where data sources, methods and indicators have been developed enabling systematic national monitoring to increase quality of care.

Older people’s perceptions of quality of care

A considerable amount of research has been carried out on what constitutes good quality in the care for older people in a community setting (Ho et al. 2003; Puts et al. 2007; Bilotta et al. 2009; Hasson & Arnetz 2011). The following areas of good care are reported to be important for older people: to be respected as a unique individual, individual adjustment of care, influence on care; how and when they receive care, and from which formal caregivers (SOU 2008:51; Wilde et al. 1995), and possibilities for participation (Penney & Wellard 2007; Larsson & Wilde Larsson 1998). Wilde et al. (1995) and Larsson and Wilde Larsson (1998) found that older people rated most scales within each of the quality dimensions (medical‐technical competence, physical‐technical conditions, identity‐orientation approach, and the socio‐ cultural atmosphere) of the theoretical model of quality of care (see above) as important.

The National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen 2006a) compiled together results about the older people’s experiences of care from a number of local studies in nine communities in the south of Sweden. The so called Quality Barometer was measured between 1998 and 2005 (Socialstyrelsen 2006a). The response rate was between 60 and 80% in all years except 1998. The result showed that older people and their relatives generally considered the quality of care positively. The older people got help at appointed times and the times were kept by the formal caregivers. The formal caregivers got appreciation from the older people for their approach and treatment. However, a total of 4% were negative. The complaints on the quality of care were: not getting the help they were promised, not having influence over what kind of help they needed, how the care was carried out, lack of space for social interaction and that too many different people provided the care.

Formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care

When registered nurses working in various specialties including community care were asked what they thought was excellent care the following themes were mentioned: professionalism, holistic care, practice, and humanism (Coulon et al. 1996). Professionalism was using the knowledge in the specific profession. Holistic care involved treating a person as an integrated whole, not just caring for the physical body. The theme practice meant that the scientific principles should be implemented in competent nursing care. In a humanistic care nurses should use their personal qualities and intuitive knowledge to build relationships (Coulon et al. 1996). The Swedish Society of Nursing and the trade union for nurses in Sweden, singled out ten factors important for good quality of home care for older people (Josefsson 2010). These were 1) security, 2) health, participation and environment, 3) teamwork, 4) high level of nursing skills, 5) support to relatives, 6) safe use of medicines, 7) prevention of malnutrition, falls and pressure ulcers, 8) having the right to have aid, 9) zero tolerance for care damage and 10) documentation following the patient between different care organizations. In order to treat older people in the community according to their needs, collaboration was reported to be required between different professions in the team and across organizational boundaries (Josefsson 2010).

The society for formal caregivers in Sweden, called BraVå, has published quality standards for the care of older people (BraVå 2010). They describe the importance of good treatment and common values among formal caregivers individual care planning and that the older people should be provided activity and rehabilitation. Empirical findings based on the theoretical model of quality of care by Wilde et al. (1993) indicates that, on the one hand, formal caregivers rated the actual quality of care (PR) as lower than did the older persons themselves. This was particularly the case of the scales designed to measure the following quality

dimensions: the medical‐technical competence of the formal caregivers, the physical‐technical conditions and the socio‐cultural atmosphere of the environments. On the other hand, when it came to the subjective importance (SI) ascribed to the different aspects of care, the formal caregivers consistently scored higher than the older persons (Larsson & Wilde Larsson 1998).

Ageing and dependency

Ageing, according to Tornstam (2005), is a concept referring to a series of events consisting of changes or transformations. Every such change or transformation is described as a cumulative change of earlier conditions. These transformations are described as affecting the older people psychologically, socially and biologically (Tornstam 2005). There are many myths and stereotypes of ageing that reflect a negative attitude towards older people. One term used for this is ‘ageism’ named by Butler (1969) who described this as negative preconceptions about ageing groups which could lead to negative attitudes, such as low expectations of the older people’s abilities or viewing them as incompetent individuals in general (Midvinter 1991; Andersson 1997), leading to a negative treatment.

Many debates in gerontology have focused on the negative treatment of older people, arguing for another view of ageing, which could be associated with roles and activity, meaning that activity was desirable for older people since it created a sense of well‐being. Cumming et al. (1960) questioned this view and presented the disengagement theory and presumed that there is an almost genetical instinct to disconnect from society gradually, which is described as natural and connected with inner harmony from the older people’s perspective. Tornstam (2005) presented a continuation of this theory in the theory of gerotransendence which has influences from the psychological developmental model of Erik H. Erikson (Erikson & Erikson 1997). According to this theory older people develop maturity and wisdom, which leads to changes in their entire life perspective, shifting from a rationalistic,

materialistic view to a more cosmic and transcendental view. According to a study by Chinen (1989) older people could develop individually and freely when they had reached this level of gerotranscendence.

Dependency on care when ageing has been linked to a negative association with well‐being among older people (McKee & Samuelsson 2000; Ellefsen 2002; Strandberg et al. 2002; Hellström 2003). When older people are dependent on a formal caregiver, a power imbalance arises in the giver‐and‐ receiver relationship, with a weaker position for the older people. This may have negative consequences for the status and prestige of the older people (Dowd 1975). This negative status can also be experienced when the formal caregiver forces older people to do something he/she does not want to do, does not take appropriate action for them, or is ignorant of his/her cultural preferences (Guldbjerg Hejselbaek et al. 1999). Saveman (1994) showed that older people could be humiliated in many different ways but they were still loyal and positive toward their formal caregivers and tolerated the situation despite difficult circumstances.

Health

There are many diverse definitions and opinions on the concept of health (WHO 1958; Boorse 1977; Nordenfelt 1991). A commonly cited and debated definition was formulated by the World Health Organization in the 1950s, claiming that health is not just absence of handicap and disease, but a state of physical, psychological and social well‐being (WHO 1958). Today this definition has been expanded and includes a more holistic perspective (WHO 2011). In addition, at a conference in Alma Ata, a declaration was made stipulating that health is a fundamental human right and that inequality of health between countries and within countries is not acceptable (WHO 1978). Boorse (1977) worked with the development of a biostatical concept of health from a medical perspective. He claims that health means having normal function, with normality being the biological functions classified statistically according to age and sex. Nordenfelt (1991) described a holistic theory of

health, more like the current definition from WHO, which stipulates that a person is completely healthy if he can reach his goals in life, provided that standard circumstances are current. Within this person‐oriented health perspective, health is seen as the possibility of improving one’s quality of life or terminating one’s life with dignity. A subjective dimension of health according to Eriksson (1984) is ’well‐being’ and is described as a feeling of prosperity and pleasure, that is to say, it expresses a sense of the individual. The feeling is an inner feeling that is not observable. The concept of ‘ill health’ is likewise one with many dimensions (Boyd 2000; Hofmann & Eriksen 2001). There is a biological‐physiological dimension, seen as a disturbance in bodily functioning, that is, a disease with a diagnosis. From a cultural dimension, the disease, in addition to the diagnosis, is also given an adhesive cultural meaning. The expression for this is sickness. Ill health can also be discussed as illness based on a person’s experience and is often referred to as ‘feeling ill’ (Boyd 2000).

According to Antonovsky (1987) health and ill health can be described as a continuum. This is a salutogenic approach to a health perspective about how people handle stressful situations in life. Sense of coherence (SOC) consists of three components: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. Comprehensibility concerns the extent to which a person experiences internal and external stimuli as intellectually graspable i.e. that a person can understand and explain events in their lives. Manageability is about adaptability and the resources available at an individual's disposal to deal with different situations. Using these resources the individual can meet the demands of different stimuli. Meaningfulness involves challenges that a person feels to be worth emotional investment and commitment (Antonovsky 1987).

In several studies (Rennemark & Hagberg 1997, 1999; Ekman et al. 2002; Nygren et al. 2005), older people’s sense of coherence (SOC) was shown to be an important factor for experiences of health and well‐being. Persons with a stronger SOC seem to cope better with their living conditions and diseases than persons with a weaker SOC (Antonovsky 1987). A study by Høie (2004) showed that persons over 75 years who were cared for in the community and had a high SOC reported better health, i.e. had less subjective health problems, than those with a lower SOC.

Formal caregivers in community care reporting a strong SOC had fewer encounters assessed as being risks of being harmed in their work than colleagues with a weaker SOC (George 1996). Knowledge of this strength could be useful both when employing new formal caregivers and enhancing their safety (George 1996).

Health among older people

Health has a close connection to biological, psychological and social changes during ageing often implying a deteriorating health (Ebersole 2005). The proportion of older people who perceive their general health as good has increased although the number of older people who have long‐term illnesses has increased. The number of older people who have illnesses or conditions that impede their daily lives has diminished (Ebersole 2005).

The average life expectancy in Sweden has increased and in 2011 it was 79.71 years for men and 83.56 years for women (SCB, 2011). In total, the figures for older people over 65 years are 1,608,000 (17.4% of total population) and 491,000 (5.3% of total population) over 80 years. These figures are expected to be stable until about 2020 after which they increase more distinctly. In 2050 the proportion aged over 80 is expected to have doubled from turn of the century (2000: 453,000; in 2050: 903,000) (Sveriges kommuner och landsting 2008). The reason for this is explained by a decline in morbidity and

mortality from cardiovascular diseases brought about by on healthier lifestyles such as better diets and reduced smoking. Meanwhile, healthcare, drugs and working environments have improved while obesity and overweight have increased from 9 to 16% of the older population over 65 years of age (Sveriges kommuner och landsting 2008). General health among older people is reported to be associated with physical activity (Harris et al. 2009), increased independence (Landi et al. 2007), vitality and reduction of hospitalization (Kerse et al. 2005). Experiences of poorer general health among older people were related to less activity and avoidance of activities due to for example fear of falling and falls (Zijlstra et al. 2007).

Health among formal caregivers

Absenteeism due to illness among formal caregivers in the community is higher than among other employees in the community although this has varied somewhat in recent years (4.0% in 1997, 6.5% in 2006 and 5.8% 2007) (Sveriges kommuner och landsting 2008). Formal caregivers’ situation when caring for older people was described as facing overwhelming demands from the environment (Blake & Lee 2007) and many of them cannot manage to work more than part‐time (Gustafsson & Szebehely 2005). Formal caregivers may have to relate to severe psychological problems, aggression, and stressful working conditions under time pressure, all causing negative stress (Törnquist 2004). Gustafsson and Szebehely (2005) showed that 2/3 of the formal caregivers signed up as sick at one or more occasions during a year and that at least the same number went to work even though they considered themselves as ill and should have stayed at home. There was a close connection between the sickness absence rate and extent of fatigue.

Hasson and Arnetz (2008b) reported a difference in physical and emotional strain between formal caregivers in home‐based care and nursing homes, with the highest physical and emotional strain in nursing homes. The formal caregivers described transfers of the older people from and to different

locations and not having enough time for work tasks as strenuous (Hasson & Arnetz 2008b). Difficult working conditions could lead to somatic symptoms and experiences of fatigue (Häggström et al. 2004; Fläckman et al. 2008). An ergonomic intervention showed differences in musculoskeletal symptoms and physical mobility among community formal caregivers, with minor symptoms and better health among those who had a training program (Wu et al. 2010). Thus formal caregivers’ health was shown to be dependent on working conditions.

Working conditions

Organizational climate

'Climate' is a meteorological term for events which have been transferred to the social field, which then refers to the psychological conditions in an organization (Ekvall 1996a). The effect of the resources in the organization are weakened or strengthened dependent on which climate is prevailing (Ekvall 1990). Ekvalls’ (1996a) definition of organizational climate reads: 'Behaviors, attitudes and feelings that characterize life in the organization’ (p.5). The climate affects organizational processes such as cooperation between individuals, coordination between units and functions, problem solving, decision making, planning and follow‐up results (Ekvall 1996a). The climate has an impact on individual psychological processes such as learning, identification and motivation. The climate can be creative or stagnant (Ekvall 1996a).

According to Ekvall (1996a) climate includes ten dimensions concerning the organization's capacity for innovation and change. The dimension challenge contains organizational members' commitment and sense of business and its goals. Freedom was described as the independence of the behavior of people in the organization. Idea support is the way in which new ideas are treated. Trust is the emotional security in relations. Vibrancy describes the dynamics in organizations. Playfulness/humor implies that there is an easygoing, casual

atmosphere. Debate includes the extent to which there are meetings and collisions between the views, ideas and different experiences and knowledge. The conflict dimension describes the extent to which there is personal emotional tensions in the organization. How an organization is able to tolerate uncertainty is measured in the dimension risk taking. Idea time is the time you can use for the development of new ideas (Ekvall 1996a).

Fläckman et al. (2008) showed that important factors for good working conditions in the communities were experiences of encouragement, confidence and professional development. The formal caregivers experienced working climate as good when they got support from their colleagues (Häggström et al. 2004). Feelings of insecurity, different opinions about the care provided, not to be confirmed and let down was followed by the idea of leaving their job and looking for new opportunities for development (Fläckman et al. 2008). Karlsson et al. (2009) reported that there was a fuzzy line between social care and nursing. When the formal caregivers provided care they experienced both being appreciated and valued but they could also feel undervalued and frustrated. They were expected to be everywhere, know everything and solve problems but still not be visible. These kinds of conflicting demands could result in troubled conscience for the formal caregivers.

Stress of conscience

The concept of conscience has been described as a unit (Kukla 2002) but also as consisting of many parts, sometimes referred to as an authority or the 'voices' (Barresi 2002), warning signal, an asset or a burden (Dahlqvist et al. 2007). Conscience can be an asset when reflection can lead to development but it can be a burden when there is a considerable difference between the society’ s and an individuals’ own values. When a person does not follow his/her voice of conscience, troubled conscience occurs (Dahlqvist et al. 2007). This is also called stress of conscience (Glasberg et al. 2006). One’s conscience can come into conflict with ideologies, norms and practices in society (Jonsen

& Toulmin 1988). The conflict may arise between the person and society, between different individuals and even within a single person. Conscience includes the core values which are the frontier that can not be crossed without consequences for our moral integrity and conscience (Aldén 2001).

Formal caregivers who witnessed neglected care or were required to perform tasks beyond their capacity could suffer from stress of conscience (Glasberg et al. 2006; Juthberg et al. 2008, Gustafsson et al. 2010). They could have to deafen their conscience, leading to loss of wholeness, integrity and peace of mind (Juthberg 2008). To alleviate the sense of right and wrong may be necessary to enable formal caregivers to keep on working in older people’s care (Gustafsson et al. 2010). Formal caregivers, whose professional skills are utilized to the maximum seems to lay the blame for shortcomings in the care on themselves. Being aware of what constitute quality of care of older people and how work should be carried out, but being unable to do so because of resource deficits, gives the formal caregiver a bad conscience. The result for the formal caregivers may be aloofness from the older people, experiences of burnout, ill health and a diminished quality of care. Lack of support from their environment was characteristic for the group who experienced burnout and ill health (Gustafsson et al. 2010).

Rationale for the study

There are a great number of studies concerning older people’s health and well‐being. Most of them focus on ill health, disease and complaints by older people. However there are few studies in which older people’s own views of health and well‐being are described, especially when they are dependent on care in a community setting. There are a considerable number of studies on what does or does not constitute good care for older people, based on caregivers’ and older people’s own perceptions of the care given in different health care settings but a limited number of studies in community care. Thus there is a need to explore older peoples’ lived experiences of what good and bad care mean to them, when they are offered community care services.

In the literature it was illustrated that new and more complex demands, and strained working conditions for formal caregivers were factors reducing their ability to provide care of good quality. Few opportunities for the formal caregivers’ professional development, and perceived deterioration of personal health have been reported. The different formal caregivers (NAs, ENs and RNs) in older people’s care usually have different roles and may have different views concerning their work. An additional description and comparison of the formal caregivers’ quality of care, working conditions, competence and personal health is of interest to study.

Studies have also shown that many factors may influence quality of care. However, few studies have explored factors associated with quality of care as perceived by formal caregivers when caring for older people. According to studies using bivariate analysis working condition, competence, health, sense of coherence appear to be of importance. However, there are a limited number of multivariate studies which include these variables and their associations with perceptions of quality of care. Thus this is of importance to study.

AIMS

The overall aim was to gain a deeper understanding of older people's view of health and care while dependent on community care. Furthermore to describe and compare formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care, working conditions, competence, general health, and factors associated with quality of care.

The specific aims were to:

‐attain a deeper understanding of older people’s views of their health and well‐being while dependent on health care in the community (I)

‐explore older peoples’ lived experiences of what good and bad care meant to them when it was offered by community care services (II)

‐describe and compare the perception of quality of care, working conditions, competence and personal health among nursing assistants, enrolled nurses and registered nurses in older people’s care (III)

‐explore factors associated with formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care for older people’s care in the community (IV)

METHODS

This thesis is based on four papers and an overview is shown in Table 1. The data collection for paper I and II were conducted in 2003‐2004 in three communities in a county in mid‐Sweden and for paper III and IV 2008‐2009 in 14 communities in the same county.

Table 1. Overview of the studies; design, sample and research methodology. Papers Design Sample Data collection Data analysis I Descriptive Qualitative 19 selectively chosen older people from three communities Two individual semi‐structured interviews per person Qualitative content analysis according to Burnard II Descriptive

Qualitative Same as in paper I One individual semi‐structured interview per person Phenomenologic al analysis according to Collaizzi III Cross‐ sectional comparative A total of 431 formal caregivers: NAs =70 ENs=163 RNs=198 Background data Questionnaires: A modified version of Quality of care from the Patients’ Perspective Creative Climate Questionnaire Stress of conscience Health Index Questions on education and competence Descriptive and inferential statistics IV Cross‐ sectional explorative Same as in

paper III Same as in paper III and in addition the Sense of Coherence questionnaire Multivariate regression analysis

Paper I, II

An inductive, qualitative descriptive design was chosen to deepen the understanding of older people’s views on their own health and community

care services. The data was gained by means of open interviews and the phenomena under study evolved from these narratives.

Participants and procedure

Nineteen older people from three communities in central Sweden participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were: being 70 years or more, receiving care the past six months in the community, able to speak Swedish and having the ability to provide informed consent. In order to obtain variation of data, the criteria also stipulated that there should be variations in age, gender, civil and health status, and the received amount of care, housing and living in urban and densely populated areas. The informants were selected by a professional care‐ needs assessor, in each community. A total of twelve women and seven men, from 70 to 94 years, agreed to participate. Six informants lived in sheltered accommodation, thirteen informants lived in their own homes and sixteen lived alone. Fifteen of them had severe disabilities and, among these, twelve usually received help various times night and day. This included basic personal care and specific nursing activities, such as drug administration, wound care and/or social contact. Seven persons needed assistance only once or twice daily, usually with drug administration or by having some type of social contact with the formal caregiver.

Data collection

Data was collected with qualitative interviews (I, II). In total, 57 interviews were conducted with 19 informants. Two interviews per informant were conducted in study I and one interview per informant in study II. In order to create a relaxed atmosphere, the interviews were carried out in the informants’ homes, without external distractions. Sufficient time was allotted before the beginning of each interview, to ease a potentially tense situation. This also provided time for the interviewer (IF) and informants to get acquainted with each other, by discussing everyday matters. Most of the

interviews lasted for approximately one hour. All interviews were tape‐ recorded and transcribed verbatim by the author (IF).

In study I, the informants were asked to begin their first interview by describing the meaning of health to them, using themes from an interview guide. This included: health vs. illness/sickness, well‐being vs. ill‐being, factors facilitating vs. obstacles to health/well‐being. The reason for choosing opposite themes was to obtain rich data by comparing and contrasting perspectives (cf. Meleis 1984). When the informants had difficulty in expressing themselves in words about what health and ill health meant to them, synonyms were used to modify the questions for health/ill health such as feeling well, feeling bad, etc. (cf. Nordenfelt 1991). Questions were further asked in order to clarify answers and obtain deeper understanding, e.g. ‘can you tell me more about that’ or ‘can you give an example’. Two‐three weeks following the first interview, the second interview was carried out with the aim of validating and deepening the data obtained from the first interview. The second interview started with a short summary from the first interview, which the informants were asked to confirm or correct. They were also encouraged to further deepen their reflections about the topic under study. At the end of the second interview (I), the participants were asked to prepare themselves for study II by reflecting on situations they had been involved in concerning good and bad care. In the interview that followed after ca two weeks, the informants were asked to narrate these experiences. Follow‐up questions were asked to achieve a deeper understanding of the content, and to avoid unclear statements.

Data analyses

The analysis of study I was carried out with qualitative content analysis (Burnard 1991, 1996). Content analysis was initially a systematic quantitative method used to describe manifest content of communication (Berelson 1952). The use of this method has later expanded to include the qualitative approach

(Morgan 1993; Graneheim & Lundman 2004). Even though different philosophies and methods are used in qualitative content analysis, the main goal is to find similarities and differences that form patterns in data by analyzing the texts (Burnard 1991, 1996; Graneheim & Lundman 2004; Berg 2007).

According to many researchers (Downe‐Wambolt 1992; Morgan 1993; Burnard 1995; Berg 2007), describing data from texts is not entirely free from interpretation and this is always the case, whether the analysis is manifest or latent. In the present study, Burnard’s method of content analysis was chosen, as this method seemed useful for a deep analysis of data (Burnard 1991, 1995, 1996). 1. Firstly, the interviews were read through to get a sense of the whole. The informants gave the immediate impression that they talked about health and ill health as intertwined. They seemed to fuse experiences such as feeling bad and good, the meaning of a good or bad life and how to achieve a good health. The interviews were read again, statistically significant words and phrases about experiences of health and ill health were marked, separated and coded. The second interview proceeded from the summary of the written content. Issues that were unclear were noted and these were discussed with the informants to give them the opportunity be able to clarify their previous comments.

2. In the second step the two interviews were merged and treated as a whole. After reading the text once more the first codes were merged together and reduced.

3. In the third step categories were named. Different relations were identified between categories and they were sorted into subcategories and main categories. The underlying meaning as found in the categories formed the main category.

4. Codes and categories were compared with each other and with the text from all the interviews. The categories were discussed many times among members of the research team and the analysis continued until the team reached consensus. Thereafter, the text explaining the content of the findings was written.

In study II data was analyzed using a phenomenological method by Collaizzi (1978). Phenomenology is a philosophical theory and research method and the purpose is to describe phenomena; how things appear to human beings as lived experiences (Bengtsson 2005). This approach ‘to go to the things themselves’ is not to take scientific ideas for granted but to examine human experience and the whole variety of it, to do justice without prejudice and to be aware of pre‐understandings (Morse 1991; Dahlberg et al. 2001; Bengtsson 2005). The strength of this approach lies in having ‘a natural attitude’ which is having a consciousness directed to the world, and being totally focused on the experienced phenomenon. Phenomenology starts with the concrete ‘lived experience’ in the ‘life world’. In the procedure of reflecting and analyzing lived experiences, pre‐understandings cannot be entirely put aside, since this involves the interpretation of data as a background, which helps us to understand the phenomenon under study (Bengtsson 2005). It is crucial to remain open during this procedure and to reflect over the lived experiences told by the informants (Dahlberg et al. 2001; Bengtsson 2005). In this study, Collaizzi’s (1978) interpretative phenomenology method was chosen, as this is in agreement with our opinion about how one can use pre‐understandings (see discussion) in phenomenological studies.

The analysis followed the steps described below.

1. The interviews were read many times to obtain a sense of the whole. 2. Statements that were significantly attached to the phenomenon under

investigation were extracted from all the texts. After identifying differences and similarities in experiences of care that is good and bad, the statements were contrasted and compared.

3. Significant statements formed the formulated meanings. The researcher needed creativity to find formulations of the meanings hidden in the studied phenomenon. Good and bad care were in this stage found to be opposites to each other and the understanding of a description of good care was understood by their description of the opposite state.

4. The meanings that were formulated were arranged into themes and sub‐ themes in this stage. The decision was taken to label the sub‐themes and themes. An understanding of the meaning of good care for the informants was the basis for the understanding of good care and illuminated bad care as the opposite. Validating the themes, a continuous comparison to validate

the themes was made between the themes and the transcripts. The text was reviewed again when discrepancies were found.

5. The findings of the phenomenon were integrated into a comprehensive description. This stage finally completed the organization of the themes. 6. Through reflection and creative understanding the fundamental structure

of the phenomenon was formulated.

Trustworthiness

In qualitative research, trustworthiness is sought and described in criteria as credibility, auditability and fittingness (Beck 1993). Credibility is a measure of vividness and faithfulness of the described phenomenon and the informant and readers should identify it as their own experiences. Credibility was strengthened because the informants were describing their own reality of health and ill health (I) and of being dependent on care (II). Obtaining valid data also depends on the relationship between researcher and informant (Sandelowski 1986). Therefore, all interviews were carried out in as relaxed and familiar an atmosphere as possible and the interviewee was supportive and open (I, II). The second interview (I) also enhanced the credibility of the findings, since informants were able to validate the findings from the first interview (Sandelowski 1986). To assure credibility in the second study, follow‐up questions were continually asked during the interviews for validation. In the analysis for Paper II, Collaizzi’s (1978) steps were followed,

with the exception of the seventh which involved asking the informants about their own judgments of the findings.

To ascertain auditability means that another researcher should be able to follow the same steps used in former research and make a replication of the analysis. A tape‐recorder was used and the interviews were transcribed verbatim, so that nuances in the statements could be analyzed (I, II). An interview guide was used (I) to keep the informants within the framework of the subject (cf. Beck 1993). In order to preserve the meaning of the phenomenon, as intended by the informants, the authors tried to remain close to the data during both the analysis and presentation of the findings. Pre‐ understandings were put aside and bridled as much as possible. In order to avoid over‐interpretation, the authors discussed the categories and subcategories thoroughly and made comparisons with the text of the interviews. The interviews were interpreted and discussed among members of the research team until consensus was achieved. To further increase the auditability, the methods of analysis were strictly adhered to and the research process was followed as accurately as possible. The findings were underpinned by quotations (I, II) (Lincoln & Guba 1985).

Fittingness was how the result could fit in another context similar to the one from where the data were generated. To fulfill the criteria of fittingness the choice of informants varied greatly. Since all were dependent on care and could describe situations from that viewpoint, they were judged to be representative (Sandelowski 1986; Beck 1993). The fittingness was strengthened by the careful descriptions of the informants and the study setting, as well as a rich description of the findings. This makes it possible for the reader to judge whether the findings are transferable to other contexts.

Paper III, IV

Papers III and IV were quantitative cross‐sectional studies. A descriptive and explorative design was used for studying formal caregivers’ perception of quality of care, working condition, competence and own health as well as factors associated with quality of care.

Participants and procedure (III, IV)

Papers III and IV were authorized by the executive managers in older people’s care in one county in Sweden to address the NAs, ENs and RNs in community care. Subsequently, the managers of the units in charge of the NAs/ENs and RNs were contacted by IF. Each manager informed potential participants about the study. The unit manager provided a list to the first author with names and addresses of the formal caregivers. Random numbers were used to make a choice of respondents of NAs and ENs from these lists. All RNs were invited to participate in the study. The coded questionnaire was sent to the potential participants together with information about the aim of the study and a pre‐addressed envelope. Participation in the study was accepted by returning the completed form. With two weeks in between, two reminders were sent out to those who had not returned the questionnaire. Table 2 below shows the participants in paper III and IV. Table 2. Eligible number, sample and participants of formal caregivers. Total n (%) NAs n (%) ENs n (%) RNs n (%) Eligible number of formal caregivers 5481 1767 3421 293 NAs and ENs (random sample) and

RNs (total sample) 757 140 324 293 Participants/respons rate 431(57) 70 (50) 163(50) 198(68)

Data collection

Characteristics of the formal caregivers

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the sample. The average age of the formal caregivers was 48.2 years. They had worked 10.2 years in their current workplace. Most of the participants were women. The majority of the formal caregivers worked in institutions for older people. Their work time in older people’s care was 18.3 years. Of all the formal caregivers 28 (7%) had no health‐care education (not shown in the table). Table 3. Formal caregivers in older people’s care – characteristics of the sample. Total n=431 Age years M (SD) n=430 48.2 (10.5) Years in current work place M (SD) n=392 10.2 (8.5) Sex n (%) n=431 Women 411 (95) Men 20 (5) Occupation n (%) n=431 NAs/ENs 233 (54) RNs 198 (46) Working place n (%) n=420 Home help service 63 (15) Institutions for older people 336 (80) Home help service and institutions 21 (5)