FOOD FOR CHANGE

Exploring rural-urban linkages among youth in Guatemala

Clara Axblad

Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits First semester 2018 Supervisor: Tobias Denskus

ABSTRACT

As the world grapples with increasing urbanization, population growth, climate change and depleting natural resources, there is an increased recognition that more food will have to be produced with fewer resources while food consumption has to shift rapidly towards more sustainable patterns. Meanwhile, although many are willing to work in and innovate agricultural practices, young people in rural areas still struggle to access the resources needed to be part of this shift, not to mention to make a living. In Guatemala, more than 90 % of young people engaged in agriculture work in the informal sector. In such a context of insecure labour conditions combined with strong vulnerability to climate change and natural disasters, migration to cities or abroad is often a result of push rather than pull factors.

Through an inductive methodological approach based on qualitative interview research with a small yet broad sample of stakeholders, this study explores the potential of rural-urban linkages to help strengthen opportunities for rural youth in Guatemala. By supporting information exchanges on the value of local small-scale food production and conscious consumption, it also aims to promote sustainable development in a broader sense. Four areas of inquiry are investigated with the goal of generating evidence-based recommendations on framing, messaging and channels that could be used as a foundation to build on when promoting local produce in urban and peri-urban markets. Interviewees agree on the importance of agriculture and many see a need for raising awareness on the value of local small-scale food production for advancing all dimensions of sustainable development. This coincides with a broad interest within a limited test group for accessing such information. Suggested communication channels range from social media via branding to goodwill ambassadors. Messaging should be short and impactful and focus on mutual benefits for producers and consumers, including for personal health and community development. Local food is believed to have a particular potential to promote perceptions of a common identity, supporting efforts to tackle historical and current barriers for linking urban and rural areas closer together.

Future research could look at successful initiatives to strengthen rural-urban linkages among youth, as well as on the increasingly porous borders between rural and urban areas and identities. Reassessing classifications of rural producers and urban consumers could hopefully contribute to more circular and sustainable models of development.

Key concepts: rural-urban linkages, decent rural employment, local small-scale food production, conscious consumption, communication for development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study exists thanks to the tireless support from colleagues and friends at FAO headquarters in Rome and in the FAO Guatemala office, their local partners and contacts. We ideated the research topic together, and the organization of the fieldwork relied on their full support. Without their attentiveness, creativity and flexibility, an agenda as comprehensive and rewarding as the one carried out during the two weeks in Guatemala would not have been feasible. The same is true for the interviewees, whose availability, engagement and enthusiasm for the themes of research provided inspiration and encouragement far beyond the provision of data.

CONTENTS

Abstract 1

Acknowledgements 2

Contents 3

List of tables and figures 3

1 INTRODUCTION 4

1.1 Rationale and aim 4

1.2 Research design and questions 5

1.3 Structure 6

2 CURRENT RESEARCH 7

2.1 Youth and agriculture 7

2.2 Introducing rural-urban linkages 8

2.3 Communicating for Development 8

2.4 Guatemala: the context 10

3 METHODOLOGY 13 3.1 Approach 13 3.2 Interview research 14 3.3 Analysis 16 3.4 Limitations 17 4 ANALYSIS 18

4.1 Rural versus urban life and work and related challenges 18

4.2 Rural versus urban youth 22

4.3 Motivations and habits of food consumption and perceptions of local produce 25 4.4 Information interest, effective messaging and communication channels 28

5 CONCLUSIONS, REFLECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 31

5.1 Conclusions 31

5.2 Reflections and recommendations 33

References

Appendix I: Focus Group Guide - Urban Appendix II: Focus Group Guide - Rural Appendix III: Interview research

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Figure 1: Rural and urban population in Guatemala, 1990-2017 Table 1: Focus group participants

Table 2: Examples of rural-urban linkages – Coffee Camp Table 3: Examples of rural-urban linkages – Los Encuentros

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Rationale and aim

Today more than half of the world’s inhabitants live in cities. In 2050 – the same year as the global population is expected to hit 9.8 billion – the share could be 68 %. While poverty still dominates in rural areas, cities are often marked by sharp inequalities. Large numbers of urban dwellers struggle to access basic services especially in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, where urbanization trends are the highest. (UN DESA, 2018; UN DESA 2017; UN-Habitat, 2017).

Meanwhile, global and interlinked phenomena such as unsustainable consumption patterns, climate change and population growth are increasing the pressure on natural resources, including those that feed us. Today enough food is produced to feed everyone, yet more than 800 million people go hungry; and the number is rising, mainly due to conflict, climate change and persisting inequalities (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO, 2017). With a growing population and depleting resources the world will have to produce more food with less inputs, while continuing to address inequalities and ensure global food security. There is increased awareness that this will require greater support for young people to engage in agriculture and food production, allowing them to innovate in order to produce more in more sustainable ways, and to access markets with their produce.

This study explores the nexus of sustainable development, rural-urban linkages and conscious food consumption among youth by looking at the example of Guatemala, with a particular focus on the potential of communication measures to promote constructive change. It builds on the knowledge generated within the Guatemalan edition of a rural development programme of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Integrated Country Approach (ICA) for

promoting decent rural employment, and in particular through a specific Communication for

Development (ComDev) project which included the development of a digital platform for young family farmers and rural entrepreneurs called ChispaRural.gt – or ‘rural spark’.

The study seeks to contribute to broadening the opportunity base for this new generation of food producers by gathering knowledge on the perceptions and motivations that frame views of rural versus urban life and work, with the overarching aim of promoting rural-urban linkages, including the access of rural youth to urban markets. More specifically the goal is to generate evidence-based recommendations on framing, messaging and channels that rural youth and development partners could use when promoting local small-scale produce in urban and peri-urban markets.

The relevance of this approach in Guatemala is illustrated by an extract from the last key-informant interview, carried out over lunch in Guatemala City with one of the young founders of the Guatemala branch of the Latin American social movement Socialab:

“So also in Guatemala we had to define our main innovation challenge. (…) we realized that one which is central to this country and which is transversal at the historical, geographical, political, economic and cultural level, is the topic of territory: how development has been planned in function of territories. (…) this is a country founded as a Spanish colony, that centered all its attention – institutional, political, economic, cultural – in the capital. When you travel you see that there is still great centralization of all services, opportunities, technologies, information, access to financial resources, state support, companies, industry, in the capital.

So how do we turn this around? (…) There are loads of rural development initiatives, there are social movements, there is the FAO and the state agencies (…). And in urban settings it’s the same, (…) So this is the connection with your field of study, that really the problem lies in the relation between rural and urban development: we’re eating this soup, and inside it there are loads of linkages between the countryside and the city.” (key-informant 5).

This study explores the potential of such rural-urban linkages to help strengthen opportunities for youth to engage in rural work more in line with their needs and aspirations, but also to promote sustainable local, regional and national development in a broader sense by supporting awareness-raising on the value of local production and conscious consumption. The approach builds on findings that, regardless of persistent trends of migration and urbanization, there is still a willingness among young people to engage in agriculture and food production – as long as access is provided to necessary resources, services and incentives (Melchers & Büchler, 2017; Leavy & Hossain, 2014; Pafumi, 2017). This, as we shall see, is rarely the case in Guatemala; yet still there is evidence of resources in the shape of energy, engagement and initiatives among young people that provide an invaluable foundation to build on.

1.2 Research design and questions

The core themes of this study – rural-urban linkages and their relation to sustainable development, the focus on youth, the challenges of rural work, and the role of communication in development – are all subject to significant attention in academic research as well as in both development discourse and operations. Although the aim and approach of this study build on these areas of research, as the intention here is to explore new terrain in relation to a specific project, the research approach is inductive and exploratory rather than aimed at testing specific theories or assumptions.

The empirical research is wholly qualitative and consists of interview research with focus groups, key-informants and intercept interviewees. It engaged a wide range of stakeholders, including groups of young professionals and students from urban and rural areas and key-actors from the civil society, private sector, government offices and international development agencies.

To address the core themes, a light analytical framework based on four main areas of inquiry was developed to guide the empirical research. Each area includes a set of guiding interview questions, slightly different for urban and rural youth respectively. While the full set of questions are provided in appendices I and II, an overview of the four areas and main queries are presented here:

1) Rural versus urban life and work and related challenges

Unpacking relations to and perceptions of the work and life of ‘the other’, as well as of the importance of mainly rural work in agriculture and food production for development. 2) Rural versus urban youth

Exploring perceived differences and similarities between the own group and the other. 3) Food consumption motivations and habits and perceptions of local, small-scale produce

Discovering underlying knowledge, assumptions, priorities and values that drive food consumption patterns.

4) Information interest, effective messaging and communication channels

Exploring the interest to learn about local food production and products, and identifying the communication channels and messaging which could generate most impact.

An important objective of this study is to contribute to the work already carried out by FAO and partners in Guatemala. Apart from this thesis, the degree project will therefore include an operative brief in Spanish with recommendations emerging from the research. The research was developed in close collaboration with the ComDev team at FAO Headquarters in Rome, with support from the FAO country office in Guatemala. In fact, the main theme of rural-urban linkages among youth was identified together with FAO colleagues as an area of research that could contribute to the development of the decent rural employment portfolio and its ComDev elements. Findings such as the interview extract above have confirmed the relevance of this approach and helped nuance it further.

1.3 Structure

The following chapter adds background by providing a selective overview of current research on the core themes of this study as well as an overview of the development context in Guatemala. The methodology is then presented in more depth. In the following analysis chapter the findings of the empirical research are divided into sections based on the four main areas of inquiry presented above. The paper ends with conclusions, reflections and recommendations for further research.

2 CURRENT RESEARCH

2.1 Youth and agriculture

In a context where global issues localize and local problems globalize in ways that are increasingly challenging to untangle (see e.g. Eriksen, 2014), the difficulties of young people to sustain rural livelihoods in one part of the world is gaining attention on political agendas in far away places, including in international development cooperation. In 2017, youth employment in rural areas became a centerpiece of the collaboration between the G20 and Africa (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2017), while economic opportunities for youth was identified as one of four strategic areas of the partnership between the European Union and the African Union (European Council of the EU, 2017).

These advances coincide with urbanization growing faster than many cities can sustainably absorb, especially in developing countries. The big majority of the world’s poor still live in rural areas, and a high proportion of those moving to cities are people under 35 years searching for better opportunities (UN-Habitat, 2017). At the same time, urbanization, population growth and depleting resources call for more innovative and productive agricultural practices, especially among smallholder farmers who still provide 80 % of the food produced in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (CFS, 2016). Decision makers are increasingly aware that global food security will depend on engaging youth in this shift (Leavy & Hossein, 2014).

Meanwhile, new research is challenging the widespread idea that young people are reluctant to work in agriculture. A recent study involving more than 10,000 young people in rural areas of Africa interviewed via sms show that 23 % of those aged 18-35 would like to work in the agriculture and food sector, making it the second most attractive area of work after government. Yet as noted in the introduction, this willingness depends on some important conditions, including options to apply technology, opportunities for investment, fair pay, training programmes, access to land, and enhancing the reputation of the sector. Unsurprisingly, these same conditions have been promoted in rural transformation policies in Europe for decades (Melchers & Büchler, 2017).

These findings partially align with those of the study Who wants to farm? by Leavy and Hossain (2014), which involved a smaller sample of 1,500 young people but applied a broader range of interview techniques and covered countries in three regions: Africa, Asia and Latin America, including Guatemala. The widespread access among youth to new information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the consumption desires spurred by these were found to deeply influence professional aspirations. While traditional white-collar jobs are still considered to bring higher status and quality of life, with the right attention and support to allow young people to embark on cash-based agribusiness rather than subsistence farming, agriculture still has the potential to fulfill these aspirations (Leavy & Hossain, 2014: 26, 38 ff.). Interestingly, Leavy and Hossain (2014: 40 f.) also list access to markets, as well as improving the status of agricultural work – e.g. by sharing experiences

from successful role models – among the main conditions brought up by young people for making agriculture more attractive.

2.2 Introducing rural-urban linkages

Access to markets is one of several issues that spur a growing realization in the global development discourse that rural and urban development can no longer be treated separately. Rural-urban linkages and territorial development are increasingly recognized as key to ensuring sustainable development in both settings (UN-Habitat, 2017). In fact, “Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning” is one of the targets under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 on Sustainable Cities and Communities (UN, 2018). According to UN-Habitat (2017), such linkages “include flows of agricultural goods, services and other commodities from rural-based producers and small holders to urban markets” while “Flows of information and ideas between rural and urban areas include information on markets (such as price fluctuations or changing consumer preferences), (…) but also social exchanges.”.

As many as 45 % of the interviewees in the sms-study stated that they live in both rural areas and cities, indicating that rural-urban flows are more multidirectional and dynamic than expected (Melchers & Büchler, 2017). Developing functional linkages that facilitate the movement of people, goods, services and ideas between rural and urban settings and contribute to the sustainable development of territories as a whole (UN-Habitat, 2017) become even more imperative in such a reality.

Leavy and Hossein (2014) extend their research on perceptions of agriculture also to urban and peri-urban areas. While the image of farming as hard and poorly rewarding seems to pervade in all settings, also in urban areas evidence suggests that this might depend more on perceived difficulties in accessing resources than on a lack of interest for agriculture. In fact, under the right conditions it could be an attractive alternative even for those who have been deceived by the options available in competitive, crowded urban settings (Leavy & Hossein, 2014: 24 ff., 38 ff.).

2.3 Communicating for Development

For development to be sustainable, it has to be based on the needs and participation of those it is supposed to benefit. This, in short, is the basic assumption for integrating the field of Communication for Development (ComDev) in development work. Such a shift requires research on the paradigms upholding dominant approaches of one-way, top-down, usually north-south development design and communication channels and on ways to change this. It also calls for concrete tools to promote participatory development through multi-directional communication. ComDev is the multidisciplinary field of theory and practice that attempts to provide such insights and solutions in support of sustainable social change (see e.g. Tufte & Mefalopulos, 2009).

or, ideally, a crosscutting theme of development programmes rather than a stand-alone objective. With its emphasis on multi-directional communication and participation, ComDev can be seen as particularly relevant in rural settings – both to support access to ICTs where these have traditionally been scarce, and to promote the constructive use of ICTs to enhance participation of marginalized populations. With its focus on rural development, FAO is in fact among the UN-organizations with the longest history of integrating ComDev approaches (FAO et al, 2005).

Clearly, sustained participation in development or social change in any society does not flow from development programming or social initiatives alone, not even when they integrate participatory communication. It is dependent on an enabling political environment with independent media and an educational system that promotes citizen empowerment and engagement in society. In fact, the participatory approach has faced multiple criticisms including that it often remains a top-down intervention rather than a bottom-up request from participants, its time-consuming nature, the difficulties in measuring its results, and the frequent lack of consistency between rhetoric and practice (Leeuwis, 2004: 57, 248 f.).

In order to embrace the vast spectrum of enabling factors needed to support social change, ComDev has developed to cover a number of inter-related areas. While recognizing the frequent overlap between them, Lenni and Tacchi (2011: 17 f.) discern four strands of ComDev:

▪ Behaviour change communication: aiming mainly at promoting changes in individual behaviour.

▪ Communication for social change: the main participatory approach, where

participation is often a goal per se in order to empower people as agents of change. ▪ Communication for advocacy: fostering an enabling environment for development

by advocating for changes in power relations, government and institutions. ▪ Strengthening an enabling media and communication environment: promoting

freedom of speech, an independent media system and broad and equal access to media channels.

This outline is useful as it helps to clarify the dimensions of ComDev addressed in this study. Focus is arguably on the first strand, as the goal is to create a knowledge base for developing and spreading messaging around the value of local, small-scale produce – with the objective of influencing consumer behavior. Also the second strand is relevant as all evidence is gathered through a participatory approach rather than based on pre-defined marketing theories. The third strand is relevant to some extent, as the conclusions and recommendations of this study will hopefully reach relevant policy makers through the FAO staff and partners to whom it is primarily directed.

2.4 Guatemala: the context

2.4.1 Demographics and development

Located in the northern part of Central America, Guatemala is about the size of Portugal yet with a significantly bigger population – approximately 17 million. A new national census is being held in 2018, but until it is concluded all population estimates are based on the last census from 2002 (Álvarez, 2017). Guatemala is a heavily centralized country. Approximately one third of the population lives within the metropolitan area of the capital, Guatemala City. The second biggest city, Quetzaltenango, holds just above 130,000 inhabitants (Wikipedia, 2018).

Guatemala’s population is among the youngest in the western hemisphere, with 28.6 % – approximately 4.6 million people – between 15 and 29 years of age in 2017. Migration abroad is very common and USA holds the biggest diaspora estimated to 0.5-1.5 million Guatemalans. The indigenous share of the population of approximately 40 % is among the highest in Latin America. (FAO Guatemala, 2017b; Wikipedia, 2018).

Despite being the biggest economy in Central America and having among the strongest economic growth rates in Latin America during recent years, Guatemala is still ranked as one of the most unequal countries in the region. The rates of poverty, malnutrition and maternal-child mortality are among the highest in Latin America, with peaks concentrated in rural and indigenous areas (World Bank, 2018). Guatemala is listed number 125 on the UN’s Human Development Index (UNDP, 2016). 2.4.2 Agriculture and youth employment

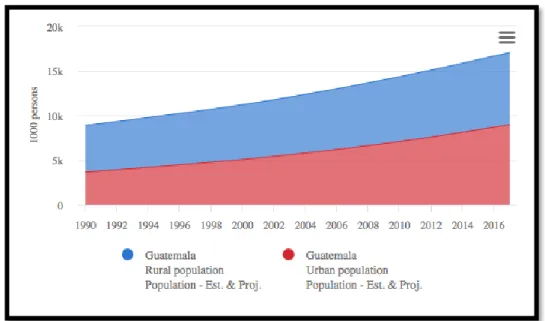

Regardless of a steady urbanization trend (see figure 1 below), 47.5 % of Guatemalans still live in rural areas (FAOSTAT, 2018). Although agriculture is the sector that provides the most employment, occupying 29 % of the population (World Bank, 2017), it stands for only 14 % of the GDP, showing on low production levels (Pafumi, 2017). A high occurrence of land disputes and ineffective mechanisms to resolve them discourage investment and hamper the potential of agriculture to advance development. Land distribution is unequal with a few landowners holding nearly two-thirds of the agricultural land. Tenure rights are insecure and remain one of the main causes of poverty among indigenous groups (USAID, 2018). More than half of rural households engaged in agriculture suffer from a lack of land and/or work in conditions of subsistence farming. Almost 40 % work in precarious conditions (Pafumi, 2017).

Figure 1: Rural and urban population in Guatemala, 1990-2017

Source: FAOSTAT (2018)

Amongst young people aged 15-29, the share living in rural areas amounts to 50 %. Of these, almost half work in agriculture (including livestock, forestry and hunting). Agriculture is one of the biggest sources of youth employment also when counting with the total population, employing 29.6 % of the economically active youth. As many as 91.5 % work in the informal sector under insecure conditions and often earn less than half of the national minimum wage. Of the large majority working for an employer only 5.6 % hold a contract and only 4.6 % have access to social insurance (FAO Guatemala, 2017b). Under such circumstances, migration to cities or abroad is often a result of desperation rather than active will (FAO in Action, 2018).

The fact that only 7.5 % of rural youth working in agriculture are self-employed (FAO Guatemala, 2017b) illustrates the need for enhanced support to agricultural entrepreneurship. This especially as rural youth in Guatemala tend to hold positive attitudes towards rural employment and are eager to contribute to the development of their communities by becoming entrepreneurs in agribusiness (Pafumi, 2017).

2.4.3 The digital platform ChispaRural

As noted by Pafumi (2017), job orientation services are still in an early stage in Guatemala and young people struggle to access agricultural extension and advisory services, while they are generally perfectly familiar with ICTs and rely on smartphones and social networks for much of their information and communication needs. These findings spurred the development of the digital platform ChispaRural.gt, supported by the FAO ComDev team through a comprehensive participatory process. Developed in collaboration with the Ministries of Agriculture, Economy and Labour of Guatemala as well as with international cooperation and civil society actors, the platform is an integral part of the National Strategy for Rural Youth of the Ministry of Agriculture of Guatemala (Pafumi, 2017).

ChispaRural.gt addresses several of the measures identified as necessary to make agriculture more attractive and viable for young people (see Leavy & Hossein 2014; Melchers & Büchler, 2017). In particular, it promotes viability through access to information on job opportunities, training materials and best practices, and attractiveness by showing examples of positive role models in the shape of young and successful ‘agripreneurs’. In addition, it offers a space for young people from different communities to connect, learn from and inspire each other (FAO, 2017).

2.4.4 Climate and disaster vulnerability

Guatemala is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and extreme weather events due to its geographical position in a drought prone earthquake and hurricane zone (Lawrence, 2011). A recent study shows that prolonged droughts in the Corredor Seco, the ‘Dry Corridor’ stretching through Guatemala and neighboring countries are a significant driver of migration (UN, 2017). According to FAO (2017), Guatemala is in fact considered the fourth country most vulnerable to natural disasters in the world, not only because of its geographical characteristics but also due to the high levels of social inequality.

2.4.5 Politics and media

The transition towards democracy in Guatemala has been rocky since independence from Spain was declared in 1821. After a century of dictatorships, a decade of democracy and social development ended abruptly by a coup backed by the USA in 1954 (BBC, 2018), depicted as a legitimate uprising against a government with threatening communist tendencies. Yet the underlying reason lay closer to the challenges voiced by the key-informant from Socialab in the opening quote of this paper: territory, land rights and food production. At the time, the Guatemalan president had launched a land reform to reclaim and redistribute unused land owned by the US’ United Fruit Company (Malkin, 2011).

Years of unrest marked by guerilla conflict followed and full civil war broke out in 1960, resulting in 36 years of military rule and atrocities by the far right including assassinations, massacres and disappearances, mainly directed at indigenous populations. It is estimated that 200,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed or disappeared. A peace accord was signed in 1996 between the government and guerrilla groups, recognizing indigenous Guatemalans as full citizens and strengthening civilian power (BBC, 2018). Yet, as becomes clear also through the empirical data collected in this study, the signs of the past still mark the present and are reinforced by persistent inequalities.

During spring 2018 a deterioration of the situation for human rights, freedom of expression and international cooperation was noted within the country. Little official information is available, but following three killings in 10 days of human rights advocates engaged in indigenous and rural community associations, a press release issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in May 2018 expressed concern over observed campaigns also against journalists and independent media outlets, officials of the juridical system, representatives of the civil society and other actors involved in the fight against past and present

corruption and impunity. The release calls on the government to urgently address the reported concerns, as part of its broader efforts to strengthen the rule of law, freedom of expression and juridical independence and fight corruption and impunity (Pocón, 2018). Such efforts are supported by the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), an independent body established through an agreement between the government and the UN in 2007, with a unique and deep-going mandate (CICIG, 2018).

According to Reporters Without Borders (2018) Guatemala is still among the Western Hemisphere’s most dangerous countries for the media, with journalists remaining frequent targets of murder. In a culture of widespread violence and impunity, exposing corruption can lead to threats and physical violence. Guatemala ranks 116 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Approach

As noted, the methodological approach in this study is inductive and exploratory rather than aimed at testing theories or assumptions. The starting point is the identification of a problem area: the difficulties of young small-holder farmers in Guatemala to access markets and other resources and thereby to engage in agricultural practices more in line with their needs and aspirations, and an objective: to promote such access by exploring an area which has not yet been subject to much attention, i.e. the linkages between rural and urban youth and their perceptions of agriculture and local food production.

By being problem rather than methods-driven, this methodology adheres to what Layder (2014: 70) refers to as the adaptive approach in social research, which aims to collect “empirical data which will cast light on the nature of the principal social domains and the key analytic or problem-questions with which they are linked”. The analytical framework presented above, with its four core areas of inquiry and sub-questions for each, is inspired by this approach.

While the adaptive approach per definition does not exclude any research methods, this study applies only qualitative tools. The option of issuing an online survey was considered initially, both to help define the guiding questions and to assess the generalizability of the findings. However, considering the complex and multilayered nature of the topics treated as well as the low probability of reaching a big enough number of respondents to ensure generalizability with the time and resources at hand, this option was excluded in favor of more comprehensive interview research.

3.2 Interview research

Qualitative interview research has become one of the most popular practices for producing knowledge within the social sciences according to Brinkmann (2008), who encourages researchers to first reflect on whether interviewing is really the most effective way to reach their aims. In the case of this study, where the goal is to produce context-specific knowledge on a fairly unexplored topic in order to inform an existing development programme, the choice to produce such knowledge through interaction with those involved seems well grounded.

The empirical research was carried out during a two weeks’ fieldtrip to Guatemala, between March 26 and April 10, 2018. It took place in five different locations and consisted of four focus groups, five key-informant interviews and 10 intercept interviews, engaging a total of 43 interviewees and resulting in over 10 hours of audio recordings. The relevance of each interview type for the research aims of this study is discussed below.

In addition, several informal conversations with FAO colleagues and partners as well as more random travel companions and acquaintances inspired the research. Although the outcomes of these conversations are not included in the analysis section below, they have become an integral part of my research experience and color the lenses through which I reflect on the findings.

3.2.1 Focus groups

In focus group interviews data is generated through group discussions lead by the researcher. The technique appeared suitable for this study as it is often used to explore previously unexamined topics, based on the assumption that discussion among those concerned can bring about more constructive exchange than a one-to-one conversation between researcher and respondent. While group interviews share many of the challenges of individual interviews, they also have characteristics of their own (Morgan, 2012). The main challenges encountered during the research are introduced here and relate to group composition, selection of questions and moderating style. According to Morgan (2012), it is common to convene groups of people that share a similar background in order to facilitate meaningful conversations. This study included two groups with participants mainly from rural areas – in the departments of Quetzaltenango and San Marcos – and two mainly from urban settings – the capital Guatemala City and the second biggest town Quetzaltenango, commonly referred to as Xela. Yet as explained below for the scope of this study the question of urban vs. rural identity is left for the interviewees to determine. In some cases identification was dual – one interviewee in the capital (group 4), for example, grew up outside the city and is now aiming to move out again. Two young students in the rural town of Tejutla, San Marcos (group 3) feel more connected to the urban setting of the town than to the surrounding countryside. Although this implied that the groups were not fully homogenous, in general the level of recognition and consensus seemed high. It should be noted, however, that reaching agreement is by no means the goal of focus group research (Morgan, 2012). On the contrary, divergent positions often drive the conversation forward generating much knowledge on the way.

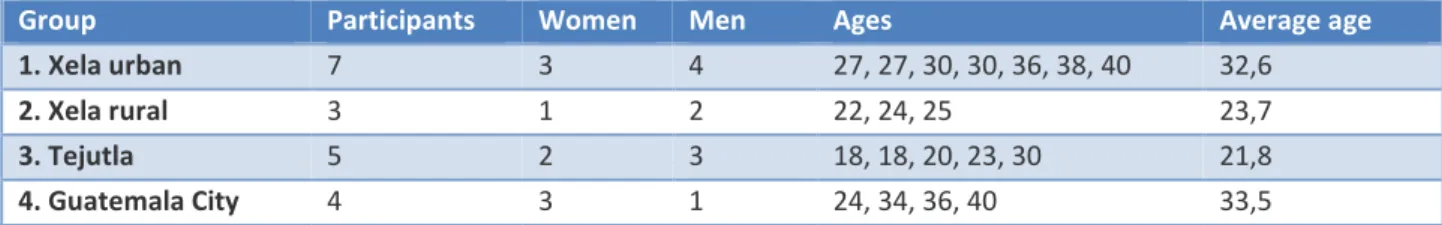

FAO colleagues and partners provided great support in organizing the research schedule, including in convening the focus groups. This was often challenging, as the fieldwork was limited to a relatively short period of time and coincided with Easter holidays. The final group composition was therefore not only a result of strategic selection, but also of participant availability. For this reason also the definition of ‘youth’ had to become somewhat flexible, with participant ages ranging from 18 to 40 and an average age of 28 (See table 1 below and appendix III for more detail). Despite these challenges, the final outcome still seems to adhere to the balance suggested by Morgan (2012) between the researcher’s requirement for relevant data and the participants’ need for a comfortable discussion setting.

Table 1: Focus group participants

Group Participants Women Men Ages Average age

1. Xela urban 7 3 4 27, 27, 30, 30, 36, 38, 40 32,6

2. Xela rural 3 1 2 22, 24, 25 23,7

3. Tejutla 5 2 3 18, 18, 20, 23, 30 21,8

4. Guatemala City 4 3 1 24, 34, 36, 40 33,5

The guiding questions can be found in appendices I and II. The areas of inquiry and the initial lead questions where formulated ahead of the fieldtrip, but the focus and phrasing was adapted on the spot to the participants’ interests and experience. Indeed, the principle of dual consideration for the needs of both researcher and respondents should apply also to the selection of questions (Morgan, 2012). This process of understanding how to read the interviewees’ reactions to a certain topic or wording, and adapting the moderating style whilst not loosing sight of the research objectives, was one of the main sources of learning for me as an inexpert researcher.

Striking the balance between flexibility and structure is probably an inherent challenge of the semi-structured interview style used in this study, applying to both focus groups and individual interviews. Morgan (2012) asserts that more structure fits well with a tightly defined research agenda while an exploratory aim requires more flexibility. In this case, where the aim is indeed exploratory but within certain rather well defined areas of inquiry, balancing between openness to the many interesting and related topics introduced by interviewees and keeping to the core areas was a constant and enriching challenge.

Another challenge that is unique to group interviews and relates to all parameters of group composition, selection of questions and moderating style is that of encouraging all participants to take part, while not forcing anyone to speak. The same applies to facilitating an authentic conversation that allows conclusions to evolve, rather than a sequence of individual statements. 3.2.2 Key-informant interviews

Details on the key-informant interviews are provided in appendix III. Interviewees were identified based on suggestions from FAO-colleagues and partners and are all engaged in activities related to local food production and/or linkages among rural and urban youth.

According to Morgan (2012), the choice between focus groups and individual interviews is mainly one between depth and breadth. In this case, a one-to-one setting was deemed more enriching with the key-informants as it allowed for in-depth discussions on their experiences and engagements, which are all of great relevance here. Striking the balance between flexibility and guidance in the interview technique remained the main challenge.

A combination of individual and group interviews is common, especially with one method preceding and inspiring, or being tested by, the other (Morgan, 2012). Here, the focus groups preceded the key-informant interviews and provided important input for nuancing the individual questions, while the one-to-one discussions raised several points of reflection related to the outcomes of the focus groups.

3.2.3 Intercept interviews

As a way of confronting the findings of the focus groups and key-informant interviews, a number of so-called intercept interviews were carried out during the last two days of the fieldwork. These implied approaching young people asking if they would be available to respond to a number of direct questions for about 5-10 minutes. A total of 19 people participated in 10 interviews, as interviewees seemed more confortable conversing in pairs than individually. Further details, including the questions asked as well as sex, age and perceived rural or urban identity of the interviewees, are provided in appendix III.

3.2.4 Ethics

To address key ethical concerns of confidentiality, informed consent and consideration of potential consequences of participating (see Brinkmann, 2008), all interviewees were informed at the outset of the context and objectives of the research, as well as of their anonymity. Although most of the conversations included personal reflections, in general the questions asked cannot be considered of a private or particularly sensitive nature.

3.3 Analysis

As noted, the analytical framework used to assess the empirical data is based on the four main areas of inquiry. Although discussions often flowed more freely across the fictitious borders set up between these areas, in the analysis I attempt to connect the findings to the area where they seem most pertinent and produce most knowledge in relation to the research aim. The findings from all interview types as well as for both rural and urban interviewees are analyzed together, precisely to show on the linkages between them.

Clearly, this approach provides for a considerable amount of researcher’s bias, as the selection is based entirely on my interpretation1 of the interview content. There is no way of accounting for all

1For an account of how meaning is created through interpretation, see e.g. Hall, Stuart; Evans, Jessica & Nixon, Sean (ed.). (2013). Representation. Second Edition. London: Sage

interviews fully, and the selection of excerpts is done without any objective criteria (such as coding of certain key-words). Yet in an exploratory study where no hypothesis is being tested, this approach appears somewhat less problematic. Brinkmann’s (2008) position that there is no preferred analytic method in interview research, but that it must respond primarily to the purpose of the study, is uncontroversial and aligns with the concept of scientific validity, i.e. whether the research actually investigates what it was intended to (Golafshani, 2003: 599).

In line with the criteria for this thesis, no full transcripts have been made from the interviews. Instead, the numerous quotations in the analysis are intended to enhance the accuracy of accounts. Recordings and notes from all interviews are kept in order to allow for potential review in support of scientific reliability, i.e. the extent to which results would be reproduced by another researcher applying a similar methodology (Golafshani, 2003: 598).

3.4 Limitations

The limitations of this study are multiple. The most obvious is probably the limited scope of

generalizability: the sample used is simply too small to claim any broader applicability. The intercept

interviews were carried out to (con)test the findings of the other interviews and did provide some valuable input in this regard, yet clearly not enough to prove them right or wrong. However, considering the aim and approach of this study – its exploratory nature and the goal of contributing to the knowledge-base and messaging linked to a specific project – such lack of generalizability cannot reasonably be considered a fundamental weakness, nor compromising the validity of the research. Indeed, the relevance of generalizability in qualitative research is contested, as are the concepts of validity and reliability as such (Golafshani, 2003).

Some more specific caveats should be made in relation to key concepts. As noted, the term ‘youth’ is applied with flexibility in a somewhat supply-driven manner. Moreover, the distinction between rural and urban is based on the subjective identity perceptions of the interviewees rather than on geographical and demographic characteristics, although in general the distinction was pre-defined to a certain extent through the support provided by FAO colleagues and partners in the selection of participants already considered part of one or the other group.

At least three relevant themes that were left out of the scope of this study should also be mentioned here. First, in relation to identity and belonging, issues of ethnicity are not dealt with in any depth. Although a few cases of discrimination specifically directed towards indigenous individuals and groups were mentioned during the interviews, in general discussions focused on differences and similarities among rural and urban groups, independent of ethnic belonging. This is of course not to say that ethnicity is irrelevant for this study. When references to the civil war and remaining mistrust are made, one can assume that it is still a highly significant factor. Yet for the goals of this study it does not appear as decisive, especially considering that both urban and rural populations are composed of different ethnicities (see e.g. Pafumi, 2017).

Secondly, although some interviewees referred to significant gender inequalities particularly when discussing differences and similarities between rural and urban youth, no further distinctions in relation to gender are made here, apart from the inclusion of numbers of female and male interviewees in focus groups and intercept interviews. Thirdly, while providing much space to the value of local food production for development, this paper does not discuss the impacts of international food trade, neither positive nor negative, at any length. Interested readers will hopefully find much valuable information on these topics in other studies.

It is also important to note that the empirical research was conducted in Spanish and that all translations are the work of the author. Although I consider my familiarity with both languages sufficient to manage this task, it does add to the layers of interpretation.

Finally, a note of clarification regarding my relation to the FAO. At the time of conducting this study, I work at the Permanent Representation of Sweden to the UN-agencies based in Rome, including the FAO. Before this I served as consultant at the FAO for two years. These connections have proved helpful for the scope of the research, facilitating contacts as well as my understanding of the work of the organization. In addition, it should be noted that the ICA programme referred to above is funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida (FAO ICA, 2018). However, as this study does not imply any formal assessment of the work of the FAO nor Sida and does not have any financial implication for either (all costs are covered by the author) these circumstances are considered not to bring about any conflicts of interest or other compromising implications for the research. Indeed, the conclusions are all my own and the thesis does not express any official views of the FAO. In essence, the study was carried out independently from, yet informed and inspired by, my professional role and experience.

4 ANALYSIS

This chapter covers the main areas of inquiry in four sections, each divided into sub-sections corresponding to the main topics of discussion.

4.1 Rural versus urban life and work and related challenges

The focus here is on perceptions of urban versus rural life and work, a well as on the value of agriculture and food production for development.

4.1.1 Agriculture and development

There is overwhelming consensus among interviewees, in focus groups, key-informant and intercept interviews alike and across rural and urban identities, that agriculture is important for development. Interestingly, the idea also prevails that such a perception is not that common.

In the focus group held in the rural town of Tejutla, San Marcos (3), participants agree that agriculture is important not only because it provides the food we all need to survive, but also as a source of employment. They exemplify this with an initiative for school feeding in which one of the participants takes part, resulting from a new law indicating that all food provided in schools should be locally produced. The focus group held in Xela with participants in the Factoria for rural entrepreneurs (2), agrees agriculture is vital for all parts of society. While some believe urban people do not care much about rural work, according to another the picture is more nuanced:

“Not all are like that. There are also very interested people who want to change the systems of the cities. It is like in the rural areas, they are like us, we want to change these systems; migration, poverty and all that. We are a little white spot in all the black, and I think it’s the same there. We try to change things but our own culture and society limits us (…).”

In fact, all urban interviewees confirm the importance of agriculture. In the focus group at the digital marketing agency in the capital (4) participants asserts that they all depend on it, as urban food markets do. At the same time, the focus group held at the business incubator in Xela (1) considers that due to the low levels of income, in both urban and rural settings many find it “complex to believe that agriculture will be the key to development of rural areas”. Still there is growing “recognition that this will have to change”. The key-informant from El Mercadito de Lola (from here El Mercadito) (3) agrees on the need to raise awareness that agriculture can be a strong driver of development, “not only in big scale but also in small”.

A big majority of the intercept interviewees confirms the value of agriculture, and no one questions it. The arguments expressed include that it feeds all, supports the livelihoods of a big part of the population, contributes to the national economy and development, and develops and conserves vital knowledge. Also during these interviews, which partially served to test the findings of the others, several state that not everyone would share this view.

4.1.2 Rural challenges

The main challenge noted by a great majority of interviewees is the difficult to access to resources and opportunities in rural areas. This is expressed clearly in the introductory quote by the representative from Socialab, and echoed in the in the section on differences among rural and urban youth below. Among the resources that stand out as scarce in rural areas, next to infrastructure and capital, is education.

Several interviewees claim that the high levels of chronic malnutrition in many rural areas are at least partially a result of poor nutrition education. According the focus group in Tejutla (3) “We often go to the pharmacy to try to cure malnutrition. But what we need is knowledge about what is healthy and nutritious.” A company that serves local healthy food to the workers is mentioned as an example of how to counteract the tendency. The focus group at the Factoria (2) agrees that “Then pharmacies could close and people would value their food more”.

Several also note a misalignment of available education with actual needs. The group in Tejutla (3) asserts that “education here is shaped for service, not entrepreneurships, and there are not enough jobs to absorb all that graduate from these careers”. The view is confirmed by the business incubator group (1), while the key-informant from El Mercadito (3) points at the potential of education to “encourage young producers not only to farm but to diversify production and produce in ways that are more sustainable and resilient.”

Scarce resources and opportunities are considered the main drivers of a challenge that emerge in almost all conversations: migration. When asked whether they know anyone who migrated, the participants at the Factoria (group 2) smile politely and explain that all of them have family members and friends in the USA. They add that one migrates to work, not to study, to send money back so that those at home can have better opportunities. And that its not easy for migrants who decide to come back, as they will generally have lower levels of education than those who stayed. There are also instances of relatives going to Guatemala City to work, usually as housemaids: “all my aunts moved to the capital as my grandfather did not have enough to offer them to eat, not to mention any opportunities” says one participant.

In the Tejutla group (3), a participant tells that “before I started to work here I had the ticket paid for the US, but I am happy here, and now since we’re organized and have support its more motivating”, adding that the salaries in the US might not pay off: “I can work just as much here and earn more, because I don’t have to pay for service etc. far from home. (…) We just need to know how to manage the money”. Another participant shares an example of a man who migrated and sent money back for his family to start a business in agritourism, where they serve local food, attracting both Guatemalan and foreign tourists.

In fact, several of the rural interviewees also point to the potential of rural areas: “There are quite a lot of opportunities in agriculture, but the problem is the earnings – no one will come to a rural area because the salary is so low”, but still “We want to show other young people that opportunities are not limited to cities. Here too we can create great companies” (group 2). In Tejutla (group 3) participants agree that there might be more opportunities in cities, but “there are opportunities also in rural areas, you just have to look for them.” They add that people are not very patient, which also drives migration: “Its difficult to believe; you need to have entrepreneur spirit and patience to wait for the results.”.

The findings in current research that regardless of the challenges there is still interest among young people to live and work in rural areas, is also confirmed by several of the rural interviewees. “I prefer rural life. It means more contact with nature, less stress. There is more freedom of work; we might have to struggle, but its satisfying not to have a boss, to be free.”, says one (group 3).

Six out of the 19 intercept interviewees say they would like to try life in a rural area, mainly out of curiosity but also to lead a calmer life more in contact with nature. Only one expresses a clear unwillingness to do so, because of a perceived lack of interaction and dynamism on the countryside.

The Tejutla group (3) adds to the picture: “There are urban people who would like to live in rural areas, but because of land difficulties its not that easy to achieve.”

4.1.3 Urban challenges

Several of the rural interviewees hold nuanced views also of life in the cities. Traffic and criminality are among the main challenges mentioned:

“I have cousins and aunts in the capital (…) they have safe jobs, work for companies and institutions, but they can’t stand the traffic. In the rural areas we wake up and go to work and don’t have to worry about traffic or crime. Our communities are very calm and organized with their rules and we don’t have criminality as in the city. You can’t walk there, its very dangerous.” (focus group 2).

Poverty and lack of opportunities are recognized as problems pertaining also to urban areas: “It is not always easy to find a job in the cities. (…) Not all people in the cities eat well and not all rural people eat poorly. It depends on the job and income one has.” (group 2). The key-informant at El Mercadito (3) supports this view: “I couldn’t believe there was so much need inside the city; there are slums and poverty. People might have jobs and often smartphones, but not enough resources and knowledge to eat well.” The Factoria group (2) connects the urban challenges to population growth: “We’re more by the day. There are a lot of graduates that can’t find a job.”

4.1.4 Linking the two

Several express that at least part of the solution to rural and urban challenges alike lie in the linkages between them. According to the Tejutla group (3) “If it wasn’t for the cities we wouldn’t have income, and if it wasn’t for us they wouldn’t have food. So it’s a kind of symbiosis, one needs the other to survive.”. Yet regardless of the broad consensus on this interdependence, some interviewees subtly refer to historical reasons that might hamper rural-urban relations built on trust and mutual consideration. When touching on the civil war during the conversation at the marketing agency (group 4), one refers to “how much they killed for land” and states that many, particularly in rural areas, are not ready to talk about the atrocities – especially not with people from the capital. The key-informant from Coffee Kids (4) also mentions the ongoing investigations of killings and adds “but in the meantime we all have to go on and evolve, we can’t wait for them to solve their issues”. Meanwhile, some interviewees point to the need to think beyond the classic division of cities as markets populated by consumers, and the countryside made up of solely producers. As the key-informant from el Mercadito (3) puts it:

“So people in the city, as there is so much offer of workforce and not that much demand, the first thing they do is to start selling something (…) while it would be better to start enterprises locally, like in agritourism, to decentralize consumption, to create employment opportunities and have the income circulate locally, creating local micro-economies.”

Although many indicate important challenges for realizing this kind of territorial development, including infrastructure and marketing in order to direct tourists off the beaten tracks, the ideas

reappear in various conversations. Participants in both rural focus groups (2 & 3) illustrate how their work supports local communities and assure that there is potential to do much more. The key-informant from Socialab (5) explains how several of their initiatives aimed at developing territories helped to realize that the line between cities and countryside is not as sharp as it might appear; there are many semi-urban and semi-rural areas with their own challenges and potential.

4.2 Rural versus urban youth

This section looks at the ideas urban and rural youth have of themselves and each other, their differences and similarities, the reasons behind these as well as their implications.

4.2.1 Differences depend on context

The most pervading finding for this area of inquiry is that differences between rural and urban youth are mainly perceived as depending on context rather than character, i.e. on differences in access to resources and opportunities, as introduced in the preceding section. This is particularly salient for urban interviewees, among which almost all refer to significant differences particularly regarding education, but also in health services, access to information, technologies and entrepreneurial support (focus groups 1 & 4, key-informant interviews 3-5, intercept interviews). One intercept interviewee actually refers to rural youth as less intelligent, resulting in embarrassed expressions amongst surrounding friends, just to come to the conclusion that this too would depend on the quality of education.

Several of the rural participants consider rural youth more hard-working, precisely because of differences in service and support. While some indicate the will to finish school as a similarity between the groups, a participant at the Factoria (group 2) nuances the picture:

“I think there is even more interest to finish school in rural areas, but a lot of people don’t have time; they work and might have two jobs while they study, and sometimes need to take care of a sick relative. Maybe in cities this is not the case as they have more commodities; they just wish to graduate and start working. In rural areas we might want to supersede ourselves to have something more, because of the poor resources and limitations. It is very hard to build a home here, sometimes people need to migrate – in the cities this doesn’t happen. The parents have good jobs, enterprises. In rural areas we don’t get tired – we work and work and work.”

The Tejutla group (3) concurs: In the cities, “they are more into social media, each in their own wave, here we live more in contact with nature and with each other. They’re less connected to reality, want everything without effort, (…) but then when life shows it’s not that easy, they can end up in crime, while here we learn to work.”. Yet as we have seen, there is also recognition of the risk of generalizing: “also in the city some young people want to change the way things work, and work to do so” (group 2).

In fact, at the marketing agency (group 4) participants include a hard-working spirit among the similarities between rural and urban youth. Interestingly, they also add migration to this list, and the emotions linked to having family abroad. Other similarities mentioned are creativity, traditions and culture, including gastronomy. All of these characteristics are wrapped up by the words “tenemos corazón chapín2” – ‘we have a Guatemalan heart’.

4.2.2 Mindsets diverge, and meet

Both rural and urban interviewees refer to differences in ways of thinking. The rural group at the Factoria (2) notes that although there are many exceptions, most people in rural areas “are quite closed and resistant to change”. At the business incubator (group 1) the view is echoed that urban ideas tend to be more open, liberal and capitalist, while rural views and priorities are more conservative, especially regarding entrepreneurship. While recognizing the risk of generalizing, “rural youth tend to work for themselves and their families”, hold “ideas closer to traditionalism” consider “entrepreneurship limited to opening a store and earn money straight away” while “it can mean not earning anything for six months” and “some are open to this to risk, but most are not willing to, its considered a waste of time.” .

Again, it comes down to resources: “Entrepreneurship is the same in rural and urban areas, with the only difference that if you want to develop an enterprise only in a rural area it will be more difficult (…) the ideas are the same, the objectives are the same but access to resources (…) is a very limiting factor.” (focus group 1). The quality of education stands out, as noted by the key-informant from Coffee Kids (4): “there might be education in rural areas but generally no capacitation, nothing that encourages curiosity and creativity.”

The key-informant from Socialab also points at demographic and cultural reasons and a “social aging of rural youth” who tend to have a family at ages where urban youth might still be living at home studying. Several participants in the focus groups (1 & 4) and intercept interviews concur that rural youth tend to hold more conservative views and value customs and tradition higher.

4.2.3 Persisting prejudice

Meanwhile, there is recognition of discriminatory views and prejudice on both sides: “When we come to the city to study, one realizes that they are quite arrogant. Sometimes those from the city think about people from rural areas as illiterate, but actually (…) they might be rather humble and sincere, compared to those from the cities.” the Factoria group (2) notes. The group in Tejutla (3) adds “Although it might be the contrary, we might have a better life in the rural areas, but just for the fact that we live here they put a poverty label on us. (…) Many ideas are wrong, outdated.” A couple of urban intercept interviewees agree that although values of urban and rural youth are similar, the rural can be even more “noble”.

2Originally the name of a particular Spanish shoe, the word Chapín has over time been adopted by many Guatemalans as a nick-name for their own national identity.

According to the key-informant from Socialab (5), “there are also prejudices in rural areas that all capital people have racist and classist ideas, the reasons for these impressions are justified, but still, these tensions limit us in our encounters”. The key-informant from El Mercadito (3) adds: “we need to break these beliefs, not with pity or as victims, but understanding that we are equal, so apart from #heforshe here we need a #youforme or #usforus.”

4.2.4 The capital and the rest

The sharp divide between the capital city and the rest of the country introduced at the beginning of this paper is confirmed by a majority of the interviewees. In the business incubator focus group (1), where many participants come from Xela or other smaller towns, views are clear that “the main difference is between the capital and the rest” while “there are more connections between cities in the department and their rural surroundings”, in fact “there is the capital, everything else is considered exteriors” and “people from the capital don’t like the word ‘rural’; they connect it to a lower level”.

Key-informants in Guatemala City confirm that “everything is concentrated in the capital” (4), “some young people here have never been to the country-side” (5), and “the city is a bubble where no one knows what happens outside” and where there is not much interest among young people to visit and learn more about rural communities (3). Yet as discussed below, this idea is challenged by the findings of the intercept interviews.

4.2.5 Youth as the solution

Clearly, differences exist not only between but also within the urban and rural groups. As pointed out by the key-informant from Socialab (5): “there are many kinds of youth”. Still there is broad agreement that young people have at least one thing in common – a great potential to drive development, largely due to their flexibility of mind:

“Youth have the advantage of being more versatile. I think it’s a stage where you still haven’t fixed your beliefs and auto-explained how the world works, so there is more openness. I know many cases and spaces, initiatives of urban and rural youth that have joined forces to do interesting things.” (Key-informant 5).

The Factoria group (2) concurs, noting that “People tend not to have the patience to create change (…) but it’s easier among young people, while the older focus on how to earn enough for the day and stop there”. The key-informant from Coffee Kids (4) confirm that coffee vendors tend to prefer working with young producers, as they are often more willing to innovate and try new methods, including ones that are more resilient and climate smart.

As further presented in appendix III, many of the key-informants and focus group participants are involved in initiatives that support linkages among rural and urban youth. Two examples are provided here.

Table 2: Examples of rural-urban linkages – Coffee Camp

Coffee Camp

What: A three day Coffee Camp – nueva generación cafetalera (‘new coffee generation’), a joint FAO-private sector initiative coordinated by the key-informant from Coffee Kids, aimed at linking young coffee producers more closely to roasters, vendors and baristas and create opportunities for synergies and collaboration.

When: April 25-27 2018, just a few weeks after the fieldwork for this study.

Where: At a coffee farm not far from the old capital Antigua Guatemala.

How: More than a hundred young coffee producers participated in visits to coffee shops in Antigua, lectures on various steps of production and the full value chain, as well as business meetings with coffee shops and exporters. Slogans for the event include “Linking Urban and Rural Youth”, and “Ya todos somo una Comunidad” (‘now we’re all a community’).

Next steps: The exchange continues on the platform Chisparural.gt. The key-informant from Coffee Kids (4) is positive that similar initiatives can emerge for other sectors and crops: “Yes you can replicate! It might not be as romantic to sell a carrot as selling a cup of coffee, but everything is marketing. We’re selling experiences. (…) All food is at our basis. How many chefs aren’t working with organic, how many aren’t vegans in the city now?”

More info: http://www.fao.org/guatemala/noticias/detail-events/es/c/1127151/;

https://www.facebook.com/coffeecampgt/;

https://chisparural.gt/blog/2018/04/25/coffeecampgt-una-experiencia-para-vivir-y-crecer/

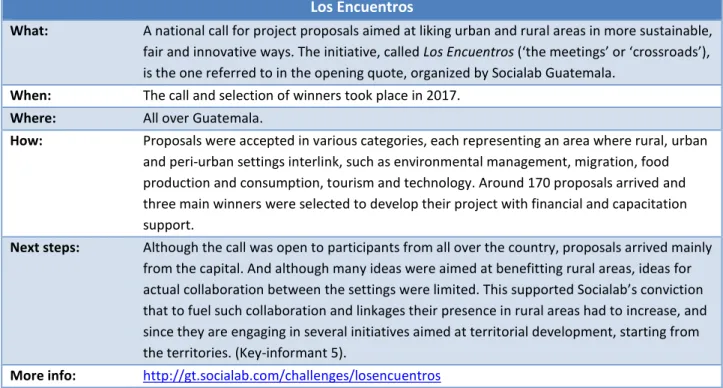

Table 3: Examples of rural-urban linkages – Los Encuentros Los Encuentros

What: A national call for project proposals aimed at liking urban and rural areas in more sustainable, fair and innovative ways. The initiative, called Los Encuentros (‘the meetings’ or ‘crossroads’), is the one referred to in the opening quote, organized by Socialab Guatemala.

When: The call and selection of winners took place in 2017.

Where: All over Guatemala.

How: Proposals were accepted in various categories, each representing an area where rural, urban and peri-urban settings interlink, such as environmental management, migration, food production and consumption, tourism and technology. Around 170 proposals arrived and three main winners were selected to develop their project with financial and capacitation support.

Next steps: Although the call was open to participants from all over the country, proposals arrived mainly from the capital. And although many ideas were aimed at benefitting rural areas, ideas for actual collaboration between the settings were limited. This supported Socialab’s conviction that to fuel such collaboration and linkages their presence in rural areas had to increase, and since they are engaging in several initiatives aimed at territorial development, starting from the territories. (Key-informant 5).

More info: http://gt.socialab.com/challenges/losencuentros

4.3 Motivations and habits of food consumption and perceptions of local produce

Rural interviewees (focus groups 2 & 3) are interested in knowing more about consumer preferences in urban settings. This area of inquiry focuses on food preferences and drivers of