Does Length Matter?

An exploratory study on the current state of producers in

Short Food Supply Chains

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHORS: Daniel Petri Cortés, Victor Magnusson & Simon Wernerhag JÖNKÖPING 05/2020

1

Acknowledgments

“Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated”

–

Confucius

The authors would like to first and foremost express our sincere gratitude towards the participants, the food producers, who voluntarily contributed with valuable knowledge and enthusiasm which allowed us to create a well-founded analysis of the topic.

We would like to thank our thesis tutor and licentiate in Economics and Business Administration, Johan Larsson, for supporting our idea and providing valuable guidance and inputs during the entire course of this research.

Last but not least, we appreciate the support from Miquel Correa, a JIBS Doctoral Candidate in Economics, for sharing his thoughts and supporting the purpose of this study.

____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Daniel Petri Cortés Simon Wernerhag Victor Magnusson

2

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Does Length Matter? - An exploratory study on the current state of producers in Short Food Supply Chains

Authors: Daniel Petri Cortés, Victor Magnusson & Simon Wernerhag Tutor: Johan Larsson

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Short Food Supply Chains, Food Supply Chains, Sustainable Development,

Alternative Food Systems, Socio-environmental Responsibility.

Abstract

Background: The relevance of the food system for economic, environmental and social well-being is vital to consider. However, there is a lack of research covering issues and performance assessments of the supply chains in the food industry. Due to pressures on the natural environment and unsustainable production and distribution, Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC’s) have arisen as an alternative model to conventional supply chains. However, there is a need for more research in the field as its showing to be a growing trend in the food industry.

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to study the topic of SFSC, where the focus in this paper is to explore what advantages and barriers food producers experience when operating within a SFSC.

Method: This study is exploratory and follows an inductive and qualitative approach, where 6 semi-structured interviews with local food producers were used to collect data. The data was analysed and connected to previous literature using a thematic analysis.

Conclusion: The findings in this research illuminates that the advantages and barriers from selling through SFSC´s depends on the circumstances of the channel and the characteristics of the producers. They experienced advantages in their organization such as a high professional satisfaction, fair compensation and autonomy. The social proximity between the actors also facilitated the management of information and allowed for supply chain flexibility. However, producers also faced barriers such as the lack of proper governance in the SFSC channels, and logistical challenges such as the uncertainty of production and the difficulty of ensuring the efficiency of transportations. The analysis of SFSC’s is still in its early stages and the necessary innovations to attain the full positive effects have yet to be implemented.

3

Table

of

Contents

1. Introduction... 5 1.1. Background ... 5 1.2. Problem Discussion ... 6 1.3. Purpose ... 7 2. Frame of Reference ... 82.1. Method for constructing the frame of reference ... 8

2.2. Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC) ... 9

2.2.1. Why Are SFSC´s Relevant Today? ...12

2.2.2. SFSC´s as a Driver for Sustainable Development ...14

2.2.3. Barriers to the Implementation of SFSC´s ...17

2.3. Supply Chain Management (SCM), Circular Economy (CE) & Lean Management ... 18

2.3.1 CE & Food Supply Chain Management ...18

2.3.2. Opportunities for a More Circular Economy in the Food Industry...19

2.3.3. Lean Management & Flexibility in Supply Chains ...20

3. Methodology ... 21 3.1. Research Philosophy ... 21 3.2. Research Approach ... 22 3.3. Data Collection ... 23 3.3.1. Interviews ...23 3.4. Data Analysis ... 24 3.5. Trustworthiness ... 26 4. Empirical Findings ... 28 4.1. Advantages ... 28 4.1.1. Logistical Advantages ...28 4.1.2. Higher Margins ...29 4.1.3 Customer Demand...30 4.1.4. Information Flow ...31 4.1.5. Professional Satisfaction ...32 4.2. Barriers ... 33 4.2.1. Barriers to Entry ...33 4.2.2. Logistical Barriers ...34 4.2.3. Governance ...35 5. Analysis ... 36 5.1. Emergent Themes ... 36

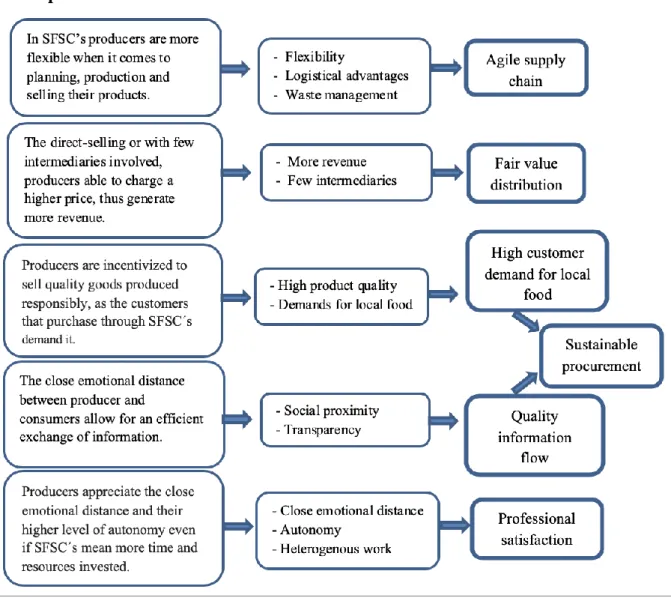

5.2. Agile Supply Chain ... 37

5.3. Fair Value Distribution ... 40

5.4. High Customer Demand for Local Food ... 41

4

5.6. Quality Information Flow ... 42

5.7. Professional Satisfaction & Social Responsibility ... 44

5.8. Barriers to Entry ... 45

5.8.1. Learning Curve ...45

5.8.2. Financial Barriers ...45

5.9. Logistical Barriers ... 46

5.10. Lack of Governance Structure ... 48

6. Conclusions ... 50

7. Discussion ... 51

7.1. Limitations ... 53

7.2. Suggestions for Future Research ... 53

8. References ... 55

9. Appendices... 60

Appendix A: Interview Guide ... 60

Appendix B: Generating initial codes ... 63

Tables ... 68

5

1. Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________ The introductory chapter introduces a background and presentation of the subject that will be dealt with in this thesis. It follows with a problem discussion and the purpose of the study. ___________________________________________________________________________

1.1. Background

The food industry is one of the most important sectors in the global economy, not only for economic development, but for social wellbeing and environmental quality. However, there is a lack of research covering issues and performance assessments of its Supply Chain (SC) (Turi, Goncalves & Mocan 2014). Around the 1970s, attention started to be paid to the consequences of agricultural practices on the food system (Bauerkämper, 2004) and since then, modern agriculture is approaching an ecological collapse which is likely to push it into a state of persistent crisis (Buttel, 2006). In addition to that, as human population increases, further pressure is put on this sector (Norin & Unevik, 2015). The conventional food supply chains (CFSC´s) in developed countries like Sweden is equally subjected to these issues and lacks performance assessments to evaluate their impacts. According to the latest report on the Swedish National Food Strategy (2017), having a viable domestic food production is also a strength in terms of crisis preparedness. The current “Covid-19” emergency state has led to interruptions in production and disruptions in the functioning of global SC´s (McKibbin & Fernando 2020) but luckily, it is not provoking major disturbances in the Swedish food system. The most important industries and food companies in the country met in late March 2020 and stated that there is no lack of food security yet. Exploring how SC´s are integrated and ways to decrease the exposure to risk in the future has made the authors take interest in how the structures of production and its SC are managed in Sweden. These signals have been pushing new models of Supply chain management (SCM) to arise and renew the way we manage the food industry. Among them are cases of organizations and individual producers that are realizing these issues and are reacting by selling their products using Short Food Supply Chain (SFSC), where producers sell their products directly to consumers, or through one intermediary (EU Regulation, 2013) to reduce the negative externalities of the transactions and maximize their value.

6

1.2. Problem Discussion

Society views agriculture predominantly as food production which has led to a very economically rational model in which the main drivers are the intensification of production to achieve economic efficiency (Novikova, 2014). This means that large distribution companies have increasingly become the main link between producers and consumers creating an imbalance in the relationship between producer-distributer, as the bargaining power of food producers is reduced. In this situation, large distributors are in control and have the capacity to influence and conduct demand, which generates dissatisfaction for both producers and consumers and their power to influence the market (Elghannam, Mesías, Escribano, Fouad, Horrillo & Escribano, 2020). Research also shows that producers who supply their products through long CFSC´s create a physical and social distance between the producer and the consumer (Daving, 2018) which detaches the consumer from the source of their necessities. The development of global logistic networks may facilitate the commercialization of food from different countries which can be seen as positive for consumers, who find more variety of food at more reasonable prices. However, it also causes negative aspects due to the environmental impact of transport, and the loss of income of local producers who lack the power to fully compete in this market (Elghannam et al. 2020). That is why consumers are becoming more motivated to buy locally produced food that value the quality, environmental motives and information of the origin of food (Daving, 2018). They now seek a more direct connection with food producers through alternative food systems, thus avoiding the various intermediaries in the SC, which facilitates food traceability and better price transfer between producers and consumers (Elghannam et al. 2020).

Civil society also realize the negative long-term consequences of the conventional food system and are pushing for new ideas and models of distribution and commercialization. These are put into practice to challenge the status quo and provide the consumers with the choice of supporting a resilient and sustainable model of domestic agriculture (Kneafsey, Venn, Schmutz, Balázs, Trenchard, Eyden-Wood & Blackett, 2013). An example of this is the development of channels called SFSC´s, which can generate great opportunities for agricultural producers, who establish direct contact with their customers and increases the added value. SFSC´s have arisen as a promising sustainable alternative, in terms of economic, social and environmental benefits (Elghannam et al. 2020). However, there is a need for more research in the field as its showing to be a growing trend in the food industry (Uribe, Winham & Wharton,

7 2012). Research on the operational reality of these chains have a consistent focus on consumers, and their motives and participation in such production. On the other hand, the producer participation and perspective in SFSCs have only received a small share of attention. To further support the development of alternative food chains, an important question to be answered is how to increase the producer participation in these markets (Charatsari, Kitsios & Lioutas, 2019). For that to happen, better conditions are needed for producers to have trust in the future of their business and continue supporting the shift to more sustainable SC´s.

1.3. Purpose

The overall purpose of this study is to contribute with knowledge about SFSC’s development from a producer perspective. The focus in this paper is to explore what advantages and barriers producers experience when operating within a short food supply chain (SFSC).

8

2. Frame of Reference

___________________________________________________________________________ The frame of reference will introduce an overview of the previous research within the topic and related theories. The first section entails the methods used for searching and collecting the literature. Furthermore, the frame of reference was used as a tool when analysing the empirical findings.

___________________________________________________________________________

2.1. Method for constructing the frame of reference

The collection of relevant sources for this paper began with a systematic search for existing literature, including previous research and relevant concepts within the field. Relevant articles have been accessed through multiple online databases. These included Google Scholar, Springer link, Sage Journals, JSTOR, and the Jönköping University web library. Initially, Google Scholar was used to develop a broader understanding of to what extent the topic has been researched. When reviewing the literature, different keywords were used in the search engines, including: Short Food Supply Chains, Food Supply Chains and Sustainable Supply

Chain. The term “short food supply chain” generated 6003 articles published between

2005-2020. From these searches, several articles were selected and analysed which gave further insight into the topic. These searches brought the authors to further fields of study related to the topic, which led to a more detailed search, including search terms such as: proximity supply

chain, food systems, food security & resilience, Circular Economy, lean management, green distribution, innovative forms of food commercialization and local food systems.

Limited research has been performed on SFSC´s, despite this, most of the used articles are peer-reviewed from respectable Journals in the field. In other cases, deeper research has been done on the background of the authors and their previous publications to determine the credibility and quality of the material. Moreover, other criteria were considered when analysing the articles. First, the quality of the content, both in terms of the reliability and its relevance to the topic. Secondly, the year it was published. The majority of the cited articles are within the last 5-10 years, to provide a relevance of the circumstances in today’s marketplace. After a systematic review of existing literature, a frame of reference was constructed to help fulfil the purpose of the study.

9

2.2. Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC)

Alternative food systems are becoming more popular, this could be seen as a reaction to the deterioration of the quality of communication and the relationship between suppliers and consumers about issues like the origin of the food (Zhu, Chu, Dolgui, Chu, Zhou, & Piramuthu, 2018). Many have challenged the issue and found new ways to organize around food systems using the concept of Short Supply Chain (SSC), as it allows for increased awareness about the conditions under which the food production occurs, among other benefits. The concept of SFSC´s is associated with terms such as “local food systems” and “direct sales”. These are all concepts that differ from each other, “short” does not always mean “local” (Galli and Brunori, 2013). That is why it is very important to give a background of this concept and identify criteria for its proper use. The two most basic criteria are physical distance and social distance. These terms refer to the proximity or distance between production and consumption when comparing to CFSC´s:

• Physical distance (proximity) is the distance of transportation (food miles) that a product travels from its production site to the sale point. Some researchers propose to extend the definition to the production and sale of inputs (e.g. fertilizers, animal feed). A common way to incentive SFSC´s is to set a radius of distances that serve as benchmarks for a product to qualify as coming from an SSC (Galli and Brunori, 2013).

• Social distance (proximity) refers to the number of intermediaries between consumer and producer. In food SC´s, the number should be minimized to zero or very few. In the case of an intermediary, it should act as a way to connect the two instead of disconnecting them (Galli and Brunori, 2013). For example, there are cases of farmers forming cooperatives that sell their products through consumer managed shops which could be considered a CFSC´s. In this case, the number of intermediaries should not be the main factor of social proximity. As the goal is to make connections between society and the producers, it is very important to consider the quality of the relationship, not only the number of intermediaries. The goal of this social proximity is to establish effective control communication and receive feedback including quality features, farming practices and ethical values of the process (Galli and Brunori, 2013).

10 There are different forms of SFSC´s, but they share a common characteristic of social proximity. From a customers' point of view, SFSC´s transfer more complete information about the origin of the food, and, for producers, SFSC´s retains a higher share of added value. A study found suggests the differentiation between 'traditional' and 'neo-traditional' SFSCs. Traditional SFSC´s are farm-based, in rural locations, usually operating using traditional production methods. The "neotraditional" are seen as slightly more complex collaborative networks that are often off-farm (e.g. delivery schemes) and foreground strong ethical and social values (e.g. organic production). Both models can be equally innovative, and in many cases, people combine characteristics from both (Kneafsey et al. 2013). In this paper, on the basis of European Union subsidy policy (Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013), SFSC’s are defined as “where producers sell their products to consumers directly, or through one intermediary” (EU Regulation, 2013).

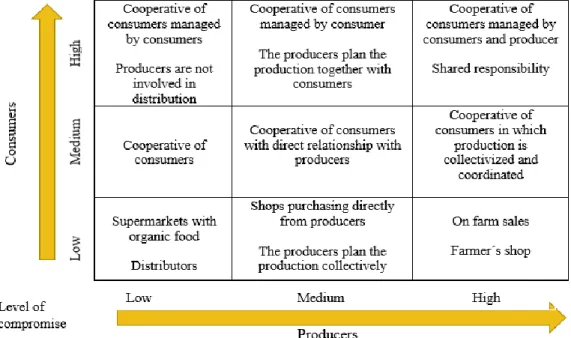

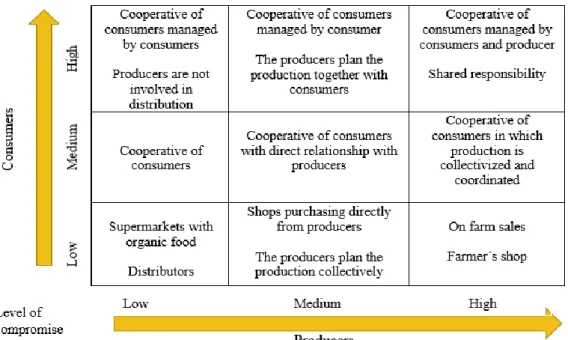

A study made by Jarzebowski and Pietrzyck (2018) proposed three main types of short food chains on the basis of the number of intermediaries, physical distance and organisational arrangements (Figure 1).

Figure 1. SFSC classification based on level of compromise between producers and consumers (Jarzebowski and Pietrzyck, 2018, p. 200).

11 As seen in figure 1, SFCS´s take place in different ways, depending on the level of compromise among consumers and producers. The type of SFSC´s that are being explored in this study would most likely be categorized as a low level of consumer compromise as they are not organized as a cooperative but buy as individual customers. And medium/high levels of producer compromise as the people buy directly from them but do not plan production collectively. There are many models of SFSC´s in Sweden, among them are farm shops, farmers’ markets, delivery of vegetable boxes by subscription, mail-orders, producer co-operatives, solidarity purchasing groups, and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) (Kiss, Ruszkai & Takács-György, 2019) and (Marsden, Banks & Bristow, 2000). It is also important to state that there are many examples of food producers using a mix of SFSC´s, or combining them with longer chains to build resilient routes to market and reduce risks from market volatility. Below is a description of each of the SFSC types of commercialization channels that will be referred to in this study:

REKO “Ringen”

The REKO channel organizes a place where customers and food business owners meet temporarily to complete the deal (National Food Agency 2018). Customers use digital ordering systems to buy local produce through Facebook groups and they meet the producers at a specific time and place to complete the exchange. The REKO channel is categorized as a “Face-to-face SFSC” in which a consumer purchases a product directly from the producer/processor on a face-to-face basis, where authenticity and trust are mediated through personal interactions (Galli & Brunori, 2013).

Bikupan Kooperativ

Bikupan is a grocery store cooperative located in Jönköping. The local shop is an example of SFSC´s since their products focus on being local, aiming to have as small distances as possible to the producers (Bikupan). This type of chain can be categorized as a “Proximate SFSC” which extends beyond direct interaction and delivers products which are produced and retailed within the specific region (or place) of production (Galli & Brunori, 2013).

Farmers Market

Farmer's markets are another example of SFSC´s in Jönköping. Once a week a temporary market is organized in such a manner that local producers of food gather to sell their products. This type of market functions all year round and the amount and variety of products depends

12 on the season and the farmers. In comparison to the REKO, the farmers market works as a local shop in the sense that producers don’t know how much they will sell since it depends on uncertain consumer demand at the specific time and place. This type of SFSC is also categorized as a Face-to-Face.

Sales on Farm

Several farmers in Jönköping whose products are demanded decide to open their own sales channel by having a so-called "farm shop". Customers can visit the farm and purchase the goods face to face from the food producer and can see where the products are produced. Farmers usually don't use this channel as their main one but as an additional income by seizing the opportunity if customers are willing to visit the farm location to buy products (Ahearn & Stearn, 2013).

Conventional Retailer

Some food producers using SFSC`s also use CFSC´s if they have enough products to cover the demand from bigger retailers, in both cases, intermediaries can be one or less. The products are sometimes sold to geographic areas that are not considered as "local" but still transmit the information of its production place and methods to the consumers. Therefore, this type of channel is defined as a “Spatially extended SFSC” where the value transferred to consumers who are outside the region of production itself (Galli & Brunori, 2013).

2.2.1. Why Are SFSC´s Relevant Today?

The scientific community has been studying the biophysical threats that put most pressure on our food system and among them are population growth and climate change. Following this, according to one source, a forecast of the main factors that will influence the future global food system estimates the world population to increase to 9 billion by 2050 and that climate change will cause more extreme weather and higher temperatures altering precipitation (Sundström, Albihn, Boqvist, Ljungvall, Marstorp, Martin, & Magnusson, 2014) further pressuring the stability of food production. Acknowledging that the status quo of the modern conventional food system is unsustainable, have pushed SFSC´s principles to be applied as social innovations, like the example of REKO, which challenges the dominant system of food production and commercialization. Given the fast rate at which environmental change is

13 happening, the main risk for society is to have to make decisions about their food system model in an emergency, since that would limit their opportunity to experience these beneficial social innovations.

The food system's negative effects on the environment appear mainly at the production level but also those of consumption and distribution (Gallaud & Laperche, 2016). To simplify the complex reality of the impacts, there are two common views about the unsustainability of modern agriculture. The first one is that there is a lack of ecological ethical values which creates a kind of moral hazard situation in which the agricultural actors are not incentivized to behave sustainably as they do not suffer the consequences directly. Secondly, there is a worldwide trend towards larger and fewer farms (Buttel, 2006). The latter implies that the producers are using productivist methods of production which are found to be major causes of its unsustainability. The causes according to Buttel (2016) are:

1. The specialization/monoculture and the creation of spatial homogeneity.

2. The intensification of production through expanded use of external chemical, energy, and irrigation inputs.

3. The concentration of livestock in space and the spatial separation of crop and livestock production.

Buttel (2016) defines unsustainable systems as those that will at some future point be rendered dysfunctional because of ecological problems, risks, or calamity. Yet, contemporary unsustainable agro-food systems have an enormous amount of staying power and a capacity to maintain their dynamics despite socioenvironmental costs and risks (Buttel, 2006). Sweden follows the trend of the number of farms decreasing while the average size of the farm's increases, as the international competition in the EU intensifies (Daving, 2018). To avoid the negative externalities created by the current model of production, diversification of sources that use alternative ways of producing and selling food may be beneficial. A healthy strengthening of competition should bring more jobs, open landscapes, and lively rural development. The Swedish National Food Strategy Report (2017) states:

“The overall objective is a competitive food supply chain that increases overall food production while achieving national environmental objectives, aiming to generate growth and employment and contribute to sustainable development. The increase in the production of food

14

should correspond to consumer demands. An increase in production of food could contribute to a higher level of self-sufficiency.”

The EU commission also stresses the importance of establishing SFSC´s as alternative ways to distribute food for small and medium-sized enterprises (Daving, 2018). Therefore, this trend has the potential to motivate newcomers in the form of full time or part-time farmers to join the market and support healthy competition by increasing the sources of food, if done responsibly. For this to happen, the logistics of the sector must show transparency, accuracy, and responsiveness to maintain consumer confidence (Turi et al. 2014).

In Sweden, the degree of self-sufficiency has in recent decades decreased which has required a higher degree of food imported from other countries (SCB, Jordbruksverket, Naturvårdsverket & LRF, 2012). Some municipalities in Sweden have an agenda to ensure a higher degree of self-sufficiency by incentivizing local producers and achieving sustainable goals (Granvik, 2012). Among the trends are, for example, the adoption of alternative SC strategies by local food producers, including hobby farmers, who are seeing a growth in demand their products as consumer and civil society change their preferences and purchasing behaviours (Daving, 2018). SSC´s in the food industry have the potential to support local farmers that want to sell their products and receive a fair price for their goods (European Network for Rural Development, 2016). Selling through SFSC´s is popular among small and medium producers who usually receive a higher share of the market price. But that does not necessarily mean more profits, actors may receive lower average profits due to the added labor requirements of their direct sale strategy (Kneafsey et al. 2013).

2.2.2. SFSC´s as a Driver for Sustainable Development

The evaluation of SFSC´s goes hand in hand with the social and environmental benefits which fits into the field of Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Shortening the SC may have some beneficial effects on the environment, economy, and society, however, it should be noted that the way in which the SC is shortened is important. All short supply chains do not necessarily bring the expected benefits, they will only do that if the production and distribution systems in the SC are geared to sustainable development. Examples of practices that drive sustainable development are increasing the farm value-added (profit allocation), promote sustainable

15 farming systems, diversify production, and contribute to local economic development (Jarzębowski, & Bezat, 2018). The doubts about the economic relevance of SFSC´s are mainly related to the consideration of costs of small productions compared to intensive agriculture and large farms, in particular considering the cost advantages of economies of scale, as well as the costs if the geographical area is unsuitable for a specific production (Canfora, 2016). Additionally, the distribution of the economic value created has shown to be highly imbalanced among the actors, where most of the value produced goes to large retailers and agricultural producers only see a small share of the total (Gallaud, 2016).

Food producers that use CFSC´s are one of the reasons for the increase in usage of resource-intensive techniques, but also for the increase of energy- and emission-intensity in the global food system (Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017). Supporters of SFSC´s emphasize the inefficiencies of CFSC´s and realize how a shorter one can make the traceability of products easier by allowing a better flow of information, making it easier to put the necessary pressure on unsustainable actors and opening opportunities for a more efficient system. Representatives of science also recognized the importance of the SC management process in the agri-food sector primarily due to the instability of products and the need to improve product flow tracking (Hobbs and Young, 2000). The proximity of the actors within a SFSC can create a more reliable distribution that is in many cases accompanied by an effective ordering system and better information flow overall. Research also shows that SFSC´s play a significant role in agrarian-based rural development where values are developed through the creation of new networks in local communities: “SFSCs can be seen as a way of organizing food transactions where consumers and producers can rely on more informal and social-based governance mechanisms” (Daving, 2018). To summarize the overall positive effects of SFSC´s, the authors suggest four main ones based on Gallaud´s (2016) description of “fair-trade SFSC´s”.

Economic: High level of organization (autonomy), reduced expenses and costs, fewer intermediaries, and improved quality of work. In most cases, fewer short-term economic uncertainties are resulting from communication issues, varying production, and sales volumes.

Environmental: Considering environmental externalities of activities, repurpose of unused resources, and investment fostering ecological transition. The use of SFSC´s is correlated to the use of organic farming methods of production which reduces impacts on the natural

16 environment. The shorter physical distance between producer and consumer also aims to reduce the transport emissions created.

Social: Involvement in trade and search for fairer exchanges, taking human resources into account and creation of jobs. In many cases, SFSC´s have been brought forward as a type of social innovation where it is defined as “a form of economic exchange focusing on social bonds, cooperation, transparency and fairness between the actors in the exchange”.

Regional: Reuse of regional resources, the proximity of actors, and interconnection of activities and networks.

In general terms, SFSC´s can act as drivers for change and a method to increase trust, equality and growth in agricultural, food, business, social, health, and rural policy areas (Galli, Schmid, Brunori, Graaf, Prior & Ruiz, 2014). The opportunities for collaboration and the increased power over the SC allows producers to innovate and adapt to their individual conditions through the way they commercialize their products and other processes. Literature shows they are growing in popularity but their role in developed countries food trade is shown to be limited. One of the main issues for shareholders supporting this business model seems to be the economic viability of operating through SFSC´s. Organizations that operate them are very often part of the social and solidarity economy whose objective is to fulfil a mission involving societal needs, which are generally externalized by the market. Small-scale food producers and

their higher costs can be a threat to their longevity, which may explain why many of them are “profit sufficers” or “welfare maximisers” instead of profit maximisers (Kneafsey et al. 2013). Therefore, the reduction of expenses and costs are not necessarily the priority objective for many SFSC actors. For example, businesses that seek to work with local raw materials will quite often face higher costs compared to the cost of imported materials from other countries (Gallaud, 2016). Some researchers can be sceptical about the benefits of SFSC channels so it would be dangerous to accept the disputed or disputable issues as absolute truths (Kiss et al. 2019). In addition, more empirical research needs to be performed to further understand the extent to which this type of alternative food chain is sustainable and feasible.

17 2.2.3. Barriers to the Implementation of SFSC´s

Since part of our purpose is to understand the barriers that small and medium producers currently face, several obstacles have been described by Gallaud´s (2016) book concerning the successful attainment of the positive effects of SFSC´s. The main one is that usually, the first thing that the food producer will do is to evaluate the economic viability of his decision i.e. if operating through SFSC´s will improve the profit margins compared to conventional alternatives. The improvement is rarely attained due to the difficulty of raising prices above-market prices. This limits the opportunity for increased economic wellbeing, but when analysed in relation to how they feel about their professional activity, most producers in SFSC have become prouder of their work as they engage with the consumer demands for the more responsible production of food (Gallaud, 2016).

As mentioned earlier, selling directly to consumers allows the producer to have increased autonomy over the organization, in some cases, this is considered an obstacle as it usually results in a greater mental load in the organization of work. For example, the diversity of types of commercialization can require knowledge about marketing or logistics that retailers would have been in charge of otherwise. However, producers who sell through SFSC´s usually have a higher educational level, the need for additional skills can be experienced as an opportunity instead of a constraint(Gallaud, 2016). Another issue is the logistic optimization of the delivery of food to its sale point. In SFSC´s there are smaller quantities to be delivered and trucks are not always loaded and often return empty. For the moment, the logistics organization is a major impediment to the development of some SSC´s (Gallaud, 2016). SFSC´s are also limited by external factors such as the regulatory framework which disproportionally increases the costs involved for smaller producers given the nature of their smaller economic power (Galli and Brunori, 2013). Given that the food industry is a highly regulated field, the SFCS are equally subjected to these regulations. These involve rules of food health, standards, hygiene, and certifications that are often tailored to industrial companies and represent a constraint to the development of SFSCs. For this reason, public sector authorities face the challenge of not only needing to identify ways to support the development of the sector but also having to refocus their role from legislative enforcer to legislative modifier (Galli and Brunori, 2013).

There are also social barriers that limit the positive impacts of SFSC´s; the individual and community attitude toward the field of agriculture is a key determinant for pursuing sustainable

18 entrepreneurial opportunities such as incorporating agro-environmental concepts while achieving more productivity (Dias, Rodrigues & Ferreira, 2019). Productivity is limited in SFSC production methods as farmers favour the organoleptic quality (organic farming for example) which can lead to higher costs. Therefore, product prices are highlighted as a significant factor blocking the development of these types of chains since many do not have the income to purchase food through them (Gallaud, 2016). Another issue is that given the nature of the reduced distances in SFSC´s, the developed mutual commitment and trust between producers and consumers often substitute or reduce the need for formal confirmation of certain qualities materialized in forms of certificates and labels. This can be seen as an advantage as there is a reduction of agency costs for the producers who can invest their resources on their business instead of buying certifications for example. However, this also can make SFSCs vulnerable to misuse as some producers take the chance of selling unsustainable produce through a channel that takes responsible production for granted (Galli and Brunori, 2013). Finally, there are external factors such as the uncertainty of weather conditions and seasonal variations that are very influential in the success of SFSC´s since farmers that practice this method often follow the natural seasonality of products (Galli and Brunori, 2013).

2.3. Supply Chain Management (SCM), Circular Economy (CE) & Lean

Management

2.3.1 CE & Food Supply Chain Management

Circular Economy (CE) is one of the most popular concepts in the field of economic sustainability, especially in the European Union which promotes it as contributing to sustainable development (Moraga, Huysveld, Mathieux, Blengini, Alerts, Van Acker & Dewulf, 2019). To achieve this, the model implements environmental thinking which aims to circulate the flows of resources in the economy, as opposed to the "linear flows" that currently dominate. (Kiss et al. 2019). In other words, it is intended to optimize the use of resources, reduce waste, and is based on re-using and repairing materials to support sustainable supply and responsible consumption (Gallaud, 2016). The theoretical principles of circular economies are often implemented throughout the SC strategies, the connection between Supply Chain Management (SCM) and CE can be drawn from the fact that their main objectives include creating an advantage by increasing resource efficiency and minimizing waste. These

19 characteristics are very similar to the Lean SCM principles (De Angelis, Howard, & Miemczyk, 2018) which will be covered later in this theoretical framework.

CE is relevant for the food industry since it is known for creating a lot of waste, especially in the fresh food market. According to FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), within Europe alone, two-thirds of food waste occurs within SC´s. (Colbert, Schein, & Douglas, 2017). Colbert et al. (2017) also states that “There are very little research and data on food waste in the middle of food SC´s, with most research to date focusing instead on post-consumer waste”. Excessive food waste is a sign of inefficiencies and structural problems which often relates to an imbalance of power among SC actors. Colbert et al. (2017) explains in their paper that food waste is caused by an inefficient allocation and concentration of power, meaning that supermarkets and other powerful actors pressure suppliers by changing demands frequently without any supervision by regulatory bodies that protect the producers. If the system works for the benefit of specific actors in the chain, in the long run, the imbalance and inefficiencies can threaten the food security and lead to a reduction in investment in small and medium producers who are restricted by the demands from their upstream SC. This will ultimately impact consumers, with higher food prices and reduced choice (Colbert et al. 2017).

2.3.2. Opportunities for a More Circular Economy in the Food Industry

The CE model offers practicalities of how to prevent the food waste generated at any stage of the food chain through different methods, these include; redistribution of unsold and surplus food, improving the in-store promotion and stockpiling, reducing package sizes and stimulating or improving consumer perception and different consumer habits (Kiss et al. 2019). Among the objectives of the CE is the use of recyclable materials and the promotion of transparent information in terms of food origin and quality. In global food chains, it’s difficult to trace the origin of food and under what conditions products were made (Opara, 2003). On the other hand, as SC´s become shorter, the traceability of products is improved and thus consumers can access more trustworthy information about the purchased products. With more information, consumers can make sustainable purchasing decisions that are in line with their own values. Moreover, in SSC´s, the producers use very limited or zero materials in their packaging and processes which is due to the circumstances and the nature of their sales activities. With a close social and geographical proximity in SFSC´s less waste and transport emissions may be created

20 compared to CFSC´s. From this, it can be concluded that the aspects of SFSC´s and CE form a close link with the economy, environment, and society (Kiss et al. 2019).

2.3.3. Lean Management & Flexibility in Supply Chains

Companies always search for ways to reduce their operational cost while remaining the quality of their products or services. Lean practices are a set of business processes that relates to waste reduction in different ways and that has shown to add value to customers (Melton, 2005). Waste in this context relates to any activities that do not add any value to the end customer. Food waste occurs at any point in the SC, from the harvesting process to the transportation and storage process. Lean food SC´s can have a huge impact on the economic, social, and environmental impact of business (Vlachos, 2015). The difference between lean thinking and circular economy is that lean thinking also deals with the minimization of waste in the form of inventory and lead times.

There is a magnitude of food SC´s in the world and they all have altered levels of complexity. Local SC´s are often more sustainable than international food SC´s since they are shorter and thus create fewer negative socioenvironmental externalities. On the other hand, it has been more difficult to implement lean practices in CFSC´s due to their increasing complexity and length. Complexity may contribute to a lack of visibility and also a smaller understanding of costs (Sjögren, 2014). To manage the complexity, the concept of flexibility can serve as a way to increase responsiveness in cases of disturbances in SC´s. The literature on flexibility in SCM is a source for several definitions of the topic, we chose Kopecka, Penners, & Santema (2009), one that explains the flexibility of a company´s SC in terms of two aspects; the first one being the buyer-supplier relationship, where emphasis is put on the uncertainty in the relationship between the focal firm and its partners given that circumstances are constantly changing. For that, trust plays an important role as there is a need for the quality flow of information. The other aspect deals with production or manufacturing. The flexibility of a company´s SC can be divided into three different factors. First, the ability to produce several different products simultaneously. Second, the ability to change the volume of production and variety of products in the short-term. And lastly, the ability of a system to reduce the number of orders. The general definition for flexibility in SC´s is; the possibility to respond to short-term changes in demand

21 or supply situations or of other external disruptions together with the adjustment to strategic and structural shifts in the environment of the SC (Kopecka et al. 2009).

3. Methodology

___________________________________________________________________________ In the following chapter, the authors clarify the method applied in this study. In the first section the research philosophy and research approach are presented. Followed by the methods used for data collection, the design of the interviews and a description of how the data has been analyzed. Lastly, the trustworthiness of the research is discussed.

___________________________________________________________________________

3.1. Research Philosophy

The term “research philosophy” relates to the nature of knowledge and how it develops (Thornhill et al. 2009). A research paradigm is the philosophical framework that guides how research is conducted based on the people's assumptions about the nature of knowledge. The two main paradigms are positivism and interpretivism (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The authors have followed the interpretive approach to social research since it considers subjectivity as the main element of interpreting the subject. The positivist paradigm is related to a realism approach to philosophy where objectivity is assumed and involves a deductive reasoning to explain the subject of the study. Moreover, the interpretivist research paradigm focuses on exploring a social phenomenon with a view of gaining interpretive understanding. Whereas positivism focuses on measuring social phenomena, interpretivism focuses on exploring it, using qualitative methods (Collis and Hussey, 2014). This study investigates the concept of SFSC, and what advantages and barriers producers operating in them experiences. Given that the phenomenon under consideration is unmeasurable, and the uncertain nature of this research topic, the interpretivist paradigm suits the purpose of this study. Formulating an interpretive understanding of the phenomenon was essential to understand the realities of producers operating in these SC’s.

22

3.2. Research Approach

The problem under investigation is quite broad and not clearly defined, thus it is categorized as exploratory research. This type of research is conducted when the current state of literature regarding the topic is in its early stages or non-existent. An exploratory study aims to look for patterns and ideas instead of testing a hypothesis (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Given the unstructured nature of our open-ended focus and the aim of further understanding the reality of the topic, this approach will allow the authors to understand the phenomenon as they are unsure of its precise nature (Thornhill, Saunders & Lewis, 2009). The authors aim to develop a study that gives a deeper understanding of the subject, therefore, an inductive research approach is a reasonable choice to understand the underlying mechanisms that constitute the social phenomenon. Moreover, in contrast to a deductive approach, the focus is not on the outcomes or results of human behaviour, but on questions regarding why and how a particular result have emerged (Reiter, 2017).

Moreover, the authors have evaluated the two most popular forms of research being qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Our choice is to perform a qualitative methodology since it is grounded on the interpretivist paradigm. The quantitative approach does not suit the purpose of this study since it aims to quantify social phenomena by collecting numerical data which does not suit the purpose of this study. On the other hand, qualitative methods are mainly used to answer questions about the meaning, perspective, and experiences, often from the participant's standpoint (Hammarberg, Kirkman, & de Lacey, 2016). Thereby a qualitative research approach was chosen as the best approach to obtain first-hand knowledge to realize the advantages and barriers food producers currently face when operating in them.

Furthermore, the authors aim to develop a general theory and a conceptual understanding of the subject to address the research purpose. In addition, this exploratory study focuses on generating useful insights that can act as a foundation for further research within the field of SFSC and on how producers experience the reality of their operations.

23

3.3. Data Collection

The data collection for this study began with a systematic search for available research within the study field. After getting a broader picture of the previous literature within the field, the authors narrowed the scope of the research and reviewed the most relevant literature and theories that connect to the topic and which are presented in the frame of reference section. The method for how the data was collected is being explained in detail in section 2.1., "method for constructing the frame of refence".

The primary data in this study has been obtained through 6 semi-structured interviews with the aim of obtaining in-depth insights about the producer’s operational position in the current market situation. The selected participants where operating in different SFSC´s which are located in the surrounding geographical area of Jönköping. The majority of the participants has been accessed through an organization called “REKO-ringen”. This is an organization that supports farmers and other food producers to commercialize their products through SFSC´s. The Facebook group for REKO was used to find informants, in combination with using the snowball sampling to find other participants. The snowball method was used to find some of the members of REKO whereas other relevant participants recommend other participants (inside and outside of REKO). The snowball effect is particularly useful to use in the process of selecting the producers because they could provide names to other producers that were relevant for the research (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981). Other participants have been selected based on the criteria of Swedish food producers operating in SFSC´s. The food producers that have not been accessed through REKO, are operating in other SFSC channels with the maximum of one local intermediary between producer and consumer. Due to the current Covid-19 situation, 2 interviews have been conducted digitally with video conferencing. The other 4 interviews were conducted face-to-face with the participants.

3.3.1. Interviews

Interviews provide a deeper understanding of a phenomenon (Bryman, 2008) and will be used to understand the motives and values that the SFSC´s channels delivered and captured to producers. It was particularly important to interpret complex expressions, but also to understand and depicture the complexity of the business from the perspective of a food producer.

24 The semi-structured interviews consist of open-ended questions. Open-ended questions are ones that cannot be answered with "yes" or "no", but instead require a longer and developed answer (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The author's motivation for using open-ended questions is to get in-depth insights from the answers, but also to allow a discussion to take place with the participants. In semi-structured interviews, the researcher prepares some questions that will cover the main topics of interest but will allow for some flexibility as new questions might appear during the interview based on the interviewee's responses. In distinction to structured interviews where questions are presented in the same order to all respondents (Collis and Hussey, 2014). An interview guide has been prepared to guide and control the conversation onwards and make sure the valuable topics are being covered. The producers operating in SFSC´s do operate under different conditions, in terms of the overall size of the farm, what products they produce, and the magnitude of their operational network. It is important to consider the context of each of the participants to make a sound analysis of the outcomes of the subject under investigation and the authors must adapt and adjust the questions to each case. In order to develop in-depth knowledge of each of the specific cases, follow-up questions have been asked, such as "how" and "why". This can give useful insights that otherwise might have been lost. The general design of the interviews is to provide a structure that allowed the interviewees to freely express themselves, to get the full picture of their business operation. The interview guide can be found in Appendix A.

3.4. Data Analysis

The interviews have been recorded and transcribed using a thematic analysis. The thematic analysis was chosen due to its flexibility and the non-requirement of using a detailed theoretical approach (Nowell, Norris, White & Moules, 2017). Nowell et al. argues that the thematic analysis is a useful method for examining the perspectives of different research participants, highlighting similarities and differences, and generating unanticipated insights. There are two main ways the themes can be identified in a thematic analysis. Either through an inductive approach or a deductive approach. The researchers have conducted the analysis using an inductive approach, meaning that the themes derived are strongly linked to the data collected (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Moreover, this study is exploratory and inductive, thus a data-driven analysis is better suited for this purpose as opposed to a deductive and analyst driven analysis.

25 The analysis will take place mainly at the semantic level, where the themes are identified from the surface meaning of the data but will inevitably touch upon latent themes as there were some discussions on the underlying assumptions to explain the nature of the findings. That means that the authors have described and presented the data in an organized way and show patterns in the content with the attempt to explain the significance of their broader meaning and implications in relation to previous literature. The research epistemology on this paper uses an essentialist/realist approach, where the authors theorize the experiences and meaning of the reality of the participants. It is assumed that their articulations are the source of meaning in this case, without theorizing the socio-economic contexts (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

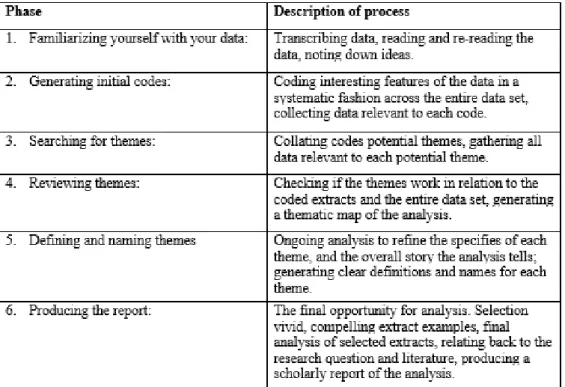

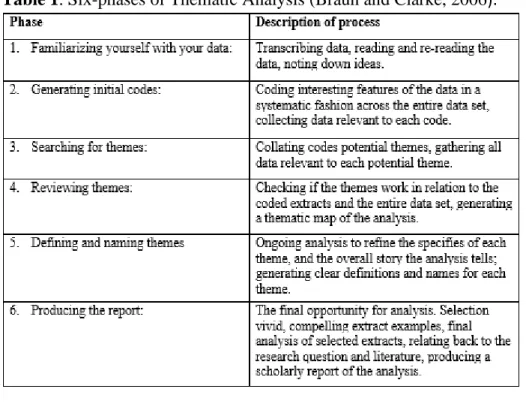

To produce a sound analysis, the six-phase procedure suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) has been be conducted. As pointed out by Braun and Clarke, the analysis is not a linear process, but a flexible and recursive process where you can move back and forth throughout the phases. The six-phases are presented below in table 1:

Table 1. Six-phases of Thematic Analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

The interview transcripts have been coded to identify interesting features and patterns from the data. Subsequently, the procedure of the thematic analysis will find common themes from the codes, with the objective of achieving the purpose of this research. As this study is inductive in nature, the themes developed from this analysis are strongly linked to the data obtained from

26 the interviews. To demonstrate how the procedures of the thematic analysis were conducted, a figure displaying the initial coding process can be found in Appendix B. Moreover, the emerged themes are illustrated in the analysis section (5.1, see figures 4 & 5). In the analysis chapter the empirical findings have been be analysed according to themes in the light of the previous research and concepts related to SFSC’s.

3.5. Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness and transparency in qualitative research are crucial to the usefulness and integrity of the findings in a study. Trustworthiness refers to the degree of confidence in data, interpretation and the methods used to ensure the quality of a study. What constitutes trustworthiness in qualitative research is classified by four criteria: credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability (Connelly, 2016).

Connelly (2016) argues that credibility, that is the confidence in the truth of a study, is the most important criteria for trustworthiness. Confirmability is concerned with the fact that the researcher’s interpretations and findings are clearly derived from the data (Nowell et al. 2017). The investigation in this research intends to explore and understand the perspectives and behaviours of producers operating in SFSC´s. Thus, to ensure the credibility of this study, the intention has been to reduce the subjectivity and bias of the researcher throughout the investigation process. Hence, the authors allowed the participants to engage in the data analysis by confirming the accuracy of the findings. The participants viewpoints have been taken as feedback and some corrections have been made in the data to further increase the credibility and generate a better reflection of the reality. This also enhances the confirmability of the study, as potential researcher bias is reduced. Moreover, given the inductive approach in this study, the procedures of the thematic analysis have ensured that the findings are clearly derived from the data. In addition, the procedures of how the findings have been derived from the data can be found in the appendix (see appendix B, figure 4 and 5).

The dependability refers to the consistent and logical process of the research. The dependability is judged by the readers ability to follow the research process (Nowell et al. 2017). The authors have strived to document the research process in a clear and logic manner and with rich descriptions of the study methods. Hence, assuring that future readers and researchers

27 establishes an understanding of the research processes, and thereby would be able to repeat the study under the same conditions.

Transferability is concerned with the generalizability of the study, which refers to the whether the findings can be applied to other situations and populations (Nowell et al. 2017). Given the narrowed scope of this research and its focus on particular individuals, the researchers cannot assure that the findings would be applicable to other situations. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to knowledge about SFSC’s and investigate specific producers operating within these. Rich descriptions of the methods used are outlined in this paper, to allow those readers who seek to transfer the findings to judge the transferability of this study (Nowell et al. 2017). Triangulation methods is used in research to enhance the trustworthiness of a study, and it allows for a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under consideration (Carter, Bryan Lukosius, DiCenso, Blythe & Neville, 2014). One type of triangulation is method triangulation, which implies a usage of several methods for collecting data. This study will only use one method for collecting data, which is interviews. Focus groups were also considered but given the logistical challenges to gather interviewees in one place when they are located far away from each other, this option was disregarded. It was also deemed inappropriate given the circumstances regarding Covid-19 and the recommendation of seeing as few people as possible in person. A few of the interviewees are also in some sense competitors, which could have made the participants less willing to answer questions openly. Another type of triangulation is investigator triangulation. That is when more than one author is being involved in the research investigation (Carter et al. 2014). This study includes three authors, and the number of authors participating in the interviews has varied to allow for a wider perspective towards the findings. Data source triangulation will also be an important part of this study to ensure trustworthiness and credibility. This method of triangulation uses several sources of data in order to further increase the validity, but also the richness of information, of the study. For this study, interviews will be held with different individuals, all working within SFSC´s in different ways. Furthermore, to avoid potential ethical conflicts, all participants were given a consent form before the interview where participants were informed about the purpose of the interview and the research, and why they were individuals of interest. They also agreed to be recorded and were informed about their right for anonymity, and a chance to look at, and approve, the transcripts from the interviews.

28

4. Empirical Findings

___________________________________________________________________________

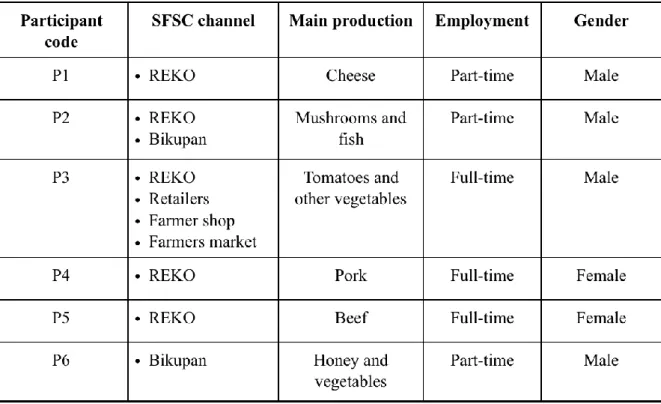

This section outlines the findings derived from 6 semi-structured interviews. The objective was to get a better understanding of what advantages and barriers producers operating in SFSC´s might experience. The participants will be referred to their respectively code which is displayed in table 2. The findings are displayed under two headlines; Advantages and Barriers, with subsections according to preliminary themes that arise in the findings.

___________________________________________________________________________ Table 2. Characteristics of the participants

.

4.1. Advantages

4.1.1. Logistical Advantages

More than half of the respondents stated that one of the motives for using SFSC´s like REKO as a commercialization channel was the convenience and flexibility of the ordering system. Both the part-time and full-time producers in the interviews said that they often harvested or produced according to the pre-orders settled through their REKO channel.

29 “Because we produce according to the orders we get, we have a very good sense of how

much we need to produce every week.” (P1)

“I talk with the other producers in REKO and it is rational to choose a channel where consumers can pre-order and smoothly pick it up at the location.” (P2)

As seen in the second statement, it was not only the ordering system that allows for better planning of production and logistics but also because REKO offers a centralized pick-up location where consumers can easily reach the producers.

P2 states that the value of their products increases as it gets to the consumer fresher. This was mentioned by all producers when it comes to selling through REKO.

“It is easier to keep the produce fresh. The tastier sorts of food usually are not easy to store for too long.” (P2)

Another advantage that the participants mentioned was that no matter how much you produce in a period of time, and the variability from period to period, they are not hindered from selling directly to consumers. Participant 2 exemplified this statement:

"REKO gives me 2 big advantages: If you have little produce, you can still sell it. Secondly, the consumers' order and I can confirm the order the day before.” (P2)

Many of the producers used the local shop Bikupan in Jönköping as a backup sales channel that was flexible and fitted the needs that their production required.

“What does not get sold in REKO will go to Bikupan, or I and my close ones will consume it” (P6).

The full-time farmer, P3, ran his business with a combination of several different sales channels: a farm shop, sales through retailers, REKO channel, and the farmers market. He was the only one that had a production that was big enough to sell through retailers who also distributed outside of Jönköping. In his case, sales at farms, farmers market, and retailers were his main channels, but also used REKO as a back-up when he wanted to sell additional supply that was not being covered by his main ones.

4.1.2. Higher Margins

“Higher margins, due to no intermediaries”. (P2)

P2 among others, expressed that he attained higher earnings when he sells his products directly to the consumer. The producers are not sharing their profit margins with other intermediaries

30 in the chain, apart from when they sell through Bikupan. Other participants expressed that their products have a generally higher price than, for example, products sold at supermarkets:

“The advantage is that if you are the whole chain which also means more work and customers have to pay more”. (P3)

As stated by P3, fewer intermediaries also mean more work and therefore customers have to pay more. With fewer intermediaries in the chain the producers are able, and sometimes even required to charge a higher market price in order to sustain their business. So, it’s important to notice that increased revenue does not necessarily imply increased profits.

4.1.3 Customer Demand

P5 commented that his customers are not very price sensitive.

"Those who buy through REKO are not very price-sensitive" (P5)

The effort seemed to be put into offering the highest quality and producing it through organic farming methods to attract demand.

“From the customer perspective, it’s the quality that makes them come and buy from me.” (P2)

“Selling through SFSC´s care more about the quality of the product since you don't want a

dissatisfied customer” (P2).

As stated by P2, the customer's preference for quality causes the producers to seek to maximize customer preferences by increasing the quality of their product.

Throughout the interviews, the authors also realized that there is increasing customer demand for quality and locally produced food in Sweden:

“The customers that buy at REKO channel are very aware and conscious about quality and organic products. Thus, the producers must adapt to the needs” (P1).

“The local food production can be increased throughout Sweden with the help of organizations such as REKO. The interest and the revenue in locally produced food are

constantly increasing" (P1).

The first quote reveals that the customers, particularly at REKO, are conscious and demanding about the quality and sustainable standards of the products. Furthermore, P1 was aware that

31 producers in these channels must respond and provide products that meet the requirements of their customers. The second quote from P1 reveals that the interest and the revenue in locally produced food are also increasing, thus with the help of SFSC channels such as REKO.

The increased demand among consumers has also contributed to and opened up for producers to distribute their products through different sorts of SFSC channels:

“We didn't think that selling through all these channels was what we were going to do when we started the big tomato crop. But there was more and more demand, so we continued

expanding” (P3).

P3 articulates that the increasing forms of SFSC have introduced new channels to sell his product and allowed for an expansion of his business. The different forms of SFSC's that exist in today's market has also contributed to the consumer's awareness and interest in locally produced food:

“Due to SFSC’s in the form of Bikupan and REKO, consumers are getting more aware and interested in locally produced food” (P6).

Regarding the Covid-19 emergency state, especially one producer expressed her belief that the demand for local food production will increase drastically:

“Oh yes, there will be even more demand now with Corona. People open their eyes and realize how little we are self-sufficient. So, it will only increase in general, I think. My sales

have increased by 100%” (P4).

4.1.4. Information Flow

All participants communicated the social proximity between them as producers and the customers as a major advantage in SFSC’s. One participant stated the following:

“I get feedback from the consumers and it is also nice to be able to talk to them, more value is exchanged.” (P2).

The direct communication between producer and consumer seems to allow a more open exchange of information. P2 pointed out the importance of having a close connection with his customers and forming a local network on food exchange which enabled them to sustain and

32 expand their sales options and allow for increased value in the exchange. Moreover, P1 expressed that the storytelling concept can be utilized in SFSC's:

“We get very quick feedback from customers on our products. Storytelling about your brand and products can be utilized when you sell directly to the customers” (P1).

One participant described that information and knowledge is also shared between producers, creating opportunities for collaboration. P1 elaborates further on this matter and its importance for his business as a part-time food producer:

“This network (REKO) allows us to share information, such as advice, or talk about possible cooperation with other producers. This network is really important for our business” (P1).

Among the participants who did not distribute their products through SFSC´s in the past there were comments made about the opportunities to learn about the different work activities needed:

“Yes, I often think about how much you see from what everyone else does, you learn from each other here. I messed up with many things in the beginning, it is a lot easier now” (P4)

4.1.5. Professional Satisfaction

The producers described that SFSC´s require more time invested in the organization because of being in charge of managing the whole chain. Nevertheless, all of them claimed that they are satisfied with it and some say they wouldn't change to conventional channels even if that meant more profit, as stated by P2 and P5:

“It’s a lot of fun, high professional satisfaction. It has never been my goal to grow as much as cheaply as possible. If you want to make as much money as possible, you should not sell as

I do” (P2).

” This is the best thing I could do, I could not have a better job. I love what I am doing. I usually say that it is a lot of work, not a lot of money, but it is still the most enjoyable work I

know.” (P5)

Another benefit of working through SFSC´s was the heterogeneity in the work activities. Participants stated that the variation of work tasks is rewarding:

“It is great, I love this. I meet a lot of people when I’m doing this and it’s so varied. I never know what my day will be like. I get to do my planning when I wake up” (P4).