VTI notat 25-1998

Road User Behaviour at Work Zones

Summary of Literature Review

Paper and Presentation

ARROWS Workshop

Athens, 24-25 November 1997

i .7Author

Lena Nilsson and'Anders Nyberg

Research division Traffic and Road-user Behaviour

Project number

40066

Project name

ARROWS (Advanced Research on Road

Workzon Safety in Europe)

Sponsor

EC and the Swedish Transport and

Communication Research Board (KFB)

Distribution

Fri

Swedish National Road and

' TransportResearch Institute

Preface

The report contains the VTI contribution to a European workshop arranged by the ARROWS project. It presents selected results and a summarised evaluation of the findings of a literature review. The review investigated road work zone behavioural studies, and was undertaken in the ARROWS project. The list of reviewed literature as well as the overheads presented at the workshop are included as appendices.

ARROWS (Advanced Research on ROad Workzone Safety in Europe) is a project in the Transport Workprogramme within the EC:s Fourth Framework. The project has brought together nine research teams with a multi-disciplinary range of skills and competences to address the safety problem at road works. The nine teams arez.

NTUA National Technical University of Athens, Athens (GR), project co-ordinator SWOV Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam (NL)

BAST Federal Highway Research Institute, Bergisch Gladbach (DE)

VTI Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping (SE) 3M 3M Hellas Limited, Maroussi - Attiki (GR)

CRR Belgian Road Research Centre, Brussels (BE)

CROW Information and Technology Centre for Transport and Infrastructure, Ede (NL) CDV Transport Research Centre, Brno (CZ)

ZAG Slovenian National Building and Civil Engineering Institute, Ljubljana (SI)

The overall objective of the ARROWS project is to improve the safety at road work zones, by reducing the frequency and/or consequences ofaccidents involving road users as well as road workers. A prerequisite, forbeing able to formulate guidelines and standards intended to help achieving the aim, is to gain knowledge, not only about collisions that occur, but also about road user behaviour and conflicts when passing road works of varying designs under different conditions.

The VTI participation in ARROWS is financially supported (5 0/50) by the EC and the Swedish Transport and Communication Research Board (KFB).

Contents

1 Introduction 2 Procedure 3 Limitations

4 Selected results and discussion

5 Evaluation of the findings based on the model structure 5. l Geographical distribution

5.2 Experimental methods used 5. 3 Type ofroad

5. 4 Work zone operation 5. 5 Work conducted

5. 6 _Road/work zone interactions 5. 7 Work zone area

5.8 Safety measures and devices 5.9 Additionalfactors

5.10 Individual

5.71] Road users Vworkers ' behaviour

5. [2 Road users '/workers attitudes and experiences 5.13 Reported conclusions

6 Summing up the evaluation of using the model in the reviewing process

Appendices 1 List of reviewed literature on which the paper is based 2 Overheads presented at the workshop

VTI Notat 25-1998 m Q Q Q Q M M M M M -k k k

1

Introduction

The level of safety possible to reach at road works depends on how well the often conflicting goals of protecting the workers and minimising the traffic disturbances can be mutually met. ' The challenge is to develop road work designs that are both safe for the workers,and

understood and accepted by the passing road users. Road user acceptance is assumed to lead to the behavioural changes intended and expected by the road work designers (managers, administrators). Thus, the risk level, or possible safety, at a road work is to a large extent determined by the road users behaviour and attitudes, which in turn are strongly influenced by the design of the road work and the workers actions as well as by the road user°s

experience from previous exposure to similar situations. Based on this view, the behavioural aspects in relation to road works was included, and have been studied in the ARROWS project.

2

Procedure

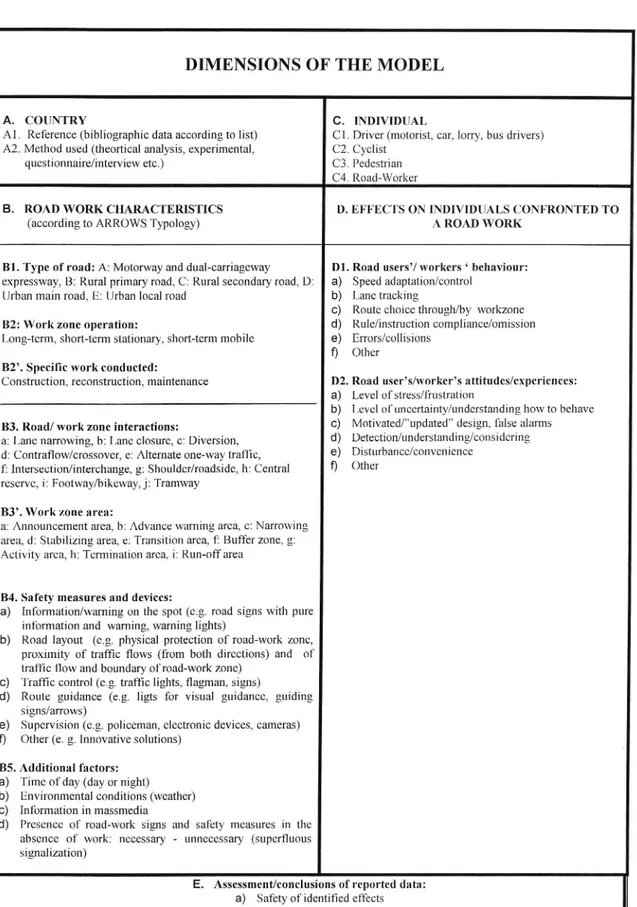

The accumulated knowledge of behavioural and attitudinal aspects related to road works was summarised and analysed. The method used was reviewing of available literature. Relevant reports were mainly collected via searching in computerised databases, and to a lesser extent via researcher networks and personal knowledge of the ARROWS partners. In order to

structure the reviewing and summarising task a model was developed by the partners in the

task (the VTI, the SWOV, the ZAG, and the BAST). The realisation of the model was the

form shown in Figure l. Another purpose with the model was to link the review of the road work zone behavioural studies to the Typology developed in ARROWS (ARROWS

Consortium, 1997).

3

Limitations

It is difficult to generalise and draw clear conclusions from the results presented in the behavioural studies reviewed and analysed. The reason is a number of limitations discovered in many of the studies, for example:

0 Terminology is used rather freely and inconsistently. Different authors use the same terms in different ways and with different meanings.

0 Numerous and often sparsely described factors and conditions are often combined in experimental designs that prevent conclusions to be drawn about specific measures and devices separately.

0 The prevailing conditions are generally, if mentioned at all, described insufflciently making it impossible to assess/judge eventual effect causalities in any detail.

0 The reports are mainly descriptive, and in very few cases statistical testing of differences and hypotheses seem to have been done.

DIMENSIONS OF THE MODEL

A. COUNTRY C. INDIVIDUAL

Al. Reference (bibliographic data according to list) C1. Driver (motorist, car, lorry, bus drivers) A2. Method used (theortical analysis, experimental, C2. Cyclist

questionnaire/interview etc.) C3. Pedestrian C4. Road-Worker

B. ROAD WORK CHARACTERISTICS D. EFFECTS ON INDIVIDUALS CONFRONTED TO (according to ARROWS Typology) A ROAD WORK

Bl. Type of road: A: Motorway and dual-carriageway D1. Road users°/ workers ° behaviour: expressway, B: Rural primary road, C: Rural secondary road, D: 3) Speed adaptation/control

Urban main road, E: Urban local road b) Lane tracking

C) Route choice through/by workzone BZ: Work zone operation: d) Rule/instruction compliance/omission Long-term, short-term stationary, short-term mobile e) Errors/collisions

f) Other BZ . Specific work conducted:

Construction, reconstruction, maintenance D2. Road usei',s/worker,s attitudes/experiences: a) Level of stress/frustration

b) Level of uncertainty/understanding how to behave C) Motivated/ updated design, false alarms

d) Detection/understanding/considering

e) Disturbance/convenience f) Other

B3. Road/ work zone interactions:

a: Lane narrowing, b: Lane closure, c: Diversion, d: Contraflow/crossover, e: Alternate one-way traffic, f: Intersection/interchange, g: Shoulder/roadside, h: Central reserve, i: Footway/bikeway, j: Tramway

B32 Work zone area:

a: Announcement area, b: Advance warning area, c: Narrowing area, d: Stabilizing area, e: Transition area, f: Buffer zone, g: Activity area, h: Termination area, i: Run-off area

B4. Safety measures and devices:

a) Information/warning on the spot (eg. road signs with pure information and warning, warning lights)

b) Road layout (eg. physical protection of road-work zone,

proximity of traffic flows (from both directions) and of traffic flow and boundary of road-work zone)

C) Traffic control (eg. traffic lights, flagman, signs)

d) Route guidance (e. g. ligts for visual guidance, guiding signs/arrows)

e) Supervision (eg. policeman, electronic devices, cameras) f) Other (6. g. Innovative solutions)

BS. Additional factors: a) Time ofday (day or night) b) Environmental conditions (weather) C) Information in massmedia

d) Presence of road-work signs and safety measures in the absence of work: necessary - unnecessary (superfluous signalization)

E. Assessment/conclusions of reported data: a) Safety of identified effects

b) Explanation ofeffects

Figure 1 Form (review sheet) used in the reviewing of road work zone behavioural studies

4

Selected results and discussion

The most consistent (and expected) finding in the reviewed studies is that drivers drive too fast at road works. Compared to signed speed limits, the maj ority of drivers approach and pass road works with much too high speeds. Speed levels of 10 to 20 km/h above signed limits are not unusual in the reviewed reports, and the recorded top value was 172 km/h at a 60 km/h road section! Generally, the drivers don°t adapt speed (decelerate) until just before an abrupt change in the road layout or conditions (like a crossover point), but then they brake extremely hard. Also, a vehicle°s speed in the activity area seems to be related to its initial speed.

Vehicles with higher initial speeds reduce their speed more than vehicles with lower initial speeds. In spite of the larger speed reduction, the fastest vehicles seem to pass the activity area with higher speeds compared to vehicles with lower initial speeds. Among those drivers not reducing their speeds at all, a great maj ority drive with a medium high initial speed.

A cause for real concern is that drivers believe that they take enough caution and slow down enough when passing road works, while experimental studies observing real behaviour clearly show that they do not behave as they claim. Even more problematic is that the drivers not behave as they apparently think they do.

When it comes to measures intended to reduce the speeds at road works, not only the

development and design are of importance. It is also necessary to consider in which phase of passing a road work drivers should be influenced, i.e. the location of a device should be carefully decided. From the results of the reviewed studies, devices used to make drivers slow down, i.e. speed limit signs, feedback VMS, lane narrowing devices, should preferably be positioned before the transition area.

Another question concerns the amount of devices that should be used when furnishing a road work zone. For instance, a lot of different devices could be positioned at the work site with the purpose to reduce speeds. But all these devices shall be detected and understood by the

drivers, and decisions and actions should be taken. The result can be information and mental

overloading of the drivers - especially inexperienced novices - leading to incidents and/or accidents even though the speed is reduced. Is it possible to make road work zones safer by limiting the number of devices and crossover points? A reasonable hypothesis may be, the more devices, the greater the risk that there will be devices missing, misplaced, out of order, misunderstood or not detected.

Standardisation of work site areas regarding traffic guidance, alignment, and width of

temporary lanes, as well as of individual signposts and guiding devices, is proposed by many authors, and assumed to strongly contribute to the solution of the safety problem at road works. This standpoint is also in line with the harmonisation task in ARROWS. Even so, the remark by Pomareda and Zacharias (1991) may be worth considering. They put forward some worry that a too uniform appearance of work sites may give the drivers a feeling of familiarity and false safety, which can make them to no longer possess an adequate sensitivity for

unexpected hazardous situations that may occur within a work zone.

5

Evaluation of the findings based on the model structure

How well the different categories in the used model were covered by the found and reviewed reports was investigated. It is obvious that the great maj ority of the studies deals with a limited number of the aspects in the model , while many categories are only sparsely or not at all considered (mentioned). Going through the results of the reviewing of behavioural studies in a quantitative way resulted in the following remarks.

5. 1 Geographical distribution

A majority ofthe reviewed studies is from the United States, which leads to several questions to discuss. Is it for instance possible to translate/transfer the results from US studies to

European conditions? Simply copying or modifying US solutions and suggestions should be carefully considered, not least because of differences between US and Eur0pean rules and habits (traffic, social). The methods can probably be copied to investigations on European ground, but the safety measures - for instance, different signs and closures - can be a problem. In many cases the safety measures used in US differ from those used in Europe. Great care should therefore be taken before for example a sign that has been clearly seen, understood and shown to reduce drivers speed inside work zones in the United States is included in European guidelines. The lack of studies done in Europe regarding behaviour at road work zones, also leads to the question if it is possible - at this stage - to know or predict whether this or that guideline will lead to a correct behaviour at European road works. Perhaps we should try some ofthe most promising methods from the US studies here in Europe, before we draw any

conclusions in this matter?

5.2 Experimental methods used

Field studies (different kinds) measuring real behaviour are clearly the most commonly used method in the reviewed reports, followed by interviews and questionnaires. Studies containing both field tests and interviews and/or questionnaires are however unusual. This fact is

interesting to note as the latter case obviously is to prefer to enable getting the whole picture of a problem, i.e. to besides observing behaviour also enable answering questions like whether the road users did see and understand the signing and guiding or not, how they experienced the road work, why they behaved as they did etc.

5.3 Type of road

The reviewed studies almost exclusively investigate road user behaviour at road works on motorways and dual-carriageway expressways. Hardly any of the studies deals with road user behaviour at road works conducted on rural secondary roads and urban local roads. The question is - why? Is the lesser research interest based on an estimated risk level for workers and road users, degree of obstruction of the traffic, size and type of work, or The noted unbalance demands special attention also because the proportion of non-motorway type roads is greater in Europe than in the US. If we want to fully understand the road users behaviour at road works in all types of environments, it is of the greatest importance that investigations of road works on rural secondary roads and urban local roads are done in the near future.

5.4 Work zone operation

ln about 50% of the reviewed studies of road user behaviour at road works, the work zone

operation undertaken was not specified. When the operation was described, it was in most cases classified as a long-term work zone Operation, while short-term mobile operations were very seldom investigated.

5.5 Work conducted

The review of road work zone behavioural studies shows that the specific work conducted during the studies is usually construction or maintenance, while reconstruction projects are unusual. lt must however be pointed out that in a large number of the reports the type of work conducted is not mentioned at all.

5. 6 Road/work zone interactions

When it comes to road/work zone interactions the interaction appearing most frequently in the studies is lane closure followed by contraflow/crossover. In a large number of studies the type of road/work zone interaction is not specified, and most ofthe alternatives in this category have not a single time been mentioned in the reviewed studies.

5. 7 Work zone area

The road user behaviour has in most studies been observed and recorded in the advance warning area, the narrowing area, the transition area, or the activity area, the pr0portions of these locations being about the same. The alternatives in this category as well as those under the heading road/work zone interactions (see above) have been very difficult to use when reviewing the studies. In many cases the alternatives used in our model, which are in accordance with the typology developed in ARROWS Task 1.1, have not been mentioned. Also, in many other cases a different terminology, not using a division at our level of detail, have been applied. This finding leads of course to the question if the design of the model is improper, or if studies concerning road users behaviour are insufficiently thorough when it comes to more technical descriptions of the road work zone.

5.8 Safety measures and devices

The safety measures and devices actually examined in the studies were usually information and/or warnings on the spot (in the form of road signs), and route guidance devices (lights for visual guidance, guiding signs/arrows). When reviewing the reports, specification of the safety measures and devices according to the model caused some problems. On one hand, it was difficult to decide which safety measures and devices should be mentioned in the review when only one particular device was being tested, but also a lot of other safety measures and devices were in place during the study. On the other hand, some studies didn°t mention other devices than the item(s) under study even though other devices obviously must have been in place, because otherwise the test site could not have been a road work zone! Also, experimental designs where one device after another is added incrementally are not uncommon, making it impossible to draw conclusions about the effects of separate measures. Thus, in many cases it is difficult to estimate how much other devices than those really investigated influenced the results reported. This aspect was not discussed by the authors.

5.9 Additional factors

The additional factor most frequently described in the reviewed studies was time of day, followed by the prevailing environmental conditions. Also when it comes to additional factors 1t must be pointed out that they were not mentioned at all in a large pr0portion of the reviewed studies.

5. 10

Individual

When it comes to the individuals studied, it is clear that almost all the reviewed studies have

investigated drivers (especially car and truck drivers°) behaviour in road work zones. Such investigations are of course ofgreat importance and value. At the same time, it is a serious problem that the behaviour of cyclists, pedestrians and road-workers has hardly been paid any attention at all. The reason for the unbalance is probably that the road works have been studied mainly on motorways and dual-carriageway expressways. Even so, if we are aiming at safer conditions for workers and road user in all types of work zones and environments, it is obvious that behavioural research covering all road user groups have to be done.

5. 11 Road users '/workers' behaviour

The effect of different safety measures and road work designs on road user behaviour is predominantly recorded and observed in terms of speed (adaptation and control). The second most common variables are lane tracking and lane change. The other alternatives of

behavioural effect variables included in the model (eg. route choice, obedience of rules and instructions, mistakes/errors and collisions) are rarely recorded or observed. The question necessary to raise is then if behavioural variables other than speed and lateral position are improper, or if research regarding these other variables have simply not been conducted (have bee neglected). Our Opinion is that the latter case is the truth.

5. 12 Road users'/workers' attitudes and experiences

Road users attitudes and experiences are more seldom examined than their actual behaviour. And when they are, the road users are usually asked to report whether or not they detected, understood, and considered the messages conveyed by signs and other devices within the

road work zone. Aspects like experienced stress, frustration, inconvenience, uncertainty and

false designs are very seldom dealt with, as is how motivated the road users find the road work design.

ln very few studies data about both the actual behaviour of the road users and their attitudes and experiences are collected. lf this is due to a lacking interest of road users subjective view (attitudes, opinions and experiences) from passing road works or something else is open for

discussion. But it is our recommendation that, whenever possible, future studies should

contain measuring the effects on road users actual behaviour as well as on their attitudes and experiences. The result would be a better understanding ofwhy the road users behaved like they did in a specific set up. It is incorrect to say that a new device is a failure just because you could not find any change in the road users behaviour. For instance, the lack of change in behaviour may very well be due to the fact that the road users did not see the device. Without asking the road users, it is hard to draw any safe conclusions about why the behaviour was not changed. Also, it is difficult to draw any safe conclusions about the behavioural effects of a

specific safety measure if you just ask the road users about their behaviour, and not observe their actual behaviour in order to see if they behave like they say.

5. 13 Reported conclusions

The main suggestions by the authors of the reviewed reports were changes in equipment and regulations.

6

Summing up the evaluation of using the model in the

reviewing process

The model worked well concerning some aspects, but not others. Too often just a few

alternatives under the respective heading have been investigated or mentioned in the reviewed studies. This leads to the following questions regarding what structure ( model ) to adopt in assessing effects of different road work designs in different environments and conditions: O Was the model used in assessing the reviewed reports too detailed for behavioural

studies?

0 Should the relatively large number of aspects and variables included in the model - but not dealt with in the studies - be interpreted as not important, meaning that a more rough outline (division between and within categories) of assessing structure will do?

0 Dr the other way around; does the lack of knowledge concerning a relatively large proportion of aspects show that research in these areas has to be done to reach a higher level of safety at road works as a whole?

Bilaga 1 Sid 1 (4)

List of reviewed literature on which the paper is based

Ahmed, S.A. (1991). Evaluation of retroreflective sheetings for use on traffic control devices at construction work zones. Final report. School of Civil Engineering, Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma Department of Transportation, Stillwater, OK, 118 pp.

ARROWS Consortium (1997). Road Work Zone Typology, Safety Measures, Standards and Practices. Deliverable 1, ARROWS Project, within the EC:s Fourth Framework, National Technical University of Athens (NTUA).

Aulbach, J. (1992). Lichttechnische Gestaltung von Arbeitsstellen. Technische Hochschule, Darmstadt, Forschungsbericht FE-Nr. 03.213 G 89 F, (German).

Becker, H. & Schmuck, A. (1983). Verkehrsablauf an Autobahnbaustellen. Lehrstuhl für

Verkehrsplanung und Strassenwesen, Hochschule der Bundeswehr München, Heft 14, pp. 7-167, (German).

Benekohal, R.F. & Kastel, L.M. (1991). Evaluation of flagger training session on speed

control in rural interstate construction zones.Transportation Research Record, nr 1304,

pp. 270-291.

Benekohal, R.F., Resende, P.T.V. & Zhao, W. (1993). Temporal speed reduction effects of drone radar in work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 1409, pp. 32-41.

Benekohal, R.F., Shim, E. & Resende, P.T. (1995). Truck drivers' concerns in work zones:

Travel characteristics and accident experiences. Transportation Research Record, nr 1509, pp. 55-64.

Benekohal, R.F. & Wang, L. (1994). Relationship between initial speed and speed inside a highway work zone. Transportation Research Record, nr 1442, pp. 41-48.

Benekohal, R.F., Wang, L., Orloski, R. & Kastel, EM. (1992). Speed-reduction patterns of vehicles in a highway construction zone. Transportation Research Record, nr 1352, pp 35-45.

Better Roads. (1991). Which signs really cut work-zone accidents? Better Roads, 61(3), P. O.

Box 558, Park Ridge, IL, 60068, USA, pp. 22-23.

Blackmon, R.B., & Gramopadhye, A.K. (1995). Improving construction safety by providing positive feedback on backup alarms. Journal of Construction Engineering and

Management. 121(2), pp. 166-171.

Bowman, B.L., Fruin, IJ., Zegeer, C.V. (1989). Pedestrian facilities in work zones. In:

Handbook on planning, design, and maintenance of pedestrian facilities. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Goodell-Grivas Inc., Washington DC, pp. 176-190.

Bryden, J.E. (1990). Crash Tests of Work Zone Traffic Control Devices. Traffic control devices for highways, work zones and railroad grade crossings. Transportation Research Record, nr 1254, pp. 26-35.

Chadda, H.S., Brisbin, G.H. (1983). The obstacle course: Pedestrians in highway work zones.

Transportation Research Record, nr 904, pp. 50-57.

Cooper, M.D., Phillips, R.A., Robertson, I.T. & Duff, A.R. (1993). Improving safety on construction sites by psychologically based techniques: alternative approaches to the measurement of safety behaviour. European Review of Applied Psychology, Vol. 43, No.

1, pp. 33-40.

Dudek, C.L., Richards, S.H. & Buffington, J.L. (1986). Some effects of traffic control on four-lane divided highways. Transportation Research Record, nr 1086, pp. 20-30.

Dudek, C.L., Ullman, G.L. (1989). Traffic control for short-duration maintenance Operations on four-lane divided highways. Transportation Research Record, nr 1230, pp. 12-19.

Bilaga 1 Sid 2 (4)

Freedman, M., Teed, N. & Migletz, J. (1994). Effect of radar drone operation on speeds at high crash risk locations. Transportation Research Record, nr 1464, pp. 69-80.

Garber, N.J. & Patel, S.T. (1995). Control of vehicle speeds in temporary traffic control zones (work zones) using changeable message signs with radar. Transportation Research

Record, nr 1509, pp.73-81.

Gardner D.J. & Rockwell T.H. (1983). Two views of motorist behavior in rural freeway construction and maintenance zones: the driver and the state highway patrolman. Human Factors, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 415-424.

Godthelp, H. & Riemersma, J.B.J. (1982a). Perception of delineation devices in road work zones during nighttime. SAE Technical paper 82 04 13, Warrendale, PA, 9 pp.

Godthelp, H. & Riemersma, J.B.J. (1982b). Vehicle guidance in road-work zones. Ergonomics, Vol. 25, No. 10, pp. 909-916.

Hanscom, F.R. (1982). Effectiveness of changeable message signing at freeway construction site lane closures.Transportation Research Record, nr 844, pp. 35-41.

Hanscom, F. (1991). Closed track testing of maintenance work zone safety devices. In:

Proceedings ofthe Conference Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) and Traffic Safety on two Continents, September 18-20 1990, Gothenburg, Sweden, VTI Rapport nr 372A:5, Swedish Naitonal Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, pp. 125

-13 9.

Hanscom, F., Graham, J. & Stout, D. (1994). Highway evaluation of maintenance work zone

safety devices. Proceedings of the Conference Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) and Traffic Safety on two Continents, September 22-24 1993, Hague, the Netherlands, VTI Konferens nr 1A. Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, pp. 143-157.

Harkey, D.L., Mera, R. & Byington, S.R. (1993). Effect of nonpermanent pavement markings on driver performance. Transportation Research Record, nr 1409, pp, 52-61.

Hess, M. (1993). Verkehrssicherheit im Bereich von Autobahnbaustellen. Dissertation (Mitteilung Nr. 35). Lehrstuhl und Institut für Strassenwesen, Erd- en Tunnelbau, Rheinischen-Westfalischen Technischen Hochschule (RWTH), Aachen, 165 + 44 pp, (German).

Honrath, J. & Trauden, A. (1988). Untersuchung der Auswirkungen verschiedener Vorwarneinrichtungen auf das Fahrverhalten der Verkehrsteilnehner vor fahrbaren Absperrtafeln auf denUberholfahrstreifen (Study of effects of different advance warning devices on driving behavior while approaching mobile lane closure signs on passing lane). Strassenverkehrstechnik. Vol. 32, Heft 3, pp. 103-109, (German).

Huchingson, D.R., Whaley, J.R. & Huddleston, N.D. (1984). Delay messages and delay tolerance at Houston work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 957, pp. 19-21. Huddleston, N.D., Richards, S.H. & Dudek, C.L. (1982). Driver understanding of work-zone

flagger signals. Transportation Research Record, nr 864, pp. 1-4.

Hunt, J.G. & Yousif, S.Y. (1990). Merging behaviour at roadworks. Traffic Management and Road Safety. Proceedings of Seminar G, 18th PTRC EurOpean Transport and Planning Summer Annual Meeting, University of Sussex, September 10-14. Vol. P334, pp. 55-68. Hunt, J.G. & Yousif, S.Y. (1994). Traffic capacity at motorway roadworks - effects of layout, incidents and driver behaviour. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Highway Capacity, Vol. 1, pp. 295-314.

Kockelke, W. (1990). Analysis of driver behaviour and accidents at work sites on german motorways. Proceedings ofthe Conference Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) and Traffic Safety on two Continents, September 27-29 1989, Gothenburg, Sweden, VTI

Bilaga 1 Sid 3 (4)

Rapport nr 351A, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, pp. 11-20.

Kuemmel, D.A. (1992). Maximizing legibility of traffic signs in construction work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 1352, pp. 25-34.

Lenz, K.H. & Steinhoff, H. (1972). Beeinflussung des Fahrverhaltens auf Behelfsfahrstreifen der BAE-Baustellen (Influencing driver behaviour on auxiliary lanes at motorway construction sites). Strassenverkehrstechnik, Vol 16, Heft 3, pp. 82-86, (German).

Lewis, R.M. (1989). Work-zone Traffic Concepts and Terminology. Work-zone traffic control and tests of delineation material. Transportation Research Record 1230, Washington DC, pp. 1-11.

McCoy, P.T., Bonneson, J .A. & Kollbaum, J.A. (1995). Speed reduction effects of speed

monitoring displays with radar in work zones on interstate highways. Transportation Research Record, nr 1509, pp. 65-72.

McCoy, P.T & Peterson, D.J. (1988). Safety effects of two-lane two-way segment length through work zones on normally four-lane divided highways. Transportation Research Record, nr 1163, pp. 15-21.

Mousa, R.M., Rouphail, N.M. & Azadivar, F. (1990). Integrating MicroscOpic Simulation and Optimization: Application to Freeway Work Zone Traffic Control. Traffic control devices for highways, work zones and railroad grade crossings. Transportation Research Record 1254, pp. 14-25.

Nadler, F., Hanko, W. & Schrefel, J. (1988). Verkehrssicherheit im Bereich von Baustellen

auf Autobahnen. Bundesministerium für Wirtschaftliche Angelegenheiten, Wien, Strassenforschungsvorhaben Nr. 659, Heft 372, (German).

National Transportation Safety Board. (1991). Highway accident report : multiple vehicle collision and fire in a work zone on interstate highway 79 near Sutton, West Virginia, July 26. National Transportation Safety Board NTSB, Washington, DC., p. 47.

Noel, E.C., Sabra, Z.A. & Dudek, C.L. (1989). Work zone traffic management synthesis: Use of rumble strips in work zones. Daniel Consultants Inc, Dudek & Assoc, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Washington DC, 51 pp.

Nygaard, B. (1982). Försök med körfaltsförändringstavla och olika vägmärken. (Tests with a sign indicating lane change manoeuvre and different road signs). VTIMeddelande nr 280, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, 23 pp

Ogden, M.A. & Mounce, IM. (1991). Misunderstood applications of urban work zone traffic control. Transportation Research Record, nr 1304, pp. 245-251.

Ogden, M.A., Womack, K.N. & Mounce, J .M. (1990). Motorist comprehension of signing applied in urban arterial work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 1281, pp. 127-13 5.

Opiela, K.S. & Knoblauch, R.L. (1990). Work zone traffic control delineation for

channelization. Final report. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Center for Applied Research Inc, Washington DC, 102 pp.

Pain, R.F. & Hanscom, F.N. (1989). Waming lights on service vehicles in work zones.

Proceedings of the Conference Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) and Traffic Safety on two Continents, September 27-29 1989, Gothenburg, Sweden, VTI Rapport nr 351A, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, pp. 57-69. Paniati, J.F . (1989). Redesign and evaluation of selected work zone sign symbols.

Transportation Research Record, nr 1213, pp. 47-55.

Pant, P.D., Huang, X.H. & Krishnamurthy, S.A. (1992). Steady-burn lights in highway work zones: Further results of study in Ohio. Transportation Research Record, nr 1352, pp. 60-66.

Bilaga 1 Sid 4 (4)

Pant, P.D. & Park, Y. (1992). Effectiveness of steady-burn lights for traffic control in tangent sections of highway work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 1352, pp. 56-59. Parker, M.T. (1996). The effect of heavy goodsvehicles and following behaviour on capacity

at motorway roadwork sites. Traffic engineering and control. Vol. 37, No. 9, pp. 524-531. Pettersson, H-E. (1984). Utmärkning av rörliga vägarbeten: En effektstudie (Warning devices

for moving road work zones: An effect study). VTIRapport 273, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Linköping, 42 pp + appendix.

Pigman, J.G. & Agent, K.R. (1988). Evaluation of I-75 lane closures. Transportation Research

Record, nr 1163, pp. 22-30.

Pomareda, F. & Zacharias, U. (1991). Verkehrssicherheit und Verkehrsablauf im Bereich von Baustellen auf Betriebsstrecken der BAB. SNV mbH, Berlin, Forschungsvorhaben, Bundesministers für Verkehr, Förderkennzeichen FB 03.214 R 89 F, (German).

Richards, S.H. & Dudek, C.L. (1986). Implementation of work-zone speed control measures. Transportation Research Record, nr 1086, pp. 36-42.

Rouphail, N.M., Yang, Z.S. & Fazio, J. (1988). Comparative study of short- and long-term urban freeway work zones. Transportation Research Record, nr 1163, pp. 4-14.

Schuurman, H. (1991). Bottlenecks on freeways: traffic operational aspects of road

maintenance. In: Verkeerskundige werkdagen 1991, CROW publikatie 56 ii, 1991/05, pp. 557-568.

Shepard, F.D. (1989). Improving Work-Zone Delineation on Limited Access Highways. Final Report (No: fhwa/va-89/ 16). Virginia Department of Transportation, 47 pp.

Shepard, F.D. (1990). Improving Work Zone Delineation on Limited Access Highways. Traffic control devices for highways, work zones and railroad grade crossings. Transportation Research Record 1254, pp. 36-43.

Summala, H. & Pihlman, M. (1989). Trailer-truck drivers in work zones: Effects of a focussed campaign. Helsingin Yliopisto. Liikennetut-kimusyksikkö. Tutkimuksia 1721989.

Helsingfors, 13 pp.

Ullman, G.L. (1993). US. 75 North Central Expressway reconstruction: Lemmon/Oak Lawn/Peak screen line automobile user panel. Interim report. Texas Transportation

Institute, Texas A & M University, Research report 1940-6, College Station, TX, 21 pp. +

appendix.

Webb, S.A. & Coe, G.A. (1992). The Standards of Signing at Roadworks on Trunk and Principal Roads. Report No cr 306, TRL, Crowthorne, Berkshire, 41 pp.

Weinspach, K. (1988). Verkehrssicherheit und Verkehrsablauf im Bereich von Baustellen auf Betriebsstrecken der Bundesautobahnen. Strasse und Autobahn, Vol. 39, Heft 7, pp. 257-265.

Vercruyssen, M., Hancock, P.A., Williams, G., Olofinboba, O., Nookala, M. & Foderberg, D.

(1995). Lighted guidance devices : environmental modulation of drivers' perception of vehicle speed through work zones. Proceedings of the Second ITS World Congress, 9-11

November 1995, Yokohama, Japan, Vol. 4, pp. 1689-1694.

Bilaga 2 Sid 1 (21)

Road Work Zone

Behavioural Studies

Lena Nilsson

Swedish National Road and

Transport Research Institute (VTI)

Bilaga 2 Sid 2 (21)

Background

ARROWS Task 2.1

Assessment of available knowledge

>I< road user behaviour

>I< road users opinions and

experience

>I< safety implications

Partners: VTI, SWOV, ZAG, BAST

Bilaga 2 Sid 3 (21)

Method

Literature study

Structured review

Development of assessment model

linked to ARROWS typology and

classiñeation

Bilaga 2 Sid 4 (21)

Results

Drivers pass road works too fast!!

10 - 30 km/h above limit

decelerate late

brake extremely hard

Drivers think they take enough

caution and slow down enough!!

Location of speed reducing device

important - before transition area

Complicated road works with

numerous devices => mental

overloading => incidents/accidents

in spite of reduced speed

Bilaga 2 Sid 5 (21)

Limitations

Inconsistent terminology

Insufficient descriptions of

experimental and environmental

conditions

Incomplete experimental designs

preventing conclusions to be drawn

about different safety measures

separater

Mainly descriptive studies, and no

statistical hypothesis and testing of

differences

Bilaga 2 Sid 6 (21)

Discussion

Geographical distribution

Majority of studies from US

Transfer of results to European

conditions possible?

>1< methods - yes

* effects of safety measures ???

>r< predictability of correct

behaviour from European

guidelines ???

Bilaga 2 Sid 7 (21)

Discussion

Experimental methen?

1)

Field studies

2)

Questionnaims/interviews

Combined studies mmmnmon but

recommended for future studies to get

the Whole picture

Bilaga 2 Sid 8 (21)

Discussion

Type ofroad

Almost all studies on

motorways

dual-carriageway expressways

Hardly any studies on

rural secondary roads

urban local roads

Interest in understanding behaviour

at road works in all environments???

Larger proportion of motorways in

US than in Europe => ???

Bilaga 2 Sid 9 (21)

Discussion

Work zone operation

Not speeiñed in 50% of the studies

When specified

* mostly long-term operations

* very seldom short-term mobile

operations

Bilaga 2 Sid 10 (21)

Discussion

Work conducted

Usually construction or maintenance

Rarer reconstruction

Bilaga 2 Sid 1] (21)

Discussion

Road - work zone interactions

Most of the alternatives in the

model (ARROWS typology) are

not mentioned in any study

1)

Lane closure

2)

ContraHOW/crossover

Bilaga 2 Sid 12 (21)

Discussion

Work zone area

Research about equally distributed between

advance warning area

narrowing area

transition area

activity area

Several alternatives in the model

(ARROWS typology) have not been

studied (mentioned)

Usually a less detailed division of this

category than in the model

(ARROWS typology)???

Bilaga 2 Sid 13 (21)

Discussion

Safety measures and devices

Information and warnings on the spot

Route guidance (lights, signs and arrows)

Difñculties:

Description of many devices

-which were really studied???

Insufñcient description of devices

in place - influence of other on

reported results???

Devices added incrementally

Bilaga 2 Sid 14 (21)

Discussion

Additionalfactors

Not specified at all

in a large proportion of studies

1)

Time of day

2)

Environmental conditions

Bilaga 2 Sid 15 (21)

Discussion

Individual

Drivers (car and truck)

Pedestrians, eyelists and workers

hardly paid any attention at all

(in reviewed studies)

Interest in safer conditions for

workers and all road user categories

in all types of work zones and

environments???

Bilaga 2 Sid 16 (21)

Discussion

Road users i/workers behaviour

1)

Speed (adaptation and control)

2)

Lane tracking/lane change

Other variables like

obedience of rules and instructions

mistakes and errors

route choice

distance control

accidents

are rarely recorded or observed

Why people behave as they do are not

reflected by these variables!!

Bilaga 2 Sid 17 (21)

Discussion

Road users /w0rkers attitudes und

experiences

Much more seldom examined than

real behaviour

Pe0ple usually asked whether or not they

detected

understood

considered

Aspects very seldom dealt With are experienced

stress

frustration

inconvenience

uncertainty

false (not motivated) designs

Bilaga 2 Sid 18 (21)

Discussion

Reported conclusions

Suggestions by authors mainly

changes in equipment

changes in regulations

Measures direeted directly to read

users and workers???

Bilaga 2 Sid 19 (21)

??? for thefuture

Usability of US results on European

ground???

The types of roads studied most frequently

(motorways, expressways) influence most of

the other factors, eg.

type of operation

road/work zone interactions

work zone areas used

safety measures and devices

road user groups

How broad is our interest in covering

all environments???

Bilaga 2 Sid 20 (21)

???for thefuture (cont.)

What variables should be measured to

reflect safety related behaviour in an

optimal way???

How to link behaviour and attitudes

to incidents and accidents, to better

understand the development of

accident prone situations?

Bilaga 2 Sid 21 (21)