Two-year Political Science MA program in Global Politics and Societal Change Dept. of Global Political Studies

Course: Political Science Master's thesis ST631L (30 credits) Spring/2020

Supervisor: Mikael Spång

Broken Solidarity

The Refugees Welcome Movement in Sweden 2015-2020

Fanny Mäkelä

A warm thank you to Maya, Steve, Mesere, Andreas, Lasse, Ewa,

Antoinette, Emma, Petruska, Alexandra, Tobias, Ulrika, Gemila, Kamal,

Kajsa, Cecilia, Ehab, Sara, Anna, and China.

For your time and generosity,

Abstract

This qualitative inquiry explores and describes the Refugees Welcome movement in Sweden from 2015 to 2020 by exploring how people became volunteers, their motivation and experience while at the same time describing events, sceneries, and context with the help of their stories. The empirical material consists of 25 interviews with 20 interviewees, the theoretical perspectives come from the fields of volunteering, civil society, and social movements. A thematic analysis is the method used and the results are presented as part 1 Refugees Welcome to Malmö during the refugee crisis in the fall of 2015, and part 2 with the post-2015 Refugees Welcome initiatives separated by the establishment of checkpoints. The volunteers paint a picture of civil society handling an international issue in a globalized world, and what happens when that globalized world closes. The conclusion is that when the states of Europe introduced checkpoints it drastically changed the context of the opportunities to help refugees, cutting off networks of solidarity from the Mediterranean Sea to Malmö Central Station, and when the local authorities took over the responsibility for the refugee reception they cut off civil society and killing the engagement of the volunteers. Word count: 21337

Keywords: Qualitative Inquiry, Volunteering, Civil Society, Social Movements, Refugees, Refugees Welcome

C

ONTENT

1 Introduction 2 1.1Research problem 2 1.2Purpose 3 1.3Research questions 3 1.4Delimitations 4 1.5Chapter outline 4 2 Theory 52.1The field of volunteering 5 2.2Civil society 7

2.3Social movements 8

2.4Refugees and civil society in Europe 10 3 A qualitative inquiry 11

3.1The art of interviewing 12 3.2A thematic analysis 14 3.3Data collection 17

3.3.1 A presentation of the interviewees 18 4 Analysis 21

4.1Preface: what we have sworn to defend 21

4.2Part 1: Refugees Welcome to Malmö in the fall of 2015 22 4.2.1 An opportunity to do good 22

4.2.2 Building bridges by cooperation 26

4.2.3 Prestige, critique and conflict on all fronts 28 4.2.4 Civil society vs. the authorities 31

4.2.5 The nice memories shines the brightest 33 4.3Checkpoints: ‘for the international right to asylum’ 36 4.4Part 2. Refugees Welcome in post-2015 Sweden 38

4.4.1 They are not cute puppies anymore 38 5 Conclusion 47

6 Bibliography 51 7 Appendix 54

2

1 I

NTRODUCTION

Looking at the refugee reception (or absence of reception) from 2015-2020 systems within states, and cooperation between states failed to work successfully to receive and protect refugees. States chose to handle this global issue the old way of sovereignty and territoriality á la Peace of Westphalia, while civil society stepped in taking on the duties and responsibilities in the absence of the states. With the help of social media, civil society created networks locally, nationally, and transnationally enabling moment to moment aid where ‘numbers’ and ‘needs’ shifted hour to hour in a time of crisis1 and I call this phenomenon the ‘Refugees Welcome movement’.

1.1 R

ESEARCH PROBLEMAgainst the important role that civil society played in 2015 it is worth studying how this movement came about and worked and look at what motivated people to become volunteers and their experiences. It is also worth studying how come the Refugees Welcome movement ended before it had barely begun, why people are not motivated to volunteer in what I have named the ‘post-2015’ context of a closed Europe. This refugee crisis is a new chapter in the European history of civil society networking across borders helping and protecting refugees, but compared to the older chapters like the first and second world war, with the globalization of communication social media enables anyone anywhere with a smart phone or computer to get in touch with each other in real-time. And so, it is interesting to look at civil society’s refugee reception and protection with these new possibilities and challenges and doing so over time. European states chose to handle this global event by closing the borders, looking at how this affected this globalized civil society’s abilities for refugee reception and protection is valuable. This study is relevant to the fields of volunteering, civil society, social movements, global politics, and societal change. This knowledge in turn can inform states on how to facilitate action and

1 In this study I will use the refugee crisis and not the ‘so called’ refugee crisis for two reasons 1) because flyktingkrisen

[the refugee crisis] is the actual name of the event in Sweden 2) to acknowledge that this was an actual crisis for the refugees, and it was about life and dead. I am not ignorant of the linguistic debate and the politization of the wording, I choose the perspective of the refugees, and for them this was not a ‘so called’ crisis.

3 cooperate with civil society in cases of crisis, civil society actors can find inspiration and education in their own work from previous experience, which together may create a better refugee reception and protection in the future.

1.2 P

URPOSEThe purpose of this qualitative inquiry is to explore and describe the Refugees Welcome movement, when hundreds of thousands of people got together all over Europe as a civil society in 2015 for the specific cause of aiding, receiving and protecting refugees, and to explore the effects of the checkpoints creating the post-2015 context. There will be stories and descriptions from other parts of Europe and small city initiatives across Sweden which I will include, but the main initiatives of this research are: Refugees Welcome to Malmö that was local and originated the same day as ‘the crisis’ started in Sweden the fall of 2015; the four post-2015 initiatives Refugees Welcome Sweden that is an attempt to organize all the small refugees welcome city names into a national organization for cooperation, co-ordination and a united platform; Refugees Welcome Borås/Sjuhärad, Refugees Welcome Malmö and Refugees Welcome Housing Sweden that works with matching Swedish landlords with refugees to be roommates. Sine the Refugees Welcome movement in Sweden has been rising and disappearing, ever changing its volunteers and civil society functions it is important to study over time, in this case between 2015-2020.

1.3 R

ESEARCH QUESTIONSIn investigating differences between 2015 and post-2015, I argue that the change of context is important to understand. Therefore, I pose questions for both the 2015 and the post-2015 context, but the overarching research question is: how can we understand the quick rise and demise of the Refugees Welcome movement in Sweden? Operationalized with the questions: why did hundreds of thousands of volunteers go together as a civil society receiving and protecting refugees in 2015? How did they do it? What are the motivations, experiences, and reflections of the volunteers? The questions regarding post-2015 is how does the movement look like today

4 regarding civil society functions? What does the engagement look like? What are the volunteers motivations and experiences? And what are their reflections of the post-2015 context?

1.4 D

ELIMITATIONSThis study cannot speak for volunteers or initiatives in Sweden, which is not a part of the inquiry, and hence should not be used to generalize. There literature on volunteering, civil society, and social movements are vast, but due to prioritization there will not be a classic literature review, instead only the selected theoretical frameworks which will be used are presented in favour of the analysis.

1.5 C

HAPTER OUTLINEIn chapter 2 there will be theoretical frameworks on volunteering, civil society, and social movements, in chapter 3 I will present my qualitative design with method of collecting data and thematic analysis. Chapter 4 contains the analysis, part 1 presenting the themes the fall of 2015 Refugees Welcome to Malmö, and part 2 the post-2015 Refugees Welcome initiatives. The study ends with the conclusion as chapter 5, bibliography chapter 6 and appendix chapter 7.

5

2 T

HEORY

This chapter does not contain a traditional literature review due to my decision to prioritize space for the analysis. Reading through the literature in the academic fields of volunteering, civil society, and social movements I have made some selections for further reading in respective field, and the chapter ends with some suggestions or literature that is interesting in direct relation to this study.

2.1 T

HE FIELD OF VOLUNTEERINGThe Refugees Welcome movement is a network of non-governmental organizations, associations and autonomous initiatives that are initiated and organized by volunteers, so you can say that the volunteers are the movement. That is why I have turned to the literature on volunteering.

To get a good overview of this field read Volunteering and Society in the 21st Century written by

Rochester et al. (2012). When trying to define volunteering2. and a volunteer3 you find numerous

examples of typologies, models, checklists, and principles in the literature. The definition that I have decided upon is made by Wilson, ”volunteering is any activity in which time is given freely

2Some of them are made by Smith (2000), Dingle (2001), Rochester and Hutchison (2002), Bills (1993), Hankinson

and Rochester (2005), Cnaan et al. (1996) and Rochester et al. (2012) and Kearney (2001).

3There is the episodic volunteers that includes the employer-supported volunteers, older volunteers, transitional

volunteers, the professional volunteer, unemployed volunteers, (Macduff, 2005), transnational volunteers, virtual volunteer (Evans & Saxton, 2005, Cravens, 2006), ‘classic’ and ‘new’ (Hustdinx, 2001) and the disaster volunteers (Sharon, 2004) among others. I find that many definitions have one thing in common, a basic distinction between the ‘long-term’ and the ‘short-term’ volunteer (Danson, 2003). Unfortunately, there is not within the scope of this study to explore the typology of the disaster volunteer, the phenomenon when very large numbers of spontaneous and

unaffiliated volunteers comes together in response or tragic events or major disasters of an extraordinary kind (see Sharon, 2004).

6 to benefit another person, group or cause” (2000, p. 215), hence focus lies on the act itself without considering the motives to volunteer or whether or not it benefits the volunteer in question. Therefore, I find it logical to define a volunteer as a person that do this activity and therefore it is this understanding that is used in this study.

There are three paradigms on volunteering which may overlap that gives us a broad perspective on volunteering, these are the dominant or ‘non-profit’ paradigm, volunteering as serious leisure (Stebbins and Graham, 2004), and the civil society or activist paradigm (Lyons et al 1998). In the dominant or ‘non-profit’ paradigm the opportunity for volunteering is provided by large organizations with paid staff and a formal structure, usually charities where volunteers are ‘un paid help’ with pre-defined roles (Rochester et al. (2012, p. 11-14). The motivation to volunteer is fundamentally altruistic, and one’s time is a ‘gift’ providing support or care to people in need, such as children, elderly, people with disabilities or people living in poverty (ibid.). Rochester et al. discuss two ‘new’ perspectives, namely volunteering as serious leisure and the civil society or activist paradigm. With the perspective on volunteering as serious leisure the motivation is presumed to be an enthusiasm for a specific activity and acquiring the skills and knowledge to exercise it (ibid.). This is a way to spend some free time to express oneself in the fields of art, culture or sports and perhaps substitute for a ‘mundane’ everyday life (ibid.). The civil society or activist paradigm is characterized as ‘horizontal’ and the motivation is mutual aid and self-help working together to address common problems and meet shared needs, “their activities extend beyond social welfare to other areas of public policy such as transport, town planning and the environment (ibid. p. 12 ). The organizational context is ‘grass-roots associations’ where “the role to be played by the member activist in this kind of organisation ‘cannot be defined in advance’ but ‘will be developed over time in the light of experience, personal growth and reflection’” (ibid.).

When it comes to the question of what motivates people to volunteer there are an immense number of studies looking for the golden answer, if we know what motivates people we can design the recruitment process to increase the number of people who volunteer, attract the exact volunteer that we desire and make them stay. Here we also find an amount of lists, typologies, models and principles and needs as well, and you can divide the literature into basic psychological needs that we all share, or that there are as many motivations as there are volunteers.

The focus in this field has been defining ‘what is’ and ‘motivation’ without much interest in actual volunteers, and the two main methods are surveys and desk work trying to understand complex human beings in a complex social setting. I believe that there is a need to look beyond the dominant paradigm of quantitative methodology which gives us ‘broad and shallow’

7 knowledge, to an epistemological recognition that ‘few and deep’ can give us valuable knowledge and understanding using qualitative methodology. Three things that is shining with its absence is how people become volunteers, experiences of being a volunteer, and context, I will cover these white spots of knowledge in this study and I will ask volunteers myself with a qualitative inquiry.

2.2 C

IVIL SOCIETYResearching the Refugees Welcome movement, it felt natural turning to the academic field of civil society for guidance and ended up in the body of knowledge on civil society and peacebuilding, which I find valuable in this polarized politicized issue of refugees. Unlike the field on volunteering, we find more qualitative research such as the two anthologies Civil Society and Peacebuilding: A critical assessment (Paffenholts, 2010) and People Building Peace II: Successful Stories of Civil Society (van Tongeren et al. 2005) that gives a deep and broad insight of civil society action in Guatemala, Israel and Palestine, Afghanistan, UN and civil society interactions, effective regional networks and partnerships, and theory about defining civil society. Trying to define what civil society is and what it does has gone on for centuries from John Locke to Charles de Montesquieu to Karl Marx to Antonio Gramsci. Theoretically I have overlooked normative frameworks and searched for the functions of civil society since I am exploring what the Refugees Welcome movement do, and not what it ought to do. The theoretical framework that will be used is Christoph Spurk’s seven functions of civil society which enables an in-depth analysis and the development of a detailed understanding of civil societies role in political, social and development processes (Spurk, 2010, p. 24). For accuracy, these seven functions are cited (ibid. p 24 –25) and are as follows:

1. Protection of citizens. This basic function of civil society is protecting lives, freedom, and

poverty against attacks and despotism by state and other authorities.

2. Monitoring for accountability. This function consists of monitoring the activities of central

powers, state apparatuses, and government. This is also a way to control central authorities and hold them to account. Monitoring can refer to human rights, public spending, corruption, and primary school enrolment.

3. Advocacy and public communication. An important task of civil society is its ability to

articulate interests – especially of marginalized groups – and to create channels of communication in order to bring them to the public agenda, thereby raising public awareness and facilitating debate.

4. Socialization. With its rich associational life, civil society contributes to the formation and

8 mutual trust, and the ability to compromise through democratic procedures. Thus, democracy is ensured not only by legal institutions but also by citizens’ habits.

5. Building community. Engagement and participation in voluntary associations also has the

potential to strengthen bonds among citizens, building social capital. In cases where associations include members from other ethnic and social groups, it also bridges societal cleavages and contributes to social cohesion.

6. Intermediation and facilitation between citizens and state. Civil society and its organizations fulfil

the role of balancing the power of, and negotiating with, the state at different levels (local, regional, national). It establishes diverse relations (communications, negotiation, control) among various interest groups or between independent institutions and the state.

7. Service delivery. The direct provision of services to citizens is an important activity of civil

society associations, such as self-help groups. Especially in cases where the state is weak, it becomes essential to provide shelter, health, and education. Although organizations executing civil society functions also provide services to members and clients, the functional model centres on political functions and objectives – in contrast to the third

sector debate that focuses on services and economic objectives. Thus, service delivery as a function is considered an entry point for other civil society functions, but this should be

based on a careful assessment of whether the specific service is indeed a good entry point for those objectives.

In this theoretical framework civil society consists of citizens helping citizens, and even though they may have different privileges and oppressions, they share a national identity, equality in civil rights (which includes the right to stay and live in the country) and a common government. Therefore, it is interesting to use in this study of citizens helping refugees who are from other countries, with other languages, other cultures, and religions. You could even say that it is ‘us’ helping ‘the other’.

2.3 S

OCIAL MOVEMENTSLooking at the Refugees Welcome Movement in 2015 civil society created networks all over Europe, and so I got curious to explore if it could be classified as a social movement. Della Porta and Diani bring together several strands of social movements in their Social Movements: An Introduction (2006) and their definition is widely used. I have made the decision to use their definition of social movements in this study directly adding it to this body of knowledge in a globalized milieu. According to della Porta and Diani:

... social movements are a distinct social process, consisting of the mechanisms through which actors engaged in collective action: are involved in conflictual relations with clearly

9 identified opponents; are linked by dense informal networks; shade a distinct collective identity

(2006, p. 20) [italics added].

Conflictual collective action mean that social movement actors are engaged in political and/or cultural conflicts to promote or oppose social change where there are oppositional relationships between actors who seek control of the same stake (like political, economic or cultural power), and in the process trying damaging the interest of the other actor (della Porta and Diani, 2006, p. 21). In their definition, addressing collective problems like producing public goods or expressing support for moral values and principles does not automatically make it a social movement action, it “requires the identification of targets for collective efforts, specifically articulated in social or political terms” (ibid.). Dense informal networks differentiate social movements processes from other instances of collective action usually coordinated within the boundaries of organizations:

A social movement process is in place to the extent that both individual and organized actors, while keeping their autonomy and independence, engage in sustained exchanges of resources in pursuit of common goals. No single organized actor, no matter how powerful, can claim to represent a movement as a whole (ibid.).

A social movement process is only in place when collective identities develop that goes beyond a sum of specific events or initiatives even though ‘the membership criteria’ may be extremely unstable and depending on mutual recognition between actors (della Porta and Diani, 2006, p. 21–23). The collective identity creates a connectedness:

It brings with it a sense of common purpose and shared commitment to a cause, which enables single activists and/or organizations to regard themselves as inextricably linked to other actors, not necessarily identical but surely compatible, in a broader collective mobilization (ibid. p. 21).

In addition to social movements they identify what they call ‘consensus movements’ which share the dynamic of actors sharing solidarity and interpretation of the world enabling them to link specific acts and events in a longer time perspective (della Porta and Diani, 2006, p. 22–23). What separates them is that a sustained collective action lacks a conflictual element and identified specific adversaries not trying to redistribute power nor making alterations social structures, instead focusing on service delivery, self-help, and community empowerment (ibid.). A social movement dynamic is going on when single events are perceived as parts in a longer-lasting action and those engaged feel linked to each other by ties of solidarity and communion with protagonists of other mobilizations (ibid. p. 23–24). The common identity should remain even when events have come to an end, this makes it easier to revival a mobilization in the future,

10 “movements often oscillates between brief phases of intense public activity and long ‘latent’ periods” (ibid). Della Porta and Diani differs other informal networks of collective actions like ‘coalitions’ where the collective actors are connected with each other in terms of alliances, the networks between the actors mobilizing for a common goal take a purely contingent and instrumental nature from a social movement since they lack the dynamic of a collective identity (ibid). A social movement is a fluid phenomenon and individual participation is a sense of being involves in a collective endeavour without automatically belong to a specific organization, “strictly speaking, social movements do not have members, but participants (ibid. p. 26). The new wave of global justice collective mobilization has shown that social movement politics still at a large extent is politics in the streets (ibid. p. 29).

2.4 R

EFUGEES AND CIVIL SOCIETY INE

UROPEThis study is aligned with the academic fields of volunteering, civil society and social movements, but going into that literature will not give you any further understanding of the puzzle where this study is but a little piece. Hence, here are some more pieces for further reading: Solidarity in Diversity: Activism as a Pathway of Migrant Emplacement in Malmö (Hansen, 2019), Refugee Protection and Civil Society in Europe (Feiscmidt et al. 2019), Conviviality at the Crossroads: The Poetics and Politics of Everyday Encounters (Hemer et al. 2020), The Refugee Reception Crisis in Europe: Polarized Opinions and Mobilizations (Rea et al. 2019), Solidarity Mobilizations in the ‘Refugee Crisis’: Contentious Moves (della Porta, 2018) and Migration, Civil Society and Global Governance (Schierup et al. 2019).

11

3 A

QUALITATIVE INQUIRY

When we choose our methodology, our epistemology and ontology decide for us the path where we believe we can find the answers to our questions, it also affects how we value and criticize different kinds of research. My own body of knowledge about qualitative research and methodology is a puzzle that has built up over the years reading, hearing and learning and it is hard to know exactly which author or teacher who gave me which piece of this puzzle. What I do know is that my curiosity, ‘epistemological and ontological conviction’ and my own research has been much influenced by reading John W. Creswell, and so my research design4 has been guided

by his works Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (2014) and Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (2013).

Qualitative research is appropriate to use when a problem or issue needs to be explored, like studying a population or a group, because there is a need to identify variables that cannot easily be measured, or to hear silenced voices (ibid. p.47-48). The volunteers in the Refugees Welcome movement in Sweden I believe cannot be classified as either a population nor a group – they engage in different time/space, very few know each other, they do not share a special culture, political affiliation, religion or education – hence, in order to find out who these people are and their similarities and differences there is a need for exploration. According to Creswell we should use qualitative research because we need a detailed and complex understanding of the issue and this details can only be found by talking directly with people and allowing them to tell their story unencumbered of what we have read in the literature or what we expect to find (ibid.). When it comes to understanding why people volunteer to help refugees, their experiences and thoughts; how the Refugees Welcome movement started and has evolved in Sweden 2015-2020; what civil society functions it has had and how it has developed makes a complex fabric best answered by asking the people involved that is the movement.

I could ask volunteers using a quantitative method like a survey which will give me a statistical result, but finding 1000 volunteers to answer it would take a long time in this scene where one interviewee gives you one name and that person gives you another, therefore the snowball-sampling method for data collection has been used. Clearly, volunteers are human beings and human beings are complex, and so is our social context, for example when asked the

4 My research design shares many traits with ethnography, grounded theory, and narrative design but with important

12 question ‘what is your motivation’ my interviewees take time to search in their childhood, reflect upon personality traits, values and experiences. In a survey I would have to give numerous predetermined and static options based on what I think is reasons for volunteering with refugees from the literature and this would give me limited and possibly misleading data. Creswell states that we should use qualitative research when quantitative research measures or statistical analysis simply do not fit the problem (ibid) and trying to make a quantitative study fit the purpose of this study does not work very well. Qualitative research should be used when we want to understand the settings or context in which the participants in a study address a problem or issue (ibid.) which fits with the complexity of both the volunteers and the rise, demise and rebirth of the Refugees Welcome movement in Sweden. This knowledge can only be gathered methodologically by interviews in confidence between the researcher and the participant. One characteristic of qualitative research is a holistic approach looking at the whole picture and not particular parts (Hammond & Wellington, 2013, p. 168) and researchers try to build a complex picture of the problem not bound by tight cause-and-effect relationship among factors but rather distinguishing complex interactions of factors in any situation (Creswell, 2013, p. 47).

Writing academically is a craft that we are trained to master, but I use the style that goes with a qualitative tradition of writing in a literary or flexible style without the restrictions of formal academic structures of writing (ibid.). Reviewing the rationales for conducting a qualitative inquiry I believe that my choice to do so is accurate since the answers to my questions cannot be found in the literature, found with quantitative methodology or secondary sources.

3.1 T

HE ART OF INTERVIEWINGWhen it comes to conducting in-depth interviews my perspective and method comes from peace research since I started to conduct interviews within Peace and Conflict Studies. Brounéus5

describes the benefits of the in-depth interviews like this:

... in-depth interviewing offers a unique method and source of information since it provides research with depth, detail and perspective on a certain research question, and at a certain moment in time. In contrast to secondary sources and survey research, the in-depth interview gives the researcher a first-hand account of the research of the question at hand [...]

5 In her chapter ‘In-dept Interviewing: The process, skill and ethics of interviews in peace research’ in Understanding

13 In addition, the interviews can give colour and warmth to cold facts and closeness to distant happenings (2011, p. 131).

My participants are interviewed in their role and commitment as volunteers under the ‘Refugees Welcome umbrella’, the only requirement for participating is to be over age and have agency:

Agency refers to the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their own decisions based on an awareness of their situation and the range of responses open to them; agency is sometimes referred to as voluntarism (Hammond & Wellington, 2013, p. 161).

This is important because I need to be sure that the interviewees understand the informed consent6, that everything is voluntary and that I can trust that they will be able to make informed

decisions of what to say and what not to say. This is also a way for me to take responsibility towards the research community, the interviewees and for myself. Choosing a “comfortable and encouraging atmosphere in which the interviewee feels respected and safe is important both for obtaining useful information and for conducting ethical research” (Brounéus 2011, p. 136), I have tried to do so by letting the interviewees decide time and place at their convenience, but also to lessen the power imbalance. Together we read and sign the informed consent and it is important to ask if they have any questions or if anything is unclear. Then they get to choose if they want to be audiotaped and if they want to keep their first name for the analysis or if they want an alias of their choice. An essential part of the ethics of interviewing is to anonymize our participants but I have let them decide and interestingly seventeen out of twenty decided to use their first name. To make the interview a pleasant experience and to get a rich and deep material I practice and cultivate the art of reflective listening:

Reflective listening involves using active non-verbal (nodding, ‘hmm’-ing) and verbal (‘tell me more...’) listening techniques, but the core skills of reflective listening are the following: reflecting fact, reflecting emotion, questioning on fact, and questioning on emotion [...] These core skills of reflective listening involve exploring and understanding the speaker’s perspective [...] If researchers are skilful listeners they will receive more and better quality information from the interviewee, understand that information better and, as a result, have an improved basis for analyzing the research question at hand (Brounéus 2011, p. 137).

I use a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions. Before we start the interview, I tell my participants that this will not be a conversation since I will be silent (with nodding and ‘mm’-ing) so that the interviewees have space for their answer. But also, in order for me not to affect their associations and choice of words (it is so easy to contaminate). Telling them this has been positive for them and make them relaxed, probably because it gives the interview ‘rules’ that

14 they do not have to quick answers and do not need to be afraid of silence. Unfortunately, the interviews about Refugees Welcome to Malmö are not as rich with emotions and self-reflections as the post-2015 interviews since I have developed my skills over the years.

3.2 A

THEMATIC ANALYSISPeople who are unfamiliar with qualitative research may see it as scientifically unpredictable or unreliable, and there is an ongoing debate within qualitative research if thematic analysis is a method of its own and if so, how is it done. Braun and Clarke discuss these views and outline the theory, application, and evaluation of thematic analysis in Using thematic analysis in psychology (2006). They argue that it should be seen a foundational method within qualitative research and that thematic analysis is the first method of analysis that all qualitative researcher should learn since it provides core skills useful for conducting other forms of qualitative analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 78). A “thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes your data set in (rich) detail” (ibid. p. 79) and “through its theoretical freedom, thematic analysis provides a flexible and useful research tool, which can potentially provide a rich and detailed, yet complex, account of data” (ibid. p. 78). In order to look at the development of the Refugees Welcome movement before and after the checkpoints I will analyze the post-2015 material the same way as I did with Refugees Welcome to Malmö. I followed Braun and Clarkes guide to conduct a thematic analysis, every step has a detailed description and ends with a 15-point checklist of criteria for a good thematic analysis and how to avoid potential pitfalls. Before moving to these steps, for you to understand my decisions and how I have conducted my thematic analysis, I will outline some of the words that is used and how they are defined in this guide:

A theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research questions,

they represent some level of patterned meaning within the data set; data corpus refers to all

data collected for a research project; data set refers to all the data from the corpus that are

being used for analysis; data item is used to refer to each individual piece of data collected,

which together make up the data set or corpus; data extract refers to an individual coded

chunk of data, which has been identified within, and extracted from, a data item. There will be many of these, taken from throughout the entire data set, and only a selection of these extracts will feature in the final analysis; codes identify a feature of the data (semantic content

or latent) that appears interesting to the analyst, and refers to ‘the most basic segment or element, of the raw data (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 79, 82, 88).

15 In the thematic analysis I have followed these steps: 1) Familiarizing yourself with your data, transcribing and re-reding the data 2) Generating initial codes, coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set 3) Searching for themes, collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each theme 4) Reviewing themes, checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts and the entire data set 5) Define and naming themes, refine the specifics of each theme 6) Producing the report, final analysis of selected extracts relating to research questions, literature and the production of a scholarly report of the analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 87). Compared with other methods for analysis the thematic analysis was relatively quick and easy to learn (with these guidelines) which is beneficial in order to make it correctly and properly from the beginning to the end.

In my bachelor’s thesis ‘I had to do something’ Refugees Welcome to Malmö and the stories of the volunteers regarding the refugee crisis during the fall of 20157 (Mäkelä, 2016) I used my

empirical material of 13 interviews with 10 interviewees that together amount to 16 hours of raw data. When it comes to the post-2015 Refugees Welcome-initiatives8 I have conducted 12 interviews

with 10 volunteers during the years 2018, 2019 and 2020 which sum up to 19 hours of raw material. Thus, my data corpus entails 20 interviewees, individual interviews sums up to 25 occasions and 35 hours of raw interview material. I have decided to have of four categories of data sets 1) the individual interviewees, 2) the individual interviews, 3) the fall of 2015 and 4) post-2015. I have collected data items from all the data sets (my whole data corpus) and I have used codes developed from my research questions for my selection of extracts (quotes) that is presented as themes in the analysis. I believe it is important to highlight that my data corpus entails 20 interviewees, individual interviews sums up to 25 occasions and 35 hours of raw interview material hence, the old interviews and themes from Refugees Welcome to Malmö is re-analysed together with the new data and new theoretical frameworks.

I am doing a mix of ‘theoretical’ thematic analysis and an ‘inductive’ thematic analysis, which may be important to note. The differences are that in an inductive thematic analysis the specific research questions evolves during the coding process without paying attention to themes identified in previous research, while a ‘theoretical’ thematic analysis is more driven by the

7Selected parts from my published bachelor’s thesis ”I had to do something” Refugees Welcome to Malmö and the

stories of the volunteers regarding the refugee crisis during the fall of 2015’ (Mäkelä, 2016) is published in the chapter “‘Only Volunteers’? Personal Motivations and Political Ambiguities within Refugees Welcome to Malmö civil Initiative” in Refugee Reception and Civil Society in Europe (2019) co-authored with Professor Maja Povrzanović

Frykman.

8Selected parts from four of my interviews conducted in 2018 and 2019 have become the chapter named ‘Post-2015

Refugees Welcome Initiatives in Sweden: Cosmopolitan Underpinnings’ in Conviviality at the Crossroads: the poetics and politics of everyday encounters (2020), co-authored with Professor Maja Povrzanović Frykman.

16 researcher’s theoretical interest on the issue, coding for a specific research question and as such is more explicitly analyst-driven (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 83-84). My codes are generated from my research questions, it is analyst-driven but without paying attention to themes identified in previous research. I do not want my data to be ‘fitted into’ existing theory or use a specific pair of ‘theoretical glasses’ to tell me what to look for – my codes are exploratory in order to let my interviewees tell us how things are and what is important to know.

17

3.3

D

ATA COLLECTIONI would like to start by pointing out that this study would not have been possible without the interviewees generosity sharing their experiences, reflections, and feelings. The data collection for Refugees Welcome to Malmö started with a message to Petruska, the administrator of their Facebook group, asking if she could publish my ‘advertisement for interviewees’. Since she was a member of ‘the leadership’ she became an important gatekeeper, on her own initiative she created a chatgroup ‘throwing in people’ as to help me find participants, and for people to spread the word if someone else would be interested. Hence, my gatekeeper turned out to be a good facilitator for the snowball-sampling. A nice surprise was that several people reached out to me due to the advertisement because they found my research important and they wanted to tell their story.

For the post-2015 interviews I sent one request to Refugees Welcome Sweden’s official email address, and I did the same to Refugees Welcome Housing Sweden’s official email address both found on their webpages. The chairpersons of both initiatives accepted and from there on it was snowball-sampling. As with the interviewees about 2015, it has been a lovely surprise that so many people wanted to participate and share their experiences, thoughts and feelings. All interviewees have answered questions about age, higher education, foreign background, employment, previous experience of volunteering and which political party they voted for in the 2014 parliamentary election for the 2015 interviewees, and the 2018 parliamentary election for the post-2015 interviewees. Everyone had the option to answer ‘private’ on every question, and the ones who chose an alias thought it more important to answer the questions openly to contribute to the research than keeping their name. When asking the interviewees who chose to keep their name about the reason for doing so, one half does not really care, and the other half emphasize that keeping their name is important to them since they see it as a political statement, or as a humanitarian declaration. Regardless of the name, the fact that their thoughts and experiences will be documented have been something positive for my interviewees, since they are very passionate about their work, and it gives them an opportunity to be honest about our society freely knowing that people will read it. I have been very cautious to conduct my interviews in the same way over the years and use the same material (informed consent, table-questions, and interview guide) so that I can see changes and make comparisons over time. The only thing that I have changed is that I removed the questions ‘how would you define a volunteer’ and ‘how would you define civil society’ since my 2015 volunteers had a hard time answering them.

The only secondary material for the analysis is transcriptions of a speech made by the Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven on the 6th of September 2015 and a press conference on

18 the 24th of November when the Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven and Vice Prime Minister

Åsa Romson, selected for important context.

3.3.1 A

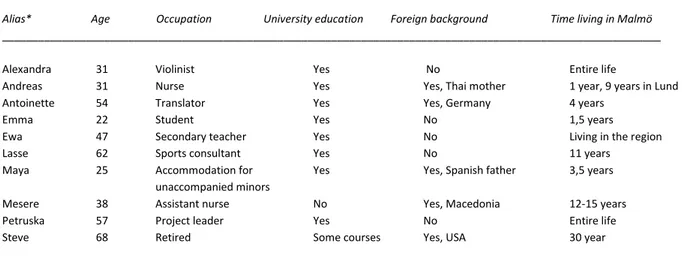

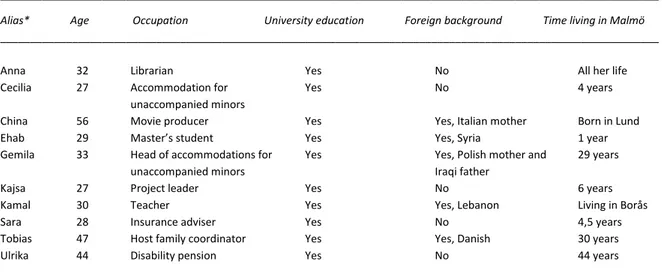

PRESENTATION OF THE INTERVIEWEESI have collected data on age, occupation, higher education, ethnic background, time living in Malmö/Sweden, previous experience of voluntary work, membership in any organization and their vote for parliament in 2014 for the Refugees Welcome to Malmö volunteers and in 2018 for the post-2015 refugees welcome volunteers. I have not used this information in the analysis, but it may be of value while engaging with the analysis, comparing similarities and differences with other studies or among the volunteers within this study.

19

3.3.1.1 Table of participants Refugees Welcome to Malmö 2015

Table 1.2 Interviewees by former experience of volunteering, membership in or financially support of organisations, political orientation (how they voted in Swedish parliamentary elections in 2014).

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alias* Previous experience of voluntary work Membership in organizations Vote for parliament 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Alexandra Andreas Antoinette Emma Ewa Lasse Maya Mesere Petruska Steve In gaming associations

Within the church and the Red Cross None

On Lesbos in 2015, student associations None

Several decades in sports organizations None

In Sisters for Sisters

Parents’ cooperatives, different boards Mostly activism

Gaming associations, Refugees Welcome to Malmö Doctors Without Borders, Red Cross

None

Red Cross, Refugees Welcome to Malmö Red Cross, Amnesty, Doctors Without Borders Nature Conservation, Red Cross

Doctors Without Borders

Sisters for Sisters, Refugees Welcome to Malmö Greenpeace, Save the Children, project organizations The Left Party, HBTQ rights associations, Amnesty

The Green Party Social Democratic Party No right to vote The Moderate Party The Feminist Initiative The Green Party The Left Party Blank

The Liberal Party The Left Party

* The names used in this study were chosen by the participants; some are their real names.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Source: Mäkelä (2016) ’I had to do something’ Refugees Welcome to Malmö and the stories of the volunteers regarding the refugee crisis

during the fall of 2015.

Table 1.1 Interviewees by age, profession, higher education, foreign background and time of living in Malmö.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alias* Age Occupation University education Foreign background Time living in Malmö

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Alexandra Andreas Antoinette Emma Ewa Lasse Maya Mesere Petruska Steve 31 31 54 22 47 62 25 38 57 68 Violinist Nurse Translator Student Secondary teacher Sports consultant Accommodation for unaccompanied minors Assistant nurse Project leader Retired Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Some courses No

Yes, Thai mother Yes, Germany No

No No

Yes, Spanish father Yes, Macedonia No

Yes, USA

Entire life

1 year, 9 years in Lund 4 years

1,5 years Living in the region 11 years

3,5 years 12-15 years Entire life 30 year

* The names used in this study were chosen by the participants; some are their real names.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Source: Mäkelä (2016) ’I had to do something’ Refugees Welcome to Malmö and the stories of the volunteers regarding the refugee

20

3.3.1.2 Table of participants post-2015 Refugees Welcome initiatives

Table 2.1 Interviewees by age, profession, higher education, foreign background and time of living in Malmö.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alias* Age Occupation University education Foreign background Time living in Malmö

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Anna Cecilia China Ehab Gemila Kajsa Kamal Sara Tobias Ulrika 32 27 56 29 33 27 30 28 47 44 Librarian Accommodation for unaccompanied minors Movie producer Master’s student

Head of accommodations for unaccompanied minors Project leader Teacher Insurance adviser Host family coordinator Disability pension Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No

Yes, Italian mother Yes, Syria

Yes, Polish mother and Iraqi father No Yes, Lebanon No Yes, Danish No

All her life 4 years Born in Lund 1 year 29 years 6 years Living in Borås 4,5 years 30 years 44 years

* The names used in this study were chosen by the participants; some are their real names.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Source: Mäkelä (2017-2020)

Table 2.2 Interviewees by former experience of volunteering, membership in or financially support of organisations, political orientation (how they voted in Swedish parliamentary elections in 2018).

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alias* Previous experience of voluntary work Membership in organizations Vote for parliament 2018

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Anna Cecilia China Ehab Gemila Kajsa Kamal Sara Tobias Ulrika Very little

National chairperson for Tamam Much experience, mostly within culture The Salvation Army, the Swedish church The Red Cross (women’s shelter) FARR, No one is illegal, The asylum group In Glöm aldrig William Petzäll foundation Scouts, Bergatrollen, Counter Point, homework support, ‘schysst’ initiative Yes, different engagements

Counterpoint

The Swedish Outdoor Association, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and the Red Cross

Tamam and RWHS*

Amnesty, Green Peace, United Rescue Aid among others No

RWS*, Doctors Without Borders

The Swedish Peace- and Arbitration Society, Amnesty RWS*, FARR*

Amnesty, World Animal Protection, RWHS*, RWS* FARR*, RWS*

Greenpeace, several culture associations

The Social Democrats Private

Private Not eligible yet The Left party The Left Party The Green Party The Left party The Left Party Private * The names used in this study were chosen by the participants; some are their real names.

*Refugees Welcome Housing Sweden *Refugees Welcome Sverige (Sweden) *Flyktinggruppernas Riksråd

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

21

4 A

NALYSIS

This analysis consists of two parts, part one is about the Refugees Welcome to Malmö civil society initiative during the refugee crisis in 2015, and part two is the post-2015 Refugees Welcome civil society initiatives9. The ‘Preface: what we have sworn to defend’ and middle section

‘Checkpoints: for the international right to asylum’ are added in order to get a better understanding of the shifting context changing opportunities and challenges in the reception and protection of refugees.

4.1 P

REFACE:

WHAT WE HAVE SWORN TO DEFENDOn the 6th of September 2015, the Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven stands on a small stage

at with a “Refugees Welcome” banner behind him. In the pouring rain, he starts to speak to the audience:

Millions of people are on the run, from war and horrifying terror. These are people like you and me, with their wishes and their dreams about life. But they are being forced to flee from bombings

with their children in their arms. And on their way, they risk their lives in cargo spaces, containers, and in completely unseaworthy boats, and not everybody makes it [...] My Europe receive people that are fleeing from war [applause] and we do it in solidarity, we do it together, my Europe do not build walls! [...] So now it is time for Europe to stand up for humans’ inviolable value and equal rights, what we in declarations and agreements have sworn to defend, this is what

we have stood up for and this is what we stand up for here today. [...] But the most important of all, still, is to be a buddy, a friend, to welcome people when they come [...] And we will, dear friends, continue to be a country that carry solidarity as our main pride (Stefan Löfven,

“Refugees Welcome Manifestation”, 2015).

The European states including Sweden are democracies, hence the power over mortality is supposed to reside with the citizens. So, when it comes to the question of who may live and who may die in a refugee crisis there are people who have a definite answer, and the answer is refugees welcome!

9Unless there is a specific reference the information and descriptions come from the stories of the interviewees,

22

4.2 P

ART1:

R

EFUGEESW

ELCOME TOM

ALMÖ IN THE FALL OF2015

In this part the results from the thematic analysis based on interviews with ten volunteers active in the civil society initiative Refugees Welcome to Malmö is presented, and every theme is introduced with a description of how and why the theme got its name. The seven functions of civil society will be used to explore Refugees Welcome to Malmö as a civil society actor, and the motivations, experiences and choice to become a volunteer within this initiative will be connected to previous research in accordance to its relevance.

4.2.1

A

N OPPORTUNITY TO DO GOODWhen asking the interviewees why they came to be volunteers the theme ‘an opportunity to do good’ was developed. ‘Good’ used in the theme and by the interviewees is the best translation for the Swedish word nytta. ‘Att göra nytta’ [to do good] is connected to labour, to not be lazy and waste your time, it is not about being a good person. The stories of the interviewees tell us that when they saw an opportunity to help it was a spontaneous act rather than a planned one. In the refugee reception some volunteers felt that they did something good by being there to welcome, while others saw that their qualities and knowledge could do good.

On the evening of the 7th of September Mesere walks down to Malmö Central Station with some

sandwiches, she had read of Facebook that some refugees were on their way, she says that:

If I have the possibility to help someone I do it, from the smallest to the largest. I do it automatically, it is nothing that I am thinking about, if I can I will do it. It was not like I was thinking and wondering ‘what should we do’, it was just to go there.

Steve calls himself a ‘internet-twitter-warrior’, he is the activist who on social media is fighting for equality between women and men, LGBT rights and against the occupation of Gaza. So, for him it was a natural step to become a volunteer:

Yes, I went down there because someone told me to go down to the Central Station since they needed help, and when I got there they said that I should go down to Bike and Ride10

and you know, it took a week [laughing] before I came home [...] it felt really good that you could do something in real life, in real time, instead of just sitting on the internet.

10Bike and Ride is a garage for bicycles near the Central Station that was lent out to Refugees Welcome to Malmö. This is

23 Ewa is also active on social media and felt, just like Steve, that it felt good to leave the couch and do something more and join the work that she saw others doing. It all started when she read an article about Refugees Welcome to Malmö, and she had heard her students talk about some list. By searching on ‘Refugees Welcome’ on Facebook she found the list where you sign on different tasks that are needed and got in contact with Petruska. Petruska followed Ewa to Djäknegatan where Ewa started to volunteer with unpacking, sorting, and packing donated clothes.

It all started for Lasse when he felt that he wanted to do something and went through his closet, drove down to Djäknegatan to donate the clothes and got the question if he would like to become a volunteer. He says that he was thinking “well, why not, you could always try” and so he wrote up his name:

... here offers [you] a possibility to like, directly like ‘sign up’, come down and help [clicks] and tomorrow I’m there [...] I don’t go to a meeting and say what I think that someone else should do or what we should do or something. I go down there and after three hours work, I have helped people who need me.

Donation of clothing was Petruska’s way in to become a volunteer as well. One day she saw on Facebook that there was a need for clothes “so I made a fast sweep in mine and my husband’s closet and went down to the Central Station”. When she came back the day after with more clothes that she had collected from family and neighbours Petruska noticed that the clothes from yesterday were kept outside and it was bad weather, “it was incredibly messy and chaotic, and I saw that among the clothes it was a lot was garbage as well which people just took the chance to get rid of”. Petruska says that she has been a member of international organizations and contributing with monthly donations for many years, but lately she had felt to do something more active and more local, particularly when it comes to refugees:

So when, when this came up, when I suddenly saw a situation in front of me where it really was a need for the expertise that I have, as a professional project leader, I felt that, it was like coming to a table where I could do as much good as possible.

She started to look for the people who were in charge of the refugee reception at the Malmö Central Station, and after a few days she found the small room in the basement of Bike and Ride where Mesere and Alexandra and some others were in the act of founding the non-profit association Refugees Welcome to Malmö (in order to become a legal entity with the ability to open up a bank account) and Petruska offered them her help and together they became ‘the leadership’

24 later the board11 who organized the initiative at the best of their abilities. Except from making use

of her experience and expertise she saw that she could use her contacts within Malmö Stad, the Region and private business. To make use of experience and expertise was the way in for Alexandra as well, when she arrived at the Central Station, she got the word that there were no more people needed. So, she wrote to the Facebook-group and asked if they needed any help “since it was chaos”:

Basically, there was a situation that needed to be solved, the fact that all these people [the refugees] came to Malmö Central Station, there was a lot of people that was trying to do something about it [to help] and I saw an opportunity where I could help them to do it better. They didn’t need more hands down there, but I could help them do it more affectively [...] that I, with pretty easy measures could make a difference.

When flyktingfrågan12 came up in the media Antoinette though it was important to help, and she

describes it as her own initiative since she was looking for organizations who helped at Malmö Central Station on the internet, but when she did not find any she went down there to look at site. There she found Refugees Welcome to Malmö and she signed up on their schedule. According to Antoinette it was rewarding to be a volunteer, she felt that she was doing something good and she was appreciated. The refugees that she met were very grateful, and Antoinette says that this was reward enough for her being there helping out. Another person who saw what was going on in the media was Maya, and she felt that she had to do something. She was following Refugees Welcome to Malmö and Kontrapunkt13 on Facebook:

And then, they [Kontrapunkt] had a list where it said if you want to be a volunteer, this is

where you sign up. And I mean I saw what was happening, [...] so I checked some boxes and some I didn’t even understand what it meant but I clicked anyway [laughs].

For Maya, volunteering became an opportunity to help because:

...I didn’t have a lot of money, so I thought that I cannot give a lot of money, and I haven’t got a lot of things to give, I have nothing for children to give, I have like nothing good to give away, so what do I have then, I have like my time to give.

11 The ‘leadership’ was the initial name before they became a formal bord. Since the quotes are from both periods of

time in the analysis, I will use only ‘the leadership’ to prevent confusion. It is also the name most used by the interviewees.

12Realpolitik with the direct translation ‘the question about the refugees’ with political and humanitarian polarization. 13 Kontrapunkt [Counterpoint] is a cultural and social center run by the Kontrakultur [Counterculture] association

with the vision to create a more solidary society. They did a huge effort during the refugee crisis providing accommodation and serving a thousand meals a day. For more information on Kontrapunkt see Hansen (2019).

25 Andreas wanted to do something, but he did not know how or where. But one day he saw an advertisement on the library where he lives, that there would be a meeting for volunteers, and on that meeting he understood how easy it was to become a volunteer:

... just because of this meeting then, there I understood that yeah, it’s that simple [...] and I wanted to do something, I wanted to do something [...] you didn’t need, need to get an

advanced education [...] you just show up, a very welcoming group there and then and I just like, fell into it. And then I was hooked.

Emma’s way to Refugees Welcome to Malmö starts with a whole other story, after reading an article she and her best friend got inspired. So, they raised money on Facebook and went to Lesbos to help on their own “so it was really spontaneous but also very fun”. But in Lesbos they were met with chaos, misery and pain and it became a battle against time to save lives and limbs. The line-up for registration could me miles long and during her time there it was raining heavily and so their money first and foremost went to tents, umbrellas, and socks. She shares a memory about an old man who had a lot of pain in his foots, and when she took off his shoes, she saw that they had started to rot, standing in water for days. She also recalls seeing woman she had helped to the medical tent leaving it dead. Coming home she describes it as a depression, nothing in her normal life had any meaning, if she was not laying in the darkness without sleeping, she was following what was happening on Lesbos. If she could, she would have gone back but there was no money to cover it. Emma had to do something and on a meeting for volunteers she met two people from Refugees Welcome to Malmö and Emma joined them.

According to Ewa Refugees Welcome to Malmö became a facilitator, that without this initiative there would have been individuals and small groups running around doing their own thing. Why some 800 people decided to volunteer within this initiative is hard to know and further research on this is needed, but according to the interviewees some reasons were that it was new without any history, identity, ideology or religious ground, therefore you did not get an ‘etiquette’ or ‘choose any sides’ except the notion ‘refugees welcome’. However, another reason is voiced by several interviewees, namely that it was so fast and easy.

Previous research show that to be asked personally is the most important factor when it comes to becoming involved in voluntary work and that this step is spontaneous in a social context (Rochester et al., 2012, p. 131-132). However, Behina suggest that volunteers are choosing between organizations and projects that correspond to their personal goals, values, and ideology and when they feel ready, they contribute with their resources (2012, p. 8). These two theories suggest that the act of becoming a volunteer is either an external social context that sweeps you in, or an internal want looking for the right social context. Among the interviewees it

26 seems like the act of becoming a volunteer is a combination of these two: an internal motivation and will to help, and a personal invitation in a social context together with the simplicity to take the step without any special knowledge, training or waiting list. One significant factor that I find important to note is the role of social media, enabling Refugees Welcome to Malmö to be ‘founded’ in a heartbeat and to communicate and organize what was needed, where and when with a post.

4.2.2

B

UILDING BRIDGES BY COOPERATIONThe theme ‘building bridges by cooperation’ highlights the cooperation between different civil society actors despite different religious beliefs and political ideas, how they got together in order to manage the situation. Additionally, the theme is grounded in the stories of how new social networks were developed as a result of this voluntary action.

Steve was active from the beginning and he put a lot of time and personal engagement into the refugee reception. On one occasion Steve and Mesere (the initiator of Refugees Welcome to Malmö) were interviewed together, and along with Lasse and Petruska they paint a picture of the cooperation on Malmö Central Station during the crisis:

Steve: It was a good mix of people, and especially during one week, there were some from the Jewish Assembly who were there with kippa, and I thought, what a wonderful thing: there are Christians and Muslims and Jews who welcome these people who are arriving, you know. [...] One could see how people set aside their political ideologies, now that people are dying, and we have to help them, you know. The atmosphere was actually wonderful.

Mesere continues where Steve left of: Yes, absolutely, Malmö woke up to life and everyone wanted to help [...] What was so wonderful, was that our faith became humanity, a common faith you know [paus] There was no, like you didn’t see any, like Muslims, Judaism, Christianity, they didn’t exist. It did not exist any religious beliefs, it didn’t exist any politics. Of course, everyone had their opinions, but we had one common opinion and it was humanity.

Petruska lights up when asked about her experiences:

I have got to know these amazing people, both among the volunteers and the newly arrived. And I have got new good contacts within Malmö Stad and, the Red Cross, Save the Children, the Salvation Army, in other words organizations which I didn’t believe that I would be associated with, or get to know people. Hence, my social network has grown in an amazing way.

27 Many were very young, very angry, very leftist, very anti-everything. So, sometimes I felt quite alone being the one who is used to have employer responsibility, being used to have regulatory contacts and such so, there I was a little lonely at times.

When Emma and her friend went to Lesbos, they went by themselves. But well in place they got in contact with other volunteers who were there on their own initiative or with a new founded initiative. Cooperating and supporting each other they all acquired well needed contacts and new friends from many places:

We cooperated with volunteers from Scotland, London, Holland, one from Switzerland, Puerto Rico, it was really from all over the world. It was a lot of Greeks and a whole Danish team, and we also met two other Swedes. From all over the world actually, it was pretty cool. When it comes to the experience of volunteering within Refugees Welcome to Malmö, Emma says that it felt familiarly and warm. Refugees Welcome to Malmö cooperated with other Refugees Welcome initiatives like Flensburg in Germany and Trelleborg in order to know how many refugees that were on their way, and Gothenburg and Stockholm to tell them how many were on their way from Malmö. Lasse was a volunteer both before the authorities took over and after:

It, it is a lasting experience actually, which, which I have highlighted in many social contexts. It was an amazing unity, no matter if you were [a volunteer in] Refugees, Police, Security

Guard, if you were Malmö Stad [the municipality] the Migration Agency, if you were the Red Cross, or anyone else who were there. You, like you tried to solve the situation together the best way possible [...] there is a tremendous capacity, among people, to without ‘manuals’ actually solve situations if you really have to.

When it comes to Refugees Welcome to Malmö’s work during that time Alexandra believes that this reduced opposition, “like, against the people who come, when people get an opportunity to help them [...] and see them as people and not as a problem”. When Andreas looks back at the encounters with refugees at Malmö Central Station, he says that:

On the personal level it was amazing to meet all these kinds [unaccompanied minors] [...] it was really fun trying to talk, these language barriers, we didn’t have a lot of words in common but we could like, well, with the international body language we tried to reach each other.

Andreas experience is not unique, several of the interviewees lights up when they are talking about the short encounters with refugees, but more about this in the theme ‘a positive experience’. In this theme we can identify the fourth function of civil society, namely socialization where people practice democratic attitudes and develop mutual trust, tolerance, and a rich

28 associational life (Spurk, 2010, p. 24-25). But also, the fifth function of building community which has the potential to build social capital and strengthen the bonds between citizens (ibid.). I would like to argue that all these encounters that took place between people of different religion, age, gender, sexuality, ethnicity/race, class, and country of origin created new social networks, friendships, and familiarity. But also a practice of mutual trust and tolerance along with democratic attitudes when religious congregations, civil society organizations and initiatives like Refugees Welcome to Malmö came together to handle the situation due to their common engagement to receive and protect refugees in the fall of 2015 in Malmö. When the authorities took over no activity was allowed within Malmö Central Station. The only civil actors that were permitted to officially continue doing their work was the Red Cross and Refugees Welcome to Malmö within the area set up at Posthusplatsen. Because of this the networks of cooperation bridging religion and politics were no longer needed and so dissolved. A collective identity is needed for a social movement (della Porta & Diani, 2006, p. 21–23) and based on the stories of the interviewees a process of developing a collective identity may have begun before the authorities banned all civil society actors and individuals to take care of refugees. Instead the cooperation is more like what della Porta and Diani calls a coalition where collective actors are connected in terms of alliances and mobilizing for a common goal has a purely contingent and instrumental nature (ibid, 23–24).

4.2.3

P

RESTIGE,

CRITIQUE AND CONFLICT ON ALL FRONTSThe theme ‘prestige, critique and conflict on all fronts’ visualizes the conflicts that were going on between volunteers and the leadership, different civil society actors and between these and state actors. Moreover, there was competition and prestige between the different actors in the refugee reception.

Mesere describes that in the beginning of September the refugee reception mostly consisted of autonomous groups without any organization or shared responsibilities, and sometimes conflicts arose, like the best way to receive the refugee. When Refugees Welcome to Malmö established the routine not to receive refugees on the platform (beneath ground) but to wait for them to come up since many refugees became scared and ran away when someone in a yellow vest clutched them as soon as they jumped off the train. Even though they communicated this Mesere says that many autonomous groups went down to the platform anyway, like they “were competing to be the first ones to receive the refugees” instead of waiting up at the Central Station. When I ask